Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

- 34

- 35

- 36

- 37

- 38

- 39

- 40

- 41

- 42

- 43

- 44

- 45

- 46

- 47

- 48

- 49

- 50

- 51

- 52

- 53

- 54

- 55

- 56

- 57

- 58

- 59

- 60

- 61

- 62

- 63

- 64

- 65

- 66

- 67

- 68

- 69

- 70

- 71

- 72

- 73

- 74

- 75

- 76

- 77

- 78

- 79

- 80

- 81

- 82

- 83

- 84

- 85

- 86

- 87

- 88

- 89

- 90

- 91

- 92

- 93

- 94

- 95

- 96

- 97

- 98

- 99

- 100

- 101

- 102

- 103

- 104

- 105

- 106

- 107

- 108

- 109

- 110

REPORT OF FIELD WORK

CARRIED ON IN THE MUSKINGUM, SCIOTO AND

OHIO VAL-

LEYS DURING THE SEASON OF 1896, BY

WARREN KING

MOOREHEAD, IN CHARGE OF EXPLORATIONS.

PREFACE.

It is interesting to note that as

general archaeology pro-

gresses in the United States, men are

more inclined to confine

their observations to special or limited

areas. A generation ago,

before the Government, the Museums of

our various cities and

the Scientific and Historical Societies

undertook large explora-

tions, it was possible for one observer

to cover the whole of the

American field from the mouth of the St.

Lawrence to Mexico.

Later, as anthropologic science

advanced, one essayed to write of

the Mound Builders, another on the Cliff

Dwellers and yet an-

other upon the antiquities of Central

America. To-day, scientists

have so specialized that volumes may

indeed be written upon the

prehistoric remains of one river

valley. This is the natural out-

come of much study and investigation.

What is true of every

other science is also true of that most

important branch of An-

thropology-prehistoric archaeology. In

the past it was suffi-

cient to briefly describe our mounds and

earthworks, give their

measurements, enlarge upon their

supposed character and pur-

pose, etc. Most of our archaeologists in

this modern age follow

the natural history method, which, by

the way, is by far the

safest and most satisfactory, and study

every little pottery frag-

ment, flint implement, bit of shell or

worked tool as carefully

and persistently as does the

palaeontologist his fossil. With

them, it is not so much the prettiest

and most perfect specimen,

but all the specimens which tell

the story. A mound is explored

by them, not for what it contains, but

because something may

be learned from its examination. The

rude hammer stone*-an

* In this connection, Archaeologist J.

D. McGuire well remarks:

"The hammer is homely at best, and

is less sought for by collectors, but

from an archaeological standpoint the

hammer tells us more of ancient

times than does the celt."

(165)

166

Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

object of contempt among ill-trained

collectors of only fantastic

objects,-the arrow head, the pottery

sherd and the bones from

the mound are religiously placed by

themselves in one of the

museum trays. Finds, poor though they

may be, from other

mounds are similarly treated, and in the

museum do they study

the mounds of the whole valley and

compare the testimony with

that of another.

Our Society must carry on this detailed,

local work, if it

would cover the State thoroughly and

obtain the most satis-

factory results.

Indeed, our work done otherwise, fails

to extend archaeo-

logic knowledge and will surely bring

upon our heads the con-

demnation of future generations. During

the season described

in this report our party constantly bore

in mind the importance

of local work and endeavored to make

thorough the explora-

tion of each section visited.

To Mr. Walter O'Kane I am indebted for

assistance during

the trip down the Muskingum from its

source to McConnelsville.

Mr. O'Kane acted as photographer and

also rendered valuable

services in directing the laborers at

Coshocton and Duncan's

Falls.

Mr. Clarence Loveberry accompanied me

through Brush

Creek Valley, along the Ohio River to

Portsmouth and up the

Scioto to Richmondale. Having had three

summers' experi-

ence in the field, Mr. Loveberry took

charge of the men in my

absence. I am especially indebted to

him for the exploration of

the Harness Mound (which was carried on

largely under his

supervision) and for assistance in Perry

County and at the Great

Stone Mound of the Reservoir.

I desire to thank Mr. Clinton Cowen, C.

E., of Cincinnati,

for ground plans and surveys of the

works on the Scioto and

along the Ohio. Mr. Cowen was with our

party two weeks.

To the following ladies and gentlemen,

the Ohio Archaeo-

logical and Historical Society, the Ohio

State University and our

survey are indebted for permission to

excavate upon their lands,

for personal courtesies and for

information as to mounds, etc., to

be located upon the State map:

Report of Field Work. 167

Mr. Alderman, McConnelsville.

Mr. C. Ackerwood, Dresden.

Mr. F. E. Bingman, Jackson.

Mr. T. M. Bright, Chagrin Falls.

Mr. William Beaumont, Alexandria.

Mr. W. S. Bradshaw, Hanging Rock.

Gen. R. Brinkerhoff, Mansfield.

S. H. Binkley, Alexandersville.

Mr. G. F.Bareis, Canal Winchester.

Mr. Briggs, Portsmouth.

Mr. J. W. Barger, Waverly.

Mr. William Briggs, Fields.

Mr. Owen Brown, Thornville.

Mr. R. L. Condon, Omega.

Mr. J. C. Corwin, Waverly.

Mr. Austin Cooprighter, Glenford.

Messrs. Davis Bros., Diamond.

Mr. Flory, Newport.

Mr. J. V. Farver, Millersport.

Mr. Finley, North Liberty.

Mr. Feurt, Portsmouth.

Major Foster, Higsby.

Mr. A. C. Francisco, Akron.

Mr. Gamble, Walhonding.

Miss Hunter, Brink Haven.

Mr. E. Hyde, Lancaster.

Mr. Higby, Higby's.

Messrs. Harness, Richmondale.

Mr. H. Hope, Paint.

Mr. W. C. Hampton, Mt. Victory.

Mr. R. E. Hills, Delaware.

Mr. J. H. Johnson, South Portsmouth, Ky.

Mr. Johnson, Coshocton.

Mr. E. H. Moore, Athens.

Mr. G. F. Manning, Coshocton.

Mr. Wm. McCormack, Youngsville.

Dr. A. J. Marks, Toledo.

Mr. Monteath, Concord, Ky.

168

Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

Mr. J. Maxwell, Coshocton.

Mrs. Jane McCullough, Youngsville.

Mr. John Montgomery, Youngsville.

Miss McCullough, Newport.

Mr. C. C. Naylor, Manchester.

Mr. J. R. Nissley, Ada.

Mr. Owens, Concord, Ky.

Mr. Plummer, Newport.

Mr. Patton, Youngsville.

Mr. E. S. Perkins, Weymouth.

Mr. Joseph Porteus, Coshocton.

Mr. Porteus, Sr., Coshocton.

The Quick Heirs, Loudonville.

Mr. J. M. Richardson, Wilmington.

Mr. L. Simonton, Lebanon.

Mr. J. Stout, Rome.

Mr. E. Schlupp, Lovell.

Mr. C. C. Stamin, Mifflin.

Mr. Sherwood, Malta.

Mr. Swarington, Newport.

Mr. L. D. Sprague, McConnelsville.

Mr. Tomlinson, Newport.

Mr. Tom Tipton, Williamsport.

Mr. J. W. Tweed, Ripley.

Mr. F. E. Williams, Wauseon.

Mr. Barton Walters, Circleville.

Mr. J. Williams, Youngsville.

Mr. George Workman, Walhonding.

Mr. Wilhelm, Duncan's Falls.

Mr. Frank Yost, Thornville.

Mr. Irvin Yost, Thornville.

Several gentlemen were especially

courteous in obtaining

permissions for exploration, in

introducing us, in procuring col-

lections and in showing us remains which

might have escaped

our notice. I acknowledge my obligations

to them:-Mr. H. B.

Case, Loudonville; Messrs. Pomerine,

Coshocton; Mr. R. Mc-

Cullough, Youngsville; Mr. Arrick,

McConnelsville; Dr. W. H.

Report of Field Work. 169

Robe, Youngsville; Mr. Charles Wertz,

Portsmouth; Mr. Higby,

Higby's Station; Messrs. Harness,

Richmondale; Mr. W. H.

Davis, Lowell.

WARREN KING MOOREHEAD.

Columbus, O., Dec. 1st, 1896.

FIELD WORK DURING THE SPRING AND SUMMER

OF 1896.

SECTION 1. PERRY COUNTY.

Perry County is pretty well divided as

to drainage between

the Muskingum and the Hocking. The

northern portion of the

County is drained by Jonathan Creek, a

tributary of the former.

As our observations were to be confined

to the Muskingum and

its branches we did no work in the

southern part of the County.

We found that Hopewell and Thorne

Townships alone con-

tained more than forty ancient remains

and that at least Jon-

athan Creek Valley, if not all of Perry

County, is but a contin-

uation of the great works known as the

Newark Group.* But

none of the mounds and enclosures can

compare in size with

them, and of the entire county but three

structures can be placed

in what may be termed "the first

class," and they are the Reser-

voir stone mound, the stone fort and the

earth enclosure near

Glenford.

THE STONE MOUND OF THE LICKING COUNTY

RESERVOIR

is located upon a high hill ten miles from Flint Ridge, two miles

from the town of Thornville, Perry

County, and seven miles

from the stone fortification at

Glenford. It is just over the Lick-

ing County line, north from Thornville,

and overlooks the valley

now filled by the Licking County

Reservoir and formerly occu-

pied by an ancient lake.

