Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

- 34

- 35

GENERAL HARMAR'S EXPEDITION.

BY BASIL MEEK, FREMONT, OHIO.

JOSIAH HARMAR was born in Philadelphia,

Pennsylvania, in

1753, and there died in 1813. He was a

captain in the First

Pennsylvania Regiment, Continental Army,

Lieutenant Colonel

of the same and served till the close of

the Revolutionary War.

He was in Washington's army from 1778 to

1780. In 1783 he

was made Brevet Colonel, First U. S.

Regiment. In 1787 he

was breveted Brigadier General, by

Congress, and assigned to

duty in northwest. He became

General-in-Chief of the army,

1789-1792, resigning the latter year.

General Harmar was Adju-

tant General of Pennsylvania, 1793-1799,

and was active in rais-

ing and equipping soldiers of the state

for Wayne's campaign

against the Indians in the Northwest.

Spain, France and England, as we know,

contended for

dominion over the country of the

Northwest, basing their re-

spective claims upon discovery and

settlement, but as it would

seem the principal ground of contention

was more that of occu-

pation than discovery. According to the

principle maintained

by civilized nations regarding the

territorial acquisition by dis-

covery, it was not sufficient as among

themselves, to discover

alone, but such discovery must be

followed by actual settlement

or occupancy. Discovery gave only the

right initiate; occupancy

must follow to consummate it.

But there was another power asserting

rights to sovereignty,

whose claim could not be entirely

ignored by the contending

powers mentioned. This consisted of the

native inhabitants, the

North American Indians, whose rights, if

occupancy governed,

were paramount to all others. They

considered themselves to

be the rightful owners of the land from

which they had sprung.

According to their traditions and

belief, they were, so to speak,

indigenes, their first ancestors having,

as a noted Indian chief

once said; "Come up out of the

ground." They knew nothing

(74)

General Harmar's

Expedition. 75

of the laws of civilized nations, and

never had been permitted

to have their "day in court,"

where their claims could have been,

or were, represented for them, and their

rights determined after

a fair hearing. That they should feel

not disposed to be dis-

possessed of what they sincerely

believed to be their just pos-

sessions without their consent is not to

be wondered at.

But according to the rule maintained by

civilized nations,

occupancy by savage people, gave only a

qualified right as against

discovery by civilized powers; complete

sovereignty, with the

right of disposition, was denied them;

and their rights acquired

by occupancy might be superseded or

destroyed by conquest or

forced purchase.

Discovery by the civilized was superior

to occupancy by the

savage upon the ground, it has been

claimed, that the Creator

could never have designed that a

comparatively few savages

should monopolize for hunting grounds an

extent of territory

capable of supporting many millions of

civilized people.

Our American doctrine maintained that

the Indians had no

complete fee in the lands occupied by

them, but only a qualified

vested right, by occupancy, which

however could only be invaded

in just wars or extinguished by treaty,

but like the other civilized

powers, our government denied to the

savages unrestricted do-

minion; and in its dealings and treaties

with them, these prin-

ciples were applied, and no complete

title to lands was recog-

nized in the savages, unless by express

grant from the govern-

ment.

The treaty of Paris in 1783, following

the Revolutionary

war, did not bring peace with the Indian

tribes of the North-

west; and though outwardly peace existed

with all the civilized

nations, the war continued with the

Indians. Their claims and

rights, whatsoever they were, had not

been recognized or in any

way settled, in the treaty with England

and the other powers

of 1783. The British, meanwhile, kept on

good terms with the

Indians, and intrigued with them, and

encouraged them in these

hostilities against the Americans, which

continued with savage

fury. Murderous incursions by the Miamis

and confederate

tribes from the Maumee and western

country, and by the Wyan-

dots and their immediate allies from the

Sandusky valley, were

76

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

frequent, attended with characteristic

savage cruelties. It was

believed that British officers at

Detroit furnished the Indians

with arms and supplies on occasion of

the Harmar expedition,

of which we are writing.

The principal western tribes claimed

that they had not been

parties to the treaty of Fort McIntosh

in 1785, and were not

bound by its provisions, respecting

boundary lines; that they

were rightfully, as original occupants

of the soil, entitled to the

unrestricted dominion over the

Northwest, and that no white set-

tlements should be made therein, and any

already made should

be destroyed. During the years 1787,

1788 and up to 1789,

ravages on the frontiers by the hostile

tribes were frequent.

The Federal authorities in the meantime,

were vainly endeavoring

to negotiate with these Indians, and

come to some peaceable

terms, by which settlers might be

suffered to remain unmolested

in their homes, and that other

settlements might be made, within

the disputed territory. The ultimatum of

the Indians was un-

restricted title to the Ohio River line.

Finally at Fort Harmar, January 9th,

1789, by the treaty

with all the nations, the treaty of Fort

McIntosh, as to

boundaries, was reaffirmed with the

concession to the Indians,

"that the individuals of said

nations shall be at liberty to hunt

within the limits ceded to the United

States, without hindrance

or molestation, so long as they demean

themselves peaceably or

offer no injury or annoyance to any of

the subjects or citizens

of the United States." It will be

remembered that the Six Na-

tions had ceded all their claims to

these lands to the United

States in 1784, by the treaty at Fort

Stanwix.

The Shawnees had by treaty made at the

mouth of the

Great Miami, at Fort Finney, January

3rd, 1786, ceded to the

United States all territory acquired by

it, by treaty with Great

Britain, and placed themselves under the

jurisdiction and pro-

tection of the United States.

The peace following the treaty at Fort

Harmar was of very

short duration. Hostilities by the

western Indians was renewed

within a few months thereafter, and by

the summer of 1790 the

raids of the Indians had become

unbearable.

Fresh robberies and murders were

committed every day

General Harmar's Expedition. 77

in Kentucky or along the Wabash and

Ohio. Writing to the

Secretary of War, a prominent

Kentuckian, well knowing all the

facts, estimated that during the seven

years which had elapsed

since the close of the Revolutionary

war, the Indians had slain

fifteen hundred in Kentucky itself, or

on the immigrant routes

leading thither, and had stolen twenty

thousand horses, besides

destroying immense quantities of other

property. In the mean-

time a number of ineffectual attempts to

conduct expeditions into

the enemy's country were made.

The Federal generals were also urgent in

asserting the folly

of carrying on a merely defensive war

against such foes. All

the efforts of the Federal authorities to

make treaties of peace

with the Indians which they would keep

had failed. The In-

dians themselves had renewed hostilities

after making treaties

as we have seen and the different tribes

had one by one joined

in the war, behaving with a treachery

only equalled by their

ferocity. With great reluctance the

National government con-

cluded that an effort to chastise the

hostile savages could no

longer be delayed, and those on the

Maumee and on the Wabash,

whose guilt had been peculiarly heinous,

were singled out as

the objects of attack.

On June 7, 1790, General Knox, Secretary

of War, in a

letter to General Harmar, directed him

to consult with Gov-

ernor St. Clair upon the means of

effectually extirpating these

bands of murderers, and outlining plans

of an expedition for

that purpose, but leaving the details of

the expedition to the

Governor and to General Harmar.

On July 15th, 1790, at Fort Washington,

the present site

of Cincinnati, where he had arrived from

Kaskaskia, Governor

St. Clair, in consultation with General

Harmar, determined to

send a strong expedition against the

Indians, located in their

towns above the headquarters of the

Wabash; and having been,

by General Washington, President of the

United States, vested

with authority to call for one thousand

militia from Virginia,

and five hundred from Pennsylvania, he

accordingly addressed

circular letters to several of the

County Lieutenants of the

western counties of those states.

