Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

|

|

|

THE ODYSSEY OF PETROLEUM VESUVIUS NASBY

by DAVID D. ANDERSON |

|

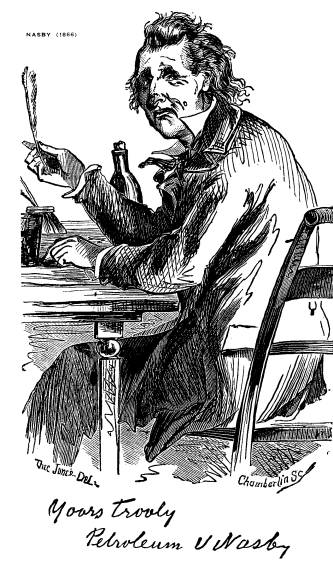

After more than a century the American Civil War remains garbed in tragedy and pathos, heroes and hero worship, sentiment and cynicism, as it has been since the guns fell silent and the printing presses began to pour out a still unabated torrent of memoirs, histories, and biographies. As an age of heroes, it is resplendent with the names of Lincoln, Grant, Lee, Sherman, Sheridan -- and Petroleum Vesuvius Nasby. Perhaps the least remembered of these is Nasby, although he, like the others, came out of obscurity to fame in the four years of the war. Yet, in spite of the shadow into which he has again passed, Nasby deserves inclusion in any list of the war's great men: he is our only authentic Civil War anti-hero. Nasby began his anti-heroic march, not in the ranks of either army, but in a long series of letters that began to appear with regularity on April 25, 1862, in the Hancock Jeffersonian of Findlay, Ohio.1 His attainment of

NOTES ARE ON PAGE 279 |

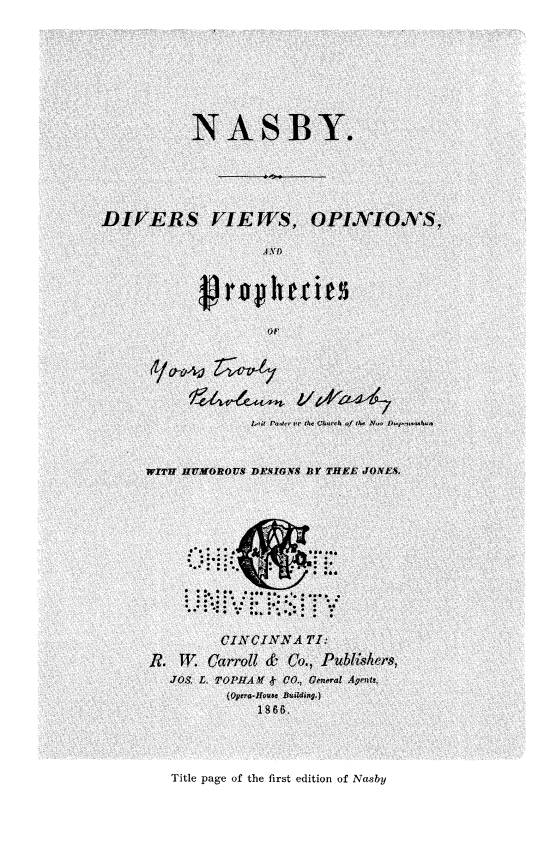

PETROLEUM VESUVIUS NASBY 233

the heights -- or depths -- of

anti-heroism is made dramatically clear in his

own contribution to Civil War

literature, the collection of these letters

and others, published in 1866 as Nasby:

Divers Views, Opinions, and

Prophecies of Yoors trooly Petroleum

V Nasby.

Differences abound between the letters

as they appeared in the papers

and as they appear in the book;2 Nasby,

following the prerogative of

statesmen in every age, adapted the record

to his own purposes. But both

letters and book agree that Nasby was

the self-styled spokesman of the

midwestern Peace Democrats, who, under

the leadership of Clement L.

Vallandigham, sought to bring the war to

a quick end. Nasby further

clouded an already obscure program that

would neither resolve the con-

stitutional crisis of secession nor, in

all probability, restore the rapidly

disintegrating Union.

The letters and book also agree that

Nasby was, as he proclaimed him-

self to be, a patriot, a Democrat, a

Jeffersonian, and finally a clergyman.

They reveal, too, what he did not

proclaim: that he was a lazy, illiterate,

cowardly, alcoholic seeker of political

patronage and booty, a racist, an

unscrupulous opportunist, and the focal

point of often bitter but always

pointed and humorous political satire.

