Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

10 OHIO HISTORY

TO CINCINNATI*

by EDWARD A. M'LAUGHLIN

Fair is thy seat, in soft recumbent

rest

Beneath the grove-clad hills; whence

morning wings

The gentle breezes of the fragrant

west,

That kiss the surface of a thousand

springs:

Nature, her many-colored mantle

flings

Around thee, and adorns thee as a

bride;

While polished Art his gorgeous

tribute brings,

And dome and spire ascending far and

wide

Their pointed shadows dip in thy

Ohio's tide.

So fair in infancy -- O what shall be

Thy blooming prime, expanding like

the rose

In fragrant beauty; when a century

Hath passed upon thy birth, and time

bestows

The largess of a world that freely

throws

Her various tribute from remotest

shores,

To enrich the Western Rome: Here

shall repose

Science and art; and from time's

subtile ores --

Nature's unfolded page -- knowledge enrich her stores.

So sings the Muse as she with fancy's

eye,

Scans, from imagination's lofty

height,

Thy radiant beaming day -- where it doth lie

In the deep future; glowing on the

night

From whose dark womb, empires unveil

to light;

Mantled, and diademed, and sceptered

there,

Thou waitest but the advent of thy

flight,

When, like a royal Queen, stately and

fair,

The City of the West ascends the

regal chair.

* An excerpt from a poem found in a

collection of poems by Edward A. M'Laughlin

entitled Lovers of the Deep, which

was originally printed at Cincinnati in October 1841.

The 312-page volume was dedicated to

Nicholas Longworth. William T. Coggeshall, The

Poets and Poetry of the West (Columbus, 1860), 247-249.

|

CINCINNATI ATHENS OF THE WEST 1830-1861

by LOUIS LEONARD TUCKER

"All books are divisible into two classes," John Ruskin wrote in Of Kings' Treasuries, "the books of the hour, and the books of all time." Ruskin was well aware that a dichotomy of this type was not absolute, that a few works could easily qualify for admittance into both classes. Frances Trollope's celebrated opus, Domestic Manners of the Americans,1 which was published in 1832, was assuredly one of these. An overnight sensation on two continents at its first printing, it still ranks as one of the classic travel accounts of the nineteenth century. If Domestic Manners brought fame and fortune to its author, it provided few positive benefits to its main subject, the city of Cincinnati, Ohio. It did bring a blazing notoriety to the Ohio city, and Cincinnati still is suffering from the effects of it. While based on only twenty-five months of residence in the Queen City (from February 1828 to March 1830), it fashioned an image of ante-bellum Cincinnati that remained granitically fixed in American historiography for more than half a century -- and it is still embedded there to some degree. The image is that of "Porkopolis," and the mental impres- sions evoked by that colorful appellation are well known to every student of Western American history. "Porkopolis" connoted, first and foremost, hog center of the United States, or, as another British traveler more delicately phrased it, "pork-shop of the Union."2 It conjured up the vision of a city in which fat hogs waddled through the streets at will; of putrefactive streets and market stalls; of massive slaughter houses which emitted an effluvium that was a stench in the nostrils of all, except localites; of streams brimming

NOTES ARE ON PAGES 67-68 |

12 OHIO HISTORY

with inedible slaughter house remains,

their waters brought to a fiery red

hue by frequent infusions of hog blood.

No discussion of Mrs. Trollope's

"Porkopolis" would be complete

without a specimen of the "old woman's"

evocative literary style.

It seems hardly fair to quarrel with a

place because its staple com-

modity is not pretty, but I am sure I

should have liked Cincinnati much

better if the people had not dealt so

very largely in hogs. The immense

quantity of business done in this line

would hardly be believed by those

who had not witnessed it. I never saw a

newspaper without remarking

such advertisements as the following:

"Wanted, immediately, 4,000 fat

hogs."

"For sale, 2,000 barrels of prime

pork."

But the annoyance came nearer than this;

if I determined upon a

walk up Main-street, the chances were

five hundred to one against my

reaching the shady side without brushing

a snout fresh dripping from

the kennel; when we had screwed our

courage to the enterprise of

mounting a certain noble-looking

sugar-loaf hill, that promised pure

air and a fine view, we found the brook

we had to cross, at its foot,

red with the stream from a pig

slaughter-house; while our noses, instead

of meeting "the thyme that loves

the green hill's breast," were greeted

by odours that I will not describe, and

which I heartily hope my readers

cannot imagine; our feet, that on

leaving the city had expected to

press the flowery sod, literally got

entangled in pigs' tails and jawbones:

and thus the prettiest walk in the

neighbourhood was interdicted for

ever.3

The ubiquitous hogs represented for Mrs.

Trollope but one of "Porkopolis's"

many shocking defects. She disliked the

hurly-burly boom town atmosphere,

rampant materialism, licentious

democracy, disrespectful servants, and boorish

frontiersmen and nouveau riche who

were in constant search of "that honey

of Hybla, vulgarly called money,"

who were forever unleashing deadly

quantities of yellow amber from their

tobacco-laden mouths, and whose table

manners would make Tom Jones' culinary

habits appear impeccable by

comparison.

