Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

DR. JOHN LOCKE, EARLY OHIO SCIENTIST

(1792-1856)

by ADOLPH E. WALLER

Associate Professor

and Curator of the Botanic Garden.

Ohio State University

The nineteenth century in the United

States suddenly swung

into its expanding programs of research

and education. No one

was prepared for the impact of the

increasing realization of the

power over nature which man now

possessed. The illusion of

the perfectibility of all men through

knowledge stretched un-

dimmed. The inherent weaknesses of man

and the snail's pace

of education were not yet perceived.

Gigantic discovery was so

close at hand that no one troubled to

consider disappointments as

more than temporary obstacles. A little

proficiency in mathe-

matics, languages, and the law marked

the educated man. Scien-

tific training was unknown. Science

laboratories were just start-

ing and the skills and techniques they

were to impart were born

on the spot.

The thesis that the medical colleges of

the time were the

sources of our trained scholars in the

natural sciences has been

stated in previous papers in this

series. Three months at "Cam-

bridge College" prepared Dr. Samuel

P. Hildreth for his degree

in medicine, after an apprenticeship

with practicing physicians.

Many others were likewise briefly

exposed to formalized study.

Dr. John Locke was more fortunate. His

formal training lasted

about three years.

Philadelphia and Cincinnati were early

in asserting leader-

ship in the quality of medical training

offered. Many of the

students trained in medicine were not as

interested in its practice

as in following the leads offered by

their training in sciences. Our

outstanding botanists and geologists of

the 1830's were thus

educated. Dr. Locke's story follows a

similar pattern with the

difference that he added physics to his

earlier inclinations toward

botany and geology. Perhaps it was from

his keen observation of

346

DR.

JOHN LOCKE 347

the

applications of botany to both medicine and agriculture. John

Locke's

father also contributed to his son's interest in the sciences.

Samuel

Barron and Hannah Russel Locke, John's parents,

had

lived at Lempster, New Hampshire, and Fryeburg, Maine,

before

going to settle near Bethel, Maine, on the Androscoggin

River.

John was then four years old. It was a choice location

for

the skilled artisan, Samuel Locke. There was a large tract

of

land to be purchased there. There was water power to operate

his

own saw- and grist-mills. There he built a shop which made

him

the outstanding millwright of the region. A number of

people

settled nearby and were given work in the mills and shop.

The

settlement came to be called Locke's Mills.

Here

young John grew up and received his early schooling

which

was supplemented by the varied assortment of books that

his

father's library offered. As the

community prospered a

Methodist

Meeting

House and other establishments were added.

For

all of his skill as a machine builder in a young country hungry

for

machines the senior Locke found time to teach handicrafts,

mathematics,

and some languages to his son. He was also able

to

send him to Bridgeport, Connecticut, to attend an academy

where

he obtained the usual classical courses of study. John

roamed

the area collecting plants and hunting. It was a sad mo-

ment

of realization for the father when young Locke decided he

was

not longer content to stay in Bethel to do what his father

had

successfully accomplished. John was eager to study medi-

cine

and began at Bethel in 1815 and shortly afterward with

Dr.

Twitchell at Keene. New Hampshire.

A fragment of a

diary

shows the determination of a rebellions young citizen forced

by

his own decree away from his father's abundance:

July 15, 1815. Left

Bethel,

arrived at Keen, Aug.15

Oct.

20, left Keen for New

Haven tarried in northfield.

Oct.

25, Northfield to West

Springfield Expenses $0.85

Oct.

27, Thence to Weathersfield do $0.72

Oct.

28, From Weathersfield to New Haven

" $0.90

$2.47

DR. JOHN LOCKE 349

The journey was performed on horseback

and it will be thought sur-

prising that no more expense was

involved. Economy was the object as

I had, I thought, hardly money enough to

bear my expenses at college.

I ate milk, with sometimes a piece of

apple pie with it only twice a day.

Oct. 29 went to church in the chapel.

Oct. 30 attended Professor Silliman's

lecture on chemistry.

A search made for a youthful portrait of

John Locke has

not been successful. A portrait of him

as a man about 50 years

of age shows a large, somewhat spare

figure with a thin face and

prominent cheek bones. He is said to

have had clear blue eyes of

an unusually sparkling quality. It is

doubtful if the active stu-

dent at Yale could have maintained his

Spartan diet for long. He

became Dr. Silliman's assistant. With

that great man's recogni-

tion there was undoubtedly some means of

subsistence provided.

Besides, there may have been money from

home.

Conversations with Silliman offered

mental pabulum of a

stronger sort. John was fired to emulate

his chief in travels in

Europe and other places. He began by a

visit, in the summer of

1816, to Dr. Nathan Smith, the eminent

founder of Dartmouth's

Medical School.

At Hanover he met also young Dr. Solon

Smith who was

struggling toward an education and

toward increasing knowledge

in a field of special interest to John.

They had to become ac-

quainted first in order to feel free to

exchange ideas which were,

perhaps, a little strange and not too

welcome to some of their

elders and preceptors. They both wanted

to know how to identify

plants. This was the common bond. Solon

Smith owned a book

they would both try to study. It was Dr.

Jacob Bigelow's Plants

of the Vicinity of Boston, a new book, the first edition having

been published in 1814. Presently it was

to become the favorite

New England version of the artificial

system for naming plants,

better known as the Linnean system. The

system following nat-

ural orders and families was still

regarded as revolutionary. It

was some years before the North American

flora would be so

classified by Torrey or Gray. Jacob

Bigelow's book was there-

fore well known and twice was revised

and enlarged. The third

edition appeared in 1840, still

demonstrating its usefulness to

350 OHIO ARCHNEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL

QUARTERLY

amateur botanists. Dr. Bigelow's

scientific reputation rested on

his lectures at Harvard and on his

contributions to the United

States Pharmacopoeia. His Plants of

Boston was known as the

most popular manual of its day.

What could not be accomplished by Solon

Smith alone,

namely, rouse an interest among

Dartmouth students in plant

studies, Locke and Smith together were

able to do. Soon they

had a number of the students tramping

the hills around Hanover

in search of specimens. To the delight

of Dartmouth's medical

college faculty, particularly to Nathan

Smith, these became regu-

larly organized field trips.

Back in New Haven the best parts of the

next two years

were busy ones for Locke who continued

to assist Dr. Silliman

in chemistry and at the same time

continued his plant studies

with the help of Dr. Eli Ives. He

lectured in Portland, Boston,

and Salem, and at Dartmouth and Yale.

Probably with the en-

thusiastic backing of Dr. Nathan Smith

he was offered a curator-

ship of the Cambridge Botanical Gardens

by Dr. Jacob Bigelow.

