Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

|

The Chillicothe Germans

by LA VERN J. RIPPLEY

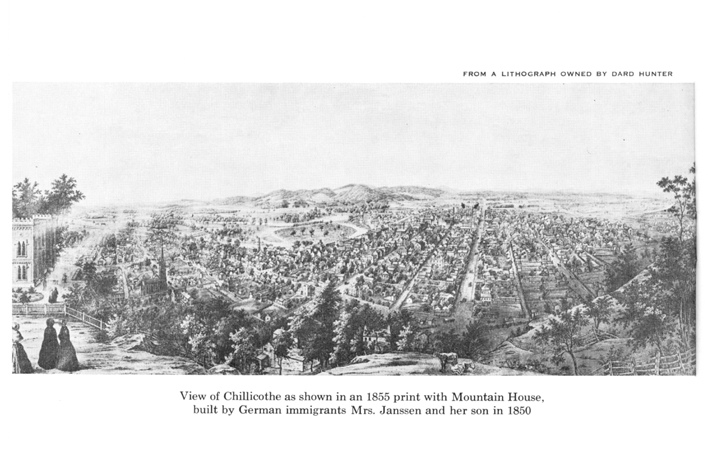

For nearly a century an element of German culture could be observed in the community life of Chillicothe, Ohio. Until World War I brought an abrupt end to the general use of their language, the Germans developed their own churches, schools, publications, cultural societies, and special activities on a scale comparable with other Ohio localities. Now, however, half a century later, the Chillicothe Germans as an ethnic group are little more than a dim memory. Reliable information concerning the earliest German immigration to Chillicothe is scanty.1 By the 1830's the first substantial migration to the United States began; by 1840 the German immigrant group comprised perhaps ten percent or more of the total population of Chillicothe; and by 1850, following the greatly increased migration of the second half of the 1840's, it constituted nearly a third of the population. In the ensuing two decades, it became even larger than a third. By 1880, however, the relative number of Germans began to diminish as the later settlers were

NOTES ARE ON PAGES 270-273 |

THE CHILLICOTHE GERMANS 213

attracted to larger industrialized

cities in the United States. Yet in 1910,

persons of German birth and the

native-born whose parents were both of

German birth still formed more than ten

percent of the city's population.2

German cultural and social activities

came to Chillicothe as a natural

by-product of the immigration. Perhaps

first in point of time and strangest

in furthering cultural identity were the

German-language churches, which

were mostly Catholic and Evangelical.

Catholic organization was started

by Martin Baumann and his wife, nee

Ludwig, in 1817. As the German

population increased, services were

conducted intermittently by Dominican

priests from Somerset, Ohio. In 1837

Father Henry Damian Juncker, later

bishop of Alton, Illinois, became the

first resident pastor of the Chillicothe

parish and conducted services in the St.

Mary's Church on Walnut Street.3

From 1834 to 1845 Father Amadeue Rappe,

later bishop of Cleveland,

served the parish and also laid the

cornerstone for a new church, St. Peter's.

In 1847 the congregation was transferred

to Jesuit tutelage, and two years

later, Fathers Xavier Kalcher and Aloysius

Carroll divided the parish into

German and English-speaking elements.

Those speaking English were

assigned to St. Mary's Church and the

German-speaking group to the

newer St. Peter's.

Father Kalcher was Jesuit as well as

German and was vitally concerned

with education. He succeeded in

attracting a community of German nuns,

who had at first settled in Toledo, to

open a school. This school was estab-

lished as a regular boarding unit in

1849. Since no public schools were con-

ducted in the German language, the new

school at St. Peter's was patronized

by Protestant as well as Catholic

Germans.4

Perhaps because such an

"ecumenical" arrangement proved unsatisfactory

to both denominations, an attempt was

made in 1851 to open a private,

nonsectarian school. That such an

organization attempt was successful is

shown by the following announcement of

April 1851 in the local German

newspaper: "On the seventh of the

month, the undersigned [G. C. Pape,

Teacher] began a German-English school,

which is independent of political

and religious sects. Parents who wish to

send their children may inquire at

the school on Second Street in the

Masonic Hall or in the office of Dr.

Zanders."5

Beginning in 1851 and continuing for

thirty years at the helm of St.

