Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

SONG WRITERS OF

OHIO.

ALEXANDER COFFMAN ROSS.

AUTHOR OF "TIPPECANOE AND TYLER,

TOO."

"I am a Buckeye, from the Buckeye

State." This was the

proud declaration of the author of Tippecanoe,

and Tyler, too,

as he faced a large and enthusiastic

audience in New York City,

just before he gave to fame that

political campaign song-the

most effective ever sung in the history

of the Republic.

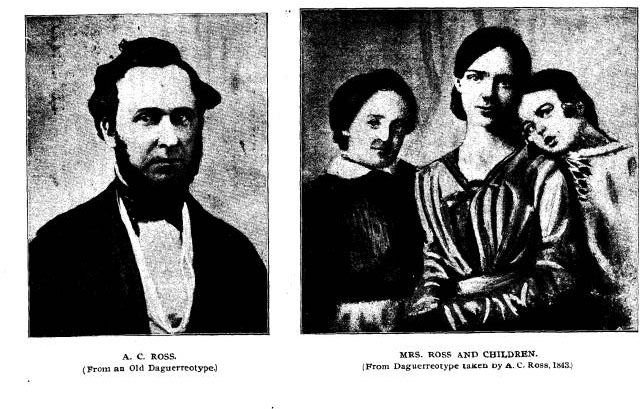

Alexander Coffman Ross first opened his

eyes to the light

in Zanesville, O., May 31, 1812. His

father, Elijah Ross,l born

in Brownsville, Pa., November, 1786,

located in Zanestown,

(Zanesville) in 1804, and died

there February 29, 1864. He was

a soldier of the War of 1812, and, being

a gunsmith, was ordered

to remain in his home town to repair

guns, swords and accoutre-

ments. His wife, whose maiden name was

Mary Coffman, was

born at Fredericktown, Pa., September

10, 1788, and died in

Zanesville December 29, 1862. Their family

numbered twelve

1In 1804, Elijah Ross came to Zanestown

(Zanesville) and prospected

through the Muskingum and Miami valleys.

He was a gunsmith by trade,

the first of this section, and soon

after his arrival in the new country

settled in the village and erected a

cabin, which served as dwelling and

shop, on what is now the northeast

corner of Locust alley and Second

street. At the beginning of the War of

1812, he entered the service as

third corporal, and was detailed to

remain at home and repair arms for

the soldiers. In 1816 he moved to West

Zanesville. In 1823 he returned

to the east side of the river, where he

continued to work at his trade.

He bored his own gun barrels, made the

first blow-pipes there used for

blowing glass (1815), and sometimes

aided the glass-blowers in their

work. He was especially fond of fox

hunting, and seemed never hap-

pier than when following his hounds over

the Muskingum hills. A genial,

unassuming man and a total abstainer

from intoxicants, he lived to the

ripe age of seventy-nine years, and died

respected for his industry and

honesty. (62)

Song Writers of Ohio. 63

children, two of whom, Mrs. Daniel Hurd,

of Denver, Col., and

Mrs. George W. Keene, of New York City,

still survive.

The parents were of the sturdy pioneers

of the new state.

They began life on the frontier in a

typical log cabin of the

period. Here the subject of this sketch

passed his boyhood in the

midst of healthful home influences and

the not unfortunate envi-

ronment of this growing and ambitious

western town, located on

the banks of the Muskingum, and directly

in the line of the great

overland thoroughfare along which the

tide of civilization was

moving to regions more remote. At the

close of the second

decade of the last century, the

"town of Zane,1 ranked second

among the incorporated places of Ohio

and stood without a rival

north of the "River Beautiful"

in thrift, aspiration and progres-

sive spirit. The old road, known in

history as "Zane's Trace,"

leading backward toward the base of

American culture and expan-

sive energy in the East, and downward

southwesterly to the realm

of forests primeval, was an avenue for

the exchange of ideas as

well as merchandise. The youth who in

"that elder day" dwelt

at the junction of the waterway and the

highway, though sur-

rounded by the wilderness, felt that he

was still on the line of

communication with the cities of the

far-away Atlantic coast.

Especially was this true of young Ross,

who seems to have

been from early years studious,

industrious and prompt to make

the best of his opportunities.

His daughter, Ellen, writing

interestingly of his social qual-

ities, says:

His grandfather was a canny Scotchman,

and I think it must have

been from this ancestor that Alexander

inherited his social traits and love

of dancing, for one of the sisters,

Margaret, used to say that the only

recollection of her grandfather was

seeing the old gentleman, on one of

his visits to his son in Ohio, come

dancing into the room in his black

velvet knee breeches and silver shoe

buckles, as gay and active as any

young dandy of his day.

From his father he doubtless inherited

and acquired a fond-

ness and aptness for mechanical

pursuits. In the little shop at

home he witnessed the repair and

manufacture of guns, and early

Including Putnam, now a part of

Zanesville.

64 Ohio Arch. and

Hist. Society Publications.

learned to handle tools. Though he did

not have the opportunity

to attend free public schools, his

education was not wholly neg-

lected. Under private teachers and at

home he gained a knowl-

edge of the common branches, which he

greatly extended by

reading with avidity the best literature

that he could get. He

found greatest pleasure in the perusal

of scientific works, and

became an expert in demonstrating by

experiment the principles

set forth in what he read. "He was

fortunate in having, toward

the latter part of his school course,

two very excellent teachers,

Allan Cadwallader and his brother,

members of a good old

Quaker family."

At the age of seventeen years, he was

apprenticed to a watch-

maker and jeweler of his native city. In

1831-32, he completed

preparation for his chosen trade in New

York City.

To such a youth, two years in the

metropolis was in itself no

mean education. Here he enjoyed rare

opportunities for reading

and investigation. Nor was his leisure

devoted to study alone.

Music and art invited to occasional

entertainment and recreation.

Returning home at the close of his

apprenticeship, he applied

himself industriously to his trade and

was soon recognized as a

master in his chosen vocation. His chief

interest was in the latest

scientific discoveries, which he

interpreted and applied with the

ease of a trained specialist.

