Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

JOSEPH B. FORAKER AND THE STANDARD OIL

CHARGES1

by EARL R. BECK

Instructor in History, Ohio State

University

In 1908 Joseph Benson Foraker, then

serving his second

term in the United States Senate, was

one of the outstanding

figures in politics in the nation.

Foraker had won national notice

for his aggressive, uncompromising fight

against the Hepburn

Rate Bill of 1906 and for his strident

attacks upon the executive

action of President Theodore. Roosevelt

which led to the discharge

without honor of a battalion of Negro

soldiers involved in a shoot-

ing affray at Brownsville, Texas. The

latter issue aroused the

personal ire of the President and he and

Foraker had met in a

heated discussion at the Gridiron Dinner

of 1907. To these diffi-

culties between the two men was shortly

to be added a further

cause for rancor, the opposition of

Roosevelt to Foraker's presi-

dential aspirations.

During Foraker's long career in politics

his pathway to a

presidential nomination by the

Republican Party was constantly

blocked by superior claims for

recognition upon the part of some

other Ohio statesman. Thus in 1884 and

1888 it was John Sher-

man who demanded the solid vote of the

Ohio delegation at the

Republican National Convention as a

guerdon for thirty years of

faithful service. In 1892, 1896, and

1900 William McKinley, Jr.,

came to the fore, receiving Ohio's vote

in 1892 in an effort to avert

the renomination of Benjamin Harrison

and in the two succeeding

campaigns as the result of a political

compromise with the Foraker

forces. In 1903 Mark Hanna was

considered the great man of

politics in the Buckeye State and

Foraker averted his possible

nomination for the 1904 campaign only

by springing to the staunch

1 This article is based largely upon

the author's unpublished doctoral dissertation,

written at the Ohio State University,

1942.

154

JOSEPH B.

FORAKER 155

defense of Theodore

Roosevelt. Now, in 1908, Sherman, Mc-

Kinley, and Hanna

were gone. Foraker

remained as the last of

the "old

guard." Twenty-five years of

faithful Republicanism

were behind him. It

seemed as if at last he might receive the

coveted honor of

recognition as "Ohio's favorite son." But once

again a Buckeye

competitor appeared to frustrate his

hopes and

to participate in his

ejection from public life in complete disgrace.

This new rival was

the favorite of the White House, William

Howard Taft.

Nevertheless,

Foraker's failure to obtain the presidential

nomination in 1908

is not to be laid entirely at the door of the

burly Secretary of

War. Foraker had left behind him a long

series of factional

conflicts with his fellow Republicans of the

Buckeye State. And in

the vital period preceding this last effort

to attain the highest

political distinction of the country, Foraker

added to his list of

opponents the names of Myron T. Herrick,

whose renomination to

the governorship he opposed in 1904;2

George B. Cox, who

had been won to Herrick by the Governor's

favorable attitude to

Cox's supporters, the liquor dealers of south-

ern Ohio;3 Theodore E. Burton, who coveted Foraker's seat in the

Senate;4 and Harry M.

Daugherty, who was vying with Foraker

for political

influence in the State.5 In addition the Scripps-

McRae newspapers and

the newspapers of R. F. Wolfe of Colum-

bus had developed a

settled antagonism to the Senator.6 And,

although Foraker was

to forge an alliance with the political ma-

chine of Junior

Senator Charles Dick, the strength of the opposi-

tion forces

eventually proved decisive.7

2 Discussion of the points at issue between Foraker

and Herrick are revealed in

letters of Foraker

to J. P. Bradbury of Pomeroy, Ohio,

February 24, 1904, to Thomas H.

Tracey of Toledo,

March 6, 1904, to W. S.

Cappeller of Mansfield, November 9, 1904.

Manuscript copies of all

letters are in the library of the Historical and Philosophical

Society, Cincinnati,

unless otherwise stated.

3 W. S.

Cappeller to Foraker, January 19, 1905; C. H. Grosvenor to Foraker,

May 21, 1905; Foraker to

John A. Sleicher, President of the Judge Company, August 29,

1905.

4 Foraker to C. H.

Grosvenor, September 6, 1906.

5 Ibid.

6 Foraker to

Clarence Brown of Toledo, January 5, 1907. Foraker to C. H.

Grosvenor,

September 6, 1906, to C. H. Galbreath, October 31, 1906. See also Foraker's

Notes of a Busy Life (Cincinnati, 1916), II, 380.

7 New York

Times, February 4, 1907.

This clipping and many of the others

cited may be found

conveniently by reference to the Scrapbook Collection which Mrs.

Julia B. Foraker, the wife

of the Senator, kept and which is owned by the Ohio State

Archaeological and

Historical Society, Columbus. There are 21 large volumes of clip-

pings from a wide variety

of newspapers and periodicals, the clippings reflecting adverse

as well as

favorable comment.

JOSEPH B. FORAKER 157

Foraker lost his best opportunity to

obtain Ohio's endorse-

ment of his candidacy when he failed to

seek that action at the

State Republican Convention in Dayton in

1906. Dick's political

machine controlled this assembly of the

party and Foraker could

have had the endorsement if he had

requested it.8. Foraker, how-

ever, chose to avoid the weakness of a

campaign launched so long

before the meeting of the National

Convention. But the follow-

ing year saw the entry of Taft into open

competition for the pres-

idential nomination, Taft's relatives

and President Roosevelt join-

ing to break down Taft's reluctance to

launch a candidacy for

the presidential office. Foraker's

announcement of his candidacy

followed a few days on the heels of

Taft's action and the stakes

were set by both candidates as "all

or nothing," with the Senator-

ship consituting a source of contention

along with the presidential

nomination.9

On his side Taft had many sources of

strength. His can-

didacy derived greatest prestige from

the full approval accorded it

by President Roosevelt. In January 1907

Representative Nich-

olas Longworth of Cincinnati declared

that the President would

not seek a third term, but that the

executive was determined that

his successor should not be a

"reactionary"--he must be a man

who could carry on the Roosevelt

policies.10 Taft's shrewd

brother, Charles, editor of the Cincinnati

Times-Star, lost no time

in taking advantage of the opening made

by Longworth. "This is

a direct contest," proclaimed the

editor, "between the friends of

the administration of President

Roosevelt and his opponents."11

Taft's effort to align himself with the

President were aided by

warnings from the White House of a

"rich man's conspiracy" to

prevent the continuance of Rooseveltism

with Foraker as a prom-

inent suspect.12 The

principal exhibit in regard to Foraker's anti-

8 See Foraker's interview in Cincinnati

Enquirer, August 27, 1906, republished in

Speeches of J. B. Foraker (n. t. p., Cincinnati?, 1917?), V, 11-24; Cincinnati

Enquirer,

September 12, 1906; Cincinnati

Commercial Tribune, September 13, 1906; Telegram of

J. B. Foraker, Jr., to Mrs. Foraker,

September 12, 1906; in Mrs. Foraker's Scrapbooks,

VI; Notes, II, 376-377.

