Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

- 34

- 35

- 36

- 37

- 38

- 39

- 40

- 41

- 42

- 43

- 44

- 45

- 46

- 47

- 48

- 49

- 50

- 51

- 52

- 53

- 54

- 55

- 56

- 57

- 58

- 59

- 60

- 61

- 62

- 63

- 64

- 65

- 66

- 67

- 68

- 69

- 70

- 71

- 72

- 73

- 74

- 75

- 76

- 77

- 78

- 79

- 80

- 81

- 82

- 83

- 84

- 85

- 86

- 87

- 88

- 89

- 90

- 91

- 92

- 93

- 94

- 95

- 96

- 97

- 98

- 99

- 100

- 101

- 102

- 103

- 104

- 105

- 106

- 107

- 108

- 109

- 110

- 111

- 112

- 113

- 114

- 115

- 116

- 117

- 118

- 119

- 120

- 121

- 122

- 123

- 124

- 125

- 126

- 127

- 128

- 129

- 130

- 131

- 132

- 133

- 134

- 135

- 136

- 137

- 138

- 139

- 140

- 141

- 142

- 143

- 144

- 145

- 146

- 147

- 148

- 149

- 150

- 151

- 152

- 153

- 154

- 155

- 156

- 157

- 158

- 159

- 160

- 161

- 162

- 163

- 164

- 165

- 166

- 167

- 168

- 169

- 170

- 171

- 172

- 173

- 174

- 175

- 176

- 177

- 178

- 179

- 180

- 181

- 182

- 183

- 184

- 185

- 186

- 187

- 188

- 189

- 190

- 191

- 192

- 193

- 194

- 195

- 196

- 197

- 198

- 199

- 200

- 201

- 202

- 203

- 204

- 205

- 206

- 207

- 208

- 209

- 210

- 211

- 212

- 213

- 214

- 215

- 216

- 217

- 218

- 219

- 220

- 221

- 222

- 223

- 224

- 225

- 226

- 227

- 228

- 229

- 230

- 231

- 232

- 233

- 234

- 235

- 236

- 237

THE INDIAN IN OHIO

With a Map of the

Ohio Country

BY H. C. SHETRONE, ASSISTANT CURATOR,

Ohio State Archaeological and

Historical Society.

FOREWORD.

The accompanying narrative is offered in

response to an

apparent demand for a briefly

comprehensive account of the

aboriginal inhabitants of the territory

comprised within the State

of Ohio.

The need of such an addition to the

already extensive litera-

ture on the subject is suggested by

frequent inquiry on the part

of visitors to the Museum of the Ohio

State Archaeological and

Historical Society. This inquiry, representing all ages and

classes of visitors, but more

particularly pupils and teachers of

the public schools, may be fairly

summarized in a representative

query: "Where can I find 'a book'

that will give me the facts

about the Indian and the Mound Builder

?"

The difficulty of meeting this inquiry

would seem to indicate

that the wealth of research and

investigation along the line of

Ohio aboriginal history has not been

presented in a form fully

meeting the requirements of the average

reader. It is a simple

matter to meet the demands of the

special student, with time and

inclination for study; but apparently

the numerous productions

pertinent to the subject either are not

readily available to the

average reader, are not comprehensive of

all its phases, or in

some other way are unsuited to his

purpose.

While many important questions relative

to the Indian and

the so-called Mound Builder remain as

yet unanswered, the re-

sults of recent historic research and

archaeological exploration

make possible a fairly accurate sketch

of the aboriginal race in

Ohio, both before and since the advent

of white men. The pur-

pose, then, of this brief outline is to

supplement the Society's

(274)

The Indian in Ohio. 275

Publications and Museum exhibits, to the

end that visitors and

students may learn, insofar as known,

the more important facts

relevant to these "First

Ohioans", their activities, and the dis-

tinction and relationship between the

several great cultures of the

native American race which, successively

or contemporaneously,

made their homes on Ohio soil.

To accomplish this it has been deemed

necessary to unify,

under one cover, three aspects of the

subject usually presented

separately; namely, the American race as

a whole; the Indian in

Ohio (historic period) ; and the

prehistoric or archaeological

period in the same territory. Each of

these topics has been ex-

haustively presented by masters of thought

and expression; and

but for the desirability of combining

the three as component parts

of the story of the American aborigine

in Ohio, this compilation

would be highly presumptuous and without

justification. The

result is the more confidently

submitted, in that it follows closely

the writings of the acknowledged

authorities from which it is

compiled.

In the pages touching upon the American

aborigine in the

broader sense, the publications of the

Bureau of American Eth-

nology, the reports of the Bureau of

Indian Affairs, and the

works of a few of the standard authors

have been consulted.

The story of the Indian in Ohio, within

the historic period, has

been taken mainly from the masterly

presentation of Mr. E. O.

Randall in the "History of Ohio -

The Rise and Progress of an

American State," by Randall and

Ryan. Mr. Randall's treatment

of the Ohio Indian and his activities is

most exhaustive, and is

the last word in authenticity and

literary style, besides being the

most recent of the several standard

productions relating to the

subject. The brief summary of the

prehistoric period in Ohio is

based upon the researches and

investigations of Professor Wil-

liam C. Mills, Curator of the Ohio State

Archaeological and His-

torical Museum, and the acknowledged

"foremost exponent of

Mound Exploration in America". The

writer has had the honor

of being actively associated with

Professor Mills in field explora-

tions in Ohio during the past five

years, and through this has

been enabled to form first-hand

impressions of the prehistoric

period of Ohio occupancy.

276 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

In preparing the map of the Ohio

country, the sole aim has

been to serve the convenience of the

student of the period of

historic Indian occupancy. The Ohio

river and Lake Erie, with

their principal tributary streams, will

serve to acquaint the reader

with the physical geography of the

country, while these, together

with a few of the more important

aboriginal trails will indicate

the travel thoroughfares thereof.

Several modern cities have

been introduced to assist in determining

more easily the relative

locations of the Indian villages, and

the forts and battlefields of

the period.

In connection with the Indian towns it

has been thought

desirable, where not otherwise obvious,

to indicate the tribes to

which they pertained. The dates

accompanying these villages do

not purport to show the time of

settlement or origin, often un-

known, disputed or unimportant, but

rather that of first prominent

mention or of greatest historic

interest. The same reservation ap-

plies to the indicated territories of

the several tribes, which,

owing to constant change in their

boundaries and the fact that

they often overlapped one another cannot

be definitely outlined.

Sufficient of the territory adjacent to

Ohio proper is shown to

include occurrences inseparable from its

Indian history.

If this brief outline of Ohio Indian

history serves to supply

the average reader with desired

information and, through encour-

agement to those who may have

opportunity and inclination for

further study of the early history of

Ohio, tends to make "two

readers, where but one read

before", its object shall have been

attained.

THE NATIVE AMERICAN RACE

THE INDIAN AND THE PERIOD OF DISCOVERY.

