Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

|

|

|

VALLANDIGHAM AS AN EXILE IN CANADA 1863-1864

by FRANK L. KLEMENT

While Clement L. Vallandigham lived in Canada for nearly a year during the Civil War as an exile from the United States, his path crossed those of a number of men well-known in Canadian history. Thomas D'Arcy McGee, emerging as a critic of the Canadian government, befriended and defended the exile. Charles J. Brydges, superintendent of the Grand Trunk Railroad, gave a dinner in Vallandigham's honor and presented him with a pass on his railroad. And George Brown, the influential editor of

NOTES ARE ON PAGES 208-210 |

152 OHIO HISTORY

the Toronto Globe and a political

power in Canada West, did all he could

to discredit the exile and shape public

opinion against him. Officially, the

Canadian government gave Vallandigham no

recognition, friendly or

otherwise; unofficially, George Brown's

editorials bespoke the views of

the John Sandfield Macdonald ministry

and of the Liberals, who gave

the coalition government a scant

majority in the legislative assembly.

Even before Vallandigham arrived in

Canada as an exile, his name

appeared occasionally in the country's

press. Early in the American Civil

War he had twisted the tail of the

British lion and twitted William H.

Seward, his country's secretary of

state, for surrendering James M. Mason

and John Slidell to the British to

settle the Trent imbroglio. During 1862

Vallandigham's advocacy of peace and

compromise and his blatant criti-

cism of the Lincoln administration gave

him more frequent mention in

Canadian newspapers. Then, in May 1863,

Vallandigham's name flashed

along the telegraph wires as news

stories related accounts of his summary

arrest and trial by military authorities

in Ohio. Leading Canadian news-

papers reported that Lincoln's foremost

critic had been banished to the

Confederacy and that his party, in turn,

had nominated him as the

Democratic gubernatorial candidate in

Ohio. Reports made the rounds

that Vallandigham expected to find his

way to Canada to conduct his

campaign for the governorship of Ohio

from a Canadian base.1

Clement L. Vallandigham first set foot

on Canadian soil on July 5,

1863, when he arrived in Halifax aboard

the Harriet Pinckney. Details

of his journey from Cincinnati to Canada

came to light. After being

exiled to the southern Confederacy,

Vallandigham had journeyed to

Wilmington, North Carolina, run the

blockade aboard the Lady Davis,

arrived in Bermuda, and taken the first

boat bound for a Canadian port.

The exile received a rather friendly

reception in Halifax. Since he

symbolized opposition to the Lincoln

administration, certain Halifax

citizens lent him their sympathy. Some

Halifax merchants had invested

heavily in blockade runners like the Will

o' the Wisp and the Isabella

Thompson. At the time Vallandigham reached Nova Scotia, the

Halifax

merchants who had chartered the Will

o' the Wisp were demanding dam-

ages from the United States for illegal

seizure of the schooner, and

those who owned shares in the Isabella

Thompson were expressing indigna-

tion over the capture of their ship by a

blockading squadron. Then, too,

several days before the exile's arrival

in Halifax, a Yankee gunboat had

visited the port, and its crew had

received a most hostile treatment. When

the apprehensive Yankee captain had

taken on coal and put out to sea

at the earliest possible moment, he

heard the crowd on the wharf give

three resounding cheers for Jefferson

Davis and the southern Confederacy.2

Vallandigham's stay in Halifax was brief

indeed. He booked passage

on the schooner Daniel P. King bound

for Pictou with mail and a general

cargo. He secured hotel accommodations

for the night. And he hurried to

the telegraph office to send off several

messages, one to his Dayton friends

to say that he expected to meet them at

the Clifton House, Niagara, Canada

VALLANDIGHAM AS AN EXILE 153

West, on the thirteenth. He also sent

$170 in bank notes, given him on

his trip through the Confederacy, to a

Philadelphia destination via express.3

The American consul in Halifax dutifully

reported Vallandigham's

arrival, and he noted with interest

where the exile went and with whom

he talked. "His intimate associates

here," wrote the concerned consul,

"were the most violent

secessionists and supporters of the Confederate

cause."4

After the American exile had left for

Pictou on the morning of July 7,

the editor of the Novascotian composed

a pro-Vallandigham editorial which

proved that pro-southern sentiment was

strong in Halifax. The editor

explained Vallandigham's position

sympathetically and implied that Presi-

dent Abraham Lincoln had acted like a

military dictator and an enemy

of the traditional English liberties.5

When Vallandigham arrived at Pictou, he

found the Lady Head in port,

being readied to sail for Quebec and

in-between ports. After the line

of passengers and the sacks of mail were

transferred from the Daniel P.

King, the Lady Head raised anchor and sailed for

Quebec. Wearisome

stops at Shediac, Chatham, Newcastle,

Dalhousie, Paspebiac, and Gaspe

tested the patience of the passengers.

The 168-ton iron steamship, with its

cargo of mail, freight, and

eighty-seven passengers, arrived in

Quebec Bay early on the morning of

July 11. In the early dawn "the

exiled stranger" walked up Palace Street

and took a room at the Russell Hotel.

The presence of several Cincinnati

citizens at the same hotel gave

Vallandigham a chance to inquire about

the reaction to his arrest and his

chances of being elected governor of

Ohio in the October 13 elections.

Vallandigham also announced his inten-

tion to proceed as soon as possible to

Niagara, Canada West, and take

up quarters at the Clifton House. His

arrival in Canada received a

secondary notice in the country's press,

for reports concerning the great

battles of Gettysburg and Vicksburg

monopolized most of the newspaper

columns.

Charles S. Ogden, the excitable United

States consul stationed in Quebec,

rushed off a terse telegram to his

superior in Washington: "C. L. Vallan-

digham is here."6 Ogden, who seemed

to think that the main responsibility

of a consul was to serve as a spy and to

clip Quebec newspapers, tried to

keep track of Vallandigham's movements

and to find out the exile's plans.