Virginia, of which Kentucky

then formed a part, was called upon to

furnish the following

78 Ohio Arch. and Hist.

Society Publications.

number of men, to rendezvous at Fort

Steuben, on the 12th of

September: Nelson County, 125, Lincoln,

125, and Jefferson,

50, total 300. To rendezvous at Fort

Washington, September

15th, Madison County, 125, Fayette County,

200,

Bourbon, 125,

Woodford, 85, and Mason, 40, total 700.

Pennsylvania was requested to furnish

the following num-

ber to assemble at McMahen's Creek, four

miles below Wheel-

ing, September 3rd: Washington County, 220, Fayette, 210,

West Moreland, 110, Allegheny, 60, total

500.

The regular United States troops in the

west, were esti-

mated by General Harmar at four hundred

effective men. With

these the militia were to act in

concert. The manner of em-

ploying the whole force was arranged as

follows: Three hun-

dred of the Virginia militia were

ordered to rendezvous at

Fort Steuben, and with the garrison of

the fort, to march to

Vincennes and join Major Hamptramck, who

had orders to

call for aid from the militia of

Vincennes, and to move up the

Wabash and attack any of the Indian

villages on that river, to

which his force might be equal. The

remaining twelve hundred

of the militia were ordered to assemble

at Fort Washington,

and to join the regular troops at that

post under the command

of General Harmar.

The militia from the counties of the

Kentucky district, in

Virginia, began to assemble at the mouth

of the Licking river,

about the middle of September. They were

poorly equipped;

their arms generally bad and unfit for

service, and the men

were almost destitute of camp kettles

and axes. General Har-

mar, however, in the midst of many

difficulties, began to organize

them. In the course of two or three days

they were formed into

three battalions, under Majors Hall,

McMullen and Ray, with

Lieutenant Colonel Trotter at their

head. The Pennsylvania

militia arrived at Fort Washington about

the 24th of September.

They were badly equipped, and among them

many substitutes of

old infirm men, and young boys. They

were formed into one

battalion with Major Paul, under

Lieutenant Colonel Truby;

and four battalions of militia were

placed under the command

of Colonel John Hardin, subject to the

command of General

Harmar. The regular troops were formed

into two small bat-

General Harmar's Expedition. 79

talions under Major Pleasgrave Wyllys

and Major John Doughty.

The company of artillery which had three

pieces of ordnance

was commanded by Captain William

Ferguson. A small bat-

talion of light troops or mounted

militia was placed under the

command of Major James Fontaine. The

whole of General

Harmar's command may be stated as

follows:

Three battalions, Virginia Militia, one

battalion Pennsyl-

vania militia, and one battalion light

troops mounted, in all of

the militia, 1133; and 320 regulars in

two battalions, making the

total number of his troops 1453 men.

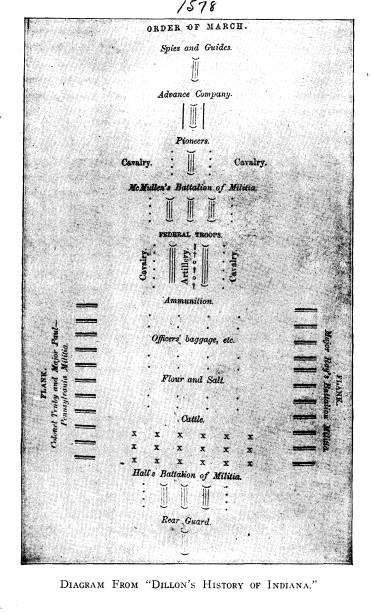

On September 26th, the militia, under

the command of

Colonel Hardin, moved from Fort

Washington, and advanced

into the country, in order to find for

the cattle and to open a

road for the artillery. The regular

troops under General Har-

mar, marched on the 30th of September,

and joined the militia

on the 3rd of October, when the order of

march was arranged

in the manner shown on page 80 herein.

The daily movements of the army were

recorded in a manu-

script journal, which was kept by

Captain John Armstrong of

the regulars, which is here given as

follows:

"September 30th, 1790, the army moved

from Fort Wash-

ington at half past ten o'clock, A. M.,

and marched about seven

miles N. E. Course. Encamped on a branch

of Mill Creek.

"October 1st. Took up the line of

march at half past eight

o'clock. At four o'clock halted for the

evening, having marched

about eight miles; general course a

little to the westward of

north.

"2nd. Moved forty-five minutes after seven o'clock.

Marched about ten miles, a northwest

course. The first five

miles were over a dry ridge to a lick;

then five miles through

a low swampy country, to a branch of the

waters of the Little

Miami, where we halted one hour; and

forty-five minutes after

one o'clock moved on for five miles, and

encamped on a muddy

creek, a branch of the Little Miami, one

mile from Colonel

Hardin's command.

"3rd. The army moved at eight

o'clock; passed Colonel

Hardin's camp and halted at Turtle

Creek, about ten yards

|

80 Ohio Archi. and Hist. Society Publications. |

|

|

General Harmar's Expedition. 81

wide, where we were joined by Colonel

Hardin's

command.

Here the line of march was formed.-Two

miles.

"4th. The army moved at

half past nine o'clock * * *

*,

and at three o'clock crossed the Little

Miami, about forty yards

wide; moved up it one mile, a north

course to a branch called

Sugar Creek. Encamped. -Nine miles.

"5th. The army moved from Sugar

Creek forty-five minutes

after nine o'clock. Marched through a

level county a N. E.

course up the Little Miami, having it in

view. * * * Halted

at five o'clock on Glade Creek, a very

lively clear stream. -

Ten miles.

"6th. The army moved ten minutes

after nine o'clock. The

first five miles the country was brushy

and somewhat broken;

reached Chillicothe, an old Indian

village; recrossed the Little

Miami; encamped at four o'clock on a

branch. - Nine miles, a

northeast course.

"7th. The army moved at ten

o'clock; the country brushy

for miles, and a little broken until we

came to the waters of the

Great Miami. Passed through several low

prairies and crossed

the Pickaway fork of Mad River, which is

a clear lively stream

about forty-five yards wide; encamped on

a small branch one

mile from the former; our course, the

first four miles, north,

then northwest.- Nine miles.

"8th. The army moved at half past

nine o'clock. Passed

over rich land, in some places a little

broken. Passed several

ponds and through one small prairie. A

northwest course.-

Seven miles.

"9th. The army moved at half past

nine o'clock. N. W.

course. Passed through a level rich

country, well watered,

course N. W. Halted half past four

o'clock, two miles south

of the Great Miami. -Ten miles.

"10th. The army moved forty-five minutes after nine

o'clock, crossed the Great Miami. At the

crossing there is a

handsome prairie on the S. E. side; the

river about forty yards

wide: * * * * halted on a large branch of the Great Miami

at half past three o'clock; the general course

N. W. * * *

-Ten miles.

Vol. XX-6.

82 Ohio Arch. and Hist.

Society Publications.

"11th. The army moved at half past

nine o'clock; marched

a northwest course seven miles, to a

branch where French traders

had a number of trading houses; thence a

north course four

miles, to a small branch and encamped at

five o'clock; * * *

- Eleven miles.

"12th. The army moved at half past nine o'clock. Our

course a little to the W. of N. W.

Crossed a stream at seven

miles and a half, running to the N. E.,

on which there are

several old camps, much deadened timber,

which continues to

the river Auglaize, about a mile. Here

has been a considerable

village. Some houses still standing.

This stream is a branch

of the Omi (Maumee) River, and is about

twenty yards wide.

From this village to our encampment our

course was a little to

the N. of W. Rich land. - Fourteen

miles.

"13th. The army moved at ten

o'clock. Just before they

marched, a prisoner was brought in, and

Mr. Morgan from Fort

Washington joined us. We marched to the

W. of N. W. four

miles, to a small stream, through low

swampy land; thence a

course a little to the N. of W., passing

through several small

prairies and open woods to an Indian

village, on a pretty stream.

