Ohio History Journal

DAVID G. TAYLOR

Hocking Valley Railroad

Promotion in the 1870's: The

Atlantic and Lake Erie Railway

Industrialization had begun in Ohio

before the Civil War, and, after a war-imposed

delay, promised to accelerate rapidly

thereafter. The Panic of 1873, however, stalled

the process substantially and destroyed

many small industrialists and businessmen.

With the elimination of the financially

weaker businessmen, the way was paved for

reorganization of the state's railroad,

coal mining, and iron industries in the 1880's

by larger, stronger, and sometimes

out-of-state or national corporations which ac-

quired at relatively small cost the

remains of the shattered enterprises that had been

initiated by the small-scale operators.

Using their superior financial resources and

organizational skill, the larger

companies succeeded where the smaller firms had

failed. But even though they failed, the

efforts of the small industrialists are worthy

of attenion.1

Ohio was generously endowed with the

coal and iron ore necessary to produce

power and finished products. Bituminous

coal underlaid about twelve thousand

square miles, and iron underlaid about

eight thousand square miles. Almost all of

these resources were located east of the

Scioto River. One of the most richly en-

dowed regions in the state was the

Hocking River and its tributaries, the Sunday and

Monday Creeks, in south central Ohio.

Coal and iron were located in close prox-

imity in this general area, and made it

"the most promising center of iron production

in the state" in 1880.2

The development of Ohio's coal and iron

resources began in the 1820's, and by

1840 Ohio ranked second to Pennsylvania

in the production of pig iron. Through-

out the antebellum period, however,

mines and foundries remained relatively small

enterprises producing for a local,

agriculturally-oriented market. In 1850 only three

of Cincinnati's forty-four foundries

were capitalized at over $150,000, and only one

employed over 200 men. In 1860 the state

produced fifty million bushels of coal

1. Philip D. Jordan, Ohio Comes of

Age, 1873-1900 (Carl Wittke, ed., The History of the

State of Ohio, V, Columbus, 1943), 220-252.

2. Tenth Census of the United States,

1880: Report on the Mining Industries of the United

States (Washington, 1886), 621.

Mr. Taylor is Assistant Professor of

History, Mankato State College, Mankato, Minnesota.

264 OHIO

HISTORY

and 105,000 tons of iron.3

By the end of the Civil War enough

geological exploration and development had

taken place to indicate that the eastern

part of Ohio had immense industrial poten-

tialities. This fact whet the appetites

of entrepreneurs, and in the late 1860's Ohio

became the scene of a multitude of

projects and promotions, chiefly in the interde-

pendent fields of coal mining, iron

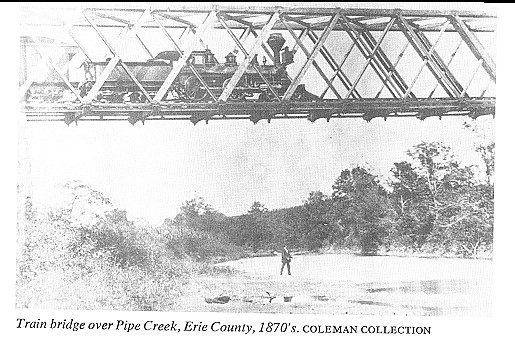

manufacturing, and railroads. Railroads not

only contributed to the demand for coal

and iron, but were a necessary factor in

the opening of many veins of coal and

iron, and for the transport of the ore to pro-

cessing points.4

In 1870 an elderly lawyer described with

enthusiasm the industrial transformation

taking place in Lancaster, in the

northern part of the Hocking Valley:

Our staid sober old town is in a

paroxism of improvement. The famous stone Court

house will be under roof this fall. The

Columbus R. R. is doing a large business both

in freight and passengers, and what

shows a sudden and high advance in civilization is a

formidable strike among the Nelsonville

Coal miners.... The R. R. construction trains

run to Chauncey, and it will be open to

passengers and freight in a few days.... So you

see how we go. Nothing is talked of but

coal and iron and R. R.s--and Engineers and

Geologists are our only aristocracy.5

Changes were rapidly taking place, but

in 1870 the Hocking Valley was not yet

a major mining region.6 Before

it could be such, its rich coal lands had to be con-

nected to markets and foundries by

railroads--a task requiring substantial capital.

In the late 1860's and early 1870's

there was a frantic scramble by Hocking Valley

businessmen to acquire mineral rights,

open mines, and project railroads through

the coal fields. The pace of development

is revealed by the fact that employment

of miners in the Hocking Valley rose

from 600 in 1870 to 2,000 in 1874, and pro-

duction of coal increased almost

tenfold, to 1,000,000 tons, in the same period.7 In

1870 the only railroad tapping the

region was the Columbus and Hocking Valley,

a coal carrier which began operations in

1869. Its success revealed the immense

profits that awaited those who would

lead in the industrial development of the valley.

Throughout the 1870's the Columbus and

Hocking Valley paid generous dividends,

and even in 1876, when the depression

caused many railroads to flounder, it re-

ported "net earnings" of

$378,782.90, which was 43.2 percent over declared ex-

penses, and paid dividends of 8 percent.8

3. Harry N. Scheiber, Ohio Canal Era:

A Case Study of Government and the Economy,

1820-1861 (Athens, 0., 1969), 339-342; Peter Temin, Iron and

Steel in Nineteenth-Century

America; An Economic Inquiry (Cambridge, 1964), 199; Carl M. Becker, "Miles

Greenwood,"

in Kenneth W. Wheeler, ed., For the

Union: Ohio Leaders in the Civil War (Columbus, 1968),

268-269. Before the Civil War when hardwood

forests were plentiful, Ohio iron masters com-

monly used charcoal rather than coke as

their source of heat, making a type of pig iron suitable

for the region's manufacturing purposes.

The foundries thus did not greatly contribute to the

demand for coal.

4. Temin, Iron and Steel, 79-80.

5. Thomas Ewing, Sr., to Hugh Ewing,

June 19, 1870. Ewing Family Papers, Library of

Congress.

6. In 1870 only 105,000 tons of coal

were extracted from the Hocking Valley region.

7. Herbert G. Gutman, "Reconstruction

in Ohio: Negroes in the Hocking Valley Coal Mines

in 1873 and 1874," Labor

History, III (Fall 1962), 244-245.

