Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

|

NOTES ON THE ANTE-BELLUM CATTLE INDUSTRY FROM THE McNEILL FAMILY PAPERS

by JOHN EDMUND STEALEY III

The long-ignored story of the pre-Civil War cattle industry in Ohio has been the subject in recent years of several scholarly studies which have enhanced the meager bibliography of American agricultural history. Previously only a few major works dealt with the beef trade on a general, national basis. The most notable of these are James Westfall Thompson's History of Livestock Raising in the United States, 1607-1860 and Charles Townsend Leavitt's original research in his 1931 University of Chicago dissertation "The Meat and Dairy Livestock Industry, 1819-1860."1 Ohio's role in the production and marketing of meat animals, however, won deserved recognition in Paul C. Henlein's description of cattle driving from Ohio in a 1954 Agricultural History publication as well as in his important monograph, Cattle Kingdom in the Ohio Valley, 1783-1860,2 and in the specialized articles by Robert Leslie Jones in the Ohio Historical Quarterly in 1955.3 The paucity of manuscript material, almost non-existent on many phases of the ante-bellum industry in Ohio and in the nation, has hindered research by agricultural historians. Henlein's use of previously unexamined manu-

NOTES ARE ON PAGES 70-72 |

NOTES ON ANTE-BELLUM CATTLE INDUSTRY 39

scripts, in the hands of generous

individuals and in public depositories, is

the enriching characteristic of his

monograph.

In addition to the manuscripts mentioned

above, the fragmentary though

important McNeill family papers in the

West Virginia University Library4

augment the scant supply of primary

material on the ante-bellum cattle trade

in both the Scioto River Valley of Ohio

and in the South Branch River

Valley of Virginia. The most important

feature of the latter collection is

that it contains several colorful and

informative letters written by various

members of the Renick family who

migrated from the South Branch to the

Scioto Valley and achieved enduring fame

as cattlemen.

Like many eighteenth century settlers on

the South Branch and in other

fertile river valleys in western

Virginia, the Renicks had originally migrated

from Germany to eastern Pennsylvania for

religious reasons. After a brief

stay in Pennsylvania, they traveled

southwest into the lush river valleys

through which flowed the southern

tributaries of the Potomac River: the

Shenandoah, the Cacapon, the South

Branch, and Patterson Creek. Two

Renick brothers settled on a part of the

Fairfax Grant known as the South

Branch Manor which was owned by Lord

Fairfax (and later John Marshall).

Here, one of them, William, became a

deputy surveyor for Fairfax.5 Among

their neighbors on the Fairfax estate at

Fort Pleasant on Indian Old Fields

was the McNeill family, which had

emigrated in 1722 from Scotland or

Northern Ireland.6 During the

course of three generations these two families

became inter-related by ties of

friendship, business, and marriage.

Even before 1800, cattle raising and

feeding in the South Branch Valley

evolved from a subsistence type of

operation, supplying local needs and

frontier forts, into an established

industry, marketing its product in eastern

cities. On the fertile soil, the

settlers raised large quantities of corn, which

they used for food for themselves and

their livestock. Additional food for

the animals was readily available in the

hilly regions surrounding the South

Branch, which were difficult to

cultivate but which made ideal pasture land

for cattle.7 The McNeills,

the Renicks, and other stockmen drove their

cattle either to the markets in the

newer towns of Winchester and Staunton

or to the older and more populous

cities, such as Richmond, Alexandria,

Georgetown, Baltimore, and Philadelphia.

At the beginning of the nineteenth

century, the feeders of the South Branch

Valley were attracting stock cattle from

other areas of Virginia and as far

away as Kentucky and eastern Ohio.8

Between 1800 and 1860, there may

have been a Scioto River Valley to South

Branch cattle trade, but adequate

documentation of its existence is

lacking.9 It would have been practical to

drive stock cattle or even corn-fed

cattle (when unfavorable market conditions

prevailed in eastern cities) from the

western regions up the South Branch

or other river valleys from the National

Road, because of the trellis drainage

pattern in this section.