In order properly to understand the

Indians and Mound

Builders who made their homes in what is

now Ohio, it is neces-

sary to consider briefly the native

American race as a whole, to

which these early inhabitants of our

state belonged. Just as it

would be impossible to write a complete

history of the present

inhabitants of Ohio, without referring

to persons and events in

other states, so it would be very

difficult to tell the story of these

"first Ohioans" entirely apart

from others of their race.

It is well known that when Columbus

discovered America

he entertained the mistaken idea that he

had touched upon the

shores of India, and that it was in this

belief that he named the

natives "Indians". Later, when

the New World was christened

America, the natives, for some reason,

continued to be known as

Indians. Within recent years numerous

attempts have been made

to adopt a more suitable name, but the

term Indian has become

so thoroughly incorporated into language

and literature that it

still prevails, and with the prefix

"American", is generally used

and recognized as designating in a broad

sense the native abo-

rigines of the Western hemisphere.

With the possible exception of the

Eskimo all the native

tribes of the Americas of both historic

and prehistoric times,

despite marked variation in culture and

physical type, are classed

as belonging to one great race --the

American, or Red race.

The Eskimo are classified by some scientists

as a distinct sub-

race, believed to be directly descended

from the Mongolians of

Asia; but most authorities now agree

that they really belong to

the American race and consider them

merely as a variant phys-

ical type, with decided Mongolian

traits, and as possibly suggest-

ing a connecting link between the

American and the Asiatic

peoples. In a certain sense the Indians

are, or were, the real

Americans; but the name American was

reserved for the com-

ing great nation of white settlers, who

were to explore, colonize

(277)

278 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

and develop the country; and the Indian,

in name as in more

material respects, was forced to make

way for the advance of

civilization.

It would be interesting indeed if we of

today could roll

back the years and view the native

inhabitants of the newly dis-

covered world as they appeared to

Columbus and others of his

time. In this age of the trained

explorer and ready press the

minutest details of a hitherto unknown

people would be quickly

made known, but at that remote period it

is not surprising to

find that often only the more apparent

facts were recorded. The

men who were so bold as to navigate

unknown and uncharted

seas, in sailing vessels which today

would be considered unsafe

even on our inland waters, and who

ventured for thousands of

miles from their native shores under

conditions which made

their return very uncertain, could not

be expected to pay much

attention to minor details. Their

purpose, indeed, was as im-

portant as their risk was great. The

demand of western Europe

for a new sea route to the Orient

usually is considered as the

prime incentive to Columbus' voyages of

discovery. The desire

to prove or disprove the sphericity of

the earth, a theory just

then attracting marked attention, and

the spirit of adventure,

with the prospect of discovering new and

strange lands where

treasure might be had for the taking,

were of themselves suffi-

cient incentive to lure the hardy

mariner into strange waters.

In the fact that the early explorer was

enabled to see and

observe the natives before contact with

Europeans had influenced

and changed their natural condition,

lies the greatest importance

of his records. The study of an

uncivilized people before con-

tact with other peoples has modified

their habits and customs is

very important, it their true history is

to be learned. After

such contact the change is often rapid,

and the legibility of the

story decreases in direct ratio as

opportunity for its study in-

creases. The early explorers were not

handicapped in this re-

spect, although their records, while

invaluable, are not always

as satisfactory as might be desired.

Often the very things we

most wish to know are left untold, while

again descriptions evi-

dently are fanciful and not infrequently

conflicting. The latter

is not to be wondered at, since the vast

extent of the newly dis-

The Indian in Ohio. 279

covered territory, with its extremes in

climate and other natural

conditions, meant corresponding extremes

of culture, or progress,

among the inhabitants; so that

explorers, touching at different

localities, would form different

impressions of the natives. De-

spite these imperfections, the several

records of early explora-

tion comprise quite an extensive

literature and furnish the basis

upon which all our knowledge of the

native inhabitants is

founded.

Touching first at the Bahama Islands and

later upon the

South American continent, Columbus had

his introduction to,

and received his first impression of the

natives. Then followed

the Cabots, Magellan, de Leon, Balboa,

Cortez, De Soto, Cartier,

and many others, all within the period

of discovery, and all

viewing the native inhabitants in their

primitive condition. Had

these men found everywhere the same

degree of culture, or de-

velopment, their stories in the main

would have been very much

alike, and much less time would have

been required in arriving

at a correct understanding of the native

race as a whole. But

in view of the diversity in climate,

topography and other condi-

tions having an important bearing upon

human welfare, it is

but natural that the inhabitants of the

several sections of so large

a country should have been unlike in

many respects.

As time passed and the new country

became better known,

opportunity was afforded for more

careful observation and com-

parison, with the result that many

discrepancies in the records

of discoverers and explorers were

reconciled. These records,

together with those of later and

present-day investigators, give

to the historic American Indian an

intelligible entity; while the

sum total of this knowledge,

supplemented by the work of the

archaeologist, has given us a fairly

clear insight into the life of

the race in prehistoric times.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS.

In the study of the human race, science

leaves no stone

unturned. Everything is considered that

holds a possibility of

throwing light upon the subject, past,

present or future. The

means employed are grouped under three

general heads; anthro-

pology, the science which deals with man

as a physical being,

280 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

that is, with the natural history of the

species; ethnology, which

treats of the activities of man, such as

language, art, industry,

religion, social and political

organization, manners and customs;

and archeology, which has to do with man

before history began

to record his story. The term

anthropology is used also in a

broader sense, as meaning the science of

man, and including

everything in any way pertaining to his

existence.

Anthropology, in this outline of the

American Indian, is

used purely in a physical sense.

Physical characteristics usually

are the first to attract attention in

the study of a people, and

probably are the most stable and

unchanging of the many items

pertaining to such an inquiry. By the

color of the skin and

hair, the cast of features and other

physical attributes, is deter-

mined the race to which a people

belongs. In the case of the

American Indian, science has found that,

with the exception

already noted, they pertain to one great

race, distinct from any

other.

The type is characterized by a swarthy

complexion, reddish-

brown to dark-brown in color; hair,

straight and black, with a

bluish luster; eyes brown; face medium

to broad, with high

cheek bones. In stature, the Indian

compares favorably with

the white inhabitant of today, although

the average varies among

different tribes and localities. The

term "red-skin" as popu-

larly applied to the Indian is

misleading, for while the com-

plexion is often highly colored from sun

and exposure due to

an outdoor mode of life, it is far from

being red in color, as that

term is generally used. Stories of

giants and pigmies among

the American natives likewise are

untrue, except that there have

been occasional very tall and very short

individuals, their occur-

rence, however, being no more frequent

than among other peo-

ples. Rather marked exceptions to this

rule are the Eskimos,

who as a people are much undersized, and

the Patagonians, of

the extreme southern extension of South

America, who are un-

usually tall. The head of the Indian is

a trifle smaller than that

of the white man, and the forehead is

often low and receding;

the hands and feet are not so large, but

the chest and back are

particularly strong and well developed,

indicating an active life

in the open. The male Indian naturally

has a sparse beard on

The Indian in Ohio. 281

the face which, however, seldom is

allowed to grow. On the

whole, the Indian as a race occupies a

position, anatomically,

between that of the white man and the

negro.