* See Squier & Davis' "Ancient

Monuments of the Mississippi

Valley", plate XXV; also

"Notes on Ohio Archaeology", by Gerard

Fowke, plate V.

|

170 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

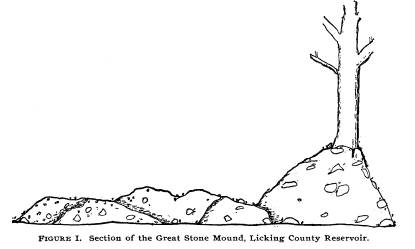

It is one of the greatest mounds in the State, but has never been generally known because at the time of the construction of the Reservoir, most of the sandstone blocks and fragments of which it is composed, were hauled away by the contractors and utilized in the formation of the Reservoir walls. At the present day it is upon the farm of Mr. Owen Brown. Early in April, 1896, the structure was of the following dimensions: 189 feet northeast and southwest; 207 feet north- west and southeast; average height 81/2 feet; maximum height 12 feet; minimum height 5 feet. From traditions and publica- tions of early archaeologists and from the curve preserved by a large tree on the north side, it must have been about 55 feet in height when completed. This tree, some five or five and a half feet in diameter, has an extensive spread of roots and holds in place a bulk of material 15 by 25 feet. (Figure 1). |

|

|

|

Large stones, 20 to 40 pounds, originally composed the bulk of the mound, but these have been nearly all removed, and only the smaller ones, sand, earth and decayed vegetable matter re- main. Work was begun early the morning of the 24th of March and continued for five days with an average force of nine men. Excavations proved that the mound rested upon original sur- face yellow clay (see museum specimens in tray 6285), that the |

|

Report of Field Work. 171

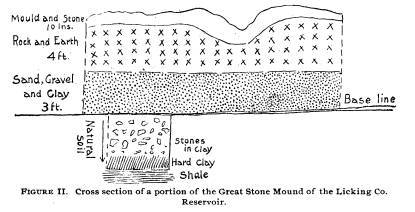

ground had been cleared and burned over; the sod line or base was one inch thick and interspersed with flint chips, burnt clay and a little charcoal and gravel. Figure II will show the struct- |

|

|

|

ure from natural clay down to shale and from the base line of the mound to the top. At this point the mound was nine feet high. Generally above the base line was three feet of clay in which a few stones occurred. The clay showed the "dumps" plainly. In some places instead of clay, sand was found, and our section exhibits such a part of the mound. As near as could be determined, an undisturbed section of the mound 40 x 20 feet was selected and an excavation sunk to the original base line. In other parts of the mound eight or ten large holes were put down, but it seems that nearly the whole of the original area covered had been disturbed by those vandals who hauled away stone, not by the hundreds but by the thous- ands of wagon loads for the Reservoir walls. Thus, in the in- terest of modern progress, was destroyed one of the most im- portant and imposing, if not unique, tumuli in the entire Ohio valley. This may seem at first sight to be an exaggeration, but let us call your attention to the facts. We have, it is true, stone fortifications, enclosures and mounds. But these are never more than 12 or 15 feet high,-while the average is less than 6 feet. Hence a stone monument 30 feet high would be both unusual |

172 Ohio Arch. and His.

Society Publications.

and unique-a freak, as it were. Imagine

the importance in pre-

Columbian times, of a stone mound 50 or

55 feet in altitude.

What important personages must have been

interred in it! One

old man, who visited the mound, said

that as a boy he had seen

several skeletons, covered with copper

rings and plates, sur-

rounded by chestnut logs. He thought

these were found near

the north side. Our excavations in sites

which we took to be

undisturbed, yielded no returns. Too

thoroughly had the ignor-

ant teamsters done their work of

demolition.

One can conceive the magnitude of the

task undertaken by

the builders when it is remembered that

the most conservative

estimate places the number of wagon loads

of stone hauled from

this mound at 5,000.

The large mound was originally

surrounded by a low em-

bankment of earth which has disappeared.

South of the mound

is a small one 250 feet distant. It was

40 feet east and west, 28

feet north and south, and three feet

high. It is composed of

yellow clay and on the top were some

large stones weighing from

40 to 60 pounds, about one hundred of

them. We cannot as-

sign a reason for its construction. We

dug 20 x 25 feet, taking

out all of the original mound. In the

mound were found some

burnt stone and one arrow-head.

We can find but one satisfactory

reference to the explora-

tion of this structure, and that is in

Rev. J. P. McLean's "The

Mound Builders:"* "Perhaps the

largest and finest stone mound

in Ohio was that which stood about eight

miles south of Newark,

and one mile east of the Reservoir on

the Licking summit of

the Ohio Canal. It was composed of

stones found on the ad-

jacent grounds, laid up without cement,

to the height of about

50 feet, with a circular base of 182

feet diameter. It was sur-

rounded by a low embankment of oval

form, accompanied by a

ditch, and having a gateway to the east

end. When the Reser-

voir, which is seven miles long, was

made, in order to protect

the east bank so that it might be used

for navigation the stones

from this mound were removed for that

purpose. During the

years 1831-32 not less than fifty teams

were employed in haul-

ing them, carrying away from 10,000 to 15,000 wagon loads.

* Cincinnati, 1885, page 42.

Report of Field Work. 173

Near the circumference of the base of

the mound were discov-

ered fifteen or sixteen small earth

mounds and a similar one in

the center. These small mounds were not

examined until 1850

when two of them were opened by some of

the neighboring farm-

ers. In one were found human bones with

some fluviatile shells,

and in the other, two feet below a layer

of hard white fire clay, they

came upon a trough covered by small

logs, and in it was found

a human skeleton, around which appeared

the impression of

coarse cloth. With the skeleton were

found fifteen copper rings

and a breastplate or badge. The wood of

the trough was in a

good state of preservation, the clay

over it being impervious

to both air and water. The central mound

was afterwards

opened and found to contain a great many

human bones but

no other relics of any note."

In the possession of a farmer we saw an

X-shaped copper

ornament which he claimed came from the

mound. It will be

remembered that the so-called "Holy

Stone of Newark" was

found in this structure encased in a

stone box. While any arch-

aeologist would admit the genuineness of

the copper cross and

bracelets, they have proven that the

"Holy Stone of Newark"

is a "fake" pure and simple.

Mr. Warrick is the only surviving

workman who assisted in the excavating

at the time of the

discovery. He knows nothing personally

of the "Holy Stone,"

but did see the other relics. In this

connection it might be well

to quote the expose as published in

"Primitive Man in Ohio.:"*

"Some writers have misrepresented

and distorted field tes-

timony to uphold theories previously

formed. As an illustra-

tion of this, and of the great damage

that it has done, we need

but call the attention of our readers to

the famous 'Holy Stone of

Newark.'

"An enthusiastic archaeologist

resided many years ago at

Newark, O. He was thoroughly in love

with his work, and his

life's ambition was to discover the

origin of man upon the Amer-

ican continent. He believed the lost ten

tribes of Israel to be

the ancestors of the mound-building

tribes. After opening

mound after mound and finding no

evidence whatever in sup-

port of his hypothesis, he became desperate.

He purchased a

* G. P. Putnam's Sons, New York, 1892,

page IV, preface.

174

Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

Hebrew Bible and primer and shortly

afterwards there was dis-

covered in a stone box, in a mound that

he had investigated,

a slab, on one side of which was a

likeness of Moses, and on the

reverse an abridged form of the ten

commandments. The stone

attracted world-wide attention, and many

publications were is-

sued describing it. No one doubted the

genuineness of the

affair until after the man's death. In

cleaning up his office the

administrator found in a small rear room

bits of slate with at-

tempts at carving Hebrew characters upon

them. They also

found a fair copy of the wood-cut of

Moses used as a frontis-

piece in the testament.

"The influence of this over-zealous

deceiver has gone

throughout the length and breadth of our

land, and one may

still hear at lectures upon American

archaeology statements con-

cerning the Indian's descent from the

Jew, basing such asser-

tions upon the testimony of the supposed

'Holy Stone of New-

ark,' which, as is above shown, was

simply a counterfeit."

We could not detect a trace of the small

earth mounds men-

tioned by Rev. MacLean. Man has

destroyed them all. Con-

sidering the size and character of the

mound, one would nat-

urally suppose that it would have

contained much of value and

importance. Viewed in this light our

work was a disappoint-

ment.

FRANK YOST'S MOUNDS.

A large irregular fortification and

three mounds occur upon

the farm of Mr. Frank Yost, three and a

half miles south of

Thornville, on a hill some 100 feet in

height. Clay is used in

their composition. The group is distant

about two miles from

the great stone fort on the hill south

of Glenford. South of the

fortification and almost adjoining it,

is a circle enclosing a bird

with wings outspread. The circle, as

near as we could judge

without the use of surveying instruments

and employing a hun-

dred-foot tape, was 652 feet around, 31

feet wide and 4 feet high.

Its gateway faces to the north and was

23 feet wide. The bird

effigy (body, head to tail), is 48 feet

north and south. The east

wing is 122 feet from edge of body to

tip; west wing 111 feet

from edge of body to tip. The body is 20

feet wide. The total

Report of Field Work. 175

length from tip to tip is 253 feet.

Measurements of the wings

20 feet from the ends are, east wing 31

feet, west wing

30 feet. A ditch existed between

the bird and the cir-

cle. It has filled considerably and is

now 18 inches deep. Its

original depth was about four feet. The

original distance from

the bottom of the ditch to the top of

the circle was 9 feet. The

head of the bird was 28 feet from the

center of the circle bank.

A small mound 100 feet northwest of the

circle was opened

and in it was found much burnt earth,

charcoal and calcined

stones, but no specimens. The mound is

40 feet in diameter

and 4 feet high. There was a large

deposit of burnt clay in the

bottom. We excavated in the bird effigy,

finding ashes.

Mr. Austin Cooprighter owns an adjoining

farm to Mr. Yost,

and upon his land runs the same

embankment for some four or

five hundred feet. On the first terrace

on Jonathan Creek, dis-

tant 300 yards from the fortification

above, are two elongated

mounds, one headed north and south and

the other east and

west. Large holes were sunk in Mr.

Cooprighter's mounds and

in the largest one were ashes, mica and

burnt clay in quan-

tities. Neither relics nor bones were

found. Some time was

spent in surface hunting over

neighboring village sites with pro-

fitable results.*

IRVIN YOST'S MOUND.

On a high hill three and a half miles

south of Thornville,

is a mound 51x56x41/2 feet. With the

exception of a few large

stones near the center, the mound was

composed entirely of

clay. We began on the south side with a

trench 36 feet wide

and carried it entirely through, finding

charcoal, burnt earth,

pottery fragments, flint implements, a

circular disc and a hema-

tite celt. Some decayed bones, all that

remained of a skel-

ton, were found. A village site extended

to the northwest of

the mound.

Mr. Atwater in his volume,

"Archaeologia Americana," de-

scribes the great stone work in Perry

County, five miles north-

* Dr .Cyrus Thomas in a Smithsonian

Institution Bulletin (Washing-

ton, 1891), entitled "A Catalogue

of Prehistoric Works", reports some

eight remains in Perry county.

