Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

John A. Bingham. 331

JOHN A. BINGHAM.

ADDRESS OF HON. J. B. FORAKER ON THE

OCCASION OF THE

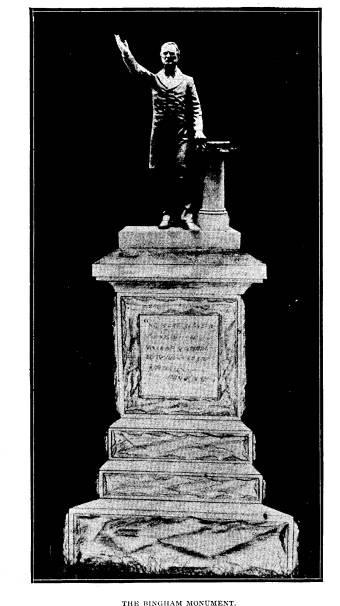

UNVEILING OF MONUMENT IN HONOR OF HON.

JOHN A.

BINGHAM, AT CADIZ, OHIO, OCTOBER 5,

1901.

Mr. Chairman and Fellow Citizens:

The private life and character of John

A. Bingham were

the special possessions of this

community.

You were his neighbors and friends.

He came and went in your midst.

You were in daily contact with him.

You knew him under all the varying

circumstances of his

long and eventful career.

You saw him tested by the trying

vicissitudes of the tem-

pestuous times with which his most

conspicuous public service

was identified.

You knew better than anybody else can

his private life and

character, and time and again you

honored him with your con-

fidence and attested your high estimate

of his personal worth,

his integrity, and his splendid

qualities of nature and heart.

It would be almost out of place for me

to speak of him on

these points in this presence.

As to his public life, it is different.

It is the common prop-

erty of the whole country -mine as well

as yours. This monu-

ment is in its honor and this occasion

calls for its review.

The first twenty-five years of his life

were spent in prepara-

tion; the last fifteen in retirement.

The other forty-five years that he lived

were devoted almost

exclusively to the public service.

He entered upon his career with a mind

all aflame with zeal

for the great work in which he was to

engage.

He dealt with all the economic questions

of his day-

finance, taxation, national banks, the

tariff, and public improve-

ments; but the subjects with which his

fame is linked were

slavery, secession, rebellion, and

reconstruction.

To intelligently appreciate his work, we

must approach it

as he did.

|

332 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

Slavery was a disquieting subject when the Union was or- ganized and the Constitution was adopted. It was only by com- promise, aided and made possible by the hope, then generally entertained, that slavery would somehow be soon abolished, that success was achieved. But slavery did not perish, as anticipated. On the contrary, it grew in strength. |

|

|

|

The development of the cotton industry and the adaptability to it of slave labor gave the South a new and an increased in- terest in the maintenance of the institution. As a result, it soon became a political question. It assumed threatening proportions when the admission of Missouri as a State to the Union, with a slave constitution, was proposed in 1818. The debates that ensued took on a sectional aspect which was made permanent and intensified by the Missouri Compromise, effected in 1820, according to which both Maine and Missouri were admitted-one free and the other slave; and it was stipu- lated and enacted that never thereafter should any State be admitted with slavery north of 36o 30' north latitude. |

John A. Bingham. 333

Both Democrats and Whigs undertook to

treat the line so

drawn as a permanent settlement of the

territorial rights of

slavery, and a period of comparative

political peace followed.

For twenty years both Whigs and

Democrats devoted them-

selves to business questions, and, so

far as they were concerned,

succeeded in keeping slavery effectually

in the background.

But God was marching on.

While Clay and Jackson and their

respective adherents were

battling over the issues they saw fit to

make with each other, a

new political force was entering the

arena, at first weak and un-

noticed except to be despised, but

destined to grow strong enough

to overthrow both parties and compel

reorganization on new lines

that had direct reference to slavery.

This new force assumed a party name and

made its first ap-

pearance as a national organization in 1840, the same

year that

Mr. Bingham was admitted to the bar.

He was then twenty-five years of age,

and blessed with a

thoroughly sound mind in a thoroughly sound

body. His life

had been one of struggle and endeavor.

It had strongly devel-

oped his great mental powers. He had a

natural aptitude for

public affairs. This quality was

intensified by the discussion of

the times. Webster, Calhoun, Clay,

Jackson, Van Buren, Ben-

ton, Marcy, Corwin, Chase, and their

associates were the political

leaders then on the stage of action.

When they spoke they

challenged attention and aroused all the

mental activities that

men possessed.

