Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

|

PRESIDENT HARDING AND INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION

by DAVID H. JENNINGS

Even as President-elect Warren Gamaliel Harding was bidding his Marion neighbors a tender, moist-eyed farewell,1 world affairs engulfed him. "With the exception of Lincoln," said The Nation, "never have there been so many pressing and unsolved problems." The New Republic described the pressures as "truly awful."2 Each problem was individually intense and was made more so from the neglect occasioned by Woodrow Wilson's illness, Congressional stalling, and the understandable hesitancy of the President-elect. Among the

NOTES ARE ON PAGES 192-195 |

150 INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION

"pressing and unsolved

problems" was the question of America's policy

toward international organization. It

will be our purpose in this paper to

discuss President Harding's specific

policies relating to this matter in the

sequential phases of (1) his response to

efforts to secure American member-

ship in the existing League of Nations,

(2) his abortive attempts to secure

a substitute "association of

nations," and (3) his active campaign for United

States membership in the World Court.3

The League of Nations issue distressed

Harding despite his bland assur-

ance to his fellow townsmen that

"all will be well." Indeed, during the nearly

two and one half years of his

presidency, Warren G. Harding was constantly

occupied with the League matter. Every

circumstance surrounding the

making of foreign policy seemed to bring

up the distasteful subject. And in

the unavoidable necessity to deal with

the League of Nations issue in its

various forms the new President, most

significantly, was to alter his view

concerning the role of the Senate in

foreign affairs, his concept of the high

place of politics in American life, and

his attitude toward the use of emo-

tionalism or virtue-words in public

debate.

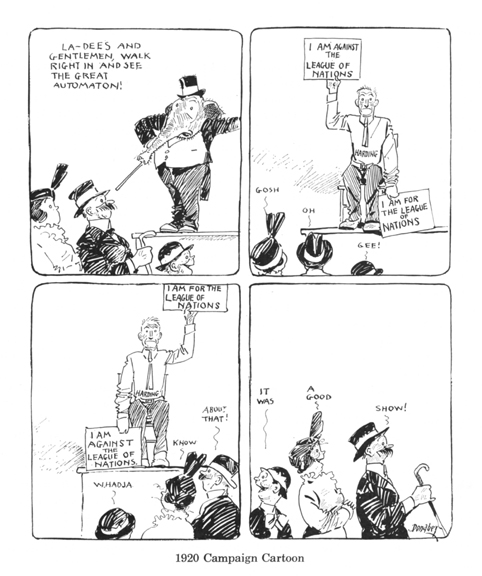

"Mr. Harding," said Herbert

Hoover, "carried water on both shoulders"

on the League of Nations issue during

the campaign of 1920.4 The Marion

man continued his wobbling between the

November election and the March,

1921 inauguration because he was caught

in the middle. An examination of

a significant number of letters to the

future Chief Executive during this

President-elect phase indicates a three

to one ratio against Wilson's League

of Nations.5 Moreover, not

only ordinary Americans but prominent figures

such as Hiram Johnson, Frank Brandegee,

and Henry Cabot Lodge advised

against American membership in the

Geneva organization.6 Yet, forces for

either joining the existing League or

forming an American substitute were

equally strong in emphasis and prestige,

if not in numbers. C. B. Miller,

Secretary of the Republican National

Committee, warned Harding that mild

and strong reservationist Republican

Senators were alarmed that the bitter-

enders on the League "are receiving

more consideration than is their due."7

Peace plans were submitted to the

President-elect, including one on a pro-

posed world court, from Marion, Ohio

friends.8 More to influence the future

than the present President, an open

letter to Woodrow Wilson imploring

him to "re-submit the treaty and

ratify it with reservations" was printed in

five hundred papers.9 Protestant

church and missionary leaders, including

Harding's close friend, Ohio Methodist

Bishop William E. Anderson, pleaded

the cause of peace through world

organization led by the United States.10

Among these powerful pleaders was

Hamilton Holt, co-founder of the League

to Enforce Peace and editor of the

weekly, The Independent. He had even

persuaded one hundred twenty-one of his

fellow prominent Republicans to

publicly announce their votes for

Democratic James Cox in 1920. Thus know-

ing full well Holt's power for mischief,

Harding heeded Holt's offer to aid in

drafting a plan for an international

organization. Since the President-elect

favored some form of league, he encouraged the editor

by suggesting that he

should indeed formulate a draft for a

proposed American association of

nations.11

INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION 151

The tug of war between anti- and

pro-League of Nations elements working

on the President-elect to commit himself

increased in intensity when two

new pressures appeared as inauguration

approached. First, from France,

Andre Tardieu issued a dramatic appeal

urging Harding to bring the United

States into the Geneva world

organization.12 Second, the League Council

made an indirect bid for American

membership in the League of Nations,

in a reply to Secretary of State

Bainbridge Colby's questions with respect

to mandates.13

Skillfully, however, Warren Harding

avoided the domestic and foreign

traps being prepared for him. On this

occasion, he brought his ability to

keep divergent groups in check by his

mastery of verbiage. This semantic

skill must be commented on because it

furnishes a significant key to under-

standing the Ohioan not only in foreign

policy but in all respects of his

public career.

