Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 30

- 31

- 32

- 33

- 34

- 35

- 36

- 37

- 38

- 39

- 40

- 41

- 42

- 43

- 44

- 45

- 46

- 47

- 48

- 49

- 50

- 51

- 52

- 53

- 54

- 55

- 56

- 57

- 58

- 59

- 60

- 61

- 62

- 63

- 64

NOTES

Contributors to This Issue.

Roy F. Nichols is Professor of History

in the University of

Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Raymond F. Fletcher is Business Manager

of the Portsmouth

(Ohio) Times.

Howard H. Peckham is Director of the

Indiana Historical

Bureau and Secretary of the Indiana

Historical Society, Indian-

apolis.

William Alexander Mabry is Professor of

History in Mount

Union College, Alliance, Ohio.

Cathaline Alford Archer (Mrs. John Clark

Archer) of Ham-

den, Conn., interests herself in local and

family history of the

Western Reserve of which she is a

native.

Frederick C. Waite, Professor Emeritus,

Western Reserve

University, now located in Dover, N. H.,

is the author of two

volumes of Western Reserve University

history. (See reviews

in this issue.)

John William Scholl is Professor

Emeritus, University of

Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Curtis W. Garrison is Director of

Research, Hayes Memorial

Library, Fremont, Ohio.

Book reviewers, represented by initials,

are Robert C.

Wheeler, James H. Rodabaugh, John O.

Marsh, Bertha E.

Josephson, and Harlow Lindley of the

Society's staff, and Mary

Jane Meyer of the Ohio War History

Commission.

310

THE DECLINE OF EPIDEMIAICS IN OHIO

by ROBERT G. PATERSON

Executive Secretary, Ohio Public Health Association

Secretary, Ohio Committee on Medical History and Archives

Introduction

When one considers the intimate relationship between disease.

particularly epidemic disease, and the individual it is a source of

wonder as to the almost complete absence of reference to this

phase of daily life in the standard histories of Ohio. From

Salmon P. Chase's A Preliminary Sketch of the History of Ohio

published in 1833 and Caleb Atwater's History of the State of

Ohio, Natural and Civil, issued in 1838 down to our own time,

the impact of medicine and disease upon the people of the State

has been all but ignored.

Change in Historical Perspective

A careful examination of the latest and most complete history

of the State of Ohio published in 1941-44 by the Ohio State

Archaeological and Historical Society reveals an awareness of the

social and scientific aspects of medicine never equalled in any of

the previous histories of the State. The nearest approach to this

latest history was the six-volume history of Ohio by Emilius O.

Randall and Daniel J. Ryan published in 1912. They secured

the collaboration of Dr. D. Tod Gilliam of Columbus, Ohio, to

contribute a chapter on "Medical Ohio." His discussion was

devoted largely to the institutional aspects of medicine.

"Historian's Note-Book"

The reason for the increased emphasis upon disease and

medicine in this latest history is, in my opinion, due to the per-

sistent effort exerted by Dr. Jonathan Forman. In 1936, he

began the conduct of "The Historian's Note-Book" in the Ohio

State Medical Journal. Late in 1936, Dr. Forman became the

editor of the Journal and in 1937, he turned the "Note-Book"

311

312 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND

HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

over to Dr. David A. Tucker, Jr., of

Cincinnati. Practically no

issue of the Journal has been

published since then without a con-

tribution to the "Note-Book."

This publishing outlet has been

the means by which a score or more

historical medical writers

have been stimulated to explore the

medical history of Ohio.

Ohio Committee on Medical History and

Archives

But perhaps more influential than the

"Note-Book" have

been the contributions of the Ohio

Committee on Medical His-

tory and Archives of the Ohio State

Archaeological and Histori-

cal Society. This committee was

organized in 1939 with Dr.

Forman as chairman and with the

whole-hearted support of Dr.

Harlow Lindley, Secretary of the

Society. Since 1939 the Octo-

ber-December issues of the Society's

quarterly journal have con-

tained papers dealing with various

phases of medicine and the

allied professions in Ohio.1

These papers were drawn upon

substantially in the writing

of the latest history of Ohio. While

much of the same informa-

tion had been available for many years,

it was hidden in the

primary sources exclusively medical in

character. These sources

were the medical journals, proceedings,

and transactions of medi-

cal societies which did not enjoy much,

if any, circulation among

the professional historians. But with

the advent of this material

in the Ohio State Archaeological and

Historical Quarterly the

attention of the Ohio historians to this

hitherto overlooked

material was caught and held. For

example: Professor William

T. Utter in Volume II of the recent History

of the State of Ohio

covering "The Frontier State--1803-1825"

devotes an entire

chapter of twenty-three pages to the

discussion of "Sickness and

Doctors." The other volumes of the

series contain repeated ref-

erences to specific diseases and medical

institutions together with

their social impact as they occurred

throughout the State.

Modern Discussion Lacking

The validity of these remarks is born out

by an examination

of Volume VI, a compilation of seventeen

monographs dealing

1 Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Quarterly,

XLVIII-LIV.

EPIDEMICS IN OHIO 313

with various phases of life in Ohio in

the twentieth century, 1900

1938.

The raw materials for dealing

with the diseases and

health of the people of Ohio are

available in the annual reports

and bulletins of the Ohio Department of

Health, in the Ohio

State Medical Journal, and in other kindred professional sources.

No one, as yet, has taken the time to

collate this material into a

monograph. There is no subject of

greater social significance

or more dramatic value in the history of

Ohio than the growth of

medicine and public health service

since 1900. The immense

increase in scientific knowledge of

medicine and the successful

social application of that knowledge in

the control of disease.

particularly epidemic disease, has

almost been taken for granted

by our people.

Title of Discussion

The title of this discussion, "The

Decline of Epidemics in

Ohio," is perforce a

"tongue-in-cheek" one. In the present state

of our knowledge an epidemic of a

communicable disease may

break out in any part of the state at

any time. However, the

fact remains that we have not had a

major state-wide epidemic

of any disease since the pandemic of

influenza in 1918-19. This

is the longest epidemic-free period in

the history of Ohio.

It seems worth while to examine the

causes for this freedom

which society has enjoyed for so long a

period of time, and to

consider such questions as: What has

been the past history of

epidemics in Ohio? How can we account

for the decline of epi-

demics? What are the factors which seem

to be our safeguards

against devastating epidemics?

Division of Discussion

There are three broad and arbitrary

periods of time since

the first settlement of the state in

1788 which appear as marking

the advance society has made in this

field of social well-being.

The first period embraces the years 1788

to 1873 or 85 years; the

second period covers the years 1873 to 9000 or 27 years;

and

the third period spans the years from 1900 to 1945. These

broad

time periods follow those adopted in

the.latest history of Ohio.

314

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

An over-all examination of the evidence

will warrant the

conclusion that more effective advance

in the control of epidemics

in Ohio has been made within the past

forty-five years than was

made in the entire one hundred and

twelve years prior to the

beginning of this century. There are many and complicated

reasons why this is so. It is hoped that

a brief review of these

three periods will throw some light upon

the developments in

epidemic control that have occurred

during the past one hundred

and fifty-seven years.

In order to keep this discussion within

reasonable limits it

will be confined to a few selected

epidemic diseases and a few

chosen episodes to point their

destructive effects. These epidemic

diseases are influenza, yellow fever,

cholera, small-pox, typhoid

fever, diphtheria, and two endemic

diseases--malaria and tuber-

culosis. These have been the

fear-provoking diseases among our

people. They are the diseases which have

caused the greatest

mortality at varying periods of time.

