Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

DONALD J. RATCLIFFE

Politics in Jacksonian Ohio:

Reflections on the

Ethnocultural Interpretation

Who voted for the two great political

parties in Jacksonian Ohio? Those

historians who have asked this question

have usually given two sorts of

answers. Some have seen the popular

basis for the party division in

essentially socioeconomic terms.

Occasionally they have detected a class

conflict between rich and poor, but more

commonly they have followed

Frederick Jackson Turner in seeing the

cleavage in regional terms: the

more isolated back-country and upland

(or "butternut") districts are

considered the bedrock of Democratic

support, while the more commer-

cialized, river-valley areas are seen as

the center of Whig strength.1 The

other answer stresses the importance of

ethnic influences: settlers from New

England were Whig, while those from

Pennsylvania and the South joined

with foreign immigrants in voting for

the Democratic party. Though few

historians have stressed the socioeconomic

interpretation to the exclusion

of the ethnic, some historians and

political scientists have seen ethnic

factors as the exclusive determinants of

voting behavior; and this latter

view has recently gained new

respectability from the application of more

sophisticated statistical techniques to

this historical problem. In almost

every state and county the result of

such "cliometric" analysis has been the

same: the socioeconomic interpretation

has no evidential basis, the party

division can be understood only in

"ethnocultural" terms.2

Mr. Ratcliffe is Senior Lecturer in

Modern History, University of Durham, England.

1. Frederick J. Turner, The United States, 1830-1850 (New York.

1935). 29, 303. 307.

Typical older works in this tradition

include Edgar A. Holt, Party Politics in Ohio, 1840-1850

(Columbus, 1931); Harold E. Davis,

"The Economic Basis of Ohio Politics, 1820-1840," Ohio

State Archaeological and Historical

Quarterly, XLVII (1938), 288-89; Francis

P. Weisen-

burger. The Passing of the Frontier, 1825-1850 (Columbus, 1941); and even Walter D.

Burnham, Presidential Ballots,

1836-1892 (Baltimore, 1955), 7-9, 11-13.

2. The word "ethnocultural"

embraces the meanings usually associated with the adjectives

ethnic, religious and cultural. Similar

emphasis on the origins of the voters may be found in

works as old as George M. Gadsby,

"Political Influence of Ohio Pioneers." Ohio Archaeologi-

cal and Historical Publications, XVII (1908),

193-96, as well as in more recent political studies

like Thomas A. Flinn, "Continuity

and Change in Ohio Politics," The Journal of Politics,

XXIV (1962), 524-27.

6 OHIO HISTORY

This new ethnocultural interpretation

has arisen from the praiseworthy

effort of historians to burrow beneath

the self-justificatory statements of

political leaders and to find out what

politics meant for the humble voter.

The aim has been to escape from the view

of events expressed by the

articulate and educated people of the

past, who commonly came from the

more affluent strata of society, and to

discover more about the mass of men

who left no record besides the aggregate

results of their behavior at the

polls. Historians like Samuel P. Hays

and Lee Benson have argued that

careful analysis of voting returns can

give a greater precision to our

understanding of political history and

help us uncover the social basis of

political behavior thus revealing the

experiences, the conditions of life,

and the cultural values and assumptions

which made ordinary men behave

as they did in elections.3

The most impressive work of the

ethnocultural school has been con-

cerned with the late nineteenth century.

Paul Kleppner and Richard Jensen

have shown that elections in the Midwest

in those years saw voters lining

up primarily according to their ethnic

and religious affiliations. The

Republicans drew their strongest support

from "pietistic" or evangelical

Protestants (including many Protestant

immigrants) who wished govern-

ments to safeguard the moral order

against alien and Catholic intrusions;

the Democrats received their staunchest

backing from ritualistic or "anti-

pietistic" Protestants and

Catholics, both of whom sought to protect their

institutions and practices by preventing

government interference. This

"cross of culture" (to use

Kleppner's phrase) was often profoundly affected

by the business cycle, but even after

the realignment wrought by the

depression of the 1890s, cultural

conflicts continued to play an important

political role in various states and localities.

The importance of such

ethnocultural divisions in the party

politics of the second half of the

nineteenth century has been ascribed by

Kleppner to the crisis of the 1850s,

when a massive influx of Catholic

immigrants from Germany and Ireland

provoked a Know-Nothing crusade to

preserve the nation's cultural ho-

mogeneity, Protestant character and

republican institutions. The resulting

heightened awareness of cultural

identity deeply influenced the political

realignment of the 1850s, and made the

threatened groups rally behind the

appropriate political party.4

3. Lee Benson, The Concept of

Jacksonian Democracy: New York As a Test Case

(Princeton, 1961); Samuel P.

Hays,"The Social Analysis of American Political History, 1880-

1920," Political Science

Quarterly, LXXX (1965), 373-94. The main works which have

resulted from this "new"

approach are well summarized by Samuel T. McSeveney, "Ethnic

Groups, Ethnic Conflicts, and Recent

Quantitative Research in American Political History,"

The International Migration Review, VII (1973), 14-23.

4. Paul Kleppner, The Cross of

Culture: Social Analysis of Midwestern Politics, 1850-1900

(New York, 1970); Richard J. Jensen, The

Winning of the Midwest: Social and Political

Politics in Jacksonian Ohio 7

Ethnocultural historians have also

argued, however, that such ethnic

and religious influences were of primary

importance in electoral behavior

even before 1850. Lee Benson himself

made a path-breaking contribution

with reference to the so-called Age of

Jackson: he acutely criticised much of

the evidence that earlier historians had

used to sustain an economic in-

terpretation of Jacksonian politics in

the state of New York, and he argued

instead in favor of an interpretation

which ranged Puritans, natives, and

new British immigrants against

non-Puritans and new non-British immi-

grants. Younger historians soon

sustained and refined this line of interpre-

tation. In particular, Ronald P.

Formisano has produced evidence of the

importance of ethnocultural factors in

Michigan politics between 1837 and

1852, and has argued in favor of seeing

the Jacksonian electorate as made

up of a series of "political

cultures": according to Formisano, these

"antagonistic . .. political

subcultures" among the voters perceived

political issues in symbolic terms which

related to the moral values of each

group. Thus each party developed a distinctive

political character based

upon these perceptions, and that

character had a direct impact upon its

success as a political party.5 One

corollary of such an interpretation has

been the belief that most voters were

influenced mainly by their own

immediate social and cultural

experiences, and scarcely at all by the

practical issues debated by the

politicians. This Formisano sees as generally

true of all "mass party

systems" marked by "self-conscious party loyalties";

only in a "pre-party polity"

such as existed before the 1830s were electoral

cleavages "oriented to more

immediate issue conflicts."6

Stephen C. Fox has recently used this

line of interpretation to explain

voting behavior in Jacksonian Ohio. Fox

uses the election returns for 1848

and the manuscript returns of the 1850

United States Census to demon-

strate that electoral cleavages in Ohio

followed the same patterns as those

discerned by Benson and Formisano in New

York and Michigan. Further-

more, he makes

"anti-partyism," or the distrust felt by many evangelicals

Conflict, 1888-1896 (Chicago, 1971); and, for Connecticut, New York and New

Jersey,

Samuel T. McSeveney, The Politics of

Depression: Political Behavior in the Northeast, 1893-

1896 (New York, 1972). For the 1850s, see Michael F. Holt, Forging

A Majority: The

Formation of the Republican Party in

Pittsburgh, 1848-1860 (Yale, 1969) and

Ronald P.

Formisano, The Birth of Mass

Political Parties: Michigan, 1827-1861 (Princeton, 1971), 195-

331.

5. Benson, Concept of Jacksonian

Democracy, esp. 123-328; Formisano, Birth of Mass

Political Parties, 1-194. See also William G. Shade, "Pennsylvania

Politics in the Jacksonian

Period: A Case Study, Northampton

County, 1824-1844," Pennsylvania History, XXXIX

(1972), 313-33; and idem. Banks or No

Banks: The Money Issue in Western Politics, 1832-

1865 (Detroit. 1972), esp. 17-19.

