Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

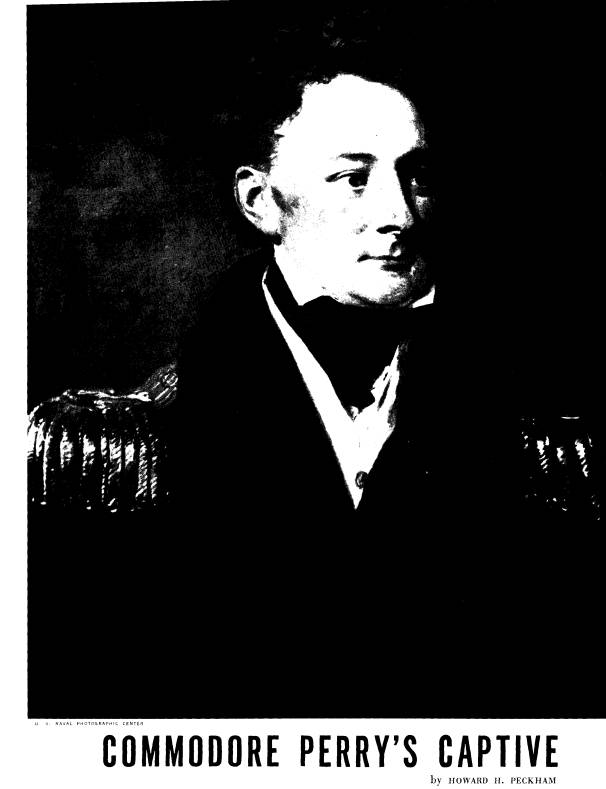

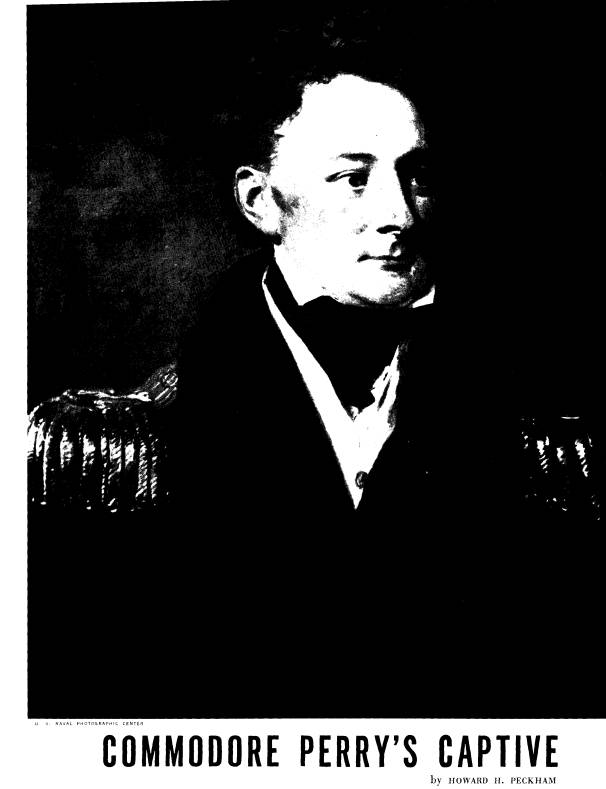

It is the fate of defeated generals and

admirals to be forgotten. Everyone in

Ohio and the Old Northwest hears of the

victory of Commodore Oliver

Hazard Perry on Lake Erie in 1813, but

ordinarily remains ignorant of

the British commander he defeated.

England is a country most proficient

in ignoring unsuccessful military

figures. The fate of Perry's opponent may

not have been just, but it was typical.

Exactly what happened to him has

been clarified only by the recent acquisition

of a handful of his papers by

the William L. Clements Library of the

University of Michigan.

