Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

AN EDDY IN THE WESTERN FLOW OF AMERICAN

CULTURE

The History of Printing and Publishing

in Oxford, Ohio,

1827-1841

By

JESSE H. SHERA

(103)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

It is, I am well aware, not customary to

append to a study as

brief as this a lengthy list of

acknowledgments. Nevertheless,

there are in this instance certain major

obligations the public rec-

ognition of which, I am convinced, is

not an act of supererogation.

Accordingly, I would express my

gratitude to: Mr. Douglas C.

McMurtrie of Chicago for helpful

information leading to the dis-

covery of certain hitherto unknown

items; Miss Adelia W. Cone

of the Miami University faculty and

former president of the Ox-

ford Town and Township Historical

Society, for much valuable

criticism and advice; and the members of

the Oxford Town and

Township Historical Society collectively

for their patience in lis-

tening to the reading of this document

in its preliminary form.

My two most important debts, however,

are to my intimate

friends James H. Rodabaugh of Ohio State

University, and Ed-

gar W. King, librarian of the Miami

University Library. The

former, who unquestionably knows more

concerning the history

of Miami than any other single

individual, has been most generous

in giving to me without stint the

results of his own investigations.

The latter, in his official capacity as

librarian, has at all times

placed at my complete disposal without

restriction the resources

of his library. But it is in his

personal relation as colleague and

friend that my debt to him is greatest,

for this study was originally

begun at his suggestion, and might very

well never have been com-

pleted without his help and

encouragement. My debt to both these

men is very great; they are responsible

for most of the merit that

this paper contains--its faults are

entirely my own.

J. H. S.

(104)

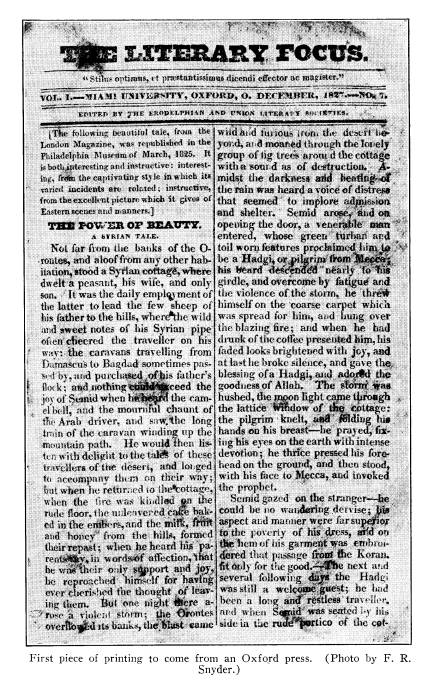

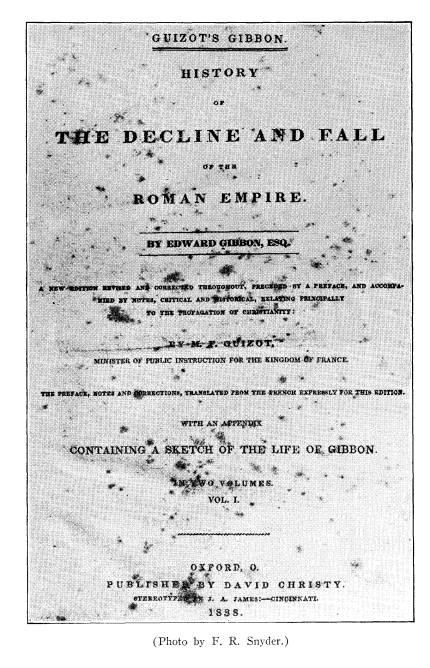

THE HISTORY OF PRINTING AND PUBLISHING

IN

OXFORD, OHIO, 1827-1841

It has today become rather trite to talk

of the trials and hard-

ships that beset that eager group of

students that came to the

newly-opened doors of Miami University

in the middle of the

1820's; and many who are prone to look

askance at the compar-

ative ease of college life of the

present, and its attendant attrac-

tiveness for the intellectually

incompetent are inclined to feel that

the selective influence of pioneer

hardship was not an unmitigated

evil. It is thus rather easy to become a

little sentimental over the

courage of these inexperienced boys,

who, in the spring of 1827,

set to work to create and carry through

a literary publication at

Miami.

On the other hand, it is equally easy to

go to the opposite ex-

treme, and, remembering that "the

thoughts of youth are long,

long, thoughts," dismiss the entire

matter as ill-advised boyish am-

bition, thoroughly unworthy of serious

study after the passage of

a hundred years. As usual the proper

viewpoint lies between

sentimental glorification and absolute

disparagement. Thus, to

understand and interpret fully the

spirit that motivated such lofty

literary ambitions it is best to

consider briefly the soil from which

this activity sprung. To project, in

short, the Literary Focus, and

all it represents upon the background of

certain social and eco-

nomic forces of which it was a

logical--and indeed one might say

an almost inevitable result.

The limitations of the present

discussion preclude the pos-

sibility of any extensive considerations

of the westward flow of

American culture in its larger aspects;

all this has been dealt with

in better fashion elsewhere. Suffice it

here to say that with the

termination of the Revolutionary War,

the resultant establishment

of a stable form of governmental

organization, and the continual

pushing westward of the frontier, the

way was opened for the

(105)

106

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

rather rapid flow of cultural ideas and

literary forms from the

Eastern centers to the vast areas of the

hinterland. As a mani-

festation of this movement, Miami

University, of course, played

her part in numerous ways. Our immediate

concern with all this,

however, is confined to but one highly

specialized phase; the ex-

tent to which, and the methods by which

the tangible expression

of this culture were impressed in

concrete form on paper--and,

more specialized still, on paper, not by

pen and ink, but through

the medium of movable types and the

printing press.

By 1827, printing in the United States

was by no means in its

infancy from the standpoint of years.