In 1838 he married Caroline Granger, who

was in hearty

sympathy with his various enterprises and

"recreations." Their

home attracted the young people of

Zanesville who were fond

of music and art. At the age of

eighty-five years she manifests

a lively interest in current events and

finds a pleasant residence

with her two daughters at the old

homestead.

From

its founding he was an enthusiastic patron of the

Athenaeum, the local library, one of the

first in the state to have

a home of its own. This building he

rendered famous by using

it as the object in testing a wonderful

invention announced from

across the sea.

In the year 1839, Daguerre's process of

developing and fix-

ing upon a plate the image of external

objects, or, in other words,

of making the daguerreotype, was first

published in this country.

Ross read the description and proceeded

at once to construct a

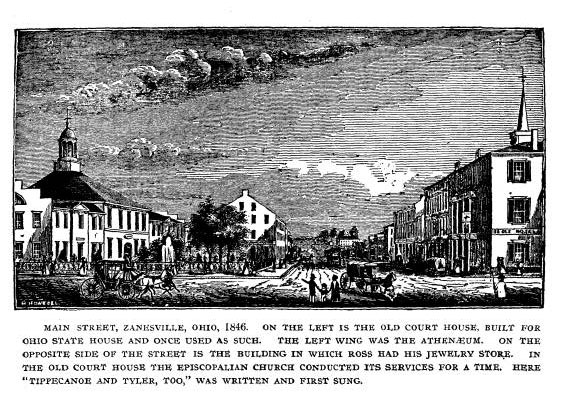

66 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

camera, using telescope lenses, and

transferred to a chemically

prepared plate a counterfeit presentment of the Zanesville

Athenaeum, the first picture of the kind

made in this country out-

side of New York City and perhaps the

first in America :1

Following is Ross's account of the

successful experiment. It

illustrates his simple and direct

exposition of a scientific process.

No apology is made for reproducing it in

full:

"On the 29th day of August, 1839,

Daguerre gave to the French

government the process which was

proclaimed by Porfessor Arago. It was

not until the following November that I

saw a notice of it, and then a

newspaper account of the process fully

described. I concluded to make

an attempt to produce a picture,

although I had no camera or silver plate.

I procured two nice cigar boxes, cut one

down so that it would slide into

the other; Master Hill loaned me the

object lens from his spy glass,

the lens having a focal length of eighteen

inches.

"The lens was secured in a paper

tube some six inches in length,

and one end of this tube was fitted into

the end of the largest cigar box,

and a ground plate (which I also made)

was fitted so as to slide in and

out of this box;- this was my camera.

The silvered plate was my next

consideration, and here I had to rely on

my knowledge as a silversmith;

I took a piece of planished copper about

three by four inches, and hav-

ing dissolved some nitrate of silver in

distilled water, I applied the fluid

with a broad hair pencil to the surface

of the plate until it was darkened,

and then immediately rubbed it over with

bitartrate of potash, and re-

peated the process until I secured a

good deposit of the silver. Con-

trary to instructions I had a 'buff'-

but more of this hereafter--and

finished up the plate until I had what

silversmiths call a 'black polish.'

The next thing was to coat the plate

with iodine; for this I placed some

iodine in the bottom of a saucer, took

it into a dark room, and by the

light of a tallow dip in one hand,

holding the plate over the saucer with

the other, I watched the process for

about twenty minutes, when I found

it coated to suit me; I afterwards

learned that this first coating was

admirably done.

"Having progressed thus far, I set

my camera out of the front window

in the building now occupied by the

Union Bank, then by Hill & Ross,

and directed it to the Atheneum. The

focus of the lens being so long,

Dr. Draper was experimenting

concurrently with Ross, and made

daguerreotypes about the same time. As

exact dates have not been

preserved, it is impossible to say who

may claim precedence in the appli-

cation of the art. Dr. Draper took a

picture of his sister, the first por-

trait made by the process in this or any other country. To

produce this

it was necessary for her to sit in a

bright light with closed eyes for half

an hour.

68 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

I could only take in about half the

building. I focused the camera,

took out the ground glass and inserted

the prepared plate, covering the

end of the camera with my hat lest the

light might get in at the sides.

I let in the light when all was ready,

and left it exposed for over twenty

minutes; it was a bright sun light. At

the end of the twenty minutes I

carried camera and all into my darkened

room, took out my plate and

expected to be able to see some outline

of the building. I was disap-

pointed, but soon I remembered that

there was another process to be

gone through, and that I had neglected

to make any preparation for it -

the plate must be exposed to the vapor

of mercury. I soon got a spirit

lamp, put a few drops of mercury in a

tea cup, applied the lamp under the

bottom of the cup and held my plate over

it. Soon the fumes rose, and

by the light of my tallow-dip, I watched

the result in breathless anxiety;

the picture began to appear and I

witnessed my success with joy unspeak-

able. I called my wife and Master Hill

and there in that little darkened

room I showed them the first

daguerreotype ever made in Ohio, or west

of New York City, to my knowledge.

"But my picture was not yet

finished; the iodine had to be removed

before I dare expose it to the light;

the chemical agent to be used to

remove the iodine was hyposulphate of

soda, and that I could not obtain.

I thought I would try salt water--I made

a strong solution in a tin

dish, put the plate into it, warmed it

over a spirit lamp, and in a short

time found my picture clear. You may

believe that I was not long in

covering it with glass and showing it to

my friends. It was noticed in

the papers that day as the first

daguerreotype ever made in Ohio.

"In February, 1840, I took a view

of the Putnam Seminary, which

I kept for many years. During the summer

of 1840 I did nothing at

picture taking; the political storm was

upon us, and every ordinary em-

ployment seemed as nothing.

"In the winter of 1840-41, I got up

a set of good instruments and

turned my attention to taking

likenesses, which was then being experi-

mented upon by Professor Draper, Morse,

Walcott and Dr. Chilton. I

met with many difficulties in not having

an achromatic lens, which at that

time was hard to get. I ordered two

planoconvex lenses (four inches

in diameter with combined focal length

of eight inches) from Paris, for

which I paid $60 to a friend in

Philadelphia. In the non-achromatic lens

there was a certain focus to get which

was not only my difficulty, but a

difficulty with all others as well.

