Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

- 34

- 35

- 36

- 37

- 38

- 39

- 40

- 41

- 42

- 43

- 44

- 45

- 46

- 47

- 48

- 49

- 50

- 51

- 52

- 53

- 54

- 55

- 56

- 57

- 58

- 59

- 60

- 61

- 62

- 63

- 64

- 65

- 66

- 67

- 68

- 69

- 70

- 71

- 72

- 73

- 74

- 75

- 76

- 77

- 78

- 79

- 80

- 81

- 82

- 83

- 84

- 85

- 86

- 87

- 88

- 89

- 90

- 91

- 92

- 93

- 94

- 95

- 96

- 97

- 98

- 99

- 100

- 101

- 102

- 103

- 104

- 105

- 106

- 107

- 108

- 109

- 110

- 111

- 112

- 113

- 114

- 115

- 116

- 117

- 118

- 119

- 120

- 121

- 122

- 123

- 124

- 125

- 126

- 127

- 128

- 129

- 130

- 131

- 132

- 133

- 134

- 135

- 136

- 137

- 138

- 139

- 140

- 141

- 142

- 143

- 144

- 145

- 146

- 147

- 148

- 149

- 150

- 151

- 152

- 153

- 154

- 155

- 156

- 157

- 158

|

EXCAVATION OF THE COON MOUND AND AN ANALYSIS OF THE ADENA CULTURE E. F. GREENMAN, CURATOR OF ARCHAEOLOGY |

|

|

EXCAVATION

OF THE COON MOUND AND AN

ANALYSIS

OF THE ADENA CULTURE

TABLE

OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Introductory

Note..................................... 369

General

Features of the Coon Mound ..................... 370

Contents

of the Mound

.............................. .. 375

The Burial....................................... 375

The Tomb

........................................ 379

The Gravel

Circle ................................. 387

The

Horizontal Log-Molds .......................... 392

The

Passage ................................... 397

Reconstruction

................................... 400

Conclusion .........................................

. 408

The

Adena Culture.................................... 411

Introductory Note

....................................... 411

Explanation of

Tables ................................. 414

Table A

............................................. 420

Table B

.............................................. 425

Table C

.................

.......... 442

Table D

............................................. 446

Table E

................................................... 446

Table F .............................................. 447

Discussion of Traits

1 to 59

.............................. 450

Discussion

of Traits Listed in Table C .................... 478

Conclusion ........................................

.. 487

Comparison

of Adena and Hopewell ................. 487

Identity

of the Adena People ....................... 493

Bibliography

........................................ 503

(367)

EXCAVATION OF THE COON MOUND AND AN

ANALYSIS OF THE ADENA CULTURE

E. F. GREENMAN

CURATOR OF ARCHAEOLOGY

INTRODUCTORY NOTE

The Coon Mound receives its name from

Mr.

Gabriel Coon, the owner of the land

upon which the

mound was situated, in The Plains,

Athens County

Ohio. The work of excavation was

accomplished under

the direction of the writer, with the

assistance of Mr.

Robert Goslin.

The mound was at the western edge of

the village,

which is about three and one-half miles

north and slight-

ly west of the city of Athens.

Excavations occupied a

five-week period during July and

August, 1930. The

mound was originally some 25 or 30 feet

in height but

at the time excavations were commenced about

three-

quarters of it had been removed and

spread as top-soil

in neighboring gardens, a process which

had been going

on for many years, beginning apparently

with the level-

ing of the mound about 40 feet in from

the southern

edge to accommodate a section line

road.

In 1930 the mound presented a ragged

appearance.

A semi-circular segment stood up to a

height of about

20 feet on the north and east sides,

and numerous holes

had been dug in the perpendicular face

of this segment,

mostly near its top. Extending westward

from this

face to the edge of the mound, and

southward to the

road, where the material had been

removed to the ground

(369)

370 Ohio Arch. and Hist.

Society Publications

level, there was a table-like elevation

representing the

lowest point to which removal of dirt

for gardens had

reached. The surface of this area was

about six feet

above the ground level, and therefore

about 11 feet

above the bottom of the tomb at the

center. Excava-

tion was begun at the western edge and

continued east-

ward through this remaining base,

presenting a vertical

face only six feet in height until the

semi-circular seg-

ment on the east was reached, where the

face of exca-

vation attained a height of 21 feet.

Fortunately the

tomb and its contiguous structures were

at the center

of the mound and the tearing down of

the mound

previous to 1930 destroyed nothing of

value. Inasmuch

as a great part had been carried away,

no attempt was

made to restore the mound after its

complete excavation.

Excavation was in fact greatly aided,

and the expense

of the operation lessened, by shoveling

the dirt into

trucks in which it was carried away to

enrich the sur-

rounding gardens.

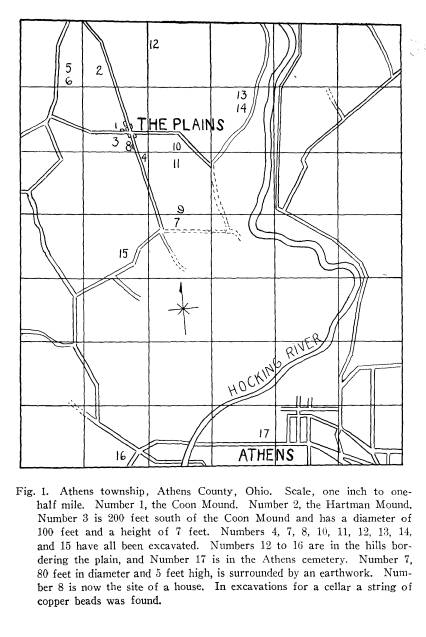

GENERAL FEATURES OF THE COON MOUND

The Coon Mound was one of a number of

mounds

and other earthworks situated on a

level plain in the

northwestern part of Athens County,

west and south

of Hocking River (See Figure 1). This

plain is about

two miles long north and south and a

mile in greatest

width near its center. It is nearly

surrounded by hills

which rise to a height of 200 feet

above the level of

the plain, which is about 65 feet

higher than the valley

flats of Hocking River. On the

northwest and south-

east the two ends of this level area

are gullied by small

|

Coon Mound--Analysis of Adena Culture 371 |

|

|

372 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

post-glacial streams where there is a

gradual descent

into the river valley. This topography

is very similar

to that at Chillicothe, where in

prehistoric times a plain

considerably larger was selected for

the site of some

30 or 40 mounds and inclosures.

In the Archaeological Atlas of Ohio

there are re-

corded 25 earthworks and a village site

within a mile

and a half of the village of The

Plains, ten of which were

in the surrounding hills. Eleven of

these are circular

and square inclosures while the rest

are burial mounds.

In a survey of the same general area

during excava-

tion of the Coon Mound only 17 mounds

and one earth-

work were found (Figure 1). Eleven of

these are

on the level plain within

three-quarters of a mile from

the Coon Mound. Half a mile north of

this mound on

the farm of Mr. Gilbert Hartman is the

largest mound

of the entire group (Number 2 in Figure

1), measuring

37 feet in height, with a diameter not

greatly exceeding

that of the Coon Mound. The latter,

second in size,

was identical with the Hartman mound in

general ap-

pearance.

The north and south diameter of the

Coon Mound

was 158 feet; east and west, 132 feet.

These measure-

ments are not in agreement with those

given by An-

drews in Report of Exploration, who

examined the

mound before the year 1876. According

to Andrews the

mound was "about thirty feet high

and with a diameter

of base of one hundred and fourteen

feet." Andrews'

measurement was probaby taken from the

north edge

of the mound to the north border of the

road which

had been cut through the south side of

the mound. This

Coon Mound--Analysis of Adena

Culture 373

distance would be very close to 114

feet. The north and

south diameter secured during

excavation of the mound,

158 feet, was taken from the north edge

to the southern

border of a semi-circular elevation 18

inches in height

immediately south of the road which was

regarded as

the remnant of the southern border of

the mound.

Andrews, examining the face of the

vertical cut

exposed by the road on the south edge

of the mound,

describes a mottled appearance for the

clays, light loam,

gravelly and black earth of which the

mound was com-

posed. This description tallies with

the findings of the

Society's excavations in 1930. No

burials nor struc-

tures of any kind were found above the

floor of the

mound, and all inquiry failed to

disclose that anything

of that nature was found by those who

carried the earth

of the mound away for gardens. The

mottled appear-

ance of the materials of the mound

described by An-

drews is a familiar phenomenon of most

of the larger

burial mounds which have been

excavated. These

patches, varying in color from light

brown or yellow to

black, doubtless represent single

baskets full of earth

deposited by the aboriginal builders.

The material of the upper portion of

the mound was

very rich in organic content and was

unquestionably re-

moved from the surface and to a depth

of from six to

12 inches in the immediate vicinity. No

depressions in

the surrounding surface indicated that

the builders had

gone beneath the hardpan to secure

material for the

mound. The top soil in the vicinity of

the mound is

light in color and somewhat deficient

from the agricul-

tural point of view, quite different

from the earth of

|

374 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications the mound, which appears to have been gathered to some extent from an occupation site. On the southwest side Andrews found large quantities of "kitchen refuse." This, he reports, was made up of "blackened soil, ashes, charcoal, bits of bone (some burned and some not), |

|

|

|

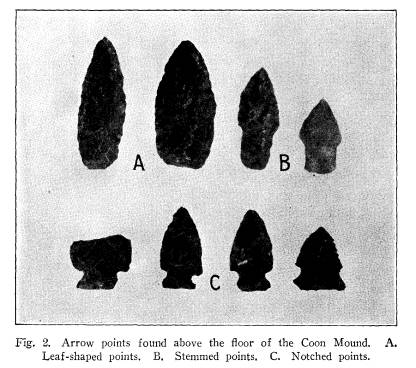

fresh-water shells, land snails, bits of broken pottery and of broken flints, and small stones, generally burnt, such as might be in fires built on the ground." While the Society's explorations confirm Andrews' estimate of the richness of the soil, very little in the way of "kitchen refuse" was found. The only artifacts found |

|

Coon Mound--Analysis of Adena Culture 375 in the upper portion above the floor were the arrow- points shown in Figure 2. About a dozen fragments of animal bones were encountered in addition to a simi- lar quantity of fragments of calcined human bone. Cer- tainly the amount of refuse material found would not indicate a village site of any great size. |