Peter's parish and school was Father

Edward Lieb, who, as an Austrian

Capuchin, had lived seven years at the

royal court of Vienna as tutor of

the Archduke Maximilian, later emperor

of Mexico. Lieb was followed,

1881-1896, by Father Ernst Windthorst, a

nephew of the Catholic leader

in the Reichstag. While the German

tongue persisted as the official language

for parish records and worship until

long after his departure, Father Wind-

thorst, nevertheless, found it advisable

to have the 1896 jubilee booklet

printed as a dual language edition.6

In June 1905, St. Peter's hosted the

Ohio convention of the German

Roman Catholic Society, a national

organization begun in Baltimore in

1855. Its purpose, which was to foster

Catholic interests and to protect the

214 OHIO HISTORY

spiritual and civil rights of German

Catholics in America, is epitomized in

a speech by August Sulzer, chairman of

the preparations committee. While

trying to instill enthusiasm for the

Catholic Society as a German organiza-

tion, he still seemed to apologize for

the existence of German-Americans

as a select group. He was careful,

however, to praise St. Peter's for teaching

the German language, for the retention

of German traditions in its school,

and for having had two pastors who later

became bishops. Because of its

local importance, the German-language

newspaper devoted its front and

back pages to coverage of the

convention.7

The German Evangelical Protestant Church

also played a vital role

in fostering German culture in

Chillicothe. This church was first organized

on an informal basis by traveling

ministers who usually preached in a

Pennsylvania-German dialect. By 1833

eight German immigrants invited

the Reverend Rosenfeld to conduct

regular services in a chapel located

above Fliderer's Bakery. Within the next

four years so many new members

were added to the group that it was

possible to establish a formal organiza-

tion. The First German Evangelical

Lutheran Church was incorporated in

1837, and a two-story frame house at the

site of the present church was

purchased. Later, in 1857, because of a

dispute over whether this group

should belong to the Lutheran or the

Reformed Church,8 the congrega-

tion as originally organized was

dissolved. Many members then joined the

German Methodist Church. As a branch of

the English-speaking Methodists,

this congregation had its own building

and pastors from 1850 until 1915,

when it also was dissolved and the

members joined other Methodist groups.9

The 1857 dissolution of the Evangelical

Lutheran Church was not per-

manent. Within a decade it was not only

reformed but was also able to

support its own parochial school. The

school, however, was soon abandoned

when its sole teacher gave up the

ministry to become the German teacher

in the public school. An 1877

controversy split the congregation a second

time, and one offshoot became the Salem

Evangelical Church, which promptly

joined the German Evangelical Synod of

North America. Salem Evangelical

continued its German traditions stoutly

until 1896, when Reverend Joseph

Reinicke introduced the English language

for Sunday evening services

while continuing the German in the

mornings.

Meanwhile the other splinter group

renamed itself the Free German

Evangelical Protestant Church. This

congregation continued to use German

exclusively until 1897. In that year

"a lamentable thing occurred."10 For

a long time the leaders had realized the

need for English services, German

having become a less and less

intelligible tongue for the younger generation.

Since no convenient means could be found

for introducing English into the

worship service, a number of younger

members withdrew and set up

the Calvary English Lutheran Church

within a block of the older church.

From 1897 this new church offered the

pastorate to free preachers, but

in 1905 it turned to the German

Evangelical Synod of North America for

its ministers. Soon to arrive was the

Reverend F. H. Graeper who began

THE CHILLICOTHE GERMANS 215

"progressive measures," two of

which were the introduction of English

services that had become necessary for

the younger generation and the

founding of a Young People's Society.11

In 1919, the way was paved for

the reunion of the Evangelical

Protestant Church with the Salem Congrega-

tion to form St. John's Evangelical. At

the last minute, however, the merger

failed to be approved, and the churches

have continued separately as

English-speaking churches to the

present, with pastors and parishioners

German in name only.

Religious life was not the only force

fostering German cultural identity

in Chillicothe. Probably the most active

for creating nationalistic feelings

and esprit de corps were the

gymnastic, rifleman's, and singing societies.

Generally, the societies were more or

less affiliated with district and national

associations throughout all of German

America. Chillicothe was no exception.