It seems, however, he was able to remain

there only a short time,

though not for lack of botanical

qualifications. He was too out-

spoken on religious subjects for the

peace of mind of some of the

members of the Cambridge group. It is

recorded, however, that

he had been most pleasantly welcomed by

Harvard's president,

John Thornton Kirkland, who found Locke

sufficiently engaging

to pay him the compliment of offering to

study botany with him.

Though not yet equipped with his medical

degree he was

ready to combine medicine and botany on

an expedition. The

United States Frigate Macedonian was

to sail under special orders

to explore the Columbia River. It was to

leave Boston Harbor

on September 20, 1818. What an

opportunity for Locke, prob-

ably still smarting a little from having

lost his curatorship! He

was warned that he would be badgered as

a landlubber, a down-

east country boy, and a noncombatant.

Perhaps most of all the

rugged seamen would resent the presence

of a young intellectual.

If tempers really broke he would have to

stand in an "affair of

honor" of large or small

consequence.

DR. JOHN LOCKE 350

When Locke appeared on board the Macedonian

he was ac-

companied by a long mahogany box

somewhat resembling a sur-

geon's amputating case. This he

contrived to drop on the deck

in such an awkward manner that the lid flew

open exposing a

beautiful and complete outfit of dueling

pistols. He was invited

to join when pistol practice for the

officers was announced. His

skill in hitting any spot selected upon

the targets convinced the

crew that the surgeon's mate was a man

who knew how to handle

small arms. He was no longer a stranger

of uncertain position

on shipboard.

Sailing orders for the Macedonian brought

her off the Caro-

lina coast in time to meet a West Indian

hurricane of great vio-

lence. She was dismasted and so beaten

by the waves as to be

almost destroyed. After the storm she

limped slowly back to

Norfolk. Upon deliberation, the Navy

abandoned the Columbia

River operation. Locke applied for his

discharge and made his

way back to New Haven as quickly as he

could. life on the sea

was a gamble. Others might take it if

they chose. For him there

was other work.

He set in at once to complete his

requirements for a medical

degree at Yale and in 1819 was graduated

with the sixth class.

Dr. Eli Iyes taught Materia Medica and

Botany, the usual ar-

rangement made in the medical curricula

of that period. He had

a reputation for scholarship and had

published a brief list of the

plants of New Haven as early as 1811.

This was later extended

with the help of his students to more

than a thousand plants. Also

at his own expense he had set out a

botanical garden near the

college.1 Locke must have spent a great

deal of his time in study-

ing the collections and he resolved to

prepare a manual for

students which would quickly familiarize

the beginner with the

meanings of terms used in

classification.

To prepare the illustrations for this,

Locke learned the art

of engraving. His father's careful

instructions in the use of

tools served him well, and his own

skills and desires as a crafts-

1 Andrew D. Rodgers, "Noble

Fellow" -- William Starling Sullivant (New York,

1940), 81,

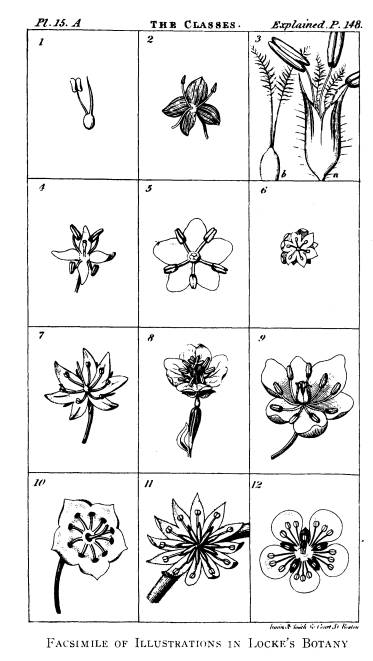

146 EXPLANATION OF

PLATES.

PLATE 15. A.

CLASSES--See

Frontispiece.

This plate contains a figure of a flower in each of

the 24

Classes. With the exception of 1, 9, and 23,

they are either native or commonly

cultivated.

Fig. 1. Monandria, 1 stamen;

Mare's-tail, Hippuris

culgaris. Native of Britain.

This is an example also of the order Monogynia, having 1 pistil.

2. Diandria, 2 stamens; Speedwell, Veronica.

3. Triandria, 3

stamens; Common Timothy-

grass or Herds-grass, Phleum Pratense,

much magnified.

a. The entire Floret, having three

stamens and two

feathered styles projecting from the two

compressed

glumes which enclose them at the base.

b. The Pistil shown separate, consisting of the germen

and two feathered styles.

This is an example also of the order Digynia,

having 2 styles.

4. Tetrandria, 4 stamens; Cornel, Cornus

pani-

culata, somewhat magnified.

5. Pentandria, 5 stamens; Common Elder,

Sam-

bucus niger, magnified.

It is an exemple also of the order Tryginia,

having three sessile

stigmas.

6. Hexandria, 6 stamens; Barberry, Berberis

culgaris.

7. Heptandria, 7 stamens; Chickweed

winter-

green, Trientalis Europeus.

8. Octandria, 8 stamens; Dwarf tree

primrose,

(E1nothera punnila.

9. Enneandria, 9 stamens; Flowering Rush,

Butomus umbellatus. Native of Britain.

This is also an example of the order Hexagynia,

having 6 pistils.

10. Decandria, 10 stamens; Broad-leaved

Lau-

rel or Lamb-kill, Kalmia latifolia.

11. Dodecandria, 12 to 19 stamens;

Houseleek,

Sempervivum tectorum.

FACSIMILE OF EXPLANATORY PAGE FOR

ILLUSTRATIONS

354 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

man enabled him to complete his

task. It was a teaching aid

not paralleled in the United States. The

Linnean system of

classification was illustrated with

examples of North American

species. These would be readily

obtainable for class use. The

descriptive writing of Jacob Bigelow's

book was supplemented

by figures

of the plants which beginners could not fail to grasp.

The dedication of Locke's Outlines of

Botany was to "Jacob

Bigelow, Rumford Professor of Materia

Medica, Harvard." In

his preface he separates elementary from

practical work and

characterizes his work as showing the

same difference that a dic-

tionary or grammar woull bear toward

works of history or

poetry.

His raison d'ctre gives the following recommendation to

plant study: (1) medicine, the arts, and

agriculture depend upon

it; (2)

it is a rich source of pleasure; (3) it

affords discipline

by means of which methodizing a subject

and analyzing it may

be learned; (4) it offers spiritual

inspiration. "The study of

nature is the elder scripture written by

the hand of the Creator."

Instructors of botany today will take

heart in the following item

from his preface: "From what little

experience I have had in

instructing I cannot recommend to

teachers to oblige their pupils

to commit any of the following pages

formally to memory, in do-

ing which they are by no means certain

to get the ideas."

Published in Boston in 1819, this work

must have come to

Dr. Bigelow's notice and won the

approval of President Kirkland.

When Dr. Bigelow brought out his second

edition of the Plants

of Boston (1824), he might well have used Locke's illustrations.

