Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

ROBERT B. FAIRBANKS

Housing the City: The Better Housing

League and Cincinnati, 1916-1939

A varity of historians have dealt with

the housing movement

in America prior to the Great

Depression, examining how the

reformers viewed the housing needs

around them. Robert H.

Bremner in From the Depths explained

how the environmental

emphasis of Progressive housing reform

reflected the changing

view of poverty from the mid-nineteenth

century notion which

had blamed individual moral breakdown.

Roy Lubove emphasized

the leadership and influence of Lawrence

Veiller, stressing his

narrow definition of the issue as one of

poor sanitary conditions

needing sanitary and structural

regulatory improvement. And in

his study of housing reform in Chicago,

Thomas L. Philpott em-

phasized how the reformers' concern with

order and stability

colored their perception of the

problem.1

Despite these various approaches to

housing reform, little

effort has been made to analyze the

housing reformers by examin-

ing their changing conception of the

city.2 Such an inquiry might

Robert B. Fairbanks is a Ph.D. candidate

in history at the University

of Cincinnati. The author wishes to

acknowledge and thank Professor Zane

L. Miller, University of Cincinnati, for

helping the author clarify the

argument of this essay.

1. Robert H. Bremmer, From the

Depths: The Discovery of Poverty in

the United States (New York, 1956); Roy Lubove, The Progressives and

the Slums: Tenement House Reform in

New York City: 1890-1917 (Pitts-

burgh, 1963); Thomas L. Philpott, The

Slum and the Ghetto: Neighborhood

Deterioration and Middle-Class Reform in Chicago,

1890-1930 (New York,

1978). Also see Lawrence M. Friedman, Government

and Slum Housing:

A Century of Frustration (Chicago, 1968); Mark I. Gelfand, A Nation of

Cities: The Federal Government and

Urban America, 1933-1965 (New

York, 1975); Anthony Jackson, A Place

Called Home: A History of Low

Cost Housing in Manhattan (Cambridge, 1976).

2. Examples of how the public's changing

conception of the city in-

fluence the way they perceive specific

urban problems can be found in

158 OHIO HISTORY

better explain why the report of the New

York State Tenement

House Commission in 1900 defined the

housing problem as one of

unhealthy and congested tenements which

threatened "the future

social and sanitary welfare of the

city," while by the thirties the

problem would be seen as one of an

irreparable slum environment

and area blight. The former problem

could be corrected, according

to reformers, by municipal regulations,

while the latter problem

could be remedied only by federally

subsidized slum clearance and

public housing projects. Local housing

organizations which had

earlier denied the need for such action

now lobbied for federal

monies, since "the only intelligent

solution to the housing problem

is demolition and rebuilding."3

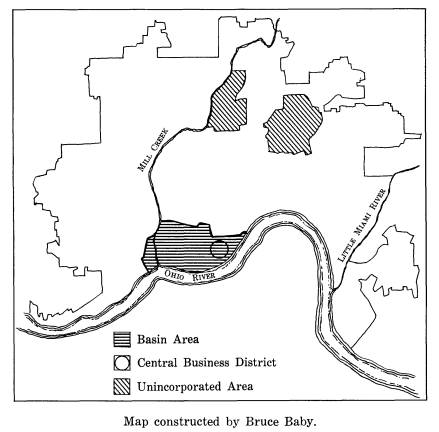

The Cincinnati Better Housing League

(BHL) provides a use-

ful vehicle to probe the housing

reformers' shift from regulation of

sanitary conditions to slum clearance.

The League, established in

1916, not only led the better housing

movement in Cincinnati, but

also earned national recognition as one

of the country's most effec-

tive local housing associations. During

this time, the BHL leader-

ships' perception of what needed their

attention altered and that

shift stemmed from a change in their

definition of the nature of

urban growth and expansion.

The creation of the Cincinnati Better

Housing League on 10

July 1916 marked not the culmination of

interest in housing reform

in the city, but the continuation and

intensification of an older

concern with tenement houses which

groups such as the Anti-

Tuberculosis League, the Chamber of

Commerce, the United

Jewish Charities, and the Associated

Charities had generated. In-

deed, as early as 1903 the nature of the

city's tenement problem,

as seen by these groups, had received

full explication.4 In a paper

Geoffrey Giglerano and Zane L. Miller,

"The Rediscovery of the City:

Downtown Residential Housing in

Cincinnati, 1948-1978" (unpublished

paper prepared for the Community

Development Panel of the Cincinnatus

Association, Cincinnati, 1978) and Zane

L. Miller, Neighborhood and

Community in a Suburban Setting:

Forest Park, Ohio, 1935-1976 (Knox-

ville, Tennessee, forthcoming).

3. Robert W. DeForest and Lawrence

Veiller, eds., The Tenement

House Problem Including the Report of

the New York State Tenement

House Commission of 1900, vol. I (New York, 1903), xiv; Trend Today in

Housing: Annual Report of the BHL (Cincinnati, 1933); Bleecker Mar-

quette, Twentieth Annual Report of

the BHL (Cincinnati, 1936), 4.

4. The Cincinnati Building Code defined

tenement as "a house or

Housing the City 159

given that year at the national

Conference of Charities and Correc-

tion, C. M. Hubbard, secretary of the

Associated Charities of

Cincinnati, observed that a local

tenement house survey had dis--

closed appalling sanitary conditions

among Cincinnati's tenements

in the crowded downtown Basin area.

According to Hubbard, the

conditions in that area threatened the

social well-being of the

community and could be remedied only by

adopting an effective

municipal regulatory code and

establishing systematic inspections

by city officials. Nine years later,

moreover, the Cincinnati Anti-

Tuberculosis League initiated a

"Darkest Cincinnati" campaign

which also emphasized the deplorable

sanitary conditions and con-

gestion within the city's tenements.

And in December of that same

year, 3,000 citizens attended a meeting

chaired by Mayor Henry T.

Hunt to decide how best to clean up the

tenements.5

Focusing on the creation and

enforcement of local tenement

housing codes, Cincinnati's early

twentieth century housing re-

formers stressed that these tools would

help solve the tenement

problem and argued over the most

effective means of carrying out

the code and inspection program. After

the city's first tenement

code of 1909 failed to bring about the

results anticipated by the

reformers, they blamed the Building

Department for inappropri-

ately administering the law and

campaigned for a separate Tene-

ment House Department to oversee the

code's enforcement. As a

result of the controversy over who

should administer the tenement

code in Cincinnati, between 1909 and

1916 the enforcement mech-

anism was constantly being challenged,

restructured, and challeng-

ed again by those confident that

securing enough honest and

efficient housing inspectors would

solve the problem.6

Concern in Cincinnati with housing

standards coincided with

and took the same form as the growing

nationwide interest in the

building or portion thereof which is

rented, leased, let or hired out to be

occupied, or is occupied as the home or

residence of three or more families

living independently of each other and

doing their cooking upon the

premises, but having a common right in

the halls, stairways, yards, water-

closets or some of them." Codification of

Ordinances of the City of Cin-

cinnati, 1911, 140.

