Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

- 34

- 35

- 36

- 37

- 38

- 39

- 40

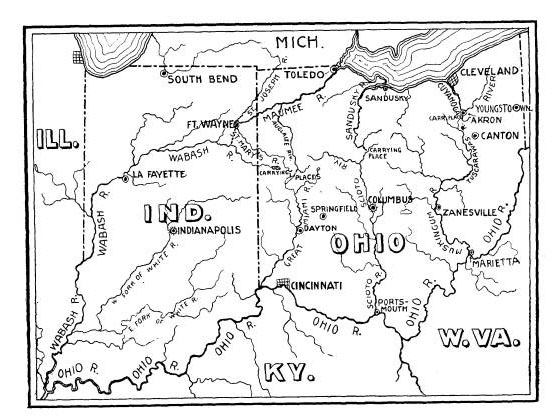

WATER HIGHWAYS AND

CARRYING PLACES.

E. L. TAYLOR, COLUMBUS.

The 2d day of May, 1497, was one of the

most eventful

for great results for good of any in

human history. On that

day, John Cabot, a Venetian by birth,

but who was then living

at the old sea-faring town of Bristol,

on the west coast of Eng-

land, with eighteen hardy British

sailors weighed anchor on the

small, but good ship

"Matthew," and passed out upon the broad

and turbulent waters of the Atlantic on

a voyage of discovery.

It is probable, but not certain, that

his son, Sebastian, accom-

panied him on this voyage. The adventure

was entirely at the

expense of Cabot. He had, however,

obtained from King Henry

VII., royal permission to carry the

British flag, and was com-

missioned to "seek out, discover

and find whatever lands, coun-

tries, regions or provinces of the

heathens or infidels, in what-

ever part of the world they may be which

before this time have

been unknown to all Christians."

Further, he was required, if he should

be so fortunate as

to return, to report at the port of

Bristol and to "take a fifth

part of the whole capital, whether in

goods or money for our

use." The return was made in the

following August, but with-

out "goods or money," and with

nothing but a vague report that

they had discovered land in the north

Atlantic, hitherto unknown

to the civilized world.

All that could be reported of the voyage

was that after

leaving the port of Bristol, the vessel

held her way to the west-

ward, and late in June they came in

sight of land, and after sailing

some leagues to the south along the

coast, they went ashore and

so were the first Europeans to set foot

on the continent of North

America. They had no thought that they

were standing upon

the shore of a great and hitherto

unknown continent, or that their

discovery of land in these far off

waters was, or would become

(356)

Water Highways and Carrying

Places. 357

of any special importance or

significance. They were not look-

ing for a new continent, but were hoping

to reach the east coast

of Asia, known in Europe since the time

of Marco Polo, as

"Cathay." Cabot did not live

to know that he had discovered

a great new continent, which was then

and had been for many

thousands of years occupied by a race or

races of savages, whose

energies had been spent in the hunt of

wild beasts and in waging

war upon each other, which wars between

savage tribes and

nations were wars of extermination in so

far as they could make

them.

CABOT.

The place of Cabot's landing has not

been definitely deter-

mined and probably never can be, but a

committee appointed by

the Royal Geographical Society of

Canada, reported in 1895,

that the weight of evidence is that it

was on Cape Breton, which

is on the extreme north east coast of

the Province of Nova

Scotia. At the place of their landing

they found no human

inhabitants, but did find snares and

devices for taking fish and

game, which were evidently designed by

human minds and

wraught out by human hands. But wherever

it was, they seem

to have unfurled and planted the British

flag and made some

kind of proclamation to the effect that

they took possession of

the land in the name of the King of

Great Britain. Nothing

could seem to be more idle or

meaningless than this proclamation

or outcry to the winds and waves of this

unknown, desolate

rock-bound coast, and yet it became in

time to be the basis of

whatever title Great Britain had to the

continent of North

America.

After Cabot, numerous explorers came to

our shores, but

they seem to have been satisfied with

coasting along the shores

with no purpose or effort to penetrate

the interior, or learn what

lay hidden behind the desolate coast

line. It was not until 1534

that the mouth of the St. Lawrence River

was discovered by

Jacques Cartier, and it was not until

the next year (1535) that

any successful attempt was made to

explore the interior of the

northern portion of the continent to

which the St. Lawrence

was the great highway.

358 Ohio Arch. and Hist.

Society Publications.

JACQUES CARTIER.

In that year (1535) Jacques Cartier, a

French navigator,

ascended the St. Lawrence to the point

of the present site of

Montreal. The great Lachine rapids

prevented further progress.

This was thirty-eight years after

Cabot's discovery of the coast,

during which time no special effort

seems to have been made

by English or other European navigators

to penetrate the interior

of the northern portion of the

continent, or to learn anything

of its nature or conditions. This

inaction was in strange con-

trast with the activity of the Spaniards

in their enterprises far-

ther to the the south. It was some

fifteen years after Cabot's

discovery that the Spaniards first saw

or set foot on the North

American continent, and yet before

Cartier's discovery of the

St. Lawrence, they had overrun and

conquered Mexico, and

Peru; and it was but four years later

that De Soto penetrated

Louisiana, Alabama, Georgia,

Mississippi, Missouri and Arkan-

sas, and in 1642 wearied, worn and

exhausted from three years

of wide and fruitless wanderings in

search of gold and treasures,

died on the banks of the Mississippi and

was buried beneath its

turbid waters. But it is stranger still

that the matter of interior

exploration was allowed to rest with

nothing added to the geo-

graphical information of the interior,

beyond Cartier's exploits

for the long period of sixty-eight

years.

It was not until 1603 that Champlain

appeared upon the

scene, filled with the spirit of adventure

and discovery, and deter-

mined to penetrate the recesses of the

vast and gloomy wilderness

and bring to light the secrets it had

held hidden for so many

ages.

CHAMPLAIN.

Samuel Champlain, a French navigator,

sailed up the St.

Lawrence in 1603 and reached the point

(Montreal) where Car-

tier had stopped sixty-eight years

before. He was a most am-

bitious and self-reliant man, capable of

great efforts and of won-

derful endurance. He was not then

equipped for further ex-

plorations, but resolved that he would

return at the earliest time

possible and explore the depths of the

vast and gloomy forest

Water Highways and Carrying

Places. 359

that stretched out before him in every

direction as he stood on

the top of Mount Real and viewed the

wondrous scene as Car-

tier had done in 1535: It was five years

before he could carry

out his purpose, but in 1608 he

re-appeared on the St. Lawrence

equipped not only for explorations, but

for the founding of a

colony in the new world. On the vessel

with him came a "French

lad" then about eighteen years of

age, Stephen Brule, destined

to become the greatest interior explorer

of his time and to lead

a most singular and strenuous life and

end with a most tragic

death.

When Champlain reached the site of the

present city of

Quebec, he determined that there he

would found his colony and

so proceeded to clear the space between

the river bank and the

stupendous cliffs upon which the City of

Quebec now stands,

and to erect log houses, where he

proposed to spend the winter

before proceeding with his intended

explorations. Brule assisted

in this work and so became one of the

founders of the City of

Quebec, now the most interesting,

historically considered, of any

city on the continent.

The winter was exceedingly severe and

the colony suffered

greatly, but the spring brought relief

and Champlain, having

made an alliance with the Hurons and

Algonquins, set out for

the Iroquois country, which was what is

now embraced in the

State of New York. The Iroquois were the

fiercest and most

war-like of all the tribes known, and

after they had been sup-

plied with fire arms by the Hollanders

and English, they carried

their war expeditions from the coast of

New England to the

Mississippi and from the extreme of the

northern lakes, and to

Virginia and the Carolinas. They swept

from Ohio the Eries,

one of their own tribe, and all other

tribes having before that

time had occupancy within the borders of

the states of Pennsyl-

vania, Ohio, Indiana and most of

Illinois. Those wide and sav-

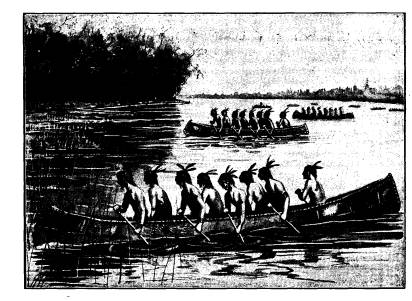

age excursions and campaigns could only

be carried on by means

of the "water-ways" which were

connected by "carrying places,"

by the French called

"portages."

