Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

JOHN BROUGH.

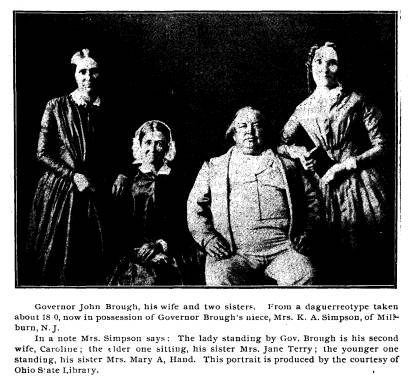

OSMAN CASTLE HOOPER.

John Brough is generally thought of as

the last of Ohio's

war governors, the sturdy Union man who,

as a candidate for

the executive office in 1863, defeated

Clement L. Vallandigham

by the then unheard of majority of more

than 100,000 votes. He

was all that, but he was more than that,

and it is the duty, as well

as the pleasure of Ohioans to recognize

it.

If ever a masterful man sat in Ohio's

executive chair, it was

John Brough. No general in the field was

more stern or more

zealous, more watchful of others, more

careless of himself. Those

days of 1863 were dark and gloomy for

the Union cause; the

election of Brough was like a sunburst.

It proved that Ohio,

though not without its falterers, and

palterers, was steadfast for

the Union; and it steadied the whole

line of northern states,

cheered the heart of Lincoln and put a

new enthusiasm into the

armies in the field. The power that the

people of Ohio gave to

Brough on that election day, he

exercised to the fullest extent-

to his temporary discomfiture, perhaps,

but to his lasting glory.

It is for this that John Brough is best

remembered, but

there are other things for which he

should be honored. Before

he stood like a giant at the head of a

patriotic state during the

Civil War, he had stood as the especial

champion of the state

when it was beset with debt and had

helped to save it from the

shame of repudiation, and before that,

he had served in the legis-

lature, striving to rescue the state

from cheap money and ruin-

ous speculation.

As journalist, as clerk of the senate,

as member of the house

of representatives and as auditor, as

well as in the capacity of

governor, John Brough bore himself well

and with a sturdy

honesty and a vigorous intelligence

which, while they won for

him the invective and sometimes the

ridicule of his contempo-

(40)

John Brough. 41

raries, clearly entitle him to the

highest regard of all who have

come after him.

In the early years of the nineteenth

century, there came

across the ocean from England, John

Brough, a native of the

British capital, and his frail English

wife. They were ac-

companied by several other men and their

wives, all seeking

home and fortune in the domain of the

vigorous young nation

that had recently won its independence.

They settled in Wash-

ington county, Ohio, on or near the

Little Muskingum three

or four miles east of Marietta, and

entered on the life of pioneer

farmers.

Of these first American Broughs, all too

little has been re-

corded, but it is known that they

commanded the respect of their

neighbors and that the regard in which

they were held was con-

tinued to their children and their

children's children. There is

the record of the death in 1807 of the

frail English wife in her

forty- eighth year and of the subsequent

marriage of Brough,

already a man past middle life, to Jane

Garnet, who was born in

Pennsylvania in 1785.

John Brough, while not a thrifty farmer,

was a commanding

figure in the Marietta settlement. He

was looked up to in a

double sense, for he was six feet tall

and of fine physique; and,

besides, was philosopher in a homely

way. It was natural that

he should be chosen Justice of the Peace

and equally so that the

"Squire," as he was commonly

called, should be elected sheriff

of the county. That distinction came to

him in 1811. Then

the Broughs moved into the court house

and jail building which

also contained living quarters for the

sheriff - a structure erected

in 1798 and demolished in 1846 to make

room for the present

jail. In the former building John

Brough, the future governor,

was born September 17, 1811. He was the

second of five chil-

dren - Jane, the eldest having been born

in 1810, Charles in 1813,

Mary

Ann in 1818 and William in 1820.

The mother of this family died October

19, 1821, when her

baby was scarcely a year old and the

eldest child was but eleven

and when she herself was but thirty-six.

Her life record is un-

happily meager. She was born, she was

married, she bore five

children, and she died. She was buried

in Mound cemetery, now

42 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

near the geographical center of

Marietta, and a sandstone slab,

inscribed as follows, marks the spot:

IN MEMORY OF

JANE BROUGH,

WIFE OF

JOHN BROUGH,

Who departed this life, October the

19th, in

the Year of our Lord, 1821.

AGED 36 YEARS.

Blessed are the Dead Which Die

in the Lord.

In the following March 'Squire Brough

married Mrs. Brid-

get Cross, but twenty-nine days after

the wedding, the third Mrs.

Brough died and was followed six months

later by 'Squire

Brough himself, at the age of 75. No

stone marks his burial

place; only to the mother of his

children is that distinction

vouchsafed.

Whatever "Jack" Brough's life

had been up to this time, it

was different and more difficult from

this out. His education had

been begun in the Marietta school. At

11, an orphan, he found

it necessary to do for himself. 'Squire

Brough had left no

estate. He had been in his last years

but a tenant on the Cleona

farm, about a mile above Marietta on the

Ohio river and his

savings had been small, if any.

"Jack" turned instinctively to

the printing business and, as an

apprentice, he entered the office

of Royal Prentiss's American Friend. His

home was beneath

his employer's roof, and later with

Isaac Maxon, another printer.

"Jack" worked, but he also

played, and one still encounters in

Marietta the stories of "Jack"

Brough's wonderful feats in all

the athletic games upon the common. No

one could "raise"

the football as he could, and his

associates who lived to see him

governor delighted to recall those games

in which he played

John Brough. 43

so well. The last of his school

education was secured at Athens,

where for a short time while working in

the office of the Mirror

of that place, he attended the Ohio

University. It was at best a

meager training for it did not last

long, but for a youth of his

quick perception, boundless energy and

sturdy purpose, it was

enough, taken in connection with his

work in the newspaper

offices, to make him a lucid thinker and

a ready and forceful

writer and speaker. There are some minds

that absorb learning

at the very touch, and "Jack"

Brough's was one of them.

Before "Jack" Brough was

twenty, he was an editor. He

had learned the printing business and

had been to school. He

had seen other men edit, and he had an

ambition to be an editor

himself. Besides he had some opinions

and a hero, General An-

drew Jackson. So it happened that on

January 8, 1831 -Jack-

son's day - there appeared in Marietta

the Western Republican,

a weekly edited and published by John

Brough. It was published

weekly at Marietta for two years and

then was sold and moved

by its new editor and publisher to

Parkersburg. In the fall of

1833, Brough went with his brother

Charles to Lancaster, O.,

and bought the Ohio Eagle. Here

he quickly made his strong

individuality felt and, as the editor of

a partisan paper, entered

heartily into the politics of the day.

That was a time of hard

blows, and he neither spared nor was

spared; but there are

not wanting the evidences that, even

though he made enemies,

he commanded their respect, so sincere

was he in all that he did

and said. Referring at a later date to

this period of his career,

Brough wrote that he had no apology for

the asperity into which

party conflicts had led him; he had

always acted on the de-

fensive and held in supreme contempt the

authors of the base

attacks upon him.

