Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

- 20

- 21

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

|

CANNON THROUGH THE FOREST Novels of the Land Battles of the War of 1812 in the Old Northwest by C. HARRISON ORIANS |

|

|

|

On June 18, 1812, the Congress of the United States declared war on Great Britain. This action was the climax of a half-decade of irritations and contro- versy. The continental conflict, in which Britain was engaged, aggravated and inflamed the smoldering enmity which existed. The declaration marked the victory of the war party in the twelfth congress, elected in 1810. The war, with separate areas of conflict, fell into six divisions. There was the ocean itself, with naval combat and privateering activity. There was the New York, or Niagara, frontier. There was New England, with violent oppo- sition to war measures and the heralding of hostilities as "Mr. Madison's War." Fierce conflict raged along the gulf, at Pensacola, Mobile, and New Orleans. On Lake Erie the battle of the supply line was fought out between Barclay and Perry. And in the land struggles of the Northwest there was a year's dueling between the British and the Indians under Tecumseh on the one side, and General Harrison on the other. |

196 OHIO HISTORY

It is this last arena alone that

concerns us here. The record is anything

but glorious. America at the outset was

represented in the field by tired,

fearful, superannuated generals from

Revolutionary days. War was de-

clared before adequate preparations were

made, though Hull was sent north

to reinforce Detroit. Short enlistments,

poor planning, faulty equipment,

weak supply lines, an untrained soldiery,

an almost unpunctured wilder-

ness--these were the things that

guaranteed failure. Soon the record of

losses was abysmal. Michilimackinac fell

from surprise, Fort Dearborn was

evacuated and its defenders massacred.

The ingenious British commander

Brock bluffed Hull into an ignominious

surrender and went on to repulse

the American attempt to establish a

foothold on the Canadian side of

Niagara. In January, General Winchester

met calamity at the River Raisin

and lost the flower of the Kentucky

army. In early May 1813, the unstable

militia, under Dudley, fell victim to a

massacre at Fort Miamis. But in the

second year of the war, the American

land forces succeeded, with a victory

at Fort Stephenson, the ending of a

second siege at Fort Meigs, and the

recruitment of a new army under Governor

Shelby, in winning back what

had been lost in the first disastrous

months. Under Harrison's leadership

the northwestern army more than recouped

the early losses when it invaded

Canada and defeated the British and Indians

on the Thames, killing

Tecumseh in the process. The war

continued into another year, in the East

and the South, but the conflict in the

Northwest was over. It was felt at the

end, despite the nerveless peace treaty

and the inconclusive effects of much

of the fighting, that the young nation

had defended its flag nobly and thereby

won the kind of respect which would

prevent a recurrence of some of the

original annoyances.

The positive, optimistic note may be

traced in a score of novels covering

the Ohio-Michigan-Indiana arena in the

War of 1812. These novels, never

discussed as a unit, have only been

casually referred to in Quinn's American

Fiction and Leisy's The American Historical Novel. The

neglect of the

subject in more marginal works may be

understood.

Two of the works written in partial

reaction to the war were contemporary

documents and cannot be classified as

historical, except in a very loose

employment of terms. The first was Hugh

Henry Brackenridge's Modern

Chivalry, a quixotic, satirical work which appeared in final form

in 1815.

As a resident of Pittsburgh,

Brackenridge had little sympathy with New

England neutralism. Accordingly, in

Volume IV of Part II he burlesqued

the Hartford Convention and asserted

stoutly the justice of the American

cause. Speaking more or less as a

frontiersman, he inveighed against the

CANNON THROUGH THE FOREST

197

British employment of Indian allies to

kill and scalp. The British Bible

associations drew his contempt for their

silence, and the people of Birming-

ham and Manchester aroused his anger for

their manufacture of scalping

knives--people allegedly Christian, who

substituted weapons of cruel war-

fare for the peace and good will which

their religion preached. Such incon-

sistency, contended Brackenridge, fully

justified American hostility and the

invasion of Canada:

The fabrication of a single scalping

knife in their island and sending out for

the inhuman purpose of Indian murder,

and excoriation, was a just cause of war.

But was it expedient to invade Canada?

Was it a measure of defense to inter-

pose between these armourers and the

savages who used the arms? An answer

to this question will solve the problem.

It is not for the butchers of the island

that her manufacturers forge scalping

knives; for these knives are crooked, and

of a peculiar configuration; and the

tomahawks are formed with pipes in the

pol, which shew the face of the hatchet

to be for the use of the savage. Shame

to the name of civilized man, much more

a Christian people, that such things

should be done.

Second of the contemporary documents was

Woodworth's Champions of

Freedom. Though this work had priority in transcribing military

campaigns

upon the fictional page, it did not

prove sufficiently meritorious to attract

readers in its day, nor endure as a

worthy title to ours. Samuel Woodworth

obviously thought of himself as fusing

effectively bits of fictional confection

and actual transcripts from history. He

asserted rather vigorously that his

book was a better history of the war

than any of the works before it. This

was at best an idle claim. He thus

appeared to boast ascendancy over

Davison and Williams' Sketches of the

War, John Russell's History, Lewis

Thomson's Historical Sketches, O'Connor's

History, and Samuel Brown's

detailed war work published in Hanover

in 1815. Had McAfee and Inger-

soll published sooner, Woodworth would

probably have included them, too,

in his proud assertion.

A little baffled over the infusion of

"flowers of fancy" with strict fact,

a reviewer in the Port Folio for

February 1817 objected strenuously to the

Woodworth version of historical romance:

As we always perused with lively

emotions, the details of "the courage, enter-

prise, and success" of our arms in

the late encounter, we object most strenuously

to any mixture of fact and fiction. The

story of our fame may be recorded by

truth without the aid of imagination.

The numerous instances of individual

good conduct, during the late war, are

of too exalted a nature to be hawked about

by ballad-mongers. If this writer had

even mingled his inventions and his facts

198 OHIO HISTORY

in such a manner that we could

distinguish between them, we might not have

quarrelled with him on this score. As it

is, no one can draw the line.

Apart from the confusions arising from

hedgehopping from fact to fancy,

the novel breaks the credence barrier by

introducing at all crucial points

the mysterious voice of a deceased Miami

chief who rears up from time to

time to give the youthful hero helpful

and timely suggestions. In short, the

novel must be pronounced the flashiest,

most chaotic, and most unreadable

of the stories based upon the War of

1812.

Woodworth, unfortunately, did not follow

the fine model for the fusion

of imagination and fact that Scott was

currently providing in Waverley,

Guy Mannering, and The Antiquary, and he thus failed to be the

first to

domesticate the heroic romance in

America. No one else, during the great

historical romance movement of the

1820's, turned to the events of the War

of 1812, nor did Scott's formula appear

applicable. In Scott's early practice

the span of retrospection ranged from

twenty-five to sixty years, and there-

fore not until the mid-thirties could

American imitators find the requisite

time-lapse. It was 1836, in fact, before

the first novel utilizing the Ohio-

Indiana arena made its appearance, and

this can scarcely be pronounced a

document in the British-American war.

