Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

|

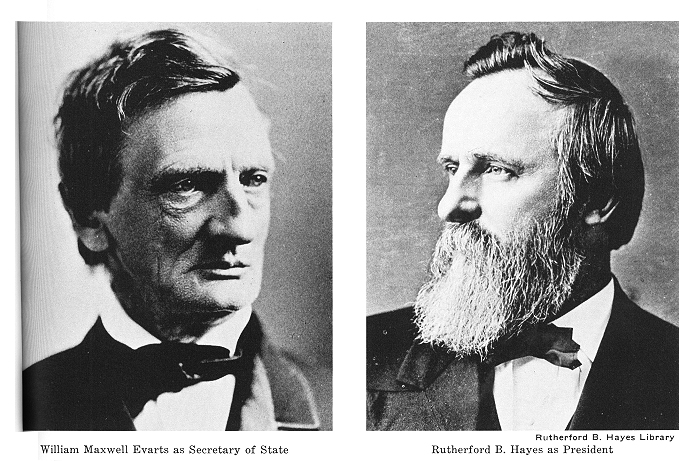

Public Opinion and the Chinese Question, 1876-1879 by GARY PENNANEN Diplomatic problems are not considered to have been of much conse- quence during the presidency of Rutherford B. Hayes. While not many pre- World War I judgments concerning the history of the period have escaped revisionism, an assessment of Hayes's diplomacy made by Charles R. Wil- liams in 1914 has withstood the test of time: "Few subjects of large im- portance in the foreign relations of the Government demanded action or attention during the administration of Mr. Hayes. For the most part all our dealings with foreign countries were amicable and were conducted without feeling or friction."1 This conclusion is still accepted by diplomatic historians even though several monographs and two scholarly biographies NOTES ON PAGE 201 |

140 OHIO HISTORY

of William Maxwell Evarts, Secretary of

State under Hayes, have added

more detail about specific incidents.2

Alexander DeConde concluded in a

recent comparison of American

Secretaries of State that Evarts "in fact, is

one of the lesser-known Secretaries, one

who dealt with no great interna-

tional problems."3 Judging

from the scant space devoted to foreign rela-

tions by Hayes's most recent biographer,

he too agreed with the Williams

assessment.4

Conclusions relating to the

insignificance of diplomacy during the Hayes

administration depend, in part, on the

assumption that the American public

did not become excited about foreign

policy. Allan Nevins stated that the

Virginius affair of 1873 "was the last formidable storm on

the sea of foreign

relations that [Hamilton] Fish had to

confront. Thereafter, no important

group of Americans were to become

aroused over any international prob-

lem until, more than a decade later,

Grover Cleveland threatened condign

[appropriate] action against Canada in

the fisheries dispute."5 Nevins' re-

mark was based upon a grossly distorted

image of public reaction to foreign

policy in the late 1870's and early 1880's.

In The Awkward Years, David M.

Pletcher has shown how public pressure

for foreign markets shaped the

diplomacy of the Garfield and Arthur

administrations.6 No overall study of

comparable depth exists for the problems

in foreign affairs during the Hayes

administration, but there is evidence

that during this period the public be-

came aroused by border troubles with

Mexico, a French attempt to con-

struct a canal through the Isthmus of

Panama, and Chinese immigration

that seemed to threaten the western

labor force.7

On no issue did Hayes and Evarts feel

the effect of public opinion as

much as that of Chinese immigration.

