Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

The Siege of Fort Meigs. 315

THE SIEGE OF FORT MEIGS.

BY H. W. COMPTON.

The construction of Fort Meigs by

General William Henry

Harrison in the early spring of 1813,

and its siege by the British

general, Proctor, and the renowned chief

Tecumseh in May of

that year, was one of the important

incidents in the war of 1812.

But few of those who now look at the

ruins of Fort Meigs, slum-

bering upon the high, grassy plateau

opposite the village of

Maumee, can realize the fearful struggle

that took place amid

those peaceful surroundings from May

first to May fifth, 1813.

The incessant roar of heavy artillery,

the ceaseless rattle of mus-

ketry, the shock of arms in the onset of

contending soldiers, British

and American, mingled with the piercing

yells of Tecumseh's

infuriated savages, for five days and

nights, during the frightful

siege, broke the quiet of the valley,

now dotted with its peaceful

homes and prosperous villages. To

understand aright the his-

toric importance of Fort Meigs' struggle

in the War of 1812 it

will be necessary to review the events

leading up to the construc-

tion of that important stronghold,

recount the main events of its

successful resistance to armed invasion,

and then point out the

beneficent result that ensued from the

valorous defense by Har-

rison and his beleaguered heroes.

The War of 1812, or

"Madison's War," as it was called by

unfriendly critics of the administration,

was declared June eigh-

teenth, 1812. There was great opposition

to the war in the sea-

board states, especially among the

bankers, merchants and manu-

facturers. A war with England was

greatly dreaded, as our weak

country was then just beginning to

recover from its long and ex-

haustive struggle for independence and

was beginning to reap

some of the fruits of peace and

prosperity. Many believed that

we had nothing to gain and much to lose

by a war with England,

as she had great armies in the field and

practically ruled the seas.

But the provocation to war was great,

and the national pride and

indignation of the Americans was roused

to the highest pitch by

the insolent aggressions of England

toward our commerce and

our sailors. England's "Orders in

Council," in reprisal for

The Siege of Fort Meigs. 317

Napoleon's Berlin and Milan decrees,

excluded our merchant ships

from almost every port of the world,

unless the permission of

England to trade was first obtained. In

defiance of England's

paper blockade of the world our ships

went forth to trade with

distant nations. Hundreds of them were

captured, their contents

confiscated and the vessels carried as

prizes into English ports.

But this was not all. The United States

recognized the right of

an alien to be "naturalized"

and become a citizen of this country,

but England held to the doctrine,

"Once an Englishman always

an Englishman." In consequence of

this our ships were inso-

lently hailed and boarded by the war

sloops and frigates of Eng-

land and six thousand American sailors

in all were dragged from

our decks and impressed into the British

service. In addition to

these insults and aggressions it was

well known to the United

States that English agents in the

Northwest were secretly aiding

and encouraging the wild Indian tribes

of the Wabash and Lake

Superior regions to commit savage

depredations upon our frontier

settlements. About this time an Indian

chieftain of the Shaw-

anese tribe, Tecumseh by name, like King

Philip and Pontiac

before him, conceived the idea of

rallying all the Indian tribes

together and driving the white men out

of the country.

Tecumseh was of a noble and majestic

presence, was pos-

sessed of a lofty and magnanimous

character and was endowed

with a gift of irresistible eloquence.

Tecumseh had a brother

called the Prophet, who claimed to be

able to foretell future events

and secure victories and effect

marvelous cures by his charms and

incantations. Harrison, then governor of

the Indiana Territory,

was active in securing Indian lands by

purchase and treaty for

supplying the oncoming tide of white men

who pressed hard upon

the Indian boundary lines. Tecumseh and

the Prophet sent their

emissaries abroad and organized a great

confederacy which re-

fused to cede the title to the lands of

the Wabash valley, as had

been agreed upon by separate

tribes. They even came down into

the valley and built a town where

Tippecanoe Creek flows into

the Wabash. Harrison, alarmed at these

signs of resistance,

called the plotters to account. The

Prophet, all of whose machina-

tions were based upon fraud and

deception, denied everything.

But Tecumseh marched proudly down to

Vincennes with four

318

Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

hundred braves behind him and in the

council, in a speech of great

eloquence and power, set forth the

burning wrongs of his people

and asked for justice and redress.