An excellent teaching, manual redounding to the credit of both

Locke and himself would have been the

result. By this time

Locke was in Ohio where other interests

were crowding into his

busy life. Bigelow's second edition was

too late for him. An

associate of Locke said of him that:

Scarcely four years had elapsed since he

left the valley of the

Androscoggin a plain country boy, and

yet, within that time he had

secured the favor of distinguished men,

had received the appointment of

Assistant Surgeon in the Navy, had

become a Doctor of Medicine, an

author of a popular scientific work, a

teacher and lecturer in colleges, not

DR. JOHN LOCKE 355

only to pupils but to professors. All

this was accomplished without one

dollar of patronage or support except

that created by his own exertions.2

He was not to find a remunerative

medical practice however.

Things might have been different had he

remained aboard ship

or had he read medicine under a

physician. Medical colleges

offered no instruction in dealing with

patients, and the hard life

and meagre living of a country doctor

offered little to attract him.

He accepted the position of assistant to

Colonel Dunham who was

the proprietor and head of an academy

for girls at Windsor,

Vermont. Here his gifts as a teacher

could again shine forth.

When Colonel Dunham developed the plan for establishing a

similar school in Lexington, Kentucky,

Locke agreed to go there

for that purpose. He felt that New

England was dominated by

religious intolerance and he preferred

to live in another part of

the country.

A boyhood memory was a probable factor

in this decision.

His father had built a Methodist Meeting

House at Locke's Mills

giving both land and materials for

construction. By an old

Massachusetts law, which applied in

Maine as part of Massachu-

setts, a tax for the support of the

prevailing sect was levied on

members of other sects unless exempted

by payments to the sup-

port of their own denomination. Locke,

Senior, refused to qual-

ify under the exemption clause and also

refused to pay the asses-

sed cash tax because of his donations.

He regarded the law as

invasion of religious liberty. John

witnessed the officers of the

law driving away cattle from his

father's farm, having seized

them in lieu of tax money. This

injustice so strongly impressed

itself upon John that he determined he

would some day live in a

place where there was less upholding of

the letter of religious

administration and greater tolerance for

human rights.

Since Colonel Dunham's plans had

altered, Locke came to

Kentucky alone and founded the Lexington Academy in 1821.

Little is known about the Kentucky

school. He may have made

some important acquaintances in

Lexington. It probably served

2 M. B. Wright, An Address

on the

life and Character

of the Late Professor

John, Locke (Cincinnati,

n. d.), 14.

356

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL

QUARTERLY

as a means of establishing Locke as an

educator in that section

of the country. It likewise was the means of bringing

him one

step nearer establishing his residence

in Cincinnati which was to

become his permanent residence.

One authority wrote:

He began his work in Lexington, Ky., in

1821 and soon evinced his

superior talents as a teacher. In 1822

Locke had occasion to visit Cincinnati,

making the trip from Lexington on

horseback. "As he emerged from the

woods of Kentucky, and rose over the

hill south of Newport, the valley

surrounding the now Queen City opened to

his admiring view. On approach-

ing the city the rattling of drays, the

clink of hammers, the smoke of

factories, the rush of steamboats, the

firing of signals of arrivals and

departures, acted upon his mind with all

the force of enchantment. He fell

in love with the Queen City and decided

to make his home here." Ethan

Stone, that remarkable pioneer and

philanthropist, took an interest in the

young stranger and aided him in

establishing a non-sectarian school for

young ladies (Dr. Locke's School) which

enjoyed a great reputation for

many years and was patronized by the best

people. The school was located

on the east side of Walnut Street,

between Third and Fourth Streets.3

Other friends soon included the

ministers of several denom-

inations of churches in Cincinnati. Dr.

Joshua L. Wilson and Dr.

Ruter, whose daughter became a pupil of

Locke's school. There

was no concealment or evasion in respect

to moral or religious

instruction in Locke's academy. None was offered, teaching be-

ing construed as secular. Yet he was

firm in making opportunities

to "impress on the minds of these

pupils the great principles of

religion, the existence and attributes

of Diety, the expedience

and necessity of cultivating social

virtues. Open your school

then that it may be patronized by all

denominations," said Dr.

Ruter, "and great good will

result."

In a History of Cincinnati and

Hamilton Country is the fol-

lowing statement concerning Locke's

school:

In 1823, Dr. John Locke, a man of

science and of some progressive

views in education, organized in

Cincinnati a private school for girls,

under the name of Locke's Female

Academy. In this school, as in others

established about the same time in the

Ohio Valley, some of the methods

of Pestalozzi were followed. It is

interesting and suggestive to reflect

3 Otto Juettner Daniel Drake and His Followers (Cincinnati, 1909), 156.

DR. JOHN LOCKE 357

that just at the time when the old Swiss

reformer was nearing the close

of his life, dejected from the apparent failure of his toils,

enthusiastic

teachers on the banks of the Ohio river

were putting his wise advice into

practice.4

A

family weekly magazine published at the time praised the

school thus: "It was truly

gratifying to witness the rapid im-

provements of the pupils generally, in

all the branches of science

taught in this institution, and more

particularly in those of Natural

and Moral Philosophy and Botany."5

During the twelve years

of Locke's proprietorship somewhere near

four hundred pupils

received an education in the school.

Mentioned for high attain-

ment in the early days of the school

were Amanda Drake, Mary

Longworth, Sarah and Jane Loring,

Frances Wilson, Jane Keyes,

Eliza Longworth, Selima Morris,

Charlotte and Mary Rogers,

Elizabeth Hamilton, and Julia Burnet.

Mrs. Trollope who usually displayed

unlimited irritation in

her criticism of Cincinnati and its inhabitants gave some space to

the school following her attendance at

one of the commencements.

She described Dr. Locke as a

gentleman who appears to have liberal

and enlarged opinions on the

subject of female education . . . [and]

perceived, with some surprise, that

the higher branches of science were

among the studies of the pretty crea-

tures I saw assembled there. ... 'A

quarter's' mathematics, or 'two quar-

ters' political economy, moral

philosophy, algebra and quadratic equations,

would seldom, I should think, enable the

teacher and the scholar, by their

joint efforts, to lay in such a stock of

these sciences as would stand the

wear and tear of half a score of

children and one help.6

However, Mrs. Trollope's judgment has

been seriously

questioned. liven her own son, Anthony, wrote of her that "no

observer was certainly ever less

qualified to judge of the pros-

pects or even of the happiness of a

young people."7

Contemporary writers in Cincinnati

agreed that Mrs. Trol-

lope and her English friend, Miss

Frances Wright, stirred a great

deal of discussion because of their

unconventional attitudes.8 In

4 History of Cincinnati and Hamilton County,

Ohio, Their Past and Present

(Cincinnati, 1894), 100.

