Ohio History Journal

|

THE HERO |

|

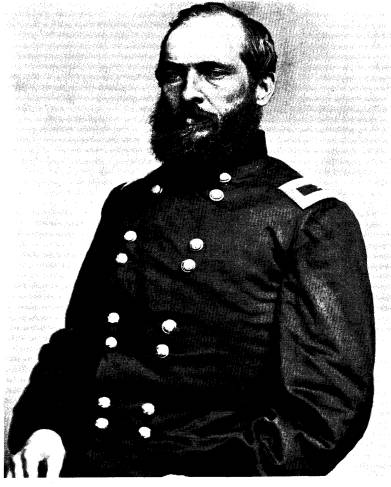

OF THE SANDY VALLEY JAMES A. GARFIELD'S KENTUCKY CAMPAIGN OF 1861-1862 by ALLAN PESKIN |

|

|

|

In the days when the Indians roamed at will through the mountains of Kentucky they instinctively dreaded this "dark and bloody ground." Later the white man came, first a cautious trickle through the passes, then a torrent of settlers with axes, rifles, and families. They cleared the forest, shot the game, and planted their families in cabins and cities. The Indians went away, and left Kentucky to civilization. But in 1861 Kentucky promised once again to be a dark and bloody land. On both sides of her borders hostile armies gathered. Alarmed Kentuckians, hoping to deflect the con- flict from her soil, declared the state "neutral." It was a fatuous attempt. Neither North nor South could afford to surrender Kentucky's strategic position. Well aware that "to lose Kentucky is nearly the same as to lose NOTES ARE ON PAGES 83-85 3. |

4 OHIO HISTORY

the whole game,"1 President

Lincoln quietly mobilized the Union sentiment

in Kentucky, while at the same time he

professed respect for her "neu-

trality." In September the

Confederates, suspecting that they had been out-

foxed, occupied Columbus, in western

Kentucky. Her soil invaded, her neu-

trality violated, Kentucky officials

called upon the North to expel the

aggressors.2

Kentucky was saved for the Union: but

would it remain saved? Con-

federate columns under the skillful

direction of Albert Sidney Johnston

massed on her borders, and Confederate

agitators were busy raising troops

even in those areas nominally under

Union control. Union commanders

followed one another in rapid

succession, but none stayed in Kentucky long

enough to organize its defenses. Not

even William Tecumseh Sherman, then

at his most eccentric, could provide the

effective leadership needed. Sher-

man, in fact, acted so strangely that he

was suspected of insanity and hastily

relieved of command.

He was replaced in November by Don

Carlos Buell. General Buell soon

realized that his command was little

better than an undisciplined rabble. His

officers were slovenly and ignorant of

war; the men poorly equipped and

poorly trained. Whatever may have been

his later shortcomings as a fighting

leader, Buell was the sort of martinet

Kentucky then needed. From his com-

mand post at Louisville he issued a

steady stream of orders: officers must

wear uniforms when on duty, reveille and

taps must be sounded at the

proper hours, troops must refrain from

looting--all these elementary but

essential procedures of military life

had to be firmly impressed upon his

raw soldiers. What was to become the

Army of the Cumberland began to

take shape under Buell's hand. Bolder

men would lead it to victory, but

Buell forged the instrument they would

use.3

Buell's strategic objective was

Nashville, but before he could safely move

into Tennessee he had to secure his left

flank. Two Confederate columns

were pushing through the mountains into

southeastern Kentucky. One, under

Felix Zollicoffer, had already marched

through the Cumberland Gap and

was menacing the interior. Buell sent his

most able lieutenant, George H.

Thomas, to block Zollicoffer's advance.

The other threat was less serious, but

it could not be ignored. Humphrey

Marshall, with a force rumored to exceed

7,000 men, had entered eastern Kentucky

through Pound Gap and was

making his way down the Sandy Valley.

Few less likely battlegrounds could be

imagined, for few regions had so

little worth fighting over. This was a

land that had scarcely changed since the

days of Daniel Boone; a land where

dulcimers still twanged out Tudor

|

|

|

ballads in their original purity; a land where mountaineers scratched a bare living wherever they could find enough level ground to pitch a cabin; a land of quick violence, where a word could lead to bloodshed and where feuds smoldered for generations with the intensity of Corsican vendettas; a land cut off from the rest of the nation, with no railroads and scarcely any roads at all. Because of the difficulties of terrain and supply, eastern Kentucky had little strategic value for either side. In the hands of the Confederacy, however, the region could become a thorn in the Union's side. Rebel raiding parties hidden in its valleys could threaten Buell's supply lines and delay his proposed advance into Tennessee. Despite its isolation the valley had already seen scattered fighting. Both sides had been anxious to secure its only natural resource -- manpower. Con- federate recruiters had raised over six hundred men before they were driven out by General William ("Bull") Nelson in November.4 Later that month Nelson had been recalled, leaving behind only a small garrison under Colo- nel Labe T. Moore. When Humphrey Marshall crossed the mountains in early December, Moore's force fled for safety, leaving the valley undefended. Buell could not allow Marshall to entrench himself on his flank. Without delay he ordered fresh troops to the Sandy Valley. These troops were the boys of the Forty-Second Ohio. |

6 OHIO HISTORY

The Forty-Second Ohio Volunteer Infantry

had been recruited and or-

ganized in the fall of 1861 by Colonel

James A. Garfield. Scarcely thirty

years old, Garfield had been serving his

first term in the Ohio Senate at

the outbreak of the war. A part-time

preacher for the semi-pacifistic Disci-

ples of Christ, and the president of the

Western Reserve Eclectic Institute at

Hiram, Garfield was as unversed in

military matters as most of his country-

men. Yet when he entered the army his

civilian experience proved remark-

ably appropriate to his new duties. He

recruited his regiment with the

techniques learned in the pulpit, and

once the regiment was assembled he

found that managing a thousand boys was

very much the same whether they

were in school or in uniform. The

similarity was intensified by the fact that

many of the soldiers of the Forty-Second

were recruited from the ranks of

his students at Hiram.

After a few months of training at Camp

Chase, on the outskirts of Col-

umbus, the Forty-Second had been drilled

to a neat military polish. But

when, in December, they were ordered to

the Kentucky front, they were

still as raw and untested as their

colonel. After an enthusiastic send-off at

Columbus, where Governor William

Dennison had reviewed the regiment to

the cheers of a patriotic crowd, the

boys of the Forty-Second were shipped

by rail to Cincinnati. There men, mules,

and supplies were stuffed into two

crowded steamers bound up the Ohio for

Catlettsburg at the mouth of the

Sandy River, the point where Ohio,

Kentucky, and West Virginia meet.5

Garfield left the regiment in the hands

of Lieutenant Colonel Lionel Shel-

don while he sped from Cincinnati to

Louisville to confer with Buell. His

first interview left Garfield favorably

impressed. "He is a direct martial

spirited man, and has an air of decision

and business which I like."6 The

general wasted no time on small talk or

preliminaries. Brusquely he told

Garfield that he had decided to put him

in charge of a brigade to deal with

the invasion of eastern Kentucky. Buell

airily confessed he knew little about

the country or the extent of the danger;

he left the details of the campaign

entirely up to Garfield, who was to

report back to Buell the next day with

a plan of operations.7

Garfield returned to his hotel room

almost overwhelmed by the responsi-

bility which Buell had so casually

thrust upon him. He had never seen a

battle, "never heard a hostile

gun."8 He was not a soldier, only a country

schoolmaster who dabbled in politics,

and now he found himself with an

independent command in a strange wild

country, bearing sole responsibility

for the success or failure of what could

be a vital campaign against an un-

known enemy. All that night he paced the

floor alone, turning plans over in

THE HERO OF THE SANDY VALLEY 7

his mind. The more he studied a map of

the region, the more appalled he

became. His command embraced six

thousand square miles of wilderness

untapped by railroads or telegraph

lines. The land was too desolate to sup-

port an army even in the best of

seasons, and certainly not in winter.9

Supplies would hold the key to the

entire campaign. And here, the one-

time canal boy instantly realized, was

where he had the advantage. So long

as he held to the river he could bring

supplies up from the Ohio by water,

while Marshall would have to haul every

item painfully over the mountains

from Virginia. Marshall's advance,

therefore, would be slow. Garfield could

meet him in the valley, block his advance

with part of his brigade, and

send another part around the mountains

to trap him and cut off his retreat.