Indeed, almost two cen-

turies had passed since the ill-fated

Rev. Jose Glover set out from

the shores of England to bring to this

country its first printing

press, and only two decades after the

landing of the Pilgrims, since

that incunabulum of American printing,

the Bay Psalm Book,

came from the press of Stephen Day. Even

in Ohio, printing on

a considerable scale had been going on

for some time. For on

November 9, 1793, William Maxwell of

Cincinnati sent out the

first issue of the Centinel of the

Northwest Territory, the first

newspaper to be published north of the

Ohio River. While only

three years later, Maxwell's Code,1

the first book to be published

in Ohio, came from the same press.

During the first two decades of the

nineteenth century the

press spread rapidly in Ohio, and by 1824, the U. S.

Postmaster

reported that out of 598 papers being

published in the entire coun-

try, forty-eight were coming from Ohio,

which, with the excep-

tion of Pennsylvania which could boast

of 110, was well in ad-

vance of any of the surrounding states.

The chief difficulty that

beset these early printers was not so

much the procuring of ink,

type, and machinery, as the scarcity of

paper; a deficiency that

made itself felt even in the editorial

offices of the Literary Focus,

for in the issue for August, 1827, one

finds the editors apologizing

for delayed publication and offering as

an excuse:

1 Laws of

the Territory of the United States, Northwest of the Ohio, Adopted

and Made by the Governor and Judges, in Their Legislative

Capacity, at a Session

Begun on Friday the XXIX Day of May, One Thousand Seven

Hundred and Ninety-

five, and Ending Tuesday, the 25th Day of

August Following, with an Appendix of

Resolutions and the Ordinance of the Government of the Territory; by Authority.

(Cincinnati, 1796), 225p.

HISTORY OF PRINTING, OXFORD, OHIO 107

The Focus, would have been issued

earlier in the month, had our printer

not been disappointed in receiving

paper. The publication of every journal

in the Western country is attended with

this difficulty, unless the proprietor

happens to reside in the immediate vicinity of a paper mill.2

The first paper mill in the West was

erected during the years

1791 to 1793, by Craig, Parkers &

Co., of Royal Springs, George-

town, Kentucky, and William H. Venable

in his Beginnings of

Literary Culture in the Ohio Valley, reports that "the first of the

numerous paper mills on the Miami river

was erected in the year

1814."3 Type-founding was somewhat

slower of development, as

the first of its kind to be established

on the Ohio was that opened

by John P. Foote and Oliver Wells in

Cincinnati, in 1820, and it

is entirely possible that the fonts used

by the Societies' Press may

have come from there.

Thus, by the middle of the third decade

of the nineteenth

century, literary activity in this

region was growing apace; news-

papers, books, and periodicals, the

latter frequently religio-literary

in character, were springing up like

proverbial mushrooms, a par-

ticularly fortunate simile since so many

of them were shallow-

rooted and ephemeral. All this, too, was

being aided and abetted

by the considerable growth of industries

essential to the printer's

craft: type-founding and paper-making.

In such an atmosphere

it is small wonder that these ambitious

youths, so recently come

to the halls of learning, should think

of giving form in a tangible

way to their callow philosophies. So, in

June of 1827, under what

seems to our unclassical minds an

ostentatious slogan: "Stilus op-

timus et praestantissimus dicendi

effector ac magister,"4 the Lit-

erary Focus, was launched, and Oxford's first publishing venture

had begun. From the standpoint of

literary content it was, in-

deed, no unpretentious beginning. There

can be no doubt that

literary ambition ran riot on the Miami

campus. Even in the first

issue the editors feel constrained to

apologize to the host of con-

tributors that limitations of space had

necessitated rather rigid

selection. These "rejected

addresses" have not been preserved

to posterity, and judging from those

that did see the light of day

2 Literary Focus (Oxford, Ohio, 1827-28), August, 1827, 46.

3 William H. Venable, Beginnings of

Literary Culture in the Ohio Valley;

Historical and Biographical Sketches (Cincinnati, 1891), 43.

4 Cicero, De Oratore, liber 1,

cap. 33.

108

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

in print, it may be just as well; for

the boys' literary "reach" cer-

tainly exceeded their "grasp."

But, literary criticism is without

the province of the present discussion;

and, anyway, much ink has

already been spilled over the immaturity

and self-consciousness

of style of these yellowed pages of the Focus.

This is taking

rather unfair advantage of these

ambitious young gentlemen; for

certainly no one, unless he has the

genius of a John Keats or the

self-esteem of a Bernard Shaw, would in

after-years be partic-

ularly eager to have his collegiate

scribblings preserved for future

generations. At least the Focus was

accorded the compliment of

plagiarism; witness this delicately

feathered shaft from the pen

of the editors:

Literary piracy appears to be the

prevailing theme for Editorial con-

tention. We do not desire to enter into

the lists with any of our bretheren

of the press; but we can see no harm,

after making our best bow to the

Editor of the Augusta Herald, in asking

him where he met with the short

essay entitled "Independence of

Mind" which appeared in his 47th number.5

From the standpoint of economics, the

cards were, of course,

stacked against the venture from the

beginning. Though in sub-

sequent issues the publication boasted a

list of agents of some

dozen names in length in Ohio and

Kentucky; and though there

seemed to be plenty of subscribers, some

of whom resided else-

where than in Oxford, the payment of

subscription fees seems to

have been a custom "more honored in

the breach than the ob-

servance." Even the addition of a

fifty-cent penalty to the regular

subscription price of one dollar was

apparently futile in stimulat-

ing payment before the end of the year.

