Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

- 34

- 35

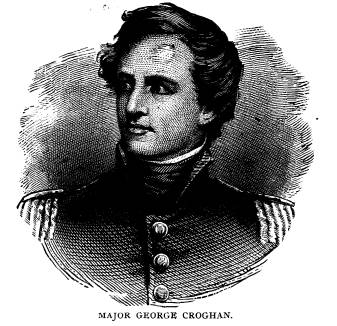

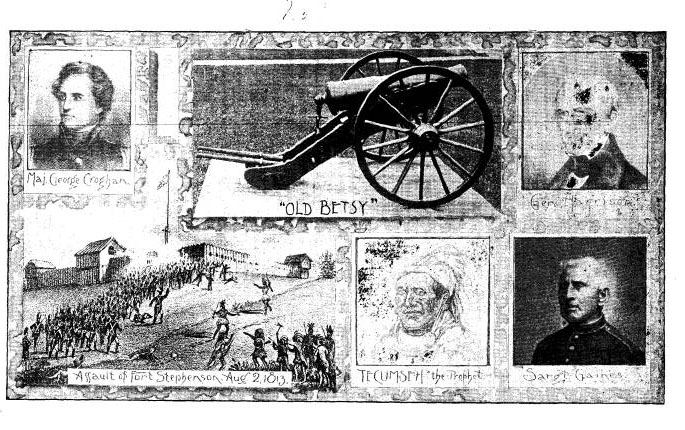

GEORGE CROGHAN.

BY CHARLES RICHARD WILLIAMS, PH. D., LL.

D.

[Address delivered at Spiegel Grove,

Fremont, O., August 1, 1903,

before the George Croghan Chapter

Daughters of the American Revolu-

tion, on the occasion of the celebration

of the ninetieth anniversary of

the battle of Ft. Stephenson. Mr.

Williams is editor of The Indianapolis

News.- E. O. R.]

I.

"Happy the country that has no

history" is an old, old saying.

It falls trippingly on the tongue. It

passes current at unques-

tioned value in the conversation of men.

Hardly ever does one

stop to doubt its validity or to test

its quality. Like most popular

proverbs it does assuredly voice a

common conviction of men;

it does express an accepted opinion.

History busies itself most

with the great concerns of life; with

the emergence and struggle

for recognition of new and strange

forces, with the clash of sys-

tem with system, of class with class,

with the overthrow of gov-

ernments and the setting up of new forms

of polity, with the

disasters of pestilence and earthquake,

of drought and flood, and

with the horrors and glories, the

devastation and triumphs of

marching cohorts and of warring hosts.

When all these things

are absent, when a country's life goes

on unquickened by new

emotions, unstirred by large events,

dull, monotonous, common-

place, it is making no history, and it

may indeed be happy in a life-

less and spiritless sort of way. The

seasons may give their in-

crease, men may have corn in the bin and

cattle in the byre; but

if they have no outlook beyond their own

contracted horizon, if

they have no sense of participation in

the larger life that was

before they began to be and that shall

grow, with their help or

without, into "the fuller

day," what a poor thing their happiness

is!

"Happy the country that has no

history." Yes, if you will.

But happier far the country whose

history is rich, and full and

glorious. We live not only in our day

and in our deeds. But we

live also in the glorious deeds of our

worthy ancestors. They

(375)

|

376 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

sowed and we reap the harvest; they planted, and we enjoy the shade and the fruitage; they builded and we sit in their seats and bask in the flames on their hearthstones; they fought and we share their laurels. All the great deeds done, the sacrifices made, the blood shed and the treasure spent in the making of this America, "to keep the jewel of Liberty in the family of Free- |

|

|

|

dom," give increase of meaning to the words "our country," and make patriotism a more significant and commanding duty. Our country is not just this great expanse of territory, with all its endless variety of scenic charm and climate, of fruitfulness and mineral wealth. It is this, to be sure, but more and better. It is every great name emblazoned on our roster of fame. It is every heroic event that dignifies our annals. It is Washington and Jef- ferson and Hamilton; it is Lincoln and Grant and Hayes. It is Bunker Hill and Princeton and Yorktown; it is Fort Stephenson and Lake Erie and New Orleans; it is Missionary Ridge and Gettysburg and Appomattox. |

George Croghan. 377

II.

The war of 1812 was not a

very important war, and not at

all, as we can clearly see

now, a necessary war. Larger views

and wiser statesmanship would doubtless

have avoided it. There

were grievances, to be sure, that

justified the appeal to arms;

but no more than had existed for years,

and hardly more serious

than those suffered from France. But

France had been friendly

in our Revolutionary struggle, and we

could not quite forget that,

even though Bonaparte was now France and

was seeking to dom-

inate all Europe. And the buffeting of

one's kinsfolk, especially

if they put on "superior" or

patronizing or contemptuous airs,

is always hardest to bear. England had

never quite recognized

that this was really a separate and

distinct member of the family

of nations. That fact produced

increasing bitterness and rage,

particularly among the younger men. And

they, coming into

power at last in the Congress of 1811,

soon forced an unwilling

president to advise and accept war.

Not only was the president really at

heart against the war,

but so were his principal advisers and a

large majority of the

people, especially in the New England

states. Moreover the

country was utterly unprepared for war.

Its navy was insignifi-

cant in number of ships. The army was a

mere handful of

men. Stores and munitions were lacking.

Yet the nation at large

welcomed the declaration of war and

entered upon it with all the

gayety of sublime rashness and buoyant

inexperience.

For the most part the history of the war

is now melancholy

and humiliating reading. Indecision,

vacillation and incompe-

tency at Washington; inexperience,

ignorance, stupidity and even

cowardice among the men placed in

command in the field; sur-

render, defeat, massacres, disgrace -

that pretty nearly sums up

the record of the first few months of

the war on land. Bombas-

tic proclamations of what was going to

be done. Little attempted,

less accomplished. The men in the ranks

and the line officers,

mostly volunteers or militia,

were full of zeal, were eager to fight,

were willing to endure endless hardship;

but they were without

discipline, were ill-equipped, were

badly fed or half-starved, and

the politicians that led them were

neither soldiers nor had the

George Croghan. 379

making of soldiers in them. Things

improved somewhat with

the progress of the war. The

incompetents in high command

on the fighting line were weeded out and

real soldiers took their

places. But apart from the brilliant

work of the little navy, of

Perry on Lake Erie, of McDonough on Lake

Champlain, of many

able captains with cruisers on the

ocean, there were not many

achievements of the war the story of

which sends the blood leap-

ing in pride along your veins. The

instances of bravery or for-

titude of individuals or of

organizations are numerous and thrill-

ing enough, as of course we should

expect of American soldiers-

hardy frontiersmen in large part-and

these give joy and inspira-

tion even while the general narrative of

events on land may be

filling us, after near a hundred years,

with impotent rage at the

blundering stupidity or worse of those

who tried to direct and

to lead.

And yet, badly advised and rash as the

war was, disappoint-

ing and humiliating as was the conduct

of it in so large part,

unsatisfactory or reticent as the treaty

of peace was on the main

issues for which the war was waged, the

final effect of the struggle

on the nation and the people was

doubtless beneficial. It taught

the need of trained soldiers, it made

the navy popular, it gave the

country a standing not before possessed

in the opinions of other

peoples. Just after the announcement of the treaty of peace,

James Monroe, at that time Secretary of

War, as well as of State,

wrote in an official communication to

the Military Committee of

the Senate as follows:

"The late war formed an epoch of a

peculiar character, highly in-

teresting to the United States. It made

trial of the strength and efficiency

of our government for such a crisis. It

had been said that our Union,

and system of government, would not bear

such a trial. The result

has proved the imputation to be entirely

destitute of foundation. The

experiment was made under circumstances

the most unfavorable to the

United States, and the most favorable to

the very powerful nation with

whom we were engaged. The demonstration

is satisfactory that our

Union has gained strength, our troops

honor, and the nation character,

by the contest. * * * By the war we have

acquired a character and

a rank among other nations which we did

not enjoy before." ("Writings

of James Monroe," Vol. V, p. 321.)