8. Tenth Annual Report of the

Commissioner of Railroads and Telegraphs, for the Year 1876

(Columbus, 1877), 278-285; J. J. Janney to

Thomas Ewing, Jr., June 14, 1872, Thomas Ewing

Family Papers, microfilm edition, Notre

Dame University Archives.

|

|

|

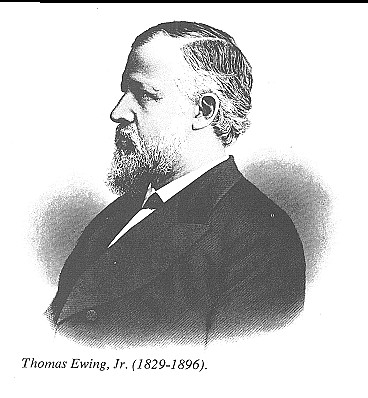

In the 1870's one of the most active Hocking Valley promoters was General Thomas Ewing, Jr., a native of Lancaster, Ohio, the son and namesake of the former Whig Senator and Cabinet minister. Forty-one years old in 1870, Ewing had been a land speculator and railroad promoter in Kansas in the late 1850's and early 60's, won fame as a Union officer in the West during the Civil War, and thereafter had amassed a fortune of about two hundred thousand dollars as a lobbyist in Washing- ton, D. C.9 In Ohio General Ewing concentrated his efforts in Perry County, a county lacking railroad connections to the coal region in 1870 but having two operating mines which together produced 1,350 tons of coal and showed promise of large resources.10 By February 1872, he was associated with a group of small-scale, southern Ohio entrepreneurs led by a New Lexington land speculator, James Taylor, and by Robert Huston, a New Lexington banker. These men were in the process of buying mineral rights to coal and iron lands in the Hocking Valley (ultimately acquiring over 6,000 acres), especially in Perry County. The men formed mining companies to develop

9. David G. Taylor, "The Business and Political Career of Thomas Ewing, Jr.: A Study of Frustrated Ambition" (unpublished PhD dissertation, University of Kansas, 1970). 10. By 1880 there were twenty-four mines which produced 913,774 tons of coal annually. The pace of development accelerated after about 1880, and by 1889 Perry County was the most important coal producing county in a state which ranked third nationally in the production of bituminous coal. In 1889 Perry County had 110 operating mines which yielded a total of 1,565,786 tons of coal. Another county where Ewing was active--Athens--was the only other to produce over one million tons of coal in 1889. Ninth Census of the United States, 1870: Statistics of the Wealth and Industry of the United States (Washington, 1872), 784; Tenth Census: Report on the Mining Industries, 664; Eleventh Census of the United States, 1890: Report on Mineral Industries in the United States (Washington, 1892), 396, 346. |

266 OHIO

HISTORY

the lands, and founded company towns

(Moxahala, Shawnee, Ferrara, Ewing, Car-

bon Hill) which they hoped would grow as

mines opened in the region. Also, on

June 21, 1869, this same group had

organized the Atlantic and Lake Erie Railway

Company which was projected to run

through these lands, connecting with port cities

on Lake Erie and the Ohio River. In an

attempt at industrial integration, which

was unusual in the Hocking Valley at

this time, the group combined speculation,

mining, railroad building, and town site

promotion to create an industrial complex

designed to achieve economies of scale

and to insure that success in any one sector

would act to increase the value of the

others.11

Ewing was the most important man in the

enterprise, contributing in addition to

his modest fortune his talents as a

lawyer, a name well known and respected in Ohio,

acquaintanceships with some of the

nation's most important business and political

leaders, and experience in making these

acquaintanceships profitable. Essentially

a promoter, Ewing had the ability to

digest a large number of geological, geograph-

ical, and statistical facts related to

his business and present them both orally and

in writing in an imaginative fashion

that appealed to the vision or greed of eastern

capitalists, and attracted their

investments. This was no easy task in an era when

an incredible number of persons, many of

them war heroes or European aristocrats,

were promoting railroad and mining

schemes in the East and in Europe.12

From 1869 through 1872 the Ewing-Taylor

group formed at least eight mining

companies: Ohio Great Vein, Carbon Hill,

Moxahala, Dover, Perry County, Atlantic

and Lake Erie, Briar Ridge, and Sunday

Creek Valley. The companies were orga-

nized on the basis of each share of the

stock representing a certain amount of land-

holdings by the companies. The Ohio

Great Vein and Perry County companies

were capitalized at $1,000,000 each,

while the others were capitalized for only

$100,000 to $150,000. Ninety percent of

the Ohio Great Vein stock was water,

and the same situation probably held

true for the other companies. The first land-

holdings were acquired by the issuance

of stock in the companies sold to local

farmers and land owners, some of whom

were speculating in coal lands, who were

persuaded that they would benefit from

the industrial development of the area. All

of the coal mining companies had

uncertain futures and depended for their success

upon acquisition of transportation

facilities and a favorable price structure.13

The same men served as the directors of

all of the mining companies. Lands

acquired by the group were assigned to

one company or another in almost haphazard

fashion, although an effort was made to

keep each company's lands in close prox-

imity. Options for the purchase of coal

lands were being acquired by many small-

scale entrepreneurs and speculators, as

well as by large operators such as a Pitts-

burgh syndicate which included Thomas

Scott, William Thaw, and other executives

of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company.

Some of these men also had railroad inter-

11. Thomas Ewing, Jr., to Van Doren and

Havens, July 29, September 21, 1871, February 2,

1872; to W. A. Gilliam, June 10, 1872;

to Rathborn and Chapman, December 25, 1872; to

Thacher and Sharp, February 21, April

10, 1873, Ewing Papers, LC.

12. Clark C. Spence, British

Investments and the American Mining Frontier, 1860-1901

(Ithaca, 1958), 236.

13. Cincinnati Enquirer, February

29, 1872; Memorandum entitled "To Sec'y of the Sunday

Creek Valley Mining Co.," June 27, 1874; John F.

Parsons to Ewing, Jr., November 1872;

William McCracken, October 30, 1874; Ewing, Jr., to

Hugh Ewing, December 11, 1872. Ewing

Papers, LC.