When Tecumseh had finished, an officer

of the governor

pointed to a vacant chair and said,

"Your father asks you to take

a seat by his side." Tecumseh drew

his mantle around him and

proudly exclaimed, "My father! The

sun is my father, and the

earth my mother, in her bosom I will

repose." He then calmly

seated himself upon the bare ground.

But the plotting and the intriguing

among the hostile Indians

continued, Tecumseh traveling everywhere

and inciting a spirit

of war and defiance. Harrison became

alarmed at the formidable

preparation of the savages and marched

from Vincennes with

nine hundred soldiers to disperse the

hostile camp at Prophet's

town on the Wabash at Tippecanoe. The

chiefs came out to meet

him and with professions of friendship

promised on the next day

to grant all that he desired. Harrison

was deceived by this recep-

tion and encamped upon the spot which

the chiefs pointed out.

In the dark hours of the early morning

the treacherous Prophet

and his inflamed followers crept

silently upon the sleeping soldiers

of Harrison, shot the sentinels with

arrows and with frightful

yells burst into the circle of the camp.

At the first fire the well-

trained soldiers rolled from their

blankets and tents and with

fixed bayonets rushed upon their red

foes. For two hours a

bloody struggle ensued, but the valor

and discipline of the whites

prevailed. The Indians were scattered

and their town was burned.

Tecumseh was not present at the battle

of Tippecanoe, but the

Prophet, at a safe distance upon a

wooded height, inspired his

braves by wild hallooings and weird

incantations. His pretenses

were so discredited by the result of the

battle that he was driven

out of the country and sank into

obscurity. But not so with

Tecumseh. His heart was filled with rage

and hatred against

Harrison and the American soldiers. He

knew that war was just

trembling in the balance between England

and the United States.

He immediately repaired to Malden at the

mouth of the Detroit

river and proffered the aid of himself

and his confederacy against

the United States. This famous battle of

Tippecanoe, fought in

the dark, November seventh, 1811, was really

the first blow

The Siege of Fort Meigs.

319

struck in the war which was openly

declared in the following June.

The Indians now fondly hoped that the

English would deliver

their country from the grasp of the

Americans. And the English

on their part were profuse in their

promises of speedy deliver-

ance and in their gifts of arms and

supplies of all kinds. The war

in the west was indeed but another

struggle for the possession

of the lands between the Alleghenies and

the Mississippi. And

had England won in the contest, not

Tecumseh and his confed-

eracy would have had the hunting grounds

of their forefathers

restored, but Canada would have been

enlarged by the addition

of the Old Northwest to her own domain.

It was far easier

for the United States to declare war

than to prosecute it to a suc-

cessful issue. Our country was without

an army and without a

navy and had but scanty means for

creating either. England had

armies of experienced veterans and a

vast navy. Ohio had less

than 250,000 inhabitants and her line of

civilized settlements did

not extend more than fifty miles north

of the Ohio River. What-

ever part Ohio, Indiana and Kentucky

should play in the contest

must be done by conveying troops and

munitions of war over a

road two hundred miles long through the

wilderness.

As the campaign was planned against

Canada these supplies

for the raw recruits of the west had to

be transported northward

over roads cut toward Lake Erie and

Detroit through the swamps

and tangled morasses of the unbroken

forest. The line of contest

between the two nations was over five

hundred miles long, extend-

ing from Lake Champlain to Detroit. The

Americans held three

important points of vantage, Plattsburg,

Niagara and Detroit.

The British held three on the Canada

side of the line, Kingston,

Toronto and Maiden. At the latter place

(now Amherstberg)

the British had a fort, a dockyard and a

fleet of war vessels, thus

controlling Lake Erie. The Americans

soon had three armies

in the field eager to invade and capture

Canada. One under Hull,

then governor of Michigan Territory,

with two thousand men,

was to cross the river at Detroit, take

Malden and march east-

ward through Canada. Another army under

Van Rensselaer was

to cross the Niagara River, capture

Queenstown, effect a junction

with Hull and then capture Toronto and

march eastward on Mon-

treal. The third army under Dearborn at

Plattsburg was to cross

320

Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

the St. Lawrence, join Hull and Van

Rensselaer before Montreal

and capture that city. The combined

forces were then to march

on Quebec, take that city and thus

complete the invasion and con-

quest of Canada. This fine program was

not carried out. It

would have taken the combined genius of

a Napoleon and a Caesar

to have executed such a plan of battle

over such immense dis-

tances.

