Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

|

|

|

The Civil War had been fought out and peace had returned to the land when a group of churchmen and reformers led by the Rev. Charles G. Finney of Oberlin, who had long served as president of Oberlin College, turned to make war on secret societies and the Masonic order in particular. The crusade mildly agitated a part of the country for some years, but lacking as it did the frenzy, hysteria, and political potency of the anti-Masonic move- ment of the 1820's and 1830's it eventually fell of its own weight.1 The persistent crusaders in the Finney camp were fond of referring to recusant Masons as proof that the principles of the order were repugnant to thinking Christian men--that they renounced the order once its secrets and NOTES ARE ON PACES 78-79 |

JOHN BROWN AND THE MASONIC ORDER 25

its binding oaths had been made known to

them. John Brown, the firebrand

of Kansas and the raider at Harpers

Ferry, was among those mentioned

whose religious principles impelled them

to leave the order and to become

bitter enemies of all secret societies.

But proof of John Brown's affiliation

was lacking--those who knew the

circumstances were not talking. In the

face of strong denials of such membership

by Masons who knew as little

about the truth of the matter as did the

anti-Masonic advocates, his name was

dropped. The dispute, however, was not

settled.

Was John Brown a Mason? Some argued that

he was; others claimed that

he was not. Members of the family

remained silent. It took a long time for

the record to become clear.

The long dispute as to whether John

Brown was a regularly initiated

Mason and a member of a lodge operating

under proper authority was

definitely settled only a few years ago

when the records of the old, disbanded

Hudson Lodge No. 68 were uncovered in

the archives of the Grand Lodge

of Ohio. There it was found that Brown's

membership was fully established,

with dates of initiation and, further,

his election to an office in the lodge.2

His record as an opponent of secret

societies--with Masonry as his chief

target--had been no secret, though he

had nothing to say about the subject

in his later years. Behind the brief

notes in the old lodge record is a story

that has never been fully told.

It was not until 1881, when Mrs. Brown

in a newspaper interview casually

mentioned that her husband had once been

a Mason, that the argument was

renewed.3 Again there was

quick denial by Masons who were zealous to

protect the good name of their order

against aspersions of association with

a character as controversial as John

Brown. Apparently, save for the sur-

viving members of the family, there were

none to defend John Brown--the

friends who had known him as a Mason

some fifty years earlier had either

passed from these worldly scenes, or did

not want to add fuel to the flames

of controversy, or perhaps withheld

their knowledge of his membership and

his later renunciation of Freemasonry as

a lodge secret. Brown himself had

little or nothing to say about his

Masonic record and, if one of his associates

is to be believed, even wanted to

conceal his anti-Masonic activities from his

associates in the later days of his

life.4 Thus the incidents surrounding his

renunciation and activity as an

anti-Mason have been generally blurred by

inaccurate and misleading statements

made by members of his family, and

by anti-Masons who wanted to use his

change of attitude for propaganda

purposes.

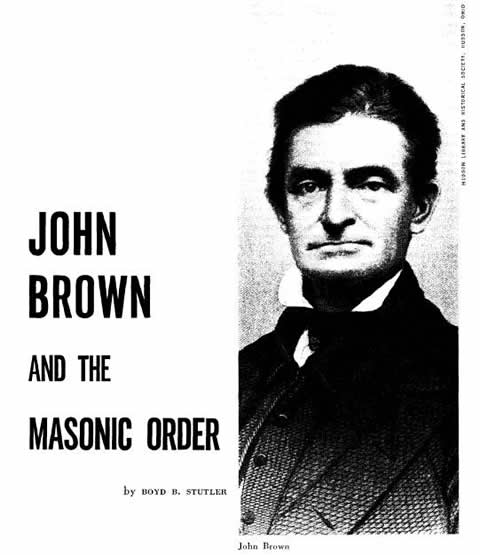

John Brown, who is yet one of the most

controversial characters in Ameri-

can history, was born at Torrington,

Connecticut, on May 9, 1800, but in

26 OHIO HISTORY

1805 was taken by his parents to the

then frontier town of Hudson, Ohio,

where he was reared. The Western Reserve

was then being settled largely

by emigrants from New England, and

Hudson was one of its newer towns-

in all respects a New England village

pulled up by its roots and transplanted

in Ohio. Members of the Masonic

fraternity who had been made master

masons in lodges in their old home towns

were among the settlers, but it

was not until January 26, 1823, that

Hudson Lodge No. 68 was constituted.5

The first worshipful master was Gideon

Mills, Jr., who was an uncle of John

Brown--it may have been the influence of

this uncle, or it may have been

his own curiosity to see what this

secret order was all about that caused him

to apply for membership. At any rate,

his application was filed in late 1823,

and after the usual course of

investigation and waiting he was found worthy.

