Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

VIRGINIA E. McCORMICK

Butter and Egg Business: Implications

From the Records of a Nineteenth-

Century Farm Wife

Few stereotypes have a clearer image or

more persistent endurance

than that of the nineteenth-century

married woman who devoted

herself to home and family and relied

upon her husband as the

economic provider. This image produces

the perspective that "a

dramatic increase has occurred in the

labor force participation of

women of all income levels, including

married women who traditionally

have felt no economic need to

work,"1 a viewpoint which permeates

twentieth-century public policy.

Researchers compiling statistics

regarding women's earnings in the

nineteenth century have focused

primarily on groups which contained

significant numbers. In 1900 experienced

factory girls could earn five

to six dollars per week for a sixty-hour

week, but domestic workers

earned as little as two to five dollars

for a seventy-two hour week.2 The

latter was a far more likely option for

married women forced to seek

employment outside their home.

Historians acknowledge that women

traditionally earned income by

taking in boarders, sewing or laundry.

Julie Matthaei estimates that at

the turn of the century 42 percent of

the employed women were earning

income in their own homes.3 Rural

homemakers, who had fewer

options for earning at home, often sold

butter and eggs, but little

research has examined the economic

impact of this activity.

Virginia E. McCormick earned a Ph.D. in

education at The Ohio State University and

has taught there, at Iowa State

University, and at the Pennsylvania State University.

This article is adapted from Virginia E.

McCormick, ed., Farm Wife: A Self-Portrait,

1886-1896. © 1990, Iowa State University Press, Ames, Iowa 50010.

1. Sandra L. Hofferth and Kristin A.

Moore, "Women's Employment and Mar-

riage," in Ralph E. Smith ed., The

Subtle Revolution (Washington, D.C., 1979), 99-124.

2. Carl N. Degler, At Odds: Women and

the American Family from the American

Revolution to the Present (Oxford, 1980), 382.

3. Julie Matthaei, An Economic

History of Women in America (New York, 1982),

198-99.

58 OHIO HISTORY

Was the butter and egg business simply a

vestige of an earlier era

when home production provided the goods

necessary for family

consumption and trade in a barter

economy, or does it offer clues for

contemporary workers seeking

opportunities in self-employment or

home-based work? How did it rank among

income producing oppor-

tunities for nineteenth-century women,

and was the money it produced

supplemental or essential family income?

Did the butter and egg

business of farm wives have significant

impact on the local and national

economy, or was it simply "pin

money" which did not merit inclusion

in income statistics?

These are questions which can be

answered only through an under-

standing of the historical perspective

of women's economic roles and

careful analysis of case studies which

survive as farm and home

account records.

There is overwhelming evidence that the

late nineteenth century was

a golden age of domesticity when

management of home and family

achieved importance not seen earlier or

later.4 As the industrial

revolution diverted much traditionally

home-based production to fac-

tories, particularly in textiles and

clothing, husbands and wives were

able to assume separate spheres of

responsibility. Men were increas-

ingly associated with the role of

economic provider and women with

the moral leadership of the family unit.5

Within these differentiated roles,

historians acknowledge that women

have always shared responsibility for

providing the basic necessities of

food, clothing, and shelter. Much of

this contribution consisted of

unpaid labor related to food

preservation and preparation, clothing con-

struction, and home management.

Researchers such as Alice Kessler-

4. Glenna Mathews, Just a Housewife:

The Rise and Fall of Domesticity in America

(New York, 1987). See also Annegret S.

Ogden, The Great American Housewife

(Westport, Connecticut, 1986).

5. For eloquent individual records see

Joy Day Buel, The Way of Duty: A Woman

and Her Family in Revolutionary

America (New York, 1984); Claudia L.