Although Chinese immigrants gen-

erally had been welcomed to the United

States in the 1850's and 60's to

assist in railroad building and mining

operations, a movement for their

exclusion made rapid headway during the

depression of the 1870's, especial-

ly on the Pacific Coast. Even before the

Panic of 1873, Chinese were dis-

liked in California. Beginning as early

as 1850, California discriminated

against the immigrants by a number of

means, including special mining

taxes, passenger taxes, head taxes,

school segregation, and laws forbidding

them to testify against white men.8

The chief restraint to the anti-Chinese

movement was the Burlingame

Treaty of 1868, which contained liberal

immigration provisions. Article V

permitted the free immigration of the

citizens of China and of the United

States "from the one country to the

other for the purposes of curiosity, of

trade or as permanent residents,"

and for those purposes both nations

reprobated "any other than an

entirely voluntary emigration." Article VI,

moreover, gave Americans visiting or

residing in China and Chinese sub-

jects visiting or residing in the United

States "the same privileges, immuni-

ties and exemptions in respect to travel

or residence as may there be en-

joyed by the citizens or subjects of the

most favored nation." Because the

Supreme Court ruled that state

legislation designed to restrict Chinese im-

migration violated these provisions, it

was necessary for the exclusionists

to seek revision of the treaty.9

THE CHINESE QUESTION 141

Hayes first became fully aware of the

Chinese issue during the campaign

of 1876. At the Republican convention in

Cincinnati, western delegates de-

nounced the evils of the Chinese labor

invasion and demanded a congres-

sional investigation of it. Although a

group of easterners led by George

William Curtis opposed the least effort

to interfere with the principle of

free immigration, the Republican platform

announced "the immediate duty

of Congress fully to investigate the

effect of the immigration and importa-

tion of Mongolians on the moral and

material interests of the country."10

The Democratic platform was more

forthright. It criticized a policy which

"tolerates the revival of the

coolie trade in Mongolian women imported for

immoral purposes, and Mongolian men,

hired to perform servile labor con-

tracts." As a solution, it demanded

"such a modification of the treaty with

the Chinese Empire, or such legislation

by Congress within constitutional

limitations as shall prevent the further

importation or immigration of the

Mongolian race."11

As the Republican candidate, Hayes found

himself caught up in the

controversial Chinese question. A

typical West Coast Republican summed

up his own reaction to the Chinese plank

in the platform: "It is just enough

to stir up the missionary and

humanitarian element of New England. Yet

not enough to conciliate the laboring

classes of the Pacific Coast."12 Some

Republicans advised Hayes to take a

strong stand against Chinese immigra-

tion if he wished to win votes in the

West,13 but others opposed such a

course. Mild as it was, eastern

Republicans resented the admission of the

plank in the platform. John Bingham, the

American minister in Tokyo,

wrote Hayes that the platform was all he

"could desire save the Chinese

resolution," the objectives of

which were sound, but the implementation of

which might lead to accusations that the

nation was unjustly treating the

Chinese. 14

Although Hayes avoided the Chinese issue

during the campaign, his

election did nothing to change the

situation, for anti-Chinese sentiment in-

creased. A joint congressional committee

set up to investigate the problem

released its report in February 1877.15

The anti-Chinese character of most

of the testimony taken by the committee

provided evidence for critics of

Chinese immigration. During the summer,

Chinese were attacked by hood-

lums in San Francisco, and under the

leadership of Dennis Kearney, the

California Workingmen's party adopted

the slogan, "The Chinese must

go."16 On August 13, a committee of

the California senate submitted a me-

morial to Congress recommending that the

United States and Great Britain

act together with China to abrogate all

treaties permitting Chinese to im-

migrate to the United States.17

While the committee publicly denounced

the evils of Chinese immigration, Hayes

received information to the con-

trary from a private source. An employer

of Chinese labor in California

reported that since the Chinese did not

have a friend on the committee,

there could not "have been a more

one-sided affair." He also praised the

Chinese for being "docile and

easily managed and controlled--while many

of the white laborers when they get a

few dollars ahead go off on a drunk."18

142 OHIO HISTORY

Critics of Chinese immigration contended

that the Chinese competed

unfairly with white labor because they

could live more cheaply than whites,

who often had families to support and

who were accustomed to better food

and housing. They argued that many

Chinese immigrants came to the

United States as coolies, whose passage

money was paid beforehand. Such

immigration, being involuntary, was

contrary to the Burlingame Treaty.

