Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

|

|

|

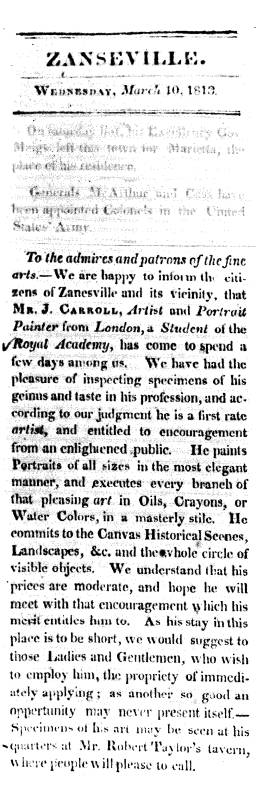

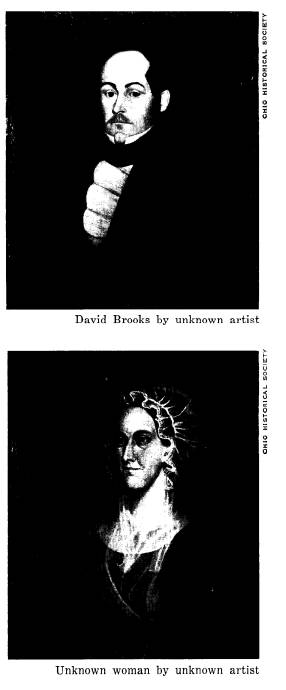

COLLECTIONS AND EXHIBITS The ITINERANT ARTIST In Early Ohio by DONALD R. MacKENZIE THE PAINTING collection of the Ohio Historical Society represents all phases of midwestern painting in the nineteenth century. Since the opening of the Hall of Paintings at the Ohio State Museum in 1953, a new emphasis has been placed on the Society's permanent collection and its contribution to knowledge of the cul- tural heritage of the state. Today the native American quality of early nine- teenth century paintings is recognized and the public has become interested in search- ing out family portraits once relegated to attic storage. Few pictures attract more attention or give more delight than the primitive portraits by the early itinerant artists. Although many works have been lost and their artists forgotten, the grow- ing evidence confirms the importance of these paintings in the lives of our early Ohio ancestors. Beginning with the arrival of the Eng- lish painter Jacob Beck in Cincinnati in 1795, artists periodically visited the fron- tier settlements. Prior to 1830, only Cin- cinnati and a few of the larger towns could boast of a local artist, although many house and sign painters attempted primitive portraits. The amazing fact is the number of artists circulating through the state. A recent study by the author shows that more than sixty professional painters worked in Cincinnati before 1840 and more than three hundred and sixty artists painted in Ohio prior to the Civil War. This number includes itinerant painters, who constitute about fifty per- cent of the men listed, but does not NOTES ARE ON PAGE 60 |