380 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

How accurate Monroe's judgment was, is

seen by comparing

with it the summing up of the effect of

the war by our latest his-

torian, President Woodrow Wilson, who

says:

"If the war had done nothing else,

however, it had at least made

the country quick with the spirit of

nationality, and factions were dis-

credited. The War of the Revolution had

needed a war for independence

to supplement it, as Mr. Franklin had

long ago said. Until now, not-

withstanding the separation, English

statesmen had deemed the United

States still in no small degree

dependent upon England for their peace

and privilege in the world, and America

had virtually in their thought

accepted a position of dependence. The

Federalists had been ashamed

of no concession or submission to

England, when once their great leaders

had fallen silent. This clumsy,

foolhardy, hap-hazard war had at any

rate broken their temper. The country

had regained its self-respect. The

government of the Union, moreover, was

once more organized for rational

action. The party which controlled it

had once for all given up the

theories which made it conscientiously

weak and inefficient upon prin-

ciple. It was ready now upon occasion to

raise armies, impose taxes,

avail itself of the services of banks,

and serve the country by means

which should hold the nation united and

self-centered against the world."

For the first year or more of the war

the region about the

head of Lake Erie and Detroit was the

principal center of activity.

The disgraceful surrender of Hull at

Detroit was followed by

disaster after disaster, with little to

cheer the American forces

until the successful resistance by

Harrison of the siege of Fort

Meigs in early May, 1813; and there was

really not much cause

for rejoicing in that when the cost was

counted. Then for nearly

three months little was done but to

maintain and strengthen po-

sitions, while Perry was building his

little fleet at Erie. General

Green Clay was left in command at Ft.

Meigs; Harrison was at

Fort Seneca waiting for reinforcements.

But late in July, Proctor'

the British commander, again appeared

before Ft. Meigs with a

force of regulars, militia and Indians

and sought to draw Clay

into the open. But Clay refused to risk

battle, and Proctor send-

ing his savage allies across country

went by boat around to the

Sandusky river, expecting to reduce Fort

Stephenson and to

press on up the river to attack Harrison

and capture or destroy

his stores. But he counted without his host. By great good

fortune Ft. Stephenson was held by a

young Kentuckian of

twenty-two who had the courage to dare

and who had the power

George Croghan. 381

to inspire his little detachment of one

hundred and sixty men

with the same intrepidity that fired his

purpose. What he and

his determined companions did and how

they did it is all a

familiar story to you. The courageous

defense of Fort Stephen-

son was the first really brilliant event

of the war. Its moral effect

on the country was wholly out of

proportion to its real significance.

It came like a cup of cold spring water

to a man long famishing.

And when it was followed in a few days

by the splendid achieve-

ment of Perry and that by Harrison's

invasion of Canada and

his complete victory in the battle of

the Thames, the country

was delirious with joy and the war in

the Northwest was prac-

tically over.

III.

The defense of Fort Stephenson added to

America's list of

heroes a name that will abide for all

time. What we know of

him before he met his great opportunity

and after that had given

his name to history is all too little.

But here in brief is his story.

On his paternal side George Croghan came

of fighting blood.

He belonged to the race of "the

Kellys, the Burkes and the Sheas,"

who always "smell the battle afar

off." The first Croghan we

we hear of in this country was Major

George Croghan who was

born in Ireland and educated at Dublin

University. Just when he

came to America we do not know. He

established himself near

Harrisburg, and was an Indian trader

there as early as 1746. He

learned the language of the aborigines

and won their confidence.

He served as a captain in Braddock's

expedition in 1755, and in

the defense of the western frontier in

the following year. The

famous Sir William Johnson of New York,

who was so efficient

in dealing with the natives, and whom

George II, had commis-

sioned "Colonel, agent and sole

superintendent of the affairs of

the Six Nations and other northern

Indians," came to recog-

nize Croghan's worth, and made him

deputy Indian agent for

the Pennsylvania and Ohio Indians. In

1763 Sir William sent

him to England to confer with the

ministry in regard to some

Indian boundary line. He traveled widely

through the Indian

country of what is now the central west.

While on a mission

in 1765 to pacify the Illinois Indians

he was attacked, wounded

382

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

and taken to Vincennes. But he was soon

released and accom-

plished his mission. He was deeply

impressed with the great

possibilities of this western country

and urged upon Sir William

Johnson the importance of securing this

region to the English

colonies. In May, 1766 he fixed his

abode near Fort Pitt, using

his good offices and influence in

pacifying the Indians and concili-

ating them to British interests. He died

about 1782. Thus he

lived a busy, useful and public-spirited

life. It is altogether prob-

able that his reports regarding the

Northwestern country had

something to do with impressing George

Rogers Clark with its

importance.

A nephew of this worthy gentleman was

William Croghan,

likewise born in Ireland-in 1752.. Just when he

came to this

country I have been unable to ascertain.

Perhaps it was with his

uncle when he returned after his

official visit to England. At

any rate the young man was well

established here at the time of

the Declaration of Independence. He

promptly volunteered his

services, becoming a captain of a

Virginia company. He served

to the end of the war; being when

mustered out the senior Major

of the Virginia Line. He took part in

the battles of the Brandy-

wine, Monmouth and Germantown; and he

was with the army

that bitter winter at Valley Forge. In

1780 his

regiment was

ordered south and he was made prisoner

at the surrender of

Charleston. He was present at Yorktown,

when the last great

battle of the war was fought, though he

could not share in the

fighting, as he was on parole. He served

for a time on the staff

of Baron Steuben, and he was one of the

officers present at the

Verplanck Mansion on the Hudson in May,

1783, when the So-

ciety of the Cincinnati was instituted.

Shortly after the war

Croghan joined the increasing drift of

Virginians across the

mountains into the new land of Kentucky

and found a home near

the Falls of the Ohio.

There, presumably, he won and wed his

wife. She too came

of valorous stock. Her name was Lucy

Clark, daughter of John

Clark, recently come to Kentucky from

Virginia. She had five

brothers, four of whom served in the

Revolutionary War. The

most distinguished of these was George

Rogers Clark to whose

great and heroic campaign through the

wilderness to Vincennes

George Croghan. 383

we owe the winning of the Northwest

Territory. Another

brother, William, who was too young to

participate in the Revo-

lution, was the Clark who with Captain

Lewis made the famous

expedition of exploration across the

continent. He was appointed

in 1813 by President Madison Governor of

Missouri Territory.

To William Croghan and his wife Lucy at

Locust Grove,

Ky., November 15, 1791 was born the boy

that was destined to

make the family name illustrious. He was

christened George,

perhaps in memory of the father's uncle,

but more likely in honor

of the mother's brother whose great and

daring achievement had

given his name vast renown. We know

practically nothing of

George Croghan's boyhood. Doubtless it

was like that of the or-

dinary Virginia boy of the period, who

was the son of a well-to-do

planter, modified by the exigencies of

frontier life. His grand-

father, John Clark, had large estates in

land and owned many

slaves. On his death in 1799 it was

found that his will named

William Croghan as one of the executors

of his estate. One

clause in the will read as follows:

"Item. I give and bequeath to my son-in-law, William Croghan,

and to his heirs and assigns forever,

one negro woman named Christian;

also all her children together with her

future increase, which negroes are

now in the possession of said

Croghan."