Although information is scanty, we know

that in 1837 a military organiza-

tion called the German Grenadier Guards

was formed in Chillicothe, with

Michael Kirsch as commander. Its

function appears to have been primarily

ceremonial, judging from its colorful

uniforms and lack of true military

engagement.12 Later the group

was renamed the Washington Guards. It is

stated that the guards presented an

annual German ball to raise money

to buy musical instruments -- additional

evidence that shows the guards'

function to be musical-ceremonial.13

Whether the unit ever turned exclu-

sively to military endeavors is not

known. At any rate, during the Civil

War the Thirty-Seventh Ohio Voluntary

Infantry was the third German

regiment raised in Ohio and included a

German company from Chillicothe. It

engaged in the battles of Vicksburg,

Missionary Ridge, Resaca, Kenesaw

Mountain, and Atlanta. On active duty

its officers included Frederick H.

Rehwinkel, Paul Wittich, Jacob Litter,

Adolph von Kissinger, William

Weste, and Julius Scheldt.14

The local rifleman's and gymnastic clubs

were of short duration, but the

contrary is true of the singing society,

Eintracht. The singers certainly

stimulated the most effective and

distinctively German spirit in Chillicothe.

The Eintracht was founded in 1852

by Joseph Deschler, Martin Uhrig,

Gregor Studer, Franz Muller, Alois Berg,

Conrad Studer, August Brandle,

Philipp Emrich, Louis Eckert, and Jacob

Jacob. The latter was said to have

been the oldest member.15 The society

practiced in the Bader Hotel, in the

Catholic school, the Emrich home, and

later in its own hall on the second

floor of the Wissler Building at the

corner of Paint and Water Streets. In

1858 a Dr. Fuchs founded a second

singing society named Teutonia. He

thereby divided talent and caused both

choruses to collapse. One year

later, however, Ferdinand Tritscheller,

the druggist, former Munich student

and 1848 expellee, issued a call with

Stanislaus Burkley in the German

newspaper Wochenblatt for

singers. After its rebirth, the Eintracht con-

tinued uninterrupted far into the

twentieth century; and, like many a

German singing group, well beyond the

time when all singers knew the

meanings of the German verses. Burkley

served as director until 1882, when

216 OHIO HISTORY

Albert Tritscheller, son of the

co-founder, succeeded him. Programs of the

society's productions included numbers

by Strauss, von Weber, Verdi,

Rossini, others less well-known, and

many folk songs.

The Sangerfest (competitive

singing of various clubs) was always a special

event for German-Americans. Almost

imperceptibly, the festival--as was

true for the Eintracht--seemed to

satisfy a longing to be back home. Song

to the German was somehow a legacy that

could sweep across the aching

miles into the cool landscapes or the

warm hearths of the mother country.

After the Eintracht won a golden

cup for first prize at Wheeling, West

Virginia in 1860, Chillicothe became in

1863 the scene of the second German

song festival of the Central Singing

Society in North America.16 Some

thirty years later, in 1896 the Eintracht

hosted groups from Akron, Canton,

Columbus, Dayton, Lima, Massillon,

Newark, Springfield, Tiffin, and Toledo.

Under the combined direction of Theodore

Schneider of Columbus and

Albert Tritscheller, four concerts were

given and acclaimed as the greatest

in the city's musical history. The president

for that year, F. C. Arbenz,

reported a first in the history of such

festivals, a profit of more than one

thousand dollars instead of the usual

deficit.17

Six years later, in 1902 the Eintracht

celebrated its golden jubilee by

again receiving clubs from the central

Ohio association of German singers

as well as a representative from the

national organization, vice-president

Charles G. Schmidt of Cincinnati. The

festival began on June eighteenth

with singing receptions and gift

presentations as choral groups arrived at

the railroad station. That evening the

combined choruses held a concert

in Memorial Hall. There were speeches,

awards, and celebrations, which

ended with singers and audience

rendering solemnly Die Wacht am Rhein.

On the nineteenth, the townspeople

witnessed a colorful folk festival. The

streets were decorated with German flags

and gay banners as a lengthy

parade wound its way through downtown.

In the weeks leading up to the

fete, the local German paper ran

detailed articles on the singing society,

its history, former and present members.

The jubilee officers included F. C.

Arbenz, Otto Engelsmann, Karl

Weisenberger, C. Albert Fromm, Jacob

Jacob, Georg Hartmeyer, Karl Zweigard,

Otto Dreyer, H. C. Brandle,

Franz Schur, and M. B. Hess.18 On June

10, 1912 the society received a

gold medallion from the German Emperor,

Wilhelm II, who sent it via

the Cincinnati Consulate to the

secretary, Karl Weisenberger.19

Chillicothe's Germans attended

productions of operas and plays in the

mother tongue, but it appears that

acting met with considerably less

enthusiastic support than did their song

festivals. Productions were infrequent

and of unknown quality. The newspaper

promoted attendance but rarely

printed reviews. Theater events were

generally reported, as illustrated below,

without comment:

The theatrical production in Wissler's

Hall on Monday evening was

staged by the dramatic society of St.