|

42 OHIO HISTORY |

|

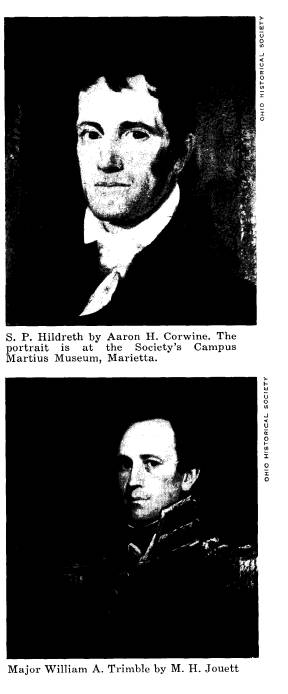

include those artists who merely passed by on the Ohio River with no more than a few days pause in Cincinnati, the casual amateurs, who were numerous in the late 1850's when sketch clubs became the mode, and many painters who, while born in Ohio, were not producing artists in this state before the year 1860. Most of these painters were not great artists. Master paintings are rarely pro- duced in the cultural vacuum of frontier settlements and during periods of great migrations. In terms of artistic accom- plishment the frontier artist can hardly be compared with his European contem- porary. In fact, Henry Tuckerman seems to have grasped the situation exceedingly well when, in 1867, he stated: "We have abundance of assiduous painters, who ex- haust a town in a month in delineations of its leading citizens, fill their purses, and inherit a crop of newspaper puffs; but give no 'local inhabitation or name' to any idea, principle, sentiment, or even rule of Art."1 Here and there an artist of talent stands out. Aaron Corwine is one whose potential greatness will never be known; he died early, at age twenty-eight. Drake and Mansfield in their booklet Cincinnati in 1826 wrote that Corwine "had but a single rival in the Western country."2 Tuckerman referred to Corwine and Mat- thew H. Jouett of Kentucky as the two leading artists in the West.3 Other Ohio painters who achieved national fame were Thomas Cole, William Henry Powell, Wil- liam Sonntag, Joseph Oriel Eaton, and T. Worthington Whittredge, who later be- came president of the National Academy of Design. All were born in Ohio or began their careers in this state. It is in Ohio that one discovers the true stature of Stein, the painter who attracted Thomas Cole to a career in art, and the ability of Des Combes, the itinerant limner with whom Cole competed in Zanesville, Lancaster, and Chillicothe. With a notable number of exceptions, these early Ohio painters tended to be unacademic and, like Cole, self-taught. Their paintings, while not devoid of aesthetic quality, are most important today as social documents. Pioneer life was a daily struggle for survival and since art forms did not con- tribute to food, shelter, or protection, their |

|

|

|

COLLECTIONS AND EXHIBITS 43 |

|

absence did not seem important. But as soon as frontier life was stabilized, art forms again became significant in every- day living. Painting was especially im- portant to the second generation, settled and prosperous descendants of the pio- neers, who sought public attestations of social status and who valued art forms precisely because they were previously thought superfluous. Like fine silver and furniture, portraits suggested social stat- ure with dignity. In the days before the camera, these were the visual record of the family. The frontier did not rise to the level of landscape painting or other subjects; this came later in urban centers as taste developed through education. As Steubenville, Marietta, and Cin- cinnati, on the river, and Zanesville and Chillicothe, inland, began to assume the characteristics of towns, itinerant artists drifted into the area to satisfy the local needs. Most of these men would turn their hand to any job requiring their skill, from painting a sign to decorating a chair, mantle, carriage, or barge. More than one hundred such men, known from their ad- vertisements in local papers, are listed by Rhea Mansfield Knittle, and her sur- vey has only scratched the surface.4 During the first period of settlement, while the population was thinly scattered over large areas, the professional man or specialist had to travel over a wide ter- ritorial circuit to obtain enough customers for his services to earn a livelihood. Lawyers and judges, ministers, den- tists, doctors, and artists, all followed this practice. Reaching a town, the itin- erant would establish himself in a suit- able location and publicize his availability. When all demands were supplied he moved on to fresh territory. Vocations such as the ministry, law, and dentistry were well suited to regularly repeated circuits of a few weeks duration. Although portrait and sign painting often called for a sub- stantial stay in each town, once the mar- ket was exhausted it remained so for a considerable length of time. Hence the itinerant artist rarely retraced his steps. This practice has contributed to the diffi- culty and confusion surrounding the iden- tification of paintings by these early art- ists, most of whom did not sign their canvases. |

|

|

|

44 OHIO HISTORY |

|

David Bourdon, a Swiss artist, was such an itinerant. First heard of in Phila- delphia in 1797, he appeared in Pittsburgh about 1810, where he "painted small por- traits in an indifferent style."5 Six years later Bourdon was working in Ohio. The Chillicothe Scioto Gazette of November 28, 1816, carried his advertisement as "David Boudon," a painter from Geneva, who, in addition to drawing profiles and miniature portraits, intended to open an art academy in Chillicothe during the winter months providing he could find twenty pupils at ten dollars per quarter. John R. Carroll, an English immigrant artist, followed much the same route west and, like Bourdon, apparently traveled overland. In 1812 Carroll opened a studio in Pittsburgh and painted portraits while teaching freehand drawing, watercolor, and landscape painting.6 In the spring of 1813 he advertised his availability in Zanesville and later the same year es- tablished a studio in Cincinnati. No record exists today of Carroll's success as a portrait painter, but it is known that he became a member of the early Cincinnati Thespian Society and prepared some of the scenery in the productions. Unlike Bourdon and Carroll, the great majority of itinerant painters in Ohio were natives of the West, or grew up in the region. Most, like James Bowman, having observed an older limner at work, had resolved to try their hand after practicing the fundamentals. Bowman was probably started by J. T. Turner, an itinerant who cut silhouettes and painted likenesses and signs. Turner traveled along a route from Pittsburgh in 1812 to Cincinnati in 1814, visiting Chillicothe in 1816, and Maysville, Kentucky, the follow- ing year. Along the way he is presumed to have taught the principles of painting to Bowman, who had been working as a carpenter in Chillicothe.7 Bowman, in turn, became a traveling portrait artist in the Pittsburgh area until success urged him eastward to New York, and eventually to European art centers for study. In 1817 Turner spent some time in Maysville, Kentucky, instructing Aaron Corwine, then only fifteen years old. When Corwine proved to have extraordinary talent, Turner sent him to Cincinnati to study. There Corwine's ability in portrai- |