It upset Ogden to note that prominent

Quebec citizens called upon Vallan-

digham at his hotel; it galled him to

have to report that Edward W. Watkin,

prominent English financier linked to

various Canadian railroad and

commercial interests, and Charles J.

Brydges, superintendent of the

Grand Trunk Railroad and a member of the

elite Stadacona Club of

Quebec, escorted Vallandigham around the

city to see various scenic

spots or places of historical interest.7

Watkin and Brydges persuaded

Vallandigham to tarry a day in Quebec

so the two could give a dinner in the

exile's honor next evening at the

Stadacona clubhouse. Quite a number of

notables, including John A.

154 OHIO HISTORY

Macdonald, onetime head of the Canadian

government, attended the affair.

Watkin, London entrepreneur and

president of the Grand Trunk Railroad,

presided as toastmaster. Neither Watkin,

nor others who spoke briefly,

made mention of the American civil war

or indicated whether their sym-

pathies lay with the North or South.

They viewed the dinner as "mere

hospitality to a refugee" who had

landed in Canada "in distress."8 Even-

tually, Vallandigham had a chance to

thank his host and his newly found

Canadian friends for their gracious

hospitality. He began his remarks

with an apology for appearing in a

wrinkled suit and for the poverty

of his dress. "I can only

explain," he added with a bid for sympathy,

"that I am standing in the clothes

I was allowed to put on, after being

taken out of my bed, in my own house,

without warning and without war-

rant, and I have not the means to

reclothe myself." Then in a few

appropriate sentences, evidently without

repentance or rancor, Vallan-

digham thanked Canada for extending him

rights and freedoms which

the Lincoln administration had denied

him.9

Later that evening Watkin and Brydges

escorted the exile down to

the Grand Trunk Railroad depot. Watkin

offered "a friendly loan," which

Vallandigham declined; Brydges offered a

free railroad pass, which the

exile accepted. Before boarding the

cars, Vallandigham thanked his friends

and supposed that he might return for a

visit to Quebec in the near future,

but he was anxious to get to Niagara and

the rendezvous with his political

friends.10

If Ogden, the American consul, or

William H. Seward, United States

secretary of state, expected Canada to

give Vallandigham an unfriendly

welcome, they were badly mistaken. In

the first place, the English practice

of hospitality to exiles had been

ingrained in the Canadians. In the

second place, most Democratic papers in the

States depicted Vallandigham

as a martyr to free speech, and Canadian

devotion to the traditional

English liberties tempted them to view

the exile somewhat sympathetically.

Considerable antipathy to the Lincoln

administration existed throughout

Canada, although pro-southern sympathy

of the type exhibited in England

had little to do with it. United States

brashness in diplomacy made more

of a contribution. At the time

Vallandigham arrived in Quebec an uneasy

peace still existed between the United States

and Canada--one Canadian

newspaper had earlier referred to the

situation as "a war in anticipation."11

United States Consul General Joshua R.

Giddings, stationed at Montreal,

had shown a lack of good judgment by

talking of his country's annexation

of the Canadas--at a later date he

suggested how and when it should

be done.12 The indiscreet consul had

also suggested that the reciprocity

treaty between Canada and his country,

drafted for a ten-year term in

1854, be terminated as a lesson to

British and Canadian commercial

interests. Then too, during the summer

of 1862, British military experts

had visited Canada to examine all

possible avenues of attack, for rumors

persisted that the Union army might be

used to annex Canada after the

southern Confederacy had collapsed. Some

Canadian newspapers, there-

VALLANDIGHAM AS AN EXILE 155

fore, expressed editorial sympathy for

Vallandigham even before he set

foot upon Canadian soil. The Quebec

Chronicle, for example, criticized

President Lincoln's justification of the

summary treatment accorded

Vallandigham as "one of the most

puerile compositions" ever emanating

from that "source."13

On the other hand, some forces worked

for United States-Canadian

amity. The American civil war helped to

bring economic prosperity to

Canada, and sensible Canadians, like

George Brown of the Toronto Globe,

recognized that peace and a strict

neutrality should be the logical policy.

Since sympathy for Vallandigham would

violate the principle of strict

neutrality, Brown's editorials in the Globe

expressed an anti-Vallandigham

tone. He labeled the exile "the

chief of the Northern sympathizers with

the Southern rebellion" and

correctly supposed that the Union victories

at Gettysburg and Vicksburg made Vallandigham's

chance of gaining

the governorship of Ohio "very

slender" indeed.14 The outspoken editor

of the Hamilton Times also

betrayed his anti-Vallandigham views in his

editorials by calling the exile a

"notorious individual" and an "apologist

for secession."15 The

danger that Britain might recognize the Confederacy

or intervene in favor of the South had

passed long before Vallandigham

set foot upon Canadian soil. Time had

healed the injury to United States-

Canadian relations caused by incidents

in 1861 and 1862, and the late

summer of 1863 represented "the

most tranquil period" in relations be-

tween the two North American

neighbors.16

The Canadian government of July 1863 was

in no position to officially

give Vallandigham either a glad hand or

a cold shoulder. Nearly two

months before Vallandigham had arrived

in Quebec, the John Sandfield

Macdonald ministry had fallen because of

the defection of French-Canadian

members on the second reading of a

militia bill.17 John Sandfield Mac-

donald then ordered new elections and

reconstituted his cabinet in prep-

aration for the general election.

Macdonald joined forces with George

Brown and Antoine Dorian to form a new

ministry, and he dropped

Louis V. Sicotte and Thomas D'Arcy McGee

from his cabinet. The two

well-known Montreal members of the

legislative assembly thereupon

joined the opposition.

