Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

ORIGIN AND SIGNIFICANCE OF PENNSYLVANIA

DUTCH BARN SYMBOLS *

By AUGUST C. MAHR

On a great number of Pennsylvania Dutch

barns, there are

geometrical ornaments painted on the

outside walls; ornaments

which, as a rule, show some sort of star within a circular disk

(Figs. 1, 2, 8, 10b). They occur most

frequently in Berks and

the neighboring counties; less

frequently, in other parts of Penn-

sylvania; and, locally, even in Ohio and

other states of the Union

where Pennsylvania Dutch farmers have

settled.

Due to Ohio's close proximity to

Pennsylvania, as well as to

its importance, in early frontier days,

as both a temporary and

permanent place of settlement for

eastern farmers venturing west-

ward, it is in Ohio that not only barns

of Pennsylvania Dutch

structure are more frequently found than

anywhere else outside

of Pennsylvania, but here one may also

see the barn symbols that

are so striking a characteristic of the

Pennsylvania Dutch counties

mentioned above.

The Pennsylvania Dutch barn in question

is of the so-called

Swiss bank-barn type. It means that it

is erected along an em-

bankment in such a way that its main

entrance door leads to the

heavily planked floor of its wooden

upper story. This floor is at

the same time the ceiling of the lower

story formed by the stone

base structure which contains the

stables for the livestock and is

* This study grew out of a paper read

before the Anthropology Section of the

Ohio Academy of Science, at its annual

meeting, in May, 1943, at Columbus, Ohio.

The writer is glad to express his

gratitude to Professor Edgar N. Transeau of Ohio

State University for the photographs taken in

Pennsylvania, of barns shown in

these pages; to Dean Carl F. Wittke, and Professor Clarence Ward, both of Oberlin

College, for photographs and scholarly

aid; to Professors John W. Price, and Wilmer

G. Stover, both of Ohio State

University, and to Dr. James H. Rodabaugh and Mrs.

Margaret Stutsman, of the Ohio State

Archaeological and Historical Society, and Mrs.

Mary Jane Meyer, of the Ohio War History

Commission, for helpful field-work; to Dr.

Jean Weltfish, of Columbia University,

for valuable bibliographical advice; to the Grad-

uate School of Ohio State University for

generous help in securing the illustrative ma-

terial; and, last but not least, to the

publishing houses, in London, of A. Zwemmer,

Macmillan. & Co., and Methuen &

Co., Ltd., for their permission to reproduce pictures,

from works published under their

imprint, as illustrations of this article.

(I)

|

2 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY |

|

|

|

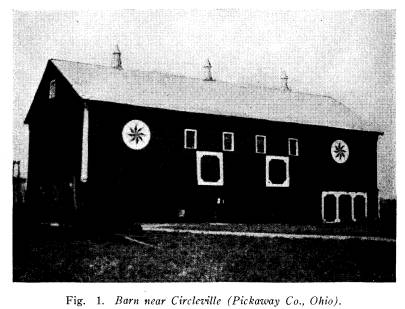

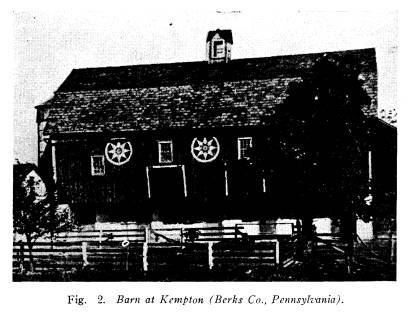

accessible through doors on the lower level of the slanting terrain. As a rule, the barn, in its full length, carries a wooden fore-bay which projects from the upper story and overhangs the outside wall of the stables to the extent of about six to eight feet. Fre- quently, however, the barn is built on level ground with a ramp leading to the upper story. In Pennsylvania as well as Ohio, these barns are usually red, often with white arches over the white- framed fore-bay openings. Wherever barn symbols are found, they are painted in various colors on the fore-bay, or the back, or the gable sides, or on all four walls of the wooden superstructure. The one or other barn with such star-shaped symbols on its outer board walls is found in practically every region of Ohio where Pennsylvania Dutch from Berks County or its neighbor- hood have settled. The writer has selected at random a few lo- cations where they are in evidence today: Route 188, 1 mile east of Circleville, Pickaway Co.; farm of Mr. S. Paul Valentine (red barn with two black-and-yellow eight-pointed stars |

|

BARN SYMBOLS 3 |

|

|

|

in white disks on fore-bay). This is, without a question, one of the finest Berks County barns in Ohio. It was erected, ca. 1840, by a man of the name of Berger, from Pennsylvania. With each re-painting, the symbols, that are as old as the barn, were re-touched in black-and-yellow in order to retain the original appearance of the building (Fig. 1). Route 23, between Columbus and Delaware, a mile north of Stratford, Delaware Co. (red barn with three six-pointed stars on fore-bay). Route 203, between Delaware and Radnor, Delaware Co. (red barn with three six-pointed stars on fore-bay, and one eight-pointed star in each gable). The barn is known as "the old Sharadin barn." Route 33, between Logan and Rock Bridge, Hocking Co., 2-3 miles south of Rock Bridge (red barn with a star in each gable). Route 73, between Waynesville and Franklin, Warren Co. (barn with three sky-blue five-pointed stars on each gable side). Route 18, 2 miles north of Republic, Seneca Co.; farm of Mr. L. J. Neikirk (red barn with white curved club-armed swastika1). Route 53, 7 miles north of Upper Sandusky, Wyandot Co.; farm of Mr. R. R. Everhart (red barn with white five-pointed star in white ring). Date on barn: 1916. 1 Cf. infra, page 22. |

4

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

Despite the considerable number of

additional places where

such barn symbols occur in Ohio, it is

an undeniable fact that

they are gradually passing out of

existence, the main reason be-

ing that their magic symbolism is

rapidly dropping into oblivion

under the leveling effect of the changed

environment. Although

to a much lesser degree, the same holds

true for the Pennsylvania

Dutch countryside proper: about fifty

years ago practically no

barn in Berks County was without such

symbols; today they have

become much rarer.

By far the majority of Germans that

settled in Ohio up to

1820 did not come from Germany directly

but from Pennsylvania2

and, in particular, from Berks County.

The organized Moravian

(and other sectarian) colonies excepted,

settlers from Berks

County are frequently listed in early

Ohio local records. Trepte

mentions several German families from

that county who, in 1796,

founded and named "Miamisburg"

(Montgomery Co.).3 About

1810, the settlers of Cermantown

(Montgomery Co., Ohio), al-

most without an exception, were Germans

from Berks and Center

Counties.4 Other Pennsylvania counties in the

neighborhood of

Berks that appear in the records,

especially of Montgomery

County, Ohio, as having contributed

German settlers, are Lancas-

ter County,5 York County,6 and

Lebanon County.7

Pennsylvania Dutch immigration into Ohio

after 1820--this

being approximately the last year

covered by Trepte's excellent

study--has not yet been sufficiently

explored to furnish reliable

data. Yet, it is definitely certain that

within the next few decades

after 1820, a great number of Germans

from Pennsylvania and,

particularly, from Berks and the

neighboring counties established

themselves in various parts of Ohio.8

It is an outstanding characteristic of

the Pennsylvania Dutch

2 TDO, 174 ff. (Explanations of this and

other abbreviations will be found at

the end of this article.)

