Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

|

THE LOUISIANA PURCHASE.

E. 0. RANDALL. In that striking and stirring century known as the sixteenth, began the voyages of discovery and the expeditions for occupancy, |

|

|

by the Anglo Saxon and the Gaul, of the North American continent. The French were led by Jacques Cartier, who in 1534 entered the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Other chivalrous and adventurous Frenchmen followed with various experiences, until 1608, when Sam- uel Champlain encamped upon the Heights of Quebec, and estab- lished a colony on that famous Canadian site. With equal energy and dar- ing the Englishman, the inveter- ate rival of the Frenchman, was slowly but surely getting a firm |

|

foothold on the American shore. In the year 1498, more than a third of a century before Cartier's little vessel plowed her way up the St. Lawrence, and before Columbus had made his last voy- age, the Cabots, John and Sebastian, father and son, coasted along the continent of North America and claimed it by dis- covery. In 1607 the Jamestown (Virginia) colony became the first permanent English settlement in America. In 1666 Rob- ert Cavalier Sieur de La Salle sailed up the St. Lawrence, trav- ersed the Great Lakes, and in 1682 descended the Mississippi to its mouth and gave the name Louisiana, in honor of his sav- creign Louis XIV., to the vast region comprising the basin of the great "Father of Waters," and took possession of a great undefined territory in the name of France. Meanwhile the 248 |

The Louisiana Purchase. 249

British settlers were establishing New

England colonies along

the Atlantic coast. The charters and

patents of these English

colonies granted by the English

sovereigns gave the colonists not

only the land bordering on the Atlantic

coast, but also its ex-

tension west as far as the land might

reach. Both France and

England therefore claimed much of the

same territory, the great

triangle formed by the Mississippi river

on the west, the Atlantic

coast on the east, the Great Lakes on

the north, and the Gulf

of Mexico on the south. The contest

between the two racial

rivals culminated in the dramatic battle

on the Heights of Abra-

ham in 1759, when the invincible English

forces under Wolfe

overcame the intrepid French army under

Montcalm, both lead-

ers bravely sacrificing their lives in

the bloody encounter.

As a result of the English victory, by

the treaty of Paris

(1763), France yielded all her

possessions on the American con-

tinent. She ceded to England, Canada and

all her claimed do-

monion east of the Mississippi and south

of the Great Lakes, but at

the same time transferred to Spain, for

her friendly alliance and

other considerations, the country west

of the Mississippi, includ-

ing the portion at its mouth known as

New Orleans. The French

settlement of New Orleans was founded in

1718 by Bienville

(Jean Baptiste La Moyne). It became the

French metropolis of

the south as Quebec was of the north.

The Spaniards were slow

in taking possession of their new

American acquisition, leaving

the French administration undisturbed

for more than five years.

Not until 1768, while the French

colonists were still objecting to

their transfer from France to Spain, did

the Spanish governor

appear. This gentleman was Antonio

D'Ulloa, who was suc-

ceeded by Count Alexander O'Reilly, Don

Louis Unzaga, Ber-

nado de Galvez, Estevan de Miro, Baron

de Carondelet, Manuel

Gayoso de Lemos, Marquis de Casa Calvo,

and Don Juan de

Salcedo. These governors were a

picturesque, gay, rollicking,

and more or less efficient and sometimes

oppressive set of rulers,

who failed however to reconcile the

French inhabitants to Span-

ish allegiance. Under their

administrations a numerous con-

tingent of Spanish emigrants settled in

the territory of Louisiana,

more particularly in the city of New

Orleans.

France never ceased to regret that she

had parted with her

250 Ohio Arch. and Hist.

Society Publications.

Louisiana possessions, and several times

her government contem

plated plans peaceable or otherwise for

its recovery. Thus matters

stood until "the sublime

rogue," Napoleon, emerged from the

upheaval of the French Revolution. The

victory at Marengo

(June, 1800) of the invincible Corsican,

then posing as First

Consul, aroused his ambition for

illimitable territory. He cov-

eted not only power in the Orient, but

looked longingly to the

Spanish possessions in America. In his

rapid European con-

quests Spain became hopelessly dependent

upon France, the

Spanish king falling into impotent

subserviency to Napoleon.

