Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

An Outing on the Congo. 349

AN OUTING ON THE CONGO.

A VISIT TO THE SITE OF DUNMORE'S TREATY

WITH THE

SHAWNEES 1774.

BY WILLIAM H. SAFFORD.

Many of your readers are, doubtless,

familiar with Stanley's

expeditions in Africa, tracing the

wendings of that hitherto

unknown river of her western deserts,

called the Congo. His first

exploration was in search of Livingston,

and the second of his

voyages was for the purpose of locating

that eminent and eccen-

tric traveler, Emin Pasha, and thus to

Stanley, as well as the

civilized world, the expeditions were a

revelation of a new ter-

restrial existence --rich in its

treasures of silver and gold -

its ivory and precious gems - its

fertility of soil, and its won-

derful variety of animal and vegetable

life. It has already ex-

cited the cupidity of modern Europe, and

eager nations are now

earnestly struggling for its dominion.

But it is not of this Congo we write.

There is another stream

of much less pretentiousness in the

volume of its waters, but far

more classic in its associations, and

richer, by far, in thrilling his-

torical incident. This Congo we now

sketch, does not aspire to

the dignity of a river, nor even a

creek; it is what would be called

in New England a brook, and in

the South a run. It does not

rush from precipitous heights dashing

its waves against rocks

and cliffs, but gently meanders along

low lying meadows, through

quiet landscapes, lazily floating onward

to the Scioto, and thence

to the ocean.

Few, indeed, of this generation have

known, or even heard

of this classic water; and yet, it is

but an hour's ride from the

historic city of Ohio - its "Ancient Metropolis,"

Chillicothe.

We pass over smoothly gravelled roads,

along cultivated fields

and ornamental gardens, by spacious

mansions of classic architec-

tural taste, until nearly approaching

the Pickaway Plains. The

350 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

stream stretches along the southern side

of this plateau, in what

might be termed the uplands, and is fed

by the numerous springs

along its course and the surface

drainage of the lands through

which it flows.

On a beautiful day in the month of May,

1894, the writer,

with a professional photographer, made

an outing to this historic

stream, the object being to secure

photographic views of some

of the more noted localities, rendered

famous from the events

which there transpired in the early

history of the country. Chief

among these is the famed Logan Elm, under

which, it is said,

Lord Dunmore, Governor of Virginia,

concluded a treaty of peace

with the confederated tribes of the

Shawnees, and other Indians,

on which occasion the classic speech of

the Mingo chief, Logan,

is said to have been delivered. This was

in the autumn of the

year 1774, immediately after the

battle of Point Pleasant, Vir-

ginia, at the mouth of the Great

Kanawha. It was, perhaps, the

longest continued and most hotly

contested conflict in the annals

of Indian warfare. The fatalities were

appalling on both sides.

More than one thousand of the allied

savages, under command

of the noted warrior, Cornstalk, were

opposed to about an equal

number of Virginians under General

Andrew Lewis. The battle

commenced at sunrise on the morning of

the tenth of October,

1774, and lasted till darkness closed

the scene. The losses by

the Virginians were two colonels, five

captains, three lieutenants,

and many subalterns, beside seventy-five

privates; while that of

the Indians was computed at two hundred

and thirty-three. Under

cover of darkness Cornstalk withdrew his

forces, recrossed the

Ohio in haste, and retreated to his

towns in the Pickaway Plains.

The engagement of the forces of General

Lewis was a sur-

prise - he was not anticipating an

attack, and had made no

preparations for defence. He was looking

to the Pickaway towns

as the scene of the intended conflict,

and rested in ignorant

security that his foe was alike

unsuspecting. But in this, as it

proved, he was fatally mistaken. The

vigilance of his scouts

had long since advised Cornstalk of

Lewis's advance and gave

him timely warning of the approach of

his enemies. He hurriedly

collected his forces and resolved to

meet the Virginians on their

|

|

|

THE LAST COLONIAL GOVERNOR OF VIRGINIA. From a very tine portrait in the State Library Gallery at Richmond, Va. [ From the address of Judge J. H. Anderson, of Columbus, before five or six thousand people on the banks of the Tymochtee, near Crawford's monument, in Crawford town- ship, Wyandot county, Ohio. Published by The Ohio Historical Society, by permission of the author.] (351) |

352 Ohio

Arch. and His. Society Publications.

own soil. When Lewis had arrived at the

appointed rendezvous

with Dunmore, Cornstalk was already

there to meet him.

