Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

|

|

|

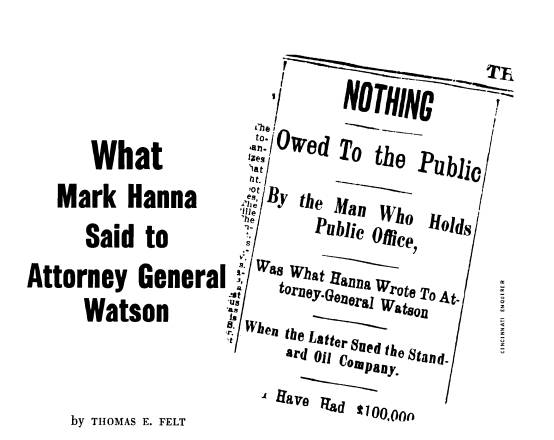

"You have been in politics long enough to know that no man in public office owes the public anything." In these or closely similar words, Mark Hanna is alleged to have advised the attorney general of Ohio in 1890 to drop an antitrust suit against the Standard Oil Company.* Historians looking for a succinct illustration of how the late nineteenth century's robber barons and their vassals operated in the political field have found the alleged remark invaluable. It first did duty in the Democratic campaign against Hanna's election to the senate in 1897. Ida Tarbell used it in her History of the Standard Oil Company in 1904. Two years later it appeared in Harry Thurston Peck's influential Twenty Years of the Republic. The following generation of readers would find it in Matthew Josephson's persuasive The Robber Barons (1932), and elsewhere, while today it reappears in an occa- sional college text--and probably more frequently in classroom lectures-- as well as in a recent paperback reissue of the Josephson book.1 Since neither of Hanna's early biographers categorically denied that he expressed the sentiments in question, the essential legitimacy of the quotation has never been attacked.2 NOTES ARE ON PAGE 344 |

294 OHIO HISTORY

Marcus Alonzo Hanna was an unfamiliar

name outside Ohio political

circles in 1890. Not until he had

succeeded in managing the campaign of

his friend William McKinley for the

Republican presidential nomination

in 1896 did his words and deeds begin to

win a national audience, and not

until even later was he regarded as

having come "closer to being a national

Republican boss than any figure in the

lore of American politics."3 In 1890

Hanna was merely a Cleveland

businessman--in mining, ore fleets, ship-

building, street railways, and a

bank--who had been throwing his weight

around in the state Republican party for

the last six years with notable

effect. For a time he had befriended

both the ambitious young governor,

Joseph B. Foraker, and the veteran

senator and presidential prospect, John

Sherman. As leader of the Sherman forces

at the national convention of

1888 he had met a defeat he blamed in

part on Foraker, and since then

these two had squared off in a factional

fight that would continue the remain-

der of their lives. By the end of 1890

Hanna and his friends were in the

ascendant in Ohio Republicanism,

although the party itself was rapidly

losing ground to the Democrats there and

in the nation at large. The first

congress since Grant's day to support a

Republican president with a working

Republican majority had just been

repudiated at the polls. It was this

congress that had come to the voters for

judgment on two major statutes:

the McKinley tariff act, which is

usually blamed for the defeat, and the

Sherman antitrust act.

The source of Hanna's alleged maxim was

a letter which Hanna very

likely did write on the immediate

subject of the Sherman act and its Ohio

counterpart and on the more general

subject of what the Republican party

owed to the business community and the

public at large. Since, if Hanna

did write the letter, it represents one

of the most important expressions of

his views, it would seem worthwhile to

determine its authenticity. That no

original at present is known to exist

makes the problem more difficult, but

perhaps not impossible.

The story begins a few days after the

election. Hanna wrote a letter to

Ohio's attorney general, a young

Republican named David K. Watson. In

it he protested Watson's action of

several months earlier in bringing suit

against the Standard Oil Company for

violating its charter by transferring

control over its affairs to a trust

dominated by non-residents of the state.