5 Cincinnati Literary Gazette, July 31, 1824.

6 Frances Trollope, Domestic Manners

of the Americans (London, 1832), 114-5.

7 Anthony Trollope, Autobiography (New

York, 1905), 156.

8 John P. Foote, The Schools of Cincinnati

and Its Vicinity (Cincinnati, 1855),

64-5.

358 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL

AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

spite of bitter opposition they probably

caused people to think

about some of the current problems of

education and they may

have led the way to reform. Locke's

school is noteworthy be-

cause it was turned definitely toward

the concepts of modern

education. During its fourteen years, it

would have established

Dr. Locke's reputation if he had never

engaged in any other

occupation. He became famous for simple

lucid exposition. His

method of asking questions designed to

inculcate thinking habits

made the school known throughout the

nation.

His methods were based on the principles

of Pestalozzi.

During his brief association with

educational methods while at

Windsor, Vermont, and his attempt to

work alone while at Lex-

ington, he must have had an opportunity

to try several methods.

There is also the possibility that he

met Dr. Joseph Buchanan

while in Lexington, acquiring from this

original, though some-

what frustrated genius, the firm

conviction that mathematics and

science should become a part of a

liberal education. If Locke's

school was not the first in the United

States to try the Pestaloz-

zian method, it was certainty the first

of such schools in the Ohio

Valley.

When Dr. Daniel Drake later turned to educational

problems he failed to acknowledge

Locke's plan probably because

Locke had left his school and was a

professor in the Ohio College

of Medicine, a rival of Drake's

Cincinnati College.

Dr. Locke also began lectures in the

Mechanics' Institute. He

is credited with being one of the early

workers or founders of.

that valuable source of instruction. He

began the lectures in his

own home and, when that became too

crowded, gave them in a

building on Walnut Street occupied by a

Baptist congregation.

Later, after Mrs. Trollope's financial

debacle the Institute occu-

pied her bazaar.

In 1825, John Locke was married into one

of Cincinnati's

distinguished families. Mary Morris, of

Newark, New Jersey,

and niece of Nicholas Longworth, became

his bride. In the course

of time six sons and four daughters were

born.9 More

and more

9 George M. Roe, Cincinnati:

The Queen City of the

West (Cincinnati, 1895),

360.

DR. JOHN LOCKE 359

John Locke was devoting time to his own

investigations in elec-

tricity and less to the preparatory

school. He was ready in I835

to accept an appointment as Professor of

Chemistry in the Medi-

cal College of Ohio. He also was

becoming interested in geolog-

ical studies.

Probably his first interest in

geological questions had come

from being asked to make chemical

analyses of various minerals

submitted to him. The other possibility

is that he had privately

begun some surveys of his own, the

direct result of his student

days when he had served as assistant to

Professor Silliman. His

lectures at the Mechanics' Institute

would have promoted an at-

tempt to keep abreast of new

publications. He may also have met

Dr. Samuel P. Hildreth at some of the

medical meetings begin-

ning to be held at that time. Dr.

Hildreth had been writing on

the geology of Ohio and publishing,

among other places, in Silli-

man's Journal as the American

Journal of Science and Arts was

popularly known. Dr. Hildreth had also

served as chairman of

the governor's committee to report on

the best method of obtaining

a complete geological survey of Ohio.10

Dr. Locke contributed to the Second

Annual Report of the

Geological Survey, along with Charles Whittlesey, J. W. Foster,

Caleb Briggs, and Dr. J. P. Kirtland,

with W. W. Mather as Chief

Geologist. Dr. Locke's report was the

last one received as he

was lecturing and traveling in England

during I837. His open-

ing sentence shows his eminently

practical point of view and his

desire as an educator to reach his

public. "As the geological re-

ports are intended, in part at least,

for the distribution of useful

information among the people, it will be

necessary to introduce

occasionally, though briefly as

possible, such elementary explana-

tions as will enable them to understand

the subject discussed."11

He was assigned the southwestern quarter

of the State. He be-

gan with the chemical analysis of the

limestones which had been

included in the first report of the

committee as well. The lime-

stones were not fully classified as they

are at present, of course,

10 Report of the Special Committee .

. . on the Best Method of Obtaining a

Complete Geological Survey of the

State of Ohio (Columbus, 1836), 15.

11 Ohio Geological Survey, Second

Annual Report on the Geological Survey of

the State of Ohio (Columbus,

1838), 203.

360

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

and he simply states them by color as

"blue limestone" or as "cliff

limestone." The latter derived its name originally

from early

reports of surveys made in Scotland. It

was the general name

for limestones forming cliffs. Locke

wrote:

In accordance with this nomenclature a

creek which falls into the

Ohio below Madison (Ia.) [Indiana] and

makes in its course some magnifi-

cent leaps cover the cliff limestone has

received the name of "Clifty Creek"

and the cascade that of "Clifty

falls," the / being added agreeably to a

common provincialism of the west which

makes a skiff, a "skift," a cliff, a

"clift," etc. Clifton, a town north of Xenia, is just at the

commencement

of the same stone, and has borrowed its

name from it.12

He surveyed and drew with great skill a

diagrammatic section

of the valley and channel of the Ohio

River at Cincinnati from

Keys Hill in Ohio to Botany Hill in

Kentucky and records the

high water of the Ohio in I832, sixty-two feet

above its low water

level of I838.13

Of the importance of studying the dip of

geological forma-

tions he has this to say:

The strata are nearly horizontal, and

having a slight and irregular

undulation, the dip is with difficulty

ascertained, while one confines his

attention to the layers of the same

formation, for example, to the blue

limestone about Cincinnati. The inclinations resulting from undulation,

are seldom more than one foot in 45;

unless water be contiguous to mark

the level, the strata appear to the eye

to be quite horizontal. I have exam-

ined the inclination of the strata of

blue limestone about Cincinnati very

particularly with the leveling

instrument, and have sometimes found a uni-

form and consistent dip for half a mile;

in another locality the dip would

be in an opposite direction. The strata

in the bed of the Ohio at its lowest

stage in Sept. 1838, showed, by

comparison with the surface of the water,

that these local undulations were

extremely irregular, presenting inclin-

ations which vary in all possible

directions, in planes continued uniform

not generally more than one fourth of a

mile. A single stratum cannot in

general be identified far enough to

determine on the whole, whether it has,

independent of local undulations, an

absolute dip. However, when we

examine the several formations,

previously named, on a large scale, the

dip becomes very evident; and as one

formation sinks gradually below

the surface, and another superior one

presents itself, gives rise to those

important changes in the face and

productions of the country, which we

should hardly attribute to a slope so

moderate as one inch in a rod. By a

12 Ibid., 211.

13 Ibid., plate facing p. 211.

DR. JOHN LOCKE 36I

correspondence held between Dr. Owen,

the Geologist of Indiana and my-

self it has been ascertained that the

strata slope downward each way from

a line not far from that between Ohio

and Indiana pitching eastwardly

in Ohio and westwardly in Indiana in

such a manner that the cliff lime-

stone, which shows itself not many miles

east and west of Richmond, in

Indiana, descends and comes to the bed

of the Ohio river, at the east side

of Adams Co., in Ohio, and at the falls

of the Ohio, at Louisville.