Socially, the Chinese were condemned for

living in crowded hovels, smok-

ing opium, having no wives, and

importing prostitutes from China. Politi-

cally, they were considered

unassimilable because they lacked experience

with republican institutions.19 "CALIGULA

issued a decree elevating his

horse to the dignity of Roman

citizenship," declared the San Francisco

Chronicle. "This was a mild proceeding compared to the

proposition of

trying to make American citizens out of

the offscourings of China that

have been poured on our shores."20

Despite the pressure, Hayes and

Secretary Evarts continued to ignore

the problem. Hayes failed to mention

Chinese immigration in his first

annual message,21 and Evarts neglected

it in his instructions to George F.

Seward, his minister in Peking.22 Their

silence is understandable. Not only

did the issue threaten to split the

Republican party, but also it posed a

threat to American relations with China.

Probably they hoped that the

agitation would cease as the country

returned to more prosperous times.

But their seeming indifference shocked

the Pacific Coast. The San Fran-

cisco Chronicle criticized

Hayes's message for "the total absence of any

allusion to the urgent demands of the

Pacific Coast for relief from the

evils of Chinese immigration." To

the Chronicle it appeared "utterly im-

possible to convince the people of the

East, or the Executive department of

the Government, that anything needs to

be done in the matter."23

The California legislature instructed

the state's representatives and sena-

tors to secure the cooperation of the

federal government in stopping Chi-

nese immigration. Accordingly, on

December 16, Congressman Horace F.

Page requested Hayes to make Chinese

immigration the subject of a

special message to Congress.24 His

congressional colleague, Horace Davis,

consulted personally with Hayes25 and

with Evarts. He complained that

Chinese immigration violated the

involuntary provisions of the Burlingame

Treaty. To stop the flow of coolie

labor, he recommended that the United

States pass the same kind of restrictive

legislation as the British had in

Australia, the Dutch in Java and Ceylon.

Davis estimated that there were

already 30,000 to 35,000 Chinese in San

Francisco; 80,000 to 90,000 in all

of California; and 150,000 to 175,000 in

the entire country.26 Quite clear-

ly, the majority of Californians wanted

an end to the influx of Chinese

labor.

Hayes finally responded with only a

statement of sympathy for the people

of the Pacific Coast in their desire to

check Chinese immigration.27 The

New York Times predicted that the

President would also send a special

message to Congress on the subject. This

he failed to do, however, when

it met in January 1878.28 Left without

Presidential leadership, both houses

of Congress passed a resolution, first introduced by

Senator Aaron A. Sar-

THE CHINESE QUESTION 143

gent of California, which, in the form

finally adopted by the House on

June 17, recommended that the President

open negotiations with China

to secure a change or abrogation of

existing treaties that permitted the un-

limited immigration of its citizens.29

Evarts had to await the arrival of two

Chinese ministers in Washington,

Chen Lan Pin and Yung Wing, on September

21 before he could even

act upon the demands of Congress. Then

he hesitated until November

21 before he finally inquired whether

their government wished to revise

treaty relations with the United States.

They replied that China wanted

to maintain its treaties with the United

States and that they had no in-

structions to negotiate on Chinese

immigration. They reminded Evarts

that if such immigration was

unacceptable, the Americans had only them-

selves to blame, for it was by the

efforts of the American people and their

former minister to China, Anson

Burlingame, that the treaty had been

arranged. Moreover, they did not believe

that the Chinese population of

the United States would grow as fast as

alarmists predicted because their

government did not encourage emigration

and because many immigrants

returned home.30

Although the attitude of the Chinese

ministers to treaty revision was

discouraging, Hayes maintained a facade

of public optimism. In his second

annual message, he announced the

establishment of the permanent Chinese

legation in Washington. "It is not

doubted," he added, "that this step will

be of advantage to both nations in

promoting friendly relations and re-

moving causes of difference."