The contributions of the settlers from

the South Branch Valley to the

catttle industry in the Scioto Valley

and other parts of the West have been

recognized by all historians in the field. The migrants

carried their practical

|

40 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

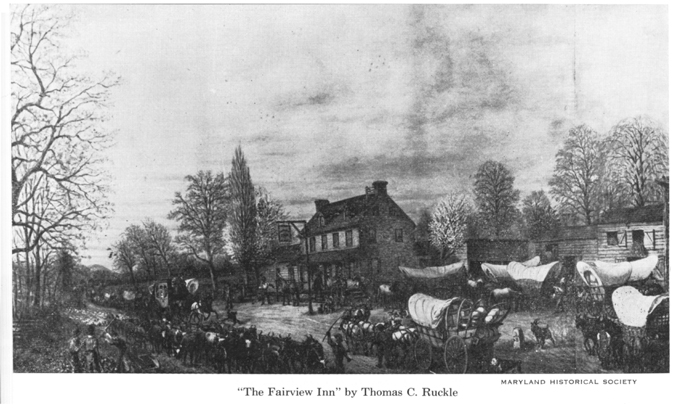

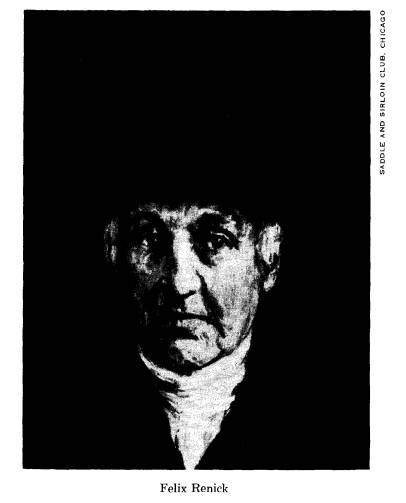

knowledge and experience in stock raising to the extensive corn growing lands of the Scioto. The most important and unique technique transferred was the South Branch method of cattle feeding. When corn was harvested, it was cut and shocked in the open field with 12 to 16 hills per shock. From November to early spring, this shocked corn was hauled from the field in a low wagon and fed to the cattle to be fattened in an eight to ten acre feed lot. These animals were followed into the lot by hogs or stock cattle. All livestock remained unsheltered throughout the winter.10 Lord Dunmore's War had afforded many Virginians an opportunity to explore and view the rich, gently rolling lands in the Scioto Valley. Accounts of the fertility of the land on the Scioto were carried back to the South Branch by Daniel McNeill, Sr., James Parsons, and other men who had been at Camp Charlotte, Dunmore's encampment in what is now Salt Creek Township, Pickaway County. Spurred by these favorable reports, Felix |

NOTES ON ANTE-BELLUM CATTLE INDUSTRY 41

Renick, the son of Fairfax's surveyor,

yearned to explore this same region

for himself. Therefore, in October 1798,

Felix, Joseph Harness, and Leonard

Stump traveled westward to view this new

country. Their explorations con-

firmed the findings of Dunmore's

farmer-soldiers. In 1801 Felix, his wife,

and small child, moved with Jonathan

Renick and two hired hands by

packhorse to Darby Creek in the Scioto Valley

to raise a crop of corn on

lands jointly owned by Jonathan and

Thomas Renick. Later in the spring

Felix, also, was able to purchase, at a

government auction in Chillicothe, a

large tract of land for $2.50 an acre

located at the mouth of Indian Creek

on High Bank Prairie in Liberty Township

in Ross County.11

Within a few years, many other families

left the South Branch for the

more extensive virgin lands on the

Scioto. Among these were Felix Renick's

older brothers, George and William. Left

behind in the South Branch Valley,

which Felix later described as

"small in extent compared with many of

those in the west, yet in beauty and

fertility . . . not surpassed by any,"12

were their relatives and business

associates, the McNeills. Daniel McNeill, Jr.,

had married Margaret (Peggy), a sister

of the Renick brothers. Daniel's

brother, Strawder (Strother), had

married another sister, Mary Ann

Renick.13 The separation of the two

families, however, did not prevent

them from maintaining close friendships

and business ties.

