Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

|

JOHN STEWART PIONEER MISSIONARY OF THE METHODIST EPISCOPAL CHURCH.

N. B. C. LOVE, D.D. The Methodist Episcopal Church from its organization in 1773 was missionary in its spirit. It made continuous efforts |

|

|

|

dots, and the founder of the first Methodist Episcopal Mission among the heathen. Before the advent of Stewart the most cruel and bloody practices obtained among the Wyandots. In this respect they were not different from the other Indian tribes of the North- west. The burning of Col. Crawford, when a prisoner, is evi- dence of this. Even the women and children participated in torturing him. We need not repeat the story here. The Wyan- dots were the leaders in this savage deed. Between-the-Logs, it is claimed, was a participant, and such were the people to whom Stewart carried the gospel of love and peace The Wyandots for a long period stood politically at the head of an Indian Federation of tribes and so were recognized by the United States Government in the treaties made with the Indians of the old Northwest Territory. The names of chiefs of the Wyandot nation appear first prominently on the treaty made at Greenville in 1795 between Vol. XVII-22. (337) |

|

338 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications. the Government and the Indians, Gen. Wayne acting for our Government. While the itinerant Bishops Asbury and McKendree and their worthy helpers were denied the honor of inaugurating the great missionary movement among the heathen, they are to be honored for their unselfishness in giving their co-operation and support to John Stewart, an humble mulatto layman, who had been converted through their preaching, and whom they recog- nized as having received the call of God. |

|

|

|

to desist and reform. Although failing several times in his ef- forts, he at last succeeded. He listened to the preaching of the Gospel by the Methodists and was converted. Finding no Baptist Society convenient, he united with the Methodist Episcopal Church. Here he was at home. The prayer and class meeting were delightful to him, and all his prejudices against the Methodists gave way. He also prospered in business and saved some money. The grand- father of Bishop McCabe was his class leader and personal friend. Stewart has been described to me by two pioneers who knew him well. He was a light mulatto, about five feet, eight inches high, weighing about one hundred and forty pounds; well formed, |