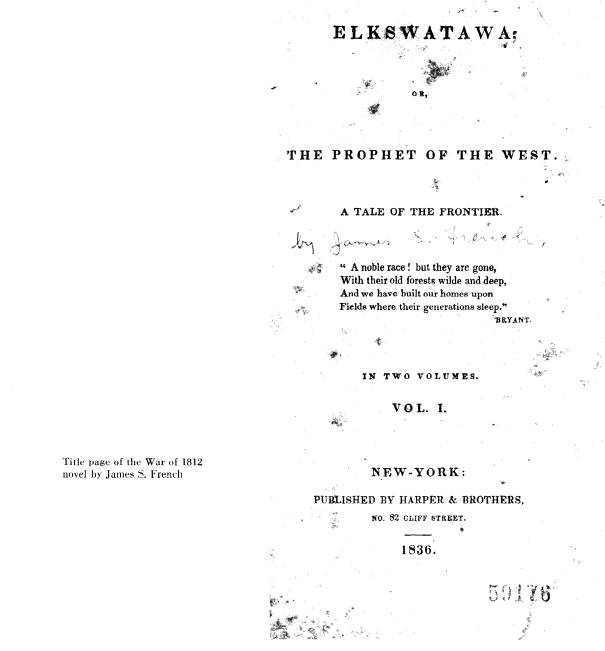

This was James S. French's

Elkswatawa, a slender piece featuring the battle of Tippecanoe

(1811) and

a group of fictional characters whose

fortunes were involved in it. The onset,

the novel's highlight, occurs in the

penultimate chapter. The work is men-

tioned here only because in the final

chapter (XXIV) the author envisions

the future of the several

characters--the fictional pairs; the Prophet, after

whom the novel was named; and also his

brother Tecumseh, whose post-

battle exertions are briefly summarized:

the council at Mississinewa, his

recruiting career, the council at

Malden, his clemency and humanity at Fort

Miamis, his troubles with Proctor, and

his death at the Thames. Several

pages of footnotes by the author and by

B. B. Thatcher debate the question

as to how Tecumseh met his death. The

last chapter is, moreover, a fine

eulogy to the Indian leader as the

greatest among red men.

Three years before French's novel was

printed, the Canadian Major John

Richardson busied himself with writing a

novel of the Forty-First Regiment

in the War of 1812. Final revision was

delayed until 1839 and printing

until 1840. Titled The Canadian

Brothers, this was the only war piece

written by an actual participant in the

events described. Richardson's own

regiment, which he had entered as a

gentleman volunteer, occupies the center

of the stage in the opening sections.

The officers' mess, the excitement at the

|

|

|

outbreak of hostilities, the capture of a schooner, the fights at Brownstown and Monguagon, and the flotilla of Tecumseh with a thousand recruits descending the Detroit emerges convincingly in print. From personal knowl- edge Richardson vividly presents many participants in the struggle: Brock, Proctor, Barclay, Walk-in-the-Water, Splitlog, Roundhead, and especially Tecumseh. The novel springs into life with Brock's dramatic bluffing of Hull into surrender, on which occasion the author himself acted as a member of the color guard of the occupying forces. Only such subsequent events as serve the fictional framework are unfolded: the building of the Canadian fleet, the investiture by Indians and Canadians of Fort Meigs, the battle of |

|

|

|

the Thames, and so forth. The story concludes with the Canadian recapture of Queenston Heights, an account much reduced in the revised version but indispensable for the final weaving of the strands of the novel. He post- dates the battle to October 1813 so that the novel may terminate with a victory instead of a defeat. The New York version of Richardson's novel, Mathilda Montgomery (1851), eliminates or cuts down many historical sections (Brownstown, Lake Erie, Fort Miamis, Fort Meigs). Only three historical matters are given with any fullness. One is the sundown career of Simon Girty, who is claimed as a loyal and worthy British subject. Girty had joined up with the British in 1778, operated as a British Indian agent for many years, and settled down on Canadian soil after 1796, when the British gave up Detroit. Girty, in his last years half inebriated, bursts on our view as a flavorful character, unre- strained but romantically picturesque. The second historical item is the River Raisin. This is not reddened in gruesome summary. It is viewed as a private would see it, the night bivouac, the before dawn reveille, the fearful marching toward an enemy yet invisible, the death of a close friend driven to foolhardiness by taunts from his associ- ates. It is war viewed from the ranks, not from field headquarters. The third historical account to receive expansion is the Proctor cam- paign against Fort Stephenson. Because the hero was captured here and sent |

CANNON THROUGH THE FOREST 201

as prisoner to Frankfort, Kentucky, the

author is justified in a detailed

account. Richardson supplies, what

American historians could not, the

military thinking that lay back of

Proctor's assault. The skilled and intrepid

maneuvering of the American commander is

nowhere more effectively pre-

sented than here, though Richardson

substitutes a fictitious Kentuckian for

the historical Croghan.

The novel in its first draft divides the

honors about equally between two

brothers, Gerald and Henry Grantham. But

as he proceeds, the story of

Gerald absorbs more and more of the

author's attention; and after he

decides to employ some of the details of

the Beauchampe tragedy, the care-

fully defined Scott plan verges upon

pure melodrama. Mathilda Mont-

gomery, betrayed by a Kentucky colonel,

vows vengeance upon him, makes

her way to beleaguered Detroit to effect

her purpose, and when foiled, enlists

the aid of Gerald Grantham and exacts

from him, as the price of her future

favor, the murder of her betrayer. She

thus places a burden upon him

which, as an honorable person, he is

unable to sustain. He cannot forget

his moral compunctions, nor can he escape

the lure of her faultless form.

His escape from his dilemma is both

fortuitous and fortunate.

Richardson thus gives an original

handling of the Beauchampe story, for

he, unlike W. G. Simms, employs none of

the names of the original partici-

pants. His seduced character, Mathilda,

unlike Simms' Margaret, evinces

scant affection for her entrapped agent

and shows no concern whatever for

his qualms of conscience. Richardson's

novel lacks an actual murder. When

Gerald's arms drop nervelessly at the

assassination moment, Mathilda with

a Lady Macbeth drive grabs the weapon

and delivers what she regards as

a fatal wound. Before the outcome is

discovered she has honor enough left

to take her own life.

Richardson's story shows the mark of the

Waverleys, especially Guy

Mannering, with the sporting expeditions, smugglers, Dandie

Dinmont

characters, and Indians who act as

cousins germane to Scott's gypsies. But

the resemblance is even closer to the

Cooper (whom Richardson prodigiously

admired) Lionel Lincoln, for like

Cooper's sinister tale of insanity and

old, unrighted wrongs, Richardson's is a

story of inherited curse; and it

has the free commingling of masks,

illicit trade, frontier brutality, midnight

plottings, even graveyard visitations

that critics have regarded as melo-

dramatic blemishes in Cooper's novel of

1825.

Richardson has the remote prophecy of

the mad Ellen Hathaway, uttered

in a previous novel (1832), fulfilled in

the death of the two brothers, the

one accidentally at the hand of the

other, and the second by Desborough,

202 OHIO HISTORY

son of Ellen, who plunges both victim

and himself to death over a precipice.

The American audience, after a decade of

melodrama and blood-pudding

was fairly ready for this plethora of

brutality, attempted assassinations,

and violence. One only regrets that an

author who was an eyewitness of

the Maumee-Detroit events of the war and

in a position to give inner details,

so frequently submerges historical

materials in the vast well of melodrama.

