Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

|

THE BLACK HAND.

JOHN D. II. M KINLEY. The Licking river, the Pataskala of the Indians, as it draws near the eastern boundary of Licking county, Ohio, flows in a winding course for a distance of about two miles through a nar- row and picturesque sandstone gorge, known as the Licking Narrows. High hills border upon both banks, their rocky sides |

|

|

|

exposed in many places to a height of fifty to sixty feet, almost continuously on the north bank, and often rising out of the bed of the stream. Just at the eastern end of the Narrows the river flows in its narrowest channel between twin cliffs. That on the south side has been quarried and boated way, so that it no longer shows the extent of the face originally presented to the stream, though enough remains to give an idea of its former height. That on the north side is isolated, with a surface area on its (444) |

The Black Hand. 445

summit of perhaps the third of an acre

covered principally with

pines, laurel and moss. It is circular

in form except on the

south, where it presents to the river a

face about two hundred

feet in length, rises to a height of

fifty feet, and, arching from

a point some distance above its base,

overhangs the stream about

fifteen feet. This is the Black Hand

rock.

At some period in the distant past these

cliffs, united,

formed an impassable barrier to the

stream, for-an old channel

turns abruptly to the north on the west

side of the Black Hand

rock, makes a circuit, and returning

cuts straight across the

present channel at a distance from its

point of departure of only

the width of the rock itself, and bears

away southward in a

narrow, rock-bound course. This old

channel resembles in shape

a horseshoe, bounded continuously on its

outer side by a rocky

ledge, and holding between its points

the Black Hand rock.

This outer rim of rock reaches the

present channel of the river

with a face of about two hundred and

fifty feet, with a height

slightly greater than that of the Black

Hand rock, and forms the

final barrier to the entrance of the

stream in its present course to

the valley beyond. It has been named by

present-day visitors,

the Red Rock. At some more recent date

the stream must have

been diverted from this old channel into

its present course.

The peculiarity of formation adds

greatly to the interest of the

place, and from the standpoint of the

geologist has been convinc-

ingly treated by Professor Wm. M. Tight,

president of the Uni-

versity of New Mexico, in Bulletins of

the Scientific Laboratory

of Dennison University.

When the Central Ohio railroad was

built, it followed the

natural grade along the south bank of

the Licking. When the

twin cliff opposite the Black Hand rock

was reached, a cut

was made through it, so that the

traveler by the Baltimore &

Ohio is hindered by this from a distinct

view of the Black Hand

rock. An electric line from Newark to

Zanesville now passes

along the north bank of the river within

a few feet back of the

Black Hand rock, and tunnels through the

Red Rock. By such

a pleasant and convenient mode of access

it is probable that the

Black Hand will be visited more

frequently by pleasure-seekers

than heretofore.