The preparatory steps could not have

been better ordered if

they had been taken with special

reference to the famous log

cabin, coon-skin, and hard cider

campaign that marked the year

of Mr. Bingham's first appearance in

public and made the hero of

Tippecanoe President of the United

States.

There was intense excitement everywhere.

All classes of

people talked politics and little else.

Mr. Bingham's tastes and acquirements

were such that he

would have doubtless drifted into the

discussion if conditions

had been normal, but under the

circumstances that obtained, he

could not have kept out if he had tried.

334 Ohio Arch. and His. Society

Publications.

He actively participated and at once

attracted attention and

commanded respect for his ability,

logic, and oratory.

That campaign, with all its excitements,

was not, however,

of a character to call forth his full

powers. The Whig party, to

which he belonged, had no platform

except their candidate, and

only economic questions were involved in

the discussion.

The great moral question that was so

soon to absorb all at-

tention was kept in the background.

It appeared in the contest, but only as

a little cloud on the

horizon no bigger than a man's hand.

It was represented by the Abolition

party which then, for the

first time, placed a candidate in the

field; but he received from

all the States an aggregate of less than

7,000 votes. This did

not affect the result. It showed less

strength than had been

conceded. It was thought the result

would discourage the cause,

but its champions were resolute,

determined men of a high order

of ability, who, acting upon conviction,

had no thought of sur-

render.

Ridicule, derision, and mob violence-to

all of which they

were subjected - only

inflamed their zeal. The names of Owen

Lovejoy, Wendell Phillips, William Lloyd

Garrison, and many

others associated with them as leaders

in this movement, were

soon to become familiar to the American

people.

They were commonly abused, maligned,

hated, and detested,

but they held steadily to their work,

commanded attention, and

constantly increased their followers.

Events helped them.

Harrison was dead and Tyler had

succeeded to the Presi-

dency. He quarreled with the Whigs, who

had elected him, and

undertook to secure the support of the

Democrats by making John

C. Calhoun his Secretary of State. Calhoun

disliked him, but

two considerations moved him to accept;

one was the opportunity

it gave him to serve the South by

bringing about the annexation

of Texas and thus adding to the area of

slave Territory, and the

other was the chance it thereby gave him

to overthrow Van

Buren, to whose leadership and candidacy

for renomination as the

Democratic candidate in 1844 he was

openly and bitterly opposed.

John A. Bingham. 335

He was not long in solidifying the South

in favor of annexa-

tion. That brought the slavery question

at once to the front and,

with singular fatality, destroyed both

Clay and Van Buren.

To hold his strength in the North, Van

Buren announced that

he was opposed to annexation. The result

was that while he

had a majority of the delegates, the

South controlled more than

one-third of the convention and;

consequently, under the two-

thirds rule, his nomination became

impossible, and James K.

Polk was made the nominee and Van

Buren's leadership was

ended forever.

Mr. Clay was under the same compulsion.

He could not be

elected unless he could hold his

northern strength, and therefore

he opposed annexation. This gave him the

nomination, and un-

doubtedly would have given him also the

election if he had not,

in the midst of the campaign, to mollify

the dissatisfied Whigs

of the South, written his famous Alabama

letter, in which he

virtually retracted his former

declaration, by naming conditions

under which he would favor annexation.

Until the writing of this letter, his

position was satisfactory

to all the anti-slavery Whigs of the

North; but his letter was

regarded as a virtual surrender of what

had become the all-

absorbing question of the contest, and,

as a result, thousands of

men who had become hostile to slavery

broke away from a party

that no longer gave hope of earnest

opposition to its aggravating

pretensions.

The result of the election depended on

New York, and the

defection was so great in that State

that, with the loss of the

heavily increased Abolition vote, the

Whigs were defeated. The

electorial vote went to Polk, and he was

made President of the

United States, in the interests of

slavery, by the combined vote

of the Abolitionists and the

slaveholders and their sympathizers.

The result was strangely and almost

mysteriously reached,

but it was of most momentous character.

Clay was defeated, and the hearts of his

followers were

broken. It seemed to them a strange and

unjust dispensation of

Providence. They could not understand

it, and for a time re-

fused to be reconciled. Men who had been

watching, hoping, and

336

Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

praying for the decline and extinction

of slavery as necessary to

the peace and preservation of the Union,

viewed the acquisition of

Texas with alarm and despair.

But the hand of God was in it all, and

what was then so in-

comprehensible has been made plain by

His unfolded purposes.

Except only then and in the manner in

which it was effected,

Texas probably never could have been

peaceably added to the

United States. But however that may be,

its acquisition was

the beginning of the "irrepressible

conflict."

The issue was joined and the battle was

to the death which

was to determine whether this country

should be all slave or

all free.

