Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

- 34

- 35

- 36

- 37

- 38

- 39

SUMNER -- BROOKS -- BURLINGAME

--or--

THE LAST OF THE GREAT CHALLENGES

BY JAMES E. CAMPBELL

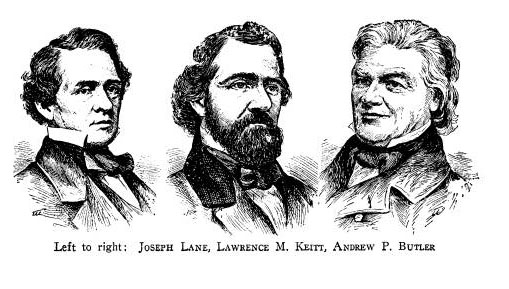

The purpose of this paper is to throw

light upon one

of the most famous of the many

thrilling episodes which

preceded the Civil War -- thereby

reversing some ac-

cepted history; to mark the finish of

the long congres-

sional quarrel between Massachusetts

and South Caro-

lina; and incidentally, to note the

collapse of the

"Duello."

When the thirty-fourth Congress met, on

the third

day of December, eighteen hundred and

fifty-five, it

registered the initial appearance of a

political party de-

voted to the territorial restriction of

slavery. The

House of Representatives was a chaotic

jumble of di-

verse elements which had been elected

more than a year

before as Whigs, Anti-Slavery Whigs,

Liberty Whigs,

Democrats, Anti-Slavery Democrats,

Coalition Demo-

crats, States-Rights Democrats,

Republicans, American

Republicans, Union Republicans,

Anti-Nebraska men,

Free-Soilers, Union men and Americans.

The Ameri-

cans were commonly called Know-Nothings

and, at the

time of their election constituted the

largest party. Since

the election, in 1854, a majority of

the Anti-Slavery

members had taken part in nationally

organizing the

Republican party to which they had

transferred their

allegiance. Rhodes, in his History of

the United States,

says that

(435)

436 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

The Congressional Globe, which

was accustomed to indicate

the partisan divisions by printing the

names of the members in

different type, now gave up the

classification in despair.

Woodrow Wilson, in his History of

the American

People, says:

What with Anti-Nebraska men and

Free-Soilers, Democrats.

Southern Pro-Slavery Whigs and

Know-Nothings, the House of

Representatives presented an almost

hopeless mixture and con-

fusion of party names and purposes.

The election of a Speaker was the first

thing in order.

With the exception of the regular

Democrats, it is un-

certain whether any of the numerous

parties was suffi-

ciently well organized to hold a

nominating caucus.

Henry Wilson, afterwards

Vice-President, in his Rise

and Fall of the Slave Power, says that

Richardson was the caucus nominee of the

democrats. * * *

The opposition scattered their votes

which, on the first calling

of the roll, were distributed among no

less than twenty candi-

dates. Campbell of Ohio received the

largest number. On the

sixth of December he withdrew his name.

Mr. Campbell had led on six ballots,

and gave as his

reason for withdrawal that he could not

be elected with-

out repudiating his well-known

principles on the subject

of slavery. He transferred his

following to N. P. Banks

of Massachusetts who had been elected

as a Coalition

Democrat and an American in a strong

anti-slavery dis-

trict, but who was now a Republican.

After that the

contest ran on until the sixth day of

February with Mr.

Banks in the lead. There being no

possibility that any

candidate could get a majority, an

agreement was made

that on the one hundred and

thirty-third ballot, a plural-

ity should nominate. Upon that ballot

Mr. Banks received

438

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

one hundred and three votes out of a

total of two hun-

dred and fourteen. In the meantime the

President's

message was withheld, the Senate had

been wholly idle

for two months and much of the public

business was at

a standstill.

Thus, after a contest, unequalled for

duration and

acrimony in national politics, the

various anti-slavery

elements were successfully combined

into a heterogene-

ous coalition which elected the Speaker

by a minority

vote. Such a complete break-up and

re-alignment of

political parties has no parallel in

history, and could

have resulted only from the acute

crisis arising over the

passage of the Kansas-Nebraska bill,

the fugitive slave

act, the repeal of the Missouri

compromise and the at-

tempted extension of slavery.

The people of the North, as a general

thing, acqui-

esced in the constitutional protection

of slavery in the

southern states, although sometimes

they were locally

riotous when fugitive slaves were

arrested in their

midst. The slaveholders, however, had

begun to claim

the right of owning and holding slaves

in the territories

-- especially the Territory of Kansas.

When it was

sought to further extend the actual

domain of slavery,

a moral question came into politics and

immediately

overshadowed all other issues.

The people of the South, conscious that

the death of

their "Peculiar Institution"

would be the ultimate result

of its territorial limitation, met this

paramount issue

with a heat born of desperation. In the

North, it was

a case of quickened conscience; in the

South, a case

largely of apprehended financial ruin,

but, also, to some

extent, it was an honest belief in the

beneficence of Afri-

440 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

can slavery, for the Richmond

Enquirer, the organ of

the simon-pure protagonists of slavery,

had laid down

the doctrine that

If slavery be not a legitimate, useful,

moral and expedient

institution, we cannot, without reproof

of conscience and blush

of shame, seek to extend it.

For almost two years a brisk guerrilla

warfare, entail-

ing much loss of life and property, had

been waged in

the disputed territory of Kansas --

known to this day

as "Bleeding Kansas." Both

sections of the country

were contributing men, money and the

famous "Sharp's

Rifles" to this conflict, of which

the most conspicuous

figure was that of "Old John Brown

of Osawatomie."

In the Senate, Seward of New York had

said that

Two candidates, each claiming to have

been elected to repre-

sent that territory in Congress, had

presented themselves at the

bar of the House. One had received some

three thousand votes

cast by the Missouri invaders, when

there were not fifteen hun-

dred voters in the territory.

Mr. Giddings wrote, later, that

These high-handed transactions were

consummated with

the express purpose of establishing

African slavery by force, in

violation of the rights of the people

solemnly guaranteed to them

by the Congress of the United States.

In the slave states, especially in

South Carolina,

threats of secession were freely and

publicly proclaimed;

and, in the North, there were

abolitionists who, by

speech and in print, denounced the

Federal Constitution

as a "Covenant with Hell."

Henry Wilson says that

Unfortunately the evidence is far too

conclusive to leave any

doubt as to the anarchical sentiment

that prevailed too generally

at the South and far too largely,

indeed, at the North.