5. C. M. Hubbard, "The Tenement

House Problem in Cincinnati," Pro-

ceedings of the National Conference

of Charities and Correction (Atlanta,

1903), 352; Herbert Frank Koch,

"Report on the Housing Problem and

Housing Reform," (typewritten,

Cincinnati, 1915), Cincinnati Historical

Society (CHS).

6. "Report of the Special Committee

of the Housing and Welfare

Committee of the Chamber of

Commerce," 28 February 1914, Cincinnati

Chamber of Commerce Papers, CHS.

160 OHIO HISTORY

tenement problem. Lawrence Veiller, who

helped found the Tene-

ment House Committee of the Charity

Organization Society for

New York City in 1898, probably best

articulated the general per-

ception of the problem. Although lack

of sanitary facilities, con-

gestion, insufficient light, and

"foul cellars and courts" created an

environment of sickness, vice, and

crime which cost the entire

community in terms of additional

hospitals and police, the real

problem, according to Veiller, was

"the problem of enabling the

great mass of the people who want to

live in decent surroundings

and bring up their children under

proper conditions to have such

opporunities."7

Although campaigns to clean up the unsanitary

squalor of the

tenements had been common since the

mid-nineteenth century,

reformers at the turn of the century

were unique in that they

questioned whether any tenement could

provide "decent surround-

ings" for the urban poor. Veiller

reflected this view in the 1900

Tenement Commission Report in which he

argued that "no one

who is at all familiar with the

tenement house life in New York...

can fail to realize that the chief evil

to be remedied is the tenement

house itself."8

Still, the Veiller-led housing reform

movement in the United

States emphasized the need for tenement

improvement because

the reality of thousands actually

living in tenements demanded

some type of action to relieve the

worst problems created by poor

sanitation and over-congestion.

Employing the Progressive em-

phasis of efficiency and expertise,

housing reformers stressed a

more systematic approach to tenement

house betterment than

earlier tenement reform movements.

The "Report of the New York State

Tenement Commission

of 1900" served as an important

blueprint for housing reform

while the New York State Tenement Law,

written by Veiller and

passed as a law for the state's two

largest cities (New York City

and Buffalo) on 12 April 1901, served

as a model tenement law for

cities throughout the nation, including

Cincinnati. The latter con-

tained regulatory provisions concerning

fire controls, light and

7. Lawrence Veiller, "Housing

Problems in America," Proceedings

of the National Conference of Housing

(Cincinnati, 1913), 207-08.

8. DeForest and Veiller, eds., Tenement

House Problem, vol. 1, 5.

For a discussion of mid-nineteenth

century housing in Cincinnati, see

Alan I.

Marcus, "In Sickness and in Health: The Marriage of the

Municipal Corporation to the Public

Interest and the Problem of Public

Health, 1820-1870. The Case of

Cincinnati" (unpublished Ph.D. dissertation,

University of Cincinnati, 1979), 189-91.

Housing the City 161

ventalation, and sanitary requirements,

while the Commission re-

port emphasized the methodology of

investigation, education, legis-

lation, and strict enforcement of

regulatory laws. Contrary to

earlier reform movements, which

identified moral breakdown as

the chief cause behind housing

conditions, the early twentieth

century housing reformers believed that

a sickly tenement environ-

ment produced poor citizens.

Concentrating on the need to improve

that environment, the New York report

concluded that

It is only by providing homes for the

working people, that is, by pro-

viding them not only shelter, but

shelter of such a kind to protect

life and health and to make family life

possible, free from surroundings

which tend to lead to immorality, that

the evils of crowded city life can

be mitigated and overcome.9

By 1909, the interest in housing had

become so great that

Veiller organized the National Housing

Association (NHA), the

main function of which was to advise

cities on questions of housing

reform. Although its chief concern was

the condition of tenement

districts, nevertheless the

association's title suggests that its in-

terest included all types of housing

regulation. Funded by grants

from the Russell Sage Foundation, the

NHA attempted to coordi-

nate the housing movement more

effectively by holding yearly

meetings, beginning in 1911. When the

meeting was held in Cin-

cinnati in 1913, its executive

secretary, Lawrence Veiller, en-

couraged local residents to create a

local housing association. His

push for such an organization was based

on the premise that hous-

ing was a full-time problem, and as such

required a full-time orga-

nization devoted exclusively to that

problem. As Veiller put it:

We must recognize that we are not

sallying forth as amateurs on a

pleasant holiday into sociological

realms, but are embarked upon a

movement . . . with the most serious consequences to

the community.10

The actual creation of the Cincinnati

Better Housing League

resulted from a movement within the

Housing Committee of Cin-

cinnati's Woman's City Club in 1915.

Under the chairmanship of

Mrs. Annie P. Strong, the Committee

emphasized the familiar

Progressive goals of education and

regulation. Convinced that they

9. DeForest and Veiller, eds., Tenement

House Problem, vol. 1, 3.

10. Lawrence Veiller, "A Program of

Housing Reform," Proceedings

of the National Conference on Housing

(New York, 1911), 4.

162 OHIO HISTORY

should spur the creation of a citywide

housing association, the

women, led by Louise Pollak and Setty

S. Kuhn, launched a

series of discussions with various

individuals about founding such

a group. After gaining the support of

Max Senior, founder of the

United Jewish Charities of Cincinnati,

and Courteney Dinwiddie,

secretary of the Anti-Tuberculosis

League, the women initiated a

subscription campaign to raise $5,000,

the amount of money

Veiller suggested as necessary to

operate a housing association.11

A meeting at the Woman's City Club on

10 July 1916 created

the Cincinnati Better Housing League.

The ten persons attending

the session, presided over by Alfred

Bettman, a local and national

planning figure, appointed Setty S.

Kuhn as temporary chair-

man of the Board of Directors and

selected a committee to draw

up a constitution. They also hired E.

P. Bradstreet as the League's

executive field secretary for $125 per

month. Bradstreet, a former

reporter for the Cincinnati Post, was

directed to publicize the

city's housing needs, since "once

the public knows the facts and

desires a remedy, improvement will

follow inevitably."12 Acting

upon this mandate, the executive

secretary visited a variety of

civic, social, and labor organizations,

as well as newspapers, to

explain the city's housing ills.

