Ohio History Journal

EDUCATION IN TERRITORIAL OHIO*

BY W. ROSS DUNN

In tracing the beginnings of education

in that part of

the old Northwest that later became

Ohio, the historian

naturally turns to that much noted work

of the decadent

Congress of the Articles of

Confederation, the North-

west Ordinance or the Ordinance of

1787. His efforts

are not unrewarded, for Article Three

contains the oft

quoted declaration that "schools

and the means of edu-

cation shall forever be

encouraged". However, this is

all, and it is necessary to turn

elsewhere to find the be-

ginning of the policy of land grants

for schools. It is

important to note the beginnings

briefly, for besides pro-

moting the settlement of the territory,

the grants en-

couraged education, and later

contributed to the sup-

port of the schools. They were at least

the background

of the beginning of education in Ohio.

Furthermore, it

was the beginning of a policy that was

later generally

extended to include all the lands of Ohio,

although in the

original patents it applied only to

certain grants. In the

end it became a regular land policy of

the West and

each state admitted after 1842 was

given section 36 of

each township for school purposes.1

1 Willis Mason West, American History

and Government, Allyn and

Bacon, 1913, pp. 270, 274.

* Awarded the annual prize offered by

the Ohio Society of Colonial

Wars, for the best essay on early

Western history and offered as a

thesis for the degree of M. A. in the

University of Cincinnati, 1925.

History Department.

(322)

Education in Territorial Ohio 323

By going back a little further to the

less renowned

Land Ordinance of May 20th, 1785, the

legislative be-

ginning of the policy of donating land

for the benefit of

education is found. That Ordinance, in

addition to pro-

viding for the rectangular surveys of

land in advance

of settlement and the sale of land in

small quantities by

land offices, "reserved the lot

No. 16, of every township,

for the maintenance of Public Schools

within the said

township."2 It is rather

reasonable to suppose that the

idea of granting one thirty-sixth of

the land for school

purposes was not put in by accident.

The idea was in

the minds of some prominent men

somewhat earlier.

The suggestion was likely born of the

consideration of

the question of compensating

revolutionary soldiers by

grants of the public domain in the

West. In a com-

munication of Colonel Timothy Pickering

relating to

lands in the West for soldiers, there

is reference to other

land for the "common good"

and this included "estab-

lishing schools and academies".3

This communication

was forwarded through Generals Putnam

and Wash-

ington to Congress. The idea of land

reservations for

the support of church, highways and

schools had been a

topic of conversation among such men as

Washington,

Webster, Paine, Bland, Pickering,

Bayard and Hutch-

ins.4

The Ordinance of 1787 was passed

July 13 and ten

2 Land Laws of Ohio, A Compilation of the Laws, Treaties, Resolu-

tions and Ordinances of the General

and State Governments, which relate

to Lands in the State of Ohio, p. 154.

3 Clement L. Martzolff, "Land

Grants for Education in the Ohio Val-

ley States," in Ohio Archaeological and Historical Society

Quarterly and

Proceedings, Vol.

25, p. 65.

4 The Records of the Original

Proceedings of the Ohio Company.

Edited with Introduction and Notes by

Archer Butler Hulbert, Cincin-

nati, 1882, Vol. I. Int. p. XXV; Vol. I. p. CXXXVI-VII.

324

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

days later another Ordinance was passed

by Congress,

which renewed the provision of the

Ordinance of 1785,

in reserving section 16 of each

township for schools

and further provided that two townships

as near the

center of the grant as possible should

be reserved for

the purposes of a University. The

agents of the Ohio

Company took advantage of this

provision in their con-

tract with the Board of Treasury, which

provided that

a clause or clauses "shall or may

be inserted" reserving

section 16 for schools, 29 for religion

and sections 8, 11,

and 26 for the use of, and subject to,

the disposal of

Congress. Also that two complete

townships might be

laid off by the parties of the second

part as near the

center of their grant as possible, for

a university.5

The next grant of Ohio lands was that

to John

Cleves Symmes between the Miami rivers.

It contained

the provision for school and church

land and also a

grant of a college township. Symmes had

only asked

for one township of college lands. His

early map shows

this reserved opposite the Licking

river. Later the

amount of land that Symmes applied for

was cut down

one-half, as his agents feared they

would not be able to

make payments on the full amount.

Symmes learned

that the smaller amount did not entitle

him to a college

township and sold his reserved lands.

Congress, how-

ever, granted a college township, thus

leading up to pro-

longed negotiations before the college

lands were finally

set apart, which were connected with

Miami Univer-

sity.6 This provision for school lands

was not included

6 Land Laws of Ohio, p. 154; Records of the Ohio Company, Vol.

I, pp. 13, 14, 31, 32, 33.

7 Judge Jacob Burnet, Notes on the

Early Settlement of the North-

western Territory, Cincinnati, 1847, pp. 428, 433.

Education in Territorial Ohio 325

in the Western Reserve, Virginia

Military and other

lands of the territory.

In arranging for the formation of a

constitution in

Ohio, Congress offered certain parts of

its lands in Ohio

for public purposes provided the lands

be exempt from

taxation for five years. The

Convention, meeting to

form a constitution, saw the chance and

drove a bar-

gain with Congress to extend the

provision and set aside

one thirty-sixth of all the lands in

the state for school

purposes. After many difficulties and

later negotiations

this provision was carried out by

granting part sections

where full sections were not available

and by granting

extra lands where available to make up

for deficiencies

in other sections. How these lands were

later wasted so

that they returned much less than they

should to the

Common School Fund of Ohio is part of a

later story.7

The motive for including public lands

in early grants

has sometimes been questioned. Some have thought

that sections 16, 29, 8, 11 and 26 were

the top, doll,

boomerang, balloon and whistle put in

the package to

make the land sell better. Those asking

for such public

lands were accused of similar motives.

No doubt these

motives may have influenced some as

well as a real and

sincere interest of many in the things

such land was in-

tended to promote. Furthermore, if such

lands were

supposed to attract settlers, such

settlers must have been

thought to have an interest in such

worthy objects as

education, religion and roads. While of

course there

was the universal appeal in getting

something for noth-

ing, a variety of motives were no doubt intermingled.8

7 Martzolff, Land Grants, pp. 68-69;

Land Laws of Ohio, pp. 155, 157;

A History of Education in the State

of Ohio, a Centennial Volume, 1876,

pp. 9-75.

8 Martzolff, Land Grants, p. 66.

326

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

The interest of the people of the Ohio

Company in

education did not lapse on being

successful in securing

land grants with reservations for

religious and educa-

tional purposes. On March 7, 1788, a

committee was

named to secure a suitable teacher

"of religious and

educational training" to accompany

the settlers to the

lands on the Ohio. The committee

engaged the Rev.