As early as November,

the editors assert that: "The

patronage afforded our little peri-

odical has fully equalled our most

sanguine expectations; and

would be amply sufficient to defray all

the expenses of publication,

were our friends as ready to pay as

to subscribe."6 That there

were subscribers at least as far distant

as Hamilton is evident

from the fact that sixty years later,

Cyrus Falconer mentions vis-

its to that city which were not entirely

unsuccessful attempts to

augment the subscription list.7

Prior to 1827, all university printing

had been done in Ham-

5 Literary Focus, November, 1827, 114.

6 Ibid., 93.

7 Miami Journal (Oxford, Ohio), January, 1888.

HISTORY OF PRINTING, OXFORD, OHIO 109

ilton by established print shops. In

1814, Keen and Stewart had

printed the laws passed by the Ohio

State Legislature establishing

Miami University. A year later, the same

organization, then

Keen and Colby, printed a report of the

president and trustees of

of the university. While the first

catalogue to be issued by Miami

came also from Hamilton, and from the

press of James B. Cam-

ron. Thus, it was only natural that once

the two literary societies,

Miami Union and Erodelphian, had decided

to unite their efforts

to produce a literary periodical, and

had appointed a joint com-

mittee to take the project in hand, that

they should approach Cam-

ron in Hamilton for a printing contract,

and as a result the Focus,

from June to November of 1827, bears the

imprint of "James B.

Camron, Printer."

But the arrangement seems either not to

have been entirely

satisfactory, or, what is more probable,

the boys' ambitions were

suffering from growing pains. In any

event, the issue for Novem-

ber carries the information that an old

press had been procured,

and that thereafter the printing would

be done at Oxford by the

boys themselves.8 This move

the editors felt to be particularly

advantageous, for not only would the too

frequent errors in proof-

reading be avoided, but a somewhat

smaller type could be used,

and the monthly issue enlarged from

sixteen to twenty-four pages.

Thus the worthy subscribers would get

much more reading mat-

ter and there was to be no advance in

price. Indeed the impecu-

nious editors would have been only too

glad to accept the original

fee.

The new press was named appropriately

enough, the Societies'

Press, with obvious reference to the two

constituent literary so-

cieties, Erodelphian and Miami Union,

while J. D. Smith seems

to have been the chief printer in

charge, since his name appears

in the colophon at the end of each

issue. The editorial committee

was elected by the two literary

societies, so that the project was

actually a joint undertaking; but the

editor-in-chief was Robert

Cumming Schenk, afterwards lawyer in the

District of Columbia,

member of the House of Representatives,

major-general in the

Civil War, and minister to England from

1871 to 1875. To

8 Literary Focus, November, 1827, 93.

110

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

Schenk went the large share of editorial

responsibility, and his

contributions appeared probably more

frequently than those of

anyone else.9

The newly acquired press itself was, of

course, of the hand-

operated type, doubtless of cast iron

construction similar to the

Stanhope, the Columbia, or the

Washington hand-press, since the

mass production of these was at this

time just beginning. At this

date the old wooden presses had become

virtually obsolete through

the invention in the middle of the

preceding century of a press

made almost entirely of iron by the

Swiss typefounder, Wilhelm

Haas. Thus the way to quantity

production was opened, and by

the early part of the nineteenth century

a great number of these

presses were being produced in both

England and America. The

Societies' press was, of course, of the

flat-bed variety, for it was

not until 1814 that the first

commercially successful cylinder press

was invented by Frederich Koenig of

Saxony, while it was only

during the period under discussion that

the London Times was

just beginning its extensive experiments

with newer types of

higher speed machinery.

But with all the mechanical and literary

improvements in the

Focus, its financial fortunes were showing no gains. Despite

the

fact that the boys admitted editorially

that they had learned much

since the project was inaugurated, they

had evidently not learned

enough, for with the issue of May, 1828,

they published the fol-

lowing rather hopeless financial

statement:

Balance we are indebted for printing,

stationary, and incidental ex-

penses

...................................................... $100.00.

Amount of cash in the treasury to defray

these bills ....... 000.00.10

Such a statement could mean but one

thing, and at the time

of its publication, after a parting wail

directed toward the unpaid

subscribers, the Focus passed

into the limbo of thwarted ambi-

tions. Thereafter, the members of the

literary societies, relieved

of the burdens of publication, turned

their ever active minds from

the graphic arts to the fine arts, and

became involved in that affair

9 Miami Journal, loc. cit.

10 Literary Focus, May 1828.

HISTORY OF PRINTING, OXFORD, OHIO 111

so delightfully characterized by Dr.

Alfred H. Upham11 as "The

Portrait and the Bust,"--but that,

of course, is another story.

However, one must not think that Oxford

was to be without

a literary periodical, for, as early as

March, 1828, with extinction

"just around the corner," the

editors of the Focus, after a lengthy

discourse on the value of a weekly paper

to a community, calmly

announced that Oxford would have one. It

was to be called the

Literary Register; it was to supplant the dying Focus; it was to

bring the news of the day to the local

countryside; the first issue

was to appear on Monday, June 2, 1828,

and its price was to be

but two dollars annually12--hope indeed

springs eternal. The

faculty of Miami, however, though they

shared the optimism of

the boys as to the need in the community

for such a publication,

felt "unwilling that young

gentlemen under their care should en-

gage in any enterprises which might

involve their parents and

relatives,"13 and in the

issue of the Focus for May, 1828, an-

nounced that the forthcoming issues of

the Register, would be

under the entire direction, both

financial and editorial, of Presi-

dent Robert Hamilton Bishop and

Professors William H. Mc-

Guffey and John E. Annan.

Thus, on Monday, June 2, 1828, the Literary

Register, pub-

lished at the Societies' Press, by

Smith, and in the same octavo

format of the old Focus, was

born. For a time the Register did

appear to prosper, for in the issue of

July 14 the editors happily

announce that "the number of

subscribers to the Register con-

tinues to increase. Almost every arrival

of the mail14 brings us

some names, and--shall we say it?--some

money."15 The con-

tents of the publication did

unquestionably hold more of interest

for the general reader than did the old Focus,

and from every

standpoint it was a more meritorious

publication. Some fifteen to

twenty agents were established

throughout Ohio, Indiana, Ken-

tucky, and Pennsylvania, and the

publication showed on the whole

11 Alfred H. Upham, Old Miami; the

Yale of the Early West (Hamilton, Ohio,

1909), 66.