Briefly, the engagement of September 10,

1813, resulted from the decision

by Major General Henry Procter that

Captain Robert Heriot Barclay, com-

manding His Majesty's squadron on Lake

Erie, should leave his base at

Amherstburg in order to get needed

supplies for the army and navy at Fort

Erie. He had been delayed first by the

finishing of a new flagship, the

Detroit, of 470 tons and 19 guns, and then by lack of full

crews. The rest

of his squadron consisted of the Queen

Charlotte, 280 tons and 17 guns, and

four smaller vessels totaling 27 guns.

He had some 240 British soldiers

aboard serving as marines.

Waiting for emergence of the British,

Perry stationed himself at Put-in-

Bay with a larger squadron: two brigs,

the Lawrence and the Niagara, each

of 480 tons and 20 guns, and seven

smaller vessels with 14 guns. The weight

of metal was with Perry in close action,

but in long-range guns Barclay had

35 to Perry's 16. In effective manpower

the British had about 500 against

416 Americans.

The wind was with the British at first,

but before battle was joined the

wind shifted to favor Perry. In more

than three hours of battle, Perry

suffered his flagship the Lawrence to

be shot to pieces; he had to abandon

it for the Niagara (a most

daring shift in a small boat), which had not

given him the support expected. Before

the Lawrence could be boarded by

the British, Captain Barclay had to

strike his colors. He had lost the com-

mander of every one of his vessels, the

second in command of the Queen

Charlotte, and was himself twice wounded. In all he suffered 41

killed and

94 wounded; Perry's loss was 27 killed

and 95 wounded--83 of the casual-

ties on board the Lawrence. A

fillip was given the American hard-earned

victory by Perry's laconic message to

General Harrison: "We have met the

NOTES ARE ON PAGE 260

222 OHIO HISTORY

enemy, and they are ours--two ships, two

brigs, one schooner and one

sloop."

It was a tremendous victory for the

Americans, opening the way for the

recovery of Detroit and the invasion of

Canada. Perry cared for Barclay

at Put-in-Bay and the two became

friends. When he was able to travel, the

Englishman was paroled and made his way

to Quebec, where early in 1814

the populace presented him with an inscribed

piece of silver. He was

similarly honored in London by the

Canada merchants there. But like all

captains who lost their ships he had to

undergo court-martial. He was tried

in Portsmouth harbor in September 1814

and was "most fully and most

honorably acquitted."1

Barclay was not actually a captain in

rank. He was a commander, a rank

midway between lieutenant and captain.

Since he commanded a ship on

Lake Erie he was in fact a captain and

was so addressed. Actually he

should have been called by courtesy a

commodore, like Perry, who was only

a lieutenant in rank, because he

commanded a squadron. But Barclay's

superior, Sir James Yeo, was only a

commodore. Barclay was still a young

man. He was born in Scotland in 1784 or

1785, and testified in 1813 that

he had been sixteen years in His

Majesty's service. Reputedly he served

under Nelson at Trafalgar in 1805 and

lost an arm, although one account

suggests that he lost the arm later. He

had been sent to Bermuda early in

1813 and then in May to Canadian waters

with some veteran junior officers

and a corps of fifty British seamen,

where he came under the command of

Commodore Yeo. Command of the little

squadron on Lake Erie was offered

to Commander William Mulcaster, who

refused it because he thought it in a

poor state and undermanned. In

consequence, Barclay was ordered to Lake

Erie to take command with twenty-five

men, twelve of them Canadians.

The Detroit was under

construction, and Barclay pleaded with Yeo for

more crewmen. He was sent only Captain

Robert Finnis, but was promised

more. Provisions were diminishing at a

fast rate for Procter's army and

his numerous Indian allies. Finally in

September with everyone on reduced

rations, Procter advised Barclay that he

would have to risk battle in order

to get supplies. To make up his deficit

of men, Procter gave him soldiers

to serve as marines. If more sailors

were coming, Barclay could not wait

for them. Hence he sailed to disaster.