176

Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

west of Somerset, or one mile from

Glenford.* His descrip-

tion is valuable in that it gives us

some conception of the height

of the walls and of the mound they

surrounded. He says it

resembled a sugar loaf and was 12 to 15

feet high at the time

of his visit. We can judge of the

enormous amount of stone

taken away by neighboring farmers and

contractors, for the

mound is to-day but a pitiful heap of

stones and the wall in places

has about disappeared.

Not only because of their geographic

position but also on

account of similarity in construction

and contents, do the

mounds of Perry County belong to the

Muskingum tribe. Art,

as found in them, does not evince a high

degree of culture, but

it is very ancient and therefore of

paramount importance. Per-

haps one makes no mistake in venturing

the suggestion that the

people in this region had no commerce

with other tribes. Cer-

tainly there is not sufficient mica,

copper and other foreign sub-

stances to prove that trade relations

existed.

Never have we witnessed so many chips

and discs of Flint

Ridge material (except at the Ridge

itself) as occur upon the

Perry County sites. Nearly every knoll

was a workshop. Boys

and farmers find thousands of arrows,

spears, knives and scrapers

of this material and yet the supply does

not seem to be exhausted.

Little other material occurs.

Flint Ridge stone being found in every

county of Ohio set-

tles as a fact the proposition that

while we may consider one

section of the State older than another,

yet the quarries at the

Ridge were worked through a long period

of time. It is cer-

tain that the earliest men in Ohio

resided within the State but

a short time before they discovered and

utilized Flint Ridge ma-

terial. In this connection it would be

interesting to ascertain

if the quarries upon the Walhonding

River are older. It is just

possible that both localities may have

been developed at the

same period.

SECTION 2. THE MUSKINGUM VALLEY PROPER.

On May 6th Mr. Walter O'Kane and myself

left for Mans-

field with the intention of following

the Muskingum from its

* American Antiquarian Society,

Worcester, Mass., 1820, page 132.

Report of Field Work. 177

source to the Ohio River. Our mission

was two-fold-to locate

upon our State archaeological map all

the ancient remains in the

region and to explore burial places and

collect specimens. The

Muskingum as a whole has never been

investigated by any insti-

tution and there was, consequently,

almost nothing known re-

garding its pre-Columbian occupation

except at three localities-

Newark, Loudonville and Marietta.

Proceeding east from Mansfield we struck

the head waters

of Black Fork at a point where the

stream was some twenty feet

in width. We followed this down through

Mifflin and Perryville,

Ashland County, also through the edges

of Holmes and Knox.

As we drew near to Coshocton the valleys

deepened and other

tributary streams swelled the stream

until it became the Mohican

River and presently the Walhonding. We

found many gravel

burials, especially between Loudonville

and Warsaw, but they

were most numerous around Warsaw,

Mohawk, Mifflin and

Zanesville. We do not consider that the

gravel knoll burials

were made by the same tribe which

erected the tumuli, but by an

earlier and more primitive one.

MIFFLIN, ASHLAND COUNTY, BLACK CREEK

VALLEY.

On Mr. C. C. Stamin's farm are several

gravel knolls or

glacial kames. In two of these decayed

skeletons have been

found three to five feet from the

surface. About fifteen were

found when grading for a bank barn was

in progress. A few

flint implements were with the bones. In

searching the fields

we found a hematite celt and a flint

knife. Figure III shows Mr.

Stamin's kame and barn on the site of

the skeleton finds.

We dug several holes about the lame

(shown in photograph,

16,201 museum number), but found no

skeletons, all having been

removed. In a large gravel hill at the

edge of Mifflin we also

dug without results. There are few

mounds this far up the

stream.

Reaching Perrysville we met Professor

Sample, who has a

large collection. He located mounds and

village sites on our

map. En route to Perrysville we stopped

at the Copus monu-

ment, where whites were killed by

Indians in 1812, and photo-

graphed it. It is an historic spot. We

met and conversed with

|

178 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

the grandson of the pioneer. At this point, as throughout the valley, we purchased specimens of farmers. |

|

|

|

From Perrysville Mr. O'Kane inspected the Delaware village site three miles up the stream, known as "Black Fork of the Mohican." He looked for graves and lodge sites, but was unable to find them, though he dug several deep holes. He also saw two mounds. Both had been examined.

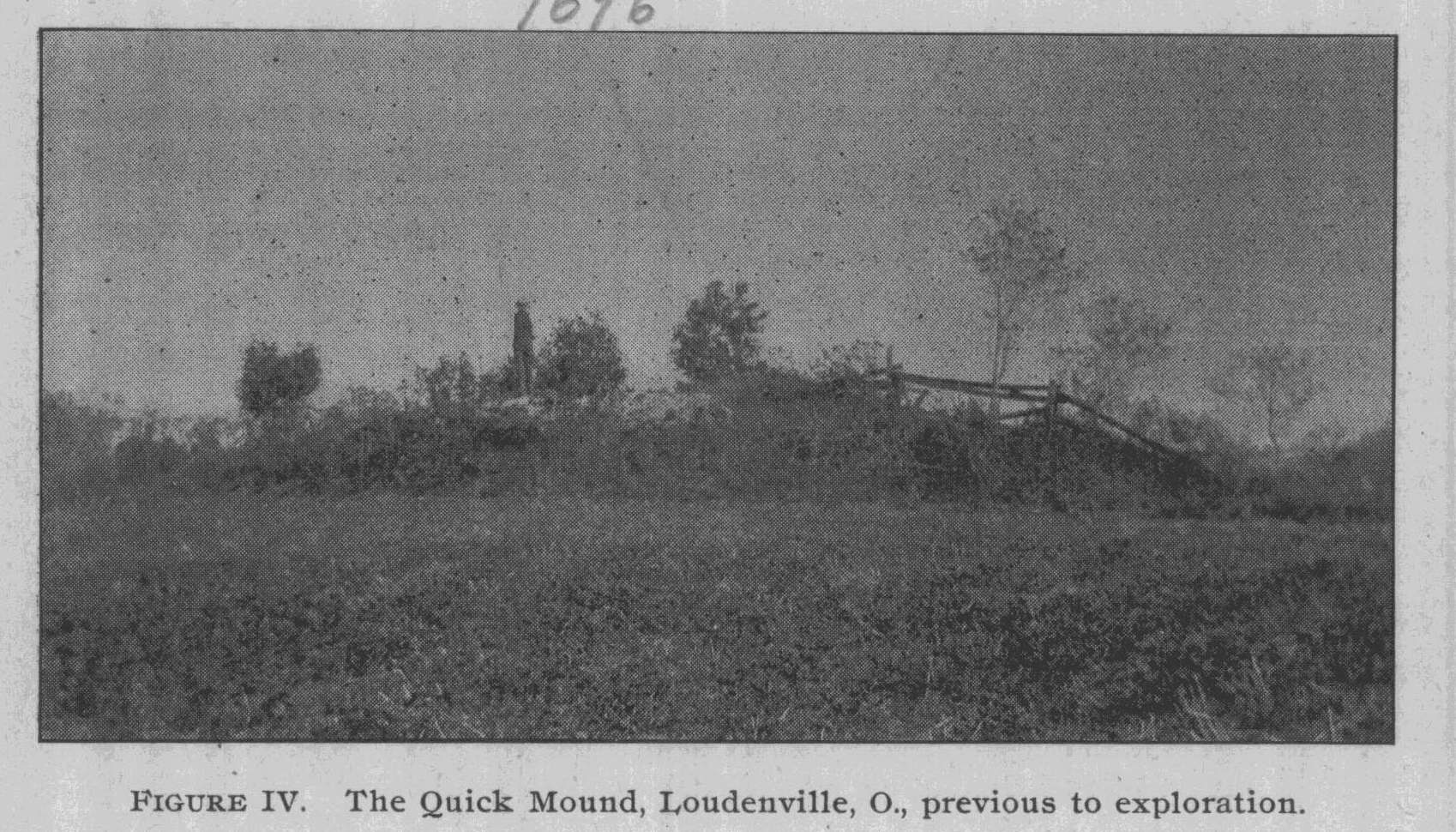

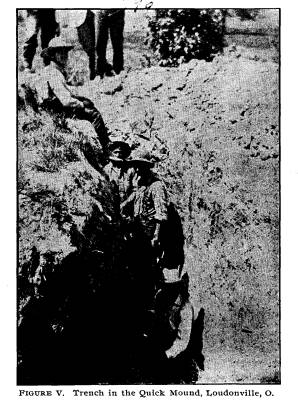

LOUDONVILLE, ASHLAND COUNTY. We began work the morning of the 8th on the Quick farm. There are two mounds, one about obliterated and the other stand- ing 9x72x68 feet. The former is in low ground and the latter on a hill of 200 feet elevation. They are in the edge of Holmes County, just a little over the line in Washington Township. The nearly obliterated one was about ten inches high and was speedily excavated. Nothing in it. The large one is composed of dark red clay and is shown in Figure IV. It had been partly dug some sixty years ago. In it were found two skeletons, a boulder layer and a slate |

|

Report of Field Work. 179

ornament. There were slight evidences of camp sites in the ad- joining fields, but more in the valley below, along the stream. We sunk a trench eight and one-half feet wide and nine feet deep and continued the same around the mound, widening it at the bottom. We found the mound had been built over a slight depression and therefore while but seven feet high on the north side, was nine feet on the east and south sides. It was erected upon a burnt floor or base. Above this was a dark streak one-half inch wide; then a layer of ashes and pottery fragments and burnt bones one-half inch thick. A hard burnt |

|

|

|

"pan" or floor, one inch thick and cement-like in character was above this. It seems to have extended over a space 12x15 feet. From the summit down to within one foot of the base line the structure exhibited no stratification. There was a heavy deposit of white earth eight inches thick above the hard floor. We extended our trench forty feet in total length around the old or central excavation, examining all the earth as far as there were indications of burials, ashes, pottery, etc. We found, some sixteen feet southeast of the center, a skele- ton on the base line. It was much broken and decayed. How- ever, a large piece of skull and some of the leg bones were secured. Thirty-five or forty beads lay about the neck. All the earth around |

180 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

the skeleton was carefully examined with

trowels, also sifted

through our hands in search of more

beads, but the string had

been a small one.

The legs of the individual were crossed

at the knees. Under

them were some small pebbles of

irregular shape.

Animal bones, chiefly deer, were in the

ashes below the hard

floor. Some fifty of these were found

and about 400 pottery frag-

ments.

