Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

|

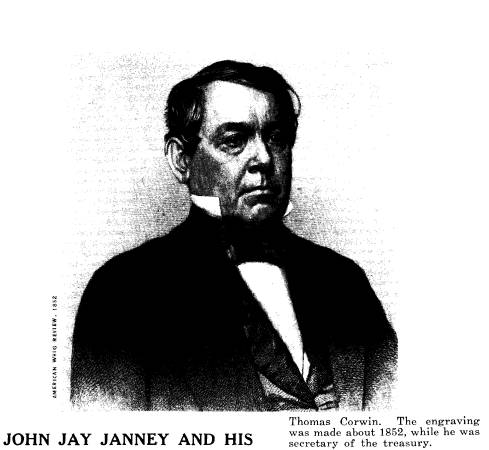

JOHN JAY JANNEY AND HIS "RECOLLECTIONS OF THOMAS CORWIN" edited by JAMES H. HITCHMAN It is a fortunate occurrence when the unpublished recollections of an able recorder like John Janney are preserved. His comments on Thomas Corwin afford an exceptional contemporary view of Ohio courts, lawyers, and politics in the 1830's and 40's and vivid personal reminiscences about the former governor's ability to influence people.1 Corwin's political career spanned the years from 1818 to 1865, the era of sectional conflict. He was in turn a National Republican, Whig, and Republican, who served his state successively as state legislator, congressman, governor, and United States Senator. Corwin also was secretary of the treasury in the Fillmore cabinet and minister to Mexico during Lincoln's first administration. A moderate, he opposed the Mexican War and he tried to reach a compromise with the seceding states on the eve of the Civil War. Corwin possessed a remarkably expressive face, a musical, far-reaching voice, and a rare sense of humor. He thought that his habit of finding the humor in any situation hampered his career, but it seems likely that his buoyancy endeared him to his constituents. As a lawyer he was considered NOTES ARE ON PAGE 131 |

RECOLLECTIONS OF THOMAS CORWIN 101

clever instead of learned, attaining

success in court because he knew how

to appeal to a jury. While not a church

member, Corwin nevertheless em-

phasized the use of Biblical phrases in

his speeches in order to achieve

greater effectiveness with his audience.

He was often in debt, because he

invested indiscreetly, became surety for

unreliable friends, or carelessly

collected bills. Corwin's chief traits

were a love of life, an irresistible

way with people, and zest for the gamble

and eminence of politics.2

His friend John Janney was well known in

Ohio during the middle

years of the last century. Prominent in

Columbus civic affairs, Janney par-

ticipated also in banking and railway

ventures. Although his charitable

work left a greater imprint, Janney's

activity in Whig and Republican

politics gave him state-wide and

national contacts with other men of

affairs.

Born on April 25, 1812, near Lincoln,

Virginia (known then as Goose

Creek Meetinghouse, Loudoun County),

Janney was raised a devout Qua-

ker.3 From his sixth to his fifteenth

year he attended the local Friends'

school. In his twentieth year he

matriculated at a day school in Alexandria,

where he studied "Euclid's

Elements" and "algebraic equations of the third

degree."

Sometime in the early 1830's,

"dissatisfied with slavery and its influ-

ences," Janney moved to Warren

County in southwestern Ohio.4 He lived

in the Quaker community of Springboro

for fifteen years, teaching, survey-

ing, and merchandising. He was also

clerk of the township for twelve years.

Activity with the local Whig committee

must have been creditable, be-

cause in 1844 he was appointed assistant

clerk in the Ohio House of Repre-

sentatives. Here Janney met most of the

leading men of the state.

In 1847, Samuel Galloway, then secretary

of state, appointed Janney

chief clerk in the office of the state

school commissioner. The following

year the Janney family moved to

Columbus. In 1850 he was elected secre-

tary of the board of control of the

State Bank of Ohio and worked in this

capacity until 1865.5 After one year as

assistant postmaster of Columbus,

Janney became secretary and treasurer of

the Columbus and Hocking Val-

ley Railway Company and performed his

duties until 1883. Elected several

times to the Columbus board of

education, he served two years as its treas-

urer. He was a director of the Ohio

Penitentiary during the Civil War, a

member of the state board of police

commissioners during this time, and

in 1867 held a place on the state board

of health. For many years Janney

was chairman of the Whig and Republican

city and county committees.