The League's Constitution, adopted on

14 November 1916,

outlined how the organization would

"promote better housing,

especially in the tenements of Cincinnati."

It proposed to accomp-

lish this

... by giving the greatest publicity to

housing conditions; by urging

the enlargement of the Tenement House

Inspection Department as

needed; by promoting the improvement of

the housing regulations and

the law; by promoting better relations

with tenement house owners

and by other means as may secure better

housing conditions in Cin-

cinnati.13

The BHL, then, while concerned chiefly

with remedying the

tenement problem, differed from late

nineteenth century tenement

11. Minutes, Housing Committee of the

Woman's City Club, 25 May

1916, Woman's City Club Papers, CHS: 6

June 1916; 9 December 1915.

12. Minutes, Board of Directors of the

BHL, 10 July 1916, BHL

Papers, Urban Studies Collection,

Archival Collection of the University

of Cincinnati, 4; Houses or Homes:

First Report of the Cincinnati Better

Housing League (Cincinnati, 1919), 21.

13. Minutes, Board of Directors of the

BHL, 14 November 1916, BHL

Papers, 1-2.

Housing the City 163

reform movements in that it both

encouraged cleaning up the

tenement district and in promoting

better housing throughout the

entire city. Some BHL executive

meetings, such as the one held

jointly with the City Club on 22

November 1916, continued the

earlier reformers' concern with tenement

regulation. At that meet-

ing, the League asked its executive

secretary, E. P. Bradstreet, to

investigate carefully the state building

code and identify all those

laws relating to tenement houses. At

other sessions of the Execu-

tive Committee, however, the BHL's

leadership discussed the need

for broadening and modernizing the

housing section of the local

building code to include all types of

housing in the city.14

This new focus on citywide housing

reflected the reformers'

belief that the tenements served only as

way stations for urban

newcomers, who would eventually move up

the socio-residential

urban ladder and one day live in

single-family homes, the proper

dwelling for the city. Such a movement

was natural, according to

the reformers, so it was important to

ensure that the housing stock

throughout the city be properly

maintained for both the protection

of the current residents as well as the

future ones. Complimenting

this belief in the outward expansion of

the urban population was

the belief in the continued outward

expansion of the central busi-

ness district and its surrounding

industrial areas, a process which

would eventually doom tenements in the

Basin area to extinction.15

Nevertheless, the League continued to

commit a large percent-

age of its program to regulation and

education in the tenement

district. Adhering to Veiller's analysis

that sanitary deficiencies

were the root cause of bad housing, the

League attempted to

abolish unfit privy vaults and catch

basins, along with dark halls

and poorly-lighted interior rooms,

arguing that they created health

and social problems which threatened the

stability of the work-

ingman's family. In an environment which fostered disease,

poverty, vice, and crime, remedial

action was needed. So sure was

the League's leadership that an improved

tenement environment

would foster a better Cincinnati, they

asserted that

Today, when the world is confronted with

unrest and with the advance

of doctrines inimical to the state, the

community in which a majority

14. Minutes, Executive Committee of the

BHL and the Housing

Committee of the City Club, 22 November

1916, BHL Papers; Minutes,

Executive Committee of the BHL, 9

January 1917, BHL Papers, 2.

15. See George E. Kessler et. al., A

Park System for the City of Cin-

cinnati (Cincinnati, 1907), 32 for a sense of how contemporaries

perceived

the expanding downtown district; Houses

or Homes, 25.

164 OHIO HISTORY

of the population own their own homes,

or live in houses that are de-

cent and attractive, has little cause

to fear.16

Citywide regulation would serve the

dual purpose of remedying

some of the worst tenement conditions

and of ensuring that future

housing would never fall into such

deplorable conditions.

The League's education programs also

illustrated its concern

with both the present and the future.

Reflecting the housing

movement's interest in human as well as

physical housing problems,

these programs sought to instruct the

tenement dweller in hygienic

and social skills needed for city

living. According to the League,

the city not only had a housing problem

but also a tenant problem

because some tenants were

"ignorant, irresponsible and destructive

individuals." The BHL attempted to

combat this in several ways.

First, the executive secretary visited

all the schools in the tene-

ment district to lecture on the

importance of sunlight, fresh air,

cleanliness, and good housekeeping.

Working under the assumption

that some former tenement dwellers had

already moved to other

parts of the city, the League also

distributed to the public schools

a pamphlet entitled "Home, Health

and Happiness," which "told in

simple language" and illustrated

"by graphic pictures the things

that tenants ought to know about the

care of their homes." Essay

contests held for the eighth graders

throughout the city on "The

Proper Care of the Home"

represented another BHL effort to

educate and inform. In reporting on its

educational efforts with

the school children, the League's first

public report noted with

pride that "this systematic plan

of working for housing betterment

through the children in public schools

is not used in any other

city."17

The creation of a force of visiting

housekeepers in 1918 was

another educational response to the

tenant problem. The house-

keeping plan, developed after the city

real estate board complained

about property destruction by

"ignorant Negroes" in the city's

West End, attempted to teach tenants

"how to live properly, to

appreciate repairs and improvements

that are made for them, to be

fair with the landlord and to pay their

rent promptly." By 1923,

the League employed six housekeepers to

work with both blacks

and whites.18

16. Houses or Homes, 20.

17. Ibid., 16, 18, 24.

18. The Real Estate Board endorsed the

housekeeping plan. Ibid.,

26; Minutes, Board of Directors of the

BHL, 14 February 1918, BHL

Papers; Ibid., 15 January 1918; Ibid.,

13 November 1923.

|

Housing the City 165 |

|

|

|

The League also conducted housekeeping institutes "in the heart of the congested colored district" in the Basin's West End which offered instruction in sewing, in cooking, and "in the rights and duties of tenants." According to one BHL report, the house- keepers and the institute were not only helping tenement residents to cope better with their present needs, but were preparing them "to take proper care of the better types of houses which we hope they may be able to live in in the future."19 Another emphasis of the BHL demonstrated its broadening interest with housing rather than just tenements. Although model tenements had been popular in the late-nineteenth century, hous- ing reformers such as Veiller dismissed them in the early-twentieth century as "merely palliative and distractive" because of their limited influence. But with the war-induced housing shortage, the League sought to provide needed shelter for the poor. The Board of Trustees, in fact, discussed such stopgap measures as the fund- ing of a Better Housing Company to buy ill-kept tenements and

19. Housing in Cincinnati. Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow: Annual Report of the BHL of Cincinnati and Hamilton County (Cincinnati, 1929), 7. The first annual report also discussed "the movement from our tene- ments to homes in the suburbs." Houses or Homes, 25. |

166 OHIO HISTORY

repair them to rent. When funds proved

unavailable, they attempt-

ed to persuade firms such as Proctor and

Gamble to build working-

men's houses. Although this plan

failed too, it suggested that the

League was more concerned with the

building of new houses than

of new model tenements to combat the

housing shortage.20

By the time the BHL was established,

then, reformers had

expanded their area of interest from the

tenement district to the

whole city. This meant that they now

crusaded for regulatory

laws to prevent the newer houses from

deteriorating to the poor

conditions of the Basin tenements. The

League's educational pro-

grams also tried to equip the tenement

dweller with the necessary

hygienic and social skills to be a good

city neighbor. Such a program

seemed important since the tenement no

longer was viewed as the

permanent residence of the poor, but

rather as an entering point

for people on the track of socioeconomic

and residential mobility.