Upon completion of the work we filled

the trench to within

a few inches of the top. Figure V shows

a section of our trench

and its curvature.

We inquired of local collectors as to

other mounds, but ascer-

tained that all of them had been

excavated.

Mr. H. B. Case, of Loudonville, was with

our party during

the work in Ashland County. In the

Smithsonian Institution

report for 1881, pages 592 to 601, he

describes the antiquities of

his county. All the remains he mentions,

together with some

thirty others which we discovered, have

been transferred to our

State archaeologic map. As Mr. Case is

an authority we will

present his report in full.

"A square inclosure with a gateway

to the southwest is situ-

ated in section 36, Clear Creek

Township, on the line between

the northwest and southwest quarters of

the section, upon land

owned by John and Thomas Bryte. It is

about 400 feet long

by 200 feet wide, and has a gateway at

the southwest corner near

a very strong spring. In 1824 Mr. Bryte

commenced to clear

his farm. The embankment at that time

was from three to four

feet high and ten feet wide at the base.

Both the embankment

and the area were covered with large oak

trees. The place now

goes by the name of Bryte's Fort.

"Two mounds stand upon a high

natural elevation (90 feet),

covering about five acres at the base, and

being about 60 by

90 feet on the top, which is nearly

flat. Each is twenty-five feet

in diameter and four or five feet high.

They are situated on the

northeast quarter section 35, Clear

Creek Township. At least

one of them was explored as early as

1844, by Thomas Sprott and

brother, who found a number of human

skeletons in a kind of

|

Report of Field Work. 181

stone cist, upon which was almost a peck of red Indian paint. The bones were replaced. "A circular inclosure containing two acres, more or less, is situated just north of the Atlantic and Great Western Railway |

|

|

|

and within the city limits of Ashland. The farm was formerly owned by Henry Gamble. In 1812-'15 the first settlers found embankments from three to four feet high and from eight to ten feet wide at the base. A forest of oak, hickory, sugar and ash grew upon and near this work. It overlooked the valley to the south and east, and had a gateway at the southwest opening near a fine spring. The site has been plowed for more than fifty years; and scarcely a trace of it remained in 1878. |

182

Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

"There is a circular inclosure

located near the north line of

the northeast quarter section 9, Mohican

Township, one mile east

of Jeromeville.

"On the farm of Nicholas Glenn is a

mound and an earth-

work. Information might be obtained from

John Glenn, Jr., or

from William Gondy, an old settler, both

of whom live at Jerome-

ville, Ohio. The works are about two

miles southwest of Jerome-

ville.

"The Mohican town called Johnstown

was located here. In

the years 1808-'10 it contained

Delawares, Mohegans, Mohawks,

Mingos, and a few Senecas and Wyandots.

Captain Pipe, a

Wolf Indian, ruled the village until he

left it in 1812.

"A large circular inclosure and

burial mound are situated

in Wayne County, just south of the road

leading from Lake

Fork to Blatchleysville and just east of

the road leading from

McZena to Blatchleysville. These remains

are upon a high,

gradual elevation overlooking a vast

range of prairie, northeast

and southeast, as well as the valleys

westward. The circle is

a little less than one-third of a mile

in circumference. At present

the embankments are from one to two feet

in height. The area

and embankment are covered by the forest

growth, which is not

older than sixty or seventy years, the

Indians having burned this

region annually until about 1812, for

the purpose of hunting.

Years ago the mound was opened by

unknown persons. In 1876

the author visited it, and found that an

animal had burrowed into

it and brought out a fragment of skull,

which is now in his

possession. Some time after, Mr. Thomas

Bushnell, of Hayes-

ville, made excavations in the mound and

found only bones,

among which was a well-preserved skull.

The mound is twenty-

five or thirty feet in diameter and four

feet in height.

"A small mound, three or four feet

high and fifteen feet in

diameter, stands upon a very high hill,

perhaps the highest land in

the county, and is composed of stone and

clay. It was excavated

some years ago by Dr. Emerick and a Mr.

Long, who are said

to have found a skeleton in a kneeling

or sitting posture, and a

pipe, both near the center. The author

was unable to learn what

had become of the pipe. Messrs. H. B.

Case and J. Freshwater

made another examination in 1876, but

found nothing. There is a

Report of Field Work. 183

large spring at the foot of the hill, on

the east side, but it is nearly

half a mile from the spring to the mound

on the hill.

"In 1876 the author, in company

with Mr. J. Freshwater,

made a slight examination of this mound.

It is twenty or thirty

feet high, oval in shape, and over 100

feet long. The citizens

regard it as an artificial mound, but we

considered it a natural

elevation of gravel drift. Excavations

might change this view.

The mound is located on the west side of

the Lake Fork, and just

north of the road and bridge leading

from Mohican to McZena

in Lake Township.

"A mound is situated on the lands

of J. L. and Cyrus Quick

in Washington Township, Holmes County,

Ohio. It stands

upon an eminence which slopes gradually

for half a mile south-

ward toward the bottom lands of the Lake

Fork; northward and

westward it declines a short distance to

a small valley extending

to the southwest. It is about five or

six feet high, and thirty feet

in diameter. Some trees were growing

upon the mound when

the author first visited it, some

twenty-seven years ago. The

trees were perhaps not of more than one

hundred years growth,

but were as old as the trees in the

immediate vicinity; not far

from it, however, were oak trees two and

three feet in diameter,

The mound was excavated about 1820-'25

by Isaac and Thomas

Quick, Daniel Priest, and others. It is

said that, upon making

a central excavation, they found a

wooden puncheon cist, to-

gether with some human remains, and

ornaments of muscle shell,

which appeared to be strung around the

neck. All the remains

are reported to have crumbled away on

being exposed to the air.

It is difficult to ascertain the facts

concerning this excavation. It

has been said that some pottery was

found also. Additional re-

mains might be disclosed by further

investigation. The persons

who made the excavation are dead.

"A lake is situated a short

distance from the mound, on the

farm of D. Keck, Washington Township,

Holmes County, Ohio,

In draining this pond a cache of flint

implements was discovered.

Specimens of these implements may be

seen in the Smithsonian

collection. The remainder are in the

author's possession. (See

Smithsonian report of 1877, article by

H. B. Case.)

"There are mounds southeast of

Odel's Lake, upon the sum-

184

Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

mit overlooking the lake, on the farm of

J. Cannon. They were

excavated by Dr. Boden, of Big Prairie,

Ohio, who has in his

possession some teeth, jaw bones, and

long bones taken from

them. He says that they should be

further examined. The

author has not visited the mounds.

"A mound stands on the summit of

Dow's Lake, one mile

northeast of Loudonville, just east of

the Holmes County line.

It was excavated about 1855 by Dr.

Myers, of Fort Wayne, and

D. Rust, who found a skeleton near the

center, whose structure

is of stone and earth. The top has since

been leveled by the

plow. In 1876, Mr. Lucien Rust made some

excavations upon

the site of the mound, and great numbers

of stone were re-

moved. At length a kind of pot or cist

was unearthed, which

was about 18 inches in diameter and 8 or

9 inches deep. It was

formed of stone, and the edge was

covered by other stones which

made a roof over the pot. The removal of

this roof or top

showed that the cist was filled with

charcoal, apparently closed

while glowing coals. About 4 feet below

this charcoal deposit

human remains were found, reposing

horizontally. Near the

left hand was a perforated stone having

the figure of a bird, re-

sembling slightly the pheasant,

scratched upon it. A part of a

bone implement was also found. The bone,

which is of firmer

texture than the human bones, and is

perhaps a part of the leg-

bone of a deer, had been perforated,

evidently with a stone drill.

Lying across this lower skeleton and

some distance above it were

the remains of another. But little of

the mound has been excava-

ted and further examination should be

made. From the mound

the view of the surrounding country is

very fine. The mound

proper has been obliterated for some

years, but the site can be

observed by a slight elevation and the

great number of stones

scattered about and upon it. There must

have been a kind of

hollow made in the Waverly shale which

lies near the surface

upon the underlying Waverly sandstone,

of which the hill is

composed, because when one digs the same

depth elsewhere on

the hill the shaly sandstone is

penetrated. The stone implement

is in the possession of L. Rust,

Loudonville; the bones, bone

implement, and charcoal are in the

author's cabinet.

"A mound is situated just north of

Loudonville, on the sum-

Report of Field Work. 185

mit of Bald Knob. For a long time it was

supposed by the

citizens of Loudonville to have been

formed by counterfeiters

in former times. The author excavated it

in 1877, and found

it a veritable mound containing

fragments of human bones and

of charcoal. Being encased with large

sandstones, and com-

posed of stone and earth, it is very

difficult to excavate. As

there has been a central depression for

a great many years, what

remains the mound contained of a

perishable character have

probably been destroyed by the

collecting of water. This site

also commands a fine view of the Black

Fork valley.

"The settlers of 1808-'09-'10 found

here a village of Dela-

wares, the remnant of a "Turtle"

tribe. Their chief was a white

man, taken in infancy-Capt. Silas

Armstrong. They removed

to Piqua, Miami County, Ohio, in 1812,

the site of the old bury-

ing-ground, now almost entirely

obliterated by cultivation. It

is located a few rods north of the Black

Fork, upon a gentle emi-

nence, in the southwest part of

northeast quarter section 18,

Green Township. The southern portion of

the site is still in

woods, and the depressions that mark the

graves are quite dis-

tinct. Henry Harkell and the author

exhumed several of the

skeletons in the summer of 1876. In some

cases the remains

were inclosed in a stone cist; in

others, small rounded drift-bowl-

ders were placed in order around the

skeletons. The long bones

were mostly well preserved. No perfect

skull was obtained, nor

were there any stone implements found in

the graves. At the

foot of one a clam shell was found. The

graves are from 21/2 to 3

feet deep, and the remains repose

horizontally. A few relics,

such as stone axes, arrow-heads and a

few bits of copper, have

been picked up in the immediate

vicinity. They are in the hands

of the author. On the opposite side of

the stream and some

distance below, near the south line of

southeast quarter-section

18, Green Township, there are ancient

fireplaces. They are about

15 inches below the present surface, and

are formed of bowlders,

regularly laid. The earth is burned red. Great numbers of

stones have fallen into the stream

during its incursions upon the

west bank. Some three or four of these

fireplaces are yet plainly

visible, but in a few years they will be

swept away by the cur-

rent. About half a mile east of the

graves is a small circular

186

Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

earthwork almost razed. It contained

about 1½ acres, and

had a gateway looking to the river,

which is westward. It

is situated upon the nearly level bottom

land of the beautiful

valley.

