Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

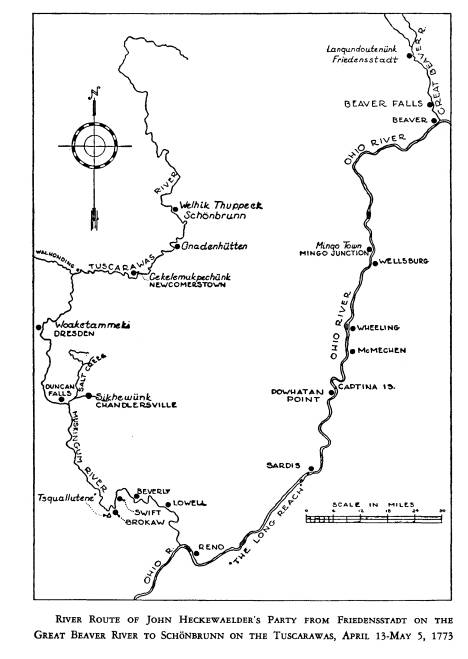

A CANOE JOURNEY FROM THE BIG BEAVER TO

THE

TUSCARAWAS IN 1773: A TRAVEL DIARY OF

JOHN HECKEWAELDER

Translated and edited by AUGUST C. MAHR

Professor of German, Ohio State

University

By 1772, due to circumstances beyond

their control, the

missionaries of the Moravian Church

among the Indians in Penn-

sylvania had found it inevitable to

abandon their two mission

stations on the upper North Branch of

the Susquehanna: Friedens-

hiitten, about one mile down the river

from present-day Wyalusing,

and Schechschequanniink (present-day

Sheshequin), about twenty-

five river-miles upstream from

Friedenshiitten.1

Between June 11 and the middle of

August 1772, a total number of

over two hundred Indian converts of the

Susquehanna mission,

under the leadership of the two

Moravian missionaries, the Rev.

Johannes Ettwein and the Rev. Johannes

Roth, migrated, partly

by water, and partly by land, from the

Susquehanna to the Big

Beaver, where the Rev. David Zeisberger

had founded, in 1770,

a new mission station among the Monsey.

The Monsey consti-

tuted the Wolf Tribe of the Lenni

Lenape, or Delaware, Indian

nation. The two other tribes were the

Unami (Turtle Tribe) and

the Unalachtigo (Turkey Tribe). Since

the beginning of the 1720's,

practically the entire Lenni Lenape

nation had gradually left its

old hunting grounds in eastern

Pennsylvania, migrating into the

Ohio basin, where the majority, the

Unami and Unalachtigo, had

settled in what today is the eastern

half of the state of Ohio,

while the Monsey established themselves

in northwestern Penn-

sylvania on the Allegheny, Big and

Little Beaver, and Mahoning

rivers.

Apart from the negative reasons for the

abandonment of the

1 A comprehensive account of the labors

of the Moravian Church in the Indian

mission field of North America in the

eighteenth century can be found in Bishop

Edmund deSchweinitz' excellent biography

of that church's greatest missioner among

the Indians, entitled The Life and

Times of David Zeisberger (Philadelphia, 1870).

The book also contains brief biographies

of the other Moravians mentioned in the

present pages: Ettwein, Roth, and, last,

but not least, John Heckewaelder.

283

284

Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Quarterly

Susquehanna mission, there had also

been a strongly positive

motivation for Zeisberger and the

Moravian Mission Board to shift

the Indian mission's center of gravity

westward: it was the ever

more urgent invitation, on the part of

the great Delaware chief

Netawatwes and his grand council, to

move the Moravian mission

into the new Indian territory in

northwestern Pennsylvania and the

Muskingum basin. The founding of

Friedensstadt (or Lang-

undouteniink), in 1770, in the Monsey

country on the Beaver

River, had been Zeisberger's initial

step in following this invitation.

But even before the Friedenshutten and

Schechschequanniink con-

verts had started, in the summer of

1772, on their westward migra-

tion under Ettwein and Roth, the

rum-sodden heathen Monsey who

lived everywhere around Friedensstadt

had proved such unbearable

neighbors that Zeisberger, upon urgent

entreaties from Netawatwes,

had most willingly selected a new

mission site on the Tuscarawas

River, only twenty miles upstream from

the chief's capital. Here,

in May 1772, he founded the mission of

Schonbrunn; and here,

he decided, the Susquehanna converts

were to be taken. Friedens-

stadt, doomed to be abandoned, was

merely to serve as a temporary

receiving station: a stopover point

where he and his fellow mis-

sioners could work out careful and

effectual plans for the gradual

transferring of all their converts to

the Tuscarawas Valley.

Almost immediately upon the arrival at

Friedensstadt of the

weary migrants under Ettwein and Roth,

Zeisberger began to carry

out his intentions, with the aid of

Ettwein and John Heckewaelder,

the latter only recently appointed

assistant missionary for the new

area.

When, in the pursuit of this

enterprise, Friedensstadt was

definitely abandoned in 1773, Johannes

Gottlieb Ernst Hecke-

waelder, twenty-nine years old at the

time, was chosen as the

leader of a consignment of converts who

were to travel by water

in a flotilla of canoes from

Friedensstadt to Schonbrunn. The

others traveled across country, driving

a large herd of horned

cattle along with them, many of the

animals having formerly

hooved it all the way from the

Susquehanna to the Beaver.