George's Knights and was blessed

with so large an audience that many had

to be turned away. The society

plans to give the comedy Das Vetter

vom Lande (The Country Cousin)

THE CHILLICOTHE GERMANS 217

by Christoph Ney on Thursday evening. It

is the best German comedy

that has ever played in this city . . .

John Hess and Joseph Schneider

will also talk about their trip from

Germany to America. Tickets costing

$.25 are available from members of the

German Drama Society.20

An advertisement for Clough's Opera

House urged the public not to miss

an American cantata in four parts along

with four brilliant tableaus presented

by the Free German Evangelical Church.

Clough's Opera House, which

stood where the post office now stands,

was probably used primarily for

productions in English by traveling

theater groups. The German theater

seems never to have made its mark in

Chillicothe.

While religious activity formed the core

of the German community and

while parades, singing, and acting

bolstered its morale, it was the German

press that for emotional reasons and

self preservation maintained the cultural

ties with the land of origin and

promoted activities of the immigrant in

his new home. Generally speaking, the

press in America sought to retain

the mother tongue as long as possible.

Of course, the language was inextri-

cably bound to the vitality and autonomy

of German people abroad and

was an essential requirement if the

German culture were to be preserved

intact. To this end the German press was

more successful than any other

foreign language press in the United

States. It was relatively easy to start

a paper because the editor could always

count on a definite reader constit-

uency, but it was more diffcult, as a

rule, to keep the paper alive.

During their heyday, the journalists who

edited the German papers in

Chillicothe were in a position to

exercise leadership in politics and in the

local affairs that affected German life.

As elsewhere in America, the German

press was often the only contact the

immigrant had with the happenings

of his adopted home. Ironically, the better

the press fulfilled its role, the

quicker the newcomer got acquainted with

his environment. As the German

press integrated the immigrant, it

signed its death warrant. For, once the

new citizen felt one with the community,

it was only a short time until he

also learned the new language. Thus, as

the foreign-language press cushioned

the shock of transition, furnishing

local news, editorials, sentimental fiction

and advertisements, the press slowly

eliminated its clientele.

The German language press of Chillicothe

began in 1849 with the estab-

lishment of Der Ohio Correspondent, edited

by William Raine,21 a member

of the famous journalist family of

Germans in Baltimore.22 Although only

a few issues survive, a few

generalizations about the paper can be made.

It appeared weekly after April 1849,

cost $2.50 per year, measured 16" x 22",

and was printed on "Main Street

near the Episcopal Church." Listed sales

representatives included not only one

each in Waverly, Piketon, Portsmouth,

Lancaster, and Columbus in Ohio, but

also in New York, Philadelphia, and

Nashville. As a result, advertising was

placed by distant businesses, frequently

from Cincinnati.23

In political matters The Correspondent's

position is clouded. Whole pages

were allotted to official affairs: a

reprint of the Ohio constitution,24 treasurer's

reports for the city, election

announcements, reprints in German of laws

218 OHIO HISTORY

passed by the Ohio legislature,25 and

general information which facilitated

the immigrant's life in his new

surroundings. With the 1851 April elections

proximate, an announced meeting of all

German citizens was to be held

in Bader's Hotel to advise the people on

the candidates, but nothing appears

about the German interests or issues

involved.26 Selected reports from

elsewhere in the United States indicate

an antislavery slant, and broad

coverage of news from overseas indicates

interest in foreign affairs.

As was the pattern with other

foreign-language papers, the Ohio Corre-

spondent in 1854 also ceased publication after a short life--of

barely

five years. In the following year,

George Feuchtinger started a paper under

the title Chillicothe Anzeiger. In

1857 Feuchtinger left to publish the Ports-

mouth Correspondent, and Richard Bauer succeeded him, changing the

name to Chillicothe Wochenblatt. Bauer

edited the paper until the Civil

War, when he sold it to a Lieutenant

Burkley, who again changed the

name, this time back to Anzeiger. Bauer

went to Dayton where he again

started a German paper; he later

enlisted in the army and was killed.