"Calm as the breeze, but terrible

as the storm." The plan

of the campaign, previously agreed upon

between General Lewis

and Lord Dunmore, was, that Lewis was to

descend the Kanawha

to its junction with the Ohio, and if

not already there, then await

the arrival of Dunmore. The Earl was to

march his forces of one

thousand men up the Potomac to

Cumberland, cross the Alle-

ghenies, until he struck the

Monongahela, thence, following that

stream downward, reach Fort Pitt, and

thence descend the Ohio

to Point Pleasant and form a junction

with Lewis. This was

the original plan of operation.

On the first of October, 1774, Lewis

reached the mouth of

the Kanawha, but Dunmore had not

arrived. He dispatched two

messengers to Dunmore to enquire the

cause of his delay, and

awaited a reply. On the ninth of

October, three messengers from

the Earl arrived at Lewis's camp and

informed him that the Gov-

ernor had changed his plans, that he

would not meet Lewis at

the Point, but would descend the Ohio to

the mouth of the

Hockhocking river, ascend that stream to

the Falls, and thence

strike off to the Pickaway towns along

the Scioto, whither he

ordered Lewis to repair and meet him as

soon as possible, there

to end the campaign.

This information as to the change of the

plan reached Lewis

on the ninth of the month. It is evident

that Cornstalk had

received like intelligence of such

change, for, on the morning

of the tenth, he struck his unsuspecting

foe with a staggering

blow hitherto unprecedented in savage

warfare.

"For several days after the battle

Lewis was busy burying

the dead, caring for the wounded,

collecting the scattered cattle,

and building a storehouse and a small

stockade fort. Early on

the morning of the thirteenth of October

messengers who had

been sent on to Dunmore advising him of

the battle returned with

orders to Lewis to march at once with

all of his available forces

against the Shawnee towns, and when

within twenty-five miles

of Chillicothe to write to his lordship.

The next day the last rear

guard, with the remaining beeves,

arrived from the mouth of the

Elk, and while work on the defences at

the Point was hurried,

An Outing on the Congo. 353

preparations were made for the march. By

evening of the seven-

teenth Lewis, with fifteen hundred men

in good condition, had

crossed the Ohio and gone into camp on

the north side. Each

man had ten days' supply of flour, a

half pound of powder, and

a pound and a half of bullets; while to

each company was assigned

a pack-horse for the tents. Point

Pleasant was left in command

of Colonel Fleming, who had been

severely wounded in the battle,

and with whom three other officers and

one hundred and fifty

disabled men remained. On the eighteenth

Lewis, with Captain

Arbuckle as guide, advanced towards the

Shawnee towns, eighty

miles distant in a straight line, and

probably one hundred and

fifty miles by the circuitous Indian

trails. The army marched about

eleven miles a day, frequently seeing

hostile parties, but engaging

none. Reaching the salt licks near the

head of the south branch

of Salt Creek in what is now Jackson

County, they descended

that valley to the Scioto, and thence to

a prairie on Kinnikinnick

Creek, where was the freshly deserted

village of one of the tribes.

This was thirteen miles south of

Chillicothe (now Westfall). Here

they were met, early on the

twenty-fourth, by a messenger from

Dunmore, ordering them to halt, as a

treaty was nearly concluded

at Camp Charlotte. But Lewis's army had

been fired on that

morning and the place was untenable for

a camp in a hostile

country, so he concluded to seek a more

desirable situation. A

few hours later another messenger came,

again promptly ordering

a halt, as the Shawnees had practically

come to terms. Lewis

now determined to join the northern

division in force at Camp

Charlotte, not liking to have the two

armies separated in the

face of a treacherous enemy; but his

guide mistook the trail

and took one leading directly to the

Grandier Squaw's Town.

Lewis encamped that night on the west

side of Congo Creek,

two miles above its mouth, and five and

a quarter miles from old

Chillicothe, with the Indian town half

way between. The Shaw-

nees were now greatly alarmed and

angered, and Dunmore him-

self, accompanied by the Delaware chief,

White Eyes, a trader,

John Gibson, and fifty volunteers, rode

over in hot haste that

evening to stop Lewis and reprimand him.