They are the ones which

have caused the greatest social

disorganization. Finally, they

are the ones which have challenged

"the spirit of adventure" of

the human mind to unravel their

mysteries.

Today, as we examine this list of

diseases, we find yellow

fever and cholera completely gone as

causes of either morbidity

or mortality in Ohio; malaria, typhoid

fever, diphtheria, and

small-pox almost at the vanishing point;

while tuberculosis is

being reduced rapidly in its relative

destruction of life and health.

Influenza, alone, stands as an

uncontrolled threat in the epidemic

field.

In the following Table I it will be

noted that the Ohio figures

begin with 1910. Ohio did not pass a

comprehensive vital sta-

tistics law until 1908. The figures for the first full year of

collection cover the year 1909. While

these figures were a vast

improvement on any previously reported

the 1910 figures come

more nearly reflecting the true

mortality situation than those of

1909. It will be seen that Tuberculosis

and Infant Mortality are

the two disease situations confronting

Ohio.

EPIDEMICS IN OHIO 315

Table 1

SPECIFIC DEATH RATES FOR SELECTED CAUSES

1910 - 1941

1. TUBERCULOSIS 4. DIPHTHERIA

Year Deaths Rates Year Deaths Rates

1910 7,179 150.6 1910 474 122

1915 6,668 126.5 1915 673 12.8

1920 5,932 103.0 1920 6:39 11.2

1925 4,816 74.9 1925 389 6.1

1930 4,233 64.1 1930 160 2.5

1935 3,602 52.8 1935 178 3.6

1940 2,785 40.8 1940 29 0.4

1944 2,754 39.2 1944 32 0.4

2. INFANT MORTALITY 5.

SMALL POX (U.S. RATES)

Year Deaths Rates Year Deaths Rates

1915 11,463 91.0 1910 0.4

1920 10,160 82.9 1915 0.1

1925 8,841 69.6 1920 0.6

1930 7,209 60.7 192 0.1

1935 5,080 50.4 1935 0.0

1940 4,739 41.4 190 0.0

1944 5,136 39.0 19 0.1

1944 0.1

3. TYPHOID

FEVER 6.

MALARIA

Year Deaths Rates Year Deaths Rates

1910 1,327 27.5 1910 0.8

1915 718 13.7 1915 0.5

1920 436 7.5 1920 0.2

1925 325 5.2 1925 0.2

1930 236 3.4 1930 0.1

1935 97 1.4 1935 0.1

1940 47 0.7 1940 0.0

1944 10 0.2 1944 0.7

I. The

Period from 1788 to 1783--Confused

Speculation

The general characterization of this period may be said

to be

"confused speculation." A brief review of the available primary

sources of information about epidemic diseases in Ohio

during

this period will convince any investigator of the

aptness of this

phrase. The

entire period is full of prolonged and oft-times

heated discussions in the realms of causation,

diagnosis, treat-

ment, and prognosis.

As in so many other areas of medical history, we

perforce

begin with Dr. Daniel Drake of Cincinnati. His mind. spirit,

310

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

and indefatigable zeal led him to

publish in 1810 a booklet setting

forth the results of his observations of

life in Cincinnati under

the title of Notices of Cincinnati,

Its Topography, Climate and

Diseases. Five years later he

published that remarkable book

about Cincinnati which established him

as the foremost author

of the Ohio country. It was entitled Natural

and Statistical View

or Picture of Cincinnati and the

Miami Country. Drake's Pic-

ture of Cincinnati, as it is called, contains seven chapters and an

appendix covering in all 250 pages. In

chapter five he devotes

his attention to the consideration of

medical questions, the pre-

vailing diseases and their courses, in

the region around Cincinnati.

So far as can be ascertained, the best

single source of in-

formation available on the incidence of

early epidemic diseases

in Ohio is contained in the presidential

address of Dr. Samuel

Prescott Hildreth of Marietta. This

address was delivered be-

fore the third session of the Medical

Convention of Ohio held in

Cleveland on May 14, 1839. In his

discussion of "Diseases of

the Early Settlers of Ohio" he says

in part:

They sometimes were attacked with

malignant remittants in the

summer, and pneumonias and pleurisys in

the winter, but no serious epi-

demics appeared until partial openings

had been made in the primeval

forests, and the wet low grounds exposed

to the action of a summer sun . .

From the year 1788, the period of the

first improvements in Ohio, to the

year 1807, the date of the first great

epidemic, a large proportion of the

diseases originated in exposures to wet,

cold, hunger, and fatigue, and

were generally of an inflammatory type,

such as Rheumatisms, Pleurisys,

Pneumonias, Scarlatina and Small-pox.2

The great epidemic of 1807 was

influenza. Dr. Hildreth

continues:

The winter following the epidemic of

1807, was mild, and the summer

months were marked with no prevailing

diseases. From the years 1807 to

1813, the country was very healthy. The

few fevers which did appear were

generally typhoid, or synochal. Bilious

cholics for several years after the

epidemic, was a very common disorder.

Phthisis pulmonalis, also became rather

more frequent after the In-

fluenza, but was still a rare

occurrence. During the heats of summer

2 Samuel Prescott Hildreth,

"Address of the President," in Journal of the Pro-

ceedings of the Medical Convention of

Ohio, May 14-15, 1839, 16-7.

EPIDEMICS IN OHIO 317

cholera infantum was greatly more

frequent than it is at present, and often

proved fatal. It probably arose from the

same malarious state of the

atmosphere which produces intermitting

fevers, as we find it most prev-

alent in regions favorable to the latter

disease ....

By the first of August [1822] the

epidemic [yellow fever] was general

in this portion of the valley, and

especially in Marietta. The largest number

of attacks was in September, and at one

time there was not less than four

hundred cases within the area of one

square mile. They were composed

of all, from the mild intermittent to

the most malignant remittant, with the

usual symptoms which attend the yellow

fever. During the season I had

about six hundred patients under my

care. For four months in succession,

I ate but two meals a day, and spent

from sixteen to eighteen hours out

of every twenty-four in attending the

sick. Through a merciful Providence

my own health was good, and the only

suffering was from exhaustion and

fatigue through the whole of this

disastrous season. The proportion of

deaths was about six in every hundred cases,

where proper medical atten-

tion was given the sick; but so general

was the disease that many lives

were lost from a lack of nurses. All

other disorders were swallowed up

by this.3

We come now to the epidemic of Asiatic

cholera of 1832-34.

This epidemic was so devastating and

created so much fear,

that with each recurring epidemic of the

disease until the end of

the third quarter of the century this

fear was the motivating force

which led to an anxious desire to do

anything that promised relief

from its effects. Here again we quote

from Hildreth:

Early in that year [1832] the people

began to be alarmed with the

accounts from Europe of the ravages of

Asiatic Cholera, . . . and it made

its appearance on the N. E. coast of

America about the last of May, and

spread with fatal rapidity along the

great water courses which border the

northern side of the United States. . .

. With us no cases occurred this

year, but a few appeared late in the

season at Cincinnati. . . . Either

from a nervous dread of the disease, or

some morbific constitution of the

atmosphere, a large majority of the inhabitants this summer were

troubled with bowel complaints,

generally a moderate diarrhea. . . . No

disease which ever visited the civilized

world held such control over the

nervous system and moral faculties of

man; and during the period when the

great mass of our citizens believed it

to be contagious, I have no doubt that

one-half of its victims took the

disease, and actually died from the de-

pressing effects of dispair and fear. .