John Stewart. 339

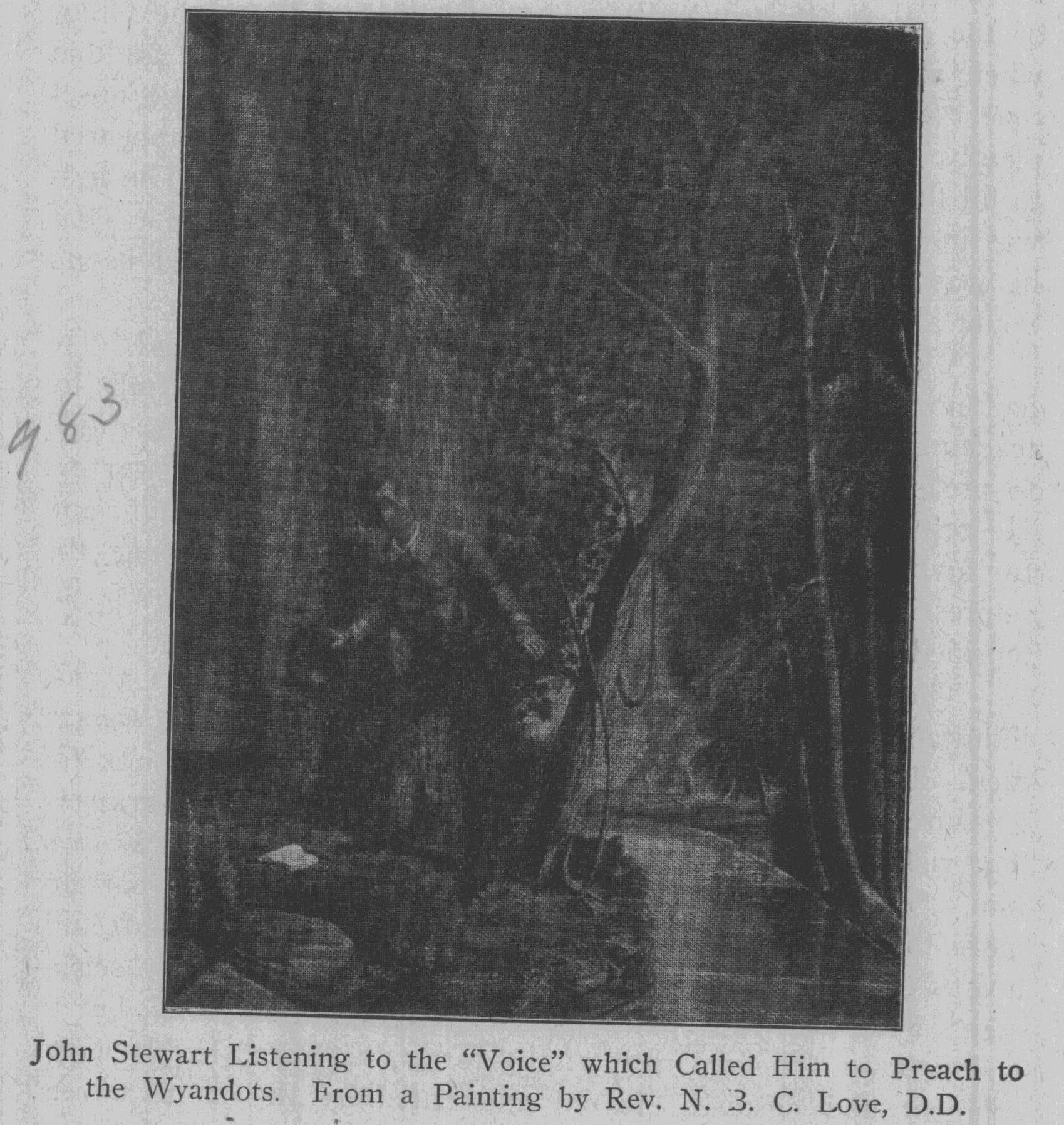

erect in carriage, easy and graceful in

movement. His features

were more European than African. He had

a tenor voice, and

was gifted in song.

He often went into the fields or forests

to meditate, to study

the Bible and to pray. On Sabbath

evening he was in the edge

of the woods by the side of a rivulet

that ran into the Ohio,

when a voice from the sky seemed to say

to him in audible

tone, "Thou shalt go to the

Northwest and declare my counsel

plainly." As he listened and

looked, a peculiar halo appeared

to fill the Western sky. This summons

was repeated. The first

was in the voice of a man, the second

that of a woman. That

he was honest in the thought of this

calling there need be no

doubt.

A deep impression was made on his

astonished mind. He

had no thought of preaching; he felt he

would obey fully by

teaching and exhorting, but when a

friend told him he was called

to preach he rebelled, feeling he was

not prepared nor worthy.

He resolved to go to Tennessee, but

sickness came to him, and

for awhile his life was despaired of,

but finally recovering, the

impression that it was his duty to go to

the Northwest was in-

tensified.

The Northwest, beyond a fringe of

settlements, was a vast

illimitable wilderness, occupied by

savage beasts and as savage

men. He resolved to go, not for gain,

nor for fame, nor for

pleasure, but to save souls from the

bondage of heathen darkness.

The risks were many, but he felt that an

unseen hand was over

him. Starting on his journey, he knew

not whither he went any

more than Abraham of old. His friends

tried to persuade him

not to go, and having started, those

whom he met in the settle-

ments also tried such persuasion, or

laughed at his folly, but to

no purpose. The red men of the forest,

neglected by the Gov-

ernment and despised, feared and hated

by the frontiersmen,

were upon his mind. He believed they

were dear to the heart of

Jesus.