The year 1840 sent a number of workers

delving into the life and career

of William Henry Harrison. The log

cabin, hard cider, frontier songs

were all employed to heighten the

general's popularity. But authors had

scarcely launched on their programs when

the president's death flattened

prospects. Thematic pressures did not

cease, however. G. H. Colton went

on to complete his skilled but lengthy

poem on Tecumseh, a metrical ro-

mance, and the novelists completed narratives

well underway. First of the

fiction pieces in the Harrison cycle was

Mrs. Seba Smith's Western Captive,

or the Times of Tecumseh, which was issued in a special series of the New

World (1842). There is a legend that links the names of

Tecumseh and

Rebecca Galloway, daughter of a

prominent early settler of Xenia, Greene

County, Ohio. She is said to have

instructed a grateful Tecumseh in the

intricacies of English, though today

there are only dubious memorials of

that friendship. Mrs. Smith did not worry

about grounding her sentiments

in fact but unabashedly invented

Margaret, the Swaying Reed, a "white

maiden," for a heavy infusion of

romance. The story, which is so poetic

in style that it can almost be scanned,

has fatal defects. Featuring jealousy,

rivalry, and intrigue in an Indian

village, the author has the Indian-reared

white captive save her sister from a

religious burning by returning herself,

honor-bound, for immolation on a pyre of

sacrifice. Tecumseh saves her

from a flaming death but not from the

shock into which she falls nor from

a deep inner wound himself. After his

death in a nameless battle, his body

is carried by a faithful follower to lie

by the side of his beloved. Except

for his absence on Indian confederacy

business and the disappearance of

his body at the Thames, this is pure

invention. The tale is sentimentality,

full-orbed, and takes its proper place

with the legion of sentimental tales

of the eighteen-forties.

Kabaosa, by Anna Snelling, was the second in the Harrison cycle

and was

written in response to the hearty

exhortations of James Hall and Timothy

Flint, Cincinnatians with a brief for

the suitability of western materials

for works of fiction. While frequently

committed to the sentimental and

the feminine, Anna Snelling nevertheless

selected an essentially martial

subject. Such material she was

well-fitted to write. Sister-in-law of the

CANNON THROUGH THE FOREST 203

tale-writer W. J. Snelling, and

daughter-in-law of Colonel Josiah Snelling,

by whom Fort Snelling was built and for

whom it was subsequently named,

she was in position to draw upon

unpublished manuscripts, oral anecdotes,

and family accounts. She was

particularly indebted to the record of father-

in-law Josiah's military exploits. He

was a veteran of Tippecanoe, friend

of the Seneca Red Jacket, was stationed

at Detroit when Hull capitulated but

was exchanged early enough to

participate in the Niagara campaign. From

Josiah's career several portions of her

narrative stem. Her Major Stanmore

is but a thinly disguised portrait of

the colonel. His hurried marriage

to Julia Gordon on the brink of battle

has its parallel in the precipitancy of

Josiah's wedding. The vivid description

of the clash at Monguagon may

have owed to family accounts, for

Josiah's brave actions on August 9, 1812,

procured him the brevet of major. Late

in the novel, when Stanmore re-

fuses, as a prisoner in Montreal, to

take off his hat when marching by

Nelson's monument, he is recapitulating

an episode in the life of the

staunchly patriotic Colonel Snelling.

The title of the novel makes clear that

the work is a lament for the

injustice of the white man to the red

and a heavy sigh for the passing of

the noble Indian. There is always an

awareness of Tecumseh's greatness;

there is a tribute to the eloquent Red

Jacket, or Sagaota, a fundamentally

peace-loving friend of the Americans.

The novel proper terminates with

Chapter XXVI (a tribute to the warriors

of the West and William Henry

Harrison), but the author supplies a

postlude from the hand of her husband,

which sounds the nostalgic note for the

fate of the Indian and in particular

for the noble and much-wronged Kabaosa.

The novel has a complicated plot which

could have been considerably

clarified by a more experienced writer.

At the center is a Shawnee warrior

--with an adopted white son marvellously

skilled with the bow--and a

villainous Canadian colonel, regal agent

among the Indians but more

concerned for his own selfish

satisfaction than for the cause he is represent-

ing. Closely joined with Kabaosa is the boy's

true father, an ubiquitous

trader who acts as a general utility

agent and moves freely between Cana-

dian and American lines. These mobile

agents become involved in the

fate of two white cousins in love with

militia volunteers, and an Indian

maiden who is killed near the close of

the novel before her devotion to a

white volunteer can be rewarded.

Entrapped in Indian country near

Tippecanoe at the opening of hostili-

ties, the white maidens and their

escorts make their way in Cooperesque

fashion to Detroit, and thence, after

Hull's surrender, to Montreal. This

204 OHIO HISTORY

part of the story ends happily, for

their now-husbands are exchanged after

Perry's victory and share in the victory

at the Thames.

So simple a summary cannot suggest the

confusions and anachronisms

the author introduces to ensnare the

inattentive reader. The battle of Tippe-

canoe precedes not by a year but a few

weeks the engagements at Browns-

town and Monguagon. The surrender at Detroit

is tied closely to the Raisin

massacre. The defeat at Fort Miamis is

skipped and Colonel Miller's

triumph over Roundhead below Fort Meigs

is emphasized. This enables the

author to prepare her panegyric: after

the defeat of Winchester, Harrison's

career is a straightforward sweep of

victory. Despite this management,

however, Harrison appears only thrice in

the novel, each time to exhort

and enhearten his followers.

Thus the work has the lack of balance

that marks the novice. She writes

well. She has command of the sentimental

manner and can speak stiffly

in the heroic vein. But she yields to

preposterous coincidence, bringing

three independent parties to the mouth

of the Detroit River at precisely

the same time. She tries to enshrine in equal

balance Kabaosa, Harrison,

and the super-hero Sumner. Small wonder

that the reader is a little at a

loss as to where to place his

sympathies. There is little question, however,

that Kabaosa was designed to focus

varying strains, and the marriage of

the ultra-romantic characters before the

story is over convinces the reader

that marriage alone is not the final

goal toward which the romantic interest

of the novel is directed.

The only novel in this study to be

written by a novelist of known reputation

is Cooper's Oak Openings (1848).

It is a story of a half-dozen whites

trapped on the lower Kalamazoo River in

Michigan at the outbreak of the

War of 1812 near the present site of

Schoolcraft. They include Boden, a

bee-hunter, a drunken whiskey-trader and

his comely sister, an army ser-

geant, and an itinerant parson. With

them is Pigeonswing, a faithful

Yankee Indian who acts as a general

utility agent. His loyalty has been

intensified by Boden's after-dark rescue

of him from the Pottawatomies.

The enveloping Ojibway Indians, all of

whom have accepted wampum from

the British, are headed by a mysterious

tribeless Indian, strict invention

of Cooper, who combines the vision,

influence, and eloquence of Tecumseh

and Elkswatawa. This Indian, Englished

as Peter, and at the outset an

inveterate hater of whites, has called

fifty chieftains to a grand council to

institute a crusade for the extirpation

of all whites from Indian hunting

grounds. But as the narrative develops

he is awed by the wizardry of the

white bee-hunter, grows mellow in the

presence of the fair, light-hearted

CANNON THROUGH THE FOREST 205

Margery, and is finally subdued and

converted by the gospel of love as

preached by the unbelievable but

martyred Parson Amen. After two whites

have been killed by the Chippewas, Peter

finds, with his altered heart, that

he is not able to quench the fires he

has lighted. But at the last the surviving

whites escape their foes by

circumnavigating the lower peninsula, aided now

by both Pigeonswing and Scalping Peter.