Light has two kinds of rays-the

chemical and luminous-and these rays

have different foci, the focus

of the chemical rays being within that

of the luminous. You can, by

sight, adjust the camera to the focus of

the luminous rays, but, to get

a well defined picture you must get your

plate into the focus of the chem-

ical or actinic rays. This I did not

know, and I worked many a day

experimenting.

"I had no trouble in getting a

picture, but it was always taken in the

luminous focus and was indistinct. My

wife would sit for me for ten

Song Writers of Ohio. 69

and even fifteen minutes in the sun,

still the picture was blurred. I could

get no information on the subject; I was

almost in despair. One day I

had been using some tea cups in my room,

and had placed them on the

edge of the window sill, just in front

of where my wife sat. I had made

some change and was trying to focus the

camera on her, as usual. I could

also see the cups, but not nearly so

sharp in outline. I took the picture,

developed it, and, to my great delight,

found that the cup nearest the in-

strument was perfect, even showing the

small flower on it. I felt as if

I had made a great discovery, and to me

it was one. After reflecting

over the matter, I concluded to mark the

tube of the camera as it was

then adjusted. I then looked through the

camera at the cup, and moved

the tube until the cup was in the

luminous focus, and then again marked

the tube; the distance between the two

marks thus made was about the

one-eighth of an inch.

"I then prepared a good plate,

placed my wife again, got the luminous

focus, then pushed the tube in

one-eighth of an inch, took a picture and

found it an excellent one. My delight

was unbounded. I felt that I had

overcome a great difficulty, and solved

a mystery. I was not long in let-

ting it be known, and many a poor devil

did I help out of difficulty, with-

out reward. Visitors from Springfield,

Marietta, Cincinnati, Cleveland,

and other places, called upon me for

information and got it free of

charge. A Professor Garlick, however,

insisted upon making some com-

pensation, and gave me a splendidly

bound book of steel engravings of

the London Art Gallery.

"I will finish this by stating

that, except those made by myself, I

never saw a daguerreotype until the fall

of 1841. I was frequently told

by persons who had seen other pictures,

that mine were far superior to

any they had seen, although not so sharp

in the outline as those taken

with the achromatic lens. Mine were

strong and bold, and could be seen

in any position. I received the first

premium at the Mechanics' Institute

exhibition at Cincinnati in June 1812. I

will now refer back to the buff.

I found the superiority of my pictures

was altogether in the manner in

which I polished my plates

"All others at the beginning

followed Daguerre's process to the let-

ter, and being a silversmith I knew that

with the buff was the only pos-

sible way that a silver plate could be

brought to a high polish, and as

Daguerre said, 'the higher the polish

the better.' I kept it no secret; it

soon came into general use, and some few

years after some one got out a

patent for the buff wheel. If I could

see you I could tell you many little

incidents about the daguerreotype

flattering to me, but I do not care to

write them out.'"

Judge James Sheward, late of Dunkirk, N.

Y., formerly

of Zanesville, wrote a number of articles

for the Courier of the

latter city and signed them "Black Hand." In one of these

70 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

he included the foregoing extract from a

letter written to him

by Ross, but not intended for

publication. The two were life-

long friends.

The details of Daguerre's procees seem

to have been pub-

lished in London, August 26,

1839. As there were no regular

steamship lines across the Atlantic at

that time, it must have

been several weeks later when

publication was made in America.

Ross may therefore have been the first

to make a daguerreotype

on this side of the Atlantic.

Col. R. B. Brown, of Zanesville, who was

intimately ac-

quainted with Ross, in a letter to the

writer says:

"You will note that Mr. Ross's

pictures were made in November,.

1839, following the publication of the

description of the Daguerre pro-

cess in a French journal the latter part

of August of that year. The trans-

lation was printed in New York as soon

as the mail could bring the

article, and I am sure that you will

make no mistake in the claim that

A. C. Ross made the first daguerreotype

in the United States. Of this I

know Mr. Ross never had a doubt, but I

have heard him say, as he has

been quoted, 'I made the first west of

the Alleghanies.' To me he always

claimed, 'I made the first in this

country.' I believe it, and I do not

believe that the statement can be

disproved."

As first practiced, the process required

long exposure, and

was applied successfully only to

inanimate objects. Dr. Draper

introduced many improvements. Ross

followed these closely,

and soon made excellent pictures, with

apparatus of his own

manufacture.

No sooner had the Morse system of

telegraphy been an-

nounced than he began to test it

experimentally. When the first

line reached Zanesville, in 1847, he was

so familiar with the

practical working of the invention that

he took charge of the

office and became the first telegraph

operator of the city.

In a similar manner he constructed from

written descriptions

the telephone, and even the phonograph,

before either was brought

to the city. When the latter was finally

put on exhibition there,

a friend called and invited him to see

and hear it.

"It is not at all necessary or

worth my while," said he. "I

have had for some days a machine of my

own make that works

very satisfactorily."

Song Writers of Ohio. 71

As his father had followed the chase

with keen zest, the son

found interest in the study of natural

history and taxidermy, and

choice specimens usually adorned the

windows of his jewelry

store.

In his later years, he devoted a part of

his leisure to water-

color painting, and did work that might

well have been the envy

of the professional.

His scientific reading led him early

into the investigation of

gas lighting. He organized the first

company to offer this illu-

minant to the city, and, as its

president, conducted this business

venture with marked success.

When an express office was opened in

Zanesville he was

chosen agent. He retired from the

jewelry business in 1863.

Four years later he withdrew from the

management of the

express office, to devote his entire

time to the gas company and

the insurance business. He was the

guiding spirit in these

interests until a few days before his

death.

His was a fervent patriotism. He was

president of the

War Association of Muskingum County in

the early sixties. He

thoroughly understood military tactics,

was an officer in a local

independent company, and at the outbreak

of the Civil War

drilled numerous members of the

"awkward squad," General

M. D. Leggett among them. His son,

Charles H. Ross, served

the Union cause in the field till the

flag waved over a united

country.

Modest and unassuming in his demeanor,

he was blessed

with a large degree of public spirit,

and was ever ready to lend

his valuable aid to the industrial and

moral upbuilding of the

community.