Some of her more devastating salvos were

directed against a Cincinnati

that was beginning to regard itself as

an "Athens of the West." In her view,

Cincinnati was a land of stale

stupidity, populated by vulgar dolts who had

not the vaguest conception of things of

the mind and spirit. In the drawing

rooms, she noted, "The gentlemen

spit, talk of elections and the price of

produce, and spit again."4 By

her standards, the cultural and intellectual

tone of the city was depressingly dull.

In recounting a literary conversation

with "a gentleman said to be a

scholar and a man of reading," she indirectly

wrote off the entire city as a kind of

frontier "Dullsville" in these words:

Our poor Lord Byron, as may be supposed,

was the bull'seye against

which every dart in his black little

quiver was aimed. I had never heard

any serious gentleman talk of Lord Byron

at full length before, and I

listened attentively. It was evident

that the noble passages which are

graven on the hearts of the genuine

lovers of poetry had altogther

escaped the serious gentleman's

attention; and it was equally evident

that he knew by rote all those that they

wish the mighty master had

never written. I told him so, and I

shall not soon forget the look he

gave me.

|

CINCINNATI -- ATHENS OF THE WEST 13 |

|

Of other authors his knowledge was very imperfect, but his criticisms very amusing. Of Pope, he said, "He is so entirely gone by, that in our country it is considered quite fustian to speak of him." But I persevered, and named "the Rape of the Lock" as evincing some little talent, and being in a tone that might still hope for admittance in the drawing-room; but, on the mention of this poem, the serious gentleman became almost as strongly agitated as when he talked of Don Juan; and I was unfeignedly at a loss to comprehend the nature of his feelings, till he muttered, with an indignant shake of the handkerchief, "The very title!" At the name of Dryden he smiled, and the smile spoke as plainly as a smile could speak, "How the old woman twaddles!" "We only know Dryden by quotations, Madam," [he answered], "and these indeed, are found only in books that have long since had their day." "And Shakespeare, sir?" "Shakespeare, Madam, is obscene, and, thank God, WE are sufficiently advanced to have found it out! If we must have the abomination of stage plays, let them at least be marked by the refinement of the age in which we live." This was certainly being au courant du jour. Of Massenger he knew nothing. Of Ford he had never heard. Gray had had his day. Prior he had never read, but understood he was a very childish writer. Chaucer and Spenser he tied in a couple, and dismissed by saying, that he thought it was neither more nor less than affectation to talk of authors who wrote in a tongue no longer intelligible. [Mrs. Trollope concluded with this sharp thrust]: This was the most literary conversation I was ever present at in Cincinnati.5 Domestic Manners fell upon the world of letters with the impact of an H-bomb. It not only obliterated the modest reputation Cincinnati was developing in the early 1830's as a cultural and intellectual center of the West, but it also laid a cloud of radioactive fallout over the city in the form of the "Porkopolis" projection. For the next sixty years, those few researchers who were engaged in an examination of American cultural and intellectual history studiously avoided the southwest Ohio city. |

14 OHIO HISTORY

What is surprising about this vacuum in

scholarship is that knowledgeable

researchers must have realized that Mrs.

Trollope's picture of Cincinnati was

overdrawn to the point of caricature.

Contemporary reviews of her book had

been devastating in their criticism. The

respected Edinburgh Review casti-

gated her as "an irresponsible

caricaturist who drew her sketches not with

pen and India ink but with vitriol and a

blacking brush." It branded her book

as "nothing but four-and-thirty

chapters of American scandal." American

critics by the score meticulously

catalogued Mrs. Trollope's inaccuracies

and her deficiencies as a chronicler of

the young nation's manners and

morals, and cultural and intellectual

traditions. While some Cincinnati

newspapers reprinted long extracts from Domestic

Manners, their editors

regarded the book as "palpably

sinister." They quite properly accused Mrs.

Trollope of exacting literary revenge on

Cincinnati in order to atone for

the deep financial ducking she underwent

there, and more significantly, for

the humiliating social repudiation she

experienced at the hands of the

grandes dames of the Queen City.6 The Countess de Chambrun

once inquired

of some Cincinnati dowagers, who were

social lions during Mrs. Trollope's

period of residence, why the English

woman wrote of the city with such

bitterness. The standard reply was:

"My dear, she never could get in. Her

manners were bad and she had no

refinement. After seeing how she behaved

in market no one could think of asking

her inside a drawing room."7 This

attitude of exclusiveness by the

Cincinnati ladies assuredly outraged the

socially-sensitive Englishwoman. And on

those rare occasions when they

did invite her to a social function, they did not endear

themselves by asking

if she fled England to escape body

lice!