He went on, keeping towards the

Northwest, wading

streams, camping alone at night, unarmed

in the primeval for-

ests, enduring hunger and many other

hardships. After the

severe toil of days and exposure of

nights, he came to the vil-

|

340 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

lage of the Delawares-on the headwaters of the Sandusky River. The Indians extended to him the hospitality of their cabins. Here he held religious worship, singing, praying and telling the story of the dying love of Jesus until late at night, then, retiring, he fell asleep, feeling that his mission was ac- |

|

|

|

complished and that he would start on his homeward journey in a day or two. With the dawn of the morning, however, he awoke and heard an inward voice telling him to go farther. Having inquired the way, he started again on his pilgrimage. The first afternoon he came to the cabin of a white family |

John Stewart. 341

and was refused admittance by the wife

until the return of her

husband. Upon the husband's arrival,

while supper was pre-

paring, Stewart sang some sweet songs,

which charmed the

backwoodsman and his family. He offered

to hold services at

night, and the boys were sent post haste

by the father to the

few residents in the vicinity. Stewart

had about a dozen in his

congregation to whom he expounded the

Gospel, and sang Meth-

odist hymns, to their great

entertainment. The Divine Spirit

was in the word and several were

awakened and saved. Among

the number were the daughters of the

home in which he was en-

tertained. He tarried for several days,

holding services at night

and forming a class.

In a few days he found himself in Upper

Sandusky, an en-

tire stranger, without an introduction

to any one. He called at

the home of William Walker, sub-Indian

agent, who thought him

a fugitive from Slavery, but Stewart in

a sincere, artless manner

gave his history, including his

Christian experience. Mr. Walker

was convinced, and gave him words of

encouragement, directing

him to the cabin of Jonathan Pointer.

Pointer was a black man who had been

stolen by the Wyan-

dots when he was a child. He could

converse fluently in both

the English and Wyandot languages. Here

was a providential

helper in opening an "effectual

door" to the Divinely appointed

missionary of the Methodist Episcopal

Church.

Pointer was not favorably impressed with

Stewart, and

tried to dissuade him from his

undertaking by telling him of

the efforts of the Roman Catholic

missionaries and their com-

plete failure. He did not know that

"the kingdom of heaven

cometh not by observation." Indeed,

Jonathan Pointer was as

much a heathen as the Wyandots, and was

at that time pre-

paring to participate in an Indian dance

and religious feast.

Stewart wanted to accompany him, and

Jonathan reluctantly con-

sented. Stewart as a visitor sat in

silence and witnessed the dance.

When an interval of rest occurred, he

asked the privilege of ad-

dressing them on the purpose of his

visit which, with their con-

sent, he did, Jonathan interpreting and

rather enjoying the no-

toriety it gave him.

Here was a scene worthy the brush of the

artist. The first

342

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

heathen audience of hundreds of Indian

warriors in war paint

and gaudy costumes listening to a

messenger of the Methodist

Episcopal Church; Jonathan, too, in

paint and feathers, while a

mild-mannered mulatto told them the

purpose of his visit. Here

was Christian courage equal to that of

Fr. Marquette or any of

the old Jesuit Fathers of the Roman

Catholic Church. In this

Stewart evinced extraordinary courage

and faith in the Heav-

enly Father.

At the conclusion of his address he

invited all to shake

hands with him, and on motion of Chief

Bloody Eyes, all passed

by in single file and did so. An

appointment was made at

Jonathan's cabin for the next evening,

and by the light of the

cabin fire Stewart preached his first

sermon. This was late in

November, 1816.

Stewart met the Wyandots daily, Jonathan

interpreting and

saying: "What Stewart says may be

true, he did not know,

he only translated fairly." Many

were greatly interested and a

few awakened. The efforts of Stewart to

secure the conversion

of his interpreter were unceasing, and

his reward soon came in

an open profession on the part of

Jonathan, who became a firm,

outspoken believer. The soil of his

jovial African heart was thin

and did not bring forth perfect and

matured fruit. He was

naturally vain and sometimes was given

to drink, but God used

him as one of "the foolish things

of this world to confound

the wise." He was demonstratively

pious in church.