3 Ibid., 308; see also note (a): "This [Berks] was one of the

counties that gave

Ohio most of her Pennsylvania

Dutch" (Transl., A. C. M.).

4 Ibid., 312 and

313, n. (a), (c), and (g).

5 Ibid., 309 and 322.

6 Ibid., 308 and 323.

7 Ibid., 313, n. (e).

8 For instance, the writer knows, from

family records, that a group of families

which almost might be called a

"colony," about the middle of the last century, moved

from Berks and Dauphin counties,

Pennsylvania, to Delaware County, Ohio, where

they are still in evidence.

BARN SYMBOLS 5

that they have emigrated from

Pennsylvania in groups rather than

individually and that, thereby, they

have preserved a great many

of their traditions and general habits

of life in the new environ-

ment. What, therefore, in the subsequent

pages is said about the

Pennsylvania Dutch and their barn

symbols in Pennsylvania, ba-

sically applies also to those in Ohio or

other locations where they

have settled. This study, however, is

concerned with the funda-

mental facts about these symbols rather

than with their present-

day application.

The barn symbols are popularly called

"Hex Signs," that is,

protective magic against witchcraft. The

"Dutch" in Pennsylvania

and, in particular, the owners of barns

that bear such marks as-

sure the inquisitive stranger, however,

that the object of these de-

signs is exclusively decorative.

Obviously, they are sensitive about

their "Hex Signs," especially

so if that term is used, and even the

most tactful of investigators soon finds

out that he has been han-

dling a "hot potato."

A similar guardedness in this matter

prevails among some

authors of books on Pennsylvania Dutch

life and customs, es-

pecially among those of native stock who

are sensitive of the feel-

ings of their relatives and friends. It

is not often that one finds

a writer, himself of Pennsylvania Dutch

extraction, expressing

himself with the refreshing frankness of

Mr. Weygandt who

writes: "The symbols are supposed

to keep lightning from striking

the barn that has them painted on its

wooden sides, and to prevent

the animals housed in the barn from

being bewitched, or 'ferhexed'

as we say in the vernacular."9 Some

of the native authors touch

upon the subject lightly in smiling

embarrassment. Others beat

about the bush with vague phrases of

apology for what might look

like superstition unbecoming an

otherwise quite sober-minded

group of Americans. One of the authors

has even tried to remove

the stigma of superstition by proving

that, far from being "Hex

Signs," all the various barn

symbols are "the Lilies of Ephrata"

in disguise.10 The

beautifully illustrated book provides edifying

9 C. Weygandt, The Red Hills, . . .

(Philadelphia, 1929), 126; similar state-

ments, ibid., 10 f., 65 f.

10 J. J. Stoudt, Consider the Lilies How They Grow. An

Interpretation of the

Symbolism of Pennsylvania German Art (Allentown, 1937).

6

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

reading to the fancier of local

sentimental literature, but it helps

in no way to solve the question about

the origin and meaning of

the barn symbols.

What is needed here, is an unbiased and

unemotional ap-

proach. The key-point is that the

Pennsylvania Dutch farmers,

particularly in Berks County and its

neighborhood, always have

been, and in many respects still are,

not merely farmers but peas-

ants in the best European sense. Not

everyone who tills the soil

and raises livestock is a peasant.

Whereas the mere farmer's ac-

tivities are based on cold empiric facts

that may be learned in

agricultural schools, the peasant's life

is governed by fixed cus-

toms, if not ritual, peculiar to his

particular group and origin.

These customs attend all his chores in

the fields, in the cattle-barn,

in the house, and rule his domestic

relations, his dealings with his

fellows, his dress, his habits of eating

and drinking, his recrea-

tions, in short, every step of his

earthly pilgrimage from the cradle

to the grave. Most of these rules and

customs reach down into

times immemorial. They contain many

taboos that today are no

longer obvious, and they include innumerable

symbolic actions and

signs traceable to prehistoric magic as

well as to pagan mythology

and ritual.

The Pennsylvania Dutch are quite unique

in this country, in

that they have tenaciously clung to a

great many of the peasant

traditions which their ancestors had

brought with them from the

Old Country. Again and again, they

migrated in larger and smaller

groups from the same parts, mostly the

Upper Rhine, the Rhenish

Palatinate (Rheinpfalz) and

Switzerland, but also from other

West and South German states. They are

further unique in that

they maintained their communal form of

life in the New World,

both to their own benefit and that of

William Penn and his Quaker

associates. The greater number of these

so-called "Palatines"

(Pfalzer) landed, mostly in the harbor of Philadelphia, between

1710 and 1775.11

This adherence of the Pennsylvania

Dutch, for more than two

11 Cf. R. B. Strassburger, Pennsylvania German Pioneers, 3

vols. (Norristown,

1934). This is a publication of the original lists

of arrivals in the port of Phila-

delphia from 1727 to 1808.

BARN SYMBOLS 7

centuries, to the native peasant customs

of their German fore-

fathers can only be explained by the

fact that they did not lose

their original group consciousness after

they had settled in

America. Instead of being readily

absorbed by the new environ-

ment, as were the countless individual

settlers from other German,

and non-German, peasant communities of

Europe, the Pennsyl-

vania Dutch possessed in the peasant

traditions of their old home-

land a cultural force that was

sufficiently strong to shape their

new environment into a peasant community

of distinctive charac-

ter. In achieving this, they were

substantially aided by a very

happy coincidence: the amazing

similarity between their old home-

land and Pennsylvania. This similarity

not only extends to the

physiognomy of the landscape but also to

climate and soil condi-

tions. There is hardly a region in the

Keystone State, which has

not an almost exact counterpart

somewhere in southwestern Ger-

many. Such exceptionally good fortune

allowed them to continue

in their new home, with a minimum of

adjustments, where they

had left off in the Old Country.

Nothing, in the new environment,

was so essentially different as to

estrange them from their native

peasant views and practices.12

Strangely enough, this important basic

fact has been ignored

by a recent writer about "the Dutch

country."13 He has the feel-

ing that there is a derogatory connotation

implied in the term

"peasant" since to him

"peasant" and "serf" are synonymous. His

definition of "peasantry"

makes no allowance for its most distin-

guishing, cultural feature:

namely, the age-old devotion of the

peasant, steadfastly carried from

generation to generation, to fixed

customs that govern every phase of his

life. On the grounds of

this omission, Mr. Weygandt denies the

peasant character of the

rural Pennsylvania Dutch community.

Indeed, his particular no-

tion of what constitutes

"peasantry" leaves him no other choice.

One may grant some of his prerequisites

"for the develop-

12 That is exactly the reverse of what happened to the Holland Dutch immi-

grants, who eventually became the

"Boers" in South Africa. Citing S. Cloete's The

Turning Wheel, R.

Peattie (Geography in Human Destiny [New York: Stewart, 1940],

34 f.) demonstrates how the totally

different environment transformed these stolid

Dutch peasants into impassioned, adventuring

pioneers, an entirely novel type that

retained next to none of its ancestral peasant

features.