Heckewaelder's diary covering his

strenuous river journey is

A Travel Diary of John

Heckewaelder 285

presented in these pages. Zeisberger's

junior by twenty-two years,

he was for a long time his faithful

collaborator in the Tuscarawas

missions, one of which, Salem, he

founded in 1780; in its chapel

he was married in the same year to

Sarah Ohneberg. Due to the

ill health of his wife he retired from

the Moravian Indian mission

work in the autumn of 1786 and returned

with her to Bethlehem,

Pennsylvania, the seat of the Moravian

mother church in North

America. Subsequently, he rendered

numerous useful services to

both his church and the outside world,

and spent the last few

years of his life assembling the rich

memories of his active career

in two books of lasting value: Account

of the History, Manners,

and Customs of the Indian Nations (Philadelphia, 1819);2 and

Narrative of the Mission of the

United Brethren Among the

Delaware and Mohegan Indians (Philadelphia, 1820).3 As his

last literary effort he prepared in

1822 a collection of "Names,

which the Lenni Lenape, or Delaware

Indians, gave to Rivers,

Streams, and Localities within the

States of Pennsylvania, New

Jersey, Maryland, and Virginia, with

their Significations." This

work was communicated to the American

Philosophical Society

in Philadelphia as early as April 5,

1822, but not until twelve

years later did it appear in print in Transactions

of the American

Philosophical Society.4

On the river journey he proved a

dependable and resourceful

leader; there were no accidents; none

of the travelers, not even any

of the old people, died during the

trip; nor were property and

provisions lost or spoiled. Once, on

the Muskingum, when the

seed corn had been wetted in a bad

rainstorm and threatened to

sprout, he called a stop in order to

dry the grain. Another time,

when the strain had become excessive,

camp was made at once

and a sweating oven built for the weary

boatmen to sweat out

their fatigue. No opportunity was

overlooked or time spared by

Heckewaelder for establishing and

maintaining friendly relations

with the West Virginia settlers along

the Ohio, as the perusal of

2 Henceforth to be cited as

Heckewaelder, History.

3 Henceforth to be cited as

Heckewaelder, Narrative.

4 Volume IV, New Series (1834), 351-396.

286

Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Quarterly

the diary readily shows. He was equally

anxious to assure for him-

self, for his charges, and thereby for

the Moravian mission the

goodwill of the great chief and his

grand council as soon as the

Lenape capital was reached, the same

as, a day or two previously,

a visit had been paid to the Shawnee in

their towns farther down

the Muskingum, where the year before

Zeisberger likewise had

visited. Although they were worn to the

utmost, he safely delivered

his human freight with their belongings

at Schonbrunn, their des-

tination, after a journey of

thirty-five days.

Viewing in retrospect his creditable

enterprise, Heckewaelder

many years later wrote these lines:

On the 13th of April, 1773, this handsome

village [Friedensstadt, on the

Beaver River] was evacuated; one part

of the congregation travelling

across the country by land, and the

other division, accompanied by the

writer of this narrative, in twenty-two

canoes, loaded with the baggage,

Indian corn, etc., by water, first down

the Big Beaver to the Ohio-thence

down that river to the mouth of the

Muskingum-thence up that river,

according to its course, near two

hundred miles, to Shonbrun [Schonbrunn],

the place of destination.5

The distance of "near two hundred

miles," as given in this

brief and modest account, evidently

refers solely to the travel on

the Muskingum and Tuscarawas rivers,

which, as will be presently

shown, Heckewaelder himself in a later

and more precise state-

ment estimated at "160

miles." The total distance of the entire

water journey from Langundouteniink

(Friedensstadt) to Schon-

brunn, according to figures obtained by

courtesy of the water

division of the Ohio Department of

Natural Resources, was 330

river miles. In an enumeration of his

journeys between 1762 and

1814, which also gives the distances,

Heckewaelder, for the year of

1773, had entered the following data:

In April, down Beaver creek, by water,

................... 30 [miles]

Thence down to [the] Ohio, to the mouth

of the Muskingum,

etc.,........................................... 150

Thence up the Muskingum, by water, to

Schonbrunn 1606

5 Narrative, 126.

6 Transactions of the Moravian Historical Society, I (1876), 234.

A Travel Diary of John

Heckewaelder 287

This makes a total of 340 miles, that

is, a discrepancy of 10 miles

between Heckewaelder's figures and

those of the water division.

The explanation appears to be that

Heckewaelder's 30 miles of

river journey "down Beaver

creek" (from present-day Moravia

[Lawrence County, Pennsylvania] to the

mouth of the Beaver

River) are by 10 miles in excess of the

actual distance of slightly

more than 20 miles. Considering that

Langundouteniink may have

been situated a brief stretch upstream

from present-day Moravia,

and that Heckewaelder may have regarded

the location of his

night camp (near present-day Beaver) as

the terminal point of his

Beaver River journey, one may concede

to him five more miles but

no more, thus arriving at a total of

335 miles.

The account of this journey presented

below is a translation

from the German original in the

Moravian Archives, Bethlehem,

Pennsylvania. It is for the first time

that it appears in print. The

whole diary is given, the only change

from the original manuscript,

aside from the translation, being the

italicizing of the dates for the

convenience of the reader.

BROTHER JOHN HECKEWAELDER'S REPORT OF

THEIR TRAVEL BY WATER

FROM LANGUNDOUTENUNK TO WELHIK THUPPEEK

[SCHONBRUNN] IN

APRIL 1773.