Actually the emergence of Nasby from

obscurity into notoriety marked,

also, the emergence of a brilliant

satirical talent devoted to the preservation

of the Union. Nasby was the fictional

creation of an Ohio newspaperman,

David Ross Locke, who was born September

20, 1833, at Vestal, New

York. An itinerant printer in upstate

New York and western Pennsylvania,

Locke came to Ohio late in 1852, helped

establish the Plymouth Advertiser,

worked on the Mansfield Herald, and

on March 20, 1856, became editor

of the Bucyrus Journal.3 His

introduction to Ohio journalism, within a

comparatively few miles of the Wingert's

Corners that the book was to

make famous, is reflected in the

emergence of Nasby.

In politics Locke was a strong

antislavery Whig who joined forces with

the Republicans as an anti-Nebraska man.

A product as well as a practi-

tioner of the no-holds-barred school of

politics and journalism of the

1850's, Locke was eminently suited to

satirize and berate the Democratic

opposition in the western tradition that

the character of Nasby represents.

This political tradition, the result of

frontier individualism and Jacksonian

democracy, not only influenced Locke and

consequently produced Nasby,

but it was also the tradition that

produced the new president, Abraham

Lincoln.

Crawford County, of which Bucyrus is the

seat, was a Democratic

stronghold, as Locke must have learned

immediately after arriving there.

It had given its vote to every

Democratic presidential candidate from

Andrew Jackson to Stephen Douglas.

Wingert's Corners was a crossroads

village in the northwestern part of the

county, and because it was a center

of county Democratic politics as well as

the subject of much condescending

humor from the county seat, it was

perhaps inevitable that Locke should

eventually select it as Nasby's home.4

234 OHIO HISTORY

Although Locke left Bucyrus in the fall

of 1861 to accept and then

resign a commission in a newly raised

infantry regiment, he turned up

in Findlay a month or so later as editor

of the newly revived Hancock

Jeffersonian, the paper in which he introduced the inimitable Nasby.5

But

the groundwork had been laid in Bucyrus,

both in Locke's grasp of the

nature of the Copperhead movement and

his use of satire as a weapon

against it. In the Bucyrus Journal for

December 13, 1860, he had included

an unsigned, undated letter headed

"Secession in a New Spot,"6 in which

he began to satirize the peace movement,

the Democrats, and the secession

movement. However, Nasby, the character

who was to grow in stature

until in the popular mind he merged with

and eclipsed Locke's own per-

sonality, was not born until the first

Nasby letter appeared in the Hancock

Jeffersonian.

But the odyssey of Nasby as he fought

what he considered to be the

good fight with minimum exposure of his

own person to danger is best

followed not in Locke's career but in

Nasby's own "war memoirs," the

volume of 1866 containing his war

letters. The book begins with an adap-

tation of Locke's earlier, non-Nasby

ordinance of secession, rewritten in

Nasby's own inimitable style. In the

ordinance, a stirring (to Nasby),

mocking (to Locke) declaration, the grievances

of Wingert's Corners and

of Nasby himself are enshrined in

history:

TO THE WORLD!

In takin a step wich may, possibly,

involve the state uv wich we hev

bin heretofore a part into blood and

convulshuns, a decent respeck for

the good opinion uv the world requires

us to give our reasons for

takin that step.

Wingert's Corners hez too long submitted

to the imperious dictates

uv a tyranikle goverment. Our whole

histry hez bin wun uv aggreshn

on the part uv the State, and uv meek and

pashent endoorence on ours.

It refoosed to locate the State Capitol

at the Corners, to the great

detriment uv our patriotic owners uv

reel estate.

It refoosed to gravel the streets uv the

Corners, or even re-lay the

plank-road.

It refoosed to locate the Penitentiary

at the Corners, notwithstandin

we do more towards fillin it than any

town in the State.

It refoosed to locate the State Fair at

the Corners, blastin the hopes

uv our patriotic groserys.

It located the canal 100 miles from the

Corners.

We hev never hed a Guvner,

notwithstandin the President uv

this meetin hez lived here for yeers, a

waitin to be urgd to accept it.

It hez compelled us, yeer after yeer, to

pay our share uv the taxes.

It hez never appinted any citizen uv the

place to any offis wher

theft wuz possible, thus wilfully keepin

capital away from us.

It refoosed to either pay our rale-rode

subscripshun or slackwater

our river.

236 OHIO HISTORY

Therefore, not bein in humor to longer

endoor sich outrajes, we

declare ourselves Free and Independent

uv the State, and will maintain

our position with arms, if need be.