Watson said later that when he received

the letter he casually permitted a

newspaperman, Francis B. Gessner, to

read it. No copy was made, however,

and the matter remained private.4 Watson

replied cordially but firmly that

he did not intend, as implied, an attack

on organized capital generally. The

|

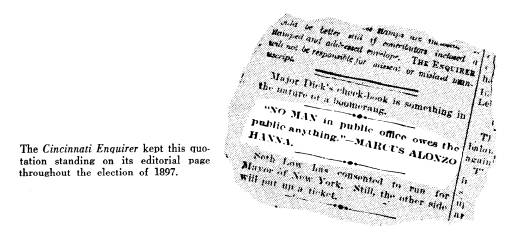

WHAT MARK HANNA SAID 295 facts of the case at hand made his action seem a matter of duty. Senator Sherman was not behind it, despite rumors that the suit was related to his antitrust bill then pending in congress.5 After a few weeks' delay, Hanna wrote again to urge his view that there has been no industry of greater benefit to our city [than Standard Oil], and there are large holdings among our enterprising business men. [His brother Mel was one of them.] They are indignant at this attack, and when the time comes will make their influence felt. Therefore I have said to you in all frank- ness that politically it is a very sad mistake, and I am sure it will not result in much glory for you.6 There the argument rested. The case proceeded and so far as is known Hanna said no more to Watson about it. Seven years later, as Hanna was campaigning for election to the senate, opposition newspapers all over the state blossomed out in great black letters with the following quotation, ascribed to Hanna: "No Man in Public Office Owes the Public Anything."7 Their source was an article in the New York World of August 11, 1897, written by the same Francis B. Gessner who had supposedly read Hanna's first letter to Watson years before. Now he reported the story, first checking with others who also claimed to have read the letter. He said that this sentence had stuck in his memory verbatim, along with the substance of the rest of the letter. "No one could read it and ever forget it," asserted the somewhat tardily shocked Gessner. Watson was besieged by reporters for confirmation, but beyond insisting that the extracts published were inaccurate he would add nothing. Then, |

|

|

296 OHIO

HISTORY

according to Watson's story, Hanna

asked him to return the letter. Watson

agreed. In a brief and somber ceremony

at the Neil House in Columbus, the

offending words were torn up and

flushed down the toilet, Watson pulling

the chain. The would-be senator was

contrite, and Watson was content, for

he had taken the trouble to make a copy

for himself.8

Nine years later James B. Morrow

interviewed Watson in the course of

his researches for Herbert Croly's

biography of Hanna. He took down the

story as related above, together with

some additional material on Watson's

efforts to prevent Ida Tarbell from

including the episode in an article for

McClure's Magazine. From his

own knowledge of Watson and Gessner

and from talking with Hanna's

secretary, Elmer Dover, Morrow doubted the

truth of the Watson version. But Watson

did give Morrow his alleged copy

of the destroyed letter, together with

a copy of his reply and the original of

Hanna's second letter. When Croly

published his biography of Hanna in

1912, he printed the Watson copy of the

first Hanna letter in full. The last

two pieces are still in the Hanna

Papers, but the copy of that first and most

important letter has disappeared. What

follows, then, is necessarily copied

from Croly's printing of Watson's copy

of the purported original letter of

November 21, 1890:

Some months ago, when I saw the

announcement through the papers that you

had begun a suit against the Standard

Oil Co. in the Supreme Court, I intended,

if opportunity presented, to talk with

you, and failing in the personal interview,

to write you a letter, but the subject

passed out of my mind. Recently while in

New York I learned from my friend, Mr.

John D. Rockefeller, that such suit

was still pending, and without any

solicitation on his part or suggestion from

him, I determined to write you,

believing that both political and business interests

justified me in doing so. While I am not

personally interested in the Standard

Oil Co., many of my closest friends are,

and I have no doubt that many of the

business associations with which I am

connected are equally open to attack. The

simple fact is, as you will discover, if

you have not already done so, that in these

modern days most commercial interests

are properly and necessarily taking on

the [this?] form of organization for the

safety of investors, and the improve-

ment of all conditions upon which business

is done. There is no greater mistake

for a man in or out of public place

to make than to assume that he owes any duty

to the public or can in any manner

advance his own position or interests by attack-

ing the organizations under which

experience has taught business can best be

done. [Italics supplied.] From a party standpoint, interested

in the success of

the Republican party, and regarding you

as in the line of political promotion, I

must say that the identification of your

office with litigation of this character is a

great mistake. There is no public demand

for a raid upon organized capital. For

years the business of manufacturing oil

has been done with great success at

Cleveland, competition has been open and

free, and the public has been greatly

WHAT MARK HANNA SAID

297

benefited by the manner in which the oil

business has been carried on. The Stand-

ard Oil Co. is officered and managed by

some of the best and strongest men in

the country. They are pretty much all

Republicans and have been most liberal

in their contributions to the party, as

I personally know, Mr. Rockefeller always

quietly doing his share. I think I am in

a position to know that the party in this

state has been at times badly advised.