How utterly impossible that sounds to us

to-day. We can

easily imagine what sort of stories, in

the long winter evenings

before the blazing fireplace, quickened

the lad's pulses or sent

him quaking to bed. They were of

instances of thrilling derring-

do against the Red Coats, or of perilous

adventures in the wilder-

ness against savage beasts or still more

savage red men. In the

logs of his grandfather's house, still

standing a few years ago

and perhaps now, and doubtless of many

another, he could see

the bullet marks of Indian marauders.

Through the "long,

long thoughts" and the happy day

dreams of this healthy, hand-

some frontier boy there could not fail

to sound the cruel scream

of rifle and the blood stirring blare of

battle bugles. Of tales of

war and battles, indeed, we are told he

never tired, though hours

passed in the telling. In his school

exercises his selections of

speeches were always of a martial cast;

while he read with

384 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

avidity whatever he could get that told

of war. A word in dis-

respect of Washington would invariably

rouse his boyish indig-

nation.

A highly eulogistic article in the

Portfolio printed in 1815,

written by a man that had been a

school-fellow of Croghan's, gives

us many interesting details of Croghan's

boyhood. The lad's

favorite sports were shooting and

fox-hunting. Often he would

start at midnight or shortly after into

the forest, alone or with

his negro boy attendant, to chase a fox

or to seek other game.

He had the regular schooling of the

young gentlemen of Vir-

ginia of the day, and at seventeen he

was ready for college.

Thereupon (in 1808) he was sent to

Virginia, to the good old

college of William and Mary, where two

years later he was grad-

uated with the degree of Bachelor of

Arts. The subject of his

graduating oration was

"Expatriation," a live topic at that time.

His purpose now was to become a lawyer;

after a course of lec-

tures in law in Virginia he returned to

his home and there con-

tinued his legal studies; keeping up at

the same time his general

reading, particularly in history and

biography. The Portfolio

writer tells us that he greatly admired

Shakespeare and could re-

cite most of the famous passages. Of Croghan's character this

writer says:

"He was remarkable for discretion

and steadiness. His opinions,

when once formed, were maintained with

modest but persevering firm-

ness; and the propriety of his decisions

generally justified the spirit in

which they were defended. Yet, though

rigid to his adherence to prin-

ciples, and in his estimate of what was

right or improper, in cases of

minor importance he was all compliance.

I never met with a youth

who would so cheerfully sacrifice every

personal gratification to the

wishes or accommodation of his friends.

In sickness or disappointment

he evinced a degree of patience and

fortitude which could not have been

exceeded by any veteran in the school of

misfortune or philosophy. Were

I asked what were the most prominent

features of his character (or rather

what were the leading dispositions of

his mind) at the period of which

I am speaking, I would answer, decision

and urbanity-the former re-

sulting from the uncommon and estimable

qualities of his understanding,

the latter, from the concentration of

all the sweet 'charities of life,' in

his heart."

George Croghan. 385

In another paragraph the same writer

adds:

"He is (as his countenance

indicates] rather of a serious cast of

mind; yet no one admires more a pleasant

anecdote or an unaffected

sally of wit. With his friends he is

affable and free from reserve; his

manners are prepossessing; he dislikes

ostentation, and was never heard

to utter a word in praise of

himself."

While this was written by a friend and

at a time when the

country was ringing with the fame of the

young officer - much

as it rang with Hobson's fame after that

daring feat - there is

no reason to doubt its substantial

accuracy. The young law stu-

dent at Louisville in 1811, recently

returned from his Virginia

college, handsome and debonair, busy

with his books and fond

of the chase, sound in principle and

gentle with his friends, must

have been a good man to know and to be

with.

But the law was not long to be Croghan's

mistress. In the

wigwams of Indiana the great chief

Tecumseh was stirring the

hearts of the redmen against the

pioneers. When William Henry

Harrison, Governor of Indiana, learned

that the warriors were

gathering, he prepared to strike, and

there was a call for volun-

teers. Many young men in Kentucky were

quick to respond and

among them was young Croghan, who joined

Harrison's little

army as a private. Before the decisive

battle of Tippecanoe his

handsome appearance and intelligent

discharge of his duties had

attracted the attention of the officers

and he had been made an

aide-de-camp to General Boyd, the second

in command. In the

battle of Tippecanoe he was so zealous,

and displayed such cour-

age, that his fellows said of him he

"was born to be a soldier."

A cant phrase among the soldiers on the

Tippecanoe campaign

was "to do a main business."

During the battle the young Ken-

tuckian rode from post to post cheering

the men and saying:

"Now, my brave fellows, now is the

time to do a main business."

And the result of the battle was such

that there is no doubt they

did it.

After this taste of campaigning Croghan

was eager for the

fray when the prospect of war with Great

Britain became immi-

nent in the spring of 1812. In spite of

his youth, with the recom-

mendations of Generals Harrison and

Boyd, he obtained a cap-

taincy in the Seventeenth United States

infantry regiment. In

August his command was ordered to

accompany the detachment

386 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

under General Winchester, which marched

from Kentucky to the

relief of General Hull at Detroit. But

Hull's disgraceful sur-

render on August 15, followed by the

increased hostility of the

Indians all along the frontier, made a

change of plans neces-

sary. General Winchester marched through

the wilderness to

assist Harrison in the relief of Fort

Wayne, and then down the

Maumee to Fort Defiance which he

occupied late in September.

There he was left in command, by General

Harrison who had

been made Commander of the Northwestern

army, while Harrison,.

returned to the settlements to hurry

forward reinforcements and

supplies. The garrison suffered greatly

from lack of food and

was more than once on the point of

mutiny. Finally in December,.

Winchester was ordered to proceed to the

Rapids, badly equipped

for winter campaigning as his men were.

The expedition, in

which the troops suffered untold

hardship, ended in the disaster

and massacre of the River Raisin. But

Croghan escaped the fate

of others of his regiment by reason of

the fact that he was left

behind in command of the fort. That he

was chosen, after so

short a service, for so responsible a

post proves that he had al-

ready won the confidence of his superior

officers. On the march

he had shown his quality by the skill

with which he selected and

protected his camping places.

Hard upon the unfortunate termination of

Winchester's

movement toward the north, Harrison

began the construction

of a strong fortress at the Rapids. This

was named Ft. Meigs

in honor of the Governor of Ohio. Here,

some time in the spring

of 1813, Croghan joined Harrison. April 28, Proctor

appeared

with a thousand British regulars and

more than that number of

Indians under the great chief Tecumseh.

He had plenty of

artillery and two gunboats; and he sat

down to a regular siege.

The siege failed after lasting for

thirteen days; the cannonading

doing little damage to the fort and

small hurt to the men behind

the ramparts. But for the disaster to

Col. Dudley's detachment

of General Green Clay's Kentucky

brigade, which came to the

rescue of the fort, the defense of Ft.

Meigs would be an alto-

gether pleasant memory. But somebody

blundered or failed to

act at the right moment, and 650 out of

eight hundred were killed,

wounded or taken prisoners. In

connection with Colonel Dudley's.

George Croghan.

387

attack on the batteries across the

river, a sortie was made from the

fort led by Colonel Miller. In this

sortie Captain Croghan dis-

tinguished himself so greatly by the

vigor and bravery of his

assault on a battery, that General

Harrison in his report of the

battle gave him special commendation,

and shortly after he was

promoted to be major.

Then for some weeks Major Croghan was

stationed with his

battalion at Upper Sandusky, where there

were large army stores.