As politicians use language it has two

main purposes -- to confuse and

to clarify. For a long time, historians

have marvelled at Harding's ability to

be confusing as he "bloviated"

on the issues of his day.14 The Harding Papers

furnish two new insights: the man born

at Blooming Grove not only practiced

the art of being unclear but

deliberately boasted of his skill in this respect.15

At the same time that he was publicly

ambiguous, "W. G." could be remark-

ably precise and clear in his private

correspondence, as the letters demon-

strate.16 In a letter to

Senator Lodge, the President-elect gave an honest, pre-

cise, and accurate estimation of the

League of Nations situation as he saw it.

I am quite as convinced as the most

bitter "irreconcilable" that the

country does not want the Versailles

League. I am equally convinced that

the country does wish us ... to bring

nations more closely together for

counsel and advice.17

But this was private writing. In public

oratory, an inaugural address, for

example, he must be circumspect. The

philosopher of word management for

purposes of obscurantism revealed his

awareness of the dangers of using

words clearly when he wrote a woman reporter

that his favorite lines of

poetry were these [as quoted by

Harding]:

Boys fly kites hauling their white

winged birds

But you can't do that way when you

are flying words.

Thoughts unexpressed they sometimes

fall back dead

But God himself can't kill them once

they're said.

Most significantly, the then Ohio

Senator added that "the question might

reasonably apply to other thoughts than

those of anger and impatience. I

have long since come to the conclusion

that the prudent [a favorite word

of the Senator] do not say all they

think."18

It is easy to understand, therefore, why

Warren G. Harding contemplated

a short inaugural address of twenty-five

hundred words or less. And while

it must be recorded that the President

did not succeed in this attempt, it

cannot be said he failed to keep

faithfully to his "middle of the road

philosophy." "Wariness is a

common attribute of successful political figures,"

152 OHIO HISTORY

David Shannon writes, "but few men

have equaled Harding's ingenuity at

devising variations on the theme of 'on

the one hand, and then on the

other.' "19

Shannon's judgment on Harding's

inaugural address is splendidly illus-

trated in the sections dealing with

America's role in international affairs.

The Chief Executive praised the

"wisdom of the inherited policy of non-

involvement in Old World affairs."

Since the United States did not want to

be "entangled," it "can

be a party to no permanent military alliance," nor

political or economic commitment

impairing our national sovereignty. The

American Republic, the speaker safely

insisted, wanted no world "super

government.'20 Although

Hamilton Holt and those of like mind also subscribed

to these sentiments,21 the

words were obviously intended for the isolationists.

But what did the President have for the

internationalists?

To the internationalists, Harding, whose

right hand invariably knew what

the left was doing, addressed these

glowing words:

We are ready to associate ourselves with

the nations of the world,

great and small, for conference, for

counsel; to seek the expressed views

of world opinion, to recommend a way to

approximate disarmament and

relieve the crushing burdens of military

and naval establishments. We

elect to participate in suggesting plans

for mediation, conciliation, and

arbitration, and would gladly join in

that expressed conscience of

progress which seeks to clarify and

write the laws of international

relationship, and establish a world

court for the disposition of such

justifiable questions as nations are

agreed to submit thereto.22

Despite the fact that President Harding,

while not mentioning the League

of Nations in his inaugural address,

still held out hopes for an association

of nations, a disarmament conference,

and a world court, the response of the

anti-League elements to the speech was

overwhelmingly favorable. With no

thought of his famed description of

Harding as "the best of the second

raters," Senator Frank Brandegee

praised the inaugural message fulsomely.

Indianians Watson and New called it

"magnificent" and "wonderful," re-

spectively. Lodge thought it

"admirable." Hiram Johnson declared that the

President's speech wrote "finis"

to the League of Nations.23

More important than what the anti-League

Senators said was the impres-

sive evidence that the new

Administration was, in fact, acting in accordance

with their ideas and policy suggestions.

Harding, according to a widely held

assumption, was about to send Elihu Root

to Europe with instructions to

set the groundwork for the organization

of an association of nations. The

Irreconcilables, pointing to an alleged

increase in their numbers since

November, advised the President not to

send Root abroad. If a meeting

should be held at all, it should be in

Washington. Actually, the best solution,

the advice continued, was to "lay

off the association" sessions completely.

None was held.24 Anti-League

Senators publicly declared that they had

urged Harding to give primacy to

domestic affairs.25 Far from being insulted

by the method employed, the Harding

Administration released a formal

statement that the cabinet meeting of

March 18 had dealt with major

domestic problems.26 The general belief

that there had been an "under-

INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION 153

standing"27 between President and anti-League Senators seemed to be

con-

firmed by the way in which the Harding

Administration dealt with the French

mission to the United States.