His lordship was

mollified by Lewis's explanations, but

the latter's men, and indeed

Dunmore's, were furious over being

stopped when within sight

354

Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

of their hated quarry; and tradition has

it that it was necessary

to treble the guards during the night to

prevent Dunmore and

White Eyes from being killed. The

following morning (the

twenty-fifth) his lordship met and

courteously thanked Lewis's

men for their valiant service; but said,

that now the Shawnees

had acceded to his wishes, the further

presence of the southern

division might engender bad blood. Thus

dismissed, Lewis led

his army back to Point Pleasant."*

On his arrival at the Indian villages,

as security against an

attack of the enemy, Dunmore caused a

square of about two

acres, near Sippo, and in close

proximity to Congo, to be enclosed

with a palisade, in the center of which

was erected a block-house

to be used for headquarters. The whole

formed a temporary

barrier against any hostile force which

might oppose him. This

he named Camp Charlotte, in honor of the

young reigning Queen

of England, whose husband's commission,

as Governor of Vir-

ginia, he bore. About two and a half

miles west of Camp Char-

lotte Lewis encamped his forces, which

locality has since been

known as Camp Lewis. The latter

encampment was on the

lands since entered and settled by Major

John Boggs in 1798,

embracing or near the famous Logan

Elm on the banks of the

Congo. It has since passed out of the

possession of Major Boggs'

descendants, and is now owned by Mrs.

Mary A. Wallace, widow

of the late Samuel S. Wallace, an

attorney of Chillicothe.

The former is situated on the lands

originally entered and

settled upon by the late George Wolfe,

and is yet in the possession

of his grandson, Benjamin F. Wolfe.

These encampments have

been often confounded with each other.

History is rich in incidents which

occurred on the banks

of the Sippo and the Congo. They are

both small streams sit-

uate but a short distance apart, the

former entering the latter

about two miles from its confluence with

the Scioto.

The troops of Dunmore and Lewis united

numbered two

thousand five hundred officers and men.

Their formidable pres-

ence, planted at the very gates of their

hunting grounds, and

at the doors of their villages, spread

consternation and alarm

* R. G. Thwaite's Note in Border Warfare 176-7.

|

|

|

(355) |

356 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

among these savage inhabitants. Their

voices were now for

peace - peace on almost any terms.

Cornstalk was a noble war-

rior - full of courage, and at the same

time full of soul. At

the battle of Point Pleasant he

commanded his Indian forces

with consummate skill, and at any time

his warriors were be-

lieved to waver his voice could be heard

above the din of battle

exclaiming in his native tongue:

"Be brave! Be brave!" - "Be

strong! Be strong!" When he

returned to the Pickaway towns

he called a council of the nation to

consult as to what should

now be done and upbraided them for not

permitting him to

make peace, as he had desired on the

night of the battle. "What,"

said he, "will you do now? The big

knife is coming on us, and

we shall all be killed. Now you must

fight, or we are done."

But no one answering, he said:

"Then let us kill all our women

and children and go and fight until we

die." No answer still hav-

ing been made, he indignantly arose,

struck his tomahawk in a

post of the council house and exclaimed:

"I'll go and make

peace," to which all warriors

grunted "Ough!" "'Ough!" and

runners were instantly dispatched to

Dunmore to solicit peace.

Dunmore was met, even before he reached

the Indian vil-

lages, by a messenger (a white man) from

Cornstalk, anxious for

an accommodation. The messenger was

returned, accompanied

by John Gibson and Simon Girty - the

latter was then a scout

for Dunmore and had not then commenced

his notorious ren-

egade career. The two soon brought back

an answer from the

Shawnees expressing a desire for peace.

A council of the prin-

cipal chiefs were then assembled under

the wide-spreading

branches of the famed Elm Tree.

Messengers were dispatched

for the famous Mingo chief Logan, whose

residence, we have

mentioned, was at Old Chillicothe, about

two miles distant on

the west side of the Scioto. But Logan,

like Achilles, sulked

in his tent - he refused to attend.

"Two or three days before

the signing of the treaty," says an

eye witness, "when I was on

the out guard, Simon Girty, who was

passing by, stopped me

and conversed; he said he 'was going

after Logan, but he did

not like his business, for he was a

surly fellow.' He, however,

proceeded on, and I saw him return on

the day of the treaty,

and Logan was not with him. At this time

a circle was formed

358

Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

and the treaty begun. I saw John Gibson,

on Girty's arrival,

get up and go out of the circle and talk

with Girty, after which

he, Gibson, went into a tent, and soon

after, returning into the

circle, drew out of his pocket a piece

of clean paper, on which

was written, in his own hand writing, a

speech for, and in the

name of Logan. Girty from recollection

translated the speech

to Gibson, and the latter put it into

excellent English, as he was

abundantly capable of doing."