Next day, Nasby avers, the Corners

raised a company "uv minit men . . .,

and wun uv 2 minit men. The seceshn

flag, muskrat rampant, weasel

couchant, on a field d'egg-shell, waves

from both groserys. . . . We are

in earnest. Armed with justice and

shot-guns, we bid the tyrants defiance."

He concludes:

P.S. -- The feelin is intense -- the

children hev imbibed it. A lad

jest past, displayin the seceshn flag.

It waved from behind. Disdainin

concealment, the noble, lion-hearted boy

wore a roundabout. We are

firm.

N.B.--

We are still firm.

N.B., 2d. -- We are firm, unyeeldin,

calm, and resoloot.

From this point the Nasby letters follow

in parallel the course of antiwar

feeling in the North, while at the same

time they grow in intensity to

the point where Locke the satirist

almost disappears and Nasby takes on

depth and breadth as the ignorant,

illiterate spokesman of northern Cop-

perheads and southern secessionists. At the

same time, Nasby becomes

increasingly an individual in his own

right, pathetic, despicable, and

somehow appealing as he issues

proclamations and undergoes the vicissi-

tudes inherent in devotion to his cause.

In June 1862, just before the crucial

congressional elections when the

Republicans were trying to extend their

control over congress, Nasby

went to Washington to interview his

hero, Clement L. Vallandigham, then

congressman from Ohio's third district

and a candidate for reelection.

As he stands in the shadow of the

capital, Nasby meditates:

I am in Washington. I stand under the

shadder uv the tempel uv

Liberty, and am reposin my weery lims in

kool shades of Fredom.

But I cant reelize that this is the saim

Washington I yoost 2 visit.

I yoost to go frum Pennsilvany to the

cappytle wunst a year, to git

my stock uv Dimocrisy recrootid, and to

find out what we wuz expectid

to bleeve doorin the cumin year, thus

gettin full 6 munths ahed uv

my nabers. I wuz wunst electid gustis of

the peese in Berks County,

by knoin neerly a year in advanse what

we wuz to vote for that

autum. They thot Nasby wuz a smart man.

Because Nasby was not merely a complete

scoundrel but an appealing

one, it was perhaps inevitable that he

would become popular, both in his

native Ohio and in the threatened

capital at Washington. As effective as

the portrayal was in satirizing both the

principles and the character of

the secessionists, it was at the same

time a familiar one to the westerner,

whether in an Ohio town or in the White

House. Nasby was the fumbling,

unscrupulous political opportunist to be

found in every county seat as an

PETROLEUM VESUVIUS NASBY 237

inevitable consequence of democracy.

But, unaware of his increasing po-

litical or symbolic importance, Nasby

resumes his lamentation:

O! my country! Where is Tooms, and

Yancy, and Wigfall? The

lofty domes uv the cappytle dont re-ekko

no more 2 their sole-inspirin

voices. Ez I reflek that these pillers

uv Dimocrisy aint here--and,

what is wuss, that they dassent cum

here--that these place that

knode em wunst will kno em no more

furever--my manly buzzum

throbs with sorrer, and my prowd form is

bowed in anguish. O thou

fell sperit uv Abolishnism, thow hast

much 2 anser for--mucher

than thow canst anser. . . . Avant, thow

grim and nasty cuss! My

stumick heeves wheneer I think uv thee.

Nasby's visit with Vallandigham was

reported faithfully and hilariously.

They sat down to a bottle "uv

concentratid contentment" and the conver-

sation commenced:

"Nasby," sez he, "we're

in a fix."

"Vallandygum," sez I, "to

wich do yoo elude--our distractid

country?"

"Nary," sez he; "I wuz a

speekin uv myself and the rest uv us.

Them's my country."

As the conversation continues and the

"concentratid contentment" in

the bottle diminishes, Nasby reveals

Vallandigham as the Republicans

saw him, ignorant, dishonest, selfish,

and traitorous. To Nasby, however,

Vallandigham was a "trooly grate

man," to whom he remained loyal.

But, unfortunately for the cause, Nasby

was unable to be of much service

in the campaign that fall. He had

intended both to campaign strenuously

and to be a candidate for "ary 1 uv

the offices to be fild this ortum," setting

forth his qualifications as:

1st. I want an offis.

2d. I need a offis.

3d. A offis wood suit me; ther4

4th. I shood like to hev a offis.