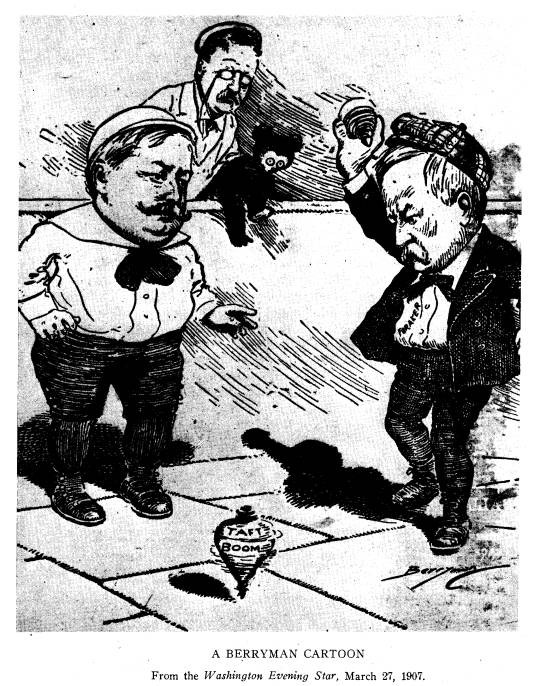

9 Cincinnati

Commercial Tribune, March 26, 1907; Washington

Evening Star,

March 27, 1907; New York Herald, March

28, 1907.

10 Cincinnati Enquirer, January

26, 1907.

11 Cincinnati

Times-Star, March 30, 1907.

12 Anon., "A Review of the

World--Foraker's Fight Against Taft," in Current

Literature, XLII (May 1907), 469-471.

158

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

Rooseveltism was, of course, his fight

on the Hepburn Rate Bill,

to which measure Taft had shown

consistent favor.

Foraker's weapons against Taft were not

inconsiderable.

Roosevelt's advocacy of Taft's

nomination was denounced as

"Presidential Interference in Our

Ohio Politics" and portrayed

in one instance as designed to destroy

both Foraker and Taft so

that Roosevelt might launch a third term

candidacy.13 Foraker

continued to defend his position on the

Hepburn Rate Bill, assert-

ing that this act had weakened the

effect of the Elkins Law by

imposing imprisonment as a penalty for

violations, a punishment

which courts were reluctant to

prescribe. And the insertion of

the word "knowingly" with

respect to violations of the Hepburn

Law, stated the Senator, was an

emendation which would have

saved the Standard Oil Company the heavy

fine it had to pay

under the original Elkins Law.14 To this

justification of his own

action with respect to the Hepburn Bill

Foraker added a strong

assault upon Taft's tariff revision

views, knowing that protec-

tionist sentiment was still very strong

in Ohio in spite of the advent

of Rooseveltism.15 Moreover, Foraker had

available a reputation

as a fighter in politics, as a man of

courage. Under the caption,

"The Greatest Bulldog in American

Politics," one writer indi-

cated that during his entire career

Foraker "has always been 'the

man on horseback,' always militant,

always with red spurs, always

erect and martial and splashed with

mud."16 And last but not least

Foraker had at his disposal oratorical

powers of the highest order.

Had there been a regular state party

convention in 1907, Foraker

might well have swept the meeting as he

had the year before and

might have gone to the National

Convention with a large number

of Ohio votes. But it was at this time

that Ohio dispensed with

"off-year" elections for state

officials and hence there was no

state-wide convention in 1907. The only

state-wide party organ-

ization in existence during that year

was the State Central Com-

mittee, whose action was to spell defeat

to Foraker's hopes.

13 J. H. Woodward, "The

President in Ohio Politics," in Saxby's

Magazine,

XVIII (1907), 49-51; Marion

Daily Star, May 18, 1907, editorial

(W. G. Harding).

14 Cincinnati Commercial Tribune,

August 21, 1907.

15 American Economist, July 26, 1907;

Cincinnati Enquirer, August 2, 1907.

16 Anon.,

"The Greatest Bulldog in American Politics," in Current

Literature,

XLII (May 1907), 506-508; cf.

Samuel G. Blythe, "Taft and Foraker," in Saturday

Evening Post, May 11, 1907;

Anon., "Who's Who and Why," in

Saturday Evening Post,

February 16, 1907.

JOSEPH B. FORAKER 159

This State Central Committee had been

chosen by the Dayton

Convention of 1906 and consisted of 21 members, one

from each

congressional district. Its duties were

simply those of dealing with

routine party business until the call

for the next state convention.

There was, accordingly, believed

Foraker, no authority vested in

this committee to declare the party will

on presidential candidacies.

When the Senator learned, in July 1907,

that the committee pro-

posed to endorse Taft as Ohio's

candidate for the presidency, he

made public protest, but in vain. The

committee met and Taft

was endorsed. Strangely enough, however,

this position favor-

able to Taft was taken at the specific

behest of George B. Cox of

Cincinnati, who had been vigorously

denounced by Taft in 1905

as a political boss.17 The

probable explanation of Cox's favor for

Taft at this time lies in the boss's

recognition of editorial support

by the candidate's brother.18 In

any event the loss of Cox's sup-

port was a bitter and unexpected blow to

Foraker, for the Sen-

ator well knew the power of the

political combine which the munic-

ipal boss had constructed. Later,

Foraker was to declare that Taft

owed his nomination to Cox more than to

any other single individ-

ual, because by his efforts Taft was

given almost a solid Ohio

delegation at the Republican National

Convention.19

In spite of the endorsement of Taft by

the State Central

Committee Foraker remained in the race

for presidential nomina-

tion. He was endorsed in turn by the

Ohio Republican League

with Warren G. Harding as the

outstanding figure at the meeting.20

But the Foraker candidacy had been from

the beginning a rather

hopeless one, and the action of the

State Central Committee as-

sured his rejection in Ohio. Even

Harding deserted the Foraker

standard early in 1908 and recommended

the nomination, of

Taft.21 At the Republican National

Convention Foraker received

only four votes from Ohio and a total of

sixteen from the entire

country. There were some efforts upon

the part of Charles W.

Fairbanks, Philander C. Knox, Joseph G.

Cannon, and Foraker to

17 Foraker to C. B. McCoy, July

29, 1907, in Speeches, V, 504-510; Notes, II,

383-384.

18 Blythe, "Taft and Foraker," loc. cit.

19 Notes, II, 384.

20 Cincinnati Enquirer, November 21 and 30, 1907; proceedings in Speeches,

V,

584-596.

21 Notes, II, 393.

160 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND

HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

unite to head off Taft's nomination, but

this was in vain.22 Taft

received 702 votes from a total

of 979 and was thereafter nom-

inated unanimously.