It is the purpose of this paper to set

out as accurately as

we can, the main thoroughfares which

were traveled by the

Aborigines in their savage forays, and

by whom they were first

|

360 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications. seen and traversed by white men. Miss Lucy Elliot Keeler has aptly denominated these highways as "the roads that run." Champlain had learned from the Indians that there was an ample water-way from the St. Lawrence to the Atlantic at the present port of New York and the intention was to ascend the Richelieu, which is the outlet of the waters of Lakes George and Champlain, and by carrying their birch canoes from the head of those waters over the "carrying place" to reach the waters of |

|

|

|

Hudson River as they flowed down from the Adirondack Moun- tains, and so surprise and destroy the villages of the Iroquois in the Mohawk Valley. But the plan failed, as when near the head of Lake Champlain they unexpectedly met with a strong war party of the Iroquois when a battle ensued in which Cham- plain and his Indian allies were successful and vanquished their enemies with great slaughter. This was the first time that fire arms had been used in Indian warfare among the northern In- |

Water Highways and Carrying

Places. 361

dians, and the Iroquois were so

terrifiedby the noise and deadly

execution of fire arms in the hands of

the Frenchmen that they

fled in every direction and were pursued

and slaughtered in great

numbers by the savage allies of

Champlain. Soon after this

decisive battle, Champlain and his

Indian allies returned to the

St. Lawrence, from whence he sailed for

France, and the In-

dians returned to their own country. He

was, however, again

on the St. Lawrence the next spring

(1610) where he had engaged

to meet the Hurons and Algonquins near

the mouth of the Rich-

elieu River. Champlain arrived in

advance of his Indian allies,

and encamped awaiting their coming.

While waiting there, word

was received by him that the Hurons had

surrounded a barricade

of one hundred Iroquois, near the mouth

of the Richelieu, where

a desperate battle was being waged. He

and the Indians with

him hurried to the assistance of the

Hurons. The barricade was

stormed and all the warriors within were

killed or taken prisoners.

Not one escaped. After this battle

Champlain arranged to re-

turn to France but with the agreement to

return the next spring

(1611).

It was further arranged that the Hurons should take

the young man Brule to their far off

Huron country and that

Champlain was to take with him to France

a young Huron (Sav-

ignon), selected by his tribe for that

purpose. They were to

meet again in June, 1611, and

exchange hostages. This was

accordingly done.

In this year spent with the Hurons Brule

had acquired

their language and habits of life and

was able thereafter to act

as an interpreter for Champlain in his intercourse with the Hu-

rons and Algonquins both as to war and

trade.

Champlain made in all ten visits to the

St. Lawrence from

1603 to 1633, during which time he had

learned from the Indians

much concerning the lakes and rivers of

the north-west, but as

for himself he discovered or first saw no lakes or rivers of im-

portance except Lake Champlain and the

Richelieu River. He

wandered far and wide in many directions

but it cannot be claimed

for him that he was the original first white man to discover or

see any of these great natural highways

except as before men-

tioned. In all his wide wanderings, Brule

seemed to have been

in advance of him. Nevertheless. Champlain is entitled to the

362

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

credit, in large part at least, for

directing the discoveries made

by Brule.

Champlain has been frequently and

generally accredited with

being the first "white man" to

see the waters of Lake Ontario,

but this claim cannot be allowed, as it

is surely incorrect. In

fact, it can have no support, except

upon the assumption that the

explorations of Brule were the

explorations of Champlain.

In the month of September, 1615,

Champlain had concen-

trated his few Frenchmen and many

Indians of the Huron and

Algonquin tribes at Lake Simcoe in the

Huron country, with a

view of invading the country of the

Iroquois, but before the war-

riors had all assembled, Brule with

twelve Hurons was dispatched

to notify the Carantouans, who were

allies of the Hurons and

other Canadian tribes, and who had

promised to assist them in the

invasion of the Iroquois country.

Lake Simcoe is directly north from the

mouth of the Humber

river, near where the city of Toronto

now stands. It was but

three or at most four days' travel for

Brule and the Indians with

him to reach the upper or western end of

Lake Ontario and by

crossing that end of the lake they would

be within the Iroquois

country at or near the mouth of the Niagara

River; and so if

they were fortunate enough to escape the

fierce Iroquois, while

passing through their country, would

reach the Carantouan vil-

lages by the shortest and quickest route

possible.

The Carantouan Indians were at that time

living on the

upper waters of the Susquehanna in

northern Pennsylvania.

Brule and his Indian escorts reached the

Carantouan villages

without mishap or delay--and urged that

tribe, friendly to the

Canadian Indians and relentless enemies

of the Iroquois, to fur-

nish five hundred warriors, which they

had promised, to join

with Champlain and his allies in an

attack upon Onondaga village.

Brule set out from Lake Simcoe, directly

south, on the 8th

of September, 1615, and some days later,

Champlain with his

Indian allies started for the mouth of

the Trent River, which

is near where the city of Kingston,

Canada, now stands. Brule's

route took him direct to the mouth of

the Humber river (Toronto).

That they traveled with all speed and

haste may be assumed, as

their mission was to notify the

Carantouans to be present near

Water Highways and Carrying

Places. 363

the village of Onondaga by the time that

Champlain should reach

this important stronghold which was the

objective point of the

expedition. Champlain and his allies on

the other hand had a

much longer and more difficult route.

They were required to

take with them canoes for the entire

party so as to cross the

numerous streams and small lakes which

intervene between Lake

Simcoe and the mouth of the Trent River.

They were also re-

quired to stop at different times in

order to procure a supply of

game and fish for their sustenance.

Brule reached the Caran-

touan villages without hindrance or

delay, but the Indians were

slow in assembling, and with their

feasting and dancing always

incident to going to war much delay was

had and he was not

able to bring them to the point of

attack until Champlain and

his Canadian Indians had been repulsed

at the above named

village. Champlain's retreat was by the

same line by which he

came, and he finally reached the Huron

country where he was

compelled to spend the winter with them

on the shores of Lake

Huron (now called Georgian Bay).

"The roads that run" had

been congealed into ice and the thawing

suns of spring had to

be awaited.

Brule reached the mouth of the Humber

and stood upon the

banks of Lake Ontario many days, if not

weeks before Champlain

reached the mouth of the Trent River

near Kingston, from which

point he first viewed the waters of

Ontario. The route taken

by Brule with his Indian guides to Lake

Ontario was less than

half the distance of the route taken by

Champlain, and it is certain

that Brule not only saw Lake Ontario but

crossed it before Cham-

plain had reached the mouth of the Trent

river. Both Champlain

and Brule had long been familiar with

the fact that such a lake

existed but neither of them had before

that time seen its waters.