This versatile son of Ohio was a lover

of music, too. "He

used to tell how, when a little boy, the

young men of the town

sent him to the circus to learn the

popular airs, which, in those

days, were always sung by the clown. The

visit to the circus

answered two purposes, as he always

reproduced the best fea-

tures, such as tight-rope dancing,

vaulting and tumbling, for the

benefit of the school, as well as

singing the songs till the young

men learned them." At the age of

fifteen he began to play on

the clarionet. He had a good voice,

became a member of the

72 Ohio Arch.

and Hist. Society Publications.

local church choir, and was later in

demand on occasions requiring

the services of an entertaining

vocalist.

Of his experience in New York City, his

daughter writes:

"When a boy of twenty he became a

member of one of the first

orchestras organized in New York

City-led by Uri Hill-playing 'by ear'

the first clarionet. Music was always

his passion, and he had opportunities

when in New York on business to hear all

the best musicians. When he

returned to Zanesville to reside, the

citizens reaped the benefit, for through

his individual efforts all the first

troupes traveling came to Zanesville and

he made many warm friends among

them."

The wave of Whig sentiment that swept over

the country in

the later thirties rose to tidal height

in the memorable campaign

of 1840. To the movement, Alexander

Coffman Ross contrib-

uted a service that helped to swell the

enthusiasm for "Old Tip-

pecanoe," and carried the fame of

the "Buckeye boys" and the

Buckeye State to every home in the

Union.

Though the theme might warrant the

digression, space will

not permit a general survey of the great

uprising in support of

William Henry Harrison - unfortunately

designated in history

as the "log cabin and hard cider

campaign." If the political

foes of that grand old patriot helped to

their own immediate

undoing in derisively referring to him

as the "log cabin, hard-

cider candidate," in the long run

they would seem to have accom-

plished something of their purpose, to

have detracted from the

movement and the man, when a twentieth

century historian can

sit down and calmly write:

"In the campaign referred to a log

cabin was chosen as a symbol

of the plain and unpretentious

candidate, and a barrel of cider as that of

his hospitality. During the campaign,

all over the country, in hamlets,

villages, and cities, log cabins were

erected and fully supplied with barrels

of cider. These houses were the usual

gathering places of the partisans

of Harrison, young and old, and to every

one hard cider was freely given.

The meetings were often mere drunken

carousals that were injurious to

all, and especially to youth. Many a

drunkard afterwards pointed sadly

to the hard cider campaign in 1840, as

the time of his departure from

sobriety and respectability."

Doubtless drunken brawls sometimes

attended the big dem-

onstrations of the campaign. It is not true, however, that they

Song Writers of Ohio. 73

were peculiar to it or that the uprising

was a wild, bacchanalian

orgie in honor of the fermented juice of

the orchard and kin-

dred spirits.

General Harrison had lived in a log

cabin. He was for a

number of years a poor farmer. But it

was not because of this

that he was nominated for the

presidency. He was simple,

direct, hospitable and kind, but he was

more. He was courage-

ous, he was honest, he was a man of

affairs. On the field and

in the forum he had proven his

patriotism and statesmanship.

Though surpassed in constitutional lore

and forensic power by

Webster and Clay, he was an orator of no

mean ability, prepared

his own addresses, and delivered them

with an effectiveness

rarely surpassed by a candidate for the

presidency.

The personality of General Harrison,

however, was not the

occasion of the political upheaval of

1840. It was the rising of

the people in their might to smite the

ruling autocracy. For

twelve years the Republic had been ruled

by one man. General

Jackson will ever be honored for

repelling the invader at New

Orleans and suppressing nullification in

South Carolina, but it

is putting it mildly to say that in his

administrations he levied

upon the American people a heavy tribute

for his services. He

played politics to the limit. By

profession and practice he was a

spoilsman. Entering upon his duties with

the declaration that the

President should be ineligible for

re-election, he did everything

in his power to pave the way to succeed

himself in office.

At the close of his second term, he used

the political machine

that he had built up to dictate the

nomination of his successor.

Not satisfied to pause here, he had Van

Buren renominated for

a second term. Every appointive office

was filled by a man whose

first duty was to Jackson. The public

service exhibited the inev-

itable results of the spoils system -

insolence and incompetence.

The Jacksonian regime dominated the body

politic. It dic-

tated nominations, national, state and

local. Governors, judges

and country "'squires" bowed

to its sway. At length its fruit

began to ripen. Defalcations were

frequent; "leg treasurers"

were numerous. "Business generally

was at a standstill; the cur-

rency was in such a confused state that

specie to pay postage

was almost beyond reach ; banks had been

in a state of suspen-

74 Ohio Arch. and Hist.

Society Publications.

sion for a long time; mechanics and

laboring men were out of

employment or working for 621/2, 75, or 871/2 cents a day, payable

in 'orders on the store;' market money

could be obtained with

difficulty, and things generally had

reached so low an ebb as to

make any change seem desirable."

The people, goaded to desperation,

resolved to dethrone the

dictator and restore the republic to the

ideal of the fathers. Pre-

paratory to their supreme effort to

dislodge a desperate and thor-

oughly organized foe from the places of

power, the Whigs and

independent voters of the country chose

Harrison as their leader,

and they chose well. Those who have read

his speeches, espe-

cially the one delivered at Dayton, and

his inaugural address, can

but regret that he did not live to carry

out the reforms to which

he gave eloquent approval.

The campaign opened with a burst of

enthusiasm that sur-

prised the Whig leaders almost as much

as their opponents. On

the 22d of February, 1840, twenty

thousand people from all

parts of the state met in convention at

Columbus, O., to ratify

the nomination of Harrison and Tyler.

From places near and

remote they came. Some had spent days on

the journey. An

eye-witness thus describes the scene

presented in the capital city

on that memorable occasion:

"The rain came down in torrents,

the streets were one vast sheet of

mud, but the crowds paid no heed to the

elements. A full-rigged ship

on wheels, canoes, log cabins, with

inmates feasting on corn-pone and

hard cider, miniature forts, flags,

banners, drums and fifes, bands of

music, live coons, roosters crowing, and

shouting men by the ten thousand,

made a scene of attraction, confusion,

and excitement such as has never

been equaled. Stands were erected, and

orators went to work; but the

staid party leaders failed to hit the

key-note. Itinerant speakers mounted

store-boxes, and blazed away. It was

made known that the Cleveland

delegation, on their route to the city,

had had the wheels stolen from some

of their wagons by Locofocos, and were

compelled to continue their jour-

ney on foot. One of these enforced

foot-passengers was something of a

poet, and wrote a song descriptive of

'Up Salt River,' and was encored

over and over again. On the spur of the

moment, many songs were

written and sung; the pent-up enthusiasm

had found vent."