Within six weeks after his Marengo

victory, Bonaparte set his

agents at Madrid busy with the idea of

bringing about the retro-

cession of Louisiana to France. A

glorious New France was to

be built up beyond the sea, and for

three years the First Consul

pursued the scheme with ardor. Berthier,

the instrument of

Bonaparte, became Minister at Madrid,

and under his direction

the form of a treaty (August, 1800) grew

definite. France was

to have Louisiana and also the two

Floridas, while the considera-

tion to Spain was to be a kingdom of at

least a million people

made up of French conquests in the north

of Italy, over which

was to be set the Duke of Parma, husband

of the Infanta, daugh-

ter of Charles IV., nominal king of

Spain. This treaty, nego-

tiated by Berthier, dated October 1,

1800, Mr. John Adams pro-

nounced one of the most interesting

documents in the history of

the United States, for it is the source

of our subsequent title to

Louisiana; indeed all sequential

arrangements were but modifica-

tions of that treaty. Charles IV.

refused the surrender of the

two Floridas, but was persuaded to yield

Louisiana because Na-

poleon demanded it, and he (Carlos)

would receive in return a

royal province (Tuscany) for his

daughter and son-in-law. It

was a good real estate trade. Early in 1800 Lucien

Bonaparte,

brother of Napoleon, succeeded Berthier

as the French manager

of affairs at Madrid. Lucien Banaparte

proceeded (March 21,

1801) without delay to negotiate at San

Ildefonso, the then res-

idence of the Spanish court, a new

treaty which did little more

than define and confirm that of the

preceding October. In re-

turn for the elevation of the Duke of

Parma to the sovereignty

of Tuscany the retrocession of Louisiana

to France was to be

The Louisiana Purchase. 251

at once consummated. The king of Spain,

however, at the last

moment balked and refused to sign the

treaty, and it could not

be fully effective without his

signature. In the fall of 1801 came

peace between France and England, and

the First Consul was

free, as he had not been before, to

pursue his great schemes for

internal improvements, and colonial

accessions. Napoleon, with

characteristic impatience and exercise

of powers of appropria-

tion, wrote (July, 1802) to his

Minister of Marine, Decres, "My

intention is to take possession of

Louisiana in the shortest time

possible." He then summarily

proceeded to organize an expe-

dition for the forcible occupation of

Louisiana. There was as-

sembled at Dunkirk a sufficient army of

infantry and artillery

which was to be sent in transports to

the mouth of the Missis-

sippi and take things. To the command of

this expedition Bona-

parte at first named Bernadotte, but the

storm of a European war

suddenly threatened and gave Napoleon

pause. Bernadotte

would be needed at home, and General

Claude Perrin Victor was

placed in command of the American

squadron. But before the

fleet could get under way, King Carlos

yielded, and signed the

treaty of retrocession upon the

conditions: first, that the new

kingdom of Etruria, as the Italian

appanage of the Infanta and

her husband was to be called, must be

distinctly recognized by

Austria, England, and the dethroned Duke

(Ferdinand) of Tus-

cany, whose lost territory was

incorporated in the new domain;

second, France must pledge herself not

to alienate Louisiana, and

to restore it to Spain in case his

son-in-law, the king of Etruria

to be, should lose his power. Carlos

proposed to have the bar-

gain fixed to stick.

At this point the United States began to

take a hand in the

transaction. John Adams, who as the head

of the Federalists,

leaned strongly toward England, and

nearly involved the United

States in a war with the French

Directory, was succeeded in the

presidency March 4, 1801, by Thomas

Jefferson, the Anti-feder-

alist. The new president entertained a

favorable disposition not

only toward France but also toward her

ally Spain. As the situ-

ation in Europe over the proposed

retrocession of Louisiana be-

came known to the Americans, it became a

question of great

national interest and importance. It

assumed a political issue.

252 Ohio

Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

New Orleans was the commercial gate and

outlet of the Missis-

sippi, which was the natural highway of

traffic for hundreds of

miles into the interior of the great

West. The right to traverse

unimpeded that water-course, unload and

deposit goods at New

Orleans, and there sell and re-ship to

the other ports, was a mat-

ter of vital importance to the people of

the young American Re-

public. Under Spanish rule this right

had been granted only

under severe restrictions of custom

duties. Efforts had been

made to secure by treaty with Spain

greater privileges of naviga-

tion of the river and re-shipment at New

Orleans. The duties

had been excessive till 1795, when a

treaty was secured "to make

use of the port of New Orleans as a

place of deposit for their

(American) produce and merchandise and

to export the same

free from all duty or charge except for

storage and incidental

expenses." The transfer of Louisiana and New Orleans to

France imperilled this prized and

priceless privilege. American

western commerce would be at the mercy

of France, the stability

of whose government was uncertain, and

with which nation the

relations of the United States would be

problematical. Pending

the negotiations between Spain and

France, the Spanish civil

officer at New Orleans (1802) abrogated the

"right of deposit,"

