Ohio History Journal

BRIAN P. BIRCH

A British View of the Ohio

Backwoods: The Letters of James

Martin, 1821-1836

Although the British formed a sizeable

minority of the early farm

settlers in Ohio, very little is known

about them.1 A few accounts ex-

ist of particular British, notably

Welsh and Scots, "colonies," but

with no language barrier to separate

them from the broad tide of

American settlers moving across the

Appalachians in the early nine-

teenth century, the British were

largely absorbed into that stream

and left behind few tangible records.2

The paucity of evidence about British

settlers and their impres-

sions of the Ohio farm frontier gives

some significance to a collection

of letters written between 1821 and

1836 by James Martin, an immi-

grant from London who settled to farm

near Bucyrus, Crawford

County.3 Not only are these

letters of some interest in providing first-

hand accounts of the perils of the

Atlantic crossing, of the toil of the

Brian P. Birch is Senior Lecturer in

Geography at Southampton University, England.

1. There are no texts specifically on

British farm settlers in Ohio although some ref-

erence can be found to them in Mary L.

Ziebold, "Immigrant Groups in Northwestern

Ohio to 1860", Northwest Ohio

Quarterly, 17 (April-July, 1945), 62-71.

2. Studies of a Welsh and a Scottish

group settlement in Ohio include Stephen R.

Williams, The Saga of Paddy's Run (Oxford,

1972), and Andrew Gibb, "A Scottish

Venture in the United States: the

Glasgow Ohio Company, 1824," Scottish Historical

Review (forthcoming). Some information on George Courtauld's

1818 Englishtown set-

tlement in Athens County can be found in

Charles M. Walker, History of Athens Coun-

ty, Ohio (Cincinnati, 1869), 544. Studies of individual British

immigrants to the state

include James H. Rodabaugh, "From

England to Ohio, 1830-1832: The Journal of

Thomas K. Wharton," Ohio

Historical Quarterly, 65 (January, 1956), 1-27, 111-51. The

archives of the Ohio Historical Society

contain a few sets of letters written by British

settlers in Ohio; for example, the

letters of Scottish immigrant Charles Rose written in

1822 and 1830 from Wellsville,

Columbiana County, Ohio.

3. The letters of James Martin to Mrs.

Caroline Monro and Mordaunt Martin Mon-

ro, 1815-1836. Greater London Record

Office, 40 Northampton Road, London EC1R

OAB, Item No. GLRO Acc. 1063/130-150,

twenty-one parts. Because these letters were

taken into the archive under local

government amalgamation, no record exists of their

date or form of deposition, but they are

quoted here with the permission of the Great-

er London Council, the governmental

authority for the metropolis.

140 OHIO HISTORY

wagon journey west in search of suitable

land, and of the difficulties

of establishing oneself on the frontier

amongst people to whom one

felt largely alien.4 They are

also of value in illustrating three traits

common to other British settlers on the

midwestern farm frontiers.

First, like many others who left England

to farm in the Midwest,

James Martin came with almost no prior

knowledge of farming, and

particularly of farming in the

backwoods, so that he greatly

underestimated the problems of making a

living from the land, with

the result that even after fourteen

years in Crawford County most of

his quarter-section farm remained

unimproved. Secondly, like many

other British settlers who lacked

farming experience, Martin at-

tempted to combine farming with a

different trade or skill previously

acquired in Britain, but often to the

detriment of both occupations.

In James Martin's case, he took to

preaching on the basis of his

strongly-held fundamentalist religious

beliefs developed in England;

but the increasing amount of time he

devoted to this only further de-

layed the improvement of his farm and

further reduced his family's

circumstances. Nor was he a very

successful preacher. Thirdly, the

letters clearly show that Martin cared

little for many of his American

neighbors. While part of this antipathy

resulted from differences in

religious beliefs, it was not uncommon

for British settlers to comment

disparagingly on settlers of other

nationalities, especially the Ameri-

cans around them.5 This

Martin frequently did.

Only a little can be learned of James

Martin and his family before

they emigrated to America, and this

comes entirely from biographi-

cal accounts in the relevant Ohio county

histories and from his earlier

letters in the London collection written

before he left England.6 He

was born in Ireland in 1774 and at the

age of sixteen joined the Royal

4. A collection of comparable letters

from British immigrants giving their impres-

sions of life in America and the

problems they faced in farm improvement can be found

in Charlotte Erickson, Invisible

Emigrants: The Adaptation of English and Scottish Im-

migrants in Nineteenth Century

America (Leicester, 1972).

5. Erickson felt, by and large, that

there was little antipathy between British and

American settlers on the frontier but

did quote some examples of it. As William Petin-

gale wrote from Rochester, New York, in

1835 to his sister: "The Englishman has no

feelings in common with the Americans.

The latter has an unnatural antipathy to the

former." Erickson 439. Emigrant

letters often show that the English tried to avoid trav-

elling or settling near other foreign

groups, notably the Irish.