6. Ronald P. Formisano, "Toward A

Reorientation of Jacksonian Politics: A Review of

the Literature, 1959-1975," Journal

of American History, LXIII (1976), 58.

8 OHIO

HISTORY

for the new techniques of party

management being developed by the

Jacksonian Democrats, even more central

to the party division than did

Formisano, who first drew attention to

its importance in this period.7 More

recently, Fox has criticised in the

pages of this journal two recent works (by

Roger Sharp and myself) which had in

common an emphasis upon

economic experiences as influences on voting

behavior in Jacksonian Ohio:

Fox dismisses this interpretation, and

damns both works for their metho-

dological weaknesses and their devotion

to narrow economic

determinism.8 If he is right,

then there can be no argument against the

establishment of an ethnocultural

interpretation of Jacksonian politics in

Ohio to which, indeed, some historians

are already beginning to pay lip-

service.

However, the work of the

"ethnoculturalists" has its difficulties, as

notably James E. Wright and Richard L.

McCormick have shrewdly

argued. Among other things, McCormick

points out that the "ethnocultu-

ralists" cannot explain how

government policies are determined, since they

create a huge gap between elected

officials and the people who elected

them.10 Furthermore, their

studies concentrate on communities dominated

by distinctive ethnic or religious

groups, and often ignore the many rural,

7. Stephen C. Fox, "The Group Bases

of Ohio Political Behavior, 1803-1848." (Ph.D.

dissertation, University of Cincinnati,

1973); R.P. Formisano. "Political Character, Antipar-

tyism, and the Second Party

System," American Quarterly, XXI (1969), 683-709.

8. Stephen C. Fox, "Politicians,

Issues, and Voter Preference in Jacksonian Ohio: A

Critique of an Interpretation," Ohio

History, LXXXVI (1977), 155-70. The works criticized

are James Roger Sharp, The

Jacksonians versus the Banks; Politics in the States After the

Panic of 1837 (New York and London, 1970), and Donald J. Ratcliffe,

"The Role of Voters

and Issues in Party Formation: Ohio,

1824," Journal of American History, LIX (1973), 847-

870. The present article is not intended

as a reply to Fox's critique, except on points of fact and

interpretation relevant to the argument

presented here. In general, that critique is based on a

misreading of my earlier article so

blatant that I am willing to allow our differences to be

adjudicated by those who have read both

pieces. They can decide, for example, whether an

article which emphasized the role of

moralistic antislavery sentiment in the Presidential

election of 1824 can fairly be described

as devoted to the proposition that men are motivated

primarily by greed: or whether there is

a logical contradition in arguing both that lines of party

cleavage were initially dictated by the

voters rather than the politicians in the election of 1824,

and that politicians played a decisive

role in stimulating interest and participation, especially

during the subsequent period of

extension and build-up (1826-28). Cf. Fox, article, 156.

163-68. For an alternative discussion of

my earlier article, see Bernard Sternsher, Consensus,

Conflict and American Historians (Bloomington, Ind., and London, 1975), 184-86, 194-98,

202.

9. For example, Jed Dannenbaum's study

of "Immigrants and Temperance: A Study of

Ethnocultural Conflict in Cincinnati,

Ohio, 1845-1860," Ohio History, LXXXVII (Spring

1978), produces evidence which implies

that ethnocultural conflicts had been less important

before the crisis of the early 1850s,

but then expresses his faith that they had, in fact, previously

been the major determinants of party

identity, as Benson had said. See ibid, 130, 139.

10. James E. Wright, "The

Ethnocultural Model of Voting: A Behavioral and Historical

Critique." Allen G. Bogue, ed., Emerging

Theoretical Models in Social and Political History

(Beverly Hills and London, 1973), 35-56;

Richard L. McCormick, "Ethno-Cultural

Interpretations of Nineteenth-Century

American Voting Behavior," Political Science

Politics in Jacksonian Ohio

9

native-American voters and the many who

possessed no religious affilia-

tion. When a rural community made up

overwhelmingly of native voters

has been examined, the result has been

to play down the significance of

ethnocultural conflicts, even in the

1850s.11

This essay is not primarily designed to

criticize the ethnocultural

interpretation as a whole. Indeed, it is

based on the assumption that

ethnocultural factors did largely

determine the character of the parties after

1852.12 But it will argue that an ethnocultural interpretation,

pure and

simple, which rejects completely the

role of economic factors, cannot work

in the specific case of Jacksonian Ohio;

Michigan cannot be extrapolated

to the Buckeye State. The basic argument

is, briefly, that since the major

influence on Jacksonian voting behavior

was party loyalty, the period

when loyalties were first formed is of

particular significance; and ethnicity

was only one of a number of factors

operating at that critical period. The

voting pattern established then was

therefore a somewhat complicated one,

but it was one which modified in time as

a result of various pressures; and,

of those pressures, economic issues and

socioeconomic character were at

least as important, for a time, as

ethnocultural influences. The economic

factors that can still be detected,

however, took the form not of socioeco-

nomic class interests or

antagonisms but of communal responses to the

varying economic experiences undergone

by the different regions of Ohio.

The Force of Party Loyalty

The most obvious feature of electoral

behavior in Jacksonian Ohio was

its extraordinary stability. In election

after election, the same constituen-

cies gave majorities of roughly the same

proportion to the same party. Any

map showing the counties won by each

party in a Presidential election after

1828 shows remarkable similarity to any

other such map; and when

deviations occur, as they regularly did

in state elections held in years when

there were no Congressional elections,

they were the result more of a

falling-off in the vote of one party

(usually the anti-Jacksonians) than of a

transfer of allegiance from one main

party to another. This stability is most

Quarterly, LXXXIX (1974), 351-77; Robert Kelley, "Ideology

and Political Culture from

Jefferson to Nixon," American

Historical Review, LXXXII (1977), 531-62, impressively

attempts to interpret the history of

American national politics and governmental policies in

ethnocultural terms, but in the end

fails to satisfy both "ethnoculturalists" and more tradi-

tional historians. See the comments, ibid.,

563-82, especially those of R. P. Formisano.

11. See, for example, Eric J. Cardinal,

"Antislavery Sentiment and Political Transforma-

tion in the 1850s: Portage County,

Ohio," The Old Northwest, I (1975), 223-38.

12. Melvyn Hammarberg, The Indiana

Voter: The Historical Dynamics of Party Alle-

giance During the 1870s (Chicago and London. 1977), effectively qualifies the

ethnocultural

interpretation for the post-civil war

period by applying the most sophisticated statistical

analysis to evidence of individual voting

behavior in Indiana.

10 OHIO

HISTORY

surprising in view of the rapid economic

development experienced by most

of Ohio's counties in this period, which

meant that their interests and even

outlook changed without any major effect

on their political behavior. The

best explanation of this phenomenon, as

many historians have recognized,

lies in the extremely strong loyalties

which voters contracted towards the

major parties. At each election most of

them tended to vote for the party

they had voted for on previous

occasions, and these loyalties were

commonly transmitted from generation to

generation.13 As E. D. Mans-

field wrote after the Presidential

election of 1876, "Anyone can see, by

examining the votes of 1828, how little

the strength of the parties has

changed since. The truth is that

politics, like religion, descend from father

to son, with little variation."14

The stability created by persistent

party loyalties among the voters has

some important logical consequences for

those who would discover the

significance of the party division.