MENTALITY AND MORALITY.

In considering the mentality, or mind of

the Indian, we

should remember that "what the

father is the child will be."

The mind of the Indian child is moulded

by what he sees and

hears, and he grows up to be like those

around him. A child

of civilized parents placed in a similar

position would come to be

very like his foster-parents, and the

same is almost equally true

of an Indian child reared under the

influences and guidance of

a civilized home. The innate, or natural

mental capacity of the

Indian, therefore, may be said to be but

little inferior to that of

an individual of a civilized people. One

distinction, however,

should be kept in mind; namely, that on

the part of the unciv-

ilized individual the tendency to revert

to his former condition

is particularly strong, and a factor

always to be considered.

Many Indians who have attended the

higher institutions of learn-

ing, after having shown marked mental

capacity and achieve-

ment, have yielded to this strange

influence and have returned

to the life of their people.

In the matter of morals and morality the

Indian again is the

product of custom and association. What

is moral or immoral,

right or wrong, is largely a matter of

time and place, since stand-

ards vary so greatly among peoples. In

his native state the In-

dian knew and recognized many of the

cardinal virtues, such as

truth, honesty and the sanctity of human

life. Public opinion,

rather than law and the fear of

punishment was the motive

which compelled obedience to social

decree, although in many

tribes executive councils, having powers

of enforcement, were

recognized. In his own clan or tribe the

Indian respected the

rights of others and their property. It

was only against hostile

tribes with whom he might be at war that

depredations were

committed, as during such times pillage

and other forms of re-

prisal were considered proper. On the

whole there was much

to be commended in the character of the

Indian, and many in-

282 Ohio Arch. and Hist.

Society Publications.

stances are recorded where he displayed

generosity, faithfulness

and courage of a high order.

SOCIAL AND POLITICAL ORGANIZATION.

Aside from a few fundamentals common

alike to the great

number of culture planes represented

among the American

aborigines, it is impossible to present,

in a brief outline, a plan

of social and political organization

that will apply to all. Why

this should be so is readily apparent,

since we have seen that in

the course of their racial career the

Indians became separated

into numerous tribes and nations, each

developing its several

institutions in accordance with the

influence of environment and

other natural causes. In general, it may

be said that aboriginal

social and political organization,

always very closely associated,

were based upon kinship, or

consanguinity, rather than upon

territorial or geographical districts.

As perhaps the most representative of

the several units com-

posing the social and governmental

fabric, as well as the most

widely known, we may consider what is

designated as the tribe.

A tribe as constituted among the

American Indians is, or was,

a body of persons bound together by

blood ties or assumed re-

lationship resulting from the almost

universal custom of adop-

tion; by the possession of a common

language, and by certain

definite ideas as to social, political

and religious observances.

While kinship remained the basis of

tribal organization and

government, the tribe was more or less

fixed as to territorial

district and as to residence, thus

uniting the personal and the

geographical idea. The tribe, as such,

constituted an independent

state; but when united with other tribes

for mutual benefit, it

became part of a confederation. The

confederation was the

most highly developed unit of

organization, and whereas the

tribe corresponded to the state, the

confederation might be likened

to the nation.

Among the more primitive of the Indians,

the tribe was

loosely organized, its subdivisions

consisting of families and

bands; but in its higher development, it

was made up of divi-

sions known as clans or gentes. These

consisted of groups of

persons, actually or theoretically

related, organized to promote

The Indian in Ohio. 283

their social and political welfare.

Members of a clan or gens

often assumed a common class name, or a

totem, derived from

some animal or object, by which they

were distinguished from

members of another clan. Each tribe

might have a number of

clans, which in turn were organized into

phratries, or brother-

hoods. These phratries, usually but two

to a tribe, were really

social in their province, having to do

with ceremonial and re-

ligious assemblies, festivals, and so

forth. The members of a

phratry, or rather of the clans

composing it, considered them-

selves as brothers, while those of the

other phratry they addressed

as cousins.

The clan or gens was composed of the

family groups, the

first and simplest of the units of

organization. The family cor-

responded rudely to the household or

fireside, but varied greatly

in its significance among the different

tribes. Thus we have the

family, organized into clans or gentes;

these units united to form

phratries; the phratries combining to

form the tribe; and occa-

sionally, the tribe uniting with others

to form a confederacy.

But the tribal form of government

remains the prevailing type,

in which the most noticeable feature is

the sharp line drawn

between the social and civil functions,

and the military func-

tions. The former were lodged in a

tribal chief or chiefs, who

in turn were organized into a council

exercising legislative, judi-

cial and executive functions. These

civil chiefs were not per-

mitted to exercise authority in military

affairs, which usually

were left to captains, or war chiefs,

and to the grand council of

the tribe. These captains were men

chosen on account of their

fitness for the position and were

retained or dismissed according

to their success or failure in

prosecuting warfare.

RELIGION OF THE INDIAN.

The religion of the Indian, as with

other uncivilized peoples,

was based largely upon the supernatural,

or what appeared to

him as supernatural. What he could see

and understand, that

is, what could be explained by perfectly

obvious standards, he

accepted as natural; everything beyond

this was to him something

mysterious and a part of the spiritual.

With his limited knowl-

edge of the laws of nature and their

causes and effects, it is

284 Ohio Arch. and Hist.

Society Publications.

apparent that many of the phenomena

which he observed about

him would partake of the supernatural.

The essence of the Indian's religion was

what might be

termed magic power. This power he

believed to be vested in

various objects, animals, men, spirits

and deities, and to be able

either to injure or benefit him. It was

supposed to be some-

thing stronger than the same power or

powers within himself,

and to be capable of influencing, or

subject to influence by,

human activity. Thus his whole endeavor

was to the end that

he might gain and retain the good will

of those powers which

were friendly, and control those which

were inclined to be hos-

tile. Many methods of accomplishing this

were practiced by

the different tribes, among them being

charms, prayer, incanta-

tions, fasting, taboos, - the avoidance

of certain foods and acts

supposed to be displeasing to the

powers,--and offerings of

various kinds. The last named probably

never, or very seldom

at least, took the form of human

sacrifice, but consisted in offer-

ings of food, ornaments, weapons and

other minor objects.

The Indian believed himself possessed of

a spirit, or spirits,

which live in the hereafter; that the

world has always existed,

rather than that it was specially

created; and in some instances

the belief in magic power was carried so

far as to suggest in

an indefinite way the idea of deity.