6. Apart from what is contained in the

earlier letters, the only other sources for bi-

ographical information on James Martin

and his family are: W. H. Perrin, History of

Crawford County, Ohio (Chicago, 1881), 583, 959; John E. Hopley, History

of Crawford

County, Ohio and Representative

Citizens (Chicago, 1912), 242-44, and

Crawford Coun-

ty Chapter of the Ohio Genealogical

Society, Families of Crawford County, Ohio

1977-78 (Galion, Ohio, 1979), 349.

A British View

141

Navy where he gained his education and

the strong religious views

which lasted throughout his life. At the

age of thirty, after fourteen

years of naval service, he settled on

the north side of London, where

he married Sarah Hawks. They continued

to live there and raise

their four daughters until the whole

family emigrated to America in

1821.7

It is not known what occupation Martin

entered immediately after

leaving the navy, but by 1815, when the

series of preserved letters

commences, he had been for a number of

years a private tutor in the

home of Mrs. Caroline Monro at Barnet, a

suburb ten miles north of

the center of London, where he not only

looked after the well-being

of her son Mordaunt, but seemed to act

as confidant to Mrs. Monro,

particularly in terms of their shared

religious beliefs. By 1815, for rea-

sons which are not clear from the early

letters, Mrs. Monro had de-

cided to give up her London house to

move into the East Anglian

countryside in the east of England,

leaving James Martin without a

job and the Martin family without a

home. Although she had pro-

vided her employee with sufficient

compensation to allow him to set

himself up on a small farm or with an

inn, nothing appeared to come

of these schemes.8 As a

result, by 1821 James Martin had decided to

emigrate with his family to America

where his brother was already

settled.

Of the twenty letters in the collection,

nineteen were written by

James Martin and one by a daughter.

Eleven were written from Amer-

ica between 1821 and 1836, of which

seven were addressed to Mrs.

Monro and four to her son Mordaunt. In

the quotations from the let-

ters that follow, the original spelling

has been retained but some ad-

ditional periods and paragraphing have

been introduced to make

their meaning clearer. The first letter,

largely reproduced here, gives

a graphic account of the Atlantic

crossing which the Martins en-

dured and their welcome in Delaware by

James's brother over seven

weeks after leaving England.

7. All four daughters were born in

England. The birth dates of the two older

daughters, Martha and Betsy, are

unknown, but Mary was born in 1812 and Caroline

in 1816. The youngest child, Joseph, was

born in America in 1822.

8. In a letter to Mrs. Monro dated 12

July 1815, James Martin states, "I am not will-

ing to give up the idea of farming, but

I think I would be content in any plan appointed

me. I do not like anything mercantile

..." By 1 August of that year he is writing to

her: "I fear a public house must be

my lot. I feel it is quite incumbent on me to search

after something that will procure a

livelihood for my family, in consequence of not be-

ing employed by you." Later letters

show that the search for an inn to run proved

unsuccessful. Greater London Record

Office Acc. 1063/131 and 133.

142 OHIO HISTORY

20 October 1821 ... It is with the most

sincere thankfulness to Al-

mighty God for the preservation and safe

conduct of myself and dear

family that I now enter on a detail of

occurrences since we left you. We

left Gravesend on the 19th August and

had fair weather for about a

fortnight tho' the winds were light and

we did not get very forward

on our voyage. During this part of our

voyage nothing particular oc-

curred but as is common we were all

sea-sick except Caroline. Howev-

er this lasted only a few days, the

children afterwards improved very

much in their looks and Martha got quite

fat. She has much im-

proved from the change. On the 2nd of

September, about eight in

the evening in Lat. 47° Long.

27° a gale of wind began to blow tremen-

dous indeed. I never witnessed anything

to be compared with it. It is

impossible for me to give an adequate

idea of it. We could only lye to

throughout the chief part of the time it

lasted. When I had an oppor-

tunity of standing on the aftermost part

of the ship and clearly ob-

serving that small body to which we had

consigned ourselves, strug-

gling amidst the waves, the scene was

awfully sublime, and often

brought to my mind the figurative

expression, "raging waves of the

sea foaming out their own

destruction" and often indeed did they

visit their rage against us as if to

sink us in the vast abyss, but a great-

er than them was there.

To this gale succeeded calms and blowing

winds until the 12th when

we had another very heavy storm during

which our rudder was

rendered useless by a heavy sea. Thus in

the midst of the Atlantic

we were placed completely at the mercy

of the waves and winds. At

this accident every countenance was cast

down. I however kept my

wife and children in pretty good spirits

and they bore our disasters

pretty well. Invention was put to the

rack. All that were capable were

offering their advice. The wind was

against us fixed steadily and it

was contemplated that we should lay the

ship before it and endeav-

or if possible to reach Europe. Lisbon

or Cork were the most likely

places that presented themselves as the

nearest habours. These were

the prevailing opinions amongst the

Captain and cabin passengers,

not mine. I saw other prospects and

hoped better things and so it

turned out. A young man, a sailor, on

the morning of the 14th at the

risk of his life took the advantage of a

calm, went down over the stern

of the ship, unshipped a small piece of

wood, called a woodlock

which prevented the rudder from being

unshipped by the sea on

the rolling of the vessel. This piece of

wood was, I think, more than

three feet under water, I believe about

4 feet, am not certain. This

had been previously considered

impracticable. After this there was

A British View 143

much difficulty in getting it unshipped

and brought on board. How-

ever this was accomplished and proper

hands set about repairing it

which was finished on the afternoon of

the 15th and shipped in the

same evening to the great joy of all on

board. Thus our dismal pros-

pects ended. The captain gave the above

named sailor 20 dollars re-

ward.