Beyond this hope, he recommended no con-

crete solutions; nor did he even refer

to Chinese immigration specifically

by name.31 Again the Pacific

Coast felt slighted. Philip Roach of the Demo-

cratic San Francisco Daily Examiner wrote

Senator Thomas F. Bayard of

Delaware that "the quickest and

surest way of dealing with the problem

is by Executive Action; and President

Hayes should be held responsible

for not suggesting a modification in his

Annual Message. In 1874 Grant

did so."32

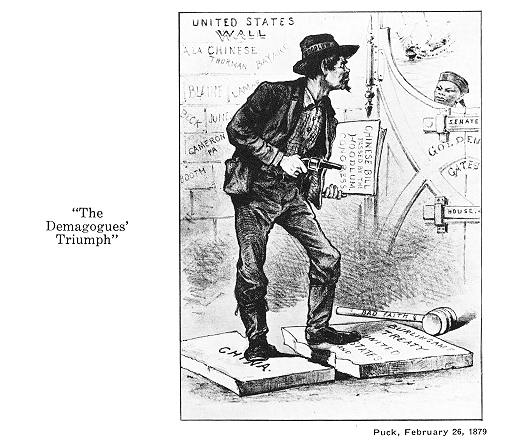

When Congress assembled in January 1879,

the House committee on

education and labor submitted a report

that criticized Presidential inac-

tion. It also urged Congress to pass a

bill allowing no master of a vessel

to take on board at a foreign port more

than fifteen Chinese passengers

with intent to bring them to the United

States.33 The fifteen passenger

bill passed the House on January 28 by a

vote of 155 to 72, and the Senate

on February 15 by a vote of 39 to 27.

The Senate added an additional

provision to the bill requiring the

President to abrogate Articles V and

VI of the Burlingame Treaty. The bill

was overwhelmingly favored by

western Senators, and also won the

support of eastern, southern, and mid-

western Senators such as James G. Blaine

of Maine, Lucius Q. Lamar of

Mississippi, and Allen G. Thurman of

Ohio.34

Soon after the House passed the bill,

newspapers throughout the country

began to speculate on the possibility of

a Presidential veto. Hayes's staff

filled page after page in one of his

scrapbooks with editorials on the sub-

ject. These indicate that major papers

of both parties throughout the East

144 OHIO HISTORY

unanimously favored a veto but that the

Pacific Coast overwhelmingly

supported the bill. Most midwestern and

southern papers supported the

veto with such notable exceptions as the

Chicago Tribune, Cincinnati

Enquirer, St. Louis Globe Democrat, and Richmond Dispatch.

"On the

whole," declared the Chicago Tribune,

"the legislation is justifiable, is

demanded by public sentiment, is free of

all moral, political, and com-

mercial objections." But few people

east of the Rocky Mountains agreed

with it.35

Letters and telegrams, as well as the

newspapers, kept Hayes informed

of public opinion on the fifteen

passenger bill. These show that even

though many eastern opponents of the

bill favored restrictions on Chinese

immigration, they opposed the

legislation because it involved a unilateral

modification that could be construed as

abrogation of the Burlingame

Treaty by the United States. One of

Anson Burlingame's friends reminded

Hayes that the people of the United

States could alter their Constitution

at pleasure, "but to change a

treaty requires also the consent of the For-

eign Power with whom it has been

made."36 John A. Dix, formerly Sec-

retary of the Treasury under Buchanan,

minister to France, and governor

of New York, urged Hayes not to sign

because there was nothing worse

than a breach of faith on the part of

the government. He accused "aspir-

ants for political preferment" of

dishonoring the nation by catering to

the laboring classes in order "to

conciliate them & gain their votes."37

Others believed that free immigration

was a basic principle of the coun-

try. George William Curtis thought it

amazing "that the Republican party

should be the first to shut the gates of

America on mankind."38 For the

United States to exclude immigrants,

wrote the president of Amherst Col-

lege, would be "to embody that

spirit of the Chinese themselves which the

civilized world has protested against

and fought against and which having

broken down in the Chinese we now adopt

as the principle of our own

national life!"39 One

religious paper expressed the forebodings of many:

"It is a dangerous precedent; for

with such discriminations once permitted,

some partisan outcry may call for the prohibition

of German, or Irish, or

English immigration."40

Religious leaders feared that China

might retaliate by disregarding treaty

protection accorded American

missionaries. "But the great consideration,

touching the heart of the whole Christian

Church of every devotion," a

Washington clergyman warned Hayes,

"is the danger of retaliatory action

in China."41 Fifty members of the

Yale faculty reminded him that the bill

would furnish China "all the

example and argument needed, according

to the usages of international law, to

justify it in abrogating this principle

of ex[tra]-territoriality. To do so will

throw out our countrymen living

in China from the principle of our

laws."42 The American Missionary As-

sociation and the Missionary Society of

the Methodist Episcopal Church

urged him to veto the bill,43

and Henry Ward Beecher, the eloquent

Brooklyn preacher, assured him that a

veto would receive the support of

ministers of the Gospel, teachers, and conservative men

of property.44

Eastern merchants also feared

retaliation. The Philadelphia Maritime

THE CHINESE QUESTION

145

Exchange warned Hayes that if he failed

to veto the bill, "the interests of

the trade and commerce of the United

States with the Chinese Empire

will be greatly imperilled."45

In New York the Chamber of Commerce

condemned the bill "as exposing the

merchant in his dealings to the con-

sequences of public dishonor; and

finally, as presenting the hasty action

of our Congressional Body in sorry

contrast with the more cautious and

dignified wisdom of the Heathen

Empire."46 Edwards Pierrepont, former

minister to Great Britain, could

"imagine no greater folly than to shut

ourselves out from the trade and the

reciprocal market of quite the most

populous Empire on earth . . . and how a

statesman can be willing to sac-

rifice our great advantage, which

England will seize, to a temporary clamor

is inconceivable."47

The Pacific Coast made a valiant, last

minute effort to prevent a veto.

'The state of feeling on the Pacific, as

I learn from all sources is intense

and universal," Senator Sargent

wired Hayes on February 25. He enclosed

a telegram from the editor of the San

Francisco Bulletin announcing that

"all prudent men dread Veto as

greatest possible calamity."48 From the

governors of California and Nevada, and

from the mayors of San Francisco,

Los Angeles, and Sacramento, Hayes

received telegrams, resolutions, or

memorials hostile to Chinese

immigration.49 Even commercial organiza-

tions such as the Portland Board of

Trade and the Astoria Chamber of

Commerce favored the bill.50 One

exception was provided by some Pres-

byterian, Congregationalist, Methodist,

and Baptist clergymen in San Fran-

cisco and Oakland, who preferred

"to see at present no Congressional ac-

tion on the Chinese question."51

A former employer of Chinese immigrants

praised them as "faithful and

industrious" and "plodding and intelligent,"

but a semi-literate ranch hand from

Nevada wrote that "able backed men

are beging for bred when all would have

employment at good wages if

the Pacific Coasts was not being litery

overrun with Chinamen."52

Republican organizations in California

pleaded with Hayes to sign the

bill for the future interests of the

party on the Pacific Coast.53 A telegram

from the editor of the San Francisco Morning

Call warned Senator Sar-

gent that "there are but few

persons here now who do not believe the

President ought to sign the bill. The

state will go Democratic if the bill

is Vetoed."54 By

supporting anti-Chinese legislation, California Republi-

cans had hurt the Democratic party.