Daniel Story for the purpose, and

called for public sub-

scriptions to cover the expenses. At a

meeting of the

Directors of the Company, August 4,

1788, provision

was made for leasing lot 16 of each

township for a

period of ten years, after March, 1789,

to be cleared,

fenced and left in grass. In November

of the following

year the Agents of the Company arranged

for a com-

mittee to make a large scale map

showing the public

lands, namely; the lots of Congress,

the school lots, lots

for religious purposes, for a

university, and other com-

mon property lots.9

The following year the Company took

what might

be called a more active interest in

education. At a meet-

ing of the Agents and Proprietors, July

16, 1790, at

Marietta, a motion prevailed to

appropriate $150 for the

support of schools. The amount was to

be justly ap-

portioned among the settlements of

Marietta, Belpre and

Wolf-Creek. This money was later to be

restored to

the funds of the Company from money

raised among

the first settlers for the

"Support of Religion and for

Scholastic Education". Although a

committee was

named in each settlement to receive and

expend the

funds, the contemplated action was not

secured, perhaps

because the ratio of distribution had

not been desig-

9 Records of the Ohio Company, Vol. I, p. 39-40.

Education in Territorial Ohio

327

nated. At any rate, in the following

December a com-

mittee of three was appointed to

apportion this money

and to devise ways and means for the

opening of schools

in Marietta, Belpre, Wolf-Creek and

Newbury. This

does not seem to have been effective

yet, for a resolution

of almost a year later, December 5,

1791, provided that

the money appropriated for the

education of the children

should be divided among the settlements

in the same

proportion as money granted for public

teachers by vote

in the meeting of April 6, 1791.10

At the meeting here referred to a

committee which

had previously been appointed to

suggest measures to

be adopted to furnish the several

settlements with re-

ligious instruction, made its report. As

a result the sum

of one hundred-sixty dollars was

appropriated for the

purpose. Of this sum Marietta was to

get $84, Belpre

$50, and Waterford $26. No town was to

receive its

share unless it maintained a school the

designated

amount of time, which was one year for

Marietta, seven

months for Belpre and three and

one-half months for

Waterford. A committee was to be

appointed in each

settlement to obtain the "Public

Teacher", who was to

be approved by the Directors of the

Ohio Company be-

fore entering on his duties. These

teachers were to

give religious instruction for the

public benefit.11 This

ratio used for distributing the $160

for religious in-

struction was to be taken as a ratio

for distributing the

$150 for secular education.

While this practically ends the

official acts of the

Ohio Company relating to education, the

peculiar thing

10 Records of the Oio Company, Vol. II, pp. 50 65, 121.

11 Records of the Ohio Company, Vol. II, p. 91.

328

Ohi Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

is not that they were so few but that

there were any.

For that day the interest shown and the

appropriations

were no doubt unusual for a commercial

company. A

high regard or and a high estimate of

the importance of

education is ndicated. It is doubtful

if it can be dupli-

cated in many frontier communities.

Education at that time was largely a

matter of local

or even of individual concern in the

new country. It

could not well be otherwise in a

pioneer community.

However, a "beginnings" have

a peculiar interest for

all of us, we shall turn to the topic

of school legislation

and see what interest was taken in the

field of education

by the government in charge of the

territory of Ohio

before state food.

The Northwest Territory was under the

Governor

and Judges during the first stage of

territorial govern-

ment. During this time little was done

in the way of

school legislation. However, some

effort was made to

protect the school lands; for instance

in The Centinel

of the North-western Territory of Saturday, December

27, 1794, a notice appeared warning

against the cutting

down of trees on any section of land

reserved by the

Congress of the United States for any purpose.12

The

laws for the Territory in this period

were to be secured

by being adopted by the Governor and

Judges from the

codes of the older states. The

collections of laws of the

period show no school laws adopted for

the Northwest

Territory. This does not seem strange

however, when

one remembers that this was much before

the days of

public schools in the Territory. Even

though laws were

desirable or regulating the lands

granted for educa-

12 This notice was over the signature of

Winthrop Sargent, acting

governor, and appeared in a

number of other issues of the same paper.

Education in Territorial Ohio 329

tional purposes, the older states,

having no such lands,

had no such laws to adopt.

The territory entered on its second

stage of terri-

torial government in 1799 with the

first General Assem-

bly of the Territory holding its first

session in Cincin-

nati in that year. And although Judge

Burnet tells us,

that, "The subject of education

occupied their serious

attention," the members of this

Assembly did little real

legislating of an educational nature.

The author quoted

above informs us that, "Among

other measures, they

instructed the delegate in Congress to

use his influence

to induce that body to pass the laws

which were consid-

ered necessary to secure to the

Territory the title of the

lands that had been promised for the

support of schools

and colleges, including section No. 16,

in every town-

ship."13 One of the

other measures referred to was no

doubt a law passed providing punishment

for the of-

fense of destroying trees on school lands.14

An act of

November 27, 1800, of the second

session of the first

General Assembly, created a corporation

to manage the

school lands within the Ohio Company's

purchase in

Washington county.15 By this act seven

persons were

named as "trusteees for managing

lands granted for

Religious purposes and for the Support

of Schools",

within the Ohio Company's purchase.16

The purpose

of this law was to make the land more

productive and

thus provide means for fulfilling the

objects to which

13 Judge Burnet -- Notes, p. 305.

14 Eli T. Tappan, "School

Legislation," in History of Education in

the State of Ohio. Columbus, 1876.

15 This session of the Assembly was held

in Chillicothe.

16 Griffin Greene, Robert Oliver,

Benjamin Ives Gilman, Isaac Pierce,

Jonathan Stone, Ephraim Cutler and

William Rufus Putnam were the

trustees named.

330

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

such lands were dedicated. This act has

more to say

about the religious lands than the

school lands. The

fact that one section, number 29, was

in the town of

Marietta and hence desirable land for

immediate settle-

ment, possibly accounts for this. It

provided that va-

cant lots in this section might be

leased for not less than

three nor more than seven years and the

rent was not

to exceed five dollars. Three-fourths

of the clear profits

from section twenty-nine was to be used

to support

"such public teacher or teachers

of piety, religion and

morality as shall be employed". It

further provided

that the other one-fourth should be

held at interest until

it was sufficient to build one or more

houses of public

worship.17

Besides these acts the General Assembly

of the Ter-

ritory passed some measures relating to

the two town-

ships set apart for university purposes

in the Ohio Com-

pany's purchase. The first was a

resolution by the first

Session of the first General Assembly,

approved by the

governor December 18, 1799. By this

resolution a com-

mittee of three was designated and

requested to lay off

a town for a university in the most

suitable place in

townships eight or nine of the Ohio

Company's pur-

chase. The commission named laid off

and made a plat

of the town and reported back to the

first General As-

sembly at its second Session. An act

was passed by

this body approving the report and

recommendations

of the committee, December 6, 1800. In

accordance with

this Act the first session of the

Second General Assem-

bly passed an Act establishing a

University in the town

17 "Laws of the General Assembly

of the Northwest Territory, Vol.

II, pp. 8, 9.

Education in Territorial Ohio 331

of Athens, January 9, 1802. According

to this Act the

name was to be: "American Western

University". As

no organization was effected under this

act, it was su-

perseded by an Act of the State

Legislature in 1804.18

At first thought this might seem like a

rather meager

amount of legislation and little

related to the schools.

But when one remembers that this was

but a sparsely

settled territory to 1803 and that the

schools were pri-

vate and subscription schools and not

subject to any

public legislation, the few acts found

are rather to be

wondered at than depreciated. This is

the more true

when one considers that the first

general state laws re-

lating to common schools did not come

until the twenties

and the first compulsory common school

law in the late

thirties. (1838.)

However an account of the beginnings of

education

is concerned, primarily, with the early

schools. In this

field there was more than a start in

some sections of the

territory before 1803. Early schools

had opened and

reopened; the pioneer schoolmaster and

schoolmistress

had appeared; the pioneer type of

school architecture

had become established and dotted the

landscape here

and there in certain sections of the

old Northwest; yet

schools were more numerous than

school-houses.

An account of the early schools in Ohio

is neces-

sarily a little here and a little

there, a patchwork quilt of

the schools handed down from that day

to this. Neither

such an account nor such a quilt may be

a thing of har-

monious beauty in all of its parts, but

both may be of

tremendous interest and historical

value, especially in

18 Laws of the General Assembly of

the Northwest Territory, Vol.

II, p. 45; Vol. III, p, 161; Land Laws of Ohio, pp.