|

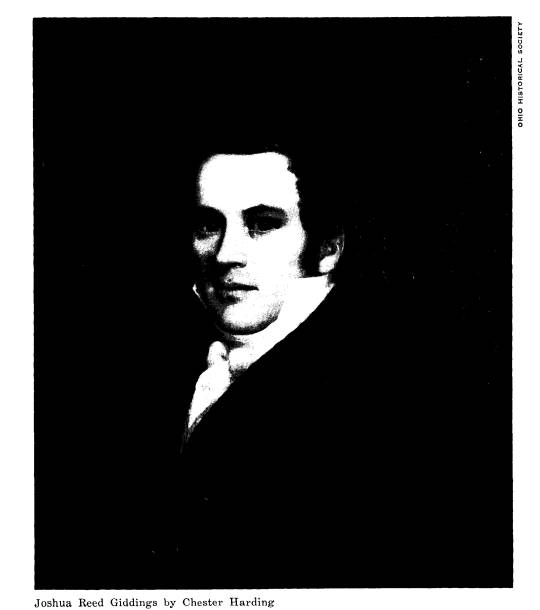

ture so impressed a number of business- men that they offered to finance his trip to Philadelphia to study with Thomas Sully. His expenses were met by means of advanced payments on portraits.8 Ap- parently Corwine's reputation and cause became public, for a long article prais- ing his talent and requesting the support of the citizenry appeared in the Cincinnati Inquisitor Advertiser of August 11, 1818. After studying with Sully, Corwine re- turned to Cincinnati to work. The gener- ous act of patronage which gave Corwine his start established a precedent in the Queen City, repeated on many occasions over the years. Artists traveling the overland route west from Pittsburgh frequently made Steubenville their first stop. In 1820 an itinerant painter, known only by the sur- name Stein, did a number of portraits in the area and gave painting lessons to young Thomas Cole.9 William Dunlap sug- gests that Stein was born in Washington, Virginia (a fact which is corroborated by Stein's eastern style of painting), and that his painting career was carried on principally west of the Alleghenies (to date examples of his works have been found only in Ohio).10 Stein returned to Steubenville in 1827, at which time he is known to have painted portraits of the founder of the city, Bezaleel Wells, and his wife.11 It is possible that he was the artist of the same name who gave paint- ing lessons to John James Audubon in New Orleans in 1822.12 Thomas Cole, Stein's pupil in Steuben- ville, was a pattern designer in his father's wallpaper factory when the itin- erant encouraged him to take up oil paint- ing. In addition to showing young Cole by demonstration, Stein loaned him an English book on painting, with engraved illustrations dealing with design, compo- sition, and color.13 After several practice portraits of his family, Cole walked a circuit of Mount Pleasant, St. Clairsville, Zanesville, Lancaster, Chillicothe, and Steubenville. He profited from the experi- ence but made no money. The newspapers of the period were sprinkled with puffy advertisements prom- ising perfect likenesses and complete satisfaction at reasonable rates. With a limited market, competition was keen; few |

|

painters prospered, and most barely eked out an existence. Almost all artists in- vestigated the demand for their abilities in several towns before gravitating to- wards Cincinnati. The cultural advantages of the Queen City attracted nearly every artist in the region at one time or another. Some came to admire and study, then returned home; others stayed to compete for professional standing; a few found fame and gained recognition on the national level. As early as 1812 Cincinnati had a draw- ing and painting academy founded by Ed- |

|

win B. Smith. Newspaper notices of the school state its purpose as "devoting its training to portraits, miniatures, land- scapes, and ornamental work."14 Smith, a painter of portraits and historical sub- jects, had taught earlier in Lexington.15 He was only modestly successful in his Cincinnati enterprise. Competition in the form of John Carroll appeared in 1813, and the following year the versatile J. T. Turner was advertising his services.16 All of these men maintained studios in the city for several years. Nathan Wheeler, a portrait and minia- |