The League's 1920 Annual Report best

revealed this vision of the

tenement as a temporary and

unsatisfactory residence when it

suggested that

Tenement houses do not provide real

homes. No matter how well con-

structed, they are not the best place to

live in. They make home owner-

ship impossible. What Cincinnati and

every other city in the country

needs is not more tenement houses, but

more small homes, where each

family may live unto itself with a place

for the children to play-a

home which the family itself may own.21

The vision of a dynamic and expanding

city, with an outward

moving population and spreading central

business district, also

reinforced the League's belief that

regulation and education would

solve Cincinnati's housing needs. When

the BHL mentioned in its

first report in 1919 that it wanted to

be able to boast that "Cin-

cinnati is a city of homes" that

has "no slums," it was not suggest-

ing that the city or private

organizations instigate a massive slum-

clearance project. Rather it reflected

the idea that the city would

continue to expand and the slums would

wear out or be replaced

by the expanding downtown business and

commercial section. Such

20. Lawrence Veiller, Housing Reform:

A Handbook for Practical

Use in American Cities (New York, 1910), 70. The chapter's title from

which the quote came was "Tenements

and Their Limitations." Minutes,

Board of Directors of the BHL, 17 September

1918; Houses or Homes, 25;

Minutes, Executive Committee of the BHL,

4 June 1919, 1, BHL Papers.

21. Housing Progress in Cincinnati:

Second Report of the Cin-

cinnati Better Housing League (Cincinnati, 1921), 28.

Housing the City 167

a perception of the city gave the

League a cautious optimism that

the housing problem could be eradicated

by concentrated and effec-

tive action.22

II

The organizers of the BHL, who shaped

the League on the

principles of coordination and

scientific investigation, hoped to

develop a centralized organization

solely devoted to housing better-

ment so they could successfully analyze

and attack the housing

problems threatening Cincinnati.

Towards this end, the BHL

conducted numerous housing surveys on

Cincinnati housing condi-

tions, such as the tenement survey of

1918, and became an import-

ant data bank for both private and

public agencies to consult.23

Despite this action and others such as

the hiring of a new executive

secretary and the joining of a central

fund-raising organization,

both attempts to make the League an

even more efficient housing

association, much of the BHL's

leadership's optimism about solving

the city's housing problems waned, for

the twenties proved a

difficult and trying time for the

reformers.

By luring Bleecker Marquette away from

New York City to

become executive secretary of the BHL

on 1 September 1918, the

city gained a proven housing expert.

Marquette, who had worked

with Lawrence Veiller for three years

as assistant secretary of the

New York State Tenement Committee,

brought both knowledge

and expertise to the local reform

movement. The League hired

Marquette for a yearly sum of $3,000, a

figure double the salary

of E. P. Bradstreet, the organization's

first executive secretary.

That seemed justified since the new

head would provide the

analytical skills deemed necessary for

a successful organization.24

Another important decision by the

League's board members

was to join on 12 October 1917 the

Central Budget Committee of

the Council of Social Agencies.

Reflecting the era's emphasis on

centralization and coordination, this

federation of charitable, civic,

22. Houses or Homes, 3.

23. The 1918 survey (published in 1921)

investigated four "typical"

sections of the city's Basin area to

ascertain how prevalent were the

sanitation evils of the yard toilet,

dark or interior rooms, and room con-

gestion. A Tenement House Survey in

Cincinnati (Cincinnati, February,

1921), 2. Other surveys included an

investigation of the area surrounding

Ivorydale in 1918; a tenement house

survey of the 16th, 17th, and 18th

wards in 1926; and a yearly rental

survey. Marquette, Twentieth Annual

Report, 2.

24. Minutes, Special Meeting of the

Board of Directors, 7 June 1918,

BHL Papers.

168 OHIO HISTORY

philanthropic and public agencies of

Greater Cincinnati helped

manage much of the social and health

work in the community. By

joining the Council's Central Budget

Committee, composed of

twenty-nine agencies which pooled their

resources for joint con-

sideration of individual budgets after

conducting a single fund-

raising drive, the BHL freed itself

from financial dependence on

its own membership, which had collected

revenue for the organiza-

tion from friends and relatives.25

Membership in the Council also

signaled to the city that the mechanics

of a housing association

had been dealt with, and that the

League now stood ready to be-

come a significant force within

Cincinnati.

Almost from its inception, the League's

vision of an orderly,

expanding, and outward-growing city

where it was possible to move

on to better homes appeared threatened

by the war-induced hous-

ing shortage. Citing the scarcity of

building materials and the

flood of black migrants coming to work

in the city's factories as

causes, the League altered its emphasis

from regulation to alleviat-

ing the city's over-crowded condition.

Fearful that a housing

shortage would interfere with the

step-up process of the dynamic,

outward-growing city, the BHL concluded

that only by "housing

the city" could the problem be

remedied. Its 1921 Annual Report

proclaimed that "Cincinnati is so

far behind in its supply of houses

that every practical plan that will

provide more good houses is

urgently needed." In the same

report, Marquette pointed out that

the League's emphasis had changed from

getting rid of slum

conditions to that of providing shelter

for the working class.26

This theme dominated much of the

League's board meetings

between 1921 and 1925, and during these

years BHL members also

realized that housing shortages not

only threatened tenement

dwellers, but the middle class as well.

Bleecker Marquette, speak-

ing at the National Conference on

Social Work in 1923, analyzed

the situation and concluded that

Not for decades has the housing problem

been so acute as during the

past 2 or 3 years. For almost the first

time in recent history it has

ceased to be a problem for the submerged

tenth alone and has squarely

hit the people of moderate means. They

are better able to understand

25. Minutes, Board of Directors of the

BHL, 12 October 1917, BHL

Papers; Cincinnati Social Service

Directory, 1918-1919 (Cincinnati: Coun-

cil of Social Agencies, n.d.), 20-22.