219, 220, 221.

332

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

so far as they may be assigned to

definite persons and

places. Besides the general interest

that everyone has

in originals and beginnings, there is a

peculiarly height-

ened interest to the comparatively few

who can recog-

nize in this piece of bright hue a

remnant of a dress of

a Gallipolis ancestress, or in that

piece of a more somber

shade, a part of the shawl or cape that

protected the

shoulders of a Marietta or Western

Reserve grand-

mother, or in that piece of Kentucky

homespun a re-

minder of a bit of early life of

Losantiville or of Mas-

sie's settlement, or can see in that

bit of jeans from

"Johnny Appleseed's" trousers

the beginning of fruit

culture in Ohio.

However, the interest in the patch-work

history of

the early schools should be of interest

and value to all;

for they were bits of the life of the

ancestors of all of

us. Such life and schools played a part

in shaping a

Jacksonian Democracy, a Clay and his

"War of 1812".

It is not my Garfield and my Lincoln

but our tow-path

boy and our rail-splitter. It is

certain that an unusual

percent of men of vigor and distinction

were products

of our early pioneer schools. May it

not be that those

schools, plus their environment, had

some elements of

strength in training for individuality

and initiative that

our modern schools plus a new

environment tend to get

too far away from?

In treating of the early schools of

Ohio, it is de-

sirable to give an account of actual

schools in some rep-

resentative sections such as about

Marietta, Cincinnati,

in the Western Reserve, the Virginia

Military Lands

and the like, and then see if it is

possible to arrive at

Education in Territorial Ohio 333

some generalizations concerning their

supporters, their

curricula, their teachers, their

buildings and their pupils.

The first schools in the state were

naturally in the

eastern and southern sections. No doubt

the earliest

schools were the Moravian Indian

Schools. One of

these dates from a period several years

before the Revo-

lutionary War. In 1761 Frederick Post

went from

Pennsylvania to the north bank of the

Muskingum, in

what is now Stark County, Ohio. Here he

built a cabin,

expecting to convert the Indians.19 In

1762 he returned

to the headquarters of the Society of

the United Breth-

ren in Pennsylvania and asked for an

assistant. The

Brethren made the request known to the

congregation at

Bethlehem and John Heckewelder, a youth

of about

nineteen years of age, voluntarily

agreed to go. Hecke-

welder in his "Narrative"

indicates that he went along

"principally to teach the Indian

children to read and

write".20 This mission

did not remain permanently but

others were established, particularly

after 1772, in what

is now Tuscarawas and also in Lorain

County.

David Zeisberger, trained for

missionary work in

the Indian school at Bethlehem,

Pennsylvania, was

prominent in the settlements made in

1772 and later.

While he and the Moravians in general

were chiefly in-

terested in converting the Indians to

their religion, they

seem to have used the fundamentals of

education as a

basis. Zeisberger in his

"Diary" frequently refers to

the unusual interest taken by the young

Indians in the

19 Henry Howe, Historical Collections

of Ohio, (2 volumes) Vol. 2,

pp. 607, 608. Published by C. J. Krehbiel & Co., Cincinnati, Ohio, 1904.

Copyright 1888 by Henry Howe.

20 Ibid. Vol. 2, p. 608. Howe quotes Heckewelder's "Narrative

of

the Missions of the United Brtheren

Among the Delaware and Mohegan

Indians."

334

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

school.21 The eagerness of the young

people for learn-

ing and their progress in the same, are

commented on

with satisfaction. It is worthy of note

that they cut

wood for the private use of their

teacher that his school

work might not be suspended

temporarily. (Such men-

tal activity on the part of the

twentieth century young

people would likely make it impossible

to celebrate so

many events and notables by the holiday

method.) If

one recalls the traditional amount of

liking the Indian

had for manual labor, a willingness to

chop wood may

be accepted as real evidence of his

interest in the school

and what he was learning there.

The earliest schools for white children

were those

established by the settlers of the Ohio

Company at or

near Marietta. However, there was one started about

the same time at Columbia. In spite of

the comparative

poverty, schools were started by the

earliest settlers at

Marietta. Instruction was given in

reading, writing

and arithmetic, and altho it is not

mentioned in the ac-

count here referred to, it is not

likely that spelling was

neglected.22 Hildreth says:

"no people ever paid more

attention to the education of their

children than the de-

scendants of the Puritans".23 The fact that schools

were started during the second year

after the arrival of

the colonists in a pioneer country

would lend color to

the statement. The first settlers

landed on the Mus-

kingum, April 7, 1788, and in the

summer of 1789, the

21 David Zeisberger, Diary of a

Moravian Missionary Among the In-

dians of Ohio. Cincinnati, 1885. Vol. 1, pp. 388, 451, 455, 461; Vol.

II,

pp. 4, 292, 438.

22 S. P. Hildreth, Pioneer History of

Ohio, being an account of the

Ohio Valley and the Early Settlers of

the Northwest Territory. (Chiefly

from original manuscripts), p. 335.

23 S. P. Hildreth, Pioneer History of

Ohio, p. 379.

|

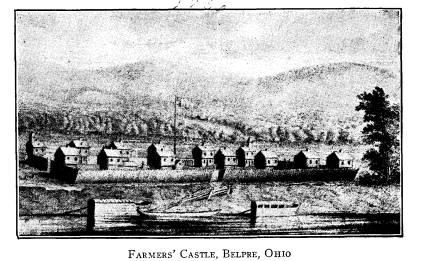

Education in Territorial Ohio 335 first school was opened in Bellepre, a settlement made on the Ohio about twelve miles below Marietta. Herein the great majority of the present-day teaching profes- sion has cause for rejoicing for this school was in charge of a schoolmistress, not a schoolmaster. Bathsheba Rouse, for such was her name, is believed to have been the first female teacher in Ohio. She was the daughter of John Rouse, who had emigrated from New Bedford, Massachusetts. She taught the smaller children of |

|

|

|

Bellepre during the summer of 1789 and several subse- quent summers.24 The school was held in Farmer's Castle, the fort of the settlement. Here in the first schools the custom, so common in pioneer days, of send- ing the smaller children to school in the summer months and the older children, especially boys, during the win- ter months was started. The weather and the paths and 24 " Howe, Historical Collections of Ohio, p. 779. Hildreth, Pioneer History, p. 379. |

336

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

the trails were in better condition for

the younger chil-

dren to make their way over in the

summer time, while

the work of clearing, planting and

taking care of the

crops made it undesirable to spare the

older children

from home during the seasons that such

work could

go on.

The larger boys and young women went to

school a

few months in the winter time.

Instruction was given

to them in the winter of 1789 and for

several winters

thereafter in Farmer's Castle, in

Bellepre, by Daniel

Mayo, who worked at clearing his land

during the sum-

mer months.25 Mr. Mayo came

from Boston in the fall

of 1788 with Colonel Battelle's family

and being a grad-

uate of Harvard University, no doubt

was well qualii-

fied to teach.26 Jonathan Baldwin, a

well educated

bachelor from New England, was another

of Bellepre's

early teachers. He kept school in

Blockhouse No. 3

while the garrison was confined,

fearing trouble from

the Indians.

Schools likewise started early in

Marietta. In 1789,

Major Anselm Tupper kept a school in

the northwest

blockhouse of Campus Martius, the

fortification at Ma-

rietta. Other early teachers at

Marietta were Mr. Cur-

tis, who taught two years in a cooper

shop; and Dr.

Jabez True, who kept school in the

blockhouse; another

was Benjamin Slocomb, a well educated

but rather dis-

sipated man of Quaker parentage.27

25 There are several spellings for

Bellepre. Belpre is also common.