. . In 1833 and 1834 this epidemic

scourge still continued to visit our

most populous towns and cities in the

3 Ibid., 23-6.

318

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

west, while the sparse and thinly

settled portions of the country scarcely

felt its effects; . . . I think it was

found that the cleanly and well venti-

lated portions of our cities suffered

the least, and the filthy and ill-aired

the most.4

We can recognize today, from this

account, how keen were the

observations of the leading medical men

of that era.

In March 1933, Dr. Jonathan Forman

prepared a paper on

"The First Cholera Epidemic in

Columbus, Ohio (1833)." It was

later published in the Annals of

Medical History in 1934. His

description of the disease is of such a

vivid character that the

deep-seated fear created by an attack of

cholera is readily under-

standable. He says:

The epidemic of Asiatic cholera which

swept over our City one

hundred years ago this summer, for its

mortality and terror, surpassed any

pestilence that ever afflicted Columbus

before or since.

Cholera, because of its sudden

appearance, its high mortality, and

the frightful appearance of its dead,

has always been a dramatic character

in the history of the human race. Those

who die of this disease are a

gruesome sight. It attacks the bowels

and causes a stupendous loss of body

fluids in the typical "rice-water

stools." The whole body becomes covered

and dank moisture. Cheeks become hollow,

nose ipnched, eyes sunken,

voice husky. Death's rigor sets in

quickly. Muscles literally become as

hard as a board. Sometimes a stiffening

corpse jerks about; it may kick

out a foot, wave an arm, flap its jaws

or roll its eyes. Of such things is

the natural terror of man for this

loathsome disease.5

With such a graphic picture of the

disease, and it was en-

countered daily by the physicians in the

epidemic of 1832-34,

we meet Dr. Daniel Drake again. He

persuaded the city council

of Cincinnati not to attempt to shut out

the disease by erecting

barriers against it. Then he set to work

to devise a substitute

plan of defense. The first step in this

plan was public education.

He proceeded to write a book of 180

pages entitled A Practical

Treatise on the History, Prevention,

and Treatment of Epidemic

Cholera, addressed both to the profession and to the people of

the Mississippi Valley in which he

presented the existing know-

4 Ibid., 30-1.

5 Jonathan Forman. "The First

Cholera Epidemic in Columbus, Ohio (1833),"

in Annals of Medical History, n.

s. VI (1934), 410-26.

320 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL

QUARTERLY

ledge and theories pertaining to

cholera.6 It is in this book that

Drake cane very close to anticipating

the later discoveries as to

the origin of infectious diseases. He

did not accept the popular

miasmatic theory or its modifications,

the malarial theory, as the

cause of the disease. He believed the

animalcular theory the most

rational of all and by citations and his

own experience established

the existence of animalculae everywhere,

but especially in de-

caying organic matter.

Not content with his efforts in this

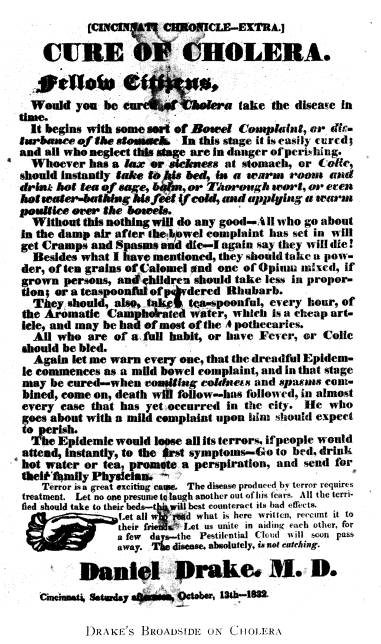

direction, Drake wrote

a broadside of one page which was issued

as an extra insert to

the Cincinnati Chronicle. It was issued Saturday afternoon,

October 13, 1832. This broadside was

probably the first such

attempt at popular health education in

Ohio. The contents of

this broadside are typical of the period

we have chosen to call

"confused speculation."

Drake later estimated that four per cent

of the population

of Cincinnati was destroyed in three

years, 1832-34. This meant

a total of 831 deaths.

In the second cholera epidemic in Ohio

which struck between

1848 and 1850, there were two events

that made a deep im-

pression upon the minds of the people

throughout the State.

The State Board of Agriculture created

by the General Assembly

in February 1846, planned a large state

fair to be held in Cin-

cinnati in 1849. The outbreak of cholera

caused its postpone-

ment until 1850 when the first Ohio

State Fair was held in Cin-

cinnati.7 But in July 1850,

another outbreak of cholera (result-

ing in the death of one of the Executive

Committee of the State

Board) led to the holding of the second

state fair at Franklinton

(Columbus) in September 1851.

The other event was curiously a reversal

of the course fol-

lowed in the transfer of the State Fair

from Cincinnati to Colum-

bus. The Ohio Constitutional Convention

met in the State House

in Columbus, May 6, 1850, to draft a new

state constitution for

6 Daniel Drake, A Practical Treatise on the History,

Prevention, and Treatment

of Epidemic Cholera . . . (Cincinnati, 1832).

7 Francis P. Weisenburger, The

Passing of the Frontier, 1825-1850, Carl Wittke,

ed., The History of the State of Ohio

(Columbus, 1941-44), III (1941), 71-3.

EPIDEMICS IN OHIO 321

Ohio. On July 9, 1850, the convention

adjourned because of the

cholera epidemic in the city. It reassembled in Cincinnati,

December 2, where it finished its work on

March 10, 1851.8

Both of these episodes had a tremendous

effect upon the

people throughout the State. Dr. Edwin

W. Mitchell in his dis-

cussion of cholera in Cincinnati9 estimated

that between May 1,

and August 30, 1850, there were 4,114 deaths from cholera out

of a total of 6,459 deaths from all

causes for the same period. The

population of the city at this time was

estimated at 100,000.

By 1850, many observers drew attention

to water as a means

of conveying the disease. By 1873, the

year of the last visita-

tion of cholera, contamination of the

water supplies was generally

recognized as a source of infection and

the belief in its bacterial

origin common among the advanced

thinkers of the day.

These few selections of the periodic

recurrent epidemics, it

is hoped, may convey an idea of the

constant fear, nay even

terror, which possessed the people of

Ohio from 1788 to 1873.

This fear was not allayed by the

confused explanations as to cause

offered by the medical profession. But it is clear now that the

leaders of the profession were not idle

in their constant search for

a better understanding of these

scourges. In addition to rugged

battles among themselves and fighting

against quacks and charla-

tans, they were busy establishing

medical journals, conventions,

colleges, and hospitals and constantly

striving to raise the educa-

tional standards of the profession.

Their etiological explanations

were those that were current

elsewhere--that the diseases arose

from miasms in the atmosphere. Their

therapeutic ideas were

heroic. When Prime Minister Churchill

coined his striking

phrase, "Blood, Sweat and

Tears," one who knew the history

of medicine in this period must have

gained the impression that

the Prime Minister was familiar with the

therapeutic practice of

that day--which was "bleed; purge;

puke; and sweat."

Throughout this period the dependence of

society in com-

8 Ibid., 207,

479; Eugene H. Ruseboom, The Civil War Era, 1850-1873, Carl

Wittke, ed., The History of the State

of Ohio (Columbus, 1941-44), IV (1944), 130.

9 Edwin W. Mitchell,

"Cholera in Cincinnati,"

in Ohio State Medical Journal,

XXXIII (1937),

69-70.