Burkley continued the paper in

Chillicothe from 1861 until 1864, when

he sold out to a man named Niesen. This

paper lived only a short time,

passing from Niesen to Arnold, thence to

Heinsinger and Masacus, its

last owners. Chillicothe was without a

German paper until the advent of

Unsere Zeit (Our Era) in 1868.27

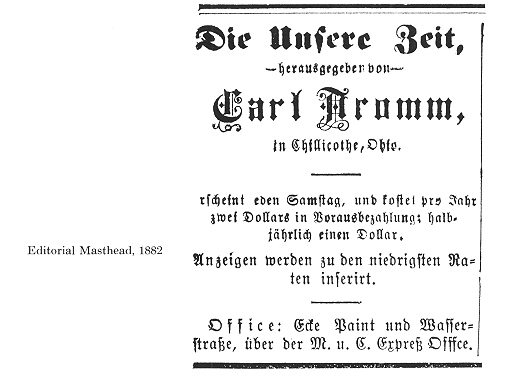

Certainly the most significant cultural

and political force within the

German community of Chillicothe was the

newspaper, Unsere Zeit. Published

weekly for nearly fifty years, the

partially complete files span the period

from 1868 to 1917.28 The paper was

edited and printed throughout by

the Fromm family, whose ancestors

emigrated from Meiningen, Thuringia

in 1851 and located briefly in

Miamisburg before settling in Cincinnati.29

The founding father, Johann Balthasar

Fromm, was born in 1818. Having

taken part in the 1848 revolutions, he

was forced to leave Europe. In

America he was known and befriended by

co-workers, Carl Schurz and

Franz Sigel.30 The Fromms started Unsere

Zeit at Portsmouth in 1868,

but when a delegation of Germans from

Chillicothe persuaded Balthasar

Fromm and son Charles Johann to move the

paper, they responded by

bringing their own presses via the canal

to Chillicothe. After Balthasar's

death in 1893, Charles Johann, former

apprentice to the Cincinnati Volks-

blatt, and his son Charles Albert continued the work until

Charles Johann

died in 1896.31 Charles Albert phased

into commercial printing when the

German language vanished from

Chillicothe life in 1917, and continued

the business until his death

thirty-eight years later.32

In contrast to some German papers in

America, Unsere Zeit was skillfully

laid out with adequate captions and

well-organized advertising blocks. In

its earlier years it included only four

pages, 26" x 20", but grew to eight

after the turn of the century when the

page size shrank to 20" x 18", then

to 14" x 22". In regard to the

paper's political leanings, it was Republican

at first,33 but supported

Tilden in 1867.34 Generally the journal was inde-

pendent except on issues particularly

affecting Germans. This weekly paper,

|

THE CHILLICOTHE GERMANS 219 |

|

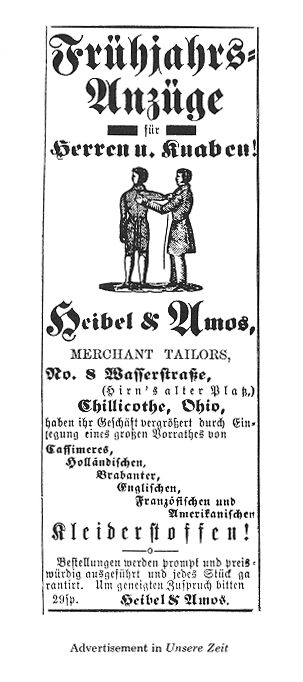

with a circulation of from 1000 to 1100 per year, had an annual subscription rate of $2.00.35 Like its English language rivals, no issue came off the press without its continuing serial novel. There was a section for local news and current gossip, another for news from Ohio, usually with comments about progress in the state legislature, and another for general news from the nation. After telegraph press services were developed, news from Europe, especially Germany, increased, though local items were still stressed. Editorials were inconspicuously placed in a narrow column on the second or third page; and, while expressing strong opinions on local and national events, they supported laudable German traditions without ever promoting German imperial policies. The German press of Chillicothe was solidly loyal to the United States, before as well as during the World War I years. To a significant extent Unsere Zeit buttressed its existence through adver- tising. Week after week we find the scrolled blocks promoting Schachne's Department Store, Wissler's Brewery, Vanmeter and Reid's Clothing Store, Jacob Knecht's Scioto Brewery, Wiedler and Klaus' Clothing Shop, Stocklin and Herrnstein's Hardware, Sulzer's Grocery, Neuman's Bazaar, and the many other shopkeepers and professional men who courted the German customer. The weekly German newspaper was apparently not a strong enough force in the preservation of the Chillicothe-German entity to satisfy some |

