Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- 19

|

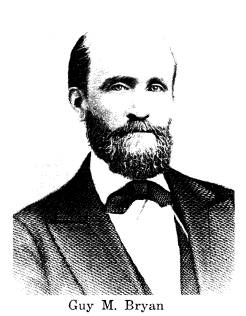

Race: Principles and Policy of Rutherford B. Hayes by GEORGE SINKLER When Rutherofrd B. Hayes came to the presidency, the race problem was waiting in all its urgency. The subject was by no means new to him. As an Ohio Congressman, at the very beginning of his political career, he endorsed the Radical program of reconstruction. In unemotional terms this meant having a penchant for Negro rights and the preservation of the political power of the Republican party, though not necessarily in that order.1 A college classmate and lifelong friend. Guy M. Bryan of Texas, became a little uneasy about the Radical proclivities of Hayes. When the Recon- struction acts were passed, the two men began a correspondence that con- tinued long after Hayes left Washington. Bryan was to be the conscience of the white South continually working on Hayes. From 1867 on he sang but one monotonous, though effective song: The South wanted peace and reunion above everything. Only unscrupulous persons who stirred up trou- ble between the superior whites and the inferior blacks prevented the heal- ing of the wounds of war. The Negro would be better off if left to his former master. Bryan skillfully applied the argument of "kith and kin": Hayes let me appeal to you as one with whom I have so often broken bread, whose associations so long were identified with my own, whose blood and skin are from the same tree, . . . I beg of you to aid us in resisting the reckless manner with which the question of race is dealt with by the agitators at the South.2 I here say that Southern and Northern people are of the same blood and people, and that they and the Negro are not from the same stock. . . . The South is worth cultivating by the American statesman.3 Bryan was attempting to reach this northern heart by strumming the tune of ethnological kinship on the banjo of race. But Hayes does not seem to have been immediately affected by his pleas, at least not as far as official politics were concerned. He bravely flew in the face of anti-Negro sentiment in Ohio with a radical speech on August 5, 1867. He even ran for governor of that state on an extremely unpopular platform of Negro suffrage. He saw great merit in the Radical reconstruction plans of 1867. He declared that the war was fought for equal rights for all colors as well as for union. He agreed that troops were necessary in the South to protect both white NOTES ON PAGE 203 |

HAYES and RACE 151

and black Union men. Lashing out at

states rights and the rebels, Hayes

said: "They [southerners] wish to

return to the old state of things--an oli-

garchy of race and the sovereignty of

states . . ." He rebuked the

Peace

Democrats for opposing "every

measure tending to the enfranchisement and

elevation of the African race . . .

laboring to keep alive and inflame the

prejudice of race and color, on which

slavery is based."4 Campaigner Hayes

of 1867 seems poles apart from the Hayes

as President in 1877.

As governor, Hayes challenged the

concept of the Democrats that the

United States was a white man's

government and that the conferral of "suf-

frage on the colored races--the African

or Chinaman . . ." would destroy our

government.5 During his

radical flirtations Hayes could also wave the

"bloody shirt." In response to

a speech by John Sherman on the "Ku Klux

outrages" Hayes approvingly said:

"It will do us great good. You have hit

the nail on the head. Nothing unites and

harmonizes the Republican Party

like the conviction that democratic

victories strengthen the reactionary and

brutal tendencies of the rebel states."6

But by March of 1875 the "Thermi-

dorean Reaction" had begun to set

in and Hayes wrote: "I doubt the ultra

measures relating to the South."7

But this is getting ahead of our story.

Hayes had a long history of contact with

and concern for Negroes and

the protection of their civil rights. As

a young lawyer in Cincinnati, Ohio,

he defended fugitive slaves.8 He was

well supplied with Negro servants.9 His

staff of domestics may have been

integrated because he spoke of "our Ger-

man girl, Anna." Anna found a naked

Negro infant on the steps of the

Hayes residence in Cincinnati and

"after a deal of trouble [Hayes] got the

little thing into the Negro orphan's

asylum."10 He was always aware of the

presence of the Negro.11

While still in the throes of so-called

Radicalism, Hayes orally assigned

the Negro a very high place in American

life. As he saw it, the Negro was

not an alien for some of them had voted

and defended the flag since colon-

ial days; nor was this a white man's

country. Speaking as a gubernatorial

candidate in Ohio in 1867 he said of the

Negroes:

Whether we prefer it or not, they are

our countrymen, and will re-

main so forever. They are more than

countrymen--they are citizens . . . .