The general election of 1863 proved to

be a two-party battle between

the Liberals and the

Liberal-Conservatives, with the former, led by John

Sandfield Macdonald, securing a two or

three vote majority in the new

(the eighth) parliament. The virtual

deadlock -- the margin was so narrow

and the new coalition so unstable that

the new ministry would be com-

pelled to walk the tightrope with care

-- hampered the revised John

Sandfield Macdonald government (some

historians call it the Macdonald-

Dorian ministry), and it avoided taking

stands upon many issues, includ-

ing the presence of Clement L.

Vallandigham upon Canadian soil. The

government, then, ignored Vallandigham's

presence, although individuals

who supported the Macdonald ministry --

like George Brown of the

Toronto Globe -- would speak out

against him. Oliver Mowat, a close

|

156 OHIO HISTORY

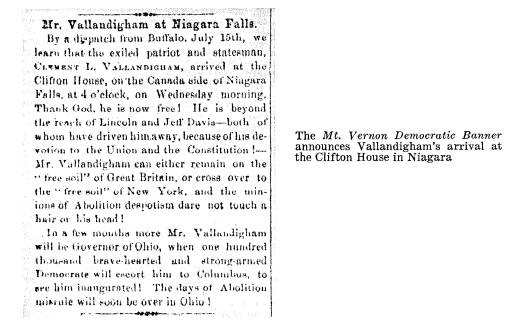

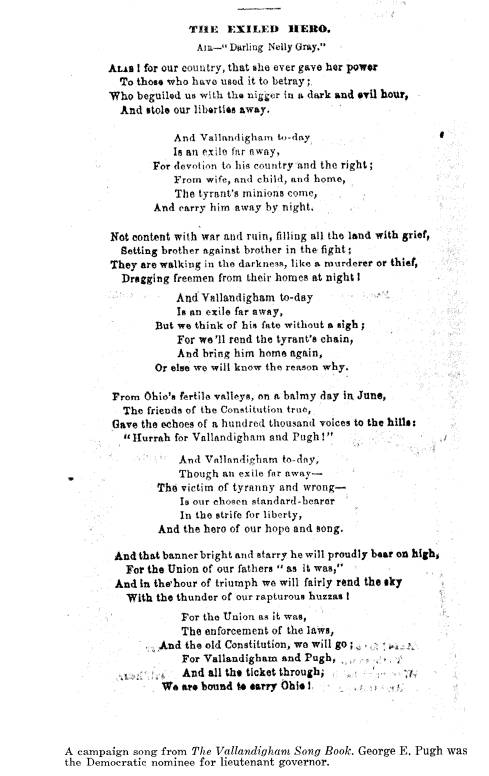

associate of Brown and a Toronto "representation by population" man, held a ministry portfolio and helped pull chestnuts out of the fire for the editor of the Globe. So although the Macdonald government avoided going on record for or against the exile, most Liberals seemed to side with Lincoln in l'affaire Vallandigham. Conversely, several of the members of the opposition party, like the colorful Thomas D'Arcy McGee, publicly courted and publicly supported the exile. Vallandigham, meanwhile, passed through Montreal and Toronto on his way to Hamilton.18 There he changed trains for Niagara, arriving at the depot early on the morning of July 15. He hurried to the Clifton House and secured quarters there -- the Clifton House would be his |

|

Canadian base until August 1. He found several American friends already in Niagara, impatiently awaiting his arrival. Daniel Voorhees, Indiana congressman and a bold critic of the Lincoln administration, had arrived on the thirteenth and had taken a room at the Stephenson House. Richard T. Merrick, a self-styled "peace man" from Chicago, brought a message from the editor of the Chicago Times. Joseph Warren, editor-publisher of the Buffalo Courier, crossed into Canada to give his fellow Democrat a greeting. Then there were some Ohio friends from Dayton and Cincinnati. Altogether, they comprised a good-sized reception committee.19 Even before he arrived in Niagara, Vallandigham had prepared "an address," a document in which he accepted his party's gubernatorial nomination and in which he enumerated the basic issues of the political |

VALLANDIGHAM AS AN EXILE 157

campaign. In his "Address to the

Democracy of Ohio," Vallandigham

donned the cloak of the martyr. He

criticized President Lincoln for tramp-

ling upon traditional liberties and

establishing a military despotism. He

advocated peace and reunion

"through compromise." The "Address," in

effect, served as the political platform

upon which the exile sought the

governorship of Ohio. It exhibited no

trace of bitterness, for Vallandigham

had a blind faith in himself and his

views, believing that time would vindi-

cate him and incriminate his enemies.

After Richard Merrick, on a mission for

the Chicago Times, and Joseph

Warren, editor of the Buffalo

Courier, received copies of Vallandigham's

"Address to the Democracy of

Ohio," they shuffled off to Buffalo. Merrick

hustled to the telegraph office to try

to transmit a copy of the "Address"

to the Chicago Times, but the

partisan-minded telegraph operator refused

to send Vallandigham's composition over

the wires, for he believed it a

treasonable document. Merrick then put

the "Address" back in his

pocket and took the next train to

Cleveland -- there the telegraphic opera-

tor would also refuse, and the Chicagoan

would board the next train

bound for his home town.20 Warren

of the Buffalo Courier, meanwhile,

hurried to his print shop to have

Vallandigham's "Address" set in type

and published in the morning issue of his

newspaper. Warren and the

Courier, thus, scored a scoop. Before the week was over,

however, nearly

every Democratic party organ in the

United States, and most Canadian

newspapers as well, published the

"Address to the Democracy of Ohio"

which the exile had issued from his base

in Niagara, Canada West. Even

George Brown of the Toronto Globe published

the "Address" -- without

editorial comment.21

Vallandigham's bid for publicity

coincided with news of draft riots

emanating from New York City. Canadian

newspapers gave much more

space to the New York draft riots of

July 13-16 than to Vallandigham

and his "Address." Most

Republican newspapers in the United States, on

the other hand, denounced both

Vallandigham and his "Address." Some

even charged that the ostracized Ohioan

had connived with Confederate

agents to plan the New York draft riots,

publishing a forged letter to

give respectability to their lies. For

good measure, Republican editors

charged that the Confederate invasion of

Pennsylvania, which ended

disastrously at Gettysburg, had been

suggested by Vallandigham while

he was an exile in the Confederacy. The

same was said of the raid of

Confederate cavalry commander John H.