12 Literary Focus 169-71.

13 Ibid., May, 1828, 240.

14 It must be remembered that the mail

arrived at quite infrequent intervals in

those days.

15 Literary

Register (Oxford, Ohio, 1828-29), July

14, 1828, 108.

Vol. XLIV--8

112 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND

HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

a reasonable degree of prosperity,

though never, of course, any

great degree of opulence.

Though the work was still done on the

Societies' press, others

were helping materially. With the issue

of August 11, the name

of Smith is dropped, and the office of

printer is taken up by Robert

H. Bishop, Jr., with the issue of

September 8. With the issue of

September 24, the name of H. H. Harrison

appears as printer, but

his interest was of apparently brief

duration as his name is

dropped with the issue of October 27,

and by December 20, he is

advertising as a tobacconist. One would

like to think that this

fondness for tobacco had its inception

in Miami's literary halls,

where the atmosphere must have been

highly charged with the

polysyllabic ponderosities of forensic

disputation and the blue haze

of tobacco smoke.

At best, however, the obligations of the

Register weighed

heavily on the shoulders of the three

Miami professors, so that

they were doubtless quite glad to

relinquish the publication at the

end of the first volume into the hands

of C. A. Ward and William

W. Bishop. This change of directorship,

which took place with

the first issue of Volume II under date

of December 20, 1828, in-

volved a number of improvements. The

format was forthwith

changed from octavo to quarto, and

advertisements were intro-

duced, albeit not without due apologies

to the subscribers, for the

Focus and the old Register had kept their pages

unsullied by such

commercialism. The publication, though

it was now definitely

in private hands, was still regarded as

a stepchild of the two lit-

erary societies, and it was accordingly

decided that "a moiety of

the profits accruing from the

publication should be appropriated

to the" treasuries of Erodelphian

and Union.16 The payment of

subscriptions to the Register was

also facilitated by the acceptance

of "all kinds of produce" in

lieu of money, an arrangement now

thoroughly practicable since the

enterprise was in private hands.

With this change in management came also

the removal of

the old press from its room within

"the college building" to the

recently opened book store of Ward and

Bishop in "the yellow

l6 Ibid., June

27, 1829, 411.

HISTORY OF PRINTING, OXFORD, OHIO 113

frame house on Main St., formerly

occupied by Mr. Woodruff as

a taylor shop." At this location

Ward and William W. Bishop,

the eldest son of President Robert

Hamilton Bishop, established

a complete printing and publishing

enterprise. Each issue of the

Register carries their advertisement, not only for the school

texts

necessary for the students of the

university, but also for job print-

ing of all kinds, and general book

binding as well. For the mo-

ment, the outlook for the Register was

somewhat encouraging; but

this transfusion of new blood into its

veins was ultimately of no

avail, and at the conclusion of Volume

II, with the issue of June

27, 1829, just two years after the inauguration of the Focus, un-

qualified defeat was acknowledged. The

editors, admitting that

lack of patronage was the true cause but

still heroically maintain-

ing that there was a real need for such

a journal in the community,

were forced to the wall. It is true that

the advertisements had

brought in some revenue, but

unfortunately in those days there

was no Listerine or Lucky Strike with

fat advertising contracts

to pull the financial chestnuts out of

the fire, and the editors had

no alternative.

The demise of the Register effectively

squelched all journalis-

tic activity of this sort in Oxford for

a period of almost four

years. At the end of this time, however,

the courage of William

W. Bishop had sufficient opportunity to

revive, so that on Satur-

day, February 16, 1833, there appeared

Volume I, number one,

of the Oxford Lyceum and Journal of

Literature and Science, in

format much like volume two of the Register,

and issued under

the editorship of William W. Bishop,

with the assistance of An-

drew Noble, printer. The headquarters of

the new Lyceum were,

of course, the Bishop print shop and

book store, and the typog-

raphy was a product of the old

Societies' press.

The Lyceum was modeled directly

after the Register, was

issued every other Saturday, and was to

be for all residents of

Oxford and the surrounding countryside;

though, of course, it

drew largely for its support, both for

contributions and subscrip-

tions, from the university and its

students. Mr. James H. Roda-

baugh has admirably summarized the

contents of this publication

when he asserts:

114

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

In the pages of this paper were

published advertisements, news items,

and essays or letters, usually from

students. The advertisements of the

"Oxford Female High School"

which had been established in 1831, and of

the "Oxford Female Academy"

were carried in the paper. Here we find

an announcement of an "Oxford

Circulating Library," of an Oxford Board

of Health, consisting of R. H. Bishop,

W. H. McGuffey, J. R. Hughes, M.

D., M. C. Williams, M. D., and Samuel C.

Rogers, "to make preparations

for an apprehended visit of the

Cholera." Among the industries in Oxford

at the time, it was noted that Charles

W. H. Temple was making fire en-

gines.

A great amount of the space allowed to

the use of the students was

taken up with essays on

"love-making." One article

signed "Monomaniac"

was entitled "Love." Another

letter favored kissing and love-making after

the common hour for bedtime."17

The fortunes of the Lyceum were

almost identical with those

of its predecessors, for in the issue of

January 18, 1834, one finds

the editor complaining that: "It is

frequently remarked that our

paper is not very good, and indeed some

go so far as to say it is

worthless."18 The first volume of this periodical was complete

with the issue for February 1, 1834,

which carried the following

editorial comment:

The editor being absent at the East, the

second volume of the Lyceum

will not be commenced for some weeks,

from which time it is contemplated

to issue it weekly. Additional

assistance will be obtained in publishing the

Lyceum; and its character otherwise improved.19

On March 22, 1834, appeared the first

issue of the Oxford

Chronicle, printed and published by William W. Bishop and An-

drew Noble, and under the general

editorship of H. B. Mayo.