Our government has been called the white

man's government. Not so.

It is not the government of any class,

or sect, or nationality, or race. It

is a government founded on the consent

of the governed . . . . It is not

the government of the native born, or

the foreign born, or the rich

man, or of the poor man, or of the white

man, or of the colored man--

it is the government of the free man.12

Once when he was President and the

activities of the southern redeemers

caused some Florida Negroes to consider

emigration to Santo Domingo,

Hayes, in a letter to a Negro preacher,

disapproved: "My impression is that

your people should not be hasty in

deciding to leave this country. The mere

difference in climate is a very serious

objection to removal . . . . It is my

opinion also that the evils which now

affect you are likely steadily, and I

hope, rapidly to diminish. My advice is

. . . against the proposed emigra-

152 OHIO HISTORY

tion."13 While the Negroes should

not leave the country, their current

exodus from the South, Hayes felt, was a

good thing in that the "better

class of Southern people" would be

forced to suppress the violence of the

ruffian class and protect the rights of

the remaining Negroes. Significantly

Hayes remarked: "Let the emigrants

be scattered throughout the North-

west. Let them be encouraged to get

homes and settled employment."14

Long after he left the presidency Hayes

was no less convinced that the

Negro should have an equal place in

American life. At the Lake Mohonk

Conference on the Negro in 1890, he made

the whites responsible for the

Negroes' presence and his condition in

America. Indeed, he said, they were

"the keepers of 'our brother in

black.' " At this time Hayes found the char-

acter and personal conduct of the

freedmen "unpromising and deplorable.

It is perhaps safe to conclude that half

of the colored people of the South

still lack the thrift, the education,

the morality, and the religion required

to make a prosperous and intelligent

citizenship." In spite of that dark

assessment Hayes was encouraged "in

respect to the future of this race" and

concluded that after just twenty-five

years of freedom the Negro had not

done badly: "One third of them

[could] read and write. Not a few of them

are scholars of fair attainments and

ability, and in the learned professions

and in conspicuous employments are

indicating their title to the considera-

tion and respect of the best of their

fellowmen."15 One thing that deepened

the faith of Hayes in the Negro

potential was his experience with black

pilots--the grandsons of slaves--taking

ships in and out of Bermuda's reef-

beleaguered harbor in situations where

"the most solid qualities that are

supposed to belong peculiarly to our

Anglo-Saxon race are needed."16

Hayes was keenly aware of the presence

of race prejudice in American

life. He accused the Democrats of making

great use of prejudice against

Negroes. Yet he was optimistic:

"The Negro prejudice is rapidly wearing

away, but is still strong among the

Irish, and people of Irish parentage, and

the ignorant and unthinking

generally."17 Hayes did not think that racial

antagonism was the chief cause of

conflict among men. He found differ-

ences of class, nationality, language

and religion equally as divisive. His-

tory taught him that "unjust and

partial laws" increased and created antag-

onism.18 When he was

President, he often warned of the dangers of race

prejudice,19 and on a tour

South in 1877 he subtly suggested that "State

Governments as well as the National

Government should regard alike

equally the rights and interests of all

races of men."20

With great regularity Hayes stated his

belief in the equality of all men

before the law.21 He

deprecated all attempts to place a racial hedge around

Jefferson's immortal dictum, "All

men are created equal." The founding

fathers did not declare all men equally

beautiful, strong, or intellectual,

but equal in their rights. It was

foolish to limit the phrase "all men, to the

men of a single race." Hayes thought

that Jefferson did include those of

African descent in his definition of

"men." Slavery was founded upon the

denial of the Declaration of

Independence and was the ultimate cause of

the Civil War.22

HAYES and RACE 153

In 1871, as he thought about retiring

from the political arena, Hayes ex-

pressed a belief that after the

settlement of the slavery question there were

no more struggles worthy of full

political commitment. He did not think

that any political or party revolution

could unsettle the fact that all men

in his country were to have equal civil

and political rights.23 It was his view

that "the administration of Grant

has been faithful on the great question of

the rights of the colored people."24

So frequently did the theme of equal

rights appear in the speeches of Hayes

that one would suspect that he

thought talking would make it so. Even

in 1877, he saw his country as "a

nation composed of . . . different races

. . . all of whom have equal

rights . . . ."25 He told himself

that he must "insist that the laws shall be

enforced . . . insist that every

citizen, however humble . . . be secured in

his right to life, liberty, and the

pursuit of happiness."26 Two months later

when he wrote his first annual message

to the nation he tried to convince

the South of "the wisdom and

justice of humane local legislation" for the

education and general welfare of the

freedmen, "objects . . . dear to my

heart."27 In his second

annual message to Congress he accused the South of

failing to live up to its promise to

secure to all the equal protection of the

laws "without distinction of

color." He noted that Negroes were being mis-

treated in South Carolina and Louisiana

and asked Congress for funds to

allow the Justice Department to better

execute the Enforcement Act of

1871.28

In contrast with the patient, gentle,

and mild remonstrances of the annual

messages, the President's public

speeches to northern audiences, especially

soldiers, vigorously, righteously, and

indignantly condemned lawlessness in

parts of the South and called for public

support of all civil servants who

believed in sustaining Negro rights.

Since the war had been fought for

equal rights as well as union, the equal

rights amendments "ought to

stand."29

As he prepared to leave the White House,

Hayes knew that the race

question had persisted to plague all of his

efforts for reunion: "The dis-

position to refuse a prompt and hearty

obedience to the equal rights amend-

ments to the Constitution is all that

now stands in the way of a complete

obliteration of sectional lines and

political contests." 30 Hayes hoped that

Congress would seat no one whose

election was due to the violation of the

Fifteenth Amendment. His executive duty,

he said, was to prosecute the

guilty.31 There is no

evidence that he ever did.

How did Hayes stand on social equality?

The evidence on this point is

scanty but not without some

significance. Something of a social crisis was

created when a Negro, Frederick

Douglass, was appointed marshal of the

District of Columbia by Hayes. According

to one anonymous letter writer,

the selection of Douglass was distateful

to some people because the Marshal

acted as master of ceremonies at certain

White House functions. This corre-

spondent congratulated Hayes for serving

in that capacity himself at a re-

cent function and hoped he would

continue.32 Whether or not Hayes so

acted and for what reason cannot be

ascertained. But the very fact that

154 OHIO HISTORY

such a letter was written illustrates

the working of the idea of race in the

mind of one northerner, at the very

least.

In 1880, nearly fifteen years before the

famed Atlanta Exposition, Presi-

dent Hayes made a remark that

anticipated Booker T. Washington's his-

toric pronouncement on social equality.

The occasion was the twelfth

anniversary of Hampton Institute. Hayes

was one of the speakers. He cited

the problem of a multi-racial society as

the most difficult facing the nation

and then cast his lot with the

anti-amalgamationists:

We would not undertake to violate the

laws of nature, we do not

wish to change the purpose of God in

making these differences of na-

ture. We are willing to have these

elements of our population separate

as the fingers are, but we require to

see them united for every good

work, for national

defense, one, as the hand. [italics

added] And that

good work Hampton is doing.33

Evidently Hayes was not one to advocate

putting together what God so

markedly had put asunder. He could not

escape the customary ambivalence

in assigning the Negro his place in

American life: biological separation but

political and civil integration. As

presiding officer at the first Mohonk Con-

ference on the Negro question in 1890,

Hayes tried to rule out any discus-

sion of the controversial subject of

social equality. He preferred to defer

this question until both Negroes and

whites were more disposed to live by

the Golden Rule. He said:

What is sometimes called the social

question, with its bitterness,

irritations, and the ill-will which it

often breeds between the children

of a common father, may well be left out

of associations like this until

the Golden Rule, with its enlightenment

and precious tendencies, has

obtained a more perfect sway than it has

yet found either in our own

hearts or in the lives of those we are

seeking to lift up.34

Even though Hayes's basic principles in

regard to the political and social

aspects of the problems of race seem to

remain consistent through the years,

he often found it difficult to move

successfully from theory to practice,

especially when he tried to implement

political equality in his own state

and in the country at large. The

necessities of the times and of his position

seemed to alter or modify his ideas

somewhat. As Congress prepared in

December of 1865 to override Johnson's

plan of Reconstruction with one

of its own, Hayes advocated suffrage

with an educational qualification.35

But by January 10, 1866, he was saying:

"Universal suffrage is sound in

principle, the radical element is

right." As a Congressman, Hayes was not

very enthusiastic about Negro suffrage

in the District of Columbia. He

thought that Congress had more important

business to attend to than the

question of Negro voting in the

District.36 On the other hand he was pre-

occupied with the voting clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment and told a

friend: "I care nothing about the

other amendments but we cannot admit

the South until this Amendment is

safe."37 However, at this point Hayes

was thinking more about the political

balance of power between the sec-

tions than he was about the Negro as

such.38

HAYES and RACE 155

Congressman Hayes was not committed to

Negro suffrage without reser-

vation. When the committee on

reconstruction reported, Hayes said that

Negro suffrage would not be insisted

upon but that a difference of opinion

would be allowed.39 He told a

friend that the policy of the Republicans

would be to leave the question of the

ballot to the states.40

Gradually, however, Hayes worked himself

around to the position of un-

qualified political equality. In taking

this stand, he displayed great courage

when he ran the gauntlet of Negrophobia

and campaigned for the governor-

ship of Ohio under the political Jolly

Roger of Negro suffrage. An amend-

ment to strike the word

"white" from the Ohio constitution was before the

people. The Democrats declared that

their purpose was to nominate "men

of noble hearts, determined to release

the state from the thraldom of nig-

gerism." Hayes, on the other hand,

ran on the platform of "impartial man-

hood

suffrage" which meant the Negro, too!41 As a matter of

fact,

he would

not consent to run for governor unless

an opportunity was provided for an

honest vote on the suffrage issue.42

While the future President was at first

in favor of qualified Negro suffrage,

this did not mean that he had racial

reservations. He wanted the ballot given

to the Negro in Ohio on the same

basis that it was given to the white

man.43

Hayes won the governor's chair but the

Negro suffrage clause lost. In

his inaugural address he touched on the

subject of civil and political equal-

ity in Ohio. He gave a summation of the

battle for the elimination of race

distinctions in Ohio, beginning in 1849.

He said he was encouraged by the

fact that though Negro suffrage was

lately defeated, forty-five percent of

the vote was cast in favor of the

proposition. He also depreciated the at-

tempt which was afoot to repeal Ohio's

initial consent to the ratification

of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Significantly he defended the amendment

not on tile basis of the equal

protection of the laws clause which attempted

to protect a broad range of Negro rights

but on the voting rights article of

the amendment which called for reduction

of Congressional representation

for states discriminating against a

segment of the population in regard to

voting.44

In his second annual message of 1869,

Governor Hayes was still pleading

not only for the repeal of the voting

restrictions on "citizens having a vis-

ible admixture of African blood,"

but also for approval of the Fifteenth

Amendment. He repeated the plea in 1870.45 When the

amendment was

ratified in 1870, Hayes mistakenly thought

that he could now retire from

politics: "The ratification of the

Fifteenth Amendment gives me the boon

of equality before the law," he

told a friend.46 While he was sincerely hop-

ing to see the Negro cast his ballot, he

was no less joyful when that ballot

went to the Republicans. "They vote

Republican almost solid," he said of

Cincinnati Negroes casting ballots for

the first time under the new amend-

ment.47

Hayes sincerely thought that a political

millennium had come with the

passage of the Fifteenth Amendment.

Rather triumphantly he asked: "The

war of races, which was confidently

predicted would follow the enfranchise-

156 OHIO HISTORY

ment of the colored people--where was it

in the election in Ohio last week?"

Hayes did not doubt that the American

dream had been realized or that

the new citizen would "prove worthy

of American citizenship";48 by 1890

however, after two decades of hard

experience, he would alter his opinion

somewhat on both predictions.

Hayes spoke just as emphatically in

favor of Negro suffrage when he be-

came President as he had done so bravely

in Ohio. But he had far less

success in coercing the recalcitrant

South to implement his proposals. More

than talk and righteous indignation was

required to move the southerners.

The only thing that might have produced

a revolution in the South would

have been a solid North lined up behind

a courageous President willing

and able to enforce the law in all its

vigor. Neither condition prevailed.

Nationally Hayes was concerned with

wiping out the color line in poli-

tics, a theme to be developed later in

greater detail.49 He wanted also to

remove the influence of the military in

state elections.50 What hurt the Pres-

ident most, it seemed, was the way in

which some southerners rode rough-

shod over Negro rights "the protection

of which the people in these states

[Louisiana and South Carolina, in particular] have been

solemnly pledged."51

Even so, Hayes never suggested a remedy

for the racial maladies in the

South.