Hocking Valley Railroads 267

ests for which they were trying to raise

subscriptions from local farmers and towns-

men.14

There was danger that there would be so

many people promoting pet schemes

that it would be impossible for any to

attract enough capital to succeed. Ewing and

Taylor, nevertheless, persuaded various

small promoters and some farmer-specu-

lators to donate their lands and options

to their mining companies in exchange for

stock. The promoters intended for the

mining companies to subscribe to the stock

of the Atlantic and Lake Erie Railway.15

This railroad, as proposed, was to be two

hundred thirty-seven miles in length and

to run from Toledo on the north through

the eastern part of the Hocking Valley

south to the town of Pomeroy at the Ohio

River. This route would give their

mining companies access to the markets in Cin-

cinnati and Pittsburgh, via the Ohio

River, and to Chicago via Toledo by rail. Rob-

ert E. Huston was chosen president,

James Taylor, secretary, and D. W. Swigart of

Crawford County, provisional

superintendent, with J. P. Weethee of Athens County

as assistant superintendent. The group

then began seeking subscriptions to the

company's stock in the towns along the

proposed line, and received a pledge of a

$100,000 stock subscription from the

city of Toledo. On September 8, 1869, the

first stockholders meeting was held in

Newark, by which time $719,700 of A & LE

stock had been subscribed. A seven-man

board was elected, including a wealthy

mine operator and an important

Republican politico from Meigs County, Valentine

B. Horton; Swigart was elected

president.16

Thomas Ewing, Jr., joined the board of

directors of the A & LE in 1872, as did

Charles Foster, an influential

Republican politician who had extensive investments

in real estate around his home of

Fostoria in the northern part of the state. Little

was accomplished under the presidency of

D. W. Swigart, chiefly because of his

inability to secure further financing.

Swigart unwisely chose not to attempt to collect

immediately on the stock subscriptions

and instead tried to secure a loan by the sale

of the company's bonds. R. W. Jones,

sometimes editor of the Athens Journal, was

retained as an agent to go to London and

attempt to sell the company's five million

dollars worth of bonds. He arrived in

England in 1872, and for more than a year sent

letters to the directors which

invariably were optimistic, cheerily reporting that he

was about to complete the sale of the

bonds and needed only a little more time.

Meanwhile, the directors became restless

and suspicious of Jones, and opposition

mounted in several quarters to the

course pursued by President Swigart.17

The opposition to Swigart was led by

James Taylor, who served as the spokesman

of the mining interests. Taylor accused

Swigart of acting in arbitrary fashion and

refusing to consult with and consider

the interests of the mine promoters--who had

subscribed to much of the A & LE stock.

The mine owners were especially irritated

by Swigart's insistence upon the sale of

the bonds in one block because they realized

that this would wrest management of the

company completely from them. Further-

more, the man whom Swigart had appointed

chief engineer aroused Taylor's ire

because he had recklessly promised local

people that construction of the Chauncey-

14. Cleveland Leader, March 22,

1869. A "free railroad" bill passed by the Ohio legislature

in March 1869 paved the way for entry of

out-of-state railroad companies into the coal field

by allowing them to lease in-state

railways, a practice which had previously been illegal.

15. James Taylor to Ewing, Jr., December

3, 1873, Ewing Papers, LC.

16. Edward Vernon, ed. and comp., American

Railroad Manual (New York, 1873), 412-413;

Minutes of the Atlantic and Lake Erie

Railroad, Ewing, Sr., to Hugh Ewing, June 19, 1870,

Ewing, Jr., to unknown, December 10,

1872, Ewing Papers, LC; Cleveland Leader, July 25, 1871.

17. R. W. Jones to Ewing, Jr., May 15,

1873, Ewing Papers, LC.

|

Ewing section of the line would begin long before the mine owners could "manipu- late the interests in the Sunday Creek Valley & Dover Companies so as to realize the $95,000 of railroad obligations.... to prosecute the work." It was felt that care- less statements such as this would just breed cynicism in the towns along the line and make it much harder to sell the company's stock in the future.l8 Swigart also made a tactical error by clearly announcing the railroad's exact route before financing was assured. The towns that were not on the proposed route hoped that a change of management would lead to modifications in their favor, and they sought Swigart's resignation for this purpose. In the summer of 1873 the president was unable to gain a vote of confidence which he demanded from the board, and he submitted his resignation, effective as of August 10, 1873. He was succeeded by Valentine B. Horton.19 Under the presidency of Horton the A & LE became engulfed by the problems which beset all such enterprises during the depression of the 1870's. From 1869 to 1873 the company collected $375,566 from the sale of capital stock, but was able to place very little thereafter. The company used most of its money as it became available. When Horton became president the A & LE had about ninety-five miles of roadbed substantially graded in the section from Toledo to Bucyrus and in Lick- ing, Fairfield, and Perry counties in the coal region.20 After August 1873, the com- pany, lacking cash, was restricted to the employment of construction contractors who were willing to take their pay solely or largely in bonds. On March 26, 1874, the A & LE signed a construction contract with B. B. McDan- ald and Company of Toledo, with the intention that the latter build the entire line and receive payment in coal company bonds and A & LE mortgage bonds. W. C. Lemert, one of McDanald's partners, joined the board of directors of the A & LE in order to represent the construction company's interest. Work proceeded very slowly throughout 1874 and was marked by many delays because McDanald fre- quently lacked the funds to acquire materials and pay workmen. Another setback occurred when the company encountered unanticipated costs and engineering prob- lems in the construction of a tunnel. The coal companies had promised to deliver

18. James Taylor to Ewing, Jr., August 4, 1873, Ewing Papers, LC. 19. H. C. Cashart to Ewing, Jr., August 2, 1873; D. W. Swigart to Ewing, Jr., August 12, 1873, Ewing Papers, LC. 20. Vernon, American Railroad Manual, 413. |

Hocking Valley Railroads

269

bonds to McDanald, stipulating in turn

that the proceeds be used to build the seg-

ment through the coal lands.21 The

construction company refused to do any work

until it had the coal company and the A

& LE bonds-it clearly lacked the resources

to do otherwise. This meant there were

spurts of activity, as bonds were delivered

and used, and then costly delays until

more became available.