Contrary to the general

belief, however, the Indian in his

natural state did not conceive

of a definite God, or Creator, but

rather of a mystic something

without definite form or attributes. By

the Algonquins this

power was called "Manito" -the

Gitche Manito of Longfellow's

Hiawatha - while the Iroquois expressed

the same idea by the

word Orenda. The Indian conception, as

expressed by these

terms, is often referred to by the

writers of fiction and Indian

tales as the Great Spirit.

The religious instinct in the Indian is

highly developed, and

his inclination toward religious

excitement is strong. As in

other creeds, there have been many

so-called prophets who from

time to time have introduced new

religious beliefs among them.

Among the foremost of these was

Tenskwatawa, the Shawnee

prophet, whose teachings stirred the

entire Indian population

east of the Mississippi just prior to

the War of 1812. Other

The Indian in Ohio. 285

noted prophets were Wovoka, originator

of the Ghost Dance

religion or Messiah craze, which swept

the Western states in

1888, resulting in serious Indian

disturbances; the Delaware

prophet of Pontiac's conspiracy, 1762;

and Smohalla, the

"dreamer of the Columbia."

Almost from the beginning European

settlers in America

were active in spreading among the

Indians their several religious

creeds, with the result that

Christianity was widely disseminated

among them. This work was carried on

mainly through the

establishment of missions, through which

were combined the

teaching of industry, morality and

religious belief. Many of the

heads of these missions were men of

force and character, who

dedicated their lives to the welfare of

the Indians and underwent

almost unbelievable deprivations and

hardships in carrying out

their undertakings. To these men we owe

much of our knowl-

edge of the early Indian tribes,

particularly as regards language,

customs and religion.

THE INDIAN LANGUAGES.

Under the head of ethnology, language

has been a very im-

portant factor in the study of the

American Indian. While con-

sidered from the physical viewpoint we

find that the natives

belong to a single great race, language

has shown that this race is

divided into a large number of

linguistic, or language, groups or

families. Language is one of the

scientist's most powerful aids

in the study of a people. By tracing the

history of words and

their meanings it is sometimes possible

to follow the migrations

and trace the origins and relationships

of peoples apparently

widely separated. In this way, within

the territory comprised

within the United States alone upward of

sixty different lin-

guistic families have been noted; that

is to say, the various tribes

are apportioned among that number of

distinct languages. In

turn the various languages, or stocks,

are divided into numerous

dialects, just as is true with other and

more highly developed

languages.

Of the fifty-six stock languages

recognized, a few are of

great extent and importance, while

others are comparatively

286 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

unimportant. Most of the latter are

confined to the Pacific coast,

at least twenty-five of them being

represented in the three states

of Washington, Oregon and California.

The most important of

the language groups was the great

Algonquin family, which em-

braced the New England and the East

coast, all of south-eastern

Canada and the country surrounding lakes

Superior, Huron and

Michigan, and extended southward into

the United States over

Michigan, Wisconsin, Iowa, Illinois,

Indiana, south-western Ohio,

and Kentucky. This great family

comprised most of the Indians

with whom the early Colonists came into

contact, and who figure

so largely in our early Indian

literature.

The second best known language family,

insofar as early

settlement is concerned, were the

Iroquois, whose principal terri-

tory encircled lakes Huron and Erie, and

extended on both sides

of the St. Lawrence river from these

lakes to its mouth. Most

of the territory within the states of

New York and Pennsylvania,

and a part of Ohio, was included in this

area, which in turn was

almost completely surrounded by the

great Algonquin territory.

West of the Mississippi river the

principal families were the

Sioux, the Athapascans and the

Shoshones. Of these the Sioux

were particularly prominent, figuring

conspicuously in the Indian

troubles which attended the opening of

the great western country.

The remaining families ranged in

importance from a few mem-

bers or a single tribe, to the extensive

Mushogean family, com-

prising the Creeks, Choctaws, Chickasaws

and Seminoles of the

south-eastern states; and the Caddoan

family, farther west,

whose chief tribes were the Caddos,

Pawnees and Wichitas.

One unacquainted with the character of

language, as used

by uncivilized peoples, might very

naturally have some curiosity

to know something of the language of the

American Indian. It

would be correctly surmised that the

language of a barbarian

people would not be so highly developed

as that of a civilized

community. In fact, language is a

growth, having its inception

at the time when man begins to realize

the need of a means of

expressing thought, and its development

is exactly in proportion

to the development of mentality. This

growth and development

of language is progressing today just as

it has done through all

time. When a new discovery or invention

is made, a new word

The Indian in Ohio. 287

usually is created or "coined"

to name or describe it. No known

people is so low in intelligence as to

be devoid of some sort of

language, yet in the case of many

savages the means of orally

expressing thought are very limited and

crude.

While in many respects the languages

used by the American

Indians are distinct and different one

from another, there are

certain traits which are common to

practically all of them. For

example, in most cases where in English

we use separate words

to convey different shades and

modifications of meaning, the same

thing, in the Indian languages, is

effected by what grammarians

term "grammatical processes";

that is, by changes in the stem

words or by adding or subtracting

prefixes and suffixes and by

certain gestures and movements

supplementing the spoken words.

In this way such forms of speech as

prepositions, adverbs and

conjunctions often are almost entirely

ignored. Many sounds

unfamiliar to English-speaking persons

are met with, and a

number of the languages, particularly

those of the north-west, are

considered as harsh and unpleasing to

the ear. Those of the

central and eastern families, however,

are more euphonic. So it

is readily seen that to the student of

modern English grammar

the construction and use of the native

American languages would

appear strange and difficult indeed.

Naturally the mental process of the

Indian is not so delicate

and discriminating as that of highly civilized

man, and therefore

his ideas are more likely to be concrete

than highly abstract in

form. His language, while possessing a

good grammatical basis

and fairly extensive vocabularies, is

better adapted to descriptive

expression than to generalized

statements. After a manner the

Indian is a fluent speaker, and the race

has produced a number of

eloquent and forceful orators, not alone

in the present generation

but among those of earlier times.

ARTS AND INDUSTRIES.

The degree of advancement to which a

people has attained

is reflected very clearly in their arts

and industries, and these,

coming under the head of ethnology,

claim an important place in

the study of the American Indian. By

arts and industries is

288 Ohio Arch. and Hist.

Society Publications.

meant the manner in which natural

products of the earth were

utilized in the service of man.

In his most primitive state, man depends

for subsistence al-

most entirely on what he can reach out

and take from nature's

bounty, such as fruits, nuts, roots,

plants and game. In this stage

of development--the lowest grade of

savagery--an equable

climate is essential to human existence;

hence very little in the

way of shelter or clothing is required.

Natural caves or crevices

in the rocks, or at best rudely

constructed artificial shelters, suffice

for protection and warmth. A

supply of water, of course,

is pre-supposed, and usually is readily

accessible. Thus savage

man finds ready prepared for him in

nature and her spontaneous

products the requisites for satisfying

the three necessary require-

ments of human life - food, water and

shelter.