Philip Roach complained to Senator

Bayard that "the Working men have

left us to follow the leadership of

Kearney a Republican," who

"has carried off two-thirds of our party by

his cry 'the Chinese must go.' "55 Republican

success depended upon the

party following Blaine on the Chinese

issue rather than other easterners,

such as Curtis and Beecher. The Portland

Daily Standard praised the

Plumed Knight from Maine: "Let him

lay aside 'the bloody shirt,' don the

armor of the warrior in defense of free

white labor, and cease not or flag

in the fight until the fiat of the

Government shall proclaim that the Chinese

must go."56

With the assistance of the advice he was

receiving, Hayes at last made

some conclusions of his own. Aside from

the damage that a veto might do

146 OHIO HISTORY

in the Far West, he undoubtedly realized

that it would be politically ad-

vantageous. His own sources of

information, editorials, letters, and tele-

grams, enabled him more accurately to

assess public opinion than could

Blaine or other eastern Republicans who

had supported the fifteen pas-

senger bill at the time of its passage.

Blaine seriously miscalculated eastern

opinion. "The sentiment against that

bill is growing very strong," Con-

gressman Garfield of Ohio recorded in

his Diary. "I am satisfied that Sena-

tor Blaine has made a great mistake in

his advocacy of it."57 Blaine's error,

in fact, cost him eastern support for

the Republican nomination in 1880.58

Even though Hayes did not, like Curtis,

think that free immigration was

a basic principle of the Republic, he,

unlike Blaine, wished to avoid dras-

tic solutions. Although he had concluded

that Chinese immigration was

"pernicious" and he was

willing to "consider with favor measures to dis-

courage the Chinese from coming to our

shores," he realized that the pres-

ent bill was "inconsistent"

with treaty obligations. "We have accepted the

advantages which the treaty gives,"

he noted in his Diary. "Our traders,

missionaries, and travellers are

domiciled in C[hina]. Important interests

have grown up under the treaty, and rest

upon faith in its observance."

If the United States abrogated the

treaty, he feared that American citizens

in China "would be left without

treaty protection." Moreover, he believed,

with others, that the Burlingame Treaty

was of our seeking. "If we assum-

ing it to have been a mistaken policy. [sic]

It was our policy. We urged it

on China. Our minister conducted

it."59

Secretary Evarts appears to have had

influence with Hayes also. Congress-

man Garfield's Diary records Evarts'

participation in a meeting held on

February 23: "I advised him [Hayes]

to veto the bill, and point out, fully

the iniquity of its provision --

Secretary Evarts was there and joined in

the discussion. I am sure the bill will

be vetoed."60 Following this meet-

ing, Hayes set down his decision in his

own Diary: "In the maintenance of

the National faith it is in my judgment

a plain duty to withhold my ap-

proval from this bill. We should deal

with China in this matter precisely

as we expect and wish other nations to

deal with us."61

Evarts, even more than Hayes, was aware

of the dangers of the unilateral

abrogation of a sacred treaty. The

Chinese ministers in Washington com-

plained to him that the bill was

offensive to their countrymen. They could

excuse the abusive language of the

common people as that of inferior

characters, but were shocked to hear

"eminent public men" using similar

words. They also requested protection

for the Chinese in San Francisco.

On February 28, Evarts assured them that

the United States would observe

its treaty obligations free from popular

and political considerations.62

Hayes's veto message, which may have

been written by Evarts, was sent

to Congress on March 1. It dealt

primarily with the history and provisions

of the Burlingame Treaty, the

constitutionality of the treaty-making pro-

cess, and the dangers of unilateral tampering

with treaty obligations. Hayes

pointed out that the power to make a new

treaty and to modify an exist-

ing treaty, as the fifteen passenger

bill proposed to do, was not lodged by

|

THE CHINESE QUESTION 147 the Constitution in Congress, but was the prerogative of the President with the concurrence of two-thirds of the Senate. Moreover, the denuncia- tion of one part of the treaty by the United States liberated China from the whole treaty including the Treaty of Tientsin of 1858 of which the Burlingame Treaty was only a supplement or amendment and which con- ferred important privileges on Americans in China. He did not believe that "the instant suppression of further immigration from China" justi- fied "an exposure of our citizens in China, merchants or missionaries, to the consequences of so sudden an abrogation of their treaty protection." At the same time, he promised to consider "renewed negotiations, of the |

|

difficulties surrounding this political and social problem." He also indi- cated that "the simple provisions of the Burlingame treaty may need to be replaced by more careful methods, securing the Chinese and ourselves against a larger and more rapid infusion of this foreign race than our sys- tem of industry and society can take up and assimilate with ease and safety."63 |

148 OHIO HISTORY

The bill's supporters in the House

immediately put the veto to a test.