While Harding's inaugural address

disappointed Paris because of its failure

to mention the Allies,28 French

officials still believed that America would

accept the existing treaty of Versailles

containing the League of Nations,

stripped of Article Ten if need be. The

bases for their optimism rested on the

acceptance of the Viviani visit aimed at

American acceptance of the Treaty

and membership in the League, the

Hughes-Jusserand conversations that

were taking place, and the Root mission

supposedly about to begin.29

Senatorial "protectors of the

Republic," however, maneuvered, to prevent

French successes. They suggested that

Harding let the French people know

it was their government, not the United States, that

had initiated the dis-

cussions, that he be passive and not

take the lead in discussing an association

of nations; and, most important of all,

that he educate the Viviani group on

the facts of American life.30 Lest

their advice be not obeyed, the Irreconcil-

ables took part in a "concerted

plot" to have the colorful former French

premier meet the "right

people" among whom were Senators Lodge and

Knox.31 In reality, direct

contact by the Harding watchdogs was unnecessary,

for the President carried out their

advice anyway.32 The French were pleased

with the President's promise that the

Knox Resolution for a separate peace

with Germany would not be immediately

pushed and with the official Hughes

announcement that America deplored

German defiance of the Treaty of

Versailles. Viviani and Ambassador

Jusserand, however, were so clearly told

that an association of nations could not

be set up for sometime that a

reporter from Le Matin cabled his

newspaper the opinion that the Senate

would vote for the Knox Resolution

shortly. Moreover, he added, "neither

President Harding nor Secretary of State

Hughes nor the American Senate

will ever ratify the Versailles Treaty

or the League of Nations."33 The

education of the visitors had been

rapid.

Alongside the Senatorial burst of

anti-League energy and propaganda, the

efforts of peace groups and pro-Leaguers

appeared feeble. Hamilton Holt,

Thomas A. Lamont, and others sponsored a

"Nation-wide Tribute to Wilson"

and a lucrative essay contest in his name.

Through the pages of The Inde-

pendent, Holt challenged the new Secretary of State Hughes to

fight for

the seven reservations he had advocated

when President Wilson first brought

the preliminary draft of the Covenant

from Paris. Interestingly, even if

indirectly, the editor thus confessed

that he believed America had no chance

to enter the League Wilson desired. Holt

insisted that "if Hughes believes

now as he did a year and a half ago, he

would be willing to have the United

States enter the League provided only

the guarantee in Article X is omitted

and Article XXI is further

clarified."34 The rumor of Hughes's threatened

resignation as Secretary of State was

also badly handled by the Wilsonians.

To have adamantly pressed for the

reasons why the Secretary of State should

have contemplated resigning after less

than a month in office would seem to

have been the obvious way to expose the

Administration's foreign policy,

154 OHIO HISTORY

but the pro-Leaguers merely pleaded that

Albert Fall not be appointed to

the Secretary office.35 Though Samuel

Colcord devised a clever letter addressed

to Viviani informing him that most

Republicans were pro-League, the request

to allow its publication was not

answered by the Administration.36 Little

was accomplished by these pro-League

efforts.

The predominance of anti-League of

Nations elements in the 1921 March

debates and resulting developments

emboldened President Harding to be

crystal clear in his message on April 12

to the special session of Congress.

"In the existing League of Nations,

world-governing with its superpowers,"

the President said, "this Republic

will have no part."37 The recent election,

he explained, determined "that the

League covenant can have no sanction

by us."38 Then, perhaps remembering

the furor over his post-election "the-

League-is-dead" statement, Harding

insisted that in the 1920 campaign

"we pledged our efforts"

toward an association of nations "and the pledge

will be faithfully kept."39 American

membership in such an association would

preserve her peace and sovereignty.

Finally, rejecting the Knox Resolution

providing for a separate peace with the

Central Powers, Harding proposed

to arrive at a settlement with the

losers by working with the Allies through

the existing Treaty of Versailles,

minus, of course, the Covenant of the

League of Nations.40

The response of the Senate

Irreconcilables and their non-senatorial ideol-

ogical brethren to the Presidential

message was not as joyous as it should

have been, given the clear and final

rejection of the League of Nations. Along

with German leaders, they feared too

much American involvement with

London and Paris statemen, who gave

their "cordial approval" to Harding's

proposed peace treaty arrangements. The

Irreconcilables demanded that the

Knox Resolution be carried out.41 The

New York Evening Post reflecting

common disturbances over a new league,

laid down five "essential conditions"

for its making, all of which jealously

guarded against the "surrender of

sovereignty."42

Still another matter troubled the Old

Guard. Around the middle of May

1921, the Administration appointed

American representatives to the Allied

Supreme Peace Council, the Council of

Ambassadors, and to the Reparations

Commission. The joy of the internationalist

editors was matched by the

gloom of the isolationist ones. The

United States "is about to be again

entangled in the politics and intrigues

and quarrels of Europe," Hearst's

New York American stated. Despite

the fact that none of the above three

bodies was responsible to the League of

Nations, The American then issued

a warning to Harding that unless he

became less like Woodrow Wilson "there

will be little use in nominating

Republican candidates for office next year.43

The rejoinder of the Marion Star to

all of this was especially significant

because Harding kept in contact with the

newspaper which he owned and

edited. "Not since the Declaration

of Independence in 1776 has the United

States maintained an attitude of either

theoretical or practical isolation," its

editor declared.44

INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION 155

The fears of the isolationists proved

groundless as developments between

April and October 1921 rendered American

membership in the existing

League of Nations almost impossible. On

May 19, Ambassador George Harvey

rocked two continents with his Pilgrim's

Day dinner speech statement that

the 1920 election meant that Americans

wanted to have nothing to do with

the League of Nations. Adding insult to

forthrightness, the former warrior

for the League for the Preservation of

American Independence warned his

distinguished audience, among whom was

the Prime Minister, that England

had better cease its efforts to

"entice" or "beguile" the United States into

joining the infamous trap. "Then

why did America send its manhood to

Europe?", asked the self-styled

"unalloyed American." "Solely to save the

United States," was his reply.45

Although Secretary of State Hughes expressed

his dismay over the discourtesy and the

ideas advanced, President Harding

in private correspondence and a public

address praised the Ambassador's

speech.46 Lord Robert Cecil was among

those "dwindling number of Leaguers,"