The war with Mexico accentuated the

dispute and made sec-

tional differences irreconcilable.

Although slavery was all the while at

the bottom of the con-

troversy, yet it from time to time took

on various forms of dis-

cussion.

Thoughtful conservative men taxed their

powers and their

ingenuity to devise methods and measures

to allay discussion and

appease the demands of public sentiment,

but no sooner was one

question settled than another arose, and

thus the tide, although

at time apparently subsiding, was constantly

rising until, finally,

sweeping all before it, the dread

alternative of arms was reached

and the ultimate settlement was made in

blood.

The South, foreseeing that the North was

outstripping her

in the growth of population and

political power, and that the time

would inevitably come when she could no

longer retain control

of the Government, espoused the doctrine

of secession, according

to which any State had a constitutional

right to withdraw from

the Union whenever it might see fit to

do so. She intended by

this rule which she could and then

destroy when control was

lost and on the ruins build anew with

slavery as the chief corner-

stone of her structure.

At the same time arose the question of

the rights of slavery

in the Territories, and John C. Calhoun,

to give it a status there

and make more slave States possible,

advanced the doctrine, of

which we have recently heard so much,

that the Constitution fol-

|

John A. Bingham. 337 |

|

|

|

Vol. X -22 |

338

Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

lowed the flag, and hence gave the same

protection to slave owner-

ship there that it gave in the States.

The Wilmot Proviso, the Lecompton

Constitution, squatter

sovereignty, the Fugitive Slave Law, the

Dred Scott Decision,

the repeal of the Missouri Compromise,

and the Kansas-Nebraska

Act are names and phrases that suggest

the varying and succeed-

ing phases of the discussion and

subordinate questions and propo-

sitions, about which there is no time to

speak adequately within

the limitations of this occasion.

It is enough to say they mark the

character and the progress

of the political debates in which Mr.

Bingham became an active

participator.

It is no exaggeration to say that they

were the greatest ques-

tions the American people had dealt with

since the Government

was organized, and the men who conducted

the debate were the

ablest since the formative period of the

Republic.

To attain prominence and distinction

among them and be a

leader of such leaders was the uncommon

honor Mr. Bingham

achieved.

In 1848, when he was but thirty-three

years of age, he was

made a delegate to the National Whig

Convention at Philadelphia,

and, by what seemed at the time a

fruitless effort, made for him-

self, at one stroke, a national

reputation.

It was known before the convention met

that General Taylor

would be its nominee, but its platform

declarations had not been

determined.

The slavery question was uppermost in

the minds of all;

yet both the Democrats and Whigs were

anxious to evade it-

the Democrats, to save their strength in

the North, and the Whigs

to hold their strength in the South.

Accordingly, to the keen

disappointment of thousands of their

respective followers, both

conventions practically ignored the

whole slavery question.

The Whigs were saved at the election by

the Free Soilers,

who drew largely from the Democrats but

only slightly from

the Whigs because of their dislike of

Van Buren, who headed

the movement as its candidate.

John A. Bingham. 339

Taylor was elected, but his party was

incapable because it did

not have the courage of its convictions.

It went to pieces while in power, as all

such parties will, and,

with the humiliating defeat of General

Scott in 1852, gave way

to the Republican party born of the

people to do their will.

"All is well that ends well,"

and, therefore, measured by

what followed, it is well that the Whig

party perished.

But if Mr. Bingham had been allowed his

way, the Whig

party need not have died. It might not

have elected Taylor, but

it would have marshalled later the

triumphant forces led by

Lincoln.

He showed his grasp of the situation and

his knowledge of

its requirements, as well as his

convictions of right and his cour-

age to maintain them, when, in that

convention, he offered the

famous resolution which you have carved

on his monument, that

it may be linked with him in death as it

was inseparable in life

"NO MORE SLAVE STATES; NO MORE

SLAVE

TERRITORIES- THE MAINTENANCE OF FREEDOM

WHERE FREEDOM IS AND THE PROTECTION OF

AMERICAN INDUSTRY."

These sharp, decisive sentences, going

to the very marrow

of the political contentions of the

time, were rejected by the con-

vention, but they cut into the hearts of

men and made the name

of John A. Bingham dear to every enemy

of slavery.

They crystallized a sentiment and

formulated a policy.

They appealed to the conscience and gave

an intelligent and

inspiring purpose to political action.

It is difficult for us, in the light of

the present, to realize the

full measure of credit to which Mr.

Bingham is entitled for the

courage he displayed in thus firmly and

explicitly taking such a

stand.