In 1878 southern Democratic Congressmen

made a concerted and deter-

mined attempt to repeal every last

vestigial remnant of federal protection

of Negro rights at the polls by

attaching riders (additional amendments) to

army appropriations bills. The riders

stipulated that none of the army ap-

propriations could be used to support

troops at the polls to enforce national

election laws. This was a critical hour

for Hayes as a civil rights statesman.

He was equal to the challenge. He vetoed

seven consecutive Army Appro-

priations Acts.52 In his

opinion not only was the protection of Negro voting

rights at stake but the integrity of

executive authority;53 he was determined

to maintain them both. But if the role

of race in politics is to be properly

understood and appreciated, some

attention must be given to the evolution

of the Southern policy (approach to the

race problem) of Hayes as Presi-

dent.

Guy M. Bryan must be reintroduced as an

important element effecting

this evolution. As Negro voters slowly

retreated in the face of southern

night riders determined to bring

Reconstruction to an end, Bryan inquired

of his former college chum: "Rud,

are we done with the Negro? Are you

not satisfied by this time that lie is

not fit to govern himself without the

government of the white man? Will the

Northern people force the Negro

question and social equality upon us

with the view to get the exciting ques-

tion up again for another canvass? Let

us have peace for God sake."54

In his reply to Bryan in 1875 before he

was President, Hayes suggested

that the remedy for the South's

illiteracy and racial ills was not the repudia-

tion of democratic government but the

education of the ignorant electorate.

The South must emulate the North and "forget

to drive and learn to lead

the ignorant masses around them."55

Hayes did not mention race prejudice

|

HAYES and RACE 157 |

|

the southern contention that the Negro was disliked solely because of his ignorance and his desperate con- dition. When Hayes again threw his hat in- to the political arena in 1875 as a gubernatorial candidate, Bryan was delighted. He told his old friend that if he took the position that the whites of the North and South were of the same "kith and kin," that the Negro must be returned to the South, he would be the nominee of his party for the next presidency, make a great name for himself and be regarded as a benefactor of his country.56 On the harp of politics, Bryan skillfully bent the theme of sweet reunion between northern and southern whites under the necessities of race. Hayes was not unmoved by this political and racial call to arms. He replied to Bryan: "As to Southern affairs 'the let alone' policy seems now to be the true course.... The future depends largely on the moderation and good sense of Southern men . . . but I think we are one people at last for all time."57 Such was the mood of Hayes on the eve of the election of 1876. He had tentatively ac- cepted the southern position. The southern exposure had taken effect. Only a similar persuasion of northern origin was needed to clinch the argu- ment--and that was not long in coming. In 1876 when the search for a suitable Republican presidential candi- date began, John Sherman cast his eyes in the direction of Spiegel Grove: "Considering all things," he told a colleague, "I believe the nomination of Governor Hayes would give us more strength . . . than any other person . . . on the main questions: protection for all in equal rights; and the observance of the public faith [Civil Service Reform] he is as trustworthy as anyone named."58 After Hayes received the nomination, Carl Schurz acted as a powerful northern persuader for these points. He sent Hayes lengthy sug- gestions for his letter of acceptance. His advice on the Southern question was particularly significant: You can make this your campaign and relieve it of all the vulnerable points of the party record. You can accomplish this by . . . declaring that the equality of rights without distinction of color according to the constitutional amendments must be sacredly maintained by all lawful power of government; but that also constitutional rights of local self- government must be respected; and that a policy must be followed which will lead this nation into the second century of its existence, |

158 OHIO HISTORY

not as a nation divided into conquerors

and conquered, but as a na-

tion of equal citizens."59

Here was an excellent example of studied

and calculated political ambi-

valence. With respect to Negro rights,

how could the laws be enforced while

local self government was respected?

Schurz had first hand knowledge of the

indisposition of the southerners to give

the Negro his rights, so his optimism

in this regard is inscrutable. Hayes, in

the meantime, promised to give the

suggestions his "best

consideration" and said:

I now feel like saying something to the

South not essentially dif-

ferent from your suggestions, but I am

not decided about it. I don't

like the phrase, by reason of its

Democratic associations, which you use

-- 'local self government'! . . . It

seems to me to smack of the bowie-

knife and revolver. 'Local

self-government' has nullified the Fifteenth

Amendment in several states, and is in a

fair way to nullify the Four-

teenth and Thirteenth. But I do favor a

policy of reconciliation, based

on the observance of all parts of the

Constitution--the new as well as

the old--and, therefore, suppose you and

I are substantially agreed on

the topic.60

One can see from the preceding

statements that Hayes knew what the

situation was in the South. But a

dilemma was soon to be faced. How could

reunion, on the one hand, be reconciled

with a vigorous enforcement of the

amendments relating to the new status of

the freedmen, on the other?