However, Nasby's attention was

distracted from the political wars to a

threat to his own person: the governor

had instituted a draft to fill the

"volunteer" regiments. With a

sudden lack of political bias, Nasby

commented:

I know not wat uthers may do, but ez for

me, I cant go. Upon a

rigid eggsaminashen uv my fizzlekle man,

I find it wood be wus ner

madnis for me 2 undertake a campane,

to-wit:

1. I'm bald-headid, and hev bin obliged

to ware a wig these 22 years.

2. I hev dandruff in wat scanty hair

still hangs around my vener-

able temples.

238 OHIO HISTORY

3. I hev a kronic katarr.

4. I hev lost, sence Stanton's order to

draft, the use uv wun eye

entirely, and hev kronic inflammashen in

the other.

5. My teeth is all unsound, my palit

aint eggsactly rite, and I hev

hed bronkeetis 31 yeres last Joon. At

present I hev a koff, the paroxisms

uv wich is friteful 2 behold.

6. I'm holler-chestid, am short-winded,

and hev alluz hed panes in

my back and side.

Nasby continues the enumeration of his

ailments, a list that would un-

doubtedly sound familiar to any World

War II draft board examiner,

concluding with a statement that

"the above reesons why I cant go, will,

I maik no doubt, be suffishent."

But, as Nasby learned, they were not;

the examining physician was a Union man,

the commissioner was a "bluddy

Ablishnist," and Nasby's next

letter bears the dateline "Brest, Kanada

West." He had joined the exodus of

"Peece Invalids" who managed to

escape a few jumps ahead of the provost

marshal. Unfortunately for

him, Nasby, as always, was broke.

This ribaldly ridiculous episode was not

funny to Nasby, but it was

typical of the growing body of western

humor, much of it politically

inspired, that had become popular with

the publication of A Narrative

of the Life of David Crockett in 1834 and was to lead directly to Mark

Twain's Roughing It and Innocents

Abroad. Told seriously, with the nar-

rator hiding behind a mask of graveness,

it exploits the techniques of

ludicrousness, grotesqueness, and

ineptness, ostensibly characteristics of

the narrator, but in reality those of

all mankind.

Such a tradition was not merely familiar

to Abraham Lincoln, but he

was part of it, and Lincolniana is full

of verified and apocryphal accounts

of Lincoln's contributions to it. At the

same time during the war that Locke

in the guise of Nasby was dealing

specifically and satirically with the

problems that Lincoln was trying to

resolve in practical fashion, he was

doing so in terms familiar to Lincoln

and that Lincoln himself employed

effectively on a number of occasions.

Locke's ability to combine the tradi-

tion that Lincoln knew so well with the

problems that Lincoln faced

daily made it inevitable that Lincoln

would become a Nasby fan, perhaps

as early as 1862, but certainly by the

fall of 1864.7 Behind Locke's

caricature Lincoln recognized a kinsman.

Nasby's illiterate style, his backwoods

conceit, his naive and seemingly

unconscious caricature of the northern

Copperhead were very much in

the style of the letters Lincoln himself

had written to the Springfield

Sangamo Journal, the so-called "Rebecca letters" of August 27

and 29,

1842. In them Lincoln had used the same

technique to attack Democrat

James Shields, the state auditor of

Illinois. The result of these letters

was Nasby-like in its ludicrousness.

Shields challenged Lincoln to a duel,

Lincoln accepted, naming cavalry

broadswords as the weapons, and the

two parties slipped away to the Missouri

side of the Mississippi to avoid

arrest while they settled their

differences.

|

Lincoln and Shields sat on logs in the misty morning waiting for the duel to begin, and then Lincoln reached up with his sword to cut a twig from a tree far beyond Shields's reach. After this demonstration the duel was settled without loss of honor or blood, but as the skiff returned to Illinois, spectators on the shore saw a man lying down, apparently seri- ously wounded. But the wounded man was a log covered with a red shirt; Lincoln and Shields had a good laugh at the expense of the onlookers; and they parted amiably. It was the sort of situation in which Nasby found himself at the moment as he attempted to subsist in Canada without work- ing, but to him it wasn't funny. Yet, in spite of all probability or logic, Nasby's predicament grew worse. Deciding that because the draft had been suspended, he is safe from induction, he attempts to return to Wingert's Corners, where his wife is employed as a washerwoman. But on the dock at Toledo he is apprehended, and he finds himself an unwilling member of the "778th Ohio Kidnapt Melishy," wearing the "Ablishnist" blue that he despised. "Hentz4th," he commented, "the naim uv Nasby will shine in the list uv marters." He laments that "Looizer Jane" may never see him again; he requests that she "send me half or three-quarters uv the money she gits fer washin, ez whisky costs fritefully here," and he resigns himself to his fate. But Nasby's career in the Union army was short; at the first opportunity he deserted to "my nateral frends, the soljers uv the sunny South." In the "Camp uv the Looisiana Pelicans," Nasby bumbles his innocent way through a series of situations that he accepts in puzzled bewilderment as he attempts to interpret a harsh and unpleasant reality in terms of his stereotype of southern righteousness. The first of these incidents |