Suppose, for example, that someone tried

to analyse the influences which operated

on voters in the elections of 1844

or 1848: could they be sure that the

influences they deduced from the

characteristics of the voters actually

operated in that election? For might

not those influences be ones which were

important at some earlier period,

but which by the 1840s had ceased to be

of immediate significance and

owed their continuing force to

persisting party loyalties? Were ethnocultu-

ral factors important all the time, or,

as some "ethnoculturalists" have

suggested, only at the period when party

loyalties were formed?15 For

similar reasons, it is a mistake to assume

that any one election provides a

means for analysing the pattern of

loyalties which marked a "stable phase"

of party politics like that of

1836-1848.16 As most political historians now

13. The importance of party loyalty in

voting behavior throughout much of American

history is implicit, if not explicit, in

the writings collected in Jerome M. Chubb and Howard

W. Allen, eds., Electoral Change and

Stability in American Political History (New York and

London, 1971), and Joel H. Silbey and

Samuel T. McSeveney. eds., Voters, Parties and

Elections: Quantitative Essays in

American Popular Voting (Lexington,

Mass., 1972). For

acknowledgement of the role of party

loyalty in the Jacksonian period, see, inter alia, Charles

G. Sellers, Jr., "The Equilibrium

Cycle in Two-Party Politics," Public Opinion Quarterly,

XXIX (1965), 19-34, 36; Formisano, Birth

of Mass Political Parties, 21-27, 322; Fox,

dissertation, 182,405-10.

14. Edward D. Manfield, Personal

Memories, Social, Political and Literary, 1803-1845

(Cincinnati, 1879), 235.

15. Silbey and McSeveney, Voters,

Parties, and Elections, 3.

16. For example, the Presidential

election of 1844 in New York cannot be extrapolated

with safety to earlier Jacksonian

elections, especially since the controversy over Catholic

schools in New York during that year

caused a heightening of nativist feeling which could well

have transformed what had previously

been a relatively minor influence on voting behavior

into an obvious major influence. Benson,

Concept of Jacksonian Democracy, 123-328. esp.

117-19, 187-91.

Politics in Jacksonian Ohio 11

recognize, we need to study every

election and to disentangle the long-term

influences like party loyalty from the

immediate, short-term pressures.

Such a distinction would also help to

explain why particular ethnocultu-

ral groups tended to support one party

rather than another. "Ethnocultu-

ralists" usually explain such

behavior by analysing the group's cultural

attitudes and then demonstrating that

the views of one party were much

more congenial to those holding such

attitudes. But is it not possible that

the party in question held congenial

views because it had long enjoyed the

support, and been subject to the

pressure, of that particular ethnocultural

group? The Quakers and the

"pietist" sects may have been attracted to the

Whig side because the Whigs had a sense

of mission and holiness; but it

might be more accurate to say that the

Whig party developed a heightened

sense of moral purpose because it grew

out of a political formation which

had always had the support of Quakers

and "pietists." Similarly, to decide

whether Irish Catholics voted Democrat

because they were Irish or because

they were Catholic, it is useful to

examine not only the statistical correla-

tions among the characteristics

involved, but also the circumstances which

led Irishmen and Catholics into a

particular party.17 It is also worth

remembering that groups of voters may

have joined a party initially for

reasons which had little to do with

group membership, but their group

characteristics may have become of

extraordinary significance for the

party's subsequent development. The

electoral analyst ought to look more

closely at the historical circumstances

which brought the constituent

groups into each party; and he cannot do

that by generalizing across the

voting behavior of the years 1836-1852

on the basis of figures derived from

the 1850 census.l8

Thus it is of some importance to

identify when the mass parties of the

Jackson era first attracted their

popular support. The "ethnoculturalists"

frequently assert that political parties

became "emotionally significant

groups" in the 1830s, yet they have

offered little evidence to support that

claim; indeed, they seem almost

unnecessarily committed to the notion that

17. Cf. Fox. dissertation, 215, 254,

294, 299, 323, 347-50.

18. Of the

"ethnoculturalists," Formisano has most satisfactorily analysed the process

of

party formation in the Jackson period.

In Michigan national partydivisionswereformed only

as the territory entered upon statehood,

and that process was marked by a conflict over alien

suffrage which made ethnocultural

factors particularly potent. However, one wonders

whether more emphasis should not be put

on loyalties established earlier by some voters,

especially in view of the emphasis

Formisano places on the polarising effect of the Antimason-

ic political campaigns; and, indeed, the

fact that the issue of alien suffrage divided the

Democrats in 1835 suggests that the

party had been formed earlier, possibly under the

influence of non-ethnocultural factors.

Ronald P. Formisano, "A Case Study of Party

Formation: Michigan, 1835," Mid-America, L (1968), 83-107, and Birth of Mass Political

Parties. 3-137, esp. 60-67.

12 OHIO

HISTORY

party formation could not have occurred

before about 1834.19 Admittedly,

there was a period of considerable

turmoil in 1834 and 1835 from which a

stable party division emerged, yet the

"ethnoculturalists" never seem to

consider seriously whether the division

which emerged repeated the

patterns of division which had expressed

themselves in 1828. Indeed, it may

be that the strongest evidence that party

loyalties had been established

before 1834 lies in the resilience with

which the Jackson party, in particular,

survived the storms of dissension and

schism aroused by Jackson's Bank

War. In fact, many observers have seen

the beginnings of a stable party

division in Ohio in the Presidential

election of 1828, while some, including

Dr. Fox, have seen that the

"ultimate party alignments" of the 1830s and

1840s were "roughly" predicted

by the election of 1824.20

A strong case can, indeed, be made for

claiming that the campaign of

1824 is the proper starting-date. In

that election, the old Federalist party

failed to run a candidate for the

Presidency, while the dominant Republi-

can party could not agree upon a nominee

to succeed President Monroe. In

Ohio politicians formed completely new

alignments, and organized cam-

paigns on behalf of three of the major

candidates Henry Clay, Andrew

Jackson, and John Quincy Adams. The

voters appear to have identified

each group clearly, as was shown by the

remarkably low level of ticket-

splitting.21 Indeed, the

sudden appearance of ticket voting in this election is

well revealed by the

"pollbook" for one township in northern Ohio. Here

the tellers began by assuming that there

were forty-eight individual

candidates for Ohio's sixteen places in

the electoral college, and so they

kept a tally of votes for each

individual electoral candidate. After six or

seven ballots had been counted, all of

them straight party votes, the tellers

began to record only one vote for each

ticket, under the first name on the

ticket. Not one of the fifty-five voters

offered a split ticket, and all the

electors on each ticket received the

same number of votes.22

Subsequently the politicians appear,

from their private correspondence

and newspaper writings, to have assumed

that the voters had contracted

some sort of emotional commitment of the

groupings created in 1824. After

19. Fox, dissertation, 345, 410, 432-33;

Formisano, Birth of Mass Political Parties. 3-4.

Benson sees the voting patterns of the

next two decades as crystalizing in New York in 1832.

two years before formal party

organization was achieved. Benson, Concept of Jacksonian

Democracy, 62.

20. Mansfield, Personal Memories, 235;

Richard P. McCormick, The Second American

Party System: Party Formation in the

Jacksonian Era (Chapel Hill, 1966),

265; Fox,

dissertation, 427.

21. Harry R. Stevens. The Early

Jackson Party in Ohio (Durham, N.C., 1955). For the

range of votes each ticket received

through the state as a whole, see Columbus Gazette,

November 18, 1824.

22. Pollbooks for Sandusky township,

Huron County, 1815-1824, Vertical File Material,

Ohio Historical Society.

"Pollbook" is an inaccurate description since voting was not done

viva voce in Ohio, and the preference of individual voters cannot

be traced.

Politics in Jacksonian Ohio 13

the House election of 1825, when the

Clay and Adams forces combined to

make the latter President, the

Jacksonians maintained their opposition

though not reviving their organization

until 1826. They then focused their

attention upon the Congressional

elections in those districts of eastern

Ohio which had voted for Jackson in 1824

but whose Congressmen had

supported Clay in 1824 and voted for

Adams in the House election; in some

of these counties the politicians

succeeded in persuading the electorate that

a commitment to Jackson for President

meant a vote for a Jacksonian

Congressman, but their failure to pull

out the vote in one or two counties

prevented their success in 1826.