Records of The Ohio Company uses Bellepre.

26 Daniel Mayo married the daughter of

Israel Putnam and after the

war of 1812 settled in Newport, Ky.,

where his descendants now live.

J. J. Burns, Educational History of

Ohio. (Historical Publishing Co.,

Columbus, Ohio), 1905, p. 23.

27 Hildreth, Pioneer History, p.

335.

Education in Territorial Ohio 337

In Waterford, up on the Muskingum,

schools were

also started early and kept most of the

time, especially

in winter. Joseph Frye and Dean Tyler

were liberally

educated men, who were employed at

different times as

teachers at Waterford or Fort Frye. The

Marietta

colonists had employed and brought with

them from the

east the Reverend Daniel Story as a

suitable teacher of

religious and educational training.28 No records seem

available to show the nature and extent

of the educa-

tional training offered by Mr. Story,

although as a min-

ister he served for years.

Likely the first school started in

southwestern Ohio

was the one begun in Columbia, now in

the East End of

Cincinnati, on June 21, 1790, by John

Reily. He is said

to have taught here in the first

school-house built in

Ohio.29 Reily had come from North

Carolina, altho he

was born in Pennsylvania. He had served

with Gen-

eral Greene in the Revolution. Judge

Burnet attests to

his character and ability.30 About a year

later Reily was

joined in his school venture by Francis

Dunlevy, who

had been born in Virginia, later moving

to Pennsyl-

vania. He also had fought in the Revolution,

chiefly

against the Indians. Reily taught the

English studies,

and Dunlevy, who is said to have been a

fine classical

and mathematical scholar, the

classical.31 The school

28 For details see Records of the

Ohio Company Vol. I, p. 39-40.

29 Chas. T. Greve, (A. B., L. L. B.), Centennial

History of Cincin-

nati, and Its Representative

Citizens, Vol. I, p. 180.

(Biographical Pub-

lishing Co., Chicago, Ill., 1904); David

Zeisberger: Diary. Has refer-

ence to schools and to roofing a

school-house earlier than this, 1788. Vol.

I, p. 388.

30 Burnet, Judge Jacob, Notes on the

Early Settlement of the North-

west Territory, pp. 469-478.

31 Both of these men became

prominent in early Ohio. Reily settled

in Hamilton in 1803. He was a member of

the Constitutional Convention

of Ohio. He served as clerk of the

Supreme Court of Butler County

Vol. XXXV--22.

338 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

was a subscription school and its

teacher "boarded

round" as Reily's journal shows

the following entries:

"In the month of August boarded

twelve days with Mr.

Patrick Moore; in the month of

September boarded

twelve days with Hugh Dunn; in December

boarded

with John McCulloch six days".

This school was later

changed into an academy. Judge

Goforth's Diary has

such references as the following in

regard to the matter:

"Last Monday night met at my house

to consult on the

expediency of founding an

academy." "Wednesday

night met at Mr. Reily's

school-house." The weather

was bad and few came, so they met the

next night at

Reily's to appoint a committee.32 Accordingly the

school developed into an academy under

the patronage

of Judge William Goforth, Rev. John

Smith, Major

John S. Gano and Mr. Dunlevy himself.33

The establishment of a fort in what is

now the down-

town portion of Cincinnati probably

caused the popula-

tion to tend to shift from Columbia. At

any rate, Mr.

Dunlevy moved up the Miami, is reported

to have taught

school near it, and in 1797 or 1798

opened a school a

short distance west of the present

location of Lebanon.

This was perhaps the first school in Warren

County.

While land had been sold here much

earlier, it is not

thought that a permanent settlement had

been effected

from 1803-1842. Francis Dunlevy removed

to near Lebanon in Warren

County in 1797. He served in the

Convention that drafted the State Con-

stitution as a member from Hamilton

County. He was a member of the

first legislature in 1803. At the first

organization of the judiciary he was

made presiding judge of the first circuit.

He held this place 14 years and

though this circuit embraced 10

counties, and though he frequently had

to swim his horse over the Miamies, it

is said he never missed a court.

He practiced law fifteen years after

leaving the bench then retired to his

books, dying in Lebanon in 1839.

McBride, James, Pioneer Biography,

Cincinnati, 1869. Vol. I, pp. 1, 100,

101.

32 Greve, Centennial History of

Cincinnati, Vol. I, p. 181.

33 Ibid., Vol. I,

p. 363.

Education in Territorial Ohio 339

until after Wayne's treaty with the

Indians in 1795. In

September of that year a settlement was

effected at

Bedle's station, where the only

blockhouse in the county

was built. Mr. Dunlevy later moved his

school to the

north-west about two miles and had some

of the same

scholars. Among his young hopefuls in

the vicinity of

Lebanon was a black-eyed boy, who gave

his age as four

years and his name as Thomas Corwin. No

doubt it

was a belated but pleasant reward to

this pioneer teacher

when this pupil became governor of Ohio

and later a

United States senator, while a fellow

pupil, John Smith,

also attained the latter honor. There

were other early

schools in this section, namely, one

about 1800 taught

by Judge Ignatius Brown, one near

Ridgeville about

1801 to 1803 by Matthias Ross, one

about Waynesville

in 1802 taught by Rowland Richards and

one in Leb-

anon in 1801, 1802 and 1803 by Enos

Williams, a for-

mer pupil of Francis Dunlevy, and

perhaps others prac-

tically this early. Thus Warren County

seems to have

been almost the educational center of

Southwestern

Ohio and the Symmes purchase before

statehood.34

There is also evidence of early schools

near what

is now the down town part of

Cincinnati, altho infor-

mation about them is frequently

incomplete. William

D. Ludlow, writing in 1856, referred to

a school on the

river bank opposite Main and Sycamore

streets. This

school was taught by an Irishman by the

name of Lloyd.

Elsewhere there is reference to the

first school being

erected in 1792, and attended by about

thirty pupils.

This is supposed to have been in a log

cabin about 3rd

34 Jas. J. Burns, Educational History

of Ohio. (Historical Publish-

ing Co., Columbus, 1905), p. 24; History

of Warren County, Chicago,

1882, pp. 261, 477, 570.

340

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

and Lawrence and could be the school to

which Ludlow

referred. When Judge Burnet arrived in

Cincinnati, in

1795, a frame school building stood on

the north side of

Fourth Street opposite where St. Paul's

church later

stood. It was inclosed but not

finished. It is also re-

corded that the Presbyterian Church was

used for a

school for a time. Jonathan Lyon, who

came to Cin-

cinnati in 1791, attended school in a

cabin near Riddle's

blacksmith shop. This shop stood on the

public land-

ing and hence this school could also

have been the one

about which Ludlow wrote.

Kennedy Morton was

Lyon's teacher and was a great believer

in the use of

the rod. "He frequently whipped grown

young men

and women with a long hickory gad until

they would

fairly jump off the floor."35

Such are some of the general and

indefinite accounts

of early Cincinnati schools. These were

no doubt the

general schools for the teaching of the

three R's. Such

schools were rather few in early

Cincinnati, as there

was more of a tendency to a specialized

type of school

in this vicinity, as will be indicated

below by newspaper

advertisements. S. S. L'Hommedieu tells

us that in

1810, 1811, 1812 there were but three

or four small

schools in Cincinnati. One was in the

second story of

a building at Sixth and Main kept by

Thomas H.

Wright; another, John Hilton's, over a

cabinet-maker's

shop on the east side of Main Street

between Fifth and

Sixth; a third was that of David

Cathcart on the west

side of Walnut near Fourth Street.