I must inform you that the storm of the

2nd of September which with

us lasted about 20 hours reached the

American coast on the 3rd and

was considered the heaviest gale of wind

ever remembered on this

coast. This I was told by the pilot who

brought our ship up the Dela-

ware. There were two pilot boats lost in

it and all hands perished

with several ships on the coast at the

time. From the 15th of Septem-

ber to the 21st we had a succession of

gales and calms. Afterwards

we had tolerable fine weather until the

end of our voyage altho' we

made but little progress, that is we had

a tedious time of it.

We made land on the 49th day after we

left Gravesend and 51 days

after we left London dock. We made Cape

Henlopen the southern-

most cape of the entrance of the

Delaware ... sailed quite up the bay

and arrived that night near Newcastle.

.... The next morning about

three o'clock the ship's boat took the

Captain, three cabin passen-

gers and me up to Newcastle. This was

the first place I set my foot on

American ground. I proceeded from there

in a stage to Wilmington,

distance five miles, the vehicle was

tolerably easy but the roads

most of the way were in a complete state

of nature.

My brother lives about five miles from

Wilmington on the Lancaster

road where I arrived about 11 o'clock

and found him and family very

well and very glad to see me. Having

left my wife and family on board

the ship at Newcastle I staid at my

brother's only about an hour this

day. We both set off for Wilmington and

on the packet from there up

the river to Philadelphia when I again

joined my family, the ship

having in the interim gone up the river.

My family came all ashore

as soon as possible. . . . We all

arrived safe at my brother's house

where my family was affectionately

received and are all here where I

write this.

This country to a person just arrived

from England appears as under a

very bad course of cultivation, the

ground seemingly very foul altho'

I have seen some trifling exceptions. I

am of opinion that not more

than half of the land in this

neighbourhood has ever been cleared of

144 OHIO HISTORY

timber. Idleness and speculation seems

to be the fault of all (with lit-

tle exception) around me, food and

raiment is easily acquired there-

fore improvement is very tardy. ... A

good farm may be bought

here for between twenty and thirty

dollars an acre. Wheat is about 6

shillings a bushel. Taxes-I have seen

none yet that could tell me the

amount of their own even. My brother

says from 5 to 8 dollars upon

an 100 acres, this includes all taxes

and poor rates.

He is much against my going to the back

country on account of my

children being all girls unless he was

going with his family which he

is not prepared for at present, altho'

inclined much to go. This I can-

not advise on, he is so well off where

he is. A most beautiful farm was

offered him for sale a day or two ago,

beautifully situated on a run-

ning stream of considerable size. . . .

What was asked for the above

farm was about 20 dollars an

acre-whether he will buy it or not I

cannot tell. The land is a rich sandy

loam. ... I am extremely happy

in the change I have made. I have found

no religious society yet and

whether I shall at present I cannot

tell. I feel a little liberty here in ex-

pressing myself which I did not there

[in England]. I was delighted

[with] the market of Philadelphia, its

regularity and cleanliness. I

walked thro' the principal parts of the

town and never saw one man

out of work, nor have I since I left it.

However my opportunity for see-

ing anything has been very limited ....9

Martin's next letter to Mrs. Monro was

not sent until fourteen

months later, a delay he explained by

being "completely occupied in

travelling in quest of a future residence."

For two months after leaving

his brother's place near Wilmington he

had lived in Philadelphia

"looking for some situation that

might suit" but he found neither the

city nor its religious sects to his

liking. Intent on making a "departure

from that scene of corruption" soon

after the birth there of his son,

he decided to look to Ohio and much of

this next letter describes

his journey to Coshocton County with his

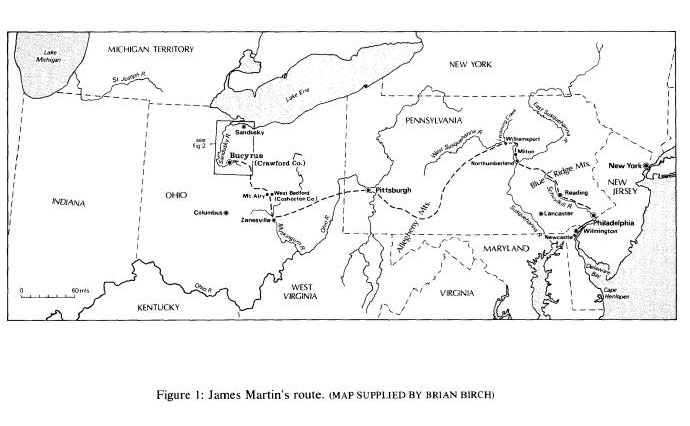

family. Figure 1 lays out

the route he took.

