Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

JAMES M. MORRIS

No Haymarketfor Cincinnati

As the news spread from Chicago of the

events of May 4, 1886, a new word came to

be emblazoned into the hearts and minds

of the American people. That word-

connoting fear, revolution, anarchism,

and terror-was "Haymarket." Every man

reading the newspapers or talking with

his friends and neighbors of the events of

that day could not but be aware of the

"fact" that the anarchists who had wormed

their way into the bloodstream of

American life had finally let loose their poison.

Innocent victims had paid the price.

Who could tell where the vile contagion of

revolution and death might break out

again? Would it be in the East, in Boston or

Providence, or would it be in another

industrial midwestern city, such as Cleveland,

Cincinnati, or St. Louis? Which city

would next be pulled into the fiery cauldron of

revolution and death? Such fears may

have been groundless, but they persisted

nonetheless, aided by the newspapers

across the land which were filling their col-

umns with inflammatory news from

Chicago and other cities for days on end. The

hard facts of what had actually

happened were usually obscured or deliberately ig-

nored.

The events scheduled for Chicago's

Haymarket affair had been arranged long be-

fore May 4, and bloodshed and violence

had not been anticipated. The original in-

tention of the organizers was to call a

general strike to force acceptance of the eight-

hour day, an idea neither new nor

radical in the American labor movement at this

time. The plan for a nationwide general

strike had come from the moderate Feder-

ation of Organized Trades and Labor

Unions. This national organization of trade

unions, formed in 1881, had voted at

its 1884 convention to submit to all labor or-

ganizations the idea of a general

strike for the eight-hour day to take place on May

1, 1886. From this beginning the

movement grew, especially among the trade

unions, although many members of the

rival Knights of Labor also supported the

idea.1

In Chicago the strikers and the

strikebreakers, brought in to work in their place at

the McCormick Harvester plant, first

clashed on May 3 after two days of com-

parative quiet. The police intervened,

and in the melee that followed four persons

were killed. The local

radical-anarchist members of the Black International (very

1. For a scholarly description of the

events of Haymarket, see Henry David, The History of the Hay-

market Affair: A Study in the American

Social-Revolutionary and Labor Movements (New York, 1936), es-

pecially pp. 162-167, 182-205.

Mr. Morris is Associate Professor of

History at The Christopher Newport College of the College of

William and Mary in Virginia.

|

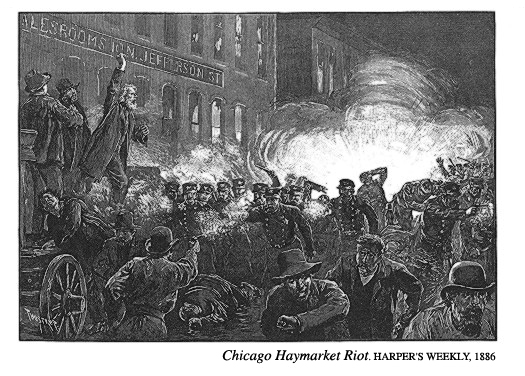

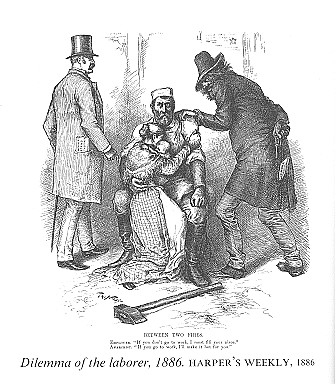

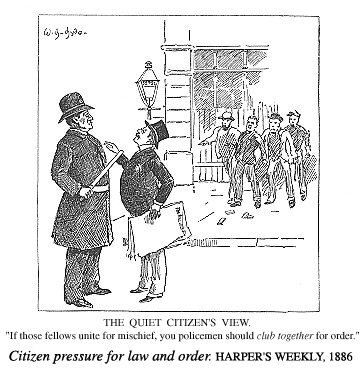

few in number and expressing a distinctly minority view among the Chicago work- ingmen) then attempted to take advantage of the situation by calling a protest meet- ing for the following evening-this to be at Haymarket Square on Randolph Street. Three thousand persons were in attendance and were treated to fiery speeches by prominent local anarchists. Yet all was peaceful, and as rain began to fall the crowd began to drift away. At this point a contingent of two hundred Chicago po- licemen under the command of an overzealous captain appeared and ordered the remaining participants to disperse. As the police moved in, someone-whose iden- tity is a mystery to this day-threw a bomb into the ranks of the policemen and seven were either killed outright or suffered mortal wounds in those brief moments of confusion and death. Out of this incident came a sense of local and national outrage and fear ending eventually in the execution of five known Chicago anarchists for crimes of murder. They were hanged because they were anarchists and not because anyone proved they had thrown the bomb or conspired in the crime. Chicago in the immediate af- termath of the Haymarket "riot" went through days of recrimination and hatred. Milwaukee and St. Louis also saw mob violence and radicalism in the days that fol- lowed, but Cincinnati did not. Although many foreign-speaking people were in the labor force, Cincinnati workingmen turned their backs on turbulence and radicalism during those tense, critical days in May and reaffirmed their commitment to order and moderation. The reasons why there was no Haymarket violence lay within the city and her citizens and in the history and nature of the labor union movement. By the middle years of the 1880's both the labor movement and radicalism had emerged in Cincinnati. Trade unionism had struggled from humble beginnings in the 1840's and 1850's to become the preferable response by many workingmen of the city to the tremendous problems ushered in by the advancing Industrial Revolu- tion. The road had not been easy for the pioneer advocates of the union move- |

No Haymarket for Cincinnati

19

ment. The Panic of 1857 had virtually

destroyed everything that had been gained

in the early days. Trade unionism was

not revived until 1863, only to be challenged

by the post-war recession and pushed to

the brink of extinction by the financial de-

bacle of 1873. But the movement clung

tenuously to life and by 1879 gradually

found acceptance as part of the economic

life of Cincinnati.

During these four decades of erratic

development, the workers had tried and dis-

carded many alternative paths to a

better lot for the wage earner. They had tested

producers' and consumers' cooperatives,

but had found them wanting. They had

tried political action through the

regular political parties, but had rejected this

method as frustrating and unprofitable.