There were about

forty scholars in each.36 That these

schools were not

35 Greve, Centennial History of

Cincinnati, Vol. I, p. 363.

36 S. S. L'Hommedieu,

quoted in Greve's Centennial History, Vol. I,

p. 491.

Education in Territorial Ohio 341

housed in buildings built for the

purpose is also a point

worthy of notice as a reflection of the

general attitude

of the community toward education. We

shall next con-

sider the schools of Cincinnati as

indicated by adver-

tisements in the early papers.

The earliest newspaper published in

Cincinnati was,

The Centinel of the

North-western Territory. The

available files of this paper show only

two or three ad-

vertisements relating directly to

schools. The earliest

of these advertisements is so

suggestive of the type of

school it was proposed to start, that

it will be quoted

in full. It is from The Centinel, bearing

the date of

Saturday, Jan. 3, 1795.37

The Subscriber begs leave to inform the

public that he in-

tends to open school on Monday the 22d

of this inst. in the house

lately occupied by David Williams,

nearly opposite James Fer-

guson's store, where he proposes to

educate youth in the fol-

lowing sciences and mathematical

branches, viz.: reading, writing,

arithmetic, bookkeeping, trigonometry,

mensuration of super-

ficials and solids, dialing, gauging,

surveying, navigation, ele-

ments of geometry and algebra. The

parents and friends of all

such as are committed to his trust, may

depend on his utmost

care and best endeavors to form their

tender minds to a love of

learning and virtue; he likewise will

employ every opportunity

in grounding his pupils in the practical

parts of the above.

--STUART RICHEY.

The writer has found nothing to

indicate the prog-

ress of the school, or to show how well

this rather heavy

mathematical curriculum was patronized.

However,

Mr. Richey again advertised the same

subjects eleven

months later, December 5, 1795. It was

stated that

37 The Centinel of the

Northwestern Territory, published in

Cin-

cinnati, Ohio, Vol. II, No. 60, Sat.,

Jan. 3, 1795. (Price per year 250 cents,

7 cents per copy). Files of this paper

from Nov. 23, 1793 to May 14, 1796,

are found in the Library of the Hist.

and Phil. Society of Ohio, located

in the building with the library of

Cincinnati University.

342

Ohio, Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

school would open the 16th of the month

and that no

more than thirty scholars would be

admitted. It is in-

teresting to note that this time an N.

B. is added, stating

that, "None need apply but such as

allow of moderate

correction to be used in said school

when necessity re-

quires it."38 One might wonder if this was a result of

experience the previous winter. As this

same advertise-

ment appeared in this and five subsequent

issues of the

Centinel, one surmises that the limit of thirty was put

in as much to hurry registration as to

limit it. Evi-

dently these schools of Mr. Richey,

were of a rather

special type, if we may judge by his

advertisements, and

were secondary as well as elementary in

subject matter.

Of course those elements of the

curriculum relating to

surveying and navigation were intensely

practical in a

new country and on the Ohio.

The advertisements of "The

Western Spy, and

Hamilton Gazette", between May 28, 1799 and Janu-

ary 1804, bring to light a number of

prospective schools

of various kinds.39 In the issue of

September 17, 1799,

Francis Mennessier announced the

opening of both "A

Coffee House" and a schoo.40 Both

were to be on Main

Street, Cincinnati, at the sign of

"Pegasus the bad Poet

fallen to the ground". He was

going to teach French

to those caring to learn, on each

evening in the week ex-

cept Saturday and Sunday, from 6 to 9

o'clock P. M.

Mr. Mennessier evidently had taught

French before, for

he informs those who has been

subscribers for two

38 The Centinel, Vol. III, No. 107, Saturday, December 5, 1795.

39 "The Western Spy and Hamilton Gazette," was the

successor of

"The Centinel of the

Northwestern Territory." Files of

this paper (pub.

in Cincinnati) between the dates

indicated are to be found in the Mercan-

tile Library, Cincinnati, Ohio.

40 Ibid. In this and other Sept. 1799, issues of the paper.

Education in Territorial Ohio 343

years and had not been able to attend,

that they will be

instructed gratis if they care to

attend. The rates of

the school are not known, so it is not

possible to deter-

mine whether a partially philanthropic

French school

was expected to benefit an economic

coffee house. Later

in the same year, James White, used the

same news-

paper to announce the removal of his

school to a new

location. This was a subscription

school but non-sub-

scribers are told their scholars will

be admitted on the

same terms as those of subscribers. Mr.

White also

announces that he will open an evening

school, in which

writing, arithmetic, etc., will be

taught. The school is

to be open four evenings a week from

six to nine o'clock

for a period of three months; the terms

are to be two

dollars for each scholar, and the

scholars are to find

their own firewood and candles.41

In 1800 Lemuel McDonald advertises a

school that

he has recently opened. His purpose is

to instruct youth

in the various branches of English

literature and he

promises to carefully attend to the

morals of those in-

trusted to his care. He announces that:

"He will teach

reading, writing, arithmetic, English

grammar, geogra-

phy and the mathematics, in the most

concise and fa-

miliar manner".42 Evidently

this was primarily an ele-

mentary school.

Two names appear rather frequently

between 1800

and 1803 in connection with educational

announcements;

others usually only once or twice. Those names are

Matthew G. Wallace and Robert Stubbs.

While the

main work of the latter in this field

was likely in con-

41 The

Western Spy, October 22, 1799. The

advertisement is re-

peated in subsequent issues.

42 The Western Spy, September 24, 1800.

344 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

nection with the "Newport

Academy", it was so closely

affiliated with Cincinnati as to make

it desirable to men-

tion it here. An early announcement in

regard to the

same appeared under the heading,

"Newport Academy",

and over the signature of Washington

Berry, chair-

man of the trustees of that

institution.43 A part of the

advertisement will be quoted, in order

to show the va-

riety of the curriculum offered.

Elementary as well as

secondary subjects were to be given.

The Academy of Newport will commence on

the first of

April. The Rev. Robert Stubbs is

president of said academy,

in which will be taught reading,

writing, and arithmetic at eight

dollars per annum; -- also the English

grammar, the dead lan-

guages, the following branches of the

mathematics, viz.: geome-

try, plain surveying, also by latitude

and departure, navigation,

geography, astronomy, mensuration of

superficials and solids;

also logic, rhetoric, bookkeeping, etc.,

at four pounds per an-

num.45

It was further announced that board

might be ob-

tained in Newport and vicinity on

reasonable terms and

"the greater part received in

produce". In August, 1802,

a notice of a meeting of the

proprietors of the school

taught by Mr. Stubbs appeared in the Spy.44

Later in

the same year, Mr. Stubbs announced his

intention to

open a night school in Cincinnati on

the following Mon-

day night at six o'clock. Instruction

is to be offered in

any science or language that a youth

"is capable of, on

accommodating terms". Each Friday

evening is to be

appropriated to the study of Geography

and the use of

43 The Western Spy, May 28, 1800. The trustees are given in the

advertisement, viz.: Washington Berry,

Charles Morgan, John Grant,

Thomas Kennedy, Thomas Sanford, Thomas

Carneal, Richard Southgate,

Daniel Mayo, Robert Stubbs and Bernard

Stuart. They were to attend

to the regulations and management of the

Academy.

44 The Western Spy, August 14, 1802, (Vol. IV, No. 159').

Education in Territorial Ohio 345

the Globes. Mr. Stubbs also promises by

a simple piece

of machinery to "exhibit the

earth's diurnal and annual

revolutions; and of course the cause of

that pleasing

variety of the seasons of the year, and

why the days

increase by months within the limits of

the Polar Cir-

cles".46 He also

promises to exhibit upon the shortest

notice to any select party of ladies or

gentlemen who

may be curious enough to pry into such matters.