The spirit of the movement pervaded

every rank. The busi-

ness man, the recluse and the scholar

touched elbows with lusty

Song Writers of Ohio. 75

farmers, waded in the mud and helped to

swell the universal

shout.

In the procession was a cabin on wheels

from Union County.

It was made of buckeye logs, and in it

was a band of singers

discoursing, to the tune of Highland

Laddie, the famous Buckeye

song, written for the occasion by

perhaps the first Ohio poet of

his time, Otway Curry:

Oh, where, tell me where, was your

Buckeye cabin made?

Oh, where, tell me where, was your

Buckeye cabin made?

'Twas built among the merry boys that

wield the plow and spade,

Where the log cabin stands, in the

bonnie Buckeye shade.

Oh, what, tell me what, is to be your

cabin's fate?

Oh, what, tell me what, is to be your

cabin's fate?

We'll wheel it to the capital, and place

it there elate,

For a token and a sign of the bonnie

Buckeye State!

Oh, why, tell me why, does your Buckeye

cabin go?

Oh, why, tell me why, does your Buckeye

cabin go?

It goes against the spoilsmen, for well

its builders know

It was Harrison that fought for the

cabins long ago.

Oh, what, tell me what, then, will

little Martin do?

Oh, what, tell me what, then, will

little Martin do?

He'll "follow in the

footsteps" of Price and Swarthout too,

While the log cabin rings again with old

Tippecanoe.

Oh, who fell before him in battle, tell

me who?

Oh, who fell before him in battle, tell

me who?

He drove the savage legions, and British

armies too

At the Rapids, and the Thames, and old

Tippecanoe!

By whom, tell me whom, will the battle

next be won?

By whom, tell me whom, will the battle

next be won?

The spoilsmen and leg treasurers will

soon begin to run!

And the "Log Cabin Candidate"

will march to Washington!

"But," said Judge Sheward, of

Zanesville, "the song of the

campaign had not yet been written."

He then proceeds with the

following account of its origin and

progress to popularity:

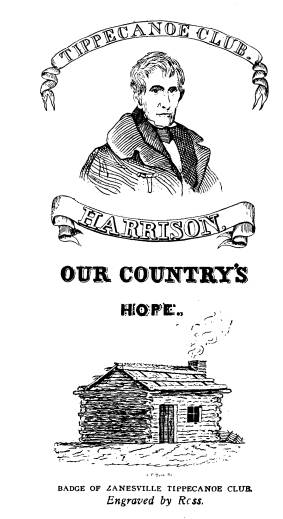

"On the return of our delegation a

Tippecanoe Club was formed,

and a glee club organized, of whom Ross

was one. The club meetings

|

76 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications. |

|

|

Song Writers of Ohio. 77

were opened and closed with singing by

the glee club. Billy McKibbon

wrote 'Amos Peddling Yokes,' to be sung

to the tune of 'Yip, fal, lal,'

which proved very popular; he also

composed 'Hard Times,' and 'Martin's

Lament.' Those who figured in that day

will remember the chorus:

Oh, dear! what will become of me?

Oh, dear! what shall I do?

I am certainly doomed to be beaten

By the heroes of Tippecanoe.

"This song was well received, but

there seemed something lacking.

The wild outburst of feeling demanded by

the meetings had not yet been

provided for. Tom Lauder suggested to

Ross that the tune of Little Pigs

would furnish a chorus just adapted for

the meetings. Ross seized upon

the suggestion, and on the succeeding

Sunday, while he was singing as

a member of a church choir, his head was

full of 'Little Pigs,' and efforts

to make a song fitting the time and the

circumstances. Oblivious to all

else, he had, before the sermon was

finished, blocked out the song of

Tippecanoe and Tyler, too. The line, as originally composed by him of

Van, Van, you're a nice little man,

did not suit him, and when Saturday

night came round he was cudgelling

his brains to amend it. He was absent

from the meeting, and was sent

for. He came, and informed the glee club

that he had a new song to

sing, but that there was one line in it

he did not like, and that his delay

was occasioned by the desire to correct

it.

'Let me hear the line,' said Culbertson.

Ross repeated it to him.

'Thunder!' said he, 'make it-Van's a used-up

man!'- and there

and then the song was completed.

"The meeting in the Court House was

a monster, the old Senate

Chamber was crowded full to hear

McKibbon's new song, Martin's La-

ment, which was loudly applauded and encored. When the first

speech

was over, Ross led off with Tippecanoe

and Tyler, too, having furnished

each member of the glee club with the

chorus. That was the song at

last. Cheers, yells, and encores greeted

it. The next day, men and boys

were singing the chorus in the street,

in the work shops, and at the table.

Olcot White came near to starting a hymn

to the tune in the Radical

Church on South street. What the Marseillaise

Hymn was to Frenchmen,

Tippecanoe and Tyler, too, was to the Whigs of 1840.

"In September, Mr. Ross went to New

York City to purchase goods.

He attended a meeting in Lafayette Hall.

Prentiss, of Mississippi, Tall-

madge, of New York, and Otis, of Boston,

were to speak. Ross found

the hall full of enthusiastic people,

and was compelled to stand near the

entrance. The speakers had not arrived,

and several songs were sung to

keep the crowd together. The stock of

songs was soon exhausted, and

78 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

the chairman (Charley Delavan, I think)

arose and requested any one

present who could sing, to come forward

and do so. Ross said, 'If I could

get on the stand, I would sing a song,'

and hardly had the words out

before he found himself passing rapidly

over the heads of the crowd,

to be handed at length on the platform.

Questions of 'Who are you?'

'What's your name?' came from every

hand.