|

|

|

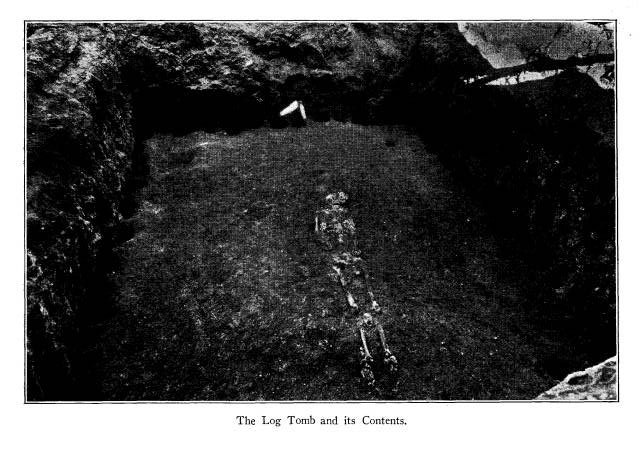

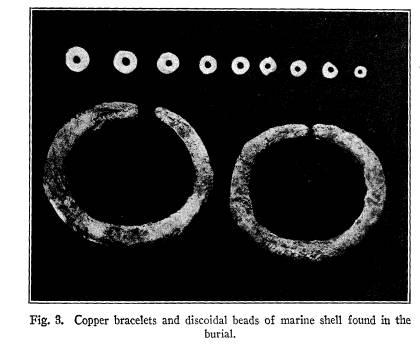

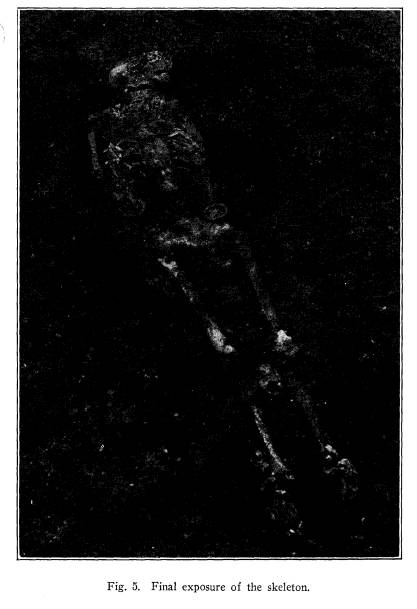

CONTENTS OF THE MOUND. The Burial. The Coon Mound contained the re- mains of a single individual in a rectangular sub-floor tomb at the center (See Frontispiece). The skeleton was that of a male who at the time of his death was from 25 to 35 years of age. The only artifacts which |

376 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

accompanied the skeleton were two

copper bracelets,

one around each wrist, about 260

disc-shaped shell

beads (Figure 3) which had been worn in

five strands

at the forehead and neck, and the clay

object between

the upper ends of the tibiae (See

Figure 5). This ob-

ject, consisting apparently of unbaked

yellow clay, is

four inches long, two inches in width

and thickness. A

hollow interior contains a yellow powder

which adheres

to the sides of the cavity, and a small

quantity of black

clay in spherical lumps about one

thirty-second of an

inch in diameter. Chemical and

mineralogical analysis

revealed a basic sulphate of iron such

as results from

the decomposition of pyrite, a mineral

resembling gold

in its lustre and color. One or more

lumps of pyrite,

very likely mistaken for gold, appear

therefore to have

formed, in the minds of the builders of

the mound, the

main mortuary offering. In the

immediate vicinity of

this mass of disintegrated pyrite the

upper ends of both

tibiae had entirely disappeared (See

Figure 5), a cir-

cumstance which is explained by the

well-known capac-

ity of pyrite for attacking adjacent

materials.

The skeleton was extended on the back,

head to the

east. The arm-bones lay parallel to the

axis of the

skeleton and the right hand lay over

the right side of

the pelvis while the bones of the left

hand lay beneath

the edge of the left side of the

pelvis. The skull, lying

face up, had been badly crushed by the

weight of the

earth. The total length of the

skeleton, measured in

situ, was six feet and two inches, representing a devia-

tion of probably not more than two

inches from the

height of this individual during life.

|

Coon Mound--Analysis of Adena Culture 377 The skeleton lay on the floor of the tomb, ten inches south of the center. The skull was 64 inches from the east wall while the tips of the foot bones were 33 inches from the west wall. It was therefore not in the exact center of the tomb. Beneath the skeleton was a layer of |

|

|

|

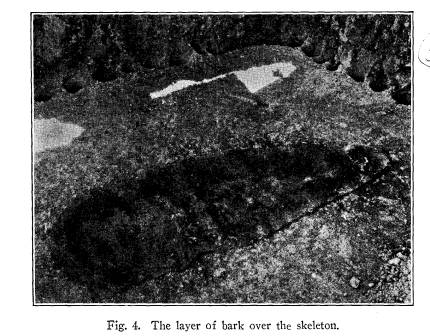

bark about half an inch in thickness, which extended out beyond its outline from six to ten inches. Another bark covering, 87 inches long and 30 inches wide, lay directly over the skeleton (Figure 4). This layer varied in thickness from one to three-quarters of an inch. Like the layer of bark beneath, it was reddish brown in some places and black in others. The upper surface of the bark over the skeleton was corrugated, parallel ridges |

|

378 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications |

|

|

Coon Mound--Analysis of Adena

Culture 379

running north and south in a half-inch

relief and about

twice that distance apart. In addition

to these ridges

there were protuberances corresponding

to bones of the

skeleton directly beneath. At the edges

of the skeleton

the upper and lower layers of bark came

together and

their combined thickness was not at any

point greater

than an inch and a half.

None of the bones of the skeleton were

in a state

of preservation which would permit

accurate measure-

ments. The bones of the feet and legs,

and part of

the right humerus, had retained their

form sufficiently

to stand out above the gravel floor.

These, with the

teeth and fragments of the jaws, were

the only ones re-

moved.

Lying directly on the upper layer of

bark and co-

extensive with it, was a stratum of

firm yellow clay

averaging an inch in thickness. Above

this was the

mixture of black and coarse yellow

earth, the same mate-

rial as that constituting the bulk of the

mound.

The Tomb. The tomb was rectangular with the

long axis running about five degrees

north of east. The

length was 15 feet; width 12 feet and

eight inches

(Figure 6). The depth beneath the

original level of the

ground was about 60 inches, but the southwest

corner

was eight inches lower. The material of

the floor of

the tomb was heavy gravel mixed with

reddish clay.

The surface of the floor was black, a

color due possibly

to the action of fire. This deposit of

mixed gravel and

clay forms a hardpan beginning at a

depth of two to

three feet beneath the surface on the

site of the mound

and for some distance around it.

380

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

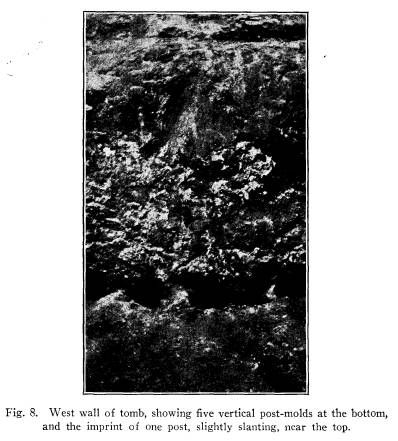

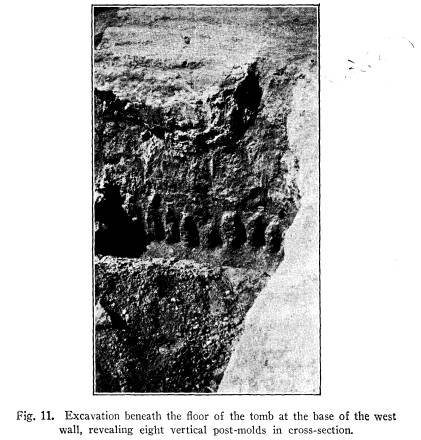

At the bottom of the vertical walls of

the tomb were

67 holes which were originally occupied

by vertical posts

(Figure 6 and Frontispiece). These

holes varied in

diameter from five to eight inches, and

from center to

center the distance was from six to 23

inches. In depth

beneath the floor of the tomb they

varied from 21 to 27

inches, and at the bottom the holes

were flat instead of

coming to a point. Instead of driving

the original posts

into the floor of the tomb with heavy

stones, the builders

must have dug out a trench about a foot

wide around

the base of the vertical walls, placed

the posts in position

and then filled in around them. The

gravel and clay

beneath the floor of the tomb would

have made it very

difficult if not impossible for them to

dig a hole six inches

in diameter to a depth of two feet

(Figure 11). After

removal of the skeleton excavation was

carried to a

depth of three feet directly beneath it

and the resistance

of the clay and gravel mixture was such

as to necessi-

tate the use of a miner's pick.

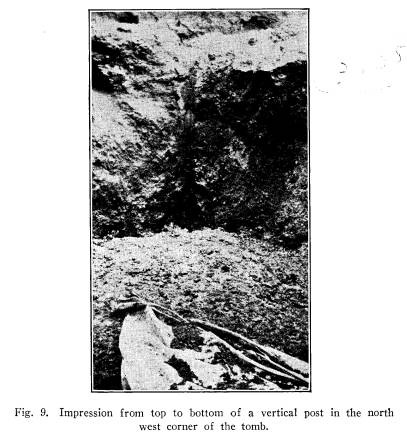

The impressions of many of these 67

vertical posts,

particularly of those in the corners,

were traceable in

the clay of the side walls to the top

(Figures 8 and

9). Most of these post-molds in the

walls were vertical,

but a few were at a slant, probably

indicating an acci-

dental deviation due to pressure, from

an original up-

right position.

Inset diagonally about 30 inches from

each corner

of the tomb was a post-mold, of the

same size and depth

as those around the base of the walls.