During the summer of 1908, following

Taft's nomination for

the presidency, Foraker continued to be

openly unenthusiastic

about his candidacy. The Republican

nominee deemed the Sena-

tor's lukewarmness a serious hindrance

to the progress of his cam-

paign. Finally in July Taft appealed to

Nelson W. Aldrich of

Rhode Island, conservative captain of

the party, to bring influence

upon Foraker to be more discreet in

opposing the Roosevelt poli-

cies, which Taft considered "our

whole stock of trade in this cam-

paign." Heeding the candidate's

plea, Aldrich wrote to Foraker

and entreated him to take an important

part in the campaign, leav-

ing the settlement of differences

between the President and himself

to the verdict of history.23 Subsequent

to this letter of Aldrich,

Foraker made several speeches in behalf

of Taft, appearing with

him in "love-feast" at Toledo

on September 2 and concluding

arrangements shortly thereafter to act

as chairman of a Taft meet-

ing at Music Hall in Cincinnati on

September 22 at which Taft

was to deliver the principal address.24

Although Taft assured

Roosevelt that no bargain had been made

with Foraker, he in-

formed another associate that Foraker's

aid might be valuable

with the Negro vote and the Grand Army

of the Republic ele-

ment.25 Undoubtedly Taft would have

allowed Foraker to fill the

engagement at Cincinnati if the Standard

Oil disclosures had not

intervened.

At this point, however, events took a

most unexpected turn.

Every assault upon Foraker before this

time had been directed

against his political convictions rather

than against his personal

integrity. On September 17, 1908, a frontal attack upon the

Senator's character as a public servant

was launched by one of the

most enigmatic personalities in American

history, William Ran-

22 ames E.

Watson, As I Knew Them (Indianapolis, c1936), 125.

23 Taft to Aldrich, July 12, 1908; Aldrich to Foraker,

August 21, 1908, cited by

Nathaniel Wright Stephenson, Nelson W.

Aldrich. A Leader in American Politics

(New York, 1930), 336.

24 Notes, II, 395; Anon., "The Love-Feast in Ohio," in Literary

Digest, XXXVII

(September 19, 1908), 376-377.

25 Taft to Roosevelt, September 4,

1908, to W. R. Nelson, September 4, 1908,

cited by Henry F. Pringle, The Life and Times of William Howard

Taft. A Biography

(New York, c1939), 1, 371.

JOSEPH B. FORAKER 161

dolph Hearst. Hearst's career had marked

the popularization of

yellow journalism to a degree which

shocked respectable citizens.

After defeating Pulitzer in the campaign

for sensational news

stories which preceded the

Spanish-American War, Hearst was

the recognized champion of the art of

exploiting public and private

scandal to boost newspaper circulation.

When mere editorializing

upon political affairs palled upon him,

Hearst entered the radical

wing of the Democratic Party and was

elected to Congress in

1902. While in Congress, Hearst was

candidate for Mayor of

New York City in 1905 and for Governor

of New York the

following year. By 1908 the New York

editor had repudiated

the regular political parties and placed

himself among the leader-

ship of a third party, the

"Independence League," dedicated to

political reform. Accordingly, it was

possible for Hearst, while

speaking for Thomas L. Higsen, the

presidential candidate of the

Independence League, to attack both

Democrats and Republicans

in his expose of the influence of the

Standard Oil upon politics

and to declare that both of the old

parties were hopelessly cor-

rupt and inextricably enmeshed in the

toils of self-aggrandizing

corporations.26 Hearst's

denunciations of the leaders of the old

parties rendered him worthy of the

appellative, "the last of the

Muckrakers," but in the Standard

Oil revelations as in other of

his efforts in the realm of exposure,

Hearst differed from the

reputable muckrakers in his substitution

of imagination and mere

assertion for documentary evidence and

tireless research.27

Hearst's first presentation of charges

against Foraker was in

full consonance with the style of

journalism which he had devel-

oped. To his Columbus auditors the New

York editor proclaimed

with dramatic effect his intention to

disclose astounding infor-

mation:

I am not here to amuse you and entertain

you with oratory, but I am

here to present to you as patriotic

American citizens some facts that should

startle and alarm you and arouse you to

a fitting sense of the genuine danger

that threatens our republic.

26 For a general account of Hearst's career see John K.

Winkler, W. R. Hearst,

An American Phenomenon (New York, 1928); Ferdinand Lundberg, Imperial Hearst, A

Social Biography (New York, c1936); Oliver Carlson and Ernest Bates, Hearst, Lord

of San Simeon (New York, 1936).

27 Carlson and Bates, op. cit., 164.

162

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

I am not here either with empty

assertions but with legal evidence

and documentary proof. I ask you to

rally to your country's needs, to

rescue your country from the greatest

danger that can threaten a republic-

the danger that is within the gates--the

corrupting power of unscrupulous

and criminal wealth.

I am now going to read copies of letters

written by Mr. John Arch-

bold, chief agent of the Standard Oil,

an intimate personal representative of

Mr. Rockefeller and Mr. Rogers. These

letters have been given me by a

gentleman who has intimate association

with this giant of corruption, the

Standard Oil, but whose name I may not

divulge lest he be subjected to

the persecution of this monopoly.28

Hearst then proceeded to read six

letters addressed to Foraker

and signed "John D. Archbold."

Two of these epistles, dated

March 27 and April 17, 1900, referred to

monetary payments to

Foraker of $15,000 and $14,500

respectively. Two others, writ-

ten during February and March 1900,

pointed out objectionable

legislation against which Archbold

requested Foraker's influence,

the bills in question being later

identified as proposals advanced in

the Ohio General Assembly. The remaining

two items of cor-

respondence dealt with individuals. On

December 19, 1902, the

corporation vice-president had solicited

Foraker's support for the

candidacy of Judge Jacob Burket for

reelection to the Ohio Su-

preme Court and on March 20, 1903, had

requested the Senator's

opposition to the candidacy of Smith

Bennett for the Ohio attor-

ney generalship.29

The effect of these letters was dynamic.

The Columbus

audience did not applaud or cheer, but

remained quiet as if

stunned. The newspapers, however,

reacted more vigorously.

The sensation was emblazoned in the

headlines of the papers ap-

pearing the following morning, and

Hearst found a small army

of reporters awaiting him when he

arrived for his next evening's

engagement at St. Louis.30

The close time sequence between the

letters read by Hearst

which referred to monetary payments and

those which directed

attention to objectionable legislation

naturally created the impres-

28 Ibid., 166-167.

29 Ibid., 167.

30 Winkler, op. cit., 232.

JOSEPH B. FORAKER 163

sion that Foraker was paid by the

Standard Oil to watch over its

interests in politics. This impression

Foraker sought immediately

to offset by a statement hastily

prepared and given out to the

newspapers on the afternoon of the same

day on which had ap-

peared the reports of Hearst's Columbus

speech. Although he did

not recall the specific letters which

the New York editor had

read, stated Foraker, it was quite

probable that they were bona

fide, for he had been employed at the

time when they were written

in a legal capacity for the Standard Oil

corporation. It was not

at that time, he asserted, considered

discreditable to be an attorney

for such a corporation. He had not

sought to conceal his em-

ployment, for he was proud of the honor

accorded by a retainer

in such an important capacity. This

employment, continued For-

aker, had been concluded before the

expiration of his first term

in the Senate and had not been renewed

at any subsequent time.