The best and shortest route from the

Huron country to Ontario

and the St. Lawrence was that which

Brule took to reach Lake

Ontario and thence along the north side

of that lake to its outlet,

and thence along the descending waters

of the St. Lawrence to

Montreal and Quebec. But in the time of

war between the In-

dians in Canada and the Iroquois this

route could not be used

except in such force as to be able to

contend with such parties

of hostile savages as might be met. This

is what caused the

|

364 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications. Hurons and Algonquins to adopt the long, difficult and cir- cuitous route of the Ottawa, Lake Nipissin and the French River |

|

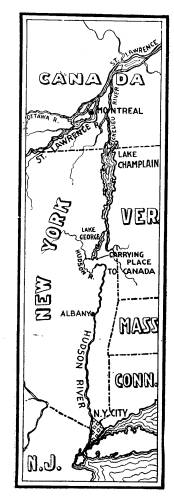

|

in order to reach their homes along the borders of Lake Huron and Lake Simcoe. This great water-way leading from the waters of New York Harbor to the St. Lawrence is about four hun- dred and fifty miles in length, with only seven or eight miles of portage or "carrying place." The Hudson river furnishes about one hundred and fifty miles of this water-way, and lakes George and Champlain and the Richelieu about three hundred miles. It was a singular coincidence that at the same time Champlain was ex- ploring and making war on the wa- ters of the lake which bears his name, Henry Hudson, an English naviga- tor, was exploring the waters of the Hudson river which bears his name, so in the same year this entire water- way was made known to Europeans. The Hudson river was not, as is generally assumed, discovered by Hudson, but by Giovanni da Verraz- zano in 1524, who was sailing under a commission from Francis I. of France. Verrazzano sailed into what is now the port of New York and some little distance up the Hudson. This was eighty-five years before Henry Hudson saw that stream. In |

|

the meantime the French fur traders had penetrated that river at least as far as the present city of Albany, but it was not until the year 1609 that the entire water-way from the St. Lawrence to the port of New York became known to Europeans. |

Water Highways and Carrying

Places. 365

For what thousands of years this great

route was known

and used by the Aborigines can never be

known, but certainly

from the remote time when human beings

came to inhabit that

part of the country. Since the coming of

white men with a view

of possessing the country, there has

been innumerable war expe-

ditions conducted along this great water

route between the French

and their Canadian allies and the

English and their allies, the

Iroquois. Important battles and

massacres and conflicts, of every

nature, have since that time taken place

on these waters and along

their shores. It is not within our

purpose to enumerate even im-

portant war expeditions, but we will be

pardoned for recalling

a few of the later and more important

engagements which took

place, in which "white men"

were engaged, as showing the im-

portance of this route as considered by

the French and English

and the people of our colonies.

On the 16th of April, 1755, a commission

was issued to Col.

William Johnson of New York, appointing

him major general of

the forces to be sent by this route to

Canada to expel the French

from Crown Point, where they had

strongly entrenched them-

selves. Sir William was to have in his

commnad 3,500 colonists

and British, and 1,000 Indians. He

commenced his forward

movement early in August, 1755, and on

the 14th of August

arrived at Fort Edward where he was

joined by 250 more In-

dians. In the meantime Baron Dieskau, in

command of the

French and their Indian allies, was

marshalling his forces to resist

the incursion of Sir William and his

army.

On the 7th of September the forces met

and a desperate

battle ensued, which, after varying

fortunes, resulted in favor of

Sir William and his forces. Sir William

and Baron Dieskau

were both wounded and the latter was

taken prisoner and sent

to New York and thence to England. He

was succeeded in com-

mand by Montcalm, who, on July 8, 1758,

with 3,600 men suc-

cessfully defended Ticonderoga against

the British General Aber-

crombie who assaulted that place with

14,000 men,

of which he

lost 2,000 killed and wounded.

This water-way was also the route taken

by Gen. Robert

Montgomery in command of the continental

troops in the invasion

366 Ohio Arch. and Hist.

Society Publications.

of Canada in 1775. He succeeded in

taking all the forts on these

waters and along the St. Lawrence until

he reached the City of

Quebec, which was the great objective

point, where, in an assault

made upon that stronghold December 31st,

1775, his forces were

repulsed with heavy loss, General

Montgomery being among the

dead.

General Burgoyne was placed in command

of the British

Canadian forces in America when he

arrived early in 1777. He

came with a large British (Hessian)

force of about 8,000 troops

to the St. Lawrence River where he

invited the Indians to

join him, many of whom did so. He

advanced along the line

of the Richelieu and Lake Champlain and

Lake George, until

he reached the headwaters of the last

named lake, with a view

of taking possession and holding the

line of the Hudson River,

but his plans were frustrated. He was

hindered, delayed and

defeated at Stillwater, New York,

September 19th, and again

at Freeman's Farm, October 7th, and was

compelled to surrender

with his whole army near Saratoga,

October 17, 1777. So it will

be seen that this great highway from the

waters of the St. Law-

rence to the waters of the Atlantic at

New York has been, within

historic times, a great military

highway.

Henry Hudson was most fortunate in

having his name

stamped upon this important river. Not

only the Hudson river

received his name, although not

discovered by him, but Hudson's

Bay and Hudson's Strait will forever bear

his name, although he

was not the original discoverer or

navigator of either.

It is certain from maps and charts of

former navigators,

particularly that of Sebastian Cabot,

that Hudson's Bay had been

entered and partially explored nearly a

hundred years before

Hudson entered those waters. It was on

this voyage to Hud-

son's Bay that he met his sad fate. The

ship's crew mutinied

and placed him and his son and seven of

the seamen in an open

boat and set them adrift on the desolate

and gloomy waters of

Hudson's Bay. No trace of them was ever

found, although

when the facts became known in England a

searching expedition

was sent out to look for them. They

undoubtedly perished in the

waves of that storm-swept and lonely

sea.

Water Highways and Carrying

Places. 367

E'TIENNE (STEPHEN) BRULE'.

As we have before seen Stephen Brule

came to Quebec in

1608 which was the second visit of

Champlain to the waters of

the St. Lawrence. He was with Champlain

at the battle on

the lake now known by that name, in 1609. He remained

on the

St. Lawrence during the winter of 1609-10, when he

again joined

Champlain in a war expedition, and

participated in the battle of

June, 1610, near the mouth of the

Richelieu River, where a

hundred Iroquois who had barricaded

themselves, were entirely

destroyed by Champlain and his Indian

allies. In June, 1610,

he went to spend a year with the Hurons

in their country on the

waters of Lake Huron at the foot of what

is now called Georgian

Bay. His route was up the Ottawa River

to the mouth of the

Mattawan, thence up that stream to the

"carrying place" leading

to Lake Nipissing, thence across that

lake to its overflow the

French river, thence down that river to

the waters of Lake Huron,

andthence along the east coast of that

great lake to the country

of the Hurons. Brule was certainly the

first "white man" or

European that ever passed over any part

of that long and diffi-

cult route or saw any of these lands or

waters. In the spring

of 1611, he returned by the same way,

when the Indians came to

barter their furs on the banks of the

St. Lawrence and to ex-

change him for "Savignon" the

young Indian whom Champlain

had taken to France the year before.

In July (1611) Champlain returned to

France and Brule

remained among the Indians of Canada for

two years and until

Champlain's return in 1613. During this

time he roamed far

and wide in the wilds of the Indian

country.

In 1615 Champlain was again on the St.

Lawrence and agreed

to go with the Hurons and Algonquins to

the Huron country with

a view from there of invading the

Onondaga country which was

in the very center of the Iroquois

tribes. Their principal village

was in the vicinity of Oneida Lake, New

York. The place of

assembling was Lake Simcoe in the Huron

country and about one

hundred miles north of the present city

of Toronto.

As we have before seen, Brule separated

from Champlain

and his army and left them at Lake

Sincoe, and with two birch

368 Ohio Arch. and Hist.

Society Publications.

canoes and twelve Indians for an escort,

descended by way of

numerous small lakes and other waters to

the mouth of the Hum-

ber River. This was to the Indians a

well known highway by

which Lake Huron and Lake Ontario were

connected, and, except

in times of war, was the best and most

desirable route from the

Huron country to the St. Lawrence. Brule

crossed the upper

end of Lake Ontario to a point at or

near the Niagara River

and from thence passed entirely through

the Iroquois country to

the upper waters of the Susquehanna, in

Pennsylvania. After

the defeat at Onondaga, of Champlain and

his allies, Brule was

compelled to retrace his way to the

Carantouan villages.