It follows as a'consequence of this

arrangement that the out-cropping

edges of the strata present themselves

at the surface in the same order in

the two States, but proceeding in

opposite directions. For example, on

ascending the Ohio eastwardly, we meet with blue limestone, cliff

lime-

stone, slate, fine sandstone,

conglomerate, and coal. On descending the

Ohio westwardly, we meet with the same

things, in the same order, viz;

blue limestone, cliff limestone, slate,

&c.14

This quotation is given in full as a

splendid example of his

simple explanations and descriptions.

Here Locke is the student

in the field beckoning the stay-at-home

to venture out of doors

and try first hand an interpretation of

nature. This is also the

first description of the great limestone

arch, "the Cincinnati anti-

cline," as it came to be called in

the textbooks. Locke had given

up his

private school but he was still the educator addressing a

larger unseen audience as well as the

special group for whom his

remarks Were prepared.

He was also eager to present the value

of the study of geol-

ogy to the average citizen. On the map

he prepared of Adams

County he placed a section connecting

with Scioto County on the

east. He showed by this means that the

coals of Scioto County,

because of their dip toward the east and

their rise westward,

would be in the air I,160 feet above

the level of western Adams

County. At a glance anyone would know

that searching for coal

in Adams County would be useless. It is

believed this is the first

time a geological report carried so much

useful information in

such a simple, graphic way. Part of its

purpose was to demon-

strate the practical side of the survey

to the State legislative

assembly. However, it was not until

thirty years later under

John S. Newberry that the work was

resumed.

For some years, Dr. Locke had been

investigating terrestrial

14 Ibid., 206.

362

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

magnetism and the deviation from true

north noted in the hand of

the compass. While he had been in

England in 1837, Locke had

met some of the British investigators of

this problem. He was

able to add data for comparison with the

European published

results. He continued these

investigations for a number of years

and soon was a recognized leader in this

field. Possessed of an

inquiring mind and a passion for

designing or improving pieces

of equipment he produced a

"microscopic" compass and the

famous Locke level still used by civil

engineers. Both of these

were employed first by him in his own

survey work and then

offered for use to others.

Locke's connection with the Geological

Survey produced a

number of results of permanent value to

the State. It was

through his researches on the variation

of the magnetic needle

that the corrections in the separate

tracts of land in the survey of

the State of Ohio could be made. The

Virginia Military Lands

were parceled out to the owners of

claims without any regularity

or system. Locke helped to establish

order in this confusion by

his knowledge of the behavior of the

magnetic compass. He was

also able to locate iron deposits with a

special instrument he devel-

oped, and made a journey into

southeastern Ohio with other

members of the Survey for that

purpose. It was clear to the

members of the Geological Survey that

much of the school land

originally appropriated to the State had

been sold too quickly.

Without a geological appraisal the land

had been sold on the basis

of its potential agricultural value

only. The intelligent work of

men like Hildreth and Locke

unfortunately could not prevail in

the moulding of public opinion. Instead

of squandering most of

its land grant Ohio might have profited

as was later possible in

some of the other states, notably

Minnesota.

Locke was to have prepared detailed

surveys of both Butler

and Adams counties. He completed Adams

before the work was

abandoned. The survey of Adams County

was thus appraised

years later by Evans and Stivers:

There has never been but one geological

survey of Adams County,

and that was made by Prof. John Locke,

Assistant State Geologist, in

Dr. JOHN LOCKE

1838. There is a more recent report but

it does not at all cover the county.

Prof. Locke's report is so comprehensive

and withal so plain that anyone

by reading it may acquire much valuable

knowledge of the geological for-

mations of Adams County. It is however

necessary to note some changes

in classification and nomenclature in

accordance with present usage.15

On April 25, 1838, the disaster to the

river steamer Moselle

occurred. It was the worst accident of

its kind. The boilers had

exploded and the ship was burned. Since

a number of lives were

lost, the citizens of Cincinnati called

upon Dr. Locke to head a

committee of investigation. With his

usual thoroughness Locke

examined the possible causes of the

explosion. He centered

blame upon the ship builders and owners,

accusing them of

neglect in taking precautions to guard

the lives of crews and pas-

sengers. His report was widely read.

The discussion of his

report became an important factor in

establishing modern laws

to protect all who use steamboat

navigation.

Dr. Locke may have accepted the chair of

chemistry in the

Medical College of Ohio in 1835, though

his actual teaching seems

to have begun in 1837. Locke went abroad

between 1835 and

1837, for the purpose of purchasing new

apparatus for the

courses he intended to teach. His

connection with the college is

clearer after 1837, when the faculty was

reorganized and the

rivalry with the Cincinnati College was

declining.

He entered this period of teaching fully

aware of the storms

that had centered around the medical

faculties or one might also

say around the personality of Daniel

Drake. By the time Locke

joined the faculty of the Medical

College of Ohio, originally

founded by Drake, Drake had also founded

two other medical

faculties in Cincinnati, the Medical

Department of Miami Uni-

versity which lasted only a year and

from which Drake resigned

when it was included in the Ohio

College, and the Medical De-

partment of the Cincinnati College which

lasted from 1831 until

1839. Meanwhile Drake had taught at

Transylyania University

and at Jefferson College in

Philadelphia. Drake's brilliant, tur-

15 Nelson W. Evans and Emmons B.

Stivers, A History of Adams County, Ohio

. . . (West Union, Ohio, 1900), 10.

364 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL

QUARTERLY

bulent career, full of zeal and

ambitions to be the foremost medi-

cal teacher in Cincinnati, touched the

lives of all the prominent

medical, scientific, and public spirited

citizens of the town. Locke

should have been forewarned by the

frequent upsets in the medi-

cal faculties. This did not prove to be

the fact.

When the political intrigues which had

been fomented in the

Ohio College resulted in Locke's

dismissal in 1849-50, he was

stunned. Although he was reinstated and

served two more years

he no longer retained the enthusiasm for

the college that carried

him through the creative years he had

spent there. It was during

this period of about fourteen years that

Locke proved to be one

of the most remarkable figures in the

advancement of science in

his time. It is the aim of the following

paragraphs to show this

phase of Locke's life.

locke had carried with him to England

his observations of

the deviations of the magnetic compass

and thus was able to make

comparisons with the results obtained in

England. Col. Sabine,

of Woolwich, wrote to Locke, November 20, 1843:

"Permit me

to express hope for early publication of

your observations com-

paring Cincinnati, Toronto . . . on

terrestrial magnetism. If

there should prove a difficulty causing

a serious delay in the pub-

lication of your discoveries in the

United States, I cannot doubt

that either the Royal Society or the

British association would be

very proud to receive them and print

them."16 There was sound

practicality in this request. The

accuracy of surveying and navi-

gation were still too dependent upon the

erratic compass.