"Upon the high ridge separating the

valleys of Black Fork

and Honey Creek is a depression filled

with large and small

bowlders. J. Freshwater and the author

removed them to some

depth, but as the stones were heavy we

desisted from further in-

vestigation. This point would command a

view of the valley

of the Black Fork, overlooking, as it

does, the old village of

Greentown; and by walking a few rods

eastward on the same

eminence a view of the valley of Honey

Creek might be had.

Most of the trees on this height are

less than 100 years old. It

may have been timberless during the

occupation of this work.

The excavation appears to have been

about 15 feet in diameter.

"There is a stone mound, situated

on a lofty eminence

overlooking the Black Fork valley

northwestward, and east-

ward the valley near Loudonville. The

author has never

seen the work, but it has been described

to him as a small stone

and earth mound such as are usually

found on high points.

"A short distance northwest, on the

farm of L. Oswald,

southwest quarter-section 18, in the

woods, is a mound about

30 feet in diameter and from 4 to 6 feet

high. It was slightly

opened at the center by the owner of the

lands, who found part

of a skull.

"A mound and earthwork are located

upon the old Parr

farm, now owned by C. Byers, in the

northwest part of south-

west quarter-section 19, Green Township.

The mound stands

on the west side of the Black Fork,

within 2 or 3 rods of the

stream. It was quite large originally,

perhaps 8 or 10 feet high

and 35 to 50 feet in diameter. At

present it is from 4 to 6 feet

above the level of the bottom land and

is spread over a consid-

erable space. When the first settlers

came, there was an earth-

work running a little southwest from the

mound for some 20

rods, then back eastward to the river.

The place has been un-

der cultivation for forty or fifty years

and the work is now ob-

literated. The mound was encased with a

wall of sandstone

bowlders as large as a man can lift.

Report of Field Work. 187

"These stones must have been

carried from the hill half

a mile west where they are found in

place. The wall was care-

fully laid, as can be seen by

excavations below the depth of the

plow where the pile is still intact. The

mound was examined

in 1816 by some persons named Slater,

who found in it bones,

flint implements, a pipe, and a copper

wedge which they thought

gold. Accordingly they took it to a

silversmith at Wooster,

Ohio, who told them that it was copper,

and bought it from them

for a trifle. In 1878 the mound was

explored by J. Freshwater

and the author. The center of the mound,

where not disturbed

by former excavations, resembles an

altar or fire-place where

the fire had burned the earth to a

brick-red. In the ashes and

burnt earth were fragments of

arrow-heads broken by the heat.

The fire had been kindled on the mound

when it was from 2½

to 3 feet high. No human remains were

discovered in this last

excavation. A few scrapers were found,

which are in the cab-

inets of the above named gentlemen.

"On the summit of a hill west of

Perrysville, and to the right

of the road leading to Newville, was a

mound, now entirely

obliterated. In 1816-'20 it was opened

by the Slaters, who found

a pipe, human remains, and some other

relics.

"A large oval earthwork is on the

summit of the ridge be-

tween the valleys of Black Fork and

Clear Fork. It is 210 feet

wide by 350 feet long. About the center

of the inclosure was

a large pile of stone bowlders, most of

which have been removed

to the level of the ground. There is,

however, a visible outline

of the stonework, which consisted of a

paved circular space.

No excavation has been made in either

the stone or clay work

beyond 1 or 2 feet in depth;

consequently the character of the

mound is unknown. A forest, containing

oak trees over 30

inches in diameter and other large

trees, covers most of the work,

but a portion extends into a field and

has been almost razed

by the plow.

"On a high hill directly north of

the junction of the Black

Fork and the Clear Fork, and overlooking

the same, is a stone

and earth mound composed principally of

large sandstones from

the immediate vicinity. Some twenty or

twenty-five years ago

it was explored by unknown persons. The

author examined it

188 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

again in 1877, but discovered nothing. A

similar mound is said

to have been located upon the hill south

of the Clear Fork, just

below the junction of Pine Run. The

stone were hauled away

and the site plowed over.

"The old Delaware village of Hell

Town is on the Clear

Creek in Richland County, near Newville.

It is on the south

side of the stream about 4 miles from

the Ashland County line.

It was deserted about 1782, the time of

the massacre of Gnaden-

hutten. Graves were visible until two

years ago; the field is

now cleared and plowed. In the author's

cabinet are two iron

scalping-knives and an iron tomahawk

which were thrown up

by the plow; also the brass mountings of

a gun, a gun-flint, a

stone ax, and some arrow-heads. Dr.

James Henderson of New-

ville, Ohio, has in his possession

several articles obtained from

this site. The Indians formerly called

their settlement Clear

Town, and the stream Clear Fork, but

learning the German

word hell, for clear or bright, they

changed the name to Hell

Town.

"A rock shelter is located on the

west side of Clear Fork,

in the conglomerate sandstone of the

Lower Carboniferous. It

was explored in 1877 by L. Rust and the

author, who found

about 2 feet of ashes intermingled with

a few animal bones and

coprolites. No human remains were

disclosed excepting a split

bone, and even that is doubtful. The

ashes continue deeper, and

further examination might prove

interesting."

At Brink Haven the stream (Mohican

River) is large and

can be navigated in a canoe. There are

many stone mounds

on both sides, upon the high hills.

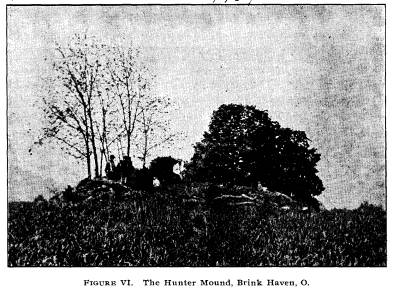

On the Hunter farm one mile below the

village, is a small

mound 3 feet high and 35 feet base, made

of yellow clay. It

is shown in Figure VI. Although

thoroughly examined, there

was nothing found in it.

Mr. Gann lives opposite the Hunters,

across the Mohican.

On his farm are two mounds 300 yards

apart. One is 4 feel

high and 35 feet base. Both are injured

by cultivation. In

the larger one we found some charcoal.

Four large white flint

arrow-heads lay about a foot from the

surface near the center.

Nothing else was found.

|

Report of Field Work. 189

The small mound contained charcoal and burnt earth. There were no bones or relics. Both mounds were examined thoroughly. |

|

|

|

We reached Walhonding late in the evening of the 12th. We saw a cache of rough flint implements in the possession of Mr. George Workman. He found them in a pit 3 feet deep when clearing a woods. They occupied a space 2x11/2 feet, and num- bered more than 400. People have carried off about half of the cache. The others yet lie in his yard. We went six miles up Green valley to Mr. Staats', where a large mound 7x65 feet was reported. It had been excavated, some one having run two large cross trenches through it. We did not attempt to dig in it. On the Gamble farm, 31/2 miles up Owl Creek, were two mounds in the front yard. Each was 40x4 feet and the edges within 20 feet of each other. Both were thoroughly trenched, but nothing was found, except two small arrow-heads. It is singular that the Muskingum mounds contain so little. We cannot account for it save in this wise: that the culture was |

|

190 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

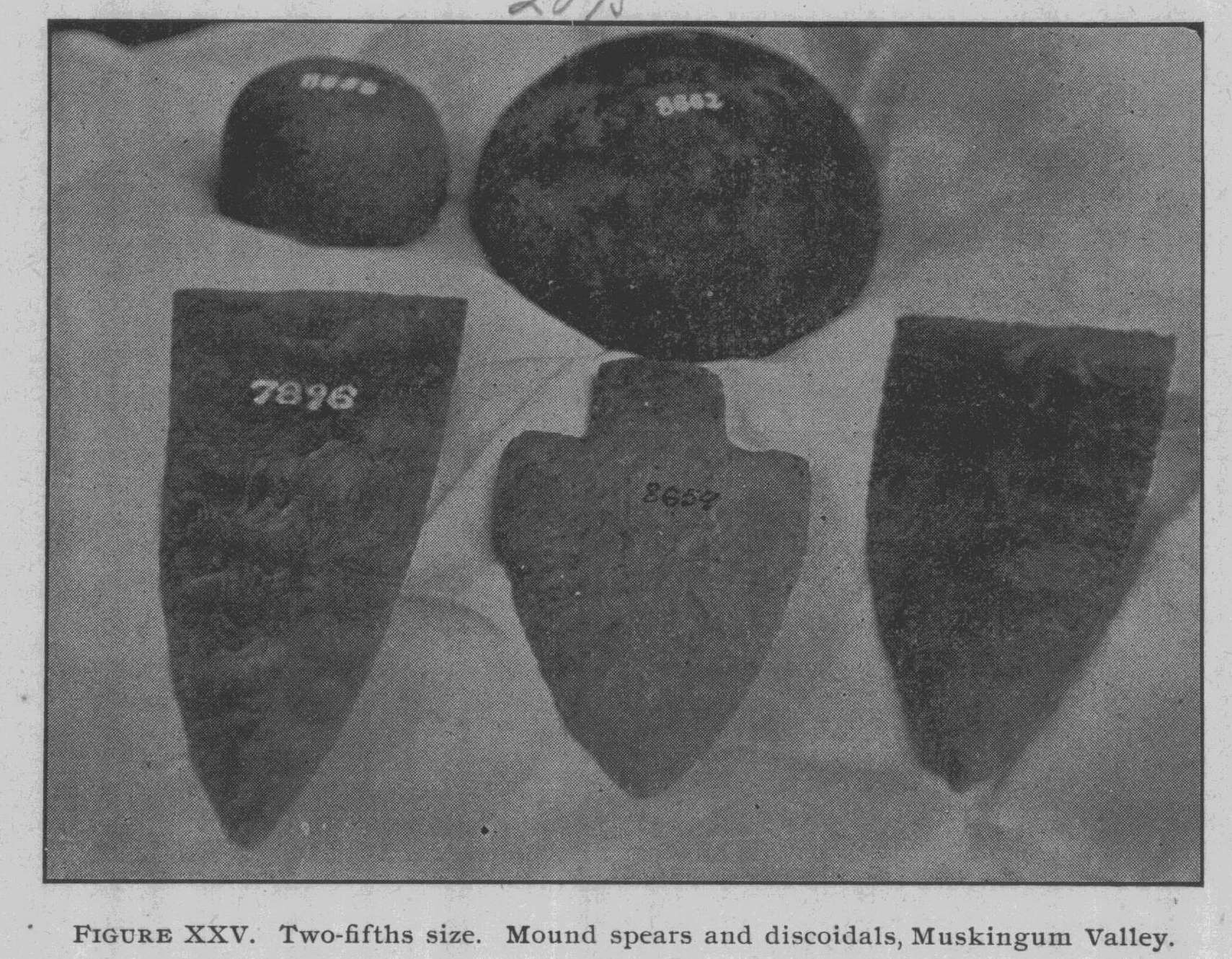

very low and the mortuary customs different from those in vogue in the Scioto valley. On the way back in passing a gravel pit we secured the skeleton of a young person. It had been buried near the pit by the workmen who exhumed it. Walhonding appears to have been built over several mounds and a village site. On the north edge of the village are two mounds yet standing. One owned by Mr. Johnson is 9 feet high and 69 feet in diameter at the base. Mr. P. Neff had sunk a trench through it several years ago. We found his trench to be 5 feet wide at the top and 4 at the bottom. He does not report having made any discovery. There seems to have been no considerable number of bur- ials in this structure, for we found only one decayed skeleton, near the center and 3 feet above the base line. Nothing re- mained but the teeth. Not far from the bones was a cone-shaped stone (see Figure XXV). There were a few broken and one |