Morgan into Indiana and Ohio

-- the Morgan raid supposedly being a

signal for Vallandigham's followers

to rise in revolt and establish a

"Northwest Confederacy."22 Vallandigham,

of course, was incensed at the lies

manufactured about him. He termed

those linking him to the Morgan raid

both "ridiculous and desperate,"

and he, as always, believed that time

would vindicate him and unmask

his calumniators.23

News from the States was not fully

favorable to Vallandigham's candi-

dacy for the governorship of Ohio. The

Union victories at Gettysburg

158 OHIO HISTORY

and Vicksburg curbed peace sentiment,

for the crusade for compromise

fluctuated with the vicissitudes of war,

increasing with Union defeats

and diminishing with Union victories.

John Brough, the Republican candi-

date who competed with Vallandigham for

the governorship of Ohio,

campaigned zealously and effectively,

labeling the exile a traitor. Several

prominent Ohio Democrats sulked in their

tents, preferring Brough to

Vallandigham. Rumors made the rounds

that Democratic party strategists

tried to get the exile to withdraw from

the gubernatorial contest, giving

the nomination to someone who had a

better chance of being elected.

One very prominent Ohio Democrat was

reported to have conceded the

election and to have predicted

Vallandigham's defeat by 50,000 votes.24

Vallandigham tried to rally the

Democratic forces in Ohio by writing

letters to be read at party rallies or

published in the press. Occasionally,

Ohio Democrats visited Vallandigham at

his Canadian retreat to refill

their cup of hope. There were other

visitors, too. The exile's wife and

ten-year-old son came up from Dayton for

an extended visit. Judge

John C. Fulton, of nearby Erie County,

arrived with a band of Democratic

pilgrims anxious to visit their prophet;

after imbibing freely of Canadian

whiskey the celebrants talked of hanging

abolitionists and enthroning

Vallandigham.25 The editor of

the St. Catharines Evening Journal wrote,

"Yankees can't stand Canadian

whiskey. There is too much fight in it."26

Quite a number of Canadians visited the

Clifton House to see the fellow

who had stirred up such a fuss in his

own country and who styled himself

a martyr to free speech. Charles Lindsey, editor of the

Toronto Leader,

stopped at the Clifton House while

taking a trip to Buffalo. The trip

turned into a busman's holiday, for

editor Lindsey reported on his visit

with Vallandigham to his readers. He

found the exile "exceedingly amiable

in disposition," a "through

gentleman, " and a fellow possessing "great

probity" and a superior intellect

-- Republican critics had led him to

believe he would meet an ogre or a barbarian.27

George Brown, who edited the Globe and

supported the John Sandfield

Macdonald ministry, could not pass by an

opportunity to jab his fellow-

editor and slap Vallandigham. Brown, who

had set a rather raucous tone

for politics, criticized Canadians who

"toadied" to the exile, fussing and

courting him in Quebec or Niagara. He

advised his readers to treat

Vallandigham "with civility,"

but in view of his anti-British tirades and

his "scurrilous tongue,"

Canadians ought not "fawn over him" or pay

homage "in the slightest

degree." Brown charged that, early in the war,

in his comments upon the Trent affair,

Vallandigham had insulted England

and used invective against Her Majesty's

government. "If it had been

possible to bring on a war between

Britain and America," editorialized

Brown, "Vallandigham is the man who

would have done it."28

Neither Vallandigham the exile nor

Lindsey of the Leader relished

Brown's double-barreled blast against

them. The irritated exile composed

an anonymous letter, signed "An

American," and gave it to Lindsey when

the editor of the Leader passed

through Niagara on his way back from

VALLANDIGHAM AS AN EXILE 159

Buffalo. Lindsey published

Vallandigham's short letter, withholding the

identity of the author from his readers.

The letter called Brown's charges

"unjust in temper and spirit"