By 1820 the Renicks were the undisputed

leaders in the cattle business

in the Scioto Valley. George Renick was

the first man to drive corn-fattened

cattle from the Scioto in 1805 over the

Alleghany Mountains to an eastern

market.14 Both Felix and George drove

cattle to the East intermittently

in succeeding years. All the brothers,

including William, explored surround-

ing states and regions as far west as

Missouri for cattle and land prospects,

and they brought stock cattle from

Kentucky and other western states into

the Scioto Valley to be fattened.15

In the winter of 1818-19, Felix Renick

sold to a victualer in Chillicothe

one of his seven-year-old steers which

weighed a total of 2,511 pounds

when slaughtered. Also dressed at the

same time was a William Renick

heifer which weighed 1,574 pounds.16

On November 3, 1819, a livestock

show was held in connection with the

first annual meeting of the Scioto

Agricultural Society in Chillicothe. The

Renick family won all the first

place premiums with their horses and

cattle. George Renick won a silver

cup for the best gelding in the show and

took another for the best steer,

"the fattest ever seen in this

country." Felix Renick was awarded a silver

cup for the best cow in competition with

the animals of his brother, George,

and his cousin, Jonathan Renick of

Pickaway County. William Renick of

Pickaway exhibited the best heifer under

two years old. For the gratification

of the spectators only, and not the

prize, William, George, and Felix showed

their jointly owned long horn bull, Duke

of Orange.17 In the expanded

second annual show of the society in

1820, the Renicks again won all the

silver cups awarded for cattle. In

addition, William Renick had the third

best hog and Mrs. Felix Renick exhibited

the best 20 yards of flax linen in

the handicrafts division.18

|

42 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

As had been mentioned, the Renicks maintained close connections with the Daniel McNeill family and other former neighbors in the South Branch Valley. They corresponded regularly and their families exchanged frequent visits.19 On their return westward from marketing trips to eastern cattle yards, the Renicks usually would stop at "the Branch." They constantly kept each other abreast of market developments and news. Daniel McNeill would receive letters on the condition of markets from anyone traveling from his neighborhood to the eastern cities and then would relay it on west to the Renicks. The information furnished by James Parsons, Jr., on the state of the markets in February of 1823 is typical;20 According to promise I inform you that the markets are about the same that they were -- when I was here [Philadelphia] last year at this time -- cattle are a rating from $5. to $6.50 and a few choise cattle at $7.00 per hundred they new York market Zell tells me is not any better |

NOTES ON ANTE-BELLUM CATTLE INDUSTRY 43

yet. -- this market from information has

veryied very little for a bout

a month past I think it will get better

in a few weeks they people are

a puting off their cattle here fast for

fear of the western stock. Seymour

& Hutton sold out on two market days

all to four they sold none higher

than $6.25 per hundred I am informed

that they were very indifferent

and sold them well according to the

stock and I believe that they sold

none under $5.00 per hundred or very

few.

At one time, Daniel McNeill even had the

state legislator of his county

reporting on the Richmond markets.21

McNeill also wrote to the various

stockyards and their agents in eastern

cities for information. Julia A. Carr,

writing for her father, reported the

prospective prices of the 1820 New

York market in a letter written February

18:

I received yours of the 8th inst.

respecting the price of Cattle in

our market . . . The very first rate

Cattle is worth from 8 to 9 Dollars

per hundred & we have a good supply

at present, but I am of opinion that

Cattle wont be much higher, except some

very prime lots. I will give

you notice as the markets alter. If you

intend coming to New York;

dont let it be too late in the Spring if

your Cattle are large & heavy;

& bring nothing but the first rate

Cattle; for thin Cattle wont do to

come that distance.

In a letter of June 20, 1820, William

Spears notified McNeill that the sum-

mer livestock market in Baltimore was

very slow because of the butchers'

attitude:

Messers Rennick, Campbell and Foley are

all the Drovers we have

here at present I do not here of any

more a coming. the above mentioned

Gentlemen are all from the State of

Ohio. I believe the prices they are

selling at are from $7.00 to 7.50 p

hundred it appears that the Butchers

are determined not to bid up the price .

. . If any thing should take place

respecting the market I wil not fail of

leting you know of it.

