Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

|

COLLECTIONS AND EXHIBITS EARLY OHIO PAINTERS: THE PREWAR YEARS by DONALD R. MacKENZIE |

|

|

|

HIGHER standards in painting character- ized the pre-Civil War period of art in Ohio. Improved transportation encour- aged artists to travel, and almost every painter visited New York, frequently tour- ing Boston and Philadelphia as well. There, they had the opportunity to see a limited number of imported European paintings and a variety of notable Amer- ican works. Most established painters who desired it were able to manage a trip to the European art capitals. Such tours were often financed by prepaid commis- sions on future paintings or specific com- missions to copy Renaissance masterpieces. The latter practice, although criticized by people today, served a useful purpose in the period before widespread use of the camera and colored illustrations. It ex- posed both the artist and the wealthy patron to the more sophisticated subjects and styles of European art. The results of such travel and study show in the more competent handling of materials and a better grasp of the prin- ciples of art. While many "potboilers" continued to be produced for profit, por- traits often were good likenesses, creating an illusion of organized three-dimensional NOTES ARE ON PAGE 272 |

|

space. Other subject matter in American painting progressively changed, encour- aged by the art union movement. Histori- cal and literary subjects, which had been looked upon as "higher branches" of painting, were displaced by landscape and genre scenes. Few people today realize the tremen- dous influence which art unions exerted at that time on painting in America. The full effects can be recognized only when one considers that in 1849 the American Art-Union in New York alone expended a larger sum for the purchase of paintings than all other patrons in America com- bined.1 This influence is further shown by the statement of George C. Bingham, who admitted he produced his many genre paintings only at the request of the Amer- ican Art-Union. Without its assistance, he said, he would not have attempted such a subject.2 Ohio's most famous woman artist, Lilly Martin Spencer, also produced and sold many genre scenes to both the American and Western art unions.3 Worthington Whittredge, William Sonn- tag, and Benjamin McConkey, all of Cin- cinnati, were encouraged by the American Art-Union to paint regional landscapes, |

|

COLLECTIONS AND EXHIBITS 255 |

|

thirty-six of which were subsequently pur- chased for distribution. Because of the reputation achieved by these and other Cincinnati artists, such as Godfrey Frank- enstein and Robert Duncanson, the Queen City was known as a center of landscape painting by 1850. Although much contemporaneous criti- cism charged the American Art-Union with favoritism and other malpractices, nearly eight hundred paintings by more than a hundred artists had been purchased by 1848. Of these artists, twenty-three were associated with Ohio; certainly a distinguished record for a state which only recently had progressed from the pioneer stage. The Western Art Union, which had been founded in Cincinnati in 1847, continually increased in membership, and the fine arts prospered in a manner previously un- known in the city's history. Charles Cist, completing a survey of local artists in 1851, summarized the situation in this statement: In gathering these facts and dates, a general visit was paid to the pro- fessional studios in Cincinnati, and the gratifying admission was every- where made by the artists, that they had employment ample in its extent, and remunerative in its character; some of them acknowledging, that more commissions were offered than they could possibly undertake to execute.4 That the artists were so well patronized was especially significant considering the progressive shift of emphasis from por- traiture to landscape and genre subjects. It is notable that William L. Sonntag, then at the peak of his career in Cincin- nati, was painting landscape subjects ex- clusively and scarcely keeping up with demand. Nonetheless, the market for por- traiture continued and many artists were painting portraits in Cincinnati during these years. George W. White's portrait of an un- known young woman in the Ohio Histori- cal Society's collection is a good example of midwestern local painting of the pre- war period. Born in Oxford, Ohio, in 1826, White had received his first instruc- tion from Dr. Samuel S. Walker, a physi- |