Of all the harsh indictments rendered by

contemporary authorities, the

following is unquestionably the most

telling in the context of the thesis of

this paper:

No observer was certainly ever less

qualified to judge of the prospects

or even of the happiness of a young

people. No one could have been

worse adapted by nature for a task of

learning whether a nation was in

a way to thrive. Whatever she saw she

judged, as most women do, from

her own standing-point. If a thing were

ugly to her eyes, it ought to be

ugly to all eyes, -- and if ugly, it

must be bad.

She was endowed . . . with much creative

power, with considerable

humor and a genuine feeling for romance.

But she was neither clear-

sighted nor accurate; and in her

attempts to describe morals, manners,

and even facts, was unable to avoid the

pitfalls of exaggeration.8

This sharp judgment was rendered shortly

after the publication of Domestic

Manners by Mrs. Trollope's own son, Anthony Trollope.

With the passage of time, the savage

strictures of the critics were for-

gotten, and the sprightly phrased venom

of Mrs. Trollope began to enjoy

a warm flirtation with Truth. It became

the considered judgment of posterity

that, if she were not totally accurate

in her account, Mrs. Trollope had

come close enough to merit recognition

as a discerning analyst of American

mores. She was regarded very much like Huck Finn, of whom it

was said:

"There were things which he

stretched, but mainly he told the truth."

In the genre of travel literature, Domestic

Manners achieved a singular

|

CINCINNATI -- ATHENS OF THE WEST 15 |

|

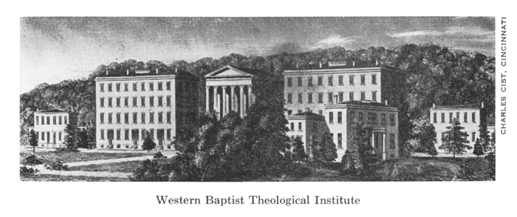

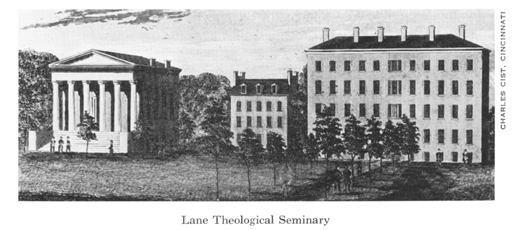

distinction, and in American historiography, pre-Civil War Cincinnati became the "monster piggery." So it remained until 1891, until William Henry Venable published his landmark work, Beginnings of Literary Culture in the Ohio Valley.9 While conceived as a broad study of cultural developments in the entire Ohio Valley, with a special emphasis on literary attainments, Venable's work devoted more space to the cultural and intellectual affairs of Cincinnati than to those of any other Ohio Valley city. This overbalanced emphasis underscored a point that Venable did not explicitly state or develop: that Cincinnati was the cultural center of the Ohio Valley. If the book were narrow in scope and skeletal in its treatment of Cincinnati, it did cast a powerful beam of scholarship upon a heretofore blackened area of Western cultural history. Since the appearance of Venable's book, a handful of researchers have poked about the rubble of "Porkopolis," and while their studies also are lacking in depth and comprehensiveness, they have resulted in the partial rehabilitation of Cincinnati's reputation as an early center of culture. Cincinnati is con- spicuously featured in the far-ranging studies of Ralph Rusk, James Miller, R. Carlyle Buley, Louis B. Wright, and Richard C. Wade.10 Walter Sutton's recent study of the Western Book Trade11 is a more noteworthy addition to the growing bibliography on Western urban history, since it is a concentrated examination of nineteenth-century Cincinnati as a publishing center. Its find- ings alone will profoundly affect any future interpretation of the cultural life of pre-Civil War Cincinnati. In recent years, a rash of articles has appeared in the quarterly journals of The Cincinnati Historical Society and The Ohio Historical Society, which treat in depth special facets of the cultural and intellectual life of pre-Civil War Cincinnati. If there is as yet no definite volume encompassing all aspects of this extensive area of inquiry and carrying the story up to the Civil War, there is already sufficient published evidence to confirm the thesis that Cincinnati, during at least the three- decade period preceding the Civil War, had the most vibrant, the most sophisticated, and the most variegated cultural and intellectual life of any urban center west of the Allegheny Mountains. While it may not have attained the exalted status of a London or even of a Boston, the Ohio city could rightfully lay claim to the title of "Athens of the West." |