as Harvey sarcastically put it in a

letter to Harding, who were offended by

the speech.47

If Harding could join other Americans in

brushing aside Harvey, he could

not do the same for colleagues, whom he

deeply respected. At the President's

request, Ambassador Washburn Child in

Italy, James P. Goodrich, former

governor of Indiana on special mission

to Russia, David J. Hill, scholar of

international relations, and Nicholas

Murray Butler wrote long letters or

memorandums giving their opinions on the

European scene, particularly with

respect to the League of Nations. Hill

portrayed a discouraging European

scene and recommended that the

Administration keep clear of it.48 Butler,

trying hard to be Harding's Colonel

House by being regarded as the Presi-

dent's emissary in the European capitals

he visited, disclosed a uniform lack

of interest or confidence in the League.

Included among those statesmen that

he found to be uninterested, was Paul

Hymans, president of the League

Assembly!49 Surely the Chief

Executive must have noted that this last

comment came from the president of

Columbia University who formerly had

been among the most ardent Republican

supporters of Wilson's interna-

tionalism.

Butler was neither the only nor the most

important Republican who was

forced to accept a change of attitude

toward the League. Among the most

important reasons why the United States

did not enter even a revised

League of Nations was the fact that the

Secretary of State could do little

to promote the campaign for entrance,

either. Charles Evans Hughes, dis-

tinguished signer of the "Committee

of 31" statement in the campaign of

1920, believed that to open another

"Great Debate" would not only fail to

obtain American entrance but would

prevent the formulation and execution

of other foreign policies equally

important to the security of the United

States and the peace of the world.50

Thus the power of the anti-Leaguers

precluded discussion. Hughes, sorely

hurt when pro-League friends did not

understand this, frequently defended

himself against his critics. A study of

156 OHIO HISTORY

the "Beerits Memo" in the

Hughes Papers and the many evidences in the

Harding Papers would also suggest that

the frequency of rebuttal was

occasioned by a guilty conscience.51

The Harding Papers reveal, also, the

almost step by step influence that

Hughes exercised on the President in the

formulation of foreign policy --

silence toward the League; next cautious

probing followed by open contact

with it; then the proposals for the Washington

Conference, an association of

nations and, finally, the World Court.

From a personal relationship starting

out with Harding so awed by Hughes that

he asked Hoover to handle one

initial item of business rather than

bother the cold, formal Secretary of

State, their contacts developed into

friendship and concern beyond the duties

of their positions. As for foreign

policy, the influence of the Secretary of

State upon the President is unmistakable

both as to policies pursued and,

especially, their timing.52

It must not be forgotten, however, that

stronger than the Hughes' influence

behind Harding's foreign policies were

the President's own personal convic-

tions and outlook. Harding's speeches

and writings, especially as Senator

and campaigner in 1920, furnish an

ideological portrait of the typical nine-

teenth century, or historical,

isolationist. Along with the traditionalists, the

Chief Executive looked upon the American

as a superior free and moral

human being. Harding had a disdain for

European autocracy and aristocracy

as contrasted with American democracy,

especially in rural America. He was

highly suspicious of the European

balance of power system and its makers --

a suspicion ever present in his attitude

toward the Treaty of Versailles and

its first part, or Covenant, of the

League of Nations. His frequent use of the

words "noninvolvement" and

"nonentanglement" demonstrated his belief

that strong, virile, patriotic

"unadulterated" nationalism, in contrast to

"paralyzing internationalism,"

was the best means of obtaining security for

America. As stated in the inaugural

address, the United States could best

serve mankind by acting as the noble,

enlightened, dedicated example while

ever preserving her complete sovereignty.53

Modifications in the strength

and expression but not the essence of

these views occurred during the

Ohioan's presidency. The minor

adjustments are probably to be accounted

for by the Hughes-Hoover influences and

the necessity of the man in the

White House to look constantly at the

world, not merely Ohio. Denna F.

Fleming's early judgment that Harding

was a strong reservationist with

irreconcilable leanings is still

sound.54

While Samuel Colcord might point to

hyphenated German-Americans

pressing the President or others such as

the Irish-American protesters55 as

the decisive factor, it was the

completion of peace negotiations with Germany

which finally ended America's

possibility for entering the Geneva League.

This occurred when Congress cancelled

the Declaration of War of April 6,

1917. The President created an uproar

when he signed the joint resolution

between rounds of golf on a July

afternoon. In anger or humor, newspaper

men were soon dubbing the deed as the

"peace by edict," or even, the "farce

at Raritan."56 The

ratification of a peace treaty with Germany was com-

INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION 157

pleted on October 18, 1921. Worried

about the reaction of the British

Government because the United States

needed their approval to be expressed,

Hughes instructed Ambassador Harvey to

try to make English officials

comprehend the American problems.