They had then been invited to espouse

more radical types of political action

which would have overthrown-or at least ser-

iously compromised-the capitalistic

system. Such doctrines had been discarded af-

ter no more than a brief flirtation. The

Cincinnati workingman who involved him-

self in collective action, like the

great majority of workingmen across the country,

had determined by trial and error that

his best opportunity for decent working con-

ditions and a better bargaining position

with his employer lay in united action

within craft union membership. It was

thus that trade unionism appeared as the

strongest workingmen's movement in the

city by the 1880's, a movement somewhat

united through a weak local Trades and

Labor Assembly.2

Even though the early months of 1886

appeared rather quiet on the Cincinnati la-

bor scene, the subject of strikes, labor

organizations, and possible violence definitely

were in the air. The harnessmakers'

strike during February and March had re-

vealed the ominous presence of a secret

military society-styled "communistic"-in

the city, and reports were carried daily

in the newspapers of the giant strike by the

Knights of Labor against the

southwestern railroad system of Jay Gould.3 Interest

and apprehension began to mount even

further when it became known that a na-

tionwide general strike for the

eight-hour working day was planned for May 1 and

that Cincinnati operatives would join in

the movement.

On March 31, the Enquirer, generally

favorable to the labor movement, published

an interview with Terence Powderly of

Philadelphia, Grand Master Workman of

the Knights of Labor. Taken from the New

York Sun, it was entitled, "Leader of

the Knights. A Man Who Abhors Strikes

and Looks Ahead a Long Way." A very

friendly article, it showed Powderly to

be a perceptive and hard working representa-

tive of labor. But shortly thereafter

the newspaper published an article arguing

that, with the strike situation growing

more serious, the interests of the general pub-

lic could best be served if all

outstanding difficulties were promptly cleared up.4

The following day the Commercial

Gazette, usually bitterly opposed to labor, be-

gan its bodeful comments on current and

possible future events by warning that the

Knights of Labor could be dangerous if

the leaders could not control their local as-

semblies. Such lack of control brought

about destructive strikes and boycotts, the

paper argued, such as were occurring in

the southwestern railroad strikes. The arti-

cles played upon the fears of the public

by charging that the workers on the Mis-

souri Pacific Railroad had "created

a reign of terror and violence, destroying the

2. For a complete description of the

rise of unionism and radicalism in Cincinnati prior to 1886, see

James M. Morris, "The Road to Trade

Unionism: Organized Labor in Cincinnati to 1893," (unpublished

Ph.D. dissertation, University of

Cincinnati, 1969), 1-261.

3. Cincinnati Enquirer and

Cincinnati Commercial Gazette, February 9 to March 16, 1886.

4. Enquirer, March 31, April 9, 1886.

|

|

|

railroad property, intimidating workmen by savage assaults and by a demeanor which showed that persistence in their work Would sacrifice their lives..." After heaping general criticism on the idea of the eight-hour day in the weeks that fol- lowed, the paper made its final, negative prognostication on April 26 when it said: The workingmen of this country are not, we take it, about to stop work. The fable of the strike of the various members of the body, all being dissatisfied each with its parts in the gen- eral labor carried on in the several departments, is not likely to come to pass on the Ameri- can Continent. ..."5

The third major Cincinnati daily, the Times-Star, reserved comment until after the strike was imminent in the city and then launched into a series of vicious attacks on the strikers. The German-language newspapers also withheld comment until then. The attitudes of these newspapers would soon be revealed as markedly sim- ilar to the Commercial Gazette. It thus appears that neither the friends nor the enemies of labor among the press were in favor of strikes or violence as May 1, 1886 approached. Since the newspapers constituted a major force of public opinion in the city, their reports would undoubtedly be an important indication of how Cincin- nati, including its workingmen, would accept the events which were to transpire in the early days of May. The ministers, too, when they infrequently looked to the question of social justice and the lot of the workingman, were clearly opposed to strikes and violence. The Methodists appear to be the only Protestant clergymen who approached the prob- lem before trouble came. On April 18 Rev. C. Ridgway of the Mount Auburn M. E. Church spoke on the "Cure for Strikes," while Rev. E. H. Cherington of St. John's M. E. Church entitled his sermon, "The Teaching of the Strikes." Rev.

5. Commercial Gazette, April 1 to 26, 1886. |

No Haymarketfor Cincinnati

21

Ridgway argued that while strikes might

be legal, the striker had to consider his

family and the community at large too,

and added that it was certainly unlawful for

a man to interfere with others who

wanted to work. He issued a dire warning that

no successful strike had ever been

carried out in the world and that strikes ". . . al-

ways make occasion for outbreaks of

communists and revolutionists, who flaunt the

red flag and commit murder and pillage

private and public property." He recom-

mended the eight-hour law and

cooperation as a cure to the problem of strikes.

Rev. Cherington at St. John's said in

his sermon that he approved of labor organiza-

tions, but continued with a warning;

There is one thing that is suggestive of

impending danger; that is Communism and Social-

ism. The laboring men may not have their

rights, but they can never get them by using

dynamite, tearing up railroads and

burning bridges. You could hear men just from Castle

Garden talking about liberty, equality

of rights, freedom, &, when the best thing they de-

served was the cell in a jail. The

workingmen must crush out the communists in their midst,

who are bringing odium upon them.6

When all the Methodist ministers of the

city met a week later, they heard Rev.

John A. Storey argue that "the

laboring man of the present day [was] not as well off

as the laboring man of one hundred years

ago," and that capital, too, must follow

the Golden Rule and must be conducted in

the interest of labor as in the interest of

trade. The group then decided to have

representatives of the Knights of Labor and

the Chamber of Commerce address the

assembled ministers at separate meetings on

the problems of capital and labor at a

later date. Only five ministers voiced objec-

tions that the matter was outside their

purview, and the resolutions to extend the in-

vitations passed by a vote of 25-5.7

It would seem then, that at least the Methodist

contingent of the ministry in Cincinnati

was aware of the problems confronting the

workingmen of the city and would have

agreed with the press: unions, collective

bargaining, arbitration,

cooperation-Yes; strikes and violence-No.