The evil of slavery, the curse it was to

the country, and the

blessings that have resulted from its

extinction, are all so manifest

that we are not surprised to learn that

men were then opposed to

it; on the contrary, it seems so natural

that it should have had

opposition that we wonder rather that

anybody should have de-

340 Ohio

Arch. and His. Society Publications.

fended it; but prevailing public

sentiment on the subject was then

radically different from that which it

was destined soon to become.

The institution was recognized and

protected by the Constitu-

tion. It could not be interfered with in

the States without violat-

ing that organic law and also numerous

statutory provisions that

had been enacted in its behalf.

It involved great moneyed interests and

was upheld by

prejudices in its favor throughout the

North as well as in the

South. It was like striking at the law,

order, and peace of the

nation to attack or criticise it.

Some idea of the sensitiveness that

prevailed with respect to

it is given by what has been said as to

the disposition of the two

great parties and their respective

leaders to keep it out of the

politics of the times.

Bingham had to brave all this and did.

He took the lead, while change of

sentiment was inaugu-

rated by the discussion he provoked, yet

four years later, when

1852 came, so little progress had been

made that the Whig party

approved in its platform all the

pro-slavery legislation that had

been enacted, expressly including the

iniquitous fugitive slave law

"as a settlement in principle and

substance of the dangerous and

exciting questions" that had been

raised in regard to slavery,

and pledged itself to

"discountenance all efforts to continue or

renew such agitation, whenever,

wherever, or however the attempt

may be made; and we will maintain the

system as essential to the

nationality of the Whig party and the

integrity of the Union."

These declarations were intended to

suppress the Binghams

and all the other troublesome agitators.

They failed in their

purpose, but they show the deplorable

state to which the Whig

party had been reduced by the cowardice

of its leaders in the

presence of that great question.

They also show how far Mr. Bingham was

in advance of

public sentiment and to what extent he

was defying it; they

show, too, how he was at variance with

his party and practically

in rebellion against it.

It is easy for a young, ambitious man to

go with the current

and stand in line with his party, but

only the man with clear judg-

John A. Bingham. 341

ment, conscientious scruples, and

approved courage will disregard

these considerations and stand by his

conceptions of right, truth,

and justice.

That is what Mr. Bingham determined to

do, and he did it.

He did not have to wait long for the

reward of vindication.

It came with the birth of the Republican

party, which espoused

the sentiments he had avowed and sent

him to Congress in 1854

at the early age of thirty-nine years.

His record there covers sixteen years of

service so faithful

and so distinguished that its history is

for that period by the

history of his party and his country.

He served on the most important

committees and held the

most important chairmanships. He gave

diligent and unremitting

attention to all the work assigned him.

He participated in all

the debates that occurred and always

showed a learning, a re-

search, an ability, a readiness, and an

oratory that gave him a first

rank among the great men of that great

time. He was a veritable

pillar of strength to the cause of

freedom, the cause of the Union,

and the cause of reconstruction. His

speeches were so numerous

and so notable that anything like a

proper review of them in detail

would require a volume. But, as showing

the political atmos-

phere by which he was surrounded, the

spirit of bitterness that

entered into the debates in which he

participated, and also to

show his ability, his eloquence, and his

intense earnestness, one

of his earliest efforts may be

mentioned.

The first session of Congress in which

he sat as a member,

commenced in December, 1855.

The struggle of the slave power to

capture Kansas and Ne-

braska was then ripening to its climax.

The question entered into the

organization of the House of

Representatives, and many weeks passed,

filled with angry debate,

before Nathaniel P. Banks, of

Massachusetts, was finally chosen

to be Speaker over William Aiken of

South Carolina.

Mr. Bingham took a modest, yet, for a

new member, a very

prominent part in this struggle.

It was scarcely ended until he made his

first formal speech.

Kansas was his theme, and it is enough

to say that he did the

subject justice.

342 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

But a few weeks later, he thrilled with

pride and enthusiasm

the hearts of his associates and

followers throughout the nation

and correspondingly angered and inflamed

his opponents by his

burning words of denunciation of slavery

spoken in the debate on

the resolution to expel Preston S.

Brooks of South Carolina, from

the House of Representatives, because of

his brutal attack on

Charles Sumner, whom he struck down and

beat almost to death

with his cane on the floor of the Senate

for words spoken, as a

Senator from Massachusetts, against

slavery and its aggressions

in the Territories.

This debate was one of the most bitter

that preceded the war.

Mr. Bingham took the floor to make

immediate answer to Mr.

Clingman of North Carolina, who, in

common with his fellow

members from the South, who participated

in the debate, had

most abusively spoken of Mr. Sumner and

of all who sympa-

thized with the doctrines enunciated by

him in the great speech

that provoked the assault.