Would Hayes be a Moses of civil

liberties for a despised race or a Joshua

of reunion? While he sincerely wanted

and tried to do both, the role of

Joshua appealed to him most. The

possibilities of significant accomplish-

ment were great since Hayes had

committed himself to a single term long

before he knew that there would be a

disputed election. He would come to

the presidency unhampered by the need to

mend his personal political

fences for the next election.61

By July of 1876 Hayes seemed to have

been won over to that part of

the Bryan position calling for leaving

the South to the redeemers: "You

will see in my letter of

acceptance," he assured the unrelenting Texan,

the influence of the feelings which our

friendship has tended to

foster. It will cost me some support.

But it is right. I shall keep cool and

no doubt at the end be prepared for

either event."62 Two days later Hayes

was slightly more enthusiastic:

"You will be almost if not quite satisfied

with my letter of acceptance--especially

on the southern situation," he

told Bryan.63 And so, long

before anyone could know that there was go-

ing to be a disputed election and a

so-called "bargain," Hayes had already

made up his mind that his course would

be one of reconciliation and sweet

reunion of northern and southern whites.

How he would in turn get the

southerners to lay down the

"bowie-knife and the revolver," was not yet

apparent. One thing was certain, the

"idealistic" Hayes of 1867 had given

way to the "practical" Hayes

of 1877.

It should come as no surprise that the

letter of acceptance was not an

HAYES and RACE 159

altruistic state paper, but a carefully

worded sectional formula. In an art-

ful piece of political duplicity and

verbal ingenuity, Hayes picked his way

carefully through sectional quicksand as

he asked for the South the sym-

pathy of the nation:

Their first necessity is an intelligent

and honest administration of

government, which will protect all

classes of citizens in all their politi-

cal and private rights. What the South

needs most is peace, and peace

depends upon the supremacy of the law.

There can be no enduring

peace if the constitutional rights of

any portion of the people are ha-

bitually disregarded. A division of

political parties, resting merely upon

distinctions of race, or upon sectional

lines, is always unfortunate, and

may be disastrous. . . . Let me assure

my countrymen of the Southern

States that if I should be charged with

the duty of organizing an Ad-

ministration, it will be one which will

regard and cherish their truest

interests--the interests of the white

and of the colored people both,

and equally; and which will put forth

its best efforts in behalf of a

civil policy which will wipe out forever

the distinction between North

and South in our common country.64

Here then was the promise to the South,

given openly, long before any

thoughts of disputed elections were in

the wind. While not going into de-

tails, he promised clean government,

implying that carpetbag rule was

unclean. Without using the distasteful

phrase "local self-government,"

Hayes implicitedly promised that there

would be no more federal inter-

ference in southern affairs than there

was in northern affairs.

In spite of the assurances of the

acceptance letter, Schurz was uneasy

about the campaign in August of 1876

because the Democrats were say-

ing, "Governor Hayes's

administration will be but a continuation of

Grant's . . ."65 Then with pretended innocence Schurz said: "P. S.

Some

Democratic papers have ascribed your

letter of acceptance, part of it at

least, to me."66 The tendency of

the Democrats to identify Hayes with

Grant might explain, in part, the

determination of Hayes to disavow two

hallmarks of the Grant administration: a

disposition to keep peace in the

South with troops; and corruption in

office. In any case, such an approach

was an ill omen for the Negro. The

charge that the Negro was unfit for

citizenship and office holding would

make it incumbent upon any civil

service reformer to acquiesce in any

movement to unseat the unfit, Ne-

groes included. The real ambivalence in

the Hayes position lay in his de-

precation of the use of troops while at

the same time declaring that the

Civil War amendments had to be enforced.

