Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

TARHE-THE CRANE

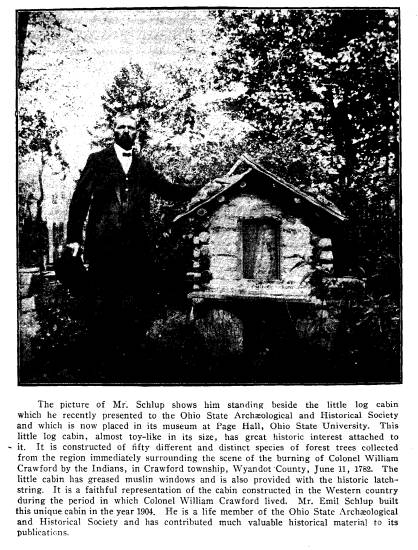

EMIL SCHLUP, UPPER SANDUSKY.

Probably no other Indian chieftain was

ever more admired

and loved by his own race or by the

outside world. He was

either a true friend or a true enemy.

Born near Detroit, Michi-

gan, in 1742, he lived to see a

wonderful change in the great

Northwest. Being born of humble

parentage, through his brav-

ery and perseverence, he rose to be the

grand sachem of the Wy-

andot nation. This position he held

until the time of his death,

when he was succeeded by Duonquot. Born

of the Porcupine

clan of the Wyandots and early

manifesting a warlike spirit, and

was engaged in nearly all the battles

against the Americans until

the disastrous battle of Fallen Timbers,

in 1794. Tarhe saw that

there was no use opposing the American

arms, or trying to pre-

vent them planting corn north of the

Ohio river. At that disas-

trous battle, thirteen chiefs fell and

among the number was Tarhe,

who was badly wounded in the arm. The

American generally

believed that the dead Indian was the

best Indian, but Tarhe sadly

saw his ranks depleted, and at once

began to sue for peace. Gen-

eral Wayne had severely chastised the

Indians, and forever broke

their power in Ohio. Accordingly, on

January 24, 1795, the

principal chiefs of the Wyandots,

Delawares, Chippewas, Otto-

was, Sacs, Pottowattomies, Miamis, and

Shawnees met. The

preliminary treaty with General Wayne at

Greenville, Ohio, in

which there was an armistice, was the

forerunner of the celebrated

treaty which was concluded at the same

place on August 3, 1795.

A great deal of opposition was

manifested to this treaty by the

more warlike and turbulent chiefs, as

this would cut off their

forays on the border settlements.

Chief Tarhe always lived true to the

treaty obligations which

he so earnestly labored to bring about.

When Tecumseh sought

a great Indian uprising, Tarhe opposed

it, and awakened quite

an enmity among the warlike of his own

tribe, who afterward

(132)

|

Tarhe-The Crane. 133 withdrew from the main body of the Wyandots and moved to Canada. The Rev. James B. Finley had every confidence in Tarhe, as evidenced in 1800, when returning from taking a drove |

|

|

of cattle to the Detroit mar- ket, he asked Tarhe for a night's lodging at Lower San- dusky, where the Wyandot chief then lived, and intrusted him with quite a sum of money from the sale of cattle, and the next morning every cent was forthcoming. From 1808 until the War of 1812, Tarhe steadily op- posed Tecumseh's treacherous war policy, which greatly en- dangered Tarhe's life, and it is claimed he came near meet- ing the same fate that Leather |

|

Lips met on June 1, 1810. He even went so far as to offer his services with fifty other chiefs and warriors to General Harrison in prosecuting the war against Tecumseh and the Eng- lish under General Proctor. He was actively engaged in the battle on the Thames. So earnest was he in the success of the American cause, so sincere did he keep all treaty obligations, that General Harrison in after years, in comparing him with other chiefs, was constrained to call him "The most noble Roman of them all." Tarhe never drank strong drinks of any kind, nor used to- bacco in any form. Fighting at the head of his warriors in Har- rison's campaign in Canada, at the age of seventy-two years, is something out of the ordinary. Being tall and slender, he was nicknamed "The Crane." On his retiring from the second war for Independence, he again took up his abode in his favorite town -the spot is still called "Crane Town," about four and one- half miles northeast from Upper Sandusky, on the east bank of the Crane run, which empties into the Sandusky river. Here surrounded by a dense forest, he spent his old age in a log cabin, |

134 Ohio

Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

fourteen by eighteen feet. Just south of

the old cabin site are a

number of old apple trees, likely of the

Johnny Appleseed origin-

the fruit being small and hard; a short

distance south of the cabin

is the old gauntlet ground, oblong and

about three hundred yards

long; to the westward from the village

site, is a clearing of about

ten acres, still known as the Indian

field, and still surrounded by a

dense forest. Here Tarhe died in his log

cabin home, in Novem-

ber, 1818. In 1850, John Smith, then

owner of the land, had most

all of the cabin taken down for

fire-wood. At that time a small

black walnut twig, about the thickness

of a man's thumb, was

growing in the northwest corner of the

cabin, and is quite a tree

at the present writing -a

living and growing monument to the

memory of the great and good Wyandot

chief.