The brutal character of this speech,

added to the brutal as-

sault, had thoroughly aroused Mr.

Bingham. It stirred him to

his very depths. As a result, he rose to

the highest flights of

eloquence.

An extract will show not only his

ability, his oratory, his elo-

quence, his fearlessness, and his powers

of vehement invective,

but also the general character of the

discussions of that time.

In the course of his speech he said:

"The brilliant and distinguished

Senator from Massachusetts is

the subject of this assault-that Senator

who, notwithstanding the

attempt of the gentleman from North

Carolina (Mr. Clingman) to

defame him, holds now, and will hold, a

large place in the affection and

admiration of his countrymen. That

Senator, sir, denounced the auda-

cious crime which is being committed in

Kansas. In his place as Senator,

he made a powerful and convincing

argument against the unparalleled

conspiracy which is subjecting that

young empire of the West to a cruel

and relentless tyranny -a

tyranny which inflicts death on citizens guilty

of no offense against the laws; which

sacks their towns and plunders

and burns their habitations; which

legalizes, throughout that vast extent

of territory, chattel slavery, -that

crime of crimes, -that sum of all

villainies, which makes merchandise of

immortality, and, like the curse

of Kehama, smites the earth with

barrenness--that crime which blasts

the human intellect and blights the

human heart, and maddens the human

John A. Bingham. 343

brain, and crushes the human soul-that

crime which puts out the light

and hushes the sweet voices of

home--which shatters its altars and

scatters darkness and desolation over

its hearthstone--that crime which

dooms men to live without knowledge, to

toil without reward, to die

without hope--that crime which sends

little children to the shambles

and makes the mother forget her love for

her child in the wild joy she

feels that through untimely death

inflicted by her own hands, she has

saved her offspring from this damning

curse, and sent its infant spirit

free from this horrid taint, back to the

God that gave it.

"Against this infernal and

atrocious tyranny upheld and being

accomplished through a tremendous

conspiracy, the Senator from Mas-

sachusetts, faithful to his convictions,

faithful to the holy cause of lib-

erty, faithful to his country and his

God, entered his protest, and uttered

his manly and powerful denunciation.

* * * *

"That Senator, sir, comes from

Massachusetts, where are Lexington

and Concord and Bunker Hill and the Rock

of the Pilgrims--'where

every sod's a soldier's sepulchre'

-where are the foot-prints of the

apostles and martyrs of freedom--that

State which allowed a trembling

fugitive, fleeing only for his liberty,

to lay his weary limbs to rest upon

Warren's grave--that State

whose mighty heart throbbed with human

sympathy for the flying bondman who,

guilty of no crime under the

forms of law, but in violaton of its

true spirit, walked in chains beneath

the shadow of Faneuil Hall, where linger

the sacred memories of the

past and the echoes of those burning

words, Death or deliverance."

It would be a pleasing task to cite and

dwell upon many other

of the great speeches he made, but time

will not permit. His

many important public services as

counsel for the Government in

the causes he tried as Judge Advocate

General by appointment

of Abraham Lincoln, whose confidence and

friendship he enjoyed

to the fullest degree, must be passed

over unmentioned for the

same reason.

So, also, the important and conspicuous

service he rendered

as manager on behalf of the House of

Representatives in the im-

peachment of Andrew Johnson.

This may be done with much less regret,

because, notwith-

standing their distinguished character,

they were transient in

their nature. His many permanent

services are all important.

None can be mentioned and analyzed

except with interest and

profit; but one will suffice. It is

undoubtedly his most import-

ant; it is also characteristic of the

man and representative of the

high plane upon which he labored.

344

Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

The great purpose of his resolution of

1848, had been fully

accomplished. The further extension of

slavery had been stopped

by the advent of the Republican party to

power, and the system

itself had perished amid the flames of

war. That result had been

sealed by the adoption of the 13th

Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States.

The war was ended. Secession was dead

and all men were

free, but it seemed as though

statesmanship had but reached the

beginning of its troubles.

The changes wrought had given birth to

new and most per-

plexing problems. Were the States that

had been in rebellion in

or out of the Union ? And whether in or

out, how were they to be

restored to their proper statal

relations to the general Government?

Under the Constitution as it existed

before the war, slaves could

not vote, but, in determining the basis

of representation in Congress

and the Electoral College, five slaves

were counted as three voters.

There were no more slaves. They were

freedmen-a new

class. Should they be allowed to vote?

And, if not, should they

be included in the basis of

representation? And, if so included,

should the three-fifths rule continue or

should each man be a unit?