Here we were joined by a detachment from

Fort Washington

with ammunition. - Ten miles.

"14th. At half past ten in the

morning, Colonel Hardin

was detached for the Miami village, with

one company of reg-

ulars and six hundred militia; and the

army took up its line

of march at eleven o'clock, a N. W.

course. Four miles, a

small branch; the country level; many

places drowned lands,

in the winter season. - Ten miles.

"15th. The army moved at eight

o'clock. N. W. course.

* * * * The army halted at half past one

o'clock on a branch

running west. - Eight miles.

"16th. The army moved at forty five

minutes after eight

o'clock. Marched nine miles and halted

fifteen minutes after

one o'clock; passed over a level country

not very rich. Colonel

Hardin, with his command, took

possession of the Miami town

yesterday (15th) at four o'clock, the

Indians having left it just

before. - Nine miles.

"17th. The army moved at fifteen minutes after eight

|

General Harmar's Expedition. 83

o'clock, and at one o'clock crossed the Miami river to the vil- lage. The river is about seventy yards wide, a fine transparent stream. The river St. Joseph, which forms the point on which the village stood, is about twenty yards wide, and when the waters are high is navigable a great way up it. |

|

|

|

"On the 18th I, (Armstrong) was detached with thirty men under the command of Colonel Trotter. On the 19th Colonel Hardin commanded in lieu of Colonel Trotter. Attacked about one hundred Indians, fifteen miles west of the Miami village, and from the dastardly conduct of the militia, the troops were obliged to retreat. I lost one sergeant and twenty-one out of thirty men of my command. The Indians on this occasion gained a complete victory, having killed in the whole, near one |

84

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

hundred men, which was about their

number. Many of the

militia threw away their arms without

firing a shot, ran through

the federal troops, and threw them into

disorder. Many of the

Indians must have been killed as I saw

my men bayonet many

of them. They fought and died

hard." Here ends the journal

of Captain Armstrong.

On the 18th, the following general

orders were published:

"CAMP AT THE MIAMI VILLAGE, Oct.

18, 1790.

"The General is much mortified at

the unsoldier-like be-

havior of many of the men in the army,

who make it a practice

to straggle from the camp in search of

plunder. He, in the

most positive terms, forbids this

practice in the future, and

the guards will be answerable to prevent

it. No party is to go

beyond the line of sentinels without a

commissioned officer, who,

if of the militia, will apply to Colonel

Hardin for his orders.

The regular troops will apply to the

general. * * * * The rolls

are to be called at troop and retreat

beating, and every man ab-

sent is to be reported. * * * * The

army is to march tomorrow

morning early for their new encampment

at Chillicothe, about

two miles from here.

"JOSIAH HARMAR, Brigadier

General."

On the arrival of General Harmar at the

Miami village,

about two-thirds of the militia

dispersed in search of plunder.

The "Chillicothe" referred to

by General Harmar was a Shawnee

village.

On the morning of the 19th, a detachment

under the com-

mand of Colonel Hardin marched a

northward course on the

Indian path, which led toward the

Kickapoo towns; and after

passing a morass about five miles

distant from the Miami vil-

lage, the troops came to a place where

on the preceding day a

party of Indians had encamped.

At this spot the detachment made a short

halt, and the

commanding officer stationed the

companies at points, several

rods apart. From here the detachment

moved on without re-

ceiving orders to make any arrangements

for an attack; and

when Captain Armstrong informed Colonel

Hardin that the

General Harmar's Expedition. 85

fires of the Indians had been

discerned, Colonel Hardin believed

that the Indians would not fight, and

rode in front of the ad-

vancing columns, until the detachment

was fired on from be-

hind the fires. The militia, with the

exception of nine, who re-

mained with the regulars and were

killed, immediately gave way,

and commenced an irregular retreat,

which they continued until

they reached the main army. Hardin, who

retreated with them,

made several unsuccessful efforts to

rally them. The small band

of regulars obstinately brave,

maintained their ground until

twenty-two were killed. Captain

Armstrong, Ensign Hartshorne

and five or six privates escaped from

the carnage, eluded the

pursuit of the Indians, and arrived at

the camp of General

Harmar.

The number of the Indians engaged on

this occasion has

been variously estimated. Captain

Armstrong placed the num-

ber at one hundred, while Colonel Hardin

estimated it at one

hundred and fifty. They were commanded

by the distinguished

Miami chief, Mish-e-ken-o-quoh, which

signifies, Little Turtle.

The ground on which this action took

place is about eleven miles

from Fort Wayne, near the crossing of

Eel River, by the Goshen

State road.

On the morning of the 19th the main body

of the army

under Harmar, having destroyed the Miami

village, moved about

two miles to the Shawnee village,

Chillicothe, which, after be-

ing destroyed, was left on the 21st, at

ten o'clock, A. M., the

army marching about seven miles on the

route to Fort Wash-

ington and encamped. Here, at the urgent

request of Colonel

Hardin, General Harmar sent back a

detachment of four hun-

dred men. Accordingly, late on the night

of the 21st. a corps of

three hundred and forty militia and

sixty regular troops, under

command of Major Wyllys, were detached

that they might gain

the vicinity of the Miami village before

day break, and surprise

any Indians who might be found

there. The detachment

marched in three columns. The regular

troops were in the

center, at the head of which Captain

Joseph Ashton was posted,

with Major Wyllys and Colonel Hardin in

the front. The

militia formed the columns to the right

and left. Owing to some

delay, occasioned by the halting of the

militia, the detachment

86

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

did not reach the banks of the Maumee

till some time after

sunrise. The spies then discovered some

Indians, and reported

to Major Wyllys, who halted the regular

troops and moved the

militia on some distance in front, where

he gave his orders and

plan of attack to the several commanding

officers of the corps.

General Harmar reserved to himself the

command of the regular

troops. Major Hall, with his battalion

was directed to take a

circuitous route around the bend of the

Maumee River, cross

the St. Mary's, and there, in the rear

of the Indians, wait till

the attack should be brought on by Major

McMullen's battalion.

Major Fontaine's cavalry, and the

regular troops under Major

Wyllys, were all ordered to cross the

Maumee at and near the

common fording place. It was the

intention of Hardin and

Wyllys to surround the Indians'

encampment; but Major Hall,

who had gained his position

undiscovered, disobeyed his orders,

by firing on a single Indian before the

commencement of the

action. Several small parties of Indians

were soon seen flying

in different directions, and the

militia, under McMullen, and

the cavalry, under Fontaine, pursued

them in disobedience of

orders, and left Major Wyllys

unsupported. The consequence

was, that the regulars, after crossing

the Maumee, were attacked

by a superior force of Indians and

compelled to retreat with

the loss of Major Wyllys and the greater

part of their corps.

Major Fontaine, at the head of the

mounted militia, fell, with

a number of his followers in making a

charge against a small

party of Indians; and on his fall, the

remainder of his troops

dispersed. While the main body of the

Indians, led by Little

Turtle, were engaged with the regulars

near the bank of the

Maumee, some skirmishing took place near

the confluence of

the rivers St. Marys and St. Josephs,

between detached parties

of Indians and the militia under Hull

and McMullen. After

the defeat of the regulars, however, the

militia retreated on the

route to the main army; the Indians

having suffered a severe

loss did not pursue them. As soon as the

news of the defeat

of the detachment reached the camp of

Hardin, he immediately

ordered Major Ray to march with his

battalions to the assistance

of the retreating parties; but so great

was the panic which

prevailed among the militia, that only

thirty men could be in-

General Harmar's Expedition. 87

duced to leave the main army. With this

small number, Ray

met Colonel Hardin, on his retreat. On

reaching the encamp-

ment, Hardin requested of Harmar that

the main army be sent

back to the Miami village. This request

General Harmar re-

fused, on the ground of lack of forage,

and inability to move

the baggage. He also claimed that the

Indians had received a

good scourging, and should they think

proper to follow him, he

would keep the army in perfect readiness

to receive them. The

general at this time had lost all

confidence in the militia. The

bounds of the camp were made less, and

at eight o'clock on

the morning of the 23rd, the army took

up the line of march for

Fort Washington, which was reached on

the 4th day of No-

vember. The army had lost one hundred

and eighty-three killed,

and thirty-seven wounded. Among the

killed were the follow-

ing officers: Major Wyllys and

Lieutenant Ebenezer Farthing-

ham of the regular troops; and Major

Fontaine, Captains Thorp,

McMurtrey and Scott; Lieutenants Clark

and Rogers, and En-

signs Bridges, Sweet, Higgins and

Thielkeld of the militia.