From there he was sent in July to take

command of Ft. Stephen-

son, at Lower Sandusky some forty miles

down the river, which

guarded the approach to Fort Seneca,

where Harrison had his

headquarters. There were reports that

Proctor, who still had con-

trol of the lake and was smarting from

his failure at Ft. Meigs,

was moving again. It was not known where

he would strike; not

unlikely he would seek to capture or to

destroy Harrison's stores.

Ft. Stephenson was a small and wretched

stockade. The works

could scarcely be called a fort. There

were a few wooden

buildings made of thin boards and a

palisade of logs. It had only

one gun, a six -pounder. Moreover

the fort was not well placed,

being commanded by higher ground near

by. Croghan proposed

to Harrison that he be allowed to change

its location, but Harri-

son refused his consent, on the ground

that the enemy was likely

to appear before the work could be

completed. The weakness and

comparative unimportance of the post

were such that Harrison's

instructions to Croghan were that if the

enemy should appear in

force he should destroy the fort and

stores and promptly retreat

to headquarters. But Croghan evidently

had no intention of giv-

ing up easily. He at once began to

strengthen his position and

to prepare for any emergency, working

day and night. About the

stockade he dug a ditch six feet deep

and nine feet wide. To the

top of the palisades he hoisted heavy

logs that could easily be

pushed off to fall with crushing force

on any of the foe that

entered the ditch and attempted to make

a breach. All the stores

at the post were collected in one

building that they might the

more easily be destroyed if necessity

required. The men prepared

an abundant supply of cartridges. Rumors

were thick that the

Indians were on the warpath and that

Proctor who was seeking

4 Vol. XII-4.

388 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

to induce General Green Clay to come out

of Ft. Meigs and fight

in the open, would soon appear. But

Croghan and his 160 men

were getting ready to give him worthy

welcome. In the midst

of this activity Croghan wrote to a

friend as follows:

"The enemy are not far distant. I

expect an attack. I will defend

this post to the last extremity. I have

just sent away the women and

children, with the sick of the garrison,

that I may be able to act with-

out incumbrance. Be satisfied. I shall,

I hope, do my duty. The ex-

ample set me by my Revolutionary kindred

is before me. Let me die

rather than prove unworthy of their

name."

That shows conclusively that he had no

intention of re-

treating unless he was forced to do so.

The evening of July 29, General Harrison

received word

from General Green Clay at Ft. Meigs

that Proctor had aban-

doned his attempt at that point and was

likely to attack Fort

Stephenson. Thereupon, after taking the advice of a council

of officers, Brig.-Generals Lewis Cass

and Duncan McArthur,

Colonels George Paul and James V. Bell

and Majors Wood,

Hukill, Holmes and Graham, he despatched

a messenger to

Croghan directing him at once to set

fire to the fort and to repair

with his command that night to

headquarters. If he thought this

impracticable he was to "take the

road to Huron and pursue it

with the utmost circumspection and

dispatch." As good luck

would have it, the messenger, Mr.

Conger, and his two Indian

guides lost their way, and instead of

reaching Fort Stephenson

that night, they did not arrive till the

next morning at 10 o'clock.

Croghan called his officers together and

they agreed with him

that the fort ought not to be abandoned.

He at once sent the

messenger back with the following

letter:

"SIR:-I have just received yours of

yesterday, 10 o'clock P. M., or-

dering me to destroy this place and make

good my retreat, which was re-

ceived too late to be carried into

execution. We have determined to

maintain this place, and by heavens we

can."

General Harrison was highly displeased

with this letter,

especially with the presumption

displayed in the last sentence,

and immediately he sent Colonel Wells to

relieve Croghan and

ordered him to repair at once to

headquarters. Croghan of

George Croghan. 389

course obeyed; went to Ft. Seneca and

spent the night of July

30th there. We have no record of his

conversation that night

with Harrison, but evidently his

explanations were satisfactory,

for the next morning he was sent back to

Ft. Stephenson to re-

sume command.

Some days after the battle, to combat

criticism of General

Harrison's course at this time, Croghan

wrote a letter in which

he explained that the offensive wording

of his dispatch to Har-

rison was adopted so as to deceive the

enemy, should it fall into

into their hands; and that when

Harrison's delayed order was

received it was thought by him and his

officers that "an attempt

to retreat in the open day, in the face

of a superior force of the

enemy, would be more hazardous than to

remain in the fort, under

all its disadvantages."

But this whole letter reads much like an

explanation after

the event. At any rate, it is difficult

to understand how it would

have been hazardous for the little

garrison to retreat on July 30,

when both that day and the following it

seemed to be perfectly

easy for messengers and horse to move

between Ft. Seneca and

the fort. One finds it by no means easy

to comprehend also why

Harrison did not move forward so as to

be able to lend assistance

or to cover Croghan's

retreat,-especially when the sound of con-

tinuous cannonading must have reached

his ears. But it may be

that he was apprehensive of an attack

from Tecumseh's Indians,

only a portion of whom had been ordered

across country to ope-

rate with Proctor.

In the afternoon of August I, Proctor

with 500 regulars

and 700 or 800 Indians, accompanied by

gunboats, appeared be-

fore Ft. Stephenson. Croghan greeted him

with a few shots

from his single cannon. To the summons

to surrender he gave a

defiant reply; and Proctor began to

bombard the fort. The

firing continued through the night,

which had no rest for the

anxious little garrison. Croghan moved

his one gun about from

point to point in the hope of deceiving

the enemy regarding his

equipment. During the night the British

planted a battery within

250 yards of the stockade. This opened

fire early in the morning

of August 2, but with little effect. In the afternoon Croghan

noticed that the fire from all the

British guns was being concen-

|

390 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

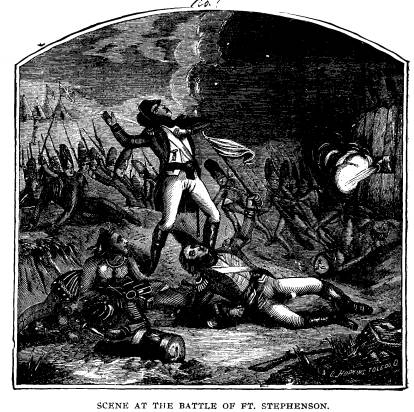

trated on the northwestern angle of the stockade. He inferred that an effort to assault would be made at that point. He there- fore directed that his one gun be lifted up into a blockhouse and so placed as to rake the ditch at that point. The port-hole was masked and the gun loaded with a double charge of leaden slugs. Croghan's inference was correct. The enemy attempted to make |

|

|

|

the assault about five o'clock under cover of the smoke from the battery. They were within twenty paces of the ditch before they were discovered; when they were checked for a moment by fierce musket firing from the fort. But they were quickly rallied by Colonel Short, who, springing over the outer works into the ditch, commanded his men to follow shouting: "Give the damned |

George Croghan. 391

Yankees no quarter." When the ditch was well filled the masked

port-hole was opened and the six-pounder

was fired into the

human mass, only thirty feet away, with

apallingly fatal effect;

while all the time the muskets of the

fort were singing their

deadly song. The British were thrown

into hopeless confusion;

and all that could, fled

precipitately. Their loss was something

like 150, including Col. Short among the

dead. Croghan's loss

was one dead and seven slightly wounded.

That night Proctor

abandoned the field and the campaign and

started back to Canada.

Croghan's official report, written three

days after the battle,

gives a graphic yet modest account of

his great victory. The

report follows:

LOWER SANDUSKY, Aug. 5, 1813.

"DEAR SIR :-I have the honor to

inform you that the combined force

of the enemy, amounting to at least 500

regulars and 700 or 800 Indians,

under the immediate command of Gen.