The plain truth is the Americans had in

the field at this time

only raw, ill-disciplined troops and

absolutely no generals with

abilities which fitted them to command

such expeditions. Hull,

according to orders, crossed the Detroit

River to Sandwich and

there in vacillating indecision dawdled

away the time for several

weeks without advancing upon Malden only

a few miles away.

When he heard that Mackinac Island had

fallen into British

hands he began to quake in his boots,

and thought of retreating.

Soon he received news that an Ohio

convoy destined for Detroit

had been attacked and was in danger of

capture. This settled it.

Hull quickly retreated across the river

to Detroit with all his

forces with no thought but for

protecting his own line of com-

munication, for he had reached Detroit

originally from Urbana

by a road which he had cut through the

wilderness by way of

Kenton and Findlay. Brock, the brave and

skillful British gen-

eral commanding at Malden, immediately

followed Hull across

the river and demanded the surrender of

Detroit with threats of

a massacre by his Indian allies if Hull

did not comply. To his

credit be it said, Hull refused, and the

Americans prepared for

battle. Brock marched up to within five

hundred yards. The

Americans were ready and eager for the

fray and the artillerymen

stood at their guns with lighted

matches, when to the dismay

and shame of all, the Stars and Stripes

was lowered from the

flag staff of the fort and the white

flag of surrender was run up.

Hull had weakened at the last moment and

had given up the whole

of Michigan Territory, and also Detroit

with all its troops, guns

and stores, and even surrendered

detachments of troops twenty-

five miles distant. The officers and

soldiers of Hull were over-

whelmed with rage and humiliation at

this cowardly surrender.

The officers broke their swords across

their knees and tore the

epaulets from their uniforms. Poor old

Hull, it is said, had done

The Siege of Fort Meigs. 321

good service in the Revolutionary War,

but he had reached his

dotage and his nerve had departed, and

moreover he had a daugh-

ter in Detroit whom he dearly loved and

on whose account he

dreaded an Indian massacre.

Hull's troops had also been greatly

diminished in numbers,

the government had been negligent in

reinforcing him and he was

confronted by about one thousand British

soldiers and fifteen hun-

dred bloodthirsty Indians. These facts

may have helped to lead

him into this shameful and cowardly

capitulation. Hull was after-

wards courtmartialed and tried on three

charges of treason, cow-

ardice and conduct unbecoming an

officer. He was convicted on

the two latter charges and was sentenced

to be shot, but was sub-

sequently pardoned on account of former

services.

Another disaster in the West accompanied

Hull's surrender.

When he heard Mackinac had fallen he at

once sent Winnimac,

a friendly chief, to Chicago, and

advised Captain Heald, com-

manding at Fort Dearborn, to evacuate

the fort with his garrison

and go to Fort Wayne.

Heald heeded this bad advice. He

abandoned the fort with

his garrison of about sixty soldiers,

together with a number of

women and children. He had no sooner

left the precincts of the

fort than his little company was

attacked by a vast horde of treach-

erous Pottawatomies who had pretended to

be friends but who

had been inflamed by the speeches and

warlike messages of

Tecumseh. The little band of whites

resolved to sell their lives

as dearly as possible and defended

themselves with the utmost

bravery, even the women fighting

valiantly beside their husbands.

During the fray one savage fiend climbed

into a baggage wagon

and tomahawked twelve little children

who had been placed there

for safety. In this unequal contest

William Wells, the famous

spy who had served Wayne so well, lost

his life. Nearly all of the

little Chicago garrison were thus

massacred in the most atrocious

manner. In the meantime Van

Renssellaer's army at Niagara had

failed to take Queenstown and a part of

it under Winfield Scott,

after a brave resistance, had been

captured. Dearborn's army on

Lake Champlain passed the summer in

idleness and indecision

and accomplished nothing.

Vol. X - 21

322

Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

Thus closed with failure and disaster

the campaign of the

year 1812.