13 C. Weygandt, The Dutch Country (New

York, 1939), 109 f.

8

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL

AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

ment of a peasantry," such as

"a long established civilization,"

"stability in social

conditions," and "a very slowly changing order

down the years." But peasantry certainly does not include

"a

rigid caste system; recognized and

unchallenged privilege; a frank

and ungrudging acknowledgment on the

part of the many that a

chosen few are set above the

crowd." It does not agree with the

facts of history that "there must

be all these conditions or a peas-

antry cannot be."

The free peasants of Switzerland, for

example, have main-

tained for more than six hundred years

their model democratic

republic, with its rural citizenry

adhering, as staunchly as ever, to

their magnificent old peasant culture.

For another example, there

is the free peasantry of Dithmarschen

who, in 1500, victoriously

defended, in the battle of Hemmingstedt,

their liberty against the

combined nobles of Denmark and Holstein.

True, there are re-

gions where the peasants used to live in

a condition of thraldom;

but there are surely as many where, for

ages, they have been liv-

ing as their own masters on their own

soil. These well-known

facts certainly do not bear out the

statement: "Above all there

must be laborers on land of which they

do not themselves own a

foot for peasantry to be. A peasantry

presupposes an agricultural

society, in which the laborer works not

for himself, but for a land-

owner. A peasantry cannot exist in a

country in which a landlord

class does not exist, in which authority

and position and money

do not persist in a family generation

after generation."

Of course, a peasantry of Mr. Weygandt's

definition could

not exist in the United States, but that

does not alter the fact that

the Pennsylvania Dutch deserve credit

for having preserved, right

in our midst, what according to all

accepted standards is a true

German peasant culture. The majority of

those immigrants from

the Palatinate and Switzerland, who came

to Pennsylvania by the

shipload throughout most of the 18th

century, were peasants in

the best possible sense. Indeed, a great

many of them brought to

this country more than enough money for

the purchase, and sub-

sequent cultivation, of large tracts of

fertile farm lands. Had

they been, in their German homeland,

down-trodden day-laborers

BARN SYMBOLS 9

or serfs, they would never have been the

model farmers that they

are still today, nor would they have

possessed the moral dignity

and cultural vigor prerequisite to

maintaining themselves, in the

New World, as a close-knit and unique

peasant community.

The barn symbols here discussed occur in

America ex-

clusively with the Pennsylvania Dutch

peasantry. Hence one

may expect some light on their origin

and significance from anal-

ogous occurrences in German peasant art

which, like the peasant

art of any part of Europe, is a

depository of prehistoric and pagan

values otherwise long obliterated.

Of the unlimited number of different

ornamental patterns

that exist on earth, only a very few

have been designed as vessels

for symbolic concepts. Most of the

symbolic ornaments encoun-

tered in Pennsylvania Dutch peasant art

and, in particular, as

barn signs, are stars with five, six,

eight, or more, points (Figs.

1, 2, 8, 10b), but there also occurs the

one or other design that is

not a star, as, for instance, the

Swastika (Fig. 10a).

As one examines the general distribution

of these symbolic

patterns one easily sees that their use

by the Pennsylvania Dutch

is just one instance among many others.

Up to the present day,

and regardless of period styles and

local tendencies in the dec-

orative arts, they occur in the peasant

art and craft, not of Ger-

many alone, but of all European

countries without an exception.

Naturally, the question arises: where

and why have they orig-

inated? And next: why and how have they

spread the way they

did?

There is ample evidence14 that

these various symbols that oc-

cur in European peasant art, inclusive

of the Pennsylvania Dutch

area, have their origin in a Cult of the

Sun that during the Bronze

Age was practiced "in Ireland on

the west and throughout the

greater part of Europe."15

It is more than probable that the cultic

initiative came from

the Mediterranean, and that the symbols,

along with the Sun Cult,

were carried over well-established trade

routes all throughout

Europe. Some of these routes, the

earliest in fact, were the sea

14 Cf. infra, page 15 ff.

15 COPA, 254 ff.

10

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

lanes by which the Cretans and

Mycenaeans transported their fin-

ished products, mainly bronze objects

and pottery, not only along

the entire Mediterranean coast but also

"to Great Britain for cop-

per and tin; to Ireland for gold; they

also visited the coasts of

the English Channel, and the North Sea;

and traded for amber

with the inhabitants of Denmark."16

By far the greater exchange of goods

took place, however,

over cross-continental trade routes. Two

of them led to the amber

deposits of the North: one ran from the

Adriatic over the Bren-

ner Pass, down the river Inn to the

Danube, and from there,

across the Bohemian Forest, down the

valley of the Moldau and

along the river Elbe to its mouth. Another

started at the Gulf of

Trieste, ran northeast to Laibach and

Graz and descended to the

Danube. "The tributary March was

then ascended and, after

crossing Moravia, the route passed

through Silesia and followed

the Oder to the [Baltic] coast." A

branch route "diverged from

this one at Posen and followed the

Vistula to Danzig."

"A third less important route led

to the North Sea from the

Mediterranean, by way of the Rhone and

the Rhine."

"Besides these main 'Amber Routes'

there were routes across

Alpine passes to France and Germany

which followed the Rhone,

Loire, Seine and Rhine, and routes to

and along the broad Danube

Valley by way of the Inn, Save, and

other tributaries."17

Considering the indubitable existence of

the Sun Cult among

the people who utilized these trade

routes both by land and sea

for over a thousand years previous to

the dawn of history, one is

not surprised to find the symbolic

emblems of that Cult spread,

even today, among the folk of the entire

area that was once trav-

ersed by these trade channels. The most

significant of all was the

Danube Valley route, not only because of

its importance as a di-

rect connection between Southeastern and

West Central Europe

but also because it was traversed on a

great number of points by

the "Amber Routes." The most

careful and methodical explora-

tion of Bronze Age sites, throughout the

entire European conti-

16 Ibid., 261 f.

17 The above survey of the Bronze Age trade routes of Europe has been

condensed,

and partly quoted, from COPA, 256

ff. where also a good map is found (page 258).

BARN SYMBOLS 11

nent, over many decades, has proved that

"the Sun Cult must have

been in honor throughout Europe for at

least 1500 years, and was

consequently one of the most enduring

religions the world has

known."18

Beyond being graphic representations of

the powers ven-

erated, the symbolic signs in

practically every known religion that

possesses such, are widely used for

magic purposes. The people

carry them on their bodies as protective

amulets, they apply them

to their houses, stables, and barns,

furniture and household uten-

sils, either to ward off evil influences

or to enlist the aid of ben-

eficent powers in securing fertility and

good health for themselves,

their livestock and their crops. This

being true today, in Christian

countries, it must have been even more

so in prehistoric times

when religion and magic were one and the

same.

It has been argued that designs of this

nature may have orig-

inated independently in various parts of

the earth. That may be

true for a very few and very primitive

ornamental patterns, such

as straight and curved lines, both

single and parallel; zigzag and

wavy bands; cross-hatch; triangles,

quadrangles and circles. It

cannot apply, however, wherever a symbolic significance attaches

to the ornament. Once a design has

acquired the quality of sym-

bol, this quality inevitably functions

as the vehicle by which the

design as such is carried from place to

place. This elemental in-

terrelation remains constant, regardless

of modifications that both

the symbolic meaning and the design

itself may have undergone

during their wanderings throughout the

ages. It also explains

why today these designs are

promiscuously and interchangeably

applied as propitious symbols, while

their original function, magic

or ritual, has long been obliterated or,

at best, can be but vaguely

discerned through the veil of time.