Bushman, A

Good Poor Man's Wife: Being a

Chronicle of Harriet Hanson Robinson and Her Family

in 19th Century New England (Hanover, New Hampshire, 1981); and Harriet Beecher

Stowe, Household Papers and Stories (Boston,

1896). For varied analysis see John

Demos and Susan S. Boocock eds., Turning

Points: Historical and Sociological Essays

on the Family (Chicago, 1978); Tamara K. Hareven ed., Transitions:

The Family and the

Life Course in Historical Perspective

(New York, 1978); Peter Laslett and

Richard Wall

eds., Household and Family in Time

Past (Cambridge, 1972); Michael Gordon, The

American Family in Social-Historical

Perspective (New York, 1978); and

Nancy F. Cott

and Elizabeth H. Pleck eds., A

Heritage of Her Own: Toward a New Social History of

American Women (New York, 1979).

The Butter and Egg Business 59

Harris recognize, but find it difficult

to quantify, the value of domestic

work and child care historically

performed by women.6

Women have also historically performed

socially useful work far

beyond that which is measurable in the

marketplace. Elliot and Mary

Brownlee emphasize contributions in

social welfare and health care

services, where women traditionally

served their "extended family"

and also as community volunteers.7

Some of the most penetrating questions

about the economic basis of

the nineteenth-century "cult of

domesticity," which maintained that

married women did not need to work for

pay, have been raised by Carl

Degler's contention that domesticity in

the short range increased

women's power, status and self

confidence, but in the long range weak-

ened their claim to the full range of

human experience.8 A homemaker

might reign supreme within her home and

be recognized for her

husband's status in the community, but a

price was paid with severely

limited economic, educational, legal and

political opportunities.

Recent research challenges the concept

of a dramatic twentieth-

century increase in women's employment,

on the basis that it ignores

changes in the census definition of

employment and the locus of the

work. Because the 1900 census requested

identification of one's

"primary occupation" and

recorded most married women as house-

wives, Christine Bose contends

statistics showing 20 percent of the

female population employed in 1900 and

54.5 percent employed in 1985

are an inaccurate comparison.9 In

1985 only 50.2 percent of employed

women worked full-time year-round, and

demographers suspect that

large segments of the "underground

economy" from child care to

piano lessons and garage sales are still

under-reported. Bose contends

that employment definitions which

included similar part-time and

home-based work in 1900 would have

revealed from 48.5 percent to

56.7 percent of the female population

was actually earning income.10

6. Alice Kessler-Harris, Women Have

Always Worked (New York, 1981). See also

the Industrial Relations Research

Association Series, Working Women: Past, Present,

Future (Washington, D.C., 1987).

7. W. Elliot Brownlee and Mary M.

Brownlee, Women in the American Economy:

A Documentary History, 1675 to 1929 (New Haven, 1976), 1-39.

8. Carl N. Degler, At Odds: Women and

the American Family From the American

Revolution to the Present, 49, 306, 328, 344, and 375.

9. Christine E. Bose, "Devaluing

Women's Work: The Undercount of Women's

Employment in 1900 and 1980," in Hidden

Aspects of Women's Work (New York, 1987),

95-115.

10. For statistics on percentage of female

population and percentage of married

women in the labor force from 1870

through 1940 see Women's Occupations Through

Seven Decades, U.S. Dept. of Labor, Women's Bureau Bulletin 218

(Washington, D.C.,

1947), 34, and Ray Marshall and Beth

Paulin, "Employment and Earnings of Women:

Historical Perspective," in Working

Women: Past, Present, Future, 1-36.