Sumner -- Brooks -- Burlingame 441

As to the situation at that time in

Washington he

adds that

To the extreme arrogance of embittered

and aggressive words

were added the menace and actual

infliction of personal violence.

* * * Members of congress went armed in

the streets and sat

with loaded revolvers in their desks.

These preliminary facts are recited in

order that the

present generation may approximately

realize the fierce

sectional and political rancor which

preceded the Civil

War; for, while the cost of that

struggle may be stated

in blood and treasure, the bitter

animosities of which it

was the culmination are almost

incapable of adequate

portrayal.

One of the senators from Massachusetts

was Charles

Sumner, then in the prime of life, who,

although elected

to the Senate by a combination of

Democrats and Free-

Soilers, was now a member of the

recently organized

Republican party. His leonine head and

strong face

bespoke the ability and courage with

which he had been

amply endowed by his Puritan ancestors.

His polished

oratory, erudite scholarship and

unsympathetic tempera-

ment had united to develop an

inordinate egotism; and,

in his own estimation, the senatorial

mantle of Daniel

Webster (which had descended upon him)

was none too

large. He valued himself so highly that

he failed to

recognize the merit of his opponents;

and his manner

of speaking was often distinctly

offensive. In order

properly to understand the events

hereinafter described,

the following symposium of opinions in

regard to Mr.

Sumner is submitted. Representative E.

R. Hoar of

Massachusetts, later Attorney General

of the United

States, spoke of

442 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

His commanding presence, his stalwart

frame six feet and

four inches in height, the vigor and

grace of his motions, the

charm of his manners, the polish of his

rhetoric, the abundance

of his learning, the fervor and

impressiveness of his oratory.

* * * He never seems to have known fear.

* * * He

was of an imperious nature, intolerant

of differences of opinion

by his associates, and has been called

an egotist.

Senator George F. Hoar of Massachusetts,

says:

In him the egotism, often fostered by a

long senatorial career,

seems to have been natural. * *

* He could not understand

the state of mind of a man who could not

see as he did. * * *

It seems as if he thought the rebellion

itself was put down by

speeches in the senate, and that the war

was an unfortunate and

most annoying though trifling

disturbance -- as if a fire engine

had passed by.

Rhodes, the historian, says:

He was vain, conceited, fond of flattery

and overbearing in

manner.

But he also truthfully adds that he was

"the soul of

honor."

Charles Francis Adams wrote that

Sumner was a tremendous egotist, and

woefully lacking in

common sense.

Senator Morrill, of Vermont, said that

To his conclusions, sincerely reached,

he gave regal preten-

sions, and for them accepted nothing

less than unconditional sub-

mission.

General Grant, who never wasted words,

when told

that Sumner had no faith in the Bible,

replied, "That is

because he didn't write it."

John Sherman expressed the opinion of

Sumner that

Sumner -- Brooks -- Burlingame 443

The central idea of his political life

was hostility to slavery.

His hatred of slavery was fierce,

intense and morbid -- evinced

by such language of bitterness and

denunciation that no wonder

the holders of slaves construed his

invectives against the system

as personal insults demanding

resentment.

In spite of his vindictive hatred of

slavery, Senator

Sumner had no animosity toward the

Southern people.

After the war he moved that there be

stricken from the

regimental flags of our army the names

of all battles

fought against our countrymen. For this

a "bloody

shirt" legislature in

Massachusetts censured him; but,

later, stricken with proper shame at

such unpatriotic

action, it expunged the resolution of

censure.

Andrew Pickens Butler was a senator

from South

Carolina, elected as a States-Rights

Democrat, sixty-

two years of age, trembling with

partial paralysis, of

convivial habits and habitually

referred to in the South-

ern press as the "aged relative of

Mr. Brooks." Rhodes

says that

He was a man of fine family, older in

looks than his sixty

years, courteous, a lover of learning

and a jurist of reputation.

Giddings says

He was usually of gentle demeanor but

quite impatient of

opposition to questions touching

slavery. Whenever that institu-

tion came under debate, he assumed a

dictatorial tone, spoke dis-

respectfully of his opponents and, on

matters relating to Kansas,

he became offensive.

Von Hoist's Constitutional History describes

him as

South Carolina's pompous senator who

believed himself to be

made of different clay from ordinary

mortals.

Over seven years before, he was a

guest-of-honor at a

dinner where such toasts as

"Slavery" and "A Southern

Confederacy" were enthusiastically applauded. Al-

444 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

though he had achieved some distinction

in his ten years

in the senate, yet he had cut but a

small figure in com-

parison with his eminent predecessors

Calhoun, Hayne

and McDuffie.

Preston S. Brooks was a young

representative from

South Carolina of attractive appearance

and mediocre

ability. He sprang from one of the best

families; was

well educated; and had served three

years in Congress

where his conduct was always that of a

gentleman. In

Pierce's Life of Sumner, he is

described as

A modest and orderly member, indulging

in no acrimonious

speech and keeping aloof from scenes of

disorder. His pacific

manner and temperament had been

observed.

Mr. Burlingame, whom he challenged

later, said of

him in a newspaper card

From what I had heard and seen of him

prior to his assault

upon Mr. Sumner, I had formed a high

opinion of him.

Mr. Brooks also called himself a

"States-Rights

Democrat." Upon his only published likeness were

printed the words "Equal Rights to

the South as well as

to the North." The delusion that the South was im-

posed upon wholly dominated him. In a

speech in the

campaign following the occurrences

hereinafter nar-

rated, he said that

The election of Fremont should be the

signal for the South

to march at once to Washington, seize the treasury and

archives,

and force the North to attack them.

* *

* It is just to tear

the constitution of the United States,

trample it under foot and

form a Southern Confederacy. I have been

a disunionist from

the time I could think.

He had served with credit in the

Mexican War as a

Captain in the Palmetto Regiment; and,

later, had

446

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

fought a duel with a man named Wigfall.

So little did

he harbor resentment that later he

appointed Wigfall's

nephew as a cadet at West Point.

Lawrence M. Keitt was also a member of

the House

from South Carolina, and of that

distinct and high-

strung type then known as a

"Southern Fire-Eater."

By that phrase was meant a man whose

heart and soul

were wrapped up in the South and

particularly in the

institution of Slavery; who was

"game" to the core;

always set on a hair trigger; ready to

resent a real or

fancied insult to his state or section;

and a devotee of

the "Code Duello."

Interest attaches to the foregoing

incomplete sketches

of Sumner, Butler, Brooks and Keitt,

not only for what

follows hereafter, but because of the

antagonism that

had existed between Massachusetts and

South Carolina

since the Revolutionary War, and which

had repeatedly

broken out in Congress -- the most

prominent incident

of which had been the celebrated debate

between Web-

ster and Hayne.