Garfield spent the rest of the night

working out the details of his campaign.

The next morning he reported to Buell.

Buell listened impassively, without

comment or question. Garfield anxiously

watched his face, but Buell did not

betray his opinion by so much as a

raised eyebrow. The plan must have

pleased him, for Garfield's orders the

next day were nothing more than an

elaboration of his own ideas.10

Now the Eighteenth Brigade, Colonel

Garfield commanding, had only to

be set in motion. The Forty-Second Ohio

would join with what remained of

Colonel Moore's Fourteenth Kentucky and

proceed up the valley until they

met the rebels and blocked their

advance. Meanwhile, the Fortieth Ohio,

then at Paris, Kentucky, under the

command of Colonel Jonathan Cranor,

was to march east from Paris overland to

the upper Sandy Valley, where,

with luck, it would sneak behind the

rebel rear at just the proper time and

place, and crush them in a nutcracker

movement. To round out the brigade,

Garfield was assigned four squadrons of

cavalry, mostly Kentuckian, while

the Sixteenth Ohio Infantry was held at

Lexington as a reserve.1l Much to

his dismay, Garfield was given no

artillery. Buell insisted that artillery in

that rough country would only prove a

hindrance,12 but Garfield, uncon-

vinced, continued to pester him for field

guns at every opportunity.13

The rapidity with which things were

happening to him left Garfield breath-

less. He hardly knew what to make of his

new job. He regretted being

separated from his boys of the

Forty-Second for even a short time.14 He

would have preferred to remain as their

colonel in a subordinate position in

the main column, but Buell consoled him

with the thought that an independ-

ent command offered greater opportunity

for distinction.15 Neither Buell nor

Garfield mentioned what must have

crossed both their minds: that the op-

portunities for conspicuous failure were

equally great.

Garfield did not have much time to brood

over the matter. The situation

8 OHIO HISTORY

in the Sandy Valley was deteriorating

rapidly. According to rumor Marshall

had already reached Prestonburg, and

Colonel Moore's Fourteenth Ken-

tucky had retreated to Catlettsburg.

Garfield hastily assembled his staff,

ordered supplies, engaged Union

sympathizers familiar with the region to

act as scouts, and hopped on board the

steamer Bay City for Catlettsburg.16

Before he left Louisville, Buell gave

him some parting advice and washed

his hands of responsibility.

"Colonel," he said, "you will be at so great a

distance from me and communication will

be so slow and uncertain, that I

shall commit all matters of detail, and

much of the fate of the campaign, to

your discretion."17 Garfield was on

his own.

While Garfield was busy in Louisville,

his regiment was invading Ken-

tucky. After an acutely uncomfortable

voyage the Forty-Second Ohio had

steamed into Catlettsburg on December

19. The Fourteenth Kentucky,

dressed in splendid sky-blue uniforms,

lined the shore and greeted its arrival

with cheers of welcome. The Ohio boys,

glad to be on land once more, dis-

embarked and unloaded their baggage from

the steamer. For the rest of the

day Catlettsburg was a busy, bustling

place: mules were coaxed ashore,

wagons loaded, tent stakes pounded into

the hard ground, and by sunset a

sea of white tents covered the area, and

coffee pots were bubbling over camp

fires. It was all new and exciting. The

boys of the Forty-Second had never

slept in tents before and they relished

the experience of camping in a hostile

country. No enemy was nearby, but

sentries were posted, and, as a private

fondly recalled, "we began to

assume the airs of Veteran soldiers, if Vet-

erans have airs peculiar to them."18

The next day the brigade set out for

Louisa, some twenty miles up the

Big Sandy. Their line of march, so neat

and simple on the map, was

furrowed by ridges, hills, and valleys.

Roads were a map-maker's fiction;

only bridle paths ran through this

country. The 150 mules brought from

Ohio were not yet broken to the harness,

and until they were (with language

which must have disturbed Chaplain

Jefferson H. Jones) the baggage wagons

had to be pushed painfully up each hill.

Superfluous baggage was dumped

by the roadside: discarded mess chests

marked the path of the Forty-Second

Ohio through Kentucky. Then it began to

rain -- a cold, pelting rain, almost

sleet. The men hunched under their coats

and slogged through the mud.

There were no bridges, and swollen

streams coursed through every ridge and

gulley. One perversely twisted creek had

to be crossed twenty-six times in

five miles. It took two full days to

reach Louisa. The march was long re-

membered as "a thirty mile

wade."19

Garfield caught up with his sodden

troops at Louisa in time to administer

10 OHIO HISTORY

a moral lesson. His tired, hungry men

had been unable to resist the tempta-

tion of foraging in Louisa's unguarded

pastures. Amid the squawks of terri-

fied chickens, "poultry, pigs and

fences . . . passed away like a dream."

Suddenly the drums sounded the long

roll, and the regiment, sensing trouble,

ran to assemble at attention. They

formed a hollow square in front of their

colonel, who looked down on them from

his horse with obvious anger.

Men of the Forty-Second [he said], I

thought when I left our old Buckeye

State at the head of this fine-looking

body of soldiers, that I was the proud

commander of a Regiment of gentlemen,

but your actions this evening, were I

not better acquainted with each and all

of you, would bitterly dispel that illusion.

Soldiers, we came to Kentucky to help

her sons free her sacred soil from the

feet of the rebel horde.... Show these

Kentuckians, who are your comrades

under one flag, that you did not come to

rob and steal . . . and hereafter I shall

believe that I command a regiment of

soldiers, and not a regiment of thieves.

The chastened soldiers slunk away,

leaving behind a mound of cabbages,

hams, and corn meal. "In our

simplicity," one of Garfield's light-fingered

men recalled, "we then thought it

wrong to confiscate rebel property, but as

time moved on and our faces became

bronzed, so also did our conscientious

scruples, and we totally forgot the

moral teachings of Colonel Garfield."20

The next day the rain turned to snow.

After spending a sleepless night

huddled around the camp fires for

warmth, the brigade prepared to move

further south. Wagon wheels spun

helplessly on the ice, and the baggage had

to be loaded onto flatboats and poled up

the river.21 Sticking close to the

river so as not to be cut off from its

supply line, Garfield's brigade pushed

step by weary step to the source of

George's Creek, a branch of the Big

Sandy. There they established a base,

called Camp Pardee, and waited for

their stores to catch up with them.