322 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

batting epidemics was upon isolation of the patient, quarantine

of

contacts, and the abatement of nuisances. The main idea was

to

clean up the environment to reduce to a minimum the poisoning

of

the air by miasms. Boards of

health were more or less

ephemeral

bodies hastily organized during a threat of an epidemic

and

as hastily disbanded when the epidemic had passed on. There

was

also discernable a gradual shift in emphasis from systems of

medicine

to schools of therapeutics. The rise and struggle for

supremacy

between the so-called allopathic (regular), homeo-

pathic,

and eclectic schools of treatment had a retarding effect

upon

medical development in Ohio.

Finally, during the latter

part

of this period, there was a continual controversy between

those

who believed in contagion as an explanation as to the cause

of

the epidemic diseases and those who denied any such idea.

Table

II

EPIDEMICS

IN OHIO, 1788-1873

Year Population Disease Period

1810 230,760 Influenza 1807

1820 581,295 Yellow

Fever 1821-23

1830 937,903 Influenza 1826

Cholera 1832-34

184 1,519,467 Typhoid 1840-42

1850 1,980,329 Cholera 1849

Cholera 1854

1860 2,339,511 Diphtheria 1856-59

1870 2,665,260 Cholera 1865-66

Small

Pox 1868

Cholera 1871-73

II.

Period from 1873 to 1900 -- Scientific Demonstration

The

establishment of the germ theory as an explanation of

the

causation of a large number of epidemic diseases brought to

a

close the long conflict between contagionists and anticontagion-

ists.

It made possible what we have chosen to call the period of

"scientific

demonstration." Improvements in

the microscope

made

it possible for the French chemist, Louis Pasteur, the

German

country physician, Dr. Robert Koch, and the English

surgeon, Dr. Joseph

Lister, to lay the foundations for attacks

EPIDEMICS IN

OHIO 323

upon communicable diseases and advances

in surgery, which have

gone on from 1865 to the present day.

But the birth of new ideas and the death

of old established

and cherished beliefs are ever fraught

with painful struggles.

Ohio's physicians as well as the people

at large were slow to

accept the new ideas. Throughout this

entire period the annals

of medical thought in Ohio are replete

with the continual con-

tention between acceptance or rejection

of the idea that pathogenic

microorganisms were the explanation of

many of the diseases

which afflicted the people.

Medicine moved away from being solely an

art into the realm

of science. The rise of bacteriology

created the laboratory where

scientific procedures could be

established for the detection of the

organisms in specific diseases. There

ensued a veritable furore of

investigations which discovered a long

list of causative organisms

and gradually established the various

avenues of infection--

personal contact, food and drink, and

biting insects. The science

of immunology sprang up as a collateral

branch of bacteriology.

The interval from 1873 to 1892 was the

most fruitful in the gross

benefits of medical science to mankind

of any like interval in

history.

While there was no cholera epidemic in

Ohio recorded dur-

ing this period, yet it was cholera

which led to a new approach

in control. Koch discovered the

comma-bacillus in 1884 as the

causal organism in cholera. From 1884 to 1892

cholera was

prevalent throughout Europe. The

epidemic culminated in the

great

Hamburg outbreak of 1892 with 17,000

cases and a half

as many deaths. New York was threatened

in 1892 and as a re-

sult a city laboratory was established

by Drs. Biggs and Prudden

in the Health Department. The laboratory

dictated the policies

of quarantine and sanitary matters; it

was arbiter on questions

of diagnosis.

That the new science was effective is

evident; eight badly in-

fected ships, which had lost 76

passengers came to the New York

quarantine and discharged their

passengers both sick and well; yet

with proper care only forty-four deaths

occurred at quarantine

324

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL

AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

and from the ten cases that were found

in the city not a single

instance of secondary infection was

discovered.

In the meantime (in April 1886) the Ohio

General Assembly

had passed a bill to create a State

Board of Health.10 Efforts to

achieve this objective had been exerted

vainly at spasmodic in-

tervals for the preceding ten years. The

obstacles were the dif-

ferences between the allopathic and

homeopathic schools of medi-

cine, each fearful of losing supremacy,

as well as the state of

public opinion as reflected by the

legislators over the question

whether diseases were or were not caused

by the "so-called

germs." This act placed Ohio

thirty-second in the list of states

to establish a state board of health;

Massachusetts had been the

first state to set up such an authority

in 1869. The total appro-

priation for the new state activity in

Ohio was the huge sum of

$5,000!

Dr. Charles O. Probst became the first

real secretary of this

State Board of Health. He was its

guiding mentor for twenty-

five years. To read the annual reports

of the work of the State

Board of Health from 1886 to 1911 is to

read the record of hope

deferred, unflagging courage,

intelligent maneuvering, and a

splendid spirit of adventure. To the

present generation of Ohio-

ans skimming blithely over the highways

of the State and streets

of our cities there is no realization of

the vast debt they owe to

this pioneer public health administrator

of Ohio.

Let him tell us in his own words about

the threat of the

1892 cholera situation:

From an epidemic of cholera in Hamburg

and Altoona [Germany],

originated the legislation which has

pushed Ohio to the front in the pro-

tection of her streams, lakes and public

water supplies. It came about in

this way . . . a codification of the

health laws was made which was em-

bodied in a Bill that was introduced in

the House of Representatives. It

contained many new provisions, and made

a document of fifty or more

pages. Cholera from Hamburg appeared at

New York about this time,

and the whole country was alarmed. A

patrol guard was organized on all

railway lines going west through Ohio,

with inspection of all passengers,

night or day, with camp equipment for

the care of cases that might be

10 Ohio Laws,

LXXXII, 77.

EPIDEMICS IN OHIO 325

found. . . . Ohio was naturally greatly

concerned. Our Health Bill

was before the House. It was so long I

didn't believe any one would

read it, so, with the consent of the

member who introduced it, the fol-

lowing addition was made . . . "and

no city, village, corporation or

person shall introduce a public water

supply or system of sewerage or

change or extend any public water supply

or outlet of any system of sew-

erage now in use, unless the proposed

source of such water supply or out-

let for such sewerage system shall have

been submitted to and received

the approval of the state board of

health." The Bill, with this

amend-

ment, was passed March 14, 1893.11

This act gave to the State Board of

Health sufficient author-

ity to ensure that when an order was

issued to a local sub-division

for such change or improvement of a

water supply the tax limit

could be increased, within limitations,

without a vote of the people

to carry out the Board's order. Thus was

brought about the

effective control of cholera and typhoid

fever in Ohio.

Typhoid fever epidemics were usually of

a local character

and were constantly present in this

period. Cincinnati and Co-

lumbus appear to have had the sternest

battles with the disease.

Dr. Probst has left us a clear picture

of the forces at work in

Columbus for and against the necessary

steps to control typhoid.

He says:

Columbus had for years taken its water

supply from the Olentangy

river a little above the city, and for

years had had, at intervals, outbreaks

of typhoid fever. When Mr. Jacobs was

Director of Public Works, he

conceived the idea of getting a ground

water supply, already purified, he

used to say, by intercepting the ground

water by laying a system of large

iron perforated pipes along the river

shores. He installed very consider-

able lengths of this. As this was an

"additional supply," under the Bense

act, it had to be approved by the State

Board of Health. An unprecedented

epidemic of typhoid fever occurred about

this time and gave a favorable op-

portunity to make a thorough

investigation of the Columbus water supply

question with an eye to its satisfactory

improvement. The Board author-

ized me to employ Mr. Allen Hazen of New

York . . . and after a de-

tailed study of the situation he

recommended an impounding dam in the

Scioto river with a softening and

purification plant. I think Mr. [Julian]

Griggs had previously suggested this, but

of this I am not certain . . . .