Historically the novel is significant in

conveying the terror felt by isolated

whites in Michigan Territory after the

fall of Michilimackinac and Dearborn

and especially after Hull's surrender.

In no other novel is this difficulty

so fearsomely recorded. While no attempt

is made to run competition with

known historical accounts, the whole

narrative is skillfully projected against

the events of the first year and a half

of the war. The novel is also historical

in dramatizing the plight of the Indians

trying to hold back the hordes of

the whites debouching upon their hunting

grounds and debauching them with

whiskey and industrial products foreign

to their way of life.

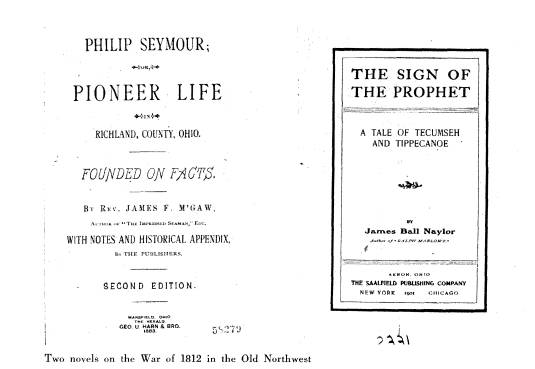

The eighth fictional work on the War of

1812 was a short maiden effort by

the Rev. James F. M'Gaw of Mansfield,

who sought to capitalize on local

legends for a very minor

quasi-historical piece. Titled after a frontier hero,

Philip Seymour, the work features events

along the Black Fork of the

Mohican in Richland and Ashland

counties. At the center of the story is

Captain Pipe, a venerable and well-loved

Delaware chief who lived on the

banks of the Mohican, but who, during

the period covered by the novel, takes

up residence in a local cave. He has an

adopted daughter whose beauty is

so great it leads an unsuccessful Indian

suitor to kill himself with May apple,

and another suitor--Montaur--to abduct

her and attempt the murder of

her romantic lover, Seymour. Her

disappearance, during the chaotic days

of 1812, leads to an extended search by

Phil and his scouting buddies. Their

search takes them, in trouble and out,

through the war-pathed wilderness of

northwestern Ohio. Bearing almost

charmed lives, they move about the

territory without wounds or incarceration,

and they eventually bring the

heroine Lily away from Malden. Her real

identity is disclosed, which

makes a happy marriage possible.

The historical nucleus was the Copus

affair. According to one version

of the story, the Christian Indians of

the region were in the process of

removal to a reservation in western Ohio

until peace times, but white soldiers

burned the Indian village before the

Indian residents were scarcely out of

sight. Retaliation naturally followed

this perfidy: the Ruffner and Zimmer

families were murdered and the Copus

cabin attacked. In this novel the

treachery of the whites is impartially

viewed and becomes the basis for a

story of rescue and recognition.

206 OHIO HISTORY

The novel lacks story-telling power and

organic unity. Because of the

slenderness of the basic tale, the

author secures bulk by almost unrelated

sketches of Johnny Appleseed, Black

Hoof, Beaver, and others and by the

introduction of such scenic wonders as

Eagle Rock, Hemlock Falls, the Black

Hand Gorge, and the rapids of the

Maumee. Into the web of the adventure

are also tenuously woven the attacks on

the Miami villages by Colonel

Campbell, the sieges of Fort Meigs, and

the death of Tecumseh.

This story was printed in 1858. It was a

generation before another dis-

tinctive story of the War of 1812 was

written. The great movement of

historical romance had slowed down

materially in England and America by

1860. Historical subjects still paraded

in the Beadle and DeWitt jackets

(Edward Ellis and others), and

occasional writers like George Cary

Eggleston kept the tradition alive

between the mid-century and the century's

end.

About 1889 the historical tale began to

stir anew. It found prompting

from Lew Wallace and other opponents of

the current realism. Following

the honor guard of Haggard and Stevenson,

in 1889 Mary Hartwell Cather-

wood produced The Romance of Dollard,

and in 1892 Edwin L. Bynner his

Zachary Phips, a novel of the West featuring Blennerhassett Island and

the

Burr conspiracy.

While the new costume romance covered

almost everything from the

fourteenth century to the nineteenth and

from the Mediterranean to the

frontiers of imagination, most of the

novels, like those of the eighteen-

twenties, were concerned with colonial

days, the Revolution, and frontier

adventures. None in the new movement got

around to the War of 1812 until

1901, when James Naylor returned to the

subject matter of J. S. French

and Anna Snelling, namely, the conflict

between the northwestern command

(under Harrison) and Tecumseh.

While the handling under Naylor is more

historicized fiction than fiction-

alized history, he does focus attention

on events from 1811 to 1813. The

novel The Sign of the Prophet, like

French's Elkswatawa, seems to be pri-

marily concerned with the brother of

Tecumseh and the battle of Tippecanoe

and its aftermath, yet in terms of

actual bulk, almost as many pages are

devoted to Fort Meigs (twelve pages), to

Clay's crossing of the Maumee

(twenty pages), and to the Dudley

massacre (five pages) as to Tippecanoe

(Chapter IV) and its aftermath (Chapters

V and VI).

Basically, the story is that of a young

man from Franklinton, partly reared

by the Wyandots, who with Bright

Wings--alleged son of the lamented

Indian chief Leatherlips--joins

Harrison's army, is captured by the Indians,

|

|

|

is wounded at Tippecanoe, is pursued in a Cooper-like forest-tracking, and is nursed back to health by La Violette. The last third of the book is devoted to affairs at the Maumee rapids and the repulsion of the Canadians and Indians before Fort Meigs. While in this novel the Prophet occupies the center of the stage with his hypnotic power and his diamond talisman--even after Tippecanoe--Tecum- seh is introduced with several passages of eulogy, along with the well-known story of his rebuke of Proctor for his inability to control the Indians. The plot proffers a mysterious British agent who guards over the hero, preventing a foolhardy attempt at escape, and in the end turns out to be his father. This device was used by many novelists of the time, though rarely with the verbal irony here employed. Near the close of the book the hero finds that his former sweetheart whom he had diligently sought, had married another by whom she has been victimized. Though aware of her pitiful plight, he is now free to marry his Indian-trained white sweetheart from whom he secures the valuable talisman, once the potent possession of Elkswatawa. In the final melodramatic scene the novel loses both dignity and historicity. The husband of his former sweetheart is killed, he himself drives back the hostiles at Fort Miamis with the talisman, his father sacrifices himself to save his son, and the hero is united with his French heiress, an erstwhile forest-reared maiden. Thus history and imagination are vigor- ously interfused. |

208 OHIO HISTORY

The fecund years of the historical

romance had not quite terminated

when the Midwest again afforded subject

matter for three more historical

romances. In 1904 Randall Parrish

published When Wilderness Was King

(Fort Dearborn) and Myrtle Reed issued The

Shadow of Victory featuring

the same historical figures: Captain

Heald, William Wells, "Trader" Kinzie,

and others. These are, of course,

outside our interest here. But Ohio and

Michigan came impressively into their

own with Mary C. Crowley's work of

1903. Labeled Love Thrives in War, the

novel only proves that love is

baffling and tragically complicated by

war. To Laurente, a Scottish girl,

the author assigns no less than three

lovers, a worthy fellow Scotsman

(killed at the Raisin), a

French-American to whom she is devoted, and a

half-breed who tries barter, mendacity,

and kidnapping to win her for a

wife, and from whose persecutions she is

freed by the great Tecumseh

himself. The author in her wonted

fashion made a thorough study of

potential martial episodes and gave

fairly accurate descriptions of the events

included. In historic matters she never

ventured far from her documents,

however freely her imagination roved when

describing the heroine's emo-

tional distresses.