Nor had he, the Senator stated, had any

employment which had

reference to matters pending in Congress

or in which the federal

government had any interest.31

Speaking at St. Louis the following

night, Hearst made fur-

ther revelations of Foraker's connection

with the Standard Oil

Company. The editor admitted that

Foraker's statement was "a

good answer" to the letters which

he had read previously, but

asserted that the Senator would have

denied the whole affair if

he had known the full extent of the

letters in Hearst's possession.

The orator for the Independence League

then read one letter from

Archbold to Foraker dated January 27, 1902, which

mentioned a

payment to the latter of $50,000 and

another, dated February 25

of the same year, which protested

against a "vicious" anti-trust

bill introduced in the Senate. The

juxtaposition of the two implied

a causal connection between the receipt

of the money and the

action against, undesirable

legislation, an implication reinforced

by Hearst's statement that Foraker's

defense failed to convince

him that the correspondence had nothing

to do with legislation

before the Senate.32

Again Foraker drafted a complete answer

to Hearst's allega-

31 Notes, II,

329.

32 Ibid., 329-330;

Cincinnati Enquirer, September 19, 1908.

164 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL

QUARTERLY

tions and released it in time for

publication in the afternoon papers.

The payment of $50,000 mentioned in

Archbold's letter had not,

he asserted, been a payment to his

personal credit at all. On the

contrary, it had been a loan advanced

for the purchase of the

Ohio State Journal as a party organ. The proposed purchase of

the Journal had not been

consummated, and Foraker had returned

the entire sum to Archbold. As for the

message concerning legis-

lation before the Senate, this appeal

had not been connected with

any pecuniary payment of the corporation

and had only the status

of a letter written by any private

citizen. Neither the Standard

Oil nor any other corporation,

asseverated Foraker, had ever paid

him a cent on account of the attitude

which it wished him to take

in regard to any proposed legislation.33

Up to this point Foraker had furnished a

legitimate reason

for each payment of money made to him by

Standard Oil. Al-

though his remarks with regard to the

legislation referred to in

Archbold's letters were not completely

convincing, his defense

as a whole was sufficiently well

constructed and seemingly frank

and straightforward enough to have

caused impartial observers to

withhold judgment until Hearst had

completed his exposures and

Foraker had finished his replies. But

many of Foraker's contem-

poraries were unwilling to wait for

explanations or to examine

them carefully when they did appear.

Outstanding among those

who reached a conclusion by the time

Hearst made his second

speech was Theodore Roosevelt.

Roosevelt's verdict of

"guilty" was reached by the day fol-

lowing the appearance of reports of

Hearst's Columbus speech,

and the President lost no time in

confiding his judgment to his

friends. To the scholarly Massachusetts

Senator, Henry Cabot

Lodge, the President wrote, "Those

revelations about Foraker are

very ugly. They of course show, what

everyone on the inside

knew, that Foraker was not really

influenced in the least by any

feeling for the Negro, but that he acted

as the agent for the cor-

33 Notes, II, 331-332; Subcommittee of the

Committee on Privileges and Elections,

United States Senate, Sixty-Second

Congress, Campaign Contributions.

Testimony

. . . , 1312-1313 (Hereafter this document will be referred

to as Clapp Committee

Investigations in accordance with name

of the chairman of the committee, Moses E.

Clapp of Minnesota.)

JOSEPH B. FORAKER 165

porations."34 To Taft he declared

that the Hearst letters re-

vealed "the purchase of the United

States Senator to do the will

of the Standard Oil Company" and

averred that if he were run-

ning for President, he would decline to

appear upon the platform

with Foraker. "I would have it

understood in detail," Roosevelt

informed his favorite,

what is the exact fact, namely, that

Foraker's separation from you and

from me has been due not in the least to

a difference of opinion on the

Negro question, which was merely a

pretense, but to the fact that he was

the attorney of the corporations, their

hired representative in public life,

and that therefore he naturally and

inevitably opposed us in every way.

. . . I think it is essential, if the

bad effect upon the canvass of these dis-

closures is to be obviated, that we

should show unmistakably how com-

pletely loose from us Mr. Foraker is. If

this is not shown affirmatively

there is danger that the people will not

see it and will simply think that

all Republicans are tarred with the same

brush.35

In this hasty judgment by Roosevelt two

motives were dominant.

The President was a shrewd politician

and knew well how to

gauge the temper of public feeling. He

realized that the public

formed its convictions upon headlines,

that it would never pause

to read explanations or extenuations

once Foraker had admitted

the authenticity of the Hearst letters.

It was therefore essential

to free the party of the incubus of an

unpopular and discredited

leader. But it is impossible to avoid

the conviction that Roose-

velt pounced upon the Hearst charges as

a complete vindication

of his own actions in the Brownsville

affair. The President's

statement that Foraker's opposition in

the Brownsville matter had

been due to corporate affiliations did

not change one whit the

weight of the arguments advanced by the

Senator against Roose-

velt's action. It would, however, create

in the popular mind the

impression that Foraker's criticism had

been a matter trumped up

to discredit the President. Roosevelt

was anxious, therefore, to

make the most of the Hearst disclosures.

Taft's position was not so simple as

that of his political

mentor. Only two weeks before, he had

engaged in an exchange

34 Roosevelt to Lodge, September

19, 1908; Theodore Roosevelt and Henry Cabot

Lodge, Selections from the

Correspondence of . . . , 1884-1918 (New York, 1925),

II, 316.

35 Roosevelt to Taft, September 19, 1908, cited by Mark Sullivan Our

Times.

The United States, 1900-1925 (New York, 1926-35), II, 224.

166

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

of reconciliation greetings with Foraker

and had announced that

he would make use of Foraker's

assistance in the campaign.