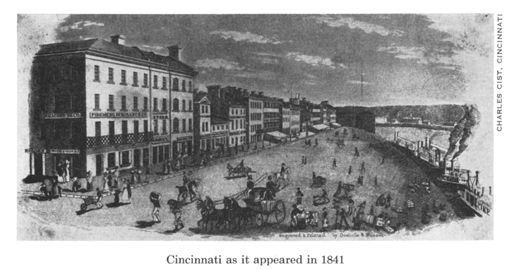

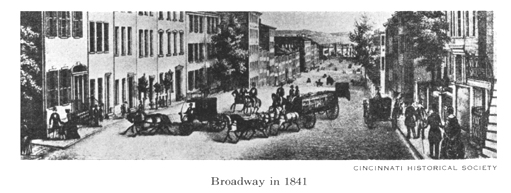

16 OHIO HISTORY

It is a well-known fact that virtually

every Western city of any size and

cultural pretension, from Pittsburgh to

Marietta to Chillicothe to St. Louis,

boasted of being the "Athens of the

West." Even Athens, Ohio, claimed the

distinction. Recognition as a cultural

capital was esteemed in the nineteenth

century as one of the most signal honors

that could come to a city. From

the late eighteenth century until the

steamboat age became firmly established,

roughly about 1830, Lexington, Kentucky,

was the acknowledged cultural

Gulliver of the West.12 Transylvania

University, that remarkable frontier

institution, provided the generating

force for the flowering of Lexington. The

unfortunate destruction of the college

by fire in May 1829 all but terminated

Lexington's tenure of cultural

supremacy. As the inland Kentucky city fell

by the wayside, Cincinnati assumed the

mantle of leadership and retained

it for the next three decades. Even a

Cleveland newspaper was forced to

concede in 1837 that Cincinnati was

becoming "the American Athens for

the West!"13 Excluding New Orleans,

which was more Southern than Western,

Cincinnati's main trans-Allegheny

competitors were Pittsburgh, Louisville,

and St. Louis. Population figures

assuredly do not constitute an absolute

index for ascertaining the quality of a

given city's cultural and intellectual

life, but the following comparative

statistics for 1850 do bear a salient

significance in the context of Western

urban maturity: Louisville, 43,194;

Pittsburgh, 46,601; St. Louis, 77,860;

Cincinnati, 115,436.14 Why no mention

of Chicago? Chicago, at this time, had

only 29,963!

Cincinnati's rise to cultural and

intellectual prominence was closely linked

to its phenomenal economic and

commercial expansion during the Steam-

boat Age. By 1825 Cincinnati was the

steamboat capital of the Ohio Valley,

and by mid-century it was the economic

colossus of the entire West. Wide-

eyed tourists frequently referred to it

as the "Corinth of the West," the

"Tyre of the West," the

"Wonder City of the West," and, of course, the

"Queen of the West."

The designations were apt. This was not

Chamber of Commerce rhetoric.

Cincinnati by mid-century possessed an

impressive economic portfolio; it

was the largest inland port in the

nation; the supreme pork producer in the

world; the leading beer and liquor

producer in the nation; the prime soap,

candle, furniture, shoe, stove and boat

manufacturer in the West, and the

principal printing center of the West.15

Its economy was "enormous, diversi-

fied and amazing." Cairo kept

itself clean with Cincinnati soap. Hannibal

lived in Cincinnati pre-fabricated

houses. Memphis read Cincinnati news-

papers. Vicksburg drank Cincinnati

whiskey. New Orleans ate Cincinnati

ham. Everybody in the West studied

Cincinnati McGuffey Readers. Here

was the quintessence of

"Boomtown." A visitor from Boston wrote to his

sister in 1848:

I have seen so much and heard more noise

than for many years before

.... This city you must know is one of the

towns that you read of -- a

description of it cannot be given while

rattling omnibuses and carts

drown the senses. It is one great

bee-hive -- exhibiting more activity

than New York.16

|

CINCINNATI -- ATHENS OF THE WEST 17 |

|

|

|

Accounts like this are legion for the 1850's in particular, when Cincinnati ranked as the fifth most populous city in the nation and the economic "Empress of the West." In 1859 Charles Cist stated with only slight exaggera- tion that "with the exception of Philadelphia, Cincinnati is probably the most extensive manufacturing city in the United States."17 The economic boom of the "Herculean City," as John Quincy Adams described it in 1844,18 laid the basis for the cultural explosion that took place in the 1830-1860 period. Pork production paved the way for Shakespeare. After a long discourse of exaltation on the material and cultural progress of Cincinnati, a French visitor in 1851 properly concluded: "It is the hogs which have made all this possible!"19 And, as was common throughout the growing cities of the young nation, the leading devotees of culture were also the principal captains of industry and commerce. But contrary to the vitriolic shafts of Mrs. Trollope, the culture-vultures of Cincinnati were men of some educational substance and social refinement. Mrs. Trollope failed to make a distinction between the itinerant hog-drovers and the "First Gentlemen" of the city. On cold winter evenings, the same men who were amassing Olympian fortunes in vile-smelling slaughter houses and hot, grimy foundries con- vened in sumptuously furnished town houses and, applying the scheme of Linnaeus, classified fossilized botanical specimens taken from the banks of the Ohio River; or sat primly in the drawing room of Samuel Foote's majestic mansion on Third Street by Vine, sipping Madeira wine, eating sponge cake and listening to William Greene, of the illustrious Rhode Island Greenes, read literary selections submitted anonymously by Lyman Beecher's mousey |