60 OHIO HISTORY

Social science researchers recognize

that the history of formal

employment for wages is only a minority

theme in the history of

working women, and are now constructing

research models which

attempt to identify where and how women

actually worked.11 Recent

increases in self-employment and

home-based work, by both men and

women, have encouraged a review of the

existing historic perspective

of such work. Scholars are focusing on

positive aspects such as

freedom of supervision and flexibility

for family responsibilities, as

well as negative aspects of potential

exploitation through low wages or

poor working conditions.12

Such analysis of home-based work focuses

renewed attention on

"women's work" of generations

past. In the nineteenth-century cult of

domesticity, a married woman's presence

in the labor force was

usually perceived as a signal that her

husband was unable to provide

adequate income. For women who wanted or

needed to increase family

income but preserve their husband's

reputation, there were alterna-

tives such as taking in boarders or

working as a seamstress, which were

seen as non-threatening and socially

acceptable "woman's work" if

done in one's spare time at home.13

In rural areas boarders were rarely

available as a viable source of

income, but a widely accepted

alternative was a farm wife's butter and

egg sales. 14 Such trade was

carefully nurtured as a secure source of

income in the volatile uncertainty of

the agricultural economy where

adverse weather or livestock disease

could mean disaster.

The prevailing social attitude about

butter and eggs sales was

non-threatening. Many persons raised on

farms remember these sales

as "pin money for the women, money

never taken too seriously in the

days when bookkeeping was casual and

accounting unknown."15 It

was income upon which farmwives relied

well into the twentieth

century, sustaining many a family during

the Great Depression of the

1930s. In memoirs of his rural boyhood,

Curtis Stadtfeld was surprised

11. Patricia Bronca, "A New

Perspective on Women's Work," Journal of Social

History, 9

(Winter, 1975), 129-53.

12. Eileen Boris and Cynthia R. Daniels

eds., Homework: Historical and Contempo-

rary Perspectives in Paid Labor at

Home (Chicago, 1989).

13. Julie Matthaei, An Economic

History of Women in America, 120-21, 198-99.

14. One of the few researchers who has

analyzed the income of rural homemakers is

Joan M. Jenson, "Cloth, Butter and

Boarders: Women's Household Production for the

Market," Review of Political

Economics, 12 (Summer, 1980), 14-24; and Loosening the

Bonds, Mid-Atlantic Farm Women,

1750-1850 (New Haven, 1986).

15. Henry C. Taylor, reflecting on his

mother's exchange of butter and eggs for

simple grocery supplies and basic dry

goods, in Tarpleywick: A Century of Iowa Farming

(Ames, Iowa, 1970), 119.

The Butter and Egg Business 61

that his father's 1935 account book

showed the cash income from

poultry and eggs nearly equaled that for

the farm dairy herd.16

The scarcity of contemporary records

makes the 1886-1896 diaries

and farm accounts kept by Margaret Dow

Gebby, a Logan County,

Ohio, farmwife worth analyzing. Her

journals confirm widely accepted

images of farm wives exchanging butter

and eggs for goods at the

general store, but they also provide

surprising glimpses of a thriving

home business which contributed

regularly and significantly to house-

hold expenses.17

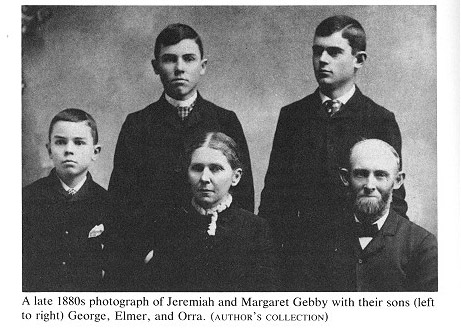

Margaret taught school prior to her

marriage to Jeremiah Morrow

Gebby, a successful grain and livestock

farmer in northwestern Ohio.

With him she raised three sons and cared

for her widowed mother-in-

law. Her sister Martha lived just up the

road, and other siblings and

extended family resided at distances

within which close relationships

could be maintained.

Margaret Gebby's decade of daily records

of family activities, and

accounts of income and expenses for farm

and household, invites

readers into the life of a late

nineteenth-century midwestern farm

woman. Readers share the cycles of work,

leisure and social interac-

tion experienced by rural midwestern

women and their families a

century past.

The Gebbys lived in Logan County, just

west of Bellefontaine, on a

286-acre grain and livestock farm. It

was neither the largest nor the

most profitable farm in its neighborhood,

but was well above average,

ranking in the top 10 percent for Ohio.