This publication is without doubt a

continuation of the Lyceum,

though its format has been changed from

quarto to a larger size

approaching that of the folio, and a new

editor has been obtained.

Doubtless, also, these improvements are

the ones referred to in

the final editorial of the Lyceum. The

Chronicle was to have been

issued every Saturday, and in content is

much like its immediate

predecessor. In launching this new and

enlarged venture, the

editor says in part:

We present to the public today, in

substitution of the Oxford Lyceum,

the first number of the Oxford

Chronicle. We ask to be indulged while we

make a summary exception of some of our

views. We do not claim to be-

17 James H. Rodabaugh, History of

Miami University from Its Origin to 1845;

a thesis submitted in candidacy for the

degree of Master of Arts (Oxford, Ohio,

1933), 106-7.

18 Oxford Lyceum and Journal of

Literature and Science (Oxford,

Ohio, 1833-34),

January 18, 1834, 200.

19 Ibid., February 1, 1834, 207.

HISTORY OF PRINTING, OXFORD, OHIO 115

long to either of the existing

parties--that is, the administration or the op-

position--for to these two forms all the elements of

party are now reduced.

We design to give to the present

administration, our support in all its

measures that we think will promote the

public welfare--to oppose all that

seem to us to have a contrary tendency;

but to be factious neither in our

support nor our opposition.20

It is further of interest to note that

this same issue of the

Chronicle carries an advertisement for all types of job printing,

inquiries to be made at the office of

the Chronicle on High Street.

Evidently Oxford journalism had outgrown

the yellow frame

house on Main.

Just what fortunes befell the Chronicle,

it is extremely diffi-

cult to say, for there are only two

issues of the publication known

to the writer: Volume I, number one,

March 22, 1834, and Vol-

ume I, number four, April 19, 1834, and the originals of both of

these are in the Museum of the Ohio

State Archaeological and

Historical Society. In any event, all

this literary activity seems

not to have been pleasing to Hamilton

contemporaries, for in the

opening issue of the Chronicle, the

editors complain:

Upon the appearance of the last number

of the Lyceum the editor of

the Hamilton Intelligencer indulged

itself in a little sly jeering at its ex-

pense. We do not accuse the worthy

editor of knowing that it was the

last.... He no doubt supposed it to be a case merely of

suspended anima-

tion.... But sure we are that if the

case had indeed been such, a resuscita-

tion inevitably must have followed the

application of such galvanic power

of satire. But at the sight of the

present enlarged sheet and altered form

he will discover that the truth is--it

is simply a case of chrysalis transfor-

mation; and if the change works any

improvement, let the said editor be-

ware how in future he shoots off his

jokes in this direction, lest we shed our

skin again and emerge at length in the

fair form and goodly proportions

of the erudite Intelligencer; and

peradventure when we have put on the out-

ward shell thereof, we may strain our

wits to catch some portion of the

flavor of the kernel.21

It seems reasonable to assume, however,

that the Chronicle

did not survive the rigors of life for a

very long period, certainly

not more than the customary year, if,

indeed, that long.

Another bit of flotsam on the sea of

Oxford print is the

Schoolmaster and Academic Journal, a semi-monthly, pedagogical

in character, published first on May 8,

1834, under the editorship

of Benjamin Franklin Morris. Only one

copy of this is known,

and it is safely housed in the Widener

library at Harvard Uni-

20 Oxford Chronicle (Oxford, Ohio, 1834-?), March 22, 1834.

21 Ibid.

116 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

versity, an octavo of sixteen pages,

format and internal evidence

giving every indication of its having

been the product of the Bishop

press. The editor, Morris, graduated

from Miami in 1832, at the

age of twenty-two. After receiving his

theological training at

Lane Seminary, he occupied numerous

pulpits in Congregational

and Presbyterian churches in Ohio,

Indiana, Illinois, and Iowa.

In later years, however, he moved to

Washington, District of Co-

lumbia, where he became engaged in the

publication of The Chris-

tian Life and Character of the Civil

Institutions of the United

States, and the authorship of the life of Thomas Morris.

But to return to the known publications

of the Societies'

Press, it must not be assumed that under

its several managements,

there were printed only periodicals, for

from it came all types of

printing, and doubtless a reasonable

amount of job work. The

remains that have come down through the

years, however, consist

largely of pamphlets. Of these there are

known to be in exist-

ence some thirty items, bearing the

imprints of either Smith,

William W. or Robert H. Bishop, Jr.,

Noble, or merely "The

Societies' Press." Most of these

pamphlets were addresses and

sermons delivered at Miami University,

before the graduating

classes or the literary societies, and

in the neighboring churches.

A large proportion of them are, of

course, by President Robert

Hamilton Bishop, but there are

contributions from many others.

Here one finds John W. Scott discussing The

Cholera; God's

Scourge for the Chastisement of

Nations, or Chauncey N. Olds

on The Nature and Cultivation of a

Missionary Spirit, and a host

of others including John McRae, John

McArthur, Mayo, James

D. Cobb, Richard H. Coke, Samuel

Galloway, and John P. Har-

rison. By this press were issued also

the annual catalogues of the

officers and students of Miami

University, job printing that must

have brought welcome revenue to the

depleted coffers of the own-

ers of the press. At least four books

came from the Societies'

Press, all by Dr. Robert Hamilton

Bishop. His Manual of Logic,

in two editions, 1830 and 1831; The

Elements of Logic, in 1833;

and Sketches of the Philosophy of the

Bible, in the same year,

and later The Elements of the Science

of Government, in 1839.

HISTORY OF PRINTING, OXFORD, OHIO 117

All of these are in octavo form and vary

in length from 109 to

305 pages.

The imprints of William W. Bishop stop

during the year

1834, at which time he left Oxford and

went West to seek new

fortunes. The old press, the book store,

and all the appurte-

nances thereto were left in the care of

Robert H. Bishop, Jr.,

who sometime previously had returned

from Hanover College

where he had been teaching mathematics.