|

18 OHIO HISTORY |

|

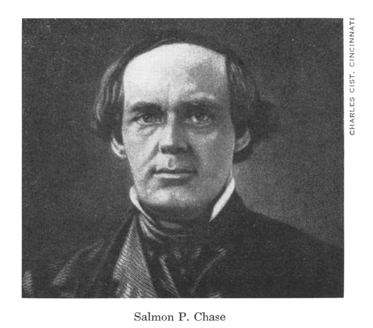

little daughter Harriet or Daniel Drake; or sat enraptured in John Bates's National Theatre as the renowned Shakespearian actor, James E. Murdoch, delivered the "To be or not to be" soliloquy from "Hamlet"; or wandered down to Joseph Dorfeuille's Western Museum to inspect Egyptian antiquities; or spent an hour in the National Art Union, one of the largest art galleries in the city, gazing upon the latest acquisition of statuary formed by Hiram Powers, an ex-Cincinnatian, now a world celebrity in Florence, Italy. A striking percentage of these economic elite were also men of cultural and intellectual proclivities. There was an appreciable number of literate and refined Southern and "middle state" representatives among the economic and cultural leaders of the Queen City, but the greatest number were New Englanders by birth and breeding. As one scans the list of subscribers to, and members of, the formal agencies of cultural life -- libraries, lyceums, museums, debating societies, the historical society and the like -- he repeatedly encounters the names of transplanted New Englanders: men like Salmon P. Chase, Alphonso Taft, Calvin Stowe, William Greene, Samuel and John Foote, Nathan Guilford, William D. Gallagher, Timothy Walker, James Perkins, Nathaniel Wright, and Bellamy Storer. These men hardly can be equated with the stereotyped Cincinnatian of Domestic Manners -- the hard-drinking, loose-talking, tobac- co-spitting boor. When the vanguard of the Lyman Beecher family came to Cincinnati in 1831 to inspect Lane Theological Seminary and the city in general, they were profoundly impressed by the social and cultural climate of the Queen City. Wrote Catherine to sister Harriet, who had stayed behind: I have become somewhat acquainted with those ladies we shall have the most to do with, and find them intelligent, New England sort of folks. Indeed, this is a New England city in all its habits, and its inhabitants are more than half from New England.... I know of no place in the world where there is so fair a prospect of finding every thing that makes social and domestic life pleasant.20 A transplanted Vermonter, who was a Harvard graduate, took up residence in Cincinnati in 1831 and informed a friend: "The society in this city is as polished as the highest circles of Boston. Indeed it is made up of emigrants |

|

CINCINNATI -- ATHENS OF THE WEST 19 |

|

|

|

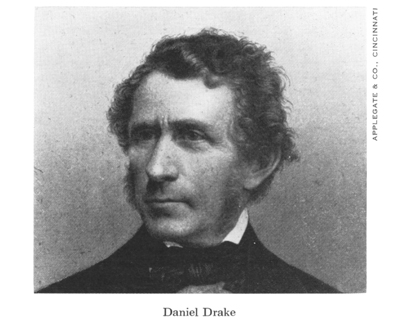

from the Eastern cities almost exclusively. I mean the first society."21 The abundance of New Englanders led to the formation of a New England Society in Cincinnati in 1845, and the membership of this group constituted an intellectual elite, or "braintrust," that few other Western cities could match.22 These New Englanders infused the Queen City with their distinctive Puritan-developed cultural and intellectual values, and they made the "life of the mind" as much a trait of urban existence in Cincinnati as the production of pork and beer or the search for the "honey of Hybla." While New Englanders were the most numerous figures on the cultural landscape, a Kentuckian and a New Jersey immigrant stood out in Olympian majesty. Daniel Drake and Nicholas Longworth were the prime architects of the "Athens of the West." Drake and Longworth were as dissimilar in physical appearance as they were in temperament, yet both shared a deep conviction that their adopted city was destined to become the seat of civiliza- tion in inner America. Animated by this belief, the volatile Drake and the mild-mannered Longworth lavished time and financial resources upon every cultural and intellectual activity initiated in the Queen City. Drake's massive achievements as a culture-builder and civic booster have been amply documented in a number of studies, most recently in Emmet Horine's sympathetic but carefully researched biography.23 A man of incre- dible versatility and prodigious energy, Drake was an harmonious human multitude, like Jefferson, a "host within himself." He made it his life's mission to transform a crude frontier community into the cultural capital of a new Western American civilization. Philadelphia, where he had studied medicine, became the basic model for his vision. The dynamic Drake was a one-man cultural task force during his long, contentious career in Cincinnati. Edward |

20 OHIO HISTORY

Mansfield, a contemporary, described him

as "the founder of some, and

the friend of all good

institutions."24 Practically every cultural and intellectual

agency of this period owed its existence

to this singular medical figure and

cultural leader, who represented the

quintessence of enlightenment and

liberalism. Venable wrote of him:

"So many good works did he undertake,

so much did he accomplish, so effectually

did he stimulate exertion in others,

both friends and enemies, that I think

he may be called with propriety the

Franklin of Cincinnati."25

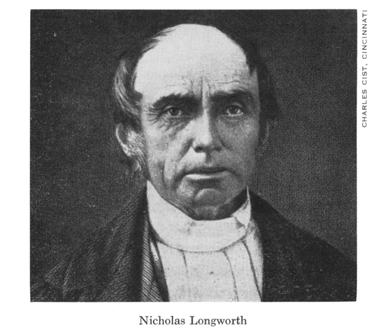

Longworth is more widely known as a real

estate entrepreneur, horticul-

turist, and wine producer than as a patron

of the arts.26 Yet, he, too, was

a prime builder of the "Athens of

the West," and there is a substantial

body of evidence in The Cincinnati

Historical Society to support this state-

ment. The extensive Hiram Powers

Collection, for example, reveals that

Longworth surreptitiously functioned as

a kind of "National Humanities

Foundation" for impoverished and

talented young literati, artists, and

sculptors.27 He subsidized them and

their families, encouraged them to pursue

their cultural endeavors, commissioned

works from them, induced other

wealthy Cincinnatians to buy their

productions, and, in other countless ways,

kept the lamp of fine arts brightly

burning in the Queen City. Had it not

been for Longworth, Hiram Powers never

would have experienced his

spectacular and lucrative sculpturing

career in Florence.

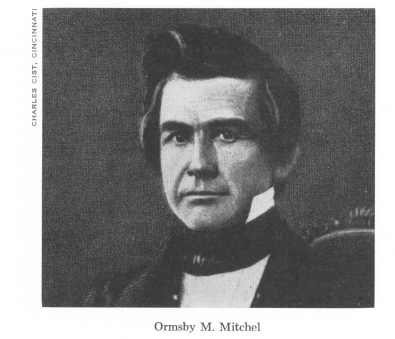

When Ormsby M. Mitchel sought to

establish an observatory in the early

1840's and thereby make Cincinnati the

astronomical center of the nation,

a plan which most thinking Cincinnatians

regarded as an act of lunacy,

Longworth promptly donated four choice

acres of land on the brim of Mt. Ida,

later to be named Mt. Adams. He also

made sizable contributions to the

building fund for the observatory and

his name stood high on the list of

subscribers for the purchase of the

"great" telescope, which was manufactured

in Munich, Germany, at a cost of

$10,000. The "Croesus of Cincinnati" --

this is what the Pulszkys called this

diffident, strange-looking little man who

came to Cincinnati at the turn of the

century with $3 in his pocket and who

soon became one of the wealthiest men in

the nation. His fierce determination

to become a financial success was

complemented by an equally passionate

desire to elevate the aesthetic tone of

the raw Western community which he

had come to love.28

As for the scope of cultural and

intellectual life in pre-Civil War Cincinnati,

by quantitative standards, it was indeed

impressive. There was a kaleidoscopic

variety of cultural and intellectual

agencies: debating clubs, literary clubs,

elocution societies, lyceums, an

historical society, subscription libraries,

singing societies, an observatory and

astronomical society, a Society for the

Promotion of Useful Knowledge, theatres,

opera houses, art clubs -- and so

on almost ad infinitum. These

agencies offered a great deal of room in which

active minds could range. An extract

from the Reverend Moncure Conway's

Autobiography provides a partial insight into the quality, as well as

range,

of cultural and intellectual life in the

1850's. It need be noted that Conway,

a Unitarian, was no provincial rustic.

Nor was he a Chamber-of-Commerce-

|

CINCINNATI -- ATHENS OF THE WEST 21 |

|

|

|

type booster. He was well-traveled, highly refined, and he maintained strong intellectual ties with the Concord, Massachusetts Transcendentalists. Be- cause of Conway's broad frame of geographical reference and cultural background, his judgments bear a special significance. He wrote: Cincinnati was the most cultivated of the Western cities. A third of the population being German, there were societies devoted to music, and in that art the city was ahead of all others in America except Boston. There was a fine orchestra which gave symphony concerts, and a "St. Cecelia-Verein" which sang classical pieces rarely heard elsewhere. There was an admirable literary club, which met every week to converse and regale itself with squibs, recitations, cigars, and Catawba wine. To it belonged young men who afterwards became eminent figures in the world: Rutherford Hayes, President of the United States; [Edward F.] Noyes, a distinguished general and Minister to France; A. R. Spofford, librarian of Congress; Judge Stallo, Minister to Italy, Judge James, Judge Manning Force, and others. There was a good city library, with a Lyceum that had courses of lectures during the winter and enabled us to listen to the most famous public teachers. Emerson, Holmes, Agassiz, H[enry] W. Beecher, [and] Wendell Phillips had not yet been superseded in western halls by vaudeville shows. There was a grand-opera house, and we had annually several weeks of opera or oper- atic concerts. I remember Patti singing there in a troupe when she was a small girl. There were two good theatres, the National and Wood's .... There were fair stock companies at both theatres, and they played good English comedies and melodrama.29 In a later passage, Conway added: "Our city was popularly styled 'the Queen of the West,' but a Paul might have named it the Athens of the West, for every 'new thing' found headquarters there."30 If on occasion the dignity |