Moreover, a long debt of gratitude to

Foraker was charged up

against Taft. Foraker had appointed him

to his first public office

as judge on the Superior Court of

Cincinnati, had recommended

him to the Supreme Court in 1889, had

heartily approved McKin-

ley's proposal to make him Governor of

the Philippines, and had

defended him against senatorial attacks

upon his management of

affairs in the Islands. But that

gratitude obligated Taft to condone

corruption in public service no one

would contend. And on the

same day on which Roosevelt suggested

that Taft refuse to appear

with Foraker, the nominee replied that

he, too, was convinced that

the Senator had deviated from the course

of rectitude in office.36

Nevertheless it might be remarked that

Taft was very quick

to accept the statments of Hearst, whom

he had characterized in

1906

with such words as "dealer in filth," "hideous product of yel-

low journalism," and "immoral

monstrosity."37 Foraker believed

afterwards that Taft must have become

convinced of his innocence

or he could not have accorded his former

antagonist the respect

which he displayed towards him in later

years.38 In 1908, how-

ever, Taft was a presidential candidate

and his whole stock in

trade was opposition to the

corporations. He did not dare

take chances with public opinion. Accordingly on Septem-

ber 20 the Republican nominee

made it known to Murray Crane,

Foraker's manager during the contest for

the presidential nom-

ination; that it would be embarrassing

for him to appear on the

same platform with Foraker. The latter

immediately withdrew

from his scheduled engagement at Music

Hall in Cincinnati two

days later and cancelled other speaking

arrangements. If the

meeting at Cincinnati had been carried

out as scheduled, Foraker

was to have been allowed to speak last

in order to present a de-

fense of his career against the Hearst

charges.39

Taft's gentle method of eliminating

Foraker from the Cin-

cinnati engagement was not at all

satisfactory to Roosevelt. "He

36

Pringle, op. cit., I, 372.

37 Taft to Elihu Root,

November 10, 1906, in ibid., 319.

38 Notes, II, 348.

39 Cincinnati Enquirer, September 20, 1908.

JOSEPH B. FORAKER 167

ought to throw Foraker over with a

bump," declared the President.

"I have decided to put a little vim

into the campaign by making

a publication of my own."40 The

fruit of this decision was an

interview released from Oyster Bay, New

York, September 21.

Commenting on the Hearst letters,

Roosevelt declared:

Senator Foraker has been a leader among

those members of Con-

gress of both parties who have

resolutely opposed the great policies of

international [internal?] reform for

which the Administration has made

itself responsible. His attitude has

been that of certain other public men,

notably . . . Governor Haskell of

Oklahoma.

There is a striking difference in one

respect, however, in the present

positions of Governor Haskell and

Senator Foraker. Governor Haskell

stands high in the councils ofr [sic]

Mr. Bryan. . . . Senator Foraker

represents only the forces which, in

embittered fashion, fought the nomina-

tion of Mr. Taft, and which were

definitely deprived of power within the

Republican party when Mr. Taft was

nominated.

. . . The great and sinister moneyed

interests, which have shown such

hostility to the Administration and now

to Mr. Taft, have grown to oppose

the Administration on various matters

not connected with those which

mark the real point of difference.

For instance, the entire agitation over

Brownsville was, in large

part, not a genuine agitation on behalf

of the colored man at all, but merely

one phase of the effort by the

representatives of certain law-defying cor-

porations to bring discredit upon the

Administration because it was seeking

to cut out the evils connected, not only

with the corrupt use of wealth, but

especially with the corrupt alliance

between certain business men of large

fortunes and certain politicians of

great office. . . .

Mr. Taft has been nominated for the very

reason that he is the anti-

thesis of the forces that were

responsible for Mr. Foraker.

To bolster his statement that nominee

Taft had been consistently

opposed to Foraker as a matter of

political principle, the President

quoted a letter written by the candidate

during July 1907 to "a

friend in Ohio, prominent in Ohio

politics." In this communica-

tion Taft had repelled a suggestion of a

compromise with Foraker

by which Foraker would withdraw his own

presidential candidacy

and assist Taft to a nomination if Taft

would agree to support

Foraker's reelection to the Senate. Taft

had stated in the letter

that his refusal was due to the fact

that Foraker had "opposed

40 Pringle, op. cit., I,

372.

168

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

the vital policies and principles of the

Administration" and had

employed "without scruple, a blind

race prejudice to accomplish

his main purpose."41

Roosevelt's obloquy of Foraker was

received in many quar-

ters as interference in a task which

Taft himself should have

assumed. As the President's aide

explained, "Mr. Roosevelt gets

the credit of 'butting in,' but the fact

is that Mr. Taft made the

appeal to Mr. Roosevelt to help his

cause. Mr. Taft did not want

the odium of expelling Foraker from the

Republican ranks and

nothing would give the President more

pleasure."42 Taft's only

commentary upon Roosevelt's interview

was the statement that he

could not indulge in abuse of Foraker

because "I will not strike a

man when he is down."43

But Foraker was not yet ready to admit

that he was "down."

In an extended statement on September

26, which resembled a

legal brief for a complicated case in

court, the Senator complained

that Roosevelt had accepted Hearst's

charges as fully proved as

soon as made without waiting for an

explanation or accepting the

explanation when offered. Foraker

followed this charge of hasty

judgment upon the part of Roosevelt with

a detailed explanation

of every letter read by Hearst up to

that time, emphasizing that

he had received money only for legal

services concluded before

1901 and for the purchase of the Journal.,

As for Archbold's

letters in regard to bills in the Ohio

legislature, Foraker submitted

a statement by the author of these bills

denying that Foraker had

communicated with him in regard to them

and asserting that he

had withdrawn his proposals from

consideration at the behest of

Governor Nash. The letter in regard to

the Jones Bill, which

Hearst had used to show Standard Oil

influence on Foraker's ac-

tion in the Senate, was revealed by its

very language, declared

Foraker, to be an appeal and not an

order to oppose the bill

and had no status above that of other

letters written by private

citizens to express their convictions

upon pending legislation. And

certainly, felt the Senator, if the

Standard Oil were guiding his

41 Cincinnati Enquirer, September

22, 1908.

42 Archie Butt to his mother, September 25, 1908, in Cincinnati

Enquirer, Janu-

ary 20, 1924.

43 Julia Bundy Foraker, I Would Live

It Again (New York, 1932), 311.

JOSEPH B. FORAKER l69

legislative action, the company would

have regarded very unkindly

his efforts to secure the enactment of

the Elkins Law, under the

provisions of which it was later

assessed a heavy fine. Finally,

said Foraker, "Notwithstanding what

the President says . . .

that I was the representative and

champion and defender of corpo-

rations in the Senate, there is not a

word of truth in any such

statement, whether made by him or

anybody else."44 Thus For-

aker consigned Roosevelt to a prominent

niche in the President's

own "Ananias Club."

In several meetings held after the above

exchange of sallies

by Foraker, Roosevelt, and Taft, Hearst

read further letters from

Archbold to the Senator. None of these

added new information

regarding the matter beyond a more

complete indication of the

total sum paid the Senator. And Foraker,

upon his part, con-

tinued to issue detailed explanations

and defenses, all of them

calculated to show that he had received

money only for legitimate

services rendered as attorney and none

as legislator. In spite of

the bulk of the material issued by the

opposing camps, journal-

istic opinion was rendered upon the

basis of only partial evidence,

for the full story of the Standard Oil

letters did not become

public property until four years later.