26. Housing Progress in Cincinnati, 4,

11.

Housing the City 169

today a thing that our underpriviliged

classes have long understood-

what it means to lack an adequate supply

of houses at reasonable cost.27

Despite Marquette's concern for the

middle class, Cincinnati

blacks still suffered most from the

shortage. In 1922, the League's

annual report observed that the

"situation among colored families

is almost desperate." Not only had

work opportunities attracted

an enormous influx of blacks to a city

already experiencing a hous-

ing shortage, but residential

segregation in Cincinnati prevented

more affluent blacks from moving out

from the central city

ghetto. Further contributing to the

congestion, according to the

BHL's report, was "the replacement

of blocks of houses in the

lower river district by large business

houses and clubs."28 Nowhere

was the congestion greater than in the

West End of the Basin,

particularly the 15th through 18th

wards, where the Negro popu-

lation had doubled from 8,647 to 17,207

between 1910 and 1920.29

The overcrowding had lured speculators

who traded and bought

tenements, raised rents, and reaped

economic benefits while blacks

suffered. High rents, which had tripled

in some instances between

1918 and 1922, resulted in cases of

families doubling and tripling

up in some West End flats. A

housekeeper for the League reported

that twenty persons lived in a

three-room flat on 1131 Hopkins

Street. Another twelve-room tenement on

324 George Street con-

tained ninety-four occupants. After

observing such conditions, Dr.

Haven Emerson reported to the Public

Health Federation that

You could not produce a prize hog to

show at a fair under the con-

ditions that you allow Negroes to live

in, in this city. Pigs and chickens

would die in them for lack of light,

cleanliness and air.30

The League responded to both the

housing shortage in general

and the Negro congestion in particular

by looking for alternatives

to what it identified as a fragmented

private housing industry. The

decision to form a limited dividend

housing company, based on the

27. Bleecker Marquette, "The Human

Side of Housing: Are We Losing

the Battle for Better Homes?" Proceedings

of the National Conference on

Social Work (Washington D. C., 1923), 344.

28. "Housing Progress," Report

of the BHL (typewritten), Cincin-

nati, 1922, CHS, 1.

29.

Thirteenth Census of the United States, 1910: Population, 3: 427;

Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920:

Population, 3: 799-800.

30. Minutes, Executive Committee of the

BHL, 13 November 1923, 1;

The Housing Situation Today: Report

of the BHL (Cincinnati, 1925), 2.

170 OHIO HISTORY

principle of restricted profits, was one

such attempt to avoid the

problems which had impeded the small,

private contractors' build-

ing efforts. The BHL housing company's

ability to buy its ma-

terial in quantity and eliminate cost

duplication in areas such as

architectural fees might provide the

savings needed to build low-

cost homes, if the company had expert

leadership. Therefore, in

1919 a League committee, headed by

Jullian A. Pollak, hired John

Nolen, the famous city planner (and

future developer of the Cincin-

nati area's model new town, Mariemont),

to advise the club's newly-

formed housing company.31

Although the company originally planned

the building of low-

cost homes, its members concluded after

reviewing a survey taken

in 1920 "that it would be

impossible to construct houses at that

time within the reach of the ordinary

workingman." Instead, the

company would construct houses for

"those with a higher income

with a view to relieve the pressure from

the top." The League

failed even in this objective, however,

because it could not raise

enough money for the company and thus

abandoned its plan in

February, 1922.32

Having fallen short with its

construction scheme, the League

turned to other alternatives in dealing

with the housing shortage.

When requested by the Community Chest to

help combat the

terrible congestion within the city's

black sections, the League

created a special committee on Negro

Housing which first met on

4 February 1924 to develop a strategy

for dealing with the crisis.

Noting the impossibility of building new

homes for poor blacks

because of high construction costs, the

committee urged an in-

crease in regulation and educational

activities, hoping that these

"temporary measures" would

allow some limited progress "in

cleaning up and keeping in reasonable

repair the tenement houses

in the West End Section of the city, and

in other parts of the city

where housing conditions are bad."33

The Negro Housing Committee also urged

greater financial

support for the Model Homes Company, a

limited dividend housing

company which had been building houses

and apartments since

1915 on the policy of philanthropy and 5

percent profit. As a

31. Letter, Bleecker Marquette to Alfred

Bettman, 27 September

1919, Cincinnati Better Housing League

Papers (CBHL), CHS; Housing

Progress in Cincinnati, 7-9.

32. Housing Progress in Cincinnati,

9.

33. Minutes, Special Committee on the

Negro Housing Problem, 4

February 1924, BHL Papers.

|

Housing the City 171 |

|

|

|

consequence of its belief in private housing projects, the committee recommended that a million dollars be raised for the Model Homes Company, since "the present situation can't be relieved materially without the constructing of more houses."34 Inflation had raised building costs from $1,400 a flat in 1915 to $3,750 a flat ten years later, limiting the company's ability to build for the neediest; but, according to the League, additional housing for anyone was im- portant since only then would "the old procession [be] once more started from the poorer houses to better houses and so make avail- able to families of small means the old but adequate houses that are still habitable."35 Like the construction scheme, this plan also failed as the League's campaign drive failed to raise the necessary money, and thus the houses were not built.

34. Ibid.; According to the League in 1921, "Cincinnati is so far be- hind in its supply of houses that every practicable plan that will provide more homes is urgently needed." Housing Progress in Cincinnati, 11. 35. John Ihlder, "Extent of the Housing Shortage in the U.S.- |

172 OHIO HISTORY

Despite its interest in the health and

welfare of Negroes, the

League's philanthropic concern and

racial tolerance had boundaries.

When in 1924 blacks started moving into

the Mohawk-Brighton

district due "to speculative

dealers buying tenement houses in

white neighborhoods and selling or

renting to colored tenants," the

BHL Board of Directors called it a

"momentous problem." Fearful

of the "outbursts of violent

feeling and bitterness" that block-

busting might prompt, the Board

instructed its housekeepers to

dissuade blacks from moving into white

neighborhoods. The Board

then discussed what it felt to be the

problem's real solution, which

was "finding room for expansion of

the colored people in this city

without this scattering in the

neighborhoods."36 Although bene-

volent, the League nevertheless made no

effort to integrate blacks

into white neighborhoods. Outward

residential mobility for indi-

vidual blacks still depended on the

availability of new outlyng black

neighborhoods.

Because the League believed that the

housing shortage posed

only a temporary threat to the orderly

expanding and outward-

growing city, it continued to

concentrate much of its emphasis on

regulation and education as important

housing tools throughout

the twenties. In fact, the League's

budget showed a substantial

increase in expenditures for visiting

housekeepers, who performed

the dual activities of teaching urban

living habits to the influx of

urban newcomers and acting as trouble

shooters to alert the League

to the very worse cases of overcrowding

in the tenement district.