220 OHIO HISTORY

immigrants. Hoping to illuminate the

past in order to sustain national

German identity in the present,

Balthasar Fromm, Stanislaus Burkley, and

Martin Schilder established a Pionierverein

(Pioneer Club) in 1882. Assum-

ing that this club would become the

magic panacea, the leaders stated their

objectives in the first booklet:

"We will record and compile the historical

contribution of German immigrants in

Chillicothe and Ross County. The

club has no other special interests, be

they political, religious or social in

nature. It encompasses the entire German

community and ought to form

a unifying principle among us."36

The members of the club, however, were

never able to find sufficient material

to fill a monthly pamphlet of thirty

pages with pure historical material or

to engage in adequate historical discus-

sion at the monthly meetings. As time

passed the Pionierverein became

more and more a social group, but the

leaders tried to keep it true to its

stated objectives. In a speech at one of

their picnics, Balthasar Fromm

reminded the club members of their

purpose:

We must tell our children that the

German people, the very mention

of whose name elicits respect from all

and fright from their enemies,

have contributed enormously to culture,

civilization and freedom in

America. We have not left our

comfortable land to receive alms here,

but to assist in building the temple of

freedom and to prepare for our

children a home where they can truly

belong.37

In the same speech Fromm pointed out the

victory of "Germanism over

Puritanism" in America, citing as

evidence the acceptability of German

customs, festivals, music, and

especially the moderate use of alchoholic

beverages. One ideal still to be

realized was the fusion of "the best of the

German character and customs with the

best of native American traditions."

Although schools, bourgeois outlook,

honesty, and perseverance had been

integrating forces, the means of

continuing the fusion would be by "keeping

the German language in the schools along

with English, for it is an absolute

truth that no one learns a language

without also learning the character,

customs and habits of the people who

speak it."38

The question of temperance, as the issue

was perennially presented in

the United States, resulted in a

vigorous negative reaction in the German

communities. Acting as the German

spokesman in Chillicothe, The Corre-

spondent vented its feelings with a casual entry:

Gough, former New York drunkard, now

employed by the temperance

leaders, arrived here safely last

Tuesday. On his arrival, enthusiasm

was such that nowhere would ten men

gather on the street to hear, or

cheer this poor sinner. The signal for

his arrival was the explosion of

a barrel of beer in a grocery store, no

doubt because it had developed

too much pressure waiting for the

thirsty new-comer.39

More than thirty years later,

Chillicothe's native son, Joseph Smith, of the

Ohio State University was visiting

lecturer at the University of Leipzig and

wrote to the editor of Unsere Zeit explaining:

It is impossible for Germans to

comprehend the nature of the tem-

perance movement. In America many drink

and many do not, yet

the country is scourged by drunkenness.

In Germany everyone drinks

and drunkenness is rare. In America the

demon of alchohol rules,

|

|

|

and life becomes its victim. In Germany, where more beer is consumed than water, few drink to excess. The traveling American fresh from the enthusiastic crusades, Murphy-pledges and striving for the salvation of mankind is pleasantly overwhelmed in a country where wholesale missionary work would be suddenly deflated by the German adjective massig, moderate.40 |

222 OHIO HISTORY

The editor capitalized on this public

letter by stressing his personal friend-

ship with Smith and by pointing out

Smith's respected position as professor

of Latin. Hopefully, the letter would

blunt the criticism of the local

temperance fanatics.

In the course of its history, temperance

agitation helped align the

Chillicothe Germans behind the political

party which opposed restrictive

laws on beverages. With hardly an

exception, the German press kept

hitting the "dry" front by

including in its rationale the whole concept of

personal freedom. Involvement of the

Republican Party with temperance

drew sharp fire from editor Fromm in

1882:

We must rise up to cast off the

Republican claims, for it is as clear

as gold that the brood nest of the

puritanical bigots and temperance

enthusiasts is to be found in the

Republican Party. Occasionally one

finds a temperance stray in the

Democratic Party too, but where is

the herd that does not have one mangy

sheep?41

In another article readers were urged to

vote Democratic in the forthcoming

April, 1882 elections in Ohio:

If the votes in the bigger cities favor

the Republicans, then the legis-

lature will pass laws of temperance

before adjournment. If the cities

go Democratic, however, the

representatives of rural areas will think

twice before they vote for temperance.