11 Charles O. Probst, Recollections and

Reminiscences of Public Health Service

and Public Health Workers, Columbus, Ohio (mimeographed for private circulation,

Columbus, 1912), 5.

326 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL

AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

Mr. Robert Jeffries, Mayor, and Mr.

James [M.] Butler, City Solici-

tor, came to my office to urge approval

of the dam alone as funds for puri-

fication were not available. Finally, we

reached a "gentleman's agree-

ment" which was later accepted by

the Board. They promised to have

prepared plans for purification works

without delay and to submit the

question of sufficient funds to install

the plant to a vote of the people. They

agreed further to use all of their

influence in support of it. They fully

carried out their promise.

Some time before the vote was to be

taken there appeared in the Ohio

State Journal a long article urging the

people to vote against this un-

necessary expense, because no system of

water purification could remove the

germs of typhoid fever or other disease

germs. This article was signed by

Dr. Starling Loving, the foremost

physician in Columbus and the Dean of

Starling Medical College, Dr. D. N.

Kinsman . . . Dr. J. F. Baldwin, Dr.

[E. B.] Fullerton, Dr. N. R. Coleman,

Dr. J. M. Dunham and Dr. Will

[D.] Hamilton; the latter with a

reservation. These were the leading med-

ical men of the city, and they did not

realize that (they were all honest

men) they were proposing to lead the

people against the most important

life saving measure Columbus ever had

before it. And this illustrates how

poorly informed about sanitary matters

were the physicians of that day,

especially the older ones who had had no

sanitary instruction.

There was but one course left -- to

educate the people. Accordingly, a

lecture bureau, you might call it, was

organized and several of us arranged

for and spoke before public gatherings

urging the people to support the

bond issue, explaining the process of

water filtration, and proving what it

had done in other places. The bond issue

was carried, and typhoid fever

has almost disappeared from Columbus.12

Out of this controversy there grew not

only the splendid

water purification plant but the sewage

treatment works and the

garbage disposal plant, all of which

have given Columbus a

sanitary control over its environment so

effective that epidemics

of cholera, typhoid fever, and

indirectly, other communicable

diseases have been reduced to a minimum

or entirely eliminated.

What happened in Columbus was also occurring elsewhere

throughout Ohio and the nation. It was a

transition period from

the old to the new. The citation of the

episode merely gives a

local flavor to a nation-wide

phenomenon.

Dr. Probst had other problems crowding

for attention. In

the first annual report of the State

Board of Health he pointed

12 Ibid., 21-3.

EPIDEMICS IN OHIO 327

out, among other things, the absolute

necessity for a compulsory

system of local organization of boards

of health throughout the

State; the dire need for an adequate

state system of vital statistics;

the obligation of the State to assist

local communities in the con-

trol of epidemic diseases; and the

indispensable requirement for

the preparation and distribution of educational

literature dealing

with the most pressing of the epidemic

diseases.

The slow development of a state system

of vital statistics in

Ohio is presented here as an

illustration of the character of the

struggles that confronted Dr. Probst in

this period. It has been

an axiom of public health that the

collection, tabulation, analysis,

and interpretation of vital statistics

is the cornerstone of success-

ful control of health conditions. Yet,

it almost passes present-

day belief that the State of Ohio took

so long to provide an

adequate system of registration.13

The act creating the State Board of

Health provided that the

Board should have supervision of the

state system of registration

of births and deaths; that the secretary

of the Board should be

superintendent of such registration; but

that the clerical work and

safekeeping of the records should be

provided by the Secretary of

State. Mr. James E. Bauman, Assistant

Director of the Depart-

ment of Health of Ohio, put this early

situation very well when

he wrote:

In commenting on the subject in his

first annual report, Dr. Probst

called attention to the gross

inefficiency and inaccuracy of the system in

use. In only one city (Cincinnati) did

the law require reports by physicians

to the Board of Health. The information

that came to the Secretary of

State was that collected by the

assessors on their annual visit on taxation

matters. The returns for 1885 showed a

death rate [for the State] of

about 10 to 1000, while the rate for

Cincinnati that year was 18.37 per

thousand, which would indicate that not

more than one-half the deaths

were recorded in the state, and accuracy

as to the cause of death could not

have reached a high percentage.

. . . In each of his annual reports and

in papers he prepared for

various meetings, the matter was

discussed.14

13 State of Ohio, Department of Health, Thirty-First

Report (43rd Year), Part I,

Report of July 1, 1915 to December

31, 1928 (Columbus, c1931), 135-7.

14 James E. Bauman, "Doctor Probst

and Public Health in Ohio," in Robert

G. Paterson, ed., Charles Oliver

Probst--A Pioneer Public Health Administrator in

Ohio (Columbus, 1934), 39-40.

328 OHIO

ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

The epidemic diseases with which the

State Board of Health

had to contend during this period were

influenza, smallpox,

typhoid fever, and diphtheria. At first,

investigations of out-

breaks of these diseases were conducted

by Dr. Probst and

members of the Board. Gradually

dependence was placed upon

various physicians throughout the State

who were employed on a

day-by-day basis. Dr. H. M. Platter of

Columbus was one of

these early diagnosticians. There was a

growing recognition of

the need for a laboratory where chemical

and bacteriological

examinations could be made. Again

dependence was upon an

opportunistic basis. Curtis C. Howard,

Professor of Chemistry

at Starling Medical College, was called

in and for several years

did all of the chemical work, Dr. J. H.

J. Upham was employed

to do the bacteriological work. He had

just come to Columbus

from Johns Hopkins Medical School where

he had studied under

Dr. William H. Welch who brought the

bacteriological laboratory

to this country from Germany.

This work grew in volume and in value to

such an extent that

the General Assembly passed an act on

April 25, 1898, which

established the chemical and

bacteriological laboratory in the State

Board of Health. The appropriation was

just sufficient to employ

a bacteriologist and equip two office

rooms as a laboratory. Dr.

Elmer G. Horton served as bacteriologist

from 1898 to 1907.

The first line of work was the examination

of water and sewage

in an effort to give the public more

adequate protection against

water-borne diseases. However, it was

only a short time until

physicians began to request examinations

for the diagnosis of

such diseases as diphtheria,

tuberculosis, and typhoid fever.

There were two other developments during

this period to

which attention should be called as

having a direct bearing upon

the control of epidemics in Ohio. The

first deals with the laws

or lack of them regulating the practice

of medicine in Ohio. Dr.

Platter has presented this situation

quite clearly in "The Histor-

ian's Note-Book" in the April 1936

issue of the Ohio State

Medical Journal. He says:

From 1833 until 1868 there was no law regulating

the practice of

medicine in Ohio.

EPIDEMICS IN OHIO 329

From

October 1, 1868, to February 27, 1896, one might practice

medicine legally upon submission of any

one of the following credentials:

First--A certificate from a state or

county medical society.

Second--A diploma from a school of

medicine either in the United

States or a foreign country.

Third--From 1880 to 1885, a diploma from a medical school issued

after attendance at two full courses of

at least 12 weeks each, and from

1885 to 1896 a diploma of graduation

from a reputable school of medicine.

During the entire period from 1868 to

1896 the continuous practice

of medicine over a period of 10 years

entitled a person to practice medicine

in Ohio.