|

|

|

whole arrow-head scattered through the soil. Little burnt earth and charcoal on the base. |

|

Report of Field Work. 191

The mound was very promising and we could not account for its lack of contents. See Figure VII.

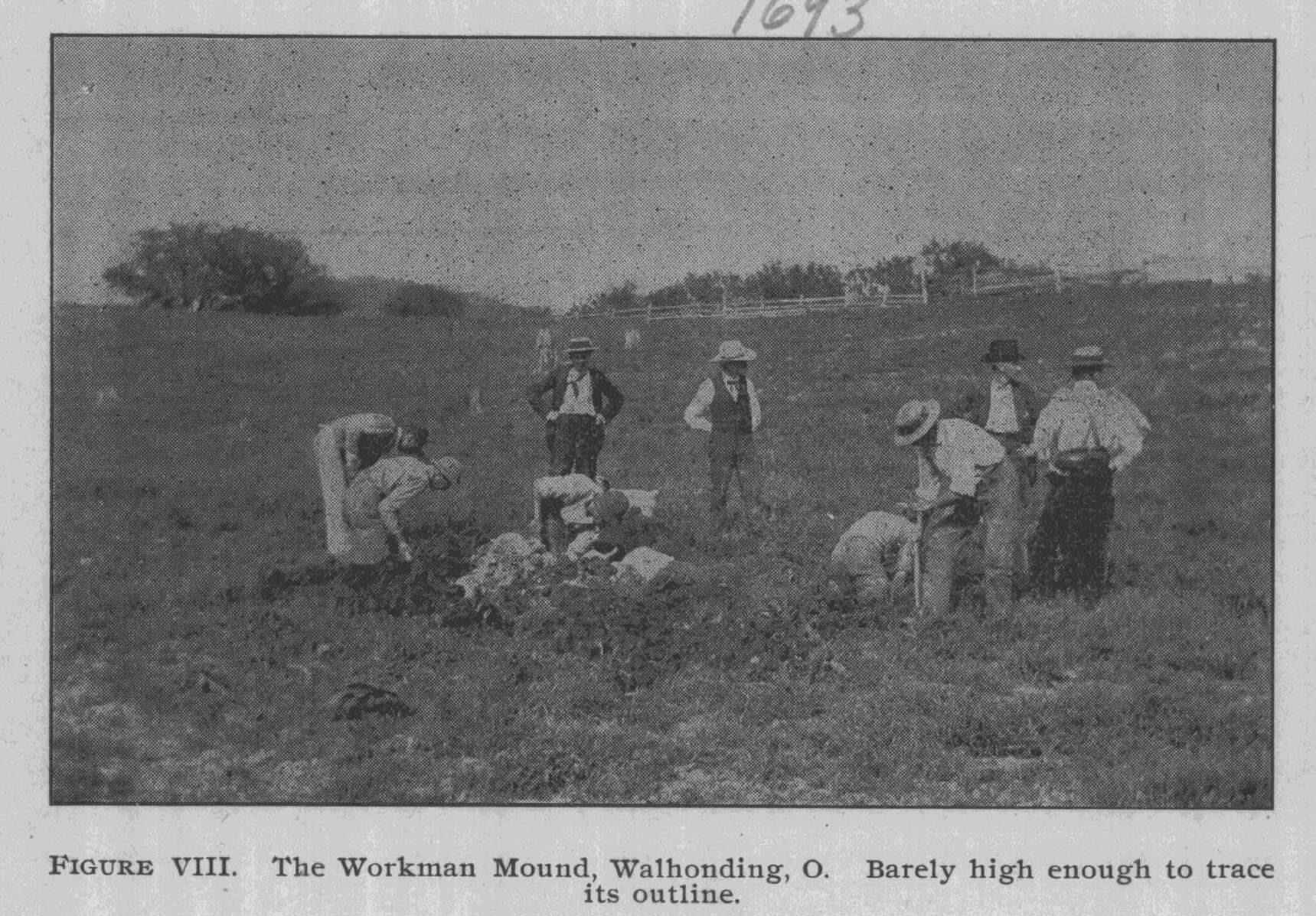

THE WORKMAN MOUND. On the farm adjoining Mr. Johnson's there is a small mound 2 feet high and 60 feet in diameter. It originally stood some 5 feet high but had been reduced by cultivation. The excavating re- quired but a trifle over an hour, yet the results were very sat- isfactory. (See Figure VIII). |

|

|

|

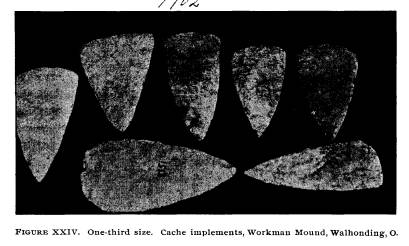

Near a decayed antler and other deer bones, was found an unfinished stone tube of hard material. The perforation is but begun, yet the stone is dressed and ready for polishing. A little south of the center of the mound were traces of bone, but so decayed that nothing could be preserved. Above these traces and lying in a layer with edges overlapping were 67 leaf-shaped implements.* They are all of clear chalcedony. North of them were some 500 small scales and fragments of flint (of the same kind) in a heap or pocket. We take it, from their size and * See also Figure XXIV, page 238. |

192

Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

form, that they are the very fragments

struck off in the man-

ufacture of the leaf implements. Never

having heard of a cache

accompanied by the chips and spalls, we

look upon this dis-

covery as one of interest to the

archaeological world.

Dr. Cyrus Thomas, in his Catalogue of

Prehistoric Works,

notices in Coshocton County 16 various

remains. Our survey

noted all of these, examining most of

them, and recorded some

thirty additional ones. Dr. Thomas says:

"At Flint Ridge, on

the north bank of the Mohican River,

between Walhonding and

Warsaw, numerous pits show that is was

much worked. There

is a thick layer of dark flint

overlooking a stratum of chalcedony;

the latter seems to have been the kind

sought." While most

of the implements in the valley for

twenty miles either up or

down from the quarries seem to be of the

Coshocton flint and

chalcedony, yet the Muskingum valley as

a whole was supplied

from Flint Ridge in Licking County. The

Coshocton quarries

are small and of limited extent compared

with those of Flint

Ridge. The same methods of quarrying

seem to have been in

vogue and a description is therefore

unnecessary.

A deposit of chalcedony (the implements

found in the Work-

man mound above Walhonding seem to be of

material from this

quarry) occurs upon the farm of Col. P.

Methan in the south

central part of Jefferson Township.

In Muskingum Dr. Thomas reports three

mounds and one

group of enclosures. The latter are near

Zanesville and were

described in "'Ashe's

Travels," page 108. The works are now

about obliterated.

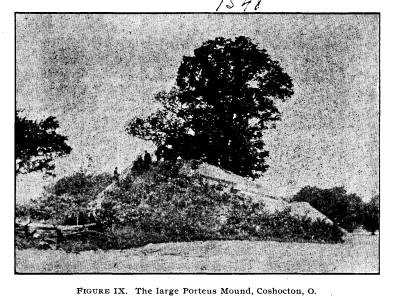

THE LARGE PORTEUS MOUND.

In the neighborhood of Coshocton there

were a large num-

ber of mounds and village sites. The

town itself has covered

two mounds and obliterated a large

village site. Few town sites

in the Ohio Valley can lay claim to

being both prehistoric and

historic, but Coshocton can justly

assume this honor. After the

mound period it was inhabited by the

Delawares, Mingoes, Shaw-

nees and other tribes from 1720 to 1790.