During the political campaigns of 1863

and 1864 he acted as chairman of

the state Republican committee.

Janney gave much of his energy to

benevolent projects. In both Spring-

boro and Columbus he was instrumental in

establishing a large number

of free schools and libraries. As chief

clerk to the school commissioner he

wrote an opinion which resulted in Negro

admission to public schools. He

aided in the founding of the Atheneum

library and reading room in Co-

lumbus. As a member of the city council

he was the author of the ordinance

|

passed in 1872 which created the Columbus public library and reading room. Janney enjoyed the opportunities he found in the Tyndall Society, Columbus Horticultural Society, Prisoners' Aid Society, and teaching in the Sabbath school of the Ohio Penitentiary. His consistent participation in good works also included speaking and writing on temperance. In 1835 Janney married Rebecca Anne Smith. They had three daughters and one son. Mrs. Janney died in 1886, but John Janney's long life did not end until December 11, 1907. Janney read and studied consistently, particularly in the natural sciences. He is remembered as a gentle, warm man, who adhered to his convictions and was reliable in all matters. He was especially helpful to young men starting their careers. His own career demonstrated a Quaker concern for morality in public life and faith in the judgment of the common man. John Janney observed an amazing span of American history. As a boy he watched Lafayette leave Thomas Jefferson's home. He heard John Quincy Adams speak and listened to Henry Clay. Janney knew William Henry Harrison, Salmon P. Chase, and Presidents Taylor, Lincoln, Grant, Hayes, Garfield, and McKinley. He regularly heard temperance and abo- litionist speakers, including Henry Ward Beecher, James G. Birney, and Joseph John Gurney. Other figures Janney either met or heard in Colum- bus were Ralph Waldo Emerson, Julia Ward Howe, Susan B. Anthony, Phillips Brooks, Edward Everett Hale, Booker T. Washington, and William Dean Howells. Of the many influential men known to Janney, Thomas Corwin must have had a special place in his memory when, near ninety, he set himself to writing the "Recollections" which follow. They are reproduced as he wrote them, with only an occasional word which he omitted supplied in brackets. |

RECOLLECTIONS OF THOMAS CORWIN 103

Recollections of Thomas Corwin

I came to Ohio in October 1831, and

lived in Springboro, Warren County

fifteen years. Mr. Corwin lived in

Lebanon, and I heard him speak in the

fall of 1832: but from that time on to

his death, I heard him speak a great

many times. I have listened to a number

of the great orators of the coun-

try, and I have never heard one who had

so complete control of an audience.

He always quit while the audience wished

him to continue.

In conversation with three young men who

were studying law, one

asked him what they should read in

addition to their law studies. He re-

plied, somewhat to their surprise,

first, read the Bible. Read it, not alone

because of the religion in it, but read

it for its literature. You will find

many things in it which you can't

believe, and others that you should not

believe; but you will find in it more

for the good of mankind and its happi-

ness than you will find in any other

book. Read it so as to become familiar

with it, or else you will find

yourselves frequently at a loss in company,

that will annoy you. Read it so as to be

able to quote it and refer to it

readily, for no matter what subject you

may talk about you can get more

illustrations of your subject from it

than you can find in all your other

reading.

I never listened to a public speaker

outside of the pulpit who made as

much use of the Bible as Mr. Corwin. As

an illustration: at a Whig meet-

ing at Waynesville, where there were

about two hundred of the farmers

of the neighborhood present, he took for

his stand the chopping block in

a pork house, and for his text

Nebuchadnezzar and compared him and the

Democratic party. He traced the history

of the party and Nebuchadnezzar

and left them both eating grass. One

good old man came to me, after

listening to the speech, and said to me

very soberly, "Isn't it a pity Corwin

was not made a preacher!"

On another occasion in referring to some

advocates of the Democratic

party who were office holders under it,

he would quote something they

had said, and then with an expression of

countenance that would convulse

an audience without a word being spoken,

he would say in an inimitable

manner, "The ox knoweth its owner

and the ass his master's crib."

If he wished to enforce a point made, he

would do it with an apt quota-

tion from the Bible.

I have heard him on politics, at the bar

and on the platform. I served

on the petit jury at Lebanon during a

five weeks term of court, and Mr.

Corwin was on one side of several

important cases that were tried; and

while the lawyers of the State never

considered him one of the great law-

yers of the state, that experience made

me believe that his knowledge of

the law was very good and his use of it

very effective; for his positions

were uniformly sustained by the court.