January, 1813, opened with still another

tragedy of the divest

character. General Winchester had been

appointed to the chief

command of the army of the west after

the surrender of Hull;

but this appointment raised a storm of

opposition among the

troops, who desired General Harrison to

be in supreme command.

Harrison was extremely popular among the

soldiers. His great

energy and his remarkable military

abilities were well known,

and, moreover, he was the hero of

Tippecanoe. Accordingly,

in obedience to the popular demand,

Harrison, in September of

1812, was appointed to the chief command

of the army of the

west. But Winchester still continued to

retain an important

command, and in January of 1813 he

marched his troops from

Fort Wayne and Defiance down the north

bank of the Maumee,

over Wayne's old route, to the foot of

the Rapids, in the hope

that he might be able to do something to

repair the disaster of

Hull's surrender. On his arriving at the

Rapids, messengers

from Frenchtown (now Monroe) informed

him that a force of

British and Indians were encamped at

Frenchtown and were

causing the inhabitants great loss and

annoyance. Winchester

at once set out for Frenchtown and on

January nineteenth attacked

and completely routed the enemy at that

place. Had he then

returned to the Rapids he would have

escaped the terrible disaster

which followed. The full British force was at Malden only

eighteen miles away. A force of fifteen

hundred British and

Indians immediately marched against

Winchester and attacked

him early on the morning of the

twenty-second. The battle was

fierce and stubborn. The Americans had

no entrenchments or

protection of any kind and were

overwhelmed by superior num-

bers. Those who were still alive, after

a bloody resistance, were

compelled to surrender. Then followed

such a scene of carnage

as has seldom been witnessed. Proctor,

the British commander,

stood calmly by while his Indian allies

mutilated the dead and

inflicted the most awful tortures upon

the wounded. Even those

who had surrendered upon condition that

their lives should be

spared were attacked by these savage

butchers with knife and

tomahawk. The awful deeds that followed

the surrender have

The Siege of Fort Meigs. 323

covered the name of Proctor with infamy

and have made "The

Massacre of the Raisin" a direful

event in history. When the

appalling news of the massacre reached

the settlements the people

of Pennsylvania, Kentucky and Ohio

girded themselves for

revenge. Ten thousand troops were raised

for Harrison and it

was determined to wipe out the disgrace

of Hull's surrender and

avenge the awful death of comrades and

friends so pitilessly and

treacherously butchered on the Raisin.

"Remember the Raisin,"

was heard in every camp and issued from

between the set teeth

of soldiers who in long lines began

converging toward the Rapids

of the Maumee.

It was under such circumstances as

these, with two armies

swept away and the country plunged in

gloom, that General Har-

rison began with redoubled energy to get

together a third army.

He at first thought of withdrawing all

troops from northwestern

Ohio and retreating toward the interior

of the state. But upon

second thought he resolved to build a

strong fortress upon the

southern bank of the Maumee at the foot

of the rapids which

should be a grand depot of supplies and

a base of operations

against Detroit and Canada. Early in

February of 1813, Harri-

son, with Captains Wood and Gratiot of

the engineer corps,

selected the high plateau of the

Maumee's southern bank lying

just opposite the present village of

Maumee. As the British com-

manded Lake Erie this was a strategic

point of great value and

lay directly on the road to Canada.

Below it armies and heavy

guns could not well be conveyed across

the impassable marshes

and estuaries of the bay. It was a most

favorable position for

either attack or defense, for advance or

retreat, for concentrating

the troops and supplies of Pennsylvania,

Kentucky, Ohio and In-

diana, or for effectively repelling the

invasion of the British and

their horde of savage allies from the

north. The construction of

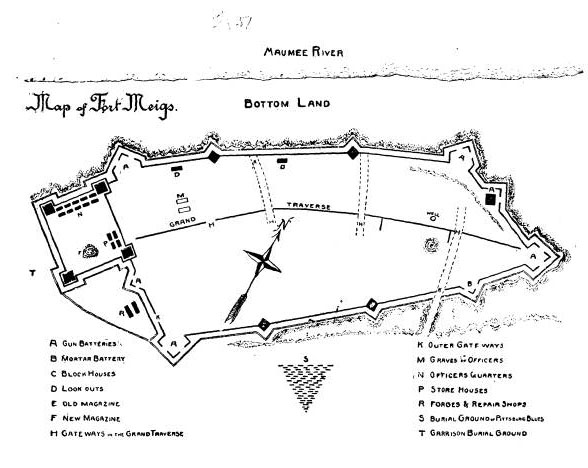

the fort was begun in February and

originally covered a space

of about ten acres. It was completed the

last of April, and was

named Fort Meigs in honor of Return

Jonathan Meigs, then gov-

ernor of Ohio. The fort was in the form

of an irregular ellipse

and was enclosed by sharpened palisades

fifteen feet long and

about twelve inches in diameter, cut

from the adjoining forest.