"The Government to which you are

accredited will understand," he

wrote with more hope than he may have

felt, "that it would have been idle

to expect the United States to enter the

League of Nations under the present

circumstances or to assume responsibility

with respect to questions that are

distinctly European."57

Charles Evans Hughes and the United

States Government lost the Treaty

of Versailles twice in the summer of

1921. Once in the diplomatic process

described above. The second time in a

literal and physical sense. And to

justify the assertion that the

"Lost Peace" was really lost, one of the weirdest

incidents in the handling of diplomatic

documents must be described. Here

was an occasion, as the narrative will

show, in which even Woodrow Wilson

would have approved of secret diplomacy.

On July 11, 1921, Hughes wrote to the

President's secretary, George B.

Christian, Jr., that "There are

some inquiries, with obviously humorous

import, as to where, physically, the

Treaty of Versailles is at this time." He

begged Christian to search the White

House so that the Secretary of State

would not have to make "a confession

of ignorance . . . which might be a

subject of some comment." From the

White House came the immediate

news that they knew nothing about it

save that Foster, longtime career

servant in foreign affairs, believed

that Woodrow Wilson had the treaty.

Hughes practically ordered a search of

the White House in his next note.

By the following day, July twelfth,

Christian could inform Hughes that a

"careful search" had been made

"but in vain." The time from the thirteenth

to noon of the fifteenth of July was spent

in contacting Wilson at his

Washington home and in rehearsing

Harding as to what he should say if

asked about the matter at a press

conference scheduled for the afternoon of

the fifteenth. Lest anyone believe that

the wheels of government at Wash-

ington cannot turn rapidly, let him heed

the speed with which communications

flew around on July fifteenth. Four

written communications made the rounds;

a courier ran over to the President's

press conference, stayed there during

it, but unfortunately, though the

document was discovered, news could not

get to Harding in time. Perhaps the coup

de grace was furnished by a

postscript in Woodrow Wilson's letter of

transmittal. He asked for a "formal

receipt" that the transfer had been

effected.58

As the decline of America's prospects

for entrance into the League of

Nations rapidly diminished between April

and October 1921, joy and con-

sternation developed in the ranks of

anti- and pro-Leaguers. Their reactions

can be observed by noting the personal

responses of some of the combatants.

What changes time can bring! In the

spring of 1919, Senator William E.

Borah, the leader of the

Irreconcilables, was so fearfully convinced that the

Wilson League would triumph that, busy

as he was, the "Lion of Idaho"

accepted an invitation to address a

Fourth of July gathering on the grounds

that "this might be the last

Independence Day for the land I love."59 Now,

158 OHIO HISTORY

in 1921, Borah felt strongly that

America would not enter the Geneva

organization directly but that it might

go into some substitute arrangement.

The Senator assigned himself the task of

being "the guardian of the back-

door."60 Glenn Frank

expressed his shock in the slump of idealism which

had taken place in the first four months

of the Harding Administration. He

called it the "lost spirituality of

politics."61 Hamilton Holt, after charging

the President with outright dishonesty

on the League issue and threatening

ballot box consequences,62 recovered

his largeness of view in "A Memorial

Day Editorial." Holt used two

columns to contrast the years 1918-1919

against those of 1920-1921 with respect

to the American outlook on foreign

affairs. Internationalism and dedication

had given way to isolationism and

selfishness. The peacemaker reproduced

William E. Brook's poem "Into the

Night" the last line of which

exemplified the editor's mood at the time:

"I envy the ones who died,

believing!"63

Yet there were those, including Holt,

who hoped that the Administration -

proposed Washington Conference might

turn itself into Harding's association

of nations or, if not this, then some

other permanent political commitment.64

Whatever the form of expression,

however, internationalism once more came

alive during the November 1921-February

1922 conference.

The League of Nations issue was present

in the circumstances surrounding

the Washington Conference. The fact of

the conference's existence en-

couraged citizens to submit plans for a

new covenant, a world navy, and an

international court.65 Anti-Leaguers

boasted, as some foreigners feared, that

the success of the conference,

especially if it became an annual affair, might

destroy the Versailles League.66 The

disarmament achievments in Washington

were praised for purposes of deprecating

the failures at Geneva in this

area.67 During this period

overtones of the Great Debate of 1919 were ever

present, beginning with the selection of

the American delegation to the

reservation discussions in the Senate,

especially on the Four Power Treaty.

Democrats, joined by Borah and Johnson,

embarrassed Henry Cabot Lodge

by charging he was willing to sacrifice

more American sovereignty than he

had wanted to concede to Wilson's League.68 Significantly,

however, sup-

porters of the former President made

their contrasts and comparisons more

for the purpose of ridicule than to

revive Wilsonianism.