and erroneous as to fact, contending that

the Globe had been guilty of

misquoting as well as selecting from context

to pervert meaning. It chided Brown and

the Globe for taking the side

of Lincoln and the abolitionists and for

assailing a man of courage who

was a martyr to the cause of civil

rights. The letter-writer promised to

obtain exact quotations from

Vallandigham's speeches in congress and

to prove Brown and the Globe in

error.29

Brown refused to retreat. In the

editorial columns of the Globe he

restated his contention that the exile

should not be "feted, caressed, and

petted." Then Brown quoted at

length from Vallandigham's speeches of

December 1861 and January 1862 in

congress. He omitted quotation

marks within one of Vallandigham's

statements to make a better case

against him. "He is a well-known

Anglophobiac," concluded Brown, "who

never missed a chance of libelling Great

Britain, until he had to fly to

her dominions for safety."30 Some

of Brown's political allies, all sym-

pathetic to John Sandfield Macdonald's

government, joined in the attack

upon Vallandigham and the Canadians who

had befriended him. The

editor of the London Free Press ridiculed

the Grand Trunk Railroad for

playing "the lackey" to

Vallandigham, while the editor of the Chatham

Patriot parroted the Globe's comments. "For our

part," stated an editorial

note in the Patriot, "we

look upon Mr. Vallandigham as being as great

a rebel at heart against the United

States as Jefferson Davis." That editor

thought that Vallandigham should have

shown his true colors by enlisting

in the Confederate army. Furthermore,

the editor of the Patriot wondered

why some "Grit organs," like

the Chatham Journal and the Toronto

Leader, sympathized with slavery, secessionism, and Satan.31

Vallandigham, meanwhile, wrote to a

former congressman friend to

beg for a copy of the official

proceedings of the United States Congress

of 1861-62, for he wanted the documents

which would enable him to

reply more specifically to Brown's

charges. He wanted to prove that

Brown had misquoted him and had dropped

quotation marks in the

process.32 The exile also

sought new quarters, for the keeper of the

Clifton House no longer viewed Vallandigham

as a desirable tenant. It

was reported that Lord Lyons, British

minister to the United States,

William H. Seward, and other officials

would visit Niagara Falls and take

a trip to Toronto. The Clifton House

could well serve as their Canadian

headquarters, but it would be

unthinkable for Seward and Vallandigham

to be under the same roof or in the same

hotel.33 Furthermore, some one

thousand or more persons had stopped at

the Clifton House over a two-week

period, either to visit Vallandigham or

gape at him -- perhaps to see

if he possessed horns and a forked tail.

Sometimes the American pilgrims

drank too much liquor and embarrassed

both Vallandigham and the

proprietor of the Clifton House.34 So on

August 1 the exile moved from

the Clifton House to the Table Rock

Hotel, an inn and curio shop operated

160 OHIO HISTORY

by Saul Davis on the outskirts of

Niagara. Vallandigham, however, was

not fully satisfied with his new

quarters, and he soon took a scouting

trip to Windsor, opposite Detroit, to

investigate the possiblity of moving

his base to that community.35

Early in August, Vallandigham had a

second opportunity to meet

some of the most notable Canadians of

his day. Edward W. Watkin, the

English financier and promoter, led a

delegation of prominent Quebec

citizens to Niagara Falls, to meet

Charles Mackay, then living in New

York City as the correspondent of the

London Times. Watkin's party

included Thomas D'Arcy McGee, who had

combined literature and politics

with unusual success, and Charles J.

Brydges, who had honored Vallan-

digham with a party at the Stadacona

Club when the exile first came

to Quebec. It also included Alexander G.

Dallas, onetime chief factor of

the Hudson's Bay Company, but at the

time serving as governor of Prince

Rupert's Land, and Professor Henry Y.

Hind, whose reports on the

land lying between Winnipeg and the

Rockies stirred the imagination of

Canadians and made his name a household

word. Watkin, leader of the

deputation, was in the midst of

negotiations to transfer the vast holdings

of the Hudson's Bay Company to the

English government. Watkin and

McGee, setting the stage for the

possible unification of Canada, hoped

to persuade Mackay to endorse their

plans and to lay their "new schemes"

before the English people through the

London Times.36 Vallandigham,

quite by accident, would be in the

vicinity where historic events were

being planned and discussed and where

the dream of a new Canada

was being expressed and advanced.

While waiting for Mackay to come from

New York City, Watkin and

McGee hunted up Vallandigham and enjoyed

a most pleasant visit. McGee,

who had once resided in the States

(editing newspapers in Boston and

New York City), had many questions to

ask about the Irish element in

Ohio and the Midwest. McGee knew that

most Irish-Americans in the

States voted the Democratic ticket,

opposed emancipation of the slaves,

and sympathized with Vallandigham. McGee

and Watkin invited Vallan-

digham to accompany them to a

"Reform Pic-Nic" or a "Clear Grit

gathering" at nearby Drummondville.

The next morning Watkin, McGee,

and Dallas called for Vallandigham in a

carriage and the four observers

went to view a Canadian political rally.

Two thousand carriages and

wagons took part in a three-mile-long

procession which ended in Kerr's

Grove near Drummondville. The political

rally featured several speakers,

half a dozen bands, and a sumptuous

dinner.37 Vallandigham and McGee

had places of honor on the platform. The

affair must have reminded

Vallandigham of happier days, when he

was so often the lion of the

occasion at political rallies in Ohio.

Charles Mackay of the Times also

had a chance to meet Vallandigham

and exchange pleasantries. Mackay noted

that United States spies, pro-

fessional and amateur, were as thick as

flies in the Niagara area. They

"hung around" the hotel, some

sitting "Yankee fashion," "balancing their

VALLANDIGHAM AS AN EXILE 161

chairs." They jotted down with whom

Vallandigham walked and with

whom he talked; they relentlessly sought

the names of those who dined

with the exile.38

As soon as Mackay returned to New York

City and Watkin's contingent

departed for Quebec, Vallandigham wrote

his second letter to the editor

of the Toronto Leader. The

documents he had previously requested of

his congressman-friend had belatedly

arrived, so Vallandigham set to

work to prove that Brown of the Globe

had misquoted him and mis-

represented his stand of January 1862.

The exile pointed out that, by

omitting quotation marks, Brown had

attributed someone else's state-

ments to Vallandigham -- "creating

prejudice against a stranger and

an exile" who had sought the

protection of a foreign flag. Again Vallan-

digham retained his anonymity, once more

signing the letter "An Ameri-

can."39 The exile's able

epistolizing put Brown at a disadvantage, and

several Canadian editors rebuked both

Brown and his Globe. The Toronto

Patriot and the St. Catharines Journal, for example,

jeered Brown after

Vallandigham had pinned him to the

mat.40 But Brown still refused to

retreat. He boldly and baldly restated

his contention that Vallandigham

was "a traitor to his own

people" as well as "a bitter enemy of England."41

While carrying on his war of words with

Brown and the Globe, Vallan-

digham gave considerable attention to

his campaign for the governorship

of Ohio. He continued to write letters

to be read at political rallies and

to encourage his friends to increase

their efforts in his behalf. His quiet

confidence and his implicit faith that

truth and Vallandigham would

triumph served to inspire the many who

called to renew their political

faith or shone through the letters he

wrote to his Ohio friends.42

In mid-August Vallandigham took time out

from his campaign activities

to visit Quebec again. Mr. and Mrs.