One month before the elec-

tion, Grant's attorney general informed

Hayes of the wholesale nullifica-

tion of the Fifteenth Amendment by many

of the southern states and by

means not excluding murder.67 Yet,

on the next day Hayes called on James

G. Blaine and found that gentleman's

views on the South identical with

his own: "By conciliating Southern

whites, on the basis of obedience to

law and equal rights, he hopes we may

divide the Southern whites [italics

added], and so protect the colored

people."68

160 OHIO HISTORY

So the election of 1876 came with Hayes

determined, should he win the

prize, not to interfere in southern

affairs in return for southern obedience

to the laws respecting Negro rights. At

the same time, according to his

mail, he was made painfully aware of

southern lawlessness. And when he

thought that he had lost the election

both he and his wife expressed their

foremost concern for the "colored

people especially . . .," in the event of

a Democratic victory.69

Schurz continued to advise Hayes on the

Negro question,70 but the

clearest and best expression of the

Republican approach to the Negro and

the South after the election of 1876

came from an ex-cabinet member of

the Grant administration, Governor J. D.

Cox of Ohio. His sentiments

summed up essentially what was to become

official Southern policy not

only for the Hayes administration but

for all succeeding Republican re-

gimes until the turn of the century--if

not longer. The plan did not call

for abandonment but a moderation

of Negro political aspiration. Cox

wrote a letter to Hayes dated January

31, 1877, setting forth this view at

the request of Hayes who, no doubt, was

still casting about for a solution

to the troublesome and seemingly

everlasting Negro question. This letter

is worthy of analysis at some length.

Cox argued that the Republican party had

to take responsibility for

what many thought was the

"deplorable condition of things in the South."

The stark and naked truth of the matter

was, he argued, that the whites

of the South did not like the Negro to

be made their political equal. Con-

sequently, they tried to nullify the

post-war amendments by state legisla-

tion. The Negroes were then naturally

driven into the Republican party,

falling prey to the demagogue and

political adventurer. "Our mistake as

a party was in ignoring this fact,"

said Cox. But the Negro no longer

needed protection in a separate party

organization. Such separatism was

"now the cause of their greatest

danger." Cox reasoned somewhat erro-

neously that the whites of the South

would recognize the political equality

of the blacks if this did not threaten

to continue the rule of a class with

race as its distinguishing

characteristic. Continuance of the color line would

cause all of the southern states to take

the path of Mississippi--violent

repression of the Negro. In that

instance Negro rights would vanish. Cox

announced with an air of finality that

in the struggle of races, the weaker

would go down.

The salvation of the Negro, according to

Cox, depended upon doing

away with political division on the

basis of race and color. Cox was think-

ing about the viability of the

Republican party in the South, as well as

the welfare of the Negro. He thought it

possible to attract to the Repub-

lican party "a strong body of the

best men representing the capital, the

intelligence, the virtue and the revived

patriotism of the old population

of the South," on the basis of a

promise that they would "in honorable and

good faith accept and defend the . . .

rights of the freedmen." Cox would

get these "best men [whites]"

into the party through the medium of a

carefully scrutinized federal patronage.

In his effort to divide the southern

HAYES and RACE 161

whites, he failed to say how he would

get Negroes into the Democratic

party.

What would be the role and place of the

Negro in this new policy? Cox's

grand strategy in this regard was to

"moderate the new kindled ambition

of the . . . [Negroes] to fill places

which neither their experience, nor their

knowledge of business or of the laws fit

them for." The Negro would sim-

ply have to recognize "the fact

that the American white people have now

a hereditary faculty of self

government." Cox was also bitten by the eth-

nocentric bug which held that the art of

self government was bestowed by

God on the Anglo-Saxon alone. Be that as

it may, Cox never suggested

that the Negro should not vote. He was

simply to be less prominent in

office holding and political leadership.

Cox seemed to be saying that the

Negro was in too much of a hurry to get

too far, too soon, and with per-

haps too little: "Our fellow

citizens of African descent must recognize the

necessity of learning . . . patience

under disappointment and defeat."

Such was the way to end hostilities, to

call a halt to the open political

warfare among races in the South, to end

an era of revolution: "Such is

the picture that I have formed in my own

mind of the work your admin-

istration may do in the South."71

To all this Hayes responded: "On the

Southern Question your views and mine

are so precisely the same that if

called on to write down a policy I could

adopt your language."72

As the disputed election of 1876 neared

a solution in favor of the Re-

publicans, Hayes was impatient to play

the role of a statesman of reunion.