|

22 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

of a lyceum discussion were shattered by an overly passionate discussant addressing the chairman as "a jackass," or if a theatre performance were marred by a riot in which men slashed away with bowie-knives, the general character of intellectual doings was surprisingly sophisticated and exhibited a maturity which is nowhere to be seen in the "Porkopolis" of Mrs. Trollope's Domestic Manners. Space restrictions prevent a recitation and appraisal of the cultural achievements of individual personalities. Consider, for example, the possi- bilities for analysis offered by the names of such literati as: Drake, Harriet and Lyman Beecher, Calvin Stowe, Timothy Flint, James Hall; of such a musical genius as Stephen Collins Foster; of such educational figures as the McGuffey brothers, Joseph Ray and Catherine Beecher; of such scientific- minded men as Ormsby Mitchel, John Locke, and Daniel Drake; of such artists as Hiram Powers, Aaron Corwine, Thomas Buchanan Read, Miner K. Kellogg, and Robert S. Duncanson. Since printing has always been regarded as a significant adjunct of culture, the scope of this activity in pre-Civil War Cincinnati should be noted. Walter Sutton's work, The Western Book Trade, clearly establishes the fact that Cincinnati was the publishing capital of the West in the 1830-1861 period. An authority on Cincinnati imprints has written: "After 1821 no one knows just how many different books and pamphlets were published in Cincinnati. They were on almost any subject one can think of, from backroom humor to advanced philosophical speculation. It is difficult to say how many were written by local authors, but certainly the majority were."31 Charles Cist reported in 1841 that one to two million books were printed annually in |

|

CINCINNATI -- ATHENS OF THE WEST 23 |

|

|

|

Cincinnati.32 According to Professor Sutton, by 1850 only three other Amer- ican cities, New York, Philadelphia, and Boston, outranked the Queen City in the production of books.33 A large portion of this output was school textbooks, the most noted being the "Eclectic Series." McGuffey Readers by the millions were printed in Cincinnati and distributed throughout the West, and who can calculate the extent of influence of this work in the shaping of American civilization? By 1859 the W. B. Smith and Company, producers of the "Eclectic Series," ranked as the leading schoolbook publisher in the nation. Its slogan was "School Books for the Million." Over two million copies roared off its presses annually, and more than 500,000 students in the West were regular users of the "Eclectic Series." With pardonable pride, civic-booster Charles Cist wrote in 1859 that "the moral and educational influences of this establishment are of vast public importance, and radiate from Cincinnati, as a centre, all over the Union. Wherever children congregate, in their far-away schoolrooms, or by the happy firesides of home, sit down to learn their lessons out of Eclectic School Books, there this influence is active, and none may measure the untold good it is accomplishing."34 |

24 OHIO HISTORY

Literary works of diverse types were

also published in tremendous volume;

because of this, Cincinnati earned yet

another sobriquet suggesting regional

cultural dominance -- "Literary

Emporium of the West."35

A careful evaluation of the travel

accounts of perceptive visitors to Cin-

cinnati, both foreign and domestic,

produces the conclusion that the Queen

City was something more than a "Hog

Butcher For the West."36 Charles

Dickens, Captain Frederick Maryatt,

Basil Hall, Frederika Bremer, Harriet

Martineau, Francis and Theresa Pulszky

-- the accounts of these and other

discriminating Europeans give the lie to

Madame Trollope's description of

Cincinnati as a city "in want of

refinement." "For more reasons than one,"

Harriet Martineau wrote in 1838, "I

should prefer Cincinnati as a residence

to any other large city of the United

States."37 At least three other British

travelers of this era were frank to

confess that, if circumstance dictated their

immigration to America -- "which

God forbid," hastily amended one, -- they

would select Cincinnati as their place

of residence. After touring the United

States in 1859, a Russian industrialist

published a travel account in Moscow,

which was later serialized in the

journal Russian Messenger. He also found

Cincinnati to be the best in the West:

Cincinnati is not only the center of

western manufacturing -- it is

also head of its intellectual

development. There are three medical

colleges and a university there, not

counting other scholarly and peda-

gogical institutions. A public

observatory has been built on one of

the hills adjacent to the city by the

astronomer Mitchel and capital

contributed by wealthy citizens. . . .

Frequently a thousand people of

both sexes fill the lecture halls of

Cincinnati. Learned men who travel

from place to place give public lectures

here. . . . Farmers will come from

afar to hear competent explanations of

the wonders of nature. Such a

general participation in scientific

education is not to be found in the

mass of the European population, whose

lower ranks are ill-prepared for

such lectures. Cincinnati, moreover,

influences the West through its

papers, journals and various

periodicals. Here there are published thirty-

five English language newspapers and

around twelve in German.38

Domestic travelers were equally as

liberal in lavishing kind words upon

the Queen City during its "Golden

Age." Charles Fenno Hoffman, the cul-

tivated New York literary artist,

visited Cincinnati in 1835 and spoke

glowingly of its cultural and material character. He

attributed its sophisti-

cation to the large contingent of

refined Easterners who had settled there.