Go to the polls on the first

Monday in April. If we get the best of

the Republicans this time, it will

be difficult for them ever to regain

what they have lost.42

Sunday closing was an aspect of the

larger temperance movement. At

the temperance convention in Columbus on

March 23, 1882, delegates

were ordered to demand passage of the

Smith Bill, then pending before

the legislature. It proposed closing on

Sunday all places where liquor was

sold. Chillicothe's mayor, Richard

Smith, arranged for a twenty-minute

recess in the Ohio Senate while

temperance delegates cornered senators

to urge the bill's passage. During the

break, as reported in Chillicothe's

German paper, "the comedy reached

its peak when the Reverend Paine,

president of the Delaware Methodist

College, mounted the vice-governor's

platform to preach to senators about their

duty regarding the bill. He

did not merely request, he demanded they

pass the bill."43

Fromm's weekly humor column of dialogue

in Saxon dialect sharply

mocked temperance and Sunday closing

enthusiasts. As late as 1917,

editorials continued to assail

prohibition and any party which supported

it. While they generally favored

Democratic candidates in state and national

elections, such editorials recommended

consideration of individuals for

local and county positions, offering to

print any respectable opinion in

favor of any candidate. In one sense,

this bipartisan attitude was necessary

for the paper's life, namely, because

the state was indirectly subsidizing the

German press by paying for printing

court announcements, auditor's reports,

tax lists, and official documents in the

German as well as in the English press

Perhaps some opposition to temperance

proposals and political allies of

temperance stemmed from economic

grounds. It is said that winegrowing

along the banks of the Scioto was

extensive. Although not specific, the

1850 census shows that a large number of

Germans listed their occupations

|

|

|

as gardeners.44 Senior citizens of the city maintain that many of these persons grew grapes for wine. Several wineries flourished, perhaps best known of which was one once owned by the 1848 emigrant, Dr. Xavier Faller. The mansion and overgrown vineyards can still be seen on the western bluff overlooking the city.45 Of course, the two prosperous German-owned breweries and numerous taverns that held late hours would be adversely affected if the temperance movement were successful. No mention of German business engagements would be complete without a note on the production of automobiles in Chillicothe between the years 1910 and 1917. Pioneer and founder of one operation was F. C. Arbenz, already mentioned for his role with the singing society. To capitalize on the respected Mercedes-Benz firm in Germany the automobile bore the name- plate "arBenz." Charles Albert Fromm, Sr., last editor of the Unsere Zeit, |

224 OHIO HISTORY

purchased a car in 1911 and a second in

1917. Not one of the models is

known to exist today.46

While the question of temperance,

politics, and at times religious differ-

ences tended to create friction between

German groups and their English

counterparts, the financial demands of

business seem to have been integrat-

ing forces. In general, rapport between

the English and German-speaking

communities remained quite stable. Once,

in 1838, the English press reported

a murder and commented that the city

might have been up in arms, except

that it happened to be one German that

killed another German. The

language barrier and varying customs may

have produced, to some extent,

a gulf between the two nationalities.

But gradually integration took place,

and with time the cleavage disappeared.

No where is there evidence of open

hostilities between German and

Yankee townspeople. In fact, an article

in 1882 on the early Germans in

Chillicothe lauds the harmonious

relationship that existed between them

and the natives, while lamenting that

there was far less harmony among

the Germans themselves. The German

editor appended his own comment:

"In these last two lines lies a

bitter truth. For this reason I have started

the German pioneer club, namely, that

the Germans of Ross County may

unite under one banner and thereby earn

more respect from Anglo-Americans.

We cannot now tolerate religious or

political hair splitting."47 His words

strengthen the letter of an unfriendly

critic writing from Gottingen who

remarked that whenever three Germans

congregated in the United States,

one opened a saloon so that the other

two might have a place to argue.