Aunt Sally Frost was Tarhe's wife when

he died. To them

one child was born, an idiotic son who

died at the age of twenty-

five years. Sally had been a captive

from one of the border settle-

ments, and refused to return to her

people. After the death and

burial of Tarhe, the principal part of

Crane Town was moved to

Upper Sandusky, the center of the

Wyandot reservation twelve

miles square. Herethe government at

Washington paid them an

annuity of ten dollars per capita until

the reservation reverted

back to the government in March, 1842.

Cabin sites are plainly discernable in

the old historic town,

which was usually a half-way place

between Fort Pitt and De-

troit. Here in the early days Indian

parties found a resting place

when on their murderous missions to the

border settlements.

This was one of the

"troublesome" Indian towns on the Sandusky

river that the ill-fated Col. Wm.

Crawford was directed against

in the Spring of 1782. Traces of the old

Indian trail may be

seen meandering southward through the

forest, where the war-

whoop was frequently given and the

bloody scalping knife drawn

over many defenseless prisoners. The

springs, just westward

from the town site, are cattle tramped,

but still bubble forth a

small quantity of water, but likely not

nearly so active as when

they furnished the necessary water for

the nations of the forest

a century and more ago.

On June 11, 1902, Mr. E. O.

Randall, the able and efficient

Secretary of the Ohio State

Archaeological and Historical Society,

Tarhe- The Crane. 135

in company with the writer, gave the

place a visit. Numerous

locusts were chirping away at their

familiar songs, quite loud

enough to drown out the voices of the

intruders.

Jonathan Pointer, who had been a colored

captive among the

Wyandots and who was a fellow soldier

with Tarhe in the Can-

adian campaign under General Harrison,

returned with that cele-

brated chieftain to his home and stayed

with him until the time

of Tarhe's death, always claiming that

he assisted in the burial

of Tarhe on the John Smith farm, about a

half mile southeast

from his cabin home. Logs were dragged

over the grave to keep

the wild animals from disinterring the

body. Jonathan Pointer

was engaged as interpreter for the early

missionaries among the

Wyandots; he died in 1857. No memorial

marks Tarhe's resting

place. Red Jacket, Keokuk, Leather Lips,

and other chieftains

have received monumental consideration

from American civiliza-

tion; but Tarhe, the one whose influence

and activity helped to

wrest the great Northwest from the

British and the Indians,

has apparently been forgotten. And how

long shall it be so?

Colonel John Johnson, who for nearly

half a century acted

Indian agent of the various tribes of

Ohio and who made the last

Indian treaty that removed the Wyandots

beyond the Mississippi,

was present at the great Indian council

summoned at the death

and for burial of Tarhe. The exact spot

where the council house

stood is not known, but a mile and a

half north from Crane town

site are a number of springs bubbling

forth clear water which form

Pointer's run, that empties into the

Sandusky river. They are

still called the Council Springs and the

bark council house was

likely in this vicinity. Colonel

Johnson, in his "Recollections,"

gives the following account of the

proceedings:

"On the death of the great chief of

the Wyandots, I was invited

to attend a general council of all the

tribes of Ohio, the Delawares of

Indiana, the Senecas of New York, at

Upper Sandusky. I found on arriv-

ing at the place a very large

attendance. Among the chieftains was the

noted leader and orator Red Jacket from

Buffalo. The first business

done was the speaker of the nation

delivering an oration on the character

of the deceased chief. Then followed

what might be called a monody,

or ceremony, of mourning or lamentation.

Thus seats were arranged

from end to end of a large council

house, about six feet apart, the

head men and the aged took their seats

facing each other, stooping down,

136 Ohio Arch. and

Hist. Society Publications.