Before going to Washington at this

session, Senator

Sumner said to his friend, Higginson,

"This session will

not pass without the Senate Chamber

becoming a scene

of some unparalleled outrage." On

the nineteenth and

twentieth of May, after having written

Theodore Par-

ker, "I shall pronounce the most

thorough philippic ever

uttered in a legislative body," he

delivered the most

powerful and vindictive of his many

great orations.

"The Crime Against Kansas"

was the stinging phrase

with which he scored the bloody deeds

enacted in the

attempt to foist slavery upon that

unhappy territory.

He truthfully denounced the Missourians

who had in-

Sumner -- Brooks -- Burlingame 447

vaded Kansas and who were known to the

world by the

opprobrious name of "Border

Ruffians." He stigma-

tized them as

Murderous robbers and hirelings picked

from the drunken

spew and vomit of an uneasy

civilization, lashed together by

secret lodges and renewing the

incredible atrocities of the As-

sassins and the Thugs.

On the State of South Carolina he made

this vitriolic

assault:

Has Senator Butler read the history of

the state which he

represents? He cannot surely have

forgotten its shameful imbe-

cility from slavery, confessed

throughout the Revolution, fol-

lowed by its more shameful assumptions

for slavery since. He

cannot have forgotten its wretched

existence in the slave trade as

the very apple of its eye, and the

condition of its participation in

the Union. * * * Were the whole

history of South Caro-

lina blotted out of existence, from its

very beginning down to the

day of the last election of the senator

to his present seat upon

this floor, civilization might lose -- I

do not say how little; but

surely less than it has already gained

by the example of Kansas

in its valiant struggle against

oppression. Ah, sir, I tell the

Senator that Kansas, welcomed as a Free

State, will be a min-

istering angel to the Republic when

South Carolina, in the cloak

of darkness which she hugs, lies

howling.

It was not reasonable to expect that

the South Caro-

linians should rest quietly under such

a bitter aspersion

of their native state.

Sumner's crushing invectives were also

hurled with

open scorn at the senators whom he

deemed to be the

defenders of the lawless invasions of

Kansas; and he es-

pecially pilloried Senator Butler and

Senator Stephen

A. Douglas, of Illinois, stating that

"as the Senator

from South Carolina is the Don Quixote

of slavery, the

Senator from Illinois is the squire of

slavery, its very

Sancho Panza, ready to do all its humiliating

offices." He

448

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

spoke of Butler's "loose

expectoration of speech and his

uncalculating fanaticism;" and

said of him that

He has chosen a mistress to whom he has

made his bows and

who, though ugly to others, is always

lovely to him; though pol-

luted in the sight of the world, is

chaste in his sight. I mean the

harlot, Slavery.

Butler was not present during this

speech, and Mc-

Master, in his History of the People

of the United

States, expressed the general sentiment in saying that

it was not "fair to Butler who was

absent." The speech

was issued in enormous editions; it is

estimated that

within two months after its delivery a

million copies had

been distributed.

When Mr. Sumner closed, a flood of

vituperation

broke loose on both sides of the

chamber. To a sharp

thrust of Mr. Douglas, Mr. Sumner

retorted that "the

bowie-knife and the bludgeon are not

the proper em-

blems of debate." Senator Douglas spoke bitterly of

what he designated as "the depth

of malignity that is-

sued from every sentence of Mr.

Sumner's speech; "but,

during its delivery, he had said to a

friend, "Do you hear

that man? He may be a fool, but I tell

you he has pluck.

*

* * I am not sure whether I

should have the cour-

age to say those things to the men who

are scowling

around him." When Mr. Butler

returned to the Senate,

a few days later, he revenged himself

by denouncing

Mr. Sumner as a "calumniator, a

fabricator and a

charlatan."

Two days later, when the Senate was not

in session.

Mr. Brooks entered the chamber where he

found Sena-

tor Sumner writing at his desk. He said

to him, "I have

read your speech twice over carefully.

It is libel on

450

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

South Carolina and on Mr. Butler who is

a relative of

mine." Had he stopped there, no

one could have justly

criticised him, but he proceeded to

beat the unsuspecting

Senator over the head with a thin

gutta-percha cane.

Although dazed by the attack, Mr.

Sumner exhibited his

enormous strength by wrenching the desk

from the floor.

By that time, however, the angry blows

had done their

work; and, bleeding and unconscious, he

was carried to

an ante-room for medical aid. His

injuries were far

more serious than were intended by Mr.

Brooks who,

before his temper got the better of

him, merely wished

to disgrace Mr. Sumner by a public

whipping. These

injuries disabled him for many years,

during which time

he sought medical treatment both in

Europe and Amer-

ica. He lived long enough, however, to

show his innate

nobility of character when, standing by

the cenotaph of

Mr. Brooks, he exclaimed, "Poor

fellow, he was the

unconscious agent of a malign

power." During the as-

sault Mr. Keitt was present and warned

off all who

might interfere--especially Senator

Crittenden, who

was protesting against the outrage.

Instantly the entire North blazed into

indignation.

The City of Lawrence, built by the

free-state men of

Kansas, had just been burned by an

armed mob of pro-

slavery raiders from Missouri; and the

cry was raised

that the "city dedicated to

freedom" had been destroyed,

and that the "champion of

freedom" had been struck

down by a "bully" -- that

being the opprobrious epithet

which followed Mr. Brooks to his grave.

Public meet-

ings were held everywhere, Beecher and

Evarts spoke

in New York; Francis Wayland in

Providence; Long-

fellow in Boston; Emerson in Cambridge;

Edward

Sumner -- Brooks -- Burlingame 451

Everett in Taunton; and men of the same

stamp, such

as William Cullen Bryant, Josiah Quincy

and E. R.

Hoar, in many other town and cities.

Oliver Wendell

Holmes, at the dinner of the

Massachusetts Medical

Society, gave the following toast,

"The surgeons of the

City of Washington; God grant them

wisdom for they

are dressing the wounds of a mighty

empire, and of un-

counted generations;" and William

H. Seward said in

the Senate "the blows that fell on

the head of the sena-

tor from Massachusetts have done more

for the cause

of human freedom in Kansas and in the

Territories of

the United States than all the

eloquence which has re-

sounded in these halls." Whittier

wrote of Sumner's

speech that it was a 'grand and

terrible philippic worthy

of the occasion." Innumerable

letters were written, de-

nouncing the assault, by such men as

Salmon P. Chase,

Thurlow Weed and E. L. Godkin. Yale and

Amherst

conferred upon Mr. Sumner the degree of

Doctor of

Laws. The whole world stood aghast at

the spectacle

of a bloody assault in the Senate

chamber. Especially

was this true of England; Macaulay

wrote the Duchess

of Argyll, wife of a cabinet minister,

that "in any coun-

try but America I should think that civil

war was immi-

nent;" and Cornwall Lewis, also a

cabinet minister,

wrote that "this outrage is not

proof of brutal manners

or low morality in America --it is the

first blow in a

civil war." Mr. Lewis was right;

it was the first blow

in a civil war.