However, the Adams men recognized that

the established popularity of Jackson in

these districts ensured that three

loyal and talented Adams-Clay

Congressmen were "certainly" going to be

defeated in 1828-as, indeed, they were.23

Similarly, the Adams and Clay

organizations of 1824 withered away

after the election, in this case partly

because the leaders in Ohio believed

that the alliance of their principals

was satisfactory to the majority of Ohio

voters, as, indeed, the Congressional

elections of 1826 suggested. By 1827,

however, the administration party was

developing its organization and

reminding voters that the Adams-Clay

administration represented the kind

of economic policy and moral symbol

desired by most Ohioans in 1824.

Recognizing the formidable threat

offered by the Jacksonians, the Adams

men endeavored to secure victory in 1828

by thorough party organization

in that area of the state-the Western

Reserve-which in the 1824

Presidential election had been most

hostile to Jacksonism.24 In fact, more

evidence than can be presented here

exists to confirm that by 1828 many

voters identified themselves

self-consciously with well-advertised party

labels which they associated with

"an ongoing organization, symbols, and

traditions," in so far as any

traditions could be said to be established after

only four years.25

But do the voting returns for this and

subsequent elections confirm that

the nascent parties in Ohio had by this

time acquired a stable body of loyal

identifiers who voted for them

regularly? Table 1 reveals how far the

23. Charles Hammond to J.C. Wright,

Columbus, December 16, 1827, Charles Hammond

Papers, Ohio Historical Society. For the

development of the Jackson party between 1825 and

1828, see the Larwill Family Papers,

Ohio Historical Society, and idem, Western Historical

Manuscript Collections, University of

Missouri. An interesting analysis of the progress of

organization in each congressional

district may be found in the Washington, D.C., United

Slates Telegraph, July

19, 1828, reprinted in the St. Clairsville Gazette, August 2, 1828. See

also Weisenburger, Passing of the

Frontier, 218-36, and Homer J. Webster, "History of the

Democratic Party Organization in the

Northwest, 1820-1840," Ohio Archaeological and

Historical Quarterly, XXIV (1915), 6-34, though the latter is not entirely

reliable.

24. For the organizational efforts of

the Adams men, see, in particular, the Charles

Hammond Papers. Ohio Historical Society,

and the Peter Hitchcock Family Papers, Western

Reserve Historical Society, as well as

the party press.

25. Cf. Formisano, "Toward a

Reorientation of Jacksonian Politics," 58.

14 OHIO

HISTORY

distribution

of the vote (by counties) of the Jacksonian Democratic party in

each

Presidential election between 1828 and 1840 correlates with the

distribution

of its vote in preceding and succeeding elections.26 Clearly

there

was a very high degree of party regularity in Ohio throughout these

years;27

and the stable pattern of party loyalty dates back not merely to the

1820s

but even to the Presidential election of 1824. This last conclusion is

based

on the positive correlation of .759 between the elections of 1824 and

1828,

which seems surprisingly high in view of the fact that the number of

people

voting in 1828 increased by more than two-and-one-half fold over

1824,

and Jackson won far more counties than he had in the earlier

TABLE 1

Interyear Correlations of Democratic Percentage Strength

of Counties in Presidential Elections, 1824-1844

1824 1828

1832 1836 1840

1828 .759

1832 .666 .923

1836 .510 .763 .889

1840 .426 .744 .818 .888

1844 .421 .705 .828 .875

.970

election;

however, it seems clear that, despite Jackson's considerable gains

in

1828, the degree of support he won in that year in most counties was

primarily

determined by the amount of support he had inherited from the

campaign

of 1824.28 Thus, if the parties of the second party system began to

26.

All correlations (with one exception) used in this paper are Pearson

product-moment

coefficients

of correlation, and are significant at the .001 level. Particular problems are

faced in

drawing

up a table of this kind because of the frequent boundary changes and the

creation of

new

counties in Ohio, and different researchers will get marginally different

results according

to

how they handle the problem. I have used Randolph C. Downes, The Evolution

of Ohio

County Boundaries, reprint ed.

(Columbus, 1970), to help me distinguish the major changes

and

have followed different strategies as seemed most appropriate in each case, but

I have

taken

great care not to correlate the returns of counties possessing the same name

but covering

markedly

different areas of land.

27.

When Formisano applied this test to successive Presidential elections in

Michigan, he

discovered

a positive correlation of between .622 and .858, which he considered suggested

"the

high

stability" of party loyalty during those years. Formisano, Birth of

Mass Political Parties,

24-25.

28.

If we calculate the coefficient of determination, then it appears that 57% of

the

variations

in the Jackson vote from county to county in 1828 might be explained by the

variations

in the vote inherited from 1824. See also Ratcliffe, "Voters and

Issues," 866. I am

grateful

to The Journal of American History for allowing me to reproduce, in this

and the

following

section, material originally published in that journal.

Politics in Jacksonian Ohio 15

acquire bodies of identifiers and became

"emotionally significant reference

groups" as early as the election of

1824, then we must make certain that we

correctly identify the factors which

influenced that critical, initial cleavage

which so determined the future character

of the party division.

Party Formation in the 1820s

So how important were ethnocultural

factors in determining the voting

patterns in those critical first

elections of 1824 and 1828? To date no

"ethnoculturalist" has devoted

much attention to this question, but clearly

Dr. Fox holds that the factors at work

in these elections were much the

same as those he has discerned in the

elections of the 1830s and 1840s. He

rejects the argument that the perception

of economic interest played any

role in drawing voters to one side or

another, and insists that the basic

conflict was of essentially moral

dimensions. This conflict had its roots in

the "profound sense of moral

anxiety among Americans who were only just

beginning to grasp the implications of

the sweeping revolutions in their

social, economic, cultural, and

political worlds that historians too casually

refer to as 'Jacksonian Democracy'.

" Some people were drawn, by their

resentment of privilege and corruption,

to the side of the Jacksonian party,

with its egalitarian and

anti-intellectual standpoint; others objected to the

Jacksonians' establishment of an

"inviolable party dominion" because it

jeopardized "independent political

activity," communal feeling and tradi-

tional civic virtues. This

"anti-party" sentiment was especially strong,

claims Fox, among the evangelical

elements in the Ohio population, and

particularly among settlers from New

England. In this way the moral

overtones of the party conflict tended

to divide the voters of the state into

distinct ethnocultural groupings,

according to how their cultural attitudes

made them view such issues;

consequently, since particular ethno-cultural

groups had concentrated in particular

areas of the state, the distribution of

party support reflected

"ethnocultural regionalism."29

Yet the evidence for the critical

election of 1824 suggests that such

moralistic concerns were in fact the

common possession of all Ohioans at

the time and so provided no basis for

the electoral division. All accepted the

basic principles of republicanism and

federalism, and the disagreements

over those terms that had marked the

first party system in Ohio did not

reappear in the campaign of 1822-1824.

The tradition of"antipartyism," of

objecting to the control of an

"aristocracy" of office-holders, was now

turned against the "caucus

candidate," William H. Crawford of Georgia;

but he had in any case almost no support

in Ohio, and the attempt to

control public feeling by use of the

traditional nominating machinery was

attacked by the friends of all the

candidates in Ohio. At the same time "anti-

29. Fox, article, 162, 166-70, and

dissertation, 334, 372-93,421-31. Cf. Flinn, "Continuity

and Change in Ohio Politics,"

524-27.

