Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

|

COLLECTIONS AND EXHIBITS REMBRANDT and |

|

|

THE OHIO HISTORICAL SOCIETY by WILLIAM C. KEENER |

|

A FEW MONTHS ago the Metropolitan Museum of Art shocked the public, and certainly surprised the museum world, by paying the remarkable sum of $2,300,000 for Rembrandt's painting of "Aristotle Contemplating the Bust of Homer." It was an historic occasion and one filled with more than its share of drama. So- cialites, art dealers, critics, collectors, and museum people gathered for the sale in the austerely furnished main auction room at Parke - Bernet Galleries, New York, while less fortunate ticket holders were dispersed to nearby quarters and forced to participate via closed-circuit television. Not a few prominent and no- ticeably irate public figures were turned away. Excitement ran high, for although other fine paintings were to be sold, the Rembrandt commanded the attention-- and aroused the speculation--of every person present. Parke-Bernet auctions are especially |

|

well managed and move very quickly. Tension mounted steadily as the monoto- nous voice of the auctioneer droned the opening bid on the "Aristotle" -- one million dollars. Raised hands or subtle nods and other obscure bidding devices rapidly raised the price to the successful pinnacle, the highest price ever paid for a painting. In the weeks that followed, conscienti- ous reporters solicited opinions on this amazing purchase from all classes of peo- ple from cab drivers to bank presidents, and many thousands who had never set foot in a museum trekked to the Metro- politan to contemplate "Aristotle." For many it was the greatest painting they had ever seen; it evoked an emotional and aesthetic response of unequaled mag- nitude. But to almost everyone who saw it or read about it, it posed two nagging questions--why did it cost so much, and why did the museum buy it? |

|

58 OHIO HISTORY |

|

It is not our purpose here to discuss the Rembrandt's uniqueness, quality, or aesthetic appeal, nor the wisdom of the Metropolitan Museum's decision to buy the picture. But this single event that so effectively captured the imagination of the public, also focuses attention on those two legitimate questions that go to the heart of museum and historical society acquisition policies. They are the ques- tions that any curator must ponder as he considers an object for acquisition. He does so, however, with a conception of the museum's purpose that is often much different from that of the casual visitor. The first question is easier to answer, or, perhaps, to understand, than the sec- ond. At the same time that the American people have become increasingly appre- ciative of the past, their affluence has encouraged competition in the acquisition of those objects that represent significant expressions of the cultural heritage of their civilization. As a result of this ri- valry, which is dominated primarily by private collectors and certain museums, the prices of the rare and distinctive pieces of times gone by have risen sharply, sometimes, it seems, as in the case of the Rembrandt painting, to fan- tastic heights. The fact is that many of the relics of former periods, such as art objects, household furnishings, orna- ments, textiles, tools and implements, publications, and manuscripts, have mone- tary value. The museum that would ac- quire any of them must pay for them or receive them by gift, and if they are given, the donor may be credited with their monetary value. The answer to the second question is involved with the very purpose of the institution known as the museum. Con- trary to a still widely held opinion, mu- seums are not, or should not be, large, dusty depositories for curios. The modern museum serves many masters and many causes. It must accommodate the needs |

|

of the scholar, the student, the collector, the casual visitor--and posterity. Each of these groups, and others, requires par- ticular attention, and it is the duty, indeed the obligation, of the institution to develop its collections so that all may be served. Obviously, the purpose of the collecting program of a museum must be somewhat broader than the aims of the private collector. He can indulge a serious inter- est, a whim, or an idiosyncrasy to the extent of his needs or of his wealth. His responsibility is only to himself. This is not to say that many great private col- lections have not been formed, but to point out that the private individual has no obligation to develop his collection to meet any requirements other than his own. The museum, on the other hand, must consider its acquisitions, both indi- vidually and collectively, in terms of pub- lic or general use. An object, whether it is a Rembrandt painting or a stoneware crock, has a va- riety of uses in a museum collection. First, and perhaps most important, the museum item is a fact; it is a physical document of a moment, of a taste, of a craft or an industry, of a culture, and of an age. It can be used, much as a manu- script is used, as historical evidence. Fre- quently, the object is the only form of evidence that sheds light on a particular facet of social or cultural history, or, when used in conjunction with other types of documentation, it provides a broader understanding of a particular subject under consideration. Archaeolo- gists have long understood and made effective use of artifacts as documents, and some modern historians have devel- oped a similar appreciation in recent years. In the same context, a group of like or related objects can prove even more use- ful in developing documentation in depth. Just as a diary or collection of letters |