This speech was first brought into

public notoriety by Pres-

ident Jefferson in his Notes on

Virginia. Its publication, by him,

produced an embittered controversy as to

the genuineness of the

production - principally on the part of

the family and friends of

Major Michael Cresap, whose name had

been assailed, in that

Major Cresap was therein charged with

having, in cold blood,

murdered Logan's family. Mr. Jefferson

having been accused

of the sole authorship of the speech,

was compelled, in vindica-

tion, to furnish a statement of the

facts occasioning its publica-

tion. In this he says:

"The notes on Virginia were written

in the year 1781 and

1788, in answer to certain queries

proposed to me by Mons. De

Marbois, then Secretary of the French

Legation in the United

States; and a manuscript copy was

delivered to him. A few

copies, with some additions, were

afterwards, in 1784, printed

in Paris, and given to particular

friends. In speaking of the

animals of America, the theory of M. de

Buffon, Abbe Raynal,

and others presented itself to

consideration. They have supposed

there is something in the soil, climate

and other circumstances

of America which occasions animal nature

to degenerate, not

excepting even the man, native, or

adoptive, physical or moral.

This theory, so unfounded and degrading

to one-third of the

globe, was called to the bar of fact and

reason. Among other

proofs adduced in contradiction of this

hypothesis, the speech of

Logan, an Indian chief, delivered to

Lord Dunmore in 1774, was

produced as a specimen of the talents of

the aboriginals of this

country, and particularly of their

eloquence; and it was believed

that Europe had never produced anything

superior to this morsel

of eloquence. In order to make it

intelligible to the reader, the

transaction on which it was founded was

stated as it had been

An Outing on the

Congo. 359

generally related in America at the time

and as I had heard it

myself in the circle of Lord Dunmore and

the officers who

accompanied him; and the speech itself

was given as it had,

ten years before the printing of that

book, circulated in the news-

papers through all the then colonies -

through the magazines

of Great Britain, and the periodical

publications of Europe. For

three and twenty years it passed

uncontradicted; nor was it ever

suspected that it even admitted

contradiction. In 1797, however,

for the first time, not only the whole

transaction respecting Logan

was affirmed in public papers to be

false, but the speech itself sug-

gested to be a forgery, and even a

forgery of mine, to aid me

in proving that the man of America was

equal in body and mind

to the man of Europe. But wherefore the

forgery? Whether

Logan's or mine, it still would have

been American. I should,

indeed, consult my own fame, if the

suggestion that this speech

is mine were suffered to be believed. He

would have a just right

to be proud who could, with truth, claim

that composition. But

it is none of mine, and I yield it to

whom it is due.

"On seeing then, that this

transaction was brought into

question, I thought it my duty to make

particular enquiry into

its foundation. It was more my duty, as

it was alleged that, by

ascribing to an individual therein named

a participation in the

murder of Logan's family, I had done an

injury to his character

which it had not deserved."

Mr. Jefferson, after a voluminous

correspondence with, and

numerous affidavits of, officers and men

of Lord Dunmore's

forces, very clearly established the

genuineness of Logan's speech,

but has left in some doubt the question

as to whether Logan's

family were murdered by Major Michael

Cresap or Greathouse,

a subaltern under his command.

Nevertheless, Logan confidently

believed Cresap to have been the author.

Among the numerous

affidavits procured by Mr. Jefferson was

one of Captain John

Gibson himself, who interpreted the

speech; and as his account

of the transaction differs from that of

"An Eye Witness," we

give his version of it. He relates that,

having delivered to

Logan the message of Dunmore at Old

Chillicothe, Logan re-

fused to attend the council. But, at the

chief's request, they went

into an adjoining wood and sat down.

Here, after shedding

360

Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

abundance of tears, the honored chief

told his pathetic story.

Gibson repeated it to the council on the

Congo and it was caused

to be published in the Virginia

Gazette of that year. We tran-

scribe it as it then appeared.

LOGAN'S SPEECH.

"I appeal to any white man to say

if ever he entered Logan's

cabin hungry, and I gave him not meat;

if ever he came cold

or naked, and I gave him not clothing.

"During the course of the last long

and bloody war, Logan

remained in his tent, an advocate for

peace. Nay, such was

my love for the whites, that those of my

country pointed at me

as they passed and said, 'Logan is the

friend of the white man.'

I had even thought to have lived among

you, but for the injuries

of one man. Colonel Cresap, the last

spring, in cold blood and

unprovoked, cut off all the relations of

Logan, not sparing even

my women and children. There runs not a

drop of my blood

in the veins of any human creature. This

called on me for

revenge. I have sought it. I have killed

many. I have fully

glutted my vengeance. For my country I

rejoice at the beams

of peace. Yet, do not harbor the thought

that mine is the joy

of fear. Logan never felt fear. He will

not turn on his heel

to save his life. Who is there to mourn

for Logan? Not one."