The student of Indian

and pioneer history is familiar with the

various expeditions sent

against the tribes of the Tuscarawas and

Walhonding. Memo-

|

Report of Field Work. 193

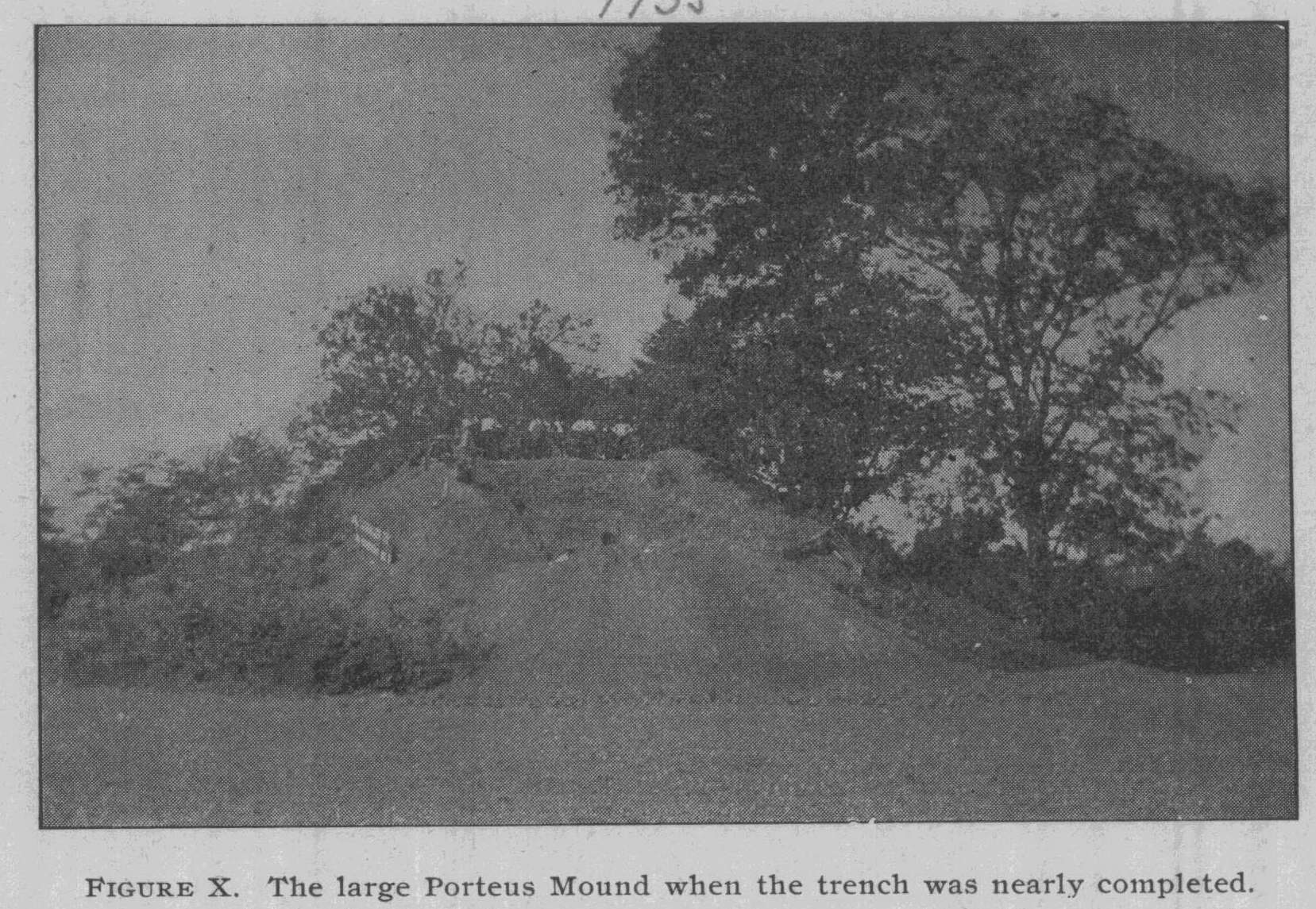

ries of such names as Logan, Cornstalk, the Half King, Pontiac, Brandt, etc., cluster about the place. The early missionaries- those self-denying Christians, Heckewelder and Zeisberger, also played a part in the history of the upper Muskingum. About two miles below Coshocton stand two mounds. Both are on the Porteus estate, the one twenty-three feet high and 120 feet base; the other, four and one-half feet high and fifty feet base. For many years persons have endeavored to secure per- mission to excavate them but without success. Mr. Joseph Porteus and his brother kindly gave consent for the examination of the interesting tumuli. Of the large mound little need be said. Sixteen men were employed day and night for four days in sink- ing a trench thirty-five feet wide and seventy feet long. The sides were loose and dangerous, and heavy bracing was necessary. It was composed entirely of earth and unstrati- |

|

|

|

fled. There were few pieces of charcoal noticed and no burnt earth. No difference in color was observed even on the bottom, and there were no soft places, the entire mass being hard packed. |

|

194 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

While work progressed a boy found a most beautifully chipped six-inch spear head by the base of the mound. (Specimen* 7896.) This mound is shown in Figures IX and X. It was im- possible to get the whole mound in the negative without re- moving the camera some 200 feet distant. On this account the structure appears to be smaller than it really is. Some idea of its height can be obtained by comparing the men who stand on the top with the structure from the plowed ground to its summit. After exceedingly laborious and dangerous excavation, the bottom of the structure was reached. To our chagrin one or two small bones, a ceremonial of galena, a few pottery fragments and flint chips were found. No burials were discovered, although tunnels were run in for several yards on the base line in various directions. This was disappointing, especially after the ex- penditure of a large sum of money. However, we learn again |

|

|

|

that it is not always the largest and most imposing monument which contains the greatest treasure. Failure to find anything cannot be charged to imperfect or hasty exploration-the whole * Museum number. |

Report of Field Work. 195

center of the mound was exposed by the

trench and tunnels for

a distance of thirty by twenty-five

feet. As it was desirable to

restore the monument to its former

shape, we engaged Mr. Por-

teus to fill our trench.*

Upon the same property is a small mound

situated about 400

yards north of the large one. It is four

and one-half feet high,

with a base of fifty feet. Mr. Porteus

says that it was originally

eight feet high, with a base of

thirty-five feet. As our force of

workmen was considerable, we were less

than half a day exam-

ining its contents.

Most tumuli are entirely of earth, but

this one was largely of

pure sand and rested upon a knoll of

sand. The burials were

three to four feet below the surface and

all considerably decom-

posed. Of seven skeletons exhumed, but

few fragments were

preserved. Numerous flint chips, a few

arrow-heads and three

bear tusks constituted the finds. No

order was observed in the

burials with reference to cardinal

points, nor were any two skele-

tons headed in a common direction.

The following day we visited a

fortification three miles up

the Walhonding upon Mr. Miller's farm.

It is on a hill some

200 feet high and overlooks the valley.

Many of the citizens of

Coshocton claim it to be a French fort,

but we would call it deci-

dedly Indian in form. It is some two

acres in extent, the em-

bankment low and broad. Where preserved

by woods it appears

to have originally been five feet high.

A long passage way from

the valley below leads up to it, and in

this respect the place is

peculiar. The passage is some fifteen

feet wide on the average

and walled on either side by natural

ledges eight to twelve feet

high. We think the enclosure merits

future investigation.

Up the Walhonding, three miles from

Coshocton, is a mound

five feet high and sixty feet in

diameter on the land of Mr. M. C.

Maxwell. Situated upon the second

terrace it is 200 yards from

the river. Some one had sunk a small

hole in the center. Mark-

ing a space 28x35 feet we removed about

all the area origi-

nally covered by the mound, and found

ten skeletons, some of

* At no time were less than sixteen men

employed and for two days

we had nineteen at work. No larger force

was ever put on a mound in

the Ohio Valley.

196 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

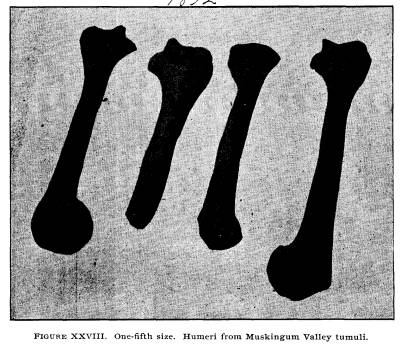

which were well preserved. The humeri

and other bones show-

ing peculiarities, we removed entire or

nearly so. Previous dig-

ging had disturbed two skeletons in the

center, cutting one body

in halves at the hips and destroying all

of another save the skull.

It was interesting to note that in the

eight years since the central

excavation had been made, the bodies

near it were more decayed

than those farther away, all of which

tends to confirm the facts

that the skeletons in a mound decay very

slowly if so placed that

water cannot reach them, and that a few

years of exposure to

moisture will cause more decay than

three hundred years of dry

interment.

As was remarked in the case of the small

Porteus mound,

no order was observed in the interment

of these remains. All

were extended and lay upon the base

line. A polished bone

knife or cutting tool, some arrow-heads,

pottery, etc., were found.

"Skeleton B" is the most

remarkable one in the mound.

When the cranium was reached, though

fragmentary, it was found

to bear evidences of having a section

about the size of a nickle

removed from the frontal bone on the

crown of the head.

Whether this is evidence of trepanning

or the result of a blow

from some round instrument, is to be

determined by one of our

medical experts. We have sent the

fragment to the Smithsonian

Institution and await the opinion of

experts in craniometry.

This having finished the work about

Coshocton, we set out

in a large skiff down the Muskingum for

Zanesville. Many,

many Indians, traders and pioneers have

made this trip, and as

we moved along we could but think of the

history of the stream

and its importance to our native

Ohioans.

At Duncan's Falls there are some tumuli,

and we opened

a mound upon the Wilhelm farm one mile

southwest of town,

upon a hill. It was of earth containing

numerous ashes. A

former excavation (small) had been put

down from the center,

and one skeleton found. The other had

not been disturbed by

this excavation. The first skeleton was

found on the north side

of the mound. The bones below the knee

were all decayed,

other parts well preserved and nearly

all saved. Near the center

was found the second skeleton. It was

buried in ashes with its

head to the north. Across the cervical

vertabrae was a clay pipe,

|

Report of Field Work. 197

broken, but yet in such fragments as will permit restoration. Near the skeleton was a large number of charred deer bones in ashes. No chips of flint occurred in the mound. In the left temple of the skull was a hole evidently made by some sharp pointed instrument. The cranium was preserved nearly entire. Dimensions of the mound, seventy feet broad and eight feet high. Down the river at Malta (opposite McConnelsville) we found many mounds and secured permission to excavate in several. At Mr. Sherwood's farm, three miles above Malta, we found two mounds upon a hill overlooking the Muskingum. The small one was of stone, the larger of earth. Their dimensions were eighteen feet broad, two feet high, and seventy feet broad and eight feet high. In the small one were fragments of decayed bone and two leaf-shaped spear heads of great beauty. The stones were large and ran from ten to thirty pounds in weight. But thirty feet intervened between the two mounds. In the large one we ran two broad trenches, finding a layer of ashes at the bottom. No skeleton could be located, but we found a nice discoidal stone and some flint chips. There is a village |

|

|

|

198 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications. |

|

|

|

site of some acres in extent upon the terrace below the mounds. The surface material upon it is not very thick. Figure XII repre- sents the large one. Five miles north of Malta on the McHenry farm is a clay mound which has been much cultivated. It is four feet high and seventy feet base. Absolutely nothing was found in it. (See Figure XI). Upon a high hill in the edge of McConnelsville is a large mound owned by Mr. Alderman. He consented to let us explore it, although his residence is but sixty feet distant and the mound really a lawn ornament. We did the work with care and re- stored the structure to its original form. Being well preserved, this fine earth monument stands eight feet high and sixty feet base. It overlooks the river and the Sprague mound in the center of town below. Perhaps the ele- vation of Mr. Alderman's lawn above low water in the river is 175 feet. In the center, and just above the base line, we uncovered some two bushels of ashes, and in them a child's remains. But for the remarkable preservative power of ashes, these bones would have decayed long ago, for the infant was but one or two months old. A most beautiful bone awl, one of the best ever found, |

Report of Field Work. 199

accompanied the remains. There were no

other objects. In a

south side excavation we found a large

spear head of Coshocton

County material.