And he gained all his cases during

the term.

The Lebanon bar was at that time thought

to be, by many, the strongest

bar in the state, and with the addition

of Robert C. Schenck of Dayton,

Aaron Harlan of Xenia and L. D. Campbell

of Hamilton who practiced

there, it was undoubtedly so in fact.

One of the most enjoyable opportunities

afforded during that term of

court was that immediately after dinner

the lawyers would return to the

court house and spend half an hour or an

hour in telling stories. Corwin

was the leader, but "Bob"

Schenck was a good second. Mr. Corwin was

not at all backward in telling stories

illustrating our jury system, for

104 OHIO HISTORY

which he had very little respect. One I

have heard him tell several times.

When he first commenced the practice he

formed a partnership with an

old lawyer in Dayton. The first case

they had was for robbery. A man

was seen to fall, drunk, into the

gutter. Rain had just fallen and it was

then freezing. Two men were seen to go

to the drunken man, take his

pocket book out of his pocket and walk

away with it. Immediately after

two men went to the help of the drunken

man and in raising him from

the ground they found his coat frozen

fast to the ground, and in lifting

him they tore his coat. Mr. Corwin said

he noticed that in the cross exam-

ination of witnesses his old friend had

been very careful to get before the

jury all the facts about the man being

fast to the ground and the tearing

of his coat.

When the prosecuting attorney had opened

the case and made his plea,

the old gentleman turned to Corwin and

asked him if he wished to address

the jury, to which he replied he hardly

knew what to say in such a case.

Well his friend replied, if you do not

wish to say anything I'll take the

case.

He had a pile of authorities on the

table before him so high that he

could just see the court over them. And

he commenced by reading numerous

authorities defining real estate,

showing that anything that is attached to

the ground is part of the real estate. A

post set in the ground, a board

nailed to that post or a shingle fastened

to the roof by a single nail were

every one a part of the real estate.

He then read equally profuse authorities

defining theft and robbery.

And this he followed by equally luminous

and voluminous authorities upon

the subject of trespass.

He then argued that an action for theft

nor larceny nor robbery could

not be against these men because the man

they are accused of robbing

was not subject to robbery, because he

was at the time as had been clearly

established by the witnesses of the

state, part and parcel of the real estate,

he was fastened to the ground. The only

action that could lie against these

two men was an action of trespass, and

these men must go free.

Corwin said it was to him one of the

most amusing comedies he had

ever heard, but in a few minutes the

jury took all the fun out of it by

returning a verdict of not guilty.

Another case at Hamilton was equally

interesting. A man was indicted

for murder, by stabbing a man in the

right breast. The testimony as to

the stabbing was positive, but no

witness was willing to say whether it

was on the right or the left breast, it

was so near the center they could

not say on which side. A lawyer who had

been on the bench many years

was for the defense, and Mr. Corwin said

the jurymen had heard him so

often expound the law from the bench

that they received his application of

it in a trial just as they used to from

the bench. He read authorities, show-

ing that an indictment must be made good

literally, and that had not been

done. The indictment was for stabbing a

man in the right breast and no

witness was willing to say on which side

of the breast the stabbing was

done, it was so near the center they

could not decide, therefore the crim-

inal must be discharged, because the

indictment was not sustained by the

testimony. And Mr. Corwin said that in less than ten

minutes the jury

returned a verdict of not guilty.

RECOLLECTIONS OF THOMAS CORWIN 105

Mr. Corwin would tell similar stories

for an hour, illustrating the un-

certainty of jury trials.

My seat as juryman was so that Mr.

Corwin stood directly in my front.

I said to him one day that I should have

to change my seat or ask him to

reduce the number of his stories. I had

been qualified to decide cases of

dispute between neighbors, and I doubted

whether it was dignified to be

roaring with laughter at his stories. He

answered "Ah! Janney I don't

care whether you hear my stories or not.

I don't tell them for you at all:

but there is -- one side of you and --

on the other side. If you have any

doubt as to how they will receive a

proposition you are about to state, tell

them a good story, and while their

mouths are open laughing, they will

swallow anything you put at them."