He invented a thermoscopic galvanometer

of great sensitivity

and demonstrated it to members of the

British Association. Prob-

ably at this time he met Professor

Wheatstone and Sir David

Brewster who were interested in his

experiments on optics which

they were likewise investigating. G. M.

Roe adds another factual

nugget:

In connection with this trip of Dr.

Locke to Europe may be men-

tioned a circumstance illustrative of

the uncertainties regarding municipal

action. The city of Cincinnati then used

an incorrect linear measure and

requested Dr. Locke to secure a standard.

He did so, having two made

16 Wright, Address on . . .

John Locke.40.

DR. JOHN LOCKE 365

and compared with the English standard

by William Simms, who made

the originals for the British

Government. One of these is 413 millionth

of an inch too long, the other 150

millionth of an inch too short. (Stand-

ards can not be made exact but

practically are so by having a known

error.) The city authorities failed to

reimburse Dr. Locke, and the meas-

ures . . . still remain in the hands of

his heirs. The measures are now of

great interest as the original English standards

are under seal, and can only

be opened by an act of Parliament.17

The acquaintances he made abroad

probably caused him to

think about the advantages of systematic

gatherings of scientists.

He began to attend meetings of the newly

organized Association

of American Geologists. He did not

attend the founding meeting

held at the Franklin Institute in April

1840. He

may have been

at that time with David Dale Owen on the

Indiana Geological

Survey, the report of which was

published that year. However,

W. W. Mather was present. Mather had

known Locke for his

work on the Ohio survey and may have

seen to it that Locke came

to the second meeting of the

Association, and thus tied him in

with the group that included Edward

Hitchcock, L. C. Beck,

Douglass Houghton, J. N. Nicollet, A. D.

Bache, and others.

When the second meeting was held

beginning April 5, 1841,

at the Academy of Natural Sciences in

Philadelphia, Locke was

appointed one of the committee to plan

the conduct of business.

From the previous year a committee to

discuss mineral manures

had been held over. Locke took part in

that discussion. W. W.

Mather asked to postpone his paper on

the "Drift" and Locke

read a paper on the "Geology of

Some Parts of the U. S. West

of the Allegany Mountains." In this

he offered some compari-

sons between the position and age of

European formations and

those he had studied in Ohio and

Indiana. This brought forth

some discussion and objections that were

quite natural since "cliff

limestone" and "blue

limestone," the currently employed terms,

were inadequate for comparative studies.

In a later session he described a new

species of trilobite

found at Cincinnati and named by him Isotelus

maximus. He

demonstrated by casts one specimen 93/4 inches long and frag-

17 Roc, Cincinnati, 360.

366 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL

QUARTERLY

ments of another 19 1/2 inches long. The

latter was the largest

trilobite known. In another paper he

discussed the "diluvial

scratches" that he had observed in

limestone. He called attention

to variations in the widths of the lines

or grooves, up to 1/2 inch

broad. Some were "1/8 inch deep,

scaled rough in the bottom as

if they had been ploughed by an iron

chisel properly set and car-

ried forward with an irresistible

force." From their exact

straightness and parallelism Locke drew

the inference, now accep-

ted as factual, that the lines had been

formed "by a body of im-

mense weight, moving with a momentum

scarcely affected by the

resistance offered by the cutting of the

grooves." He pointed out

that one set of grooves might be crossed

at an angle by another,

but that the parallelism of each set

remained.18

All of this data on striae must have set

the geologists think-

ing that perhaps diluvial was not the

way to describe these

scratches. Not many of the members present had been West.

There was Nicollet who had explored in

Missouri. He, Douglass

Houghton, Bela Hubbard, Mather, D. D.

Owen, Locke, H. D.

Rogers, also of the Medical College of

Ohio, and possibly some

others were opening up the explorations

of the continent. The

great continental ice theory was not to

be announced by Agassiz

for some years. The announcement of the

parallel nature of the

grooves must have made that second

session of the geologists

pretty much Locke's session.

At the second meeting, also held in

Philadelphia, the presi-

dent, Rev. Professor Edward Hitchcock,

referred to Locke's ob-

servations. There is not available a

first hand report of all that

Locke had included in his paper.

Hitchcock's address depends

in part on remarks that must have been

made by Locke. Hitch-

cock brings out the point that the

grooves even cross sharp ridges

without alteration of direction. It was difficult after that ses-

sion to attribute all the facts about

drift to a deluge. The stage

was being set during these meetings for

the modern discussions

of glacial geology that were to follow

in the next few years.

The place of leadership that Locke was

filling in the early

18 American Journal of Science, XLI

(1841), 158ff.

DR.

JOHN LOCKE

367

years of the Association of American

Geologists continued dur-

ing the following meetings. At Boston in

1842, Dr. Samuel

Morton did not arrive on time and Locke

was asked to take the

chair.

A constitution was adopted, the name being altered to

Association of American Geologists and

Naturalists. Its cos-

mopolitan aspect was attested by the

presence of Charles Lyell.

As in the previous year, Locke presented

papers on a diversity

of topics. His paper on "Ancient

Earthworks in Ohio" led to

the formation of a committee to examine

and report on the

western mounds. Locke, J. N. Nicollet, John H. Blake, Dr.

George Engelman, of course Hildreth,

Prof. Troost, and Dr. B.

B. Brown were named. A search for any

work by this com-

mittee fails to turn up a report,

however.

Locke also presented a paper on a new

instrument he had in-

vented, a reflecting level and

goniometer. He also described a

reflecting compass. His skill in

designing instruments suited to

his problems was second only to his

ingenuity in measuring and

observing facts others neglected. He was

a teacher because he

was ready to deal with the situation at

hand. He returned to

plant studies with a paper on a

prostrate forest under the Ohio

diluvium. Not presented at the meeting

was a published report

on observations made at Baltimore on the

dipping compass. To

test his observations his friends, Major

Graham, Nicollet, and

Bache, made similar use of his

instruments. He also published

a drawing of the large trilobite,

changing the name to Isotelus

megistor.19

Locke published a report on mineral

lands ordered to be

surveyed by Congress in 1839. This had

carried him to the lead

regions in Wisconsin and in Missouri.

His observations on the

subject of terrestrial magnetism carried

him to the north side of

Lake Superior.20 He also became interested in

transportation

problems at Sault Sainte Marie and was

asked by the War De-

partment to prepare a report on the

subject of a ship canal around

the rapids. He observed the granite

boulders along the lake shores

10 Ibid., XLII (1842),

235, 366.