The 13th of April, we departed

together in twenty-two canoes from

Langundouteniink and reached the falls7

at night. Brother Schebosch,

Johannes, and a few more Brethren

reached us there too, to take our

heaviest things with their horses by

land as far as below the falls.

The 14th, the latter turned back

because the water was rising and they might

have been cut off from journeying

overland to Welhik Thuppeek.8

The 15th. Since many of our

canoes were loaded too heavily, we resolved

to empty one of them; the Sisters and

some of the Brethren were supposed

7 The rapids in the Great Beaver River

near present-day Beaver Falls, Beaver

County, Pennsylvania, about five miles

upstream from the mouth of the Beaver.

8 Schebosch, Johannes, and a few other

Brethren evidently traveled to Welhik

Thuppeek (Schonbrunn) by land, going

directly west by way of the Great Trail.

The Great Trail in those days was a much

traveled route from Pittsburgh to Detroit,

equally popular with Indians and white

traders. After it had reached the mouth of

the Big Beaver, it led over the

highlands north of Lisbon, Ohio, and descended along

Sandy Creek to the Tuscarawas River,

which it crossed for its final destination,

Detroit. From the crossing place to the

mission site of Schonbrunn either the

Tuscarawas waterway could be used or a

trail along the river.

288 Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Quarterly

to carry the contents below the falls;

and some Brethren were sent out to

hunt, who brought five deer into camp in

the evening.

The 16th. The Indians found the

head of a man close to our camp. The

man had apparently been killed in the

last war, since his skull had been

split by an ax.

Our Indians pitied him, because he had

died an innocent victim. It was

still raining; hence, the strongest and

most courageous Brethren resolved

to ride the empty canoes over the falls.

They endangered their lives by

doing so, and two of our people were

nearly drowned, but there were

always a few Brethren with a canoe ready

to help in case of emergency;

yet they all traveled safely down,

although sometimes the canoes were half

filled with water.

The 17th. The canoe which they

had begun to build the day before

yesterday was completed, so we did not

tarry any longer but entered into

the Ohio this same evening and made camp

beneath the old French fort,

the chimneys of which in parts are still

standing.9

The 18th. Now that we were on the

Ohio, we made an agreement with

each other on how we would conduct our

trip, namely, that we would travel

until evening, if the wind were quiet,

because the river is high. Today,

now and then, we saw plantations of the

white people on the other side

of the river; and in the evening we made camp close to the Mingo Town.10

The 19th. We passed this town in

the morning. The Mingo wanted to

talk with us, but there was no one among

us who understood their language.

From here, a year ago, Brother David

started with his traveling party

overland to Welhik Thuppeek.11 A few

miles farther down, a white man

called us and invited us to come ashore

and to rest a little, but we did not

want to delay ourselves. We told him the

reason, to which he replied:

9 Probably a discarded French stronghold

in the place of the later Fort McIntosh,

which was erected in 1778 near the mouth

of the Beaver in the vicinity of present-

day Beaver, Beaver County, Pennsylvania.

The complete distance covered since the

13th of April, their day of departure

from Langundoutenunk, was only slightly more

than 20 miles; this was due to the

transportation difficulties at the Beaver rapids

as described above.

10 The distance covered on the 18th from

near present-day Beaver to the camp

above Mingo Town was about 40 miles.

11 On the 14th of April, 1772, the Rev. David Zeisberger set out from

Friedens-

stadt with a group of five married

couples of converts, several children, and one

unmarried man, for the Tuscarawas

Valley, where they eventually laid out the

mission of Schonbrunn. As a year later

John Heckewaelder did, Zeisberger too

directed the baggage, attended by a few

men, down the Ohio and up the Muskingum

in canoes.

A Travel Diary of John

Heckewaelder 289

"In that case, I wish you a happy

journey, you good people."12 Again we

saw houses and plantations of white

people on the east side of the river

in different places.13 No

sooner had we gone ashore in the evening14 than

six white people appeared across the

river from us and started talking

to me; but the river was so wide that we

were not able to understand

each other very well, hence I paddled

across with the Brethren Anton and

Boas. They questioned us about many

things for about half an hour, but

they were quite modest, most of their

questions being about our religion and

doctrine. Some of them I will note down;

for example: "What kind of

Indians are these, and where do they

come from?" - Answer: "They

are

a Christian Indian congregation and come

from Beaver Creek." - "Where

are they going?" - "To the Muskingum." - "Are these the Moravian

Indians?" - Answer:

"Yes." - "Do they have a minister with them?" -

Answer: "Yes, they are two

congregations, and each of them has its

teacher." - "Of what religion are their

teachers?" - "They are of the

Brethren's." - "Do they

receive an annual salary from the King or from

a certain society?" - "No." - "How then are they supported?" - Answer:

"The members of the Brethren's

Congregation voluntarily put up the money,

each according to his capability, and

their teachers are supported by this

voluntary contribution." Whereupon

they said to each other: "That, indeed,

is praiseworthy. Can their teachers talk

with them in their language?" -

"Yes." - "Did some of

them really come to the point where they truly

believe that there is a God in

Heaven?" - "Yes." - "Do they let them-

selves be baptized?" - "Yes." - "Are these two baptized, and what are

their names?" - Answer: "They

are both baptized, and they are called

Anton and Boas." - "Are they

faithful even after they are baptized?" -

Answer: "It seldom happens that any

of them leaves us again; you see a

good example here in this man Anton, who

has kept his faith for twenty

years." - They said to each other: "One can see in this man's face

that

he is a true Christian"; and they

further asked: "Do they celebrate the

12 This man may have been one of the first

settlers on the site of the later city

of Wellsburg (Brooke County, West

Virginia), Jonathan, Israel, or Friend Cox,

who in 1772 here built a log cabin on

the river bank. Work Projects Administration,

West Virginia: A Guide to the

Mountain State (New York, 1941), 485.