Typifying the League's continued and

expanding interest in

regulation was its support of zoning

proposals, including one which

would divide the city into districts

and "limit the heights of build-

ings and prescribe the size of open

spaces for light and ventila-

tion."' Such an ordinance would

"insure the proper development

of the city by protecting residential

districts from invasion by

business buildings or big

industries." The BHL also approved of

zoning because it would promote the

house as the proper city dwell-

ing by preventing "the development

of slums and tenements in the

suburbs." A special zoning

committee of the BHL cited other

salutary affects of zoning and

proclaimed that

Its Economic and Social Effects,

Resources Available in Dealing With

It," Proceedings of the National

Conference on Social Work (Milwaukee,

1921), 332; Minutes, Board of Directors

of the BHL, 10 October 1922, BHL

Papers.

36. Minutes, Board of Directors of the

BHL, 7 October 1924, BHL

Papers.

Housing the City 173

We believe it will do more to prevent

congestion and bad housing and

to promote the development of good

housing standards in the future

more than any other single measure

proposed for the city in years.37

Not only did the League's concept in the

twenties of regula-

tion broaden from legislating housing

standards to zoning, but its

unit of concern also changed from the

city to the greater metro-

politan area, reflecting an increased

nationwide interest in the

metropolis. The League's newly

incorporated name in 1929-The

Better Housing League of Cincinnati and

Hamilton County-

symbolized its new interest. The League,

noting how the lack of

regulatory laws for the areas just

outside the city's boundaries

resulted in poor construction and

uncontrolled development, as in

"some Negro subdivisions beyond

Lockland and Glendale," sup-

ported county zoning and pushed the

creation of the Hamilton

County's Regional Planning Commission on

22 March 1929. In this

connection, the League reported that

It is our task to see that all homes

built hereafter are built right and

this applies not to the city alone, but

to the metropolitan area. Adoption

of the revised zoning ordinance,

completion of the new building code,

and effecting the regional plan are all

essentials.38

By 1926 the city's housing shortage had

eased enough to per-

mit the League some of its earlier

optimism. In that year, Bleecker

Marquette observed the "marked

improvement in tenement housing

conditions" and noted that "at

no time in the city's history has

greater progress been made" in

improving local housing conditions.

For the next three years, the minutes of

the League's Board of

Directors meetings brimmed with reports

of success by the

League's housekeepers and the city's

housing department. Statisti-

cal accounts of the number of structural

repairs, room renovations,

and demolitions of uninhabitable

dwellings usually occupied the

first several pages of the Board's

minutes.39

37. Houses or Homes, 24; Minutes,

Committee on Zoning Ordinances,

11 December 1923, BHL Papers.

38. Minutes, Board of Incorporators of

the BHL of Cincinnati and

Hamilton County, Inc., 16 May 1929, BHL

Papers; Minutes, Board of

Directors of the BHL, 19 April 1928, BHL

Papers, 1. The League was

particularly concerned about the Steele Subdivision.

These "slums" in the

suburbs were a "threat to orderly

growth." Housing in Cincinnati: Annual

Report of the CBHL (Cincinnati, 1928), 20.

39. Bleecker Marquette, "Progress

in Cincinnati," Housing Better-

ment: A Journal of Housing Advance (February, 1927), 98-100. Not only

did the minutes of the Board meetings

contain statistical accounts of

174 OHIO HISTORY

Despite the apparent success of the BHL,

one persistent diffi-

culty remained-meeting the demand for

low cost housing. Even

the resumption of construction, which

alleviated the middle class

housing shortage, did little to aid the

city's poorer families, who

were still crowded together in older,

inadequate dwellings. The

"trickle down" process of

housing did not fulfill its promise, and

the BHL leadership had learned in the

1920s that neither private

enterprise nor limited-dividend

companies could meet the housing

demand.40 The BHL Annual

Report for 1929 summarized the

problem by explaining that

Without question the great challenge in

the field of housing is how to

build satisfactory new homes at prices

our families of moderate means

can afford. . . . There is no problem

more deserving of constructive

thought.41

The title of the 1930 Annual Report, Housing:

Forward or

Backward, was symptomatic of the BHL's dilemma. The report

included impressive accounts of

improvements carried out that year

by the League in the realm of tenement

betterment and tenant

education. But the report also admitted

that the city's housing

problems remained, and would not be

resolved for many years. This

view of reality led the League to blame

the city's past neglect of

its housing needs for its current

difficulties. It argued that

If Cincinnati had had, seventy-five

years ago, a modern housing law,

an up-to-date building code, a zoning

system and a city plan to guide

and regulate construction, there would

be practically no housing prob-

lem in our city today.42

The adherence to the model of a dynamic

city, with both

business and people moving out, limited

the League's definition

and solution of the housing crisis.

During the twenties, the chief

problem was that "the tendency for

families to move out of the

basin tenements into the suburbs ... as

the old Tenements [wore]

success, but so did the annual reports.

See, for example, Minutes, Board of

Directors of the BHL, 19 April 1928, BHL

Papers; and Housing in Cin-

cinnati. Yesterday, Today and

Tomorrow (1929), 5.

40. Housing in Cincinnati (1928),

16. At the peak of the shortage,

the BHL estimated that the city was

4,000 to 5,000 houses short. Minutes,

Board of Directors, 9 January 1923, BHL

Papers.

41. Housing in Cincinnati. Yesterday,

Today and Tomorrow (1929), 7.

42. Housing, Forward or Backward:

Better Housing League Annual

Report for 1930 (Cincinnati, 1930), 4.

Housing the City

175

out or [were] displaced by business and

industrial structures" had

been checked by the "scarcity of

houses." To solve the problem

meant increasing the housing supply,

whether through industry-

sponsored housing or more expensive

town projects like Mariemont,

which eased "the pressure from the

top."43

Not only had houses not filtered down

in adequate numbers

to the neediest, but it appeared that

the central business district

(CBD) would no longer eradicate the

tenement district since the

city's growth had practically ceased.44

After conceptualizing this

new model of non-growth in Cincinnati

during the late 1920s,

League members began wondering

publically if the housing prob-

lem could be resolved merely by housing

regulation and education.