9. Letter from James Martin to Mrs.

Monro, 20 October 1821, Greater London Rec-

ord Office, Acc. 1063/138.

A British View 145

27 December 1822.... Having prepared for

my journey from Phila-

delphia, I embraced the first

opportunity to proceed. I sent 6 cwt of

my baggage to Northumberland situated in

the forks of the Susque-

hanna, 120 miles from Phila . . . I put

the rest of my baggage, about 4

cwt in my light waggon with one horse,

the children sometimes all

riding, sometimes riding alternately. I

should have told you that my

family is increased since I left you, my

wife had a son, born the 14th

of last February, which we call Joseph,

she therefore was obliged to

ride mostly with the child, but we had a

noble horse, who as-

cended the hills like a lion, but descended

like an ox ... Mary,

Betsy, Martha, Caroline were all quite

able to guide him through our

whole journey which was about 500 miles.

We passed through Reading (having left

Phila about the middle of

July) a very handsome little town on the

Schuylkil river 50 miles from

Phila .... From there were proceeded

towards Northumberland,

crossing in our journey 40 miles of

mountains, I believe a part of the

blue ridge of the Allegany range. The

journey was very pleasant and

we all enjoyed good health. In crossing

a part of these mountains,

called the Flat Mountains, 4 miles over

we were all rolling very pleas-

antly along when I heard a noise which

immediately struck me as the

noise of a rattlesnake. I jumped out of

the waggon and just caught a

glimpse of it entering some heath on the

roadside. I struck twice at it

hearing its rattle altho' I did not see

it. On searching further we

found it nearly dead. It was easily

killed, the children entertained no

fear of it but immediately took it up in

their hands, cut off the rattle

and threw the snake away. They have the

rattle now. It was nearly

four feet long.

We arrived at Northumberland in seven

days and was very civilly en-

tertained at a small inn where we put up

and where I had sent my

baggage. The Americans in general are

glad to see strangers and are

very civil to them. They would be a very

interesting people if it was

not for their great duty Gain - I should

have said their accursed

God.

Having rested one night we proceeded

along the banks of the west

branch of the Susquehanna, with a plan

to proceed 40 miles up the

river to Williamsport. Having a good

natural road we past thru' Milton

11 miles from Northumberland, a nice

little growing town of one street

on the bank of the river. Arrived at

Williamsport the 10th day from

leaving Philadelphia, Joseph a little

unwell from having been fed

|

146 OHIO HISTORY |

A British View 147

with some eggs on the road. Here we took

private lodgings where we

remained 2 months during which time I

was always busied with

enquiring after or travelling in search

of land. I explored a great deal

of the country between the two branches

of the Susquehanna and

ascended Lycoming creek to its

source.... Land could be pur-

chased here from 2 to 60 dollars per

acre according to its situation on

hills or river bottoms, however there is

no good land of first rate

quality.... It is a wonderful country

for fine timber, they grow to a

wonderful size along the creeks from an

hundred to an hundred and

forty feet high and 3 and 4 feet in diameter.

Wearied at length with my researches in

that part of the country I re-

solved on pushing forward for the state

of Ohio and set out from

thence with my family. In company with

two other families bound

thither there were twenty seven of us in

all in company. There were 10

or 12 young men who handled their

firearms wonderfully and along

the road made great havock among the

squirrels, supplying the

whole company with squirrel meat. . . .

Our party often surrounded a

tree with 6, 7 or 8 squirrels in it and

one of the party soon mounted

the tree, disturbed the squirrels. Their

leaps from the tree at this

time was very entertaining to see ....

This was the manner we spent

the principal part of the journey travelling

and squirrel hunting. The

apples and peaches were in abundance

along the road and of them

we had a plentiful supply.

Of the road southward from Williamsport

it is impossible for me to

give you an adequate idea, in some

places ascending the steepest

precipice, at other places literally

sliding from one rock to another,

and again, large rough unfixed stones in

the road where the wagon

for miles was hopping from one stone to

another. Thus we surmount-

ed one hundred miles of the road until

we once more struck the

Philadelphia and Pittsburgh road, 95

miles from Pittsburgh. We

then had good roads over the remainder

of the mountains and the

chief mountains of the Allegany until we

arrived in Pittsburgh.

This is a remarkably filthy town. They

burn coal here and the towns-

people are nearly the colour of the

coals. There is a very good market

here, and a considerable trade, being

the principal emporium be-

tween Philadelphia and the western

states. After we crossed the

mountains I was much surprised at the

change . . . the land seemed

to improve immediately. I think I acted

right resisting every entreaty

to stop to the eastward. . . . We stayed

at Zanesville two nights and

148 OHIO HISTORY

got a little repair done to our wagon.

Zanesville is on the Muskingum

river and lies very low and must be

unhealthy.

From there we put about and proceeded

directly north into Coshoc-

ton County to a place called West

Bedford. Here we arrived in good

health and spirits having travelled 500

miles without meeting with

any accident worth mentioning.