|

46 OHIO

HISTORY |

|

ture painter from Massachusetts, arrived in the Queen City in 1818. The advertise- ment announcing his exhibition mentions a full length study of President Washing- ton, a Biblical scene involving ten figures, and a portrait of General Jackson and "several others."17 Despite an impressive beginning with portraits of Martin Baum, wealthy civic leader, and his wife, Whee- ler's success was limited.18 After six years of painting in the city, he gave up the pro- fession to become a merchant.19 Another portrait artist, John Rutherford, enjoyed even less success and left after a few months. About this time, John Neagle of Phila- delphia, just starting out as a professional painter, stopped at Cincinnati on his way to Lexington. Portrait customers were scarce and his visit was brief. William Edward West, visiting the city en route to Natchez, had the same experience. Even the notable Chester Harding, who later enjoyed an international reputation, com- plained about the lack of clients when he advertised for portrait commissions in Feb- ruary of 1820.20 Looking back, one might well surmise that a population of nine thousand could not support so many art- ists. Cultural progress in Cincinnati was promoted by civic leaders such as Dr. Daniel Drake, who had been largely re- sponsible for aid to Aaron Corwine. In 1818 a group of citizens headed by Dr. Drake and William Steele former a West- ern Museum Society and two years later opened a combination natural history and art museum. John J. Audubon came to Cincinnati in 1819 to learn taxidermy and to help prepare the exhibition. Another artist and natural scientist, John Dor- feuille, joined the staff about the same time. Each year the number of professional artists visiting and working in Cincin- nati increased. A second picture gallery, |

|

called Letton's Museum, was established in 1819, and less than ten years later a third gallery opened. Many notable travelers, among them William Bullock, Harriet Martineau, and Michael Chevalier, visited Cincinnati and wrote of their admiration for the city and its Western Museum. Speaking more spe- cifically in praise of art in the Queen City, an 1840 editor of the New York Star wrote: Cincinnati! What is there in the atmosphere of Cincinnati, that has so thoroughly awakened the arts of sculpture and painting? It cannot surely be mere accident which gives birth to so many artists, all of distin- guished merit, too; what must be quite as gratifying to that city--all possessing high moral worth.2l There can be little doubt of the in- fluence of Cincinnati on the art of early Ohio. As the largest, most properous city in the West, her leadership was inevitable, and few painters in other areas of the state contemporaneously achieved the level of work produced in the Queen City. When viewed within the framework of the national perspective, early Ohio paint- ing does not possess characteristics which differentiate it in quality from painting in other western states. In quantity, how- ever, the number of paintings produced is extraordinary for a virginal territory in a period of settlement. The works show many variations in ability and style, re- flecting the lack of intercourse between artists and the absence of training facili- ties in the West. Since the majority of painters had little or no academic instruc- tion, it was left to a few foreign artists, such as J. T. Turner, to provide a profes- sional leavening. Only a fortunate few had the opportunity to go to the East or abroad for study. THE AUTHOR: Donald

R. MacKenzie is chairman of the department of art at the College of Wooster. Some years ago he cataloged the Society's paintings. |

|

|

|

COLLECTIONS AND EXHIBITS The ITINERANT ARTIST In Early Ohio by DONALD R. MacKENZIE THE PAINTING collection of the Ohio Historical Society represents all phases of midwestern painting in the nineteenth century. Since the opening of the Hall of Paintings at the Ohio State Museum in 1953, a new emphasis has been placed on the Society's permanent collection and its contribution to knowledge of the cul- tural heritage of the state. Today the native American quality of early nine- teenth century paintings is recognized and the public has become interested in search- ing out family portraits once relegated to attic storage. Few pictures attract more attention or give more delight than the primitive portraits by the early itinerant artists. Although many works have been lost and their artists forgotten, the grow- ing evidence confirms the importance of these paintings in the lives of our early Ohio ancestors. Beginning with the arrival of the Eng- lish painter Jacob Beck in Cincinnati in 1795, artists periodically visited the fron- tier settlements. Prior to 1830, only Cin- cinnati and a few of the larger towns could boast of a local artist, although many house and sign painters attempted primitive portraits. The amazing fact is the number of artists circulating through the state. A recent study by the author shows that more than sixty professional painters worked in Cincinnati before 1840 and more than three hundred and sixty artists painted in Ohio prior to the Civil War. This number includes itinerant painters, who constitute about fifty per- cent of the men listed, but does not NOTES ARE ON PAGE 60 |

(614) 297-2300