One evening when Mr. Corwin and several

other lawyers were at the

hotel hearing and telling experiences,

he started up, looking at his watch,

said to the others, "We are a

committee to examine some young men for

admission to the bar, and they were to

meet at my office, and it is now

time." And turning to me he said

"come along Janney." At that time

there was not such an abundance of law

schools as now, but a young man

would study in some lawyers office,

under his instructions, and when

thought fit, would make application to

the Supreme Court, when in ses-

sion, when their application would be

referred to committee, upon the

favorable report of which they would be

admitted. One judge of the Su-

preme Court held a session in every

county in the state once every year.

On our way over from his office, after

the examination, I said to Mr.

Corwin "Was that a good and

sufficient examination you gave those young

men?" "Oh yes, it was a very

thorough and satisfactory examination. Why!

have you any fault to find with

it?" "Well no: but it was not exactly such

an examination as I expected to hear: I

have not studied law, but aside

from the pleading and forms of

proceeding, I think I could have answered

very nearly all the questions

asked." "Well now Janney you are asking en-

tirely too much. Did you expect me to

ask those young fellows any ques-

tions you could not answer? You were asking

too much entirely."

Some of the best speeches he ever made

were not reported. There was

a Colonel James Sweney living in the

neighborhood, who seemed to feel

his mission to be to make the Quakers of

the neighborhood "muster" or

pay their fines. They were all duly

enrolled and formed into companies,

but all refused to "muster."

The colonel once ordered a battalion muster

at Ridgeville, very near the center of

the Quaker settlement. Just as he

had got his forces in line, and guards

set around the field, three young

men, well mounted, every one with a good

"cow hide", leaped the fence,

and made chase for the colonel, one on

each side and one in the rear, and

by a vigorous use of their raw-hides

they started him round the field,

and, if my memory is not at fault they

rode him round the field twice, and

then leaped the fence again into the

road. Not only the spectators, but a

large per cent of those in line, roared

and shouted. While there was a small

number who were in sympathy with [the]

colonel, many who "mustered"

did so rather than pay their fine. The

enjoyment of the race was nearly

unanimous. To add to its ludicrous

character the colonel was an awkward

rider, riding with his stirrups too

short, his knees drawn up and his elbows

in the air: and he rode what used to be

known as a Chickasaw horse, a

106 OHIO HISTORY

serviceable kind of horse, but not at

all handsome. They were dappled in

color, sorrel, with small white spots

thickly set all over, and mane and

tail like a mules, almost hairless.

The colonel tried to have the boys

indicted for a riot. He could not

prosecute them for an assault, because

they did not strike him. They used

their cow-hides only on his horse. He

was unwilling to trust a magistrate

in the township in which the boys lived,

believing the Quaker influence

there would preclude a conviction; and

he therefore commenced proceed-

ings in a township where there were no

Quakers.

As soon as notice was served on the

boys, they went to Lebanon and

called on Mr. Corwin and asked him if he

would be at leisure on the day

set for trial. He said he had no

engagement; and upon being asked if

he would defend them, replied promptly,

"Yes boys, I'll be there." He

was evidently glad of the opportunity,

for he had a thorough contempt for

the whole system of militia training.

It having become generally [known] that

Mr. Corwin would defend the

boys, a large audience was present at

the trial. When examining the wit-

nesses Mr. Corwin was especially careful

to get a complete description

of that race round the field,

description of the colonel and his horse and

how he rode, and those who were present

said he got a very graphic

description of it.

I was [away] from home at the time and

did [not] hear the trial, but

many who were there and who had heard

Mr. Corwin many times said

his speech that day was the best one

they ever heard him make.

He would make an eloquent panegyric on

the government, closing it

with the reflection that it must have

power to protect itself in case of at-

tack. The time may come when the

constable and the sheriff may not be

able to protect or defend it; and he

would commend the colonel for his

efforts to organize and drill the

militia; but in doing so he should not

forget that there were some of the very

best men in the state who are

opposed to all military organization in

any form.

And then he would describe the colonel's

race around the field, giving

a minute description of the colonel's

horse and how he rode; first filling

his audience with enthusiastic love of

country, and then with uproarious

laughter at the colonel.

The boys were set free.

Mr. Corwin was a member of the Warren

County Colonization Society.

He was opposed to slavery, and in common

with the Whigs of that day,

was very much opposed to the fugitive

slave law. I heard him say that in

defending the North against an attack by

a Kentuckian because of our

unwillingness to return their fugitive

slaves he said to him, "You have

enacted a law, which [says], if I see a

bright mulatto girl, the daughter

possibly of some Kentucky gentleman and

a ruffian in full chase after

her, I must assist him. I give you fair

warning I'll obey no such law."