Proctor, made its appearance before

this place early Sunday evening last,

and so soon as the general had

made such disposition of his troops as

would cut off my retreat, should

I be disposed to make one, he sent Col.

Elliott, accompanied by Major

Chambers, with a flag to demand the

surrender of the fort, as he was

anxious to spare the effusion of blood,

which he probably would not

have in his power to do should he be

reduced to the necessity of taking

the place by storm. My answer to the

summons was that I was determined

to defend the place to the last

extremity, and that no force, however

large, should induce me to surrender it.

"So soon as the flag had returned,

a brisk fire was opened on us

from the gunboats in the river, and from

a 51/2-inch howitzer on shore,

which was kept up with little

intermission throughout the night. At an

early hour next morning, three sixes,

which had been placed during

the night within 250 yards of the

pickets, began playing on us with but

little effect. About 4 P. M. discovering

the fire from all of his guns

was concentrated against the

northwestern angle of the fort, I became

confident that his object was to make a

breach and attempt to storm

the works at that point. I therefore

ordered as many men as could be

employed for the purpose of

strengthening that part; which was so

effectually secured by means of bags of

flour, sand, etc., that the picketing

suffered little or no injury.

Notwithstanding which, the enemy, about

5 o'clock, having formed into close

column, advanced to assault our

works at the expected point, at the same

time making two feints on

the front of Capt. Hunter's lines. The

column which advanced against

the northwestern angle, consisting of

about 350 men, was so completely

enveloped in smoke as not to be

discovered until it had approached

within 15 or 20 paces of the line; but

the men, being all at their post

392 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

and ready to receive it, commenced so

heavy and galling a fire as to

throw the column a little into

confusion. Being quickly rallied, it ad-

vanced to the outer works and began to

leap into the ditch. Just at

that moment a fire of grape was opened

from our 6-pounder, which

had been previously arranged so as to

rake in that direction, which to-

gether with the musketry threw them into

such confusion that they

were compelled to retreat precipitately

to the woods. During the assault,

which lasted half an hour, an incessant

fire was kept up by the enemy's

artillery, which consisted of five

sixes, and a howitzer; but without effect.

My whole loss during the siege was one

killed and seven wounded slightly.

The loss of the enemy, in killed and

wounded and prisoners, must have

been 150. One lieutenant-colonel, one

lieutenant, and 50 rank and file

were found in and about the ditch, dead

or wounded. Those of the re-

mainder who were not able to escape were

taken off during the night by

the Indians. Seventy stands of arms and

several brace of pistols have been

collected near the works. About three

o'clock in the morning the enemy

sailed down the river, leaving behind

them a boat containing clothing and

considerable military stores.

"Too much praise can not be

bestowed upon the officers, the non-

commissioned officers and privates under

my command for their gallant

and good conduct during the siege.

"Yours with respect,

"G. CROGHAN,

"Major Seventeenth U. S.

Infantry, Commanding Lower Sandusky.

"MAJOR GENERAL HARRISON,

Commanding Northwestern Army."

General Harrison in his report to the

Secretary of War paid

high tribute to Croghan's gallantry.

Here is the way he describes

the bloody work done by the young

officer's sole piece of ord-

nance:

"Their troops were formed into two

columns. One led by Lieutenant

Colonel Short, headed the principal one.

He conducted his men to the

brink of the ditch under a galling fire

from the garrison, and leaping

into it was followed by a considerable

number of his own men and the

light infantry. At this moment, a masked

porthole was suddenly opened,

and the 6-pounder, with a half-load of

powder and a double charge of

leaden slugs, at a distance of thirty

feet, poured destruction upon them,

and killed or wounded every man who

entered the ditch. In vain did

the British officers try to lead on the

balance of the column. It retired

under a shower of shot, and sought

safety in the adjoining woods."

The Americans hated Gen. Proctor. His

questionable compact

with the Indians caused them to look on

him as a murderer or

George Croghan. 393

an assassin rather than a soldier. And

it is with evident grati-

fication that General Harrison added to

his report:

"It will not be among the least of

General Proctor's mortifications

to know that he has been baffled by a

youth who has just passed his

twenty-first year. He is, however, a

hero worthy of his gallant uncle,

General G. R. Clark, and I bless my good

fortune in having first in-

troduced this promising shoot of a

distinguished family to the notice

of the Government."

The defense of Fort Stephenson was

hailed as a great vic-

tory by the American people, who had had

so few events to re-

joice over in the conduct of the war. It

was a fit prelude to

Perry's victory on Lake Erie and

Harrison's at the Thames, which

followed soon after. The youth of the

Commander, his refusal

to retreat, the disparity in the number

of men engaged on the

two sides, the freedom from loss- all

combined to give Croghan

peculiar fame. All the papers were full

of his praise. His name

was on all men's tongues, as was Dewey's

after Manila. The

brevet rank of Lieutenant Colonel was

conferred upon him. The

military committee of Congress

recommended a bill providing

him a jeweled sword, but the matter fell

through before the bill

was enacted. The ladies of Chillicothe,

however, presented him

with a sword, and he received a large

number of silken flags from

citizens who rejoiced in his patriotism.

Croghan was in active service during the

rest of the war,

but he did nothing of special

significance. In the summer of

1814 he had command of an expedition

that made a brave attempt

to recapture Michillimackinac, as the

island was then called, but

the attempt was a failure. He was also

engaged in breaking up

British posts on Lake Huron. In all his

operations he was known

for his care of his men. He never

allowed his men to camp with-

out first providing a fortification. He

also showed remarkable

shrewdness in the selection of the camp

sites, and never was his

command surprised.

Croghan remained in the army after the

close of the war,

until March 1817 when he

resigned. In May, 1816, he married

Serena Livingston, daughter of John R.

Livingston, of New

York, and niece of Chancellor Robert

Livingston, famous as

jurist and diplomat, who administered

the oath of office to Wash-

George Croghan. 395

ington, when he first became President

of the United States,

and who as Minister to France negotiated

with Bonaparte the

Louisiana Purchase. Another uncle was

Edward Livingston,

one of the greatest lawyers of his day,

who served his country as

Congressman, Senator and Secretary of

State under Jackson,

whose celebrated Nullification

Proclamation he is believed to have

written. She was a niece also of the

widow of General Mont-

gomery, of Quebec fame.

Of the children of this marriage, one a

daughter, Mrs. Mary

Croghan Wyatt, still lives in New York,

cherishing the mem-

ory of her noble sire; another, a son,

George St. John, by name,

a Confederate officer perished in battle

in West Virginia in the

first year of the Civil War, regretting,

so it is said, that he had

espoused the wrong side. In that battle

the regiment of Colonel

Rutherford B. Hayes took part.

After resigning his commission in the

army, Croghan re-

moved to New Orleans, where his wife's

uncle, Edward Livings-

ton was one of the most prominent

citizens. He was the post-

master of that city in 1824. The

following year he turned to

the army again and was made Inspector

General in the United

States army, with the rank of Colonel.