20 U. S. Congress, 26

Cong., 1 sess., Executive Document No. 239, pp. 53,

116-39.

368 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL

AND HISTORICAL

QUARTERLY

with strong doubts as to their

usefulness in canal construction.

He stated that the want of materials for such a work need

not be any impediment as the limestone

of Drummond's Island

could be easily transported to the

Sault. He made an observation

contrary to a recommendation which had

been made to the War

Department with regard to the depth of

the canal. He doubted

whether vessels drawing more than six

feet of water could at all

times navigate St. Mary's River on

account of two bars, one of

rock at the Nebish Rapids and the other

of mud in Lake Huron.

Therefore it would hardly be necessary

to make the proposed

canal twelve feet deep as had been

suggested. Since Locke's time

more than a century of thoughtful

experimentation has attempted

to adjust the ore and grain cargoes, the

ships themselves, and the

docking facilities to the fundamental

geological problems his alert

eyes reported in his "hasty"

observations.

Then the Doctor, the almost forgotten

person in the several

John Lockes of whom the reader must by

this time be aware,

came forward to express himself.

There remains another consideration

which although not immediately

connected with wealth is still important

in furnishing that without which

wealth cannot be enjoyed. We venture to

urge the opening of Lake

Superior to steam navigation in order to

facilitate the access of thousands

of invalids to a region so picturesque,

so novel, and so invigorating as can

scarcely be equalled on the globe.

He mentioned the weariness of life

created by the "Mias-

mata of the Mississippi and the calm dry

heat of a summer in the

Southwest." He grew poetic in recommending an early escape

to the "pure water, the clear

atmosphere, the temperate summer

climate, the rugged fir clad rocks, the

piney glades carpeted

with reindeer licken and hung with the

dangling usnea."

It was probably nostalgia for his own

boyhood in Maine after

a succession of sultry summers in the

Middle West that brought

the enraptured praise that follows:

The canal being opened the citizens of

New York escaping from dust

and ennui and the resident of New

Orleans fleeing from the pestilence of

the summer months may be speedily wafted

to a meeting at Porter's Island,

at Isle Royale or at La Point and there

enjoy most of the Boreau wonders

DR. JOHN

LOCKE 369

of which they

have read in the voyages and travels of Ross, Franklin and

others and

there in the day admire the delusive mirage of the distant shores

and in the

night the portentous streamers of the aurora.

The fifth

annual meeting of the Association of American

Geologists and

Naturalists was held in 1844 at

Washington.

Dr. Locke served as

chairman, and Dr. Douglass

Hough-

ton as

treasurer. Dr. David

D. Owen who had been

elected

secretary was

not present. Locke read a paper on the connection

between

geology and magnetism, since he had always made both

kinds of

observations on his field trips. He noted that the great-

est magnetic

force was to be found in the Lake Superior region.

Douglass

Houghton read a paper on the importance of connecting

geological

surveys with linear surveys of public lands. The

Washington

meeting, close to the seat of Congress, contained in

the papers of

these two investigators a

symposium which, if

noticed, would

serve to call the attention of government officers to

the needs of

research and exploration of our natural resources.

John Locke,

the quiet teacher, was on the way to becoming a

national

figure.

In the paper

he read at the meeting he remarked:

In the year

1838, I began to examine the elements of terrestrial

magnetism,

including dip declination and intensity, both horizontal and

total, over

various parts of the United States. Every year since I have

made journeys

to extend this kind of research until now I have embraced

in a general

way the region from Cambridge, Mass. westward to the ex-

treme of Iowa

and. from the middle of Kentucky northward to the north

side of Lake

Superior. It was but natural that I should note the geology

of the

substratum at each station; and on reducing my observations and

putting them

into tabular form I examined the properties of each group

extending over

rocks of a similar kind and found so far as I had examined

some general

indications of which classes of rocks might be distinguished

although

concealed at considerable depths, the magnetical instruments in

this respect

answering the general purpose of a mineral or divining rod.22

This may have contained a little over-extension

of his

enthusiasm--yet

in the Lake Superior region compasses were al-

was showing

crazy local deflections. What excitement was con-

22 American

Association of Geolgists and Naturalists, Abstract of the Pro-

ceedings, V

(1844), passim.

370 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

cealed beneath the lofty cool words of

Locke's paper! He was

talking to the men who knew better

perhaps than any other group

in America the lack of knowledge of our

mineral resources. They

were the custodians at that moment of

enormous potential wealth

before which even Aladdin's lamp would

have blinked out.

Present at the meeting were Douglass

Houghton whose name

will always be associated with Michigan

and Minnesota, Wm. B.

Rogers, H. D. Rogers, and A. D. Bache of

the Coast Survey

Office. Capt. Wilkes of the United

States Exploring Expedition

invited the company to visit the

collections housed at the U. S.

Patent Office. An invitation was

extended likewise from the U.

S. Naval Observatory. To a number of the

men he met, Locke

was shortly to become indebted for

attention they gave to other of

his inventions.

He had strung a telegraph line--the

first one in Cincinnati

-- from the laboratory where he worked

in the Ohio Medical

College to his home. He had trained two

of his sons to help him

put together various instruments and

pieces of scientific appara-

tus he continually was designing.

Excerpts from Locke's report

seem the most appropriate for describing

his greatest invention.

This instrument was the

electro-chronograph. "My attention

was first drawn practically to the

subject of the combination of

clocks and electrical machinery for

producing useful results in

1844 and '45."23 He had obtained

a lathe and a set of tools from

the sculptor, Hiram Powers. Whenever he

needed a new piece

of apparatus to demonstrate a principle

he was able to design an

effective device. In consequence the

lectures he offered attracted

a distinguished audience. His assistants were Thomas K.

Beecher and his sons John Locke, Jr.,

and Joseph M. Locke.

He devised two types of electrotomes,

one with a conducting

pendulum swinging through a mercury cup,

the other a wheel

with pins or teeth to break the circuit

of tripping a tilt hammer.

This second form avoided friction. It

then occurred to him,

particularly after correspondence with

Sears C. Walker of the

Coast Survey Office, that an improvement

could be made on the

23 American

Journal of Science, n. s., VIII (1849), 233.

DR. JOHN

LOCKE 371

observations of time signals and star

signals made in the calcula-

tion of longitude. Heretofore these had been made by ordinary

clock readings and manual contact with

an electric circuit breaker

to send signals by telegraph to another

station. Due to an un-

certain loss of time the observations

were not at the level of ac-

curacy desired.

Locke then thought of using the Morse

register on which a

magnet marked traces on a paper

ribbon. By this means any

station connected with the observer

could have an event recorded

at the split second the circuit-breaker

key was moved. "Almost

every astronomical observer has

intiutively felt a desire to have

some kind of a chronograph with which to

subdivide a second

and record fractionally the punctum of observation."