240 OHIO HISTORY

was that of the disposition of his

clothes, just after he had been made

welcome by his "nateral

frends." Nasby's new uniform of Union blue

is confiscated, only to reappear on the

backs of the company officers, while

he is clothed in the rags of a private

Confederate soldier. This change

Nasby can tolerate, although he finds it

a questionable practice; but soon

he voices his disillusionment:

I am here, and mizrable!

I am not less that 213 per cent. more

mizrable nor I used to be! ...

Knowin that I cood at eny time desert to

my Suthern frends, I

felt satisfied at bein draftid. Sence my

enrollment in the ranks uv

the Pelicans, the romance uv the thing

hez departid. Nothin 2 eat,

nothin to wear, no money, and hard work.

This is our fix. The plump,

rosy Nasby is no more -- anserin 2 his

name is a lean indiviggooal,

upon whose nose a bullet cood be split.

In spite of his protests that

"sustaned and soothed by an unfaltrin

trust in the rychusnis of the Suthrin

coz," he stuck to his "beluvd rejyment,

the Loozeaner Pelikins, with a tenassity

wich I did not dreme I possest,"

Nasby's military career ended quickly.

In his first skirmish he deserted

once more and made his way home to

Wingert's Corners. Still convinced of

the righteousness of the southern cause,

he had determined that he could

best serve it at home by aiding

deserters and draft rioters rather than

by force of arms. In the course of these

activities, however, he is arrested

in spite of his protests that he

"wuz a Methodist preacher sellin fruit-trees."

But his real indignation is directed at

his release because he "wuz 2 smal

pertaters to notis." A free man, he

returns once more to Wingert's Corners,

resolved to carry on the cause.

This return to the political war in the

heart of the Democratic country

in Ohio provided Locke with the

opportunity for his most biting satire,

a satire that was not directed at the

Confederacy or its cause as it had

been thus far but at the forces of the

Peace Democrats, led in Ohio by

Clement L. Vallandigham. Under his

leadership both as a member of

congress until his defeat in 1862 and as

a Democratic candidate for

governor in 1863, the Democratic party

in Ohio was becoming what the

administration considered a serious

threat to the federal war effort.

But Vallandigham as congressman and as

candidate for governor was

presumably untouchable in spite of the

fact that he was under constant

surveillance, primarily because the

administration did not want to pre-

cipitate a political crisis. On May 1,

1863, however, the issue was forced

when, at a speech at Mount Vernon, Ohio,

Vallandigham declared that

the war was not being fought to preserve

the Union but to free the

slaves and enslave the whites. General

Ambrose E. Burnside, commanding

the Department of the Ohio, promptly had

Vallandigham arrested under

General Orders No. 38, which stated that

"the habit of declaring sym-

pathies for the enemy will not be

allowed in this department." He was

PETROLEUM VESUVIUS NASBY 241

confined, tried by a military court, and

sentenced to confinement for the

duration of the war.

At this point, President Lincoln

intervened and commuted Vallandig-

ham's punishment to exile to the

Confederacy. Turned over to bewildered

Southern pickets under a flag of truce,

Vallandigham proceeded to repeat

Nasby's experience in spirit if not in

fact. Making his way to Canada,

he resumed direction of the Ohio Democratic

party and was nominated

for governor. Unable to return to Ohio,

he campaigned by long distance,

only to be defeated by John Brough in

the fall elections.

On his return to Wingert's Corners after

his recognition that discretion

is the better part of valor, Nasby

proceeded to organize "the First

Dimekratik Church uv Ohio," the

order of exercises of which included

the singing of " 'O, we'll hang Abe

Linkin on a sour apple tree,' or some

other improvin ode, hevin a good

moral." The church, less formally and

more popularly known as "The Church

of St. Vallandigum," was im-

mediately successful, so much so that

Nasby commented:

I bleeve good will be accomplisht. Last

week, in makin a pastoral

visit, jest about noon, to the house uv

wun uv my flock, who hez

fine poultry, I wuz amoosed at hearin a

meer infant, only three years

uv old, swinging his little hat, and

cry, "Horraw for Jeff Davis."