16 OHIO

HISTORY

partyism" did not prevent any of

them from using techniques of partisan

organization and agitation. There was

undoubtedly a profound sense of

moral anxiety about the future of the

republic and about the "proper" role

of politicians, yet this anxiety was not

essential to the party division, even if

in some communities that had undergone

certain experiences it helped to

influence political choices.30

Furthermore, the distribution of the

vote in 1824 cannot be explained

simply in terms of ethnocultural

influences, at least not in the broad and

generalized terms commonly used. A fully

developed ethnocultural inter-

pretation emphasizes religion as much as

ethnicity, but it is very difficult to

discover very much about the

relationship between religion and voting in

the 1820s because of the scantiness of

the evidence. The general impression

is that the major churches, particularly

the Methodists, divided between

the candidates, although the Quakers

moved with some homogeneity

towards John Quincy Adams.31 It

is rather easier to test systematically the

broad generalizations commonly made

about the voting behavior of

settlers from different sections of the

Atlantic seaboard. Undoubtedly New

Englanders, clustered primarily in the

Western Reserve and the Ohio

Company counties, gave remarkably few

votes to Jackson in both 1824 and

1828.32 But is it equally true that

Southern and Middle-state origins in

themselves automatically produced

support for Jackson? The mere fact

30. For this election, see Eugene H.

Roseboom, "Ohio in the Presidential Election of

1824." Ohio Archaeological and Historical Publications, XXVI (1917),

153-224; Stevens,

Early Jackson Party in Ohio; Ratcliffe, "Voters and Issues." For the first

party system in

Ohio, and some of the attitudes it helps

to illuminate, see Donald J. Ratcliffe, "The Experience

of Revolution and the Beginnings of

Party Politics in Ohio, 1776-1816." Ohio History,

LXXXV(1976), 186-230.

31. Ratcliffe, "Voters and

Issues," 854. The Presbyterians also probably divided according

to whether they were associated with the

Pennsylvania Scotch-Irish or the New England

tradition.

32. Ratcliffe, "Voters and

Issues," 855. 856. There is almost no evidence about individual

voting behavior for this period in Ohio,

and the historian is forced to consider the behavior of

communities as defined by political

boundaries. He must therefore look forcommunities that

are fairly homogeneous, which means that

he should look for the smallest possible political

units. Unfortunately, it is difficult to

find township election returns for these early elections,

especially that of 1824, although it is

sometimes possible to associate a distinctive ethnocultu-

ral group with a particular township. In

general, the historian can make a systematic analysis

only at the county level, and even here

the historian is forced to rely on impressionistic sources

such as the various county histories and

gazetteers and Henry Howe's Historical Collections

of Ohio, 1st

ed. (Cincinnati, 1847) and centennial ed.

(2 vols., Cincinnati, 1889).

The historian must, of course, make use

of the 1850 Census, the first to provide suitable

material. But it is a mistake to assume

that the character of the population in each county was

necessarily the same in the earlier

decades as it was in 1850. And to say,

as Dr. Fox does, that

"The competitive stability of the

two parties in Ohio from 1834 to 1848 suggests that the

location of ethnic groups in 1850 was

not significantly different from earlier residential

patterns" is to use one's

conclusion as part of the proof that the conclusion is true. Fox article,

158.

Politics in Jacksonian Ohio 17

that Miami county, which in 1818 had

been reported as "settled by

emigrants chiefly from Pennsylvania, New

Jersey and Kentucky," returned

anti-Jackson majorities in 1824, and

subsequently, suggests that some

groups of Southern and Middle-state

settlers were less favorable to the

Jacksonians than were others.33

In fact, those communities which were

most probably dominated by

Southerners in the 1820s were far from

being uniformly strong in their

support of Jackson. The Virginia

Military District was, with reason,

regarded as the main center of Virginian

settlement, yet in this area in 1824

Jackson for the most part gained less

than his average proportion of the

vote over the state as a whole. In the

southern part of the district Jackson

gained some substantial majorities, as

he did in neighboring counties to the

west which were not particularly marked

by Southern settlers. In the

northern and eastern parts of the

district, Jacksonism was much weaker;

indeed, one contemporary observer gained

the impression in 1824 that "the

Kentucky and Virginia population, on the

Scioto, the Muskingum, and the

Upper M iami, supported Clay."

Certainly this was true of the area around

Chillicothe, an undoubted center of

Virginian settlement.34 Such evidence

suggests that Southerners in Ohio

provided considerable support for the

Adams-Clay party of 1828, and it is

interesting that the only counties in the

state (other than those settled by New

Englanders) which swung towards

Adams in 1828 were the three counties of

Logan, Champaign and Clark, of

which at least two were almost certainly

dominated by people from

Virginia and Kentucky.35 As

Eugene H. Roseboom suggested, Southerners

who settled before 1830 differed in

political outlook from later migrants

from the South; hence any association

between Democratic voting and

33. Samuel R. Brown, The Western

Gazetteer, or Emigrant's Directory (New York, 1820),

287-88.

34. Edward D. Mansfield, Memoirs of

the Life and Services of Daniel Drake, M.D.

(Cincinnati, 1855), 170. For Virginians

in the Scioto Valley at this period, see William Renick.

Memoirs, Correspondence And

Reminiscences of William Renick (Circleville,

1880), esp. 11;

John Cotton, "From Rhode Island To

Ohio in 1815," Journal of American History, XVI

(1922), 253; Morris Birkbeck, Notes

On a Journey In America (London, 1818), 64-5; Benton

J. Lossing, A Pictorial Description

of Ohio (New York, 1848), 83, 84, 88, 89. See also David

C. Shilling. "Relation of Southern

Ohio To The South During the Decade Preceding the Civil

War," Quarterly Publications of

the Historical and Philosophical Society of Ohio, VIII

(1913),4.

35. Gersholm Flagg to Azariah Flagg,

Springfield, O., November 12, 1816, and January 8,

1817, Solon J. Buck, ed., "Pioneer

Letters of Gersholm Flagg," Transactions of the Illinois

State Historical Society, (1910), 143, 145; John Kilbourn, The Ohio Gazetteer,

or Emigrant's

Directory, 11th, revised ed. (Columbus, 1833), 281; Howe, Historical

Collections (1847), 84;

Lossing, Pictorial Description. 41,

48, 72; William E. and Ophia D. Smith, A Buckeye Titan

(Cincinnati, 1953), 144; Ohio Writers'

Program of the Works Projects Administration,

Springfield and Clark County,

Ohio (Springfield, 1941), and Urbana

and Champaign County,

Ohio (Urbana. 1942).

18 OHIO

HISTORY

Southern settlers probably did not

develop strongly until the 1840s if

then."

It is equally difficult to prove that

Pennsylvanian origins as such made a

man more likely to vote for the

Jacksonians, for people from that

Commonwealth had spread to most parts of

Ohio, including those highly

favorable to Adams and Clay. Apparently

only those Pennsylvanians who

were also members of distinctive

non-English ethnic groups gave signifi-

cant degrees of support to Jackson.

Thus, in the end, the only generaliza-

tions about ethnocultural voting in the

1820s that may be made with

confidence are that Adams did well in

areas of New England and Quaker

settlement, while Jackson won much

support among German and Scotch-

Irish settlers from Pennsylvania.3'

But why should these groups behave in

this way'? Republicans from New

England had not always been noted for

insisting that a fellow New

Englander like Adams should be elected

President: they had fully support-

ed the election of Madison and Monroe.

Why had they now become so

much more self-conscious? Why did people

begin to talk, in the early 1820s,

of the "Universal Yankee

Nation"? The answer which emerges from their

spokesmen in Ohio is simply that the

South's success in the Missouri crisis

had made them aware of the power that

the South exercised in the nation, a

power which, like Rufus King. they

ascribed to the unity of political action

that was prompted by the "black

strap," the common interest of slavehold-

ing. As a New York politician recorded,

at this time many Republicans in

the North became "anxious to be

relieved" of the "reproach" of"support-

ing southern men"; and this feeling,

in New York as in Ohio, was strongest

among settlers from New England. Thus

the constant identification in later

years of the anti-Jackson men with

moralistic concerns may be largely

explained as resulting from the

extraordinary significance of the slavery

issue in the period of initial party

formation in the early 1820s.3s

But what of the "Pennsylvania

Dutch?" There can be no doubt of their

political homogeneity in 1824. for even

a future British prime minister

noticed it;9 but why did they vote so

overwhelmingly for Jackson in that

Presidential election? No doubt Dr. Fox

is right in saying that a study of the

36. Eugene H. Roseboom. "Southern

Ohio and the Union in 1863". Misis.ssippi lallev

Historical Review, XXXIX (1952), 38-40.