In bastions at convenient angles of the

fort were erected nine

324

Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

strong blockhouses equipped with cannon,

besides the regular gun

and mortar batteries. In the western end

of the fort were located

the magazine, forges, repair shops,

storehouses and the officers'

quarters. Harrison knew that Proctor was

preparing at Malden

for an attack on the fort and that he

would appear as soon as the

ice was out of Lake Erie. On April

twenty-sixth Proctor arrived

in the river off the present site of

Toledo with four hundred regu-

lars of the Forty-first regiment and

eight hundred Canadians, and

with a train of heavy battering

artillery on board his ships. A

force of eighteen hundred Indians under

Tecumseh swept across

in straggling columns by land from

Malden. The British landed

at old Fort Miami, a mile below Fort

Meigs, on the opposite side

of the river. Fort Miami was then in a

somewhat ruined con-

dition, as the British had abandoned it

shortly after Wayne's

victory eighteen years before. It was

hastily repaired and occu-

pied by the British, Tecumseh with his

Indians encamping close

by. The British landed their heavy guns

at the watergate of the

old fort and laboriously dragged them up

the long slope to the

high bank above. All night long they

toiled in erecting their siege

batteries. With teams of oxen and squads

of two hundred men

to each gun they hauled the heavy

ordnance through mud two feet

deep from old Fort Miami to the high

embankment just opposite

Fort Meigs. There, early on the morning

of May first, the British

had four strong batteries in position,

despite the incessant fire

which the Americans from Fort Meigs had

directed upon them.

These four batteries were known as the

King's Battery, the

Queens Battery, the Sailor's Battery and

the Mortar Battery, the

latter throwing destructive bombs of

various sizes. Harrison was

characterized by great foresight and

penetration as a general.

On the night the British were planting

their batteries, realizing

that he had an available force of less

than eight hundred men, he

dispatched a brave scout, Captain

William Oliver, to General

Green Clay, who he knew was on the way

with a large force of

Kentuckians, to bid him hurry forward

with his reinforcements.

On the same night he set his men to work

with spades and threw

up the "grand traverse," an

embankment of earth extending longi-

tudinally through the middle of the

fort, nine hundred feet long,

twelve feet high and with a base width

of twenty feet. The tents

The Siege of Fort Meigs. 325

were taken down and the little army

retired behind the great

embankment and awaited the coming storm,

which broke in fury

at dawn, on May first. The British

batteries all opened at once

with a perfect storm of red-hot solid

shot and screaming shells,

which fell within the palisades, plowed

up the earth of the grand

traverse or went hissing over the fort

and crashed into the woods

beyond. The soldiers protected

themselves by digging bomb-

proof caves at the base of the grand

traverse on the sheltered side,

where they were quite secure, unless by

chance a spinning shell

rolled into one of them. For several

days and nights the troops

ate and slept in these holes under the

embankment, ever ready to

rush to the palisades or gates in case

of a breach or an assault.

During the siege a cold, steady rain set

in and the underground

bomb-proof retreats gradually filled

with water and mud. The

soldiers were compelled to take to the

open air behind the embank-

ment, where, having become used to the

terrible uproar, they ate,

slept, joked and played cards. It is

related that Harrison offered

a reward of a gill of whisky for each

British cannon ball that

should be returned to the magazine

keeper. On a single day of

the siege, it is said, a thousand balls

were thus secured and hurled

back by the American batteries, which

constantly replied to the

British fire, night and day, frequently

dismounting their guns.

One of the American militiamen became very

expert in detecting

the destined course of the British

projectiles and would faithfully

warn the garrison. He would take his

station on the embankment

in defiance of danger. When the smoke

issued from the gun he

would shout, "Shot," or

"Bomb," whichever it might be. At times

he would say, "Blockhouse No.