"Oh!" he said, "we don't

expect gentlemen to engage in that." "No! but

you pass a law which obliges me to do it

under penalty of fine and im-

prisonment in the penitentiary."

Mr. Corwin said that while he was a

member of Congress, whenever

the Colonization Society became badly in

need of funds the secretary

would call on him to raise some. On one

occasion, he was called on on

RECOLLECTIONS OF THOMAS CORWIN 107

Friday with the statement that the

society had a vessel ready to sail

from Baltimore on the next Monday

morning, and they had just heard of

another family of freed slaves ready to

go but they could not be sent with-

out a thousand dollars, and the

secretary came to him to raise it for them.

Mr. C. said that he felt sure the poor

negros would be better off, free

in Liberia than slaves here, but upon

asking the secretary to whom he

should apply for help he got no useful

reply. He started out on Saturday

morning and called on the rich members

of Congress but failed to get a

cent.

The secretary advised [him] to go to

Baltimore which he did. He there

called upon wealthy men to whom he was

referred with no better result.

At last when he [be] came disheartened

and disgusted, and had vented his

indignation to a friend at the

professing Christians who would not aid

their fellow beings in escaping from the

horrors of American slavery, his

friends suggested to him to call on D--,

who was a very prominent

patent medicine manufacturer whose

advertizement was in nearly all the

newspapers of the time. His friend said

the doctor makes no profession,

was a hard swearer, and might and

probably would curse you and the

Colonization society, but he is rich and

one of the most benevolent men

in the city. Mr. Corwin said he found

the doctor in a dimly lighted dirty

hole at the rear of his drug store; and

upon introducing himself, the

doctor said "Oh! I know who you are

Mr. Corwin and I am glad to meet

you " but upon stating his business

he burst forth in a torrent of abuse

of the Colonization society, saying it

was not intended to benefit the negro

at all, but the slaveholder, by getting

the free negro away so that he

should [not] demoralize their slaves.

Mr. Corwin said he concluded the

best thing he could do was to draw the

doctors attention away from the

Colonization society as quickly as

practicable, which he succeeded in

doing and had an hours very satisfactory

talk with him, and found him

to be a very intelligent and affable

gentleman. After an hour's talk, Mr.

Corwin took his hat and started for the

door, but the doctor said "How

much money did you say you wanted?"

"A thousand dollars." The doctor

took up his pen, wrote and handed to Mr.

C. a check for a thousand dol-

lars. And when Mr. C. thanked him for

it, he said, "Let the poor niggers

go to where they wont be persecuted as

they are here." And just as Mr.

C. reached the door the doctor said

"Corwin, if you find that is not enough

to send the niggers off, come

back;" and Mr. Corwin said he found more

Christianity in that man whom they all

thought a profane old heathen,

than I did in all the loud professors.

Seeing notice of a meeting of the Warren

County Colonization Society

at which Mr. Corwin would make an

address, I attended the meeting,

hoping to learn what the purposes of the

society were and how it pro-

posed to accomplish them. When the

business of the meeting was com-

pleted, Mr. Corwin was announced for an

address. Instead of commenc-

ing his address, he said he saw Mr.

Janney in the audience, and he would

be glad to hear from him. This surprised

and confused me, but I said I

came to hear and not to be heard, and I

came hoping and expecting to

hear from Mr. Corwin something that I did not, but

would be glad to know,

that was what the colonization society

proposed to do, and how it proposed

to do it. Mr. C. took me as the text for

his address and scored me for not

108 OHIO HISTORY

knowing what the Colonization society

was trying to do. I ought to have

known long ago. He made me the point of

his speech during the hour, but

he answered my inquiry.

A foul murder was committed near

Springboro while Mr. Corwin was

Governor. The murderer was convicted and

sentenced to be hung. A. H.

Dunlevy, a prominent attorney of Lebanon

said to me there had never been

a man hung in Warren County, and he

wished there never should be, and if

I would circulate a petition among the

Quakers, asking for a commuta-

tion of his sentence to imprisonment for

life, he would get signatures to

one in Lebanon. Upon the petition being

presented to Governor Corwin,

he said promptly "Certainly, I'll

commute the sentence. I think the state

of Ohio can make a better use of any man

than to hang him." The change

of the sentence was not made known to

the prisoner, nor to the public

until the morning set for the execution.