A considerable number of the regulars of

General Harmar's

army had followed Washington and other

generals in the War

of the Revolution. The killed of his

little army were buried in

the low bank of the Ford of the Maumee,

the present site of

Fort Wayne. General Harmar had lost the

best of the militia,

and of the regulars; and was forced to

struggle homeward to

Fort Washington as best he could, a

greatly disappointed com-

mander. It was indeed a dreary march.

The militia became

nearly ungovernable, so that at one time

Harmar reduced them

to order only by threatening to fire on

them with the artillery.

He had, however, succeeded sufficiently

to, in some measure,

remove the sting of his defeat, by the

destruction of the villages,

crops and other property of the enemy,

and the killing of many

of the warriors.

On October 20th, 1790, Governor St.

Clair, from Fort

Washington, wrote the Secretary of War

concerning the result

of the expedition, in which he said:

"I have the pleasure to inform you

of the entire success of

General Harmar at the Indian towns on

the Miami and St.

Joseph rivers, of which he has destroyed

five in number and a

88 Ohio Arch. and Hist.

Society Publications.

very great quantity of corn and other

vegetable provisions.

And on November 6th, he writes: "On

the 20th of last month,

I had the honor to inform you,

generally, of the success that at-

tended General Harmar. I could not then

give you the par-

ticulars, as the General's letters had

not reached me; it is not

necessary now, because he writes

himself. One thing, however,

is certain, that the savages have got a

terrible stroke, of which

nothing can be a greater proof than that

they have not attempted

to harass the army on its return. They

arrived at this place

on the 3rd instant, in good health and

spirits." It may be well

said to the optimistic Governor that he

could "Wrest victory

out of defeat!"

Notwithstanding the loss to the Indians,

they became more

than ever angry; all the western tribes

made common cause with

the Miamis, and banded together in more

open warfare. Their

murderous raids on the frontiers

continued and increased in

numbers, so that the settlers were kept

in constant fear of the

tomahawk and scalping knife. Subsequent

history relates the

further measures and expeditions

necessary to subdue the sav-

ages and bring peace to the harassed

frontiers; but these are

not within the limits of this article.

But it may be mentioned,

however, that in the spring of 1791, the

President appointed

Governor St. Clair Major General and

placed him in command

of the army. Colonel Richard Butler was

promoted to general

and placed second in command. It was

resolved to make another

campaign against the Indians in the

summer. General Harmar,

smarting under what he considered to be

unjust criticisms upon

his conduct of the expedition, demanded

a Court of Inquiry,

which was granted by General St. Clair,

Commander in Chief,

with General Richard Butler president,

and Colonels Gibson and

Darke members. (State papers military

affairs, Vol. 1, pages

20 to 36.)

The court sat at Fort Washington,

beginning September

15,

1791, and spent several days examining the

testimony. On

October 3rd General Butler transmitted

to General St. Clair

the proceedings and finding of the Court

of Inquiry. The

finding of the Court was highly

honorable to General Harmar,

(Vol. II St. Clair Papers, p. 251) fully

exonerating him from

General Harmar's Expedition. 89

any blame in regard to the expedition.

On the inquiry, the

principal witnesses in their testimony

attributed the failure of the

expedition to the insubordination of the

militia. General Har-

mar declined to take part in the

proposed St. Clair expedition,

resigned from the army and returned to

his home in Phila-

delphia.

In the preparation of the foregoing, the

following works

have been freely drawn upon,

"History of Indiana," by Dillon;

"Winning of the West," by Col.

Roosevelt, and "The St. Clair

Papers," by Smith.

GENERAL HARMAR'S

JOURNAL.

Diary of General Harmar from the Draper

MSS., by courtesy of the

Wisconsin Historical Society, Madison,

Wisconsin.

(Draper MSS. "W" Harmar's

Papers, Vol. II, pp. 335-348 incl.)

"Wednesday, Sept. 8th, 1790.-Fort Washington, H. Qrs.

Capt. McCurdy arrived here this morning

at daybreak, & left

the same morning at half past eleven

o'clock on his way to Fort

Knox at Post Vincennes.

"Sunday, Sept. 12th--This afternoon a Captain-2 subs-

3 serjeants & 30 privates

arrived, & encamped on the margin of

the Ohio, the lower Side of Licking.

They are militia from Ma-

son County.

"Wednesday, Sept. 16th.--Lt. Col. Hall

arrived this morning

at the mouth of Licking with 102 militia

from Bourbon county.

"Thursday, Sept. 17th.--Col.

Hardin & St. Col. Comt.

Trotter arrived this morning. The militia assembled are from

the following counties, viz: Fayette,

Mercer, Bourbon, Mad-

ison, Woodford & Mason.

"Saturday, Sept. 25th.-- Major Doughty

with the militia &

Federal troops arrived at the garrison

this day.

"Sunday, Sept. 26th.--This day the Kentucky militia, &

Major Paul with part of the Pennsylvania Militia marched &

encamped about 4 miles from the

garrison. Rained almost in-

cessantly during the whole night.

"Monday, Sept. 27th.- Rainy day - retards

our movement.

"Tuesday, Sept. 28th -

Still cloudy & Rainy.

90 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

"Thursday, Sept. 30th--

Marched this morning at eleven

o'clock, & encamped about 7 miles

from Fort Washington, on

the waters of Mill Creek. Hilly country,

but fine rich land; spice

bushes in abundance. Course N. E. by E.

"Friday, Octr. 1st,

1790.- Very fine day; marched thro' rich

level ground, well watered, but thick of

underbrush; encamped

on the waters of Mill Creek-course N. by

E. This day's march

about 9 miles. Col. Truby with the

cattle left at Fort Washing-

ton arrived and encamped with us this

evening-formed a

square encampment.

"Saturday, Octr. 2d. - Weather very fine. Marched & en-

camped upon the waters of the Little

Miami, through rich land

generally, but we passed over some but

middling: encamped in

a rich bottom in the military range, one

mile in the rear of the

militia under Colonel Hadin. This

day's march about 13 miles,

& a N. E. course.

"Sunday, Octr. 3d-- Marched

about two miles and joined

Colonel Hardin - encamped on Turkey Creek on the waters of

Little Miami early, about 10 o'clock in

the morning, & spent the

day in making arrangements for the order

of March, &c., &c.

We are about 31 miles from Fort

Washington on Clark's Old

Trace.

"Monday, Octr. 4th.-- Marched about eleven miles &

crossed the Little Miami--course about

N. E. by E. Several

horses lost last night, supposed to be

stolen by the Indians. En-

camped on Caesar's Creek, two miles from

the Little Miami, in

a square.

"Tuesday, Octr. 5th. Marched &

encamped on Glady Creek

- course about North- 10 miles - 52 from

Ft. Washington:

Generally bottom land, a few small

prairies we crossed.