It was tetchin. Pattin the little

patriot on the head, I instantly borrowd

five cents uv his father to present to

him.

In the church the mobbing of recruiting

and draft officers became a

major work of mercy, while the Reverend

Nasby continued the tirade

against a "tyrannikle"

president and government, both of which denied

recognition of Nasby's own personal

talents, the rights of "free men,"

and the democratic heritage that

incorporates in it the right to keep

the Negro in his proper place, a place

more wretched than Nasby's own.

In sentiments reminiscent of both the

Know-Nothings of the 1850's and

the tirade of Huckleberry Finn's father

against the Negroes, Locke

occasionally slips from satire into

viciousness as he records Nasby's

words, but such lapses are only

momentary, as Nasby's bumbling ridic-

ulousness reasserts itself. The letter

of despair written after Vallandig-

ham's defeat by Brough is Nasby at his

pathetic best, frustrated on every

side:

Despondent and weery uv life, I

attempted sooiside. I mixt my

licker fer a day; I red a entire number

uv the Crisis; I peroozed

"Cotton is King," "Pulpit

Pollytiks," and "Vallandigum's Record," but

all in vane. Ez a last desprit resource,

I attemptid to pizon myself by

drinkin water, but that faled me. My

stumick rejected it -- I puked.

From this low point, however, the

irrepressible Nasby soon rebounded.

Temporarily becoming a "War

Democrat," he proclaims that Vallandigham

242 OHIO HISTORY

is a traitor and that "the war for

the Union must go on until its enemies

is subjoogated." In order to carry

on the Democratic cause in the face

of the repudiation of the peace program

in 1863, he journeys once more

to Washington to engage "Linkin . .

. a goriller, a feendish ape, a thirster

after blud," in political debate.

Lincoln listens, dryly agreeing that he,

too, would have abandoned Vallandigham

after the election, as Nasby

delivers what he maintains is his final

political plea:

"I wood accept a small post-orifis,

if sitooatid within ezy range uv

a distilry. My politikle daze is

well-nigh over. Let me but see the old

party wunst moar in the assendency; let

these old eyes once moar

behold the Constooshn ez it is, the

Union ez it wuz, and the nigger

ware he ought 2 be. . . . Linkin, scorn

not my wurds. I hev sed. Adoo."

But this was not to be Nasby's departure

from politics. As the threat

of the Peace Democrats temporarily

subsided after their defeat in the

elections of 1863, Locke had shifted his

target to the widening split in

Democratic philosophy as well as the

party itself and had begun to prepare

for the campaign of 1864. In that

campaign, General George B. McClellan,

a War Democrat, was to win the

nomination although the party was to

advance a peace platform based on the

increasingly frequently heard

principle, voiced by Nasby and the draft

rioters, of "The Constitution as

it is and the Union as it was." In

effect this split indicated a Democratic

stagnation which, if it were successful,

would restore the philosophical

and political stalemate that had made

the war inevitable. Nasby, still

strongly anti-abolitionist and

anti-Republican, demonstrates the uncer-

tainty of his party and himself in the

exhortation issued from his pulpit

on November 9, 1863:8

We lost control, my brethren, by bein

stubborn. O! let us dodge

that fatal errer. The last elecshen

shode that we cood not lede the

people -- let the people lede us. Ef the

people want war, let us be

war men; ef they want peece, let us sing

hosanners to peece! Ef

they want war in Ohio, let Ohio

Dimekrats be war men, and ef Noo

York wants peece, let em be peece men.

Our platform is broad enuff

to accommodait all.

At the same time, Nasby bemoans the fate

of a party badly led and

almost hopelessly split. Even a seance

in which Nasby seeks guidance

through "speritooalism" gives

him no hope. The spirits of the great

Democratic leaders, "Tomus

Jefferson," and "Androo Jaxn," and Senators

Benton and "Duglis,"

disappoint him as they are proven in his mind to

be imposters and spiritualism is

revealed as a fraud; each of the party's

saints had, in turn, denounced both the

Democratic party and its wartime

principles.