closing absolutely the Mississippi to

the United States. The

people of the West and South were

hostile to the Spanish occu-

pation of Louisiana. It ought to be

American territory. Its sale

now to France by Spain heightened this

anti-foreign feeling. It

would only confirm its alienation to

non-American possessors.

France could, and probably would,

control the situation with a

despotic hand. The people of the West

and South, being those

most closely and materially interested,

opposed the transfer to

France, and excitement ran so high that

it was suggested an

armed organization of western Americans

proceed to New Or-

leans and attempt its seizure at the

first sign of the French ad-

vance. The people of the East and North,

being farther removed

from the section affected, and having

the Atlantic seaboard as a

maritime outlet, were less agitated over

the situation. But a

war with France was not improbable. Jefferson was in hot

water. He decided to solve the

difficulty by buying New Orleans

The Louisiana Purchase. 253

and Florida.* Jefferson appointed James

Monroe an envoy extraor-

dinary to France to negotiate jointly

with Livingston, for the ces-

sion of New Orleans and Florida to the

United States. He was

authorized to expend, if need be, a sum

of $2,000,000 for the pur-

pose. If no purchase could be effected,

then Monroe was at least

to secure the old "right of

deposit" at New Orleans. Monroe

sailed March 8, 1803. Pierre

Clement Laussat, the colonial pre-

fect, had meantime been placed by

Napoleon in charge of the

French fleet to be sent to America to

take possession of New

Orleans as the practical capital of

Louisiana. Napoleon feared,

with good cause, that England, knowing

the situation, would

despatch vessels to New Orleans and

secure possession before the

French fleet could arrive. When Monroe

reached Paris he found

Napoleon in hot water. His dream of a

colossal and colonial em-

pire was growing dim. His Egyptian

campaign had failed. His

San Domingo campaign was a frightful

nightmare. The Eu-

ropean powers were gathering for a

combine against him. Eng-

land was preparing for the great

struggle. Napoleon needed

money and needed it bad. He caught at

the idea of selling

Louisiana. It would replenish his

coffers and strengthen the

United States as against England his

most dreaded foe. Rob-

ert Livingston was the American Minister

to France. He had

seen the advantage of this purchase and

advocated it to Jefferson

and to Bonaparte.

* Florida discovered in 1512 by Ponce de

Leon and claimed for

Spain. The domain of Florida under

Spanish occupancy extended in

definitely westward and included the

southern extremity of Louisiana.

Early in the 18th century the English in

the Carolinas and Georgia

made war on the Floridans. By the treaty

of Paris (1763) Florida

was ceded by Spain to England in

exchange for Cuba which had been

conquered by England in 1762. The

English divided Florida into East

and West Florida, the Appalachicola

River being the boundary line. By

the treaty resulting from the American

Revolution (1783), Florida was

retroceded to Spain, and the western

boundary fixed at the Perdido

River. When in 1803 Louisiana was ceded

to the United States by

France, its domain was regarded as that

which it had been in the hands

of Spain when ceded by that country to

France. The United States

therefore claimed the country west of

the Perdido River and in 1811

took possession of the same. Finally

Florida (east of the Perdido) was

purchased from Spain in 1819 and

American possession was taken in 1821.

|

254 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

Napoleon, rather than trust the wily Talleyrand in the mat- ter, made the Marquis de Barbe-Marbois, minister of the Treas- ury, his agent in the negotia- |

|

|

tions. Barbe-Marbois had been consul general to the United States and his wife was an American. Napoleon grew more and more anxious to sell as war between France and England became more immi- nent. He proposed to destroy England's chance of further ac- quisition in America. He said to his ministers that, "to free the world from the commercial tyranny of England it is neces- sary to oppose to her a maritime power which will one day be- |