1," or "Main battery," as the case

might be. Sometimes growing facetious he

would yell, "Now for

the meat-house," or if the shot was

high he would exclaim, "Now,

good-bye, if you will pass." In

spite of danger and protests he

kept his post. One day he remained

silent and puzzled, as the

shot came in the direct line of his

vision. He watched and peered

while the ball came straight on and

dashed him to fragments.

On the third night of the siege a

detachment of British, together

with a large force of Indians, crossed

the river below Fort Meigs

and, passing up a little ravine, planted

on its margin, southeast

326

Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

of the fort, and within two hundred and

fifty yards, two new

batteries.

The garrison was now subjected to a

terrible crossfire, and

the Indians, climbing trees in the

vicinity, poured in a galling rifle

fire, killing some and wounding many of

the garrison. On the

morning of the fourth of May, Proctor

sent to Harrison a demand

for the surrender of the fort. Harrison

replied to the officer who

bore Proctor's demand, "Tell your

general that if he obtains pos-

session of this fort it will be under

circumstances that will do him

far more honor than would my

surrender." And again the cease-

less bombardment on both sides began. On

the night of May

fourth Captain Oliver crept into the

fort under cover of darkness

and informed Harrison that General Green

Clay with twelve hun-

dred Kentucky militia was at that moment

descending the

Maumee in eighteen large barges and

could reach the fort in two

hours, but would await the orders of

Harrison. The command

was immediately sent out for Clay to

come down the river, land

eight hundred men on the northern bank,

seize and spike the

British cannon and then immediately

cross the river to Fort

Meigs. The other four hundred

Kentuckians were ordered to

land on the southern bank directly under

the fort and fight their

way in at the gates, the garrison in the

meantime making sallies

to aid in the movement. Colonel Dudley,

being second in com-

mand, led the van and landed his boats

about one mile above the

British batteries on the northern bank

of the river. He formed

his eight hundred men in three lines and

marched silently down

upon the batteries in the darkness. The

Kentuckians took the

British completely by surprise. They

closed in upon the guns and

charged with the bayonet, the artillery

men and Indians fleeing

for their lives. They spiked the British

guns and rolled some of

them down the embankment, but

unfortunately the spiking was

done with ramrods instead of with the

usual steel implements,

and the British subsequently put the

guns in action again. Had

the Americans now obeyed the orders of

Harrison and crossed

the river and entered the fort all would

have been well. But the

Kentucky militia were eager for a fight,

and elated by their success

in capturing the batteries, they began a

pursuit of the fleeing

The Siege of Fort Meigs. 327

Indians. In vain they were called to by

friends from Fort Meigs,

who saw their danger.

Wildly the cheering Kentucklians dashed

into the forest after

the flying savages, who artfully led

them on. Then deep in the

recesses of the forest a multitude of

savages rose up around them.

Tomahawks were hurled at them and shots

came thick and fast

from behind trees and bushes. Realizing

that they had fallen

into an ambuscade, they began a hasty

and confused retreat toward

the batteries. But in the meantime the

British regulars had come

up from old Fort Miami and thrown

themselves between the river

and the retreating Americans. About one

hundred and fifty cut

their way through and escaped across the

river. At least two

hundred and fifty were cut to pieces by

the savages and about

four hundred were captured. The

prisoners were marched down

to the old fort to be put on board

ships. On the way the Indians

began butchering the helpless prisoners.

Tecumseh, far more humane than his white

allies, hearing

of the massacre, dashed up on his horse,

and seeing two Indians

butchering an American, he brained one

with his tomahawk and

felled the other to the earth. Drake

states that on this occasion

Tecumseh seemed rent with grief and passion

and cried out, "Oh,

what will become of my poor Indians

!" Seeing Proctor standing

near, Tecumseh sternly asked him why he

had not stopped the

inhuman massacre. "Sir, your

Indians cannot be commanded,"

replied Proctor. "Begone, you are

unfit to command; go and put

on petticoats," retorted Tecumseh.

After this incident the pris-

oners were not further molested.