Robert H. Bishop, Jr., seems not to have

shared the jour-

nalistic ambitions of his brother, for

the imprints that bear his

name are largely confined to regular job

work. His only relation

to any periodical venture being a brief

connection as printer to

the Christian Intelligencer and

Evangelical Guardian, during the

years 1837 to 1839, but more of that

later.

In 1838, William W. Bishop returned to

Oxford, and again

went into the old print shop and his

imprints begin anew. Robert

H. Bishop, Jr., on the other hand, with

matrimony and a profes-

sorship in Latin at the university in

the offing, was doubtless

quite willing to relinquish his interest

in the business.

The unbounded optimism of the frontier

appears to have re-

juvenated the ambitions of the elder scion

of the house of Bishop,

so that by May, 1839, he affiliated with

a new venture, The West-

ern Peace-maker and Monthly Religious

Journal. This newly-be-

gotten enterprise was under the

editorship of Robert Hamilton

Bishop, Sr., Samuel Crothers, Calvin E.

Stowe, Scott, and Thomas

E. Thomas, and had as its main function

to bring together in har-

mony and unity the two opposing schools

of the Presbyterian

Church. In this cause it was, indeed, a

militant fighter, and its

rather dreary pages are filled with much

serious discourse on the

virtue of mutual understanding and

sympathy. As intimated, the

publication was begun with the issue for

May, 1839, and survived

through nine bi-monthly issues, the last

being that for September,

1840. In calling it a

"monthly" religious journal the editors were

giving themselves the benefit of the

doubt, for it was never issued

at such frequent intervals. It sold for

twenty-five cents a copy,

$1.50 for twelve numbers in advance, or $2.00 if paid after the

publication of the sixth issue, and

carried no advertising. At the

118

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

outset, the editors were "much

encouraged by a very considerable

number of communications from a

distance, as well as from our

immediate neighbors, all highly

approving our design."22 By

March of 1840, the editors

announce that:

We have from different quarters and from

different individuals, in

the last three months, had it suggested to us, that if

we could change the

form of the Peace-Maker, and make

it a weekly religious newspaper, its

circulation and patronage, and of course its use, would

be greatly ex-

tended.23

But the editors showed remarkable

fortitude in the face of

these public demands, and developed

three very good reasons why

such a luxury as a weekly was not for

them. In this same issue

the delinquent subscribers are warned:

"that as this is the sixth

number, we expect all the payments due

to be punctually for-

warded."24 Further, at the close of the eighth number

there is

an item captioned, "I Must Pay My

Debts," which may, or may

not, be taken as a hint. In any event,

the demise of the publica-

tion was not far distant.

In the year 1840 the West again called

William W. Bishop,

and definite knowledge of the

peregrinations of the Societies'

Press comes to an abrupt termination.

Internal evidence seems to

indicate rather strongly that the press

passed into the hands of

one John B. Peat; but such a conclusion

should not be pushed too

far for it is based on pure conjecture.

It is known, however, that

his imprints begin at this time, and that

the work he was doing

was exactly the same sort as that

carried out by the Bishop

brothers. It is further known, on the

authority of a son and

daughter of Robert H. Bishop, Jr.,25

that when William W. Bishop

turned westward for the second time he

did not take his printing

equipment with him, but left it in the

care of his brother, to be

disposed of to the best advantage. From

Peat's press came nu-

merous addresses before the various

Miami societies, the sixteenth

annual catalogue of the university, as

well as sermons by Presi-

dent Robert Hamilton Bishop. The most

important evidence of

22 Western Peace-maker (Oxford, Ohio, 1839-40), May, 1839, 91.

23 Ibid., March 1840, 274.

24 Ibid., March,

1840, 276.

25 Mr. Peter and Miss Helen Bishop, of

Oxford, Ohio. In fairness it should be

added that neither of them can recall

ever having heard their father speak of John

B. Peat. So far as they are concerned he

is a totally unknown character.

HISTORY OF PRINTING, OXFORD, OHIO 119

all, however, is the fact that while the

first eight issues of the

Peace-maker carry the name of William W. Bishop as printer, the

last bears that of Peat. But who he was,

where he came from,

and where he went after 1841, no one

seems to know.

Up to the present point, the course has

been reasonably well

charted. It is true that there are

numerous unanswered questions

for which one would wish a more complete

explanation. But, on

the whole, up to the time of the

appearance of the Peat imprints,

our knowledge of essentials is fairly

adequate. From now on,

however, we must seek our way through

more troubled waters

with fewer aids to guide us. From now

on, conjecture must nec-

essarily play an increasingly important

part, and our only alter-

native is to go by the best light we

have, and hope that our light

be not darkness.

In January of 1829, there appeared from the printing presses

in Hamilton, a publication known as the Christian

Intelligencer

and Evangelical Guardian, by an Association of Ministers of the

Associate Reformed Synod of the West.

This publication was

under the general editorship of David

MacDill, of Rossville and

Hamilton, was printed in those towns by

various hands, and as-

sumed some importance in the realm of

theological literature in

its section of the country. The fact

that the Intelligencer existed

over a period of eighteen years is ample

testimony to the fact that

it was no abortive journalistic

enterprise. It remained, however,

as a Hamilton publication until the

issue for March, 1837 (It was

a monthly.), when the editors announced:

The first number of the next volume will

be issued early in the en-

suing month. We can with confidence say,

that Mr. Christy, who has con-

sented to become publisher and

proprietor, will strive to give entire satis-

faction in his department. Hereafter all

orders for the work, and all com-

munications respecting the business department are to

be addressed to

David Christy, Oxford, Ohio, to whom all

payments are made for future

volumes....26

Accordingly, the April issue begins new

series number one,

of the eighth volume, and bears the

imprint of David Christy at

Oxford as the publisher, but the

printing, i. e. stereotyping, was

done at Cincinnati. However, with the

issue of June, 1837, the

26 Christian Intelligencer (Hamilton,

Rossville and Oxford, Ohio, 1829-47), March,

1837, 381-82.