There was grave concern about the

payment of the tremen-

dous national debt that had been

contracted to save the Union and

serious apprehension on the subject of

pensions for our soldiers

and the possible assumption, at some

time in the future, of the

Confederate debt and the payment of

claims for the liberation of

slaves that had been freed.

The peace of the country required a

prompt and final settle-

ment of all these questions.

The policy of Andrew Johnson precluded

any such settle-

ment, for his contention was that the

States were not only inde-

structible, but that in every legal

sense of the word, they were

still in the Union, and that no

legislation of either a constitutional

or a statutory character was necessary

to restore them to their

proper relations to the General

Government.

Without waiting for Congress to take any

action, he pro-

ceeded, by proclamation, to authorize

the organization of pro-

vincial legislatures, and they in turn,

selected United States Sena-

tors and provided for the election of

Representatives in Congress.

John A. Bingham. 345

The extreme danger to which the country

was subjected by

such a policy was forcibly illustrated

when, as a result of it, Alex-

ander H. Stephens, late Vice-President

of the so-called Southern

Confederacy, appeared in Washington at

the opening of Congress

in December, 1865--only a few months

after Appomattox--

with a commission to represent his State

in the Senate of the

United States, and demanded a seat in

that body.

If a full representation of the

rebellious States was thus to

be allowed in the administration of the

Government, the friends

of the Union might speedily lose control

of it, and thus, by ballots,

the forces of secession would be enabled

to accomplish what they

had failed to do with bullets.

It was soon manifest that there could

not be any reconstruc-

tion of the Union without Congressional

action and that to make

the settlement of the war final, it

would be necessary to embody

it in the Constitution itself, where it

would be placed beyond

repeal or modification except by the

sovereign power of the people.

Thus the 14th Amendment became

necessary.

Some of the admirers of Mr. Bingham have

claimed for him

practically all the credit of drafting

that amendment and securing

its adoption. That is more credit than

he is entitled to receive.

The 14th Amendment was, of

itself, a great instrument sec-

ond in importance and dignity to only

the Constitution itself. It

was not struck off in a moment by the

hand of any one man, or

as the product of any one mind. Many men

contributed to it;

many events led up to it.

But while Mr. Bingham is not entitled to

the credit of sole

authorship, he is entitled to the very

high credit of being one of

the very first to recognize its

necessity and to take the initial

steps that ultimately resulted in its

adoption.

He introduced in the House a joint

resolution providing for

such an addition to our organic law. The

record does not dis-

close the exact language he employed,

but enough is given to

show that as to its principal clauses,

his language was practically

the same as that finally adopted.

This is especially true as to the

franchise clause. For this

provision, he is, no doubt, entitled to

more credit than any other

346

Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

man, and that is credit enough, for it

is, indeed, credit of the

highest character.

The record shows, as might be expected,

that other resolu-

tions similar to his and a number of

forms of amendment were

introduced in both the House and the

Senate, and that it was only

after consideration of all, by the

proper committees, that, with

various changes, the amendment was

finally adopted in the con-

solidated form in which it was ratified

by the States.

It was a comprehensive instrument. It

dealt with the public

debt to make it sacred; including

pensions and obligations on

account of bounties to Union soldiers

and provided against all

forms of denial or repudiation.

It prohibited the assumption by the

United States or any

State of any and all debts contracted to

aid the rebellion or for

payment for emancipated slaves.

It fixed the rule of eligibility to hold

office for all who had

taken an oath to support the

Constitution of the United States

and had afterward participated in the

rebellion.

It fixed the basis of representation

according to the number

of authorized voters, but left it

optional with each State to en-

franchise freemen or not; the sole

disadvantage imposed if they

did not, being a corresponding

curtailment of representation or

diminution of political power.

This and the provision defining

citizenship of the United

States were the most important

provisions of the amendment.

All others were temporary in character,

while these were for all

time. These two--citizenship and

suffrage--were the great

crucial points in the settlement of the

differences that had led to

the war and of rights and demands that

had grown out of that

great struggle.

The propriety of defining citizenship of

the United States is

so manifest that it may be dismissed

without comment, other than

that it is a matter of wonderment that

the Constitution, as origin-

ally framed, should have omitted so

important a clause.

The right of suffrage conferred upon the

negro and the basis

of representation established by the

amendment must be con-

sidered together.

John A. Bingham. 347

The old basis of representation was

manifestly no longer ap-

propriate. The slaves were free and must

be treated as free

men. If they were to be counted at all

in determining the basis

of representation, they must be counted

as men and not as chat-

tels. The sole question was whether or

not they should be in-

cluded at all in the enumeration.

The conclusion reached was that they

should not be included

unless given the right of suffrage; and

that this right should be

conferred or not, at the option of each

State.