Vallandigham, their son Charles,

and some Ohio friends started the long

and leisurely trip down the St.

Lawrence River.43 The forest-covered

shores and the enchanting scenery

entranced the travelers and turned their

attention away from the world

of harsh reality.

On the evening of August 18, the

travelers arrived in Quebec and

secured quarters at the St. Louis Hotel.

The exile then had a chance to

get reacquainted with some of his Quebec

friends. Thomas D'Arcy McGee

invited Vallandigham to visit the

legislative assembly, then in session.

On the evening of the nineteenth, the

exile occupied a seat in the legislative

assembly, to the left of the speaker.

The visitor witnessed a long and

lively session -- one which began at

three o'clock in the afternoon and

continued more than an hour beyond midnight.

McGee, the exile's host

on the floor, challenged the ministry on

the contested Essex election. It

was one of the finest orations of the

entire session. Cheers, laughter, and

applause punctuated McGee's oratorical

effort, and shouts of "No! No!"

and "Hear! Hear!" came more

often than usual.44 Supporters of the

John Sandfield Macdonald government also

had their say as the debate

grew more heated and more bitter. The

very narrow margin which

162 OHIO HISTORY

Macdonald's Liberal party held in the

house during the eighth parliament

made every debate and every question the

more important. The government

successfully postponed the decision in

the contested Essex election, per-

haps recalling to Vallandigham the time

he had contested an election

and had to wait nearly six months for a

favorable decision.

The next day Vallandigham again visited

the legislative assembly as

McGee's guest. This time the exile heard

the Irish-Canadian orator defend

him and castigate his Canadian critics.

Earlier McGee had written a

letter to the editor of the Montreal

Gazette about rumors that an invasion

from the United States was a

possibility. The New York Herald had

engaged in fist-shaking at Canada, and

the United States seemed to be

in a hurry to complete Fortress

Montgomery at Rouse's Point, but

forty-five miles south of Montreal.

Back-alley rumors in Washington, D. C.,

also referred to plans for an invasion

of Canada. McGee's letter of August

8, 1863, to the editor of the Montreal

Gazette brought the rumors above-

board: "The plan contemplated at

Washington for the invasion of Canada

is to march 100,000 men up to the

district of Montreal to cut the connec-

tion between Upper and Lower Canada . .

. and to force a separation of

the provinces."45 McGee's

chief motive for airing the rumors seemed to

be to embarrass the government and to pressure

the ministry to reconsider

the "Militia Bill" -- the very

measure upon which the John Sandfield

Macdonald government had fallen the

previous May. George Brown, who

used the influence of the Toronto Globe

to prop up the Macdonald ministry,

seized upon McGee's letter to ridicule

the letter-writer and to slap Vallan-

digham again. Brown sarcastically

suggested that Vallandigham had

served as McGee's "chief

informer" and that the exile had a surreptitious

pipeline to Washington.46 With

Vallandigham sitting at his elbow, McGee

explained to the assembly why he had

written his letter of August 8

to the Montreal Gazette. Then he

stated that the informant was a minister

in the cabinet (Luther H. Holton) and

not Vallandigham. He then paid

his respects to "the honorable

exile" and spanked Brown and the Globe

for violating the principles of

hospitality and decency. The Globe, said

McGee, made an "unfair, ungenerous

attack upon a stranger seeking a

secure and quiet refuge" in Canada

-- "he had come within our gates

asking only a peaceful home which his

country had denied."47 It was

sweet music to the exile to hear one of

the most brilliant orators who

ever graced Canadian public life

befriend and defend him. Several

Canadian newspapers followed McGee's

lead, also defending Vallandigham

and scolding Brown -- it was no

coincidence that each of these papers

opposed the Macdonald government. "Il

ressort done de tout cela," wrote

the editor of Le Journal de Quebec,

"que M. Vallandigham n'est pas un

delateur et que le Globe est un

calomniateur."48

After his public vindication,

Vallandigham and his family headed for

Windsor, the small city he had selected

as his new Canadian base.49 He

arrived at the Grand Trunk depot in

Windsor early in the evening of

August 24, quite unnoticed and

unheralded. With carpetbag in hand

VALLANDIGHAM AS AN EXILE 163

(and accompanied by his wife, son, and

sister-in-law), he walked to the

Hirons House, at the corner of Sandwich

and Quellette streets, a short

block south of the depot.

A Canadian editor, who happened to

witness the exile's arrival in

Windsor, thought him "an ordinary

looking fellow" -- one whom a

phrenologist would have judged to

possess but little "caution, conscientious-

ness, or veneration." "On the

whole," the editor observed, "Vallandigham

looks more the foreigner than the

Yankee."50

The American exile found Windsor to be a

friendly city of about three

thousand residents. Its proximity to

Detroit meant that Michigan Demo-

crats would come to call, and its

nearness to Toledo gave Ohio Democrats

a chance to communicate readily.

Vallandigham rented a two-room suite

on the second floor of the Hirons House.

His reception room faced the

river, affording the occupant a splendid

view of the city of Detroit. He

could also see the United States gunboat

Michigan moored in the middle

of the stream. The ship's shotted

Dahlgren seemed to bear upon his

bedroom window. The Michigan symbolized

the armed might of the

United States -- a might that could be

used to keep him from setting

foot upon his country's soil.