No matter what amount of migration and

political re-group-

ing has taken place on the continent,

during the Early European

Iron (Hallstadt) Age and the subsequent

eras of history, the

ancient symbols have continued in use

among the European peas-

antry, up to this day. This proves

indirectly that all participants

18 COPA, 255.

|

12 OHIO ARCHAOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY |

|

|

|

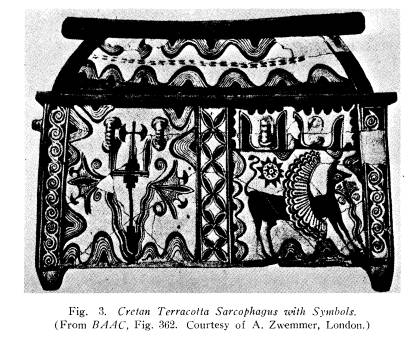

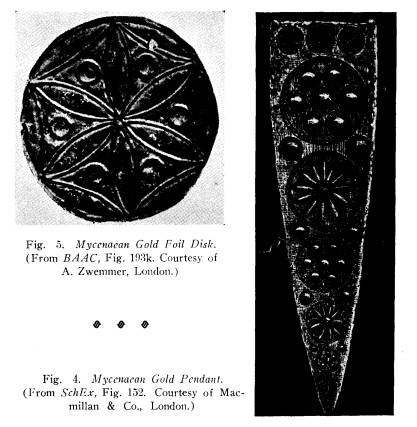

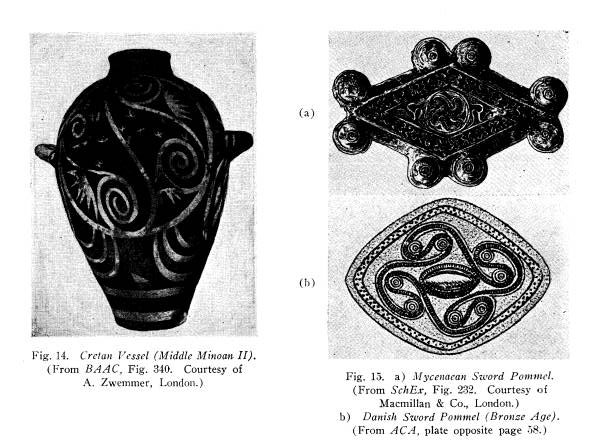

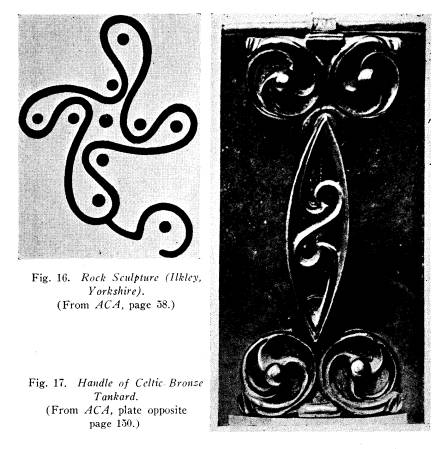

in such migrations and political re-shufflings, invaders and invaded alike, possessed the identical sub-stratum of magic concepts and were unaffected by subsequent religious creeds of a higher spiri- tuality successively superimposed upon them. It is still in this magic sub-stratum, unchanged throughout the ages and apparently unchangeable, that even today all popular credences are rooted. For the validity of this statement it matters not what magic is used, but that magic is used. The first dating of the application of such symbolic designs in the European Bronze Age becomes possible through their oc- currence in the Aegean Culture of the Eastern Mediterranean.19 They are found on the Island of Crete, and at Mycenae, and some even in pre-Aegean cultures of Western Asia. Figure 3 shows a star-shaped symbol on a Cretan terracotta sarcophagus (of ca. 19 For the dating of the Bronze Age, cf. 0. Montelius, "Bronzezeit," in Reallexikon der Vorgeschichte, ed. M. Ebert, Vol. II, 925; quoted COPA, 208. |

|

BARN SYMBOLS 13 |

|

|

|

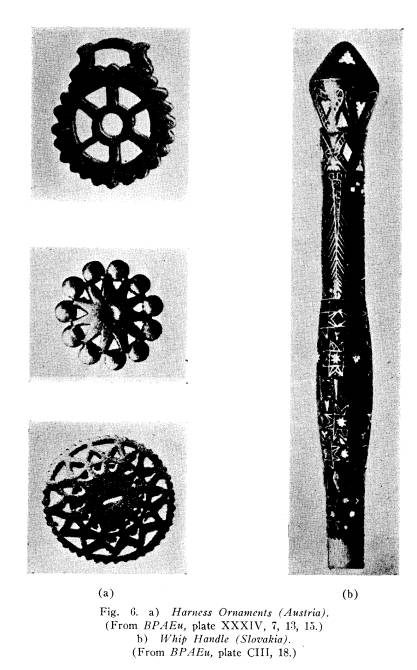

1300 B. C.); Figure 4 represents a gold pendant with many- pointed stars, probably used as an amulet. It was found, by Schliemann, at Mycenae, and it is to be dated at ca. 1550 B. C. Of the same provenience, date and magic function, is the gold-foil ornament shown in Figure 5, whose design is the "six-petaled flower-star"20 so familiar to all students of folk art. Evidently all three of these star-like designs are symbols of the sun. It appears that all of them, especially the latter, sec- ondarily and much later, acquired some bearing on fertility, for 20 The writer has adopted this term for the sake of convenient description al- though the design surely was never meant to represent a flower. |

|

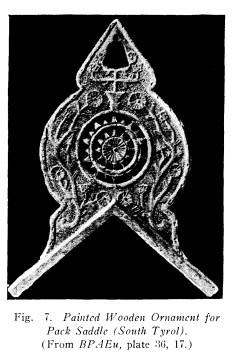

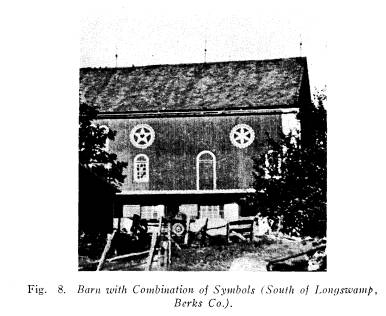

BARN SYMBOLS 15 they are almost universally found, alone or in combinations, on peasant utensils pertaining to the care of livestock, in particular, of horses (Figs. 6 and 7).21 |

|

The connection of the sun symbol with the horse is primary, that with other livestock, secondary and by anal- ogy, as it were. Danish and Irish Bronze Age findings prove that the horse itself figured as a symbol in this early Sun Cult. In Denmark there was discovered "an en- graved bronze disk six inches in diameter, cov- ered with gold foil, mounted on a wheeled carriage drawn by a horse." Similar disks found in Ireland show a design almost identical with that on the Danish disk. "The date of this sun chariot is about 1300 |