By the time the court-martial was over,

the British naval force on Lake

Champlain had taken a lacing from

Commodore Macdonough and peace

negotiations were in progress. The

treaty of Ghent was signed on December

24, 1814. Barclay's reputation seemed to

be unsullied, but unfortunately

his name became involved in a political

clash in parliament. In November

COMMODORE PERRY'S CAPTIVE 223

the Duke of Buckingham (then a marquis)

asked in the house of lords

for the court-martial proceedings

against Barclay, not to dispute the verdict

but "to shew the inadequacy of our

force on the Lakes at the time."2 To his

surprise the navy office refused, on the

ground argued by Lord Melville, first

lord of the admiralty, that the story

was incomplete without the current

court-martial of General Procter and an

explanatory letter from Sir James

Yeo critical of Barclay's having ever

left Amherstburg(!), both of which

were daily expected. The Earl of

Bathurst now muddied the water by

declaring that nothing should be spread

on the journals of the house that

was prejudicial to the military and

naval service of the country. He even

blamed Barclay for seeking a battle with

an inferior force, which confused

the issue by questioning the decision of

the court-martial. Lord Grenville

declared the real suspicion was that the

admiralty had failed to equip and

man the Lake Erie flotilla and now

wanted to hide its dereliction. After

these exchanges and upon the

understanding that Melville would produce

all the documents in the near future,

Buckingham withdrew his motion.

Now that a question had been raised, the

Earl of Darnley moved next

day that various papers he specified be

produced by the naval office con-

cerning its conduct of the war in

America, including supplies to Canada.

The motion passed. Obviously the

opposition was looking for a scapegoat

for Britain's poor performance in the

war with the United States. Suspicion

spread.

In the house of commons on December 1,

Mr. Horner asked for an

accounting of the vessels on the lakes

of Canada and for the court-martial

of Barclay. He was persuaded to delay

the second request. Mr. Whitbread

accused the ministry of wanting to elude

an inquiry, "as if afraid their

guilt would come out."3 Nevertheless,

the matter was delayed until after

the Christmas recess and the signing of

the peace treaty. When parliament

reconvened in February 1815, Lord

Darnley renewed his motions, including

a request for the minutes of Barclay's

court-martial. Melville now denied

that British ships were insufficiently

manned, but admitted they did not

have the "picked men"

available to the Americans! Further debate seems

to have dissolved under the cloud of

Napoleon's escape from Elba and

the approach of a climactic campaign.

All that remained, apparently, was

rancour in the mind of Lord Melville

that associated the opposition's

needling with the name of Captain

Barclay.

Seven years went by and Barclay remained

a commander in rank and

without a ship. He now felt himself

unjustly neglected and prepared to

take action toward gaining promotion. In

a long letter dated at Edinburgh,

February 13, 1822, to his friend Sir

John James Douglas, Barclay said:

224 OHIO

HISTORY

I have been for some time considering of

the propriety of making some sort

of application to the Duke of Buckingham

to see if he could now obtain for me

that promotion which he, by motion and

speech in the house of Lords (in con-

junction with Mr. Whitbread doing the

same in the house of Commons) in 1814

on the subject of my defeat upon Lake

Erie was accessory to being withheld

from me.

Barclay was crediting the duke with a

larger role than he had innocently

played; Lord Darnley had been more the

gadfly. It was true that Samuel

Whitbread had stung the admiralty, but

was unavailable now because he

had committed suicide in 1815.

Furthermore, Yeo was also dead. Anyway,

Barclay was now asking Douglas to

explain the situation to the Duke of

Buckingham, confident that if the duke

would speak to Lord Melville the

delayed promotion would be made of

"an officer who had been, both by

friends and foes, admitted to have done

his duty with zeal and courage

proportioned to the difficulty of the

most arduous service committed to his

charge," Barclay modestly

concluded. To refresh Douglas' and the duke's

recollection of the event, Barclay enclosed

copies of two documents. One was:

Extract of the general order issued by

Lieut. General Sir George Prevost Bart.,

Governor General of the Canadas &c

on the defeat of His Majesty's Squadron

on Lake Erie under the command of Capt.

Robert Heriot Barclay in Septr. 1813.

[The late Governor Prevost had censured

Procter for his retreat and defeat at

the battle of the Thames in October

1813.]