The wrath and dismay of the North were

equaled

only by the delight and exultation of

the South. Her

most trusted and prominent citizens

publicly applauded

Mr. Brooks; the students of the

University of Virginia

452

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

passed a resolution of commendation;

and William Gil-

more Simms, the best known poet of the

South, joined in

the universal paean. Jefferson Davis,

in reply to an in-

vitation to a dinner given to Mr.

Brooks, wrote "I have

only to express my sympathy for the

sentiment which

prompts the sons of Carolina to welcome

the return of

a brother who has been the subject of

vilification, mis-

representation and

persecution." Senator Mason of

Virginia, on the same occasion, wrote,

"I know of none

whose public career I hold more worthy

of the full and

cordial approbation of his

constituents." The news-

papers of the South were almost

unanimous in com-

mending Mr. Brooks. The Richmond

Enquirer said,

"He deserves applause for the bold

and judicious man-

ner in which he chastised the scamp,

Sumner;" and

later, "It is idle to talk of

Union or peace or truce with

Sumner or Sumner's friends." The Richmond Whig.

in an editorial entitled "A Good

Deed," commented as

follows: "We are exceedingly sorry

that Mr. Brooks

dirties his cane by laying it athwart

the shoulders of the

blackguard, Sumner." The Carolina

Times said

"Colo-

nel Brooks has immortalized himself,

and he will find

that the people of South Carolina are

ready to endorse

his conduct." The Washington

Sentinel said, "If Mas-

sachusetts will not recall such a man,

if the Senate will

not eject or control him, there is

nothing to do but to

cowhide bad manners out of him or good

manners into

him." At Washington, the headquarters of the pro-

slavery propaganda, a banner was

carried which bore

this dastardly inscription,

"Sumner and Kansas--let

them bleed." A cane presented to

Brooks by citizens

of Charleston bore the inscription

"Hit him again."

Sumner -- Brooks -- Burlingame 453

Another, presented by his constituents,

was inscribed,

"Use knock-down arguments."

Other canes, with kin-

dred inscriptions, were fairly showered

on him.

Looking back at these scenes and

sentiments in the

South, how incomprehensible they seem!

Here was a

man, naturally gentle, committing an

offense confessedly

brutal and unmanly, while an entire

section, whose un-

surpassed valor was proven later in a

stubborn and

bloody war, went wild with joy. Verily

madness, born

of slavery, must temporarily have

blinded a brave and

generous people.

The assault upon Mr. Sumner was made

long before

the present wings of the Capitol

Building were

completed, hence it was but a short

distance from the

House to the Senate -- the House

sitting in what is now

the Statuary Hall and the Senate in the

present Su-

preme Court Room. Lewis D. Campbell, of

Ohio, was

Chairman of the House Committee on Ways

and Means.

At that time there was no Committee on

Appropriations,

and the Ways and Means Committee raised

and ex-

pended the entire revenues of the

Federal Government.

Consequently the chairman was majority

floor leader

in a sense more important than even at

the present day.

He was sent for by the Senate authorities

and arrived

before Mr. Sumner was removed to the

ante-room. As

soon as Mr. Sumner's injuries were

temporarily pro-

vided for, he returned to the House,

and offered a reso-

lution to investigate the conduct of

Mr. Brooks and Mr.

Keitt, and was made chairman of the

committee for that

purpose which, later, reported a

resolution recommend-

ing the expulsion of Mr. Brooks and the

censure of Mr.

Keitt. A heated discussion ensued in

which Mr. Cling-

454

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

man, of North Carolina, subsequently a

distinguished

confederate general, led the debate by

asserting that Mr.

Sumner had received "a merited

chastisement," and elo-

quently defended what he termed the

"liberty of the

cudgel." One northern man, Mr.

Giddings, of Ohio,

seemed inclined to partially condone

the conduct of Mr.

Brooks because of his political

education and environ-

ment. The vote on the expulsion of Mr.

Brooks stood

one hundred and twenty-five yeas and

ninety-five nays

--not the necessary two-thirds;

nevertheless he re-

signed immediately. Upon leaving the

House, he was

met at the door by a bevy of southern

belles who pro-

ceeded to smother him with kisses -- an

unconventional

form of public approbation to which he

submitted with

becoming resignation. Mr. Keitt, having

been censured

by the House, resigned also. A few days

later (at a spe-

cial election) both men were

unanimously re-elected.

The day after the assault, Senator

Wilson of Massa-

chusetts denounced Mr. Brooks in the

Senate, and said

that "Mr. Sumner was stricken down

on this floor by a

brutal, murderous and cowardly

assault," to which Mr.

Butler promptly retorted, "You are

a liar." Mr. Brooks

took up the quarrel and challenged

Senator Wilson who

replied that he would not fight a duel

but, if attacked,

would defend himself. Representative

Woodruff of

Connecticut, also denounced the assault

and was chal-

lenged by Mr. Brooks, but his reply was

the same as

Senator Wilson's.

As Mr. Campbell had offered the motion

calling for

an investigation against Mr. Brooks and

Mr. Keitt and

had been Chairman of the Committee

which reported

the resolution to expel Mr. Brooks and

censure Mr.

Sumner -- Brooks -- Burlingame 455

Keitt, it may be interesting to explain

why he was not

challenged. Although a militant

antagonist of the slave

power at every stage of the fight

against it, he was a

general social favorite, a man of

convivial tastes and

unusually popular with the southern

members. On the

day after the assault, while walking

with one of them

on Pennsylvania Avenue, his companion

said to him,

"Lew, they are going to challenge

you today." Mr.

Campbell made no reply until they

passed a shooting

gallery; when, turning back, he invited

his friend to

enter. Asking the proprietor to remove

the customary

target and replace it with a lighted

candle, he proceeded

to snuff that candle with a rifle ball,

"off-hand" three

times in succession. It is hardly

necessary to add that

the subject of his challenge was never

afterward alluded

to, for the certainty of death has a

tendency to cool the

ardor of the most persistent duelist.