Such was Mr. Bingham's provision, as

originally proposed

by him, and such was the provision as it

was incorporated into the

amendment as finally ratified and

adopted. This was the sole

requirement as to the Negro imposed by

the Government as a

condition precedent to the resumption by

the rebellious States of

their full relations to the Government.

It left the whole subject of Negro

suffrage in their own

hands, to deal with as they saw fit.

They could give it or with-

hold it. If they saw fit to let the

negroes vote, they could count

them in determining how many

Representatives they should have

in Congress and how many votes they

should have for President

and Vice-President in the electoral

college. If they did not let

them vote, they could not include them

in the basis of repre-

sentation.

That this was a generous proposition and

a fair one to the

South does not admit of argument. It was

prompted by a desire

to speedily restore the Union and was

made in the belief that the

South would show its appreciation for

the spirit of generosity and

good will involved, by a ready and

cheerful acceptance.

This expectation was disappointed.

Emboldened by the attitude of President

Andrew Johnson,

the provisional legislatures he had

called into existence and which

were composed almost entirely of

ex-Confederate officers and

soldiers, rejected the amendment by a

practically unanimous vote

and with evidences of scorn, contempt

and hostility.

They had come to believe that they would

be allowed to re-

sume their relations to the National

Government without any

terms or conditions whatever, as the

President proposed, and

348

Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

that, so restored to all the sovereign

rights of States in the Union,

they would keep themselves free to act

without restraint or re-

striction of any kind.

It quickly developed that they had a

program to practically

nullify emancipation by reducing the

freedman to a worse con-

dition of slavery than that from which

he had been released.

They inaugurated it by acts of

legislation that provided heavy

fines of $50 or $100, and other such

amounts, to be imposed on

all who might be found loitering without

work, and, in default of

payment, hiring them out- selling them -

for six months or a

year, or other period, as the case might

be, to the highest bidder.

The poor Negro, just emancipated, had

neither work nor

money. By refusing him employment, he

was compelled to

"loiter," and having no money

with which to pay his fine, he was

"hired" to the highest bidder,

who had no interest in either his

health or his life beyond the term for

which he was hired.

Truly his last estate was worse than his

first.

Many similar statutes were passed, but

perhaps the most in-

excusable was enacted in Louisiana,

where, among others, it was

provided that every adult freedman

should provide himself with

a comfortable home within twenty days

after the passage of the

act, and, failing to do so, should be

"hired" at public outcry to

the highest bidder for the period of one

year.

Such legislation was barbarous,

inexcusable and intolerable.

It meant that if allowed to have their

own way about it, that

defeated confederates would bring to

naught all that had been

accomplished.

It was, therefore, not a matter of

choice but a matter of com-

pulsion that impelled Congress. It

determined to abolish the

provisional legislatures, divide the

South into military districts,

and organize State governments and

legislatures composed of only

loyal Union men, and then submit anew

the 14th Amendment

for ratification.

This proposition --

the famous Reconstruction Bill - excited

the most bitter, protracted, and the

most important debate that

has ever occurred in the American

Congress.

Mr. Bingham was at the very forefront in

it all. From be-

ginning to end, he was untiring. His

unwavering and masterful

John A. Bingham. 349

support of the measure made him a

conspicuous figure not only

in Congress, but before the whole

nation.

The measure was passed. The Southern

State governments

were reconstructed. The 14th Amendment

was re-submitted,

ratified and adopted.

There has been much angry criticism of

the Republican party

for this procedure, intensified by the

unsatisfactory character of

the carpet-bag State governments and

legislatures - as they were

called at the time -that

were thus temporarily forced upon the

South, but it has been without just

foundation.

The men who were responsible for the

reconstruction meas-

ure and the carpet-bag governments were

the men of the South,

who, misled by President Johnson,

undertook to dictate the man-

ner of restoring the Union, and, in that

behalf, to put in jeopardy

all the results of the war, including

the liberty and freedom of

the unoffending blacks who were, in a

special sense, the helpless

wards of the nation.

It was in the same spirit and for the

same reason that the

15th Amendment followed, providing that

neither the United

States nor any State should deny or

abridge the right of any

citizen of the United States to vote on

account of race, color, or

previous condition of servitude.

Had the 14th Amendment been

adopted when first submitted,

as it should have been, there would not

have been a 15th Amend-

ment, because it would have been

impossible, with the Southern

States restored to the Union, as the

14th Amendment proposed,

thereafter to have secured for a 15th

Amendment a ratification

by three-fourths of the States, and thus

would the whole subject

of Negro suffrage have remained, as was

originally intended.

under the control of the States, with

the option to each State to

grant or refuse it, as it might prefer.