Sears C. Walker wrote:

Dr. John Locke of Cincinnati, has

invented a very cheap and simple

instrument which can be attached to the

same pivot along with the second

hand of any clock, and which will, when

put in connection with the tele-

graphic circuit, make the clock beat at

the same instant all along the line.

The hours, minutes and seconds, may be

registered on the fillet of

paper, and by striking on the

telegraphic key at the instant of any occur-

rence, the date of it is recorded on

the same paper to the hundredth of a

second. This invention will be useful for many practical

purposes. It

makes the current of time visible to the

eye in a permanent record. It does

not change the rate of going of the

most delicate clock. It will doubtless

be applied hereafter to many purposes

for the advancement of science; such

as the determination of geographical

longitude, in connection with transit

instruments, measurement of the velocity

of sound; perhaps, if the circuit

be long enough, of lightning itself.24

Lieutenant M. F. Maury, Superintendent

of the National

Observatory, wrote in a letter to Hon.

John Y. Mason, Secretary

of the Navy. this graphic account of the

use of the electro-

chronograph:

Thus the astronomer in Boston observes

the transit of a star as it

flits through the field of his

instrument, and crosses the meridian of that

place. Instead of looking at a clock

before him, and noting the time in the

usual way, he touches a key, and the

clock here subdivides his seconds

to the minutest fraction, and records

the time with unerring accuracy.

24 Ibid., 237-8.

372

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

The astronomer in Washington waits for

the same star to cross his

meridian, and, as it does [the key for

circuit breaking on] Dr. Locke's

magnetic clock is again touched; it

divides the seconds and records the

time for him with equal precision. The

difference between these two times

is the longitude of Boston from the

meridan of Washington ....

And thus this problem, which has vexed

astronomers and navigators,

and perplexed the world for ages, is

reduced at once, by American ingenu-

ity, to a form and method the most

simple and accurate. While the pro-

cess is so much simplified, the results

are greatly refined. In one night

the longitude may be determined with far

more accuracy by means of a

magnetic telegraph and clock, than it

can by years of observation accord-

ing to any other method that has ever

been tried.25

The Coast Survey had made an arrangement

with the Tele-

graph Company in Cincinnati to have a

line extend through Dr.

Locke's house. On November 17, 1848,

this experiment of ob-

serving longitude with Locke's

instruments was tried for the first

time and it was successful. The model

instruments had been com-

pleted by the fourth of November. Dr. A.

D. Bache communi-

cated a full report to Congress in

December of that year and to

Dr. Locke a special Congressional award

of ten thousand dollars

was the official recognition that the

representation made on the

part of his colleagues in this advance

into the realm of science

was approved.

This invention would be a happy,

elevated note on which to

conclude the account of the work of Dr.

John Locke. One must

not forget that his work in the fields

of physics and astronomy

sprung from the lectures on chemistry he

conducted in the Ohio

Medical College. That was always an institution given to

per-

sonality conflicts among the faculty

members. Locke had be-

gun his work there during one of the

frequent reorganizations of

the faculty personnel. He was to leave it in the same manner.

The blow of being asked to resign was

too much for him to bear,

even though he knew it was a political

quarrel that forced his dis-

missal. He was shortly afterward

reinstated, but the damage to

his spirit of loyalty had been too great

to rekindle hi's old enthus-

iasm for the school. He remained two

years after reinstatement

25 Ibid., 241.

DR. JOHN LOCKE 373

but moved to Lebanon, Ohio, and there

managed a preparatory

school. This was too weak a challenge to

his broad grasp of the

world of science. But he had no further

taste for original in-

vestigation if he and his labors were to

be subject to political

vagaries.

At the meeting held in 1851 in Cincinnati of the American

Association for the Advancement of

Science, a lineal descendant of

the old Association of Geologists and

Naturalists. over which he

had presided, Locke was not present. His

son, L. T. Locke of

Nashua, New Hampshire, is listed among

members of the asso-

ciation, but his name is dramatically

lacking. His friend and

associate who had done much to praise

the electro-chronograph, A.

D. Bache, served as president. O.D.

Mitchell, the Director of

Astronomical Observatory of Cincinnati,

delivered an address on

the longitude of Cincinnati, and Sears

Walker gave a report, but

the only mention of the name of Locke is

an acknowledgement of

a chronometer loaned by him.26 To

Locke it was easier to sub-

divide seconds than it was to regain

emotional composure and

balance.

He made one strong effort to return to

his first interest in

the field of science--the plant world.

He delivered at Lebanon

an address, "On the means of

renovating worn out farms." After

discussing declining fertility in soils

and the methods of com-

batting this, he recommends the

establishment of libraries of

agricultural schools and an agricultural

survey. It is interesting

to note that a paper by N. S. Townshend

is contained in this same

volume.27 The brilliant genius of John

Locke was dimmed.

He was not looking backward but was

passing something of his

spirit to others who would look to the

natural resources of Ohio

and their future development.

26 American Association for the Advancement

of Science, Proceedings, V

(1851), passim.

27 Ohio State Board of Agriculture, Ninth

Annual Report . . . 1854

(Columbus, 1855), 212-2.

DR. JOHN LOCKE, EARLY OHIO SCIENTIST

(1792-1856)

by ADOLPH E. WALLER

Associate Professor

and Curator of the Botanic Garden.

Ohio State University

The nineteenth century in the United

States suddenly swung

into its expanding programs of research

and education. No one

was prepared for the impact of the

increasing realization of the

power over nature which man now

possessed. The illusion of

the perfectibility of all men through

knowledge stretched un-

dimmed. The inherent weaknesses of man

and the snail's pace

of education were not yet perceived.

Gigantic discovery was so

close at hand that no one troubled to

consider disappointments as

more than temporary obstacles. A little

proficiency in mathe-

matics, languages, and the law marked

the educated man. Scien-

tific training was unknown. Science

laboratories were just start-

ing and the skills and techniques they

were to impart were born

on the spot.

The thesis that the medical colleges of

the time were the

sources of our trained scholars in the

natural sciences has been

stated in previous papers in this

series. Three months at "Cam-

bridge College" prepared Dr. Samuel

P. Hildreth for his degree

in medicine, after an apprenticeship

with practicing physicians.

Many others were likewise briefly

exposed to formalized study.

Dr. John Locke was more fortunate. His

formal training lasted

about three years.

Philadelphia and Cincinnati were early

in asserting leader-

ship in the quality of medical training

offered. Many of the

students trained in medicine were not as

interested in its practice

as in following the leads offered by

their training in sciences. Our

outstanding botanists and geologists of

the 1830's were thus

educated. Dr. Locke's story follows a

similar pattern with the

difference that he added physics to his

earlier inclinations toward

botany and geology. Perhaps it was from

his keen observation of

346

(614) 297-2300