The A & LE was unable to arrange for

the payment of its bonds until September

25, 1874, when it signed a mortgage

agreement with a director of the Cincinnati

and Muskingum Valley Railroad. The

latter was a line controlled by the Pennsyl-

vania Company, ran in an east-west

direction north of the coal lands through Perry

County, and would intersect with the A

& LE near New Lexington. Under this

agreement the A & LE secured

$1,500,000 of seven percent bonds, payable January

1, 1880, by the mortgage of its

property. These bonds, however, did little to finance

the railway. In spite of numerous

attempts by various directors who traveled to

New York in attempts to negotiate the

bonds, and on the part of agents overseas,

the A & LE was unable to sell the

bonds or use them to pay for construction mate-

rials.22

By the end of 1874 the company faced the

critical decision of whether to continue

attempts to build the road or to

retrench; i.e., attempt to manage its floating debt

and wait for better times. If the first

decision were made, means had to be found to

accomplish the task. At the end of 1874

the railway was "almost graded" from the

coal field to Lake Erie, seven miles of

track were laid from New Lexington to Moxa-

hala, and the means were available to

complete the grade through the coal field. The

company had $331,000 due from unpaid

subscriptions, but at least one-half of this

could not be collected. The company's

floating debt, including balances due con-

tractors, was about $250,000. Enough had

been accomplished to have enabled

the company to negotiate its bonds under

normal conditions, but in the midst of

the depression this was impossible.23

After Swigart's resignation, Thomas

Ewing, Jr., V. B. Horton, and Charles Foster

formed a triumvirate which was largely

responsible for the decisions made by the

A & LE. For a time, at least, Ewing

enjoyed the confidence of the various factions

within the company, all of which

confided in him, sought his support, and were

encouraged by him to believe they had

his trust also. Even so, the enterprise suf-

fered, especially from April 1873 to May

1874, since Ewing neglected business to

devote his time to work as a delegate to

the Ohio Constitutional Convention and to

the advancement of his political career.

Ewing's absence partially accounted for

McDanald's delays, as his assistance was

necessary for the execution of the coal

companies' bonds.24

The coal mine promoters, led by Ewing,

emerged in 1874 as the strongest advo-

cates of the policy of pushing the

railway ahead to completion, even in the face of

21. "Sunday Creek Valley Mining

Company... Plaintiff vs. B. B. McDanald... and the Ohio

Central Railway Company," in the

Court of Common Pleas, Bucyrus, Ohio, copy in Ewing

Papers, LC.

22. J. B. Gormley to Ewing, Jr.,

December 17, 1874; mortgage agreement between the A &

LE and James Buckingham, September 25, 1874; G. B.

Johnson to Ewing, Jr., May 7, 1874;

W. C. Lemert to Ewing, Jr., July 30, 1874; Ewing, Jr.,

to J. R. Clymer, February 10, 1875,

Ewing Papers, LC. The last letter was written for

publication and circulation among stock-

holders and contains much history of the

events of 1874. The Pennsylvania Company was a

holding company formed by the Pennsylvania Railroad

Company in 1872. By 1880 it controlled

many railroads in Ohio.

23. Ewing, Jr., to Clymer, February 10,

1875, Ewing Papers, LC.

24. Jordan, Ohio Comes of Age, 17-19;

Lemert to Ewing, Jr., May 18, 1874, Ewing Papers, LC.

270 OHIO HISTORY

adversity. Their investments in land

were threatened by the depression, which

reached its trough nationally in 1875.

As one of the most important industrial states

in the nation, Ohio experienced severe

distress. Railroad mileage, which had in-

creased at the rate of 9.52 and 9.93

percent in 1872 and 1873 respectively (from

3,786.61 to 4,162.97 miles), dropped to

5.08 percent in 1874, 1.98 in 1875, and

minus 0.04 percent in 1876. Industrial

activity slumped rapidly after 1873 in Ohio's

mining regions and in its manufacturing

cities along the Ohio River. At the same time

national production of bituminous coal

had increased dramatically from 20,471,000

short tons in 1870 to 31,601,000 short

tons in 1873 and remained at this level for

the next few years. This high production

accompanied by reduced national indus-

trial activity in related fields in the

mid-1870's, sharply decreased the prices of Hock-

ing Valley coal and iron. Thousands of

men lost their jobs as scores of Ohio fur-

naces and mines shut down; other owners

cut wages and precipitated strikes by

their employees. Coal lands valued at

ten million dollars in 1872 were worth only

six million dollars in 1877.25 Caught in

the midst of this economic crisis, Ewing's

group realized that the probability of

failure was great if they tried to push the

A & LE to completion, but it was

also believed that inaction would certainly lead

to disaster. Money was still owed for

lands or mineral rights which had been pur-

chased, and the A & LE had a

floating debt of nearly a quarter of a million dollars.

"If the Company stop[s] where it

is, and wait[s] for better times," Ewing warned

in 1875, "it will be overwhelmed

with its floating debt. The Stockholders will then

lose all they have invested, and may be

called on to contribute more."26

In 1875 there was little chance of

getting any more financial aid from the stock-

holders. They had been disappointed

before, and construction was proceeding much

too slowly to arouse their enthusiasm

now. In Ewing's opinion, the best way to

continue the work was to contract for

the completion of the line with another con-

struction company which had access to

"a considerable amount of ready money

to put into the work, and who will take

pay exclusively in stock, bonds, and such

new subscriptions as may be

obtained." The search for such a company began in

the fall of 1874, when it became

apparent that McDanald was unable to construct

the entire line. Negotiations with a

construction firm headed by James Taylor, styled

the Ohio Construction Company, led to an

agreement by the latter to construct,

finish, and equip a first-class railway

on all sections of the A & LE except those

remaining under contract to McDanald.

The A & LE reserved the right to suspend

or annul the contract as it applied to

the line between New Lexington and Bremen,

and intended to do so if it could

arrange for the use of the Cincinnati and Muskingum

Valley Railroad. A fairly rigid

construction schedule was established, with work

to begin by May 15, 1875, and to be

totally completed by January 1, 1878.27

Before the contract could take effect,

the Ohio Construction Company demanded

25. Rendigs Fels, "American

Business Cycles, 1865-79" The American Economic Review,

XLI (June 1951), 344, fn. 55; Annual Report of the

Commissioner of Railroads and Telegraphs,

for the Year 1881 (Columbus, 1882), 7; U. S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census,

Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial

Times to 1957 (Washington, D.C.,

1961), 357;

John James, "The Miners' Strike in the Hocking

Valley," Cooper's New Monthly, I (July 1874);

Gutman, "Reconstruction in

Ohio," 248; Irwin Ungar, "Business and Currency in the Ohio

Gubernatorial Campaign of 1875," Mid-America,

XLI (January 1959), 28.

26. Ewing, Jr., to Clymer, February 10,

1875, Ewing Papers, LC.

27. Ibid.: contract between the A

& LE and the Ohio Railroad Construction Company, Jan-

uary 30, 1875, Ewing Papers, LC.

Hocking Valley Railroads

271

that the A & LE stockholders approve

a large increase in the company's stocks and

bonds in order to cover anticipated

construction costs. This was a crucial decision

for the company. Since the market for

securities was very weak, if placed at all,

the new securities would have to be

negotiated at far below par. Northern investors

such as Charles Foster were cautious and

opposed increasing the company's debt,

even if this meant some financial loss.