Thus in a sense her account runs

competition with history. One-third of

the total traces the domestic and

military repercussions of Hull's surrender,

both among Canadians and Americans. Two

other events are treated ex-

pansively, the massacre at the River

Raisin and the debacle at Fort Miamis,

each accorded a dozen or more pages. The

latter account includes the

humanitarian actions of the noble

Tecumseh. Lesser-known figures appear

also, Captain Snelling, who moves in

fiction for the first time under his

own name, Whitmore Knaggs, scout and

guide at Meigs and Monroe and

trader at Maumee, and Lewis Cass, whose

actions before the Detroit capitu-

lation are given a lively presentation.

In these sections the author makes a

significant contribution, supplying

authentic figures little featured elsewhere.

The novel gains force from its clear

interpretations of Hull's cowardice,

Proctor's inhumanity, and Tecumseh's

dignity and leadership. The author,

for all the shallowness suggested by the

lightness of the novel's sentiments

and the flood of fragmentary incident

and anecdote, is skilled in utilizing

marginal items and making them fall like

pieces of a puzzle into place. Even

the great comet of 1811, referred to by

the Shawnees as "The Arm of

Tecumseh," and the earthquake of

1812 (actually a series, 1811-12) are

expertly employed and tied into the

action.

After a lull of a quarter-century, the

historical romance came back in

the late twenties. Subsequently eight

novels dealt with military clashes in

the Maumee Valley. The modern revival

began with Trumpet in the Wilder-

|

|

|

ness (1940) by Robert S. Harper, a story of a frontiersman who lost a Philadelphia sweetheart with managerial tendencies and won a stalwart girl of the lakeshore West. In a novel of judgment, the novelist cannot stop to debate motives nor can he present contemporary opinion as suspended when in reality it was very active. He has to assume one point of view and ascribe this to his hero and his associates. He may, if he is conscientious, suggest another possibility in fine print, but he cannot arrest the action to debate how Tecumseh died, to explain Winchester's stupidity, or to justify Hull's cowardice. Thus in this novel the naval role of Elliott is clearly not a debatable one. Elliott is sharply censured for his failure to follow instructions. For the land action the movement of the balance is just as positive. Hull is presented as over-fat, over-stubborn, and over-pompous even from the beginning. His action at Detroit might have been explained by near-cowardice, the overcautiousness of age, excessive intoxication, or the dust-flinging activities of the astute Brock. But however extenuating the circumstances, they do not appear here. Hull of the novel is deserving of immediate court-martial. He appears as a stupid, treasonable person, whose motives are otherwise beyond understanding. He makes a feint at Malden, then withdraws into the fort. While his able assistants are out on a foray to protect a supply train, he hoists the white flag over the fort without warn- ing, without advice, and without a gun being fired. It is true that an occasional historian has found grounds to somewhat condone Hull's action, |

|

|

|

but in this novel there appear none. Hull is set down as a coward and a traitor, and there is no gray in the picture to relieve the intense blackness of his record. One other historical factor must be observed. The effect on the back country of the fall of Detroit--the opening up of the territory to Indian attacks--is skillfully hinted when not directly portrayed. The impact of Harrison's withstanding the Canadians and the Indians at Fort Meigs is also vigorously recited. This portion of the story is only by report, not direct action, but it serves to fill in the mental blanks that a reader of the progress of a single hero is bound to have. Hull comes off equally bad at the hands of Ralph Beebe in his novel Who Fought and Bled, published the year following. We glimpse Hull as old, fearful, vacillating, soft, inconsistent, and lacking in intrepidity, valor, and basic military judgment. Heralded by his disgruntled men as the best major general in the English army, Hull, as represented, fully justifies all the charges brought out in his court-martial. To the situation in Detroit the author devotes over a hundred pages of his novel, with a description of all the shilly-shallying that went on prior to Hull's capitulation. Structurally, the novel is autobiographical, involving two frontier scouts: the one, an ex-Boston man, literary and poised, and the second, Alijah (Buck) Stark, a rough, uncouth, opinionated frontier original, thoroughly western in warp and woof. These two partners in an Ohio homestead and in the scouting operations in which they engage, become attached to the ill- |

CANNON THROUGH THE FOREST 211

fated Hull expedition, helping lay out

the military road north of Urbana,

and escaping from the joint debacles at

Detroit and Frenchtown.

The novel traces historically only the

tragedy of the first five months of

the war. Central in the book--after the

sad, tired old men, and Colonel

"Braddock" Van Horne--are men

under no cloud: Colonel McArthur,

Captain Brush, and the British General

Brock. The depressing and negative

aspects of the novel are balanced and

relieved by the cleverness of the scouts,

their resourcefulness, and a mere touch

of romance. A slight segment of the

war without a conclusion, the novel

escapes despair by the reader's own

historical knowledge that there will be

brighter scenes on the morrow.

An aftermath of the fall of Detroit was

the siege of Fort Wayne by the

Indians. Lacking artillery, they

attempted encirclement and starvation. This

policy emerges in Mary Schumann's My

Blood and My Treasure (1941).

The story is told in somewhat lax and

sentimental language. As woman,

the author wisely eschews lengthy

descriptions of events like the battle of

the Thames, the siege of Fort Meigs, the

Van Horne affair at Brownstown,

and the Fort Dearborn massacre. The

story is, in fact, primarily a love story

in wartime, and involves the expanding

portraits of two rivals for the hand of

the hero: Louisa (French-Indian) and

Jane Starling, outspoken daughter of

the frontier. Other women also stalk the

pages: Alagwa (wife of Black

Hoof), Polly Biddle, a red-headed widow

named Susan Seacoast, and Rich-

amah, lass of easy virtue.

But even in a sentimental tale projected

against a background of war,

something has to be featured, and in

this novel the emphasis is twofold,

the relief of the garrison at Fort

Wayne, and the battle of Lake Erie. The

conditions at Fort Wayne prior to Hull's

capitulation are described along

with the death of Little Turtle. Shortly

after the capitulation news arrives,

the women and children are removed

through the aid of a noble Shawnee

tribesman, Logan, whose demise is

related in Chapter Seventeen. Harrison's

advance sends the Indians scattering

just when their depredations and on-

slaught seem serious and the loss of the

fort imminent.

The last third of the novel chronicles

Perry's building of the fleet and its

manipulation over the sand bars, and

presents in fifty pages the lake battle

itself and the personalities involved,

both historical and fictional. Perry

is eulogized and Elliott vigorously

arraigned.