While the posts

which originally stood in these four

holes probably were

as high as those around the walls of

the tomb, their im-

|

Coon Mound--Analysis of Adena Culture 381 pressions had not been preserved in the soft earth which filled the tomb. |

|

|

|

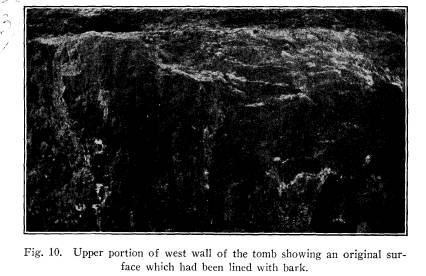

The walls of the tomb were lined with a coating of gray clay about six inches thick. This coating also |

|

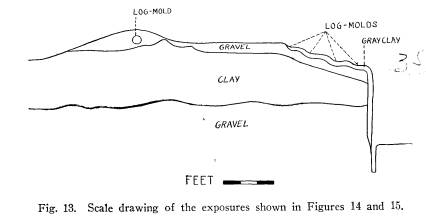

382 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications underlaid the horizontal log-molds which bordered the tomb on the outside (Figures 12 and 13). Several areas up to a yard in diameter on the vertical walls were very |

|

|

|

smooth, as is shown in Figure 10, while in other areas fine layers of the mottled clay with which the tomb had been filled adhered to the surface of the walls. These smooth surfaces were probably made by the inner sides |

|

Coon Mound--Analysis of Adena Culture 383 of the layers of bark with which the walls were lined, and which were no doubt held in place by the 67 ver- tical posts. No impressions of the outer surfaces of |

|

|

|

bark layers were found on the walls, and the material filling the tomb was too loose and soft to preserve them. The entire surfaces of all four walls however were cov- ered with streaks and patches of red and black, with |

|

384 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications spots of a white, ash-like substance (Figure 10). The red and white substances were powdery and with small doubt were formed by the disintegration of bark. The black may have been caused by heat. It turned red upon being crumbled between the fingers. In large areas the gray clay of the walls was only half an inch in thick- ness over a layer of yellow clay four or five inches thick. |

|

|

|

In the smooth areas where the original surface of the walls was exposed, the clay was much harder at the surface than an inch or two beneath. This circum- stance, taken together with the presence of the black powder which exhibited a red stain, may be taken as presumptive evidence that a large fire was built in the tomb before the burial was made. In agreement with this the surface of the floor of the tomb was black for the most part, the natural red of the gravel and clay |

|

Coon Mound--Analysis of Adena Culture 385 beneath showing up only in small spots. Of the purpose of this fire, nothing can be said, and if there was a fire, resulting debris such as charred branches was com- pletely cleared from the tomb. |

|

|

|

The earth filling the tomb, similar in consistency and color to that forming the bulk of the mound, was loose and soft. This condition prevailed not only in all parts |

386 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

of the tomb itself but for a distance

of three or four

feet above the top of the side walls.

Elsewhere above

the floor of the mound (at the original

level of the

ground) the mottled clay was very solid

and continual

use of mattocks was necessary to break

it up. Mattocks

were not used in removing earth from

the tomb. De-

spite the fact that there had been no

rain for at least

two months prior to these excavations,

the clay of the

lower three feet of the tomb was very

damp, and con-

tinual tramping over the same area

produced a thick

paste. The presence of water may of

course be ex-

plained by pointing out that the inner

slope of the gravel

circle around the tomb (Figures 12 and

16) acted as a

fifty-foot catch basin for all the

descending moisture

in the mound, draining it into the tomb

where it was

brought to a stop by the floor of

gravel and clay. This

moisture may account in some degree for

the softness

of the materials filling the tomb. But

it cannot explain

the looseness of the earth four feet

above the top of the

tomb, nor can it be held responsible

for the existence

of hollow spaces as much as three

inches in diameter

throughout the earth with which the

tomb was filled.

The collapse of a roof of logs,

precipitating the earth

overhead down into the hollow

sepulchre, best accounts

for these conditions. What was left of

this roof, if

our surmise be correct, was found eight

inches above

the floor of the tomb in the form of a

number of log-

molds accompanied by streaks of red and

white powder.

These molds extended the length and

breadth of the

tomb at this level and most of them ran

parallel north

and south while the remainder extended

in all directions

Coon Mound--Analysis of Adena

Culture 387

except the vertical. The soft

honeycombed earth would

not have preserved the mold of a log in

vertical posi-

tion. All that remained of these

roof-logs in the loose

earth were flat streaks of

disintegrated wood that ad-

mitted of no accurate measurement. The

earth around

them filled in their molds as fast as

they decayed. The

six or eight inches of earth between

this stratum of logs

and the floor of the tomb probably sifted

through the

roof before the cave-in.

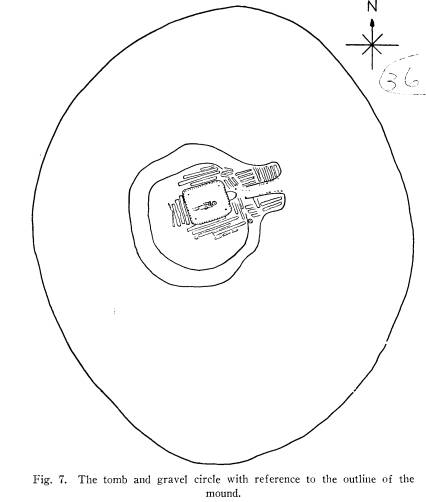

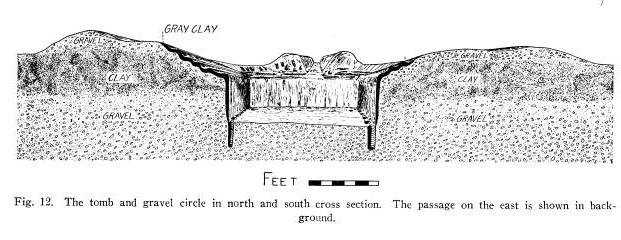

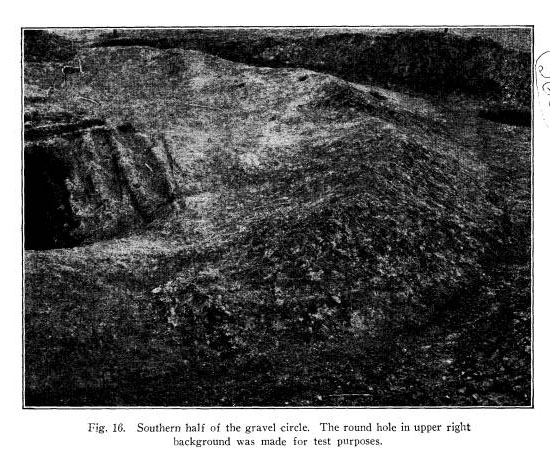

The Gravel Circle. Beneath that portion of the

mound above the original surface lay

two different kinds

of earth in horizontal strata. At the

floor of the mound

and to a depth of about three feet was

a deposit of

blue-gray clay, somewhat darker at the

top than lower

down. Beneath this was a deposit of

gravel and red-

dish clay of undetermined thickness

(Figure 12). Both

deposits were natural and extended

beyond the site of

the mound.

Those who excavated the tomb utilized

the earth

which they removed to form a raised

circle around it

(Figure 16). This circle averaged two

feet in height

and was continuous except for the

opening on the east

which appears to have been used as an

entrance (Figure

19). The relative positions of the two

different kinds

of earth composing the circle

corresponded to the order

in which they were thrown out of the

tomb. In the

process the blue-gray clay was thrown

out first and

spread around the tomb to form the base

of the earthen

circle. At the bottom of the deposit of

blue-gray clay

the top of the gravel and clay hardpan

was encountered,

and this material was thrown out and

carefully spread

|

Coon Mound--Analysis of Adcna Culture 389 over the base into a symmetrically rounded wall whose crest was from 12 to 15 feet from the edges of the tomb. The inner slope of the wall was rather abrupt for a distance of three feet from the crest, from which point to the edges of the horizontal log molds bordering the tomb the slope was scarcely noticeable. |

|

|

|

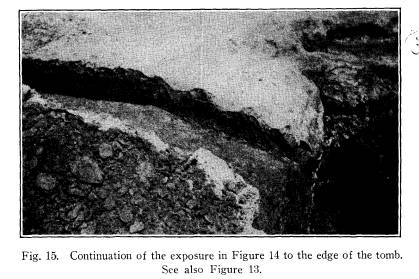

The surface of the gravel circle was as smooth as the coarse material of which it was made would permit. Like the surface of the floor of the tomb, but to a lesser extent, it was covered with small and continuous patches of black, giving the whole a mottled red and black ap- pearance. The black may have been the result of fire. The surface of the gravel circle, and to a depth of two inches, was very hard, exceptionally difficult to break up with a pick. Trenches were cut through the circle from one edge to the other at several points, down to the blue- gray clay forming the floor of the mound. One of these trenches, exposing the strata in cross-section, is shown in Figures 14 and 15. In Figure 14 the outer portion of |

|

390 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications the trench, that exposing the wall proper, is shown. Fig- ure 15 is the continuation of the same trench showing the level part of the gravel circle and the horizontal log- molds (in cross-section) on the incline dipping to the edge of the tomb. Figure 13 is a scale drawing of the entire face of the trench, from the outer edge of the gravel circle to and including the wall of the tomb down to the base of one of the vertical post-molds. The mold of the horizontal log about eight inches beneath the crest |

|

|

|

of the circle (Figures 13 and 14) extended inward from the face of the trench three feet. Similar molds were found in other trenches through the wall of the circle, and in the north wall of the passageway (Figure 21). Aside from the possibility of a ceremonial function these logs, perhaps left over after the timber construction in |

|

Coon Mound--Analysis of Adena Culture 391 the tomb was finished, may have been used simply as filling. The surface of the floor of the mound directly be- neath the gravel circle contained impressions, and often the disintegrated remains, of leaves, twigs and grasses in profusion. Among these impressions were occasional very small flakes of mica not more than an eighth of an |

|

|

|

inch across. Beyond the edge of the gravel circle the surface of the floor was almost entirely devoid of such materials. The floor itself had no well-packed stratum of muck such as is usually found in mounds of the Hope- well type, and represented merely the original surface of the ground before the mound was erected, unmodified except perhaps for some levelling; apparently however it had been swept clear of the debris of the forest while beneath the gravel circle this debris remained untouched. |

392

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

Aside from the possibility of a

ceremonial purpose, two

possibilities explain this situation.

The twigs, grasses,

leaves and so forth, cleared from the

floor of the mound,

were deposited in the area to be

covered by the gravel

circle as the easiest way in which this

material could

be disposed of; or the debris on the

floor beyond the

borders of the gravel circle was swept

toward the out-

side of the area to be occupied by the

mound, that on

the site of the gravel circle being

left in place because

it was to be covered up. Of course the

ceremonial ex-

planation offers a third possibility,

its plausibility being

somewhat heightened by the presence of

small flakes of

mica, which were not found elsewhere in

the mound.