|

COLLECTIONS AND EXHIBITS 59 |

|

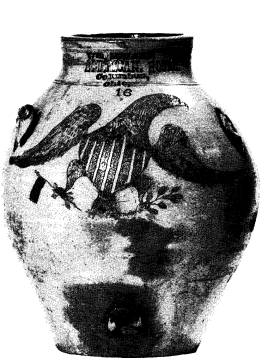

provides a deeper insight than a single document into the thoughts and actions of an individual, so also a collection of fire- arms, for example, gives a clearer view than a single weapon of the development of the military, protective, and hunting techniques and abilities of a given his- torical period. The object is presented to the public generally, however, as an interpretive piece in a museum's exhibition. Here the full impact of its aesthetic and visual ap- peal can be combined with its documen- tary qualities to illustrate a particular point or to delineate a whole culture. Its exhibition is the ultimate moment of truth for the object, for here, transported through time to the present, it speaks of its own environment, of the events in which it participated, and, to some extent, of the men who made and used it. The degree to which it is successful in com- municating its message depends upon the merit of the object and upon the ability of the museum to display it. The acquisition program of the Ohio Historical Society is based upon its obli- gation to fulfill these needs of preserving documentation of our culture and, through the documentation, of interpret- ing our past. Each object considered for the historical collections, therefore, is evaluated in terms of its significance as a document, its intrinsic merits, its impor- tance to the collections, and its value to the Society's exhibition programs. The object, to be acceptable, must also meet high standards of quality and condition. The large stoneware crock pictured on the cover provides an excellent illustra- tion of these considerations for acquisi- tion in practice. It is not difficult to visualize this massive container gracing the premises of the American House in Columbus during the mid-1840's, nor does a finer means exist for helping to develop an understanding of the early pottery craft in the Ohio Valley. Its pro- |

|

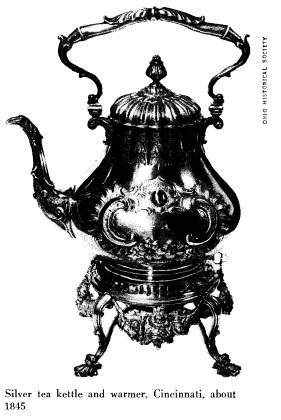

venience is well authenticated by marks impressed on the body. In form and dec- oration it is one of the finest examples of stoneware in existence. This piece is also a desirable addition to the Society's ex- tensive collection of salt-glazed stoneware, and it clearly shows the development of the technique of scratched or incised dec- oration. Finally, it can be utilized in a variety of exhibitions. It is apparent, in this instance, because of its singularity, that the significance and quality of this object override its defective condition. The fact that the handles of this unique crock are broken and missing does not detract from its ability to fill all of the acquisition requirements. Another recent addition of consider- able importance to the Society's collec- tions is the silver tea kettle and warmer illustrated here. It was made and sold by |

|

|

|

|

Edward and David Kinsey of Cincinnati about 1845 and is one of the few extant marked hollow pieces of Ohio silver. The Kinseys were active separately and in partnership for several decades before the Civil War and were perhaps the most prolific silversmiths in the state. Their work on this particular piece can hardly be judged by comparison with that of the great American silversmiths of the eigh- teenth century, but within the context of its period, it excels in craftsmanship and restrained ornamentation, not often found in the early Victorian years. It is an im- portant document, not only of the craft of silversmithing but also of the taste and furnishings of its period as well. While the significance of a single ob- ject is sometimes difficult to appreciate, it generally takes on added meaning when it is viewed along with similar objects and also with objects made from the same ma- terial or by the same method. One of the goals of the museum is to build collec- tions of comparable objects in order to achieve an understanding of the whole production of a particular category. On occasion a museum finds itself in a for- tunate position to acquire a large group of similar or comparable materials for its collections at one time. Usually these are selected from a major private collection that has been assembled by an informed and discerning collector over a period of years. Recently the Ohio Historical So- ciety was privileged to make a selection of more than 350 pieces of American |