Wellsburg

is just "a few miles farther

down" from Mingo Town (today, Mingo Junction).

13 Among them, to be sure, the cabins of the first settlers of Wheeling,

West

Virginia, the three Zane brothers,

Colonel Ebenezer, Jonathan, and Silas, who in 1769

had here established themselves. West

Virginia Guide, 283.

14 This night-camp (April 19-20) was

across the river from present-day McMechen

(Marshall County, West Virginia). Its

distance from the previous one, above Mingo

Town, was about 25 miles.

290 Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Quarterly

Sabbath and keep it holy, and do no work

on that day, not even hunting ?"-

Answer: "They celebrate the Sabbath

as it is usual with other Christian re-

ligions." - "Which day do you regard as the

Sabbath?" - Answer: "The

first day of the week." - "Do

they have any meetings except on the

Sabbath?" - Answer: "They have meetings once,

sometimes twice, every

day." - Thereupon they said:

"You see, they are true Christians. Now if

one of them does not behave himself,

what do you do with him?" -

Answer: "We reprimand him, and if

our reprimands do not help, he is

excluded from the Congregation;

sometimes he is even sent away." - "Do

you hold school for them?" -

"Yes." - "In what language?" - In

their own." - They said: "That is right." - "We think that as long as

they do not live entirely among the

white Brethren they will not be capable

of learning their [the white Brethren's]

language, because many of them are

too old, and others too little apt to

learn foreign languages." - Finally

they asked: "Don't you have any

trade with them, and don't they give you

part of their hunting bag?" -

Answer: "We do not have any trade with

them, nor do we receive anything from

them. We are satisfied with a

primitive mode of living, and when we

see that all along some of them are

converted and become believers, we

consider ourselves well paid." - Upon

which, they said: "It cannot in the

least be questioned that God is with you

and blesses your work. The minister

Jones, too, has given this testimony of

you. He has told us a lot about you. He

has also seen one of your ministers

and talked with him (that was Brother

David, with whom he had talked

in Gnadenhutten).15 He knows you as a

true Christian congregation in the

Indian country, and we wish you success

and God's blessings for your work,

so that your numbers might more and more

increase." Thereupon we parted,

because night had fallen.

The 20th. Just when we were about

to start on our journey again, the

same people came across the river and

looked at all our people and our

whole outfit. They pitied the old

people, because of the hardships of travel-

ing; they fondled the children, and

wished to all of us a happy journey.

Now I learned that they were Baptists;

one of them was a gentleman from

15 Soon after the arrival in the

Tuscarawas Valley of the Susquehanna converts

it proved necessary to found a separate

mission station named Gnadenhutten, ten miles

downstream from Schonbrunn, because the

Mohican converts from Schechschequannunk

could not get along with the Lenni

Lenape from Friedenshutten and insisted on living

at a different place. "The minister

Jones," here mentioned, was a Baptist preacher

from Freehold, New Jersey, who in 1772

paid a missionary visit to the Shawnee

along the Scioto. On his return trip

overland early in 1773 he stopped over at

Gnadenhutten, where on February 13 he

had the interview with Zeisberger here

referred to by Heckewaelder.

291

292 Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Quarterly

Philadelphia.16 They sat down

on the river bank and were astonished at

the general quietude of our people. In

the afternoon some of our men

wanted to stop and hunt, because they

had no more meat; but since the

weather was so beautiful, and there was

no wind, we did not want to lose

any time. But after we had traveled a

bit farther and encountered a little

island,17 they had a notion

that deer would be on the island. We encircled

it with our canoes and put some people

with a few hounds ashore, where-

upon at once four deer jumped into the

water, three of which we obtained.

The 21st. We started on our journey again early in the morning.

The

scenery was very beautiful here. Part of

the bottoms looked like orchards.

I saw many trees and herbs which I did

not know. The Indians said:

"Here we are strangers; the

scenery, the trees, and the grass are different

here." Again we saw houses of white

settlers; some of the people were

standing at the river bank and calling

out to us: "Where are you people

going?"; and I answered: "Up

the Muskingum to settle there"; whereupon

one replied: "I wish you were going

ten thousand times farther." Another,

standing beside him, reprimanded him,

saying: "You are mistaken about

these people. I am sure they are the

same of whom the minister Jones18

has told us so many good things; don't

you see how quiet and well-behaved

they are? None of them has his face

painted, and they all look their natural

selves";19 and they said: "We

wish you a happy journey."

16 From the Rev. Jones's travel diary,

entitled A Journal of Two Visits Made to

Some Nations of Indians on the West

Side of the River Ohio, in the Years 1772

and 1773 (Burlington, Vt., 1774; reprinted, New York, 1865),

pages 34-38, it

appears that these Baptists were from

Philadelphia and had traveled to the Ohio

with the Rev. David Jones and another

Baptist minister, the Rev. John Davis; they had

arrived at the settlement of Dr. James

McMechen, on the site of present-day

McMechen (Marshall County, West

Virginia), on December 2d (or 3d), where the

Rev. Davis died on December 13th. Dr.