Many times the State Medical Association

endorsed the passage of

an act to regulate practice by the state

and on February 27, 1896, the

present Medical Practice Act became

effective.

By its provisions the Governor was

authorized to appoint a board of

seven members, representative of the

schools of medicine in Ohio at that

time. No school of medicine was

permitted to hold a majority membership

on the board. As first created it was

composed of three regulars, two

homeopaths, one eclectic and one

physio-medical practitioner....

One hundred and forty medical schools

were rated as in good stand-

ing by the original board. Approximately

7,000 physicians received certi-

ficates to practice upon presentation of

their credentials and 700 more gained

a certificate by proof of 10 years

continued practice in the state ....

At present the number of men engaged in

the practice of medicine

in Ohio does not quite reach 9,000. Is

it not possible that many of the

duties and obligations imposed upon

physicians then are now being dis-

charged by other agencies? And is it not

possible that we may suffer

further encroachment into the field of

medical practice? Cultists we had

then as now; no period in medical

history has been free from them.15

The act of 1896 was a great step forward

in establishing minimum

qualifications for the practice of

medicine in Ohio. It was and

is basic to any control of epidemics by

the State.

The other development has to do with the

hospitals of the

State.

Throughout this period hospitals were viewed with

suspicion by the general public. They

were a last resort in any

kind of illness. There was a widespread

belief that if one went

in the front door of such an institution

one was sure to go out the

15 Herbert M. Platter, "The Present Ohio Board of Medical

Registration and

Licensure," in Ohio State

Medical Journal, XXXII (1936), 347-9.

330 OHIO

ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

back

door into the hands of the undertaker. Even with the in-

troduction

of cellular pathology, ether anaesthesia, and anti-

septic

surgery in the earlier period, this situation prevailed until

the end

of the era under discussion. Between 1890 and 1900 the

addition

of the laboratory to the more progressive institutions be-

gan to

change their character. Suspicion and fear began to give

way to

a feeling of trust and confidence. Epidemic diseases

which

were segregated in the old "pest houses" now were provided

with

isolation hospitals.

Table

III

EPIDEMICS

IN OHIO, 1873-1900

Year Population Disease Period

1880 3,198,062 Influenza 1879-80

Small-pox 1882-83

1890 3,672,316 Influenza 1889-91

1900 4,157,545 Diphtheria 1896

Small-pox 1898

III. Period

from 1900 to 1945--Social Organization

The

form of present-day organizations and institutions upon

which

society depends for protection against epidemic diseases

began

to be foreshadowed in the final decade of the previous

period.

In this third period the tempo of social organization in-

creased

rapidly with respect to existing organizations and institu-

tions

and by adventures into new avenues of approach to old

problems. The public generally, and the medical

profession

particularly,

gained increasing confidence in the validity of the

methods

employed. The tests were a decrease in the mortality

rates

as well as in the morbidity rates. There are presented here

a few

of the influences which have developed in this period merely

to

indicate the trends.

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis

had been, and still is, one of the outstanding

problems

for the medical profession and for society as well. In

1900 it was far and away the leading cause of death. Koch

dis-

covered

the tubercle bacillus in 1882, but the application of that

EPIDEMICS IN OHIO 331

discovery did not take place on an

effective basis until the period

under discussion. Again it was Dr.

Probst who became the leader

in Ohio against this menace. He followed

the pattern set in

Pennsylvania by Dr. Lawrence F. Flick in 1892.

In 1901 Dr.

Probst organized a state-wide voluntary

association of medical

and lay workers to employ popular

education as a means of de-

feating the "tubercle

bacillus." The Ohio Society for the Pre-

vention of Tuberculosis became the

spearhead of the movement

to control this endemic and communicable

disease.16 This use of

popular health education as a method of

attack upon a specific

disease was unique in the world. It has set the pattern for the

host of similar organizations which have

been organized since

against specific diseases or menaces to

the health of our people.

Vital Statistics

In 1908 Dr. Probst prepared the final

draft of what is now

our vital statistics law. The bill

became a law without much op-

position since the Secretary of State,

Carmi Thompson, was in

accord with the idea. The Bureau of

Vital Statistics was estab-

lished as a part of the Secretary of

State's Department until 1921,

when it was transferred to the

Department of Health. Ohio was

admitted into the United States Death

Registration area in 1911

and into the Birth Registration area in

1917. In order to become a

part of the registration area, the state

must collect records of more

than 90 per cent of its births and

deaths. So has ended the long

struggle to place this cornerstone in

the system to control epidemic

diseases in Ohio.

Vitality

Perhaps one of the most important public

health reports

issued in this country from the point of

view of its influence

upon public opinion was that made by

Professor Irving Fisher

in 1909. The document was entitled "Report on National

Vitality,

Its Wastes and Conservation." It

was prepared for the National

Conservation Commission created by

President Theodore Roose-

16 Ohio Society for the Prevention of

Tuberculosis, 1901-20; Ohio Public

Health Association, 1920-46; Ohio

Tuberculosis and Health Association, 1946--.

332 OHIO

ARCHAEOLOGICALAND HISTORICAL

QUARTERLY

velt. The burden of the prophetic argument, in

brief, was as

follows:

There is no need, however, of waiting a century for this

increase

[in the average

duration of life]. It could be obtained within a genera-

tion. Three-fourths of

tuberculosis, from which 150,000, Americans die an-

nually, could be

avoided.... From these data, it is found that fifteen

years at least could

be at once added to the average human lifetime by

applying the science

of preventing disease. More than half of this ad-

ditional life would

come from the prevention of tuberculosis, typhoid, and

five other diseases,

the prevention of which could be accomplished by purer

air, water, and

milk.17

That Professor Fisher,

at the time thought to be radical, was con-

servative in his

estimate has been demonstrated by the actual re-

sults achieved during

the period under review.

Contrasts 1910-1886

On the occasion of the

twenty-fifth anniversary of the crea-

tion of the State

Board of Health in 1910, Dr. Probst embraced

the opportunity to

contrast the health conditions in that year

against those

obtaining in 1886. He wrote:

Twenty-five years ago

the people generally paid but little attention

to health

questions. They were afraid of

smallpox, yellow fever and

cholera, and to a less

extent of diphtheria and scarlet fever, and asked

protection from such

diseases when quarantine measures did not interfere

too much with

business. Sewer gas and things and places that created bad

odors, were more

feared than disease germs.

The law authorized

council to appoint boards of health with authority

to enforce quarantine

measures for the prevention of dangerous diseases

and to abate

nuisances, but in only a few cities and villages, about 45 or

50, had this been

done. No one had authority to act in the township except

in smallpox the

trustees had certain powers.

Consumption was almost

universally regarded as an inherited disease,

and little or no

effort was made for its prevention. Even diphtheria was

still considered as a

non-communicable disease by many members of the

medical profession,

and "membranous croup" was quite generally considered

as a distinct

affection requiring no preventive measures.

The people in a

general way knew that impure water was a cause

17 Irving

Fisher, Bulletin 30 of the Committee of One Hundred on National

Health. Being A

Report on National Vitality, Its Wastes and Conservation (Washing-

ton, D. C.,

1909), 1.

EPIDEMICS IN OHIO 333

of disease, but took scant heed of the

necessity for protecting the sources

from which it came. No community had

undertaken to purify the water it

drank, nor the sewage which it turned

into the stream from which its

water supply was taken. Infected or

dirty milk as a cause of disease, and

especially its relation to infant

mortality, was scarcely spoken of outside

of medical circles. School hygiene and

medical inspection of schools had no

public support and few advocates.