|

cian and artist of Hamilton.5 In 1843 he tried to establish himself in Cincinnati, but being only seventeen and lacking experience, his work was not well received. After other employment and traveling with a minstrel show for a few years, he returned to Cincinnati in 1847 to share a studio with William Sonntag. Sonntag had not yet attracted public attention, and both young artists had to augment their professional income by decorating omnibuses and railroad cars and paint- ing stage scenery. In 1848 White painted a picture of Hiram Powers' statue "The Greek Slave" which was much lauded and which established his reputation. His work enjoyed popularity in Cincinnati, Oxford, and Hamilton, in which last place he lived after 1857. Despite highly praised portraits of Edwin Forrest, Julia Dean, and other leading people, White was virtually unknown outside that area. White's training and background con- trast sharply with that of John Cranch, who had come to Cincinnati in 1839. John was the older brother of Christopher Pearse Cranch and had been born in Washington, D. C., in 1807. A graduate of Columbian College, Cranch received painting instruction from Charles Bird King, Chester Harding, and Thomas Sully, then studied in Italy from 1830 to 1834.6 After working in New York City for a short time, he moved to Cincinnati, where his training and prestige were re- sponsible for his election in 1840 to the presidency of the section of fine arts of the Society for the Promotion of Useful Knowledge. When Cranch exhibited sixteen paint- ings in 1842, his works included portraits of Charles Dickens, William Henry Chan- ning, and the artists James H. Beard, B. W. Jenks, and Clement R. Edwards. He also exhibited allegorical and literary subjects.7 During his six years in Cin- cinnati, Cranch exercised considerable in- fluence on other painters, but in 1845 he returned to the East. Another artist of equally short resi- dence, but even greater influence, was Minor Kilbourne Kellogg. Although half of his adult life was spent abroad, Kellogg always maintained close ties with friends in Cincinnati. His ability as a painter and his extensive travels and studies made |

|

him the kind of citizen of whom Cincin- natians liked to boast. During Kellogg's youth his family lived in the Robert Owen community at New Harmony, Indiana. In this community young Kellogg met many artists and was encouraged to sketch. Later in life he gave considerable credit to Robert Owen for helping him develop his appreciation of art.8 When the New Harmony venture failed, the Kellogg family settled in Cin- cinnati. There, Kellogg took lessons in |

|

painting from Frederick Franks; mean- while, he developed considerable skill as a musician.9 In 1833, with his painting kit over one shoulder and his violin over the other, he started out as an itinerant painter. After working in Dayton, Troy, Piqua, and Xenia, he went east to Boston. When Kellogg returned to Cincinnati in 1838, his ability in portraiture attracted much attention. He was commissioned to paint Andrew Jackson at the Hermitage in |

|

|

|

1840; Governor James K. Polk of Ten- nessee and President Van Buren also sat for him.10 Apparently Kellogg's work was well re- ceived in governmental circles, for in 1841 he received a government appointment as courier to Italy. He remained there for seven years studying and painting, and on several occasions traveled through the Near East and sketched in Egypt.11 Re- turning to America late in 1847, Kellogg was warmly received in Cincinnati in |

|

1848. He was commissioned to do many portraits, including ones of President Polk, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, and General Winfield Scott. His works were exhibited at the National Academy, the Pennsylvania Academy, and the Boston Athenaeum. Despite the acclaim and gratifying suc- cess of his homecoming, Kellogg again sailed for Europe in 1854. He returned after the Civil War to set up a studio in Baltimore, later painting in Cleveland |

|

Thomas W. Cridland by Charles E. Cridland and Toledo. Today his works are to be found in all the larger cities of Ohio. Many local artists of limited fame were producing good portraits during this per- iod in Cincinnati. Charles Soule, Sr., was called "our best portrait painter" by Nicholas Longworth in 1844, and he added, "His portraits, like those of Beard, are hard to be numbered."12 Charles E. Crid- land, William Walcutt, David Walcutt, B. W. Jenks, John R. Johnson, A. H. Ham- mell, and others were well patronized. |

|

Charles Edwin Cridland was an artist whose career had promised much, but whose life ended in unhappiness. He had been born of English parents who emi- grated to New York in 1820. About 1840 Cridland moved west to Louisville, Ken- tucky, where his older brother Thomas, a frame maker, was in partnership with the artist Louis Morgan. Although no records exist to prove it, Charles Crid- land's paintings suggest that he was a student of Morgan's. |

|

COLLECTIONS AND EXHIBITS 259 |

|

In Cincinnati, Cridland studied with James H. Beard and rapidly gained stature as a portrait artist. He painted many theatrical people, including John McCullough, Mary Anderson, Edwin Booth, and Alvin A. Read. After wide- spread success, a scandalous love affair ruined his reputation and caused an emo- tional imbalance from which he never recovered.13 The careers of the two Walcutt brothers, William and David, have happier endings. Both were successful portrait painters in Columbus prior to going to Cincinnati. William Walcutt, who moved to the Queen City in 1844, continued to be very successful in portrait work but found himself drawn to sculpture. In 1849 he moved to New York and in 1852 went abroad to study in London and Paris. Shortly after his return in 1855, he was commissioned to execute the Perry Monu- ment at Cleveland. David Walcutt, who learned portrait painting from his older brother William, was only twenty-one in 1846 when he joined his brother in the Queen City. Earlier he had achieved professional status in Columbus. Five years later, when Cist published a long list of Cincin- natians who owned his paintings, the num- ber of patrons attested to his popularity as a portraitist.14 In 1850 David worked with his brother in New York but soon returned to Cincinnati. In 1858 he traveled in Europe. Several of his portraits of public officials now hang in the Ohio state- house in Columbus. While painters in Cincinnati were en- joying great prosperity, artists in other parts of the state were still finding it necessary to travel to keep fully employed. The wealth from commerce and industry along the Ohio River could support many cultural activities which the rest of the state, being less heavily populated, could not. Artists tended to follow the main routes of commerce and usually planned their tours to end in Cincinnati or Pitts- burgh. Marietta, a midpoint between the two cities, was a popular port of call for artists going up or down the river. During the middle of the century, two artists, Sala Bosworth and Charles Sul- livan, maintained studios in Marietta, al- though both periodically traveled through |