In

January, 1803, Mr. Stubbs is again

before the public

to let them know that his Academy in

Newport will re-

open the first of the following month.

He thinks it un-

necessary to say more than that

"he will not deceive

those who may honor him with the

tuition of their

sons". The notice adds that

boarding is cheap in "New-

Port".45

Mr. Stubbs seems to have taken

advantage of quality

advertising as well as announcement

advertising, for, in

the issue of The Spy for January

26, 1803, Matthew G.

Wallace, John S. Gano and five other

men attest to hav-

ing attended some exercises recently

given by the pupils

of Mr. Stubbs' Academy in Cincinnati.

These men at-

test that the several pupils present,

considering the time

they had been under Mr. Stubbs' care,

gave "proof of

growing proficiency in the English and

Latin lan-

guages -- and particularly in English

grammar, and

oratory and the mathematics",

proofs that were a credit

to themselves and an honor to their

instructor.46 Mr.

Stubbs does not seem to have conducted

a pay-before-

you-receive business, for later in 1803

he puts a notice

45 The Western Spy. Nov. 10, 1802. (No. 15 of Vol. IV and No.

171 of series). This advertisement has

the caption, "Science."

46 Very likely this was the school where

the use of the globes was to

be a regular Friday evening feature.

346 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

in the paper to thank those who have

paid the last year's

tuition and to warn those who have not,

that he will put

the law in force, since he has already

solicited them fre-

quently.47 Evidently there were some

salary difficul-

ties even before the time when the

teacher became a

servant of the public, and before the

time of the public

school system.

Matthew G. Wallace, whose name is also

frequently

attached to advertisements relating to

schools during

this period, seems also to have been a

Reverend, as was

Mr. Robert Stubbs. An early

advertisement of his is

headed "Education" and

appears in the issue of The Spy

for October 31, 1801, and in the three

following issues.

According to his advertisement, Mr.

Wallace proposed

to instruct a few boys in the Latin and

Greek languages

and if required, parts of literature

nearly connected with

them. He suggests that the school will

likely not open

before the first of December, as it

will take some time

to get suitable books. Mr. Wallace has

a "selling" para-

graph in his advertisement which runs

as follows:

It is presumed unnecessary here to

enumerate the many ad-

vantages naturally resulting from an

institution of this kind;

particularly in this new country and at

so early a period. It must

be acknowledged that the talents of

many youths among us are

now buried and neglected, which a

proper cultivation would ren-

der eminently useful. Besides, it is

education only which digni-

fies human nature, consolidates social

blessings, and prepares us

for our proper duty and happiness, the

glory and enjoyment of

God.

Mr. Wallace also states that he will

pay proper at-

tention to public speaking, as that is

a necessary orna-

ment of every man of letters. To

prevent after reflec-

47 The Western Spy, May 11 and 18, 1803.

48 The Western Spy, October 31,

1801.

Education in Territorial Ohio 347

tions he states that not more than six

boys will be re-

ceived for the present and that the

first applying will

be accepted.

Somewhat over a, year later Mr. Wallace

in an ad-

vertisement of some length, again

informs the citizens

in and near Cincinnati that he proposes

to open a school.

He proposes a somewhat wider curriculum

this time, for

besides the languages and the parts of

literature usually

included in a classical education, he

proposes to teach

reading, writing, the different

branches of the mathe-

matics, etc. A strict examination,

followed by public

speaking, is proposed for the end of

each quarter. His

advertisement implies that a building

had been provided

for the school by a group of interested

persons, for "the

proprietors of the school-house",

are urged to make

known the scholars they propose to send

for fear the

school might be over-crowded and thus

it would be in-

advisable to admit more. The subscriber

in his adver-

tisement presumes, "that all who

wish to see our new

state flourish, our citizens respected

and happy, will suf-

ficiently encourage an institution of

this kind."48 In

November of the same year, Mr. Wallace

informs the

proprietors and citizens in general

that another quarter

of his school has just commenced, and

that tuition will

be as formerly.49

In the previous July, Mr. Ezra Spenser

had availed

himself of the columns of The Spy to

announce that the

concurrence between himself and the

Rev. Matthew

Wallace would be discontinued. He

announces that he

will open a "regular English

school", when enough

48 The Western Spy, January 5, 1803, repeated in the issues of Janu-

ary 12 and 19. The school was to open on

Monday, the 10th of January.

49 The Western Spy, Oct. 19, 1803. Nov. 5, 1803.

348

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

scholars are obtained, in which he will

teach reading,

writing, arithmetic and English

Grammar. From the

use of the word "regular"

before English, in the phrase

regular English school, we are perhaps

justified in con-

cluding that Mr. Spenser was not

entirely pleased with

Mr. Wallace's languages and literature

that usually go

to make up a classical education or the

"dead lan-

guages" as they are called in one

of Mr. Stubbs' adver-

tisements. Likely Mr. Spenser was the

practical edu-

cator of his day.50

Neither did the schoolmaster escape the

"want-ad."

column in the early days. Robert Benham

advertises

for a schoolmaster capable of teaching

an English

school. Mr. Benham mentions no salary,

simply stating

that such a person will meet with good

encouragement

by applying at his place on Turtle

Creek, two miles

above Deerfield. A little over a year

later, Mr. Benham

has another advertisement in The

Spy, headed "A Good

Schoolmaster Wanted".51 It

indicates that he is wanted

at the new school-house on the

subscriber's farm in

Warren County. In the same issue of The

Spy, under

the caption "School", the

following also appeared: "A

Schoolmaster is much wanted at this

place; a person

qualified to teach an English school

will find employ-

ment. Apply to W. C. Schenck,

Franklin". It is inter-

esting to note, as illustrative of the

change of feeling of

the general public that has come about,

that Mr. Ben-

ham in his first "want-ad."

for a schoolmaster also an-

nounces that he has for sale four

stills of the following

capacities: 125, 107, 80, and 65 1/2

gallons, thirty mash

50 Ibid., July 6, 13, 20, 1803.

51 The Western. Spy, Aug. 17, 1803. The distance from Deerfield has

increased one-half mile above

that of the previous advertisement.

Education in Territorial Ohio 349

tubs and 12 singling kegs. Such economy

in advertis-

ing would hardly be approved at the

present time.

General articles on education are very

few in the

newspapers in which the above

advertisements were

found. The two or three, which are

found, are general,

and mostly quoted, and they do not

concern local edu-

cation directly. The following

quotation, requoted from

a periodical, will give the spirit and

suggest the content

of such articles.52

Delightful task! to rear the tender

thought,

To teach the young idea how to shoot,

To pour the fresh instruction o'er the

mind,

To breathe the enlivening spirit and to

fix

The generous purpose in the glowing

breast.

THOMSON.52 53

Nor were these all, for there is

evidence of schools

in early Cincinnati that were less

academic than the

foregoing. As early as 1801 Levi M'Lean

uses the col-

52 The Western Spy, Sept. 25, 1802. The quotation is quoted in the

article referred to. Aug. 14, 1802.

Column article. These articles are

signed "Senex."

53 It will be interesting to turn aside

for a moment to note a change

that came about in the make-up of

educational advertisements in the pioneer

newspapers that have been referred to

previously in this article. No doubt

a similar transition can be discovered

in the advertisements in general. In

the earlier paper, "The Centinel

of the Northwestern Territory," the adver-

tisements in regard to schools are

headed, "The Subscriber" or "The Sub-

scriber Begs"; thence reading on

into the body of the advertisement. (The

Centinel, Jan. 3, 1795 and Dec. 5, 1795.) The heading gave no

hint of the

nature of the notice, and this is quite

the usual way for the various adver-

tisements to start. No doubt this was

found quite satisfactory in the early

newspapers at a time when reading matter

was very scarce, for each sub-

scriber would read every word anyhow.