"It is the worst country to get around in

I ever saw," Garfield complained.

"There is not room enough to form a

regiment in line, for want of level

ground."22

Meanwhile, as the Eighteenth Brigade was

toiling up the valley, Hum-

phrey Marshall was slowly advancing from

the south to meet Garfield and

his "damn Union Psalm

singers."23 Marshall's expedition had fared badly

from the first. Although he was an

experienced soldier with a West Point

education and a distinguished Mexican

War record, General Marshall was

a poor choice for this assignment. His

mission required speed and daring,

but Marshall's three-hundred-pound bulk

and his cautious temperament ren-

dered success unlikely. Petulant with

his superiors, indulgent with his men,

Marshall inspired affection but not

respect. Discipline inevitably sagged:

one disgruntled aide volunteered to eat

the first man Marshall should shoot

for a crime.24

|

|

|

Marshall had been selected for his political connections rather than his military prowess, and from the start he allowed political considerations to interfere with his main task. He had been ordered to Kentucky as early as November 1, so as to reinforce the Confederate garrison then retreating before Bull Nelson.25 But Marshall, who felt slighted by the command ar- rangements, particularly the precedence given to General George Crittenden, a political rival, halted his brigade in Virginia while he shot off angry letters to his high-placed friends. Eventually the matter was settled to his satisfaction, and on December 11 he finally crossed the mountains into Kentucky. By this time, however, the troops he was supposed to rescue had already been routed while he was busy squabbling with Crittenden. Unper- turbed, Marshall continued his advance. His command consisted of about 3,000 men from Virginia and Kentucky units. The brigade was deficient in cavalry, with only one battalion of 400 mounted men, but it did have an asset which Garfield coveted -- an artillery battery of four pieces.26 A cold, wet winter had set in by the time Marshall was ready to move. He had come to liberate Kentucky's sacred soil; instead he was in danger of being swallowed by Kentucky mud. His artillery, sunk axle-deep in the quagmire, slowed the entire advance. It took three full days to drag the guns six miles.27 The weather took its toll on the soldiers. They were a scraggly band of liberators. Many marched barefoot, few had blankets, and |

12 OHIO HISTORY

almost none wore overcoats.28

Even to friendly observers they seemed

"ragged, greasy, and dirty . . .

more like the bipeds of pandemonium than

beings of this earth." Trying to

live off the land in a region that could barely

support its own inhabitants, Marshall's

hungry men turned into an army

of beggars. A charitable group of

Shakers was appalled to see these soldiers

fight one another over a loaf of bread.

"They surrounded our wells like the

locusts of Egypt," the Shakers

complained, ". . and they thronged our

kitchen doors and windows, begging for

bread like hungry wolves."29

Exposed to the elements, weakened by

hunger, many of Marshall's soldiers

succumbed to such unmilitary maladies as

the measles, and even Marshall

himself suffered the indignity of mumps.

Out of the 3,000 men who had set

out from Virginia, less than 2,000 were

fit for combat.30 Marshall, whose

heart, according to an aide, was

"tender as a woman's," suffered along with

his men. He often gave up his tent to

the sick, and made his bed on the

ground under a wagon.31

"I sometimes wonder," Marshall

asked himself, "why I undergo all this

exposure and hardship?"32 I was a

good question, and one which must have

puzzled the Confederate high command as

well. Marshall's expedition had

almost no military justification. He

could not use the valley as a base from

which to launch raids behind Buell's

lines, for he lacked sufficient cavalry.

In his reports to headquarters he

outlined grandiose plans for dashing into

Kentucky, destroying railroads, and

wreaking general havoc, but these plans

depended on a large mounted force that,

he lamely suggested, would have

to be raised "in some way."33

At other times Marshall spoke as if he re-

garded his campaign as nothing more than

a recruiting expedition. He ap-

parently believed that once he set foot

upon his native soil, the supporters

of his cause would flock to his

standard. He was disappointed. Confederate

recruiters had already skimmed the cream

of southern sympathizers from

the valley. Those left behind were

mostly indifferent to the struggle.34 Even

if Marshall found a large body of eager

volunteers, how could he arm them?

Many of his own soldiers were without

weapons. He had a few good Belgian

rifles, but most of his men carried

nothing more deadly than shotguns or

squirrel rifles. General Robert E. Lee

sympathized with Marshall's plight,

but he too had no rifles to spare. The

best he could do was to offer to supply

Marshall with pikes.35

By early January, Marshall had inched

his way to Paintsville, only

eighteen miles from Garfield's camp on

George's Creek. Advance scouts

from both sides traded shots and

scurried back to base with the news that

a large enemy force was nearby. Marshall

frantically dug in, fortifying the

THE HERO OF THE SANDY VALLEY 13

approaches to Paintsville to meet the

expected assault. His position was

difficult. He could, conceivably, dash

forward, surprise Garfield, and smash

his way through his lines, but this was

risky. And even if it should succeed,

what could Marshall do then, except

continue his aimless advance, with

each step carrying him further from his

base of supplies and closer to the

enemy? He could sit in Paintsville and

wait for the enemy to attack, but

supplies and morale were too low to

survive a lengthy siege. To retire without

a fight would be shameful, so Marshall

decided to hold the line at Paints-

ville for the time being and hope for

the best. If dislodged, he vowed he

would strike for the interior of

Kentucky "and rouse the country as I go or

fall in the effort." At all costs

he had to avoid the humiliation of a retreat

from his native state, "for I know

that if I am driven over the mountains

again," he told his commander,

"our cause in Kentucky is lost."36

Garfield too was in a quandary. From the

reports of his scouts and spies

he had pieced together a reasonably

accurate picture of the forces moving

against him. He knew that Marshall had

between 2,000 and 2,500 men en-

trenched behind the Paintsville

fortifications, and an additional three or

four hundred cavalry at a separate camp

on Jenny's Creek.37 He also knew

that his own force was pitifully weak in

comparison. His only reliable

soldiers were the thousand well-equipped

but green recruits of the Forty-

Second Ohio, and about five hundred

poorly armed Kentuckians in Colonel

Moore's regiment. Most of the Kentucky

units in his command were "little

better than a well disposed,

Union-loving mob," while his "demoralized,

discouraged" Kentucky cavalry,

untrained and unarmed, was worthless for

any task more demanding than scout

duty.38 The Fortieth Ohio under Colonel

Cranor, which was supposedly hurrying with

reinforcements, was lost some-

where in the Kentucky mountains.

Garfield had heard no word from Cranor

from the time he left Louisville until

January 1, when a weary scout stag-

gered into camp with the news that

Cranor was still about a week's march

away.39

According to a popular military maxim of

the day, which Garfield must

have known, an attacking force was

supposed to outnumber the defenders by

about three to two. By this rule of

thumb Garfield needed three or four

thousand men rather than the 1,500 he

could muster. Furthermore, he keenly

regretted his lack of artillery and was

convinced that without it he could not

dislodge Marshall.40

Had Garfield been looking for excuses to

justify inactivity, he could

certainly have found enough to satisfy

even Buell. Instead, Garfield, a

strong believer in "the success of

vigorous and well directed audacity," was

14 OHIO HISTORY

eager for action. Overriding the

cautious protests of his officers at a council

of war, he prepared to advance on

Marshall's works.41 Enraptured with the

prospect of capturing an enemy army, he

brushed aside all objections. "I

cannot tell you how deeply alive to the

scheme in hand are all the impulses

and energies of my nature," he

wrote his wife. "I begin to see the obstacles

melt away before me, and the old feeling

of succeeding in what I undertake

gradually taking quiet possession of

me."42

Too impatient to wait for the Fortieth

Ohio to catch up with him, he

ordered Cranor to cut south in the

direction of Prestonburg. This would

bring Cranor's regiment into the valley

about ten miles south of Marshall's

camp at Paintsville.43 Garfield

was still obsessed with his original plan of

surrounding and trapping Marshall's

force. However Napoleonic this scheme

may have seemed in his eyes, it was

actually the height of recklessness.