On the other side of the river events

had gone quite differ-

ently. The four hundred who landed on

the south bank, with

the help of a sallying party, after a

bloody struggle, succeed d in

entering the fort. At the same time the

garrison made a brilliant

sortie from the southern gate and

attacked the batteries on the

ravine. They succeeded in spiking all

the guns and captured

forty-two prisoners, two of them British

officers. After this an

armistice occurred for burying the dead

and exchanging pris-

oners. Harrison prudently took advantage

of the lull in the con-

flict to get the ammunition and

supplies, that had come on the

boats, into the fort. The batteries then

again resumed fire, but

328

Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

the Indians had become weary of the

siege, a method of warfare

so much opposed to their taste and

genius. They had become

glutted, too, with blood and scalps, and

were heavily laden with

the spoils of Dudley's massacred troops.

So in spite of Tecum-

seh's protests, they gradually slipped

away in the forest toward

their northern homes. Proctor now became

disheartened by the

desertion of his allies and feared the

coming of more reinforce-

ments for Harrison. The Stars and

Stripes still waved above the

garrison, and Fort Meigs was stronger

and more impregnable

than ever. Sickness broke out among the

British troops encamped

upon the damp ground and squads of the

Canadian militia began

to desert, stealing away under cover of

darkness. Tecumseh,

unconquerable and determined, still

remained upon the ground

with four hundred braves of his own

tribe, the Shawanese.

Few of the present day can know or even

imagine the horrible

scenes that took place within the

precincts of Tecumseh's camp

shortly after the massacre of Dudley's

troops. A British officer

who took part in the siege, writing in 1826, tells of a

visit to the

Indian camp on the day after the

massacre. The camp was filled

with the clothes and plunder stripped

from the slaughtered sol-

diers and officers. The lodges were

adorned with saddles, bridles

and richly ornamented swords and

pistols. Swarthy savages

strutted about in cavalry boots and the

fine uniforms of American

officers. The Indian wolf dogs were

gnawing the bones of the

fallen. Everywhere were scalps and the

skins of hands and feet

stretched on hoops, stained on the

fleshy side with vermillion, and

drying in the sun. At one place was

found a circle of Indians

seated around a huge kettle boiling

fragments of slaughtered

American soldiers, each Indian with a

string attached to his par-

ticular portion. Being invited to

partake of the hideous repast,

the officer relates that he and his

companion turned away in

loathing and disgust, excusing

themselves with the plea that they

had already dined. On the ninth of May,

despairing of reducing

Fort Meigs, Proctor anchored his

gunboats under the batteries,

and although subjected to constant fire

from the Americans, em-

barked his guns and troops and sailed

away to Malden. But

before dismounting the batteries, they

all fired at once a parting

salute, by which ten or twelve of the

Americans were killed and

The Siege of Fort Meigs. 329

about twenty-five wounded. Thus for

about twelve days was the

beleaguered garrison hemmed in by the

invading horde. The

Americans suffered them to depart

without molestation, for, as

one of the garrison said, "We were

glad to be rid of them on any

terms." The same writer says:

"The next morning found us

somewhat more tranquil. We could leave

the ditches and walk

about with more of an air of freedom

than we had done for four-

teen days; and I wish I could present to

the reader a picture of the

condition we found ourselves in when the

withdrawal of the

enemy gave us time to look at each

other's outward appearance.

The scarcity of water had put the

washing of our hands and

faces, much less our linen, out of the

question. Many had scarcely

any clothing left, and that which they

had was so begrimed and

torn by our residence in the ditch and

other means, that we pre-

sented the appearance of so many

scarecrows." Proctor appeared

again in the river ten days later, with

his boats, and Tecumseh

with his Indians, and remained in the

vicinity of the fort from

July twentieth to the twenty-eighth.

This visitation constitutes

what has been called the second siege of

Fort Meigs. Their force

this time is said to have consisted of

about five thousand whites

and Indians, but they attempted no

bombardment and no assault.

The Indians contented themselves with

capturing and murdering

a party of ten Americans whom they

caught outside the fort.

It was during this siege that the

Indians and British secreted

themselves in the woods southeast of the

fort and got up a sham

battle among themselves, with great

noise and firing, in order

to draw out the garrison. But this ruse

did not deceive General

Clay, then in command, although many of

the soldiers angrily

demanded to be led out to the assistance

of comrades who, they

imagined, had been attacked while coming

to relieve the besieged

garrison. On the twenty-eighth Proctor

and his Indian allies

again departed, going to attack Fort

Stephenson, whose glorious

victory under young Crogan was one of

the great achievements

of the War of 1812.