Wrote Hoffman:

The New-Yorker, for instance, plumes

himself upon placing a bottle

of Lynch's best before you; the

Philadelphian on having a maitre de

cuisine who adds to his abstruser

knowledge of the sacred mysteries the

cunning art of putting butter into as

tempting rolls as ever sported

their golden curl upon a Chestnut-street

breakfast table; the centre

table of the Bostonian is covered with

new publications fresh from the

American Athens; and you may be sure to

find the last new song of

Bayley on the music-stand of the fair

Baltimorean. I hardly need add,

that the picture of life and manners

here by an exceedingly clever English

caricaturist has about as much

vrai-semblance as if the beaux and

belles of Kamschatka had sat for the

portraits.39

CINCINNATI -- ATHENS OF THE WEST 25

Practically all of these observers

commented on the importance of the

hog in the Queen City's "way of

life," but unlike Mrs. Trollope, they did

not accentuate the negative and

eliminate the positive. If their accounts lack

the sprightly grace of Mrs. Trollope's

prose, they contain a more significant

ingredient -- namely, Truth.

A decade before Mrs. Trollope made her

historic appearance in Cincinnati,

Gorham Worth, an emigrant from the

Hudson Valley of New York, established

residence there. He arrived in the

southwest Ohio city with the customary

arrogant air of the Easterner and he

held the traditional preconceived notion

that Cincinnati must be one step removed

from savagry. Very quickly, Worth

experienced a transformation of

attitude. After attending a dinner at the

home of David Kilgour, a "First

Gentleman" of the city, Worth wrote:

Talk of the back woods! said I to

myself, after dining with Mr. Kilgour

-- by the beard of Jupiter, I have never

seen anything east of the

mountains to be compared to the luxuries

of that table! The costly

dinner service, -- the splendid cut

glass, -- the rich wines, -- the sumptuous

dinner itself! Talk to me no more of the

back woods, said I -- these

people live in the style of princes. I

did not, however, like my friend

St. Clair, after a great dinner at Findlay's,

mistake my longitude in the

dark, and walk off the bank into the

river! But I marched off most

heroically, over the stones, and through

the puddles, repeating to myself

at every step -- "talk to me no

more about the back woods!" -- "talk to

me no more about the back

woods!" always emphasizing the last two

words -- and before I reached home,

setting the line to music, and

repeating it, like the chorus of an old

ballad.40

While Worth's remarks referred to the

richness of material life, they also

could be applied to the intellectual and

cultural tone of the Queen City in

the pre-Civil War period. Historians

considering this aspect of Cincinnati's

history would do well to adhere to

Worth's dictum and talk no more about

the "back woods." Moreover,

they should talk less about hogs. This is not

to suggest that we should adopt modern

Russian historical values and sum-

marily inter Mrs. Trollope's

"Porkopolis" and resurrect the "Athens of the

West" in its place. Rather we

should recognize that pre-Civil War Cincinnati

was a two-headed coin, and it is time to

turn the coin over and take a look

at the hidden side.

THE AUTHOR: Louis Leonard Tucker

is Assistant Commissioner for State His-

tory in New York.

10 OHIO HISTORY

TO CINCINNATI*

by EDWARD A. M'LAUGHLIN

Fair is thy seat, in soft recumbent

rest

Beneath the grove-clad hills; whence

morning wings

The gentle breezes of the fragrant

west,

That kiss the surface of a thousand

springs:

Nature, her many-colored mantle

flings

Around thee, and adorns thee as a

bride;

While polished Art his gorgeous

tribute brings,

And dome and spire ascending far and

wide

Their pointed shadows dip in thy

Ohio's tide.

So fair in infancy -- O what shall be

Thy blooming prime, expanding like

the rose

In fragrant beauty; when a century

Hath passed upon thy birth, and time

bestows

The largess of a world that freely

throws

Her various tribute from remotest

shores,

To enrich the Western Rome: Here

shall repose

Science and art; and from time's

subtile ores --

Nature's unfolded page -- knowledge enrich her stores.

So sings the Muse as she with fancy's

eye,

Scans, from imagination's lofty

height,

Thy radiant beaming day -- where it doth lie

In the deep future; glowing on the

night

From whose dark womb, empires unveil

to light;

Mantled, and diademed, and sceptered

there,

Thou waitest but the advent of thy

flight,

When, like a royal Queen, stately and

fair,

The City of the West ascends the

regal chair.

* An excerpt from a poem found in a

collection of poems by Edward A. M'Laughlin

entitled Lovers of the Deep, which

was originally printed at Cincinnati in October 1841.

The 312-page volume was dedicated to

Nicholas Longworth. William T. Coggeshall, The

Poets and Poetry of the West (Columbus, 1860), 247-249.

(614) 297-2300