|

|

|

B. C. The Irish disks have lugs on the margin exactly as in the Danish specimen, the lower one for fastening it to the axle and the upper one for holding the reins."22 The discovery of two more horses, fragments of a ceremonial carriage, and of another sun disk prove beyond a doubt the age-old connection of the horse with sun worship, later fixed in the familiar Graeco-Italic myth of the sun god traveling across the sky in a chariot drawn by horses. Although in northern and central Europe no such later 21 Further illustrations: from Sweden, in HPASw, Figs. 189, 192, 196; from Tyrol, in HPAAu, Figs. 138-40; from Northern Italy, in HPAIt, Figs. 341-3, 366-8, 373-4. 22 COPA, 254. |

|

16 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY formulation seems to have originated (or, if originated, was superseded by other religious notions), yet the persistent oc- currence, in European peasant art, of sun symbols in connection with horses shows the enormous surviving power of the primeval concept. |

|

|

|

As stated above, it appears that the initiative toward this widespread Sun Cult came from the Aegeans, and that the Cult itself, together with its symbols, traveled along the various cross- continental trade routes, from the coastal trading posts of the Aegeans, to practically all parts of Europe. Indirect evidence for this comes from the fact that symbolic objects pertaining to other Aegean cults were likewise found at various inland points of Europe while the cults themselves have left no traces. Several copper specimens of the typically Cretan symbolic Double-Ax, found in France and Germany, "with a perforation too small to |

|

BARN SYMBOLS 17 |

|

|

BARN SYMBOLS 19

take an actual shaft, seem to mark an

early trade route," for "it

is likely, too, that this sacred symbol

was invested with an ex-

change value."23

Moreover, from the Copper Age until far

into the Early Iron

(Hallstadt) Age, there occur, especially

in Ireland, but also else-

where, crescent-shaped personal

ornaments very similar to those

luniform necklaces of embossed gold foil

found in Mycenaean

tombs.

It matters little whether they are to be interpreted as

moon symbols or as horns of the Sacred

Bull whose worship was

linked, on the Island of Crete, with

that of the Double-Ax.

Doubtless they were cultic symbols, and

their occurrence in cen-

tral and western Europe is surely due to

Aegean influences having

filtered in from the coastal trading

posts. A probable reason for

the universal acceptance of the Sun Cult

may have been its singular

appeal to the inhabitants of the

northern moderate zone. Its sym-

bolic "astral representations,

especially the solar disk or forms

derived from it"24 have been continually used for magical pur-

poses from the earliest times to the

present day.

The frequent combination of the

"six-petaled flower-star"

with some other solar symbol on European

peasant utensils per-

taining to horses and cattle25 is

also found on a number of Penn-

sylvania Dutch barns, as is shown in

Figures 8 and 10b.

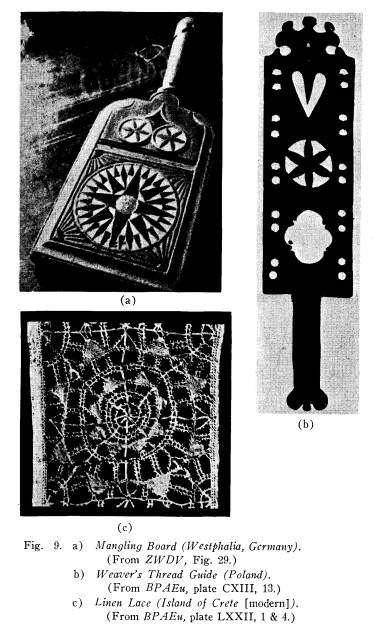

Similar combinations also occur, all

over Europe, on various

kinds of objects used by the peasantry

in the processing of flax

and wool, in the spinning and weaving of

linen, in the making and

laundering of linen goods, particularly

on distaffs, weaver's tools,

mangling boards, laundry beetles, etc.,

and they are even found in

the patterns of lace (Figs. 9a, b, c).26

Evidence for the prehistoric connection

of magic sun symbols

with spinning is found in the occurrence

of the swastika, both

angular and curved, on a great many

spinning whorls unearthed

by Schliemann on the site of ancient

Troy (3rd and 4th city).27

23 CDoEC, 34, 258, 313 (Map IV); see also supra, Fig. 3,

left half.

24 COPA, 298.

25 Supra, page 13

ff.

26 Further illustrations: from Sweden, Lapland, and Iceland, in

HPASw, Figs.

143-7, 149, 152, 155, 158, 159, 173-5,

177, 179, 180; from Russia, in HPARus, Figs.

188-202; from Lithuania, in HPARus,

Figs. 527-31; from Italy (Abruzzi), in HPAIt,

Fig. 362a.

27 Numerous illustrations in

Schliemann's Ilios, some of which are reproduced

in WSw, Figs. 64, 69, 78, 101.

BARN SYMBOLS 21

Besides, the above-mentioned combination

of symbols is fre-

quently used on cradles, beds, salt

containers, spoons, spoon racks,

and other implements of the peasant

household.28

The heart-shaped figures, occasionally

combined with any of

these symbols, may belong to a later

stratum of symbolism, al-

though certain heart-shaped ornaments do

occur on ancient Cretan

pottery.

The "six-petaled flower-star,"

evidently as a pre-Christian

sign of immortality, appears as the

predominant symbol on grave-

posts in Bosnia.29

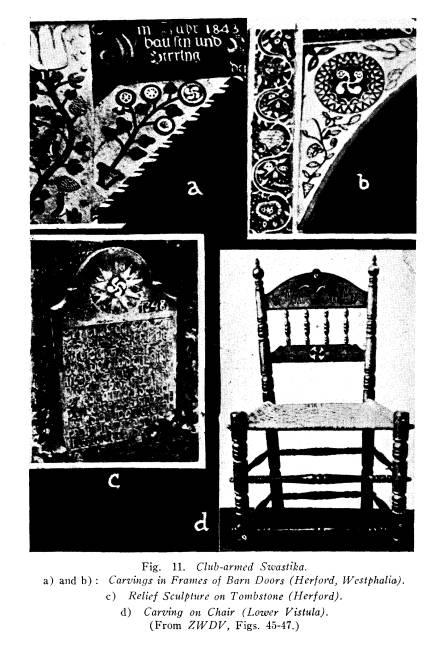

In some parts of the Old Saxon region (Nicdersachsen,

Ger-

many), stars, in combination with other

symbols, are frequently

painted on, or carved into, the frames

of barn doors (supra, Fig.

11a, and ZWDV, Fig. 22).

Also with the Pennsylvania Dutch, these

symbols, apart from

their use as barn signs, are applied to

all kinds of utensils of the

rural household.