Brough made his formal entry into Ohio

politics in 1835

when he was elected clerk of the Ohio

senate. He was the can-

didate of the Democratic majority and

received 19 of the senate's

35 votes. Seven of the Whig votes went

to Warren Jenkins and

the other nine were recorded as

"blank and scattering." Among

Brough's supporters, it is interesting

to note, was Samuel Medary,

just beginning a service in the senate

as the member from Cler-

mont county -a man who was for many

years Brough's close

44 Ohio Arch. and

Hist. Society Publications.

political friend, but destined in the

crisis of the civil war to take

a widely divergent course.

Robert Lucas was governor of Ohio.

Thomas Ewing and

Thomas Morris represented the state in

the national senate,

while in the house of representatives at

Washington, Thomas

Corwin, at the opening of his third

term, was growing in Whig

favor. Andrew Jackson, as president, had

begun his warfare on

the United States bank; Martin Van Buren

was looming up as

a presidential quantity, and William

Henry Harrison, Daniel

Webster, John C. Calhoun and Henry Clay

were striking figures

in the political foreground. It was a

time of stirring politics, and

Brough, as clerk of the Ohio senate and

correspondent of the

Lancaster Eagle, swung the partisan cudgel with all the zeal

of his young manhood. He served as clerk

of the senates of

1835-6 and 1836-7, and then was retired

by the election of a

Whig senate. But the loss of his

position did not take him out of

politics; it was only an incident in the

political war for which

he had enlisted. For a time he reported

the senate proceedings

for the Ohio Statesman, at the

same time writing for his own

paper, the Eagle, which was

widely quoted and, under his man-

agement, took rank with the leading

exponents of Democracy.

He sat as a delegate in the convention

in 1837 which nominated

Wilson Shannon for governor. He was

a member of the com-

mittee on resolutions and drafted the

plank denouncing the Whig

attitude toward the banks as a betrayal

of the people and de-

claring that those banks that had

suspended payments had for-

feited their charters.

In the fall of 1837, Brough was elected

by the Democracy to

represent the Fairfield-Hocking district

in the Ohio house of rep-

resentatives, receiving a majority of

1,422 votes. At that time

he was but 26 years of age, but so

marked and generally recog-

nized was his ability that he was made

chairman of the im-

portant committee on banks and currency.

This distinction he

owed in part to the fact that his party

was dominant, but it was

certainly a personal triumph that of the

38 Democrats in the

house, he, so young and at the very

beginning of his active leg-

islative career, should be placed at the

head of a committee into

John Brough. 45

whose hands the most important

legislation of the session was

to be given.

Governor Shannon, in his inaugural

address a few days

after the legislative session of 1838-9

began, sounded the key-

note of party alarm at the general

financial conditions. He di-

rected attention to the mania of

speculation and the over-issue by

banks, saying that "almost the

entire circulating medium of the

state is composed of bank notes,"

which he described as "not

money, but promises to pay money."

He advocated a currency

of gold and silver coin and paper which

should be safe and

convertible into coin without loss. He

also proposed a long

corrective program including the

following: To increase the

liability of bank stock-holders; to

limit the power of banks to

contract and expand the currency at

will; to require banks to

redeem their notes when they have the

means of doing so; to

prohibit them from issuing notes of a

denomination less than $5;

to compel them to publish quarterly

sworn statements of their

business; to prohibit stock-holders from

borrowing money out

of their own banks; to prohibit the

issue of post notes; to pro-

vide penalties for banks that hereafter

suspend specie payments

or in any manner violate their charters;

to authorize courts of

chancery, on a bill filed by any one

interested, to restrain a bank

that had violated its charter or had

become insolvent from ex-

ercising its powers, and to appoint

trustees to take charge of all

the effects of the bank, collect claims

and pay creditors; to pro-

hibit, under suitable penalties the

establishment within the state

of any branch, office or agency of the

Bank of the United States,

and to make it a penal offense for any

director or stock-holder

of any bank in the state to purchase or

receive, directly or indi-

rectly, the notes of the bank in which

he is interested for less

than the face value for which they

purport to be issued. "The

policy of creating a United States Bank

to act as the fiscal agent

of the government, is," he said,

"more objectionable, in my judg-

ment than any other plan which has been

prepared for keeping

the public money. I view the creation of

an institution of this

kind as fraught with the most fatal

consequences to the liber-

ties, as well as the prosperity of the

people of this country, and

a violation of the constitution of the

United States." Contin-

46 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

uing, he maintained that from the time

when money is received

by the government to the time when it is

needed for public use,

it should remain in the hands of public

officers who shall give

bond and security and shall be subjected

to severe penalties for

misusing it.

It was a great task that Shannon

proposed to the legislature

in general and to John Brough's

committee in particular. But

Brough was ready for it. On the fourth

day of the session and

before the inaugural had been delivered,

he offered a resolution

requesting the auditor to report on the

condition of the banks in

the state. This, he followed, two days

later, with a resolution

instructing his own committee to inquire

what violations, if any,

there had been of the act to prohibit

the issue and circulation of

unauthorized bank paper. No one could

have done more than

did Brough to put Shannon's bank policy

into execution. He

immediately introduced a bill to

prohibit the issue and circula-

tion of small bank notes; and a little

later reported from his

committee a bill prohibiting the

establishment in Ohio of any

branch office or agency of the United

States Bank, or any bank

or corporation not incorporated by the

laws of Ohio. His com-

mittee was zealous in the cause of

reform, and the reports which

he, as chairman, made were, if at times

prolix, vigorous and

clear-cut. He argued that the state

banks had long resisted a

national bank and, having at last lost

in the struggle, had, partly

through its overmastering influence,

entered upon a financial

orgy in which "all considerations

of public welfare have been

discarded, all laws evaded and all

justice trampled under foot,

whenever either or all stood in the way

of the grasping and over-

reaching schemes of these moneyed

institutions." Further on in

the same report, he exclaimed:

"What cause, we would ask, have the

banks had to complain of the

people? None. Every indulgence has been

extended to them, even when,

by the results of their own acts, they

had no right to demand anything.

They have trodden down the laws of the

land, yet the people have for-

borne; they have violated their most

solemn obligations to the state and

community, yet the people have forborne;

they have been driven by the

wantonness of their own acts, to close

their doors and suffer their paper

to depreciate or die in the hands of the

holders, yet the people have for-

John Brough. 47

borne; they have assumed an attitude of

defiance and threatened to bring

pressure, panic and distress upon the

community, yet the people have not

raised the hand of violence against

them, nor attempted the 'vandal' act

of their annihilation. The people seek

reformation, not destruction, and

sooner or later it must be extended to

them."

With such invective as this Brough

assailed the evils that

Shannon pointed out, earning at once the

envy of some of his

fellow partisans and the ridicule of his

political antagonists.