During the winter of 1615-1616, the

restless spirit of Brule

impelled him to explore the Susquehanna

to its mouth where it

empties into the Chesapeake Bay from

which he returned again

to the Carantouan country, and the next

spring the Carantouans

gave him an escort of five or six

warriors to act as guides to

pilot him back to the Huron villages. He

was taken prisoner

by the Senecas while passing through

their country and narrowly

escaped death by torture. However, he

ingratiated himself with

the Senecas, and the next spring (1617)

returned to his Huron

friends. Here he seems to have rested

and occupied himself

in the Indian fashion of hunting and

trapping until the next

spring (1618), when he returned with the

Hurons as they went

to the St. Lawrence to trade. Here he

met Champlain, from

whom he had been separated for almost

three years, and related

to him his various and remarkable

adventures. In the last named

year Champlain returned to France, but

Brule remained among

the Indians. Champlain says of him that

he had at that time been

"eight years with the Indians"

and had acquired their various

languages.

When, in 1618, Brule had arrived from

the Indian country

and met Champlain at Three Rivers on the

St. Lawrence, he was

urged by Champlain to continue his

exploration to the northward

and westward from the mouth of the

French river from which

country they had received reports of

copper mines and had in

fact seen specimens of copper which the

Indians brought from

that country. It is probable that in the

summer of 1618 or 1619

he went north along the North Channel to

the country of the

|

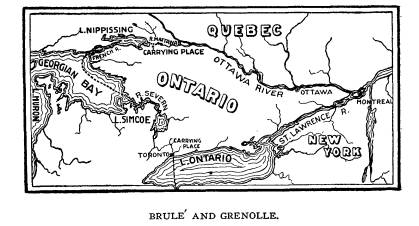

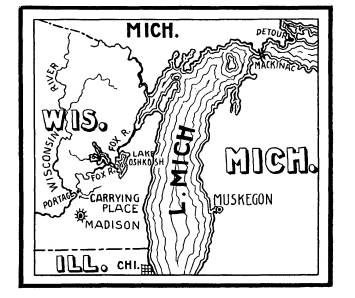

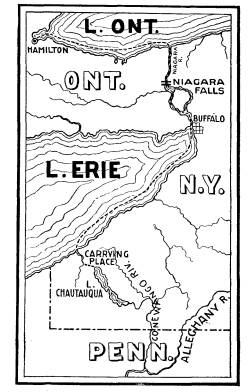

Water Highways and Carrying Places. 369 Beavers, who then had their homes in the region east of the falls of the St. Mary's. In the summer of 1821 he was again on the St. Lawrence from which he returned to the Huron country where he met his future companion and fellow voyager, Grenolle. The following diagram will sufficiently indicate the lines which Brule traveled as the first "white man." |

|

|

|

In 1621 Brule was again in the Huron country from which place with a companion, a young Frenchman named Grenolle, he started for an extended exploration to the north and west with a view of ascertaining the character not only of the lakes and rivers and Indian tribes but to locate if possible the copper mines of which they long had been informed existed in that country. Leaving the Hurons they urged their canoe past the mouth of the French river and proceeded northward past the Manitoulin islands along the North Channel to the falls of St. Mary's. The entire distance from the mouth of the French river to the falls of St. Marys was unexplored (unless by Brule in 1618 or 1619) and to Europeans unknown, except by such in- definite and vague reports as they might have received from the Indians. There is but little that is definite about this expedition to Lake Superior, but as they were on an expedition of general discovery with the intention of enlarging the geographical knowl- edge of the white man, it cannot be supposed that two such ven- Vol. XIV.- 24. |

370 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

turesome spirits as Brule and Grenolle

would have stopped short

at the falls of St. Mary's. They would

naturally and necessarily

want to know more about the waters

beyond from which this

vast overflow of clear, cold water came,

rushing over one of

the most stupendous and beautiful rapids

in the world. Stand-

ing on the banks of the rapids they

necessarily looked out upon

the waters of Lake Superior and so were

the first white men to

see and discover the greatest fresh

water body on the globe.

They were gone on this expedition for a

period of two years,

which would give them ample time to have

reached the head or

western end of Lake Superior where are

now the cities of Du-

luth and Superior. The exact point,

however, to which they

urged their canoe is not known, but as

one of their main objects

was to solve the question as to the

"North Sea," now known as

Lake Superior, it is impossible to

suppose that they stopped short

of their main purpose. That they went on

the waters of Lake

Superior to a nation that, to some

extent at least, worked the

copper mines, of which they had

previously heard, there can be

no doubt, as they brought back with them

a large ingot of copper

which could not have been had short of

the region of Lake Su-

perior. It is strong evidence of their

having reached the extreme

head of Lake Superior that the Indians

say that the journey

from the Huron country was thirty days,

while Brule reported

it as four hundred leagues, showing that

Brule's estimate was

his own and not what he had learned from

the Indians.

The historian Sagard says that Grenolle

reported "that a

nation living one hundred leagues from

the Hurons worked in

a copper mine and that he had seen among

them several girls

who had the ends of their noses cut off

having committed

offenses against chastity."

Sagard (one of the early priests to

visit the Huron waters)

who met and traveled with Brule and

Savignon on their return

trip down the Ottawa, says of Brule

"that this bold voyager, with

a Frenchman named Grenolle, made a long

journey and returned

with an ingot of red copper and with a

description of Lake Su-

perior who defined it as very large,

requiring nine days to reach

its upper extremity and discharging

itself into Lake Huron by

a fall."

|

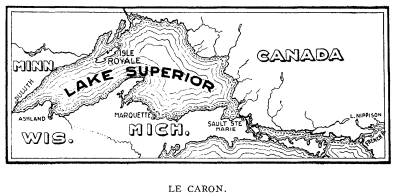

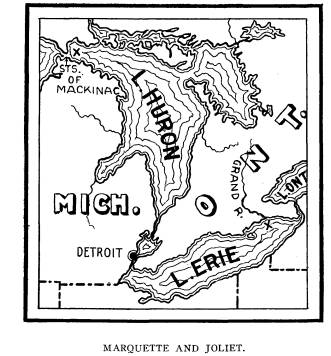

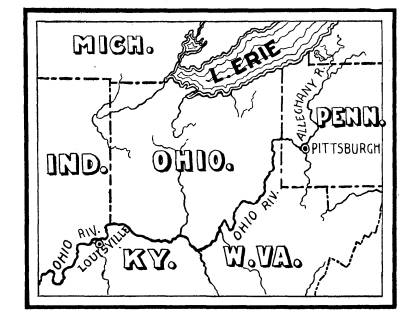

Water Highways and Carrying Places. 371 It is possible and even probable that Brule was the first white man to see the stupendous falls of Niagara. He was in that im- mediate vicinity at least on two occasions as early as 1615-16, which was before any other European had visited that region. It may be assumed that Brule, who was so intensely inclined to see all objects and places of interest, would not have allowed Niagara to escape him. The last few years of Brule's life he remained entirely with the Hurons, who in 1632 for some unknown cause barbarously murdered him after a residence among them of more than twenty years. Their savagery did not stop at his death. It is most revolting says Parkman, that "In their wild and horrible ferocity to take vengeance on their victim, they feasted upon his lifeless remains." The following diagram will sufficiently indicate the lines which Brule and Grenolle traveled as the first "white men." |

|

|

|

For more than two hundred and fifty years Friar Joseph Le- Caron received credit generally for having been the first white man to pass up the Ottawa and the first to discover the waters of lakes Nipissing and Huron, and it is only of late years that this error has been corrected. Modern investigation has shown that he was entitled to no such distinction. He in fact discovered noth- ing whatever which added to the geographical knowledge of the country. He was a devout and zealous priest in the Catholic Church, and ardently anxious to convert savages to his faith, but |

372

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society

Publications.

he was in no sense an explorer and

deserves no credit as such.