In this way, besides using the business

information for his own benefit,

McNeill would keep the cattle-feeding

Renicks of Ohio informed of market

trends on a regular basis. In turn, the

Renicks would predict the number

and approximate departure date of herds

of cattle being driven from their

locality to the East. This knowledge

enabled McNeill to drive his own

cattle from the South Branch to the

eastern cities "at the head of the

market" before the western stock

arrived. These estimates of the Renicks

on the number of cattle being fed in

Ohio in the 1820's also furnish some

heretofore unknown information from

qualified sources.22

On the other hand, Daniel McNeill's

cattle feeding business was on a

much smaller scale than his

brothers-in-law's in the Scioto Valley. In the

fall, he would buy small lots of stock

cattle in outlying areas around the South

Branch and would drive them to his

fertile corn-growing farm, Willow Wall,

where some would be fattened on fodder

throughout the winter. In the

following spring, he would either sell

the finished cattle to dealers who visited

Willow Wall or he would drive them to

eastern markets himself, depending

on the price offered. In the autumn of

1820, for example, McNeill bought a

total of 78 head of stock cattle in odd

lots ranging from one to 40 from

eight individual raisers on the North

Branch at an average price of $16.79

per head. In the spring of 1821, he

drove 30 animals to Baltimore where he

44 OHIO HISTORY

sold them for $36.50 each. After

deducting $51.05 for the expense of driving

and $503.70 for their original cost,

McNeill cleared $530.25 on this small

drove. He kept the remaining cattle to

fatten through the next winter and

sold them in the spring in two lots at

his farm on the South Branch. He

sold a small lot of four for $94.00. The

second lot of 40 head was sold for

an average price of $41.20 apiece. He

thus realized a total profit of $976.40,

after deducting the original cost. The

four animals not accounted for may

have died or may have been retained by

McNeill. Even so, he was able to

clear $1533.49 on 78 head of cattle

within one and one-half years on an

original investment of $1310.00 (not

including the cost of the grain fed to

the cattle and other incidentals).23 And

McNeill was a small operator in

comparison with the Renicks and other

Scioto Valley feeders.24

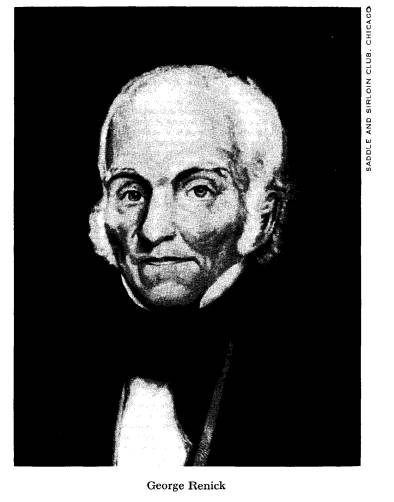

George Renick, on the other hand,

combined his farming with mercantile

interests. Previous to his removal to

Chillicothe in 1802, he had operated a

general store in Moorefield, Virginia.

In preparation for his migration to

the Scioto, he married Dorothy Harness

and purchased a large stock of dry

goods in Baltimore. With the

merchandise, he established a store in Chilli-

cothe. Also, he raised cattle, hogs, and

horses for additional profit and pleasure.

After he proved that it was feasible to

drive corn-fed cattle from the Scioto

Valley to eastern markets, George used

his cattle driving trips for a two-fold

purpose. He would sell his cattle, and,

with the money received, would

purchase supplies to be carried back to

his store in Chillicothe. By 1808,

George had accumulated enough money and

real estate so that he was able

to give up merchandizing and devote all

of his time to his first love -- cattle

raising. During the next half-century,

except for a brief period in 1816, when

he moved to Kentucky for health reasons,25

he was as successful in cattle

and farming operations as he had been in

his store.

Expecting to drive a herd eastward in

the summer of 1820, George Renick

wrote his brother-in-law, Daniel

McNeill, in February asking him "Pleas to

Write me again on the prosspects of

markets" and forecasting that "150 head

of good Cattle will be the Extent that

will go from this Country to an Eastern

Market this season." He said about

ninety head of fat cattle were destined

shortly to go by boat for New Orleans,

including his own "large Stear (which

you probably have heard some talk of)."26

Western commerce, he reported,

"has again rivived" with fifty

boatloads of produce passing down the river

within a few mid-winter days.

Advice of the experienced McNeill was

also sought in November 1820

by Jonathan G. Harness on buying and

driving hogs to an eastern market.

Jonathan had moved from the South Branch

to the Scioto where his uncle

Joseph Harness and other relatives had

lived since 1798.27 He chided McNeill

for not having mentioned "the State

of the Market" in a recent letter and

reported that the asking price of pork

was two dollars without takers "and

I think their will be no Dificulty in

bueing at one Dollar and Seventy five

cents."

Market appraising began early for

William Renick, the son of George [not

to be confused with his uncle William], who began to

assume responsibilities

in his father's cattle business at the

age of 17. He traveled throughout Ohio

NOTES ON ANTE-BELLUM CATTLE

INDUSTRY 45

and Kentucky buying stock cattle28 and helped on

drives to eastern markets.

In Baltimore in May 1821 he duly

reported to his uncle Daniel "how times

are and how they are like to be."

He found beef selling between $5 and $6.50

"per Cwt.," said he had

disposed of some of $6.25 but still had twenty head

on hand, and estimated about 150 in the

market with cattle arriving

daily. He concluded his letter by saying,

"I hav only to relate that the seasons

are very backward here, there is hardly

any grass about here that is sufficient

to keep cattle but we have fine weather

for it to grow now."