|

come her rival. It must be the United States. The English as- pire to dispose of all the riches of the world. I shall be useful to the entire universe if I can prevent them from dominating Amer- ica as they dominate Asia. * * * * The English shall not have the Mississippi, which they covet. Louisiana is nothing in comparison with their aggrandizement in all parts of the globe; but the jealousy they feel because of its return under the domin- ion of France warns me that they intend to seize it, and it is thus they will begin the war. They have already twenty vessels in the Gulf of Mexico. The conquest of Louisiana will be easy if they will only take the trouble to descend upon it. I have not a moment to lose in putting it out of their power. I do not know but what they are already there. That is their usual way of doing things: and as for me, if I were in their place, I certainly would not have waited. I wish to take away from them even the idea that they will ever be able to own this colony. I contem- plate turning it over to the United States. I should hardly be able to say I had ceded it to them, for we are not yet in possession of it. But even a short delay may leave me nothing but a vain title to transmit to these Republicans, whose friendship I seek. |

The Louisiana Purchase. 255

They are asking me for but a single city

of Louisiana (New Or-

leans) but I already regard the whole

colony as lost, and it seems

to me that in the hands of this rising

power it will be more use-

ful to the politics and even to the

commerce of France than if I

attempt to keep it."

On April 12, (1803) Monroe reached Paris and

joined Liv-

ingston. Conferences between the

American envoys and the

French authorities were fraught with

difficulties. Jefferson's

representatives were uncertain of their

powers. The negotiators

for Napoleon were hampered by his

vacillating dictation and his

frequent change in the price demanded,

first asking 50,000,000

francs and then rising to one hundred

million. The compact of

sale was finally signed April 30, 1803,

by the agents of the two

nations: Robert R. Livingston and James

Monroe for the United

States and Barbe-Marbois for France.

Said Marbois: "As

soon as they had signed they rose, shook

hands, and Livingston,

expressing the satisfaction of all,

said: 'The treaty we have

signed has not been brought about by

finesse nor dictated by

force. Equally advantageous to both the

contracting parties, it

will change vast solitudes into a

flourishing country. To-day the

United States take their place among the

powers of the first rank.

Moreover, if wars are inevitable, France

will have in the new

world a friend increasing year by year

in power, which can not

fail to become puissant and respected on

all the seas of the earth.

These treaties will become a guarantee

of peace and good-will

between commercial states. The

instrument we have signed will

cause no tears to flow. It will prepare

centuries of happiness for

innumerable generations of the human

race. The Mississippi

and the Missouri will see them prosper

and increase in the midst

of equality, under just laws, freed from

the errors of supersti-

tion, from the scourges of bad

government, and truly worthy

of the regard and the care of

Providence.'"

Napoleon, when he signed the treaties

declared that this ac-

cession of territory which he had

bestowed "assures forever the

power of the United States, and I have

given England a rival

who, sooner or later, will humble her

pride." It was an anoma-

lous proceeding by both parties. In this

transaction Napoleon

conducted himself with his

characteristic high-handed, lawless

256 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

and autocratic manner. He acted

independent of his advisors,

of his Parliament, the wishes of his

people, with whom the sale

was unpopular, and in defiance of the

conditions under which he

had bought it from Spain, viz., that it

be not parted with by

France without consent of Spain. On the

other hand Livingston

and Monroe were only authorized to buy

the island of New Or-

leans, and expend therefor two million

dollars. So that the peo-

ple of the United States had obtained to

their surprise a territo-

rial acquisition which they had not

asked and indeed which they

were in doubt about desiring. When the

extent of the purchase

was known Jefferson was greatly

embarrassed and the citizens

of the country were not a little amazed.

Both president Jefferson

and secretary of state Madison

"were dazed at the audacity of

their agents, the immensity of the sum

paid and the enormous

magnitude of the whole

transaction." Mr. Jefferson at first de-

clared he would not approve the treaty,

because, if he did, he

would make "waste paper of the

constitution." He had long

been teaching that "the strict

construction of the constitution per-

mitted nothing to be done under it

except what was expressly au-

thorized. There was hence no authority

in express terms for the

nation to grow in size, to enlarge its

boundaries, to add new terri-

tories. Ohio had been admitted into the

Union that very year (1803)

with his approval, but this was carved

out of an acquisition gained

by another peaceful or peace treaty-with

England-made before

the constitution became operative. The

supreme organic law, ac-

cording to this literal expounder,

hindered growth, development,

progress, expansion." But while the

president was halting over

constitutional questions, Napoleon was

catching his breath,

through a lull in the war business, and

beginning to repent of his

disposal of Louisiana. He began

searching for technical loop-

holes in the contract of sale whereby he

might rescind his agree-

ment. He even instructed Marbois to find

a pretext for re-

pudiating what he concluded was a bad

bargain for France.