In 1880 its land and buildings

were valued at $17,800, its equipment at

$2500, and the agricultural

products produced at $4085. The farm

included 28 acres of corn, 58

acres of wheat, an acre of potatoes, an

orchard of 75 fruit trees, and the

remaining land in hay, pasture and

woods for 74 cattle and 22 swine.18

Margaret Gebby's household through most

of this period included

her husband, three teenage sons, and her

widowed mother-in-law. Her

expenses regularly included payments to

women in the neighborhood

for services rendered. During the early

years she sent her washing out

each week to a neighbor and hired

domestic help by the day during

spring cleaning. Later she hired a

neighbor woman to live in and help

with the domestic work. To supplement

the sewing and mending she

and her mother-in-law did, she hired

neighbors or a seamstress in town.

16. Curtis K. Stadtfeld, From the

Land and Back (New York, 1972), 120.

17. Virginia E. McCormick ed., Farm

Wife: A Self-Portrait, 1886-1896 (Ames, Iowa,

1990).

18. Non Population Census Schedule, 1880

Products of Agriculture, Logan County,

Ohio, Harrison Township, ED 113, p. 12

#4 and p. 17 #4.

|

62 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

Margaret's own source of income came from sales of her butter and eggs. She regularly milked three cows and cared for her poultry each morning and evening, producing enough to provide both for family consumption and for sale. Of course butter production peaked in the spring as cows calved and increased their milk production, but it is astonishing to note that butter prices could fluctuate as much as 80 percent during a single year, from 12 to 22 cents per pound in 1888. Farm wives had no choice but to adjust their spending patterns to seasonal fluctuations in the prices they received, for they were forced to accept what the market offered for their perishable commodities. Like other farmwives, Margaret Gebby traded at one general store and usually matched the total price of her purchases to the value of the produce she brought to sell. Rarely did she leave a small balance on her account, take part of her sales in money, or as she phrased it, "lift" a little credit against her store account. Butter was priced by the pound and eggs by the dozen, but odd amounts were regularly sold. Both sales and purchases could be precisely controlled since clerks weighed or measured everything to order. |

The Butter and Egg Business 63

A number of entries from her 1888 diary

furnish examples of how she

did business.

5 Jan.-Grandma & I went to town had

11 1/2 lbs of butter $2.10, got blue calico

dress, tea, baking powder, peaches, oil

cloth, braid for Grandma's dress &c

$2.12 ... 13 Jan.-was at Boals store had

11 lbs 3 oz of butter $2.01 got table

linen 21/2 yds at 45 cts pr yd 6 yd

toweling 2 yd at 11 ct, 4 yd at 10 cts pr yd,

coffee 28 cts ... 26 Jan.-Had 7 lbs 10

oz butter $1.52, got sugar $1.00 coffee

28 cts peaches 32 cts, apricots 19 cts,

Oysters 70 cts ... 12 May-Baked bread,

pies and cookies, churned, went to town

this afternoon, had 17 lbs of butter at

18 cts 9 doz eggs 89 cts = $3.06 got coffee,

baking powder, cornstarch, beans,

peaches, 2 cans apricots, scrim, lamp

& chimney &c $2.95 Jerry got fish 63,

Century 35, Harpers 10, Lemons 20,

Bananas ... 2 June-Went to town this

afternoon, had 22 lbs 14 oz of butter 12

cts pr lb, got coffee, tea, bluing, muslin,

candy, fish $1.61, left a balance of

$1.13 ... 4 Aug.-Baked bread and pies and

apple dumplings for dinner, went to town

had four lbs of butter 60 cts and 4 doz

eggs 56 got a calico meat platter 60

cts. screen wire 35 cts rivets 25 cts . . . 25

Aug.-sold 15 lbs of butter this week

$2.25 got corn starch, cinnamon, under

vest, buttons, stocking $1.16 ... 13

Sept.-churned this morning, went to town

this afternoon had 12 lbs of butter, 3

doz eggs $2.25 got Elmer overalls, collars,

copperas, cinnamon & pepper, mustard

seed. 19

As a farm wife selling butter and eggs,

Margaret Gebby represented

labor and management, production and

marketing, and long-range

planner and chief of daily operations

all at one time. She coped with

cows which went dry before she expected,

illnesses which interrupted

her work, and decisions about whether

eggs were to be sold or set to

hatch. She was also concerned with

increasing production, and upgrad-

ed her stock with Jersey cows and White

Leghorn chickens as it

became possible.