"Wednesday, Octr.- 6th.- Marched about 10 miles & en-

camped on the waters of the Little

Miami, about 3 miles north

of Old Chillicothy: Recrossed

the Little Miami-passed

through two or three beautiful prairies:

62 miles from Ft. W.

Lieut. Frothingham with a few Federal,

& Capt. Hall (or Hale)

with a reinforcement of militia joined

me this evening. Sharp

frost last night - the first of the

season.

"Thursday,

Octr. 7th. - Marched about 9 miles & encamped

General Harmar's Expedition.

91

on Mad River, alias the Pickaway Fork of the Great Miami.

Good country- 71 miles from Ft. W.:

course a little W. of N.

"Friday, Octr. 8th-- Rainy -marched

about 9 miles & en-

camped within 131/2 or 14 miles of the

Great Miami - course a

little W. of N.- about 80 miles from Ft.

W.- good country.

"Saturday, Octr. 9th. - Rainy, disagreeable

weather-

marched & encamped within 31/2

miles of the Great Miami: About

90 miles from F. W. Course a little W.

of N.

"Sunday, Octr. 1Oth. - Clear, cool weather.

Crossed the

Great Miami at New Chillicothe on

its banks - Course W. of N.

distance from F. W. about 100 miles.

Several tracks of Indians

discovered this day - encamped on a

branch of the Great Miami.

Frost at night.

"Monday, October 11th.- Cool weather.

Passed through a

place called The French Store, situated

on the waters of the

Great Miami, & encamped on the same

small waters: About 12

miles this day, & 112 from F. W. A

level poor country, white

oak land, badly watered: course about N.

W.

"Tuesday, Octr. 12th-- Cloudy.

Passed another New Chil-

licothy, at which is Girty's house, situated on Glaze

Creek or

Branch of the Omee, which empties into

Lake Erie - & en-

camped about 7 miles to the N. W. of it -about

125 miles from

F. W. Course nearly N. W.--level poor

land, very badly

watered.

"Wednesday, Octr. 13th-- Disagreeable day.

Encamped on

a branch of the Omee near La Somer's old

house, about 135

miles from F. W. Course to the W. of N.

W. Very level coun-

try, but badly watered. This morning a

Shawanoese was taken

prisoner by the horse. Mr. Morgan

arrived this morning.

"Thursday, Oct. 14th - Rainy,

disagreeable day. Detached

Col. Hardin with a corps of 600 men

before me to the towns

this morning. The army marched &

encamped about 145 miles

from F. W. Very badly watered

country--course, a little to

the W. of N. W.

"Friday, Octr. 15th.--Cleared in the afternoon; Encamped

on the waters of Omee, about 153 miles

from F. W. Course

about N. W. We have travelled through a

very level country

92 Ohio Arch. and Hist.

Society Publications.

since we crossed the Great Miami, but

amazingly badly watered.

This day's march we had the sight

several times of water.

"Saturday, Octr.- 16th.- Fine, clear weather. The Savages

have evacuated (with the traders) their

favorite Miami Village

& towns. March & encamped about

163 miles from F. W. They

have left, Col. Hardin informs me, a

great quantity of corn and

vegetables behind. Level country - very

badly watered - course

nearly W.

"Sunday, Octr. 17th--Clear weather.

Gained the Miami

Village about noon this day. It is

beautifully situated between

the Rivers Miami and St. Joseph, and is

about 170 miles from

F. W. Course nearly due W. this day. But

in a direct line I

question whether it is more than 1OO

miles from the fort. The

traders and savages have retired from it

in the utmost consterna-

tion, leaving behind them vast

quantities of corn and vegetables,

supposed 10,000 bushels in ears.

"Monday, Octr. 18th--

Cloudy, & like for falling weather.

Rode to Chillicothy, a Shawanoe

Village, distant about two miles

from camp, & situated on the Omee -

contains about 80 houses

& wigwams. A vast quantity of corn

and vegetables hid in var-

ious places, holes, etc. Two Indians

killed & scalped this day

by the calvary, & one killed at

night by Capt. McLure. A great

number of horses lost last night.

"Tuesday, Octr. 19th. -The party under command of Col.

Hardin was worsted this day about ten miles from hence, by

about 100 or 130 Indians, owing to the shameful cowardly con-

duct of the militia who threw away their

arms and would not

fight. The loss is considerable- Capt.

Armstrong & the chief

part of the Federal part of the Federal

troops are supposed to

have fallen a sacrifice.

"Wednesday, Octr. 20th.--Fine

weather. Capt. Armstrong

got in this day much fatigued - 24 of

the Federal troops killed

& missing, & of the

militia-Total . Completed

burning & destroying the several

towns with their corn, &c. this

day. The regular troops were shamefully

left in the lurch by

the militia the clay before yesterday. (

?)

"Thursday, Octr. 21st--Fine

weather-Indian summer.

Having completed the destruction of the

Maumee Towns (as

General Harmar's Expedition. 93

they are called), we took up our line

of march this morning

from the ruins of Chillicothy for

Ft. Washington. Marched

about 8 miles -detached

Major Wyllys with 60 Federal & about

300 militia back to where we left this

morning, in hopes he

may fall in with some of the savages.

"Friday, Octr. 22nd,- Fine weather. The detachment un-

der Major Wyllys & Col. Hardin

performed wonders, although

they were terribly cut up. Almost the

whole of the Federal

troops were cut off, with the loss of

Major Wyllys, Major Fon-

taine, & Lt, Frothingham - which is

indeed a heavy blow. The

consolation is, that the men sold

themselves very dear. The

militia behaved themselves charmingly.

It is supposed that not

less than 100 warriors of the savages

were killed upon the

ground. The action was fought yesterday

morning near the

old fort & up the river St. Joseph. The savages never received

such a stroke before in any battle that

they have had. The

action at the Great Kanhawa, &c. was

a farce to it.

"Saturday, Octr. 23d.- Indian

Summer. Took up our line

of march this morning at 8 o'clock &

encamped about 24 miles

from the ruins of the Maumee Towns, or

the Miamii Village.

This day's march about 16 miles-much

encumbered with our

wounded men.

"Sunday, Octr.- 24th. --Cloudy & like for rain. Sent off

Mr. Britt early this morning before we

started (express) to

the Governor at Ft. W. Marched about 11

miles this day, &

35 miles from the ruins of the M. Towns

- encamped on the

waters of the Omee near La Somce's old

home.

"Monday, Octr. 25th. - Cold, rainy disagreeable weather.

Passed through a prairie about 4' or 5

miles in length, & en-

camped at Chillicothy near Girty's

house on Glaze Creek or

River, about 52 miles from the ruins of

the M. Towns. Snow at

night.

"Tuesday, Octr. 26th - Clear,

cold weather. Encamped at

a place called the French Store, the

farthest the Kentuckians

have ever penetrated the Indian country

this way. Fine food,

blue grass, &c. for our horses. It

is about 64 miles distant from

the ruins of the Maumee Towns. It is

situated on a branch of

the Great Miami.

94 Ohio Arch. and Hist.

Society Publications.

"Wednesday, Octr. 27th. - Fine, clear weather. Passed

through one of our old encampments 7

miles from the French

Store and a great branch of the Miami,

& encamped at New

Chillicothy on the banks of the Great Miami 7 miles further

(& supposed to be what Hutchins is

his Map called Tawixtive)

-a beautiful prairie about 3 miles from

the Great Miami before

we reached it. This day about 78 miles

from the ruins of

the Maumee Towns.

"Thursday, Octr. 28th. - Like for

falling weather. Marched

from New Chillicothy & encamped

about 16 miles from it, &

94 from Ft. W. We have now got into a

different kind of

country, finely watered (Symmes'

Purchase): From New Chil-

licothy to Miamii Village is the most

level & the poorest watered

I have ever seen.