Livingston becoming alarmed at the

situation urged Jefferson to

clinch the matter before too late. The

president was persuaded

that constitutional quibbles must be

ignored, and on October 17

(1803) called a special session of

congress, and two days later the

The Louisiana Purchase. 257

Senate ratified the treaty of purchase.

The bargain was closed.

Louisiana was ours. The price paid was

eighty million francs,

or something over fifteen million

dollars. But of this amount,

the United States in its payment to

France was to deduct twenty

million francs and in lieu thereof pay

that sum to the American

citizens in settlement of the spoliation

claims which they had

against France.* Congress proceeded to

provide for a provisional

government for the newly acquired

territory, and also for ways

and means to raise the money to pay the

purchase price.

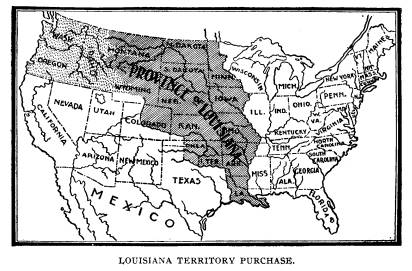

In all this while in these various sales

and barters, as Mr.

Hosmer notes, no human being possessed

any definite idea of the

extent or the boundaries of the

territory called Louisiana. In the

last transfer between Jefferson and

Napoleon, the indefiniteness

was as great as ever. In the language of

the treaty the cession

was to be of the "province of

Louisiana with the same extent it

now has in the hands of Spain, and that

it had when France

possessed it." On the north

Louisiana was understood to go to

the sources of the Mississippi, but

those were not then ascer-

tained; on the northwest to the

mountains, which no explorer

had yet been known to traverse. The

southern boundary was cer-

tainly the Gulf-that was, perhaps, the

only thing fixed in all

the province save the Mississippi, which

in its upper course fixed

the limit on the east; but on the

southeast the uncertainty also

prevailed for this pertained to the

territory known as the Floridas.

"The territory, however, when made

definite was discovered to

be in extent more than seven times that

of Great Britain and

Ireland; more than four times that of

the German empire, or

of the Austrian empire, or of France;

more than three times that

of Spain and Portugal; more than seven

times that of Italy;

nearly ten times that of Turkey and

Greece. It is also larger than

* By amount of claim on Government of

France, admitted by said

Government as due to citizens of the

United States, and which, pursuant

to the provisions of the Louisiana

Convention of April 30th, 1803, were

payable by bills drawn by said minister

(John Armstrong) on the treas-

ury of the United States, including

sundry embargo cases, as per list

certified by the minister of the French

treasury, etc., 19,609,839.63 francs,

at rate of five and one-third francs to

the dollar, or $3,692,055.69.

American State Papers vol. 8, Finance

vol. II, page 561.