The missionary met with opposition from

the whites who

sold "fire water" to the

Indians. They maligned him, persecuted

and tried to scare him away: They said,

"he was no minister,

a fraud, a villain," and some of

the leading chiefs became his

enemies. Dark days had come. The

muttering of a storm was

heard, but nothing daunted, Stewart

sang, prayed, and going

from cabin to cabin found those who

received him and his words

gladly. The agent, William Walker,

Jonathan and a few other

leaders were his friends. Indians

prejudiced by Catholic teach-

ing joined the opposition. His Bible,

they said, "is not the true

Bible," but these questions being

left to Mr. Walker, the de-

cision was favorable to John Stewart.

Walker said there was

little difference between the Catholic

and Protestant Bibles, one

|

John Stewart. 343

being a translation from the Latin, the other from the Greek and Hebrew, and both from the same original documents; and that any layman called of God had the divine right to preach and teach. Thus through this layman and Government officer, Stewart was helped in his work. The Wyandots were superstitious, believing in magic, witchcraft, religious dancing and feasting. These things Stew- art opposed with Scripture and reason, and gave any who desired the opportunity to defend them. John Hicks, a chief, under- took this. "These things," he said, "are part of the religion of |

|

|

|

our forefathers handed down from ancient times, and the Great Spirit was the author of them, the same being adapted to their needs." Mononcue, then a heathen, endorsed what Hicks said. He also said, "The Bible is the white man's book and Jesus the white man's teacher; they were sent first to white men, why not to the Indians?" Stewart said, "In the beginning Jesus commissioned his disciples saying, 'Go ye into all the world and preach the Gospel |

344 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

to every creature.' This is as much for

you as for any others;

we bring His Gospel to you and if you

receive it not you shall

be damned. The Bible is for all. Christ

died for all that all

might be saved."

Stewart continued and Mononcue, Hicks

and others were

convicted and converted. Many others

embraced the truth.

These were among his first converts.

Having never been Ro-

man Catholics, their prejudices were

easy to overcome.

Crowds came to Stewart's meetings

nightly, and the work

of revival increased. Many of the

younger converts became,

under the leadership of Stewart, good

singers. Stewart's solo

singing was a special attraction to the

unbelievers. He always

sang with the spirit and with the

understanding also. While

he was not demonstrative nor vociferous,

he had the gift of per-

suasion and could logically impress the

truth on other minds.

He was not a scholar, but he had a good

common school educa-

tion and upon this foundation, through

his intercourse with

books, nature and God he became an

efficient workman. Sev-

eral of his sermons found in print,

although not fully reported,

evince the fact that he had clear

conceptions of theology, es-

pecially as relates to man as a sinner,

and a sinner to be saved

by Grace.

In February, 1817, Stewart felt

that something more radi-

cal must be done in order to bring about

the conversion of those

who were under his instruction. Their

convictions were more

of the head than of the heart. He and

those with him prayed

daily for the outpouring of the Holy

Spirit, and their prayer

was granted. Revival power came upon these heathen, and

there was deep and pungent conviction

for sins and real con-

versions. This work of grace aroused

opposition.

The heathen party arranged for a

"Thanksgiving Feast

and Dance." It was for the whole

Wyandot nation, and so

Stewart and his followers attended.

Stewart went with mis-

givings; he simply sat and looked on. To

his surprise his con-

verts joined in the dance, Mononcue with

others. Stewart had

protested against this, and he went away

discouraged, resolving

to leave them. He announced his purpose

and preached his

farewell sermon on the next Sunday from

Acts 20:30. This

John Stewart. 345

sermon, reported and printed by William

Walker, the writer

has read. Earnestly Stewart plead with

the converts to avoid

heathen practices, and warned the

heathen present, kindly but

earnestly, to flee from the wrath to

come.

He narrated his call to come to them and

his labors with

them, and told them they should see his

face no more. There

was general weeping, even the heathen

joining in the lamentation.

Stewart then addressed the chiefs and

principal men, while

silence reigned among the large audience

assembled in the coun-

cil house, as he bade all good bye.

On the suggestion of Mrs. Warpole, a

collection was taken

for Stewart, amounting to ten dollars.

He left and returned to

Marietta. A few remained faithful.