|

446 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

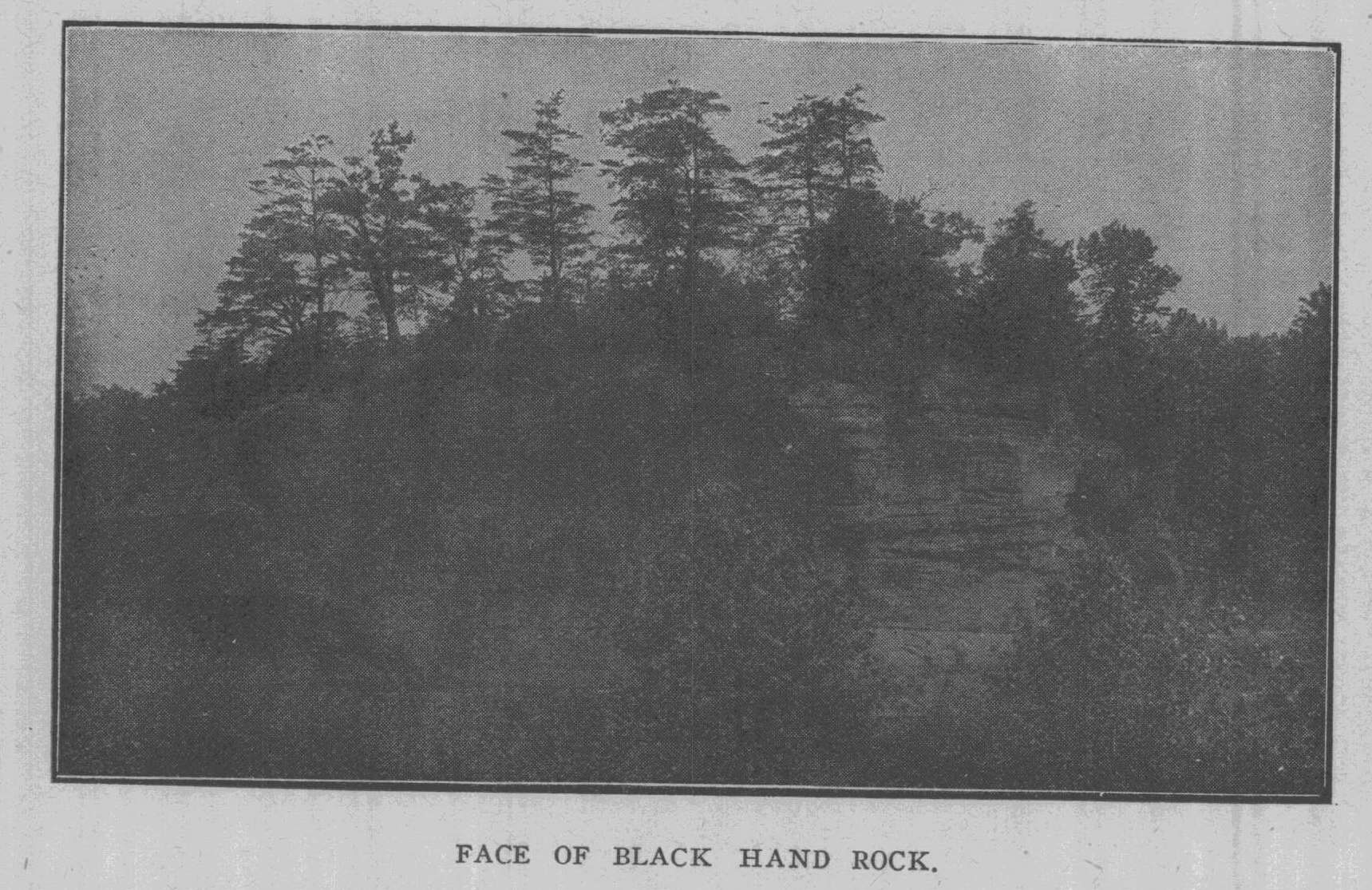

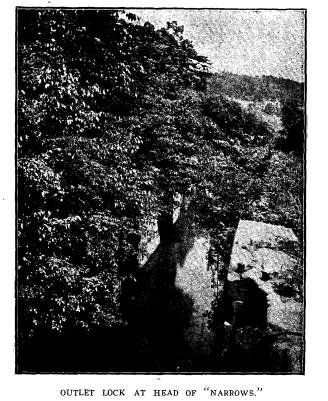

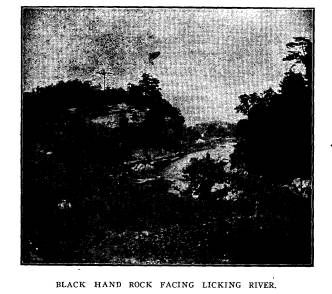

The pictures used for illustration are intended to show the massiveness of the Black Hand rock and give an idea of the ruggedness and picturesqueness of the Narrows and the peculiar change of channel, which makes so novel and interesting the po- sition of the rock itself. Two of the pictures were taken some years ago, while the dam was still standing, and the river was slack-water from the outlet lock at the head of the Narrows to the dam, which stood a short distance beyond the Black Hand. The remaining pictures were recently taken, while the river, no longer flooded by the dam, was at the stage of low water. Of the three pictures in which the Black Hand rock appears, one, |

|

|

|

taken from the Red Rock, looking west, shows the east entrance to the railroad cut opposite the Black Hand, the channel be- tween the cliffs and the river at the stage of slack water; another, taken from the railroad opposite, shows the face of the Black Hand rock, and its height in comparison with the dimly discern- ible figures standing on the towing-path across its face; the third picture looks eastward along the present channel of the river into the widening valley beyond. Now the dam is out much more of the rock is exposed to view, giving it a more massive appearance than in the older pictures. |

The Black Hand. 447

On the face of this isolated cliff the

earliest settlers found

engraved the figure of a large human

hand. Authorities differ

as to the size of the hand and the

direction in which it pointed.