James McMechen was that "gentleman from

Philadelphia," here mentioned.

17 This little island must have been

Captina Island, since there is no other island

between it and McMechen. The channel

between Captina Island and the West

Virginia river bank being very narrow,

deer could easily cross over from the mainland

and back.

The distance covered on April 20

(McMechen-Captina Island) was about 10

miles.

18 These people most likely were of the

Cresap family, who since 1771 had been

settling in the river flats opposite

present-day Powhatan Point (Belmont County,

Ohio). On the United States Geological

Survey map these flats are named "Cresap

Bottom." The Rev. David Jones must

have told them about the Moravian Indians

after his overland return from the

Shawnee and Delaware territory to the McMechens,

with whom he subsequently stayed for

three weeks (February 28-March 19, 1773),

obviously spending part of his leisure

time visiting the white settlers along the

neighboring West Virginia bank of the

Ohio. Jones, Journal, 110, 112.

19 The Moravian Mission would not permit

its Indian converts to paint their

faces as did the heathen Indians.

A Travel Diary of John

Heckewaelder 293

It is true, this minister outdid himself

in telling others how much he had

been pleased with our Indians; and that

is the reason why all the people in

this vicinity love and respect us.

Several people told me that, if war should

break out again, we would suffer no

harm. Before I forget it, a bear was

shot today.

The 22d. We traveled through the

most lovely countryside of our entire

trip; crooked as the Ohio runs in other

places, here it went straight ahead,

and its course was W.S.W.;20 nor did we

see mountains any more, but

level bottoms on both sides; the trees

were for the most part in their full

foliage, and many trees bloomed, as did

all kinds of flowers, and the grass

was about one foot high. Everyone was

surprised to have such a beautiful

vision of summer in this month.

Hereabouts, on the east side of the river,

there is supposed to be a settlement of

2-300 families, a little stretch

inland, though, because they do not like

to live right at the river for fear

of the Indians.21 At noon we left the

Ohio and entered the Muskingum.

This river is very deep a few miles from

its mouth, and paddles and oars

have to be used there; afterwards it is

not so deep any more,22 and a little

wider than the Lehigh at Bethlehem.

Today again a bear was shot.

The 23d. We left the lovely

countryside; the terrain became very moun-

tainous and the bottoms very swampy and

were almost completely covered

with beech trees.23 At

evening time our Brethren went on a little hunt

and again shot a bear.

The 24th. We met an Indian from

Gekelemukpechunk who was acquainted

with us. He was on his way home from the

hunt after he had shot a

buffalo, many of which are found around

here.24

The 25th. We traveled on till

noon, and since many complained of fatigue,

20 This

is the stretch of the Ohio popularly known as the Long Reach, between

Sardis (Monroe County, Ohio) and its

sharp bend about four miles south of Reno

(Washington County, Ohio).

21 It

has been impossible to identify this settlement, nor can the night camp for

April 21st be located. The distance

covered from Captina Island to the mouth of

the Muskingum, reached on April 22d,

about noon, was about 60 miles.

22 That indirectly indicates that in

less deep water the canoes were punted along

with poles. The night camp at the

Muskingum on April 22d was most likely at the

first slackwater place, near present-day

Lock 2, about 6 miles up the river from its

mouth.

23 This

description corresponds with the scenery along the river between present-

day Lock 2 and Lock 3, near Lowell,

where probably the night camp on the 23d

was made after a journey in a shallow

channel of only 7 1/2 miles. Even today beech

(Fagus grandifolia Ehrh.) occurs in these bottoms.

24 The stretch from Lowell (Lock 3) to

Beverly (Lock 4), the most probable site

of the night camp on April 24th, is

about ten miles long; the land, especially be-

tween Coal Run and Beverly, is flat on

both sides of the river-ideal buffalo country.

294 Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Quarterly

we resolved to make camp near a huge

rock.25 Some of the Brethren at once

built a sweating oven to sweat out their

fatigue;26 others went out hunting

a little and encountered buffaloes, at

which they shot, but without success.

This night we did not find much rest

because of the enormous number of

toads, which greatly annoyed us.27 The

Indians, therefore, call this place

25 The huge rock here mentioned, near

which, after only about eight miles' travel,

Heckewaelder's Indians made their night

camp of April 25th, was once situated on

the east bank of the Muskingum (which

here flows from south to north) about

halfway between present-day Luke Chute

Dam, near Swift, and Brokaw. The rock

was broken up and the fragments carried

a short stretch downstream to be used in the

construction of the dam. The remainder

was allegedly blasted off when, all along

the right bank of the lower Muskingum,

the Ohio and Little Kanawha spur of the

Baltimore & Ohio system was built. A

substantial chunk of the huge rock can

still be traced in the river, at its

original location, under about three feet of water.

Across the river from that spot there

used to be a settlement, Big Rock, which was

wiped out of existence by a river flood

after the Civil War; on a map of 1854 of the

state of Ohio the village of Big Rock is

still shown. I am greatly indebted for this in-

formation concerning the big rock to Mr.

Larry Semon of the Marietta Boat Club; to

Miss Louanna Walker of Marietta; and to

her parents, Mr. and Mrs. Clarence Walker

of Brokaw, Ohio.