We stayed at West Bedford three weeks.

It is a very hilly country but

I have seen many of the hills having six

or eight inches deep of black

mellow vegetable mould on their tops. If

it was not for speculation

many or nearly all the people in this

state would have been in a most

comfortable situation. We are living in

a log house, it is very cold but

we have plenty of firing for little or

nothing. We are now eight miles to

the west of West Bedford in a town that

is newly laid out of three

houses called Mount Airy. ... It is high

and healthy. We all enjoy

good health and have been in this part

of the country about 9 weeks.

This part of the country is much more

level than any part I have seen

to the eastward of this state. It is a

rolling country, there are many

quarter sections of land to be sold here

from 4 to 8 hundred dollars

according to the quality of the land and

the number of acres cleared

and in a state of agriculture. I was

offered 160 acres of land, 70 of

which was in a state of husbandry and 25

of which is beautiful

meadow with a small stream of water

running along it, a dwelling

house, stable and granary, for 700

dollars.10

Martin concluded that letter: "I

intend still going farther and

where land may be had for one and a

quarter dollars. I am on the

straight road for Sandusky and the tide

of emigration flows that way.

Congress has much land to sell that way

...." In his next letter, writ-

ten the following summer he reported on

the continuation of his mi-

gration that finally brought him into

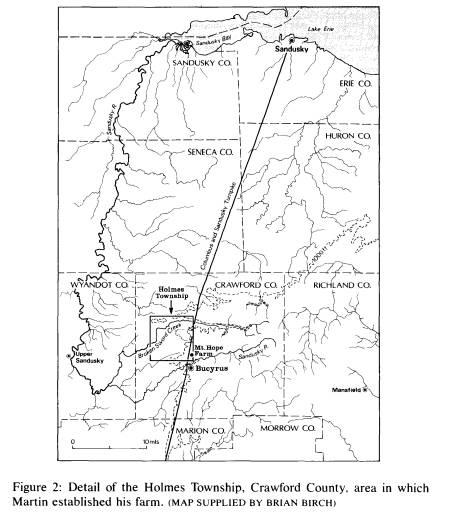

Holmes Township, Crawford

County (Figure 2) where he was to

settle.

10. Letter from James Martin to Mrs.

Monro, 27 December 1822, Greater London

Record Office, Acc. 1063/139, (2

letters). The village of Mount Airy from which Martin

wrote had been laid out in the southwest

of Newcastle Township, Coshocton County,

in 1816. It had a schoolhouse and up to

twenty houses by 1820 but was abandoned by

the 1860s. M. M. Hill, History of

Coshocton County, Ohio (Newcastle, Ohio, 1881).

|

A British View 149 |

|

|

|

June 1823. My last left me at Mount Airy, county of Coshocton .... The last winter having proved very severe and the spring exceedingly wet I could make but little inquirys after land and it was the first of April before I could set out in search of a future residence, but hav- ing travelled about 70 miles north west of Mount Airy I entered a fine district of land called the Delaware district, situated on both sides the river Sandusky. There are seven countys and but little of it entered yet. I crossed the Sandusky near its source after having |

150 OHIO HISTORY

crossed the famous plains called

Sandusky plains. I believe they are

40 miles along and about 20 broad. The

land on the plains I did not

like. I rode about 50 miles on them, the

timber on them is very inferi-

or and scattered in groves at irregular

distances over them. Many

people choose them and particularly the

Yorkshire English. There

are several families of Yorkshire people

in their borders.

But having left the plains and crossed

the Sandusky and at a small

new town called Busirus of only eight or

ten houses and only about

eighteen months old, I immediately

entered a fine tract of land lying

between Sandusky river and Broken Sword

creek, distance about 7

miles. The only fault I found was that

it was too level and that water

lay too frequently on the land. It is

exceedingly rich and heavily tim-

bered. On my return from Broken Sword I

crossed . . . a small emi-

nence or little hill, the highest piece

of ground I met with and having

observed the land adjoining, I concluded

I would travel no further

altho' some parts of it was wet. Two

mile distance from Busirus and 42

from the city of Sandusky on the

entrance of Sandusky bay on Lake

Eire.

This little hill I went and purchased at

the land office of Delaware

with the quarter section belonging

thereto. There is a road about to

be opened by my house to the city of

Sandusky from Columbus, the

capital of the state, and when the New

York Canal is finished which

strikes Lake Eire on the east and which

is expected to be finished

this summer there will be only 42 miles

of land travel from my house

to New York-a distance of about 700

miles.

Well, having entered my land at Delaware

I returned to Mount Airy to

my family and prepared for another

removal which we were unable

to accomplish until the 20th May through

the wetness of the season,

but having agreed with a person to clear

four acres of land and build

me a cabbin I made myself the more easy.