Slum clearance by the government became

a new option for some

of the League leadership. Bleecker

Marquette discussed such an

alternative in the 1928 BHL Annual

Report, in which he pointed

out that " . . . such a method as

slum clearance would offer a much

quicker solution and would be a great

boon to the city health and

general welfare." Nevertheless, he

concluded, "it is idle to discuss

it, because we know that our old

tenements will be won out and

gone before public opinion of America

reaches the point where it

would support such a proposal.45

III

By the early thirties, the League acted

on its new vision of

a more static Cincinnati with a

non-expanding central business

district.46 This conception

of the city, differed from the earlier

one that had pictured constant outward

expansion for all parts of

the city, including the central

business district, and caused the

43. Apparently the Mariemont project,

Mary Emery's attempt to

build a garden community in the

twenties, provoked much criticism from

certain groups within the city. The BHL

felt obliged to defend it throughout

the decade, noting there had been

"much misunderstanding about it."

Housing Situation Today, 5.

44. As early as 1925, The City Plan of

Cincinnati emphasized the

city's slow growth and suggested that

was the norm. Cincinnati City

Planning Commission, The Official

City Plan of Cincinnati, Ohio (Cin-

cinnati, 1925), 7-8.

45. Housing in Cincinnati (1928),

16.

46. After 1930, the Great Depression

worsened housing problems

and reinforced the League's sense of its

ineffectiveness. It also caused a

serious financial problem for the BHL,

which resulted in both decreased

salaries and a smaller staff. Unable to

solve the housing problem, the

League in the early 1930s shifted its

immediate emphasis to relief and

helped the city's welfare department by

finding shelter for dispossessed

families. Trend Today in Housing, 16.

|

176 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

League to look outside the city for help. It did this by taking two important steps. First, on the state level, members of the BHL- particularly Alfred Bettman and Bleecker Marquette-helped Ernest J. Bohn, a Cleveland housing reformer, draw up and lobby for a state enabling act to permit the creation of local metropolitan housing authorities. Those organizations would permit more effi- cient use in Ohio of federal monies authorized by the National Re- covery Act of 16 June 1933, which created the Federal Emergency Administration of Public Works to lend funds and make grants to public corporations for public housing and slum clearance.47 The Cincinnatians' actions helped Ohio pass on 30 August 1933 the

47. Mel Scott, American City Planning Since 1890: A History Com- memorating the Fiftieth Anniversary of the American Institute of Plan- ners (Berkeley, 1970), 325. |

Housing the City 177

nation's first state enabling

legislation for forming metropolitan

housing authorities.48 Second, at the local level, the League

worked actively to secure federal funds

as well as to help direct

favorable public opinion in Cincinnati

toward public housing. For

this purpose the League on 27 September

1933 created the Citizens'

Committee on Slum Clearance and Low

Cost Housing. At its first

meeting, temporary chairman August Marx

announced the ration-

ale behind the new organization. The

League wished to

..

launch a separate committee from the BHL which might take as

its object the promoting of the best

possible program for the con-

struction of low cost housing and slum

clearance in Cincinnati under

the possibilities offered by the Public

Works Administration of the NRA

in the manner of loans for these

purposes.49

Not only would the committee keep in

touch with the housing con-

ditions and formulate plans for

attracting federal monies, it would

also educate public opinion to the need

for federal housing by pro-

viding local newspapers with favorable

information and by speak-

ing out in favor of public housing at

the city's various clubs and

community organizations.

One of the Citizens' Committee's most

important undertakings

started on 8 November 1933 when it

requested the State Board of

Housing to sanction the formation of a

public housing authority

for the city. As a result of the

request, the Cincinnati Metropolitan

Housing Authority, staffed with five

candidates, four of which

were recommended by the Citizens'

Committee, began operations

on 7 December 1933. The membership of

the five-man authority

charged with developing plans and

applying for federal assistance

for housing development and slum

clearance included three promin-

ant BHL members: Setty S. Kuhn, Stanley

Rowe, and Charles

Urban.50

The Housing Authority, with the

cooperation of the BHL and

the Citizens' Committee, introduced

federal slum clearance and

public housing to Cincinnati. Its first

effort, Laurel Homes, a

48. Developments in Housing: BHL

Annual Report for 1934 (Cin-

cinnati, 1934), 1-2.

49. Minutes, Citizens' Committee on Slum

Clearance and Low Cost

Housing, 27 September 1933, BHL Papers.

50. Ibid., 8 November 1933; 31

October 1933; Trend Today in Hous-

ing 6. The

League also furnished executive, secretarial, and a variety

of other services for the Housing

Authority, including office space.

"Progress by Local and State

Agencies," Housing Officials' Yearbook,

1938, 100.

178 OHIO HISTORY

West End public housing project on the

edge of the central business

district, initiated in 1933 and

completed in 1938, was made possible

in part by a redevelopment plan for

that area drawn up in 1933 by

the BHL and the City Planning

Commission.51 The BHL also

conducted survey work for the Housing

Authority and, according

to Marquette, explained the Authority's

programs to the city.

One needs only to examine the League's

annual reports between

1933 and 1939 to appreciate the

inordinate amount of attention

the BHL Board of Directors gave the

federal projects. For ex-

ample, 20 of the 37 pages of minutes

for the 1934 Board of

Directors monthly meetings contained

discussions of the projects,

while in the 1937 meetings 25 of 37

pages of minutes dealt with

federal housing activities.

The League reaffirmed the commitment to

slum clearance in

its 1935 comprehensive housing policy

proposed for metropolitan

Cincinnati. The policy, which received

the approval of the City

Planning Commission, divided the

metropolitan community into

parts, creating programs best suited

for each area. For the newly-

developed areas, zoning and housing

codes would preserve good

housing conditions; but for the slum

areas, the focus shifted from

just eliminating a condition to

eliminating a geographic entity-

a slum area. All the housing in that

district was by definition

part of the slum, and hence to be

destroyed and replaced.52

The emphasis of the housing policy on

slum demolition and

rebuilding, which Marquette called in

1936 "the only intelligent

solution," illustrates that the

view of the city's Basin area as only

the first step in a dynamic process, a

temporary residence, had

given way to a more static view of the

city and its potential for

some residents.53 Although

the city's Basin population declined

by 40,000 people between 1910 and 1930,

the housing problem in

the thirties was perceived as more

serious since the tenement

population had less chance of moving

out.54 Therefore, housing

had to be established for the

"unskilled wage-earner unable to

51. Bleecker Marquette, "History of

Housing in Ohio," speech pre-

sented to the Conference of the Ohio

Housing Authority, Youngstown,

Ohio, 9 June 1939, 8, BHL Papers. The

Planning Commission made an as-

sortment of studies on the West End,

including investigations of inadequate

housing facilities, overcrowded

conditions, population trends and distribution,

traffic counts and delinquency. Municipal

Activities of the City of Cincin-

nati, 1934 (Cincinnati, 1934), 29. Page 30 has a map of their

plans.