"I may challenge," says Mr.

Jefferson, "the whole orations

of Demosthenes and Cicero, and of any

more eminent orator, if

Europe has furnished more eminent, to

produce a single passage

superior to the speech of Logan, a Mingo

chief, to Lord Dunmore.

The famed Logan Elm, given in the

view, is also known as

the Treaty Tree. The speech of

Logan is erroneously supposed

to have been extemporized in person to

the council assembled

beneath its branches. But such was not

the fact. It was com-

municated to Gibson in his Indian

vernacular, and by Gibson

interpreted to Dunmore at the meeting of

the council. The tree

is still standing and in the same

vigorous condition it was when

it sheltered the combined

representatives of the hostile forces.

The storms of an hundred and twenty

years have failed to leave

their impress upon it, and it yet stands

as monarch of the woods

and a lasting memorial of the event

which it commemorates.

|

|

|

(361) |

362 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

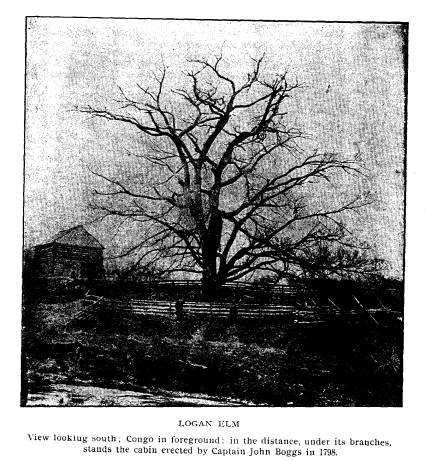

In one of the views presented, Congo's

placid stream is

faintly seen flowing in the foreground,

while at some two hundred

feet from the body of the elm may be

observed the remains of

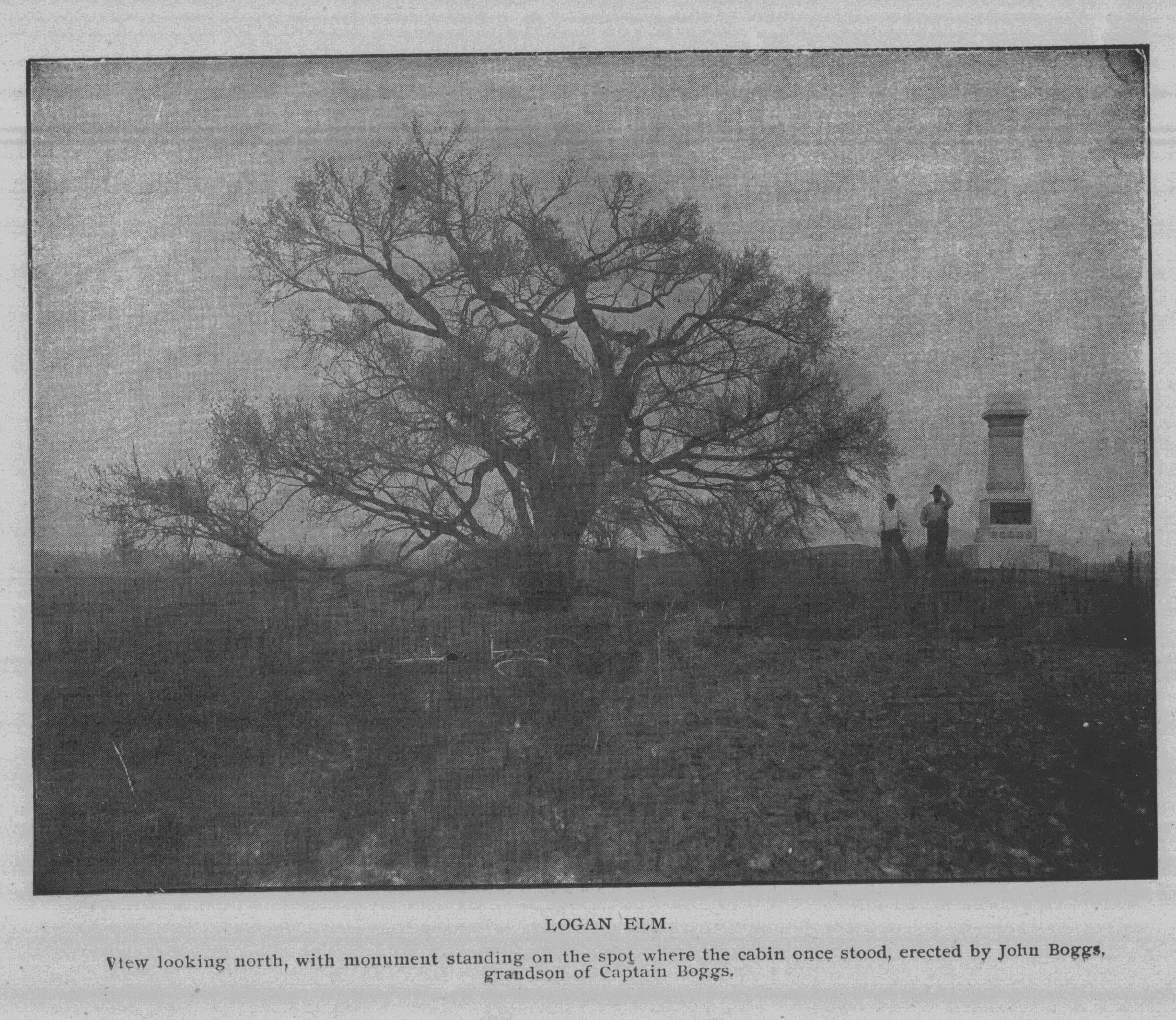

the once famous Boggs Cabin. In the

second view is shown,

from an opposite standpoint, the

imposing Boggs monument,

now occupying the spot where the cabin

once stood. It is an

elegant and costly memorial,

commemorative of the family and

the events which there transpired,

affording a brief but vivid

history of those who were reared under

the wide-spreading

branches, and disported their youthful