Heathenism and drunk-

enness held full sway. Only twenty men

of the Wyandot nation

did not drink intoxicants. Although

Stewart was away his

heart was with the Indians and after

only a few months, to the

joy of the Christian Indians, he

returned. During his absence

he wrote an excellent pastoral letter to

the little flock. Through-

out, his spirit and conduct evinced the

unselfishness of his mo-

tives.

With his return came an increase of

zeal, and power and

increased success crowned his efforts.

The work enlarged. It

was more than Stewart was able to do. A

prominent Methodist

minister of another denomination than

the Episcopal Methodists,

visited him and tried to have him change

his relationship, but

it was of no avail. He sent an account

of "The Lord's doings"

among the Wyandots to a session of the

Ohio Annual Confer-

ence and asked for a helper who could

assist him in preaching

and administration.

As nearly as can be ascertained, the

names of the mission-

aries and time are: John Stewart, 1816

to 1823; James Mont-

gomery, 1819; Moses Henkle, 1820; J. B.

Finley, 1821 to 1827

-part of this time as presiding elder;

Charles Elliot, 1822;

Jacob Hooper, 1823; J. C. Brook,

1825; James Gilruth, 1826-27;

Russell Bigelow served as junior

missionary in 1827 and in

1828 was in charge of the mission and of

the district as presid-

ing elder with Thomas Thompson, junior

missionary; B. Boyd-

son, 1830; E. C. Gavitt, 1831; Thomas Simms,

1832; S. P.

346

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

Shaw, 1835; S. M. Allen, 1837;

James Wheeler, 1839-1843;

Ralph Wilcox, 1843.

The teachers in the mission were: Miss

Harriett Stubbs,

Miss Margaret Hooper, Liberty Prentis,

Miss E. A. Gibbs,

Asbury Sabin, Jane Parker, matron, and

teacher of spinning,

weaving and domestic work, Mrs. Jane

Riley, L. M. Pounds

and the missionaries' wives.

Up to this time Stewart was an exhorter,

his license being

signed by Father McCabe, grandfather of

Bishop Charles C.

McCabe. The licence was given while

Stewart was in Marietta.

He now attended a Quarterly Meeting on

Mad River Cir-

cuit. Bishop George was present and

presided. "After a care-

ful examination, John Stewart was

licensed as a local preacher."

With money raised by Bishop McKendree a

tract of fifty-

three acres of land on the east side of

the Sandusky, near Har-

men's Mill, was bought for Stewart.

About this time Bishop

McKendree, in feeble health, came to the

mission on horseback,

from Lancaster, Ohio, and was

accompanied by J. B. Finley and

D. J. Soul, Jr. The Bishop was delighted

to find "the Lord

had a people among the Wyandots."

The money paid for the land was

collected by Bishop Mc-

Kendree at camp meetings and

conferences. In this is not only

an official recognition but a memorial

of the large heartedness of

this pioneer Bishop.

About 1820 Stewart married Polly, a

mulatto girl. She

was a devout Christian, and could read

and write. With her

he lived in his own cabin home and with

the help of his wife

and friends soon had enough from the

virgin soil, with some

money assistance from the conference, to

live in pioneer com-

fort.

Near the end of 1823, after a battle

with consumption, the

word spread among the Christians that

Stewart was dying; a

number of Christian chiefs and devout

men and women were

with him. Christmas and the New Year

were at hand. Stew-

art calmly exhorted all-told how the

Lord sustained him, and

gave his testimony to the power of

Christ to save. Holding his

wife's hand, he said to all, "Oh,

be faithful," and died. In an

|

John Stewart. 347

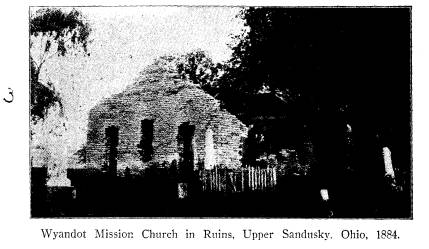

humble grave on his land he was buried, and for twenty years thereafter no stone marked his resting-place. But he was not forgotten. His grave was often visited, and the Indian youth were taught to place flowers on his grave each spring and summer time. In 1834 the Rev. James Wheeler, missionary, just before the Indians left for the West, had Stewart's remains taken up and reinterred at the southeast corner of the "old mission," and a free stone slab placed at his head with a suitable epitaph. This church was erected in 1824, the money, $1,333.33, be- |