His Excellency considers it an act of

justice to exonerate most honorably from

this censure the brave soldiers of the

right division of the army, who were

serving as marines on board the squadron

on Lake Erie. The commander of

the forces having received the official

report of Capt. Barclay, of the action which

took place on Lake Erie on the 10th

Septr., when that gallant officer from circum-

stances of impelling necessity, was

compelled to seek the superior force of the

enemy and maintain an arduous and long

contested action under circumstances

of accumulating ill fortune.

Capt. Barclay represents that the wind,

which was favorable early in the day,

suddenly changed, giving the enemy the

weather gage, and that this important

advantage was, shortly after the

commencement of the action, heightened by

the fall of Capt. Finnis, the commander

of the Queen Charlotte, in the death of

that intrepid and intelligent officer

Capt. Barclay laments the loss of his main

support. The fall of Capt. Finnis was

soon followed by that of Lieut. Stokoe

whose country was deprived of his

services at this very critical period, leaving

the Queen Charlotte in the command of

Provincial Lieut. Irvine who conducted

himself with courage, but was limited in

experience to supply the place of such

an officer as Capt. Finnis, and in

consequence this vessel proved of far less assist-

ance than might be expected.

The action commenced about a quarter

before 12 o'clock, and continued with

great fury until half past two, when the

American commodore quitted his ship,

COMMODORE PERRY'S CAPTIVE

225

which struck shortly after to that

commanded by Capt. Barclay (the Detroit).

Hitherto the determined valour of the

British squadron had surmounted every

disadvantage, and the day was in our

favor; but the contest had arrived at that

period when valour alone was

unavailing--the Detroit and Queen Charlotte were

perfect wrecks, and required the utmost

skill of seamanship, while the com-

manders and several officers of every

vessel were either killed or wounded, and

not more than fifty British seamen were

dispersed in the crews of the squadron,

and of these a great proportion had

fallen in the conflict.

The American Commodore made a gallant

and but too successful effort to

regain the day; his second largest

vessel, the Niagara, had suffered little, and

his numerous gunboats, which had proved

the greatest source of annoyance,

were comparatively uninjured.

Lieutenant Garland, 1st lieut. of the

Detroit, being mortally wounded previous

to the wounds of Capt. Barclay obliging

him to quit the deck it fell to the lot

of Lieut. Inglis, to whose intrepidity

and conduct the highest praise is given,

to surrender His Majesty's ship, when

all further resistance had become un-

availing.

The enemy by having the weather gage

were enabled to choose their distance,

and thereby avail themselves of the

great advantage they derived in a superiority

of heavy long guns. But Capt. Barclay

attributed the fatal result of the day to

the unprecedented fall of every

commander and second in command, and the

very small number of able seamen left in

the squadron at a moment when the

judgment of the officers and skillful

exertions of the sailors were most eminently

called for.

To the British seamen Capt.

Barclay bestows the highest praise, "That they

behaved like British seamen." From

the officers and soldiers of the regular

forces, Capt. Barclay experienced every

support within their power, and states

that their conduct has excited his

warmest praise and admiration.

Deprived of the palm of victory when

almost within his grasp, by an over-

whelming force which the enemy possessed

in reserve, aided by an accumulation

of unfortunate circumstances, Capt.

Barclay and his brave crew have by their

gallant daring and self-devotion to

their country's cause, rescued its honor and

their own even in defeat.

(Signed) Edward Baynes

Adjt. General

Although mistaken about Perry's

superiority in long guns, Prevost's sum-

mary is reasonably accurate. The second

document was a copy of an excerpt

from the "Court Martial assembled

on board His Majesty's ship Gladiator

in Portsmouth Harbour on the ninth day

of September 1814." After listing

the officers who served as members of

the court and exhibiting the charge,

namely the capture of Barclay's

squadron, the proceedings continued:

The Court proceeded to inquire into the

cause and circumstances of the capture

of His Majesty's late squadron and to

try the said Captain Robert Heriot Barclay,

his surviving officers and seamen late

belonging thereto for their conduct on

226 OHIO

HISTORY

that occasion, and having heard the

evidence produced and compleated the

inquiry and having maturely and

deliberately weighed and considered the whole,

the court is of opinion that the capture

of His Majesty's late squadron was caused

by the very defective means Captain

Barclay possessed to equip them on Lake

Erie, the want of a sufficient number of

able seamen whom he had repeatedly

and earnestly requested to be sent to

him, the very great superiority of the enemy

to the force of the British squadron,

and the unfortunate early fall of the superior

officers in the action; that it appears

that the greatest exertions had been made

by Captain Barclay in equipping and

getting into order the vessels under his

command; that he was fully justified

under the existing circumstances in bringing

the enemy into action; that the judgment

and gallantry of Captain Barclay in

taking his squadron into action and

during the contest were highly conspicuous

and entitled him to the highest praise;

and that the whole of the other officers

and men of His Majesty's late squadron

conducted themselves in the most

gallant manner; and doth adjudge the

said Captain Robert Heriot Barclay, his

surviving officers and men to be most

fully and most honorably acquitted

accordingly.

Signed by the Court.

The court was mistaken about "the

very great superiority of the enemy,"

but that is not the question here. It

did reflect on Yeo and the admiralty

office. Whatever Douglas did or did not

do, he apparently did not approach

the Duke of Buckingham, for on May 22,

1822, Barclay wrote again to

Douglas advising him on the favor asked:

My friend Col. Macdonnell has succeeded

in bringing me to the notice of the

Duke of Buckingham through his brother

and [!] law Lord Arundell. His grace

perfectly recollects the affair, and has

expressed very great regret at the evil

consequences his interference had,

unintentionally upon his part, brought upon

me; and that he will be happy to serve

me in any future application I make to

Lord Melville. That is my will as far as

it goes; but you know the difficulty is

how to bring an application to bear upon

Lord Melville, without renewing the

feeling, which is pretty well laid now,

which formerly operated against me in

the mind of Lord Melville. I have

therefore written a fully explanatory letter to

Macdonnell, one which he may shew to Lord

Arundell, and I have pressed upon

him that it would be best that the Duke

should feel fully convinced in his own

mind that he was the cause, and that he should not allude in

any way to politics,

but make his request to Lord Melville a

personal favor; as an amends due from

him, the Duke, to me whom, tho' in

ignorance, he has deprived of promotion.

If therefore you have access to His

Grace, pray try him on that tack also, because

his pride as well as his honor will be

enlisted in the cause, for it seems he piques

himself on the nobleness of his nature

& manly character. I have no kind of

doubt, but that he will succeed, if he

earnestly sets about it, & with Lord Arundell

on the one hand, and your friends on the

other he cannot fail in being engaged

heartily in the cause.

COMMODORE PERRY'S CAPTIVE 227

It would seem that Barclay was asking a

good deal of the innocent duke,

who had not been the primary critic of

the admiralty in 1814. Whether

Buckingham did intervene with Lord

Melville is not known, but something

happened. Still holding the old rank of

commander, Barclay was given

command of the bomb vessel Inferno (75

crew) on April 12, 1824.

Possibly it made a short cruise, but six

months later, on October 11, it was

paid off.4 Three days later,

according to the Navy List, Barclay was pro-

moted to post captain, which was duly

reported in the Gentleman's Magazine

for January 1825 (p. 79). Post captain

was a real rank, entitling the

holder to command a ship, and was

distinct from the temporary or courtesy

rank of captain that might be extended

on special occasion. However,

although Barclay was not yet forty, the

admiralty continued to leave him

ashore.

He died a dozen years later on May 8,

1837, aged fifty-two. No account

of him is found in the Dictionary of

National Biography. His battle on Lake

Erie is noticed in William James, Naval

Occurrences of the Late War

(London, 1817) and in Capt. Edward P.

Brenton, The Naval History of

Great Britain (London, 1825), Volume 5.

THE AUTHOR: Howard H. Peckham is the

director of the William L. Clements

Library

at the University of Michigan.

(614) 297-2300