exuberance beneath the

famed Elm.

Its dimensions, by actual measurements,

are seventy feet

in hight; the spread of its branches, in

diameter, one hundred

and twenty feet, and the girth of its

body twenty feet.

The monument seen in the rising ground,

measured by esti-

mation only, is, at its base, ten feet

square; hight of base, six

feet; hight of shaft, fifteen feet; and

square of shaft, at base,

five feet, tapering to three at the top.

It bears the following inscriptions and

memorials on its sev-

eral sides as follows:

NORTH SIDE.

Under the spreading branches of a

magnificent elm tree

near by, is where Logan, the Mingo

chief, made his celebrated

speech, and where Lord Dunmore concluded

his treaty with the

Indians, in 1774, and thereby opened

this country for the settle-

ment of our forefathers.

SOUTH SIDE.

Erected by John Boggs to the memory of

his grandfather,

and father- soldier, scout and pioneer.

WEST SIDE.

Major John Boggs, born near Wheeling,

Virginia, 1775.

Moved to Ohio with his father, 1789.

Married Sarah McMechan,

1800. Raised eight children, all born in a cabin that stood

on

this spot. His wife, Sarah, died 1851.

He died 1863.

|

|

|

(363) |

364 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

EAST SIDE.

Captain John Boggs, born in Western

Pennsylvania, 1738.

Married Jane Irwin and raised a large

family on the frontier,

near Wheeling, W. Va.

"One son, William, was taken

prisoner by the Indians in

view of his father's cabin, which is

here represented. Another,

James, was killed by them near

Cambridge, Ohio. Immigrated

to Ohio, and built his cabin on this

spot 1789 and died 1820."