Then followed long

years of unostentatious service. It is

said that he was on one

occasion about to be courtmartialed for

"intemperance in alco-

holic drinks." Colonel Miller, who himself had won

distinction

in the war of 1812, informed President Jackson of what was

going forward. "The old

general," we are told, "listened impa-

tiently to the information, but heard it

through, and then he laid

down his paper, rose from his chair,

smote the table with his

clenched fist, and, with his proverbial

energy, declared: 'Those

proceedings of the courtmartial shall be

stopped sir, sir! George

Croghan shall get drunk every day of his

life if he wants to, and

by the Eternal the United States shall pay for the whiskey." This

anecdote may not be true but if not it

is well invented. It is a

good companion to the story that Lincoln

asked some preachers

who had come to complain that Grant

drank whiskey whether

they could find out what brand Grant

drank. He wanted to send

some of the same kind to the other

Generals!

|

396 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

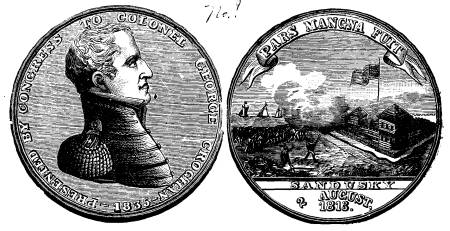

In the Mexican war Col. Croghan again took the field. He joined the army on its march to Monterey, and was present at the assault on that place. During the crisis of one of the three days' fighting, when a Tennessee regiment shook under a tremen- dous concentric fire, Croghan rushed to the front and, taking off his hat, the wind tossing his gray hair, shouted: "Men of Ten- nessee, your fathers conquered with Jackson at New Orleans - follow me!" The stirring words were received with bursts of cheers, and the troops, reanimated, dashed on to victory. By an act of Congress, passed February 13, 1835, Croghan was presented with a gold medal "with suitable emblems and |

|

|

|

devices, in testimony of the high sense entertained by Congress of his gallantry and good conduct in the defense of Fort Ste- phenson, Ohio." After the Mexican war, Col. Croghan was again stationed at New Orleans where he died of cholera, January 8, 1849, ex- piring just as the sound of the last gun fired in celebration of Jackson's victory thirty-four years before, fell upon his ears.

IV. The world is grudging of fame. Of the many battles fought in the war of 1812, with all their deeds of valor and acts of hero- ism, how few there are that this generation knows aught of or |

George Croghan. 397

cares about! Of all the leaders whose

names for the time filled

large space in the thought of the

country how few that we now

recall! The battle of Fort Stephenson

was not a great fight; the

victory in itself was not of large

importance. But the time when

it occurred was fortunate; the manner of

it was such as to touch

the imagination and to thrill the souls

of men; and at once the

deed and the doer were acclaimed and

their fame became sure and

lasting. The names of the brave fellows

that shared in the noble

enterprise have sunk, alas, into

Lethe's dreamless ooze, the common

grave,

Of the unventurous throng.

And there is pathos in that fact; but

such is the universal law

of life.

Whatever 'scaped Oblivion's subtle wrong

Save a few clarion names, or golden

threads of song?

The great multitude of us must be

content to do the work

God gives us to do, unknown and unnoted.

Croghan himself

never rose again to the height of his

one achievement. Perhaps

opportunity was lacking; at any rate

except for his few days at

Fort Stephenson his life was commonplace

and uneventful. But

what of that ? There was that one

glorious day in August, in his

young manhood when opportunity smiled

beckoning, and he

greeted her with bold front and ready

hand. He illustrated the

old, old truth that

One day with life and heart,

Is more than time enough to find a

world.

It is not the intrinsic importance of a

deed always that gives

it value. It is the high and holy

quality of the spirit that con-

ceived and directed its execution. And

this the world is quick

to recognize and appreciate. The race

makes few mistakes in

the men it honors with enduring memory.

To you of Fremont the memory of Fort

Stephenson and the

fame of Croghan are a peculiarly

glorious heritage. It is a great

privilege to live where of old time a

great act was once greatly

done. No one can pass by the site of the

old fort and see the old

six-pounder that spoke to such good

purpose ninety years ago, and

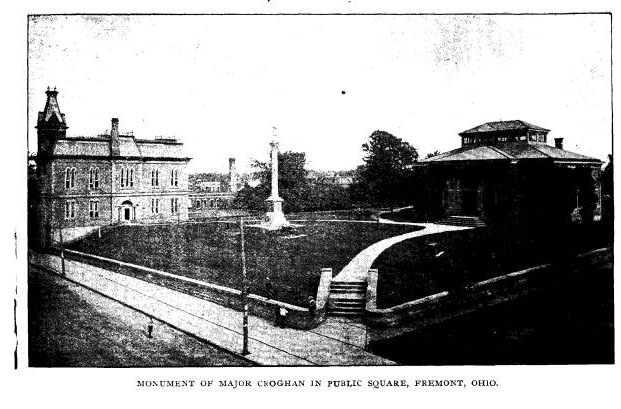

George Croghan. 399

lift his eyes to the shaft that

commemorates the hero of that

far-off fight without a quickening of

his love of country; without

feeling

O Beautiful! my Country! * * *

What words divine of lover or of poet

Could tell our love and make thee know

it,

Among the Nations bright beyond compare?

What were our lives without thee?

What all our lives to save thee?

We reck not what we gave thee;

We will not dare to doubt thee,

But ask whatever else, and we will dare!

LOWER SANDUSKY, 25th July, 1813.

General Harrison:

DEAR SIR:-Mr. Connor has just arrived

with the Indians which

were sent by you to Fort Meigs a few

days since. To him I refer you

for information from that quarter.

I have unloaded the boats which were brought

from Cleveland, and

shall sink them in the middle of the

river (where it is ten feet deep)

about one-half mile above the present

landing. My men are engaged

in making cartridges and will have in a

short time more than sufficient

to answer any ordinary call. I have

collected all the most valuable stores

in one house. Should I be forced to

evacuate the place, they will be

blown up. Yours with respect,

G. CROGHAN,

Major Commanding at Lower Sandusky.

GENERAL HARRISON TO MAJOR CROGHAN.

July 29, 1813.

SIR:-Immediately on receiving this

letter you will abandon Fort

Stephenson, set fire to it and repair

with your command this night to

headquarters. Cross the river and come

up on the opposite side. If you

should deem and find it impracticable to

make good your march to this

place, take the road to Huron and pursue

it with the utmost circum-

spection and dispatch.

400 Ohio Arch. and Hist.

Society Publications.

MAJOR CROGHAN TO GENERAL HARRISON.

July 30, 1813.

SIR:-I have just received yours of

yesterday, 10 o'clock P. M.,

ordering me to destroy this place and

make good my retreat, which

was received too late to be carried into

execution. We have determined

to maintain this place and by Heaven we

can.

July 30, 1813.

To Major Croghan:

SIR:-The General has just received your

letter of this date in--

forming him that you had thought it

proper to disobey the order issued

from this office and delivered to you

this morning. It appears that the

information which dictated this order

was incorrect, and as you did

not receive it in the night, as was

expected, it might have been proper

that you should have reported the

circumstances and your situation be-

fore you proceeded to its execution.

This might have been passed over;

but I am directed to say to you that an

officer who presumes to aver

that he has made his resolution and that

he will act in direct opposi-

tion to the orders of his General,

cannot longer be entrusted with a

separate command. Colonel Wells is sent

to relieve you. You will de-

liver the command to him and repair with

Colonel Ball's squadron to

this place. By

command, etc.,

A. H. HOLMES,

Assistant Adjutant General.

LOWER SANDUSKY, 3d Aug., 1813.

General Harrison!

DEAR SIR:-The enemy made an attempt to

storm us last evening,

but was repulsed with the loss of at

least 200 killed, wounded and pris-

oners. One Lieut.-Colonel (Short), a

major and a lieutenant, with

about forty privates are dead in the

ditch. I have lost but one killed

and but few wounded.

Further statements will be made to you

by the bearer.

GEORGE CROGHAN,

Major Commanding Fort Sandusky.

P. S.-Since writing the above, two

soldiers of the Forty-first Reg-

iment have gotten in who state that the

enemy have retreated - in fact,

one of their gunboats is within three

hundred yards of our works, said

to be loaded with camp equipage, etc.,

which they have in their hurry left.