"Friday, Octr. 29th. - Very rainy,

disagreeable day.

Marched through a succession of

beautiful prairies; passed two

branches of Mad River, & encamped on

the waters of the Little

Miami near the where the militiamen were

flogged-

about 110 miles from the ruins of the

Maumee Towns. Finely

watered, excellent country.

"Saturday, Octr. 30th.--

Marched about 4 miles & halted

for two hours at Old Chillicothy, on

the eastern side of the Lit-

tle Miami, in order to refresh our

horses. Then immediately

came into a large prairie (better than a

mile) - marched through

it & encamped on Glady Creek, the

waters of the Little Miami

(land belonging to Col. Hardin) about 8

miles from Old Chilli-

cothy, & about 122 miles from the

ruins of the Maumee Towns.

"All these Chillicothys are

elegant situations-fine water

near them and beautiful prairies. The

Savages knew how to

take a handsome position as well as any

people upon earth.

When they leave one Chillicothy, they

retire to another place &

call it after the same name. We are now

in the Virginia Officers'

Lands.

"Sunday, Octr. 31st--Fine,

clear weather-Indian sum-

mer. Marched & halted a little while

at what is called Sugar

Camp, about 5 miles - from thence to Caesar's Creek, a branch

of the Little Miami, 3 miles. Thence

crossed the Little Miami

General Harmar's Expedition. 95

(Symmes' Purchase again) 1 mile &

halted 4 miles to the S.

W. of it, about 135 miles from the ruins

of the Maumee Towns.

"Monday, Novr. 1st--Fine, warm weather. Marched 5

miles to Turkey Creek, a branch of the

Little Miami. From

thence to the Bridge on Muddy

Creek 3 miles - from thence 3

miles further: 146 miles from the ruins

of the M. Towns.

"Tuesday, Novr.- 2d.- Fine weather. Marchd by the Big

Lick & encamped on the waters of

Mill Creek about 7 miles from

Ft. W., & 159 miles from the ruins of the M. Towns. A great

deal of white oak land in this day's

march.

"Wednesday, Novr. 3d.-- Marched

and gained Fort Wash-

ington 7 miles, & about 166 miles

from the ruins of the Maumee

Towns- having in 5 weeks accomplished

the destruction of the

Maumee Towns, with the vast quantity of

corn, &c. therein, &

slain upwards of 100 of their

warriors, but not without consid-

erable loss on our side-about 180

Federal & militia.

"Thursday, Novr. 4th - Fine weather. Busy in discharging

the Militia.

"Friday, Novr. 5th. -The Kentuckians set off for their re-

spective homes yesterday.

"Saturday, Novr. 6th.- Sunday, Novr. 7th. Lt. Denny

set off

at rev. beat. Major Doughty with

the Penna. militia ascended the

Ohio this afternoon for the Muskingum.

"Monday, Novr. 8th. --Fine weather.

The Governor &

family also ascended the river this

morning for Muskingum.

"Thursday, Novr. 18th. -Early this morning detached Lt.

Kersey with a small party as far as the

bridge on Muddy Creek

with the Shawanoe prisoner, from that

place to set him at liberty

& let him run to his nation.

"Saturday, Novr. 20th. - Lt. Kersey returned this

morning,

taken the Shawanoe as far as the bridge,

who parted from him

seemingly with regret.

"Col. Mentzes, Inspector,

arrived here this morning, in a

Ky boat, with Lt.- McPherson of Capt. Trueman's

detachment &

57 Federal troops.

"Novr. 24th. -

Capts. Trueman & Cushing arrived.

"Novr. 25th. - Capt. Armstrong & Ens. Hartshorn start for

Vincennes.

96 Ohio Arch. and Hist.

Society Publications.

"Monday,

Novr. 29th. -An express

arrived from Col. Todd

& Col. Johnson, County

Lieutenants in Kentucky, informing that

the people are desirous of carrying on

another expedition against

the Savages (to strike the Weau Towns) - wishing

my consent.

I have returned them a favorable answer,

& despatched Cadet

Armstrong with

500 lbs. powder, & 1000 lbs.- lead & some pro-

visions, to be lodged at the mouth of

the Kentucky river for the

use of the militia upon the proposed

expedition.

"Tuesday, Novr. 30th. - Capt. Ballard

Smith & Lieut. Spear

arrived at the garrison this

evening--the former from the

Rapids - the latter from Post

Vincennes."

MAJOR FERGUSON'S

REPORT.

Major Ferguson's report of General

Harmar's expedition, made to

Richard Butler, Esquire, Major General

and President of the

Court of Enquiry, now sitting.

(Draper MSS. "U" Frontier

Wars, Vol. IV, pp. 47-56, and 58-61 incl.)

SIR:-I have duly considered the objects

which now em-

ploy your attention and investigation:

the following is a just de-

tail of the transactions of the late

Companies as far as came

within my knowledge. Some time about the

15th July it was

determined to carry on an Expedition

against the Miamie Vil-

lages. 1000 Militia from Kentucky and

500 from Pennsylvania

with what could be collected of the 1st

U. S. Regt. and one Com-

pany of artillery was to form the army.

The Militia from Kentuckey began to assemble at Fort

Washington about the middle of

September, these were very ill

equiped, being almost destitute of Camp

Kittles and axes, nor

could a supply of these essential

articles be procured. Their

arms were generally very bad and unfit

for service. I being

Commanding Officer of Artillery, they

came under my inspection

in making what repairs the time would

permit, and as a specimen

of their badness am to inform the court,

that a Riffle was brought

to be repaired without a Lock and

another without a stock; I

asked them what induced them to think

these guns could be

repaired at that time, and they gave me

for answer that they

were told in Kentuckey that all repairs

would be made at Fort

Washington; Many of the officers told me

that they had no idea

General Harmar's Expedition. 97

of the there being half the number of

bad arms in the whole

District of Kentucky as was then in the

hands of their men.

As soon as the principal part of the

Kentucky Militia arrived,

the General began to organize

them, in this he had many diffi-

culties to encounter. Col. Trotter

aspired to the command (altho

Col. Hardin was the eldest officer) and

in this he was encour-

aged both by men & officers, who

openly declared unless Col.

Trotter commanded them they would return

home; After two

or three days the business was settled

& they were formed into

three battalions under the command of

Col. Trotter, and Col.

Hardin had the command of all the

Militia. As soon as they were

arranged, they were Mustered, crossed

the Ohio and on the 25th

March and encamped about ten miles from

Fort Washington.

The last of the Pennsylvania Militia

arrived on the 25th

Septr. These were equipped nearly as the

Kentuckey, but were

worse armed, several were without any.

The Genl. ordered all

the arms in store to be delivered to

those who had none, and those

whose guns could not be repaired.

Amongst the Militia were a great many

hardly able to bear

Arms, such as old infirm men, and young

boys. They were not

such as might be expected from a

frontier country, viz. The

smart active woodsmen, well accustomed

to arms, eager and

alert to revenge the injuries done them

and their connections:

No, there were a great number of them

substitutes who prob-

ably had never fired a gun. Major Paul

of Pennsylva told me

that many of his men were so awkward

that they could not take

their gun locks off to oil them and put

them on again, nor could

they put in their Flints so as to be

useful; and even of such

materials the numbers came far short of

what was ordered, as

may be seen by the Returns.

On 31st Septr. the Genl. with

the Continental Troops marched

from Fort Washington to join Col. Harden

who had advanced

into the country for the sake of feed

for the cattle & to open

the Road for the Artillery. On the 3rd.

the whole army joined,

and was arranged in order of March,

Encampment & Battle,

these will appear by the orderly Book,

with this difference in

the Encampment; this space we were to

occupy when in order

Vol. XX-7.