But, however much they called him

demagogue, all were forced

to admit that he was terribly in

earnest.

Brough did not stop with denunciation,

he proposed refor-

mation. Wherever he smashed existing

things with his vehe-

ment rhetoric, he suggested a substitute

or a corrective. He

proposed a broader application of the

principle of individual lia-

bility, on the part of directors and

stock-holders, for the debts of

the banks, and a bill for that purpose

was introduced. He pro-

posed the establishment of a board of

bank commissioners, and

such a board was created, with power to

supervise all banking

institutions and see to it that they

observed the law, and that

the interests of the public were in all

legal respects protected.

He pressed to passage the bill

prohibiting the operation in the

state of any branch of the United States

Bank. He scented a

loss to the state through the payment of

interest on the canal

debt in depreciated bank paper, and

introduced a resolu-

tion which was adopted and revealed a

deplorable condition

of affairs. He fought the practice of

issuing bank notes payable

on a future date-a practice by which

banks were taking from

their borrowers interest on their own

paper, payable six, nine

and twelve months after date and bearing

no interest, and with

the further and more important result of

depreciating still more

the character of bank paper. He

reported, after committee in-

quiry, that the state has inherent power

to tax bank capital and

urged that the existing tax on dividends

be transferred to capi-

tal. He advocated and voted for an

anti-usury bill, which was

defeated.

While the state administration and the

legislature were thus

operating to reform the banks, a

considerable element, chiefly

Whigs, was clamoring for a state bank as

an institution which

48 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

would give to finances the stability so

much needed. Petitions

from this element reached the

legislature and were naturally re-

ferred to Brough's committee. He might

have pigeonholed these

petitions which were addressed to a

hostile body. But he did

not, and this ought to be taken as an

evidence of his entire sin-

cerity and his zeal in a cause which he

believed to be right. In

a voluminous report on these petitions,

he said that there was

something in the idea that the state

might as well profit by the

banking business as to give the gain to

individuals; but the pro-

ject was, on the whole, objectionable

because, first, of the crea-

tion of a vast money power with great

influence in public af-

fairs; second, of the difficulty of

keeping it out of the hands of

the dominant party as a weapon, and,

third, of the impropriety of

the state raising and investing capital

and managing intricate

and hazardous banking operations.

Other petitions for an increase in

banking facilities, Brough

also treated at some length in the same

report. He feared that

"the mania for banking now

prevalent has very little to do with

mere facilities of trade;" he

characterized it, instead, as specu-

lative and inveighed against it, as he

did against all get-rich-

quick schemes and fictitious values.

"The fixed and settled prin-

ciples of natural and animal economy

that all sudden and un-

natural growths are but evidences of a

diseased state," he said,

"applies with no less force to all

the walks of business, the rise of

cities and towns and the prosperity of

states." "We turn," he

said, further on, "with a ready ear

to the demands which are

made in the name of commercial greatness

and wealth, while the

voice of labor and industry falls with

the dull sound of a heavy,

tedious tale; we dwell with greedy eyes

upon the picture which

self-interest too frequently gilds with

the brightness of public

advantage and prosperity, while the

great interests of the greater

mass, whose capital is toil and whose

dividend and speculation

its reward and return, are looked upon

as mere shadowing of the

picture, put in to fill up the

background, and ofttimes, we are

prone to conceive, with unseemly

taste." If that sounds soph-

omoric, here is something that bumps the

earth at least once or

twice:

|

John Brough. 49

"The only safe criterion by which to judge of the necessity for an increase of banking facilities is the close application of our present means to the trade, commerce and business of our state. It is vain and delusive to argue the necessity of increase from the 'demand,' in the usual accep- tation of the term. The increase of bank money only increases the |

|

|

|

means of its expenditure in speculation or in extravagance, and, increase as far and fast as you will, the cry will still be that of the hungry leech, 'Give, give!'"

Concluding this phase of the report, he says that "the change which will in some measure result from the several acts passed this winter for the reformation of the banking system will effect a reduction in the present circulation and a diminution of the Vol. XIII-4. |

50 Ohio

Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

facilities afforded banks;" but he

hopes the change will be ac-

cepted by the banks in good part and

that they will withdraw

from speculation and devote their means

to legitimate trade,

adding that, if they do not, the

creation of additional capital or

the perfection of another system will be

imperious on the legis-

lature.

Brough was one of the most active

members of the legis-

lature. His work as chairman of the

committee on banking and

currency, arduous as it must have been,

did not exhaust his

energy; and the records show that he

participated in all the

important debates and was rarely absent

at the taking of a vote.

His opinions were most positive and his

support of them most

determined-so much so that he, more than

any other member

of the majority party, became the target

of the opposition.

One of the subjects before the

legislature that winter was

the negro question-the rights of those

blacks who lived in

Ohio and the duty of the state toward

those who had escaped

from slavery in the South. Abolitionists

were comparatively few

but very active, and were loved by

neither of the great parties.

They were generally held to be

mischief-breeders whose activity

was weakening the Union and injuring,

most of all, those whom

they sought to set free. Brough, it is

interesting to note, in view

of his later career, shared this

sentiment and gave free ex-

pression to it. The question arose on

the presentation of peti-

tions from negro residents for the

removal of the existing legal

disabilities. Brough met this appeal by

introducing the following

resolution which was adopted:

"That the blacks and mulattoes who

may be residents within the

state have no constitutional right to

present their petitions to the general

assembly for any purpose whatever, and

that any reception of such peti-

tions, on the part of the general

assembly, is a mere act of privilege or

policy, and not imposed by any expressed

or implied power of the con-

stitution."

Brough voted, not only for this, but for

other resolutions

maintaining the rights of the several

states, declaring that con-

gress has no jurisdiction over the

institution of slavery, asserting

that agitation of the slavery question

was a violation of the faith

John Brough. 51

which ought to exist among the states,

denouncing the plans of

the abolitionists as impracticable and

dangerous and declaring

that it was unwise to repeal the laws

imposing disabilities upon

negroes. Nevertheless, his views on the question were more

advanced than those of most of the

politicians of the day. He

had been thinking and he saw the right.

In one of his speeches

he said:

"I am no friend to slavery. I wish

most ardently that it had never

existed, or that we had some means of

ridding ourselves of it; but I

regard these philanthropists as the

worst enemies of the slave. Neither

do I wish to restrict or injure any of

the rights and privileges which the

blacks already enjoy in our state. They

have the protection of our laws

in their lives and property and, when

left to their own action, are dis-

posed to be grateful. They would never

have sought the notoriety which

is given to them here; they would never of

themselves have dreamed

of violation of their rights or

restriction of their privileges, but for the

instigation of wicked men who might

learn, with benefit to themselves,

the principle of gratitude and regard

for protection bestowed, of those

over whose bleeding rights they shed so

many hypocritical tears."