26 The half-day journey of nearly eight

miles on April 25th between Beverly

and the big rock must have been

exceedingly strenuous; it is indicated by Hecke-

waelder's remark about their building

"a sweating oven to sweat out their fatigue."

27 In

the evening of April 25, 1952, under almost identical weather conditions,

this writer visited the area where, most

likely, Heckewaelder and his converts made

their night camp in 1773. It is roughly

the site of present-day Brokaw, where the

steep, rocky proclivity which closely

hugs the east bank of the Muskingum upstream

from Luke Chute Dam sufficiently recedes

from the river to make room for a camp near

the flats at Madison Run, which, coming

from the south, here empties into the

Muskingum. Especially after heavy rains,

such as had fallen on April 25th in both

1773 and 1952, these flats are very

soggy, with countless puddles and rills, making

an ideal spawning ground for toads and

frogs. The entire expanse, moreover, is

loosely covered with shrubby willows.

Except for the railroad dam that traverses

these flats from east to west at Brokaw,

close to, and almost parallel with, the

river, the swampy bottom appears not to

have been disturbed between 1773 and the

present day. Based on the supposition

that, therefore, its fauna likewise has re-

mained essentially unchanged, this

writer's expectations were fully borne out: starting

at twilight (about 7:30 P.M. E.S.T.),

and ever increasing in both shrillness and

volume as darkness deepened, there rose

from the swamp a batrachian chorus nothing

short of ear-splitting. Not a single

toad's typical call was heard, however; it was a

pure chorus of Hyla crucifera

crucifera Wied., the spring peeper, a tree frog, which,

by the way, is called a toad by the

people of the region. This misnomer confirms

my belief that Heckewaelder, at least in

the case at hand, likewise failed to dis-

criminate between "toad" and

"frog." It is certain that his Lenape converts did not

either, since their language has but one

word, tsquall, for both "toad" and "frog."

Another of this writer's observations in

the Madison Run flats seems to shed some

light on the nature of the annoyance

caused the campers of 1773 by that "enormous

number of toads": some of the

creatures, after but the briefest interruptions, con-

tinued their singing with the full glare

of a flashlight close upon them; yet, not

a single one could be seen. That makes

it evident that the sleep of the weary travelers

was disturbed solely by the noise; for

it seems out of the question that those par-

ticular frogs "annoyed" them

by hopping or crawling about the camp.

A

Travel Diary of John Heckewaelder 295

Tsquallutene, that means, town of the

toads.28 About midnight we had a

terrible thunderstorm accompanied by a

heavy rain. A part of our people

sought shelter beneath a rock which was

standing beside the huge one.

This big rock is 70 feet long, 25 high,

and 22 wide, and is solid rock.29

The 26th and 27th. The

channel was pretty good, and we advanced quite

a bit. But when we noticed that our

grain had been wetted by the last

rain and had started sprouting, we

resolved to travel on the 28th only as

far as Sikhewunk and dry our grain

there. Together with some of our

Brethren I went about ten miles up this

creek to see the famous salt spring,

which is imbedded in a sandbank, wells

heavily, and has no visible outlet;

evidently, it has an outlet underground,

because after having been emptied

it soon fills up again. We saw quite a

few contraptions there for boiling

salt.30 At the mouth of this

creek there is a very fine mount of anthracite

28 Tsquall-utene means 'a town of toads (or frogs)'; if it were supposed

to

mean 'a human settlement named after

toads, Toadtown,' the Lenape word would be

Tsquall-uten-unk (Lenape tsquall, 'frog; toad'; uten(e)-, 'town';

-unk, a suffix in-

dicating 'place where').

29 The measurements here given indicate

a rock of 38,500 cubic feet, large enough,

indeed, to attract the attention of both

Indians and whites.

30 According to Heckewaelder's Indian

Word List (History, page 440, where the

name reads Sikheunk), Sikhewunk means 'at the salt spring' (sikhe, 'salt'; -w-,

copulative; -unk, locative

suffix, 'place where'; literally: 'place where there is

salt'). It cannot have been the name of

the creek (which may have been

Sikhewihannok) but merely was that of the salt-boiling place on

"this creek,"

although Heckewaelder does not make it

very clear. There is multiple evidence that

"this creek" was Salt Creek,

mainly in Salt Creek Township, Muskingum County,

Ohio, the most conclusive of all being

Heckewaelder's remark in the next sentence

about a mount of rather pure coal at the

very mouth of "this creek." It little matters

that this coal is not Steinkohle, as

Heckewaelder calls it (which would be anthra-

cite), but, according to the special

maps of the regional carbon deposits, Middle

Kittanning (No. 6), which is the only

kind cropping out, at about water level,

at the mouth of Salt Creek. In view of

the fact that the entire region of Salt Creek

and its numerous branches and smaller

tributaries contained several salt licks and

springs, it must be noted that

Heckewaelder calls Sikhewunk the famous salt spring,

and that, to inspect it, he took a

special side-trip. This spring clearly was the main

source of the Indians' salt supply in

both the region and the period. The Schonbrunn

Diaries in the Moravian Archives,

Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, repeatedly tell of Indian

excursions to and from Sikhewunk. S. P.