The growth and development of the human

race has been

likened to the changes through which the

individual passes in

his progress from infancy to adult life.

The savage state cor-

responds to the infant, the barbarian

stage to youth, and civiliza-

tion to adult life. In the first of

these human intelligence is little

more than instinct and, as in the case

of the infant, serves merely

to prompt the individual to reach out

and take whatever appeals

to his needs. Beginning with practically

nothing in the way of

artificial aids to living, the savage

gradually takes advantage of

natural objects suggesting aid or

usefulness. One of his first dis-

coveries is that a stone, of proper size

and shape to be grasped in

the hand, is useful for pounding; and

thus originated the stone

hammer, which has been characterized as

the father of all civiliza-

tions. From its first use can be traced

directly the development

of all tools arid machinery, and through

these the evolution of the

human race to its present high estate.

Quite early in his development the

savage learns to modify

the shape and size of his stone hammer,

and even to mount it in

a handle; for in striking one stone

against another he observes

the principles of cleavage and breakage,

which in turn lead to

the art of chipping or flaking stone.

This, the most important of

the early accomplishments of man,

furnishes him with edged im-

plements for cutting and pointed

instruments for perforating.

The Indian in Ohio. 289

A hollow stone, a shell or a gourd would

first serve him as a

container for water or food and would

lead to the modification ot

natural objects to more suitable forms.

The flexibility of a stick

or twig would suggest to him a latent

power which, after a time.

would evolve into the bow and arrow.

Through friction and per-

cussion he learns to produce fire,

although in this art, as in the

chipping of stone and flint, it would

seem that special instinct

came to his aid, so generally and early

were they known to savage

man.

Within the United States proper it is

not known whether the

lowest stage of human development was

represented, as all the

tribes at the time of discovery or of

first observation were at least

in the upper stages of savagery. The

least advanced of these

probably were some of the tribes of the

territory within our

north-western states.

The second stage of development, or

barbarism, is char-

acterized by an advanced use of

artificial aids to existence and

by a well defined social status; that

is, definite ideas as to social

organization, religion, morality and so

forth. This state, as

before mentioned, corresponds to the

period of youth in the indi-

vidual. A more or less sedentary or

settled life, occupational de-

velopment, and a certain amount of

agriculture render man of the

barbaric stage much less dependent upon

chance for a livelihood.

The simple lessons learned in the savage

state are elaborated and,

through the use of his natural ingenuity

and awakening mentality,

he improves upon old methods of

utilizing the resources at his

command. The rudely chipped implements

and utensils of stone

give place to those of more careful

finish and form; the shell and

gourd as containers are replaced by

vessels of potteryware;

natural shelters are modified to suit

his convenience or are alto-

gether replaced by specially erected

dwellings; he learns the art

of weaving fabric for clothing and

blankets and the making of

baskets for use as containers; and art,

in its finer sense - deco-

rative, ornamental and

pictorial--assumes a more important

place in his life. He has added to the

list of natural substances

and materials available for his use and

now employs metals in

the arts, at first, however, treating

these merely as malleable

stone, which he pounds or cold-forges

into shape. When he dis-

Vol XXVII-19

290 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

covers the art of smelting the metals

and of casting them into

form, he will be well on the way toward

the beginnings of the

civilized stage of development.

PLACE IN CIVILIZATION.

Within the United States proper the

natives were still in the

Stone Age period of culture, but in

Mexico, Central America and

Peru, certain tribes had discovered the

art of smelting and cast-

ing, and through the use of copper and

alloys produced a sort of

bronze, thus passing into the beginning

of the Metal Age.

Though the new discovery had not

attained to any great degree

of usefulness it was significant of the

general advancement of

these peoples, who, it has been

remarked, were in many respects

almost as enlightened as were their

discoverers.

Among the tribes of the territory within

the United States,

the Mound Builders of the Ohio and

Mississippi valleys and the

Pueblo or cliff-dwelling Indians of the

south-western states, had

attained to the greatest degree of

advancement. The mound

building Indians erected great

earthworks of complex and geo-

metric design as adjuncts to their

religious observances, as

fortifications for defense and as sites

for dwellings and villages.

Huge mounds of earth, from which these

people take the name

Mound Builders, were erected as

monuments over the resting

places of their dead. They erected

structures of timber and were

skilled in the arts, such as the weaving

of cloth, the making of

potteryware, the working of copper and

mica, and particularly

in the carving of stone and other hard

substances into artistic

forms. The Pueblo Indians, who in great

part occupied the well-

known Cliff-Dwellings of Arizona and New

Mexico, were skillful

artisans and had developed agriculture

to the point where they

constructed great irrigation canals to

convey water to their grow-

ing crops. Intermediate between these

highly developed tribes

were the Plains Indians, who in the

absence of timber or stone

for the construction of dwellings lived

in tents or wigwams of

skins and mats; and the village Indians

of the country farther

east.

Thus it is seen that the native

inhabitants of the New World

were greatly diversified as to culture

and that while it is possible

The Indian in Ohio. 291

to assign a place in the cultural scale

to a given tribe or com-

munity, it is difficult to do so when

speaking of the country as a

whole. Man is a creature of environment;

that is to say, climate

and conditions surrounding him play an

important part in his

development and determine to a great

extent his status at a given

time. This accounts in part for the fact

that certain tribes ex-

hibited an advanced stage of culture

while others were very

primitive, the extremes ranging from

savagery to the upper

grades of barbarism.

THEORIES AS TO ORIGIN.

The origin and antiquity of the native

American race are

questions which have engaged the study

of many minds since

first the subject came to the attention

of thinkers and writers.

A sufficient number of books to fill a

library have been written

on these subjects, and yet the problems

await definite solution.

As to origin, the simplest suggestion

offered is that the natives

were indigenous to the country; that is,

that they originated

here, just as did the buffalo and other

animals peculiar to

America. Adherents of this theory point

out that since the

Indian had to originate somewhere it is

just as probable that the

race had its birth on this continent as

elsewhere; that other con-

tinents had their indigenous peoples,

animals and plants, and

that America is no exception.

Others, however, attribute the origin of

the American ab-

origines to a foreign source, believing

that evidences of the con-

trary are lacking. Almost every country

and people on earth

has been suggested as the source of this

origin. Among these,

the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel were a

favorite with very early

writers; others have professed to trace

this origin to the ancient

Egyptians, the Chinese, Japanese and

other Mongolian peoples,

and so on, not to mention most peoples

of the white race, and

even the negro. It is true, as

previously stated, that the Indian

possesses physical characteristics of

both the white man and the

negro. Likewise there are certain things

suggesting relationship

with the Mongolian or yellow race, and

this theory of origin has

many ardent supporters.

292 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

Just how the Mongolian tribes reached

America is a point

in dispute, even among those who

consider that race as the

origin of the American natives.