The Catholic Archdiocese of Cincinnati

had already addressed itself to the ques-

tion openly and clearly four years

before. The Fourth Provincial Council of Cin-

cinnati had dealt with many matters when

it met in March 1882, but its statement

on capital and labor was most important:

A man's labor is his own. The strong arm

of the poor man and the skill of the mechanic is

as much his stock in trade as the gold

of the rich man, and each has a right, as he pleases, to

sell his labor at a fair price. Men also

have a right to band together and agree to sell their

labor at any fair price within the

limits of Christian justice, and so long as men act freely and

concede to others the same freedom they

claim for themselves, there is no sin in labor band-

ing together for self-protection. But

when men attempt to force others to work for a given

price, or by violence inflict injury,

bodily or temporal, they sin. If men are free to band to-

gether, and agree not to work for less

than a given price, so others are equally free to work

for less or more as they please. All men

have a right to sell their labor at such price as they

deem fair, and no man, nor Union, has a

right to force another to join a Union, or to work

for the price fixed upon by a Union.

Here is where Labor Unions are liable to fail, and in

which they cannot be sustained. If one

class of men is free to band together and agree not to

sell their labor under a given price, so

are others equally free not to join such Unions, and

also equally free to sell their labor at

such price as they may determine upon....

6. Enquirer, April 19, 1886.

7. Ibid., April 27, 1886.

22 OHIO HISTORY

On the other hand, capital must be

liberal towards labor, and share justly and generously

the joint profits which labor and

capital have produced.... Capital has no more right to un-

due reward than labor, nor should

capital be unduly protected at the expense of labor.

This message was read to the laity of

the Archdiocese in 1882 and was later given

formal approval by Pope Leo XIII on June

22, 1886.8

The Catholic Telegraph, the

archdiocesan newspaper, also reflected these moder-

ate views in the mid-1880's and came

down hard again and again on starvation

wages as the root cause of social unrest

and upheaval in the world of labor. It re-

minded the employer that he was obliged

to pay a 'just price' to his employees and,

while decrying the violence of the

southwestern strike by the Knights of Labor in

the spring of 1886, pointed out that the

workers had every right to protest and to

protect themselves against 'the rapacity

of monopolists.' The Catholic weekly also

warned that strikes made the public

aware of the revolutionary tactics of European

communists who had filtered into labor

organizations and that this exposure was

alienating public sympathy from the

worker's cause.9

Preparations for the demonstration for

the eight-hour day by local trade unions

began in earnest in April, and by the

third week of the month all seemed ready.

The order of march for the workingmen's

parade had been published and the pa-

rade route had been determined. Jumping

the gun, the furniture workers at

Brunswick-Balke-Collander, Rothchilds',

and Robert Mitchell furniture companies

went out on strike on April 26 and 28.

At its last meeting before the May 1 date,

the Trades Assembly devoted most of its

time to hearing speeches on the eight-hour

day. As the May date drew near, union

plans were not always followed and the la-

bor situation grew more confusing. In an

effort to forestall a shutdown, the em-

ployees of Crane and Breed Coffin

Company were presented with pledge slips that

committed them to work any number of

hours the company designated. Also the

yardmen on the Ohio and Mississippi

Railroad agreed to a twenty-five cent increase

in wages (thereby taking them out of the

ranks of potential strikers), and a mass

meeting of the carpenters declared for

the eight-hour day but demanded only eight

hours pay for it. Then on the eve of the

strike Procter & Gamble Company, candle

and soap manufacturers, offered their

men sixty hours wages for a fifty-five hour

week and this was accepted. The Master

Plumbers' Association offered a fifty-three

hour week to their journeymen at the old

wage of $3.50 per day at the same time.

Yet, despite these defections,

Workingmen's Hall was jammed for the planned

workers' meeting on April 30, and it was

obvious that the eight-hour strike was go-

ing to occur.10 The only question

seemed to be what form it would take and

whether, true to rumor, the local

Socialists would take over the movement and make

it their own.

Not waiting to see, the Times-Star came

out with an editorial attacking two lead-

ers of the eight-hour strike, William B.

Ogden and Dr. Otto Walster. After labeling

Ogden a Communist (which was true) and

Dr. Walster 'the intimate friend of Herr

8. John H. Lamott, History of the

Arch-Diocese of Cincinnati, 1821-1921 (New York, 1921), 219-220;

Henry J. Browne, The Catholic Church

and The Knights of Labor (Washington, D.C.. 1949), 81-82.

9. Sr. M. Stanislaus Connaughton, The

Editorial Opinion of the Catholic Telegraph of Cincinnati on

Contemporary Affairs and Politics,

1871-1921 (Washington, D.C., 1943),

173 174.

10. Enquirer. April 29, 30, May

1, 1886.

No Haymarket for Cincinnati

23

Most' (the German-born anarchist active

at the time in the United States), the edi-

torial warned:

It is a great mistake on the part of the

labor societies to permit Ogden and Walster to prance

in the forefront of their ranks at this

time. It can not but prejudice their cause. Work-

ingmen are fair-minded, law-abiding,

order-loving citizens. Communistic and Socialistic

blatherskites like Ogden and Walster,

who insinuate themselves into every labor movement,

are reckless agitators, who would

destroy where they can not build up, who would cultivate

disrespect for law, upset established

usage and disturb social order. They have no place in a

labor movement. Workingmen of this city

should give the cold shoulder to Ogden and Wal-

ster.11

Yet most of Cincinnati, unlike the

prominent Times-Star, sat back to watch and see

if violence would indeed enshroud the Queen

City.