The records of the old lodge disclose

that he appeared and received the

entered apprentice degree on January 13,

1824, and on February 10 received

the fellow craft degree. After a lapse

of three months he was raised to master

mason on May 11.6 His attitude at that

time must have been in all ways

satisfactory to members of the craft,

for he was elected junior deacon for the

1825-26 term--and he was holding that

office, whether actively serving or

not, when in May 1826 he hastily pulled

up stakes and moved to Crawford

County, Pennsylvania, relinquishing a

prosperous tanning business in his

old home town.

It has been claimed by a son that he was

hounded out of his native town

because of his renunciation of

Freemasonry,7 but the facts so far as dis-

covered seem to prove otherwise. Young

John Brown, then twenty-six years

old and with a rapidly increasing

family, saw better opportunities in the

newer settlements near Meadville,

Pennsylvania, and, in addition, he had

formed a partnership with a kinsman,

Seth Thompson of Hartford, Trumbull

County, Ohio, to go into tanning and

cattle dealing on a very extensive scale.

All evidence found strongly indicates

that he did not break with the Masons

until the anti-Masonic hysteria was

fanned into a national frenzy. At that

time he was comfortably settled on his

farm at Randolph, twelve miles east

of Meadville, Pennsylvania, with an

adequate acreage cleared, his tannery

constructed, and hides in the vats.