120

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

printing responsibility was assumed by

Robert H. Bishop, Jr., at

the old Societies' Press, and the Intelligencer

became more than

ever an Oxford publication.

David (Cotton-Is-King) Christy, born in

1802, needs

no in-

troduction to students of Ohio Valley

history. Anti-slavery writer,

geologist, and publisher, he is known

chiefly for his efforts in the

colonization movement in Ohio. In 1848

he was appointed agent for

the American Colonization Society of

Ohio, and was instrumental

in inducing Charles McMicken of

Cincinnati, and others, in contrib-

uting toward the purchase of a tract of

land in Africa, lying be-

tween Sierra Leone and Liberia, for the

colonization of the free

colored laborer, this tract being known

as "Ohio in Africa." In

the interests of this cause he did much

lecturing and publishing,

even appearing before the Ohio State

Legislature. His most im-

portant book, however, was a direct

outgrowth of the agitation

over the Kansas-Nebraska Act, and the

attacks of the abolitionists

on slavery, and was entitled, Cotton

Is King; or the Economical

Relations of Slavery, which appeared in 1855. This essay went

through three editions and attracted

favorable comment. It was

followed in 1857 by a pamphlet, Ethiopia:

Her Gloom and Her

Glory. In his travels about the country as agent he became

greatly

interested in geology, and in later

years worked with considerable

success along that line. In 1867 he was

engaged in the prepara-

tion of a book on, Geology Attesting

Christianity.

Though the author of the sketch in the Dictionary

of Ameri-

can Biography, Mr. Reginald C. McGrane, creates the impression

that Christy was entirely a Cincinnati

man, it is nevertheless true,

as stated above, that he came from

Cadiz, Harrison County, Ohio,

to Oxford in 1837, where he was quite

actively engaged in the

publishing business until 1841.

With the issue of the Intelligencer for

December, 1837, the

publishing as well as the printing was

turned over to Robert H.

Bishop, Jr., in whose hands it remained

until the issue for April,

1839, announced:

The present number closes the 9th volume

of the Christian Intelli-

gencer. We are

authorized to state that Mr. John Christy, brother of David

Christy, has made an arrangement to

become our publisher, to commence

with the next volume. As his attention will be

exclusively devoted to it, a

HISTORY OF PRINTING, OXFORD, OHIO 121

confident hope is indulged that the

execution will be every way worthy of

the character and patronage of the Christian

Intelligencer. Having, with

this in view removed with his family to

Oxford, at the instance of his

brother, and with the expectation that

the work would continue to be

liberally patronized by the Associate

Reformed Synod of the West,

we hope there will be no decay of

exertion to sustain it. Within a few

months he may remove his office to

Rossville.27

By this time Robert H. Bishop, Jr., was

abandoning the print-

ing business so that thereafter the Intelligencer

was no longer is-

sued from the Societies' Press. As a

result the April, 1841, issue

announces:

The publisher of the Christian

Intelligencer has made arrangements

to remove his office to Rossville, from

which place the next number will

be issued. Among the advantages of the

proposed change it is hoped that

errors of the press can be more easily

prevented.28

The publisher referred to is, of course,

John Christy, so that

by 1841 both Christy families were

leaving Oxford. The Intelli-

gencer, it might be added, survived until May, 1847, at which

time

the editor, MacDill, took up work with

the United Presbyterian

and Evangelical Guardian.

One other publishing enterprise of David

Christy remains

to be discussed. On June 1, 1835, while

still at Cadiz, he began

the publication of the Calvinistic

Family Library, the purpose

of which was "to furnish the

standard works of Calvinistic di-

vines at the cheapest rate, and in such

form that all the numbers

issued in a year can be conveniently

bound up in one volume."29

Of this Library, Volume I,

numbers one to twenty-six, were is-

sued at Cadiz, from June 1, 1835,

to February 15, 1837, and the

only copy known to the writer exists in

the library of the Western

Reserve Historical Society. In the

spring of 1837, with the re-

moval of David Christy to Oxford, work

was begun on the second

volume, and in 1838, there was

published, Lectures on Theology,

by John Dick, published under the

superintendence of his son,

with a biographical introduction by an

American editor, printed

and published by David Christy at

Oxford, and stereotyped by J.

A. James and Co., at Cincinnati. It is a

sizable volume of five

hundred seventy-three pages, bound in

calf.

27 Ibid., April 1839, 576.

28 Ibid., April, 1841, 527.

29 Ibid., April, 1837, 45.

122 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

HISTORY OF PRINTING, OXFORD, OHIO 123

124 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND

HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

Here is, then, rather conclusive

evidence that both the Chris-

tys were actually themselves doing the

work of type-setting and

printing, and it is reasonable to

suppose that the materials that

have come down to us bearing their

imprints were actually com-

posed by them, though as previously

stated such stereotyping as

was done was evidently carried out in

Cincinnati.

To understand somewhat more clearly just

the relationship

that existed between these Oxford

printers and the house of

James, it is well to consider for a

moment the general principle

of the stereotype process, if a slight

but relevant digression will

be pardoned.

Though the origin of this process is

somewhat in doubt, its

invention is usually attributed to the

Edinburgh goldsmith, Wil-

liam Ged, who developed a basic

procedure of this sort sometime

during the first quarter of the

eighteenth century. Improve-

ments, however, came rather slowly, and

stereotyping was first

introduced into this country not until

1813, and the first American

book to be so printed was the New

Testament that came from the

press of David Bruce in 1814. Briefly

explained, the process of

stereotyping consists in making an

impression of the type page

with an especially prepared thick paper.