American internationalists who hoped for

the Washington Conference to

be extended into a permanent world body

looked toward American member-

ship in an association of nations rather

than the League of Nations, as the

more realistic possibility. It was to

the association idea, not the League, that

Harding had committed himself during the

campaign of 1920, as President-

elect and in public and private

statements right up to the time of the

Disarmament Conference. To Nicholas

Murry Butler, Harding wrote: "I

need not tell you how agreeable it will

be to me if it [Washington Conference]

proves the means of fulfilling the

promise that I repeatedly made to the

American people during the late

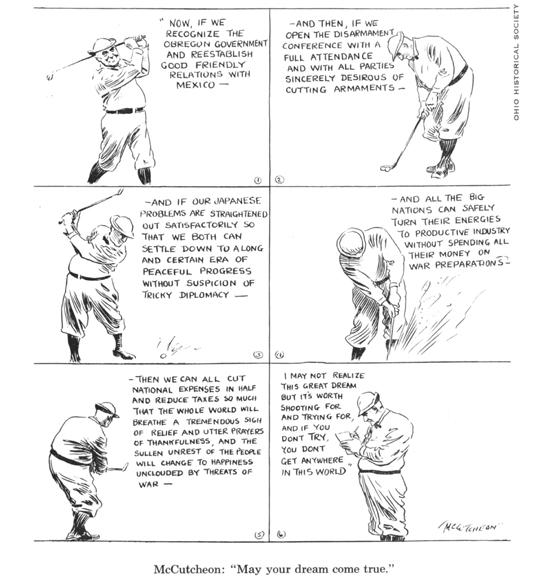

campaign."69 The President's impressive

speech in dedication of the Tomb of the

Unknown Soldier on November 11

and both his and Hughes's addresses at

the opening session the next day

|

INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION 159 |

|

further encouraged the association of nations' backers.70 The New York Times and The Independent as well as several foreign papers estimated that the major reason for calling the Washington Conference was not to achieve disarmament but rather to obtain the "Association of Nations."71 Anticipation, however, greatly exceeded realization. Although Harding made a general reference to the association of nations at the close of the Washington meetings, the Conference ended with nothing done with respect to this substitute proposal for the League. The Pittsburgh Post summarized the prevailing situation when it declared: "The most persistent question at |

160 OHIO HISTORY

the time of the inauguration was: What

will President Harding do to bring

about an association of nations? After a

year the question is as far as ever

from being answered."72 By

September 1922, the question was even farther

from being answered. From the Brussels

embassy, Henry P. Fletcher sent

three copies of a "Draft Proposal

for a World Association" drawn up by a

Committee of the Institute of International

Law. Fletcher also sent worried

notes to Hughes and Harding pointing out

that the coming sessions of the

entire organization at Grenoble, France

would carefully weigh and perhaps

adopt the plan to get the United States

into the new world organization to

be set up as a loose confederation

between the League of Nations and the

Pan American Union. With a sigh of

relief, Fletcher later reported that the

matter had been dropped. Hughes was made

happy by the news and the

President summarized his own career and

attitude toward the association

of nations idea in these revealing

words:

I am very glad to have a copy of this

proposal for my information.

Apparently it avoids the objections

urged against the League of Nations,

and is in harmony with my RATHER HAZY

CONCEPTION which

attended a promise of sometime finding a

way for an Association of

Nations. I have always believed that

such an organization might be made

possible and that great good could come

of it without granting to it the

super-authority which was strongly

opposed in the anti-League fight in

the Senate. I do not think, however,

that the psychological moment has

arrived in this country to promote such

an enterprise.73

The "psychological moment" had

not arrived a short time later, as Harding

told Fletcher in another letter.74 Nor

did it ever. The wonder, in fact, is why

the American press became excited about

the association of nations in view

of the factors working against the

proposal which should have been obvious

to editors throughout the land. The same

basic Irreconcilable objections to

the League of Nations would, also, apply

to the association scheme. Indeed,

at the start of his Administration the

Irreconcilables made this known to the

President.75 Each passing day made the

League of Nations more of a going

concern and lessened the chance of the

Great Powers resigning from it.

Actually, as early as June 1921 Sir

Edward Grey stated that his Government

had no intention of leaving the League

of Nations for any American-sponsored

enterprise. American diplomats abroad

substantiated this statement as the

intention of France as well as England.

Moreover, the impact of the Great

War which had inspired sober

consideration as to whether America should

enter the Versailles League had

disappeared by 1922 and thus made United

States entrance into a new league even

less likely. The famed mood of the

1920's was spreading over the land.

Thus, Charles Evans Hughes wisely came

to the conclusion that "any

American suggestion of a new peace organization

just after this country had abandoned

the existing League . . . would have

been laughed to scorn in Europe, and it

would have been little more acceptable

to the Senate .... We have been dealing

with matters in a practical way

[Hughes wrote to President Lowell of

Harvard] and have accomplished a

great deal. [Yet] if there are those who

think they should renew a barren

INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION 161

controversy, that is their right. But

[he added] nothing good will come of

it, and very likely it will stand in the

way of much that might otherwise be

accomplished."76

The greatest part of "much that

might otherwise be accomplished" was

American membership in the Permanent

Court of International Justice or

the World Court. The factors impelling

the Court crusade and the way in

which President Harding conducted his

campaign for it tell much about the

American mind of the times. Even more

significant for this study, the

campaign shows a change in Warren G.

Harding.

The World Court movement came alive in

February 1923, as a consequence

of several developments which aroused the

American people and their leaders

from the lethargy that had crept over

the country following the Conference

on the Limitations of Armaments. With an

awareness of the situation, H.