He did not leave France until May, 1615,

and in due time arrived

at Quebec with three other priests of

the Catholic Church. He

was assigned to establish a mission

among the Hurons, many of

whom were then near Montreal where they

had come to trade

with the French, and he went direct to

that place. Champlain

had arranged with the Indians there

assembled to join them in

a campaign against the Iroquois before

mentioned. LeCaron

had nothing whatever to do with that

expedition, but finding the

Hurons having finished their bartering

with the French traders

on the St. Lawrence, were about to

return to their own country

preparatory to their campaign against

the Iroquois, he determined

to accompany them. He had no connection

with the intended

incursion into the country of the

Iroquois. That had been ar-

ranged for by Champlain and the Indians,

and LeCaron simply

availed himself of the opportunity to

obtain access to the Huron

villages with a view only of propagating

his religious faith. The

Indians with whom LeCaron traveled left

the St. Lawrence on

the first of July, 1615. It

was necessary for Champlain to post-

pone his departure for a few days, but

on the 9th of July, he, with

Brule and another French lad (probably

Grenolle) left the St.

Lawrence to join in the expedition

against the Iroquois. He

reached the Huron country a few days

after LeCaron and the

Indians with whom he traveled, but Brule

had been for five years

in that country and had made yearly

trips with the Hurons to the

St. Lawrence along the route of Lake

Nipissing and the Ottawa

river, and was as familiar with the

route and the country as the

Indians themselves.

Years before LeCaron ever saw an Indian,

Brule had lived

with them and had acquired the language

of different tribes in

the regions where he had been; and he

went along now with

Champlain as his interpreter of the

languages of the various

tribes. The claim as to LeCaron was

based upon nothing more

substantial than the fact that the

Indians with whom he traveled

reached the Huron country a few days in

advance of Champlain.

Most of the early writers concerning the

history of that time

mention Brule as having gone to live

with the Indians in the

summer of 161O, but they seem to have

fallen into the habit of

Water Highways and Carrying

Places. 373

not considering him in their narrations.

But when it comes to

naming the "first European" or

"white man" in connection with

these explorations and discoveries Brule

cannot be ignored, but

must be given place in history which

rightly belongs to him.

LeCaron left the Huron country in the

spring of 1616, as

soon as the waters were free from ice.

He was only a few months

in that country during which time he was

attending to his relig-

ious duties and made no incursions or

discoveries. Brule had

left him there when he went on the

campaign against the Iroquois

and when he returned to the Huron

villages, Le Caron had been

gone from that country more than a year.

JOHN NICOLET.

John Nicolet, a young Frenchman, arrived

at Quebec in the

spring of 1618 and was immediately sent

by Champlain to the

Ottawa country to learn the language in

use among the Ottawa

tribes. He remained with them two years,

during which time

he saw not a single white man.

Subsequently he made his home

for several years with the Nipissings

from whence he was re-

called by the government to the St.

Lawrence and employed as

an interpreter and commissary. He went

again among the In-

dians where he remained from 1629 to 1632. This

was during

the time that Quebec was in the

possession of the English, from

which place he held himself aloof and

remained away during

that time in the remote country of Lake

Nipissing. He returned

to the St. Lawrence in 1633 and the next

year (1634) was se-

lected by Champlain to go upon an

exploring expedition to the

regions further west than had yet been

visited by white men.

The expedition was in the interest of

the "Association of one

hundred" who desired to enlarge

their knowledge of the Indian

tribes and country with a view of

extending the fur trade, of

which they then had a monopoly. A still

further object was to

locate, if possible, the copper mines of

which they had heard

so much from Brule and Grenolle and the

Indians around the

upper lakes. Nicolet was selected to

make a venture into this,

at that time, unknown country except as

to such information as

they had received from the natives. They

had heard of the

374 Ohio

Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

Winnebagoes who were at that time

located west of Lake Mich-

igan, and Nicolet was especially

instructed to visit them and also

any other tribes who might be found in

that region.

It was in 1634 that Nicolet started on

his mission. He pur-

sued the usual route by way of the

Ottawa, Nipissing and the

French river, and at the mouth of the

French river he turned

north and west as Brule and Grenolle had

done thirteen years

before. He held his way along the north

shore of the Huron

waters to the falls of St. Marys, as

Brule and Grenolle had done.

From the falls he turned south along the

St. Mary's river to

where it enters the waters of Lake

Huron, and from that point

commences his original explorations and

discoveries. He pro-

ceeded along the north shore of Lake

Huron, past the Straits

of Mackinaw, around the north and west

shores of Lake Michi-

gan until he entered the waters of Green

Bay. From Green Bay

he proceeded up the waters of Fox River

to near the carrying

place from that stream to the waters of

the Wisconsin river and

there ended his original or first

"white man's" discoveries.

Nicolet returned to the St. Lawrence and

was employed in

important relations mostly at Three

Rivers and Quebec until 1642,

when he lost his life by the upsetting

of a boat in which he was

hurrying on a mission of mercy to save

an Iroquois from being

tortured by the Algonquins who had

captured him.

Nicolet was a devout Catholic but not a

Jesuit. His life

and character and conduct in his

intercourse with the numerous

Indian tribes was such that they all

reposed the greatest confi-

dence in him in life and entertained the

highest respect for his

memory of which their natures were

capable.

The diagram on page 376 will in a

measure show the route

of original discovery to which Nicolet

is entitled to credit.

JOLIET.

In 1669, Talon, then Intendant of

Canada, sent Joliet with

a young French companion to explore and

locate if possible the

copper regions of Lake Superior. He

failed in his mission in

so far as the copper regions were

concerned, but they made a

most important excursion over waters

that had not before that

|

Water Highways and Carrying Places. 375 time been reached or seen by any European. On their return from the northern lakes, they coasted down the west shore of Lake Huron and visited the Pottawattamies then living on that shore. The Pottawattamies had, at that time, never seen a white man. From the Pottawattamie country they coasted on down the west shore of Lake Huron to the point where the waters of that lake flow south through the St. Clair and Detroit rivers. From there these daring explorers held their way with the current |

|

|

|

of these rivers until they reached the waters of Lake Erie. Thence they proceeded along the northern coast of Lake Erie to the mouth of the Grand River not far west of Niagara Falls. They turned up Grand River (now the home of the Senecas) and proceeded to a point near the present city of Hamilton, On- tario, where they met LaSalle and the Sulpitian priests. They were the first Europeans to navigate or see the waters along the route which they took from the northern end of Lake Huron to a point near the city of Hamilton. The information which they imparted to LaSalle and the priests as to the waters over which |

|

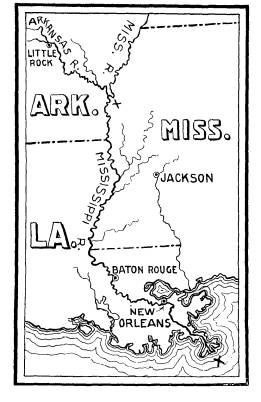

376 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications. they had just passed, and the condition of the Pottawattamie nation determined the priests to go at once to that country as a field for the exercise of their religious proclivities. It was here that they parted with LaSalle who held firmly to his purpose of exploring the Ohio River country. Joliet and his companions are entitled to be considered the first white men or Europeans to pass over any portion of these waters over which now passes by far the greatest commerce of any inland waters in the world. The following diagram will indicate the lines of original travel taken by Joliet and his companion. |

|

|

|

In 1672, Frontenac, then Governor of Canada, and Talon, the Intendant, determined to send an expedition to the regions further west than had yet been visited by white men and to search out and locate the great Mississippi river and to learn as much |

Water Highways and Carrying

Places. 377

as possible of any tribes that they

might meet with. Their pur-

pose was largely mercenary, their object

being to secure a knowl-

edge of new tribes and new regions so as

to enlarge the fur trade

on the St. Lawrence. Jolliet was

selected by them for this ser-

vice, for which he was in the highest

degree fitted. He had been

born at Quebec and brought up in the

wilderness of the lake coun-

try and was intelligent, hardy and

daring, thoroughly versed in

the habits of the Indian tribes. He had

already made long ex-

cursions to the lake country and had

made valuable discoveries

of new routes of travel by water and of

new tribes of Indians.