This spring has proved very backward for

all farming concerns, and

much more so for me for I expected to

have had 4 acres cropped, but

am quite disappointed through the

excessive rains, the man not be-

ing able to get forward with clearing

and burning. This is the greatest

disappointment met with in America but

seeing it is the will of provi-

dence I trust I shall be found truly

submissive. We will be able to get

in some potatoes and turnips and having

the summer before us, we

will be able to get a good deal of land

clear for wheat this autumn

A British View 151

and for crops next year. I am busy now

clearing a garden and getting

in some garden seeds which altho' late

will be better than none. I

should have said above that the last 70

miles of our journey was the

worst of the whole but we all arrived

safe and without any acci-

dent. .... I have just to mention that I

live only 3 miles from an Indi-

an reserve, the Wyandots. When this

country was sold to Congress

they reserved to themselves twelve miles

by eighteen. They have a

little town called Upper Sandusky, a

school, a mill, a methodist

preacher amongst them. They grow Indian

corn and keep a great

many cows. .. .11

In his next letter, written only two

months after the last but not

posted for another six weeks

"principally on account of the distance

to the post office" which was

thirty miles away, Martin continued to

describe the problems of setting up a

farm in a new country and espe-

cially the lateness of the crops because

of the wet summer.

8 August 1823. .. .I got some corn in in June which now looks very

beautiful altho' five weeks too late. I

have got plenty of potatoes in

the ground which promises much. I have

likewise some turnips but

after the American manner which did not

succeed. I have sown a

second time but can say little about

them yet. Mangle worzil altho'

sown very much out of season looks very

well. We have cucumbers in

abundance altho' quite out of season

mainly by sowing them in the

garden. I have sunk a well and got good

water at 30 feet deep. I

stoned it up about 8 feet and cut down a

hollow sycamore tree which

I put in the well on the stones which

walled the remainder up three

feet above the surface. The hollow part

of the tree was nearly 5 feet in

diameter.

The country is settling fast round me

and I will soon have plenty

of neighbours altho' I was obliged to

hire men to cut me a road

through the woods for nearly two miles

to Mount Hope, the name I

have given my farm.

11. Letter from James Martin to Mrs.

Monro, dated only as June 1823, Greater

London Record Office, Acc. 1063/140. By

settling in Holmes Township, Crawford

County, in 1823, Martin was one of the

early pioneers there. No settlement had been

possible there before 1820 and the

western part was not taken from the Wyandots until

1836.

152 OHIO HISTORY

I never seen anything equal to the

thickness of the vegetation in this

part of the country. Owing to the

wetness of the season I believe an

intermitting fever with some instances

of ague prevails. I believe a

want of cleanliness and the eating of

unwholesome food by poor set-

tlers is another cause of this disorder

with other sufferings and priva-

tions which people in a new country are

liable to. The last 40 miles of

our journey Martha and Mary were obliged

to walk up to the knees in

mud frequently, and both of them were

seized with an intermitting

fever and ague, which I suppose was a

consequence of their fatigue

and hardship. I hesitated a little about

bleeding them but did so

after they had been ill two or three

weeks - which stopped the ague

altho' not the fever. I then made strong

bitter of the wild cherry tree

and administered the Peruvian bark

especially. They are now getting

strong ....

I am persuaded I have settled in a

climate best adapted to our Euro-

pean constitution. Here we have slept

all the summer with a sheet

and coverlet with only a night or two's

exception. On the contrary at

Philadelphia we were obliged to have

open windows, no furniture

and neither shirt not coverlet. ... To

conclude, after a journey over

sea of about 4000 miles, a journey over

land of about 700 miles and

myself thru' America one thousand miles,

I think I have great reason

to adore the Beneficience of God . . .

two or three weeks' illness in

two of the children is the only

exception to perfect health ... 12

No more letters were sent by Martin to

Mrs. Monro in England for

three and one-half years, after which

they continued to arrive at only

infrequent intervals over the next nine

years. Now problems connect-

ed with making a living from the farm,

of his failing health, and of

raising a large family increased.

Preaching in the local neighbor-

hood, which often brought him as much

hostility as respect, also

began to take up more of his time.

Having said in his first letter from

Crawford County that he was

"quite pleased with the choice of

residence I have made," Martin's

next, written after his first few

seasons there, showed that he had

made slow progress towards establishing

his farm and even slower

progress in accustoming himself to the

ways of backwoods society:

12. Letter from James Martin to Mrs.

Monro, 8 August 1823, Greater London Record

Office, Acc. 1063/141.

A British View 153

"I am here in the wilderness having

cleared a few acres of land and

owning 160 and having ten head of cattle

and one horse, with a quan-

tity of hogs, and poultry in abundance,

but amongst the most traf-

ficking, trading, quirking people in the

world, true children of the

great whore. . ."13

Another letter written over two years

later showed that most of his

farm still remained unimproved and the

family depended as much on

their animals freely roaming the forest

as on their crops. Martin still

had little time for his neighbors.