Cranor's regiment united with his own

would have given his brigade a rough

equality with the enemy. Instead,

Garfield chose to divide his force in the

face of an enemy superior to each of his

columns. Garfield was allowing

a fortified enemy to come between his

right and left wings -- in effect, de-

liberately allowing himself to be

flanked. To make matters worse, he had

made no provision for cooperation

between Cranor and himself. Indeed, he

was not even sure of Cranor's location

nor of the condition of his regiment.

Rather than trapping Marshall, the most

likely result of this maneuver would

be the destruction of Garfield's own

army should Marshall be so unobliging

as to attack each of Garfield's isolated

wings before the trap closed. When

Garfield looked back on his campaign in

the years after the war, he shud-

dered at his folly. "It was a very

rash and imprudent affair on my part," he

admitted. "If I had been an officer

of more experience, I probably should not

have made the attack. As it was, having

gone into the army with the notion

that fighting was our business, I didn't

know any better."44

In the comedy of errors which

constituted the eastern Kentucky campaign,

Garfield held the advantage. His

mistakes resulted from a weakness for elab-

orate plans and combinations, but

Marshall had no plan at all. It has been

said that God judges the sins of the

warm-blooded and the sins of the cold-

blooded on a different scale. Garfield

was a warm-blooded commander. He

may have been impetuous and

over-optimistic, but he was not afraid to take

a chance, and he was resourceful enough

to exploit good fortune when it

came his way. Marshall, huddled behind

his trenches, allowed his opponent

to seize the initiative at every turn.

Marshall's works were thrown up at the

foot of a hill on the main road

three miles south of Paintsville. Three

roads led into Paintsville. Uncertain

THE HERO OF THE SANDY VALLEY 15

which approach Garfield would take,

Marshall posted pickets on each road

about a half mile above the town. Within

the town he stationed a regiment

of infantry and his artillery battery,

ready to rush to the defense of which-

ever route should be threatened.

By January 4, Garfield had reached the

outskirts of Paintsville. Cranor's

location was still a mystery, but a

timely cavalry reinforcement had brought

the Eighteenth Brigade to something

close to full strength. This cavalry

squadron actually belonged to Garfield's

political crony Jacob Dolson Cox,

now a major general in charge of

operations in the neighboring Kanawha

Valley. Cox, a good neighbor, lent some

of his cavalry, commanded by Lieu-

tenant Colonel William M. Bolles, to his

friend for a few days. The tem-

porary nature of these reinforcements

gave urgency to Garfield's moves; he

could not afford a long siege but had to

dislodge Marshall while he still had

the loan of this squadron of cavalry.

But which road should he take? Gar-

field decided on deception. On the

morning of January 5 he divided his

forces into three small detachments and

sent them down each of the roads,

placing cavalry in front to mask their

size. The first group rode down the

river road on the left. When they

encountered the Confederate pickets, they

made a show of noise and activity. As

expected, the pickets reported their

movements to the regiment in town, which

came charging up the road to

their defense. About an hour later

Garfield's second detachment made a

similar demonstration against the

pickets on the hill road at the right.

Marshall's reserve regiment wheeled

about to march to their aid. When they

reached the left flank they heard of the

attack on the center. Marshall's forces,

weary from scurrying from threat to

non-existent threat, were now convinced

that a large army was moving against

them on all three roads. They fled to

the security of their entrenchments in

wild panic, leaving Paintsville de-

serted.45

Behind his earthworks Marshall nervously

peered up the road for signs

of the approaching enemy. While he was

waiting, messengers brought reports

of Cranor's force closing in on his

position from the east. Even though

Marshall was operating in supposedly

friendly country, his intelligence

reports continually misled him. He

believed the most exaggerated rumors

of Garfield's strength. Prudent by nature,

Marshall easily convinced himself

that his position was untenable. Leaving

his cavalry behind to disguise his

intentions, he packed his wagons, burned

what he could not carry, and re-

treated up the valley.46

This was the decisive moment of the

campaign. From this point on Marsh-

all could only keep retreating, with no

logical place to stop this side of

16 OHIO HISTORY

Virginia. Garfield's only task would be

to prod him along more quickly.

It was fortunate for Garfield that

Cranor did not obey his order to block

Marshall's line of retreat, for if

Marshall had been trapped he would have

been compelled to stand and fight.

Instead, Garfield gained his objective

without firing a shot. The bloodless

victory at Paintsville was the true turning

point. The more spectacular action which

followed was all anticlimax.

Unaware that the enemy had flown the

"trap" he was setting, Garfield

picked his way cautiously through the

empty streets of Paintsville. He dis-

patched his borrowed cavalry up Jenny's

Creek to ferret out the rebel cavalry

encamped there, while with the rest of

his men he edged toward Marshall's

fortifications. Night had already fallen

on the evening of January 7 when

Garfield finally entered the deserted

earthworks. He was struck by the signs

of Marshall's hasty exit -- "their

camp fires were still smoldering, and the

scattered remnants of their stores lay

in sad confusion. The frozen tracks of

thousands of feet were plain under the

light of the new moon."47

He had barely time to savor the

experience of sitting at Marshall's desk

when an urgent message came from Colonel

Bolles that he had contacted the

enemy cavalry. Garfield ordered him to

hold off his attack until he came

to his aid. He assembled a detachment of

four hundred men, ferried them

across the Big Sandy on flatboats, and

then struck out across the hills for

Jenny's Creek. The plan was his old

favorite -- the flanking movement.

While Colonel Bolles engaged the enemy's

attention, Garfield would sweep

behind them and attack their rear.48

Even under ideal conditions this type of

maneuver (to which Garfield seemed

addicted) required delicate timing;

at night, through unfamiliar country,

its success was doubly uncertain.

Garfield's men marched for thirteen

miles, "wading streams of floating

ice, climbing rocky steeps, and

struggling through the half-frozen mud,"

until ready to collapse.49 Jenny's

Creek, swollen by the recent snows, had

to be bridged at two separate points.