Nobody having accepted the challenges

of Mr. Brooks,

the incident would have closed but for

Representative

Anson Burlingame, the youngest member

from Massa-

chusetts -- an orator who possessed the

unusual accom-

plishments of making a campaign on a

single speech and

yet, by his charm of voice and manner,

causing its mo-

notonous repetition to pass unnoticed.

He was a bitter

foe of slavery, a fine rifle shot and

had the reputation

of being "a northern man who would

fight." He waited

patiently for a month before his

indignation burst forth,

and then he made himself a shining mark

by the delivery

of a carefully prepared speech in which

he said that Mr.

Brooks "stole into the Senate,

that place which had been

sacred against violence, and smote Mr.

Sumner as Cain

smote his brother." He also

defamed the loyalty of

456

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

South Carolina in the Revolutionary

War, and said that

"Massachusetts had furnished more

than ten times as

many men as South Carolina." As to

the assault he

said, "I denounce it in the name

of the constitution

which it violated; I denounce it in the

name of the sov-

ereignty of Massachusetts which was

stricken down by

the blow; I denounce it in the name of

civilization which

it outraged; I denounce it in the name

of humanity; I

denounce it in the name of that fair

play which even bul-

lies and prize-fighters respect."

In closing he said,

"There are men from the Old

Commonwealth of Massa-

chusetts who will not shrink from a

defense of the free-

dom of speech, and the honored state

they represent, on

any field where they may be

assailed."

Mr. Brooks not unnaturally construed

Mr. Burlin-

game's speech to mean that he would

accept a challenge,

and sent a friend to him; but, in a few

days, an apolo-

getic note was returned (in the

handwriting of Mr.

Burlingame's colleague, Speaker Banks)

stating that

Mr. Burlingame "disclaimed any

intention to reflect

upon the personal character of Mr.

Brooks, or to impute

to him in any respect a want of

courage; but discrimi-

nating between the man and the act

which he was called

upon to allude to, he had characterized

the latter only

in such a manner as his representative

duty required him

to do." The New England press, led

by the Boston

Courier, commented sharply on Mr. Burlingame's con-

cession and severely upbraided him for

so palpably

showing what they appropriately termed

"the white

feather." His colleague, Timothy

Davis, called his at-

tention to these unfavorable comments.

Stung by such

unanimous expressions of the sentiment

of his friends

Sumner -- Brooks --

Burlingame 457

and constituents, he applied to Mr.

Campbell for advice

and was told that, if his speech in the

House was sincere,

the only course open to him was to

stand by it and ac-

cept the consequences. Thereupon Mr.

Burlingame

published a card in the National

Intelligencer in which,

referring to his apologetic note, he

said, 'Inasmuch as

attempts, not altogether unsuccessful,

have been made

to pervert its true meaning, I now

withdraw it; and, that

there may not be any misapprehension in

the future I

say, explicitly, that I leave my speech

to interpret itself,

and hold myself responsible for it

without qualifications

or amendment."

Mr. Brooks immediately sent Mr.

Burlingame the

following challenge:

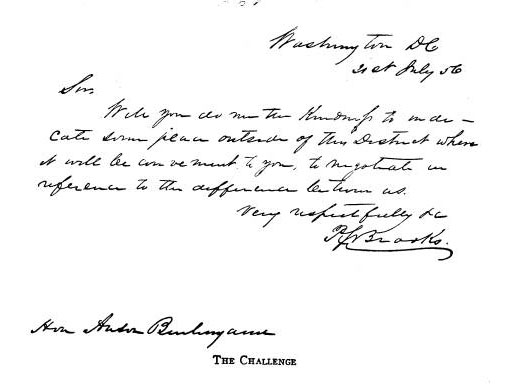

Washington, D. C., 21st July, '56.

SIR:--

Will you do me the kindness to indicate

some place outside

of this District where it will be

convenient to you to negotiate in

reference to the difference between us.

Very respectfully, etc.,

P. S. BROOKS.

Hon. Anson Burlingame.

The peculiar words, "outside of

this district," used in

this challenge were necessary in order

to evade the stat-

ute of the District of Columbia which

forbade dueling or

challenging within the district. To us,

so far past the

dueling age, it may seem strange that

many men in 1856

felt it to be a dishonor to refuse a

challenge; yet, nearly

all of the greatest men, in former days,

were duelists.

Randall and Ryan's History of Ohio pertinently

says

that "the list of duelists makes

the quiet and decent citi-

zen of today shudder with

amazement." Three presi-

dential candidates were in that

category--Jackson

Sumner -- Brooks --

Burlingame 459

killed Dickinson the defamer of his

wife; Clay, although

he publicly denounced dueling, fought

both Randolph

and Marshall; and Crawford of Georgia,

the Demo-

cratic candidate in 1824, killed Van

Allen in one duel

and was wounded by Clark in another.

Colonel Laurens,

while on Washington's staff, fought the

traitor Charles

Lee (whom Washington had cursed at

Monmouth) and

there is no evidence that Washington

criticised his con-

duct. So great was the interest taken

in dueling by

public men that, when Barron killed

Decatur at Bladens-

burg, there were present Commodores

Rodgers, Porter

and Bainbridge; and when Representative

Graves killed

Representative Cilley at Bladensburg

there were present

Senator Crittenden, and Representatives

Jones, Bynum,

Wise, Calhoun, Hawes, Menifee and

Duncan -- the

last-named from the state of Ohio. This

latter duel was

fought in 1838 and was so utterly

causeless that it was

popularly known as the "Washington

Murder." It was

used against the Whigs in the campaign

of 1844, and

was the cause of much revulsion in

public sentiment, in

regard to dueling, although in 1856 it

still required more

courage to refuse a challenge than to

accept one.

Under the Code Duello nothing was better

known

than that the place selected for a duel

(using the exact

but inelegant language of the code)

"must be such as

had been ordinarily used where the

parties are." Bla-

densburg, five miles from Washington,

was the ancient

and well established dueling ground.

Americana states

that "Bladensburg is famous in

American history as

the site of the dueling ground where

many famous duels,

growing out of quarrels in Washington,

were fought."

None of the Washington duels had been

fought at a dis-

460

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

tance greater than nine miles from the

Capitol. Both

Mr. Campbell and Mr. Burlingame were

aware of the

above facts and also knew that Mr.