May 1, the opening day of the general

strike, found the cigarmakers out of the

agitation since the unionized cigar

factories had accepted the eight-hour day and 20

percent wage increase demands. Many

other groups of workingmen still had out-

standing grievances with their

employers, however, and it seemed that some agita-

tion would surely take place. As

predicted, numerous strikes did occur that day-

the freight handlers decided to leave

their jobs, most of the furniture workers were

already out, and further strikes were

predicted-yet there was no violence. The En-

quirer caught the city's spirit of relief when it said:

The 1st of May, designated by a recent

enactment of the Ohio Legislature and the Knights of

Labor throughout the whole United States

as the day for the adoption of the eight-hour law,

has passed. Many Cincinnatians were

solicitous lest the revolution in working hours might

precipitate trouble between labor and

capital, but there seems to have been no cause for

alarm. Several strikes of greater or

less proportions occurred, but there appears to be no dis-

position on the part of anyone to create

a disturbance. The men seem satisfied to discuss the

questions at issue, and to abide by the

decision which shall finally be made after all sides

have been fully considered.12

May 1 had indeed passed without

incident-but May 2 was fated to be the day

when the movement began in earnest and

when Cincinnati's reaction to the strike

and to the Socialists who tried to make

it their own began to reveal itself. The pa-

rade planned for Sunday, May 2, in

support of the eight-hour day was only a partial

success, although it was reported that

there were 1,500 men in the parade. There

was no major trouble except for the fact

that somehow the Socialists had become

very influential in the ranks of the

parade committee and, as a result, the first flag at

the head of the parade was a crimson

banner inscribed with a call for the eight-hour

day. It was surrounded by one hundred

members of the English and German Rifle

Unions to protect it from being torn

from its mast by irritated workingmen-a clear

indication of what many Cincinnati

mechanics thought of the flag of revolution.

Reportedly many members of organizations

which were supposed to march

11. Cincinnati Times-Star, May 1,

1886.

12. Enquirer, May 2, 1886. The

Ohio eight-hour law read: "In all engagements to labor in any me-

chanical, manufacturing or mining

business, a day's work, when the contract is silent upon the subject, or

where there is no express contract,

shall consist of eight hours; and all agreements, contracts or engage-

ments in reference to such labor shall

be so construed." Revised Statutes, Section 4365. The law was ob-

viously very weak since it allowed the

employer and his employee to sign a contract designating any num-

ber of hours as the working day.

24 OHIO HISTORY

dropped out or refused to start when

they saw the red flag.13

It was noted that much more interest was

shown in the parade in the pre-

dominantly German

"over-the-Rhine" section of Vine Street than in other down-

town areas.14 While a list of

participating organizations might argue to a high de-

gree of German interest in the strike

and in its Socialistic overtones, two additional

facts must be noted. First, between May

1, when final plans were made for the pa-

rade, and May 2, when the units actually

moved up Vine Street, the number of units

dropped from thirty-two to only fifteen.

Those that decided not to march were the

following: German Cabinetmakers'

Benevolent Association, Cincinnati Turn-

gemeinde, Metal Workers' Union, West

Cincinnati Turner Society, Bavarian Ben-

evolent Association, Groetil Verein,

Swiss Maennerchor, House-painters' Union,

Herwegh Maennerchor, Workingmen's

Singing Society, Wood-carvers' Union,

Gambrinus Benevolent Association

(brewers), West Side Turnverein, German Mu-

tual Relief Association, Trunkmakers'

Union, Suabian Maennerchor, and Hodcar-

riers' Union. Since most of these were

German organizations, but not necessarily

Socialistic oriented, it becomes obvious

that a sizeable segment of organized Ger-

man life in Cincinnati decided against

participating in the demonstration in the last

twenty-four hours.

Second, the strongest and largest trade

unions in Cincinnati were not represented

in the parade at all. Absent were such

leading unions as Bricklayers' Union No. 1,

Carpenters and Joiners' Unions Nos. 1

and 2, Cigarmakers' Unions Nos. 4 and 30,

Carriagemakers' Union, Bakers' Union No.

1 (often called the German Bakers'

Union), Amalgamated Iron Workers, four

Knights of Labor assemblies of shoe-

makers, Safemakers' Union, one plumbers'

union, Typographical Union No. 3, and

Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers,

besides six other unions which refused to

participate at the last moment. On the

basis of these notable segments of Cincin-

nati trade unionism not taking part in

the demonstration, it would be hard to argue

for its mass support by organized labor

or by the German community as a whole.

After the parade on Sunday afternoon, an

"Eight-Hour Picnic" was held at the

Bellevue House at the top of Bellevue

Incline, concluding the days events. The

gathering was carefully watched over by

the Superintendent of Police, assisted by

twenty-five policemen. No trouble broke

out. At four o'clock, after selections by

the Herwegh Maennerchor, including

"Forward to the Battle," the speeches began.

The first speaker was William B. Ogden,

the Communist, who spoke on the red flag

as an emblem of the workingman and on

the justice of the eight-hour day. Ogden

was followed by Albert E. Parsons, the

Chicago anarchist, editor of the Alarm, who

was destined to give a more famous

oration in Haymarket Square two days later.

Standing on a beer table, the Windy City

editor argued for the eight-hour day as a

means of "making a consumer out of

the producer." He became "radical" only at

one point, when he warned that "...

if capital insisted on raising the black flag of

starvation-the workingman would raise

the red flag of revolution and liberty and

discharge the employers once and for

all."15

May 2 had also been marked by other

events which, while perhaps small in them-

selves, clearly indicated that the

general strike and the Socialist cause were not pass-

ing without challenge. At a meeting of

the carriagemakers these workers were in-

13. Enquirer, May 2, 3, 1886.

14. Ibid., May 2, 1886.

15. Ibid., May 3, 1886.

No Haymarketfor Cincinnati

25

formed that two firms had agreed to the

eight hours of work for ten hours of pay

formula, thus taking these workers out

of the strike. In church that morning the

members of the First Universalist Church

heard a sermon by their pastor, Rev. E. F.

Pember, entitled "Strikes, Their

Cause and Cure." Rev. Pember called for living by

the Golden Rule and praised the gains

made by the workingmen in the United

States and the Knights of Labor, but

absolutely refused to place all the blame for

the current agitation on the

capitalists, saying: "Those who claim greater things

from capital are sadly intemperate, and

they blame the employer for what should be

charged to themselves and the

saloon." Then addressing himself to the topics of

the Socialists and the parade scheduled

for that day, the minister raised his voice to

say:

Certainly it is a violation of this law

[the Golden Rule] when the red flag of Communism

waves over a mob-when there is danger to

life and property. If... the scenes in other cities

are to be repeated here, they must be

decried. The red flag should be torn down and

trampled upon .... Every wave of that

flag, every explosion of dynamite, but sends a deeper

wound into the workingman-but tightens

the bands on the working class.16

On Monday morning, May 3, the eight-hour

strike actually came to fruition. All

the furniture factories in the city were

closed, the carriage factory workers who had

not settled the day before went out on

strike, and many freight handlers left their

jobs. The freight handlers, however,

struck for an increase in wages, not a reduc-

tion of hours. The Cincinnati, Hamilton

and Dayton Railroad freight handlers be-

gan the agitation and persuaded their

counterparts on the Big Four, the Ohio and

Mississippi, the Cincinnati, Washington

and Baltimore, the Southern, and the Bee

Line railroads to join them.