A new vote was taken on the bill, but it

did not receive the required two-

thirds majority.64 Samuel

Randall, the Speaker of the House, privately

"denounced the anti-Chinese

business as bosh and clap trap," and stated

that he believed many men in the House

who voted to pass it over the veto

were glad it had failed.65 Even

though Congress sustained him, Hayes feared

that his message had been inadequate.

"You will approve of what is done,"

he wrote Beecher, "but may think a

fuller treatment of the subject ought

to have been given. You must consider

how pressed we are for time -- no

time to investigate and an ocean of

facts poured on us--"66

The veto was generally approved east of

the Rocky Mountains, but was

bitterly denounced in the West, even

though The Nation thought it was

based "on grounds to which the

'Hoodlums' of California can take no ex-

ception."67 On the following day, with

but three exceptions, dispatches

flooded the office of the Associated

Press in San Francisco bitterly denounc-

ing Hayes.68 In one town he

was burned in effigy. Despite the veto, the

people of the Pacific Coast did not

fully realize how much he sympathized

with them. They could not read the

comments in his Diary about what he

considered to be the perniciousness of a

population which could not as-

similate with Americans. "It should

be made certain by proper methods

that such an invasion can not," he

concluded, "permanently override our

people. It cannot safely be admitted

into the bosom of our American So-

ciety."69

The following year, Evarts sent a

three-man commission to China that

negotiated a new immigration treaty allowing

Congress to "regulate, limit,

or suspend" the immigration of

Chinese laborers. It provided the legal

basis under which Congress passed the

Chinese Exclusion Act of May 1882,

suspending the immigration of Chinese

laborers for ten years.70 By adher-

ing to treaty obligations and resorting

to diplomacy, Hayes preserved the

position of American missionaries and

merchants in China. William Dean

Howells, the editor of the Atlantic

Monthly, praised his decision: "The

Chinese veto-message was everything your

friends could have wished in

dignity, humanity and common sense of

justice. In that and the silver veto

and the New York Custom House business

and your good will to the irre-

claimable South, you have made history

of the best kind."71

The President made history, but history

has neglected the President's

achievement. Had he signed the bill, and

had China retaliated against

Americans residing in its Empire, there

might have been a serious crisis.

By making the right decision rather than

the wrong one, he prevented a

possible international conflict. But it

does not follow that Chinese immi-

gration was an insignificant diplomatic

problem, nor that the public failed

to become excited about it. Even so,

Hayes nevertheless listened for three

years to the public debate on the

subject before he felt compelled to break

his silence and provide Executive

leadership for the nation.

THE AUTHOR: Gary Pennanen is As-

sistant Professor in the History Depart-

ment at Wisconsin State University, Eau

Claire.

|

Public Opinion and the Chinese Question, 1876-1879 by GARY PENNANEN Diplomatic problems are not considered to have been of much conse- quence during the presidency of Rutherford B. Hayes. While not many pre- World War I judgments concerning the history of the period have escaped revisionism, an assessment of Hayes's diplomacy made by Charles R. Wil- liams in 1914 has withstood the test of time: "Few subjects of large im- portance in the foreign relations of the Government demanded action or attention during the administration of Mr. Hayes. For the most part all our dealings with foreign countries were amicable and were conducted without feeling or friction."1 This conclusion is still accepted by diplomatic historians even though several monographs and two scholarly biographies NOTES ON PAGE 201 |

(614) 297-2300