The mining interests, however, wanted to

gamble on being able to complete the

railway in hopes of avoiding losses entirely

and of placing in operation what

promised to be a lucrative enterprise. The later

position ultimately prevailed at a board

meeting on January 25, 1875, when a motion

to increase the A & LE's capital

stock was adopted unanimously. Directors Lemert

and Foster did not attend the meeting

and expressed misgivings about the policy.28

The proposal to increase the capital

stock and to execute a new mortgage to secure

$7,500,000 of permanent bonds met

opposition from some of the stockholders who

feared the action would plunge the

company hopelessly into debt and destroy its

equity. In an attempt to muster support,

the proponents of the stock increase pub-

lished letters in newspapers along the

line in which it was declared that an Ohio law

of 1873 allowed a company to issue bonds

up to two-thirds of its authorized stock.

Furthermore, the stock increase was to

the benefit rather than the detriment of the

current stockholders. If the company

failed, current stockholders would lose their

entire investment, while these

individuals' liabilities would in no way be affected

by the stock increase. This was also the

predominant sentiment prevailing at the

general stockholders meeting held on

March 17, and motions were passed author-

izing the stock increase and the

execution of a mortgage to secure new bonds.29

General Ewing was unanimously elected

president of the A & LE by the board

on March 18, 1875. In his effort to

build the railway, he faced several formidable

problems. As had the previous

presidents, Ewing had to deal with regional jealousy

and bickering. The northern interests justly

feared that the mine owners in the south

would arrange for an outlet for their

coal with one of the east-west lines that the

A & LE crossed at New Lexington or

Athens, and that once they had gained access

to markets they would adandon the rest

of the line. In spite of Ewing's assurance

that even if an outlet were secured at

Columbus or elsewhere, he intended "to stand

by the road until it is built, with all

the influence I can muster." His actions were

given close scrutiny by the northern

people who believed that his ownership of about

six thousand acres of coal lands as well

as his position as a director of many of the

mining companies constituted a potential

conflict of interest.30

Ewing's major problems, however, were

more general, and to a large extent be-

yond his control. In addition to the

general deflationary conditions caused by the

depression of 1873, investments in

railroads were discouraged by acute rate wars,

which reached their height in 1876, and

by crippling and sometimes violent strikes

which occurred in the Hocking Valley in

1874 (and would again in 1877). As a

result, federal, state, and local

governments were no longer inclined to aid railway

companies financially. Nationally, from

1872 to 1877 the prices of railroad stock

28. "Resolution of Board of

Directors of A. & L. E. Ry Co. as to increase of capital stock,"

Ewing Papers, LC. Board members present

were Ewing, S. L. Johnson, H. Pratt, J. S. Trimble,

W. Weethee, and V. B. Horton. All but

Pratt are known to have had investments in coal lands.

29. Ewing, Jr., to Clymer, February 10,

1875; "Proceedings of Stockholders Meeting Author-

izing increase of Capital Stock,"

Ewing Papers, LC.

30. Ewing, Jr., to Charles Foster, June

19, 1876, Ewing Papers, LC.

272 OHIO HISTORY

dropped from fifty to sixty percent, and

in 1875 almost 800 million dollars of rail-

road bonds were in default.31 In

this critical situation it was impossible for the

A & LE to negotiate its bonds for

cash, either in the United States or abroad, in spite

of vigorous efforts to do so. This point

was plainly stated by Daniel J. Morrell,

the wealthy owner of the massive Cambria

Iron Works at Johnstown, Pennsylvania,

whom Ewing had persuaded to invest in

the A & LE and in some of his mining

companies--provided he found suitable

co-investors:

I find it a very difficult matter just

now to interest business men in any enterprise, however

promising it may seem. Almost every one of

means who had ventured anything in min-

ing or manufacturing operations during

the last 4 or 5 years finds his property either lost,

or so depreciated in value as to be

almost worthless, & hence [is] over cautious now.

Others who have invested in R. R. securities--especially

the coal roads--are sadly

crippled and have no means to invest in

anything. I had a long talk with our friends

the Crocker Brothers, and with several

other good friends of mine, I found it much

harder to get them interested than I

expected. They . .. want to see that the prices are down

to hard pan & that the chances for

profit are sure.32

Ewing's strategy for dealing with the

depression had several components. First,

in an attempt to cut costs, arrangements

were sought for the joint use of segments

of other railways which were operating,

or in the process of construction, through

the region. Ewing was especially anxious

to come to terms with the Cincinnati and

Muskingum Valley Railroad because it was

threatening to build a branch line into

the coal field that would compete

directly with the A & LE. Negotiations between

the two companies began in April 1875,

and in June 1876 resulted in an agreement

in which the A & LE was to have use

of the track between Bremen and New Lexing-

ton, at an annual rate of four percent

of its appraised value plus a proportion of the

cost of maintenance based upon the

respective mileage over the segments by the two

companies involved.33 One

reason that a year was required to reach agreement was

that Ewing had to overcome opposition to

the scheme by northern interests in the

A & LE. Thus by the spring of 1876

the A & LE began operating seven and one-

third miles of line from New Lexington

to Moxahala, while to the north an additional

150 miles was graded but not laid with

rails.34 The completed line combined with

the C & MV to provide

facilities--albeit somewhat inconvenient ones requiring

transfers at short intervals--to mine

operators in the Moxahala region. This opened

"for development an extensive and

excellent coal field ... where mines were opened

sufficient to supply a large tonnage of

first class coal...." Ewing argued that the

arrangement with the C & MV would

not only add to the value of his coal interests

but to that of the railway as well. Once

part of the line was operating and actually

moving coal, it would be easier to place

the company's bonds. This position was

31. Fels, "American Business

Cycles, 1865-79," 347-348; Lee Benson, Merchants, Farmers

and Railroads: Railroad Regulation

and New York Politics, 1850-1887 (Cambridge,

1955);

Ewing, Jr., to unknown, August 11, 1877,

Ewing Papers, LC; Samuel Rezneck, "Distress, Relief,

and Discontent in the United States

during the Depression of 1873-78," Journal of Political

Economy, LXXXVIII (December 1950), 495-496; 0. V. Wells,

"The Depression of 1873-79,"

Agricultural History, XI (July 1937), 240.

32. D. J. Morrell to Ewing, Jr., June

18, 1877, Ewing Papers, LC.

33. Ewing, Jr., to William Thaw, March

23, April 21, 1875, April 15, 1876; Thaw to Ewing,

Jr., April 17, 21, 23, 1875; Minutes of

the A & LE Board, Columbus, June 17, 1876, Ewing

Papers, LC.