I was living in Springboro at

the time, and very early in the morning

people commenced passing through

town, on horse back and in vehicles,

some of them living twenty miles

from Lebanon, on their way to see the

execution. In the afternoon they

were seen returning sadly disappointed

by their failure to see a man

hung.

One of the most enjoyable rides I ever

had was from Waynesville to

Columbus. The only means of public

conveyance then (1842) was the

stage. There was an opposition [line]

from Wheeling to Cincinnati and,

as part of their equipment they ran some

two horse, four passenger

coaches. One of these passed Waynesville

just at dusk, and on entering it,

I found Thomas Corwin and George J.

Smith occupying the front seat,

and we three rode to Columbus during the

night.

I was going to attend a Washingtonian

temperance convention on Feb-

ruary 22nd. On learning that, Mr. Corwin

said to me you are right. I

started out in the same way; and it is

the proper thing for a young man

to do. I saw there were a great many men

who were throwing away their

lives by drunkenness and debauchery, and

I felt it to be a duty to teach

them better; and I made temperance

speeches and did what I could to

teach them; but I concluded, after

awhile, that I was not making any

impression on the public mind and there

seemed to be so many who were

determined to go to the Devil and the

public seemed entirely willing to

let them go. I concluded that they might

go and be damned if they wanted

to, and I would take care of myself. But

he added you are not doing right.

You pick up some drunkard out of the

gutter, make him wash his face,

put clean clothes on him and put him on

the platform as a fearful exam-

ple. A rare case may be worth the

saving, but a man has no more right

to get drunk than he has to steal my

purse, and should be imprisoned

for the one as surely as for the other,

and if he will not keep sober, keep

him at work.

During the ride we talked about almost

everything and if talk flag [g] ed

at any time Judge Smith knew where and

how to touch Mr. C. He

would simply ask him if he had met Mr.

-- lately, giving the name of

some eccentric acquaintance, and that

would start him on anecdotes about

him that would keep us laughing half an

hour or more.

As an illustration of his power to

influence men let the following show.

He was a member of Congress in 1840,

when General W. H. Harrison

RECOLLECTIONS OF THOMAS CORWIN 109

was a candidate for President. General

Crary of Michigan had made a

mean and wholly unjustifiable attack on

the military character of Gen.

Harrison. The next day Mr. Corwin

replied to it, in a speech which is a

classic in ridicule. I heard Mr. C. say

that upon his nomination as a

candidate for governor, on his way home

from Washington, he had as a

fellow passenger in the stage, a man who

engaged in a violent and ran-

corous attack on him for his reply to

Crary. There was no one in the

stage who knew Corwin, and he led the

man on to say all the hard things

about him that he could command. Mr.

Corwin said when they reached

Ohio he began to tremble with the

apprehension that someone would

recognize and reveal him, and whenever

the stage stopped he made himself

as small as he could in the corner; but

when they stopped at St. Clairsville,

and the door opened the first man he saw

shouted out "How do you do Mr.

Corwin." His critical companion

looked aghast and with a good deal of

astonishment said "Are you Tom

Corwin." "Yes sir, that's the name I'm

known by at home. Now tell me

yours." His name and residence were given,

and Mr. C. recognized him as a prominent

Democrat from the northwest

part of the state. He tried to excuse

himself for what he had said but

Corwin told him not to try that, for he

was glad to know what they thought

of him. Mr. Corwin commenced talking in

his inimitable way, and when

they separated, the man said to him

"Mr. Corwin, you are a candidate for

Governor of Ohio." "Yes sir,

so they tell me." "Well I'll vote for you."

And Mr. Corwin said he had learned he

did so, and again two years after-

wards.

Mr. Corwin had a power of facial

expression beyond any other person

I ever knew. He would utter a sentence,

and stopping short, would as-

sume an expression of countenance which

would convulse the audience

with laughter or fill its eyes with

tears.

He had quite a swarthy complexion. At

one time, when the abolition-

ists began to attract public attention,

it was not at all uncommon to have

a question put to a Whig speaker. At a

meeting one day while Mr. C. was

speaking some one in the audience asked

a question which I do not now

remember. But it bore on the rights of

the negro. Corwin stopped and

looking at the questioner with a mixed

and very peculiar expression said

"Do you think you ought to ask a

man of my color such a question as

that?" That put the audience in

such a mood that it shut off all further

interruption.