Originally it was pretty gener-

ally believed that they crossed over

Behring Straits, either in

boats or on the ice, as has been done

frequently within historic

times. The close proximity of

northeastern Asia and northwest-

ern America, with the narrow straits

intervening, would make

passage easy. Yet it is pointed out by

some writers that a peo-

ple native to a cold climate never

migrate southward, and seldom

migrate at all, as the natural increase

in population is not suf-

ficient to stimulate migration. These

same thinkers prefer to

trace the Mongolians across the Pacific

ocean and to place their

landing somewhere in northwestern South

America. From this

point they believe that migration

extended in all directions until

both continents were populated. The

development and distribu-

tion of maize or Indian corn, which is

traced back to a tropical

seed-bearing grass, and various

ethnological considerations, speak

strongly in favor of this theory.

Whichever may be correct, it

is pretty generally conceded that if

America received her first

inhabitants from Asia they landed

somewhere upon the western

coast of the continent, and from thence

gradually extended into

the interior and eastward.

Regardless of the question as to the

place of landing of the

first arrivals on American soil, let us consider

as at least plausible

and worthy of entertainment the theory

of the Asiastic origin

of the American aborigines, mainly for

the purpose of illustrating

the migrations and development of a

primitive people. Sup-

posing, then, the newly arrived adventurers

safely implanted

upon the western coast of the continent,

anywhere from Alaska

to central South America, ready to take

advantage of every

favorable condition and to meet every

obstacle which imposed

itself in the new and strange land. The

greater part of this

coast line would afford a congenial

climate and conditions

favorable to human existence, while the

ocean itself offered a

never-failing larder. Here the wanderers

gradually would in-

crease in strength and numbers and after

a time, as is natural

to the human family, the instinct to

branch off and seek new

homes would assert itself. This

migratory instinct in the human

The Indian in Ohio. 293

race is very marked and is represented

today in almost all parts

of the world, a good example being the

recent steady stream of

immigration into the United States from

Europe and Asia. But

in the case of the people under

consideration there were the

great mountain ranges running parallel

with the Pacific coast,

almost the entire length of the

continents, barring their way to

the eastward. We can imagine them

contemplating the passage

of these obstructions, perhaps for

centuries, meanwhile pushing

to the north or south where no obstacle

intervened. It will

be remembered that the comparatively low

Alleghenies held back

the colonists - a

civilized people -for a hundred years before

they finally passed over and into our

own state of Ohio. But

once accross the mountains the Indians,

as we shall now call

them, paused to take their bearings,

drew a long breath of in-

spiration and took up their march into

the unknown country.

This surmise of what may have happened

affords an illustra-

tion of the evolution of different

cultures from a common

beginning. We can readily picture this

great prehistoric "cross-

ing the divide", and imagine the

difference of opinion which

doubtless existed as to which of several

directions offered the

best advantages to the aboriginal

adventurers. With particular

attention to the country within the

United States, let us follow

one band which decided let us say, upon

a course that ultimately

brought it into that great square of

territory comprised within

the states of Utah, Colorado, Arizona

and New Mexico. Al-

though the climate of this section is

very mild, shelter of some

sort is always grateful to man, both as

a refuge from inclement

weather and for purposes of protection.

There being but little

timber at hand for the construction of

houses, they took advan-

tage of the natural openings in the

cliffs and became what later

were known as the Cliff Dwellers, or

Pueblo Indians - in time a

distinct culture group. A second band of

adventurers, pushing

farther eastward, arrived on the Great

Plains. There, finding

neither wood nor stone with which to

build, they became dwellers

in tents or wigwams of skins and mats

-our Plains Indians. A

third band, journeying still further

eastward and arriving in

the rich and fertile valleys of the

Mississippi and Ohio rivers,

met still another kind of environment,

which was destined to pro-

294 Ohio

Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

duce yet another distinct culture-the

Mound Builders, or

Mound-building Indians.

QUESTION OF ANTIQUITY.

The length of time which has elapsed

since man first made

his appearance in America, like the

question as to his origin, is

uncertain. Speaking in general terms,

however, his advent is

comparatively recent, when we take into

consideration the record

of human life in other parts of the

globe. In England, Belgium,

France, Germany and other old-world

countries, scientists have

demonstrated the existence of human life

for more than half

a million years. In Java the bones of a

very primitive type of

man have been fouund, which make it

probable that the human

race has been in existence nearly double

that length of

time. In many sections of France and

adjacent countries, the

anthropologist has been able to lay bare

a complete record of

occupancy of the same site by several

different and successive

cultures. These evidences show, almost

as clearly as though

written in a book, the progress of the

human race from the

crudest stages of development up to the

present time. In France

early man made use of the many large

caves and caverns which

occur in the rocky terraces bordering

the rivers. On the floors

of some of these caves are found many

feet of soil, the result

of countless years of accumulating

refuse from the peoples who

used them as places of shelter and

refuge. Beginning at the

bottom of this artificial floor will be

found a stratum representing

its earliest inhabitants, and containing

their rude stone and bone

implements and other objects. Next above this deposit will

occur another layer, corresponding to

the inhabitants who came

second in its use. The record is

continued in this way until

perhaps half a dozen distinct

habitations are disclosed, each

showing some advancement and improvement

over the preceding

ones. By taking into consideration the

geological changes which

have occurred since the deposits were

made, something ap-

proximating the time elapsed can be

reckoned and the age of the

habitations thereby estimated.

In America no such marked series or

successions of cultures

is found, which would seem to indicate

that human occupation

The Indian in Ohio. 295

of the western hemisphere began much

more recently than in the

Old World. The apparent absence of these

evidences of very

early and prolonged occupation, and of

skeletal remains of other

than the more modern type of man, is the

strongest argument

of those who believe that America

received her inhabitants

at a comparatively recent time from

another part of the world.

On the other hand, there are those who

contend that the

course of human existence in the Old and

the New worlds has

been very nearly the same. These men

point to the fact that the

American natives have developed an

absolutely distinct physical

type, characterizing them as a race

apart from all others; that

they have developed numerous distinct

languages and dialects

thereof and that important changes and

modifications in

geological conditions and animal life

have taken place, all of

which would require a very considerable

period of time for their

accomplishment. At the very least, these

facts considered, the

sojourn of the native peoples of America

must have covered

several thousands of years, but just how

long, even in

approximate terms, remains to be

answered.

REMOVAL OF THE INDIAN.

The story of the struggle of the Indian

against the en-

croachment of the white man, covering a

period of more than

three centuries and ultimately ending in

his complete subjugation,

is too complex for more than casual

reference. Taken as a whole,

it affords the student and reader one of

the most tragic and

stirring romances ever written. From the

moment of landing

of the Virginia colonists and the

Pilgrim Fathers the crowding

back of the Indian and the appropriating

of his lands have been

in progress. Beginning with the first

friction between the Col-

onists and the Red Men, the struggle

soon resolved itself into

open hostilities. At first efforts were

made to preserve friendly

relations with the Indians, particularly

on the part of English

settlers, as at Jamestown and in the New

England colonies.