Garfield himself stood waist deep in the

swirling water as he directed the

construction.50 They reached the junction

point at midnight, only to find the

enemy gone. Instead of waiting for Gar-

field to arrive, Colonel Bolles had

attacked and dispersed the rebel cavalry

on his own, killing six, wounding

several more, and so scattering them that

they were of no further use to

Marshall.51 Garfield's march had been a wild

goose chase, and his half exhausted

soldiers had to turn around and trudge

the thirteen miles back to camp. As they

marched, they grumbled about their

officers, "mounted on good

horses," who rode in comfort. Some of the men,

unable to take another step, lay down

behind fences, and would have frozen

to death had they not been prodded awake

and forced to move on.52 As they

THE HERO OF THE SANDY VALLEY 17

neared camp, a volley of bullets from

the hills drove them scurrying for

cover. This was the Forty-Second Ohio's

baptism of fire, but the circum-

stances were far from heroic, since the

barrage was from their own advance

pickets who had mistaken them for the

enemy.53

Returning to camp, they found that

Colonel Cranor and the Fortieth Ohio

had arrived during their absence. Wisely

disregarding Garfield's order to

move towards Prestonburg across the

enemy's line of retreat, Cranor had

gone to Paintsville instead, where he

could join the rest of the brigade. His

arrival was timely, for it coincided

with the departure of Colonel Bolles's

borrowed cavalry. Worn out by their long

march across Kentucky, Cranor's

men needed rest before they could be of

much use, but the impatient Gar-

field could not wait. As he saw Marshall

slip from his grasp, he yearned to

pursue: "I felt as though we had .

. . out-generalled the enemy, but I was

unwilling he should get away without a

trial of our strength."54 He as-

sembled all of his men who were fit to

march, about 1,100 in all, stuffed

their haversacks with three days'

rations, and at noon on January 9 moved

up the river road. "I fear we shall

not be able to catch the enemy in a

'stern chase,' " he said, using the

jargon of his boyhood canal days, "but

we shall try."55 Resorting

once again to his pet flanking maneuver, he dis-

patched his cavalry to follow the

enemy's line of retreat, while Garfield at

the head of his foot soldiers planned to

take a roundabout route to cut off

their retreat.56

The pursuit was hampered by cold, sleety

rain, and later by the steady

harassment of Marshall's rear guard.

Felled trees blocked their path, and as

they climbed over these obstructions,

hidden snipers fired pot shots and

then melted back into the hills. These

wild volleys did no damage, but Gar-

field, now alert to danger, picked his

way "inch by inch" up the valley to

the mouth of Abbott's Creek.57 As

the tempo of skirmishing increased, Gar-

field realized that he was approaching

the main body of Marshall's forces,

and that a battle was imminent. He sent

a courier back to Colonel Sheldon at

Paintsville with an urgent order to

bring reinforcements. Shortly after dusk

he led his men to the top of a high hill

overlooking Abbott's Creek, where

they bedded down for the night. The

enemy was too near to permit the

luxury of camp fires. Wrapped in their

greatcoats, Garfield's men shivered

through the night as an icy rain beat

down upon them.58

That same night in Marshall's camp, the

dispirited, retreating rebels de-

cided they had had their fill of

Kentucky. A round robin signed by Marshall's

company captains urged him to quit the

state for winter quarters in Virginia

or Tennessee.59

|

18 OHIO HISTORY At three o'clock on the morning of January 10 Garfield roused his men. After scraping the ice from their sleet-stiffened clothes, they ate a cheerless breakfast and within an hour were on the move once more. To Garfield, that morning presented "a very dreary prospect. The deepest, worst mud I ever saw was under foot, and a dense, cold fog hung around us as the boys filed slowly down the hillside."60 From the reports of local inhabitants, Garfield had gathered the impression that Marshall's main force was encamped some miles up Abbott's Creek. He therefore pushed on to Middle Creek, the next river upstream from Abbott's, hoping to entrench himself in a strong position across Marshall's line of march. As he moved up Middle Creek, signs of rebel activity became more frequent: shots were exchanged regularly, and a prisoner fell into his hands. Near midday Garfield reached the Left Fork of Middle Creek. As he rounded the point of a hill he saw before him a level plain filled with rebel cavalry who charged towards him and then fell back to the protection of a nearby ridge. Instead of cutting off Marshall's retreat as planned, he had stumbled across the main body of the enemy.61 Garfield drew his column to a halt and surveyed his position. Middle Creek ran through a deep, twisting valley, which occasionally broadened into an open stretch of level ground. The hill which Garfield's advance guard had just rounded commanded one end of such a plain. Half a mile across the valley rose a steep, crescent-shaped ridge, somewhere behind which Marsh- The battlefield of Middle Creek |

|

|

THE HERO OF THE SANDY VALLEY 19

all's forces lay deployed. It was a

strong defensive position, with the ad-

vantages of terrain and concealment in

Marshall's favor. Garfield sent two

companies up the slope of the ridge on

his side of the valley to clear it of

any rebels who might be stationed there.

While they were climbing up the

hill, Garfield in the valley below

fretted with impatience. Too keyed up to

stand passively by, he ordered the rest

of his troops into battalion drill,

"for the sake of bravado and

audacity," as under the eyes of the puzzled

Confederates they wheeled and marched as

if on parade.62 By marching his

men round and round the base of the hill

Garfield also hoped to give the

watching Confederates an exaggerated

impression of his forces. Apparently

the deception succeeded, for Marshall,

never one to minimize difficulties,

was convinced that Garfield commanded at

least 5,000 men.63

Assured by his scouts that the hill was

unoccupied, Garfield transferred

his command post to the top,

on a peak ominously named Grave Yard Point.

His next step was to determine the

precise location of the enemy, but Gar-

field's cavalry, which should have been

responsible for reconnaissance, was

still off somewhere chasing Marshall

down the wrong valley. Garfield had

to make do with what he had. He ordered

his personal mounted escort, less

than a dozen men in all, to ride across

the plain in the hope of drawing the

enemy's fire. As expected, Marshall's

green troops nervously blazed away

long before the riders came within

range, revealing their position.64

The enemy's salvo had scarcely ceased

reverberating before Garfield

launched two Kentucky infantry companies

under Captain Frederick A. Wil-

liams across the valley to dislodge the

rebels. Holding cartridge boxes and

rifles above their heads, they waded the

icy, waist-deep creek, and dashed

towards the opposing ridge. This was the

opportunity for which Marshall's

artillery captain had been waiting. For

a month he had nursed his precious

guns, hauling them over mountains,

tugging them through mud, and de-

laying the advance of the entire

brigade. Now, all his work could be justi-

fied. He zeroed in on the charging

federals, waiting until they reached point-

blank range before pulling the lanyard.

With a high-pitched scream a twelve-

pound shell lobbed high in the air,

headed unerringly for Williams' ad-

vance guard --- and plopped harmlessly

into the mud. Marshall's shells were

all duds, and although his cannon boomed

noisily away throughout the rest

of the afternoon, they inflicted no

damage other than splattering a few fed-

erals with mud.

When Garfield's line had crossed the

valley, they reached a virtually

perpendicular ridge. Grabbing hold of

projecting limbs and roots, they

scurried up the hillside as best they

could. The hill was too thickly wooded

20 OHIO HISTORY

to permit elaborate tactical maneuvers.

Each man climbed and fought at his

own speed, firing and reloading as he

advanced. From the safety of a large

clump of rocks at the top of the ridge,

the rebels let loose volley after volley

at the exposed Union line, but the steep

downhill angle of fire, combined

with the natural tendency of green

troops to aim high, caused most of their

bullets to whiz wildly over their

enemies' heads. Their fire inflicted a fearful

toll on tree branches and low-flying

birds, but it left Garfield's men virtually

unscathed. Eventually they worked their

way to the top of the hill, close

enough to exchange curses as well as

shots. Every now and then a group of

rebels would detach themselves from

their sheltering boulders and dash down

the hillside. The Union troops would

then fall back for a while, and then

climb up once more.