Horrifying aspects of the war are

presented, though by report and not

in the omniscient recording of the

author. The hero sees the surviving

captives from the Raisin massacre

paraded at Malden. But for all the

historical materials, this is a

relatively simple, emotional tale. There is an

attempt by Mrs. Schumann to complicate

it by philosophical overtones in

212 OHIO HISTORY

the opening and close and by occasional

passages of meditation throughout.

This she accomplishes by introducing the

Swedenborgian mysticism of

Johnny Appleseed. Chapman's love of all

created things and his pacifism,

his esteem for Tecumseh, and his hatred

of violence introduce an objective

note at the beginning. War comes, claims

Chapman, because of evil thinking,

intellectual treacheries, ungodly

leadership. Only when men are led by men

of spiritual greatness and intellectual

ability can peace be achieved. And

in the vaporings of piety and mysticism

the novel ends, with considerable

brooding over the riddles of peace and

the conflicting destinies of hunter

and agricultural peoples. American

citizens, contends Chapman, though

they must pay for wrongs inflicted, will

glimpse the high destiny of the

nation, will understand freedom, and

will gain the soul wisdom which

"unlocks gates of perpetual

beauty." The author differs from the other

novelists therefore in providing an

interesting envelope structure for what

is otherwise a simple tale of love and

war.

Several of the novels failed to

concentrate on particular events or topics,

such as a naval battle, the fall of

Detroit, the affair at Monguagon. They go

beyond closely related events or

sequences. Some afford one-man biog-

raphies of wide-roving heroes or capture

frontier life in and out of wartime

or send their heroes to the most

exciting areas, regardless of plausibility,

to gain an equivalent of swashbuckling

romance.

First of the peripheral novels was Hearts

Undaunted (1917) by Eleanor

Atkinson, a light, fictionalized

biography of John Kinzie, frontiersman,

trader, and silversmith. The action

begins with Lord Dunmore's War and

the protest of the Iroquois over treaty

violations. From the Niagara Frontier

to Detroit, to Parc aux Vaches, to

Chicago the trader's business and romance

carry us. The bulk of the novel, however

interesting and faithful, is outside

the province here: the two marriages of

Nellie Lytle (McKillip), the suc-

cessful trading post of John Kinzie in

Chicago, John and Nellie's escape

from the Fort Dearborn massacre through

the agency of Ouilmette and

Chief Black Partridge. Kinzie, after the

escape to Detroit, is unjustly im-

prisoned at Malden. During his

confinement the sieges of Fort Meigs, the

attack on Stephenson, and the battle of

Lake Erie take place, and they are

reported to him as they are reported to

us. These events are condensed in a

dozen pages of hasty and uncertain

summary. Other historical matters the

novel also encompasses: the death of Sir

William Johnson, the career of

the venerable Cornplanter, the tragedy

of the stalwart William Wells at

Chicago. With the irrepressible and

intrepid spirit of Nellie of the Senecas

attractively and ingeniously set forth,

this proves a light and readable story

by the author of Greyfriars Bobby.

CANNON THROUGH THE FOREST 213

Another of these dispersed narratives is

Marguerite Allis' To Keep Us

Free, the second in a tetralogy of talky, homey stories of

pioneer life in the

Ohio wilderness. The novel is believable

but slow-paced. It presents the

usual melange of frontier occurrences,

family ties, births, school days,

travels, malaria, accidental deaths,

town meetings. Life in Marietta and

the slender beginnings of life in Cleveland

are the focal centers for a story

that embraces the story of the

Blennerhassetts, the beginnings of statehood,

and the events of the War of 1812, for

which the story is closer to history

than to fiction. By the creation of

several sons and a nephew of the hero,

the author has found a mechanism with

which to review the usual events of

the northwest campaign, Winchester's

folly, the sieges of Fort Meigs, the

victory on the lake, and the final

removal of danger. All these events are

loosely associated with the fictional

career of Ashbel Field, friend and

associate of Meigs, Worthington, and

General Harrison. Imparting meaning

and dignity to the narrative is the

well-urged theme of independence: "A

heritage of security was not calculated

to develop strong men. What made

men strong was the necessity to fight

and work for what they wanted, for

freedom to make their own way in the

world." Thus the events connected

with pioneer life in the Western Reserve

and the crucial events in the

Maumee country furnish modern lessons

written large.

Long Meadows (1941), by Minnie Hite Moody, is a close-grained and

complicated genealogical novel tracing

six generations of a somewhat clan-

nish, prolific family through a century

and a half of pioneering and removals

southwest and west into the Ohio Valley.

The Dutch progenitor Joist Heydt,

seeking a kind of immortality through

offspring, plants his sons freely as

he moves from Kingston, New York, to

Perkimer Creek, Pennsylvania, to

the Shenandoah to Hampshire County, West

Virginia. His great-grandsons

lengthen the family holdings to

Lithopolis, Ohio, Louisville, and southern

Indiana. The novel is partly domestic,

with its weddings, its birthings and

deaths and sicknesses, its separations

and trials, and its welter of similar

names which almost guarantee confusion.

It is sociological, too, with its

Virginia traditions, flying axes, and

surveyor's chains, its receding Shawnees

and Indian medicine, its boundary

disputes, trail-blazing, and frontier

scouting.

The land-grabbing, so consistently

apparent, is accompanied with trouble,

especially from the dispossessed red

man. The novel, like many one-time

histories, breaks down into wars and

rumors of wars, thus confirming the

judgment of Governor Shelby: "Every

time I hear the word war, the next

man I see is a Hite." There were

sons five generations removed in the

Civil War (with which the novel

concludes) and cousins, too, fighting on

214 OHIO HISTORY

opposite sides. Earlier there was

Abraham Hite, on duty with the Eighth

Virginia Regiment during the Revolution,

present at Monmouth and at

King's Mountain. There was Abraham, Jr.,

and Isaac at Point Pleasant in

Lord Dunmore's War and Colonel John Hite

and Joseph Bowman with

Clark at Kaskaskia.

And there was Captain James Hite who

fought in the War of 1812. He

force-marches with Harrison to the

relief of Fort Wayne. He accompanies

Colonel Campbell on his raid on the

Mississinewa towns and freezes his feet

dashing madly in the bitter cold for

badly needed relief forces. Later he

rides north to join Harrison, garnering

as he goes evidence of the suffering

at Fort Winchester and straggler talk of

the loss of the Kentucky army at

the Raisin. He sits out in weariness the

siege of Fort Meigs.

From Kentucky, numbed with grief at the

loss of his wife, he moves again

with Governor Shelby, glorying with

others when news of the triumph of

Put-in-Bay comes silvering through the

forest, and sweeping north with the

3,000 Kentuckians over the lake into

Canada. Their horses, except for those

in Colonel Johnson's force, are enclosed

in a brush paddock on the Port

Clinton peninsula. They move past the

smoking remains of Fort Malden

and advance in what amounts to forced

marches to Dolsen's. At Moravian

Town the armies clash, the mounted

riflemen charging to the cry of

"Remember the Raisin," and in

a few minutes the conflict is over. The

author of the novel is a little vague as

to the maneuvering of the forces

and as to the cause for the sudden

collapse of the British opposition. She

concerns herself primarily with the

fighting on the Indian flank and ignores

the vulnerable open formation at the

center. But she is rightly certain

that Tecumseh's body was not found on

the battlefield the next day. Though

not guilty of heralding the fight as

glorious, she complicates the account

to twenty pages by emphasis upon

individual sensibilities, the hero's self-

communing, and prisoner despair,

especially that of the ill-fated Moravian

Indians to whom war came a second time

though they had moved far to

escape it.