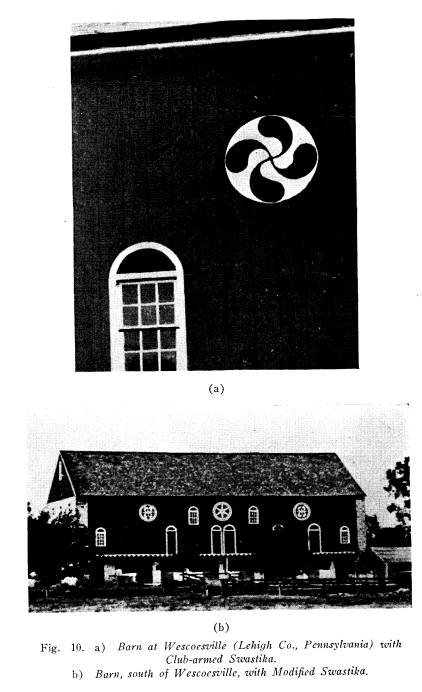

Another symbol used by the Pennsylvania

Dutch, both on

barns and otherwise, is the swastika;

not, however, the familiar,

angular, form but the swastika with

curved club-shaped arms such

as found on a barn at Wescoesville

(Lehigh County) (Fig. 10a).

Another barn, about one mile south of

Wescoesville, on the road

to Macungie, shows a variant: instead of

all four arms bending

in the same direction, here both the

upper and the lower pair of

arms are curved towards each other (Fig.

10b). Although this

modification of the symbol is likewise

of great antiquity (cf. su-

pra, note 27), it may be regarded, in the present case, as

merely

a local variant. That is all the more

likely since other variations

which are purposely fanciful also occur

as barn symbols in south-

eastern Pennsylvania.

The pure form of the curved club-armed

swastika is likewise

found in other parts of the Pennsylvania

Dutch area, both as a

barn symbol30 and applied to

other objects. An elaborate piece of

needle-work "made in 1826 by an

emigrant from the Palatinate"31

28 For illustrations see the standard

works on peasant art, as previously cited.

29 HPAAu, Fig. 506.

30 American Architect, Vol. CLI (1937), page 74.

31 American-German Review, Vol. VII (1941), No. 5 (June), page 2.

|

22 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY shows two of them below a third (which is a variant of the pure form). As a barn symbol it also occurs in Ohio where it can be seen painted on the barn of Mr. L. J. Neikirk, Route 18, two miles north of Republic, in Seneca County (cf. supra, page 3). |

|

|

|

In Germany it is not at all frequent, except in a clearly de- fined area in Westphalia: the District of Herford; secondarily, it occurs in the flat-lands at the mouth of the Vistula (Weichsel- niederung), near Danzig, a region colonized, centuries ago, by set- tlers from the Old Saxon country, presumably Westphalians from the Herford area. This swastika with curved club-shaped arms is merely a va- |

BARN SYMBOLS 23

riant of the more familiar, angular,

design. As a symbol, most

probably also of the sun, the swastika

presumably originated in

India, in prehistoric Dravidian times.

From there it traveled both

west and east, possibly even, by way of

northeastern Asia, into

the western hemisphere.32 Wherever

it occurs later on, be it the

East or the West, it conveys some

propitious meaning of good

luck, happiness, long life, or magic

protection against evil influ-

ences. In a few cases, it was

secondarily adopted into later re-

ligions and local cults.

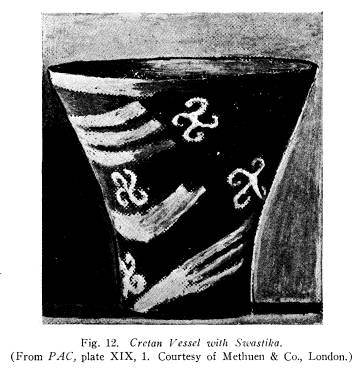

An attempt to trace the swastika, and in

particular its curved

variant, into western Europe again leads

to the Aegean culture of

the Island of Crete. On a clay vessel

(Middle Minoan I, ca. 2100

B. C.) there occurs the curved swastika,

probably an importation

from an earlier, Anatolian, culture

(Fig. 12).

It evidently spread, together with the

other symbols of the

Sun Cult, from the sea inland by way of

the continental trade

routes of the Bronze Age, for it occurs,

for instance, on a modern

wooden stamp, from Brittany (France),

used for the marking of

consecrated bread (Fig. 13). The design,

far from being Chris-

tian, is a swastika-like symbol found,

in basically the same form,

on a Cretan vessel (Middle Minoan II, ca.

1800 B. C.) (Fig. 14).

A striking similarity, that can hardly

be called accidental, pre-

vails between two swastika designs, both

on sword pommels, the

one from Mycenae (Fig. 15a), the other

from a Bronze Age de-

posit in Denmark (Fig. 15b).33

The very same tendency in design appears

in a symbolic rock

sculpture of the British Bronze Age,

near Ilkley, in Yorkshire

(Fig. 16). Its "winding band"

character reveals its connection

with the ornamental style demonstrated

in Figures 15a and 15b.34

There are strong indications that the

people who made this

rock sculpture were Celts of the

Goidelic dialect type. Moreover,

it was in Celtic-speaking Brittany that

the bread stamp with that

32 About the

history of the swastika, see especially WSw, passim.

33 It may prove of some archaeological importance that a design of very

much

the same

character has been found on a piece of Moundbuilder potteryware, at

Glendora Plantation, Louisiana ("Lower Mississippi

Area"); cf. H. C. Shetrone, The

Mound-Builders (New York & London: Appleton, 1941), Fig. 82 (page

142), 145 f.,

371 ff.

34 Cf. ACA, 57 ff.

|

24 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY swastika-like symbol was found which has been discussed above (page 23). Further, the region about Herford, in Westphalia, where the curved club-armed swastika prevails, represents, in its |

|

|

|

peasant houses, a much older, almost purely Celtic, type than those of the surrounding Saxons.35 There is other evidence that this region about Herford is to be regarded as an enclave with a Celtic 35 MSAW, 315 ff. |

26 OHIO ARCHEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

past in the otherwise Saxon area.36

This permits the inference

that the curved club-armed swastika

symbol was especially culti-

vated by Celtic people. Such an

assumption is strengthened by

the fact that Celtic ornamentation, as a

whole, from the late

Bronze Age onward, for centuries favored

the swastika and re-

lated patterns, and, in their

delineation, showed a tendency toward

curved, bulging, designs with

club-shaped terminations (Fig 17).37

The universal occurrence of these

age-old designs as propi-

tious or magic symbols among the

European and, in particular, the

German peasantry naturally makes it

impossible to determine by

which of the various German groups that

constitute the Pennsyl-

vania Dutch any given symbol was

introduced. The very fact that,

even in the German homeland, they all

had been familiar with all

those symbols and their miraculous

powers, renders the whole

question immaterial.

In this connection the writer wishes to

mention Mr. Wey-

gandt's statement that "some of the

shapes of these [barn] sym-

bols undoubtedly have their origin in

Rosicrucian symbols, which

were a matter of moment to several

groups among the German

Pietists, etc., etc."38 It

is unfortunate that Mr. Weygandt is not

more explicit about the symbols he had

in mind, as he wrote these

lines. Among the symbolic signs of the

Rosicrucians, such as pre-

sented by Jennings,39 the

writer has found only three symbols that

are used as Pennsylvania Dutch barn

signs: the familiar penta-

gram

(Trudenfuss);40 a six-pointed star;41 and an eight-pointed

star,42 the two latter,

moreover, expressly and unmistakably desig-

nated as sun symbols. Should Mr.