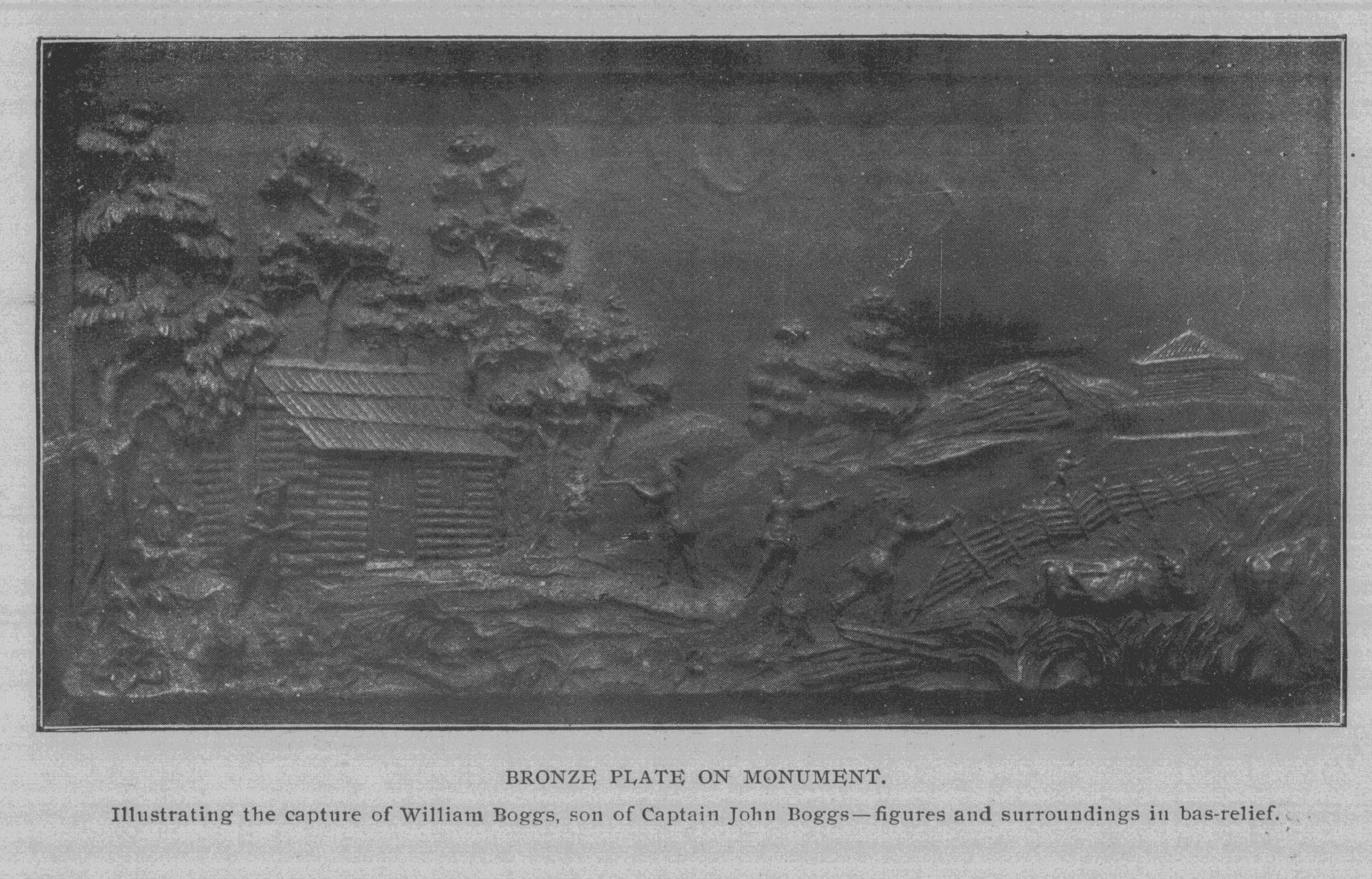

The representation of the capture of

William by the Indians,

mentioned in the inscription, is one of

the most exquisite speci-

mens of mural art anywhere to be found

on any private monu-

ment. It is a bronzed tablet, two feet

six, by fourteen inches, in-

serted in the granite base. The picture

of the capture is executed

in bas relief, and of high relief, the

figures one-half to one inch

high. It represents a beautiful

landscape intended to be, and is,

almost an exact representation of the

cabin and its surroundings.

In the left-hand corner is the log

cabin, at the corner of which

stands the figure of a white man with

his gun at his shoulder

and his eye peering along the barrel.

The wife and children stand

secreted behind the cabin. Obliquely to

the left, and fronting

the door, stands an Indian in anxious

expectancy. At the right

of the man is a waving field of grain

surrounded by a rail fence -

commonly designated a Virginia worm

fence. Several panels

have been thrown down, and a herd of

cattle are feeding on the

growing grain. Near the fence is seen a

boy in flight up a

slight ascent, making his way to a

palisade on the crest of the ridge.

After him is a band of several Indians

in hot pursuit. The whole

scene is a thrilling and vivid

representation of the scene that

on that spot once actually occurred. It

needs no interpreter;

it conveys, at once, to the

understanding what is then and there

being enacted. The stealthy savages,

under cover of darkness,

have laid down the fence and turned the

cattle upon the growing

grain; secreted in ambush they patiently

await approaching day,

anticipating the events to occur in the

morning. The results

showed their strategy complete, their

decoy successful. The boy,

awakening at sunrise, views the

desolating scene, and, unsuspect-

ing the authors of the mischief,

impulsively rushes after the de-

An Outing on the Congo. 365

stroying herd. Suddenly his course is

interrupted by the terrible

apparition of a hostile foe that rises

before him. He turns and

retreats towards the cabin, but there

too appears another of the

band to intercept his entrance. No hope

of escape now presents

itself save that of reaching the

palisade on the ridge in the dis-

tance.