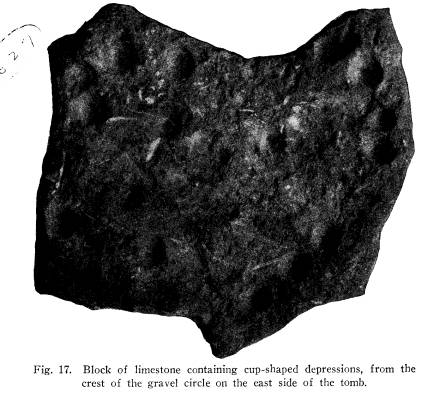

A large square block of limestone

containing 16

pits, shown in Figure 17, lay upon the

crest of the

gravel circle east of the tomb near the

point where the

end of the circle expanded into the

south wall of the

passage (Figure 6). This stone is 16 by

12 inches, and

eight inches thick. The side opposite

that in the illus-

tration is very uneven. Pieces of

another stone, the

largest fragment containing three pits,

lay in one of

the parallel horizontal log-molds to the

south of the

southwest corner of the tomb (See

Figure 6).

The Horizontal Log-molds. The

impressions of

horizontal logs paralleled each of the

four sides of the

tomb (Figures 6, 13, 15, 18). On the

north there were

four of these impressions, only two of

which extended

the length of the tomb. These two

log-molds were

about a foot wide and from six to eight

inches deep.

Four log-molds of similar dimensions

paralleled the

southern wall of the tomb; there were

three on the west,

|

394 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications with the molds of two crossed poles adjacent to the outer log-mold. On the east there were two log-molds about 20 feet in length and eight inches in width, the original timbers of which extended either under or over a rounded depression at the edge of the tomb (a, in Figure |

|

|

|

6), or it is possible that the two logs terminated at the sides of this depression. To the east of this depression were the molds of other shorter logs, extending to the base of the west end of the passageway (Figure 20). These horizontal log-molds were in an inclined position, |

|

Coon Mound--Analysis of Adena Culture 395 the slope beginning at the inner edge of the level por- tion of the gravel circle and extending to the tops of the perpendicular walls of the tomb, which were about 18 inches beneath the floor of the mound. Thus at a certain stage in its construction the tomb presented the appearance of a square funnel-shaped depression with |

|

|

|

rounded corners, the lower three feet of whose sides were perpendicular. Later about a foot of the slanting sides of this funnel were overlaid with the gravel thrown out from the tomb proper, this gravel forming a down- ward extension of the gravel constituting the circular wall. Next, the perpendicular sides of the tomb and the slanting sides of the funnel were overlaid with a coating |

|

Coon Mound--Analysis of Adena Culture 397 of gray clay about six inches thick. Upon this coating were laid the horizontal logs along the slanting sides from the inner edges of the wall to the tops of the perpendicular sides of the tomb (Figure 12). In some of these horizontal log-molds there were holes an inch or two in diameter and about a foot in depth, left by vertical stakes. Layers of white powdery, ash-like re- |

|

|

|

mains of the disintegrated logs, of varying thicknesses up to a quarter of an inch, were distributed in irregular streaks and patches in and between the log-molds. The Passage. On the east the two ends of the gravel circle turned abruptly eastward to form the par- allel walls of a narrow corridor 12 to 15 feet in length and about four feet wide at the floor level (Figures 6, |

398

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

19). This corridor had all the

appearance of a pass-

ageway through which the tomb was

approached and

entered.

The two walls stood up from the floor

of the mound

from three to four feet; that is, the

topmost horizontal

log-molds found upon them were at this

level. In Fig-

ure 21 the strata of the two walls

about at the center are

shown in transverse cross-section. The

gravel base of

these walls (C in Figure 21) is continuous

with the

gravel of the circle around the tomb,

descending to the

floor-level at the east ends of the

walls. Overlying the

gravel of each wall to a height of a

foot and a half

above it were mottled blue, gray and

yellow clays, re-

sembling closely the materials in the

body of the mound.

On the flat tops of the walls, five or

six feet in width,

were numerous log-molds from six inches

to a foot or

more in width, lying in parallel

horizontal rows in

groups at right angles to one another

(Figures 19, 20).

Some of the log molds disposed at right

angles to the

length of the walls extended down the

sloping inner

sides into round depressions four or

five inches in depth

(Figure 19).

The floor of this passageway, at the

general level of

the floor of the mound, consisted of

gravel and clay

similar to that making up the base of

the two walls, as

is shown in Figure 21. Like the floor

of the tomb,

the surface of this gravel and clay was

very hard

and covered with irregular patches of

black. The top

of the underlying stratum of dark clay

(D in Figure 21)

contained the imprint of grasses,

leaves, twigs and so

forth. Lying above the gravel floor was

a deposit of

|

Coon Mound--Analysis of Adena Culture 399 gray clay from one to six inches thick, containing the impressions of the ends of posts or logs, resembling post-molds in appearance, along both sides of the pass- ageway at the bottoms of the interior slopes of the two walls (Figure 19). Some of these round depressions reached to the surface of the gravel floor while others did not. Many of them were not more than an inch or two in depth. This layer of gray clay above the gravel floor was no more solid in texture than the mottled clay directly above, forming the upper part of the mound |

|

|

|

proper, and it bore no signs of fire. The semi-oval area between the west end of the passageway and the east wall of the tomb (this is shown in the background in Figure 19, and on the floor-plan in Figure 6) was very firm in texture on the surface and for two inches be- neath, as if the clay had been packed solid by the pres- sure of many feet. Such pressure would have left no noticeable sign on the surface of the almost brick-hard gravel and clay floor of the passageway, upon which those who passed between the two walls probably walked. The inner edges of the two walls of the passageway |

400

Ohio. Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

were not parallel throughout their

entire length, as a

glance at Figures 6 and 19 will show.

For a distance

of six and one-half feet from the west

end the corridor

is from 36 to 40 inches in width,

widening eastward

from that point to form an outer

opening about seven

feet wide. Three and one-half feet

above the floor a

single log-mold extended northeast from

the end of the

south wall, apparently turning the

entrance of the cor-

ridor to the north. This log-mold,

shown in the fore-

ground in Figure 19, rested upon dark

clay similar to

that forming the upper stratum of the

walls of the corri-

dor, but the clay in this instance did

not rest upon the

gravel, which terminated at the ends of

the two walls.

The mold was poorly defined and

isolated by two feet

from the end of the south wall. For

this reason it was

not included in the floor-plan in

Figure 6.

Reconstruction. The

condition of the tomb and its

contiguous structures as they were

revealed by excava-

tion have now been described in detail

and it is obvious

that the picture obtained so far

represents but a momen-

tary condition in time and space. With

a difference of

five hundred years in either direction

the picture would

have been quite another one; backward,

more complete,

forward, more fragmentary. The picture

obtained in

1930 was made by following out the

various strata, and

differentiating between them on the

basis of their rela-

tive hardness, color and consistency.

This picture deals

mostly with flat impressions and

cavities of objects

which once were solid and

three-dimensional, and which

in some instances formerly occupied

different positions

from those in which their molds were

finally uncovered.

402

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

Our picture is but a rough outline

drawing of certain

portions of an original structure of logs and bark which

was covered with earth. The missing

portions may be

sketched into the picture by

interpretation of strata, by

inferences based upon our own knowledge

of construc-

tion in wood and by consideration of

the purposes and

aims of the builders of this burial

mound. In this re-

construction an attempt will be made to

show that the

tomb and the passageway were roofed,

and to explain

the function of the timbers which

originally occupied

the horizontal log-molds around the

tomb. Interpreta-

tion must be made with two

considerations in mind.

First, this subterranean structure was

built to receive

the remains of the dead, and many of

its features sym-

bolized to the builders certain of

their religious or magi-

cal beliefs bearing upon the phenomenon

of death. The

more apparent of these symbolical

aspects of the tomb

and its parts are its orientation

approximately with the

cardinal points, the situation of the

passageway on the

east and the position of the skull of

the burial to the

same direction, the gravel circle

enclosing the tomb and,

perhaps, the fact that it was beneath

the original level of

the ground, for this structure could

have been erected on

the surface and still have been

subterranean, some fifteen

or twenty feet beneath the top of the

mound. While it

is easy and attractive to give a

utilitarian interpretation

to the various logs and posts which

left their unmistaka-

ble impressions, some of these

features, for example the

horizontal logs on the four sides, may

have been so

placed entirely for symbolical or

ceremonial reasons. In

fact it is entirely possible that every

post, log and layer

Coon Mound--Analysis of Adena

Culture 403

of bark which served a practical

purpose in the construc-

tion of the tomb symbolized at the same

time some as-

pect of those special procedures which

primitive people

build up around the phenomenon of

death.

Second, if our assumption of a roof is

correct, the

builders found themselves confronted

with problems of

a highly practical nature. The

positions of some of the

timbers at least were determined by

utilitarian consid-

erations. The roof must be supported and

some pro-

vision was necessary against lateral

pressure of the

earth of the mound against the sides of

the tomb if they

projected above the floor of the mound.

Correct recon-

struction of the tomb therefore depends

upon the ex-

pertness of the builders in solving

these problems. A

faulty solution on their part would

result in the placing

of timbers in positions which would

prohibit a reasona-

ble utilitarian interpretation. In

reconstructing the orig-

inal appearance of the tomb it

therefore becomes in-

creasingly difficult for us to

distinguish between the

utilitarian and the symbolical, and the

reconstruction in

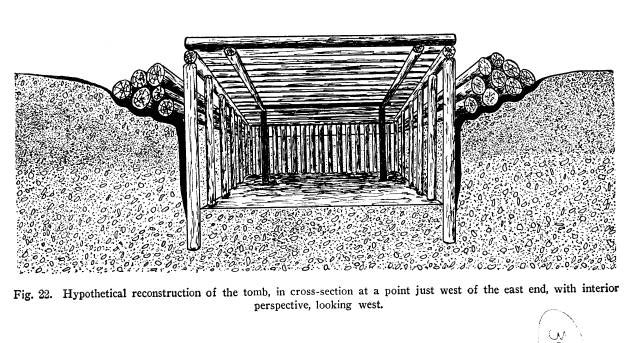

Figure 22 is admittedly hypothetical.