Hildreth (Pioneer History [Cincinnati,

1848], 211, 260 et seq., 476)

greatly stresses the difficulties encountered by the

early Marietta settlers in obtaining

"culinary salt, . . . so necessary to the comfort

and health of the inhabitants." He

further relates that "white men, taken prisoners

by the Indians, had seen them make salt

at these springs [on "Salt creek, that falls

into the Muskingum river at Duncan's

falls"], and had noted their locality, so

that from their description a skillful

woodsman could find them [1796]." A salt-

boiling plant was erected, and began to

operate the same year, on the site of that

Indian salt spring, where eventually

Chandlersville was laid out. The preeminent

emphasis on this particular salt spring,

on the part of both the Indians and the

white settlers, makes it clear that it

was Sikhewunk, Heckewaelder's famous salt

spring, and that he was led by his

Indian guides, not up the north branch, named

296 Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Quarterly

coal;31 it lies there like a

wall of bricks, and not mixed with soil or other

stones, as I have seen it in other

places on the Ohio. This wall was 500

ells [1050 feet] long. Here another kind

of scenery begins, while up to

this point it had continued as

previously described. Now rich bottoms and

good land presented themselves, and the

farther we journeyed the more

pleasant did it become.32 The

river here took a different course, which

gave us hope to meet our Brethren soon,

because previously we seemed

to have traveled farther away from them

all the time.33

The 29th. We had to pass three

bad rapids, which gave us much trouble

because we had to tow up our canoes.34

The 30th. At noon we arrived at

the Shawnee Town which had been

visited by Brother David last fall.35

Some of our Brethren went into the

town, but they found only a few people

at home, who received them with

kindness; most of them had already moved

away. Thereafter we passed

Salt Creek on modern maps, but up the east

branch, which today is called Buffalo

Creek. The particular spot where, at

Chandlersville, Sikhewunk was situated has

been found by this writer in the Plats

and Surveys of U. S. Lands in the Auditor of

State's office at the state capitol,

Columbus (Vol. I [1798], Range 12, Twp. 13,

Section 13). The location, clearly

marked "Salt Spring," is drawn in at a point on

Buffalo Creek where Lepage Run comes in

from the south, that is, at present-day

Chandlersville. That here we have

Sikhewunk is further confirmed by the fact that

the survey plat shows the Salt Spring at

the crossing point of several early pioneer

roads, likewise drawn in, which clearly

follow aboriginal trails that converged in

the same important spot: Sikhewunk. Evidently, the

distance given by Heckewaelder

of "about ten miles up this

creek," from the mouth of Salt Creek to Sikhewunk, was

estimated rather than measured; by

today's county road, probably likewise an Indian

trail, through Blue Rock State Forest,

the measured distance from Chandlersville to

the mouth of Salt Creek is 7.1 miles,

although the original trail through the woods, in

1773, may have been a mile or two

longer.

31 See preceding note.

32 This description perfectly fits the

scenery about, and north of, Duncan Falls.

33 The general direction of their

journey so far could indeed give them the im-

pression that they had been traveling away

from their destination--the mission of

Schonbrunn--rather than towards it:

first, on the Beaver and Ohio rivers, going south

and southwest; then, from the mouth of

the Muskingum, following the tortuous

course of that river as far as Salt

Creek. From there on only did they begin to

feel that they were actually bound for

their destination.

34 The fact that they had to pass these

rapids shortly after having broken camp

at the mouth of "this creek"

on the 29th, is indirect evidence (1) that "this creek"

indeed was Salt Creek, Muskingum County;

and (2) that the "three bad rapids"

were Duncan Falls, as they were named

not long afterwards; the rapids retained

this name "until the slack-water

improvement on the Muskingum obliterated the

rapid at this place." Hildreth, Pioneer

History, 221. It evidently took them the whole

day to haul their twenty-two canoes over

the falls; their total progress on the 29th

was about 1 mile.

35 This was Woaketammeki, a Shawnee town

on the Muskingum on the site of

present-day Dresden. According to the

Schonbrunn Diaries, Zeisberger's visit had taken

place on October 13-15, 1772.

A

Travel Diary of John Heckewaelder 297

another [Shawnee] town, and made camp.36

Today we had a stretch of

bad channel, and most of the men became

very much fagged out.

The 1st of May, at noon, we

rested again close to a Shawnee town. The

inhabitants of this town moved about

among our people and showed

friendly feelings for us. Meanwhile I

visited a white man who is living

there and who has a white wife; she had

been a prisoner and cannot talk

anything but Shawnee. After that we

journeyed on and were received

very kindly in a town where Delaware and

Monsey are living; they showed

us great hospitality and were not

satisfied until we all had eaten enough.

They would have liked us to stay with

them for the night, but as we did

not want to lose any time, we traveled

on for a few more miles.

The 2d. We had to wade again in

the water a great deal, towing our

canoes over rapids and shallow places.

We met an Indian Brother from

Gnadenhutten, who lent us considerable

help.

The 3d. We again passed different

towns, stopped at some and talked

with the inhabitants, who showed

themselves friendly toward us, and in

the afternoon we passed Gekelemukpechunk

and made camp at the upper

end of the town.37 Passing

by, I counted 106 spectators. They greeted us

with their usual shout of joy, but we

were not able to thank them in the

same way. No sooner had we gone ashore

than we had visitors, some of

whom brought food for the hungry.

Meanwhile I went with a few Brethren

to visit Chief Netawatwes.38 He,

as well as others who were with him,

was very friendly toward us, and when we

parted I had this feeling about

him: "You, too, will be of the

Savior's, some day." Then I and another

36 These smaller Shawnee towns near

Woaketammeki are also mentioned in

Zeisberger's travel report in the

Schonbrunn Diaries. Heckewaelder's progress during

the 30th was approximately 30 miles.