In another speech he said:

"Already has the question of

abolition shaken the fair fabric of our

freedom from center to center-aye, sir,

it has rocked it till brave and

good men have looked on with mingled

feelings of dread and admiration

-dread lest the next convulsion should

rend it in ruins, and admiration

that the noble structure has so well

withstood the assaults directed against

its most pregnable part. I would not

speak lightly of the danger of this

Union, or allude carelessly to the fear

of its dissolution; but, if ever that

bond be rent asunder, if chaos come

again over the bright hopes and

prospects of the friends of human

freedom throughout the earth, the

besom of that destruction will have been

hurled and guided by the reck-

less spirit of fanaticism that broods in

darkness and gloom over our

happy land.

"The states of the south are

looking to their sisters of the confed-

eracy with weary and anxious eyes. They

ask us to let them alone in

their domestic relations; they beseech

us not to trample with rude feet

upon the rights which they have acquired

under the constitution. What

shall we say to them by our action here?

Shall we hold out to them the

empty mockery of friendship and

neutrality, while at the same time we

do an act which must put our professions

to the blush? Shall we say

to them that we seek no interference

with your domestic relations, that

we do not interfere with your property

in your slaves nor their allegi-

52 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

ance to their masters, while at the same

time we elevate this class of peo-

ple in our own state to our own rights

and privileges, admit them within

our legislative halls and acknowledge

their rights as citizens to instruct

us, their representatives in the course

of our duty? This would be mock-

ery, indeed! How it would add to the

security of the slave-holder who

is cursed (for I regard it as a curse)

with the care and possession of

property of this kind!

"The doings of wicked men have

already planted apprehension and

agony where peace and security reigned

before. The Virginian, the Ken-

tuckian, the Carolinian are ever haunted

by the terrors of servile insur-

rection. As we regard our own high

character, as we love the union of

these states, as we respect and would

protect the lives and property of

our southern brethren, let us not as a

state join in this unholy warfare."

Those words were spoken in 1838.

Twenty-three years later

the terrible reality of that prophetic

vision presented itself. Then

the conservative Brough had disappeared

and the aggressive

Brough had taken his place. Finding that

the Union could not

be preserved by conciliation, he gave himself

heart and soul to its

preservation by force.

Brough was elected auditor of state by

the legislature, as

the custom then was, February 8, 1839, for three years from

March 15, 1839. On the latter date, the

house of representatives

adopted resolutions which, after

humorously recognizing "the

unpleasant situation into which John

Brough has been forced

by his friends against his own wishes

and expectations," to-

gether with the "necessity either

to abandon the people who

sent him to the legislature or the

office to which the legislature

appointed him," cordially thanked

him for the "able and indefati-

gable manner in which he has carried out

the great measures of

reform in which the present general

assembly has been engaged."

Thus, three days before the end of the

session, Brough's

legislative career ended. Taking a leading part at the very

opening of the session, he maintained it

to the end. The Whigs

had ridiculed him when they could and

feared him as a political

opponent all the time. Frank and

masterful, he had made ene-

mies in his own party. He was ambitious,

of course, but not

beyond his deserts. He had a mind for

finance; he thought deep

and spoke well. He was industrious,

business like and clever.

His ambition to be auditor was mentioned

in the newspapers

John Brough. 53

as soon as the session began, and it may

have been to prove his

worth that he had sought the

chairmanship of the committee

on banking and currency. A hostile press

early dubbed him the

"chancellor of the exchequer,"

even as it referred to the house

of which he was a member as

"Brough's department." He

was

accused of rank partisanship, and his

oratory was likened to the

"roaring of a gored buffalo."

But neither ridicule nor abuse

seriously affected him. He knew what he

wanted to do and

proceeded to do it and in the doing

excited so much admiration

that, at the time of his election as

auditor, his severest critics

in candor admitted that he would make an

efficient officer.

Though by his election as auditor Brough

was removed

from the swifter partisan currents, he

was by no means oblit-

erated. He had identified himself with a

financial policy that the

Whigs abhorred and continued to be a

target for their campaign

practice. Shannon in his second message

had swung just far

enough back toward the Whig financial

idea to excite some Demo-

cratic criticism. It was, therefore, thought that there would

be some opposition to his renomination,

and the political specula-

tors of Whig faith early surmised that

Brough would be the

choice of the anti-Shannon men. "He

will be a hard man to

beat," they said, "but the

Whigs of Ohio must not permit them-

selves to be frightened, even by John

Brough." The gossips

followed him to Cincinnati, whither he

went, as auditor, to get

specie to pay the interest on the public

debt; and in his every

movement and even in his silence, they

found evidence of the

correctness of their guess. Referring to

Brough as the "Jupiter

Tonans of Ohio Locofocoism," the Ohio

State Journal on

Christmas day, 1839, thus gave him

standing:

"While a member of the house, he

stood forward, the very head

and front, the champion, the directing

spirit of the Bentonian party in

Ohio. There was his small bill law, his

bank commissioner law, his law

against the paper issues of the Bank of

the United States. Wherever credit

and confidence were susceptible of a

stab, there did Mr. Brough stab.

He succeeded but too well. There was a

pliant legislature at his heels and

he made the most of his power. Some have

vainly supposed that he has

been shorn of his locks. It is not true.

There are, it is true, men of his

own party-his former friends and

co-laborers in the work of the Ben-

tonian frenzy-who now wish to hurl him

from his high estate. They

54

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

wish to make room for themselves and

they, therefore, seek his destruc-

tion; but take our solemn word for it-as

long as Locofocoism has an

abiding place in Ohio, Mr. Brough will

be its master spirit."

Brough allowed the governorship gossip

to go on till it

ceased to amuse him and then he knocked

down the house of

cards with a communication in which he

explained that he was

not a candidate for governor and could

not be since he had not

yet reached the constitutional age of

30. He was then but 28.

Shannon was renominated for governor,

January 8, 1840,

with none of the predicted opposition.

On the following Febru-

ary 22, Thomas Corwin,

then a member of the house of represen-

tatives at Washington, was nominated for

governor by the

Whigs and resigned his seat to accept.

Then with William

Henry Harrison and Martin Van Buren

contending for the

presidency, the great campaign of 1840

began. Brough took

the stump for Shannon and Van Buren and,

as usual in what-

ever he undertook, made himself

conspicuous to all and ob-

noxious to those he opposed. He gave and

took many hard

blows and, if possible, still more

embittered the Whig sentiment

against him. While he was absent from

his office on speaking

tours, the Whig press clamored for his

return to the duties

which he had been elected to perform and

sharply criticised the

management of his office. But they

brought him back only

occasionally to answer their charges,

generally with success.

Now and then a Democratic editor,

probably moved by jealousy,

joined in the hue and cry against Brough

for having a private

as well as a public occupation; and

every such recruit, one may

be sure, brought joy to his Whig

critics. The success of the

Whig state and national tickets, in

opposition to all that Brough

had urged on the stump, aggravated

rather than decreased the

Whig antipathy for Brough. When it

became known that he was

casting about for another newspaper and

had actually bought

one the clamor against him for alleged

neglect of his official

duties was renewed, and there was even a

suggestion that the

legislature should declare the office of

auditor vacant. Another

phase of the clamor is revealed in the

following from a Whig

paper of the time:

John Brough. 55

"Rarely does the editor go to the

State House without seeing

Brough in one house or the other,

passing away the time for which the

state grants him a large remuneration,

idly or in private intercourse with

members, and under the circumstances

calculated to excite the suspicion

that he improperly intermeddles in

affairs of legislation and seeks to con-

trol it for personal or political

motives."