There was practically no conception,

except among the few interested

in sanitary science, of the intimate

relation of sociological and industrial

conditions to health problems. Neither

the State nor the municipality felt

any special responsibility for the

health of its citizens; and the conception

that the public health is a valuable

asset and like other property should be

protected for purely economic reasons,

if for no other, was entertained by

few, and had had no public expression.

At the end of this quarter of a century

we find great changes. Health

officials with large powers and charged

with weighty duties, are a neces-

sary part of the government of every

city, village and township.

Antitoxin for the cure and prevention of

diphtheria, unknown twenty-

five years ago, is now, through the

agency of the State Board of Health,

within easy reach of every physician in

the State, and is supplied free to

the poor and needy.

Tuberculosis is being fought everywhere.

A State Sanatorium has

been provided for the cure of its

victims, and many county and district

hospitals have already been established,

with others under way, for the

care of advanced cases.

A state society (organized in the office

of the State Board of Health)

and many local tuberculosis societies

are engaged in combating this disease.

Ohio has become a leader in the

protection of its water supplies, and

its fame in this direction has spread to

most parts of the world. The

State, through its State Board of

Health, has entered upon a policy which

will prevent further injurious

contamination of its streams and lakes

and must eventually free them from all

sources of defilement.

The purity of milk supplies, once

unquestioned, is receiving more

and more official and public attention.

Great gains have been made in

school hygiene and school sanitation.

Medical inspection of schools, now

authorized everywhere, has been

undertaken in most of our larger cities.

The most hopeful sign of advancement is

the change in opinion as re-

gards health matters. Indifference, and

even, to some extent, hostility has

been replaced by keen interest and a

desire for help.

Twenty-five years ago a visit by a

representative of the State Board

of Health was often looked upon as an

unwarranted interference and a

334 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

reproach to the community where this was

necessary. Today the difficult

is adequately meeting the many demands

for such assistance.

Public education in health matters has

been immeasurably extended.

Hygiene is taught in all schools; the

press and lay magazines are devot-

ing

more and more space to health subjects.

It is only by thus contrasting

conditions as they were in 1886 with

what may be seen today that a fair

estimate can be made of our growth in

power and service in protecting the

public health.

Much of what has been done must be

regarded as simply the founda-

tion, soon to be buried, upon which will

rest the magnificent superstructure

which should, and we trust will, be

erected. The future should see the

sovereign state chiefly concerned

about the health of its subjects.

The next quarter of a century should

bring about immense improve-

ments in the public health.18

Medical Education

In 1910

Dr. Abraham Flexner issued a report on

medical

education in the United States and

Canada based upon a survey of

the medical schools as they were

operated. Flexner pointed out

that among a total of 155 medical

schools in these two countries--

a larger number than existed in the rest

of the world--only a

small fraction provided proper medical

training. Less than a

third were integral parts of

universities.19 This report had a

tremendous effect upon medical

education, and Ohio did not

escape its impact.

Out of the 140 medical schools

recognized by the Ohio State

Medical Board in 1896 there were 26 in

Ohio whose diplomas

were recognized. Today there are but three medical schools

in

the State, each an integral part of a

university.

United States Public Health Service

No account of the efforts put forth by

Ohio to control

epidemic diseases would be complete

without taking into account

the development of the United States

Public Health Service.

18 Twenty-Fifth

Annual Report of the State Board of Health of the State of

Ohio for the Year Ending

December 31, 1910 (Columbus, 1911),

5-7.

19 Abraham Flexner, Medical Education in the

United States and Canada. A

Report to the Carnegie Foundation for

the Advancement of Teaching. Bulletin No. 4

(New York, 1910), passim.

EPIDEMICS IN OHIO 335

Until 1912 the earlier Marine Hospital

Service (1798), later

the Public Health and Marine Hospital

Service (1902), was ex-

clusively a medical relief and

quarantine agency. In that year

the beginning was made for providing on

the federal level a public

health organization which has since

grown into an effective safe-

guard against epidemic diseases being

introduced from outside

the United States as well as exercising

control over interstate

communication of epidemic diseases.20

State Department of Health

The laws of Ohio relating to the

organization of the State

Board of Health received a thorough

overhauling at the hands

of the General Assembly in 1917. There

emerged essentially the

present form of organization which is

known as the Department

of Health of Ohio.21

Influenza Epidemic

In 1918-19 there occurred in Ohio and throughout the world

the pandemic of influenza. This epidemic

nearly reproduced the

same degree of fear and social disorganization

that had been

produced by the previous cholera

epidemics. A high mortality

rate and an enormous amount of illness

forced upon every one ??

realization of the thin dividing line

between the years of com-

parative good health and the sudden onset

of a devastating

epidemic.22 As one outcome of

that epidemic, the General As-

sembly in 1919-20 completely revamped the ancient system of

local health organization in Ohio. A reduction from 2,150 local

health units to some 200 was effected.23

There is discernible in this period a

gradual shift from

etiology to therapeutics. The exploration of the gross patho-

genic microorganisms gradually exhausted

itself under the pat-

tern laid down by Pasteur and Koch. We

are today face to face

with the virus diseases which have not

yielded thus far their

20 Cf. H. S. Mustard, Government

in Public Health Commonwealth Fund

(New York, 1945).

21 Ohio Laws, CVII,

522-5.

22 Forrest

E. Lindner and Robert D. Grove, Vital

Statistics Bates in the United

States, 1900-1940 (Washington, D. C., 1942), passim.

23 Ohio Laws, CVIII,

Part 2, 1085-93.

336 OHIO

ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

full

secrets. Astonishing discoveries in the

field of chemo-

therapy

are at the moment holding the center of attention. The

speed

with which the sulfa compounds, DDT, penicillin, and

streptomycin

have become common in popular discussion is al-

most

breath-taking. The next shift may be in the field of physics

as we

speculate concerning the application of atomic energy to

the

realm of medicine.

Table

IV

EPIDEMICS

IN OHIO, 1900-1945

Year Population Disease Period

1902 4,321,527 Small-pox 1901-3

1905 4,458,354 Small-pox 1905-13

1919 5,683,124 Influenza 1918-19

1921 5,921,257 Diphtheria 1921

1923 6,182,537 Influenza 1921-23

1926 6,503,581 Measles 1926

IV.

Future Outlook

As we

look back over the long trail that epidemic diseases

have

blazed in Ohio there are certain broad trends which seem

to

mark the reasons for the decline of such diseases. There has

been

an amazing growth in scientific knowledge in the areas

of

etiology and therapeutics. There has been an equally astonish-

ing

improvement in medical education, in hospitals, and public

health.

There has also gone along with these improvements an

unprecedented

diffusion among all the people of better standards

of

daily living.

There

has never been in the history of the world such a

vast

migration of human beings from the temperate zone to the

torrid

zone and even to the arctic zone as we have witnessed

within

the past seven years. Nor has there been less threat from

epidemics

to the lives and health of our people.

If ever we

needed

a demonstration of the degree of our control over such

diseases,

we have just lived through one never equalled in the

world

before.

But

to say this is not without recognizing that there are

many

unsolved problems before us. The discovery of a specific

EPIDEMICS IN OHIO 337

for tuberculosis or a complete

understanding of the virus diseases

or the cause of cancer may be right

around the corner.