|

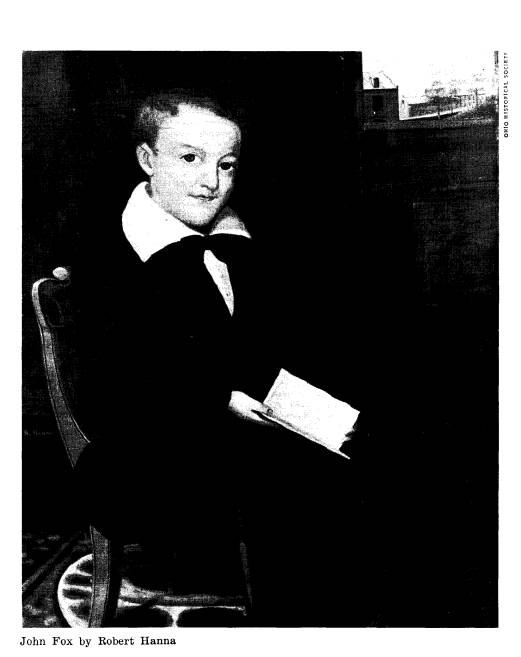

the southeastern part of the state. Lilly Martin Spencer also began her career there as a child protege of the two paint- ers before she went to Cincinnati. Both Bosworth and Sullivan studied painting in Philadelphia for about one year, the former at the academy and the latter with Thomas Sully. Despite this training neither artist completely lost the native primitive quality inherent in his early work, although Bosworth showed marked improvement through the years. His strong, accomplished portraits brought many commissions in Marietta, Zanesville, Columbus, Circleville, Chilli- cothe, and Athens, while his landscapes excelled those of most competitors. Shortly before the Civil War, Bosworth's sight began to fail. He continued to paint on a limited basis but had to turn to public service for a means of livelihood. Sullivan's major interest was landcape painting, but he too did many portraits, especially during winter trips through Tennessee and Georgia. A large number of his landscapes of the Muskingum Val- ley and pictures of local residents are to be found in the collection of the Campus Martius Museum at Marietta. On their trips to Zanesville, Bosworth and Sullivan faced strong competition in James F. Barton, a local artist who began painting in 1842. Barton had the advan- tage of studying at the National Academy for sixteen months and was a capable painter. Portraits were his forte, al- though he occasionally did landscapes. Artists who traveled north from Zanes- ville and Columbus had difficulty in find- ing commissions until they reached the settled communities of the Western Re- serve. The northwest part of the state developed slowly and frontier conditions prevailed in that area until shortly before the Civil War. Cleveland, the largest city in northern Ohio, could boast only six thousand people in 1840. Nonetheless, hopeful itinerants crisscrossed the central and northern part of the state in complex patterns of travel, distributing their works over widespread areas. As might be expected, their paintings often re- sembled the primitive works produced earlier along the Ohio River. The Rev. Robert Hanna, who visited Cleveland during this period, is here men- |

|

|

|

Rocky Landscape by Sala Bosworth tioned as an example of such a primitive itinerant painter. He was a Methodist minister, a gifted and versatile man who had painted portraits through the South with considerable success.15 The most persevering artist in the Cleveland area, although not the most famous, was Jarvis F. Hanks. Hanks be- gan his career as an itinerant sign painter at Wheeling in 1817.16 When he arrived in the Western Reserve in 1825, Cleveland was a village of six hundred persons. |

|

Although he found employment more often painting signs than portraits, it was he who gave James Henry Beard his first instruction and started him off as an itinerant artist. After working in Cin- cinnati, Chillicothe, Circleville, and New York City, Master Hanks, as he then called himself, settled permanently in Cleveland in 1836. Other painters who worked in the West- ern Reserve about this time were Moses Billings, C. H. Hicks, Sebastian Heine, |