Two letters of William Renick to McNeill

reflect the continual attention

given by the Renick brothers to the

general business climate. Less is known

about the contributions of William to

the cattle industry than about those

of his more renowned brothers. He

settled in Bloomfield, Pickaway County,

where he raised prize-winning cattle. He

had moved briefly to Missouri after

he explored the area with Felix in 1819,

but came back to the Scioto.29 In

March 1822 he reported on the river

traffic: "the boats were going yesterday

and today in great stile I suppose there

is something Like Fifty thousand

Barrels of flower pork beef and whiskey

on the Scioto River now on its way

to Market or Destruction," and in

January 1824 he commented on crop and

livestock prospects for the year:

There is a great part of our Contary

that have Raisd little or no Crops

of any Kind this Season but a Long the

warter Courrces ther has been

tollerable Crops of Corn but Lite Crops

of wheat but it appears to make

but Little Difference wheather they have

Crops or not they will have

stock . . . I found that there would be

but a few hogz here this Season

owing to the great quantity that died

Last winter . . . the quantity that

is going on to Market from a thousand to

three thousand in a Drove [.]

Henry Vanmeter passed threw Columbus a

week or two ago with 26

hundred in one drove . . .

We are feading as many Cattle in this

County as we did Last year

by one half but in Ross I suppose there

is about the Same number.

Felix Renick gives us additional

information about prospective market condi-

tions in the Scioto Valley. Early spring

of 1823, braving winter travel hard-

ships, he scouted the entire Valley

collecting information on the number of

cattle destined for the eastern market.

In his correspondence with McNeill,

Felix reviewed the growth of the cattle

industry in the West since the time

of his migration from the South Branch,

commenting wryly on Yankee

enterprise and voicing some prophesies

about the impact of western agricul-

ture on the economy of the eastern

United States. From "Cattail Pararie" on

February 24, 1823 he told his

brother-in-law that eight or ten New York

and Pennsylvania drovers had been buying

"more than half of the Cattle

in the County" at an average of $4

a hundredweight, some drives already had

started for the East with others likely

until "the first of August, & perhaps

the whole year." The animals were

being shod30 to enable them to travel the

long miles of frost-bound or thawing

roads, and he expressed the belief that

within five years winter cattle driving,

once regarded as "out of the question,"

would be common due to "yanky

vigilence and interprise." He continued:

The rise and progress of the west has

excited considerable alarm in

Some Sections of the east, and they have

already began to feel Some

of the effects. -- but rest assured you

feel nothing yet. -- we must

46 OHIO HISTORY

Measurably Judge things to come, by

things that has past, my present

knowledge of the vast extent and

fertility of the Soile of the west

induces me to blieve, that if we have no

uncommon rupture, in the

United States or Urope, that in twenty

years from this time, provisions

of all kinds will be reduced to one half

of their present Value, and that

before that day fat Cattle will be

driven to the eastern Markets even

from the Mississippi & Missouri.

A short time later, after consulting

with his brothers, George and William,

Felix again wrote McNeill on March 15,

1823 that five thousand head of Ohio

cattle would go East, some recently

purchased at from $4.50 to $5. More

than seven hundred had started, others

were passing through from Kentucky

and he questioned the consequences of

"their Crouding off in this manner"

fearful "it would be almost fatal

to the Markets and of Course to the drovers,

unless a Northern Market Should open

which I fear will not be the case this

Season."

The quantity of river-borne produce

alarmed Felix because of its effect on

business in the South and West.

"Our little river", he wrote, "has for two

or three days past been literally

covered with crafts conveying off produce

property, & articles of every kind

& denomination, that you could possibly

think of, and many that you nor no other

person, except a yankey, would

think of takeing to Market . . . our

ears are now continually greeted with

the Musical Sound of the boatmans horn,

boats have been passing for two

days & a half . . . at the rate of

about thirty pr. day . . . I think there will

Something like three hundred float out

of the Scioto this year . . ." His son,

George,31 he said, was off with a boatload

of English cattle to be delivered

at Portsmouth, at the mouth of the

Scioto.

By 1826, age and infirmities hindered

Daniel McNeill's personal, active

participation in the cattle business.

Daniel R. McNeill then assumed his

father's responsibilities for

purchasing, driving and marketing, but the elder

McNeill remained his adviser and

consultant, keeping himself informed of

market trends and forecasts. The son

reported to his parent from Baltimore

on March 25, 1826 that he had

"arived here in considerable croude yesterday.