Weygandt have referred to

these star symbols as being of

Rosicrucian origin, then he would

have to explain how the identical

symbols also occur on Pennsyl-

vania Dutch household articles in

exactly the same application as

on analogous peasant utensils all over

Germany and the rest of

Europe. It is obvious that the

Rosicrucians came by these symbols

36 HDL, 30 ff.

37 Cf. ACA, 150 f., where this

style of design is appropriately termed "flam-

boyant."

38 C. Weygandt, The Red Hills,

. . . (Philadelphia, 1929), 126.

39 H. Jennings, The Rosicrucians, .

. . (London, n. d.), 6th edition.

40 Ibid., 299 (Fig.

235).

41 Ibid., plate I, bottom.

42 Ibid., plate I, top.

|

BARN SYMBOLS 27 |

|

|

|

the same way as did the Pennsylvania Dutch: by way of age-old heritage. In none of the German lands from which the mixed popula- tion of Pennsylvania's barn sign area had recruited itself, does one find such symbols painted on the front of barns as in Berks and the adjacent counties. In fact, with the exception of certain districts in Lower Saxony where they occur on the frames of barn doors,43 one finds them painted on houses only in Switzer- 43 Supra, Fig. 11. |

28

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

land, mainly in the Canton of Bern.

While the contribution of the

North German plains of Lower Saxony to

the population of the

Pennsylvania Dutch country-side is

negligible, Swiss peasants from

the Canton of Bern have not only settled

in great numbers in

Berks County and the neighboring region,

but they have also made

their Alemannian type of barn the

generally accepted form in

these counties and beyond. In their

applying the star symbols to all

kinds of household utensils they do not

differ from the Palatines

and other settlers from Upper Germany

that moved into Penn-

sylvania. But they do differ in

their tendency of applying stars and

related ornamented disk patterns to

human habitations, frontally

and otherwise, although not to barns.44

The fact that the homes in the New

Country were not built

of wood, as they had been in the Swiss

homeland, while the barns

continued to be wooden structures, may

have been the reason why

the symbols were applied, not to the

residence with its limited wall

space of stone masonry, but to the front

of the barn, for this pro-

vided the familiar expanse of board wall

for symbolic ornamenta-

tion.

Once the tendency to paint symbols on

the barns had been

introduced by the Swiss, the other

German immigrant groups

readily adopted it as they had similarly

adopted the Swiss type of

barn. The only districts in the

Pennsylvania Dutch area where

barn symbols have never been applied are

the communities of the

Mennonites (in particular, the Amish)

who have always regarded

their use as sinful.

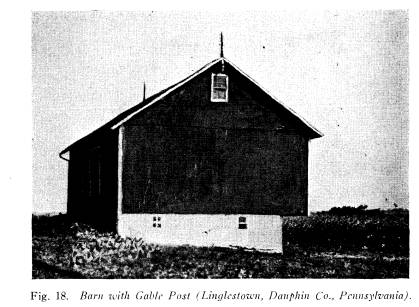

Swiss initiative has left its traces in

still another item of

Pennsylvania Dutch farm architecture: the carved gable posts

found on barns in Dauphin County,

especially near Linglestown

(Fig. 18). In mentioning this, the

writer is not even digressing

since these posts, basically, share with

the barn symbols an ancient

cultic significance and protective magic

function. Their probable

provenience from the worship of Donar

(Thor), the highest god

44 Cf. E. Gladbach, Charakteristische Holzbauten der Schweiz (Berlin

& New York:

Hessling, 1906), plate IX, 3: Door with

Stars; plate XXVI, 1 and 5: Chairs with

Stars; plate XXIX: Ornamented Disks

(1828 A. D.). See also The Brochure Series

of Architectural Illustration (Boston: Bates & Guild), VII (1901), 79:

Six-pointed

Star on eave console of residence, in a

street at Adelboden, Canton of Bern.

|

BARN SYMBOLS 29 |

|

|

|

of the Germans south of the Wodan-worshipping plains region of Old Saxony, makes it appear that their presumable functions were the protection of the barn against lightning, and the securing of fertility for the cattle kept therein. It is certain that they were introduced into Dauphin County from the Alemannian region, the very heart of the ancient Donar Cult, as is evident from the names of early settlers listed in assessment and taxation records of Pax- tang Township, 1777 and 1780. They are almost all German- Swiss.45 The author cannot consider this study in the origin and sig- nificance of the barn symbols completed without also touching upon their subjective significance. In other words, it is not suffi- cient for a comprehensive treatment of this topic to have discussed their objective significance on the basis of historical and archaeo- logical evidence. The much more important side of their signifi- 45 W. E. Egle, History of the Counties of Dauphin and Lebanon, . . . (Philadel- phia, 1883), 101 and 289. |

30

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

cance is covered by the question: what

do they mean to the people

who apply them even today in the

Pennsylvania Dutch country?

The unquestionable credence these magic

symbols have been

receiving, both in Europe and

Pennsylvania,46 can only be ex-

plained on the basis of peasant

psychology, which is group psychol-

ogy. The individual peasant may

be entirely honest in telling the

stranger that he does not believe in

"such things." Just the same,

as a member of his peasant community he

cannot extricate himself

from the group belief which is

super-individual. He applies sym-

bols to his barn or household utensils,

not because he, as a person,

feels that he must have them, but

because "one has to have them."

The group spirit commands it so.

With outsiders he does not even touch

upon such matters; it

is taboo. A feeling akin to chastity

keeps his lips sealed in the

presence of the "gentile" from

"abroad," who "does not speak his

language." This is not merely a

figure of speech but is to be taken

literally. That was brought home to the

writer by an unforgettable

experience:

A few years ago, I spent a few days in

Berks County as a guest in

the home of an old lady, now dead. She

was of old Pennsylvania Dutch

stock and loved to tell stories about

the days of the past and about the

people she had known. I would not tire

listening to her, nor would she,

answering my questions.

In the beginning of my stay, she spoke

to me in English, as she would

to all visitors not of the native kin.

Some fine day, however, she discovered

that I did not only understand her

Pennsylvania Dutch, but that I even

could talk "her own language."

This I accomplished by simply speaking

my Rhine-Hessian home dialect with a few

concessions to Berks County

vocabulary and phonology. No matter how

well or how badly I did it, I

distinctly felt that I now was

"accepted": I spoke her language, I was no

longer an "outsider." Every

word, every gesture from her intimated that

she trusted me with

"understanding."

A day or two later, as usual, I was

helping her in the kitchen with

the washing of the breakfast dishes.

Although she appreciated the little

service, it always embarrassed her a bit

that a man, moreover a guest,

should be doing house-work as long as

she, a woman, was around to do it.

The point was that her "group"

does not approve of men doing kitchen

chores. This embarrassment always drove

her into her shell, as it were,

and made her speak English.

46 For literary evidence, cf. Mr.

Weygandt's statements, supra, page 5.

BARN SYMBOLS 31

That particular morning, our talk

somehow drifted toward the deli-

cate topic of Hexerei (witchcraft)

and protection against it by means of

barn symbols and other magic. Quite

casually, I asked her whether the

people in the neighborhood really

believed in it. She said that she did not

think so although she was not quite

sure. Maybe, there were still a few

that did. Never was I to think that she

and her family had ever believed

in things of that sort.