11 August 1829 ... I have cleared only

about twenty acres of my land

most of which I have put in grass and

have mown about 4 tons of

hay. This year I raised about two acres

of wheat, a little Indian corn,

plenty of potatoes and some flax. I keep

only one horse and have two

yoke of oxen for working, in all about

twenty head of cattle. My cows

range the woods in the summer time and

almost daily come up to

suckle their calves. When they miss

coming up one of the children

mounts our little mare, enters the

almost impenetrable forest, scours

the woods for 2, 4, 6 or even ten miles

sometimes of a morning, under

the shade of immensely high timber,

until the well known sound of a

bell suspended to the neck of a leading

cow or ox directs her to the

feeding herd - who, all at the word

'home' direct their march on-

ward....

Most of the children have learned to

spin and Mary has learned to

weave. We now nearly make all our

wearing apparel as we keep a few

sheep and grow flax and Mary weaves and

after having been previ-

ously spun in our own family. We keep

plenty of poultry and a few

hogs for we are not willing to keep many

as our neighbours are none of

the most honest and hogs run at large.

I am nearly completely disgusted with a

republic and the society it

produces. . . . The New Englanders are

by far the best society and

consequently the best neighbours - I

feel sorry I am not entirely

amongst them. I believe the western

parts of Pennsylvania produces

the basest race of people in the western

states being bred up in or

13. Letter from James Martin to Mrs.

Monro, 15 March 1827, Greater London Rec-

ord Office, Acc. 1063/142.

154 OHIO HISTORY

near the mountains, they in a great

measure partake of the ferocity of

the bears and wolves their neighbours

....

I have been out but very seldom this

summer reading the scriptures

amongst the people. I went to see a

friend who lives about 30 miles off

a few weeks ago. I slept at a friend of

his 10 miles short of the place he

lives at who was a very sensible man and

not shackled by the priest-

hood. I got to bed about one o'clock ....

I arrived next day at my

friends and got to bed about the same

hour, read the scriptures pub-

licly in the schoolhouse next day to a

considerable number of peo-

ple, which after we finished many of

them followed to my friend's

house to hear something more ....

Preachers of all denominations are on

fire at me. The Methodist con-

ference this year placed their ablest

man in this neighbourhood as is

said to counteract my influence. Indeed

I have laboured very little

against them as I could not be absent

from my own affairs with pro-

priety. .. 14

The next letter in the series came two

years later from Martin's eld-

est daughter, Martha. Written apparently

without his knowledge and

begging for monetary help from Mrs.

Monro, Martha told of her fa-

ther's failing health and eyesight, of

the still unimproved state of the

farm and of the family's "straitned

circumstances." Their friends

were "all gone and we are among

strangers and without a friend, in an

ungrateful country... ."15

Mrs. Monro clearly responded to Martha's

plea, but less than

three months later Martin wrote again to

his former employer, largely

discounting problems with his health and

the state of the farm. Ad-

mitting that he had lost the sight of an

eye "thro' fatigue," much of

the letter dwelt on his increased

preaching activities by which "I am

quite turned into a public speaker. I

have this last autumn been much

occupied from 20 to 40 miles off, in

expounding the scriptures of the

Kingdom of God.... I rode very often

thro' almost impenetrable

forests for many miles following tracks

scarcely visible, at other times

through broken roads and mud knee deep.

.."16

14. Letter from James Martin to Mordaunt

Monro, 11 August 1829, Greater London

Record Office, Acc. 1063/143.

15. Letter from James Martin to Mrs.

Monro, 6 November 1831, Greater London

Record Office, Acc. 1063/144.

16. Letter from James Martin to Mrs.

Monro, 17 January 1832, Greater London Rec-

A British View

155

In a letter written three years

previously, Martin said that he had

heard favorable comments of the St.

Joseph area 200 miles to the

north-west, mainly within Michigan

Territory, which "seems to have

the principle amount of migration to it

at present. It is celebrated for

fish, fine water and some good land - it

is just come into the market

. . as far as I can learn [it has] a

sandy soil with many sandy and

barren prairies - but some are very rich

and easy of cultivation,

much easier than where I reside and much

better waters...."17

Now that his preaching activities had

made him better known in the

surrounding districts, he had hopes of visiting

the St. Joseph area:

"I intend this summer if I can

accomplish it to go on a journey to the

river St. Joseph on the Michigan lake

where is a large new settlement

who have expressed a desire to hear me.

. ."18

None of the later letters, however,

indicate if he ever made this

journey. Rather they suggest that while

Martin's family continued

the struggle to improve the farm he,

either through an inability or

lack of interest in working their land,

chose instead to become more

active in preaching locally, although

not always meeting with much

success. In the first of two letters

written to England in 1833, he stat-

ed: "If I were able to work we

should want for nothing, providing I

could attend to it, but this I can

hardly do. . . . We may suffer some

privations on account of my inability to

labour, but we grow flax,

have a few sheep, spin and weave and the

children are willing to

work. I spend a great deal of my time

abroad as I can do little at

home.. ." 19

In the second letter written on 2

September 1833, Martin added: "I

am still occupied, when I possibly can,

in riding out. ... It is aston-

ord Office, Acc. 1063/145.

17. Letter from James Martin to Mordaunt

Monro, 11 August 1829, Greater London

Record Office, Acc. 1063/143.