He was to have associated with him

Father Marquette who had

seen service as a missionary at the

falls of the St. Mary's and at

LePoint (Apostles Islands) on the south

side of Lake Superior.

While stationed in these places as a

priest of the Catholic Church,

Marquette had learned much concerning

Lake Michigan and the

Mississippi and Illinois rivers. He had

come in contact with

numerous members of the tribes occupying

the vast region to the

south and west of Lake Superior and

greatly desired to explore it.

Joliet reached Mackinaw on this

expedition in the fall of

1672 with instructions to Marquette to

join him in the proposed

venture which gave great pleasure to the

ardent priest, as it

was in harmony with his own desires.

They spent the winter

in preparing for the journey and in

informing themselves as fully

as possible concerning the regions and

tribes they were to visit.

On the 17th of May, 1673, they embarked

in two canoes with

five men. These two frail canoes were

destined to carry them

from "the snows of Canada to the

more congenial clime of Ar-

kansas" and to tide them over

thousands of miles of water which

had never before been disturbed by a

white man's canoe. From

Mackinaw around the north and west shore

of Lake Michigan

they passed over the same route which

had been traveled by Nico-

let thirty-nine years before until they

reached the waters of Green

Bay. From there they ascended the Fox

river to the carrying

place from the waters of that river to

waters of the Wisconsin

river. This carrying place was near the

point at which Nicolet

had turned back. It was but a mile and a

half from the waters

of one river to the waters of the other,

but the way was so intri-

378 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

cate through the vast field of wild rice

which grows in such abun-

dance in that region as to require the

services of Indian guides

to pilot the way through them. When they

reached the waters

of the Wisconsin they dispensed with

their guides and proceeded

for six days to descend the Wisconsin to

its mouth where it empties

into the mighty Mississippi. When their

canoes shot out on the

waters of that the greatest of rivers on

the continent the adventur-

ers were greatly rejoiced, and well they

might have been as they

had at last discovered and were upon the

waters of the long

sought for Mississippi. The voyagers

turned south with the

current of the river and proceeded for

more than a thousand

miles. They passed the mouth of great

rivers emptying into the

Mississippi and found many tribes of

natives inhabiting the shores,

most of whom proved friendly. They did

not change their course

until they had reached the mouth of the

Arkansas river where

DeSoto had crossed the Mississippi 132

years before. At this

point they were able to determine that

the Mississippi flowed

into the Gulf of Mexico which was an

unsettled question up to

that time. From this point on the 17th

of July, 1673, they com-

menced their return up the Mississippi

and proceeded with great

difficulty and considerable delay on

account of the illness of Mar-

quette until they reached the mouth of

the Illinois, into which

they turned their canoes and urged them

up that placid stream

to the important Indian village of

Kaskaskia. They found the

people of this very important village

friendly, and after some stay

there, the Indains kindly piloted them

up to the mouth of the Des

Plaines, up which they proceeded to the

carrying place over into

the Chicago river. They then coasted up

the west shore of Lake

Michigan to Green Bay which they had

left four months before.

Jolliet proceeded at once to the St.

Lawrence while Marquette

remained at Green Bay.

Marquette and Joliet are entitled to

credit for having been

the first white men to pass from the

carrying place between the

Fox river and the Wisconsin to the mouth

of the Arkansas and

on their return from the mouth of the

Illinois to the mouth of

what is now the Chicago river, thence

along the western coast

to Lake Michigan to Green Bay.

|

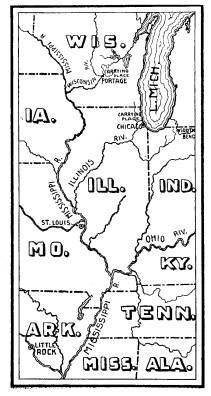

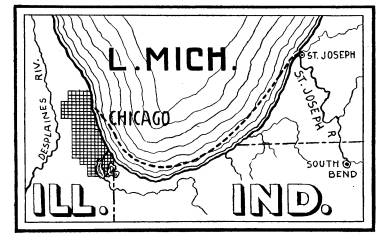

Water Highways and Carrying Places. 379 The following diagram will show, in a manner, the routes over which Marquette and Jolliet are entitled to be considered the original navigators and explorers. |

|

|

FATHER JAMES MARQUETTE. When Marquette and Joliet reached Green Bay in the fall of 1673 the former was in in- firm health and rested at Green Bay for nearly a year, but his health being in part restored he determined to re- turn to the Illinois river as he had promised the Indians he would do. The course taken by Marquette and associates, two of whom were French, was along the west side of Lake Michigan to the mouth of the Chicago river. He pur- sued the route from that point to some distance inland where he suffered a relapse and was compelled to spend the winter in a rude hut constructed by his French companions. They suffered greatly during the winter, but in the spring of |

|

1674, Marquette renewed his efforts to reach his Indian friends on the Illinois with a view of establishing a mission among them. He succeeded in this and was most joyfully received by the natives. He administered religious instruction to them for a short time, but his health was such that he was required to make an effort to return to his mission at S. Ignace. A number of Indians accompanied him up the Illinois river to the mouth of the Kan- kakee; thence up that lonely and crooked stream for several hun- dreds of miles until they reached a point near where is now the |

380

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

city of South Bend, Indiana, where there

was a short carrying

place of about four miles from the

Kankakee over to the head-

waters of the St. Josephs of Lake

Michigan, and there it seems

the Indians left him. From there he,

with his two French com-

panions, floated down that river to its

mouth where it empties

into the east side of Lake Michigan.

From this point his faith-

ful escorts proceeded for several days

north along the east shore

of Lake Michigan until his strength

entirely failing him, and

himself realizing that death was upon

him, requested his com-

panions to take him on shore that he

might die in peace. His

every request was complied with. A rude

shelter was prepared

for him where, after a few days and

nights of devotion, he passed

peacefully away, and was buried at the

place of his death on

the desolate and lonely east shore of

Lake Michigan.

In reviewing the lives and characters of

the priests of the

Catholic Church who energized among the

Indians of that time,

or of any time, Marquette was clearly

the most celebrated and

most beloved by the Indians. He died in

1674 at the age of 38

years, but his name has a permanent

place in the history of his

times.

The two French companions of Marquette

on his last voy-

age proceeded to Mackinaw, which place

they reached in safety

and are entitled to be considered the

first Europeans to coast along

the eastern shore of Lake Michigan from

the point where Mar-

quette was buried to the Straits of

Mackinaw.

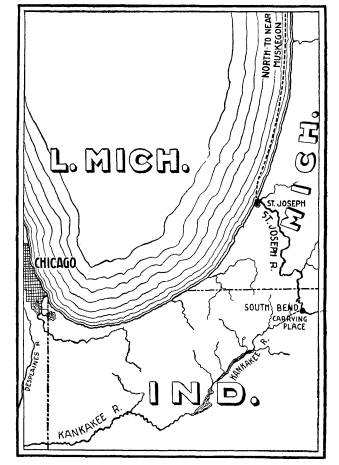

The diagram on page 382 will

sufficiently show the route

taken by Marquette on his return from

the Illinois river in 1674.

This route had never before been

traversed by white men.

LA SALLE.