We need for the struggles of the future the

cooperation of our strongest business

interests and not their indifference or

hostility. You will probably not argue

with me in this. I have been informed,

though I can hardly credit the information,

that Senator Sherman has encouraged

or suggested this litigation. If that be

correct, I would like to know it, because

I shall certainly have something to say

to the Senator myself. I simply say with

respect to this matter, that prudence

and caution require you to go very slow in

this business.9

The crucial sentence is the one

italicized. Croly was concerned also with

the second sentence prior to it, in

which Hanna suggested that some of his

own business connections were

"equally open to attack." Both of these state-

ments he found incredible. No matter

what Hanna might have thought

privately, he argued, he would never

have convicted himself of such "childish

folly" on paper. "Why, even if

he believed it," Croly asked, "should he be

cynical and incoherent enough to throw

in a remark that a public official

owes no duty to the public,"

especially when Watson was not a close friend

and would have good reason to be

offended by such talk. Croly concluded

that the letter itself had been tampered

with: "The suspicion which attaches

to the whole document makes it

impossible to accept absolutely any part of

it and base a criticism of Mr. Hanna

upon it." Nevertheless, Croly admitted

that much of the letter could have been

written as purported, and that there.

fore Hanna might have wanted it

destroyed in 1897 because he was ashamed

of it.10

Some suspicion may be cast on the

document, although it is cast in part

by biased witnesses. Hanna's secretary

in his senate days, Elmer Dover,

told some stories reflecting on Watson's

credibility: he had been rebuffed

by Hanna in his application for

financial aid in his 1896 congressional

campaign; he had presented a bill of

$250 for the expenses of a two-day

trip to mollify Ida Tarbell in New York;

and he had hinted to Hanna's

family that something might be done for

him for his services in keeping the

lid on the story as well as he did.11

Why the family might take that obliga-

tion lightly is apparent from a reading

of Gessner's story in the World.

Several aspects of it cast doubt on

Gessner's characterization of Watson in

1897 as an "intensely loyal"

McKinley Republican who would tell the

press nothing. Hanna's letter is

summarized, and its phrases, such as "organ-

298 OHIO HISTORY

ized capital," are quoted or

misquoted in the exact order in which they

appear in Watson's copy of the original

written seven years before. Then

too, the story suggests that Watson's

loyalty to his party might have been

under considerable strain in 1897. It

notes that after having been denied

effective help in his congressional

campaign for reelection in 1896 he was

defeated by forty-nine votes. Following

this, he had been disappointed in

his hope that the president-elect would

name him to a place on the interstate

commerce commission. Promised something

"equally good," he was still

waiting in August.12 So much

for Watson.

Gessner was under equally great

suspicion. Morrow, who had a wide

acquaintance among fellow newspapermen,

noted in his comments on the

Watson story that "even before

Francis B. Gessner became an outcast and

inhabitant of the gutter through drink

and drugs he was distrusted by news-

paper men who knew him in Ohio."

Behind this charge are some scraps of

contemporary evidence that still

survive. John Sherman traced down a false

news story in 1888 and found Gessner at

the bottom of it. He was known

then, Sherman reported hearing from a

newspaper friend, as a "common

liar" who had been "detected

in several similar matters."13 One year later

it appeared that Gessner may have been

turning over a new leaf. Foraker

addressed a letter to him in Detroit at

that time saying that he had written

a note of introduction for him to

Governor Russell A. Alger of Michigan.