Thus, according to his critics, whether

Brough was on the

stump, or in Cincinnati, or in the

legislative halls, he was in

the wrong place; and when he was at his

desk in the auditor's

office, he was being paid too much

money. All this is inter-

esting for it shows what a veritable

thorn in the Whig flesh

John Brough was. When Brough ventured to

reply that he was

quite as constant in his attendance upon

his duties as was Gov-

ernor Corwin, it was retorted that no

governor had ever spent

all his time in Columbus and that

"the governor hasn't even an

office here, burrowing with the fund

commissioners when in the

city,"-an answer, by the way, which

is more interesting as a bit

of history than as an argument.

It was in the spring of 1841 that Brough

and his brother

Charles H. (who had just retired from the

legislature) bought

the Cincinnati Advertiser, an

established Democratic paper,

changed the name to the Enquirer and

announced that the paper

would "sustain the principles and

policy of the great Democratic

party and act, hand in hand, with the

Democracy of Hamilton

county." The paper continued in

their hands until 1848, and

exerted an influence in politics not

less than it does to-day under

another management.

The possession of an important newspaper

increased

Brough's strength as a political factor

and brought him more

than ever into the public view. Though

he had announced that

the Enquirer would support the

principles of the Democratic

party, he reserved the right to

criticise members of the party

when their conduct did not accord with

his judgment, and that

right he exercised as vigorously as he

had ever done before.

More than all else, he seemed to be the

defender of the financial

policy which he had as legislator helped

to establish, and when

he found Democratic candidates or

legislators departing from

that policy, he punished them with his

invective.

56 Ohio

Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

From criticism

of Brough for absenteeism in 1840, his foes

passed, in 1842 to

criticism of him as an autocrat in office. In-

stead of making him a

less figure, their assaults seemed to be

making him a greater,

and there is a strong flavor of desperation

in the following

indictment against him which appeared in an

editorial in one of

the Whig papers of the day:

"The constitution

strips the governor of nearly all power and

patronage and, in comparison

with the powers of other governors, ren-

ders that high

functionary but little more than a cipher. But power in

a political community

must exist somewhere, and in Ohio it is fast clus-

tering in the hands of

a subordinate of the executive department, whose

tenure of office is

independent of the popular favor and is by a year

greater than the

governor's. * * Mr. Brough's predecessors have not

aspired to a

concentration of all powers in their hands, but have been

content to pocket

their salaries and perform their simple duties without

encroachments upon

other departments. * * But the present incumbent

perceives that the

office of auditor is really the highest and most im-

portant in the state,

and he is determined to make it still more efficient.

It is through his

influence, therefore, that the board of fund commis-

sioners has been

abolished and another created, of which he has been

constituted the life

and soul. * * When the fund commissioners' board

was first established,

its duties were considered to be of such a nature

that they could not be

mixed up with the affairs of the auditor's office,

but the present

auditor thinks otherwise; and he has been gratified in

his ambition to have

the whole power of the board imposed on his hands.

"Mr. Brough has

made some large strides, this winter, toward

monopolizing official

places and placing himself conspicuously before the

public. He found means

to crowd himself into the board of trustees of

the Ohio university;

he got himself elected a trustee of the Blind asylum,

and finally persuaded

the legislature to vest in his hands, in effect, all

the powers and duties

devolved upon the fund commissioners. In his

last capacity, he is

now absent among the money kings of Wall street to

try his hand at

financiering, whilst his proper duties are neglected at

home. How

insignificant has the office of governor become beside this

new Colossus of the

executive department of the government. * * In-

deed, the grasping

disposition and accumulating official influence of the

auditor of state has

alarmed the jealousies of some of his own friends

who, apprehensive of

the manner in which it is suspected the last may

be employed, have

begun to call attention thereto."

To this, another paper

adds that "he (Brough) has now and

for years past has

possessed the power to tax the people heavy

or light, as suits his

sovereign will and pleasure- a power too

|

John Brough. 57

dangerous to remain in the hands of any man, no matter how pure he may be, and which rightfully belongs to the law-making power of the state." The same paper refers to Brough as a "mere politician," and expresses the opinion that the auditor should be robbed of four-fifths of his immense power. There was in all this something more serious than per- sonal or party opposition, something radically different from the assumed alarm at the concentration of power. That something, |

|

|

|

Governor Dennison in later years called repudiation. It took the form of an effort to keep down the taxes which would have re- sulted in a failure to meet the canal debt interest and in the de- feat of a proposed loan to complete the public works. This spirit had its expression in the legislature of 1843 when it was |

58 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

sought to add to the appropriation bill

an amendment prohib-

iting the auditor from levying a greater

rate of taxation for

canal purposes than was levied in 1842.

That would have kept

the levy down to 23/4 mills, whereas a 5-mill levy was necessary

to meet the canal obligations. Only 17

representatives and four

senators voted for the amendment and it

was defeated. The

battle had been fought and won. The ease

of the victory, how-

ever, did not prevent alarm in financial

circles, and Brough's mis-

sion to New York, whither he went to

place an additional loan

of $1,500,000 was not an easy one. The

state's paper was sell-

ing at 67 cents on the dollar, and there

was a marked indisposi-

tion, on the part of capitalists, to

risk more money in a state where

the repudiation spirit had appeared even

in so mild a form. But

Brough was not to be discouraged. The

commission, of which

he was rightfully enough said to be the

head, went personally

to the capitalists and laid before them

a circular in which the

weakness of the repudiation movement was

fully exposed. The

proposition before the legislature and

the votes in each house for

it were set forth, the financial

condition of the state was re-

vealed and the plan of levying taxes to

meet the interest on the

debt was explained. The auditor made an

excellent impression

in New York, as the prints of the day

show, and some of his

bitterest critics at home, finding how

their previous comments

had hampered him and actually

misrepresented their own real

purposes, hastened to condemn at home

the repudiation that he

was fighting in New York. After a

month's labor, Brough

succeeded in placing $600,000 of the

proposed loan at 7 per cent.,

giving an option on the remaining

$900,000. That, too, was

taken, all at par. Thus the crisis in

Ohio finances had been suc-

cessfully passed, thanks to an honest

legislature, but thanks, also,

to the sturdy auditor, whose critics at

times thought he was doing

too little and at other times that he

was doing too much for the

state.