The weight of evidence supports the

statement that it was twice

the normal size, with the thumb and

fingers distended and point-

ing to the east. It appeared to have

been cut into the face of

the rock with some sharp tool, and it is

probable that the form

became dark in time through natural

agencies. In 1828, when

the Ohio canal was under construction,

the river throughout the

extent of the narrows was converted into

slack-water and made

a part of the canal by constructing a

dam a few hundred yards

east of the Black Hand. It was necessary

to blast away part of

the Black Hand rock in order to make the

towing-path. In doing

so the Black Hand was removed. From the

earliest settlement

to the present, the origin and purpose

of the Black Hand have

been subjects of interesting conjecture,

and the effort to account

for them has given rise to many legends.

The Legends of the Black Hand.

These which follow have been written by

Dr. R. E. Cham-

bers, of Chandlersville, Mr. H. C.

Cochran, of near Newark,

Mrs. David Gebhart, of Dayton, and the

Hon. Alfred Kelley, of

Columbus.

In a paper by Colonel Charles

Whittlesey, entitled "Archaeo-

logical Frauds," he locates the

mound, from which the Moses or

Commandment Stone was said by David

Wyrick to have been

taken, two miles east of Jacktown and

south of the National road.

Residents of Newark who knew David

Wyrick personally, and

are familiar with all the facts assure

me that this is correct. In

the valley cast of the Red Rock, and a

few hundred yards dis-

tant, is a circle about two hundred feet

in diameter, with an

opening to the northeast, and with a

small mound in the center.

Southwest from the circle, near the

river, is evidence of a fire-

pit. Old residents tell me that

arrow-heads and flint chips were

formerly abundant in and about this circle. These, aside from

the figure of the hand, are the only

evidences of Indians, Mound

Builders, or other prehistoric

inhabitants in the neighborhood

of the Black Hand. The

statement of these facts, I hope, will

|

448 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

not lessen the interest of the reader in Dr. Chambers' entertain- ing effort to account for the Black Hand. In concluding his legend, Mr. Cochran says: "The name Black Hand still clings to the locality notwithstanding the vil- lage of that name has been renamed by the Post-office Depart- |

|

|

|

ment to the prosaic one of Toboso. All of the history and ro- mance and beauty of the locality, however, suggest Black Hand as the name of both village and community. The brakeman on the passenger train calls it Black Hand; if a stranger toiling along the country road asks a native the way to Toboso, he will invariably be directed on the way to Black Hand." It will |

The Black Hand. 449

doubtless be a matter of regret to

everyone that the railroad

has recently changed the name of the

station, and the brakeman

no longer calls out Black Hand, but

Toboso. It is to be hoped

that commercial as well as historic

interest will induce the new

electric line to perpetuate the name of

Black Hand.

In a beautiful introduction to her

legend, among other

things, Mrs. Gebhart says: "The

Indian legend pertaining to this

relic of a prehistoric race was told me

by Colonel Robert David-

son, who settled in Newark in 1808.

There were many Indians

there at that time, and from them he

doubtless heard it. They

lingered long in the vicinity. I

remember being carried in his

arms, probably about 1835, to see the

party who had erected

their wigwams and camped in the public

square at Newark. I

remember with especial distinctness, one

squaw who carried a

papoose, Indian fashion, on her

back. Its black bead-like

eyes seemed to view me as curiously as I

on my part viewed it

from that coign of vantage a father's

protecting arm."

Hon. Alfred Kelly was one of the canal

commissioners under

whose supervision the canals of Ohio

were made. He probably

heard the legend while engaged in this

work. His rendering

has never been published. A manuscript

copy is in the pos-

session of his daughter, Mrs. Francis

Collins, of Columbus, who

has kindly consented to its publication

here.

THE BLACK HAND.

R. E. CHAMBERS, M. D.

Some time during the fifties, articles

appeared from time to

time under the nom-de-plume of

"Black Hand." These were

devoted to a history of the "boys

and girls of 1826." They were

pleasing and readable, and were very

lavish in extolling the at-

tractive traits of character that

adorned the developing woman-

hood and manhood of that period.

At the conclusion of his article he asks

the question, "Who

put that hand on the rock ?" or who

painted the hand on the rock?

- for it had the appearance of having

been painted.