their heads almost touching. In that

position they remained for several

hours. Deep and long continued groans

would commence at one end of

the row of mourners, and so pass around

until all had responded, and

these repeated at intervals of a few

minutes. The Indians were all

washed, and had no paint or decorations

of any kind upon their persons,

their countenances and general

deportment denoting the deepest mourn-

ing. I had never witnessed anything of

the kind before, and was told

that this ceremony was not performed but

on the decease of some great

man. After the period of mourning and

lamentation was over, the In-

dians proceeded to business. There were

present the Wyandots, Shaw-

nees, Delawares, Senecas, Ottawas and

Mohawks. Their business was

entirely confined to their own affairs,

and the main topics related to

their lands, and the claims of the

respective tribes. It was evident,

in the course of the discussion, that

the presence of myself and people

(there were some white men with me) was

not acceptable to some of

the parties, and allusions were made so

direct to myself that I was

constrained to notice them, by saying

that I came there as a guest of

the Wyandots, by their special

invitation; that as the Agent of the

United States, I had a right to be there

as anywhere else in the Indian

country; and that if any insult was

offered to myself or my people,

it would be resented and punished. Red

Jacket was the principal speaker,

and was intemperate and personal in his

remarks. Accusations, pro and

con, were made by the different parties,

accusing each other of being

foremost in selling land to the United

States. The Shawnees were par-

ticularly marked out as more guilty than

any other; that they were

the last coming into the Ohio country

and although they had no right

but by the permission of the other

tribes, they were always the foremost

in selling lands. This brought the

Shawnees out, who retorted through

head chief, the Black Hoof, on the

Senecas and Wyandots with pointed

severity. The discussion was long

continued, calling out some of the

ablest speakers, and was distinguished

for ability, cutting sarcasm and

research, going far back into the

history of the natives, their wars, alli-

ances, negotiations, migrations,

etc. I had attended many councils,

treaties, and gatherings of the Indians,

but never in my life did I witness

such an outpouring of native oratory and

eloquence, of severe rebuke,

taunting national and personal

reproaches. The council broke up later in

great confusion and in the worst

possible feeling. A circumstance

occurred toward the close which more

than anything else exhibited

the bad feeling prevailing. In handing

round the wampum belt, the

emblem of amity, peace and good will,

when presented to one of the

chiefs, he would not touch it with his

fingers, but passed it on a stick

to a person next to him. A greater

indignity, agreeable to Indian eti-

quette could not be offered.

The next day appeared to be one of

unusual anxiety and despondence

among the Indians. They could be seen in

groups everywhere near the

council house in deep consultation. They

had acted foolishly-were

|

Tarhe -The Crane. 137 sorry -but the difficulty was, who would present the olive branch. The council convened very late, and was very full; silence prevailed for a long time; at last the aged chieftain of the Shawnees, the Black Hoof, rose- a man of great influence and a celebrated warrior. He told the assembly that they had acted like children, and not men yesterday; that |

|

|

|

138 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications. he and his people were sorry for the words that had been spoken, and which had done so much harm; that he came into the council by the unanimous desire of his people, to recall those foolish words, and did there take them back-handing round strings of wampum, which passed around and were received by all with the greatest satisfaction. Several of the principal chiefs delivered speeches to the same effect, handing round wampum in turn, and in this manner the whole difficulty of the preceding day was settled, and to all appearances forgotten. The In- dians are very civil and courteous to each other and it is a rare thing to see their assemblies disturbed by unwise or ill-timed remarks. I never witnessed it except upon the occasion here alluded to, and it is more than probable that the presence of myself and other white men con- tributed towards the unpleasant ocurrence. I could not help but admire the genuine philosophy and good sense displayed by men whom we call savages, in the transaction of their public business, and how much we might profit in the halls of our Legislatures, by occasionally taking for our example the proceedings of the great Indian council at Upper San- dusky.39 |

|

|

TARHE-THE CRANE

EMIL SCHLUP, UPPER SANDUSKY.

Probably no other Indian chieftain was

ever more admired

and loved by his own race or by the

outside world. He was

either a true friend or a true enemy.

Born near Detroit, Michi-

gan, in 1742, he lived to see a

wonderful change in the great

Northwest. Being born of humble

parentage, through his brav-

ery and perseverence, he rose to be the

grand sachem of the Wy-

andot nation. This position he held

until the time of his death,

when he was succeeded by Duonquot. Born

of the Porcupine

clan of the Wyandots and early

manifesting a warlike spirit, and

was engaged in nearly all the battles

against the Americans until

the disastrous battle of Fallen Timbers,

in 1794. Tarhe saw that

there was no use opposing the American

arms, or trying to pre-

vent them planting corn north of the

Ohio river. At that disas-

trous battle, thirteen chiefs fell and

among the number was Tarhe,

who was badly wounded in the arm. The

American generally

believed that the dead Indian was the

best Indian, but Tarhe sadly

saw his ranks depleted, and at once

began to sue for peace. Gen-

eral Wayne had severely chastised the

Indians, and forever broke

their power in Ohio. Accordingly, on

January 24, 1795, the

principal chiefs of the Wyandots,

Delawares, Chippewas, Otto-

was, Sacs, Pottowattomies, Miamis, and

Shawnees met. The

preliminary treaty with General Wayne at

Greenville, Ohio, in

which there was an armistice, was the

forerunner of the celebrated

treaty which was concluded at the same

place on August 3, 1795.

A great deal of opposition was

manifested to this treaty by the

more warlike and turbulent chiefs, as

this would cut off their

forays on the border settlements.

Chief Tarhe always lived true to the

treaty obligations which

he so earnestly labored to bring about.

When Tecumseh sought

a great Indian uprising, Tarhe opposed

it, and awakened quite

an enmity among the warlike of his own

tribe, who afterward

(132)

(614) 297-2300