"You will find Governor Alger a

very generous hearted man. He will take

a great deal of pride in helping a man

if he has confidence that he will stay

up. It gives me great pleasure to know

that you have come to a realization

of your mistakes and have formed a

determined purpose to redeem your-

self."14 Whether the

governor was satisfied with him thereafter is not in

evidence, but according to Watson,

Gessner was in his office in Columbus

six months later reading Hanna's

letter. Presumably he was at least a good

Republican then, for he kept the letter

in confidence. But in 1897 he was

contributing grist for the mill of the

Democratic New York World. In 1904

he is found again in the Republican

camp, this time writing the praises of

no less stalwart a party man than

Charles Dick, Hanna's successor in the

senate.15

Thus when Croly mentioned "the

suspicion which attaches to the whole

document," he must have been

thinking of derogatory reports on the charac-

ters of both Watson and Gessner as well

as of the "inexplicable" passages in

the letter itself. An alternate

explanation of the letter's history was given by

Morrow in his written comments on the

Watson interview, and by implication

this is the theory Croly accepts: Hanna

wrote a letter to Watson in 1890;

WHAT MARK HANNA SAID 299

Watson gave the substance of it, or

showed it, to Gessner in 1897 during the

heat of the campaign against Hanna, and

the two men conspired on the story

about Gessner's earlier reading of it in

order to cover their motives, since

Watson was afraid to oppose Hanna

openly. The original was destroyed to

satisfy Hanna, but a corrupted copy was

made and kept by Watson for use

should it become helpful later.

This seems an unnecessarily elaborate as

well as shaky defense. The first

part, covering the probable conspiracy

to hide Watson's motives is probably

true. But the more serious charge that

Watson falsified the letter reproduced

above by adding to it is both weak and

unnecessary. The sole excuse for it

is the belief that Hanna would not have

written what he was purported to have

written. It will be argued here that he

might well have written the entire

letter, "childish follies" and

all.

Mark Hanna in 1890 had none of the

politician's treasured skill in weigh-

ing his words. In the spring of that

year, for example, he had been caught

off guard by a New York newsman, and the

resulting "Foraker is dead"

interview fanned the embers of Ohio factionalism

to a blaze. He wrote his

mentor and leader John Sherman that

"what I said to him I am sure I am

not ashamed of. But I had not the most

remote idea that he was pumping

for an item. In that I plead guilty to

Capeller's charge of being a fool. I

certainly never aspired to being a

politician nor a boss as Mr. C. would

understand the terms."16

It might also be relevant that Hanna then and for

some years afterward had almost a phobia

against public speaking.17 He

disliked writing out a prepared text, and

he knew that his conversational

habit of pitching his thoughts

point-blank at his listeners could bring swift

embarrassment in the next day's papers.

It would be a long time before he

would develop that politician's sixth

sense of caution when exposing his

mind and heart to the public. His

written remark that he was no worse than

the men of Standard Oil may be

understood as only another spark in the

momentary heat of the occasion. He was

no legal shark. The slip was that

of a man morally certain, personally

indignant, and legalistically naive.

The second remark--the one italicized

above--is puzzling only because

it seems never to have been understood

for what it plainly says. It is a long,

compound-complex sentence, but it

expresses only one thought--the same

thought, essentially, that appears two

sentences later in the words, "There is

no public demand for a raid upon

organized capital." Watson was in politics

up to his eyes. He presumably had two

motives: to serve the public, and, in

doing this, to advance his own

interests, i.e., his career. Hanna was telling

him that he could accomplish neither of

these objects "by attacking the organ-

|

|

|

izations under which experience has taught business can best be done." This is not only the context of the thought; it is the thought itself. The thought that it is a mistake for a man to assume that he owes any duty to the public-- stopping there--is nowhere present.18 Hanna may have been right or wrong in what he did say, but the senti- ments he expressed were not atypical of him. His remark on the importance of supporting the leadership of businessmen was closely in keeping with dominant Republican attitudes toward the tariff act of 1890. It was part of the creed of a representative of the party that admitted of no differences between the best interests of the country and the best interests of the com- munity of business success. A prosecution such as Watson was undertaking |

WHAT MARK HANNA SAID

301

was a dangerous insistence on

technicalities. Had Hanna been alive sixty-

three years later he would have cheered

the answer of Secretary of Defense

Charles E. Wilson when Wilson was asked

by a senator whether as a former

president of the General Motors

Corporation he would feel able to make a

decision favoring the national interest

but detrimental to his old company's

interest. He could, he replied, but it

seemed an entirely hypothetical ques-

tion, "because for years I thought

what was good for our country was good

for General Motors, and vice-versa. The

difference did not exist. Our com-

pany is too big. It goes with the

welfare of the country. Our contribution

to the nation is quite

considerable."19 Wilson, too, found that his words

would cause him political embarrassment,

and he had not gone so far as to

draw any conclusions regarding the

proper attitude of the Republican party

toward his old company. At

least when he was later misquoted by hostile

politicians, the wrong words--"What

is good for General Motors is good

for this country"--expressed a part

of his thought. In Hanna's case, the

misquotation was of a different order.