This was the pattern of the day's

fighting: a succession of uncoordinated

charges and withdrawals, with a great

deal of shooting and very little blood-

shed--"a regular 'bushwhacking'

battle."65 Garfield handled his troops with

little imagination or enterprise,

throwing them against the rebel line in

driblets, never committing more than two

or three hundred at any one time.

Marshall, for his part, fought a

completely passive battle, content, by and

large, merely to maintain his original

position.66 At various times during the

afternoon a well directed charge could

have sent Garfield's disorganized

men reeling down the valley, but

Marshall did not really want a victory.

He was satisfied to continue his retreat

in peace.

By the bloody standard of later battles

Middle Creek was a tame affair,

but to the participants, few of whom had

seen combat before, it was a dan-

gerous and exciting afternoon. From his

vantage spot on Grave Yard Point,

overlooking the smoke-filled valley,

Garfield had no doubt but that he was

witnessing "one of the most

terrific fights which has been recorded in the

war."67 By late afternoon Garfield

feared that the battle was approaching its

climax. He vividly reconstructed the

situation later to his wife: "My re-

serve was now reduced to a mere

handfull, and the agony of the moment was

terrible. The whole hill was enclosed in

such a volume of smoke as rolls from

the mouth of a volcano. Thousands of gun

flashes leaped like lightning from

the clouds. Every minute the fight grew

hotter. In my agony of anxiety I

prayed to God for the reinforcement to

appear." He was just on the point

of leading his men in person on a final

desperate charge when he looked

behind him "and saw the Hiram

banner sweep round the hill."68

It was Colonel Sheldon, at the head of

seven hundred reinforcements from

Paintsville. Since receiving Garfield's

message earlier that morning they

had been marching at a frenzied pace,

their urgency stimulated by the distant

THE HERO OF THE SANDY VALLEY 21

sound of gunfire. When they finally hove

into sight, they were greeted by a

wild cheer from their embattled

comrades, who took new heart at their

appearance and charged once more up the

hill, forcing the rebels back to

the rocky summit. Night was falling when

Sheldon's reinforcements began

to pick their way across the muddy

valley. By the time they reached the

foot of the hill it was too dark to fight.

Fearing that his men might fire on

one another in the dark, Garfield

recalled his troops, leaving Marshall still

ensconced upon his ridge.69 On this

inconclusive note the battle of Middle

Creek came to an end. "We had many

hard fights for two years after," a

veteran later told his grandchildren,

"but Middle Creek was cold and cheer-

less, and a sharp fight."70

That night Garfield's men slept on their

arms on Grave Yard Point, con-

fident that the fighting would be

renewed in the morning. In the middle of

the night they were startled to see a

brilliant light flash from across the

valley. It was Marshall burning his

stores to lighten the load of his soldiers,

who were then stealthily evacuating the

scene of the battle. In the morning

Garfield's cavalry,

"ingloriously" absent during the fighting, finally ar-

rived.71 Garfield sent them

after the retreating enemy, but after a desultory

pursuit they drifted back to camp

empty-handed.72 Supplies were too low for

the brigade to follow Marshall in force,

nor could they remain on Grave

Yard Point forever, so Garfield ordered

his troops to fall back to replenish

their stores and lick their wounds.

These wounds were remarkably light,

considering how sharp the fighting

had been. Only twenty-one men had been

wounded, three of them mortally.73

The rebel dead, scattered over the

field, were buried by Garfield's men

where they fell. From the excited,

boastful reports of his soldiers Garfield

estimated that the Confederates had

suffered 125 killed and at least that

many wounded. He even implied that he

had seen twenty-seven, or sixty, or

eighty-five of these dead himself.74

Marshall, who was certainly in a better

position to know, calculated his losses

at no more than eleven killed and

fifteen wounded. When he came to

estimate Garfield's casualties, however,

Marshall too displayed considerable

imaginative flair, claiming to have

killed 250 and wounded 300 more.

"We saw his dead borne in numbers from

the field," he said.75

It was not bluster alone which led

Garfield to exaggerate the carnage

at Middle Creek. This was his first

battle, his first sight of corpses, and it

left him shaken. "It was a terrible

sight," he told his family, "to walk over

the battle field and see the horrible

faces of the dead rebels stretched on

the hill in all shapes and

positions."76 Years later, talking to his Ashtabula

22 OHIO HISTORY

neighbor William Dean Howells, he

declared that "at the sight of these

dead men whom other men had killed,

something went out of him, the habit

of his lifetime, that never came back

again: the sense of the sacredness of

life, and the impossibility of

destroying it."77

Another soldier, Captain Oliver Wendell

Holmes, after long reflection,

later concluded that "the

generation that carried on the war has been set

aside by its experience . . . [for] in

our youth our hearts were touched

with fire. It was given to us to learn

at the outset that life is a profound and

passionate thing."78 Holmes thought

that the sufferings of war had made

its participants better men; but

suffering need not always be ennobling: it

can teach the cheapness of human life as

well as its importance. Garfield

was neither brutalized nor ennobled by

his wartime acquaintance with vio-

lence and death, but he was changed.

Along with his entire generation,

Garfield had lost his innocence. His

world--the sheltered, benevolent, provi-

dential world of pre-war America--was

shattered, and try as he might, it

could never be reassembled.

After tidying up the battlefield the

Eighteenth Brigade withdrew to Pres-

tonburg. Finding that that

"mud-cursed village" had been picked bare

by Marshall, Garfield had to fall back

all the way to Paintsville.79

Marshall interpreted (or professed to

interpret) Garfield's return to Paints-

ville as an admission that the federals

had been "signally and unmistakably

whipped."80 Garfield's

"footsore" but proud soldiers, however, never

doubted that the victory had been

theirs. "Soldiers of the Eighteenth

Brigade!" their colonel

grandiloquently proclaimed,

I am proud of you. You have marched in

the face of a foe of double your

numbers. . . . With no experience but

the consciousness of your own man-

hood, you have driven him from his

stronghold, leaving scores of his bloody

dead unburied. I greet you as brave men.

Our common country will not

forget you. I have recalled you from the

pursuit that you may regain vigor

for still greater exertions. . . .

Officers and soldiers, your duty has been

nobly done.81

Back in Ohio these sentiments were

heartily applauded. Morale was low

on the home front. "You scarce meet

a man that dont look and talk

gloomily," Garfield's friend J. H.

Rhodes observed.82 To victory-starved

northerners the news from Middle Creek

was a welcome relief from the

constant humiliation of defeat and

inactivity. Fathers and friends of the

boys of the Forty-Second Ohio took

Garfield to their hearts. "The feeling

of the public for you has deepened

remarkably," Rhodes reported. "I can

THE HERO OF THE SANDY VALLEY 23

not begin to tell you how strongly you

are fixed in their affections. . . . I

have heard the most extravagant

expectations of your future." Even Gov-

ernor David Tod let it be known that he

had forgiven Garfield for opposing

his nomination, and was ready to help

further his career.83 From General

Buell came an official commendation for

his "perseverance, fortitude, and

gallantry,"84 and a

movement was afoot, inspired by the Ohio Senate, to

promote Garfield to general.85

To satisfy a public avid for details of

its new hero, the press invented

graphic accounts of Garfield shucking

off his coat in the heat of battle and

charging in his shirt sleeves while shouting,

"Go in boys! Give 'em hell!"86

Newspapers all over the North hailed

"the bold lion in the path of Humphrey

Marshall" for having led "the

quickest and most thorough move since the

breaking out of the Great

Rebellion." Colonel Garfield, "the Kentucky

hero, who so signally routed the

Falstaffian Humphrey Marshall," was a

ten-day wonder until news of Thomas'

more spectacular victory over Zolli-

coffer at Mill Springs gave the public a

new hero to admire.87

On the Confederate side of the lines the

"Falstaffian" General Marshall

vigorously insisted that he, not

Garfield, was the true victor of Middle

Creek. "Let a few facts decide that

question," he argued. "He came to

attack and did attack, and he was in

force far superior to mine. He did

not move me from a single position I

chose to occupy. At the close of the

day each man of mine was just where he

had been posted in the morning."