37. Ratcliffe. "Voters and

Issues." 862, 863.

38. John C. Fitzpatrick. ed., The

Autobiographyl of Martin Van Buren, reprint ed. (New

York. 1973), 1. 13148: .abez D. Hammond,

The History of Political Parties in the State of

Nevw Ylrk (Albany. 1842). 11. 127-28. See also Donald J.

Ratcliffe,"Captain.James Riley and

Antislavery Sentiment in Ohio.

1819-1824." Ohio History. IXXXI (1972). 76-94: idem.

"Voters and Issues." 851-55:

and Shaw Livermore. Jr.. The Twilight of Federalismi: Ihe

Disintegration of the Federalist

Party. 1815-/830 (Princeton. 1962),

95-97.

39. Hon. E. Stanley (later Earl

ofDerby). Journalof'a Tour in America, I824-25 (priately

printed in limited edition for Lord

Derby. 1931), 178.

Politics in Jacksonian Ohio

19

group's cultural attitudes can make its

political behavior understandable,

but what was it they perceived in

Jackson that drew them to his side'? How

can it have been their established

"political habits," since all the candidates

were portrayed as good Republicans and

earlier factional loyalties did not

directly relate to particular

candidates'?4" Probably, as Benson once

suggested, their behavior was an

expression of the "marked conflict"

between "Yankee" elements and

the "Dutch," but where is the contempor-

ary evidence to show it'? Unfortunately,

the German newspapers in Ohio

said little about their reasons for

supporting Jackson.41 One can only

assume that the Germans were overwhelmed

by gratitude to the hero who

had apparently defeated a British

invasion of America, since they saw it as a

defeat for those who had least sympathy

for them. In that case the loyalty

they now showed to Jackson was based on

similar roots to that of the

Scotch Irish from Pennsylvania, who

undoubtedly had good reason for

identifying themselves with him and

rejoicing over the defeat of the British

oppressor.42 Here again,

recent experiences may have heightened the self-

awareness of an ethnocultural group and

prompted its members towards a

specific choice of sides in this

critical election.

Whatever emphasis may be placed on such

ethnocultural factors,

however, the fact remains that neither

the Yankee-dominated Western

Reserve nor the Scotch-Irish and German

belt of settlement across the

"backbone" of the state acted

uniformly in 1824. Every county in each of

these belts gave at least one-third of

its votes to Adams or Jackson,

respectively; but the counties in the

center of the belts gave a plurality of

their votes to Clay. while those on

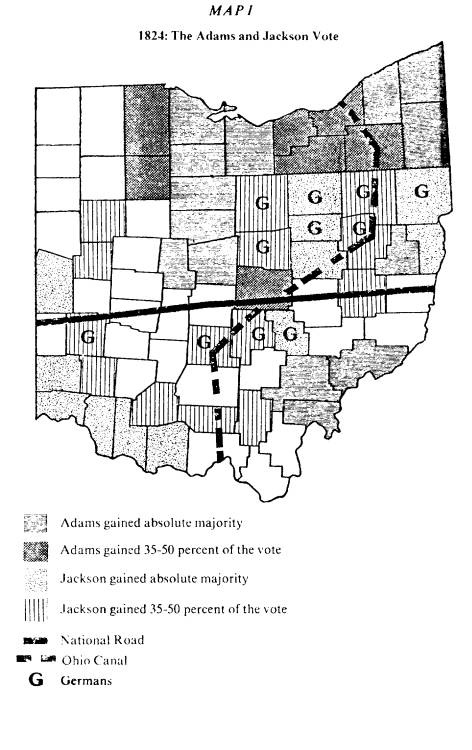

either side gave absolute majorities to

Adams or Jackson, as map I reveals.43

What the less enthusiastic counties

had in common was not a smaller

proportion of settlers from New England

or Pennsylvania, but rather a location

on the proposed route of the great

40. Fox. article. 165. 169. Kim T.

Phillips. "T1he Pennsylvania Origins of the lackson

Movement." Political Science Quarterlv.

XCI (1976). 489-508. sensitively reveals how a

radical faction concerned for economic

reform was drawn into the Jackson party in 1X24. but

she is less convincing in explaining why

so many of the state's factions decided to support

Jackson. The evidence suggests that the

clear preference, expressed early in the campaign by

the Scotch Irish. if not the Germans,

tempted all factions to attract their sympathy and sup-

port by jumping on the Jackson

band-wagon themselves.

41. i ee Benson. "Research Problems

in American Political Historiography," Mirra

Komaroxski. ed.. Commoon F 'rontiers of the Social Sciences (Glencoe,

11l., 1957), 153;

l.ancaster Ohio LtJklg/c,

1823-24. In view of the scantiness of contemporary evidence, it is

interesting to note that one British

traveller reported in 1817 that "the most perfect cordiality"

existed in I'crr\ county between the

German settlers and their neighbors. Birkbeck. Notes on a

Jou'ti e', 56.

42. Ratclillf, "Voters and

Issues." 863. The tensions between these non-English groups and

Nexw Englanders are persuasively

described in general terms in Kellev. "Ideology and Political

Culture." 534-43.

43. Some of the complexities of this map

are explained in Ratcliffe. "Voters and Issues."

853-63.

22 OHIO HISTORY

canal which was to connect Lake Erie

with the Ohio River. Indeed, nearly

all the counties which lay on planned

lines of communication. including the

National Road, tended to be more

favorable to Clay than their other

characteristics might lead one to

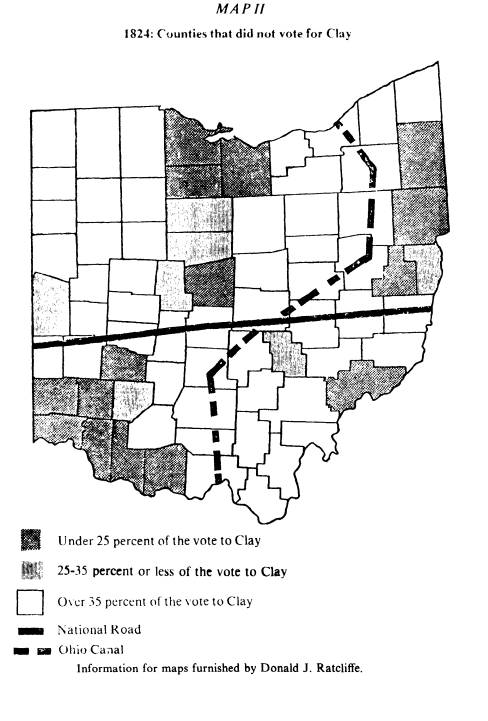

expect. (See map 11). This suggests that an

awareness of local economic interests

was a powerful influence on voting

behavior in this election, which is scarcely

surprising in view of the long

campaign to persuade Ohioans that the

state's economic problems, made

so obvious by the long depression

following the Panic of 1819. could best

be solved by the building of certain

roads and canals: while Henry Clay was

clearly seen as the one candidate with a

real chance of success who was

publicly committed to the "American

System" policy of federal appropria-

tions for such internal improvements. Of

course the demand for a Western

President had a moral content, combining

nationalism with a sense of past

sectional injustices, but it transformed

itself into votes mainly in those

counties which could see immediate

economic advantages in the "Ameri-

can System" of Henry Clay. For, as

Benson has written, "economic factors

are most likely to determine voting

behavior when direct, significant, and

clearly perceived relationships exist

among government action, party

policy, and material interests."44

In practice, the necessities of local

economic interest cut across the

ethnocultural considerations. Among New

Englanders in Ohio there was a

great public argument in 1824 as to

whether hatred of slavery or the need

for roads and canals should have

preference, for Adams as an Easterner

was considered unsafe on the

internal-improvement issue; and a moral and

upright Congressman like Elisha

Whittlesey, representing the most quin-

tessentially Yankee district on the

Western Reserve, nearly wrecked his

political career by publicly stating his

preference for roads and canals.45 In

other parts of the state similar debates

took place about the merits and

disadvantages of the leading advocate of

internal improvements, especially

where a local interest in the proposed

canals conflicted with some sort of

prejudice in favor of another candidate.