He not only used slightly different

words but expressed an entirely

different thought.

In the story of the Republican party's

relationship to the Sherman act,

Hanna's letter is an early clue to later

policy. Its author represented the

views of a younger generation than John

Sherman's. He was growing up

with the combination movement in

business. Certain that many of his own

associations were "equally open to

attack," he looked to a future in which

big business would use its power to

bring new glories of American prosperity.

The men Hanna would represent as he rose

to national prominence over the

ensuing decade were a degree less timid

and naive than the authors of the

Sherman act.20 Their response

to political pressures for business regulation

gradually took a different turn. For a

time after the Republicans were

returned to power under McKinley,

prosperity, the gold standard, and a

small war served to cover a multitude of

omissions. Thus a recent scholar

has concluded that "during

McKinley's presidency antitrust enforcement

reached a new low watermark equaled

during no other period. The four

and a half years . . . witnessed the

institution of only three suits, all of them

civil."21 A more

creative response would appear later under the label of

the "New Nationalism," though

Hanna himself would make a contribution

as early as 1901. With his acceptance of

the presidency of the National

Civic Federation late in that year he

began an earnest search for a modus

vivendi between his older "associations" and the

countervailing power of

organized labor.22 These

"older associations," the targets of the Sherman

act, were in Hanna's view indispensable

incubators of economic statesmen.

302 OHIO HISTORY

The unions, under the leadership of such

prudent men as John Mitchell and

Samuel Gompers, were seen as having a

like capability. Conditions of

lasting peace and prosperity were to a

great extent considered subject to

negotiation between the leaders of these

great power blocs.

By late 1901, however, both John Sherman

and William McKinley had

passed from the scene. Before Theodore

Roosevelt would win the presidency

in his own right, Hanna, too, would be

dead. The Hanna who defended

John D. Rockefeller's oil trust in 1890

was sure only that enforcement of

the Sherman antitrust act and the state

laws akin to it were bad medicine

for the business community. He was less

sure as to why his attitude was

compatible with the public interest. Had

he been sure he would not have

let himself say either that there was no

public demand for regulation or that

"competition has been open and

free" among Cleveland oil refiners. But if

his logic was hazy, his faith was clear:

There could be no conflict of interest

between whatever made men like

Rockefeller succeed and what made Cleve-

land, Ohio, and the nation succeed.

In brief, it would appear that there is

more to Hanna's letter to Watson

than a cautionary word to the wise from

a provincial party boss. The only

reading of it consistent with the rest

of what is known about Hanna is as a

statement of faith rather than of

cynicism, or hypocrisy, or plain forgery.

Whether the faith expressed was a

realistic one is a question of a different

order.

THE AUTHOR: Thomas E. Felt is an as-

sistant professor of history at the

College of

Wooster. He is preparing a biography of

Mark

Hanna.

|

|

|

"You have been in politics long enough to know that no man in public office owes the public anything." In these or closely similar words, Mark Hanna is alleged to have advised the attorney general of Ohio in 1890 to drop an antitrust suit against the Standard Oil Company.* Historians looking for a succinct illustration of how the late nineteenth century's robber barons and their vassals operated in the political field have found the alleged remark invaluable. It first did duty in the Democratic campaign against Hanna's election to the senate in 1897. Ida Tarbell used it in her History of the Standard Oil Company in 1904. Two years later it appeared in Harry Thurston Peck's influential Twenty Years of the Republic. The following generation of readers would find it in Matthew Josephson's persuasive The Robber Barons (1932), and elsewhere, while today it reappears in an occa- sional college text--and probably more frequently in classroom lectures-- as well as in a recent paperback reissue of the Josephson book.1 Since neither of Hanna's early biographers categorically denied that he expressed the sentiments in question, the essential legitimacy of the quotation has never been attacked.2 NOTES ARE ON PAGE 344 |

(614) 297-2300