PETROLEUM VESUVIUS NASBY 243

Although an anti-McCellan man in

principle, Nasby determines to sup-

port him, both because it appears that

he will get the nomination and

because "expeejensy, which is the

classikle fraze for bred and butter,"

demands it. At this point, however,

Nasby, the master politician, proposes

a pair of candidates and a platform that

will unite all factions and parties,

win the election, and end the war. It is

"FREMONT and VALLANDI-

GUM!" The platform is logical:

We kin do it and be consistent.

Compermise hez alluz bin a bam for

Dimekratik wounds, and we must

compermise -- each faction sofnin

down a little. The Ablishnists must give

up ther Ablishnism, the

pro-slavery men ther pro-slaveryism, the

war men must give up ther

war, and the peece men ther peece, and

all yoonite on the brod and

comperhensive platform uv opposishen 2

Linkin. . . . I went out into

the woods, last Sunday, to see wether I

cood holler "Hooror for

Fremont!" The fust 15 or 20 times

it stuck in my throte, but after

a hour or 2, it workt smooth. Dimokrasy

is flexyble.

Nasby's proposal to reunite the nation

was ridiculous, so much so that,

as Locke intended, it pointed out the

state of the northern Democracy as

it fumbled for an elusive common goal

and identity in the months before

the election of 1864. Democracy was

indeed flexible, as Nasby commented,

so flexible that it was unable to assume

a logical form. The controversy

that Locke derides had the same

indecisive basis as that which, in the

1830's and 1840's, had split the party

of Jackson into Locofocos, Barn-

burners, and regulars as it saw much of

its vitality seep into the Liberty

party, the Free-Soil party, and later

the Republicans. It was similar to

the controversy that had split and

destroyed Locke's own Whigs a decade

before. Only the Republican party, a

sectional group of many minds

united by the intensity of its dislike

for slavery, was to avoid such a split

during the years of antislavery

agitation and war because it accepted,

however its members may have varied in

degree, a common cause against

slavery as its basis.

But neither Locke nor Nasby was

concerned with the implications of

the controversies that destroyed and revamped political

philosophies; they

were concerned with the pragmatic

policies of the moment. Consequently

the letters exploit the Democratic breach

as they turn to the program

advanced by a number of northern Peace

Democrats who supported the

slogan that demanded a return to

"The Constitution as it is and the

Union as it was." To Nasby the

problem is simple; the South has lost

the war, but it can still win the peace.

To Jefferson Davis, the logical

defender of a slogan that attempts to

return to the past, he writes:

You've found the eagle stile uv doin

things a hard rode to travil;

spozn yoo try the snaik? Gefferson,

surrender. Ask uv the Northrin

|

Staits that they each appint a commissioner to arrange the terms uv yoor kumin back. Name yoor men, and be shoor that Fernandywood uv Noo York, and sammy Cox uv Ohio, and the ever-blessid Brite uv Ingeany, is uv them. Ef the goriller Linkin refoozes, wat then? Methinks we hev him. Let him refooze enny offer uv peese, and enuff week-need Ablishnists will jine the ranks uv the Dimokrasy, (wich is now, alluz hez bin, and ever will be yoors 2 kommand,) to enable us to carry the next eleckshun. Then, O, then, Gefferson, woodent the old times kum agin? Woodent they? In spite of Nasby's suspicious fear of McClellan, like a good party man he fell in line after his nomination; after all, there was much to be said for him: "Suffice it 2 say, that no general wuz ever so beluvd South, and so hated North, wich wuz wot prokoord his nominashen." Confident of victory, Nasby takes up a collection, securing eight dollars to defray campaign expenses. Hence, he writes, "I shel probably appere on the stump in a new pair uv pants." As a party regular he points out desperately that there is room on the platform for all varieties of Democrats, that McClellan is both a man of peace and a man of war, but finally he realizes that the issue is in doubt because what ought to please everybody, "sumhow" did not. As the pos- sibility of defeat overwhelms him, for the first time the irrepressible Nasby despairs: "Troo, all is lost! The Suthren coz is lost, the post-orfises is lost, the doggerys is lost!" Earlier Nasby's doubts about the outcome of the election had been shared by Abraham Lincoln. Convinced that the sentiment for peace grew stronger as the casualty lists mounted from Grant's hammering campaign and that he would not be reelected, Lincoln made plans to save |

PETROLEUM VESUVIUS NASBY 245

the Union in spite of itself as he

prepared to turn over the government to

his successor. But when the early fall

predictions came in it was evident

to Nasby that McClellan would lose:

"Ohio! Pensilwany! Injeany!" he

laments. "Pennsilwany is cussid,

Ohio is cusseder, but Injeany is cussidist."