Editorial opinion for the most part was

one of strong

censure restrained only by a realization

that Foraker's activities

in behalf of Standard Oil were not

dissimilar from those of other

public servants. Thus the World's

Work declared, "There has

never been any code of ethics,

commercial or political, approved

by American public sentiment, which

excused a man who sat as a

Senator of the United States while he

received money from any

client who wrote him to 'look after'

proposed legislation, either

State or National, however vicious the

proposed legislation may

have been."45 And the

liberal New York Nation agreed, re-

marking:

Senator Foraker's long statement helps

him but little. No one has

supposed that he vulgarly took

bribes--$14,500 for this vote and $15,000

44 Cincinnati Enquirer, September 26, 1908.

45 Editor, "The Archbold-Foraker Letters," in World's Work, XVII

(November

1908), 10851-10853.

170

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

for that. But he is an old enough hand

in politics, State and national, to

know exactly what the Standard Oil

Company is and what he has been

doing in the galley with it. . . .

Moreover, the letters of Mr. Archbold show

that the Standard Oil was desirous of

securing Mr. Foraker's backing or

opposition, as the case might be, for

certain measures and policies. It was

therefore grossly improper for him to

accept retainers from the Standard

Oil and to borrow $50,000 from it.46

More friendly and perhaps sounder

judgments were rendered

by several other journals. Thus the Washington

Herald summed

up the case against Foraker in such a

way as to condone while it

condemned him:

That he erred in entering the service of

the Standard Oil Company in

his state while a United States Senator,

and doubly erred in failing to be-

come an attorney of record, once he took

such employment, none will attempt

to gainsay. And that he erred later, and

still more grievously, in interesting

himself in the rehabilitation of a party

newspaper through the use of

Standard Oil money, is all too plain to

leave room for argument. But

Senators great as Foraker fixed the ethics

guiding him in his law practice,

and party men without number, no less

distinguished than he, the country

over, have not hesitated to put

corporation money into party organs for

political ends. . . .

Foraker is still fortunately able to

offer acceptable documentary proof

that he did not serve the Standard Oil

Company at Washington in his capac-

ity as United States Senator. The charge

against him to the contrary, in

the face of the evidence, falls to the

ground.

Pilloried as he has been, Foraker yet

impresses us as quite as good as

the party that repudiates him. And

generally speaking, we think he has

kept quite as good company.47

Likewise the New York Times averred, "There is no

evidence

whatever that in his course in respect

to Administration meas-

ures he has followed any other guide

than that of his con-

science and his convictions of what the

public welfare demands."

But the Times, too, agreed that

the Standard Oil had no business

to retain a Senator as its attorney and

that the Senator had no

business to accept such employ.48 The Saturday

Evening Post,

while accepting Foraker's statement that

he was paid no money

46 Editor, "The Week," in Nation, LXXXVII (October 1, 1908), 301.

47 September 26, 1908.

48 September 26, 1908.

JOSEPH B. FORAKER 171

for the purpose of influencing

legislation, pictured him as "the

Corporation's Nursemaid."

"Interests of which the Standard Oil

Company is typical," pointed out

the Post, "need not bother to

influence legislation. It is sufficient

for their purposes to in-

fluence legislators merely. That a

Senator with a pocketfull of

corporation money must have a high sense

of the corporation's

utility seems quite obvious."49

Some of Foraker's long established

friends of the newspaper

world found nothing reprehensible in his

activities. The New

York Sun proclaimed Foraker fully vindicated and justified and

recommended his return to the Senate.50

The Dayton Journal, the

Sandusky Register, and the Toledo Times, Ohio papers always

staunch supporters of the Senator, now

demanded his vindication.51

This persistence of strong sympathy and

support even after the

crushing blow of the Hearst revelations,

and the Roosevelt and

Taft repudiations was a remarkable

phenomenon.

Back to the Foraker fold at this time

came also one lost sheep.

Warren Gamaliel Harding, whose life was

to end in tragedy be-

cause he loved his friends well but not

wisely, wrote to express his

unshaken faith in the old Senator.

"If you are a candidate to

succeed yourself," stated the

Marion editor, "any influence I may

have will be gladly exerted in your

behalf. My faith in your

honesty and integrity have never been

impaired in the slightest de-

gree, and my reverence for your ability

is abiding."52

By the time he received this helpful

message from Harding,

Foraker had determined to seek

reelection to the Senate. To the

Marion editor Foraker wrote that the

Hearst charges left him no

other choice. In the pending contest the

Senator anticipated great-

est competition from the candidacy of

Charles P. Taft, the Presi-

dent-elect's half-brother, who had so

effectively managed the Taft

campaign in Ohio.53 It did

appear for some time that the Tafts

might place another member of the family

in the public service.

The President-elect had consistently

refused during the campaign

49 October 31, 1908.

50 November 20, 1908.

51 See clippings in Mrs. Foraker's Scrapbooks, IX.

52 November 6, 1908.

53 Foraker to Harding, November 7,

1908.

172

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

to compromise with Foraker and had

hinted that he would oppose

Foraker's efforts to retain his seat.54

Late in December adminis-

tration influence was thrown against

Foraker as Charles P. Taft

emblazoned the front page of the Times-Star

with the headlines,

"Roosevelt Believes to Support

Foraker is Party Treason." The

story accompanying this caption stated

that Taft would exert his

influence to prevent the reelection of

Foraker.55 It is well known,

however, that William Howard was not so

pleased with his

brother's senatorial candidacy.

Eventually Charles P. Taft, facing

certain defeat by Burton, retired from

the race before the vote was

rendered by the assembly. Foraker also,

seeing the impossibility

of gaining reelection, withdrew his

candidacy. Theodore E. Bur-

ton of Cleveland was chosen to fill his

seat in the Senate and

served there until 1914.56

Thus in the short space of five months

Foraker had been

converted from a feared and potent

insurgent chieftain of the Re-

publican Party to a despised and

proscribed ex-Senator whose in-

fluence was quite negligible. The manner by which this trans-

formation was accomplished remained a

natter for comment in

the years following Foraker's enforced

retirement. The outstand-

ing questions for speculation were,

"Where and how did Hearst

obtain the letters which he read?"

and "Are there more?" Dur-

ing the year 1912 Hearst made a

complete summation of the

"Lesson of the Standard Oil

Letters" in his magazine, including

the majority of the letters in his

possession.57 Partially due to this

resurrection of the Standard Oil affair,

which touched upon the

public careers of many politicians

besides Foraker, and partially

because of more general comments on

corporate contributions to

party treasuries in the presidential

campaigns'of 1904, 1908, and

1912, the Senate of the Sixty-Second

Congress set up a subcom-

mittee of its Committee on Privileges

and Elections to hear testi-

mony relating to the financing of those

campaigns. This subcom-

mittee, under the chairmanship of Moses

E. Clapp of Minnesota,

54 Roosevelt to H. C. Lodge, June 27,

1907, Roosevelt and Lodge, op. cit., II,

272; Pringle, op. cit., I, 322.