18. Letter from James Martin to Mrs.

Monro, 17 January 1832, Greater London Rec-

ord Office, Acc. 1063/145.

19. Letter from James Martin to Mordaunt

Monro, 28 April 1833, Greater London

Record Office, Acc. 1063/146. Indicative

of Martin's greater interest in pastoral work

and preaching than farming was his

taking into his family a young Englishman, Thom-

as Alsoph, described as a nobleman's son

and "not always sane in mind." Hopley's

Crawford County states that Alsoph came to America with the Martin

family but the

letters suggest otherwise. He had by

1832 been for ten years under the care of some-

one who had so neglected him that Alsoph

had "suffered a great deal of hardship, in

hunger, nakedness and cruel punishment

from a brute of a man." Because of this Mar-

tin states in his letter of April 1833

that Thomas Alsoph had now come into his care

with the financial support of the young

man's father in England. John E. Hopley, His-

tory of Crawford County, Ohio and

Representative Citizens (Chicago,

1912), 244, and

Greater London Records Office, Acc.

1063/145 and 146.

156 OHIO

HISTORY

ishing the opposition the truth meets

with particularly from profes-

sors. My views are most acceptable to

those who will not be bound

down under the shackles of

superstitions, rites and ceremonies ....

The people here are wonderfully

intelligent generally speaking but

there is a ... low cunning which makes

them very disagreeable. ...

I have spoken a great deal in our

village but it has made but little im-

pression. There is a great deal of envy

and jealousy and some say it is

only to make myself look singular . . .

yet they generally crowd to

hear me. Everyone here is afraid that

his neighbour should be

greater than he is in politics. This

principle they carry into religious

controversies ... ."20

The village Martin was referring to was

Bucyrus, or as he wrote,

".. .Busirus, spelled by those

affected people Bucyrus." Several of

his letters had noted the rapid growth

of the settlement and of the

surrounding area. Whereas in 1823 he

reported that Bucyrus had

"only eight or ten houses," in

1829 he wrote: "our little town grows

very fast. I suppose it contains nearly

100 houses, 4 stores and 3 tav-

erns."21 In the same

letter he wrote of the partly completed turnpike

from Lake Erie to Columbus which passed

close to his farm: "This

has been a great benefit to us in this

place." In another letter he stat-

ed that the turnpike on which "we

have a stage coach passing every

day" was "as good a turnpike

as the materials of this country will

afford-at this moment it is

excellent."22 In the same letter in 1833 he

20. Letter from James Martin to Mrs.

Monro, 2 September 1833, Greater London

Record Office, Acc. 1063/147. Martin

attended several religious "camp meetings," two

of which he described in his letters,

but he does not appear to have preached at any.

In his letter of September 1833 he

described them as follows, drawing a comparison

with the travelling salesmen and show

people who frequented local and county fairs in

England and resembling fairs that held

each year at Barnet where both Martin and

Mrs. Monro had lived: "We have camp

meetings here in the woods lasting six or seven

days and some have been protracted to 30

days as I have been informed.... At the

camp meetings many thousands meet

together and live in tents like Barnet fair people.

Sometimes, considering the number of

people, they are considerably orderly, pro-

tected by the Law. But their very order

is complete confusion-preaching, praying,

shouting, groaning, hallooing, all

frequently at the same time. There is a large stage

erected upon which the preachers (for

sometimes they are many) stand, in the front of

which is their prayer ring, a space of

ground enclosed into which those that want reli-

gion enter when they are prayed for.

This is a scene that I cannot describe, some lying

apparently lifeless as you would think,

some you would think were dancing for joy,

some tossing, some tumbling, some

screaming, whilst others you would think were

drawing their last breath. Many honest,

well-meaning people are entangled in these

things...."

21. Letter from James Martin to Mordaunt

Monro, 11 August 1829, Greater London

Record Office, Acc. 1063/143.

22. Letter from James Martin to Mordaunt

Monro, 28 April 1833, Greater London

Record Office, Acc. 1063/146.

A British View 157

was able to confirm that "the

irregular state of the post office in this

backwoods ... is now well regulated and we have a mail

every

day." Indeed, while his own farm

remained underdeveloped, Mar-

tin could appreciate the rapidity of

improvement around him. As he

wrote in 1836, in the last letter in the

collection: "The emigration to

this country is astonishing and altho'

14 years ago I sat down in a

complete wilderness I am now surrounded

with a very dense popula-

tion."23

He died four years later at Mount Hope

Farm.

23. Letter from James Martin to Mordaunt

Monro, 9 October 1836, Greater London

Record Office, Acc. 1063/149. In his previous letter

Martin stated that he had still only

cleared thirty of his 160 acres, the

rest still being under woodland. He also had four

milk cows, eight other cattle and some

sheep. He added that "it is with great difficul-

ty that we work our farm-all heavy

labour . .. but . . . this is a fine country for work-

ing men and for all farmers who can do

their own work." Letter from James Martin to

Mordaunt Monro, 28 September 1834,

Greater London Record Office, Acc. 1063/148.