The following features strongly suggest

that the

tomb was originally roofed: the four

inset post-molds in

the floor, the looseness of the earth

within and above

the tomb, and the presence of

disintegrated timbers eight

inches above the floor. The structure

and purpose of

the tomb may be taken as further

evidence. Keeping

strictly within the limits of the known

facts, the sym-

metry of the tomb and the vertical

post-molds in the

floor indicate a comparatively

complicated architectural

structure and without much doubt the

dwelling-houses

404

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

of the builders offered the plan and

pattern for this

house of the dead. Presumably their

houses were roofed

and if the tomb and the entrance

faithfully reproduce

their features they also were covered

in some manner.

The practice of contructing the

sepulchre upon the plan

of the dwelling house is not unknown

among prehistoric

peoples. Dwelling houses have been

reconstructed from

wooden grave chambers in Europe, belonging

to the

Hallstatt Period of the Iron Age, and

small clay urns,

receptacles for the ashes of the dead,

were modelled in

imitation of the dwelling huts of the

time (See Prehis-

toric Ancestors, pp. 291, 296).

It is not necessary to suppose that the

entire mound

and the tomb were erected during one

continuous period.

It is entirely possible that a

considerable interval of

time elapsed between the completion of

the tomb and the

erection of the mound above and around

it; that, in

other words, the interior of the tomb

remained accessible

from the outside, through the

passageway on the east,

during a period of mourning. It is

equally possible

that the passageway, roofed and sided

with timbers, re-

mained open after completion of the mound,

or at least

that such was the intention of the

builders. A roof over

the tomb could have served one or both

of two purposes;

to protect the interment from the

elements during the

period of mourning before the mound was

thrown up,

and to protect the interment and

whatever perishable

objects may have accompanied it from

the weight of the

earth after erection of the mound.

There is no way to

estimate the time occupied in throwing

the earth over

the tomb to a height of thirty feet.

But with the ac-

Coon Mound--Analysis of Adena

Culture 405

cumulation of weight upon the roof it

may have col-

lapsed, and if so those engaged in the

work were proba-

bly aware of it.

Several equally plausible

reconstructions of the eleva-

tion of the tomb could be made, but the

available evidence

points to a structure resembling that

in Figure 22. This

drawing is made from the point of view

of an observer

standing at the east end of a vertical

cut revealing the

interior of the tomb in cross-section.

The vertical posts

lining the walls of the tomb were not

more than two

feet apart. In the drawing they are

represented at a

greater distance from one another as an

aid to the

graphic presentation of the structure

of the tomb in its

relationship to the surrounding

horizontal timbers at the

original level of the ground. In this

reconstruction the

known facts have admittedly been

transcended, in an

effort to explain the circumstances in

the light of our

own knowledge of the stresses and

strains involved in

the construction of underground wooden

chambers.

The roof is placed at a distance of

three or four feet

above the tops of the side walls, or

eight or nine feet

above the floor of the tomb. This

position has been de-

termined in relation to the attempt to

explain the mean-

ing of the horizontal log-molds as the

remains of logs

which had a mechanical significance in

the structure of

the tomb. Further, this interpretation

leaves a clearance

or three or four feet at the east end

for entrance into the

tomb proper from the passageway. The

height of the 67

vertical post-molds outlining the floor

of the tomb, which

with the four inset post-molds

represent the remains of

uprights supporting the roof, could not

be determined.

406

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

The 67 side-posts certainly extended to

the tops of the

tomb walls, leaving their impressions

in some instances

from top to bottom (Figure 9). Streaks

of disinte-

grated wood which may have been the

tops of these ver-

tical posts were found at a distance of

three or four feet

above the walls of the tomb in the

soft, honeycombed

earth of that area, but they could not

be traced to the

impressions in the side walls with any

certainty. It

should be noted that a cave-in would

completely destroy

the alignment of vertical post-molds.

In figure 22 the horizontal log-molds

have been in-

terpreted as the bases of piles of

logs, the purposes of

which were to absorb the weight of the

earth around the

sides of the tomb, a function which

they would serve

efficiently only by being piled

pyramidally, without touch-

ing the upright posts supporting the

roof; the earth oc-

cupying the intervening space being

prevented from fall-

ing through the cracks between the

upright posts by

extension of the bark lining of the

wall to the roof.

Small stake-holes in the edges of some

of these hori-

zontal log-molds apparently represent

an attempt to hold

the piles of logs in place and to keep their

weight, in-

creased by the lateral pressure of the

earth of the mound,

from crushing the side-walls. It is

possible that the

inner logs of the horizontal piles were

placed close

against the upright posts to a height

equal to that of the

roof. The pressure of these logs would

have been con-

siderable however, probably as great as

the earth would

have exerted had there been no

horizontal timbers in

these positions.

The bottom logs of these horizontal,

pyramided

Coon Mound--Analysis of Adena

Culture 407

piles, rest upon an incline. A glance

at Figure 12 will

show that this incline starts above the

original ground

level, on the inner slope of the gravel

wall, and descends

to a depth of from one to two feet

beneath the original

ground level, at which point is the

vertical drop of the

side walls. The structural significance

of this incline

might be regarded as a further attempt

to lessen the

weight of the earth against the vertical

posts, an attempt

however, which was not effectual.

The three girders upon which the

timbers of the roof

are supported are shown resting on the

tops of the ver-

tical posts. There was of course

nothing to show the

manner in which these girders were fastened

to the tops

of the posts. The latter, including the

four inset posts,

may have been forked at the top, and

the girders tied in

firmly with thongs.

The log-molds on the walls of the

passageway are

easier to interpret. There is strong

evidence here of

a cave-in, as in the tomb, but the lack

of vertical post-

molds of any depth in the floor of the

passageway points

to simplicity in construction.

Apparently this corridor

had a roof of logs and bark, the ends

of the logs resting

upon the tops of the two walls, giving

a height to the

passageway of only three feet. The

depressions at the

bases of the walls and the log-molds

down the slopes of

their inner sides may be explained by

supposing that

when the cave-in occurred the logs of

the roof were

broken at center, and at the inner

edges of the tops of

the walls. The pressure of the earth

forced the ends of

the logs at the broken center, down

upon the gravel floor,

leaving their round, more or less

vertical impressions at

the sides of the walls (Figure 19).

408

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

CONCLUSION

The Coon Mound exhibits the

characteristic features

of the Adena culture in its purest

form. This culture is

described in the final chapter of this

report, and a brief

enumeration of the main elements will

suffice for the

present purpose. These are as follows:

conical mounds,

sub-floor burial as well as burial in

the upper part of

mounds, sepulchres of various sizes

built of logs, use of

copper mainly for ornamental rather

than for practical

purposes, certain types of slate or

limestone gorgets, to-

bacco pipes of the simple tubular type,

and flint points

of the unnotched leaf-shaped, and the

square-stemmed

types. The name of this culture is

taken from the Adena

Mound, in Chillicothe, Ross County,

which was exca-

vated by the Society in 1901. Nearly

all of the features

exhibited by the Coon Mound were found

also in the

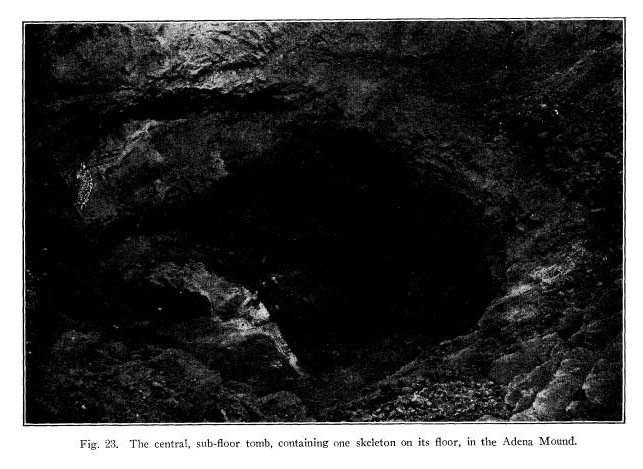

Adena Mound. The sub-floor tombs at the

center of

both mounds were of approximately the

same size, and

both were rectangular; each contained

on its floor a

skeleton extended at full length, whose

lower leg bones

were painted with red ochre (See Figure

23). In

the Adena Mound the clay and gravel

from the tomb

had been used in forming a wall at the

ground level

which, in the cross-section shown in

Excavations of the

Adena Mound in Figure 19, was of about

the same size

and contour as that of the wall in the

Coon Mound.

While extreme caution is necessary in

making deduc-

tions regarding social status from the

manner in which

the dead are buried, it seems worth

while in the present

instance to suggest that the individual

entombed in the

Coon Mound was a person of considerable

importance.

410

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

The erection of a mound of this size

over the remains

of a single individual is very

suggestive and the presence

of red pigment on the tibia of the

skeleton is of further

significance. Captain Romans, who

travelled among the

Indians of the south before 1775, makes

the following

statement in regard to the burial

customs of the

Choctaw:

"As soon as the deceased is

departed, a stage is erected, and

the corpse is laid on it and covered

with a bear skin; if he be a

man of note, it is decorated, and the

poles painted red with

vermillion and bears oil . . . the head

being painted with ver-

million (after the flesh has been

scraped off) is with the rest

of the bones put into a neatly made

chest . . ." (A Con-

cise History of Florida, p. 88).

A number of other Adena type mounds

have con-

tained skeletons, parts of which were

painted with red

ochre. These include the Westenhaver

Mound and the

Fortney Mound, both excavated for the

Society, and a

mound in Illinois, numbered 53 in the

following study

of the Adena culture. In the latter

mound the red ochre

was on the skull only.

Taking into consideration the facts

that the Coon

Mound contained the remains of only one

individual, and

that an elaborately constructed tomb

was covered with

thirty feet of earth, the conclusion

that the individual

represented was a leader of some kind

among his people

is probably not far from the truth.

In age, the Coon Mound was prehistoric,

like all

mounds of the Adena type so far

excavated. Despite

certain contrasts with the Adena and

other mounds of

the same culture, nothing was found to

provide a basis

for conclusions as to their relative

age.

THE ADENA CULTURE

INTRODUCTORY NOTE

In the following study, sixty mounds

are classed as

Adena in type which have not heretofore

been included

in that culture. In this process the

zoological method of

identifying a species is used as far as

it is possible to do

so. According to that method of

classification and de-

scription the first specimen of the

type to be found and

described is the type specimen. While

the Grave Creek

Mound, number 55 herein, was partially

excavated in

1838, the Adena Mound, Number 1, was

the first one

belonging to the culture-type to be

completely excavated

and described, and it is therefore the

type specimen, a

fact already recognized by Shetrone in

Culture Problem

in Ohio (page 161). The inclusion of

other mounds un-

der the specific term Adena is

made herein upon the basis

of the characteristics exhibited by the

Adena Mound.