Vallandigham's arrival in Windsor

alarmed federal authorities in

Detroit, and they asked their superiors

what to do if he crossed the

river. "If Vallandigham

crosses," replied one superior, "he is to be at

once arrested and sent under a strong

guard direct to Fort Warren."51

Some of the bolder Democrats of the

Midwest wanted Vallandigham to

defy federal authorities and return to

claim the rights and privileges to

which he was entitled as a citizen of

Ohio and the United States. By

tarrying in Canada and refusing to claim

his rights, wrote the editor of

the Chicago Times, Vallandigham

forfeited the support of the Ohio

Democracy.52 The editor of

the Democratic-oriented Detroit Free Press

used Vallandigham's arrival in Windsor

as an excuse for another attack

upon President Lincoln. "He

[Vallandigham] was arrested," editorialized

Henry Walker, "for no crime known

to the law, tried by no tribunal

recognized as having any cognizance of

crimes committed by man in

civil life, sentenced to a punishment

never heard of in any free country,

and arbitrarily changed by the President

to one not recognized by the

Constitution."53

The day after Vallandigham's arrival at

Windsor, a three-man com-

mittee of Detroit Democrats called upon

the exile to arrange for an

official welcome. Then, that evening,

Judge Cornelius Flynn of Detroit

led "a welcoming party" across

the river and to the Hirons House.

Judge Flynn, as spokesman for the

delegation, assured the exile that

posterity would depict him as a fearless

champion of civil rights and

dauntless defender of constitutional

privileges. He assured Vallandigham

that his stay in Windsor would be brief

-- until Ohio citizens repudiated

"the unfaithful public

servants" at the polls on October 13. The exile

replied briefly and moderately. He

counseled obedience to the constitution

VALLANDIGHAM AS AN EXILE 165

and the laws, stating that the ballot

was the true and proper remedy

to regain liberty and effect reunion.

There was no trace of bitterness,

but a quiet confidence that the future

would right wrongs and repay him

in full measure.54

In the days which followed, an almost

unbroken string of visitors--

admirers mixed with the curious--beat a

path to Vallandigham's door.

Once, for example, a force of Toledo

firemen, in Detroit for some com-

petitive games, crossed the river to

give "three cheers" for Vallandigham

and free speech.55

Ohio Republicans who wanted Vallandigham

disgraced and defeated

on October 13 expressed indignation over

the compliments paid to the

exile. "He has changed his

base," wrote a Republican editor who noticed

that Vallandigham had moved from Niagara

to Windsor, "but not his

baseness."56 The

Republican-minded editor of the Cleveland Leader wrote

of the many "skedaddlers" from

the North and the numerous "blackguards"

from the South congregating in Windsor.

"Probably the society of these

scoundrels," wrote the editor,

"is what attracts the banished convict to

Windsor."57 To radical

Republicans, the terms "Vallandigham" and "trea-

son" were synonymous.58

In the weeks preceding the October 13

elections, the tide began to

turn sharply against the exile.

Effective Republican campaigning, coupled

with Union military victories,

brightened Lincoln's sky and darkened

Vallandigham's hopes of victory.

Prospects of a civil war in Ohio if

Vallandigham were elected scared the

wary and caused them to vote

against the exile.59 Then

too, war prosperity and good wheat prices helped

the Republicans. The generation of nationalism

made many view the

Lincoln administration and the

government as one. Lincoln's party, thus,

held all the trump cards--having the

money, the energy, and patriotism

on its side.60

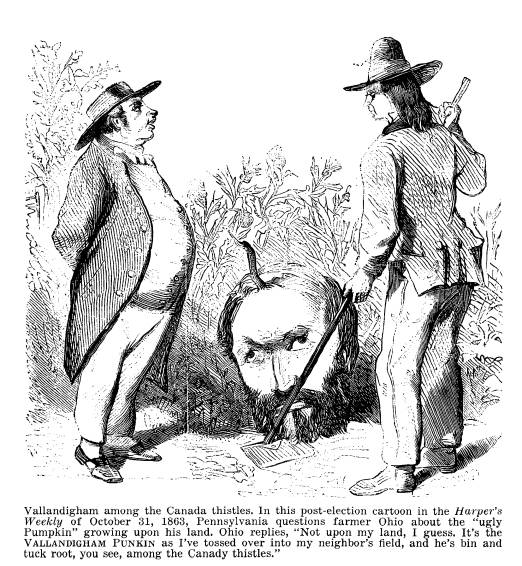

October 13 proved to be an unlucky day

for Clement L. Vallandigham.

Although he polled a surprising number

of votes--more than any other

losing candidate in the history of Ohio

gubernatorial elections--the

exile went down to defeat by 100,000

votes. President Lincoln, jubilant

over the election returns in Ohio, sent

a telegram to the governor of the

state: "Glory to God in the

highest. Ohio has saved the Union."61 George

Brown of the Globe also expressed

pleasure with the exile's defeat; he

gazed into his crystal ball and

prophesied that the Ohio election returns

would enhance Lincoln's chance of being

reelected in 1864.62 Time proved

Brown to be a true prophet.

After Vallandigham's defeat in the Ohio

gubernatorial contest of

October 13, Canadians promptly lost

interest in the exile--the election

returns had the effect of transforming a

prominent person into a nonentity.