Seventy-five laundry girls also met that day to organize

a union. They wanted better wages than

$1 per day for eleven to thirteen hours of

work. The general strike had begun, and

yet at this, its very moment of apparent

success, the Bricklayers' Union met and

took action which became quite common

among the trade unions during the next

few days. The bricklayers unanimously

passed a resolution saying:

Resolved, That we denounce the actions of all parties

participating in the so-called trades and

labor turnout on Sunday, May 2d, as an

outrage, not only on all labor organizations, but on

all true American citizens.

1. The day set for the general parade

was Saturday, May 1st; that day should have been

made the day for a grand jolification by

all sons of toil, and not the Sabbath day.

2. The carrying of a red flag at the

head of a procession that pretends to represent the la-

boring class is acting a lie. A red flag

does not mean honest labor, but money or blood, and

should not be tolerated in America.

The bricklayers of Cincinnati do not ask

for money only that which they earn by the sweat

of their brow; and the flag bearing the

stars and stripes is the only one that we recognize as

having any right to be unfurled in the

United States of America.17

By May 4 the strike was in full bloom

and it was reported that at least 12,000

workers were refusing to work. Workers'

meetings were being held throughout the

city, and a number of men paraded the

streets with music. At ten o'clock in the

16. Ibid.

17. Ibid., May 4, 1886.

26 OHIO HISTORY

morning two or three dozen striking

teamsters approached the men engaged in

making street improvements in the

downtown area and compelled them to quit

work by threatening them with violence

and bombarding some of them with stones.

The freight handlers working the depots

in the West End continued their strike, al-

though it was reported that the East End

depots were taking up the slack. Police

had been dispatched to all the railroad

depots, but no trouble occurred. Five hun-

dred coffin makers had also joined the

strike by this time and were taking steps to

organize into unions. The pressers and

trimmers were also out and considering

joining the Knights of Labor, although

many tailoring shops were still open. The

six hundred men of Hall's Safe and Lock

Company struck in the afternoon for eight

hours and a 10 percent raise. Four

hundred of their fellows from the Mosler Safe

Company joined them and demanded the

same terms. The newspapers reported

that thousands of Socialist circulars

were being distributed throughout the city

which read in part:

To revolutionize the affairs of to-day

is the true way and the only way to bring relief, genuine

and lasting relief, to the working

people!

Are you ready? Forward, then! We are

with you. Where is the coward that would draw

back? Form your battalions; to arms!

Have you not weapons enough? There are the arse-

nals of the counter-jumper militia,

stocked with military stores, repeating rifles and muni-

tions. Fling the police in the gutter,

the militia in the river! Drag the venal politicians and

corrupt judges from their seats; chase

the capitalist hyenas from the town, the priests from

the churches! . . Blow up the infamous

Legislature! Scourge the corruption of Congress

from the Capitol! . . . Why delay an

instant? Are you not hundred thousands-millions?

Who can withstand you, if you choose?

Into the street! Forward! Forward! Allons, en-

fants de la patrie! 18

Even with a number of men out on strike

and many marching the streets, there was

no violence other than the minor stone

throwing incident that morning. The circu-

lar of the Socialists was obviously

meeting with no response. Equally important,

the city fathers were remaining very

calm instead of overreacting to the situation.

Despite the peaceful attitudes and

actions of the Cincinnati strikers and the obvious

fact that the Socialists were being

openly repudiated by the very people who were

supposed to be their greatest

supporters, the anti-labor newspapers were beating the

anti-Socialist drums. The Commercial

Gazette very early in the strike ran a letter

from "M. W." on Socialism

which began by praising the "protests against the pre-

vailing injustices and unrighteous

inequalities of society .. ." but that these "de-

voted spirits" had used the wrong

means to overcome the evils. The letter ended by

quoting Bakounine [sic], the

Russian anarchist, condemning God and all authority

and quoting Reclus, another European

radical, renouncing the supernatural and all

dogma as suppressing freedom. It asked,

in conclusion:

Could egotism mount heights more sublime

or depravity fester in depths more purulent than

is portrayed in these selections from

the apostles of Nihilism and Socialism? They have

abolished God-or rather each man has

installed himself in his own heart as the Deity he

shall fall down and worship.19

The Times-Star was mounting even

more savage and imprudent attacks than

18. Ibid., May 5, 1886; Commercial

Gazette, May 5, 1886.

19. Ibid., May 3, 1886.

No Haymarket for Cincinnati

27

those of the Gazette. On May 3 it

damned the leaders of the labor movement who

would sacrifice the interests of the

workingmen "to either pernicious theories with

which their minds have been poisoned or

to their own selfish, demagogic purposes,"

and the next day it attacked the whole

idea of the eight-hour movement, con-

cluding:

But all intelligent workingmen will

see-as many of them do now-that there must be noth-

ing arbitrary in it. A universal

eight-hour rule is a barren ideality. The practical thing to

strive for, it would seem, is a

pay-by-the-hour rule.

The paper also editorialized against

"foreign" Socialists with great vehemence:

It ill becomes a man who has been in

this country only two or three years-not long enough

even to obtain a citizenship-to spend

his time in agitating socialistic doctrines and in yawp-

ing for more "Liberty and

Right." Such a man does not know American institutions, Amer-

ican culture and American civilization

.... This fellow, who never drew a breath of free air

till he struck the soil of the American

Republic, proposes to teach Americans how to con-

struct and run a free government. That

is a large task and we advise him to go a little slow.

He should first learn to use properly

the liberty which he is enjoying in this country and

should study the origin and history of a

government which vouchsafes to him the largest per-

sonal freedom. The American citizen of

whatever nationality wants the "stars and stripes"

at the head of his procession; the

fellow who rants the red flag would better move on to some

other country, this one is not large

enough for his pretensions.