'I am a Buckeye, from the Buckeye

State,' was the answer. 'Three

cheers for the Buckeye State!' cried out

the president, and they were

given with a will. Ross requested the

meeting to keep quiet until he had

sung three or four verses, and it did.

But the enthusiasm swelled up

to an uncontrollable pitch, and at last

the whole meeting joined in the

chorus with a vim and vigor

indescribable. The song was encored and

sung again and again, but the same

verses were not repeated, as he had

many in mind, and could make them to

suit the occasion. While he

was singing in response to the third

encore, the speakers, Otis and Tall-

madge, arrived, and Ross improvised:

We'll now stop singing, for Tallmadge is

here, here, here,

And Otis, too,

We'll have a speech from each of them,

For Tippecanoe and Tyler, too, etc.

The song, as originally written, was as

follows:

TIPPECANOE AND TYLER, TOO.

What has caused the great commotion,

motion, motion,

Our country through?

It is the ball a rolling on,

CHORUS.

For Tippecanoe and Tyler, too-Tippecanoe

and Tyler, too;

And with them we'll beat little Van,

Van, Van.

Van is a used-up man;

And with them we'll beat little Van.

Like the rushing of mighty waters,

waters, waters,

On it will go,

And in its course will clear the way

Of Tippecanoe, etc.

See the Loco standard tottering,

tottering, tottering,

Down it must go,

And in its place we'll rear the flag

Of Tippecanoe, etc.

Song Writers of Ohio. 79

Don't you hear from every quarter,

quarter, quarter,

Good news and true,

That swift the ball is rolling on

For Tippecanoe, etc.

The Buckeye boys turned out in

thousands, thousands,

Not long ago,

And at Columbus set their seals

To Tippecanoe, etc.

Now you hear Van Jacks talking, talking,

talking,

Things look quite blue,

For all the world seems turning round

For Tippecanoe, etc.

Let them talk about hard cider, cider,

cider,

And log cabins, too,

'Twill only help to speed the ball

For Tippecanoe, etc.

The latch-string hangs outside the door,

door, door,

And is never pulled through

For it never was the custom of

Old Tippecanoe, etc.

He always had his table set, set, set,

For all honest and true,

And invites them to take a bite

With Tippecanoe, etc.

See the spoilsmen and leg treasurers,

treas, treas,

All in a stew,

For well they know they stand no chance

With Tippecanoe, etc.

The fourth stanza was frequently changed

to adapt the song

to the different states. Other stanzas were added to suit

par-

ticular localities and special

occasions. A modern historian, who

evidently did not know who wrote it,

speaks of it as the "most

popular song of the campaign," and

says that it had, "by the

inventive song-genius of Horace Greeley

and scores of other

less famous poets been extended to every incident and

sentiment

of the day." The following final stanza was frequently used in

the Ohio campaign:

80 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

Now who shall be our next governor,

governor,

Who, tell me who?

Let's have Tom Corwin, for he's a team

ForTippecanoe and Tyler, too-Tippecanoe

and Tyler, too,

And with him we'll beat Wilson Shannon,

Shannon,

Shannon is a used-up man,

And with him we'll beat Wilson Shannon!

It has been said that the song is poor

poetry, and judged by

literary standards this is certainly

true, but the alliteral chorus

is remarkably musical and

"catchy" and the stanzas abound in

homely truth and telling hits. It is

needless to say that it was

readily understood by all classes. The

composition probably

surpassed all others in popularity,

because it more nearly met the

demands of the hour.

The reference to the "ball that's

rolling on" is worthy of

notice in passing. Just when the

"ball" began to roll in Amer-

ican political literature has perhaps

not yet been definitely deter-

mined. Thomas H. Benton has been

given the credit of starting

it. Its origin probably dates some years

prior to the Harrison

campaign. It must be admitted, however,

that the "ball," like

the "buckeye," was invested

with a new significance and a wider

currency in the year 1840, and the song

written by Ross was

probably the first that "set the

ball in motion."

In an account of the Young Men's Whig

convention, at

Baltimore, May 4, 1840, is found the

following description of

one of the features of the Maryland

section of the procession:

"A curious affair followed here,

which was immediately preceded

by a flag announcing that 'Alleghany is

coming.' It was a huge ball,

about ten feet in diameter, which was

rolled along by a number of the

members of this delegation. The ball was

apparently a wooden frame

covered with linen, painted divers

colors, and bearing a multitude of

inscriptions, apt quotations, original

stanzas and pithy sentences."

At the convention in Nashville, Tenn.,

August 17th, one of

the leading attractions was described as

follows:

"The great ball, from Zanesville,

Ohio, which came safe to hand on

the steamer Rochester, on Saturday

night, occupied a conspicuous place

in the procession. It was given in

charge of the Kentucky delegation,

and was hauled on four wheels, under the

immediate care of Porter,

Song Writers of Ohio. 81

the Kentucky giant. The ball is in the

form of a hemisphere, moving

upon its axis and representing each of

the individual states of the Union."

Ross's daughter gives the following

additional information:

"There was a real ball that

illustrated the song. It was an immense

thing made at Dresden, Ohio, and at

great political meetings it was

drawn in the procession by twenty-four

milk white oxen. It was after-

wards taken to Lexington, Kentucky, but

not by oxen."

The Annapolis Tippecanoe Club, on August

18th, celebrated

the progress of the cause in a song

entitled "The Whig Ball."

It began as follows:

Hail to the ball which in grandeur

advances,

Long life to the yeoman who urge it

along;

The abuse of our hero his worth but

enhances;

Then welcome his triumphs with shout and

with song.

The Whig ball is moving!

The Whig ball is moving!

The big ball started from Zanesville was

probably the inspi-

ration for the foregoing and similar

effusions that broke forth

about this time. At other great meetings

throughout the country

the ball literally "went rolling

on."

It is perhaps needless to say that there

have been rival claim-

ants for the honor of authorship of Tippecanoe

and Tyler, too.

Fortunately, their pretentions, with a

single exception, have not

been sufficiently serious to merit

attention. Henry Russell, the

famous English singer, who seems in his

later years to have

developed a penchant for claiming

pretty much everything that

has been written in his line, in his

autobiography, gives the fol-

lowing account of the initial launching

of the song on its voyage

to popularity:

"About this time, (1841) the

presidential election was causing great

excitement in America. The rival candidates

for the presidency were

Martin Van Buren, Democrat; and General

Harrison, Whig.