55 December 30, 1908.

56 Notes, II,

351-352.

57 William Randolph Hearst, "The Lesson of

the Standard Oil Letters," in

Hearst's Magazine, XXI (May 1912), 2204-2204c.; Anon. ("J. E."),

"The History of

the Standard Oil Letters," in Hearst's

Magazine, XXI (May 1912), 2204d-2216.

JOSEPH B. FORAKER 173

sat from June 14, 1912, to February

25, 1913, taking 1,596 pages

of testimony. Of this total about 300

pages dealt with the Hearst

disclosures and provided a much better

background for these

revelations than had existedin 1908.58

When Hearst declared in his speech at

Columbus on Septem-

ber 17, 1908, that the letters he

proposed to read had been handed

to him only that afternoon, he was not

telling the whole truth.

The Standard Oil correspondence had been

delivered to the Hearst-

owned New York American by

December 1904, probably with

Hearst's knowledge. Although the letters

may have been brought

to Hearst at the time of the Columbus

speech by John Eddy,

former managing editor of his New York paper,

as Hearst

claimed, the speaker had been prepared

in advance for their re-

ception. Thus Hearst had withheld for

over three years the pub-

lication of the letters which disclosed

"the genuine danger that

threatens our republic."59

The letters had been obtained by the

Hearst interests in the

following manner. Late in 1904 two

employees of John D. Arch-

bold, vice-president of the Standard Oil

Company, conceived a

scheme for making some "easy

money." One of these, William

W. Winfield, was the file clerk,

messenger, and door tender for

Archbold. The other, named Charles

Stump, was a clerk. It was

Willie Winfield who was the instigator

of the plot. The stepson

of Archbold's aged and trusted butler,

Willie had a desire to

gamble and indulge his natural talent

for the social graces. So it

was decided that the two of them should

remain after the other

employees had left, abstract interesting

letters from the files, and

sell them to the highest bidder.

Eventually a third man was

brought in as agent, disposing of the

letters in batches to various

editors of Hearst's New York

American, the first of those receiv-

ing letters being John Eddy, who brought

them to Hearst on the

day he spoke in Columbus. Each of the

batches of letters was

taken by the agent to the editorial

offices of the New York Ameri-

can, photographed during the night, paid for according to

the

value of their contents and returned the

next morning to the

58 Clapp Committee Investigations.

59 Hearst

testimony, Clapp Comm. Invest., 1253, 1261; Wm. W. Winfield's

statement, ibid., 1395.

174

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

Standard Oil offices. In all the two

received about eight or nine

thousand dollars (possibly more)

fortheir perfidy. All this, of

course, tends to lessen the impression

that Hearst was a super-

patriot in making his disclosures, but

does not influence in the

slightest the judgment which should be

placed upon Foraker's

relationship to the Standard Oil

Company.60

During the course of the Clapp Committee

investigations

Hearst made public all the letters which

he had in his possession

concerning the Standard Oil Company and

its affairs. Likewise

at this time Foraker made his last

public statement (aside from

his biography) in vindication of his

personal integrity. It is,

therefore, possible upon the basis of a

careful examination of this

testimony and collateral evidence to

render a reasonably fair judg-

ment concerning Foraker's rectitude with

respect to his employ-

ment by that great and powerful

corporation.

Five different aspects of the

Foraker-Archbold letters are

of moment in considering the Senator's

activities: his legal services

for the company, the purchase of the Ohio

State Journal, his in-

fluence upon Ohio legislation, his aid

or opposition to the careers

of Ohio politicians, and his reaction to

suggestions concerning

legislation pending in the United States

Senate.

The Standard Oil letters read by Hearst

reveal that during

the single year of 1900 Foraker received

the sum of $44,500 paid

without the specific statement that the

money was compensation

for legal services.61 Nevertheless

Foraker did produce convincing

proof that he rendered the Standard Oil

legal services between

December 1898 and the late months of

1900. Moreover the Sena-

tor presented evidence effectively

confirming his statements that

he had devoted a great deal of time in

regard to the anti-trust

procedings against the Standard Oil in

Ohio, that the prosecution

realized his position as attorney for

the trust, and that the difficult

task of preparing complicated briefs for

a case involving such vast

sums of money warranted a heavy fee.62

The solution of the case

by reorganization of the company under

New Jersey laws was a

60 Ibid., 1303-1304, 1341-1344, 1395, 1419, 1445, 1492, 1522;

Carlson and

Bates, op. cit., 165-166.

61 Anon., "The History of the

Standard Oil Letters," loc. cit., 2207-2208.

62 Clapp Comm. Invest., 1324-1334.

JOSEPH B. FORAKER 175

decision which allowed the Standard Oil

to continue a very aggres-

sive aggrandizement of its interests

until later checked by federal

legislation. Thus, while $44,500 might

represent a very generous

fee for Foraker's activities, the

impartial observer is inclined to

find the legal services rendered

sufficient explanation of the size

of the fee. This conclusion, however,

while removing implications

of direct bribery, does not avoid the

criticism that it was improper

for Foraker to accept employment by such

an aggressive busi-

ness corporation as the Standard while

he was in the Senate.

The fact that other public officials had

followed a similar course

cannot but leave the impression that the

public condemnation of

such action at the time of Foraker's

exodus from the Senate repre-

sented considerable progress in the

enlightening of public opinion.

Similarly an examination of all the

evidence with respect to

the $50,000 draft given to Foraker in 1902 brings a

conviction

that he spoke the exact truth in his

explanation that this sum was

a loan advanced to purchase the Ohio

State Journal and that the

money was returned when the projected

purchase could not be

carried out.63 But again,

accepting Foraker's explanation, it re-

mains to be deprecated that a public

official would place corpora-

tion money in a large newspaper for the

purpose of controlling its

editorial policy.

The various letters from Archbold to

Foraker concerning

Ohio legislation constitute the most

damaging evidence against the

Senator. The evidence discloses that

during February and March

1900, while Foraker was employed as attorney for the

Standard

Oil, he received three different letters

from Archbold requesting

him to exert his influence against

"objectionable bills" before the

Ohio Assembly. The first payments of

$15,000 and $14,500 fol-

lowed closely upon the heels of these

letters. Whether Archbold

considered the money as payment for

legal services alone cannot

be stated with certainty. But there is

no doubt that the corpora-

tion executive believed that Foraker was

"looking after" the legis-

lation concerned. Foraker upon his part denied that he had

exerted any influence with regard to the

legislation to which Arch-

63 Ibid., 1293-1294, 1316-1317; Letter of Charles L. Kurtz to

Foraker, July 29,

1901, refers to purchase of Journal by

"Mr. Rodgers."

176 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

bold referred and displayed in proof a

letter from one M. W.