Brough's reports as auditor are an

interesting study. They

are precisely what might be expected

from a man who had played

so important and conservative a role in

the legislature. There

he had sought to stay mad speculation

and restore the currency

to a sound basis; here he did what he

could to punish official dis-

John Brough. 59

honesty, prevent extravagance, secure

the payment to the state

of all that was justly due it and to

defeat repudiation. When he

became auditor, the state debt was $12,500,000; when he

left

the office six years later, the debt was

nearly $20,000,000, but

the canals had been completed and nearly

half a million had been

invested in the stock of railroads, the

then new mode of trans-

portation. That the increase would have

been greater under a

less watchful auditor is probably true.

His admonitions were

often disregarded, if not resented, by

the legislature; but his re-

peated protests must have been in some

measure a check upon

expenditure.

In his first report, Brough urged the

legislature to stop ex-

penditures until "some of our

numerous public works shall as-

sume a productive character." He

pointed out lands that were

evading taxation, exposed school fund

defalcations and indi-

cated banks that were delinquent in

taxes. The energy of his

executive work is shown in the fact that

the amount of tax ar-

rearages paid in jumped in one year from

$400 to $5,000, while

the school fund defalcations made good

amounted to $12,000.

He sounded the alarm again in 1840.

Urging economy on

a legislature which had increased the

debt by two and a half mil-

lions, he argued that a public debt is

not a public blessing in a

republic, though it might be in a

monarchy, by holding the peo-

ple together and preventing revolution.

Said he:

"The accumulative character of

public burdens is one of the most

serious diseases by which the vitality

of free institutions can be attacked;

for no generation will do more than to

change the character of these

burdens, removing them from one position

to another where they will be

more easily borne, until at length the

confidence and satisfaction of the

public mind are destroyed and public

liberty, weakened by long continued

endurance, sinks beneath the weight of

accumulated grievances, a vic-

tim to the power of money which has subverted

it under the guise of

public good."

1841 he repeated his warning as to the

debt, which he found

still increasing. He reported continued

embarrassment through

the suspension of banks, whose currency,

since the national gov-

ernment would not take it for postage,

had to be exchanged for

60 Ohio Arch. and Hist.

Society Publications.

specie at a loss. The revenues from the

public works had fal-

len off and there were defalcations in

canal tolls amounting to

15,420.

The turnpike companies, too, were misbehaving and

received a severe and probably just

excoriation. The one bright

spot in the report was the collection of

$11,768 back taxes. It is

interesting to note that in this report

Brough suggested to the

legislature the creation of the office

of attorney general that the

state might have always at its command

an officer to promote

and guard its interests in the courts.

In 1842, he reported that the public

debt had increased

$1,500,000, that the annual interest

charge was $950,000 and the

deficit in interest was $281,650. In this report

he took up the

question of taxation and urged the

appraisement of all taxable

property at its actual cash value.

In 1843 he advocated a better law

governing the sale of land

for taxes and the granting of deeds to

the same. He argued at

length that the power of the state was

ample and its right mani-

fest. It was, he urged, unjust to sell

one man's chattels uncon-

ditionally and withhold the penalty from

another who owns land.

It was an indignity to the state to

permit land-owners to refuse

just tribute and mock the commonwealth.

How the taxdodgers

must have writhed under his lash!

Again and again he called attention to

the increase in the

public debt, the interest on which had

grown to $1,000,000 per

annum, $600,000 of which had to be

raised by direct taxation be-

cause the public works were unfinished

and unproductive. But

the state debt, he pointed out, was not

one-third the burden; the

greater portion was made up of county,

township, road, poor

and other charges. Blame, he insisted,

could not be laid at the

door of the civil administration of the

state, for its cost was less

than $200,000 a year. "You may look

in vain," he said, "over

the states of the union for an instance

of even half our popula-

tion, our territory, our interests, our

business character and re-

lations, our trade or our commerce,

being governed with the

same

expenditure."

"Considerations of duty," however,

prompted him to say that the

expenditures for repairs on the

canals were disproportionately large,

that there were too many

officers and retainers, too much

favoritism and too little economy

John Brough. 61

and accountability. Recurring to the

debt, the nightmare of

which seemed to be ever with him, Brough

wrote in conclusion:

"In relation to the debt in the

aggregate, now that our works are

completed, sound policy requires that

here it should be stayed. * * Our

ability to sustain what we now have is

undoubted; it is the increase

which will again prostrate our credit

for the reason that, whilst it will

add to our obligations, it will at the

same time violate our faith. It is

useless to multiply words on this theme.

Prudence, discretion, sound

financial policy are no longer arguments

that enter into the consideration

of the subject. It is now the stern

command of duty-duty to the state,

its honor and its faith which are yet

untarnished, and duty to its people

who have thus far borne the burdens

without repining, and whose hon-

esty and integrity have spurned the very

idea of repudiation. To the

requirements of that duty, thus imposed

by the state and the people you

represent, I am convinced that you will

not turn a deaf ear. Be firm in

this, and the character of our great

state will be maintained; whilst the

accumulating revenues upon our great

works will gradually relieve our

people of the taxation that now rests

upon them. Depart from it, and the

end is at hand. It is written in a few

words-a state dishonored and a

constituency disgraced."

In his last report as auditor, made in

1844, Brough was still

urging reforms, the chief of which were

the adoption of the

principle of a cash valuation as a basis

for taxation and the

enactment of more efficient laws for the

sale of delinquent lands.

It was a splendid service that Brough

performed as auditor.

If there was grudging recognition of it

at the time, it was not

always so. The words of William

Dennison, the first of Ohio's

war governors, spoken at the Brough

memorial services, August

30, 1865 are here pertinent:

"It has fallen to the lot of few

men to perform such a financial

service as Brough performed while

auditor. Eighteen hundred and forty-

two was the gloomy year in Ohio finance.

Charters of banks were ex-

piring by limitation; banks were

preparing to close up their affairs and

draw in their debts; and to that extent

the community was denied the

currency it had formerly enjoyed and was

under serious apprehension as

to what would be the condition of the

state after the banks should close.

Added to this and of graver moment was

the fact of the state being then

under a large public debt, accruing out

of the construction of the public

works. A considerable portion of the

works was unfinished and other

portions, finished, were yielding little

toward the cost of their construc-

tion. * * The duty then devolved upon

Brough, in connection with

62 Ohio Arch. and Hist.

Society Publications.

the commissioners of the sinking fund,

to devise ways and means of

meeting the accruing indebtedness of the

state. He could have accom-

plished this, it may be, without any

extraordinary effort, if there had not

been another evil intervening that was

even more alarming than those to

which I have adverted. It was the

threatened spirit of repudiation in

Ohio. * * The course of Governor Brough

in this matter did more

than anything else to save the good name

of the state.

"Prior to 1842 there was no proper

system of taxation in Ohio.

Assessments were made without any system

or rule, not according to the

value of the property, but according to

the whim or caprice of the as-

sessor. Brough discerned the necessity

of a radical change in the sys-

tem. He then announced as the only just

principle of taxation that

which has been incorporated in the

financial policy of Ohio-that of as-

sessing all property according to its

true value in money. Very much of

the financial prosperity of Ohio is

attributable to the recognition and es-

tablishment of that principle in our

financial policy."