2 Feb. 88-I began churning this morning

before eight Oclock and churned till

two, and still did not get butter ... 9

Feb. 88-churned but failed to get butter,

quit milking Daisy ... 21 Mar. 88-I have

a very bad cold, Orra milked for me

this evening ... 14 Apr. 92-Set a hen

under a gooseberry bush, one between

the houses, one in George's boat ... 24

Apr 93-Set a hen in the old house on

the shelves, one in the calf stable

manger, found one setting in the briar patch

on 30 eggs ... 10 Aug. 96-I exchanged 2

sitting of Eggs with Mr George

Ebrite, his were White Leghorns ... 26

May 92-advertised for a good Jersey

cow in the want column of the Republican

Margaret Gebby kept meticulous daily and

monthly accounts of her

transactions, but did not record farm

and family expenses separately.

19. Margaret Dow Gebby Diaries, MSS 964,

Ohio Historical Society, Columbus,

Ohio. Subsequent entries from this

collection are cited by year and are quoted with

spelling, punctuation and capitalization

as it appears in diary entries.

64 OHIO HISTORY

It is possible, however, to separate

household expenses for a year and

determine the portion which were met

through butter and egg sales. In

1888, a representative year when the

household contained the six

persons mentioned above and the economy

was relatively stable, total

cash expenses for family living were

$615.51. Of this total, Margaret's

dairy and poultry operation provided

$130.41, or 21 percent.20

At that time, one of the highest status

and best paying positions

available to women in Logan County was

that of schoolteacher. A

woman teaching full-time in the county's

one-room schools earned an

average of $182 annually.21

If the teacher worked at least forty hours

per week during the twenty-nine week

term and Margaret worked

about ten hours per week year-round, the

butter and egg business

provided more income per hour.22

Recent statistics report all working

wives, both part and full-time, on

average contributed about 26 percent of

the total family income. Those

working full-time year-round contributed

38 percent.23 Even by current

standards Margaret Gebby's butter and

egg business earned substantial

income for a part-time business.

Of course, the Gebbys kept the produce

they needed for home

consumption. Margaret's butter records

for 1888 show that she sold

496 of the 612 pounds produced. At the

average sales price of 18 cents

per pound, the 116 pounds used at home

would have yielded an

additional $24.88. Between March and

September she sold 83 and 1/2

dozen eggs, and her baking and cooking

suggests the use of more than

that at home. The family often had

chicken for dinner, drank butter-

milk, ate cottage cheese, and used cream

liberally when they made ice

cream. It does not seem farfetched to

assume that the cash value of the

dairy and poultry products this family

consumed exceeded that of

those sold. Some of this value would

have been offset by the costs of

20. Arguments could be made that items

such as a $20 watch for a son, or $27 for a

suit and topcoat for the husband, served

many years and should not be included as

"annual" family living

expenses. Some might credit the butter and egg income with

providing as much as 25 to 30 percent of

the family's annual expenses.

21. John Hancock, Thirty-Fifth Annual

Report of the Commissioner of Common

Schools, [Year Ending 31 August 1888] (Columbus, 1889), 49.

Wages for primary

teachers averaged $36 per month for

males and $26 for females for a 29-week term in

Logan County. This was slightly above

the Ohio average of $37 and $27 monthly for a

30-week term.