Only marginally in the category of the

Maumee country is a work by

Robert W. Chambers called The Rake

and the Hussy. This novel covers

the wide-ranging movements of a hero,

New York born, who starts his ad-

ventures in London and concludes them

with Jackson at New Orleans. The

hazards of Joshua Brooke, the rake, and

Naia Strayling, his mistress, are

traced through three years, eight

states, and six engagements. Brooke, who

arrived from England with stolen

dispatches, for which he is closely pursued,

is present at the Fort Mims massacre in

Alabama. He survives but with

wounds to show for his participation. In

late 1813 he is further embroiled

CANNON THROUGH THE FOREST 215

in hostilities by making contact with

Harrison's army, then on the move to

regain Detroit. He reaches the army on

the eve of battle, finds himself in

the forefront of the fighting at the

Thames, but the battle is over so swiftly

and he is so well surrounded by fighting

men, sound and strong, that he

escapes further injury. Not satisfied to

withdraw with his laurels, he shuttles

south again, taking part in Jackson's

campaigns at Fort Bowyer, Pensacola,

and New Orleans.

This summary does not make clear what a

swashbuckling romance this

is--almost cloak-and-dagger--for there

is plotting, almost from the begin-

ning, for the fortune of the young lady,

and there is a whole series of narrow

escapes. Finally, the uncertainty as to

the couple's dubious relations main-

tains the mystery to the very end.

Historically, Chambers was justified in

including a second visit of Tecumseh to

the Creek council. There is no

warrant whatever, except melodramatic

color, for his introduction of Elks-

watawa in that arena.

The last of the novels of dispersed

action was Wolves Against the Moon,

(1940) by Julia Cooley Altrocchi, a long

novel that deals with the events

on the northwestern frontier from 1794

to 1833. This is a mildly fiction-

alized biography. While it is the story

of a trader who established trading

posts at Detroit, Mackinac, at Parc aux

Vaches, at Baton Rouge, and on the

Little Calumet River, it is also a story

of blood and confusion, of rivalry

and intrigue. Basically the story of the

people whose lives were closely

coiled in with those of Joseph and Marie

Bailly, the book crisscrosses the

trails of history, too. There unfolds,

therefore, a vast multiplicity of adven-

tures, mostly of factual character.

There is a picture of the far-flung fur-

trading empires of the day, of the acute

competition, plottings, cupidity, and

treachery which ensue. There are

episodes along the old Sauk trail, the

Detroit fire of 1805, the cholera

epidemic. Fascinating pictures of famed

personalities the book affords, too, of

John Kinzie, William Wells, the

Shawnee Logan, Pokagon, and scout Peter

Navarre, who appears at greater

length here than in any other novel.

Only Chapters XV to XX deal with the War

of 1812. Chapters XVI,

XVII, and XVIII describe the massacre at

Chicago and its aftermath and

are thus out of consideration in this

account. Chapter XV includes a careful

description of the seizure of

Michilimackinac on July 17, 1812. Here,

fortunately, no hothead unleashed

"the wolves of disaster," wolves like

Shavehead, Topenebee, Buns, De la Vigne,

Bluejacket, and Black Loon. The

guards are withdrawn, the guns are

silent: the thousand Indians and a

small British force under Roberts accept

without violence the surrender of

Lieutenant Porter Hanks and his

seventy-nine men.

216 OHIO HISTORY

The longest and most pertinent military

section is the description of the

River Raisin massacre, to which the

author devotes twenty-one pages.

Winchester's refusal to be alarmed at

the threat from Maiden and Proctor,

and his almost total lack of

common-sense precautions make possible the

dreadful massacre in which the fine

flower of Kentuckian manhood is

destroyed. Proctor's guarantees proving

neither honest nor effective, the

wounded are slain, captives tortured and

hacked. Both the style and the

message of the chapter can be perceived

in the following passage:

It seemed as if all the gathering fury

of the Indians poured itself out in a flood

of purple intoxication on the River of

Grapes. Perhaps the presence of Tecumseh

himself on the battlefield, swirling his

followers into a frenzy of madness, perhaps

the recoil from the repulses at

Tippecanoe and Fort Harrison and Fort Wayne,

perhaps the blood in the eyes of the

warriors who had so recently enjoyed the

glory of slaughter at Fort Dearborn,

perhaps the ferocity of the yet undistin-

guished but wild young Black Hawk with

his contingent of braves from the Rock

River, or the sight of the blood of

Winchester's "fallen," and the indifference of

General Proctor to the usual horrible

Indian sequels, or the frenzied combination

of all these elements, fermented the

grapes of intoxication and helped to create

such scenes as had not been witnessed

since Pontiac, such horrors as were to lead

to the American battle cry of

"Remember the Raisin!" and to the final American

victory at the Battle of the Thames.

Eliminate Tecumseh, who was on the

Wabash, and the Pottawatomies, who

are not known to have been engaged at

the Raisin, and the passage might

sustain its poetic overwriting.

This brings to a close our

sesquicentennial review of the novels of the

Maumee country. Even considering their

number and the seven thousand

pages at the disposal of the novelists,

one is still surprised at the variety of

theme and episode presented. Most of the

events of any magnitude or pro-

portion in the Northwest were crowded

in, from the 1812 building of a

military road, the supply trouble at

Brownstown and Monguagon, the lifting

of three sieges at Forts Wayne and

Meigs, Colonel Campbell's descent on

the Miami towns, the activities of

spying parties and coureurs de bois, to the

battle of the Thames. Demonstrating

novelistic zeal for originality and

diligent research was the inclusion of

lesser-known figures such as Peter

Navarre, Whitmore Knaggs, Colonel

Miller, Captain Brush, the Shawnee

Logan, Black Hoof, and Johnny Appleseed.

Certain events, of course,

occurred in upwards of a dozen novels,

particularly Hull's inglorious sur-

render at Detroit and Winchester's

catastrophe at the River Raisin. Revolting

though both were to American

sensibilities, they seem to have gained prom-

inence and to have been more often

repeated than any other events. It was

CANNON THROUGH THE FOREST 217

not a matter of their being more

important. Their attraction seems to have

been the American shock over them. As

far as variety is concerned, even

the limited material which these

setbacks had to offer does not oppress the

reader with sameness, woodenness, or

repetitiveness. The authors, working

independently, and unaware of one

another's activity in most cases, suc-

ceeded admirably in avoiding duplication.

Certain matters of military interest

seem, however, to have been unduly

submerged. Such was the enclosure at

Fort Meigs. A siege is an investiture

of a stronghold, persisted in to wear

down the defenders or to cut them off

from necessary stores. It is something

that has to be waited out, ordinarily

with day-by-day weariness. Except for

supply difficulties, which are in a

sense negative, there is not much that

can be done to make it dramatic. Only

by the arrival of relief troops or

mistaken sallies from a stronghold can a

siege furnish the kind of action the

novelist clamors for. Colonel Miller's

foray against Roundhead and the fighting

of Clay's forces to get "into" the

fort were the kind of non-routine

actions referred to.