When the news of the Haymarket Square

riot in Chicago reached Cincinnati on

May 5, the same newspaper argued with

"proof of the pudding" logic,

Anarchist devils who preach destruction

attempted last night in Chicago to practice what

they preach. The desperate business was

begun after A. R. Parsons and two other scoun-

drels had inflamed the minds of a great

crowd of imported thugs and criminals. Bombs

were thrown into the ranks of policemen.

Then came a fearful struggle, in which several of-

ficers were killed and many wounded.

Half a hundred raving anarchists were cut down by

the little group of brave officers.

There is further talk of the bomb and torch, but probably

rigorous repressive measures will send

the rioting wretches to their dens and restore order.

In the list of dead and wounded

anarchists we do not find the names of the rascally agitators

who are chiefly responsible for the

carnage of last night. This is a matter for regret. If these

abominable beasts had been made to bite

the dust, the record of bloody work would show

something accomplished for the good of

the country.

This was combined the next day with,

Anarchist whelps make their way into the

ranks of workingmen and become offensively

prominent whenever opportunity offers.

They have villainous designs. They aim to breed

disorder and precipitate a clash between

workmen and the authorities. Some of these beasts

are now prowling around Cincinnati,

intent upon instigating wild spirits among the strikers

to riotous demonstrations. One of these

rabid animals, who had come from the West, was

arrested yesterday by order of Chief

Moore. He had threatened bomb-throwing. This in-

cident is one of many that show the

urgent necessity of preparing for repressive and aggres-

sive measures.20

Among the German-language newspapers the

Volksfreund took a line similar to

the English-language papers. After an

initial brief silence, it urged its readers (in

20. Times-Star, May 3, 4, 5, 6,

1886.

28 OHIO

HISTORY

English so that no one could mistake its

stand): "Boycott the red flag! The Ameri-

can flag is the flag of our

country!" and condemned the anarchists who called for

murder and violence. The German paper

insisted that every honest worker should

help to "annihilate this band"

and the next day carried a long article quoting con-

demnations of the anarchists from all

over the country.21 Obviously, the severe re-

action of the daily presses and pulpits

in Cincinnati to the strikes and demonstra-

tions could give the local Socialists

little reason for comfort.

Wednesday, May 5, was tense. The

trouble-filled news from Chicago, Mil-

waukee, and St. Louis began to have an

effect, and the Cincinnati authorities pre-

pared to act even though no trouble was

occurring in the city and the workers

throughout the city were denouncing the

red flag and the Socialists in clear and

ringing tones. The only incidence of

possible violence occurred when about three

hundred railroad strikers marched to the

Little Miami yards to try to convince the

freight handlers there to join them.

They were met by a squad of fifty policemen

with Chief Arthur G. Moore himself in

charge. When three of the more vocal of

the strikers were arrested, the band of

strikers quickly dispersed.22

Yet the city authorities were worried,

and a private meeting was held between

Mayor Amor Smith and the four police

commissioners on May 5. At this meeting

it was decided to authorize the mayor to

swear in one thousand special policemen

and use the First Regiment and Second

Battery of militia if necessary. That the

trouble elsewhere lay behind these

decisions was evident from the mayor's procla-

mation:

Whereas, The agitation of the labor

question has reached this city; and

Whereas, In the cities of St. Louis,

Chicago and Milwaukee the want of prompt action on the

part of citizens to confer with each

other concerning such agitation has unfortunately re-

sulted in misunderstandings which have

led to bloodshed; and,

Whereas, It is the duty of all citizens

to discountenance all acts which tend to riotous pro-

ceedings and to render effective support

of the public officials, now, I, the undersigned,

Mayor of Cincinnati, do hereby call upon

all citizens. ... To meet at 8 o'clock this evening at

their respective precincts as designated

below, and there to organize Committees of Safety

for keeping the peace and protecting

property, and to assist the city officers in properly meet-

ing and disposing of the present

troubles....

Reflecting this new mood of fear of

possible violence, the Enquirer, while more tem-

perate than either of its two major

English-language rivals, commented,

It must gratify every good citizen to

observe that the organizations of real workingmen are

awakening to the danger which confronts

them in Communism and anarchy. Our local col-

umns reflect some sturdy resolutions

which embody the sentiments of honest workingmen

and denounce the red flag and all that

it signifies in words that burn....

The followers of the red flag have gone

too far for their own good. They have undertaken

to throw too many people under the

shadow of their banner. They have mistaken a differ-

ence of opinion between employers and

employees as to hours and wages for a demand for

their bloody arbitration. They have

forced themselves into a breach where there was no use

for them. They must find that they are

in reality nobody's allies.23

On May 6 the strike began to wane and

with it any remaining sympathy for the

21. Cincinnatier Volksfreund, May

6, 7, 1886.

22. Enquirer, May 6, 1886.

23. Ibid.

|

|

|

Socialists. The freight handlers, whose numbers constituted over one-half of all the strikers, accepted terms from their employers and went back to work. Instead of their original demands for a flat 25 cent raise per day for ten hours of work, they ac- cepted a ten cent increase, giving them $1.35 and $1.45 per day, and the trouble was over. Some other firms began to compromise on ten hours and 10 percent or nine hours and 20 percent, although many trades remained out. The most prominent of those still out were the bulk of the carriagemakers, the safeworkers, and the furni- ture workers. The day was also marked by another round of resolutions by various unions against violence in general and the Socialists and Communists in particular. As on the previous days, there was no notable trouble of any kind, other than a pro- test meeting of a minority of the railroad workers against the bond of $5,000 placed on the person of O. W. "Texas Jack" Stacey, their leader (and the "rabid animal from the West" referred to by the Times-Star), who had been arrested the day be- fore in the march on the Little Miami yards. All seemed serene, although some 10,000 men were still out on strike.24 Friday, May 7, was again quiet with various meetings being held throughout the city. These were characterized by the usual acceptance or rejection of terms from employers and by denunciations of the red flag and Socialism, but no trouble of any kind occurred. Despite this fact, that evening, after a conference of the mayor and the police commissioners, one of the commissioners was sent to Columbus to ask Governor Joseph Foraker for detachments of state militia. After a two-hour mid- night conference with the representative from Cincinnati, Governor Foraker called out the Third, Seventh, and Fourteenth regiments besides the Eighth Artillery Bat- tery and the Seintz Battery. They were ordered from their bases in Springfield and

24. Ibid., May 7, 1886; Commerical Gazette, May 7, 1886. |

30 OHIO

HISTORY

Columbus to Carthage, just north of

Cincinnati, and began to arrive on the after-

noon of May 8, about 1,400 strong.25

Why did the mayor and the police

commissioners call for troops at this time?