By the election of 1844, the Whigs

gained a sweeping vic-

tory. They elected Mordecai Bartley

governor and gained con-

trol of both houses of the legislature,

insuring the election of a

Whig United States senator and a Whig

auditor of state. Over

no part of the victory was there more

gloating than over the

certainty of now being able to displace

Brough. John Greiner,

the Whig song-writer and campaign singer

delighted his friends

with a post-election song on the sailing

up Salt river of the Loco

steamer, "Governor Tod." A

part of it follows:

"Her noble commander is Medary, the

great,

And his worthy friend, Hamar, the

red-headed mate;

For fear they'd run foul of the bank in

their zeal,

Old gimlet-eyed Tappan takes charge of

the wheel,

And to keep the boat trim for Polk and

for Dallas,

They threw Jack Brough into the hold for

the ballast."

On January 30, 1845, the legislature

elected John Wood

auditor, the vote standing: John Wood

52, John Brough 34,

blank and scattering 8. In welcoming Mr.

Wood as auditor,

a Whig organ, which had periodically for

years expressed a keen

apprehension that Brough was not earning

his salary, said:

John Brough. 63

"With a paltry salary attached to

the office-one hardly worthy of

a clerkship, wholly unworthy of the

state and disproportioned to the

labors and responsibilities of the

place-the people of Ohio, as well as

those abroad feeling an interest in the

management of our affairs, have

reason to congratulate themselves on

being able to secure the services

of so able an officer."

Brough transferred the office to his

successor, March 15,

and retired to private life after ten

years of strenuous politics.

The Whig press followed him out with

jibes and indulged in

much raillery when he went to

Washington, as they reported,

looking for a place under the Polk

administration. There is no

tangible evidence that Brough went to

Washington as a place-

hunter; he probably had in the Cincinnati

Enquirer a private

business that laid claims to all his

time and efforts. His acqui-

sition of that paper was no accident,

but, instead, was probably

part of a well-laid plan for profitable

and congenial occupation

when he and political office should

part.

Brough now transferred his headquarters

to Cincinnati

where he continued, in association with

his brother Charles, to

publish the Enquirer. His liking

for finance and his high execu-

tive qualities naturally led him,

however, into the railroad busi-

ness then developing; and in 1853,

having in the meantime sold

the Enquirer, he was elected

president of the Madison & Indian-

apolis railway. He continued in this

business up to and after the

breaking out of the civil war and in the

early days of that great

conflict contributed greatly to the

Union cause by facilitating

the transportation of troops. In this

service, which he performed

with his customary zeal, he again loomed

up in the public eye.

His sterling qualities were recalled,

and those who felt the need

of a strong man at the helm of state

instinctively turned to him.

Two years of the fierce struggle had

passed and the union arms

had not achieved the expected victory.

Some hitherto ardent

defenders of the Union were grown

lukewarm; those who had

at first hesitated were now sure that

the Union could not be saved.

Failure in the field had bred something

very like treason at home.

Ohio needed a strong leader, but not

more so than did the nation

need the help of a thoroughly loyal

Ohio. Brough was aflame

with zeal for the Union cause and was

invited to speak to his

64 Ohio Arch. and Hist.

Society Publications.

former fellowtownsmen at Marietta. He

accepted the invitation

and on June 1O, 1863, delivered a

stirring speech before the

largest audience that had ever gathered

in Washington county.

In the course of that speech he

arraigned some of his old party

associates on the score of disloyalty,

declared that slavery was

destroyed by the very act of rebellion

and earnestly appealed to

all patriots, regardless of former party

adherence, to unite

against the insurgents of the

South. His vigorous words

reached every corner of the state and

found repetition far be-

yond its borders. They were a trumpet

call to duty and stayed

the mental retreat as no other single

incident of the year had

done. What had been a request for

Brough's candidacy now

became a demand. He had not sought

leadership, but he could

no longer refuse it. A week later he was

nominated as the Re-

publican Union candidate for governor

and in the following Oc-

tober was elected over Clement L.

Vallandigham, the Democratic

candidate, by a majority of 101,099.

The story of that campaign and the term

of service that

followed it would itself fill a book. It

must suffice here to say

that this victory was the wild joy of

the time and has been the

pride of every succeeding year. In his

"Ohio in the War," Mr.

Whitelaw Reid says:

"It is no mere figure of speech to

say that the eyes of the nation

were upon Ohio, as her sons at home and

in the field cast their ballots.

It was felt that on the result at the

polls hung the fate of the Union.

It was Brough and Union or Vallandigham

and disunion. As Ohio

should decide, other states would be apt

to decide. Ohio voted that

October day and a mighty victory was won

for the Union-as mighty as

any that had yet been won by bullet,

shell and bayonet. Brough was

elected by the unheard of plurality of

101,099. Of this the home majority

was 61,920. Of the 43,755 votes cast by

the soldiers in the field, only 2,288

were given to Vallandigham. Of the

citizens who remained at home,

180,000 voted for Vallandigham.

Startling figures which it is well to

remember. How many are the

faint-hearted! How error spreads and

takes root in spite of Truth's most

earnest efforts!"

Thus the occasion found the man and

Brough found his

last and greatest opportunity. Brough was inaugurated gov-

ernor, January 11 , 1864, and entered

upon his work declaring

John Brough. 65

that there were but two ways in which

the war could end-

unconditional surrender by the South, or

the absolute destruc-

tion of the military power of the South.

His first recommen-

dation to the legislature bore upon the

welfare of the families

of the soldiers in the field. A tax was

already being levied for

the maintenance of these dependents but

the governor insisted

that it was not half large enough; and

the legislature, though

it hesitated to go as far as he

indicated, did pass a bill levying a

tax of two mills on the dollar and

permitting county commis-

sioners to add another mill and city

councils to add half a mill

more.

Having secured this measure of relief, Brough pro-

ceeded with his customary zeal to see

that the officers whose

business it was to distribute the relief

performed their full duty.

Where he found them derelict--and there

were not a few fla-

grant instances of the kind - he

relentlessly pursued them with

all the forces at his command, exposed

them and deprived them

of their power. When he found that with

all his watchfulness

and zeal, the fund was still too small

to meet all needs, he made

an appeal to private charity with

excellent results.

This care of the soldiers' families was

fairly supplemented

by his jealous watchcare of the soldiers

themselves. When he

took office the state had its own relief

agencies in different parts

of the country conveniently near the

armies. On his recommen-

dation the number of these was increased

and special pains were

taken to make them efficient. They were

the ministering hands

of the state and, while they were

carrying comforts to Ohio

troops, they were also answering

thousands of queries about

them from the dear ones at home. This

beneficent work was

not prosecuted without clashings with

similar agencies of national

scope. The officers of these latter

perhaps naturally thought

that all relief should pass through

their hands, but the governor

would not leave the matter to them and

there was much acri-

monious correspondence with regard to

it, in the most of which

the governor was considerate but

immovable from his purpose

to make the Ohio soldiers in the field

the state's special care.