Shetrone has recognized five mounds as

Adena in

type in the paper just referred to.

These are the Adena,

Westenhaver, Grave Creek, Miamisburg

and Great

Smith mounds; the latter is number 58

in the present re-

port, and belongs to the Kanawha Valley

Group in West

Virginia. In addition the same

authority includes other

mounds of the Kanawha Valley, and of

the Scioto Val-

ley in Ohio, and since their excavation

the material from

Mounds 16, 29-32 and 35 has been on

exhibit in the

Museum of the Ohio State Archaeological

and His-

torical Society as Adena in type.

(411)

412 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

The distinctive traits of Adena culture

have been

listed by Shetrone (Op. cit., page 160)

as follows:

"Shapely, conical mounds, generally

single but sometimes oc-

curring in apparent series; mounds

unaccompanied by earth-

works; absence of pre-structures of

upright timbers, sites of

mounds unlevelled and showing no

evidence of previous use;

erection of mounds often begun by piling

logs and brush upon

the sites or bases; non-cremation of the

dead; burial made

upon the base line and throughout the

mounds, usually with an

important central grave below the base

line; sepulchres of logs

often used, particularly for the more

important burials. Materials

from distant sources, as with the

Hopewell culture proper, were

extensively used, but copper appears to

have been employed for

objects of ornamentation only, and

rarely if ever for utility im-

plements. Of the artifacts persistently

occurring there may be

mentioned copper bracelets and finger

rings; gorgets of the ex-

panded center and concave edge type;

tubular pipes; necklaces

of beads made from univalve shells; and

projectile points of flint

of the ovate unnotched and the stemmed

type."

This general statement is verified in

the following

tables, with the exception of cremation

and the occur-

rence of mounds within inclosures.

Thirty of the 350

or more burials in the seventy mounds

under discussion

were cremated, and six of these seventy

mounds were

either at the center or in a gateway of

an inclosure.

In the following tables the contents of

seventy

mounds, distributed in Ohio, Indiana,

Illinois, West

Virginia, Pennsylvania and Tennessee

are listed. Be-

ginning with the Adena Mound in Chillicothe,

Ohio, each

mound is numbered serially in

geographic progression.

There is a break between Mounds 47 and

48, since the

first 47 mounds are in Ohio and Mounds

48 to 52 are in

Indiana. Mound 53 is in Illinois, from

where the series

jumps again, to West Virginia,

beginning with Mound

54 and ending with Mound 69. Mound 56

is in Penn-

Coon Mound--Analysis of Adena

Culture 413

sylvania but is included in the West

Virginia series be-

cause of its proximity to Mounds 54 and

55. Mound 70

is in Tennessee.

While there is little question that the

Miamisburg

Mound, in Montgomery County, the

highest mound in

Ohio, is Adena in type, it has not been

included among

the seventy listed herein. Excavation

of a central shaft

in this mound in 1869 is reported in

Volume XIV of

the Publications of the Ohio State

Archaeological and

Historical Society, page 446, but not

enough was found

to enable its inclusion under the

method of identification

used in the present study.

In the Bibliography at the end of this

report are the

published references for each mound,

their locations, di-

mensions, and the number of burials

found in each one.

Titles of published references are

abbreviated in the

text, and these will be found in

complete form in the

Bibliography.

The picture of the Adena culture which

is presented

in the following tables is no more than

a sample, since

the entire contents of every mound are

not known. The

70 mounds may be divided into the

following four classes

on the basis of the degree of

completeness with which

each was excavated.

Mounds completely excavated... 1, 12, 13,

16, 21, 29, 31, 32, 33,

34, 35, 38, 52, 54, 70

Mounds not completely excavated 2, 3, 5, 6,

7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 14, 15,

17, 18, 20, 24, 26, 27, 39, 40,

41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 48, 49,

51, 53, 55, 56, 57, 59, 60, 61,

64, 65, 67

Degree of completeness not in- 4, 19, 22, 25, 28, 47, 50, 58, 62,

dicated in report .......... 63, 66, 68, 69

No report nor field notes....... 23,

36, 37

414

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

What there was remaining of Mounds 43

(Coon

Mound) and Mound 48 when excavations

were begun,

was completely excavated, but Mound 48

had been

largely worn away by the adjacent

stream, and three-

quarters of the portion of Mound 43

more than six feet

above the ground level had been carried

away to enrich

the gardens in the vicinity. At the

time of excavation

however, questions in regard to finds

during this process

were answered invariably in the negative,

and it is un-

likely that this mound contained

anything more, at least

in the way of objects intentionally

placed by the builders,

than that described in the present

report.