22. Twenty-nine weeks times forty hours

equals 1080 hours. Fifty-two weeks times

ten hours equals 520 hours. One hundred

eighty-two dollars divided by 1080 hours is

approximately 17 cents per hour, while

$130.41 divided by 520 is slightly over 24 cents

per hour. These are, of course,

estimates rather than actual figures regarding hours

worked.

23. Ralph E. Smith, The Subtle

Revolution, 12.

The Butter and Egg Business 65

the buildings which housed cows and

chickens and the farm produce

they consumed as feed.

Margaret's profits are also lowered by

regular donations of butter

and cottage cheese to the church bazaar,

much like current church or

school groups rely on donations from

local businesses. One of the most

significant revelations of these diary

records is that the business

aspects of a farm wife's butter and egg

business were recognized

throughout the community. When Margaret

made sales directly to

relatives or neighbors, as she often

did, everyone carefully paid the

same price being offered at the general

store.

22 Mar. 94-Went to town this afternoon

had 18-12 of butter 3 doz of eggs =

3.43 got lemons, oranges, ginger snaps,

bananas, mustard, gingham & thread,

pepper, & peaches & $1.20 in

money, took 3 lbs of butter and 4 doz eggs to D.

Dows for the Easter supper tomorrow evening ... 20

Sept. 89-Grandma & I

went to town got coffee, sugar, Flower pot, three

spools of thread, a box to

pack eggs in for winter use, had 9 lbs 4

oz of butter, took Mrs Wright 50 cts

worth of butter . . . 4 June 92-Martha

Krouse [neighbor] got a lb of butter 12

cts, Lyman [brother] got 6 lbs 75 cts,

Boals [store] got 9-4 $1.13, got 2 pr silk

mitts 50 cts, 1 can apricots, 2 cans

corn, Raddish seed, & Bananas 15 cts ...

25 Mr. 93-Went to town this afternoon.

Boals got 15-4 1/2 of butter $3.36 got

Apricots, Plums, corn, Beans, Raisins, coffee,

braid, buttons, mustard,

Oranges, & yarn $2.37, called at

Fathers, he got 3 lbs of butter 66 cts, Mrs

Parker 2 1/4 50 cts.

When the Gebby farm installed a windmill

to pump water for

livestock in 1889, the family kitchen

was remodeled to include an inside

pump for water and a creamer to store

milk and separate the cream.

Margaret does not specifically describe

her churn, but in 1893 she

purchased a new one which she noted in

her diary completed her

churning in eighteen minutes.24 Box

and cylinder churns had been on

the market some twenty years, a time

span between invention and

adoption by this homemaker which is

particularly revealing when one

realizes that such a labor-saving piece

of equipment cost about the

equivalent of two week's butter sales.

22 Feb. 93-Jerry & I went to town

looked for a churn to suit us, we liked a

Sidney churn quite well, ordered one ...

27 Feb.-Jerry got the churn I

ordered last week ... 28 Feb.-Churned

with my new churn, had nice butter

but was a long time in churning, think I

had the cream too cold ... I

Mar.-Paid for the churn $4.50, churned

again this morning in about 18 min.

24. The Sidney churn was apparently a

local model of a box, cylinder or barrel style,

all advertised in the Sears and Roebuck

catalog at a comparable price. Margaret's diaries

imply that she had been using the older

dasher style churn which normally required forty

to sixty minutes to produce butter.

|

66 OHIO HISTORY |

|

The butter and egg business portrayed in Margaret Gebby's diaries was probably typical of her operation for more than thirty years as a farm wife, and her sisters and a significant number of neighbors had similar operations. In 1902 the county history noted 600,000 pounds of butter were marketed, and that "does not include creamers but simply the product of the farm and household."25 Such operations were widespread in rural areas throughout the country and reflect an economic contribution by women which has been largely ignored. The significant difference between the butter and egg business described in Margaret Gebby's diaries and a modern business such as a catering service run by a housewife from her home is not the work done or the income produced, but society's perception of the two businesses. Nineteenth-century farmwives considered themselves, and reported themselves in the census, as housewives. Income in a cash economy is extremely difficult to estimate accurately, but the time farmwives committed to the butter and egg business, the percentage of family living expenses which they earned, and their decision-making

25. Robert P. Kennedy, Historical Review of Logan County, Ohio (Chicago, 1903), 154. |

The Butter and Egg Business 67

responsibilities are remarkably similar

to a twentieth-century home-

maker operating a part-time business

from her home.