17 Vol. XIII

258 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

Great Britain, Germany, France, Spain,

Portugal, and Italy com-

bined."*

The close of the year 1803 witnessed the

dramatic scenes that

sealed the series of events in the

negotiations. The stage of this

final act was the cosmopolitan city of

New Orleans, the Spanish,

French, and American officials vieing

with each other to render

brilliant and impressive the parts

played by their respective na-

tions. The news of the proceedings at

Paris, in those days, was slow

in reaching the people of the United

States, and especially those

most interested at the distant port of

New Orleans. Pierre Cle-

ment Laussat had arrived (September,

1803) in the capital city

of the Louisiana district to make the

announcement to its people

of the re-purchase by France from Spain

of the Louisiana coun-

try, and upon him devolved the delicate

mission of announcing to

the Spaniards living in that colony that

they had now become the

subjects of the French republic, at

whose head was the daring

first consul. But as General Victor was

alone authorized by

Napoleon to receive the colony from the

Spanish government, the

colonial prefect, Laussat, found his

office informal and chiefly

ornamental. The news of the

re-annexation of New Orleans and

its province to France was welcomed by

the French of the city

with the wildest excitement and

rejoicing. Five weeks after

Laussat's arrival Marquis De Cassa Calvo

landed in the city,

sent by the Captain General of Cuba to

act with the Spanish

Governor Salcedo in transferring the

province from Spain to

France. A season of great festivity

ensued in which the courtly

Spanish grandees and the chivalric

French officers competed for

the splendor of ceremony and the

extravagant expression of

*Jefferson, in order to learn what

really had come into possession

of the United States through his treaty,

arranged for an exploration,

choosing for the leaders Meriwether

Lewis and William Clark, the latter

the younger brother of the famous George

Rogers Clark. These two

daring explorers proved to be ideal

pathfinders. They had been army

officers of military experience under

General Anthony Wayne. Lewis, a

kinsman of the President, had been for a

time his private secretary. They

set out from St. Louis in May, 1804,

with a company of some fifty men,

made their way by the Missouri and its

tributaries to the RockyMount-

ains, and thence followed the Columbia

from its head springs to the

Pacific, reaching the latter point

November 15, 1805.

The Louisiana Purchase. 259

mutual good will. General Victor was

expected any day, when

the transfer of the gay city from the

allegiance of Spain to France

was to be consummated. Suddenly, and to

the consternation of

both parties, there came by the arrival

of a vessel from Bordeau

the news that the province had been sold

by France to the United

States.

It was a strange and unexpected shifting

of the scene. In-

stead of the arrival of Victor came the

instruction from Napo-

leon to Laussat for the latter to act as

the commissioner to re-

ceive the colony from Spain and then

pass it over to the United

States authorities. On November 30th

came the ceremony of the

cession by Spain to France. Eye

witnesses recorded that it was

an elaborate, but rather heavy,

ceremony. The day was gloomy

and wet, the Spaniards were depressed

and the French dismayed.

The formality took place in the square

of the Place D'Armes and

the council chamber and balcony of the

Cabildo-an imposing

building erected some years before and

at that time the most

stately, if not the most spacious, in

the United States, the meet-

ing place of the municipal council of

New Orleans. On that

day the Spanish Alcalde and his suite

yielded the colonial and

municipal authority to the French Mayor

and his council. The

yellow flag of Spain was lowered from

the flag staff in the Place

D'Armes and the Tricolor-the red, white

and blue-of the

French republic hoisted in its stead.

The Spanish officials with-

drew with all the stately circumstance

that they could assume.

Seventeen days later the American

commissioners, with their es-

cort of troops arrived and encamped two

miles outside the city

walls. Three days afterwards, on

December 20, the second great

ceremony took place, in which was

consummated the transfer of

the city and the territory it

represented, from France to the

United States. It is recorded that it

was a day radiant with

natural beauty and sunshine, in strange

contrast to the rain and

gloom of weather which prevailed when

the previous transfer

from Spain to France had occurred. At

nine o'clock the Amer-

ican militia marched with flying banners

and beating drums into

the Place D'Armes, General James

Wilkinson, commander-in-

chief of the army of the United States,

and Governor C. C. Clai-

borne, Governor of Mississippi, the

American commissioners,

|

260 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

mounted upon prancing chargers headed the column of Ameri- can soldiers comprising a detachment of dragoons in red uniform with contingents of artillery, infantry and carabineer. The Americans drew up in parade form opposite the French troops, who had likewise assembled in the open square. The authorized officials with the city dignitaries, ecclesiastics and distinguished civilians then ascended the broad stairway of the Cabildo to the council chamber. Laussat placed himself in the elevated chair of honor, Governor Claiborne and General Wilkinson seating them- |

|

|

|

selves respectively on his right and left. The legal formalities of the previous three weeks were then repeated; Laussat delivered the keys of the city to Claiborne who was to be the first territorial Governor of Louisiana, and Laussat publicly absolved the French inhabitants from their oath so recently taken of allegiance to France and announced their transfer from citizenship in the French republic to citizen- ship in the American republic. Secretaries read the treaty of cession in both English and French; Laussat read his creden- tials from the first consul; Claiborne then read Jefferson's com- mand to him to receive the province; the commissioners then |