98 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

of Battle (which was to be open) was

always to be fitted up

with our fires, nor was any intervals to

be left between Battalion;

this was done to prevent in some measure

the cattle & horses

from getting out of Camp, and the

Centinels Ground Camp had

orders not to let the cattle or horses

pass out after dark; just

before which time they were brought

within our fires. These

precautions aided by the care and

industry of Mr. Wells & his

assistants succeeded well in preventing

loss of Cattle; I have

been informed there were only two Oxen

lost from the time

the whole army took up the line of march

until it returned to

Fort Washington. But I am sorry to say

it was not the case

with the Pack Horses, the generality of

the people employed

in that department were ignorant of

their duty, Indolent and

inactive; nor was it the power of the

General to remedy these

defects, the shortness of the time for

assembling & organizing

the Army put it out of his power to look

about and select fit

characters, he was of course obliged to

take those that offered,

after he was in the woods it was out of

his power to exchange

them for better & punishments for

neglect of duty was out of

the question. The principles on which

the horses were employed

induced the drivers (who were chiefly

parties in the business)

to loose & otherwise destroy them,

rather than return them

to their owners, by this means the

proprietors had a high ap-

praisement paid them for their horses

and daily pay for services

untill they were lost, by adding to the

above the negligence of

Centinels, I account for the number of

Horses lost which in

my opinion was out of Gen. Harmar's

power to prevent. After

the Army was arranged we continued our

march without any

material occurrence untill the 13th

when the Horse fell in with

two Indians & took one of them

prisoner, who informed that

the Indians were not in force at the

Mamie Village. This day

we reached a place called the French

Store at which place a

French man who was then with the General

as a guide, had lived,

he informed that the Village was about

ten leagues distant. From

this place on the morning of the 12th, Col. Hardin was detached

with 600 men to endeavor to surprise the

Mamie Village, the

Army moved at the same time, and altho'

it rained the whole

day we continued our march with

diligence untill late, the horses

General Harmar's Expedition. 99

were ordered to be tied up this night to

enable the Army to move

early the next day which it did; this

diligence of the Army on

its march induces me to believe the

General was endeavoring to

guard against any disaster that might

happen to Col. Harden,

which I am of opinion would have been in

his power, for Col.

Harden had not gained more than four

miles of the army

in the first days march. On the 17th

the Army arrived at the

Mamie Village, here were evident signs

of the enemy having

quitted the place in the greatest

confusion. Indian dogs & Cows

came into our Camp this day which

induced us to believe the

families were not far off. A party of

300 men with three days'

provisions under the command of Col.

Trotter was ordered (as

I understood) to examine the country

round our Camp, but

contrary to the Generals orders returned

the same evening, this

conduct of the Colonel did not meet the

Generals approbation,

and Col. Hardin anxious for the

character of his countrymen

wished to have the command of the same

detachment for the

remaining two days which was given

him. This command

marched on the morning of the 19th & was the

same day shame-

fully defeated: Col. Hardin told me that

the number which

attacked him did not exceed 150 and that had

his people fought

or even made a shew of forming to fight

he was certain the

Indians would have run; But on the

Indians firing (which was

at a great distance) the Militia run

numbers throwing away their

arms, nor could he ever rally them.

Major Rhea confirmed the

same. I do not know what influenced the

General to make the

detachment on the 21st. But

from the enemy being flushed with

success on the 19th, it became

necessary, if in his power, to give

them a check to prevent the army from

being harrassed on its

return, which they might have done, will

readily be granted by

everyone who has the least knowledge of

the Indians, and an

Army encumbered with cattle & Pack

horses much worn down:

and altho the detachment was not so

fortunate as was reasonably

to have been expected, yet I firmly

believe it prevent the savages

from annoying our rear, as the never

made their appearance

after. With respect to reporting that

detachment which consisted

of four hundred chosen Troops I always

believed them superior

to 150

Indians which was the greatest number as

yet discovered;

100 Ohio Arch. and Hist.

Society Publications.

had it not been for misconduct &

disobediance of orders by the

officers who was on the command. I

understood that Major

Rheas Battalion had been advanced to

cover them which was

as many as could possibly have been

spaired, taking into view

that those in Camp could not be depended

on, & many were

without arms, having thrown them away.

To support with the

whole army was impracticable, the pack

horses being weak and

greatly reduced in numbers; the

Artillery Horses being much

reduced and unable to undergo much more

fatigue, but at the cer-

tain loss of the Artillery. As it was,

we were obliged to send

to Fort Washington for horses to assist

in hauling it in. The

march of the Army was regular and as

well conducted as was

possible to be done with Militia.

With respect to the General's conduct

report says he was

intoxicated all the Campain and unable

to execute the impor-

tant duties of his Station. I have

mentioned my commanding

the Artillery which was posted at the

head of the center Column,

and here the General chiefly was during

the march, of course.

I had an opportunity of seeing and being

with him through the

day in the morning I received my orders

from him and when

we halted to encamp he chiefly pointed

out the ground where

the Artillery should be posted, my duty

called me often to his

Tent before we marched in the morning

and after we halted in

the evening; in short had he been given

to Drunkeness I had as

good an opportunity of seeing it as any

other officers in the

Army, yet I do declare that from our

leaving Fort Washington

untill our return I never seen Genl.

Harmar intoxicated or so

as to render him unfit for the execution

of any duties: In him

and his abilities as an officer I placed

the greatest confidence never

doubting in his orders but obeying with

chearfulness being con-

scious they. were the production of

experience and sound judg-

ment.

I am sir

Your Most Obedient Humble Servant

W. FERGUSON, Major.

General Harmar's Expedition. 101

STATEMENT OF ENSIGN

BRITT.

To Major General Butler, President of

the Court of Enquiry, Fort

Washington.

Being called upon to relate the

circumstances attending Gen-

eral Harmar's expedition against the

Maumee Indians; the fol-

lowing have come particularly under my

notice.

With respect to the personal conduct of

General Harmar,

I knew that he was indefatigable in

making arrangements for

the execution of the plans which had

been formed for the ex-

pedition; and know also that the

difficulties were great which

he had to encounter in Organizing the

Militia, and endeavoring

to establish that harmony which was

wanting in their Com-

manding officers, Colonels Hardin &

Trotter which he accom-

plished apparently to their

Satisfaction. He was at all times

diligent in attending to the conduct of

the Officers in the dif-

ferent departments of the Army, and was

always ready to

attend to such occurrences as were

consequent to the same-

and the necessary exertions to have his

orders carried into ex-

ecution were not wanting-but there were

great deficiencies on

the part of the Militia-either owing to

the want of authority

in some of their Officers, or from their

Ignorance or inatten-

tion. Indeed the generality of them

Scarcely deserved the name

of anything like Soldiers. They were

mostly substitutes for

others-who had nothing to Stimulate them

to their duty.

As to the disposition for the Order of

March, form of en-

campment, and Order of battle; they are

matters which I being

a young Officer can say little about. I

presume they will answer

for themselves.

The General's motives for detaching Col.

Hardin on the 14th

October, when he was told we were but 10

Leagues from the

Indian Town-I supposed to be from

information he received

by a prisoner who was taken on the 13th.

That the indians at

the Maumee Village were in great

consternation and confusion-

and the prospects were they might be

easily defeated if found

in that Situation. In order to support this detachment, the

Horses of the army were ordered to be

tied up at night, so that

the whole army might be ready to march

early in the morning;

which was done accordingly and when

Colonel Hardin reached

102 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society

Publications.

the Village the main body was not more

than 5 or 6 miles in his

rear.