All this had been said in English, mind

you. It was obvious that she

had conveyed to me what the

"group" expected her to answer the "outsider"

who asked such questions. Thereafter,

she was silent, so pointedly silent

that no request to drop the subject

could have been more eloquent.

Then came the psychological climax.

After a pensive pause, her face

quite unexpectedly brightened, and she

broke into story-telling. This time

in Pennsylvania Dutch. She told me stories about her father, her mother,

her sisters, and other members of her Freundschaft

(kith and kin): what

each of them had done, on this and that

occasion, to ward off evil influences

that threatened them from certain people

reputed to practice witchcraft.

Some such person had come to the house,

under a flimsy pretext, or had

been observed loitering near the

cattle-barn. Then, of course, the preventive

measures had to be taken which

"everybody" takes in such a case. Although

there were Hex Signs on the barn,

certain objects were shoved under the

door-sill of the cow-stable; certain

chalk-marks were written on door posts;

certain herbs were hung near the

cattle-stands. Otherwise the cows might

have dried up, or given bloody milk.

All this and more she told me, revelling

in memories. How was that

to be explained? Was she aware of

contradicting herself? No, she was not.

What had happened, was this: All the

time that we had been speaking

English, under the cloud of her

embarrassment, I had been to her the

"outsider" who "did not

speak her language," that is, the language of the

"group." Furthermore, in conformity with her

"group" ethics, she had

told the "outsider" what,

under the circumstances, "one says" to the "out-

sider" in the outsider's language.

He need not, in fact he must not, know

what the "group" knows and

believes.

Of a sudden, however, it must have

occurred to her that, after all, I

did "speak her language" and, therefore, really

was an "insider." So she

dropped into Pennsylvania Dutch, and as

she was "speaking her language,"

she was speaking "within the

group," where alone it is spoken and under-

stood, and where secretiveness is not in

order. She felt that there was no

harm done by my being "in the

know," and so she told me all she

remembered.

Time will show how long the Pennsylania

Dutch will be able

to maintain themselves as a group.

Advancing radially from

the big cities, the standardizing and

mechanizing forces of today's

32 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL

QUARTERLY

steel-and-concrete

civilization are steam-rolling over the peasant

minority of the country-side. At the rate of this deadly on-

slaught,

group-consciousness is being wiped out and, along with

it, the barn symbols,

the beliefs for which they stand, and all

other values of this

old peasant culture.

BIBLIOGRAPHY AND

ABBREVIATIONS

Bock titles cited in

the foot-notes are here not repeated.

ACA Allen, J.R., Celtic Art

in Pagan and Christian Times

(Philadelphia:

Jacobs, n.d.).

BAAC Bossert,

H.Th., The Art of Ancient Crete (London:

Zwemmer, 1937).

BPAEu ................, Peasant Art in Europe (Berlin: Wasmuth,

1926).

CDoEC Childe,

V.G., The Dawn of European

Civilization

(London [New York],

1927).

COPA Cleland,

H.F., Our Prehistoric Ancestors (New

York:

Coward-McCann, Inc.,

1928).

HDL Hofmann, A. v., Das deutsche

Land und die deutsche

Geschichte (Berlin & Leipzig: Deutsche

Verlagsanstalt,

1923).

HPAAu Holme,

Chas., Peasant Art of Austria and

Hungary

(London: The Studio,

1911).

HPAIt ................, Peasant Art of Italy (London: The Studio,

1913).

HPARus ..............., Peasant Art of Russia (London: The Studio,

1912).

HPASw ............., Peasant Art of Sweden, Lapland and Iceland

(London: The Studio,

1910).

MSAW Meitzen,

A., Siedlung and Agrarwesen der

Westgermanen,

... (Berlin: Hertz,

1895).

PAC Pendlebury, J.D., The

Archaeology of Crete (London:

Methuen, 1939).

SchEx Schuchhardt,

C., Schliemann's Excavations (London:

Macmillan, 1891).

TDO Trepte,

H., Deutschtum in Ohio (Doctoral

Dissertation,

Leipzig, 1931) [in Deutsch-Amerikanische

Geschichtsblatter

(German-American Re-

view), (Chicago), XXXII (1932), 155-409).

WSw Wilson,

Thos., "The Swastika, ..

." [in Reports, Smith-

sonian

Institution; U. S. National Museum,

1893-1894 (Washington, 1896), pp. 757-

1011].

ZWDV Zaborsky- Urvatererbe

in deutscher Volkskunst (Leip-

Wahlstatten, O.v., zig: Koehler & Amelang,

1936).

ORIGIN AND SIGNIFICANCE OF PENNSYLVANIA

DUTCH BARN SYMBOLS *

By AUGUST C. MAHR

On a great number of Pennsylvania Dutch

barns, there are

geometrical ornaments painted on the

outside walls; ornaments

which, as a rule, show some sort of star within a circular disk

(Figs. 1, 2, 8, 10b). They occur most

frequently in Berks and

the neighboring counties; less

frequently, in other parts of Penn-

sylvania; and, locally, even in Ohio and

other states of the Union

where Pennsylvania Dutch farmers have

settled.

Due to Ohio's close proximity to

Pennsylvania, as well as to

its importance, in early frontier days,

as both a temporary and

permanent place of settlement for

eastern farmers venturing west-

ward, it is in Ohio that not only barns

of Pennsylvania Dutch

structure are more frequently found than

anywhere else outside

of Pennsylvania, but here one may also

see the barn symbols that

are so striking a characteristic of the

Pennsylvania Dutch counties

mentioned above.

The Pennsylvania Dutch barn in question

is of the so-called

Swiss bank-barn type. It means that it

is erected along an em-

bankment in such a way that its main

entrance door leads to the

heavily planked floor of its wooden

upper story. This floor is at

the same time the ceiling of the lower

story formed by the stone

base structure which contains the

stables for the livestock and is

* This study grew out of a paper read

before the Anthropology Section of the

Ohio Academy of Science, at its annual

meeting, in May, 1943, at Columbus, Ohio.

The writer is glad to express his

gratitude to Professor Edgar N. Transeau of Ohio

State University for the photographs taken in

Pennsylvania, of barns shown in

these pages; to Dean Carl F. Wittke, and Professor Clarence Ward, both of Oberlin

College, for photographs and scholarly

aid; to Professors John W. Price, and Wilmer

G. Stover, both of Ohio State

University, and to Dr. James H. Rodabaugh and Mrs.

Margaret Stutsman, of the Ohio State

Archaeological and Historical Society, and Mrs.

Mary Jane Meyer, of the Ohio War History

Commission, for helpful field-work; to Dr.

Jean Weltfish, of Columbia University,

for valuable bibliographical advice; to the Grad-

uate School of Ohio State University for

generous help in securing the illustrative ma-

terial; and, last but not least, to the

publishing houses, in London, of A. Zwemmer,

Macmillan. & Co., and Methuen &

Co., Ltd., for their permission to reproduce pictures,

from works published under their

imprint, as illustrations of this article.

(I)

(614) 297-2300