La Salle came to Montreal from France in

1666. His equip-

ment for whatever experiences he might

have in his career in

the New World was that he was well

fitted mentally and physi-

cally to meet whatever fortunes or

misfortunes might befall

him. His ambition and his courage were

unbounded and not

unmixed with greed of gain. He had

visions not only of wealth

but of dominion and empire. Before his

time extensive explo-

|

Water Highways and Carrying Places. 381 rations had been made, but he soon learned from contact with the Indians, especially the Senecas, a party of whom had wintered at his quarters in 1668-69, of still vaster regions that were as yet unexplored and unseen by white men. He heard especially of |

|

|

|

the waters of the Ohio, some of which headed in the Seneca country and to which his Seneca friends offered to guide him. He knew that the waters of the Ohio would reach the great Miss- issippi river and finally flow into the sea, but where and into what |

382 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society

Publications.

sea was the great mystery. It is

probable that his hope in this

first exploration to the Ohio country

was that he might reach

the Mississippi; and in all probability

he would have done so

had his crew remained loyal to him.

This expedition was organized in 1669 at

LaChine, near

Montreal. At the same time the Sulpitian

priests at LaChine

were organizing an expedition for the

purpose of searching out

and converting to their faith such

Indian tribes as they might

find in the unknown country of the Ohio.

The two expeditions

were united in the beginning. LaSalle

had procured four canoes

and seven men, while the Sulpitians had

their own canoes and

their own men. The members of this

expedition were all French-

men and would have to procure guides

from the Indians when

they reached the upper end of Lake

Ontario. On the 6th of

July, 1669, they proceeded up the St.

Lawrence river to Lake

Ontario and along the south shore of

that lake to a point not

far east from the mouth of Niagara river

where the expedition

rested while LaSalle visited the village

of the Senecas with a

view of obtaining guides to the Ohio. He

failed to secure guides,

as he had hoped, and as the season was

getting late the expedition

again moved forward along the south

shore of Lake Ontario,

past the mouth of the Niagara river and

proceeded until they

reached an Indian town near where the

city of Hamilton, Canada,

now stands. While at this village he learned of two young

Frenchmen being near by, and there for

the first time Joliet and

LaSalle met. Joliet, as before stated,

was returning from the

expedition which he had undertaken at

the instance of Talon in

search of the copper regions of Lake

Superior. This meeting

caused a separation of La Salle's party

from the missionary party.

Joliet told them of the Pottawattamies

who greatly needed relig-

ious instructions, and the missionaries

determined to go at once

to their spiritual rescue while LaSalle

adhered to his original pur-

pose of visiting the valley of the Ohio.

The home of the Potta-

wattamies was at that time in the

country west of Lake Huron.

It is conclusive that Joliet in

returning from his search for

copper mines in 1669 coasted the west

shore of Lake Huron for

the reason that he visited the

Pottawattamies and reported their

spiritual condition to the priests who

were with LaSalle when

|

Water Highways and Carrying Places. 383 they met near the head of Lake Ontario. The Pottawattamies occupied the country west of Lake Huron and in order to visit them Joliet necessarily had his course along the west shore of that lake. The missionaries failed in their purpose to reach the Pot- tawattamies, but passed up the eastern side of Lake Huron, and |

|

|

|

the north channel until they reached the falls of St. Marys, from which place they returned by the way of Lake Nipissing and the Ottawa to the St. Lawrence, having discovered nothing and ac- complished nothing. LaSalle succeeded in carrying out, in large part, his original plan. Just what course he took after separating from the missionaries is not known with entire certainty, but it |

|

384 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications. may be assumed that he passed near the head of Niagara river and along the south and east side of Lake Erie to a point oppo- site Chautauqua Lake. From Lake Erie to Chautauqua Lake there was a well known and much used carrying place of about eight miles. From there the route was over the waters of Chau- tauqua Lake to its outlet near Jamestown, New York, from where the overflow waters, united with the other streams, flow |

|

|

|

into the Alleghany river near Warren, Pennsylvania, and thence descend to the Ohio. It was by this route that the French sub- sequently sent a force two hundred strong to take possession of the Ohio. Not much is recorded of this excursion of LaSalle except that it extended down the Ohio to the falls at Louisville, Ken- tucky. Here most of his men deserted him and he was compelled to return almost if not entirely unaccompanied. His way of re- turn has not been definitely determined, but it was necessarily by way of the Big Miami and the Maumee (then called Miami |

Water Highways and Carrying

Places. 385

of the Lake) or by way of the Scioto and

Sandusky rivers. No

other routes were at that time opened to

him. Whichever of these

routes he may have taken he was the

first white man to have

passed over it. The probabilities are

that he went by the Big

Miami and the Maumee to Lake Erie, but

it is not certain, and

not much can be claimed in respect to

it.

Between the ending of this expedition

and the undertaking

of his next important voyage of discovery

there elapsed a period

of about nine years. In the meantime he

was exceedingly en-

gaged with important affairs along the

St. Lawrence and in

France, to which country he had in the

meantime made several

voyages.

In 1679 he planned a voyage over Lake

Erie, through the

Detroit and St. Clair rivers and over

Lakes Huron and Michigan

with a view of reaching and exploring

the Mississippi river, as

well as engaging in the fur trade. In furtherance of this plan

he built on the Niagara river above the

falls a vessel of forty-

five or fifty tons with which to

navigate the great lakes. They

named the vessel the

"Griffin." There were three friars of the

Sulpitian order in the party that sailed

on the "Griffin," among

whom was Father Hennepin, a man of

considerable learning and

a ready and somewhat graceful writer,

and had considerable

talent for describing places where he

had never been and things

that he had never seen. He immortalized

himself by stories

which he related and books which he

published when he re-

turned to France which have secured for

him, for all time to

come, the appellation of "the most

impudent liar." Nothing

could exceed his audacity in this

respect.

The expedition started in the summer of

1679 from the

Niagara river and passed safely over

Lake Erie, Lake Huron

and through the Straits of Machinaw

until they reached Green

Bay on the waters of Lake Michigan. Here

the vessel was

loaded with a rich cargo of furs, and

LaSalle sent it back to

Niagara in charge of his pilot and five

men. The vessel was

never heard of afterwards. It was lost

somewhere between Green

Bay and its destination the Niagara

river. From this point (Green

Bay) LaSalle determined to push forward

to the Illinois country,

and in pursuance of this purpose passed

down the west shore of

Vol. XIV.- 25.

|

386 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications. Lake Michigan and around the south end to the St. Joseph river. From Green Bay to the mouth of the Chicago river the route had been traversed by Marquette and Joliet several years before; but from the mouth of the Chicago river to the mouth of the St. Joseph, LaSalle and his party were the first white men to traverse it. From the mouth of the St. Joseph to the mouth of the Illinois, and on to the mouth of the Arkansas river the route had all been explored before this expedition of LaSalle. When LaSalle and his party reached Illinois country he determined to build a fort |

|

|

|

and establish a camp as a basis for further explorations. But from this place LaSalle was compelled to return to Lakes Erie and Ontario, leaving the colony on the Illinois in charge of his faithful Tonty with instructions as to its conduct and manage- ment in his absence; and at the same time he instructed Hennepin to proceed down the Illinois to its junction with the Mississippi and to make such other and further explorations as opportunity might afford. In the meantime, pursuant to the instructions of LaSalle, Hennepin with two French companions (Michael Accau and a man known as Picard du Gay), proceeded to the mouth of the Illinois, thence up the Mississippi to the mouth of the Wis- consin. From their starting point on the Illinois to the mouth of |

Water Highways and Carrying

Places. 387

the Wisconsin they passed over waters

that had before that time

been explored by Marquette and Joliet.

From the mouth of

the Wisconsin, however, to the falls of

Minnehaha, near the

present city of Minneapolis, he and his

companions were the first

white men to explore that part of the

Mississippi river. They

were taken prisoners by the Sioux

Indians somewhere in that

country and were for some time detained

by them, but were

finally released and Hennepin returned

to the St. Lawrence by

way of the Wisconsin river, Mackinaw,

Nipissing, and the Ot-

tawa. From the St. Lawrence he returned

to France where

he wrote and published volumes of

stupendous lies which made

him famous at the time and infamous for

all time. He has se-

cured immortal fame in history both as a

liar and a plaguerist.