52. Bleecker Marquette, "A Housing

Policy-And Planning," Plan-

ners' Journal (Winter, 1936), 9.

53. Marquette, Twentieth Annual

Report, 4.

54. Ibid., 2.

Housing the City 179

meet the cost of a satisfactory

standard of housing provided by

commercial enterprise or limited

dividend housing corporations."55

As a result, according to the League's

1939 Annual Report, the

most valuable service which BHL-like

organizations could provide

would be to make "Cincinnati ready

to take advantage of federal

government funds for getting

underprivileged families out of the

slums."56

That same report, discussing the merits

of its earlier concern

for housing regulation, admitted that

this approach had failed to

solve the city's housing problems.

Still, it reaffirmed that "the

years that Cincinnati had devoted to

the effort to control the

housing situation by legislation have,

by no measure, been wasted,

nor are they today any less

necessary."57 The BHL felt it had

created an important foundation for

later housing improvement.

Even more important, since the early

thirties when the League

had identified public housing "as

the only way out," it helped

establish and promote organizations

such as the Citizens' Com-

mittee on Slum Clearance and Low Cost

Housing, and the Cincin-

nati Metropolitan Housing Authority,

institutions critical to the

development of Cincinnati's

federally-sponsored slum clearance

and public housing.

Such a strong advocacy of federal

housing made the League

a somewhat controversial organization

during the thirties and,

in fact, alienated some of its former

financial contributors. For

example, the local Real Estate Board

and the Home Builders Associ-

ation strongly disapproved of the

League's endorsement of public

housing and attempted to force the

Community Chest to withdraw

its financial support from the BHL.58

The League, sensitive to its

critics, often discussed its espousal

of those projects in apologetic

terms, explaining on one occasion that

55. Marquette, "A Housing

Policy," 10. Earlier in 1933, the Federal

Public Works Administration had offered

limited dividend projects 85

percent of the cost of the building

program for only 4 percent interest.

Five Cincinnati companies applied for

money, but all were unable to raise

the required 15 percent. One applicant,

Ferro Concrete Construction Com-

pany, noted that even with the loan its

rent on the dwellings would still

be out of the range of most West Enders.

The program's failure in Cin-

cinnati and elsewhere suggested that

limited dividend companies could not

meet the need. Trend Today in

Housing, 2.

56. Bleecker Marquette, The Better

Housing Reports for the Year

1939 (Cincinnati, 1939), 2.

57. Ibid.

58. Letter, Tom McElvain to Harold

Riemeiser, 24 April 1957, BHL

Papers; Bleecker Marquette, Health,

Housing and Other Things: Memoirs

By Bleecker Marquette (Cincinnati, 1972), 83.

180 OHIO HISTORY

For over twenty years we worked to

improve by every means at our

command and particularly trying to find

ways and means by which

private builders could meet the need. We

did not succeed.... Without

a subsidy, the problem of an adequate

supply of decent low rent

housing is insoluable.59

The League's new solutions, then,

reflected its changing con-

ception of the city. At its founding in

1916, the BHL viewed the

city as dynamic and expanding, capable

of assimilating newcomers

from its tenement areas into used houses

which would "filter

down" to the tenement dwellers. By

the early twenties, Cincin-

nati's housing reformers faced an apparent

breakdown of the old

system because of the war-induced

housing shortage and the

migration of thousands of blacks into

the city. Houses stopped

filtering down, and race relations

became tense as competition for

housing space increased. The League

continued its emphasis on

housing regulation and education and, in

fact, expanded its interest

to the Cincinnati metropolitan area, but

identified the housing

shortage as the real problem and

supported a variety of endeavors

to relieve it. The failure to resolve

that problem led Bleecker

Marquette and several other BHL leaders

to support the idea of

positive governmental housing assistance

prior to the Great De-

pression.

The BHL's call for federal action was,

in part, a response to

its new perception that the city's

central business district and

surrounding industrial areas would no

longer be expanding. Since

there was no longer any guarantee that

the CBD's growth would

destroy the city's rundown areas, or

that there no longer existed

an avenue of escape for the tenement

resident by the "filtering

down" process, BHL officials turned

their attention toward clear-

ing and redeveloping the city's worst

residential areas. The Lea-

gue, unable itself to master or gather

resources needed for such

massive redevelopment, identified the

federal government as the

only possible agent of change. As a

consequence of this new

awareness, the BHL transferred its

previously-held role of housing

leadership to the federal government for

the good of the Cincin-

nati metropolitan community.

59. Marquette, The BHL Reports for

1939, 1.

ROBERT B. FAIRBANKS

Housing the City: The Better Housing

League and Cincinnati, 1916-1939

A varity of historians have dealt with

the housing movement

in America prior to the Great

Depression, examining how the

reformers viewed the housing needs

around them. Robert H.

Bremner in From the Depths explained

how the environmental

emphasis of Progressive housing reform

reflected the changing

view of poverty from the mid-nineteenth

century notion which

had blamed individual moral breakdown.

Roy Lubove emphasized

the leadership and influence of Lawrence

Veiller, stressing his

narrow definition of the issue as one of

poor sanitary conditions

needing sanitary and structural

regulatory improvement. And in

his study of housing reform in Chicago,

Thomas L. Philpott em-

phasized how the reformers' concern with

order and stability

colored their perception of the

problem.1

Despite these various approaches to

housing reform, little

effort has been made to analyze the

housing reformers by examin-

ing their changing conception of the

city.2 Such an inquiry might

Robert B. Fairbanks is a Ph.D. candidate

in history at the University

of Cincinnati. The author wishes to

acknowledge and thank Professor Zane

L. Miller, University of Cincinnati, for

helping the author clarify the

argument of this essay.

1. Robert H. Bremmer, From the

Depths: The Discovery of Poverty in

the United States (New York, 1956); Roy Lubove, The Progressives and

the Slums: Tenement House Reform in

New York City: 1890-1917 (Pitts-

burgh, 1963); Thomas L. Philpott, The

Slum and the Ghetto: Neighborhood

Deterioration and Middle-Class Reform in Chicago,

1890-1930 (New York,

1978). Also see Lawrence M. Friedman, Government

and Slum Housing:

A Century of Frustration (Chicago, 1968); Mark I. Gelfand, A Nation of

Cities: The Federal Government and

Urban America, 1933-1965 (New

York, 1975); Anthony Jackson, A Place

Called Home: A History of Low

Cost Housing in Manhattan (Cambridge, 1976).

2. Examples of how the public's changing

conception of the city in-

fluence the way they perceive specific

urban problems can be found in

(614) 297-2300