The uncertain outcome of this

conflict made

"chicken-hearted" politicians who wished to come out on the

winning side hesitate before committing

themselves to one candidate or

another, and so prevented Clay's

campaign from gaining the early

advantage of a legislative nomination

which his leading partisans had

hoped to secure.4' In

the end Ohio's voters had to choose between these

countervailing pressures, and

three-quarters of those who voted showed

44. Benson, Conceplt of Jacksonian

Democracv, 156. See also Ratcliffc, "Voters and

Issues," 850- 51 853-54: Fox.

article, 165, 167-68.

45. Whittlesey to Hammond, January 17.

February 14, 1824. Charles Hammond Papers:

Whittlesey to Giddings. January 18,

February 19, May 13, September 18, 1824. Joshua

Giddings Papers. Ohio Historical

Society.

46. Ratcliffe, "Voters and

Issues." 850-53.

Politics in Jacksonian Ohio

23

that they preferred a slaveholding

Western candidate, be it Jackson or

Clay, to a non-slaveholding candidate

associated with the economic

interests of the seaboard.47

The inadequacies of an ethnocultural

interpretation, pure and simple,

when faced by these complex interactions

of 1824 is further revealed by the

political behavior of the voters in the

line of counties between Sandusky

Bay and Columbus. They gave Adams between

91.2 and 56.5 percent of

their votes, and yet, contrary to Dr.

Fox, these counties were not dominat-

ed by New Englanders.48 True,

in Huron and Sandusky counties, as well as

in the northern half of Marion which

later became Crawford county,

Yankee settlers were numerous and may

well have formed a majority of the

population.49 And in Delaware

county many New Englanders moved in in

the decade before 1824, joining the

supposedly anti-Jacksonian Welsh of

Radnor township which, however, did not

become markedly opposed to

Jacksonism until the 1840s.5°

Yet throughout these counties many emi-

grants from Pennsylvania and other

states had also settled. In Union the

early settlers came chiefly from

Pennsylvania and Virginia, with New

Englanders not moving in until later.'"

Seneca was "settled principally

from Ohio, Pennsylvania, Maryland and

New York, and by some few

Germans," while in 1831 the

inhabitants of the southern half of Marion

(which retained the name after the

division of the county) were reported as

being "from other parts of Ohio,

from New York, New Jersey, Pennsylva-

nia, Virginia, and Maryland, and a few

from Kentucky."52

47. It seems unfair to criticize an

historian for failing to "reconcile" countervailing

pressures which contemporaries could not

reconcile, or for allowing them to prefer an

economic rationale over moral principle

or ethnic predilection. More reasonably Dr. Fox

criticizes my former article for failing

to provide "a comparable means of assessing the clear

deviations" from economic

motivations. In fact. I tried to do this by means of four tables

which indicated trends and exceptions. A

more sophisticated statistical approach, which

would have placed numerical values on

things like proximity to the proposed route of the

National Road, seemed to me pointless.

Fox, article, 156, 163, 165: Ratcliffe. "Voters and

Issues," 851-53, 854, 856, 858,

863.

48. Fox is apparently misled by Table II

in my former article which indicated "Yankees"

where there was evidence of some

settlement by them. as distinct from the terms "Western

Reserve" and "Ohio

Company" which referred to areas where they were predominant. Fox.

article. 165-66; Ratcliffe. "Voters

and Issues," 856.

49. Warren Jenkins, The Ohio

Gazetteer and Traveller's Guide (Columbus, 1837), 233:

Howe. Hi.storical Collections ( 1847),

445. and ibid. (1889), 1, 482.

50. Kilbourn, Ohio Gazetteer, 6th

ed. (Columbus, 1819), 63; [W. H. Perrin and J. H.

Battle. eds], History of Delaware

Countr and Ohio (Chicago,

1880), 191-96; William H.

.lones. "Welsh Settlements in

Ohio." Ohio Archaeological and Historical Society Publica-

tions, XVI (1907). 211-13. The voting returns for Radnor

township may be found in the

Delaware Patron. the Delaware Ohio Slate Gazette, the Olentangv

Gazette and Delaware

Adverti.ser. and the Columbus Ohio Statemnan. See also Fox,

dissertation, 369.

51. Kilbourn. Ohio Gazetteer (1833).

450; l.ossing. Pictorial Description. 94: Howe.

Htistorical ( ollc( tion.s ( 889),

1. 714.

52. Howe, Iistorical Collectionsr (1847), 457: Kilbourn, Ohio Gazetteer (1833),

298. For

24 OHIO HISTORY

Some consideration other than Yankee

settlement must explain the size

of the Adams vote throughout this area.

Contemporary sources make it

clear that these counties had one

distinctive feature in common. They all

lay on the route w. ch the great canal

had been expected to follow-until the

canal commissioners, for suspect

reasons, declared the route to be imprac-

ticable in January 1824. The resulting

disillusionment with grandiose

schemes of internal improvement may well

have weakened the appeal of

the leading

"internal-improvement" candidate for the Presidency. and

made the arguments against voting for

the leading Northern and "non-

slave" candidate quite ineffectual.

The presence of New Englanders merely

boosted Adams' majorities to levels not

attained even farther east on the

Western Reserve, and nearly all Adams'

banner counties combined New

England settlement with doubts about the

state internal-improvement

program.5

For the most part, however, the demand

for "Western" policies carried

the day, and the Adams' men's main hope

for victory in Ohio lay in the fact

that those who preferred a Western

candidate divided between Jackson

and Clay. But why did they divide, and

so provide the basis for the

subsequent party division? One reason is

undoubtedly the ethnocultural

preference of the Pennsylvania

"Dutch" and Scotch Irish. but another must

be the unpopularity of Clay in the

southwestern corner of the state. As map

II clearly demonstrates, Clay failed to

win votes not only in some German

and Yankee counties and in those areas

most opposed to the new canal

system, but also in the populous

counties most closely linked with

Cincinnati. This overwhelming prejudice

against Clay in this area did not

arise from hostility to the

internal-improvement program; nor can it be

explained simply in ethnocultural terms,

since the region was already

extremely diverse in the character of

its population.4 Contemporary

sources suggest that the prejudice

derived instead from the well-known

hardships suffered by Cincinnati, and

the area dependent on it, following

the Panic of 1819; for those hardships

had been aggravated by the decision

of the Bank of the United States to take

legal action against the many

debtors in that area to whom it had so

prodigally lent money before the

more on the settlement of this area, see

the references in Ratcliffe. "Voters and Issues," 856 n.

26.

53. Ratcliffe, "Voters and

Issues," 855-56.

54. Kilbourn, Ohio Gazetteer(18

19), 83. 158-59. and ihid. (1833). 66, 146-47. 229.249,309.

382-83. 467, 485: Howe, Historical

Collections (1847). 21, 72, 101, 229-30. 249, and ihid.

(1889). I1. 299, 301: Iossing, Pictorial Description. 36. 65. 79. 95. See also Shilling.

"Relation of Southern Ohio To The

South", 4: Jones. "Welsh Settlements in Ohio." 198-202:

Albert B. Iaust, The German Elemlent in lthe 'litle States (New York, 1927). I. 428-30:

Ratcliffe, "Voters and

Issues." 857. 863 n. 53.

Politics in Jacksonian Ohio 25

Panic, and the blame for that decision

fell on the Bank's legal agent in Ohio,

Henry Clay. Thus popular hardships in

this area heightened moral

anxieties and indignation about

privilege and corruption and the selfish

things politicians get up to-and gave

the populace a good reason for

turning against Clay.5

In sum, then, the"self-conscious

party loyalties" which were established

for many Ohio voters in 1824, at the

very beginning of the new mass party

system, were created by the response of

individuals to a range of factors.