* *

* *

"I was one day sitting in the

office of the Boston Transcript, and to

beguile the time while waiting for my

friend, Houghton, the editor and

proprietor, I sat idly turning over the

pages of some of the numerous

exchange journals with which the office

table was littered, when my at-

Vol. XIV- 6.

82 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

tention was attracted by a poem on the

subject of the forthcoming elec-

tion. The name of the paper it appeared

in has escaped my memory, but

the poem was called

"Tippecanoe," after the famous battle fought and

won by General Harrison.

"I only remember now the chorus,

which ran as follows:

For Tippecanoe and Tyler, too, for

Tippecanoe and Tyler, too -

With them we'll beat little Van

Van! Van! Van! a used up man,

With them we'll beat little Van.

"I had a singular remembrance of an

old Irish song, known by the

poetic title of "Three little pigs

lay on very good straw," the chorus of

which ran thus:

Lila bolara, Lila bolara, Lila bolara,

och hone,

For my dad is a bonny wee man, man, man,

man!

My dad is a bonny wee man,

"Almost unconsciously I put the

words of the poem before me to the

melody of the old Irish song, and when

Houghton came in I sang them

over to him.

"He appeared delighted, and at his

suggestion, I sang the song from

the window of the Boston Transcript, to

an enormous crowd which had

assembled in the street below. The song

was hailed with enthusiasm by

the Harrison party, and it spread like

wildfire through the States, where

it is sometimes sung even to this day.

"Such is the true origin of this at

one time popular election song.

There has been much discussion about it

from time to time in the Amer-

ican press, and while I do not claim to

have written either the words or

the music, I do claim to have adapted

the one to the other- wedded them

together, as it were--and giving the

song its start in life by singing it

from the window of the office of the Boston

Transcript."

It is scarcely necessary to observe that

the song had become

popular before it was printed, that it

was written to the tune of

Little Pigs, and that Russell did not see it until long after it

had been sung. It will be noted that he has made a mistake of

one year in the date of the campaign and

that he is very indefi-

nite in regard to the time of his

rendition of the song in Boston.

He does not state the occasion of the

assembling of the "enor-

mous crowd" in the "street

below," so opportunely after he "sat

idly turning over the pages of some of

the numerous exchange

journals." One might infer that the

people just happened around

Song Writers of Ohio. 83

in order to be convenient when the song was sung. It is entirely

probable, however, that on some occasion

Russell sang the words

to the melody. The peculiar measure

would naturally suggest

the air.

It is not necessary to dwell on the

results of the remarkable

political contest that called forth the

song. The thoroughly

trained Jacksonian organization, under

the skilful leadership of

the "Little Magician," was

overwhelmed by the spontaneous

uprising of the country. The

enthusiastic hosts, with music and

song, inducted victorious "Old

Tippecanoe" into office. Shortly

afterward, the new President was laid

low by the hand of death.

There was mourning throughout the land,

and the fruits of

triumph turned to dust on the lips of

the victors.

Alexander Coffman Ross continued to

apply himself assid-

uously to the jewelry business and to

devote his leisure to sci-

ence and music. He composed no airs, but

wrote the words of

a number of songs, some of which were

published in the local

papers.

He addressed the local medical society,

of which he was

an honorary member, on scientific

subjects; lectured on the

latest applications of electricity and

magnetism before the stu-

dents of Putnam Seminary; corresponded

with Louis Agassiz

and Professor Joseph Henry. He was an

ardent admirer of

the latter and insisted that to him

rather than to Morse belongs

the honor of having invented the

electric telegraph. Among his

letters is one from Spencer F. Baird,

the famous naturalist and

secretary of the Smithsonian

Institution, thanking him for a

contribution on "Flint

Ridge." This was published in the

Smithsonian Report for 1879. As an early

contribution to this

branch of Ohio archaeology, it is

appended to this sketch.

One of his daughters, Elizabeth B. Ross,

was a good singer,

studied harmony and wrote the words and

music of a number of

songs, some of which have had a wide

sale. We here reproduce

the words of two:

LITTLE BIRD, WHY SINGEST THOU?

Little bird, why singest thou,

So merrily, so blithe and gay,

Hast thou ne'er a care to mar

|

84 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications. |

|

|

Song Writers of Ohio. 85

The pleasure of the passing day?

I sing, for ah! my heart's so light,

No care or thoughts oppress me;

And this my song from morn till night,

I warble free.

Little bird, where dwellest thou,

Thro' chilling winter's icy reign;

Dost thou fly from bough to bough

And warble forth thy glad refrain?

Oh yes, I fly to warmer climes,

When first I feel cold winter's breath,

And there amid the southern pines,

I warble free.

LIST TO THE NIGHTINGALE.

Come, come with me, dear one,

Where moonbeams are glancing

And stars beaming brightly,

Oh! come, then, with me.

Come, then, and we'll wander

Where waters so sparkling

Are laving the green earth,

Oh! come, then, with me.

List, to the nightingale singing o'er

meadow,

Trilling a vow to the one that he loves.

Then come, oh! come, my dear one,

And, like the bird of night,

Give thy heart to the one

Who now sues for thy love.

Ross was very popular with the large

German element of

Zanesville, and one of the last

occasions on which he sang in

public was at a banquet given by the

German citizens in the

autumn of 1869 in celebration of the

centennial anniversary of

the birth of Von Humboldt. He requested his daughter Ellen

to write him some words to the Marseillaise Hymn. These he

sang to the delight of those who heard

him. One stanza was as

follows:

We sing to-day a nation's glory,

Germania hails her honored son!