As soon as LaSalle had established his

camp and fortified

himself in a strong position, which

fortification he gave the name

of Crevacoeur, he returned to Fort Miami

at the mouth of the

St. Joseph at the southern end of Lake

Michigan, and from

there he made a journey on foot with his

five French com-

panions across the southern portion of

the State of Michigan to

Lake Erie and on to Fort Frontenac at

the foot of Lake Ontario;

but it is not within our purpose to

follow him in the strenuous

life which befell him until he

reappeared at the mouth of the St.

Joseph late in the year 1682, where he

made final preparations

for an expedition intended to reach the

mouth of the Mississippi.

On December 21st, he dispatched Tonty

and Membre from Fort

Miami at the mouth of the St. Joseph

with a part of his force

in six canoes. They crossed from the

mouth of the St. Joseph

to the mouth of the Chicago where

LaSalle joined them a few

days later. From the Chicago river over

to the Des Plaines

there was a carrying place of a few

miles, but at this time those

streams were frozen and LaSalle and his

companions were com-

pelled to construct sheds and put their

canoes and baggage on

them in order to cross from the Chicago

to the Des Plaines which

was and is the north branch of the

Illinois. They followed the

course of the Des Plaines to its

junction with the Kankakee and

thence down the Illinois to the site of

the Illinois village which

they found deserted. From there they

found the river free from

ice and proceeded with their canoes down

the Illinois river until

388

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

on the 6th of February they reached its

mouth where it empties

into the Mississippi. They tarried here

for a few days and then

commenced the descent of the great

river. They stopped at the

various Indian villages with a view of

learning as much as pos-

sible concerning them and of cultivating

friendly relations with

them. They in time reached the mouth of

the Arkansas where

they found a considerable Indian

village. This was at the point

where DeSoto and his followers first saw

and crossed the Miss-

issippi 141 years before and which had

been reached by Marquette

and Joliet nine years before. The

Mississippi had not been ex-

plored from that point to its mouth. On

the 31st of March they

passed the mouth of the Red River where

in 1542 DeSoto died

and was buried with all his ambition and

greed of gold and treas-

ures. The rich cities he hoped to find

and plunder as he and other

Spaniards had done in Mexico and Peru

were never found and

his visions of plunder and wealth

vanished into nothingness.

On the 6th of April, LaSalle and his

companions reached the

point where the river divides itself

into three channels, through

which its mighty waters rush into the

Gulf of Mexico. These

were all explored until they reached the

sea, "then the broad

bosom of the great gulf opened on his

sight, tossing its restless

billows, limitless, voiceless, lonely as

when born of chaos, with-

out a sail, without a sign of

life." (Parkman.)

In the discovery of the mouth of the

Mississippi, LaSalle had

reached the consummation of an ambition

which he had long and

ardently entertained. It would seem that

he might well have been

satisfied with what he had accomplished

in the eighteen years since

he left France, and it would have been

well for him had he been

content to rest upon the laurels which

he had gained by his stren-

uous efforts in exploring and making

known the important water

highways of the interior of the

continent. He and his associates

had aided very materially in making

known to the world the

highways and carrying places by which

the Aborigines traveled

for thousands of years. The entire

distance from the mouth of

the St. Lawrence to the mouth of the

Mississippi was more than

4,000 miles which had been traversed by

means of birch canoes,

urged on by energetic adventurous white

men. He was not sat-

isfied, however, and immediately

returned to France filled with

|

Water Highways and Carrying Places. 389 the idea of returning by sea to the mouth of the Mississippi and establishing there a military colony in the furtherance of French interests. Aided by government, he organized an expedition and sailed for the mouth of the Mississippi but miscalculating the latitude and longitude sailed past the mouth of that river and landed some distance west of that point. It is not our prov- ince to follow him further. He wandered far and wide over land, hoping to discover the great river, but he failed and on or near the Brazos river in the State of Texas, he was foully mur- dered by one of his own men. The original explorations to which LaSalle is entitled as the first "white man" to have traversed are, first, from a point near the Niagara river to the waters of the Alleghany and thence |

|

|

390 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society

Publications.

down that stream to the Ohio and on to

the falls where the city

of Louisville now stands; second, the

route by water from the

mouth of the Chicago river around the

south end of Lake Mich-

igan to the mouth of the St. Joseph; third,

from the mouth of the

Arkansas to the mouth of the

Mississippi. But these discoveries

in no wise represent the explorations

and discoveries which his

mighty energies prompted.

Champlain in his time and LaSalle in his

time were the main

springs of most of the discoveries of

the waters and countries

in the great basin which lies between

the western slope of the

Alleghanies and the eastern slope of the

Rocky Mountains and

the Great Lakes on the north and the

Gulf of Mexico on the south.

It is not at the present day generally

appreciated that these two

energetic, able and ambitious Frenchmen

came near establishing

a French empire in the New World

embracing this entire ter-

ritory.

BETWEEN LAKE ERIE AND THE OHIO RIVER.

There were three starting points on Lake

Erie by which the

Aborigines in their time, and the white

men in more modern

times passed from the waters of Lake

Erie to the waters of the

Ohio River. These were all very

important and much used as far

back as we have either history or

tradition. There were prac-

tically direct lines of canoe travel

with but few carrying places

on any of them so that the Aborigines

could pass easily from

one of these waters to the other.

The first we have to mention commenced

at the mouth of the

Cuyahoga river where the city of

Cleveland now stands, thence

up that river to a point near the city

of Akron in Summit County,

Ohio, where there was a carrying place

of about eight miles from

the waters of the Cuyahoga to the waters

of the Tuscarawas and

south with that stream to the Muskingum,

and thence along that

majestic river to its junction with the

Ohio. It is not known

who the first European or white man was

to pass over this route,

but no doubt it was first traveled by

French fur traders or voy-

agers. The ubiquious fur trader was everywhere present, in the

immediate wake of the original

explorers, but they left no records

of their travels or excursions. The main

lakes and rivers were

visited by them soon after their

existence was made known.

Water Highways and Carrying

Places. 391

As early as 1668, Joliet traversed, as

has before been seen,

Lake Erie and the Detroit and St. Clair

rivers; and the next

year a few Sulpitian priests traveled

over the same route, only

going in the other direction, and from

that time all the waters

were made known to the French traders.

On LaSalle's return

from his exploration of the Ohio in

1670, all that country was

made known and soon invaded by the

rapacious and unscrupulous

fur traders, so that we may safely

assume that all the waters of

Lake Erie and the waters leading from

Lake Erie to the Ohio

were traversed by them, and that they

must be considered as

the first white men to invade these

waters; so that it is almost

certain that the Cuyahoga and the

Muskingum and the Scioto

routes and the Maumee were all known and

often used by the

French traders prior to the time of

which we have any authentic

record.

THE SCIOTO AND SANDUSKY RIVERS.

The next important highway between Lake

Erie and the

Ohio river commenced at the mouth of the

Sandusky river and

proceeded south against the current of

that historic stream to a

very noted carrying place about six

miles east of the present city

of Bucyrus in Crawford County. This

carrying place was but

four miles long and was the only

carrying place between Lake

Erie and the Ohio river. When this route

was first traveled by

white men is not known, but like others

it was undoubtedly by

the French traders at a period long

prior to any written record

concerning this route. The first written

description that we have

was by Col. James Smith, who, in the

summer of 1755, was taken

prisoner by the Indians. He passed from

the mouth of the San-

dusky to the carrying place in Crawford

County. From there

he went with his captors to the south

west as far as the Olen-

tangy, now called the Darby. He and his

Indian companions