Two other matters may be labeled as

neglected. The activity of the

political leaders responsible for

raising the militia quotas was somewhat

unheeded, for the simple reason perhaps

that recruiting activity does not

lend itself to novelistic color. Another

topic was only lightly touched upon,

chiefly in Moody. This was the suffering

of the men at Fort Winchester, the

Valley Forge of the West. The romantic

novelists like action: periods of

inactivity, exhaustion, and frustration

do not lend themselves to their

purposes. The historical school of the

nineteenth century might present low-

life characters and scenes, but the

shabbier aspects of such life they in-

variably eschewed. In the twentieth

century no writer of the Cummings

school chanced upon the story of Fort

Winchester, cut off from population

centers by hip-deep mud and its supply

lines immobilized by miles of

trackless forest. The days of privation,

freezing, thievery, infection, gan-

grene, despair still await a chronicler.

From the various accounts two figures

mount to places of prominence,

Harrison and Tecumseh. In most of the

novels Harrison was heartily

praised, especially in the works

prompted by his presidential candidacy in

1840 and by the centennial celebrations of

the Tippecanoe campaign in

1940-41. But if the works of authors

like Anna Snelling seem to have been

written to glorify the warriors of the

West and Harrison in particular, there

were other nominations for fame that

took off some of Harrison's luster,

and certain factors that kept his fame

sharply within bounds: the weight

of the defeat at Fort Miamis, the

inconclusive character of the siege of Meigs

itself, the spotlighting of young

Croghan at Lower Sandusky, and the recog-

218 OHIO HISTORY

nition of the inevitability of victory

at the Thames. After the loss of Lake

Erie by the British, the outcome in

western Upper Canada was very clear.

Harrison's reputation, apart from the

advantages of the rhythm, was more

closely associated with Tippecanoe than

with Thames. And there were

mental reservations by some novelists

who recognized that Harrison's army

in 1811 was manifestly invading Indian

territory, and that the treaty of

Fort Wayne in 1809 was clear evidence

of white perfidy. They were un-

willing to join the chorus of praise

for the northwestern general. In com-

parison with the bunglers, Winchester

and Hull, however, Harrison's career

shone with undiminished splendor.

The one consistent theme in the novels

was the greatness and nobility of

Tecumseh. All of the authors, early or

late, had the same feeling of esteem

for this great leader of the Indians,

his eloquence, his humanity, his political

leadership. In some this praise became

a major theme, in others it was a

digressive judgment, but it was one

note invariably found.

The novels treating martial conflict in

the Northwest compare very favor-

ably in both quantity and quality with

those devoted to other areas of the

war. The sea, regarded as paramount in

war affairs, both in terms of causes

and clashes, was vigorously represented

by a dozen romances, including

those describing sea-borne invasions

and the multifarious activities of

privateers. Such novels as Brady's In

the Wasp's Nest, Post's Smith Brunt,

Forester's Captain from Connecticut, and

Kenneth Roberts' Captain Caution

are amply representative of this

maritime field, and they present effective

descriptions of the cumulative distress

produced by war.

The land event that produced the

greatest impact from the smallest action

was the massacre at Fort Dearborn. That

this frontier post was treated in at

least nine novels (five already

mentioned in this account) may prove sur-

prising, and can only be accounted for

by the fact that it was the first action

to take place on the present site of

Chicago. Thus its connection with

America's second city has lifted it

from the obscurity into which it might

otherwise have sunk.

New Orleans as a locale for historical

romance might at first glance seem

to rival the Maumee in the total

output. Nine novels carried the story of

Jackson's success in the motley city on

the lower Mississippi. This is fewer

in number than those touching Fort

Meigs, unless we add to the first dozen

the never-ending series celebrative of

Jean and Pierre Lafitte. The strongest

New Orleans romances were those glorifying

Old Hickory, especially

Holdfast Gaines, the Cavalier of Tennessee, and Hearts of

Hickory.

Lake Erie novels could, except for the

growing bulk of the unit, have

been treated directly with Meigs and

Thames. Eight novels dovetailed the

CANNON THROUGH THE FOREST 219

Perry action between Fort Stephenson and

the Thames, including We Have

Met the Enemy, D'ri and I, and the Fleet in the Forest.

Clearly then, the region of the Maumee

produced the greatest number of

novels covering 1810-14. Events here

seemed to have an appeal because

they could clearly be arranged on an

ascending scale. From the opening set-

backs and defeats--Michilimackinac, Detroit,

Raisin, Miamis--American

prospects brightened rapidly, and

novelists joyfully shared in the positive

and optimistic thrust. They were happy

to put the records of Colonel Miller,

of George Croghan, of William Henry

Harrison upon their pages, thus

chronicling an inclining stairway of

success and listening to anthems of

victory.

Because the novelists were dealing with

people as well as with actions,

events, and maneuvers that made history,

they were able to present living

personalities, to adduce the hopes,

fears, ambitions of participants, and to

introduce such characters in situations

where the full range of their emotions

might properly be evoked. The novelists

frequently exercised the artist's

prerogative of ignoring events which did

not fit their patterns, but few of

them changed radically the known

historical facts. They wisely used fictional

names rather than historical ones when

modifying events and they supple-

mented or added to the details that

documents too sketchily afforded, but

they would not have been novelists had

they not done so. The War of 1812

was a conflict that offered a number of

lessons for another age or generation,

not because writers were probing for

them or were trying to be didactic, but

because so many mistakes were made that

any enactment of the scenes had

perforce to disclose them and to show

also the sufferings of human beings

which they entailed. They suffered as

human beings do at all times when

public events impinge adversely upon

their lives. The folly and mismanage-

ment in Washington--total

unpreparedness, the flinging of untrained troops

into battle where they were either

victims of their own fear or of their own

foolhardiness--these things the

novelists were able to bring home to every

reader. It is only to be hoped that

America will never again see so con-

tinuous a record of sacrifice upon the

part of individual soldiers and for

reasons so inexcusable.

THE AUTHOR: G. Harrison Orians is a

professor of English at the University

of Toledo

who has written extensively on the local

scene.

|

CANNON THROUGH THE FOREST Novels of the Land Battles of the War of 1812 in the Old Northwest by C. HARRISON ORIANS |

|

|

|

On June 18, 1812, the Congress of the United States declared war on Great Britain. This action was the climax of a half-decade of irritations and contro- versy. The continental conflict, in which Britain was engaged, aggravated and inflamed the smoldering enmity which existed. The declaration marked the victory of the war party in the twelfth congress, elected in 1810. The war, with separate areas of conflict, fell into six divisions. There was the ocean itself, with naval combat and privateering activity. There was the New York, or Niagara, frontier. There was New England, with violent oppo- sition to war measures and the heralding of hostilities as "Mr. Madison's War." Fierce conflict raged along the gulf, at Pensacola, Mobile, and New Orleans. On Lake Erie the battle of the supply line was fought out between Barclay and Perry. And in the land struggles of the Northwest there was a year's dueling between the British and the Indians under Tecumseh on the one side, and General Harrison on the other. |

(614) 297-2300