The city had been quiet for three days

and the Socialists had been roundly de-

nounced by most of the strikers. When

explaining why he called for the troops,

Mayor Smith said he had done so to

assure protection for every man who wanted to

go to work. This may have been an honest

statement on his part, but it brings up

the question as to whom he was

protecting them against. It was surely not the strik-

ers, who had not lifted a hand against

any man continuing to work since the pre-

vious Monday, and that had been but a

minor incident. Yet the city officials were

definitely afraid of possible violence.

Even the Enquirer, which to this point had

been very moderate in regard to the strike,

was now talking in terms of 30,000 men

being on strike in the city, even though

two days before it had set the number at

10,000 and its news columns had

mentioned no further significant walkouts since

then. It would appear that the officials

were unduly afraid of Socialist terrorism

and were perhaps incited by the fact

that Herr Most had been seen in the city that

evening-even though he was only changing

trains on his way to Chicago.26

That this fear of Socialist-inspired

violence was undoubtedly the reason can be

seen in the comments of the Times

Star, the only Cincinnati newspaper which spoke

openly and directly to the question as

to why the troops were needed:

The Police Commissioners have been

investigating the Socialists in Cincinnati. They find

that they have about 600 guns of all

kinds, of which 200 are improved Winchester repeating

rifles. The others are old army muskets

and shotguns.

These men are all foreigners, mostly

Germans, and they are well drilled. Not only that

[but] they were pining some time ago to

meet the United States troops, and begin the work of

destruction. As one of them said:

"We have the Prussian drill, and these tamn [sic] Ameri-

can soldiers can't come up to us."

These Socialists have the same kind of

bombs that were used in Chicago. This is given as

a fact known to the police, and with no

intention of unnecessarily exciting or alarming any-

one. These bombs are made in Cincinnati

and Covington and they have been made here

for years.

The bombs used by the Paris Commune were

made here in Cincinnati. This fact was

brought to light by the German

Government, which employed American spies to investigate

the matter.... These facts in regard to

the Socialists are well known and they explain the

present police and military precautions.27

Fear of Socialist violence is also

indicated by the fact that on Saturday evening,

May 8, a planned meeting of the

Socialists at Workingmen's Hall was flatly forbid-

den by the mayor, and police were on

hand to assure that the meeting did not take

place. The chief of police and

"every detective in the city" were in attendance, and

when a sickly young man edged his way

into the crowd and began distributing cir-

culars written in German, he was

immediately arrested. The chief also spoke to Dr.

Walster and gained assurances from him

that he would not speak at the meeting as

scheduled. The police then advised the

proprietor of the hall that he was not to let

the Socialists have a meeting in the

building.28

25. Enquirer, May 8, 1886.

26. Ibid.

27. Times-Star, May 8, 1886.

28. Enquirer, May 9, 1886.

No Haymarketfor Cincinnati 31

In the meantime, the Volksfreund, not

to be outdone by its English-language

counterparts, was doing its best to deny

any connection between anarchists and the

German-Americans. It argued that the

Germans had lived in the United States for a

generation and were loyal to the Stars

and Stripes, and that the lately-arrived an-

archists from Europe were giving them a

bad name. Anarchism, the paper claimed,

came from the sickly seedbed of the

German Empire and not from the hearts of the

German-Americans who had fought for

their country on many battlefields and

urged the government to send the

anarchists back where they came from.29

Sunday, May 9, was quiet. A week had passed.

The Third, Seventh, and

Fourteenth regiments with the two

Batteries attached to them were all quietly en-

camped at the Carthage Fair Grounds

north of the city. Five companies of the

Seventeenth were encamped at Burnet

Woods north of the city and the First, from

Cincinnati, was billeted at the Armory

downtown on Court Street. Thousands of

citizens took advantage of the nice

weather and went to the camps to see the guards-

men. The encampments at Carthage and

Burnet Woods were casual, festive, and

almost picnic-like. Religious services

were held for the militia at all three locations

in the morning.

Sunday was also quiet on the labor

front, although a number of meetings were

held and more denunciations of the red

flag were passed. The Brewers' Union now

joined the harnessmakers in explaining

that they did not know the red flag was at

the head of the parade the previous

Sunday or they would not have marched. The

situation regarding the strikes remained

the same with about 7,000 men still out on

strike. The most important occurrence

that day, and, perhaps, during the strike,

was the formation by some of the

strikers of a new central labor organization. It

was called the Central Labor Union and

was the direct forebearer of the present

Central Labor Council. At its first

meeting much disgust was expressed at the lack

of a willingness to compromise on the

part of the employers, and for the first time

formal protest was made against the

high-handed actions of the mayor. The Cen-

tral Labor Union pronounced:

Whereas, The Constitution of the United

States guarantees to all men the right to assemble

and discuss their grievances and demand

fair remuneration for labor performed; therefore

be it,

Resolved, That we condemn the action of

the Mayor and authorities in calling upon the

military throughout the State when no

act of violence has been committed.. ..30

May 10 and 11 continued quiet. A few

firms and their employees came to terms,

but most of the remaining strikers

stayed out. There was only minor, sporadic vio-

lence which was handled by the regular

police force. The extra police and militia

were not brought into play at all. The

carriagemakers, though, did pass resolutions

against the mayor and the governor for

the presence of the police and the militia

and demanded that both forces be

recalled.

On Tuesday, May 11, the strike virtually

came to an end. The remaining car-

riagemakers agreed to eight hours and 10

percent increases and the furniture work-

ers began to return to their jobs at

their old wage rates. A few thousand workers

still stayed out, but their numbers were

rapidly depleted over the next few days.31

29. Volksfreund, May 8, 1886.

30. Enquirer, May 10, 1886; Commercial

Gazette, May 10, 1886.