I was once present with Mr. Corwin when

some of his friends were

expressing their gratification for his

election as Governor. He said they

overestimated the honor of being

Governor of Ohio. The framers of the

constitution stripped the Governor of

Ohio of all power and made him

a mere dummy to fill the Governor's

chair. He has nothing to do but to

sign some deeds for canal lands sold,

commissions for Justices of the

Peace or Notaries Public and appoint a

colored brother to make the fires

and sweep the office: and pardon

Democrats out of the Penitentiary. If

you are looking forward to great honor

from the office, you are wrong.

At another time I heard Mr. Corwin

express the opinion that at a time

of great stress he doubted the

willingness of the people to come to the

help of the government, and hence he

feared it would lack power of self-

preservation; and he was satisfied that

was the opinion of a large

110 OHIO HISTORY

number of its founders. He said he had

just seen evidence that Oliver

Ellsworth was among the doubters. He

lived long enough to see the error

of such an opinion, for he lived through

the Rebellion.

Sam. Adams' grandson in the life of his

grandfather says, "Samuel

Adams, unlike Hamilton, Gouverneur

Morris, John Adams, Ames and

other of the Northern Statesmen, never

lost faith in the capacity of the

'common' people to govern

themselves."

Mr. Corwin possessed the ability to make

an anecdote to suit the case,

if he could not recall just the right

one for his purpose. It was a dangerous

experiment to interrupt him in any way

during a speech.

I have heard him tell the following: He

and Dan. Jennifer of Mary-

land were members of the House at the

same time. Jennifer, in common

with many eastern editors and orators,

always kept himself loaded with

a bit of grandiloquence, which was

credited to some western orator. And

when it happened that Corwin and

Jennifer were at dinner together,

Jennifer would fire off some western

eloquence at Corwin. One day, after

Jennifer had fired his squib at the

west; Corwin said to him Jennifer you

come from Maryland I believe, from

Worcester County. (One of the

poorest counties in the state, between

the ocean and Chesapeake bay.)

Yes sir. Well, Mr. Corwin replied, we

have in Warren county, Ohio, a

very reputable intelligent farmer by the

name of Brown, Daniel Brown.

It happened a few years ago that he was

called as a witness before the

court. And as is customary, he was asked

his age, to which he answered

twenty one. The attorney said Mr. Brown,

you did not understand me I

presume. I asked how old you are. Well,

I answered you. I am twenty one

years old. At this the judge said, Mr.

Brown, the court does not under-

stand, I think I have known you about

that long. And when I first knew

you you were a full grown man. Yes, that's

true, but Judge I'll explain

it to you. I was born in Worcester

county Maryland, and lived there

till I was twenty one years old: but God

Almighty will never charge that

against any man; and I came to Ohio then

and have lived here just twenty

years, and am just twenty one years old.

And Corwin said he was never troubled by

Jennifer afterwards.

THE EDITOR: James H. Hitchman is

an instructor in history at Portland

State

College, Oregon. He is working on his

doctorate at the University of California,

Berkeley.

|

JOHN JAY JANNEY AND HIS "RECOLLECTIONS OF THOMAS CORWIN" edited by JAMES H. HITCHMAN It is a fortunate occurrence when the unpublished recollections of an able recorder like John Janney are preserved. His comments on Thomas Corwin afford an exceptional contemporary view of Ohio courts, lawyers, and politics in the 1830's and 40's and vivid personal reminiscences about the former governor's ability to influence people.1 Corwin's political career spanned the years from 1818 to 1865, the era of sectional conflict. He was in turn a National Republican, Whig, and Republican, who served his state successively as state legislator, congressman, governor, and United States Senator. Corwin also was secretary of the treasury in the Fillmore cabinet and minister to Mexico during Lincoln's first administration. A moderate, he opposed the Mexican War and he tried to reach a compromise with the seceding states on the eve of the Civil War. Corwin possessed a remarkably expressive face, a musical, far-reaching voice, and a rare sense of humor. He thought that his habit of finding the humor in any situation hampered his career, but it seems likely that his buoyancy endeared him to his constituents. As a lawyer he was considered NOTES ARE ON PAGE 131 |

(614) 297-2300