The friendship between Powhatan and

Captain John Smith,

the treaty between Massasoit and the

Plymouth colonists, and the

justice of Roger Williams are bright

spots in the early history of

the Colonies. But these peaceful years

were only the calm before

296 Ohio Arch. and Hist.

Society Publications.

the storm that was to follow, as shown

by Indian uprisings in

Virginia and King Philip's War in New

England. From this

time on, through the French and Indian

war and the war of the

Revolution, the Indian figured largely

in Colonial affairs.

After the close of the Revolution,

however, one of the first

acts of the new United States was the

effecting of a treaty with

the Delawares and the Iroquois, which

practically ended Indian

hostilities in the Colonial states. The

theatre of the struggle

then moved westward into Ohio and the

Northwest territory.

These treaties, and the Indian policy

adopted under President

Jefferson's administration, practically

established a permanent

basis for dealing with the Indians and

laid the foundation for

our present Indian policy.

In the more southerly of the states,

however, the Indian

troubles were not so early settled.

During the War of 1812

the Indians of Georgia and adjacent

states, particularly the

Creeks, began depredations which ended

only when General

Jackson, leading the volunteer troops of

those states, practically

decimated their army of fighting men.

Although President

Monroe, in 1825, through Congress

provided for the removal

of all Indians to lands beyond the

Mississippi, it was not until

some years later that this was

effected. The Creeks and

Cherokees were successfully removed but

the Seminoles, under

Osceola, taking up their stand in the

wilderness of Florida,

offered desperate resistance and it was

only after a long and

costly warfare that, in 1842, they were

conquered. The year

1842 likewise witnessed the removal of

the last of the Ohio

tribes. The Winnebagos, Sacs and Foxes

of Illinois and adjacent

states, alter a spirited struggle, had

been removed in 1832 Thus

the country east of the Mississippi was

practically cleared of

hostile Indians before the middle of the

last century, leaving

this great expanse of former Indian

territory entirely in the

hands of white men.

A few tribes and bands, particularly

those which evinced

a tendency toward peaceful pursuits,

were never removed to

the western reservations. The principal

ones of these are the

Five Nations of Iroquois, in the state

of New York; 7,500 Chip-

pewas in Michigan; an equal number of

Cherokees in North

The Indian in Ohio. 297

Carolina with a scattering of the same

tribes in Georgia, Ten-

nessee and Louisiana; a few hundreds of

the New England In-

dians in Maine and Massachusetts, and

about 600 Seminoles

in Florida. With the exception of the

latter, who constitute

a remnant of the rebellious Seminoles

who successfully resisted

removal, the Indians mentioned are

civilized, living much as do

their white neighbors.

One of the most spectacular of all the

wars with the

Indians, and the last really great

struggle, was that of the year

which marked a centennial of American

Independence - 1876.

In June of that year, a detachment of

regular army troops

under General Custer engaged the

rebellious Sioux on the

little Bighorn river, in Montana. This

famous campaign, in

which Custer and every man in his

command were killed by

the followers of Sitting Bull and Crazy

Horse, is familiar to all.

It was made necessary by the unrest and

excitement created

among the Indians by the introduction

among them of the

spectacular Ghost Dance religion, or

Messiah Craze, previously

referred to. The campaign against the

Sioux was vigorously

pushed and within a year they were

completely subdued.

POPULATION, PAST AND PRESENT.

An estimate of the Indian population

within the United

States proper at the time of discovery,

doubtless will be a sur-

prise to many. The great size of the

territory and the popular

conception of Indian life would lead the

uninformed to place

the early population far too high. It

must not be forgotten

that a given area which under civilized

conditions will support,

let us say, a million inhabitants would,

under barbaric or savage

tenancy, supply the needs of perhaps not

more than one-tenth

that number. While opinion is divided it

seems probable that

the population at the time of discovery

did not exceed one mil-

lion, and more than likely was less than

this number. The

present Indian population according to

the report of the Com-

mission of Indian Affairs for the year

1915, is slightly more

than 330,000. This marked decrease from

the estimated num-

ber of inhabitants at the time of

discovery is due mostly to

298 Ohio Arch. and Hist.

Society Publications.

adverse influences attending the marked

change in the life of

the Indians since the coming of white

men.

Disease, intoxicating liquors, hardships

resulting from en-

forced removals from one location to

another, warfare, and to

some extent, the conditions attending

upon reservation life are

the main factors in the decrease. The

hardships and persecu-

tions to which the Indians were

subjected during the first three

centuries following discovery resulted

in the complete annihila-

tion of some tribes and the

demoralization of many others.

Within recent years, under the more

humane government sys-

tem of caring for the Indians their

numbers, in some instances

at least, have increased. The greater

part of this increase, how-

ever, is of mixed blood, the result of

intermarriage of Indians

with whites and negroes. The Navahos

appear to be the only

pure-blood tribe of importance to

augment its numbers within

recent years.

THE INDIAN AND THE RESERVATION.

With the exception of some scattering

bands which still

roam at large over the public domain of

the far west, and of

those, already mentioned, who remained

in the east and south,

the Indians now reside mostly upon

reservations, set apart by

the government for their use. There are

about 160 of these

reservations, located mostly west of the

Mississippi river, and

comprising some 52,000,000 acres of

land. To a great extent

the Indians have abandoned their tribal

organizations and in

many instances have been accorded the

status of citizenship,

either in full, or restricted, as their

qualifications have seemed

to warrant. According to latest

available figures, -some 166,000

Indians now enjoy citizenship, although

a considerable percent-

age of these are in the restricted

classes. The policy of the

government is to prepare the Indians for

citizenship as rapidly

as possible and to confer the same

whenever such procedure is

justifiable. The laws provide that

Indians who sever their tribal

relations and adopt the habits and

customs of civilized life,

those who select allotments, and receive

patents-in-fee, thereby

become citizens of the United States;

those who fail to meet

these requirements remain as wards of

the general government

and are confined to the reservations

under certain restrictions.

The Indian in Ohio. 299

Of the total number of Indians within

the United States,

almost one-third are comprised within

what are known as the

Five Civilized tribes, of Oklahoma.

Those five tribes, number-

ing slightly more than 100,000, consist

of the Creeks, Cherokees,

Seminoles, Choctaws and Chickasaws, who

were removed to

their present reservations early in the

past century from their

former locations in the south-eastern

states. They are mainly

farmers, stock-raisers, artisans and

laborers, and live very much

the same as white people, patricularly

those of rural com-

munities. They have churches and

schools, participate actively

in their own government, and enjoy many

social advantages

In the present war with Germany, these

Indians have made an

excellent showing, not alone in the

matter of financial contribu-

tions to war bonds and other expedients,

but in the number

of men which they have furnished as

volunteers in the military

service.