However, a little later the adver-

tisement in The Western Spy and

Hamilton Gazette, 1799 to 1804, show

that a change had taken place. The

heading now usually indicates the

nature of the notice. Here are some

headings of school advertisements of

this period: "Newport

Academy," "Education," "Wanted: a Schoolmaster,"

"School for Young Ladies,"

"Science," "Singing School." (The Western

Spy, May 28, 1800; Oct. 31, 1801; June 12, 1802; July 31,

1802; Nov. 10,

1802; Oct. 22, 1799.) The heading is no

longer a part of the first sentence.

A step forward has been made; the

purpose is to make the reader's task

more easy and to catch the eye of those

to whom the announcement might

be of special interest.

350 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

umns of the local paper to announce

singing schools for

"Ladies and Gentlemen". One

singing school is to be

held at Mr. Washburn's school and

another at the Court

Room at Mr. Avery's as soon as court is

over. The

rates are one dollar for thirteen

nights or two dollars

per quarter, the subscribers to furnish

their own wood

and candles. This was no doubt a

side-line or an avoca-

tion for the "singing

professor", for elsewhere it is re-

corded that Mr. M'Lean was a butcher by

trade. Nor

were these his only activities, for Mr.

Greve gives him

credit for making the first political

stump speech in Cin-

cinnati in connection with a campaign

for constable in

1802.54

Perhaps a somewhat more interesting and

unusual

non-academic school was the

"Dancing School" as pro-

claimed in "The Western

Spy" about two years before

this, (Nov. and Dec., 1799). Mr.

Houghton advertises

his dancing school with some gusto as

follows:

DANCING SCHOOL

The Subscriber having taught with great

reputation in dif-

ferent parts of Pennsylvania and

Virginia, last winter and spring,

and whose letters of introduction to

this place and Lexington,

are most respectable, begs leave to

inform the ladies and gentle-

men of Cincinnati and its vicinity, that

if honored with their

patronage, he intends opening a school

here as soon as sufficient

number (sixteen or more scholars) shall

subscribe. He teaches

particularly, the Minuet, Cotillion,

French and English Sets, in

all their various and ornamental

branches. Exclusive of which,

he teaches the most fashionable Country

Dances and City Cotil-

lion, taught in New York, Philadelphia,

and Baltimore. His

terms are three dollars entrance, and

five at the expiration of the

quarter.55

54 The

Western Spy, Oct. 31, 1801.

55 The Western Spy, Nov. 19, 1799, Dec. 3, 1799. Mr. Greve in re-

ferring to the incident in his Centennial

History surmises that Mr. Hough-

ton did not pay for his advertisement,

as a bitter tirade against dancing

Education in Territorial Ohio 351

Mr. Houghton adds some postscripts

which an-

nounce that he also teaches some

favorite Scotch Reels,

that the school will commence this

morning, Nov. 19,

1799, at ten o'clock, and further that

he will teach from

seven to nine o'clock in the evening

for the benefit of

gentlemen, whose occupations will not

permit them to

attend during the day. It is likely

that this was the

earliest school of this kind in the

state, for Cincinnati

was the most cosmopolitan of the early

settlements, hav-

ing colonists from widely different

sections of vary-

ing types. Such a school would hardly

have been looked

upon with favor at Marietta, a fairly

unified Puritani-

cal settlement.

In this early day it was rather

generally regarded

as unnecessary to educate girls in the

academic subjects

to the extent that boys were, while no

doubt, it was

rather desired that they should have

some knowledge

of the three R's. In this connection it

is interesting to

note that a "School for Young

Ladies" was advertised

by a Mrs. Williams, July 31, 1802, to

be held in a house

lately occupied by a saddler on

Sycamore Street. The

"Young Ladies" were to be

instructed in reading, writ-

ing, sewing, etc., at the rates of two

dollars and fifty

cents per quarter for reading, three

dollars and fifty

cents per quarter for reading, sewing

and writing.56

This school has been referred to as the

first school for

appears in The Western Spy a

little later on. This is rather hard to

determine as editorials were not used in

the papers of that day, and the

article could have been general as well

as editorial. Then some of the

more puritanical subscribers might have

buttonholed the editor.

56 The Western Spy, July

31, 1802, issue No. 157, (No. 1 of Vol. IV).

Aug. 14, 1802.

352 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

higher education of young women in the

Ohio valley.57

The curriculum proposed would hardly

justify the con-

clusion; but the school is advertised

for young ladies,

and the "sewing, etc."

represents the first department in

a school for young ladies in a day when

they were of-

fered a less academic and more

practical training, if

they were offered anything in school

outside of the bar-

est rudiments of an education. In this

sense Mrs. Wil-

liams was proposing a school for the

higher education

of women. As for co-education in the

college field that

comes later, at least much credit in

that field has been

claimed by sponsors of Oberlin, which

was established

in 1833. Mr. Mathews says that,

"Oberlin carried co-

education to a convincing success with

a rush", while

Mr. Cherry gives Oberlin credit for

being the first co-

educational college in the world.58 On

the other hand,

some "firsts" in this field

have been assigned, by Mr.

Gard, writing in the "Ohio

Archaeological and Histori-

cal Society Publications", to Robert Owen's communistic

colony on the Wabash. Pestalozzian

principles were

used in the schools of this colony, and

were introduced

there soon after the colony was founded

in 1826. Mr.

Gard says, "The New Harmony

schools were the first

public schools in the United States to

offer the same

advantages to girls as to boys."59

The doctrine of equal

57 Ohio Archaeological and Historical

Society Publications. (Pub.

for the Society at Columbus, Ohio, 'by

Fred J. Heer) Vol. 25. The Higher

Education of Women in the Ohio Valley

Previous to 1840, by Jane

Sherzer,

Vol. 25, p. 2.

58 Alfred Mathews, Ohio and Her

Western Reserve, pp. 196-200;

(With a Story of Three States, D.

Appleton & Co., 1802.)

P. P. Cherry--The Western Reserve and

Early Ohio (Pub. by R. L.

Fouse, Firestone Park, Akron, Ohio,

1921.) p. 106.

59 Ohio Archaeological and Historical

Society Publications -- Vol. 25,

p. 32. European Influence on Early

Western Education. Willis L. Gard,

also quoting Lockwood on "New

Harmony Movement."

Education in Territorial Ohio 353

educational opportunities regardless of

sex is given as

a principle of Mr. Owen's system.60

While the settlements in the

southeastern and south-

western parts of Ohio were earlier,

there were other

settlements sufficiently long before

statehood to make a

survey of school beginnings in them

desirable. One of

these was the south central region or

Virginia Military

District and another of course the

Western Reserve in

Northern Ohio.

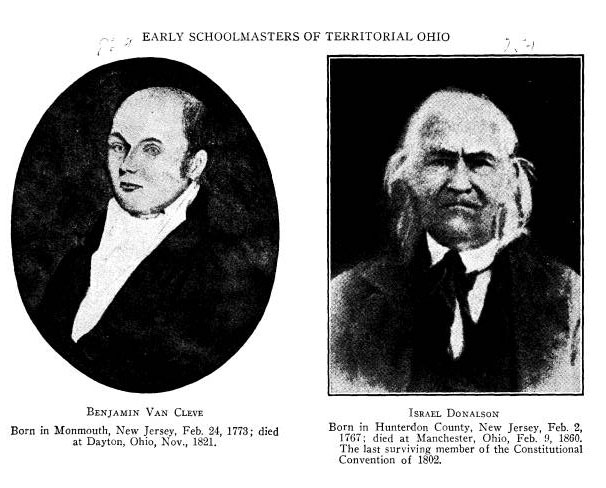

The first settlement in the Virginia

Military lands

and sometimes referred to as the third

in the state, was

made at Manchester, (Adams County), in

1790 or 1791,

by Colonel Nathaniel Massie and his

followers. This

man and associates accounted for many

surveys and set-

tlements in this section of the state.