Discord was perhaps inevitable in a

group united only by national back-

ground and a common language that was

slowly weakening. First and second

generation Germans learned German in

early years, then often attended

school where only English was used. Yet

at one time the demand was so

great that two of the public schools in

Chillicothe used German in instruc-

tion and, of course, taught the language

as a subject. This was not unusual

in Ohio, for in March 1840 the state

passed a law permitting not only the

teaching of German in the public

schools, but teaching in German as well,

whenever there was sufficient demand for

it. Local school boards could

retain the language in the curriculum as

long as they wished, and the sug-

gested guideline for doing so was

enrollment of forty or more pupils desiring

instruction in German.48

The practice of teaching in German

apparently came under pressure in

later years, prompting German editorials

in defense. Editor Fromm chided

the Germans for neglecting their

language:

Minimizing our mother tongue, of which

many Germans are guilty,

is due to a lack of education and lack

of national pride. National

consciousness must be strengthened.

Cutting off our traditions smacks

of treason. That man is a traitor to the

spirit of the German Father-

land who bans the German mother tongue

from his own household and

the man who apes the language of his

environment has killed German

culture. That man is a traitor to the

spirit of the German people

who does not teach his children a holy

and lofty enthusiasm for the

German homeland and German principles.49

THE CHILLICOTHE GERMANS 225

But in spite of efforts to the contrary,

the use of the German language

steadily declined. Lingering for years,

it was not until World War I that its

use was discontinued when Ohio passed a

law denying the right to conduct

schools in any foreign language.

Only after the beginning of World War I

is there evidence that the

German newspaper was, after all, German,

even if its editors proved it in

an atypical way. Some thirteen years

before the World War, the German

press attacked England for its role in

the Boer War,50 advertised for sale

pictures of Bismarck, and reported in

detail on the travels and meanderings

of Kaiser Wilhelm II. But once World War

I began, the German press,

in general, goaded by British

propaganda, often struck back in self-defense.51

The Fromm press, however, refused to be

baited. It actively exhibited its

American patriotism by helping to sell

liberty bonds, exhorting first for

neutralism when national sentiment

originally supported that policy; later

staunchly upholding the Allies when

American entrance into the conflict

called for that. As if waging a war for

its own survival, the paper printed

American flags on the front page of each

issue, composed and printed

patriotic poems about the American flag,

and generally reflected an image

of American patriotism.

The war was the proximate cause of death

of the paper and of the German

language in Chillicothe. The remote

cause was cultural assimilation, some-

thing that began as soon as immigrants

had dealings with natives. The

symbolic end of the use of the German

language in Chillicothe came on

October 19, 1917, when the last issue of

Unsere Zeit rolled off the press

with the following front page editorial.

With today's number, Unsere Zeit ceases

publication until further

notice. Since the war began in this

country, there has been every

imaginable public and private protest

against the German press. Since

passage two weeks ago of a law which

goes into effect on Friday and

requires that all articles concerning

the war must also be translated

and printed in English (a task which

would be very inconvenient and

costly) we have decided to desist

publishing Unsere Zeit until further

notice.52 Unsere Zeit has

worked for the German element here for years,

but now finds it impossible to continue.

It is hoped that peace will

soon return and if the Germans here

should again be interested in a

local paper, we would be happy to

publish it again. Until further notice,

we will dedicate ourselves completely to

job-printing.53

Eventually peace did return, but,

meanwhile, the process of assimilation

had progressed too far for an eventual

revival of the active use of German.

Today, a remarkable number of names of

that nationality appear in the

phone book of Chillicothe, but nothing

is German any more. World War I

brought only the final coup de grace,

and ended abruptly what would have

otherwise lingered for perhaps a decade

or two longer.

THE AUTHOR: La Vern J. Rippley is

Associate Professor of German and Chair-

man of the German Department at St.

Olaf College.

|

The Chillicothe Germans

by LA VERN J. RIPPLEY

For nearly a century an element of German culture could be observed in the community life of Chillicothe, Ohio. Until World War I brought an abrupt end to the general use of their language, the Germans developed their own churches, schools, publications, cultural societies, and special activities on a scale comparable with other Ohio localities. Now, however, half a century later, the Chillicothe Germans as an ethnic group are little more than a dim memory. Reliable information concerning the earliest German immigration to Chillicothe is scanty.1 By the 1830's the first substantial migration to the United States began; by 1840 the German immigrant group comprised perhaps ten percent or more of the total population of Chillicothe; and by 1850, following the greatly increased migration of the second half of the 1840's, it constituted nearly a third of the population. In the ensuing two decades, it became even larger than a third. By 1880, however, the relative number of Germans began to diminish as the later settlers were

NOTES ARE ON PAGES 270-273 |

(614) 297-2300