Landon Warner has written of the

"seemingly moribund League movement."77

The word "seemingly" was well

chosen, for a change in public interest had

come about. For example, in early

September 1922, Supreme Court Justice

John H. Clarke had resigned "to

serve my neighbors and some public

causes."78 Following

some frustrating embarrassing negotiations and the

uncertainty of former President Wilson's

attitude, the League of Nations

Non-Partisan Association was formed and

became most active by 1923.79

Clarke, Holt, Lowell, Raymond Robbins,

and George Wickersham then

flooded the country with the

Association's speeches and pamphlets. Also the

congressional elections of 1922

decreased the Republican majority in the

Senate from twenty-six to six and in the

House from one hundred sixty-seven

to fifteen. Although it was probably the

domestic factors -- the slowness of

economic recovery, the Farm Bloc and the

Progressive dissatisfaction --

which mainly account for the heavy

Republican losses even for an off-year

election, foreign policy implications

were also noted in the post-mortems.80

Domestic and foreign publications

discerned dissatisfaction with foreign

policy in the election results. Senator

Lodge's narrow margin of victory did

not go unnoted.81 In addition to these

changes, Secretary of State Hughes

had much to do with the decision to

launch the World Court campaign. He

believed, in contrast to his attitude to

the League of Nations and association

of nations proposals, that American

membership in the Court was politically

feasible, indeed desirable.82 Freely

confessing his awareness of the American

people's discontent with his policies,83

Harding, himself, was also willing to

make changes.84

On February 24, 1923 President Harding

sent a message to the Senate

requesting its "adherence" to

permit the United States to join the Permanent

Court of International Justice. The

President pointed out that the World

Court was based on an idea clearly in

line with American emphasis on the

peaceful settlement of international

disputes and, given its already effective

functioning, would add prestige to

America if she became a member. In

presenting the message, Harding also

included a letter from Hughes to himself

containing four

"reservations," spelling out America's minimal involvement

162 OHIO HISTORY

with the League of Nations and

safeguarding her equality in the limited

contacts.85 It was Hughes,

again, who wrote replies to ensuing inquiries and

comments from the Foreign Relations

Committee. Indeed, the Secretary of

State was so active that newspapers

began to speak of the "Hughes Proposal."

In some embarrassment the Secretary

wrote a note of apology to the

President.86

Both men, however, were equally

enthusiastic about the entry of the

United States into the World Court and

seemed relieved to have discovered

a politically feasible middle ground

between the League of Nations or associa-

tion of nations and isolationism,

desired by neither man. It was the President

who pulled together the elements

involved:

Not many days ago I made the observation

to my newspaper callers

that I did not believe any man could

confront the responsibility of . . .

President . . . and yet adhere to the

idea that it was possible for our

country to maintain an attitude of

isolation and aloofness in the world.

I am keenly desirous that the right

course shall be found, whereby our

favored country may make its largest feasible

contribution to the

stabilization of civilization, while at

the same time surrendering nothing

of the advantages and independence which

we enjoy. After much thought,

study, and conference, I reached the

conclusion that our adherence to

the program of the International Court

represented a compliance with

these conditions.87

The response to the World Court

proposal, however, touched off a discus-

sion similar in its elements and

intensity to the Great Debate of 1919. Public

and private opinion held that this would

be the foreign policy issue of the

1924 campaign even as the League of

Nations had been in 1920.88 In general,

the pro-Wilson groups (up to the time of

the St. Louis speech of June 21),

the Hughes-Hoover-Coolidge combine in

the Administration, peace societies,

and the Federal Council of Churches with

its mighty nationwide pressuring

of Protestants, supported the President.

So, too, did most newspaper editors.89

An equally powerful and more vociferous

group opposed Harding in "uncom-

promising opposition." Those in

this category included the Hearst news-

papers, the Irreconcilables led by Hiram

Johnson and Senator Borah, and

"the National, Senatorial and

Congressional [Republican] Committees."90

On Memorial Day the World Court issue

was dramatically joined when

President Harding and S. T. Adams,

Chairman of the Republican National

Committee, spoke to America. "I

believe," said the Chief Executive, "it is a

God-given duty to give of our influence

to establish the ways of peace through-

out the world." Not so, countered

Adams. "The Republican national organiza-

tion will . . . continue to review and

discuss political problems from the

standpoint of 'American First.'"91

Initially, Harding was inclined to view

the "great hubbub" as "largely

bunk," originating with

anti-Administration senators and among those "who

are nuts either for or against the

League."92 Soon, however he was convinced

that compromise was necessary. At St.

Louis on June 21 on his "voyage of

understanding," as he called his

fatal tour to Alaska, Harding laid down

INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION 163

"two conditions" for American

entrance into the World Court. One was the

old "plane of perfect

equality" insistence. The other involved separation of

the Court from the League of Nations.

Stressing the demand for divorce

between Court and League, Harding

proclaimed that the League issue was

"as dead as slavery."93

In this wooing of the Courts critics, the President

offended some of its friends. From the

officers of the Non-Partisan Association

for the League of Nations came a

lengthy, passionate telegram informing the

weary executive that millions of

Americans, including most of them, if their

long list of organizations be correct,

favored American entrance into the

League of Nations as well as in the part

of it known as the Permanent Court

of International Justice.94 Shortly,

thereafter, Hiram Johnson attacked the

modified approach which had irritated

the pro-Leaguers.95 With Hughes

"sitting on the lid" in

Washington, the President called Hoover for consulta-

tion and advice on forthcoming foreign

policy speeches.96 Thus it was that

not only the tragedy of domestic scandal

but also the wearisome problems

of foreign policy oppressed Warren G.