Brooks could not

safely travel through the North for a

long distance,

owing to the intense feeling aroused by

the recent as-

sault. Therefore, when he applied to

Mr. Campbell,

Mr. Burlingame put that friend of his

in the trying pre-

dicament of devising an acceptance

which would save

Mr. Burlingame's reputation and yet, if

possible, avoid

a fight. It occurred to Mr. Campbell

that, if the

Canadian side of Niagara Falls should

be named, Mr.

Brooks would thereby be maneuvered into

the humiliat-

ing position of declining to go to a

place of which, later,

he truthfully wrote, "I could not

reach Canada without

running the gauntlet of mobs and

assassins, prisons and

penitentiaries, bailiffs and constables.

* * * I might

as well have been asked to fight on

Boston Common."

With this in view, Mr. Campbell drafted

the following

acceptance. While it cannot be denied

to be a trifle cun-

ning, it must be admitted that it was

certainly resource-

ful:

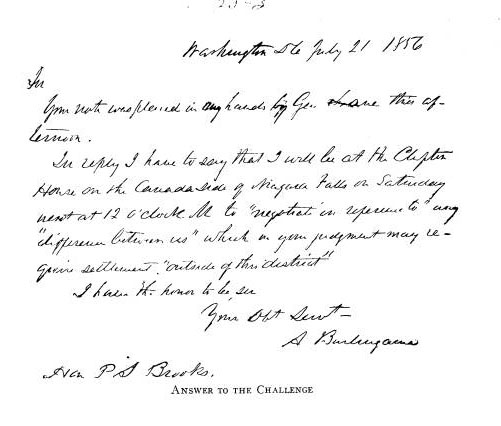

Washington, D. C., July 21, 1856.

SIR:--

Your note was placed in my hands by Gen.

Lane this after-

noon.

In reply I have to say that I will be at

the Clifton House on

the Canada side of Niagara Falls on

Saturday next at 12 o'clock

M. to "negotiate" in reference

to "any differences between us"

which in your judgment may require

settlement "outside of this

district."

I have the honor to be, sir,

Your Obt. Servt.,

A. BURLINGAME.

Hon. P. S. Brooks.

462 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

Mr. Burlingame copied it and the copy

was handed

to General Lane, who acted as second

for Mr. Brooks.

Mr. Campbell never denied the charge

that he purposely

named an impossible place for the

meeting, but he felt

absolved from complying with the usual

custom in that

respect because, thereby, he prevented

a duel which was

certain to be bloody and, probably,

fatal.

The newspapers all over the United

States and

Canada contained full and frequent

accounts of the pro-

posed meeting at Niagara Falls. Mr.

Brooks, as had

been anticipated, refused to go to

Canada. His refusal,

artfully misrepresented, created the

impression in the

North that he would not fight at all

but that Mr. Bur-

lingame was willing to go anywhere for

that purpose.

Great was the rejoicing over what was

called "The

Backdown of Bully Brooks." The Hartford

Courant,

representing the northern press, said

that "Burlingame

was ready to go to South Carolina but

Preston S.

Brooks dare not go to Canada."

John P. Hale, repre-

senting northern citizenship, wrote

that Mr. Burlingame

"had staked his life upon the

result, preferring death to

his own and his state's dishonor."

A lot of sarcastic

doggerel was published in the New

York Evening Post,

the first stanza of which read as

follows:

"To Canada Brooks was asked to go

To waste of powder a pound or so.

He sighed as he answered no, no, no,

They might take my life on the way, you

know."

The historians, and other writers, have

also er-

roneously accepted this view of the

situation; and have

depicted Mr. Brooks as a coward and Mr.

Burlingame

as a hero. The National Cyclopedia

of American Bi-

Sumner -- Brooks

-- Burlingame

463

ography says, "The manner in which Mr. Burlingame

conducted himself greatly raised him in

the estimation

of his friends and his party; and, on

his return to Bos-

ton at the end of his term, he was

received with distin-

guished honors." This statement is

especially untrue

as Mr. Burlingame did not "return

to Boston" but, for

reasons which will be shown later, was

rapidly traveling

in another direction. Even as late as

the memorial

service in honor of Mr. Burlingame (as

an eminent

diplomat) by the New York Chamber of

Commerce in

1870, William E. Dodge, in his eulogy,

said that Mr.

Burlingame was "a keen shot with

the rifle, who would

not shrink even from a duel if used in

defense of honor,

liberty and his friends." It is

still more astonishing

that Representative Galusha A. Grow,

who was a prom-

inent member of that Congress and

Speaker of the

thirty-seventh Congress, seems never to

have heard that

there was a sequel to this affair. As an active anti-

slavery agitator, who had a fist fight

on the floor of the

House two years later with Mr. Keitt,

he should have

been conversant with all of the facts;

yet, in an article

on "The Duello," published

many years afterward, he

says, "Brooks at once challenged

Burlingame, but this

time he encountered a northern man

ready to fight him

in his own way. * * * Brooks declined

to go to

Canada. The affair thus ended."

But the affair had not ended; neither

was Mr. Bur-

lingame ready to fight Mr. Brooks

"in his own way" or

in any other way, or at any other time

or place. He was

actively interested only in the

pusillanimous purpose of

getting where he could not be served

with a challenge

to fight within a reasonable distance

of Washington, or

464 Ohio

Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

in a locality safely accessible to both

parties. Although

the session lasted five weeks longer,

and legislation of

the utmost importance was pending, Mr.

Burlingame

appeared but once in the House -- a few

moments on

July 28. On that day, however, he made

the following

statement, the hypocrisy of which will

appear as this

article unfolds: "I thought Mr.

Brooks was in earnest

and prepared to meet him sternly and

without fail. If

he was afraid to go to Canada, the

nearest neutral

ground, why did he not name some other

place ?" Mark

these words "some other

place."

On the same day Mr. Burlingame

permanently disap-

peared from Washington, and nobody but

Mr. Camp-

bell (who had ostensibly disconnected

himself from this

affair two days before) knew where he

was. General

Lane, who had commanded the left wing

at Buena Vista

and had the most conspicuous military

record of any

man in Congress, was still acting as

second to Mr.

Brooks and was then diligently seeking

for Mr. Bur-

lingame. He continued to do so

persistently, but un-

successfully, until the 30th. On that

day he handed Mr.

Campbell a letter which disclosed the

insincerity of Mr.

Burlingame when, in the statement above

quoted, he had

said, "Why did he not name some

other place." The

letter, which was directed to Mr.

Campbell under the

impression that he was still Mr.