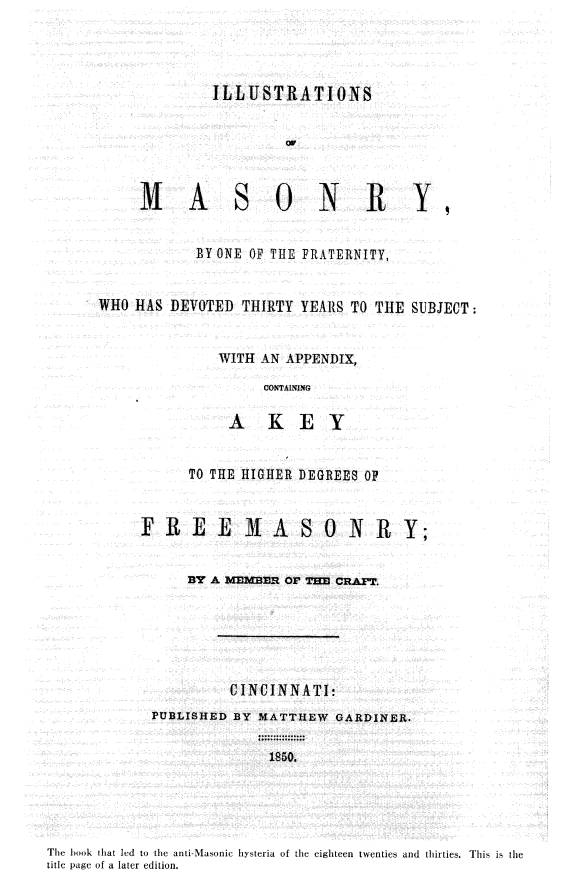

The anti-Masonic frenzy was touched off

by the reported abduction and

murder of William Morgan at Batavia, New

York, in September 1826.8

Morgan, himself a member of the craft,

had published a book, Illustrations

of Masonry, which was designed to expose the order as subversive of

Ameri-

can democracy--the work itself was

poorly done and would probably have

soon been forgotten had it not been for

the violent methods resorted to by

28 OHIO HISTORY

zealous members to suppress it. The

office in which it was printed was

burned, and Morgan, after his release

from imprisonment for a small debt,

was abducted and was presumed to have

been killed. The incident was

seized upon by reformers, church groups,

opportunist politicians, and dissi-

dent Masons and was quickly fanned into

a national issue based on principle,

prejudice, and hysteria. Led by political

herdsmen--such as Thurlow Weed

in New York and Thaddeus Stevens in

Pennsylvania--the Anti-Masonic

political party was hastily formed and

until 1836 offered a serious threat

to the balance of political power in New

England and the upper tier of

northern states. As the first

"third party" in American political history,

the Anti-Masons offered William Wirt of

Maryland as their candidate for

president in 1832--he polled a heavy

popular vote and won the seven elec-

toral votes of Vermont. Pennsylvania and

Vermont elected Anti-Masonic

governors, and the party won many other

state and local offices. It thrived

in New York, where it once achieved a

position as second in voting strength.9

The crusade precipitated a crisis in

Masonic affairs. In New York, for

instance, the membership dwindled from

20,000 in 1826 to 3,000 in 1836,

and the number of lodges was reduced

from 507 in 1826 to 48 active units

in 1832.10

The prevailing sentiment in Crawford

County, Pennsylvania, was anti-

Masonic, and the political party under

that name carried the county re-

peatedly. John Brown renounced his

membership and roundly denounced

the order--he was with the majority this

time, something strange for him,

and it seems likely that the threats of

personal injury mentioned by members

of his family were largely magnified in

repetition. An active, working lodge

was located in Meadville--Western Star

Lodge No. 146, constituted on

August 15, 1816--and certainly the order

had some friends in that area.

But the lodge was not strong enough to

withstand the assaults of the opposi-

tion; it ceased its labors in 1828, but

the charter was not actually vacated

until 1837.11

In an interview given a reporter in

1895, a short time before his death,

John Brown, Jr. (himself a Mason,

1859-95, and buried with Masonic

honors), said: "Father denounced

the murder of Morgan in the hottest kind

of terms.... Father had occasion to go

to Meadville. A mob bent on lynching

him surrounded the hotel, but Landlord

Smith enabled him to escape through

a back entrance."12 Owen Brown,

another son, said in 1886 that his father

"was active in the anti-Masonic

campaigns at that time, circulating Giddins'

Anti-Masonic Almanac, but so high was the excitement and so loud the

threats that he kept a pistol and

keen-edged knives in his house for self-

protection."13

JOHN BROWN AND THE MASONIC ORDER 29

Owen was interviewed by Henry L.

Kellogg, an editor of the Christian

Cynosure--one of the last religious papers devoted to

anti-Masonry--and the

story as it appeared in that publication

was probably colored or slanted to

meet the editorial policy. Another

statement in that interview was that the

senior Brown's "detestation of

lodge literature was shown by the fact that

Owen once found the by-laws of the

order in a swill barrel where his father

had thrown them." Owen was born

late in 1824, and if it is presumed that

Brown disposed of his lodge papers

within two or three years after severing

his membership, it seems hardly likely

that a three- to five-year-old child

would retain a clear memory of such a

minor incident.

Still another explanation was given by

a daughter, Sarah Brown, in 1908,

when she was interviewed by Katherine

Mayo, who was then doing field re-

search work for Oswald Garrison

Villard's monumental biography of John

Brown. Said she: "John Brown was

deeply opposed to all forms, even in

church. He did not like formal worship.

It was the forms of the initiatory

ceremonies of the Masons that struck

him as silly and disgusted him. He was

in sympathy with Morgan. He bought

Morgan's book--and it was in the

North Elba house for years."14 But

Sarah, like Owen, had no first-hand

knowledge--she was not born until 1846.

Henry Thompson, a son-in-law who was in

the Kansas wars with Brown,

was more forthright and just as

inaccurate. "When Morgan's pamphlet came

out it made a great sensation among the

Masons. I got it. Captain Brown

saw it in my house, took his pencil and

wrote across the back of it, 'This story

could not be better told.' But he never

uttered a word concerning it. . . . I

was asked to join the Masons myself

later, but always refused. Captain

Brown's verdict was good enough for

me."15

John Brown himself did not dwell on this

incident in his life--in fact in

later life he wanted to suppress

knowledge of it.16 So far as found the only

written statement about his

anti-Masonic activities is in a letter to his father,

which was written at Randolph on June

12, 1830:

You mention some difficulty in the

church arising out of Masonry. I wish you

would at some leisure moment give me a

little history of it. I hope the church in

regard to that subject will pursue a

mild but persevering & firm course, not

undertaking with any unmanageable

point, but such as may undergo easy general

& thorough investigation. I make no

doubt that some of the Masonic brethren

yet think their oaths binding as much as

Herod the Tetrarch did his to the

daughter of Herodias. I have aroused

such a feeling toward me in Meadville

by shewing Anderton's statement as leads

me for the present to avoid going about

the streets at evening & alone. I

have discovered that my movements are narrowly

watched by some of the worthy

brotherhood. This I ought to consider as right

30 OHIO HISTORY

according to the views of some

distinguished professors of religion at Hudson

who are of their own craft. Some of them

have said to me that the courts of

justice have no right to compel a mason

to testify anything about masonry, of

course they are above the laws of the

land. Some of them I suppose intend

pleading to the jurisdiction of the

great Supreme, at least their actions say who

is Lord over us.17

The reference to "Anderton's

statement" in the letter is easily understood;

it refers to a sworn statement made by

Samuel C. Anderton of Boston, Mas-

sachusetts--a recusant Mason--that he

had been chosen by lot one of three

members in a lodge at Belfast, Ireland,

to cut the throat of a brother member

who had revealed some of the secrets of

the order. This statement was widely

published in the anti-Masonic press,

including the Crawford Messenger at

Meadville, which Brown probably read

every week.18 But as the lodge at

Hudson was disbanded in 1828, the

reference to an investigation by the

church two years later is a bit obscure.

Later, in 1847, when he wrote a series

of parable-like articles for the

Ram's Horn, a paper published by Negroes in New York City, he

expressed

dislike for secret societies in general

in some words of advice to the colored

people. The series was titled

"Sambo's Mistakes." In looking back over

his past life, "Sambo"

discovers that "another of the few errors of my life

is that I have joined the Free Masons[,]

Odd Fellows[,] Sons of Temper-

ance, & a score of other secret

societies instead of seeking the company of

intelligent[,] wise & good men from

whom I might have learned much that

would be interesting, instructive, &

useful & have in that way squandered a

great amount of most precious time &

money."19

That is mild enough, but it strongly

indicates that Brown retained his

dislike and opposition to secret

societies as he verged into middle age. Not-

withstanding his attitude, two of his

sons, John, Jr., and Salmon, were re-

ceived into the order, while a third

son, Owen, apparently adopted the views

of his father. John, Jr., was raised in

Jerusalem Lodge No. 19 at Hartford,

Ohio, less than a month before the raid

at Harpers Ferry. And the fact that

some of Brown's men looked kindly on

Masonry indicates that the militant

leader became more interested in the

anti-slavery crusade than in contesting

with secret societies. Francis J.

Meriam, one of the men who escaped from

Harpers Ferry, was inducted into the

order within a few months after the

execution of his commander.

According to George B. Gill, who was one

of Brown's men in Kansas,

Brown became angry when he found that

Owen had mentioned to Gill that

his father had once been a Mason, but

had renounced the order. "He was

vexed when he found that Owen had told

me of his troubles with the Masons,"

JOHN BROWN AND THE MASONIC ORDER 31

said Gill. "Owen should not have

done that," said Brown. "Never tell it.

Some of our friends back East are

Masons. If they ever hear of it they might

not like it--and might refuse further

help. Never tell it." 20

Another sidelight of the Kansas campaign

is a story, which is most prob-

ably apocryphal, that in the course of

the Pottawatomie massacre on the

night of May 24, 1856, when Brown with a

small company called five pro-

slavery men from their homes and hacked

them down with short swords,

Brown sent his son-in-law Henry Thompson

and Theodore Wiener to kill

Allen Wilkinson. It is said that

Wilkinson was a Mason and that Brown

remained at a distance from the scene of

summary execution. The story is

in part supported by the admission of

Salmon Brown, who was with the

party, that Thompson and Wiener did kill

Wilkinson.21

As it was not generally known in Kansas

that Brown had once been a

Mason, it seems very probable that the

Wilkinson story came about as an

afterthought, as did many other tales

relating to John Brown and his works

in Kansas Territory.