The hospitals, too, were brought under

his inspection and

the sick or wounded Ohio soldier found

in Brough the sternest

kind of a champion. Neglect or

maltreatment was the occasion

Vol. XIII-5.

66 Ohio Arch. and Hist.

Society Publications.

of instant protest, made with such vigor

that correction promptly

followed. He demanded for Ohio's sick

and wounded soldiers

not only the best medical and surgical

attention, but also good

food and removal to hospitals within the

state at the earliest

possible date. Everywhere he insisted on

service unmarred by

the delays of red tape. To this untiring

watchfulness was due

much of the superior comfort of the Ohio

soldiers and to it many

of the wounded may attribute early

recovery, probably life itself.

But there was still another phase of

Brough's usefulness

in that last year of the war - his

splendid aid in recruiting the

armies already in the field. The cry was

for more men. The

critical moment in the war had arrived

and it was proposed to

overwhelm the Confederate armies, at the

same time protecting

the borders against incursions. It was

believed that the thing

could be done, if at all, in three

months, and the project of the

100-days men was devised. At Brough's

suggestion there was

a conference of the governors of Ohio,

Indiana, Illinois, Wis-

consin and Iowa, as a result of which

85,000 such men were of-

fered to the government-30,000 of them

by Ohio. Ohio's quota

was raised by the appointed time, at

what expenditure of energy

by the military officials of the state

it is not easy to estimate and

at what personal sacrifice on the part

of the recruits may never

be known. But it was done and done

nobly, and none was more

prompt and generous in praise of those

who did it than Brough.

Meanwhile the regular drafts were being

made and were being

attended by remarkable manifestations of

disloyalty. Bounties,

together with bribery and trickery were

doing their worst, and

an organization known as the "Order

of American Knights" or

the "Sons of Liberty" was

formed to resist the draft. Brough

learned of the organization and fathomed

its purpose and plans

by sending secret agents among them.

Having got this informa-

tion, he proceeded resolutely to

undermine the organization and

succeeded, with the inspiring influence

of the soldiers then re-

turning from the field, in thwarting

their purpose without blood-

shed. All this was accomplished by

strengthening the prison

and arsenal guards, arresting the

ringleaders of the organization

and seizing large quantities of arms

known to belong to the

organization.

John Brough. 67

With the aid of the 100-day men not all

was done that it

was hoped to do, but that was not their

fault, nor the fault of

the governor who suggested the service.

They served admirably

and at the end of the period of their

enlistment were discharged

with the thanks of President Lincoln.

While they were per-

forming the duties to which they were

assigned, Brough was

fighting still another battle-this one,

over the system of pro-

motion among the Ohio troops. Hitherto

there had been no

system of promotions. Brough could not

work without one and

he early decided that he would promote

regimental officers to

vacancies according to seniority of

service therein except in

cases of intemperance. He would give

every man a chance and

leave it to the regiment to rid itself

of incompetents. This set

the governor at odds with the commanding

officers of the regi-

ments because it took away their power

to recommend for pro-

motion.

Whatever the justice or injustice of the governor's

system, it provoked a long and

acrimonious controversy which

resulted in an organization of the

regimental officers and their

friends to defeat the governor for

renomination. It embittered

his last days without moving him one jot

or tittle from his po-

sition, and brought the administration

to an end which no one,

judging by the enthusiasm of its

beginning, would have predicted.

On February 20, 1865, Brough

wrote in the course of a long letter

to a friend:

"Personally, I am indifferent as to

the political consequences to

myself on account of this or any other

of my public acts. The most

earnest desire I have is to be permitted

to retire from a position I did

not seek and really involuntarily

assumed. I am equally indifferent as

to who may be my successor, though I

confess to some anxiety that he

shall be one who will make it a cardinal

principle not to put in the mili-

tary service or continue there officers

who disqualify themselves, by in-

temperate habits or immoral

conduct."

Added to the resentful antagonism of the

regimental offi-

cers was a certain unpopularity because

of his brusqueness.

Brough was no courtier. He was a plain,

blunt, honest and de-

termined man with some personal habits

which those who admired

68 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

him for integrity and his sterling

patriotism could not condone.

He was importuned, in spite of all these

things to make the

canvass for re-nomination; but, after

taking the matter under

consideration for a time, he declined in

a characteristically frank

statement, in the course of which he

used these words, so soon

to acquire significance:

"I very much doubt whether my

health-much impaired by close

confinement to official duties-would sustain

me through a vigorous cam-

paign; while increasing years and the

arduous labors of a long life in

public positions, strongly invite me to

retirement and repose during the

few years that may yet remain to

me."

It was about this time that, while

walking, he suffered a

severe sprain of the ankle and bruised

one of his feet. Owing

to the condition of his blood,

inflammation set in and he went to

his home in Cleveland, a very sick man.

He never returned to

Columbus. After a period of incredible

suffering, he died Au-

gust 29, 1865, four months before the

expiration of his term of

office. The deathbed scene is thus

described in a newspaper of

the time:

"On Monday evening at about 9

o'clock the governor wakened from

his insensibility in which he had lain

for some days and at the request

of his family who had gathered about his

bedside, Surgeon General Barr

informed him that all which human skill

could do for him had been at-

tempted and in vain, and that now he was

in the hands of Almighty

God. He could not live 48 hours. The

governor was greatly shocked at

this announcement and, looking General

Barr in the face, desired him to

repeat what he had said. General Barr

again stated that he had not 48

hours to live. The governor then

requested that all except his family and

General Barr should leave the room.

After this had been done, he con-

versed calmly and rationally with his

family for some time on private

family affairs.

"Turning to General Barr and apparently

addressing his remarks

more particularly to him, the governor

proceeded to speak of his religious

views and hopes. He said in substance

that he was no theologian and

had never made any profession of

religion. He had, however, always

endeavored to live honestly and

uprightly in his relations with his fellow-

men and he hoped and believed that he

had so done. He confessed that

he had sinned greatly, although he

denounced as false and slanderous the

rumors of his drunkenness and

licentiousness. But though he acknowl-

John Brough. 69

edged he had been a great sinner in the

sight of God, he stated that every

act of his in discharging his duty as

governor had been performed with

strict conscientiousness and with

prayerful regard to his responsibility,

not only to the country, but to God. He

also stated that he had never

gone to bed at night for 20 years

without first praying to God for forgive-

ness and protection, and that he died

penitently acknowledging his sins

and trusting in Christ for pardon.

"As he spoke the governor raised

his eyes, and as though death

lent supernatural keenness to him,

exclaimed that he saw the Mediator

standing on the right hand of the

Father, making intercession for his sins.

He concluded with the emphatic

declaration several times repeated, 'I die

happily and gloriously.' The scene was

deeply affecting and at the close

of it the governor put his arms around

the neck of General Barr and, with

deep emotion, thanked him for his care

and attention, expressing perfect

satisfaction with his medical treatment.

He then took his farewell of his

family. About midnight he relapsed into