Burlingame's second,

reads as follows:

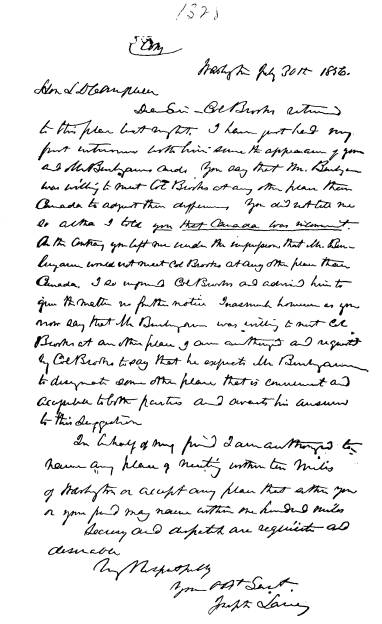

Washington, July 30th, 1856.

HON. L. D. CAMPBELL.

DEAR SIR:--

Col. Brooks returned to this place last

night. I have just had

my first interview with him since the

appearance of your and

Mr. Burlingame's cards. You say that

Mr. Burlingame was

willing to meet Col. Brooks at any

other place than Canada to

Sumner -- Brooks -- Burlingame 465

adjust this difference. You did not tell

me so although I told

you that Canada was inconvenient. On

the contrary, you left me

under the impression that Mr. Burlingame

would not meet Col.

Brooks at any other place than Canada. I

so informed Col.

Brooks and advised him to give the

matter no further notice. In-

asmuch, however, as you now say that Mr.

Burlingame was

willing to meet Col. Brooks at any other

place, I am authorized

and requested by Col. Brooks to say that

he expects Mr. Bur-

lingame to designate some other place

that is convenient and ac-

ceptable to both parties, and awaits his

answer to this suggestion.

In behalf of my friend I am authorized

to name any place of

meeting within ten miles of Washington,

or accept any place that

either you or your friend may name

within one hundred miles.

Secrecy and dispatch are requisite and

desirable.

Very respectfully,

Your Ob'd't Ser't,

JOSEPH LANE.

If Mr. Burlingame really wished to name

"some

other place" where they could fight, or was actually

ready to meet his antagonist on equal

terms, what a

glorious chance was offered him. A

hundred miles (as

suggested by General Lane) would have

taken them

into a free state -- say to Gettysburg

in the state of

Pennsylvania -- where, in miniature,

they might have

anticipated the Great Battle fought

there seven years

later.

Upon receipt of the foregoing letter

Mr. Campbell

notified General Lane that his

connection with Mr. Bur-

lingame's affairs had terminated on the

26th. As there

was much mystery about Mr. Burlingame's

sudden dis-

appearance, General Lane (who may have

had the im-

pression that Mr. Campbell was also

seeking to evade

responsibility) wrote him the following

letter:

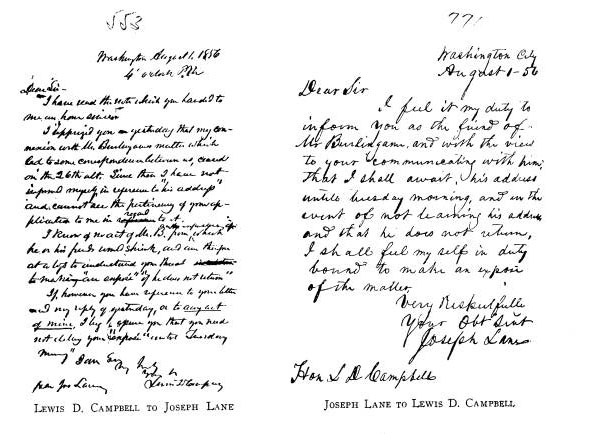

|

|

|

(466) |

Sumner -- Brooks -- Burlingame 467

Washington City,

August 1, '56.

DEAR SIR:--

I feel it my duty to inform you as the

friend of Mr. Bur-

lingame, and with the view to your

communicating with him, that

I shall await his address until Tuesday

morning, and in the event

of not learning his address, and that he

does not return, I shall

feel myself in duty bound to make an

expose of the matter.

Very Respectfully,

Your Obt. Servt.,

JOSEPH LANE.

Hon. L. D. Campbell.

Mr. Campbell, being a trifle peppery,

would not rest

under an imputation, however vague, and

the following

reply was promptly delivered to General

Lane:

Washington, August 1, 1856.

DEAR SIR:--

I have read the note which you handed to

me an hour since.

I apprised you yesterday that my

connection with Mr.

Burlingame's matter, which led to some

correspondence between

us, ceased on the 26th ult. Since then 1

have not informed my-

self in reference to "his

address" and cannot see the pertinency

of your application to me in regard to

it.

I know no act of Mr. B. from an exposure

of which he or

his friends would shrink, and am

therefore at a loss to understand

your threat to make "an

expose" if he does not return.

If, however, you have reference to your

letter and my reply

of yesterday, or to any act of mine, I

beg to assure you that you

need not delay your "expose"

until Tuesday morning.

I am, sir,

Very truly,

LEWIS D. CAMPBELL.

Hon. Jos. Lane.

Obviously Mr. Campbell intended to

stand by his

guns, but what of the elusive

Burlingame? At the very

moment in which Mr. Burlingame was

striving to shield

him by "talking back" at

General Lane, he was securely

Sumner - Brooks - Burlingame 469

ensconced in Mr. Campbell's home in

Hamilton, Ohio.

At the safe distance of six hundred

miles he was writ-

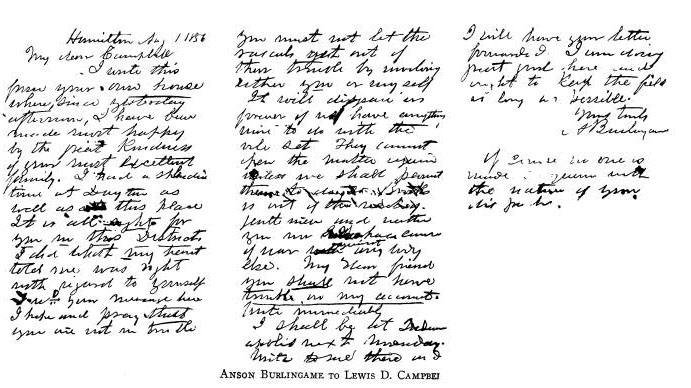

ing the following melodramatic letter:

Hamilton, Aug. I, 1856.

MY DEAR CAMPBELL:--

I write this from your own home where,

since yesterday after-

noon, I have been made most happy by the

great kindness of your

most excellent family. I had a splendid

time in Dayton as well

as at this place. It is all right for

you in this district. I did what

my heart told me was right with regard

to yourself. I rec'd your

message here. I hope and pray that you

are not in trouble. You

must not let the rascals get out of

their trouble by involving either

you or myself.