If we can project ourselves into the

future on the basis

of our present knowledge and past

experience in the control of

epidemic diseases it seems. clear we

shall follow somewhat along

the following lines:

I.

Organization of research coordinated closely on a

national basis.

II.

Extension of conditions for the establishment of

higher standards of living for all our

people.

III. Synthesis

of our present separate entities of medical

school, laboratory, hospital, and public

health organiza-

tion within a university to comprehend a

truly theore-

tical and applied biological science.

IV.

Integration of our local, state, and federal public

health services.

V.

Improvement in technics and content of health educa-

tion both on an individual and mass

basis.

As Pasteur himself said at the evening

of his long and use-

ful life, "Much has been done; but

there is still a great deal

to do." And the people of Ohio must

needs join in the doing.

A CLEVELAND DRUG STORE OF 1835

by HOWARD

DITTRICK, MD.

Editorial Director, the Cleveland

Clinic, Cleveland

This presentation outlines many

activities of an early Cleve-

land druggist with some mention of

contemporary patrons and

customs. The information is based upon a

manuscript volume

which was presented recently to the

Howard Dittrick Museum of

Historical Medicine in the Cleveland

Medical Library. Written

in long hand, the book deals with drugs,

medicine, and a number

of things, with brief reference to

persons who have previously

owned the book.

The title page reads "E. F.

Punderson, Receipt Book, Cleve-

land, January 7, 1835." The book is

6 x 4 inches in size, the back

is broken, and one cover has

disappeared. The 220 pages are

much yellowed with age, but the ink

remains distinct and the

writing clear and legible. Written after

the manner of some

oriental manuscripts in which one book

is written from before

backward and the other from behind

forward, the first part deals

with medicine and prescriptions and the

other with veterinary

medicine, husbandry, and home economics.

The information contained in the

manuscript was assembled

during an era when difficult and

uncertain transportation of nec-

essary medicines led to the establishment

of drug stores in the

more populated centers along waterways

and overland trails. Often

these drug depots were found in the

general store or in the post

office. Here the doctor came on

horseback to replenish his saddle-

bags with crude drugs, a few liquids,

and some powders. Not

infrequently the doctor dispensed

remedies from an assortment

of as many as one hundred and fifty

preparations. When time

and distance permitted, he instructed

his patients to procure their

medication from the nearest drug shop.

Dr. David Long, the first physician in

Cleveland (1810), is

said to have opened the first drug store

of the settlement adjacent

338

CLEVELAND DRUG STORE 339

to his home on Superior Street. Two

other drug stores were

added on the same street in 1831, the

Aaron Tufts Stickland

(later the Gaylord store), and the

Handerson and Punderson

stores.

Lewis

Handerson, senior partner in the latter store, was born

in 1806 in Columbia County, New York.

Upon completing his

training he sold drugs in New York City. In 1831,

he and the

son of one of his former preceptors in

Hudson opened the Han-

derson and Punderson drug store in

Cleveland. They conducted

a progressive store, for in 1833 they

advertised stethoscopes for

sale.

Handerson married Punderson's sister and, having no

children, he adopted two orphaned

children of his brother,

Thomas. One of these children was Dr.

Henry E. Handerson

(1837-1918), who fell heir to the

manuscript under consideration

upon the death of Punderson. Mrs. Henry E. Handerson pre-

sented it to the Dittrick Museum.

A word about this Henry E. Handerson.

Upon graduation

from Hobart College he wrote in Greek a

thesis on Socrates which

I had the opportunity to examine. The

meticulous care and neat-

ness displayed reminded me of the

manuscript of Benvenuto

Cellini's autobiography in the Laurentian Library in Florence.

After graduation Handerson spent two

years studying medicine

under a private tutor in Louisiana. At

the outbreak of hostilities

in 1861 he enlisted in the Louisiana

Volunteers and was made a

captain two years later. He was captured

at the Battle of the

Wilderness in 1864 and remained a

prisoner until June 1865. He

resumed medical study and graduated from

the College of Physi-

cians and Surgeons of New York in 1867

and practiced there

until he came to Cleveland in 1885. A successful

practitioner

and earnest scholar, he left a deep

impression upon cultural medi-

cine in Cleveland. His translation of J.

H. Baas' Outlines of the

History of Medicine, with his own flavorful footnotes, remains a

classic in its field. A chapter on

medicine was written by him

for S. P. Orth's History of Cleveland

(1910). Another work

Gilbertus Anglicus, was published after he had lost his sight.

Such, then, is the family history of

this book.

340

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL

QUARTERLY

Today through innumerable channels we

are bombarded with

varied instructions for everyday living,

all of which we accept as

; matter of course. In pioneer days those living in isolated com-

munities had to pool such useful

information. The general store,

the tavern, or the drug store was a

clearing house for such data

to meet the needs of the settlers. Folk

medicine, founded upon

the test of trial and error, thrived and

often was sufficient unto

the day.

Books were scarce and when purchased

they had to be trans-

ported to the Western Reserve by boat

and by horseback from

Pittsburgh or even from Philadelphia. The druggist supple-

mented his knowledge of drugs by keeping

a record of recipes

and practical suggestions for ready

reference. This manuscript

was such a record. The entries began on

January 7, 1835, and

the last date mentioned is December

1857, about six years after

Handerson retired.

Like the cookbook of an old housewife,

it is badly worn with

use and is interleaved with clippings,

in this case chiefly patent

medicine testimonials. Among them is

noted a "Pain Extractor"

which promised to cure as by magic,

"burns, chronic diarrhea,

inflammatory rheumatism, salt rheum

(eczema), inveterate sores,

swelled and broken breast, and spavin

lumps in horses. . . . A lady

in Syracuse, who had lost two fingers by

felons, was attacked by

another; she applied the Extractor and

repelled the enemy. Mr.

Swartz, Lydius Street, Albany, chopped

his four fingers nearly

off. His brother cut an enormous gash

above his knee. His

child was horribly burnt, and his horse

had a dangerous cut. In

every case the Extractor was applied and

cured all as by magic."

Many of the drugs employed in the

various formulas re-

corded in the book are still employed

more or less frequently.

Were it not that so many preparations

are now compounded by

manufacturing concerns and supplied to

the trade under a pat-

ented name, we would be familiar

with most of the individual

drugs in Punderson's prescriptions.

In addition to counter prescribing and

compounding prescrip-

tions, the druggist of 1835 was his own

specialty manufacturer.

CLEVELAND DRUG STORE 341

He made court plaster (both black and

flesh-colored), corn plaster,

wart remover, adhesive plaster, perfume,

tooth paste, shaving

liquid, shaving cream, hair remover,

hair tonic, and many hair

dyes, one of which contained hartshorn,

nitrate of silver, and

rain water. He was also prepared to

furnish the customer with

any kind of animal oil desired. Buffalo

oil, for example, was

made of lard oil, perfumed with equal

parts of oil of lavender

and oil of lemon. Although it is not

mentioned the accommo-

dating druggist doubtless could extract

from the same jar those

popular old medicinal fats, goose

grease, dog grease, and bear

grease.

Care of livestock frequently demanded

the druggist's atten-

tion, especially since there were few

veterinarians at the time.

John Baird appears as the sole

veterinary surgeon in the Cleveland

Directory for 1837. I remember as a boy being warned against

giving a horse cold water when he was

still hot after a workout,

lest he be foundered. In the Punderson

manuscript directions

were laid down for treating the stiff

joints of the foundered

horse. The formula and method of

compounding drenches, em

brocations, washes, and blisters for

horses were given in detail.