|

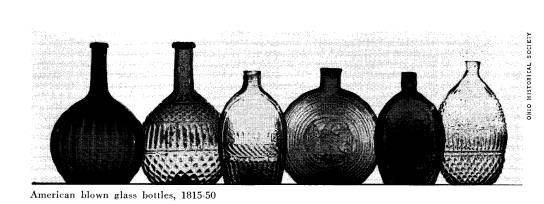

blown glass and blown molded glass from the collection formed by the late George S. McKearin, an eminent collector of early American glass and an authority on that subject. This acquisition swelled the Society's holdings in this important field to approximately one thousand items. This fine collection helps to document the historical impact of glassmaking on the economy of the state and on the con- sumer habits of its citizens. As early as 1815 a small factory in the Zanesville area was producing bottles, tableware, and window glass for local consumption, and within a few years similar enterprises sprang up at Kent, Ravenna, Mantua, and Cincinnati. Calling upon experienced craftsmen who had been trained in the East and in the flourishing Pittsburgh factories, the Ohio firms maintained the production of a steady stream of blown- glass tableware and containers through- out the first half of the nineteenth cen- tury. With the discovery of glass-pressing techniques, an even greater volume of production literally swamped the glass market after mid-century. On this page is a picture showing sev- eral examples from the collection. At the left is an amber, broken-swirl globular bottle, typical of thousands that were made between 1815 and 1830 as contain- ers for spirits and a variety of household liquids. Beside it are two blown three- mold pieces--a bar bottle and a flask-- which were made at Kent during the rage for this type of imitation of the more ex- |

|

COLLECTIONS AND EXHIBITS 61 |

|

pensive cut glass. One hundred and twelve patterns and fifteen colors produced by this remarkable technique are represented in the collection. Flanking these pieces on the right are three of the historical, or figured, flasks that became so popular in the 1830's and 40's. The concentric-ring eagle flask is one of today's great rarities among the extant products of the New England Glass Company, of Massachu- setts. The other two were made at Zanes- ville by Murdock-Cassel and Shepard. These are but three of more than two hundred flasks in the collection. These objects help to illustrate the kind of effort that the Society is making to de- velop its collections. It is designed to meet a variety of purposes and to serve a number of publics, and it is applied to a number of collecting areas, including furniture, textiles, household utensils and furnishings, paintings, prints, firearms, tools, hardware, and metal products. It is an effort that must continue unabated and on an increasing scale if the Society is to meet its obligations to the citizens of Ohio. THE AUTHOR: William G. Keener is the curator of history of the Ohio Historical Society. |

|

|

COLLECTIONS AND EXHIBITS REMBRANDT and |

|

|

THE OHIO HISTORICAL SOCIETY by WILLIAM C. KEENER |

|

A FEW MONTHS ago the Metropolitan Museum of Art shocked the public, and certainly surprised the museum world, by paying the remarkable sum of $2,300,000 for Rembrandt's painting of "Aristotle Contemplating the Bust of Homer." It was an historic occasion and one filled with more than its share of drama. So- cialites, art dealers, critics, collectors, and museum people gathered for the sale in the austerely furnished main auction room at Parke - Bernet Galleries, New York, while less fortunate ticket holders were dispersed to nearby quarters and forced to participate via closed-circuit television. Not a few prominent and no- ticeably irate public figures were turned away. Excitement ran high, for although other fine paintings were to be sold, the Rembrandt commanded the attention-- and aroused the speculation--of every person present. Parke-Bernet auctions are especially |

|

well managed and move very quickly. Tension mounted steadily as the monoto- nous voice of the auctioneer droned the opening bid on the "Aristotle" -- one million dollars. Raised hands or subtle nods and other obscure bidding devices rapidly raised the price to the successful pinnacle, the highest price ever paid for a painting. In the weeks that followed, conscienti- ous reporters solicited opinions on this amazing purchase from all classes of peo- ple from cab drivers to bank presidents, and many thousands who had never set foot in a museum trekked to the Metro- politan to contemplate "Aristotle." For many it was the greatest painting they had ever seen; it evoked an emotional and aesthetic response of unequaled mag- nitude. But to almost everyone who saw it or read about it, it posed two nagging questions--why did it cost so much, and why did the museum buy it? |

(614) 297-2300