Ethnocultural perception and prejudices

played an important part, espe-

cially as heightened by either

reawakened antislavery sentiment or Anglo-

phobia; but cutting across them were

other considerations, notably

sectional awareness, local economic

interest, and the passions and hatreds

created by the unusually severe

hardships suffered since the Panic of 1819.

In particular, the new party loyalties

were to some extent fashioned, by the

policy programs associated with each

national candidate. These issues at

stake as the Republican party broke

apart were clearly perceived by

contemporaries, and openly discussed in

the Ohio press during the

campaign.5 Of course,

Formisano is more or less right in saying that the

cleavage of 1824 in Ohio could reflect

"more immediate issue conflicts" so

clearly because the "self-conscious

party loyalties" typical of the later mass

party system did not exist; but that

cannot contradict the argument that

this issue-oriented electoral cleavage

helped to establish the very party

loyalties that Formisano is talking

about.57

However, the party cleavage of 1824 was

substantially modified in the

55. Cf. Fox. article. 165, 166, with

Ratclifle. "Voters and Issues," 857-61. Dr. Fox doubts

whether it may be truly said that

"the dynamic heart of the early Jackson party in Ohio" lay in

Cincinnati. As he points out. Jackson

gained only 44 percent of his Hamilton County vote in

the city, in comparison with the 57.5

percent of the Adams vote that was gained there. Yet this

does not contradict the fact that

Jackson won 55.3 percent of Cincinnati's votes, compared

with 32.9 and I 1.8 percent for Adams

and Clay respectively. And if the surrounding rural part

of Hamilton county and neighboring

counties-voted for Jackson by even heavier majorities.

this not only suggests that the city

contained a more variegated population with morediverse

interests and attitudes, but confirms

that Jackson sentiment was especially strong in the rural

area subject to Cincinnati's

metropolitan influence. In any case, from 1824 to at least 1832 the

initiative in organizing the Ohio

Jackson party came from Cincinnati rather than the state

capital. as Dr. Fox himself has

acknowledged. Fox, dissertation, 431, 440. 445.

56. Roseboom. "Ohio in the

Presidential Election of 1824," 153-224. Fox, article, 168,

states that, when I am not ignoring the

testimony of the actors, I am placing their words in a

context of my own, and not their,

choosing. The onus is surely on him to demonstrate the

point rather than for me to produce

still more testimony, yet it is interesting to note

contemporary editorials on the election

which see it in my terms: e.g., Liberty Hall and

Cincinnati Gazette, November 26, 1824; The Benefactor and Georgetown

Advocate, No-

vember 22, 1824; ChillicotheSupporter

and S(ioto Gazette, October 21, November 18, 1824.

57. Formisano, "Toward a

Reorientation of Jacksonian Politics," 58. It can be argued

that "self-conscious party

loyalties" already existed in Ohio deriving from the first party

system, but they had little influence in

1824 in an overwhelmingly Republican state in the

absence of a Federalist candidate. See

Ratcliffe, "Revolution and the Beginnings of Party

Politics," 192-227.

26 OHIO HISTORY

later part of the decade as at least

eighty thousand more voters were drawn

into the party conflict and formed their

party attachments. In this later

period the same factors as had operated

in 1824 were again at work, except

that the demand for internal

improvements in particular counties had

declined somewhat, since the projects of

1824 were already being

implemented. John Quincy Adams now

possessed all the advantages

enjoyed earlier by both himself and

Henry Clay, for since his alliance with

the latter in 1825 and his official

statements as President in favor of internal

improvements. Adams had come to

represent what most Ohioans had

wanted but not found available in the

1824 electoral campaign a non-

slaveholding President who favored

"Western" policies. This uniting of the

main opposing tendencies of 1824 ended

the political dilemmas of a

Congressman like Elisha Whittlesey, and

paved the way for his unanimous

re-election by his Yankee constituency

in 1826 and 1828.58 Certainly the

"Southern" quality of

Jackson's candidacy gave many men pause, and

turned against him those who were

concerned for the moral character of

the Republic if such a man gained power

as a result of the machinations of

party hacks as unscrupulous as Jackson's

Northern advocates were often

presumed to be.59

Such arguments might have been

overwhelming in 1828, had the Ohio

Jacksonians not been able to minimize

most effectively the differences

between the two parties over the

"American System" by supporting the

protective-tariff and

internal-improvement measures passed by the Con-

gress of 1828. As it was, they were able

not only to rely on strong support in

the southwestern counties and in

communities settled by German and

Scotch-Irish settlers from Pennsylvania,

but also to exploit two new

sources of support. First, there appears

to have been, especially perhaps in

backcountry areas, a widespread popular

suspicion of politicians and

lawyers, which had been of little

political significance in 1824 outside the

Cincinnati area, this ill-defined

prejudice worked in favor of a candidate

who did not possess power or the advantage

of office, who was not

commonly associated with politics, and

who had proved his commitment

to the Republic in its hour of gravest

peril.6" In addition, there is also

58. Hammond to J. C. Wright, Cincinnati,

March 16. 1825, Charles Hammond Papers:

('lay to Whittlesey. Washington, March

26. 1825, James F. Hopkins. ed.. The Papers of

Hli, r\ C/at (I.exington. Ky.. 1972), IV.

178-79. See also Ratcliffe, "Voters and Issues." 864-

66.

59 D. . Ratcliffe. "Antimasonry in

Context: Patterns of Conflict in a Western Yankee

Community. 1820-1840." an

unpublished paper which includes some interesting findings

about "anti-partvism" in this

period.

60. This perception of Jackson is best

analysed in John W. Ward. Andren .Jackson.

Srmthol For An Age (New York. 1955). though Ward does not always

discriminate between

attitudes common to the whole culture

and those peculiar to particular groups which tended

to favor Jackson politically.

Politics in Jacksonian

Ohio

27

evidence that Jackson's candidacy

benefitted in 1828 from the belief in

some quarters of Ohio that the old

Republican party of Thomas Jefferson

must be revived in order to prevent the

return to power of old Federalists

under the "amalgamationist"

regime of the second Adams.6' These new,

less tangible, influences which operated

on the new voters of 1828 not only

helped to bring about .ackson's narrow

victory, but also ensured that the

cleavage that had now been created among

the electorate would reflect a

range of influences even more diverse

than those of 1824.

The Implications for the 1830s and

1840s

Hence the primary determinants of voting

behavior in Jacksonian Ohio

were the partisan loyalties created in

the 1820s; and those loyalties were

established as a result of interacting

pressures and concerns which arose

out of immediate issues and the recent

experiences of Ohioans in the 1820s.

If these two propositions be accepted,

then important conclusions

immediately follow for the analysis of

the party alignments of the 1830s and

1840s. For one thing, it is clear that

the results of elections in most counties

and districts were determined by the

underlying pattern of party

identifications; and in most of those

counties the many new voters who

settled after 1830 did not differ

sufficiently from the older settlers in their

political predilections to overthrow the

established majority. Hence,

whenever a historian analyses the

distribution of voter support in terms of

electoral units, be they counties,

townships or wards, in any election (or

series of elections) between 1836 and

1852, the probability is that he is

studying a pattern which reflects the

concerns of the 1820s rather than those

of that later period. Thus, the fact

that the southwestern counties continued

to give majorities to the Democrats

through the 1830s and 1840s reveals

more about what had influenced an

overwhelming majority of the voters in

the period when most of their party

loyalties were formed, than it does

about what concerned them most during

those later decades.

This simple truth explains the paradox

that all students of Jacksonian

political behavior stumble over. In the

years after 1832, financial and

economic issues increasingly came to

dominate legislative proceedings,

party resolutions and addresses, the

political press, and even the private

correspondence of those actively interested

in politics. The importance of

this concern with matters of banking and

currency in Ohio has been well

brought out for the years after the

Panic by several writers, most notably

Roger Sharp."2 The

natural assumption to make after reading such

evidence drawn from the articulate

members of the political community is

61. D. .1. Ratclitte. "I he Persistence

of the First Party System: Southeastern Ohio. 1812-

1828." unpublished paper.