Vol. XIII-29.

|

450 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

This rock is near the station on the B. & O. railroad which bears the name, "Black Hand." It is on the canal bank on the borders of Muskingum county and Licking county and was a place of much note as a pleasure resort in my boyhood days. It was a large rock with a face some eight feet high with a pro- |

|

|

|

jecting rock of some feet out and even over the canal. This hand was perfect and Mr. Sheward, who had taken much pains to see if he could find its origin, traced its history back to 1816, and the first traveler found this hand on the rock. The Indians did not use the open hand as an insignia to convey or perpetuate events, hence they could not account for the hand. |

The Black Hand. 451

To give what I thought was the best

solution to a question

of so much interest, I was disposed to

use the find of David Wy-

rick and a friend, who had taken

advantage of a removal of a

large mound for the stone and dirt it

contained by the B. & 0.

railroad, a work of our prehistoric

citizens of a time we know

not of. David Wyrick and his friend, who

had been deeply inter-

ested in this mound in the years past,

and as to what it might con-

tain, determined to explore to a greater

depth than the removal

of the accumulations by the railroad.

They were not long in striking a rock in

their descent and

finding it was single and elongated

continued their work until

they uncovered it. They found the top

was of the character of a

slab, which on removal revealed the

skeleton of what was once

a human being. While decomposition had

been perfect, the mould

of the covering over the remains gave

evidence of fibers as if

the body had been clothed with a woolen

garment. They re-

moved the stone coffin and found beneath

it a stone of a foot

and a half in length, that gave evidence

of having been sharpened

and upon handling it they found that it

contained something

in its interior. They, with some

trouble, opened it, finding in-

side a stone twelve inches long and four

inches wide and an inch

in thickness. It had a neck broken off,

in the end was a hole. This

gave evidence of having been worn as if

a strap had been inserted

and it was carried in this way.

They were much astonished to find

engraved on one side an

outline or profile of a man in the dress

of a Hebrew and on the

other side characters which they could

not make anything out

of. Living in Newark, and having

knowledge of the Episcopal

minister as a man of fine education,

they went with it to him,

and he took the stone and was greatly

astonished to find that the

characters were Hebrew. He said he would

see if he could read

or decipher it. He did so. Calling to

his aid his Hebrew works,

he was able to translate nine

commandments, one was left off.

Fearing that his translation was not

correct, and having

a knowledge of Rev. Matthew Miller, of

Monroe township, this

county, who was at that time at his home

from New York, where

he had been laboring in his efforts to

convert the Jews, and

|

452 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

knowing that he was greatly distinguished as a Hebrew scholar, he wrote to him of the find, asking his assistance. His deep interest in that people caused his immediate trip to Newark. One of the letters or characters was not closed at the top, and for fear that he should be mistaken in view of this character, he went to Cincinnati to a Hebrew rabbi, and pre- sented to him the tablet. His translation was the same as that of the two other ministers. His attention being called to this var- |

|

|

|

iation in the letter, he said: "This is ancient Hebrew that you know nothing about." Rev. Matthew Miller said to me that the dating on this tablet ante-dated the birth of Christ eight thousand years. This hand pointed to the mound that contained the last rabbi who ministered at the altar. Doubtless when his work was done his followers gave a burial that went to show their love and esteem, in the mound they raised over his remains and the |

The Black Hand. 453

tablet, that was as a guide to their

faith, and then put the hand

on the rock, pointing to the place of

his burial.

THE MINGO CAPTIVE AND THE WYANDOT MAIDEN

AND

THE NEUTRAL GROUND.

H. C. COCHRAN.

An Indian sat at the door of a settler's

cabin and told this

story: Many years ago the red men in the

eastern part of the

state were at war with those in the

middle and northwestern part.

Chief among the former were the Mingos,

and among the latter,

the Wyandots. In one of the stealthy and

bloody incursions

into the Mingo hunting grounds, a young

chief of great promise

was captured and carried back by the

Wyandots. Instead of kill-

ing the young Mingo chieftain, as was

the usual custom, he was

made a serf and compelled to earn the

good-esteem and fellow-

ship of his captors, a fate worse than

death to the young Indian.

The woes of his captivity, however, were

lightened by the kindly

attention of a young Wyandot maiden, the

daughter of the chief

of the tribe into which the Mingo had

been adopted. Genuine af-

fection knows no condition, or it rises

above all environment. The

maiden fell in love with the unfortnate

young chief, and though

watched by the crafty tribesmen, they

made their affection known

to each other and decided to fly to the

Mingo country. One

night they made their escape. At

daylight they were missed

and were pursued by a posse of Wyandots.

The girl had left

behind a tribesman lover, who burning

with the passion of a

disappointed lover, and aching for

vengeance traveled faster

than the couple and overtook them at

Black Hand rock. They

heard the pursuers behind them, knowing

that worse than death

awaited them if captured. With the

stoicism of the savage, they

walked to the edge of the precipice and

surveyed the flood. Fold-

ing the idol of his heart in his arms,

he sprang into the boiling

waters. The pursuers were close enough

to see the last chapter

of the drama. The narrator says the

disappointed pursuers

marked the spot as the Caucasian found

it.