Harding when death occurred on

August 2, 1923, in San Francisco.

At the end of his career, Warren G.

Harding was a different being from the

person who had taken the presidential

oath on March 4, 1921. For while

Harding did little to alter the status

quo with respect to America and her

participation in international

organization, his wrestling with this issue under

the power and responsibility of office

effected changes in him. The modifica-

tions cannot be itemized as Samuel

Hopkins Adams so erroneously believed --

and so incorrectly itemized,

incidentally.97 The differences can be shown to be

in the areas of personal philosophy and

attitudes.

During his presidency, Harding altered

his rhapsodic approval of the

division of responsibility and power

between President and Senate in foreign

affairs provided for by the

Constitution. During the pre-election Great Debate

of 1919, the Ohio solon felt it was the

Senate that had saved the United

States when it "insisted upon

safeguarding America when the President

[Wilson] proposed to submerge our

nationality in a super-government of the

world."98 But the

responsibilities of power, the Washington Conference, and

especially the World Court fight made

President Harding change his mind

about the prerogatives of the Senate in

foreign affairs. Senators, he bemoaned,

forgetting his own career, raise

"petty political issues" in foreign policy to

promote their Presidential ambitions,

their need to get elected or even "their

own personal vanity."99 Thinking

men, he wrote to a friend, "must resent a

spectacle of a Senator Borah going about

with a great flourish" with solu-

tions for everything when he has no

responsibility for performance.100

In foreign policy, Harding declared, he

became used to the "perfectly need-

less and almost childish

reservations" sponsored by Frank Brandegee and

other equally irresponsible prima

donnas.101 At a critical point in the Wash-

ington Conference, Harding concluded

that if the Senate failed to ratify the

Four Power Treaty, "we will have

pretty thoroughly established the fact that

our government is of such a character

that no Executive can very successfully"

|

164 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

carry on foreign policy. Woodrow Wilson couldn't have complained more.102 In one of his most philosophic moments, the former admirer of "harmonizing politics" was driven to this solution: In simple truth, I get discouraged about the stability of popular government, when I come in contact with the abject surrender of public men to what appears to be one half of one percent of the voters to whom they look for their commission to public service. What the country needs more than anything else is a House and Senate for ten years which gives at least as much time to the welfare of the Republic as is given to the individual candidacies for re-election.103 Harding was not only becoming tired of congressmen and senators admit- ting they liked a given foreign policy while saying they did not dare vote for it104 but also of the concept of Americanism they peddled to retain office. He who had once used "America First" four times in one sentence105 and talked frequently about "Red-Blooded" or "One Hundred Percent Americanism," now rebuked a Kansas City citizen who asked him to put some "Old Glory" into his presidential tour speeches in 1923, even as he once had as senator and presidential candidate. To Malcolm Jennings, the middle man for this advice, Harding wrote, "I fear Mr. Clarke is greatly lacking in confidence and has a bargain sale appraisal for the President." Much as he might want to please Clarke, however, a president of the United States handled greater problems and had to have larger vision than an "Old-Glory" talk could provide.106 If the President had abandoned narrow Americanism and the use of virtue-words, he, equally significantly, had forsaken the primacy of party. |

|

INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION 165 |

|

|

|

"No one need have any serious concern about the World Court matter dividing or destroying the Republican Party," he wrote to Charles Dawes. "If the administration's recommendation of adherence is going to split the party and thereby endanger its usefulness, I am well persuaded that the party has reached a stage where it can no longer be very useful as an agency of government."107 While Harding's death makes it impossible to know whether the attitudinal changes noted would have endured, it is a fact that modifications in philosophy did occur. However temporary, the President had been forced through the necessity of dealing with international affairs to see the inadequacy of his former political gospel. That former gospel had contained a somewhat provincial view of America in its relation to international organization and had given priority to party harmony above the need to formulate definite foreign policy positions. Yet, whatever the reason -- and this writer, as noted, sees some growth toward a larger world prospective -- President Harding, while never accepting the Wilson League of Nations, did offer repeatedly to consider a substitute association of nations proposal, which he finally saw manifest in American membership in the World Court, a membership he was strongly advocating when he died. This much cannot be denied.

THE AUTHOR: David H. Jennings is Professor of History at Ohio Wesleyan University. |

|

PRESIDENT HARDING AND INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION

by DAVID H. JENNINGS

Even as President-elect Warren Gamaliel Harding was bidding his Marion neighbors a tender, moist-eyed farewell,1 world affairs engulfed him. "With the exception of Lincoln," said The Nation, "never have there been so many pressing and unsolved problems." The New Republic described the pressures as "truly awful."2 Each problem was individually intense and was made more so from the neglect occasioned by Woodrow Wilson's illness, Congressional stalling, and the understandable hesitancy of the President-elect. Among the

NOTES ARE ON PAGES 192-195 |

(614) 297-2300