During the siege of Fort Meigs from May

first to the fifth,

beside the massacred troops of Colonel

Dudley, the garrison, in

sorties and within the fort, had

eighty-one killed and one hundred

and eighty-nine wounded. The sunken and

grass-grown graves

330 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

of the heroes who lost their lives at

Fort Meigs are still to be

seen upon the spot.

The events that followed the heroic

resistance of Fort Meigs

are no doubt too well known to require

narration.

The famous victory of Perry in the

following September

cleared Lake Erie of the British fleet.

Proctor and Tecumseh fled

from Maiden and Harrison's army pursued,

overtaking them at

the Thames. There the British were

completely routed and the

brave Tecumseh was slain. This put an

end to the war in the

West and Michigan and Detroit again

became American pos-

sessions.

The important part which Fort Meigs

played in the war can

now be seen. It was the rallying point

for troops, and the great

storehouse of supplies for the western

army. It was the Gibraltar

of the Maumee valley and rolled back the

tide of British invasion

while Perry was cutting his green ship

timbers from the forest

around Erie, and it was to Harrison at

Fort Meigs that Perry's

world-famed dispatch came when the

British fleet had struck

their colors off Put-in-Bay: "We

have met the enemy and they

are ours; two ships, two brigs, one

schooner and one sloop." All

honor to old Fort Meigs! The rain and

the frost and the farmer's

plow are fast obliterating the ruins of

the grand old stronghold

that once preserved the great Northwest

for the United States.

Little remains there now, where the roar

of battle broke the air,

and the devoted band of patriots stood

their ground under the

shower of iron hail and shrieking shells

that for days were hurled

upon them. The long green line of the

grand traverse, with its

four gateways, still stretches across

the plain and the peaceful

kine are browsing along its sides. And

nearby, sunken, un-

marked, weed-grown and neglected, are

the graves of the heroic

dead who fell in the fearful strife.

[The foregoing paper was read by Mr.

Compton at the annual meet-

ing of the Maumee Valley Pioneer

Association, at Bowling Green, Ohio.

August 16, 1900.-E. O. R.-Editor.]

The Siege of Fort Meigs. 315

THE SIEGE OF FORT MEIGS.

BY H. W. COMPTON.

The construction of Fort Meigs by

General William Henry

Harrison in the early spring of 1813,

and its siege by the British

general, Proctor, and the renowned chief

Tecumseh in May of

that year, was one of the important

incidents in the war of 1812.

But few of those who now look at the

ruins of Fort Meigs, slum-

bering upon the high, grassy plateau

opposite the village of

Maumee, can realize the fearful struggle

that took place amid

those peaceful surroundings from May

first to May fifth, 1813.

The incessant roar of heavy artillery,

the ceaseless rattle of mus-

ketry, the shock of arms in the onset of

contending soldiers, British

and American, mingled with the piercing

yells of Tecumseh's

infuriated savages, for five days and

nights, during the frightful

siege, broke the quiet of the valley,

now dotted with its peaceful

homes and prosperous villages. To

understand aright the his-

toric importance of Fort Meigs' struggle

in the War of 1812 it

will be necessary to review the events

leading up to the construc-

tion of that important stronghold,

recount the main events of its

successful resistance to armed invasion,

and then point out the

beneficent result that ensued from the

valorous defense by Har-

rison and his beleaguered heroes.

The War of 1812, or

"Madison's War," as it was called by

unfriendly critics of the administration,

was declared June eigh-

teenth, 1812. There was great opposition

to the war in the sea-

board states, especially among the

bankers, merchants and manu-

facturers. A war with England was

greatly dreaded, as our weak

country was then just beginning to

recover from its long and ex-

haustive struggle for independence and

was beginning to reap

some of the fruits of peace and

prosperity. Many believed that

we had nothing to gain and much to lose

by a war with England,

as she had great armies in the field and

practically ruled the seas.

But the provocation to war was great,

and the national pride and

indignation of the Americans was roused

to the highest pitch by

the insolent aggressions of England

toward our commerce and

our sailors. England's "Orders in

Council," in reprisal for

(614) 297-2300