He turns and with accelerated speed vainly endeavors

to reach the goal. His course is beset

with increasing pursuers

on all sides, and at length, exhausted

by the effort, he is over-

taken and made captive to Indian

strategy and Indian cunning.

Meanwhile his anxious father stands

sentinel at the cabin's corner,

guarding the family from the intruding

savage in the front, while

the receding form of his son, pursued by

a hostile force, appalls

his agonized soul.

Such is here depicted the memorable

scenes of our fore-

fathers, preserved in imperishable

bronze and granite, where future

generations may pause and read the story

of their sacrifices and

their sufferings while marking out the

path of Empire.

As we stand before this consecrated

record, sublime reveries

and holy reflections crowd upon our mind

and extort the sigh

of sadness which a scene like this

inspires. In the cycles of

the centuries three generations have

played their parts on this

tragic stage of human life. Men and

women, savage and civilized,

have been in succession gathered to the

shades of their fathers.

Our feet, even now, press the sward

above their graves, where

now, in silence, side by side, and

crumbling to decay, lie the

bones of the red warrior, who once

roamed these forests, and

his ancient foe, the white man.

How apt to this place - this hour -

this scene recur the

words of the immortal bard Bryant.

A WALK AT SUNSET.

"Then came the hunter's tribes, and

thou didst look,

For ages, on their deeds in the hard

chase,

And well fought wars; green sod and

silver brook

Took the first stain of blood: before

thy face

The warrior generations came and passed,

And glory was laid up for many an age to

last.

366 Ohio

Arch. and His. Society Publications.

"Now they are gone, gone as thy

setting blaze

Goes down the west, while night is

pressing on

And with them, the old tale of better

days,

And trophies of remembered power, are

gone.

Yon field that gives the harvest, where

the plough

Strikes the white bone, is all that

tells their story now.

"I stand upon their ashes, in thy

beam,

The offspring of another race, I stand

Beside a stream they loved, this valley

stream;

And where the night-fire of the quivered

band

Showed the gray elm by fits and war-song

sung

I teach the quiet shades the strains of

this new tongue.

"Farewell! but thou shalt come

again-thy light

Must shine on other changes, and behold

The place of the thronged city, still as

night-

States fallen-new empires built upon the

old-

But never shalt thou see these realms

again

Darkened by boundless groves, and roamed

by savage men.'

An Outing on the Congo. 349

AN OUTING ON THE CONGO.

A VISIT TO THE SITE OF DUNMORE'S TREATY

WITH THE

SHAWNEES 1774.

BY WILLIAM H. SAFFORD.

Many of your readers are, doubtless,

familiar with Stanley's

expeditions in Africa, tracing the

wendings of that hitherto

unknown river of her western deserts,

called the Congo. His first

exploration was in search of Livingston,

and the second of his

voyages was for the purpose of locating

that eminent and eccen-

tric traveler, Emin Pasha, and thus to

Stanley, as well as the

civilized world, the expeditions were a

revelation of a new ter-

restrial existence --rich in its

treasures of silver and gold -

its ivory and precious gems - its

fertility of soil, and its won-

derful variety of animal and vegetable

life. It has already ex-

cited the cupidity of modern Europe, and

eager nations are now

earnestly struggling for its dominion.

But it is not of this Congo we write.

There is another stream

of much less pretentiousness in the

volume of its waters, but far

more classic in its associations, and

richer, by far, in thrilling his-

torical incident. This Congo we now

sketch, does not aspire to

the dignity of a river, nor even a

creek; it is what would be called

in New England a brook, and in

the South a run. It does not

rush from precipitous heights dashing

its waves against rocks

and cliffs, but gently meanders along

low lying meadows, through

quiet landscapes, lazily floating onward

to the Scioto, and thence

to the ocean.

Few, indeed, of this generation have

known, or even heard

of this classic water; and yet, it is

but an hour's ride from the

historic city of Ohio - its "Ancient Metropolis,"

Chillicothe.

We pass over smoothly gravelled roads,

along cultivated fields

and ornamental gardens, by spacious

mansions of classic architec-

tural taste, until nearly approaching

the Pickaway Plains. The

(614) 297-2300