The detachment under Colo. Trotter was

ordered to recon-

noitre for 3 days the neighborhood, to

endeavor to find out the

Savages, who had fled from their

Towns-this party returned

the evening of the same day they

Started-and next morning

Col. Hardin marched with the same party

and fell in with the

Indians, and an engagement ensued in

which he was routed-

Owing to the cowardly behaviour of the

Militia under his com-

mand.

The motives which I conceived led to the

detaching the party

under Major Wyllys on the 21st Were

that the Indians having

avoided engaging the whole army, would

collect at their Towns

and harrass the rear and flanks, as much

as possible on its re-

turn; and a Stroke at them before they

could assemble in large

bodie would prevent their doing it with

much effect. The party

accordingly met with the Indians and a

battle followed, in which

numbers were killed on both sides. The

moment the news of

this arrived in Camp, Major Ray with his

Battalion of Kentucky

militia was ordered to March to the

support of Major Wyllys;

but did not proceed far before they

returned.

Any Occurrences that followed this last

action I am unac-

quainted with, as I was sent from the

Army with dispatches for

his Excellency Govr. St. Clair then at

this place.

FORT WASHINGTON; Septr. 16th, 1791.

D. BRITT, Ensign 1st U. S.

Regt.

DIARY OF LIEUTENANT

DENNY.

FORT WASHINGTON, September 16th'

1791.

The honorable

MAJOR GENERAL BUTLER

President of Court of Enquiry.

(Draper MSS. "U" Frontier

Wars, Vol. IV, pp. 25-33 incl.)

SIR: Agreeably to your directions I

present the court with

the following detail of circumstances

relative to the campaign

carried on by General Harmar against the

Maumee Towns:

July 11th, 1791 Governor St.

Clair arrived at Fort Washing-

General Harmar's Expedition. 103

ton from the Illinois country, he

remained only three days, during

which time it was determined that

General Harmar should carry

on an expedition against certain hostile

tribes of Indians, for

which purpose, I understand, he was to

have 1000 Militia from

Kentucky & 500 from Pennsylvania

with all the federal troops

on the Ohio.

15th. The Governor embarked for New York, intending, on

his way, to order out the Militia as

soon as possible; I believe

the 15th of September was the

appointed time for the army to

assemble at Fort Washington.

General Harmar began his preparations,

and every day was

employed in the most industrious manner.

The calculations for

provisions, horses & stores were

immediately made out, & orders

given accordingly. Great exertions were

used by Captn. Fer-

guson to get in readiness the artillery

& military stores, & in-

deed every officer was busily engaged

under the eye of the Gen-

eral in fitting out necessary matters

for the expedition, but par-

ticularly the quarter master-not a

moment's time appeared to

be lost.

15th

& 16th

of Sept. The Kentucky Militia arrived, but in-

stead of seeing active rifle men, such

as is supposed to inhabit

the frontiers, we saw a parcel of men,

young in the country, and

totally inexperienced in the business

they came upon, so much

so, that many of them did not even know

how to keep their

arms in firing order. Indeed their whole

object seemed to be

nothing more than to see the country,

without rendering any ser-

vice whatever -a great many of their

guns wanted repairs,

& as they could not put them in

order, our artificers were obliged

to be employed - a considerable number

came without any guns

at all. Kentucky seemed as if she wished

to comply with the

requisitions of Government as

ineffectually as possible, for it was

evident, that about two-thirds of the

men served only to swell

their number.

19th Sepr. A small detachment of Pennsylvania militia ar-

rived.

22nd. The

Governor returned from New York.

25th. Major Doughty with two companies of

federal troops

joined from Muskingum, & the remains

of the Pennsylvania Mi-

104 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

litia came this

day - the Militia last mentioned were similar to

the others - too

many substitutes. The General lost no time in

organizing

them, tho he met with many difficulties. The Col-

onels were

disputing for the command, & the one most popular

was least

entitled to it. The General's design was to reconcile

all parties,

which he accomplished after much trouble. The

Kentuckians

composed three Battalions under the Majors.

Hall, McMillion

& Rhey, with Lt. Col. Coml. Trotter at their

head. The

Pennsylvanians were formed into one Battalion under

Lieut Col.

Truby and Major Paul, the whole to be commanded by

Colonel John

Hardin, subject to the orders of Genl. Harmar.

26th Sepr. The Militia marched on the rout towards the

Indian towns.

30th. The General

having got forward all the supplies that

he expected, he

moved out with the federal troops formed into

the small

Battalions under the immediate command of Major

Wyllys & Major

Doughty, together with Captain Ferguson's

company of

artillery, & three pieces of ordnance.

October 3rd.

General Harmar joined the advanced troops

early in the

morning, the remaining part of the day was spent

in forming the

line of March, the Order of Encampment &

Battle, and

explaining the same to the militia field officers. Gen-

eral Harmar's

orders will shew the several formations.

4th. The army took up the Order of March as is

described

in the orders.

5th. A

reinforcement of horsemen & Mounted infantry

joined from

Kentucky. The Dragoons were formed into two

troops, the

mounted rifle men made a company & this small Bat-

talion of light

troops were put under the Command of Major

Fontain. The

whole of General Harmar's command then may

be stated thus-

3 Battalions of

Kentucky Militia ......................

1 Battalion

of Pennsylvania Militia ................... 1,133

1 Battalion

light troops mounted

Militia...............

2 Battalions federal

troops ............................ 320

Total .......................................... 1,453

General Harmar's Expedition. 105

The Line of March was certainly one of

the best that could

be adopted & great attention was

paid to keep the officers with

their commands in proper order, &

the pack horses etc. as com-

pact as possible.

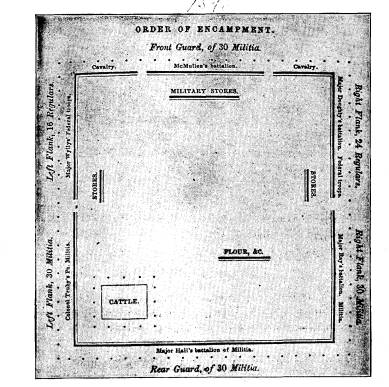

The Order of Encampment appeared to be

well calculated

not only for defense but to preserve the

horses & cattle from

being lost; however, notwithstanding

every precaution was taken,

& repeated orders given to the

horsemaster to hopple well their

horses, and directions to the Officers

& men not to suffer any to

pass through the lines, many of them,

owing to the carelessness

of the Militia, & the scarcity of

food, tho great attention was

paid in the choice of ground, broke

loose and strayed through

the lines after night, & even passed

the chain of sentries which

encircled the camp, and were lost -

patroles of Horsemen were

ordered out every morning by daylight to

scoure the neighbour-

ing woods & to bring in any horses

that might have broke

through the lines; and a standing order

directed the picquets

to turn out small parties & drive in

every horse. This was done,

I believe, to expedite the movement of

the army. There was

no less attention paid to securing the

cattle--every evening

when the army halted, the guard which

was composed of a

commissioned officer & 30 or 35 men,

built a yard always within

the chain of sentries & sometimes in

the square of encampment,

& placed a sufficient number of

sentries round the enclosure,

which effectually preserved them. There

was not more than 2

or 3 head lost during the whole of the

campaign.

13th October. Early in the morning a patrole of horsemen

captured a Shawanoe Indian.

14th October. Colonel Hardin was detached with 600 light

troops to push for the Miami Village. I

believe that this detach-

ment was sent forward in consequence of

the intelligence gained

of the Shawanao prisoner, which was,

that the Indians were

clearing out as fast as possible, and

that if we did not make

more haste, the towns would be evacuated

before our arrival.

As it was impossible for the main body

with all their train to

hasten their march much, the General

thought proper to send

on Colonel Hardin in hopes of taking a

few before they would

all get off. This night the Horses were

all ordered to be tied

106 Ohio Arch.

and Hist. Society Publications.

up that the army might start by day

light on purpose to keep