Mr. Sprague, who owns a large mound

directly in the heart

of McConnelsville, gave us permission to

explore in the month

of October.

Accordingly, we went to McConnelsville

the 20th of October

and thoroughly explored Mr. Sprague's

mound, also giving a

lecture in the Opera House to citizens

on the work of the

society. It was found that the mound

could be best explored

by means of tunnels and therefore we

began at the south side

and ran two main tunnels nearly through

the structure. Branches

were run from these and the whole

interior of the mound

thoroughly explored. The tunnels were

about three feet wide

at the bottom and about four feet high

and, with the branches,

extended a total of 100 feet.

The base of each tunnel was about a foot

below the bottom

of the mound. Three skeletons were

encountered, one on the

east side, fairly well preserved, and

two upon the west, both de-

cayed. The former was near the top of

the mound and had been

covered by large, flat limestone slabs.

The latter were upon

the base line and we considered them

original interments. The

first may have been an intrusive burial.

With one of the decayed

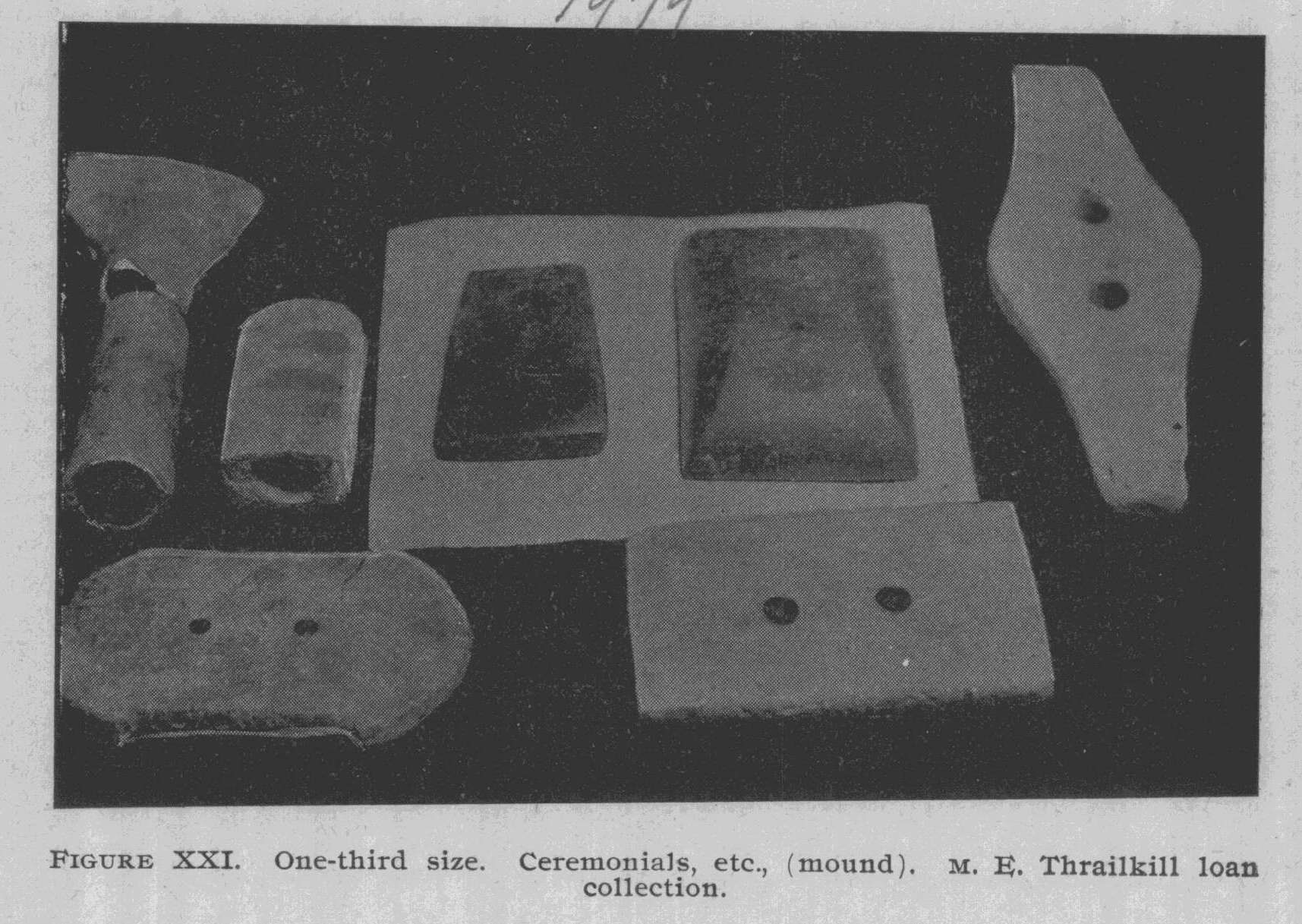

skeletons we found a fine coffin-shaped,

perforated ceremonial,

such as is shown (to the right) in

Figure XXI of this report. A

few curious water-worn stones, noted for

their odd shapes, and

a broken ceremonial lay upon the base

line near the second de-

cayed skeleton. There was nothing else

in the mound.

It was built upon a slight knoll or

elevation of gravel. Very

few stones and but little gravel

occurred in the mound. The clay

of which it was built is such as occurs

in the immediate neighbor-

hood. As this mound was in Mr. Sprague's

front yard and its

exploration necessarily caused him much

inconvenience, we are

under special obligations to him for his

kindness.

Although the Sprague mound was opened

five months after

Mr. O'Kane and myself returned from our

examination of the

Muskingum, it may be fairly stated that

with the Alderman mound

ended the work in this region.

200

Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

From McConnelsville we drove ten miles

down the river,

inspecting mounds, etc. From that point

to Marietta we ac-

cepted the testimony of Mr. Willard H.

Davis, of Lowell, Wash-

ington County, who is better posted than

any one else.

Rock carvings have been found at several

points along the

Muskingum.

Pictographs cut into the surface of a

large boulder lying

along the bank of the Muskingum were

noticed by several gen-

tlemen and communicated to Washington in

1842.* The marks

represented tracks of birds, figures,

etc. We inquired diligently

but no one had ever heard of it anywhere

along the river from

Coshocton to McConnelsville. We did

obtain description of a

carved face cut in relief on the walls

of the gorge near Brink

Haven on the Mohican in the edge of Knox

County. In con-

nection with this carving occurred one

of the greatest pieces of

vandalism ever brought to our notice. A

man living in Brink

Haven (now a barber in Springfield)

deliberately chipped off

the nose of the sculpture, after which

he mutilated the eyes and

mouth. We should have a law to punish

such offenders. Such

a thing would not be tolerated in

Europe, and the culprit would be

taught to respect antiquities.

Caleb Atwater, during his observations

on archaeologic mat-

ters, knew of mounds along the Muskingum

but does not at-

tempt to describe them, for he proceeds

down the river to Mar-

ietta. He observes, however, that the

mounds have not been

surveyed and that they are in Morgan

County near the river.

Possibly he refers to those near

McConnelsville.

Dr. Thomas, in his "Catalogue of

Prehistoric Works," lists

about one-tenth of the number.

Of the whole Muskingum region, as to

number of monu-

ments, of course Licking and Washington

Counties stand first.

We have purposely omitted descriptions

of the groups at New-

ark and Marietta, as these have been

described and redescribed

in every work upon Ohio archaeology

until the outlines are famil-

iar to all intelligent persons. But it

may not be amiss to call

* Bureau of Ethnology. Report for

1882-'83, page 22.

Report of Field Work. 201

attention to some facts connected with

them that are not gen-

erally known.

As to Licking County, Dr. Thomas, one of

the authorities

upon mounds, says:

"With the exception of Ross, this

is the most interesting

county archaeologically in the State.

From the great works at

Newark divergent mound systems reach to

the Ohio at Ports-

mouth and Marietta. Numerous earth

mounds and enclosures

occur, besides several stone enclosures

and probably more stone

mounds (some of great size) than any

other equal area in the

Mississippi valley."*

+"The high ground near Newark

appears to have been the

place, and the only one which I saw,

where the ancient occupants

of these works buried their dead, and

even these tumuli appear

to me to be small. Unless others are

found in the vicinity, I

should conclude that the original

owners, though very numerous,

did not reside here during any great

length of time.

"If I might be allowed to

conjecture the use to which these

works were originally put, I would say

that the larger works

were really military ones of defense;

that their authors lived

within the walls; that the parallel

walls were intended for the

double purpose of protecting persons in

time of danger from

being assaulted while passing from one

work to another; and

they might also serve as fences, with a

very few gates, to fence

in and enclose their fields, etc.

"The hearths, burnt charcoal,

cinders, wood, ashes, etc.,

which were uniformly found in all

similar places, that are now

cultivated, have not been discovered

here; this plain probably

being an uncultivated forest. I found

here several arrow-heads,

such as evidently belonged to the people

who raised other sim-

ilar works."

Dr. S. P. Hildreth, of Marietta, on June

8th, 1819, wrote

to Atwater regarding the fortifications

about Marietta and the

latter saw fit to insert the

communication in his work. That

* Bureau of Ethnology. Report for

1890-'91, pages 458-472.

+ Archaeologia Americana, published by

the American Antiquarian

Society, Worcester, Mass., 1820, by

Caleb Atwater, page 129.

202 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

part which is of most importance, and we

think, little known

among persons of archaeologic

tendencies, we will quote.

(Pages 137-8):

"The principal excavation or well,

is as much as 60 feet in

diameter at the surface, and when the

settlement was first made

it was at least 20 feet deep. It is at

present 12 or 14 feet, but has

been filled up a great deal from the

washing of the sides by fre-