This early settle-

ment at Manchester had its first

school-house in 1796,

(some say in 1794), with Israel

Donalson as teacher

for several terms. One of the first

female teachers in

this section was Mrs. Dodson, an Englishwoman,

who

taught in Liberty Township on Zane's

Trace about

1803.61 Other early

schools appeared at settlements

along this early and noted trail as

well as elsewhere in

this district. A school is reported in

Brown County in

60 It may not be out of place to observe

that a little more than a

quarter of a century after 1803, Mrs.

Trollope found many schools in

Cincinnati and "perceived, with

some surprise, that the higher branches

of science were among the studies of the

pretty creatures" in one of these

schools at least. She observed one

"lovely girl of sixteen," who "took her

degree" in mathematics, while

another was examined in moral philoso-

phy. By this time at least a higher academic

education was provided for

women. However, Mrs. Trollope thought

that it might have been difficult

for a far better judge than she to

determine to what extent young ladies,

who "blushed so sweetly, and looked

so beautifully puzzled and con-

founded," merited the diplomas they

received. Mrs. Trollope, Domestic

Manners of the Americans. London, New York, (Reprint) 1832, p. 81, or

Vol. I, pp. 114-115.

61 Nelson W. Evans and Emmons B. Stivers -- A History

of Adams

County, West Union, 1900. Passim.

Vol. XXXV -- 23.

|

(354) |

Education in Territorial Ohio 355

1800 and another about 1802, while

Highland County

had early schools at scattered centers

at dates estimated

at 1802 and 1803. Early settlements in

these counties

range from 1796 to later dates.62

Ross County, which furnished

Chillicothe as one of

the territorial seats of government and

later as the

first state capital, had numerous

settlements between

1795 and 1800. A school was kept here

in the last of

the 1700's by a very good schoolmaster

of Irish extrac-

tion. One or two others are reported in

the county be-

fore 1803. In laying out Portsmouth,

Massie dedicated

lots 130 and 143 to school purposes, a

practice, by the way,

that was quite common in surveying and

platting early

town sites. These lots in Portsmouth

were later used

for school purposes, but the only

school the writer has

found recorded for Scioto County before

Statehood was

one at or near Alexandria, said to have

been as early as

1800. Pickaway and Franklin Counties

were settled

in different localities between 1796

and 1798, but seem

not to have had schools till 1803 or 4

or later. In fact,

dates for early schools in the Virginia

Military District

are more often given around 1808 to

1810 to 1812, and

particularly from 1815-1818.63

In the Western Reserve in northern and

north-east-

ern Ohio, we again find settlers of the

New England

stock predominating. French traders and

missionaries

and others had earlier frequented the

region, but do not

62 Chief references are the County

Histories. See Bibliography.

Evans and Stivers. Adams County, under

Manchester, Liberty Twp., etc.;

Brown County, pp. 1, 463, etc.; Franklin County, pp. 261, 419,

and under

Townships.

63 Chief references are the County Histories.

See Bibliography.

History of Ross County, p. 189, Townships; Franklin County, pp. 361,

419;

Highland County, Madison, White Oak, and Marshall Twps.

356

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

seem to have left anything in the way

of schools. And

indeed, there were few schools in this

section of the

state before 1803. The greater number

of authorities

give 1802 as a date for the beginning

of schools in the

environs of Cleveland and perhaps of

the Western Re-

serve. However, there is inexact

reference to a school-

house being built on the road, near

Kingsbury's and

taught by Miss Sarah Doan, daughter of Nathaniel

Doan, as early as 1800. One of the

schools of 1802 was

conducted for the benefit of about a

dozen in the "front

room" of Major Carter's by Miss

Anna Spafford. The

curriculum provided merely the simplest

form of book

knowledge. Another school of the same

year was that

at Harpersfield by Abraham Tappan. With

schools be-

ginning about 1802, naturally rather

little was accom-

plished in this region of the state

until after statehood.

As settlers became more numerous and

settlements suf-

ficiently compact, (and that was

separation by miles in

many cases,) this section of the state

took an active in-

terest in things scholastic. The

western part of the

Western Reserve, known as the

Firelands, had its edu-

cational beginnings in the next period

of development.64

The beginnings of education in the

section of Ohio

heretofore surveyed are no doubt much

more than rep-

resentative. Of course there were a few

other begin-

nings in adjoining or outlying

settlements. The settlers

of the Ohio Company who had gone to

settle about the

64 James Harrison Kennedy -- A History

of the City of Cleveland,

Its Settlement, Rise and Progress,

1796-1896. Cleveland MDCCCXCVI,

pp. 112, 114; Elroy McKendree Avery, A

History of Cleveland and Its

Environs, The Heart of New

Connecticut, in 3 vols. Chicago and

New

York, 1918, Vol. I, p. 47, p. 341; Jesse

Cohen, "Early Education in Ohio"

in Milgazine of Western Hist., Vol. III (1885-6) Cleveland, pp. 217-223;

Harvey Rice, Pioneers of the Western

Reserve. Lee & Shepard, Boston,

1883, pp. 68-9.

Education in Territorial Ohio 357

two college townships in Athens County

had established

one or two schools before 1803; and by

1800 Benjamin

Van Cleve had started the educational

history of Day-

ton in a blockhouse made of round logs,

which stood on

the present site of the soldiers'

monument. He thus

records the event in his journal:

"On the 1st of Sep-

tember I commenced teaching a small

school. I had

reserved time to gather my corn, and

kept school until

the last of October".65 Then there

were a few schools

elsewhere, such as in Jefferson County,

which in early

days took in a number of counties in

the eastern part of

Ohio. A log school-house was built in

what was later

Belmont County, as early as 1799, which

pupils attended

from considerable distances and

sometimes at consider-

able risks. Another school was started

near St. Clairs-

ville in 1802. A large number of the

settlers in this sec-

tion of the state were from

Pennsylvania and Virginia,

and according to a local historian much

interested in

educational affairs and schools.66

Some general observations on the

beginnings of

schools in the various sections of the

state will help to

account for the conditions found there.

Some compara-

tive statements and conclusions will indicate

how educa-

tion reflects the settler and his

interests. So we shall

summarize the actual school conditions

by beginning

with the last regions treated and

ending with the Ma-

rietta and Cincinnati districts. Then

we shall turn to a

brief consideration of early

schoolmasters, school-

houses and equipment.

65 Robert W. and Mary Davies Steele, Early

Dayton, 1796-1896.

U. B. Publishing House, Dayton, Ohio,

189,6, p. 34.

66 W. H. Hunter, The Pathfinders of

Jefferson County, in Ohio

Archaeological and Historical Society

Publications, Vol. 6, pp. 246, 247,

passim; C. M. Walker, History of Athens County, Ohio. 1869,

p. 219.

|

358 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications The comparatively few schools in the Western Re- serve were due to the late settlement, rather near 1803 and to scattered settlements rather than to the type of settlers; for the settlers in this section were rather uni- fied as to type and mostly New Englanders. On the other hand, there were numerous settlements in the Vir- |

|

|

|