This paper, called a

flong, is made by pasting together

several sheets of strong tissue

paper and a thick blotting-like paper

with a prepared paste. This

sheet, while in a soft pulp state, is

laid on the form, covered with

a felt blanket, and the whole put into a

strong press, heated by

steam or hot air, and allowed to set and

dry. When the matrix

thus formed is hardened it is removed

and placed in the casting

box, and the plate made by pouring the

casting metal in. A stere-

otype plate is obviously inferior in

quality to the electrotype, both

because of the rather unsubstantial

nature of the paper matrix

and the inferior quality of the

stereotype metal. It has two ad-

vantages, however, and these are speed

and economy of produc-

tion, so that even today it is still

used in newspaper work. From

this cursory explanation it would seem

logical to assume that after

the type had been set up in Oxford, the

Christys themselves very

probably proceeded with the making of

the papier mache matrix,

which, after hardening, was sent to

Cincinnati to be cast. Of

HISTORY OF PRINTING, OXFORD,

OHIO 125

course, once the matrix had been made

the type could be re-dis-

tributed and the setting up of another

portion of the book under

preparation could be commenced. In this

manner the Christys

would be enabled to print without

difficulty two volumes as large

as the Gibbon, with a comparatively

small amount of type. After

the plates had been cast at Cincinnati,

it is quite likely that they

would be sent to Oxford for the

completion of the printing

process. By and large, with the

inefficient means of communica-

tion available at the time, this process

must have been a rather

long and tedious one, but it was about

the only way that men with

such limited facilities as Oxford

afforded could undertake such

ambitious projects with any assurance of

success.

Also during 1839 there was working in

Oxford, one Charles

Smith, bookbinder, who had had work done

by the cabinet-

maker, Hills, from whom were obtained,

among other things,

pressboards and a table. This account,

it is noted, was "settled

through J. James, Cincinnati,"

which suggests a rather close re-

lationship between Smith and James, and

a possibility that the

former might have been doing some of the

binding of the vol-

umes under discussion. But our specific

knowledge of Smith is

limited entirely to the entry in the

Hills account book, and he is

as vague and shadowy a figure as is

Peat.

In conclusion, what of the importance of

the documents that

have been herein reviewed from the

standpoint of typography?

As specimens of the printer's art, their

position is, of course, of

little consequence. There was no great

variety of type faces in

the fonts of the Societies' Press, and

the small type used, set solid

or only slightly leaded, make the pages

of these publications un-

inviting indeed. But this is not said in

disparagement. Typog-

raphy of this sort is typical of the

entire period, no matter where

it was produced. With the dawn of

printing in the Western hemi-

sphere the early designers of the book

had to compete with the

excellent work of the scribes, and thus

these cradle books com-

pare favorably in typographical

achievement with contemporary

illuminated manuscrips. But after 1500,

such competition was

no longer necessary, most of the scribes

being dead, and the stand-

ard of printing was thus lowered to a

remarkable degree. This

126 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND

HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

downward movement was given added

impetus with the coming

of the industrial revolution. Paper was

robbed of its surface,

strength, and durability; inks were

inferior; bookbinding was less

substantial and beautiful; and type and

ornamental designs were

at their lowest ebb. It was in the midst

of this era of decadence

that the Societies' Press was operating,

for the renaissance in the

printer's art that we enjoy today was

largely the result of the

work of William Morris at the Kelmscott

Press during the 1890's.

The rigid Calvinistic atmosphere of

Oxford in the early half

of the nineteenth century was certainly

not encouraging to the

production of an iconoclast in artistic

book design. As Miami's

President Upham has wisely said:

Cultivation of the arts seems to have

been less common in Miami's

past than that of the spiritual life.

Professor McGuffey knew and loved

good poetry and forensic prose. Dr.

Bishop unwittingly posed for the

first great work of sculpture executed

by Hiram Powers. He and David

Swing had rare taste in architecture, as

evidenced by the homes they built

adjoining the university campus. The

prospect of the rolling wooded hills

to be seen from the tower must always have

served as an inspiration. But

the total impression is rather dull, and

we cannot forget that someone,

fortunately unknown, was responsible for

the castiron porches on the

Main Building.32

Certainly it is not because of any

artistic achievement that

these publications merit

consideration. But they are far from

being without value, for they present in

a concrete tangible form

the spirit of the age that produced

them. They are the very em-

bodiment of the limitless optimism of

the frontier, the urge to

create, to give to the world something

of importance, the impulse

to achieve. Their promulgators must have

known, if they had

pondered the matter but for a moment,

that their efforts would be

largely in vain. Yet, like Edmond

Rostand's immortal Cyrano:

What say you? . . . That it is useless?

. . . Don't I know?

But valiant hearts contend not for

successes

It's nobler to defend a hopeless cause.

Herein, for us, lies the value of these

documents: that they

recreate the spirit that founded Miami,

and the westward flow of

American cultural ideals that it

represents, and that they help to

bring one a step closer to an

appreciation of the indomitable

courage of the pioneer.

32 Alfred H. Upham, Address to the Faculty of Miami

University, at the Opening

of the Academic Year 1929-30 (Oxford, Ohio, 1929), 10.

HISTORY OF PRINTING, OXFORD, OHIO 127

It must be confessed that in tracing

this sketch there have

been many unanswered questions. One

longs to know more,

much more, of that old press itself,

where it came from and

whence it went, and of, the men who

manned it. Let it be hoped

that the future will be more generous in

yielding up the secrets of

the past. But for the present, at least,

one has reached the end

of the trail, and perforce must be

content, for, though one may

cry out with Goethe's Faust:

Wohin der weg?

one receives in return naught but

Mephistopheles' unreassuring

reply:

Kein weg--Ins Unbetretene.

Vol. XLIV--9

AN EDDY IN THE WESTERN FLOW OF AMERICAN

CULTURE

The History of Printing and Publishing

in Oxford, Ohio,

1827-1841

By

JESSE H. SHERA

(103)

(614) 297-2300