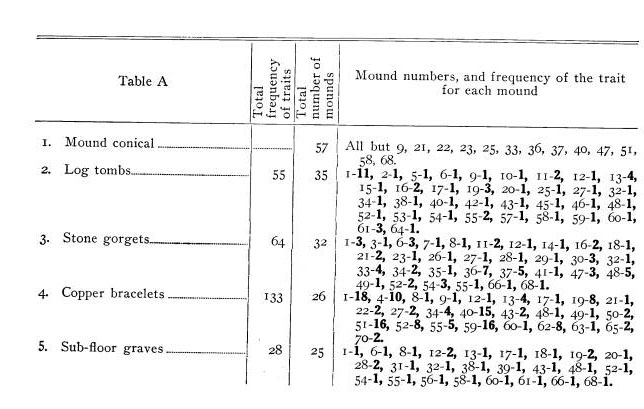

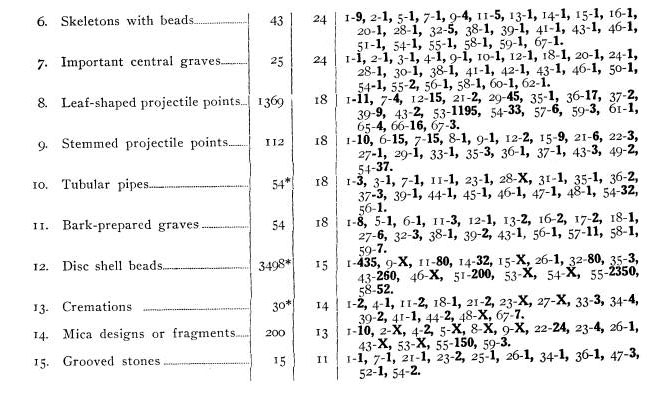

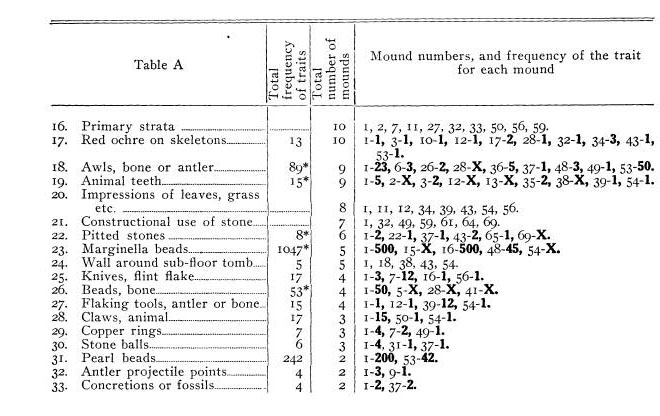

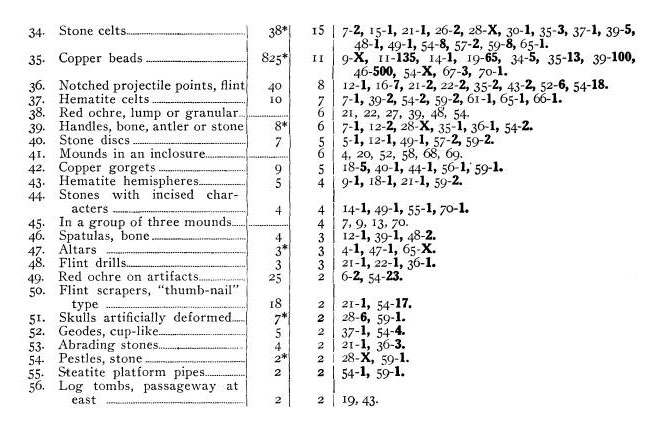

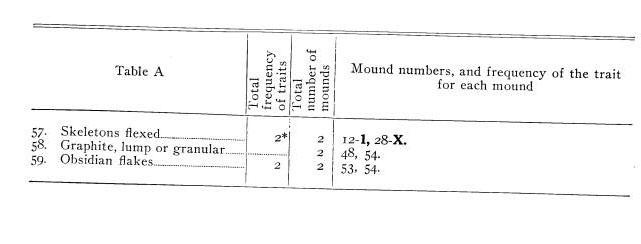

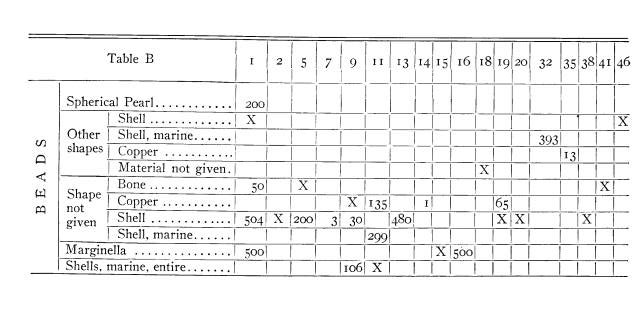

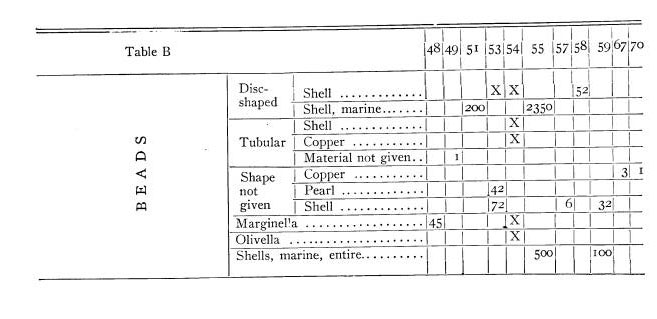

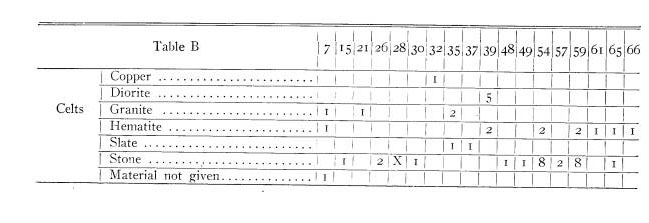

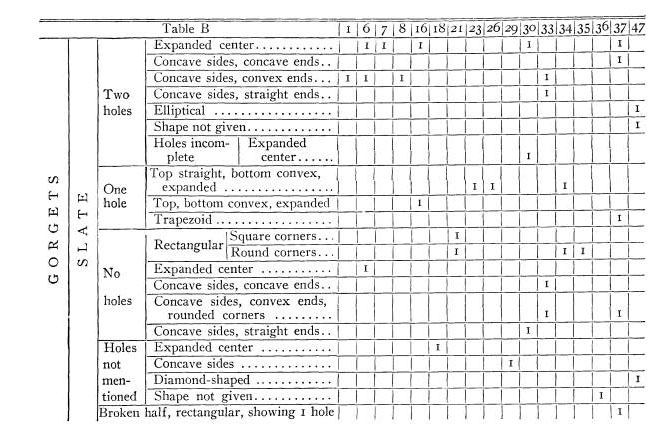

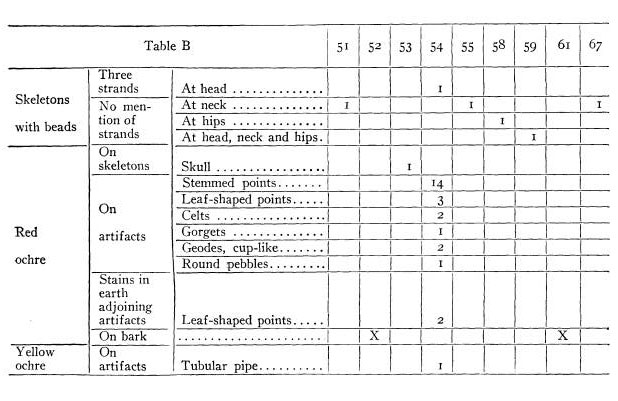

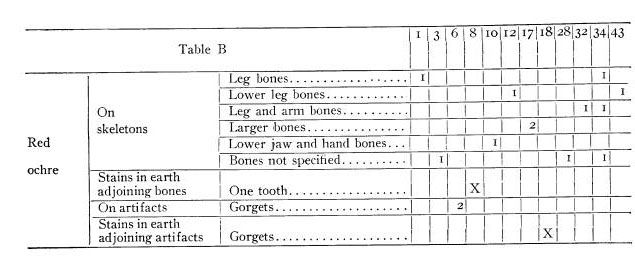

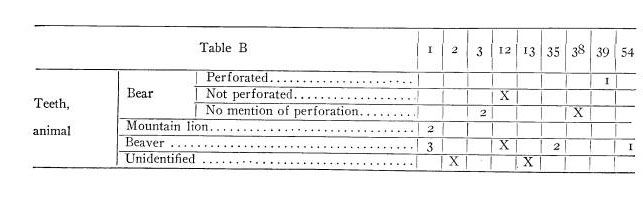

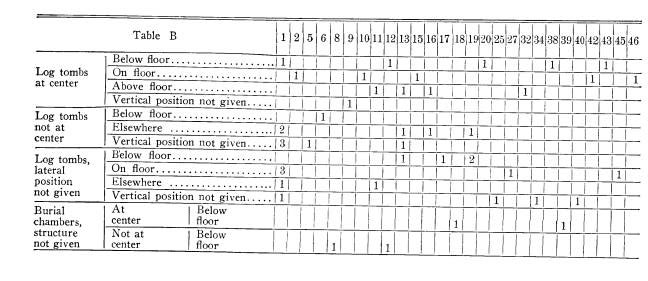

Explanation of Tables. Tables A and B list every-

thing which is of value in identifying

the culture to

which each mound belongs. This includes

all artifacts,

and other features such as burial

types, strata, positions

of burials, log tombs, shape of mound

and so forth. In

Table A the traits are arranged serially

in numbers ac-

cording to the number of mounds in

which each is found,

beginning with Trait 1, or Mound

conical, which is

found in the largest number of mounds,

a total of 57

times, and ending with Trait 59,

Obsidian flakes, which

is found in only two mounds. The total

frequency of

each trait for all mounds is also given

in Table A, except

in seven instances, where it is either

impossible to give

the number, or the number is

self-evident, as is the case

with Mound conical. In the third column

are the mound

numbers showing those mounds in which

the trait is

found, with the figure in heavy type

indicating the num-

ber of times the particular trait is

found in the particular

mound involved. Reading this Table for

Trait 2, it will

Coon Mound--Analysis of Adena

Culture 415

be found that Log tombs occur 55 times

in 35 mounds;

11 times in Mound 1, once in Mound 2,

once in Mound

5, and so on. In all tables an asterisk

after a number

indicates an obscurity in the original

report as to the

exact amount, with the number so marked

as the mini-

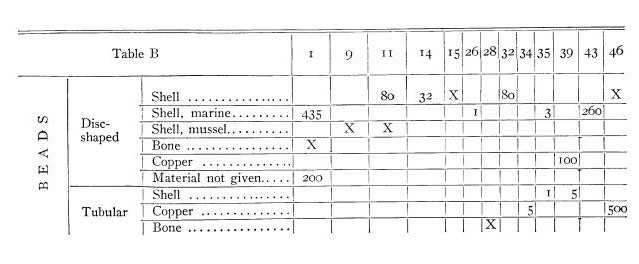

mum; an X indicates one or more. Table

B is an elabo-

ration of some of the information

contained in Table A.

For example in Table A, the term Stone

gorgets is

used generically, without

distinguishing between the dif-

ferent shapes and materials expressed

in Table B. But

all stone gorgets described in the

literature are included

in each Table. The positions of beads

and red ochre on

skeletons, the artifacts which have

been painted with

red ochre, and other detailed

information, are given in

Table B. With regard to beads, Table A

lists only disc-

shaped shell beads, bone, pearl and

copper. Table B

lists the various types of disc shell

and copper beads,

and includes other types not listed in

Table A. Table

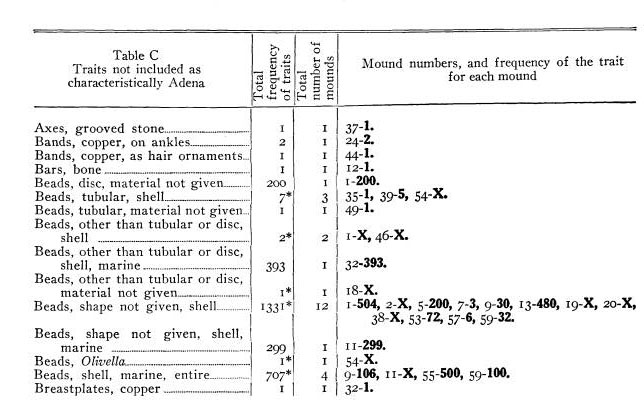

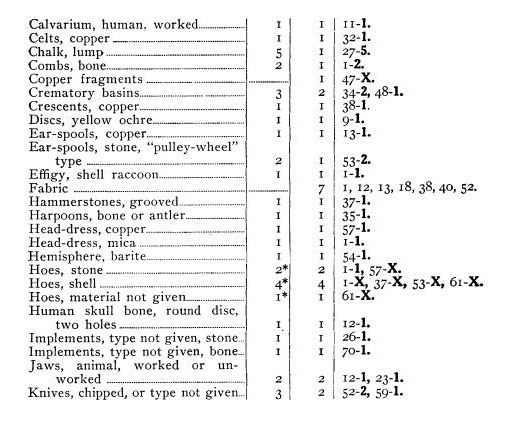

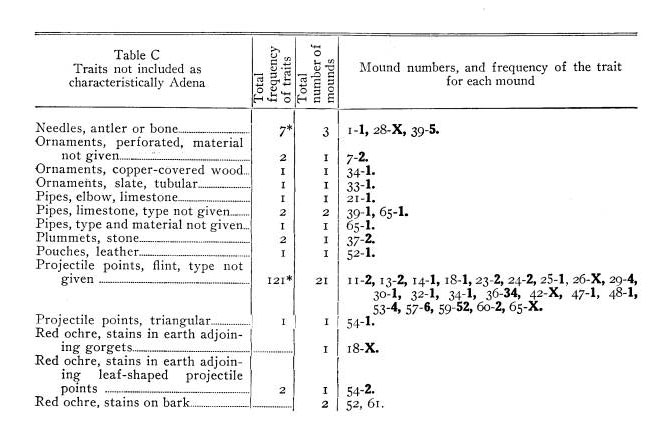

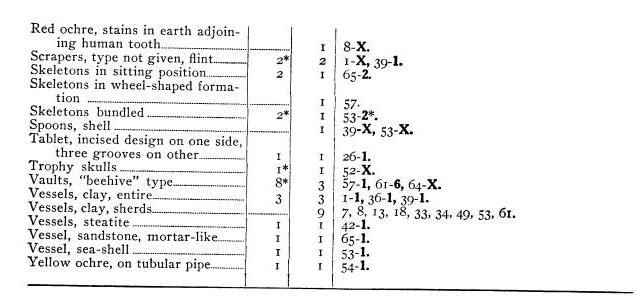

C contains traits which were not used

in identifying the

mounds as Adena in type. This Table

reads the same

as Table A, giving in the first column

the number of

times each trait occurs for all seventy

mounds; in the

second column the number of mounds

exhibiting the

trait, and in the third, the number of

times the trait is

found in each mound.

Table A consists of two parts. The

traits numbered

from 1 to 33 are all present in Mound

1, the Adena

Mound, and it is on the basis of these

first 33 traits that

the other 69 mounds are identified as

Adena. The

method of reasoning involved in this

identification is as

follows: Each of the 69 mounds contains

from two to

416

Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

17 of the 33 traits found in Mound 1.

Among these 33

traits there are some which have a

higher identification

value than others, either because they

are found a large

number of times in a large number of

mounds, or be-

cause they are found, so far as is

known to the writer,

only in mounds of the Adena type.