An intriguing revelation from these

diaries is the reference to other

women regularly earning money by doing

laundry, sewing, houseclean-

ing, and wallpapering. In a rural

community where many full-time

housewives earned cash income, the

butter and egg business was

apparently at the peak of the economic

hierarchy, conducted by

upper-middle-class farm wives who could

afford to own more than one

family milk cow. Margaret often sold

butter to neighbors, apparently

when their own cow was dry.

The butter and egg business clearly

reflects significant economic

activity which has not been accurately

reported. Records such as

Margaret Gebby's suggest a particular

need to reassess the historic

economic contribution of married rural

women, even those of the

upper-middle-class.

As a case study, these diaries suggest

that the butter and egg

business was both a vestige of earlier

eras when home production

provided the goods necessary for family

consumption and for trade in

a barter economy, and a home-based

business remarkably similar to

those currently conducted by many

self-employed workers. Even

though the Gebby farm was above average,

Margaret's butter and egg

income was not purchasing luxuries but

routine supplies for family

living.

If dairy and poultry operations like the

one described in these diaries

contributed approximately $100,000 to

the economy of a typical mid-

western rural county at the turn of the

century,26 a national figure for

such business would clearly reveal a

significant economic contribution

by married women which deserves to be

recognized.

26. The 600.000 pounds reported for 1902

in the county history would produce

$100,000 if the price averaged sixteen

and seventeen cents per pound, which is less than

the eighteen cents computed from

Margaret's accounts for 1888.

VIRGINIA E. McCORMICK

Butter and Egg Business: Implications

From the Records of a Nineteenth-

Century Farm Wife

Few stereotypes have a clearer image or

more persistent endurance

than that of the nineteenth-century

married woman who devoted

herself to home and family and relied

upon her husband as the

economic provider. This image produces

the perspective that "a

dramatic increase has occurred in the

labor force participation of

women of all income levels, including

married women who traditionally

have felt no economic need to

work,"1 a viewpoint which permeates

twentieth-century public policy.

Researchers compiling statistics

regarding women's earnings in the

nineteenth century have focused

primarily on groups which contained

significant numbers. In 1900 experienced

factory girls could earn five

to six dollars per week for a sixty-hour

week, but domestic workers

earned as little as two to five dollars

for a seventy-two hour week.2 The

latter was a far more likely option for

married women forced to seek

employment outside their home.

Historians acknowledge that women

traditionally earned income by

taking in boarders, sewing or laundry.

Julie Matthaei estimates that at

the turn of the century 42 percent of

the employed women were earning

income in their own homes.3 Rural

homemakers, who had fewer

options for earning at home, often sold

butter and eggs, but little

research has examined the economic

impact of this activity.

Virginia E. McCormick earned a Ph.D. in

education at The Ohio State University and

has taught there, at Iowa State

University, and at the Pennsylvania State University.

This article is adapted from Virginia E.

McCormick, ed., Farm Wife: A Self-Portrait,

1886-1896. © 1990, Iowa State University Press, Ames, Iowa 50010.

1. Sandra L. Hofferth and Kristin A.

Moore, "Women's Employment and Mar-

riage," in Ralph E. Smith ed., The

Subtle Revolution (Washington, D.C., 1979), 99-124.

2. Carl N. Degler, At Odds: Women and

the American Family from the American

Revolution to the Present (Oxford, 1980), 382.

3. Julie Matthaei, An Economic

History of Women in America (New York, 1982),

198-99.

(614) 297-2300