The other legend, one worthy of

perpetuity, is born of the

geology of the country and the trade

conditions of the aboriginees.

|

454 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

About five miles southwest of Black Hand is a great outcrop- ping of chalcedony. The place is known now as "Flint Ridge" and the flint, rare on this continent, was much valued by the In- dians and Mound Builders for making implements of agriculture and war. Like the pipe stone quarries of the Dakotas, where the inimical Sioux and Mandan work side by side in apparent peace, hither the tribes came up, the place being considered sacred to the giver of all good and perfect gifts. For a radius of |

|

|

|

five miles around "Flint Ridge," rested the blessing of the Great Spirit, or that of the orb of day, the divinity worshipped by the Mound Builders. None of the tumult of war was found within that space. Parties in quest of flint, coming to the confines of the charmed circle, laid down their arms for the purpose of mining the necessary stone, for the time forgetting the tradi- tionary hatred of foes. They came from the Mississippi valley, probably by water and debarked from their frail craft at the foot of the rock. The romancer says the spread hand carved on |

The Black Hand. 455

the rock was in mute appeal and forcibly

reminded the wayfarer in

a way at once forcible, as it was

poetical, that thus far and no

farther should the waves of unglutted

vengeance roll. The hand

marked the portal of a sanctuary which

was sacred to the

savage, whose lust for blood rose above

every other considera-

tion in his narrow but intense, isolated

but eventful life.

THE CHIEFTAIN WACOUSTA, THE YOUNG

LAHKOPIS, AND

THE MAIDEN AHYOMAH.

MRS. DAVID GEBHART.

"An unremembered Past

Broods like a presence, midst

These cliffs and hills."

Many moons ago, long before the pale

face came across

the Great Water to this land, here upon

the bank of the Pataskala,

was the lodge of the great chief

Powkongah, whose daughter

Ahyomah was fair as the dawn and

graceful as the swan that

floats on the lake. Her eyes were soft

and shy as the eyes of a

young deer, her voice sweet and low as

the note of the cooing

dove. Two braves were there who looked

upon her with eyes of

love, and each was fain to lead her from

the lodge of her father,

that she might bring light and joy and

contentment to his own.

At last said the chief, her father,

"No longer shall ye contend for

the hand of Ahyomah, my daughter. Go ye

now forth upon the

war path, and when three moons have

passed see that ye come

hither once more, and then I swear by

the Great Spirit that to

him who shall carry at his belt the

greatest number of scalps

shall be given the hand of Ahyomah, my

daughter." Three

months had waxed greater and grown less

ere the warriors re-

turned. Then, upon the day appointed,

behold, all the tribe gath-

ered to view the counting of the scalps.

First stepped forth Wa-

cousta, a grim visaged warrior, who had

long parted company

with fleet-footed youth, and walked

soberly with middle man-

hood. From his belt he took his

trophies, one by one, and laid

them at the feet of the chief, while

from behind the lodge door

Ahyomah, unseen by all, looked fearfully

forth upon the scene.

With each fresh scalp the clouds settled

more and more darkly

|

456 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

upon the bright face of Ahyomah, and her lip trembled as she murmured, "So many! so many!" Then came the second brave, Lahkopis. Young was he, with the light of boyhood still lingering in his eyes, but upon his head the eagle feather, telling withal of a strong arm and deeds of bravery. One swift glance he shot towards the lodge of the unseen maiden, then he loosed his belt, and laid it at the feet of Powkongah. Scalp after scalp they counted, while the people bent forward silently, and a little hand drew aside the curtain from the lodge doorway, and a young |

|

|

|

face looked anxiously yet hopefully forth. Slowly, slowly they laid them down, and at last, behold there was one more, just one more than in the pile of Wacousta. The young Lahkopis had won! Now strode forth Wacousta, and laid his hand--the strong right hand, that yet had failed to win the prize--laid it upon a rock. Then lifted he his tomahawk high in the air, and with one swift stroke severed the hand at the wrist, and flung it high up against the face of the cliff, saying. "Stay thou there forever as a mark of scorn in the eyes of all men, thou hast let |

The Black Hand. 457

thyself be beaten by the cunning right

hand of a boy! Disgraced

thou art, and no longer shalt thou be

numbered among the

members of my frame." And the hand

clung to the rock and

turned black, and spread and grew until

it was as the hand of

a giant; and while the chief, Ahyomah

and the tribe stood silently

watching the wonder, the defeated

warrior wrapped his robe

about him, spoke no word of farewell,

and striding swiftly into

the dark depths of the forest, was seen

no more by man.