A true copy. GEORGE CROGHAN.

JOHN 0. FALLEN, Aide-de-Camp.

George Croghan. 401

HEADQUARTERS, SENECA TOWN, 4th August,

1813.

SIR:-In my letter of the first instant,

I did myself the honor to

inform you that one of my scouting

parties had just returned from the

Lake Shore and had discovered the day

before, the enemy in force near

the mouth of the Sandusky Bay. The party

had not passed Lower San-

dusky two hours, before the advance,

consisting of the Indians, appeared

before the Fort, and in half an hour

after a large detachment of British

troops; and in the course of the night

commenced a cannonading against

the fort with three six-pounders and two

howitzers, the latter from gun

boats. The firing was partially answered

by Major George Croghan,

having a six-pounder, the only piece of

artillery.

The fire of the enemy was continued at

intervals during the second

instant until about half past five P.

M., when finding that their cannons

made little impression upon the works

and having discovered my position

here and fearing an attack, an attempt

was made to carry the place by

storm. The troops were formed in two

columns. Lt.-Col. Short headed

the principal one composed of the light

and battalion companies of the

Forty-first Regiment. This gallant

officer conducted his men to the brink

of the ditch under the most galling and

destructive fire from the garrison

and leaping into it was followed by a

considerable part of his own and

the light company. At this moment a

masked port-hole was opened and

a six-pounder with an half load of

powder and a double charge of leaden

slugs at the distance of thirty feet

poured destruction upon them and

killed or wounded nearly every man who

had entered the ditch. In

vain did the British officers exert

themselves to lead on the balance of

the column; it retired in disorder under

a shower of shot from the

fort and sought safety in the adjoining

woods. The other column headed

by the grenadiers who had retired after

having suffered from the muskets

of our men, to an adjacent ravine. In

the course of the night the enemy,

with the aid of their Indians, drew off

the greater part of the wounded

and dead and embarking them in boats

descended the river with the

utmost precipitation. In the course of

the 2d instant, having heard the

cannonading, I made several attempts to

ascertain the force and situa-

tion of the enemy. Our scouts were

unable to get near the fort from

the Indians which surrounded it.

Finding, however, that the enemy had

only light artillery and being well

convinced that it could make little

impression upon the works,

and that any attempt to storm it would be

resisted with effect, I waited for the

arrival of 250 mounted volunteers

which on the evening before had left

Upper Sandusky. But as soon as

I was informed that the enemy were

retreating, I set out with the dra-

goons to endeavor to overtake them,

leaving Generals McArthur and

Cass to follow with all the infantry

(about 700) that could be spared

from the protection of the stores and

sick at this place. I found it

impossible to come up with them. Upon my

arrival at Sandusky I was

informed by the prisoners that the

enemy's forces consisted of 490 reg-

402 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

ular troops, and 500 of Dixon's Indians,

commanded by General Proctor

in person, and that Tecumseh with about

two thousand warriors was

somewhere in the swamps between this and

Fort Meigs, expecting my

advance or that of a convoy of

provisions. As there was no prospect.

of doing anything in front, and being apprehensive that Tecumseh might

destroy the stores and small detachments

in my rear, I sent orders to

General Cass, who commanded the reserve,

to fall back to this place,

and to General McArthur with the front

line, to follow and support him.

I remained at Sandusky till the parties

that were sent out in every

direction returned, - not an enemy was

to be seen.

I am

sorry that I cannot transmit you Major Croghan's official

report. He was to have sent it to me

this morning, but I have just

heard that he was so much exhausted by

thirty-six hours of continued

exertion, as to be unable to make it. It

will not be amongst the least

of General Proctor's mortifications to

find that he has been baffled by

a youth who has just passed his

twenty-first year. He is, however, a

hero worthy of his gallant uncle, Gen.

G. R. Clarke, and I bless my

good fortune in having first introduced

this promising shoot of a dis-

tinguished family to the notice of the

government.

Captain Hunter, of the 17th Regiment,

the second in command, con-

ducted himself with great propriety, and

never were a set of finer young

fellows than the subalterns, viz.:

Lieutenants Johnson and Baylor, of the

17th, and Anthony of the 24th, Meeks of

the Seventh, and Ensigns Shipp

and Duncan of the 17th.

The following account of the unworthy

artifice and conduct of the

enemy will excite your indignation.

Major Chambers was sent by Gen-

eral Proctor, accompanied by Colonel

Elliott, to demand the surrender

of the fort. They were met by Ensign

Shipp. The Major observed that

General Proctor had a number of cannon,

a large body of regular troops,

and so many Indians whom it was

impossible to control, and if the

fort was taken, as it must be, the whole

of the garrison would be mas-

sacred. Mr. Shipp answered that it was

the determination of Major Crog-

han, his officers and his men to defend

the garrison or be buried in it,

and they might do their best. Colonel

Elliott then addressed Ensign

Shipp and said: "You are a fine

young man; I pity your situation; for

God's sake surrender and prevent the

dreadful slaughter that must fol-

low resistance." Shipp turned from

him with indignation, and was im-

mediately taken hold of by an Indian who

attempted to wrest his sword

from him. Elliott pretended to exert

himself to release him, and ex-

pressed great anxiety to get him safe in

the fort.

In a letter I informed you, sir, that

the post of Lower Sandusky

could not be defended against heavy

cannon, and that I had ordered the

Commandant, if he could safely retire

upon the advance of the enemy

to do so after having destroyed the

fort, as there was nothing in it

that could justify the risk of defending

it, commanded as it is by a

hill on the opposite side of the river

within range of cannon and having

George Croghan. 403

on that side old and illy constructed

blockhouses and dry, friable pickets.

The enemy ascending the bay and river

with a fine breeze, gave Major

Croghan so little notice of their

approach that he could not execute the

order for retreating. Luckily they had

no artillery but six pounders and

five and a half inch howitzers.

General Proctor left Malden with the

determination of storming

Fort Meigs. His immense body of troops

were divided into three com-

mands (and must have amounted to a least

five thousand); Dixon

commanded the Mackinaw and other

Northern tribes; Tecumseh,

those of the Wabash, Illinois and St.

Joseph; and Round Head,

a Wyandot chief, the warriors of his own

nation and those of the Ot-

tawas, Chippewas and Pottawattamies of

the Michigan territory. Upon

seeing the formidable preparations to

receive them at Fort Meigs, the

idea of storming was abandoned and the

plan adopted of decoying the

garrison out or inducing me to come to

its relief with a force inadequate

to repel the attack of his immense

hordes of savages. Having waited

several days for the latter, and

practising ineffectually several stratagems

to accomplish the former, provisions

began to be scarce and the Indians

to be dissatisfied. The attack upon

Sandusky was the dernier resort.

The greater part of the Indians refused

to accompany him and returned

to the River Raisin. Tecumseh, with his

command, remained in the

neighborhood of Fort Meigs, sending

parties to all the posts upon

Hull's road, and those of the Auglaize

to search for cattle. Five hun-

dred of the northern Indians under Dixon

attended Proctor. I have sent

a party to the lake to ascertain the

direction that he enemy have taken.