I have had scarcely a butcher to see me

much less to bye any . . . I have

concluded to move the cattle on to

Philadelphia to day . . . If I can sell to

the drovers to any advantage I will do

so."

In his turn, the father furnished the

son with information on business

activity in the South Branch when the

latter was in eastern cities with a

drove.32 In the spring of

1829 he was able to relay additional intelligence

from his nephew, Strawder McNeill, who

had journeyed from Frankfort, Ohio

to the South Branch, in part over the

National Road.33 After a warning

from "Papa" not to sell any

cattle to a certain Rusk who "will keep you

waiting for your money so long and then

not get it," young McNeill told

of two South Branch droves destined for

Richmond and added:

Cousin Strawder34 says he

only saw three droves of Cattle on the road

as they came in & thez small droves,

the largest drove was 80, another

60, & one 40 one they passed at

Zanesville one just the other side of

the Ohio River, the other at Laurel

Hill, and says the road was so verry

bad they could scarcely get along, one

set had traveled 40 miles in 10 days.

NOTES ON ANTE-BELLUM CATTLE INDUSTRY 47

Daniel R. McNeill was in Washington in

the spring of 1830 when his sister,

Catherine, kept him appraised of the

active cattle trade in Hardy and Hamp-

shire Counties. This letter35 reveals

that a few South Branch cattle traders

had been going to Ohio to purchase

cattle to drive to market, but had found

prices prohibitive. "Mr. Sam

Alexander, returned from Ohio with John

Seymour," she reported, "&

told Felix Seymour . . . that the farmers there

held their stock much higher than they

do here, that not any of them had

sold when they left Ohio."

Frustrated in the Scioto Valley, the "cattle

merchants are buying up the cattle on

the branch lively," she wrote. Two

firms had acquired upwards of 500 head,

and 100 of these had gone to market

from Hardy County.

Daniel McNeill died in the early 1830'S,36 but fortunately

some of his

correspondence has survived and has

furnished a significant glimpse into the

relationship of the South Branch

settlers with the development of the beef

cattle industry in the Scioto Valley. As

has been shown, the Renicks and

other cattle raisers who originally

migrated westward from the South Branch

had a substantial influence on the

ante-bellum development of the national

beef cattle industry through the

transfer and adaptation of their feeding

methods and through the interstate sale

of their improved stock.37 Of prime

importance in this development, was the

Ohio Breeding and Importing Com-

pany, formed in 1833 for the purpose of

bringing Shorthorns from England.

Investors in this profitable joint-stock

company, which liquidated its assets

in 1837, included the Renicks and other

cattlemen of the Scioto Valley,

John and Strawder McNeill and others who

also had come to Ohio from

the South Branch.38 Throughout

the pre-Civil War period, South Branch

stockmen raised and fed beef cattle on a

smaller scale than those on the

more expansive lands of the emergent

West, but the eastern area, never-

theless, continued to furnish a dynamic

element in the development of

the western beef industry -- the industrious settlers

who were experienced

cattlemen.39

THE AUTHOR: John Edmund Stea-

ley III is Instructor, West Virginia

Center

for Appalachian Studies and Development,

West Virginia University. Previous

publi-

cations have appeared in West

Virginia

History and the Tennessee Historical

Quarterly.

|

NOTES ON THE ANTE-BELLUM CATTLE INDUSTRY FROM THE McNEILL FAMILY PAPERS

by JOHN EDMUND STEALEY III

The long-ignored story of the pre-Civil War cattle industry in Ohio has been the subject in recent years of several scholarly studies which have enhanced the meager bibliography of American agricultural history. Previously only a few major works dealt with the beef trade on a general, national basis. The most notable of these are James Westfall Thompson's History of Livestock Raising in the United States, 1607-1860 and Charles Townsend Leavitt's original research in his 1931 University of Chicago dissertation "The Meat and Dairy Livestock Industry, 1819-1860."1 Ohio's role in the production and marketing of meat animals, however, won deserved recognition in Paul C. Henlein's description of cattle driving from Ohio in a 1954 Agricultural History publication as well as in his important monograph, Cattle Kingdom in the Ohio Valley, 1783-1860,2 and in the specialized articles by Robert Leslie Jones in the Ohio Historical Quarterly in 1955.3 The paucity of manuscript material, almost non-existent on many phases of the ante-bellum industry in Ohio and in the nation, has hindered research by agricultural historians. Henlein's use of previously unexamined manu-

NOTES ARE ON PAGES 70-72 |

(614) 297-2300