31. Enquirer, May 11, 12. 1886; Commercial

Gazette, May 12. 1886.

32

OHIO HISTORY

On May 12 delegates from six trade

unions visited Mayor Amor Smith to object

to the calling and continued presence of

the special police and the militia. Since

only a few trade unionists were on hand

for the meeting, the mayor suggested that

they meet the following day when more

men could be present. This was agreed to,

and an amiable meeting was held at the

mayor's office the following afternoon.

About one hundred representatives of the

trades were present. At this meeting the

mayor gave a long explanation for his

actions and shouldered the entire blame for

the calling of the special police and

the militia. He argued that the non-strikers had

a right to go to work and to continue

working unmolested and that in some early en-

counters, such as at the railroad yards,

some of the strikers showed a disposition to

violence. Therefore, he argued, he and

the other authorities could not have pre-

sumed other than that trouble might

occur. He also admitted that the violence at

Chicago, St. Louis, and Milwaukee, as

well as the presence of "foreigners" among

the strikers, had influenced their

thinking in asking for the militia. However plau-

sible his explanation, the entire

meeting was very friendly and ended with the hope

being expressed by all sides that the

difficulties still remaining could be speedily

cleared up.32

On this note the strike for the

eight-hour day in Cincinnati in May 1886 ended.

Within another week most of the workers

were back on the job, the special police

disbanded, and the militia returned

home. When all the strikers finally returned to

work by the following month, 2,095 had

gained a reduction of hours without a cor-

responding reduction in pay, and 10,568

had received an increase in pay with no re-

duction of hours. Thus a total of 12,653

workers made some gains from the strike,

although the eight-hour day at ten-hour

wages, the original object of the majority of

the strikers, was obtained in only a few

cases. Considering the fact that there were

approximately 18,000 men and women out

during the strike (about 20 percent of

the city's work force), two-thirds of

them made some improvement in their condi-

tion, although, of course, this would

have to be measured against the wages lost dur-

ing the strike itself.

The Cincinnati eight-hour strike of May

1886, then, brought forth some gains for

the workers involved, but was hardly the

exciting and essentially unsuccessful event

that is usually pictured.33 The

conservative, hard-working and non-violent work-

ingmen of an essentially conservative,

hard-working and non-violent city had acted

according to form and had made some

substantial gains. Trade unionism was se-

cure, violence had been held to a

minimum, and the Socialists had been clearly

repudiated. Cincinnati had experienced

no "Haymarket."

32. Enquirer, May 13, 14, 1886.

33. U.S., Bureau of Labor, Third

Annual Report. Strikes and Lockouts (1888), 468-483. A detailed

analysis of the report in regard to

Cincinnati reveals that the number of strikers in Cincinnati reached a

maximum of 17,737 on May 5, 1886, and

had declined to 8,483 by May 7. From this time onward the to-

tal generally dropped daily until by May

21 it stood at 2,668. This would indicate that there is no basis

for the figure of 32,000 strikers used

by John R. Commons, History of Labour in the United States (New

York, 1918-35), 11, 385, and repeated by

countless others.

Furthermore, as pointed out above, the

figure of 32,000 plus was used at a time of general fear and was

in direct contradiction to the figure of

10,000 used two days before with no sizeable body of strikers hav-

ing gone out in the interval. Also,

Marion C. Cahill's comments on the Cincinnati situation in Shorter

Hours: A Study of the Movement Since

the Civil War (New York, 1932),

157-159, are generally in-

accurate. While it is true, as he

states, that many of the best organized trades gave the movement the

cold shoulder, he is in error when he

states: (1) 32,000 workers paraded on May 1, (2) the police force was

doubled, (3) the governor sent two brigades

of infantry, (4) in only two cases was the eight-hour day

granted, and (5) nearly every trade

organization held meetings denouncing the mayor's request for

troops.

JAMES M. MORRIS

No Haymarketfor Cincinnati

As the news spread from Chicago of the

events of May 4, 1886, a new word came to

be emblazoned into the hearts and minds

of the American people. That word-

connoting fear, revolution, anarchism,

and terror-was "Haymarket." Every man

reading the newspapers or talking with

his friends and neighbors of the events of

that day could not but be aware of the

"fact" that the anarchists who had wormed

their way into the bloodstream of

American life had finally let loose their poison.

Innocent victims had paid the price.

Who could tell where the vile contagion of

revolution and death might break out

again? Would it be in the East, in Boston or

Providence, or would it be in another

industrial midwestern city, such as Cleveland,

Cincinnati, or St. Louis? Which city

would next be pulled into the fiery cauldron of

revolution and death? Such fears may

have been groundless, but they persisted

nonetheless, aided by the newspapers

across the land which were filling their col-

umns with inflammatory news from

Chicago and other cities for days on end. The

hard facts of what had actually

happened were usually obscured or deliberately ig-

nored.

The events scheduled for Chicago's

Haymarket affair had been arranged long be-

fore May 4, and bloodshed and violence

had not been anticipated. The original in-

tention of the organizers was to call a

general strike to force acceptance of the eight-

hour day, an idea neither new nor

radical in the American labor movement at this

time. The plan for a nationwide general

strike had come from the moderate Feder-

ation of Organized Trades and Labor

Unions. This national organization of trade

unions, formed in 1881, had voted at

its 1884 convention to submit to all labor or-

ganizations the idea of a general

strike for the eight-hour day to take place on May

1, 1886. From this beginning the

movement grew, especially among the trade

unions, although many members of the

rival Knights of Labor also supported the

idea.1

In Chicago the strikers and the

strikebreakers, brought in to work in their place at

the McCormick Harvester plant, first

clashed on May 3 after two days of com-

parative quiet. The police intervened,

and in the melee that followed four persons

were killed. The local

radical-anarchist members of the Black International (very

1. For a scholarly description of the

events of Haymarket, see Henry David, The History of the Hay-

market Affair: A Study in the American

Social-Revolutionary and Labor Movements (New York, 1936), es-

pecially pp. 162-167, 182-205.

Mr. Morris is Associate Professor of

History at The Christopher Newport College of the College of

William and Mary in Virginia.

(614) 297-2300