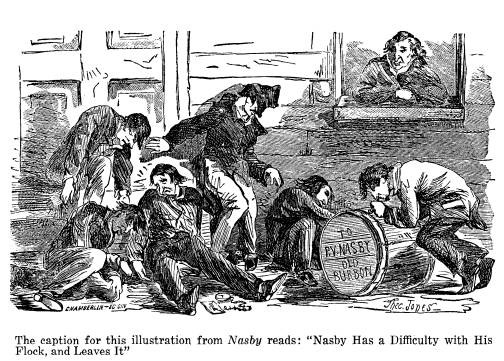

From the election of 1864 to the end of

the war the odyssey of Petroleum

Vesuvius Nasby is anticlimax, just as

those final months were for the

Confederacy. As the returns come in,

Nasby's parishioners who had given

him money for offices in the McClellan

administration accuse him of

fraud and demand their money back. Only

ingenuity saves him from the

tar and feather fate reserved for the

confidence man:

My privit barel uv whisky wuz in my

study -- I wuz saved! I

histid it out uv a winder, and calmly

awaited results. They flockt

around it -- they took turns at the

bung-hole. In wun short hour they

wuz stretched helpless on the plane, ded

drunk. Then and there I

resined my charge, and borrerin sich

munny and watches ez the

ungrateful wretches hed about em, to

make up arrears uv salary and

sich, bid adoo 2 em furever. I shell go

2 Noo Gersey.

The election was closer than the

electoral vote for Lincoln indicates.

It was not like the total rout suffered

by Nasby, but in New Jersey,

the only northern state that had given

McClellan a majority, Nasby

sought his elusive peace at

"Saint's Rest," a haven for party stalwarts.

Here, of course, he could find no peace,

just as he could find no hope for

the future in a nation dominated by

abolitionism; finally, as the war comes

to its end, he can only leave the

testimony of his devotion and faithfulness

to a party in defeat:

I hev no apologies to offer. . . . I may

not hev sed enuff agin the

nigger -- I may not hev suffishently

aboozed Noo England -- I may

hev bin too easy on Linkin, and I may

hev sed too much for Micklellan.

But, ef this be so, these errors must be

inskribed to my head, and

not to my heart. That I am sound to the

core in my Dimokrasy, let

my noze, and the fact that I never

skratched a tikit, attest.

In concloosion.

To the leaders I recommend akootnis,

energy, and perseverance.

To the voters, steddinis, submission,

and unquestionin fidelity.

To orfis-holders in our Staits,

liberality, and ez much honesty ez

is consistent with their own interests

and the interests uv the party.

To our friends, my love!

To our enemies, my burnin cuss!

Adoo! Farewell!

But Nasby was not allowed to disappear

so easily. In spite of the

bitterness and viciousness that the war

and political strife engendered,

Nasby himself, in the person of David

Ross Locke, became a favorite on

the lecture platform during the postwar

years. Although Locke turned his

satirical attention to other aspects of

politics and society, focusing specifi-

246 OHIO HISTORY

cally on the greed of speculators and

exploiters, Locke's identity became

so fused with his creation that Nasby he

remained to his death in 1888.

During his career as Nasby, Americans

learned from him and his friend

Mark Twain that they could laugh at

themselves as well as at each

other and that they might grow in

understanding as a result.

THE AUTHOR: David D. Anderson is

an associate professor in the department

of American thought and language at

Michigan State University.

|

|

|

THE ODYSSEY OF PETROLEUM VESUVIUS NASBY

by DAVID D. ANDERSON |

|

After more than a century the American Civil War remains garbed in tragedy and pathos, heroes and hero worship, sentiment and cynicism, as it has been since the guns fell silent and the printing presses began to pour out a still unabated torrent of memoirs, histories, and biographies. As an age of heroes, it is resplendent with the names of Lincoln, Grant, Lee, Sherman, Sheridan -- and Petroleum Vesuvius Nasby. Perhaps the least remembered of these is Nasby, although he, like the others, came out of obscurity to fame in the four years of the war. Yet, in spite of the shadow into which he has again passed, Nasby deserves inclusion in any list of the war's great men: he is our only authentic Civil War anti-hero. Nasby began his anti-heroic march, not in the ranks of either army, but in a long series of letters that began to appear with regularity on April 25, 1862, in the Hancock Jeffersonian of Findlay, Ohio.1 His attainment of

NOTES ARE ON PAGE 279 |

(614) 297-2300