THE BLACK HAND.

HON. ALFRED KELLEY.

Have you ever seen the place where the

murderer's hand

Had instamped on the rock its indelible

brand,

A stain which nor water nor time could

efface?

'Tis a deep lonely glen, 'tis a wild

gloomy place,

Where the waters of Licking so silently

lave,

Where the huge frowning rock high

impends o'er the wave,

On whose pine-covered summit we hear the

deep sigh

When the zephyrs of evening so gently

pass by.

Here a generous savage was once doomed

to bleed,

'Twas the treacherous white man

committed the deed.

The hand of the murderer fixed the

imprint,

'Twas the blood of the victim that gave

the black tint.

A captive in battle the white man was

made,

And deep in the wilds is the victim

conveyed,

Here far from his kindred the youth must

be slain,

His prayers, his entreaties, his

struggles are vain.

The war dance is treading, his death

song is singing,

And the wild savage yell in his ears is

a-ringing.

The fire for the torture is blazing on

high,

His death doom is sealed, here the white

man must die,

The hatchet is raised, the weapon

descends,

But quick an old chief o'er the victim

now bends.

The hatchet he seizes and hurls to the

ground.

He raises the youth and his limbs are

unbound.

"My son fell in battle,"

exclaims the old chief,

"But ye saw not my sorrow, tho'

deep was my grief,

458

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

And now shall the white man to me be a

son,

'Tis your chief that has said it - his

will shall be done.

A friend and a father to him will I

prove,

And me as a father and friend shall he

love."

Long years had passed by, and peace had

again

Spread her soft balmy wings over

mountain and plain,

The red man and white man in friendship

now meet,

For the hatchet is buried deep under

their feet.

Long years had rolled on, while the

chief and his son

Rich spoils from the forest together had

won.

Now loaded with furs from the far

distant lake,

The path to the traders together they

take.

Through the Narrows of Licink their

pathway extends,

Around the huge rock on its margin it

bends,

Where the shelf on its face scarce

admits them to creep

Along the dark front that impends o'er

the deep.

The chief, with fatigue and with age now

oppressed,

In the shade of the rock seeks a moment

of rest;

Here, lulled by the waters, he closes

his eyes,

While his spirit communes with his

friends in the skies.

By his side the false white man now

silently knelt,

And carefully drawing his knife from the

belt,

With one deadly plunge of the murderous

steel

Reached the heart full of kindness -a

heart that could feel.

Then quick in the river the Indian was

thrown

Lest the tale should be told, lest the

deed should be known.

Oh! the shriek that he gave as he sank

in the flood,

As the waves eddied round him,

deep-stained with his blood.

0h! the glare of his eye as they closed

o'er his head,

While with hoarse sullen murmur they

welcomed the dead.

Rock told it to rock, oft repeating the

sound,

While shore answering shore still

prolonged it around.

That look and that sound touched the

murderer's heart,

With phrenzy he reeled, and with

shuddering start,

His hand, while still reeking, with

madness he placed

On the rock, and the blood-stain could

ne'er be effaced.

|

The Black Hand. 459

'Twas avarice prompted the horrible deed, 'Twas avarice doomed the kind chieftain to bleed. To form the safe towing-path, long since that day The face of the rock had been blasted away. Now the gay painted boat glides so smoothly along, Its deck crowned with beauty and cheerful with song. And the print of the black hand no longer is seen, But the pine-covered summit is still evergreen, And still through the branches we hear the deep sigh Of the spirits of air as they sadly pass by, While in mournful procession they move one by one Still thinking with grief on the deed that was done. |

|

|

|

THE BLACK HAND.

JOHN D. II. M KINLEY. The Licking river, the Pataskala of the Indians, as it draws near the eastern boundary of Licking county, Ohio, flows in a winding course for a distance of about two miles through a nar- row and picturesque sandstone gorge, known as the Licking Narrows. High hills border upon both banks, their rocky sides |

|

|

|

exposed in many places to a height of fifty to sixty feet, almost continuously on the north bank, and often rising out of the bed of the stream. Just at the eastern end of the Narrows the river flows in its narrowest channel between twin cliffs. That on the south side has been quarried and boated way, so that it no longer shows the extent of the face originally presented to the stream, though enough remains to give an idea of its former height. That on the north side is isolated, with a surface area on its (444) |

(614) 297-2300