34. Annual Report, 1876, pp.

396-397.

Hocking Valley Railroads

273

sharply questioned by W. C. Lemert and

Charles Foster, who feared that once

this line through the coal field was in

operation efforts to complete the A & LE in the

north would be dropped.35 In

spite of opposition Ewing continued to make financial

arrangements to keep the enterprise

alive, but the A & LE discovered it was nearly

impossible to generate interest in the

railroad and gather stock subscriptions--and

it was even harder to collect on the few

subscriptions made. In fact from June 30,

1875, to June 30, 1876, the A & LE

was able to collect only $16,823.18 in addition

to the million one hundred thousand

dollars worth of stock already collected.36

By 1875 both the McDanald and Ohio

construction companies were in serious

trouble because they were unable to sell

A & LE or coal company bonds, acquire

material and equipment, or pay workmen.

Since all of the A & LE's assets were

mortgaged, the construction companies

were unwilling to take a lien on any part

of the railway. It was impossible to

secure bank loans, as western banks were "dry

as capons" and had no funds to

invest even had they desired to do so. One hundred

eighty thousand dollars cash was

"purloined by Lake Div." and hence lost to

McDanald, by "bloodsucking

parasites" who won a law suit against the A & LE in

Toledo. Thus, mounting debts, pressing

obligations, threatening law suits, and the

total inability to raise capital forced

the construction companies to surrender their

contracts late in 1875.37

After this, Ewing emphasized efforts to

complete the line through the coal field,

believing that if this part could be

placed in operation it would facilitate the capital-

ization of the rest. In October 1875, it

appeared that in spite of the many problems

confronting the A & LE, the portion

through the coal field might still be completed

because the strong New York construction

company of Vibbard, Platt, and Ball

took the project in hand. Chauncey

Vibbard, the senior partner, was an important

figure in nineteenth century railroad

industry. An imaginative, able organizer, Vib-

bard helped Erastus Corning effect the

consolidation of New York railways into

the New York Central, of which Vibbard

was general superintendent from 1853

to 1865. After resigning from the New

York Central in 1865 Vibbard engaged in

a variety of businesses, including

railroad construction and sales of railroad supplies.

A second partner, Thomas C. Platt, in

1874 a first-term Republican United States

congressman from New York with most of

an important political career ahead of

him, enjoyed a solid business reputation

as a druggist, lumberman, and banker. On

October 29, 1875, the proposal of the

firm of Vibbard, Platt, and Ball conditionally

contracted to build the northern section

of the A & LE line from Chauncey to To-

ledo, a distance of 194 miles, which it

estimated could be completed in eighteen

months. The A & LE agreed to furnish

all necessary supplies and to issue $25,000

of mortgage bonds to the construction

company for every mile completed.38

Ewing, on the other hand, wanted

Vibbard, Platt, and Ball to give the highest

35. Ewing, Jr., to Thaw, March 23, 1875;

to Foster, June 19, 1876; to T. C. Platt, June 18,

1876, Ewing Papers, LC.

36. One method used by Ewing to raise

money was to sell the heavily watered stock of the

coal companies, and the directors then

invested this money in A & LE securities. Also payment

dates were set when any stock was sold.

J. R. Straughan to Ewing, Jr., September 28, 1875,

Ewing Papers, LC; Annual Report,

1876, p. 396.

37. Lemert to Ewing, Jr., October 21,

1874; Ewing, Jr., to H. P. Clough, February 12, 1876,

Ewing Papers, LC.

38. John F. Parsons to Ewing, Jr.,

September 30, 1874, January 22, 1875; contract between

the A & LE and Vibbard, Platt, and

Ball, October 29, 1875; Minutes of the A & LE Board,

October 5, 1875, Ewing Papers, LC. The

contract would be effective only upon sale of the

A & LE bonds.

274 OHIO

HISTORY

priority to the completion of the

southern section of the railway through the coal

field, and he offered to negotiate a

supplemental contract, granting the construction

company an interest in the coal lands,

if it would vigorously pursue this objective.

He wrote:

Think of this. It is important to fully

develop the coal field as early as practicable....

If the mineral section be promptly built

& mines opened it will be vastly to the advantage

of the northern part of the line when

constructed.... The construction from Moxahala

to Chauncey will probably cost $150,000

cash.39

On November 23, 1875, Vibbard, Platt,

and Ball responded to Ewing by proposing

to contract absolutely for the thirty

miles of line between Moxahala and Chauncey,

to be completed within one year from the

execution of the contract. The A & LE

agreed to furnish "as fast as

required" all rights-of-way, ties, fences, a construction

train, and to pay in cash any cost of

the substructure over $150,000. In addition,

the construction firm was to be paid

$20,000 a mile in mortgage bonds, $20,000 in

cash, and $30,000 in monthly

installments as the work progressed between Moxa-

hala and Ferrara. The A & LE was

also to give the construction company $300,000

of full paid stock when the line between

Moxahala and Chauncey was completed,

and the mining companies had to then

convey to the construction firm 3,000 acres

of mineral lands, or the equivalent in

stock plus fifty dollars an acre in mortgage

bonds.40

The hope was that the firm of Vibbard,

Platt, and Ball could finance its opera-

tions by the sale of A & LE bonds.

Efforts to market the bonds overseas were inten-

sified as new agents were hired and the

promotional literature was revised. Pres-

ident Ewing prepared a prospectus which

probably conformed to the tenets sug-

gested to him by one agent:

If the bonds are sold abroad, the buyers

are about as ignorant of the country as you are

of central or south Africa, and they will

want to know every thing, & will ask more ques-

tions than a child. Puff your

directors--tell them who and what they are, and how

they stand--brag of your large

subscriptions . . boast of your minerals, of your mar-

kets, of the splendid district of

country the road passes through--tell them how much

has been spent and what has been done on

the line, & a thousand other things that will

occur to you. But stick to the truth,

as the chances are the purchasers of the bonds will

look closely into your statements.... 41

The most active agent for the A & LE

at this time was Dr. W. Ernest Friguet,

who became the center of controversy

between the construction company of Vib-

bard, Platt, and Ball and the A &

LE. He was a resident of Paris, with stockjobbing

offices there and in London. On October

28, 1875, the A & LE contracted with

Friguet for his services in selling

$6,250,000 of bonds in Europe. Friguet delivered

many optimistic reports to the company,

but as the months rolled on one effort

after another to arrange the loan

failed. In the meantime the construction company

exhausted its resources and work ground

to a halt. Chauncey Vibbard, who may

well have had better judgment in the

matter than Ewing, wanted to fire Friguet and

39. Ewing, Jr., to Vibbard & Ball,

November 9, 1875, Ewing Papers, LC.