But not to her belongs the story,

In every land his fame was won.

|

86 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications. From Asia's sunny mountain peaks To Mexicana's scorching plain, His natal day is kept again; O'er all the world his voice still speaks. CHORUS. Then swell the choral song To hail Von Humboldt's name! Rejoice! Rejoice! The nation's throng To celebrate his fame. |

|

|

|

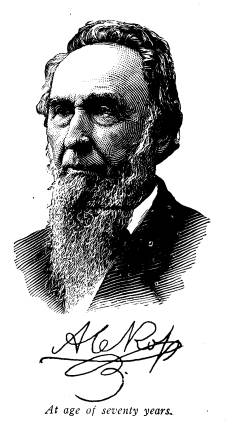

The author of the famous campaign song of 1840 passed the allotted three score years and ten. He was, first of all, a public spirited citizen and systematic business man. His recreations were the pursuits that brought him local fame along the lines already noted. Of him it was truly said, "There were few things that he had not done, and done well, and fewer that he cared to do except as a pastime." After a brief illness, he died February 26, 1883. His loss was keenly felt by the city with which he had been identified |

Song Writers of Ohio. 87

through his entire life. The local

military company and other

organizations expressed a desire to

attend the funeral in a body,

but the family, while appreciating the

kind intentions, obeyed

the wishes of the departed in dispensing

with all parade and

display.

Of his family, his wife and three

children, Misses Elizabeth

B. and Ellen, of Zanesville, 0., and

Major Charles H., of Mil-

waukee, Wis., are still living.

His memory is fondly cherished by those

who knew him.

Though not endowed with what is called

"creative genius," he

wrote a song that became national in

celebrity and influence, and

acquired enduring fame in his Tippecanoe

and Tyler, too.

FLINT RIDGE.

Flint Ridge lies in Licking and

Muskingum counties, about three

miles south-eastward from Newark, and

twelve to fifteen miles west-

northwest from Zanesville. It extends

eight miles southwest by north-

east and is from one-fourth of a mile to

one mile wide. The ridge

is cut by hollows, ravines and gorges.

Portions of the highest land are

comparatively level, and this plateau is

underlaid by a stratum of flint

rock from fifteen inches to three feet

in thickness. Besides this stratum

are numerous flint bowlders standing up

several feet above the surface

of the ground. On the exact level of the

flint are the "diggings" hundreds

of which may be seen, which range in

depth from one or two to thirty

feet, their depth depending upon the

relation of the flint stratum to the

surface of the earth. The very deep

diggings are from the top of a hillock

on the summit of the Ridge. The trenches

are from a few feet to thirty

feet across at the top, all sloping so

gradually that it would be easy to

walk down them. From the deeper cuts the

earth appeared to have been

carried out; the one from the top of the

hillock is still very deep, and

was about forty feet in perpendicular

when completed, with proportional

width. In one portion was a drift sixty

to eighty feet in length, six to

eight feet wide, and four to five feet

high. The excavation was pursued

with the same diligence when there was

no flint as when the stratum

was found, and was of the same

character, to the same level. Of course,

when the earth is below the flint level

there is no evidence of digging,

but when the earth is above that level

the work extends to the flint. These

works follow the dip of the flint

towards east-northeast until the hills

became too high above the stratum. In a

meadow, and near a stream of

water on land very much lower than the

ridge, occurred a bed of crumbled

|

88 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications. flint and sandstone. This bed was about fourteen inches in depth, seven feet across, and fifteen to eighteen feet in length. The sandstone was near the north part and had been subject to great heat. A quantity of ashes was mixed through the whole bed. Several such beds are re- ported in that vicinity, and were generally near the water. No arrow- heads or other objects made of flint occurred. Old, gnarly, full-grown oaks, some of them three hundred years old, have sprouted and grown since these excavation were made. There has not been any sign of a workshop discovered in the last sixty years, but at the point usually sought by visitors and curiosity hunters flint spalls cover the ground for acres. Only one arrow-head has been found there for years. A. C. Ross in Smithsonian Report for 1879, page 440. ROSS FAMILY. Following are the names of the children of Elijah and Mary Ross in the order of dates of birth: Theodore, Elizabeth, Alex- ander Coffman, Mrs. Anne Fox, Mrs. Margaret Boyd, Mrs. Ruth Hurd, James, Mrs. Jane Stewart, George, Mrs. Harriet Brown, Mrs. Elvira Keene and Thomas. Alexander's immediate family, whose names occur in the preceding sketch, are all still living. Mrs. Ross was the daughter of Oliver Granger who, with his brothers, Ebenezer, Henry and James, came to Ohio from Suffield, Connecticut, where their ancestors had lived since 1640. |

|

|

SONG WRITERS OF

OHIO.

ALEXANDER COFFMAN ROSS.

AUTHOR OF "TIPPECANOE AND TYLER,

TOO."

"I am a Buckeye, from the Buckeye

State." This was the

proud declaration of the author of Tippecanoe,

and Tyler, too,

as he faced a large and enthusiastic

audience in New York City,

just before he gave to fame that

political campaign song-the

most effective ever sung in the history

of the Republic.

Alexander Coffman Ross first opened his

eyes to the light

in Zanesville, O., May 31, 1812. His

father, Elijah Ross,l born

in Brownsville, Pa., November, 1786,

located in Zanestown,

(Zanesville) in 1804, and died

there February 29, 1864. He was

a soldier of the War of 1812, and, being

a gunsmith, was ordered

to remain in his home town to repair

guns, swords and accoutre-

ments. His wife, whose maiden name was

Mary Coffman, was

born at Fredericktown, Pa., September

10, 1788, and died in

Zanesville December 29, 1862. Their family

numbered twelve

1In 1804, Elijah Ross came to Zanestown

(Zanesville) and prospected

through the Muskingum and Miami valleys.

He was a gunsmith by trade,

the first of this section, and soon

after his arrival in the new country

settled in the village and erected a

cabin, which served as dwelling and

shop, on what is now the northeast

corner of Locust alley and Second

street. At the beginning of the War of

1812, he entered the service as

third corporal, and was detailed to

remain at home and repair arms for

the soldiers. In 1816 he moved to West

Zanesville. In 1823 he returned

to the east side of the river, where he

continued to work at his trade.

He bored his own gun barrels, made the

first blow-pipes there used for

blowing glass (1815), and sometimes

aided the glass-blowers in their

work. He was especially fond of fox

hunting, and seemed never hap-

pier than when following his hounds over

the Muskingum hills. A genial,

unassuming man and a total abstainer

from intoxicants, he lived to the

ripe age of seventy-nine years, and died

respected for his industry and

honesty. (62)

(614) 297-2300