More authentic is the fact that Brown

did not hesitate to use the cloak of

Freemasonry to conceal the purpose of

his convention at Chatham, Canada,

on May 8-10, 1858, when to account for

the presence of so many strangers,

white and Negro, in the small town he

caused word to be spread that he was

there to organize a lodge of colored

Masons.22

Less susceptible of proof--and less

creditable if true--is the story widely

circulated and just as widely believed

that John Brown solicited (and re-

ceived) aid from the lodge at

Clarksburg, West Virginia, in early August

1859, under pretense of being a Mason in

good standing. The story was told

by John J. Davis, father of John W.

Davis, the Democratic nominee for

president in 1924, to whom the

application was made.23 Mr. Davis examined

the stranger, whom he described as

having a long, flowing beard, and the

answers to his queries left no grounds

for suspicion that the man was an im-

postor, but on the contrary gave Mr.

Davis every reason to believe that he

was a Mason in good standing. Mr. Davis

then took the stranger to William

P. Cooper and Charles Lewis, both

prominent Clarksburg citizens, who were

members of the committee appointed by

the lodge to care for such matters.

On the recommendation of Mr. Davis the

stranger was given $20 to help him

on his way to Martinsburg.

After the raid at Harpers Ferry, Mr. Davis

and the two committee members

identified the brother they had

befriended as John Brown, the identification

being based on a picture published in Leslie's

Weekly. And that is one of the

strongest points that serve to cast

serious doubt on the correctness of the

identification.

32 OHIO HISTORY

The portrait in Leslie's was

reproduced from a photograph made in Boston

in May 1859, when Brown wore a long

beard. But, just after the photograph

was taken and before his arrival at

Harpers Ferry, he visited his home at

North Elba, New York, and while there

had his hair and beard closely

trimmed. The date of the supposed visit

to Clarksburg is definitely fixed as

the day on which a colored woman Charlotte

Harris, was on trial for aiding

slaves to escape. This was August 1,

1859.24 If Brown was there as an on-

looker at the trial, as he is claimed to

have been, his beard would have been

a short, bristly stubble of not more

than two or three inches in length.

It is not possible to pinpoint Brown's

exact whereabouts on August 1, but

on July 27 he was at Chambersburg,

Pennsylvania, and was at that place

again on August 2. He could have

traveled by rail from Harpers Ferry to

Clarksburg, but another witness who

claimed to have observed him in the

courtroom, says that he rode his horse

in company with the stranger to

Shinnston, some ten miles distant and

away from the railroad line to

Martinsburg, after the court proceedings

had been concluded.25

It seems very unlikely that the

impostor, if he was an impostor, was John

Brown. No doubt it was a case of

mistaken identity such as occurred in a

number of other instances where error

could be easily established, though

Mr. Davis, whose honesty, sincerity, and

truthfulness cannot be questioned,

believed to his dying day that he had

been instrumental in rendering Masonic

aid to the Harpers Ferry raider.

When John Brown came to the end of the

road on the gallows at Charles

Town, he could have no good claim on the

tender sympathies of the brother-

hood in America--it remained for the

Freemasons of France to pay the

final fraternal tribute. That tribute,

it may be said, was not paid to him

because of any pretense to Masonic

membership, but in sympathy for the

man who had dared to declare a one-man

war on the institution of human

slavery. It was at the solstitial winter

feast in the lodge of St. Vincent-de-

Paul in Paris on January 6, 1860, that

M. Ulbach, orator, paid a glowing

tribute to the memory of John Brown, and

offered a toast to him and his

work.26

THE AUTHOR: Boyd B. Stutler is the man-

aging editor of the West Virginia

Encyclopedia.

A noted collector of Browniana, he was

chair-

man of the John Brown Centennial

Commission

of West Virginia in 1958-59.

|

|

|

The Civil War had been fought out and peace had returned to the land when a group of churchmen and reformers led by the Rev. Charles G. Finney of Oberlin, who had long served as president of Oberlin College, turned to make war on secret societies and the Masonic order in particular. The crusade mildly agitated a part of the country for some years, but lacking as it did the frenzy, hysteria, and political potency of the anti-Masonic move- ment of the 1820's and 1830's it eventually fell of its own weight.1 The persistent crusaders in the Finney camp were fond of referring to recusant Masons as proof that the principles of the order were repugnant to thinking Christian men--that they renounced the order once its secrets and NOTES ARE ON PACES 78-79 |

(614) 297-2300