Hissey, who had acted as legislative

agent for Senator Hanna.

Hissey related that he had been

"watching" legislation for Hanna

during 1900, and that the bills in

question had been withdrawn

by direction of Governor Nash after

consultation with Hanna

and Foraker. This statement was

confirmed by the authors of the

bills who reported that Foraker had

brought no influence upon

them to secure the withdrawal of their

measures.64 It is certain,

however, that during 1902 Foraker

concerned himself with a

"curative" measure in the Ohio

General Assembly to benefit the

Cincinnati Traction Company and one

suspects that he may have

carried out Archbold's request by

indirect means and "seen to

it" that these bills were not

passed at this time. Although not

legally contradictory to his obligations

as a Senator, such action

was surely not in accord with the

highest ideals of public service.

Also dealing with Ohio politics were the

letters of Archbold

late in 1902 and early in 1903 requesting

Foraker's influence in

behalf of Judge Burket, a candidate for

relection to the State

Supreme Court, and in opposition to the

candidacy for the attor-

ney-generalship of Smith Bennett, who

had been instrumental in

the suit against Standard Oil in Ohio.

With regard to these letters

the only possible comment is to repeat

Foraker's explanation that

Archbold's letters did not determine his

attitude. He had sup-

ported Judge Burket because he had known

the justice for many

years and believed him a capable man. He

had gone contrary to

Archbold's request and favored the

candidacy of Smith Bennett.65

It should also be noted that, with the

full explanation of the Journal

loan, no indication of a money payment

within two years of these

matters can be found.

The final aspect of the Standard Oil

letters is that which con-

cerns Foraker's public service. On

February 25, 1902, the vice-

president of the petroleum corporation

wrote Foraker a letter

opposing an anti-trust bill introduced

by Senator Jones of Ar-

kansas. Hearst asserted that this letter

constituted a "direction"

to Foraker to oppose the bill. Foraker,

to the contrary, declared

64 Clapp Comm. Invest., 1280-1281, 1284-1285, 1318-1320,

1339-1340.

65 Ibid., 1279.

JOSEPH B. FORAKER 177

that the letter had only the status of

an appeal of any private citi-

zen and denied all recollection of

having received it, indicating

that he had not conceived it of much

moment at that time. In-

ternal evidence supports the Senator's

position. Archbold began

his letter with the words, "I

venture to write you," and after com-

plaining, "It really seems as

though this bill is very unnecessarily

severe and even vicious,"

continued, "I hope you will feel so about

it and I will be greatly pleased to have

a word from you on the

subject."66 Although, of course,

this tone might be adopted in

dealing with such a dignified and

self-esteeming correspondent,

the letter does not, on the face of it,

convict Foraker of being a

paid agent of the corporation.

Finally there is no indication in the

letters read by Hearst to

contradict Foraker's statement that he

received no money except

for legal services and that these

services were completed before

1901. Nor can it be denied that Foraker helped to frame the

Elkins Law under which the Standard Oil

paid a heavy fine. Yet

Foraker was, without doubt, a friend and

defender of the corpora-

tions. This fact was not a secret.

Cincinnatians had long been

aware of his legal relationship to the

municipal traction company

and Ohioans generally had been informed

of his services as

attorney for a number of railroads. It

was widely known that he

continued his legal activities for

important clients while in the

Senate. Probably the public was shocked

from its apathy in

regard to Foraker's corporate

relationship by the Hearst campaign

addresses, which linked corruption also

to his career. When proof

of his personal integrity had been

offered and generally accepted,

there still remained a shocked awareness

of the Senator's greater

concern with the wishes of the world of

business than with the

desires of the man on the street.

Regardless of the justice of the Hearst

charges, they were

chiefly responsible for the conclusion

of Foraker's public career on

March 3, 1909. The Senator retired a man

of 63, resentful of the

injustice done him by the members of his

own party and desirous

of expunging the mark of infamy which

had been set upon his

public career. As a consequence, he

again sought office before his

66 Ibid., 1286, 1288-1289, 1292-1293.

178 OHIO ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

death, believing that the favorable vote

of the people would be an

indication that they considered his

defense convincing. This vin-

dication, however, was denied him, and

he sought it through

another means, the writing of an

exculpatory autobiography. An

interesting result of the publication of

this work was that his old

adversary, Theodore Roosevelt, wrote him

to laud his "absolute

Americanism" and to say,

"There is no use in raking up the past

now, but there were some things told me

against you, or in refer-

ence to you, which (when I consider what

I know now of my

informants) would have carried no weight

with me at the time

had I been as well informed as at

present."67 Whether Roosevelt

had reference in this statement to the

Standard Oil matter is open

to question, but there was, at least,

consolation in the tribute. But

in spite of his heartfelt efforts to

destroy the shadow of scandal

which lay over his career, Foraker's

name was not freed of the

stigma of the charges brought against

him and his political career

has suffered an obfuscation seldom

equalled in American history.

67 Roosevelt to Foraker, June

28, 1916, pub. in New York Herald, February 4,

1924, in New York Times, February

10, 1926, in Cincinnati Commercial Tribune,

January 7, 1927.

JOSEPH B. FORAKER AND THE STANDARD OIL

CHARGES1

by EARL R. BECK

Instructor in History, Ohio State

University

In 1908 Joseph Benson Foraker, then

serving his second

term in the United States Senate, was

one of the outstanding

figures in politics in the nation.

Foraker had won national notice

for his aggressive, uncompromising fight

against the Hepburn

Rate Bill of 1906 and for his strident

attacks upon the executive

action of President Theodore. Roosevelt

which led to the discharge

without honor of a battalion of Negro

soldiers involved in a shoot-

ing affray at Brownsville, Texas. The

latter issue aroused the

personal ire of the President and he and

Foraker had met in a

heated discussion at the Gridiron Dinner

of 1907. To these diffi-

culties between the two men was shortly

to be added a further

cause for rancor, the opposition of

Roosevelt to Foraker's presi-

dential aspirations.

During Foraker's long career in politics

his pathway to a

presidential nomination by the

Republican Party was constantly

blocked by superior claims for

recognition upon the part of some

other Ohio statesman. Thus in 1884 and

1888 it was John Sher-

man who demanded the solid vote of the

Ohio delegation at the

Republican National Convention as a

guerdon for thirty years of

faithful service. In 1892, 1896, and

1900 William McKinley, Jr.,

came to the fore, receiving Ohio's vote

in 1892 in an effort to avert

the renomination of Benjamin Harrison

and in the two succeeding

campaigns as the result of a political

compromise with the Foraker

forces. In 1903 Mark Hanna was

considered the great man of

politics in the Buckeye State and

Foraker averted his possible

nomination for the 1904 campaign only

by springing to the staunch

1 This article is based largely upon

the author's unpublished doctoral dissertation,

written at the Ohio State University,

1942.

154

(614) 297-2300