The Louisiana Purchase. 261

arose and passed out upon the elevated

balcony of the Cabildo,

which overlooked the open square, upon

which was now formed

the international tableau of the French,

Spanish and American

soldiers, and the crowds of citizens of

the three nations. A bi-

zarre setting to the brilliant scene was

created by the interming-

ling crowds of black slaves and the

groups of native American In-

dians, the latter arrayed in all the

plumage of their ceremonial at-

tire. At a given signal the French

Tricolor, which had so re-

cently been raised, was slowly lowered

from the flag staff, and in

its place was raised the Red, White and

Blue, this time in the

form of the Stars and Stripes-the symbol

of the American re-

public. This imposing and important

incident was emphasized

by the instant firing of every gun in

the city, in the fort, the bat-

tery and from the ships afloat in the

port; the bands played the

American airs, the multitudes shouted

and from the balconies and

windows of the great square hall and

handkerchiefs were waved

in applause. This scene however had its

pathetic coloring, as

writes one witness: "A French

officer received the Tricolor in

his arms as it came to the ground, and

wrapping it about his

body strode away with it to the

barracks; the crowd fell in be-

hind as at a funeral; the American

soldiers presented arms as they

passed, and the men in the street

uncovered and with great so-

lemnity it was carried to the government

house and left in the

hands of Laussat." Governor

Claiborne then delivered his in-

augural, in which he promised the people

of Louisiana that they

should never be transferred again. Such

a pledge, if believed,

must have been, indeed, a balm to their

wearied feelings, for their

country, if such it may have been

called, had, in its history, been

transferred, counting its bestowal by

Louis XIV. on private own-

ers and the swapping back and forth

between Spain and France

and now America, no less than six times.

The momentous event was at an end. The

stupendous terri-

tory called Louisiana, embracing an area

of 1,200,000 square

miles or nearly two-fifths of the total

area of the United States

passed forever into the possession of

the American people. It

included all, or nearly all, of

Louisiana, Arkansas, Indian and

Oklahoma Territories, Missouri, Kansas,

Iowa, Nebraska, Min-

nesota, North and South Dakota, Montana,

part of Colorado, and

262 Ohio Arch. and Hist.

Society Publications.

all of Wyoming, Idaho, Oregon, and

Washington, in all sev-

enteen states and territories.

"If the Louisiana purchase,"

says Mr. Sloane, the historian,

"revolutionized our national

outlook, our constitutional attitude,

and our sectional control, it has quite

as radically changed our

national texture. From that hour to this

we have called to the

masses of Europe for help to develop the

wilderness, and they

have come by millions, until now the men

and women of Revolu-

tionary stock probably number less than

15,000,000 in the entire

country. These later Americans have,

like the migrations of the

Norsemen in central and southern Europe,

proved so conservative

in their Americanism that they outrun

their predecessors in loyalty

to its essentials. They made the Union

as it now is, in a very

high sense, and there is no question

that in the throes of civil war

it was their blood which flowed at least

as freely as ours in de-

fense of it. It is they who have kept us

from developing on

colonial lines and have made us a nation

separate and apart.

This it is which has prevented the

powerful influence of Great

Britain from inundating us, while

simultaneously two English-

speaking peoples have reacted one upon

the other in their radical

differences to keep aflame the zeal for

exploration, beneficent

occupation, and general exploitation of

the globe in the interests

of a high civilization. The localities

of the Union have been

stimulated into such activities that

manufactures and agriculture

have run a mighty race: commerce alone

lags, and no wonder,

for Louisiana gave us a land world of

our own, a home market

more valuable than both the Indies or

the continental mass of the

East."

|

THE LOUISIANA PURCHASE.

E. 0. RANDALL. In that striking and stirring century known as the sixteenth, began the voyages of discovery and the expeditions for occupancy, |

|

|

by the Anglo Saxon and the Gaul, of the North American continent. The French were led by Jacques Cartier, who in 1534 entered the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Other chivalrous and adventurous Frenchmen followed with various experiences, until 1608, when Sam- uel Champlain encamped upon the Heights of Quebec, and estab- lished a colony on that famous Canadian site. With equal energy and dar- ing the Englishman, the inveter- ate rival of the Frenchman, was slowly but surely getting a firm |

|

foothold on the American shore. In the year 1498, more than a third of a century before Cartier's little vessel plowed her way up the St. Lawrence, and before Columbus had made his last voy- age, the Cabots, John and Sebastian, father and son, coasted along the continent of North America and claimed it by dis- covery. In 1607 the Jamestown (Virginia) colony became the first permanent English settlement in America. In 1666 Rob- ert Cavalier Sieur de La Salle sailed up the St. Lawrence, trav- ersed the Great Lakes, and in 1682 descended the Mississippi to its mouth and gave the name Louisiana, in honor of his sav- creign Louis XIV., to the vast region comprising the basin of the great "Father of Waters," and took possession of a great undefined territory in the name of France. Meanwhile the 248 |

(614) 297-2300