Even for Vallandigham, the months which

followed the election were

anti-climactic. He, however, seemed to

accept his defeat in good grace

and he urged his Ohio friends to renew

faith in their time-tested principles

and await the day when reason would push

emotion aside.63 He exchanged

|

letters with William C. ("Colorado") Jewett, a self-styled "peace emissary" who dreamed that Emperor Napoleon III might restore the Union and end the war through mediation.64 On November 14 a large group of students from the University of Michigan visited the exile. His advice was like that of a father to a son--study hard, aspire to lead a goodly life, be patriotic, cultivate courage, and adhere to principles at all costs. "It is easy to be a politician or a demagogue," he told the attentive students. "It is easy to sail with the wind or float with the current."65 Unwittingly, he was but justifying his own course. As usual, Vallandigham devoted much of his time to reading and study. He had a genuine love of the classics and he combed them for quotations to incorporate into his speeches or letters. He had an especial fondness for biography and for history, and he drank from the wellsprings of history to justify his own course of action. The Christmas season came |

VALLANDIGHAM AS AN EXILE 167

in with the end of the year, heralded by

heavy snowfalls and wintry blasts.

He spent a lonely Christmas, separated

from his wife and son, who had

returned to Dayton and Ohio in late

September. The halo of the martyr

lost some of its glow. The American

shore seemed farther away than

it had when he first arrived in Windsor,

and the U.S.S. Michigan, still

anchored in the river outside his

window, reminded him that he was

an exile and that fate had frowned upon

him.

He hoped against hope that the supreme

court of the United States

might bring him vindication. Through his

attorney, Vallandigham had

earlier applied for a writ of certiorari

to review and annul the proceedings

of the military commission which had

"illegally" tried him in an area

where the civil courts were open. The

United States Supreme Court,

however, side-stepped the question,

decided it lacked appellate jurisdiction

in such cases, and avoided a clash with

the military while the war was

in progress.66 "The

Supreme Court," wrote one of Vallandigham's Ohio

friends, "has no jurisdiction in

matters of individual liberty, unless the

party claiming redress can prove that he

was outraged according to law!"67

During the early months of 1864 word

reached Windsor that mobs,

usually led by furloughed Union

soldiers, had destroyed a half dozen

Democratic newspaper offices in the

upper Midwest. Even the office of

the Dayton Empire, a paper which

Vallandigham had once owned and

edited, felt the vengeance of King Mob.

Rioters, invading the office and

the printing plant, destroyed much of

the equipment and threatened to

hang the editor.68 Vallandigham, who had

previously claimed to revere

the law and the constitution, joined the

Democrats who were preaching

the law of reprisal, advocating "instant,

summary and ample reprisals

upon the persons and property of the

men . . . who, by language and

conduct, are always inciting these

outrages."69

Some Democrats felt that their safety

lay in organizing a secret society,

one that would serve both as a mutual

protection society and as an organi-

zation to advance their party's

fortunes. It would serve the Democratic

party as the Union League had so

effectively served the Republican party.

Four midwestern Democrats devised such a

paper organization and went

to Windsor to persuade Vallandigham to

accept the headship. Thus, by

waving a wand, the Sons of Liberty came

into being and the exile

assumed the title of "Supreme

Commander." Vallandigham, as titular

head of the Sons of Liberty, never

issued an order or called a meeting.

Yet he, like the few who belonged to the

paper-based organization, wanted

Republicans to believe that a widespread

secret Democratic society existed

to defend civil rights, secure free

elections, and advance the party's wel-

fare.70 The public utterances

of Vallandigham and the handful who

belonged to the Sons of Liberty helped

to write another myth into Civil

War history.71

Vallandigham, meanwhile, grew restless

in his Canadian retreat. He

wanted to return to Ohio to engage in

the crusade for peace and com-

promise--he had become the symbol of

that movement. He wanted to

168 OHIO HISTORY

exert influence in the coming

presidential contest. It was worth risking

re-arrest to remove the cloak of

anonymity which his absence from Ohio

had cast over him. Furthermore, his

mother was seriously ill--she would

not have long to live--and he was tired

of the long absence from home

and family. Then too, Confederate agents

in Windsor embarrassed him

and gave his critics a chance to claim

that Vallandigham was willing to

play their game. There was also the

possibility that President Lincoln

might ignore him if he returned or might

fear to re-arrest him. The exile,

therefore, decided to leave Canada and

return to Ohio.

During the night of June 14 Vallandigham

crossed the river and took

a train out of Detroit headed for Toledo

and Ohio. A disguise enabled

him to escape the detection of the ever

watchful United States agents.

The next day he appeared at a huge

Democratic rally in Hamilton, Ohio.

"He came unheralded from his

exile," wrote a devotee of Vallandigham,

"and his sudden appearance was like

an apparition from the clouds."72

Canadian newspapers which had not

mentioned Vallandigham's name

for months, reported on the exile's

return to the States. Some even sum-

marized the speech he gave at Hamilton,

Ohio, and reported that United

States agents did not arrest him.73

After his return to his home and his

country, Vallandigham resumed

the practice of law and again became the

stormy petrel of Ohio politics.

But in the days which followed he never

again twisted the tail of the

British lion as he was wont to do in his

earlier political career. Perhaps

he felt he owed a debt of gratitude to

Canada for allowing him to live

in that country for almost a year. He

owed a debt to Thomas D'Arcy McGee

and other prominent Canadians who had

befriended and defended him.

"La reconnaissance," Jean Baptiste Massieu had earlier written to the

Abbe

Sicard, "est la memoire du

coeur."74

THE AUTHOR: Frank L. Klement is a

professor of history at Marquette

Univer-

sity and the author of The

Copperheads in

the Middle West.

|

|

|

VALLANDIGHAM AS AN EXILE IN CANADA 1863-1864

by FRANK L. KLEMENT

While Clement L. Vallandigham lived in Canada for nearly a year during the Civil War as an exile from the United States, his path crossed those of a number of men well-known in Canadian history. Thomas D'Arcy McGee, emerging as a critic of the Canadian government, befriended and defended the exile. Charles J. Brydges, superintendent of the Grand Trunk Railroad, gave a dinner in Vallandigham's honor and presented him with a pass on his railroad. And George Brown, the influential editor of

NOTES ARE ON PAGES 208-210 |

(614) 297-2300