Copper bracelets are

an example of the former type of trait,

and grooved

stones of the latter. If a mound

exhibited but one of

these traits, with nothing indicative

of the Hopewell or

any other culture type, it would be

necessary to include it

in the Adena group. The smallest number

of times

that any series of the 33 traits found

in Mound 1 occurs

in any one of the other 69 mounds is

two, as is shown in

Table D. These mounds may be classified

as Adena de-

spite the small number of traits

exhibited by them, be-

cause they present no features

indicative of any other

culture. It is possible to doubt the

correctness of this

identification only for Mound 24, which

was in Clinton

County, Ohio, near Wilmington. The two

traits ascribed

to this mound are Conical shape and

Important central

graves, of which latter the mound possessed

one. How-

ever, the two copper objects described

in the report for

this mound as "bands," were

found at the ankles, and

their resemblance to bracelets in form,

material and use

increases the probability that this

mound is correctly

identified. These "bands" are

included in Table C. Fur-

thermore, Mound 24 was situated in a

region where

other mounds of the Adena type have

been found, includ-

ing Mound 25 in the present

classification, and the Wil-

mington Mound, which is not included

herein, but which

will be discussed later. With regard to

Mound 51, in

Coon Mound--Analysis of Adena

Culture 417

Indiana, the writer is informed by Mr.

Glenn Black of

Indianapolis that this was not a mound

but a natural

gravelly knoll. But the articles found,

16 copper brace-

lets and one skeleton with disc-shaped

sea shell beads,

are of such high identification value

as linked together

in the same group of burials that its

inclusion seems jus-

tifiable, especially since this

formation is in the general

vicinity of Mounds 49, 50 and 52. In

addition to the

conical shape of Mound 63 and the

copper bracelet

found therein, this mound is one of the

group of the

Kanawha Valley, all of which are

probably Adena in

type.

Table D gives the number of traits

found in Mound

1 which are also found in the other 69

mounds, begin-

ning with the smallest number of traits

possessed by in-

dividual mounds, and continuing down to

Mound 1 with

the entire 33 traits. Table E gives the

frequency for

each mound of those traits which occur

two or more

times in the entire group. This Table

will be discussed

later. Table F contains the key numbers

for the specific

traits possessed by each mound. Thus

for Mound 23,

which exhibits Traits 3, 10, 13, 14 and

1.5 (all of which

are found also in Mound 1 because they

are below num-

ber 34), reference to Table A will show

that these traits

are as follows: one stone gorget, one

tubular pipe, one

or more cremations, four mica designs

or fragments and

two grooved stones.

The second part of Table A, consisting

of Traits

numbered from 34 to 59, is concerned

with the estab-

lishment of a generalized Adena culture

complex. This

is a departure from the zoological

method of identifying

418 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

and describing a member of a species,

but owing to the

difference in degree of unity as

possessed by zoological

specimens of one species on the one

hand, and archaeo-

logical specimens (regarding in this

case a mound as a

specimen, and a culture as a species),

this method ap-

pears to be justified. One mound varies

in its features

from another of the same culture much

more than, for

example, does one hermit thrush from another.

The definition of the generalized Adena

culture com-

plex will be evident in the following

description of the

method by which it is established.

Table D is a compila-

tion of the figures given in Table A,

Traits 1 to 33, and it

establishes the 69 mounds as of the

same culture group

as Mound 1. Traits 34 to 59 in Table A

are found in

Mounds 2 to 70 but not in Mound 1; but

since Mounds

2 to 70 have been proved to be Adena in

type, it may be

said that all traits exhibited by them

are of that type

whether or not they were found in Mound

1, except with

regard to traits which might be the

product of local

development or of trade influences.

Such features may

be identified by ascertaining their

occurrence in but a

single region. If therefore a feature is

present only in

one mound it cannot be taken as truly

representative of

the Adena culture; the same is true if

it is found in two

or more mounds of a single group

occupying a restricted

area. Examples of such traits are to be

found in Table

C: Crematory basins, found only in

Mounds 34 and 48

in the same region; Combs, bone, of

which but two were

found in Mound 1, and Plummets, stone,

of which two

were found only in Mound 37.

Recognizing Traits 34 to 59 as

characteristically

Coon Mound--Analysis of Adena

Culture 419

Adena, they complete the entire list of

traits compris-

ing the Adena culture complex. Table E

shows the

number of these generalized traits

possessed by each

mound. It will be observed that a

number of mounds

exhibit more of the generalized Adena

traits than of

those traits found only in Mound 1.

Mounds 40 and

70, for example, showing only two

traits in Table D,

show three and five respectively in

Table E. To take

another example, Mound 54 shows only 17

traits in

Table D, and 29 in Table E. Reference

to Table F re-

veals that the 12 additional traits are

as follows: stone

celts, copper beads, notched projectile

points, hematite

celts, red ochre, handles, red ochre on

artifacts, geodes

cup-like, steatite platform pipes,

flint scrapers of the

"thumb-nail" type, graphite

and obsidian flakes.

The significance of this generalized

Adena culture

complex is in the fact that the

excavator of an Adena

type of mound at any point within the

distribution of the

mounds discussed herein may expect to

find any of the

traits numbered from 1 to 59. His

chances of finding

any of the traits enumerated in Table C

are remote, with

the exception of those traits in this

Table which are not

adequately described in the literature.

446 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

TABLE D

Traits found only in Adena Mound.

Frequency in the remaining

69 mounds.

Number of

traits Mound numbers

2............... 24, 25, 40,

63, 68, 70.

3................30, 42, 44, 45,

47, 51, 62, 64, 69.

4................10, 14, 19, 22, 29,

31, 33, 57, 65, 66, 67.

5................4, 20, 23, 50, 60, 61.

6................3, 5, 8, 15, 17, 21, 26, 36,

41, 46, 52, 58.

7................2, 6, 13,

16, 18, 35, 49.

8................9, 27, 34, 37, 38, 53, 56.

9................28, 48, 55, 59.

10............... 7, 11, 32, 39.

13 ................12.

15................ 43.

7

................ 54.

33.иииииииииииииии1.

TABLE E

Frequency of generalized Adena traits in

the entire 70 mounds.

Number of

traits Mound numbers

2................24, 25, 63.

2 ...

24, 25, 63.

3................40, 42, 45, 51,

62, 64, 68.

4................10, 29, 30, 31, 33, 44,

47, 69.

5................23, 50, 60, 66, 67, 70.

6................3, 8, 14, 17,

19, 20, 41, 57, 61.

7................2, 4, 5, 15, 22, 26, 46, 58, 65.

8................6, 13, 16, 38, 52.

9................18, 27, 34, 36,

53, 56.

10................32, 37, 49, 55.

11 ...............9, 11, 35.

13................21, 48.

14

..............7, 28.

Coon

Mound--Analysis of Adena Culture 447

Number of

traits Mound numbers

15

................39.

17................

43, 59.

18 ................ 12.

29 ................54.

33 ................ 1.

TABLE F

Mound

number Trait numbers

1....1 to 33.

2.... 1, 2, 6, 7, 14, 16, 19.

3....1, 3, 7, 10, 17,

19.

4....1, 4,

7, 13, 14, 41, 47.

5.... 1, 2, 6, 11, 14, 26, 40.

6 ....1, 2,

3, 5, 9, 11, 18, 49.

7... 1, 3, 6, 8, 9,

10, 15, 16, 25, 29, 34, 37, 39, 45.

8....1, 3, 4,

5, 9, 14.

9....2, 4, 6, 7, 9, 12, 14, 32, 35, 43, 45.

10....1, 2, 7,

17.

11.... 1, 2, 3, 6, 10, 11, 12, 13, 16, 20, 35.

12....1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9,

11, 17, 19, 20, 27, 36, 39, 40, 46, 57.

13....1, 2, 4,

5, 6, 11, 19, 45.

14 ....1, 3, 6,

12, 35, 44.

15.... 1, 2, 6, 9, 12, 23, 34.

16....1, 2, 3,

6, 11, 23,

25, 36.

17 ..1, 2, 4, 5, 11,

17.

18 ....1, 3, 5,

7, 11, 13, 24, 42, 43.

19....1, 2, 4,

5, 35, 56.

20.... 1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 41.

21....3, 4, 8, 9, 13,

15, 34, 36, 38, 43, 48, 50, 53.

22.... 4, 9, 14, 22,

36, 38, 48.

23 .... 3, 10, 13, 14, 15.

24....1, 7.

25....2, 15.

448 Ohio Arch. and Hist. Society Publications

Mound

number Trait numbers

26 .... 1, 3, 12, 14, 15,

18, 34.

27....

1, 2, 3, 4, 9, 11, 13, 16, 38.

28....1, 3, 5, 6, 7, 10, 17, 18,

26, 34, 39, 51, 54, 57.

29....1, 3, 8, 9.

30 ....1, 3, 7, 34.

31... .1, 5, 10, 30.

32....1, 2, 3, 5, 6,

11, 12, 16, 17, 21.

33 ... 3, 9, 13, 16.

34 ....1, 2, 3, 4, 13, 15, 17, 20,

35.

35 ....1, 3, 8, 9, 10, 12, 19, 34,

35, 36, 39.

36....3, 8, 9, 10, 15,

18, 39, 48, 53.

37.... 3, 8, 9, 10, 18, 22, 30, 33, 34, 52.

38.... 1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 11, 19,

24.

39 ....1, 5, 6, 8, 10, 11, 13, 19, 20, 27,

34, 35, 37, 38, 46.

40....2, 4, 42.

41....1, 3, 6, 7, 13, 26.

42.... 1, 2, 7.

43 ....1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 14, 17, 20, 22, 24, 36, 56.

44 ....1, 10, 13, 42.

45 ..1, 2, 10.

46.... 1, 2, 6, 7, 10,

12, 35.

47 ....3, 10, 15, 47.

48....1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 10,

13, 18, 23, 34, 38, 46, 58.

49 ...1, 3, 4, 9, 18, 21, 29, 34, 40, 44.

50 ....1, 4, 7, 16, 28.

51....4, 6, 12.

52.... 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 15,

36, 41.

53

...1, 2, 8, 12, 14, 17,

18, 31, 59.

54....

1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 15, 19, 20, 23, 24,

27, 28, 34,

35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 49, 50, 52, 55, 58,

59.

55....1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 12, 14, 44.

56 ... 1, 5, 7, 10, 11, 16, 20, 25, 42.

57 ....1, 2, 8, 11, 34, 40.