If Garfield had won, he asked, why did

he not pursue? Instead, he had

fallen back to his base at Paintsville,

"whence he came in mass to drive

me out of the State. He returned without

accomplishing his mission."88

There was some force to these arguments.

Neither side, in truth, had

come out of Middle Creek with much

glory. But no amount of explanation

could disguise the fact that Garfield

was now well established in Kentucky

while Marshall was leaving the state.

Garfield may or may not have won

the battle; he certainly won the campaign.

Marshall insisted that hunger,

"an enemy greater than the

Lincolnites,"89 was the only reason for his with-

drawal, but he missed the point.

Supplies were as important to military

success as victory in battle. Garfield

handled his supply problem with

imagination and skill, Marshall trusted

to luck. A truly enterprising com-

mander would have solved his supply

shortage (as some Confederate gen-

erals were to do) by attacking the

federals and seizing their stores.

Instead Marshall was content to

manufacture excuses,90 and slink away.

His only problem now was in which

direction to retreat. His proper course

should have been to head towards central

Kentucky and join with the other

24 OHIO HISTORY

Confederate column. By drawing Garfield

away from his river supply line,

Marshall could neutralize his opponent's

main advantage. Originally this

had been Marshall's intention, and he

had grandly sworn to die in the

attempt if necessary. By mid-January,

however, the situation in Kentucky

had changed. With the defeat and death

of Zollicoffer at Mill Springs, the

Confederate invasion of Kentucky had collapsed,

leaving Marshall with

no place to go but Lack to Virginia.

Besides, he was now thoroughly sick

of Kentucky. Disease, hunger, and

desertions had inspired him with "a per-

sonal hatred for the country," and

he longed to return once more "to the

haunts of cultivated men."91 Later

that month, when he was ordered to

fall back to Virginia through Pound Gap,

he hastened to comply.92 Except

for a small garrison left to guard the

gap, eastern Kentucky was now free

of Confederates.

[To be concluded in the next issue]

THE AUTHOR: Allan Peskin, who teaches

history at Fenn College, is writing a

biography

of President Garfield.

NOTES

THE HERO OF THE

SANDY VALLEY

1 John G. Nicolay and John Hay, eds., Complete Works of Abraham Lincoln

(Cumberland Gap,

Tenn., 1894), VI, 360.

2 For a discussion of Kentucky's

"neutrality," see E. Merton Coulter, The Civil War and

Readjustment in Kentucky (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1926).

3 See the sketch of Buell in Whitelaw

Reid's Ohio in the War: Her Statesmen, Generals and

Soldiers (Columbus, 1893), I, 695-724.

4 The War of the Rebellion: A

Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Con-

federate Armies (Washington, 1880-1901), Series I, Vol. IV, 225-230.

Cited hereafter as Official

Records. As all references are to Series I, the series number is

omitted from subsequent citations.

5 Otto F. Bond, ed., Under the Flag

of the Nation: Diaries and Letters of a Yankee Volunteer

in the Civil War (Columbus, 1961), 12-13; F. H. Mason, The

Forty-Second Ohio Infantry

(Cleveland, 1876), 46-47.

6 Garfield to J. H. Rhodes, December 17,

1861. J. H. Rhodes was a close friend and colleague

of Garfield's at Hiram. This letter is

part of a collection of Garfield material, mainly of a per-

sonal nature, which has been loaned by

the Garfield family to Professors Harry Brown and

Frederick DeForest Williams of Michigan

State University, who kindly allowed me to examine it.

All Garfield letters cited are in this

collection unless otherwise noted.

7 Garfield to his wife, December 16,

1861.

8 James A. Garfield, "My Campaign

in East Kentucky," North American Review, CXLIII

(1866), 527. This account must be used

with care, since it is apparently a hastily dictated memoir

prepared for purposes of campaign

publicity. The dates are incorrect, as are many of the

details.

9 Garfield to his wife, December 16,

1861.

10 Garfield, "My Campaign in East

Kentucky," 527-528.

11 Official Records, VII,

503-504; Garfield to his wife, December 16, 1861.

12 Official Records, VII, 22-23.

13 For example, see Official Records,

VII, 25, 26, 27.

14 Garfield to his wife, December 20,

1861.

15 Garfield to J. H. Rhodes, December

17, 1861.

16 Garfield to his wife, December 20,

1861; Garfield, "My Campaign in East Kentucky," 528.

17 Garfield, "My Campaign in East

Kentucky," 528.

18 Bond, Under the Flag of the

Nation, 13-14.

19 Mason, The Forty-Second Ohio, 53-55.

20 Bond, Under the Flag of the

Nation, 14-15; Mason, The Forty-Second Ohio, 54-55, 57. The

two accounts differ on details of this

incident.

21 Mason, The Forty-Second Ohio, 55;

Garfield, "My Campaign in East Kentucky," 529.

22 Garfield to his mother, January 26,

1861.

23 Humphrey Marshall to Alexander

Stephens, December 13, 1861. All Marshall letters cited

here are at the Filson Club, Louisville,

Kentucky. I am indebted to Mr. Jon Kaliebe, who

kindly allowed me to examine an

unpublished paper entitled "The Big Sandy Campaign," from

which this and the subsequent references

to Marshall letters have been taken.

24 Robert Underwood Johnson and Clarence

Clough Buel, eds., Battles and Leaders of the

Civil War (New York, 1887-88), I, 397.

25 See Official Records, IV, 495.

26 Ibid., VII, 43.

27 Kaliebe, "The Big Sandy

Campaign."

28 Johnson and Buel, Battles and

Leaders, I, 394.

29 Clement Eaton, A History of the

Southern Confederacy (New York, 1961), 95.

30 Official Records, VII, 43, 45.

31 Johnson and Buel, Battles and Leaders, I, 395-397.

32 Humphrey Marshall to Alexander

Stephens, December 23, 1861.

33 Official Records, VII, 43.

34 In his attempts to raise troops,

Marshall was usually disappointed. As he later disgustedly

observed, "It was wonderful to see

how ignorant, how apathetic, how utterly unconscious of the

despotism which guarded their moral

nature those people were. . . . Sometimes they would

84

OHIO HISTORY

join a company and desert before they

had marched twenty miles." Official Records, LII, Pt. 2,

p. 284.

35 Johnson and Buel, Battles and

Leaders, I, 394.

36 Official Records, VII, 46.

37 Ibid., 25-26.

38 Ibid., 32: see also p. 27; Garfield, "My Campaign in East

Kentucky," 529.

39 Carfield to his wife, January 1,

1862.

40 Official Records, VII, 25-26.

41 Garfield to his wife, January 13,

1862.

42 Garfield to his wife, January 1,

1862.