If, therefore, there was fault in

providing for universal man-

hood suffrage, it must be laid at the

door of the men who, reject-

ing the 14th Amendment and

threatening to bring to naught all

the blood and treasure that had been

expended, created a necessity

for the more drastic measures that were

adopted.

But there was no fault.

|

350 Ohio Arch. and His. Society Publications.

Both amendments were right. The perverse blindness and obduracy of the South were but the Providentially designed pre- cipitating causes necessary to excite the men upon whom rested the responsibilities of that hour to the fearless and unflinching performance of the full measure of their duty. To our finite minds, much less good has come from the 15th Amendment than we had a right to expect, but the time is coming when the legal status thus given the black man will be his prac- tically and universally recognized status in all the States of this |

|

Union. |

|

|

|

What is right will ultimately prevail. Until then the irrepressible conflict will continue. Human liberty and human equality involve principles of truth and justice that cannot be forever suppressed and disregarded. Efforts of such character, whether by State or individuals, will but call attention to the wrongs of denial and hasten the day of final triumph. These events mark an epoch in the world's history. The humblest part in such achievements is highly creditable; but to have been a moving and controlling cause and factor, an eloquent, uncompromising, and commanding leader and champion was the high privilege and imperishable honor of John A. Bingham. His work will stand as long as the Republic endures, and through all the years it remains it will bring rich blessings to millions. |

John A. Bingham. 351

His life drew gently to a close. His

noontime was full of

storm and turbulence; his afternoon and

evening full of quiet,

restful peace and beauty.

In Japan, as our Minister, he spent

twelve years of great use-

fulness to his country. He opened the

way for enlarged com-

mercial relations, and by his simple,

straightforward American

manner, impressed a respect and regard

for our civilization, of

which we are now reaping the reward.

Here, in his home, surrounded by family

and friends, his last

days were spent awaiting the summons

that, sooner or later, must

come to all.

This monument attests your esteem, your

admiration, your

love, and your affection for your

neighbor, your townsman, your

friend and your great Representative in

that great crucial time

when our national existence and our free

popular institutions were

put to the sore trial of blood and

relentless civil war.

Through the wisdom and the

statesmanship, of which he was

representative, and also a large part,

we were saved from disso-

lution and made stronger in union than

ever before.

The war with Spain demonstrated how well

the great work

had been done.

From no section came more prompt or more

patriotic response

than from the South. The ex-soldiers of

the Union and the Con-

federate armies and their sons marched

side by side to meet a

common enemy and win a common victory;

and when our late

martyred President, in the midst of his

great work, was struck

down by the assassin, our institutions

sustained the shock without

a jar and the Government moved on

without a tremor, none

mourning his loss to the nation more

than the men who had

periled their lives for the stars and

bars and the cause it repre-

sented.

Such tests as these show us the measure

of our debt to the

men who saved this nation. They were not

alone the gallant

soldiers and sailors who carried our

flag to victory, but also the

men who, standing at the helm, guided

the ship of State.

John A. Bingham. 331

JOHN A. BINGHAM.

ADDRESS OF HON. J. B. FORAKER ON THE

OCCASION OF THE

UNVEILING OF MONUMENT IN HONOR OF HON.

JOHN A.

BINGHAM, AT CADIZ, OHIO, OCTOBER 5,

1901.

Mr. Chairman and Fellow Citizens:

The private life and character of John

A. Bingham were

the special possessions of this

community.

You were his neighbors and friends.

He came and went in your midst.

You were in daily contact with him.

You knew him under all the varying

circumstances of his

long and eventful career.

You saw him tested by the trying

vicissitudes of the tem-

pestuous times with which his most

conspicuous public service

was identified.

You knew better than anybody else can

his private life and

character, and time and again you

honored him with your con-

fidence and attested your high estimate

of his personal worth,

his integrity, and his splendid

qualities of nature and heart.

It would be almost out of place for me

to speak of him on

these points in this presence.

As to his public life, it is different.

It is the common prop-

erty of the whole country -mine as well

as yours. This monu-

ment is in its honor and this occasion

calls for its review.

The first twenty-five years of his life

were spent in prepara-

tion; the last fifteen in retirement.

The other forty-five years that he lived

were devoted almost

exclusively to the public service.

He entered upon his career with a mind

all aflame with zeal

for the great work in which he was to

engage.

He dealt with all the economic questions

of his day-

finance, taxation, national banks, the

tariff, and public improve-

ments; but the subjects with which his

fame is linked were

slavery, secession, rebellion, and

reconstruction.

To intelligently appreciate his work, we

must approach it

as he did.

(614) 297-2300