The distribution of the remaining Indian

tribes, by states,

shows Arizona with approximately 41,000,

consisting of Apache,

Mohave, Navaho, Pima and Hopi, New

Mexico with 21,000,

mainly Pueblo and Apache; South Dakota,

20,000 Sioux;

California, 16,000, composed of numerous

small tribes and

bands; Wisconsin 10,000, Chippewas;

North Dakota, 8,000,

Sioux, Mandan and Chippewa; Michigan,

7,500, Chippewa;

Idaho, Kansas, Nebraska, Nevada, Oregon,

Utah and Wyoming,

from 2,000 to 8,000 each; and those in

the more eastern states,

already mentioned.

OFFICE OF INDIAN AFFAIRS.

In order to administer supervision over

its wards among

the Indians, the government maintains an

important and highly

organized bureau, known as the Office of

Indian Affairs, operat-

ing under the Department of the

Interior. The head of this

bureau is known as the Commissioner of

Indian Affairs, and

associated with him are a corps of

trained assistants and work-

ers, whose time and energy are given to

the interest of the In-

dians. The bureau proper is composed of

several distinct divi-

sions, the more important of which are

the Land Division, the

Finance Division, the Accounts Division

and the Education Divi-

300 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications.

sion, the last named being headed by a

Superintendent of Indian

Schools.

Aside from regular reservation schools,

several special train-

ing and vocational schools have been

established by the govern-

ment for Indian students. Among these

are the great Carlisle

school at Carlisle, Pennsylvania, and

the Chilocco Industrial

school, at Chilocco, Oklahoma. These

schools, each with up-

ward of 1,000 students, aim to afford a

"practical, productive

education" to their pupils. They

aim to further preparation for

citizenship among the body of Indians,

and in the individual

to pave the way for educational

advantages of the higher in-

stitutions of learning. A number of

their students, of both

sexes, have availed themselves of the

opportunities offered,

often with gratifying results. The

natural ability of the Indian,

as exemplified in such men as Sitting

Bull, Brant, Tecumseh, Red

Cloud and a score of others of the

earlier period, is reflected in

the success of present-day Indians under

modern educational

advantages. As examples of the latter

there may be cited, Dr.

Charles A. Eastman, physician and

author; Hon. Gabe A. Parker,

registrar of the United States treasury;

Henry Roe Cloud, edu-

cator; Arthur C. Parker, archaeologist

for the State of New

York; Charles D. Carter and Robert L.

Owen, United States con-

gressman and senator, respectively; Mrs.

M. L. Baldwin, lawyer;

Dr. Sherman Coolidge, D. D., and many

others. For physical

excellence, we have as examples James

Thorpe, world-famous

Olympian athlete; Tom Longboat and Lewis

Tewanima, the lat-

ter probably America's greatest

long-distance runner; and the

well-known football players of Carlisle

Indian school.

FUTURE OF THE INDIAN.

Despite these encouraging examples, the

Indian labors under

many handicaps and his future welfare

seems by no means

secure. Health and disease are matters

of grave concern at

the present time, particularly in view

of the inroads made by

tuberculosis, trachoma- a disease which

attacks the eyes and

often results in blindness - and some

others. The pulmonary

diseases are due in part to the change

in manner of living, par-

ticularly as regards housing. It is

difficult to impress upon the

|

The Indian in Ohio. 301

Indian the principles and importance of ventilation and sanita- tion, the result being that the abandonment of his former life in the open and the substituting of modern houses with artificial heat for the accustomed tent or tepee, has worked too sudden a change. Intemperance, especially in the use of alcoholic drinks, has been another source of detriment. Like other uncivilized peoples the Indian has been more ready to assimilate the vices |

|

|

|

of the white man than to accept his virtues, with the inevitable result. The Indian and his friends among the whites find many objections to the government reservation system, in which they see insurmountable barriers to the desired improvement in the native race. There seems to be no doubt that many drawbacks exist, as claimed, which in the past at least, often have amounted to abuse; but those best acquainted with the Indian problem |

302 Ohio Arch. and Hist.

Society Publications.

and its solution seem so far to have

been unable to reconcile

the differences between the Indian

department and its wards.

The encouraging aspect of the situation

is an awakened

interest in the welfare of the Indian,

fostered not alone by the

government but by private individuals

and societies, both of his

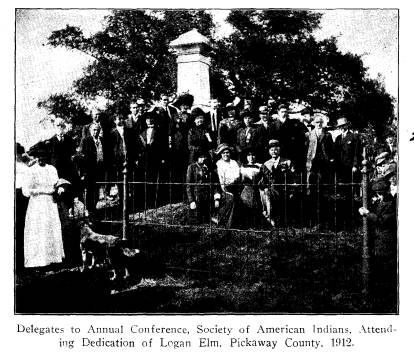

own race and of whites. Several

organizations exist for the

purpose of carrying on the work, among

which are the Indian

Rights association, the Indian

Industries league, the National

Indian association and the Society of

American Indians. The

latter is composed entirely of members

of the Indian race, and

comprises among its associates the

leading Indian men and

women of the country. It is worthy of

note that Ohio, which

of all the individual states has given

most attention to the pre-

historic inhabitants of its territory,

through scientific exploration

and the upbuilding of a great

archaeological museum, furnished

the impetus for the organization of the

Society of American

Indians. In 191, Professor A. W.

McKenzie, for many years

an ardent friend of the American Indian,

brought about a con-

ference of the leading men and women of

the race. This con-

ference, held in Columbus, resulted in

the formation of the

Society, the efforts of which promise to

be the most potent

factor in the future welfare of the

Indian. The organization

"seeks to promote the highest

interests of the race through

every legitimate channel," basing

its appeal on the latent power

of the Indian to do for himself rather

than to depend upon

others. The Society maintains a

Washington office, lends its

surveillance to national legislation

affecting the race, holds an

annual conference of country-wide interest,

and publishes as its

official organ the American Indian

Magazine, which is managed

and edited entirely by Indians.

In view of this earnest activity, there

is hope that the native

American race may yet emerge from the

unhappy state which

has been its lot for four hundred years,

and through its own

efforts and those of its friends among

the whites, eventually

succeed in reviving from the ashes of

misfortune a flame of

progress, which will burn all the

brighter for having been so

nearly quenched.

304 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society

Publications.

wholly in the past while others still

obtain; as a rule, however,

it is considered advisable to treat the

native race as of the past,

except where the use of the present

tense obviously is required.

In this, and in minor particulars, which

need not be specified,

the reader's indulgence is asked.

The story of the Indian in Ohio falls

naturally into two

distinct periods with respect to time -the

Historic and the Pre-

historic. The two will be considered in

the order named, in

the belief that an understanding of the

latter will be facilitated

by using the more definite knowledge of

the Historic period as