|

|

|

ing donated by the Government through Hon. J. C. Calhoun, Secretary of War. Rev. J. B. Finley was the instigator in securing this, and he was made the custodian of the money pending its disposition in the erection of this church. The building later went into decay, and the gravestones were carried away piece-meal by relic hunters, until in 1886 all vestige of them was gone. A similar condition of affairs pertained with reference to the wood work and the furnishings of the Mission Church. In 1860 and 61 when these were in a fair state of preserva- tion, the writer, then a young man in his first station, Upper |

|

348 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

Sandusky, made a chart and diagram of the church and ceme- tery, the location of the buried dead, with copies of the epitaphs on each tombstone, which he preserved. The work of restora- tion was done with money-$2,000-donated by the Missionary Society of M. E. Church, by order of General Conference. The writer, as chairman of the restoration committee, had the honor of using this money in erecting once again, out of its ruins, the first mission church of Episcopal Methodism, and the first Prot- estant mission church in the Northwest Territory. When Charles Elliott was missionary, a log building was erected in |

|

|

|

which Stewart, Elliott and others preached, and here Harriett Stubbs taught the children. It was a temporary log building and, so far as we know, was not used exclusively as a church, and was not dedicated. During the session of the Central Ohio Annual Conference in September, 1889, the restored Mission Church was rededi- cated. There were several thousand more people present than could get into the house, so the services were held under the old oak trees which had sheltered the hundreds of Wyandots who had worship in the church. Dr. Adam C. Barnes, P. E., was chairman. Dr. P. P. |

|

John Stewart. 349

Pope, grandson of Russell Bigelow, led in prayer. Addresses were delivered by Bishop J. F. Hurst, Hon. D. D. Hare, Dr. L. A. Belt, Gen. W. H. Gibson, a historical address by the writer, and reminiscences by Dr. E. C. Gavitt, only surviving missionary, and a hymn in Wyandot sung by "Mother Solo- mon," a member in her childhood of the first mission school. Many were present whose parents or grandparents had been connected some way with the mission. |

|

|

|

Society of the Methodist Episcopal Church in 1819. And was not the mission school at Upper Sandusky the genesis of the Woman's Foreign Missionary work? If so, then all honor to Harriett Stubbs and Jane Parker and their worthy successors. Let the name of Stewart be placed in the list of the world's benefactors. May his sublime faith, clear conviction of the Di- vine presence, enthusiasm, endurance, patience and unselfish- ness, awaken in the hearts of each reader of these pages the spirit of emulation. |

|

JOHN STEWART PIONEER MISSIONARY OF THE METHODIST EPISCOPAL CHURCH.

N. B. C. LOVE, D.D. The Methodist Episcopal Church from its organization in 1773 was missionary in its spirit. It made continuous efforts |

|

|

|

dots, and the founder of the first Methodist Episcopal Mission among the heathen. Before the advent of Stewart the most cruel and bloody practices obtained among the Wyandots. In this respect they were not different from the other Indian tribes of the North- west. The burning of Col. Crawford, when a prisoner, is evi- dence of this. Even the women and children participated in torturing him. We need not repeat the story here. The Wyan- dots were the leaders in this savage deed. Between-the-Logs, it is claimed, was a participant, and such were the people to whom Stewart carried the gospel of love and peace The Wyandots for a long period stood politically at the head of an Indian Federation of tribes and so were recognized by the United States Government in the treaties made with the Indians of the old Northwest Territory. The names of chiefs of the Wyandot nation appear first prominently on the treaty made at Greenville in 1795 between Vol. XVII-22. (337) |

(614) 297-2300