It will disgrace us forever if we have anything

more to do

with the vile set. They cannot open the

matter again unless we

permit them to do so. Brooks is out of

the reach of gentlemen

and neither you nor I have cause of war

against anybody else.

My dear friend you shall not have

trouble on my account.

I shall be at Indianapolis next Monday.

Write me there and

I will have your letter forwarded. I am

doing great good here

and ought to keep the field as long as

possible.

Yours truly,

A. BURLINGAME.

Of course, no one is made acquainted

with the nature of your

dispatch.

The secret is out! Mr. Burlingame,

fleeing from the

"Field-of-Honor", is at a

distance of two days' travel

with his back to the foe and bound, via

Indianapolis, for

parts unknown.

As an indication that Mr. Burlingame

was seeking to

avoid an expected challenge from Mr. Brooks to fight

at "some other place" so

located as to be fair to both

parties, note his admission that

"they cannot open the

matter again unless we permit them

to do so." For fur-

ther corroboration, mark the admonition

that "you must

not let the rascals get out of their

trouble by involving

Sumner -- Brooks -- Burlingame 471

either you or myself." There was no danger of "in-

volving" Mr. Burlingame as he was

too far away and

too safely concealed. "My dear

friend you shall not

have trouble on my account," says the would-be duelist

to the friend whom he had left in the

breach. Who was

to prevent Mr. Campbell from having

"trouble" -- cer-

tainly not this wandering deserter.

Luckily for Mr.

Burlingame's "dear friend,"

Campbell, that gentleman's

attitude had won the respect of Mr.

Brooks and General

Lane, and he did not heed the

long-distance sympathy

of his fugitive correspondent.

The next session of Congress began in

December.

Mr. Brooks was then very ill and died

in January, but

not before he confessed to his

colleague, Mr. Orr, that

he was sick of being regarded as a

representative of

bullies and disgusted at receiving

testimonials of their

esteem. Long afterwards, in Faneuil

Hall, Mr. Bur-

lingame was sufficiently magnanimous

(or remorseful)

to do justice to Mr. Brooks by

defending him from un-

just aspersions. Mr. Campbell, some

years later, also

exonerated Mr. Brooks by publishing a

statement that

"the popular opinion that Mr.

Brooks was a coward is

far from correct. He was sensitive and

impetuous, but

had many excellent traits of character."

No more duels

were fought thereafter between American

statesmen;

and the Code Duello had become so

completely extinct

that, in the State of South Carolina,

where dueling had

borne its most knightly flower, no man

can hold public

office until he has filed a sworn

statement that he was

never connected with a duel.

472 Ohio Arch. and Hist.

Society Publications

In 1861, when the time for real

fighting came, South

Carolina, true to her theories and

traditions, was the

first state to secede. Massachusetts,

also true to her

theories and traditions, put the first

Union regiment

into the field and laid the first

living sacrifices upon the

altar of loyalty. But what of the men

who were promi-

nent in the scenes which have been

herein narrated?

Mr. Brooks and Senator Butler were dead,

and General

Lane was too old to take part in the

struggle. Senator

Sumner had not fully recovered from his

injuries, al-

though, in the Senate during the entire

war, he was a

tower of strength to the Union cause.

Senator Douglas

had held the hat of his former Great

Antagonist, Abra-

ham Lincoln, while that predestined

martyr delivered

his inaugural address. When the guns

roared at Sum-

ter, the inborn patriotism of Douglas

blazed up and he

forgot his life-long political warfare

with the President,

and their great historic debates. He

instantly took upon

himself the mission of bringing his

enormous personal

following into the field. In this he

succeeded fully and

promptly, but at the expense of his

life. Within two

months after the war began, he succumbed

to the im-

mense overstrain upon his physical

powers. Speaker

Banks was one of the first major

generals appointed by

President Lincoln, and served

faithfully until the close

of the war. Mr. Campbell and Mr. Keitt

commanded

regiments from their respective states;

and the latter

gave his life for the South on the

Field of Cold Harbor.

Of those who were alive and of fighting

age, only one

failed to go to the war. That one was

Anson Bur-

lingame. Instead of the Field of

Battle, he chose the

Field of Diplomacy in which he achieved

great and de-

|

Sumner -- Brooks -- Burlingame 473 served success. His failure to enlist occasioned much comment which has not yet died out. In a recent article, Newman, who writes under the name of "Savoyard," says: Mr. Burlingame was a combative man, acquainted with weap- ons and skillful in their use, and we instinctively associate his name with arms. Thus it will always be a subject for the curious that Massachusetts did not send Anson Burlingame to the war. There may have been good and sufficient reasons why Mr. Burlingame did not embrace this well-timed oppor- tunity to display his martial prowess; nevertheless, it is to be deplored that one who, before the war, professed such readiness to fight, should not have inscribed his name among those of the other orators and statesmen with which Massachusetts emblazoned THE MUSTER ROLL OF THE UNION. NOTE--Governor James E. Campbell died December 17, 1924. The preceding contribution was read by him before the Kit Kat Club in 1922. |

|

|

SUMNER -- BROOKS -- BURLINGAME

--or--

THE LAST OF THE GREAT CHALLENGES

BY JAMES E. CAMPBELL

The purpose of this paper is to throw

light upon one

of the most famous of the many

thrilling episodes which

preceded the Civil War -- thereby

reversing some ac-

cepted history; to mark the finish of

the long congres-

sional quarrel between Massachusetts

and South Caro-

lina; and incidentally, to note the

collapse of the

"Duello."

When the thirty-fourth Congress met, on

the third

day of December, eighteen hundred and

fifty-five, it

registered the initial appearance of a

political party de-

voted to the territorial restriction of

slavery. The

House of Representatives was a chaotic

jumble of di-

verse elements which had been elected

more than a year

before as Whigs, Anti-Slavery Whigs,

Liberty Whigs,

Democrats, Anti-Slavery Democrats,

Coalition Demo-

crats, States-Rights Democrats,

Republicans, American

Republicans, Union Republicans,

Anti-Nebraska men,

Free-Soilers, Union men and Americans.

The Ameri-

cans were commonly called Know-Nothings

and, at the

time of their election constituted the

largest party. Since

the election, in 1854, a majority of

the Anti-Slavery

members had taken part in nationally

organizing the

Republican party to which they had

transferred their

allegiance. Rhodes, in his History of

the United States,

says that

(435)

(614) 297-2300