|

Lewis B. Chevalier, George J. Robertson, and Thomas H. Stevenson. The latter came to Cleveland about 1841 and pro- duced landscape paintings which demon- strated considerable knowledge and experi- ence. He also did portraits and miniatures while giving lessons in art. In 1843 Stevenson was in Zanesville doing minia- tures on ivory, and pencil sketches,17 but four years later was back in northern Ohio at Gustavus painting portraits. About 1855 he moved westward to Wis- |

|

consin, where he specialized in landscapes for the next several years.18 Allen Smith, Jr., was a famous and enduring name in Cleveland art circles during the nineteenth century. Smith moved to Ohio from Detroit in 1842 and, with the exception of four years in Cin- cinnati, lived in Cleveland the rest of his life.10 He was a prolific painter and prob- ably did more portraits than any other Cleveland artist. In his later years the local scenery inspired him to do landscape |

|

262

OHIO HISTORY |

|

subjects in addition to portraits and genre. Today his works are found in leading museums across the country and in many Cleveland homes. Because water transportation provided easy means of travel between Detroit and Cleveland, the majority of artists in the area sought commissions in both cities at one time or another. Alonzo Pease was one of many painters who traveled back and forth. While in Cleveland he painted Joshua R. Giddings and several other notable citizens of the Western Reserve. Surveying the field of painting in Ohio one hundred years after these artists were working, one cannot fail to be im- pressed by their ubiquitous nature. Equally astounding is the number of men who depended on painting as a means of livelihood while central and northern Ohio were still in the process of being settled. Two factors may have encouraged this unique cultural development. |

|

The market for painting may be attrib- uted to the character of the founders of Ohio. These were not all rough, illiterate frontiersmen who established isolated out- posts in the wilderness; rather, they were substantial New Englanders, Virginians, and others of good educational background and some means. They had been accus- tomed to well-designed furniture, silver craftsmanship, and wall decorations in their former homes, and their families were taught to respect and enjoy such heirlooms. Secondly, the established settlers, espe- cially the second generation, felt compelled to have a portrait or painting in the fam- ily as a symbol of the luxury and culture so frequently lacking in the utilitarian furnishings of the home. Undoubtedly there were other influences contributing to the demand for paintings, but, in any case, it is significant that more than three hundred and sixty professional artists worked in Ohio prior to the Civil War. THE AUTHOR: Donald

R. MacKenzie is chairman of the department of art at the College of Wooster. This is the third in a series of articles he has written on early Ohio painters that is based on the painting collection at the Ohio Historical Society. The first article, "The Itinerant Artist in Early Ohio," appeared in the Winter 1964 issue and the second, "Early Ohio Painters: Cincinnati, 1830-1850," appeared in the Spring 1964 issue. |

|

COLLECTIONS AND EXHIBITS EARLY OHIO PAINTERS: THE PREWAR YEARS by DONALD R. MacKENZIE |

|

|

|

HIGHER standards in painting character- ized the pre-Civil War period of art in Ohio. Improved transportation encour- aged artists to travel, and almost every painter visited New York, frequently tour- ing Boston and Philadelphia as well. There, they had the opportunity to see a limited number of imported European paintings and a variety of notable Amer- ican works. Most established painters who desired it were able to manage a trip to the European art capitals. Such tours were often financed by prepaid commis- sions on future paintings or specific com- missions to copy Renaissance masterpieces. The latter practice, although criticized by people today, served a useful purpose in the period before widespread use of the camera and colored illustrations. It ex- posed both the artist and the wealthy patron to the more sophisticated subjects and styles of European art. The results of such travel and study show in the more competent handling of materials and a better grasp of the prin- ciples of art. While many "potboilers" continued to be produced for profit, por- traits often were good likenesses, creating an illusion of organized three-dimensional NOTES ARE ON PAGE 272 |

|

space. Other subject matter in American painting progressively changed, encour- aged by the art union movement. Histori- cal and literary subjects, which had been looked upon as "higher branches" of painting, were displaced by landscape and genre scenes. Few people today realize the tremen- dous influence which art unions exerted at that time on painting in America. The full effects can be recognized only when one considers that in 1849 the American Art-Union in New York alone expended a larger sum for the purchase of paintings than all other patrons in America com- bined.1 This influence is further shown by the statement of George C. Bingham, who admitted he produced his many genre paintings only at the request of the Amer- ican Art-Union. Without its assistance, he said, he would not have attempted such a subject.2 Ohio's most famous woman artist, Lilly Martin Spencer, also produced and sold many genre scenes to both the American and Western art unions.3 Worthington Whittredge, William Sonn- tag, and Benjamin McConkey, all of Cin- cinnati, were encouraged by the American Art-Union to paint regional landscapes, |

(614) 297-2300