The scouts which have returned saw no

signs of Indians later than those

made in the night of the 2d inst., and a

party has just arrived from

Fort Meigs who made the same report. I

think it probable that they

have all gone off. If so, this mighty

armament, from which so much was

expected by the enemy will return

covered with disgrace and mortifica-

tion. As Captain Perry was nearly ready

to sail from Erie when I

heard from him last, I hope that the

period will soon arrive when we

shall transfer the laboring oar of the

enemy, and oblige him to en-

counter some of the labors and

difficulties which we had undergone in

waging a defensive warfare and

protecting our extensive frontier against

a superior force. I have the honor to

enclose you a copy of the first

note received from Major Croghan. It was

written before day. He

was mistaken as to the number of the

enemy that remained in the ditch;

they amounted to one lieutenant colonel

(by brevet)), one lieutenant and

25 privates; the number of prisoners to

one sergeant and 25 privates,

fourteen of them badly wounded. Every care has been taken of the

latter and the officers buried with the

honors due to the rank and their

bravery. All the dead that were not in

the ditch were taken off in the

night by the Indians. It is impossible

from the circumstances of the

attack that they should have lost less

than one hundred; some of the

5 Vol. XII-4.

404 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

prisoners think that it amounted to two

hundred. A young gentleman,

a private in Petersburg volunteers, of

the name of Brown, assisted by

five or six of that company and the

Pittsburg Blues, who were acci-

dentally in the fort, managed the

six-pounder which produced such de-

struction in the ranks of the enemy.

I have the honor to be, with great

respect, sir,

Your obedient servant,

WILLIAM HENRY HARRISON.

N. B.-Of our few wounded men there is

but one that will not be

well in less than six days.

HEADQUARTERS SENECA TOWN

5TH AUGUST, 1813, 6 O'CLOCK A. M.

SIRS-I have the honor to enclose you

Major Croghan's report of

the attack upon his post, which has this

moment come to hand. For-

tunately the mail has not closed.

With great respect I have the honor to

be sir,

Your humble servant,

WILLIAM HENRY HARRISON.

P. S.-The new ship was launched at

Malden on the 17th ult. I

have apprised Commodore Perry of it.

Hon. General Armstrong, Sec'y of War.

LOWER SANDUSKY, AUGUST 5, 1813.

DEAR SIR:-I have the honor to inform you

that the combined force

of the enemy amounting to at least 500

regulars and seven or eight hun-

dred Indians under the immediate command

of General Proctor, made its

appearance before this place early on

Sunday evening last; and so soon

as the General had made such disposition

of his troops as would cut off

my retreat, should I be disposed to make

one, he sent Colonel Elliott,

accompanied by Major Chambers, with a

flag to demand the surrender

of the fort as he was anxious to spare

the effusion of blood which he

should probably not have in his power to

do should be he reduced to the

necessity of taking the place by storm.

My answer to the summons was that I was

determined to defend the

place to the last extremity and that no

force however large, should in-

duce me to surrender it. So soon as the

flag was returned a brisk fire

was opened upon us from the gun boats in

the river and from a five and

one-half inch howitzer on shore, which

was kept up with little inter-

mission throughout the night. At an

early hour the next morning, three

sizes (which had been placed during the

night within 250 yards of the

George Croghan. 405

pickets) began to play upon us but with

little effect. About 4 P. M.,

discovering that the fire from all his

guns was concentrated against the

northwestern angle of the fort, I became

confident that his object was to

storm the works at that point. I

therefore ordered out as many men as

could be employed for the purpose of

strengthening that part which was

so effectually secured by means of bags

of flour, sand, etc., that the pick-

eting suffered little or no injury,

notwithstanding which the enemy, about

500, having formed in close column,

advanced to assault our works at

the expected point, at the same time

making two feints on the front of

Captain Hunter's lines. The column which

advanced against the north-

western angle consisting of about 350

men was so completely enveloped

in smoke as not to be discovered until

it had approached within fifteen

or twenty paces of the lines, but the

men being all at their posts and

ready to receive it, commenced so heavy

and galling a fire as to throw the

column into a little confusion. Being

quickly rallied it advanced to the

center works and began to leap into the

ditch. Just at that moment a

fire of grape was opened from our

six-pounder (which had been pre-

viously arranged so as to rake in that

direction) which together with

the musketry, threw them into such

confusion that they were compelled

to retire precipitately into the woods.

During the assault which lasted

about half an hour, an incessant fire

was kept up by the enemy's artil-

lery (which consisted of five sixes and

a howitzer) but without effect.

My whole loss during the seige was one

killed and seven slightly

wounded. The loss of the enemy in

killed, wounded and prisoners must

exceed one hundred and fifty. One Lt.

col., a Lt. and fifty rank and file

were found in and about the ditch, dead

or wounded. Those of the re-

mainder who were not able to escape,

were taken off during the night by

the Indians. Seventy stand of arms and

several brace of pistols have

been collected near the works. About

three in the morning the enemy

sailed down the river leaving behind them a boat containing considerable

military stores.

Too much praise cannot be bestowed upon

the officers, non-commis-

sioned officers and privates under my

command for their gallantry and

good conduct during the siege.

Yours with respect,

G. CROGHAN,

Major 17th U. S. Inf., Commanding

Lower Sandusky.

Major General Harrison, Commanding

Northwestern Army.

LOWER SANDUSKY, AUGUST 27, 1813.

I have with much regret seen in some of

the public prints such mis-

representations concerning my refusal to

evacuate this post, as are cal-

culated not only to injure me in the

estimation of military men, but also

406 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

to excite unfavorable impressions as to

the propriety of General Harri-

son's conduct relative to this affair.

His character as a military man is too

well established to need my

approbation or support, but his public

services entitle him at least to

common justice. This affair does not

furnish cause of reproach. If pub-

lic opinion has been lately misled

respecting his late conduct, it will re-

quire but a moment's cool, dispassionate

reflection to convince them of its

propriety. The measures recently adopted

by him, so far from deserving

censure, are the clearest proofs of his

keen penetration and able general-

ship. It is true that I did not proceed

immediately to execute his order

to evacuate this post, but this

disobedience was not as some would wish

to believe, the result of a fixed

determination to maintain the post con-

trary to his most positive orders, as

will appear from the following detail,

which is given in explanation of my

conduct:

About ten o'clock on the morning of the

30th ult. a letter from the

Adjutant General's office dated Seneca

Town, July 29, 1813, was handed

me by Mr. Connor, ordering me to abandon

this post, burn it and retreat

that night to headquarters. On the

reception of this order of the general

I called a council of officers, in which

it was determined not to abandon

the place until the further pleasure of

the General should be known, as

it was thought an attempt to retreat in

the open day, in the face of a

superior force of the enemy would be

more hazardous than to remain in

the fort, under all its disadvantages. I

therefore wrote a letter to the

General Council in such terms as I

thought were calculated to deceive

the enemy should it fall into his hands,

which I thought more than prob-

able, as well as to inform the General

should it be so fortunate as to

reach him that I would wait to hear from

him before I should proceed

to execute his order. The letter,

contrary to my expectations was re-

ceived by the General, who, not knowing

what reasons urged me to write

in a tone so decisive, concluded very

rationally that the manner of it was

demonstrative of the most positive

determination to disobey his orders

under any circumstances. I was therefore

suspended from the command

of the fort and ordered to headquarters.

But on explaining to the Gen-

eral my reason for not executing his

orders, and my object in using the

style I had done, he was so perfectly

satisfied with the explanation that

I was immediately reinstated in the

command.

It will be recollected that the above

order alluded to was written on

the night previous to my receiving it.

Had it been delivered to me as

was intended that night, I should have

obeyed it without hesitating. Its

not reaching me in time was the only

reason which induced me to con-

sult my officers on the propriety of

waiting the General's further orders.

It has been stated, also, that

"upon my representations of my ability

to maintain the post the General altered

his determination to abandon it."

This is incorrect. No such

representation was ever made. And the last

order I received from the General was

precisely the same as that first

given, viz: "That if I discovered

the approach of a large British force

George Croghan. 407

by water, (presuming that they would