37 The

total stretch covered from May 1st until the afternoon of May 3d roughly

corresponds to the course of the

Muskingum and Tuscarawas between a

point

about 3 miles above present-day Dresden

and Newcomerstown (Gekelemukpechunk);

it is about 31 miles long.

38 Netawatwes, near his ninetieth year

in 1773, had been chosen chief of the

Turtle Tribe (Unami) in his early

manhood, while the Lenape nation was still

in eastern Pennsylvania in the basin of

the Delaware River (Lenapewihannok).

Since the Unami were the foremost tribe

of the nation, its chief was regarded, and

respected, as the great chief of the

entire Lenape people; the whites called him

"King" Netawatwes. Although

occasionally wavering in times of political high

tension, he advocated friendly relations

with the colonists and, in particular, with

the Moravian missionaries Zeisberger and

his fellow-workers and strongly advised

his nation to adopt the Moravian faith

and ethics. At the time of his death he may

be safely called a Christian, although

he did not formally join the Moravian

Brotherhood by being baptized. One of

his grandsons, however, still in the old

man's lifetime, became the first member

of the newly founded Moravian Indian

congregation of Lichtenau in 1776.

298 Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Quarterly

Brother went to see Killbuck, who, among

other things, asked the Brother

who was with me: "Does this man

really like the Indians?"39 -- "Yes," he

answered, "not only does he like

them, but all the other Brethren who are

with us like them, too. It would not be

necessary for them to live as poorly

as they do; I have seen with my own eyes

how well they live at Bethlehem;

but because they like the Indians, and

want to acquaint them with the

Savior, they are content with their poor

mode of life and are happy when the

Indians become believers in the Savior.

There is nothing else they ask or

demand of us." - He replied:

"Well, well, now I know it."

The 4th. In the morning we again

had many visitors, and our Brethren

every once in a while said a word or two

about the Savior. Then we parted

again. A few Brethren from Gnadenhutten

and Welhik Thuppeek, who

met us halfway, were very welcome to us,

because by now we were all en-

tirely spent. In the afternoon we

arrived at Gnadenhutten, where everybody

had been looking forward to our arrival

and had been busy preparing

food in order that the hungry and weak

might restore themselves. Three

families at once stayed there to live,

and the rest of us, on the 5th, arrived

happily and safely at Welhik Thuppeek,

where we were received by our

Brethren and Sisters in the most

affectionate and loving fashion.40

39 Killbuck's question bears witness to

the deep-seated distrust this son of Chief

Netawatwes harbored against the

Moravians, as he did indeed against all whites.

Killbuck subsequently added to the

worries of both his father and the mission by

heading an anti-white party in the

capital and openly opposing Netawatwes' pro-

Christian peace policy.

40 The final stretch from

Gekelemukpechunk (Newcomerstown) to Schonbrunn,

covered on May 4th and 5th, was about 24

miles. The total distance of 335 miles

was traveled by Heckewaelder and his

Indian converts in twenty-three days (April

13-May 5, 1773), none of which was an

entire rest day. That amounts to a daily

average of slightly over 14 1/2

miles.

A CANOE JOURNEY FROM THE BIG BEAVER TO

THE

TUSCARAWAS IN 1773: A TRAVEL DIARY OF

JOHN HECKEWAELDER

Translated and edited by AUGUST C. MAHR

Professor of German, Ohio State

University

By 1772, due to circumstances beyond

their control, the

missionaries of the Moravian Church

among the Indians in Penn-

sylvania had found it inevitable to

abandon their two mission

stations on the upper North Branch of

the Susquehanna: Friedens-

hiitten, about one mile down the river

from present-day Wyalusing,

and Schechschequanniink (present-day

Sheshequin), about twenty-

five river-miles upstream from

Friedenshiitten.1

Between June 11 and the middle of

August 1772, a total number of

over two hundred Indian converts of the

Susquehanna mission,

under the leadership of the two

Moravian missionaries, the Rev.

Johannes Ettwein and the Rev. Johannes

Roth, migrated, partly

by water, and partly by land, from the

Susquehanna to the Big

Beaver, where the Rev. David Zeisberger

had founded, in 1770,

a new mission station among the Monsey.

The Monsey consti-

tuted the Wolf Tribe of the Lenni

Lenape, or Delaware, Indian

nation. The two other tribes were the

Unami (Turtle Tribe) and

the Unalachtigo (Turkey Tribe). Since

the beginning of the 1720's,

practically the entire Lenni Lenape

nation had gradually left its

old hunting grounds in eastern

Pennsylvania, migrating into the

Ohio basin, where the majority, the

Unami and Unalachtigo, had

settled in what today is the eastern

half of the state of Ohio,

while the Monsey established themselves

in northwestern Penn-

sylvania on the Allegheny, Big and

Little Beaver, and Mahoning

rivers.

Apart from the negative reasons for the

abandonment of the

1 A comprehensive account of the labors

of the Moravian Church in the Indian

mission field of North America in the

eighteenth century can be found in Bishop

Edmund deSchweinitz' excellent biography

of that church's greatest missioner among

the Indians, entitled The Life and

Times of David Zeisberger (Philadelphia, 1870).

The book also contains brief biographies

of the other Moravians mentioned in the

present pages: Ettwein, Roth, and, last,

but not least, John Heckewaelder.

283

(614) 297-2300