40. C. Vibbard, A. H. Ball, and T. C.

Platt to the President and Board of Directors of the

Atlantic and Lake Erie Railway, November

23, 1875; to Ewing, Jr., November 23, 1875, Ewing

Papers, LC.

41. R. W. Jones to Ewing, Jr., May 9,

1875, Ewing Papers, LC.

Hocking Valley Railroads 275

hire someone else because he considered

the Frenchman "one of the most damnable

scoundrels in Europe" who had

"never succeeded in anything but in getting parties

to make advances upon his agreement to

negotiate securities, which he never ac-

complishes."42

Ewing continued to hold confidence in

Friguet, however, and he was following

the latter's advice in the spring of

1876 when he successfully proposed that the com-

pany's name be changed from the

"Atlantic and Lake Erie" to the "Ohio Central."

As Ewing explained, "the Atlantic

& Lake Erie contained two names of rather bad

repute in Europe--the 'Atlantic &

Great Western' & the 'Erie.'" He [Friguet]

suggested "'the Ohio Central' for a

like reason--to wit, that the Centrals were

generally of excellent repute--the Penna

Central, New York, New Jersey,

Illinois.... "43

Ewing's various promotional efforts

were, ultimately, all in vain as Ohio Central

bonds also proved to be impossible to

sell. By the summer of 1876 the company

was clearly on the verge of failure. The

report the A & LE (now Ohio Central)

filed with the Ohio Commissioner of

Railroads and Telegraphs in June 1876 revealed

how little had been accomplished in 1875

and 1876. Of the projected 237 miles

of line from Toledo to Pomeroy, 150

miles was graded but not laid with rails. From

January to June 1876 only nineteen miles

of main track were graded, three and

one-half miles ballasted, and 808 feet

of trestles built. The company had author-

ized $12,000,000 of stock, of which

$1,510,783 was subscribed, and $1,122,430

collected, mostly during the first years

of the company's existence. The Ohio Central

listed assets of $1,466,623, most of

which ($1,372,066) was in the form of real

estate and equipment. It is unclear how

the figure was derived, and, considering the

depressed condition of Ohio coal lands

in 1875-1876, probably was exaggerated.

Unfortunately, if the company's assets

were in part artificial, its debts were real. The

company had spent $1,372,066 on

construction, most of which ($784,255) was for

grading and masonry. Its net unfunded

debt was $224,967 and its funded debt--

secured with seven percent mortgage

bonds--had risen $44,600 in 1875. The

company was only operating a segment of

7.3 miles from New Lexington to Moxa-

hala. Nothing was going well for the

Ohio Central at this time, and the operation

of carrying 15,423 tons of coal and a

few passengers resulted in a net loss to the

company of $352.95 for the fiscal year

of 1875.44

When the A & LE was unable to place

its bonds, the Vibbard, Platt, and Ball

Company was released from its contract

for the Moxahala-Chauncey line and given

an extension to complete a shorter

Bremen-Granville section. The original contract,

providing for the construction of two

hundred miles of railroad in the north had

already expired because of the time

limitation. When more construction delays oc-

curred and it appeared that even the

Bremen-Granville line could not be completed

on schedule, one of the partners,

Vibbard, abandoned the project completely.

Thomas C. Platt and August Ball retained

an interest in the railway and worked

closely with General Ewing in an attempt

to salvage the enterprise. They still faced

a variety of problems, which in

combination ultimately proved insurmountable.

Throughout most of 1876 Ewing, Platt,

and Ball hoped to be able to finance con-

42. Ewing, Jr., to Hugh Ewing, May 25,

1875; Chauncey Vibbard to Ewing, Jr., June 12,

1876, Ewing Papers, LC.

43. Ewing, Jr., to Thaw, May 2, 1876,

Ewing Papers, LC.

44. Annual Report, 1876, pp.

396-399.

276 OHIO HISTORY

struction and at the same time maintain

control of the Ohio Central. This objective,

however, required financial

manipulation. Somehow more water had to be pumped

into the Ohio Central through new issues

of stocks and/or bonds. The company's

debts already were far in excess of

assets, and such a move was therefore opposed

by the company's many creditors.45

The efforts to manipulate the financial

affairs of the Ohio Central were successfully

thwarted by creditors and northern

opponents, who bombarded the company with

law suits in 1876 and 1877. This

situation made it impossible for the company to

withdraw bonds previously issued, or

otherwise place a new mortgage on the com-

pany. In January 1877, for instance, one

creditor forced the sheriff of Fairfield

County to auction $117,000 of Ohio

Central bonds, and soon thereafter the com-

pany's dock property in Toledo--valued

at over $20,000--was foreclosed by

another. The law suits had a snowballing

effect and threatened to destroy the com-

pany as all creditors tried to get

something before all of the assets were swal-

lowed up.46

The law suits and harassment by

creditors sharpened the conflict of interest

between President Ewing's Ohio Central

and mineral land enterprises. He decided

to try to salvage the mineral lands, and

thereby engendered hostile opposition from

most of the railroad's directors.

Because of this and also because he had been elected

to the national House of Representatives

in the fall of 1876 and would not be able

to devote himself fully to railroad

promotion, he indicated on June 12, 1877, that

he intended to resign from the

presidency of the Ohio Central. However, on July 9,

1877, before Ewing formally resigned, a

Crawford County judge appointed a re-

ceiver for the company in response to a

plea by McDanald and Company. Ewing

admitted that the action was justified,

and advised his colleagues against fighting it.

"The co is in fact insolvent &

unable to earn anything," Ewing informed Platt, "and

is in fact in such condition on our

showing our hand the Court... will not vacate

the order."47

At the time of the receivership action

assets of the Ohio Central consisted of a

roadbed and right-of-way between Toledo

and Pomeroy (about 230 miles); nearly

eight miles of completed line in Perry

County which was in operation; about twenty-

seven miles of roadbed laid with iron

but not ballasted from Bremen in Fairfield

County, north into Licking County; and

one locomotive and twenty gondola cars.