43 Official Records, VII, 26.

44 Reid, Ohio in the War, I,

747n.

45: Official Records, VII, 26-28; Mason, The Forty-Second Ohio, 59-60; (Carfield, 'My

Cam-

paign in East Kentucky," 530-531;

Garfield to his wife, January 18, 1862.

46 Garfield, "My Campaign in East

Kentucky," 530-531.

47 Garfield to his wife, January 13,

1862.

48 Ibid.

49 Bond,

Under the Flag of the Nation, 17.

50 Mason, The Forty-Second Ohio, 65.

51 Official Records, VII, 28: Garfield to his wife, January 13, 1862.

52 Bond, Under the Flag of the Nation, 17-18.

53 Garfield to his wife, January 13, 1862.

54 Ibid.

55 Official Records, VII, 28-30.

56 Garfield to his wife, January 26, 1862.

57 Ibid.

58 Ibid.; Mason,

The Forty-Second Ohio, 67.

59 Official Records, VII, 52.

60 Garfield to his wife, January 13,

1862; Mason, The Forty-Second Ohio, 67.

61 Official Records, VII, 30.

62 Garfield to his wife, January 13,

1862.

63 See Official Records, VII, 56.

64 Garfield to his wife, January 13,

1862: Mason, The Forty-Second Ohio, 69. In Confederate

accounts of the battle this ruse becomes

transformed into a full-scale cavalry charge. See

Official Records, VII, 46-48; Johnson and Buel, Battles and Leaders, I,

396.

65 Frederick A. Henry, Captain Henry

of Geauga: A Family Chronicle (Cleveland, 1942), 113-

114.

66 Official Records, V1I, 56.

67 Garfield to his wife, January 13, 1862.

68 Ibid.

69 Mason, The Forty-Second Ohio, 72-73;

Henry, Captain Henry of Geauga, 113; Garfield to

his wife, January 13, 1862.

70 Henry, Captain Henry of Geauga, 114.

71 Garfield to his wife, January 13,

1862.

72 Official Records, VII, 31.

73 Ibid.

74 Garfield to his wife, January 13,

1862; Official Records, VII, 29, 31; Henry, Captain Henry

of Geauga, 113; Bond, Under the Flag of the Nation, 19.

75 Official Records, VII, 48.

76 Garfield to his mother, January 26,

1862.

77 William Dean Howells, Years of My

Youth (New York, 1916), 205-206.

78 Max Lerner, ed., The Mind and

Faith of Justice Holmes: His Speeches, Essays, Letters and

Judicial Opinions (Boston, 1943), 16.

79 Official Records, VII, 31;

Bond, Under the Flag of the Nation, 19.

80 Official Records, VII, 56.

81 Quoted in Theodore Clarke Smith, The

Life and Letters of James Abram Garfield (New

Haven, Conn., 1925), I, 193.

82 J. H. Rhodes to Garfield, February 6,

1862. James A. Garfield Papers, Library of Congress.

83 J. H. Rhodes to Garfield, January 6,

[1862]. Garfield Papers, Library of Congress. This

letter is incorrectly dated by the

Library of Congress as 1861.

NOTES

85

84 Official Records, VII, 23.

85 See petition of Ohio Senate to

President Lincoln [copy], February 3, 1862, in Garfield

Papers, Library of Congress.

86 Cleveland Herald, January 16,

1862.

87 Newspaper comments collected by J. H.

Rhodes from the New York Post and other papers

and quoted in a letter to Garfield,

January 20, 1862. Garfield Papers, Library of Congress.

88 Official Records, VII, 56. See

also ibid., 46-48, 55-57; Johnson and Buel, Battles and

Leaders, I, 396.

89 Official Records, VII, 48.

90 Ibid., 48-50.

91 Humphrey Marshall to Alexander

Stephens, February 22, 1862.

92 Official Records, VII, 57-58.

WILLIAM SANDERS

SCARBOROUGH

* This is the second and final part of

an article on William Sanders Scarborough, the first

part of which appeared in the October

1962 issue (v. 71, pp. 203-226).

1 Transactions of the American

Philological Association, 1882, XIII

(Cambridge, Mass., 1882),

iv. The Transactions of the American

Philological Association will be referred to hereafter as

Transactions only.

2 Ibid., 1884. XV (Cambridge, Mass., 1885), vi.

3 At this commencement Jebb had received

an honorary LL.D. Dictionary of National Biography,

1901-1911 (Oxford, 1912), 367-369.

4 Transactions, 1885, XVI (Cambridge, Mass., 1886), xxxvi.

Ibid., 1886, XVII (Boston, 1887), ii; ibid., 1887, XVIII

(Boston, 1888), ii.

6 Education, IX (1888-89),

263-269.

7 Ibid., 396-399.

8 Ibid., X (1889-90), 28-33.

9 Transactions, 1888, XIX (Boston, 1889), xxxvi-xxxviii; ibid., 1889, XX

(Boston, 1889), v-vi.

10 Ibid., 1890, XXI (Boston, n.d.), xlii-xliv. Later, he read a paper

with the same title before

the National Educational Association.

11 Ibid., 1891, XXII (Boston, n.d.), 1-lii.

12 Education, XII (1891-92), 286-293. The paper was based largely on

Grote's History, VII,

154.

13 Education, XIV (1893-94), 213-218. It was also summarized in Transactions,

1892, XXIII

(Boston, n.d.), vi-viii.

14 "Hunc Inventum Inveni," Transactions,

1893, XXIV (Boston, n.d.), xvi-xix.

15 Ibid., 1894, XXV (Boston,

n.d.), xxiii-xxv.

16 Ibid., 1895, XXVI (Boston,

n.d.), xi.

17 Ibid., 1896, XXVII (Boston,

n.d.), xlvi-xlviii.

18 Ibid., 1898, XXIX (Boston, n.d.), lviii-lx.

19 Education, XIX (1898-99), 213-221, 285-293.

20 Transactions, 1902, XXXIII

(Boston, n.d.), xx.

21 Ibid., 1903, XXXIV (Boston,

n.d.), xli.

22 Ibid., 1906, XXXVII (Boston,

n.d.), ii, xxx-xxxi.

23 Ibid., 1907, XXXVIII (Boston,

n.d.), ii, xxii-xxiii.

24 Ibid., 1908, XXXIX (Boston, n.d.), v.

25 Ibid., 1911, XLII (Boston,

n.d.), ii.

26 Ibid., 1912, XLIII (Boston, n.d.), ix-xvii.

27 Ibid., 1913, XLIV (Boston,

n.d.), iii.

28 Ibid., 1916, XLVII

(Boston, n.d.), ii.

29 Arnett was born at Brownsville,

Pennsylvania, March 16, 1838, and died at Wilberforce,

Ohio, October 7, 1906. For a listing of

a collection of his papers, see The Benjamin William

Arnett Papers at Carnegie Library,

Wilberforce University, Wilberforce, Ohio, compiled by

Casper L. Jordan (Wilberforce, Ohio,

1958).

30 Leonard E. Erickson, "The Color

Line in Ohio Public Schools, 1829-1890" (unpublished

Ph.D. dissertation, Ohio State

University, 1959), 333-339.

31 Champion City Times (Springfield,

Ohio), March 1, 1887.

32 The Centennial Jubilee of Freedom

at Columbus, Ohio (Xenia, Ohio, 1888), 67.