None of these assets produced the income

necessary for the Ohio Central to meet

the interest payments due on its bonds

and other current obligations. In fact, the

primary reason that McDanald forced the

Ohio Central into receivership was its

inability to pay interest on its bonds,

of which McDanald held a quantity with a par

value of $33,800 (with $4,085.29

interest due). The receivership petition made

several other complaints, all more or

less justified. The Ohio Central was getting

deeper and deeper in debt, and seemed

incapable of doing anything to get out. Its

floating debt was increasing at a rate

of about $50,000 a year, without any increase

in assets or in the value of the

property. The floating debt totaled $314,564.43 at

the time a receiver was appointed, and

the bonded debt stood at $1,113,789.91, in-

cluding both principal and interest.48

45. Ball to Ewing, Jr., April 12, 23,

28, 1877, Ewing Papers, LC.

46. H. D. V. Pratt to Ewing, Jr., May 1,

1877, Ewing Papers, LC.

47. Copy of letter of "T. E. to

members of B. of Directors, June 12, '77"; Ewing, Jr., to Edward

Pechin, July 16, 1877; "Order of

Court in Appointment of Receiver, July 9, 1877"; Ewing, Jr.,

to Platt, July 17, 1877, Ewing Papers,

LC.

48. "Referee's Report on

Receivership of Ohio Central, Bucyrus, Ohio, January 22, 1878,"

Ewing Papers, LC.

|

President Ewing was accused of "gross mismanagement and general dereliction of duty" because he refused to call a single stockholders meeting after May 1, 1876, thereby preventing the election of any new directors who might be hostile to him. Furthermore, Ewing refused to call any meetings of the board of directors after October 1876. Opposition to his actions was thus made more difficult for parties that wanted to complete the northern section before the mineral division. The Ohio Central neglected, or was unable to pay, some $800 in taxes due in Perry County, and the operating line was in danger of being sold by the sheriff to settle the tax bill. Ohio Central property in Crawford County had already been sold for taxes, and a valuable depot and dock property in Toledo had been lost to creditors "at less than one-half its original cost."49 Another justified complaint against the Ohio Central arose from the many delays in construction that left segments of the line in various stages of completion. Much of the roadbed was graded but not laid with rails, and most that did have rails was not ballasted. Such a line was difficult to maintain, especially while the company tried to devote any financial resources that became available to new construction. Many ties were not even piled up, but were scattered along the line where they rotted or were carried off by thieves. The Bremen-Licking County section went six months without ballast, and as a consequence deteriorated in value as embankments washed away and crumbled, excavations filled in, the superstructure settled, and the rails twisted. Bridges, ties, and culverts all suffered from the lack of proper care.50 There were several fundamental reasons for the failure of the Ohio Central. Its management was inexperienced in railroad building. This inexperience contributed

49. Affidavit of Thomas C. Hall in McDanald v. the Ohio Central, Crawford County, Ohio, July 7, 1877, Ewing Papers, LC. Hall was a partner in the McDanald Construction Company. 50. The State of Ohio, Crawford County, in the Court of Common Pleas, Bedan B. McDan- ald, Thomas C. Hall, Horace Rowse, James G. Frayer, and Wilson C. Lemert Plaintiffs v. the Ohio Central Railway Company, and James Buckingham and George T. M. Davis, Trustees, etc. Defendants, Ewing Papers, LC. |

278 OHIO

HISTORY

to several technical errors that cost

the company time and money, such as the accep-

tance of estimates on the costs of

tunneling which proved far too low, or the pur-

chase of iron rather than steel rails.

Also Thomas Ewing, Jr., underestimated the

severity of the depression of the 1870's

and the financial problems it presented.

Unwilling to lose some of his coal lands

by retrenchment, Ewing was able to make

his views prevail within the company.

Hocking Valley enterprise of all kinds was

frought with risks, and, considering the

economic conditions of the 1870's, it is far

from certain that different management

or different policies would have led to suc-

cess; but it is clear, in retrospect,

that Ewing's decisions were unwise.

Although the small-scale Ohio

industrialists who founded the A & LE railway

lost control of the enterprise in 1877

and were ostensibly failures, their efforts did

contribute to the emergence of the Hocking

Valley as one of the most important coal

producing sections of the country in the

1880's. Their work blazed the trail that

other, more realistic, men would

continue. Ewing's integrated approach toward

industrial development served as a model

for a syndicate headed by Samuel Thomas

of Columbus. Included were executives of

the New York Central Railroad Com-

pany, who acquired most of the A &

LE properties in 1877. This company, com-

bined with others to form the Columbus

and Hocking Coal and Iron Company,

emerged in the early 1880's as the

dominant firm in the eastern half of the Hocking

Valley. In an era when many mining

companies had assets of around one hundred

thousand dollars in value, the Columbus

and Hocking Coal and Iron Company op-

erated eighteen mines, owned over 12,500

acres of coal lands, 570 houses, a few

furnaces, and had an appraised value of

$4,494,367 in 1883.51 The firm achieved

in fact the economies of scale

envisioned by the earlier promoters of the A & LE.

The Thomas syndicate also acquired the

remains of the Ohio Central Railway.

Construction of the railroad resumed in

1879, was completed in November 1880,

and the name was changed to Ohio Central

Railroad Company. By June 30, 1881,

the Ohio Central was operating 213.3

miles of track, stretching from Toledo through

the Hocking Valley coal field. The

company reported "earnings" of $126,399.08,

or 37 percent over operating expenses

for the fiscal year 1881. In 1886 the Ohio

Central was partitioned, and passed out

of existence. The northern line became part

of the lucrative Toledo and Ohio

Railroad Company, while the section south of New

Lexington was absorbed by the Kanawha

and Ohio Central. The integration of

mines, railroad facilities, and company

towns forced the re-organization of the entire

mining industry in the Hocking Valley in

the mid 1880's, as independent operators

formed the Ohio Coal Exchange in an

attempt to compete with the Columbus and

Hocking Valley Coal and Iron Company.52

This suggests that in the 1870's the

promoters of the A & LE Railway

Company had vision and imagination, but suffered

from a combination of bad luck and the

absence of the entrepreneurial skill neces-

sary to translate dreams into reality.

51. Ewing, Jr., to Samuel Thomas, March

9, May 14, 1877; to H. D. Whitcomb, February 3,

1883, Ewing Papers, LC; John W. Lozier,

"The Hocking Valley Coal Miners' Strike, 1884-1885"

(unpublished M.A. thesis, The Ohio State

University, 1963), 36.

52. Tenth Census of the United

States, 1880: Report on Agencies of Transportation in the

United States (Washington, 1883), 336-337; Annual Report, 1881, pp.

1145-55; Eleventh Census

of the United States, 1890: Report on

Transportation Business in the United States (Washington,

1895), Part I, 76-77; Lozier, "The

Hocking Valley Coal Miners' Strike, 1884-1885," 37-38.