When Schurz urged him to approach

national aid to education and in-

ternal improvements with caution, Hayes

replied: "My anxiety to do

something to promote pacification of the

South is perhaps in danger of

leading me too far." Schurz was

afraid that big federal spending might

provide more opportunities for

corruption. As he saw the situation, most

legislators could not come within one

hundred miles of a railroad without

being corrupted. In the meantime Hayes

wondered if the healing pro-

cesses of time would not be better for

the South than "injudicious med-

dling." But he had made up his mind

about the future of troops in the

racial and political unrest in the

South: "There is to be an end of all

that."73

On February 18, 1877, Hayes had a

conversation with Frederick Doug-

lass and one other Negro. The President

reported that the Negroes ap-

proved of his views and that Douglass

gave him "many useful hints about

the whole subject." The Ohioan now

seemed as much a champion of equal

rights as he was a statesman of

political and emotional reunion between

northern and southern whites. "My

course," he said in the privacy of his

Diary, "is a firm assertion and maintenance of the rights

of the colored

people of the South . . . coupled with a

readiness to recognize all Southern

people, without regard to past political

conduct, who will now go with me

heartily and in good faith in support of

these principles."74

From the time of the letter of

acceptance to the inaugural address, the

Southern question played a larger role

in Hayes's thinking. The inaugural

|

162 OHIO HISTORY address was much more of a racial document than was the letter of ac- ceptance. He began by saying that the public desired "the permanent paci- fication of the country." Turning more specifically to the race question, Hayes continued: "With respect to the two distinct races whose peculiar relations to each other have brought us the deplorable complications and perplexities which exist in those States," the problem could only be solved with justice. Then Hayes said exactly what Schurz had advised him to say on the Southern question. The sentence was jerked up from the briny deep of political ambivalence: "And while I am duty bound and fully determined to protect the rights of all by every Constitutional means . . . I am sincerely anxious to use every legitimate influence in favor of honest and efficient local self-government, as the true resources of those States." Finally, he hoped that everyone would shed party and race prejudice and cooperate in the great work of reunion.75 |

|

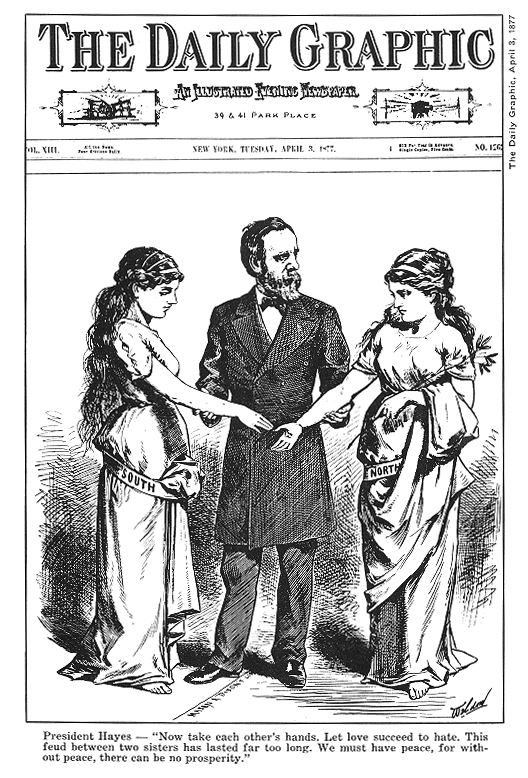

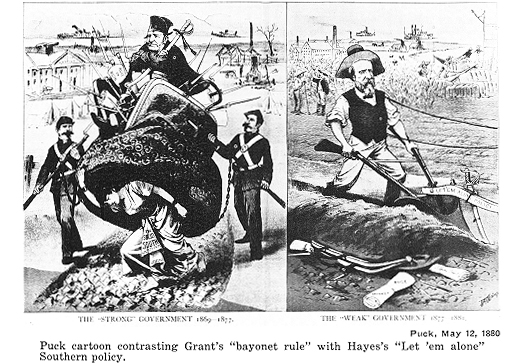

Puck, May 12, 1880 Puck cartoon contrasting Grant's "bayonet rule" with Hayes's "Let 'em alone" Southern policy. The Southern policy of Hayes, in summary, was first to put an end to the open political warfare between the races in the South. This warfare, in addition to taking a fearful toll in physical violence and intimidation of the Negro, kept open the Civil War breach between northern and southern whites. Secondly, Hayes would trust the "best white people" of the South to observe the three amendments relating to Negro rights. Third- ly, he would build up the economic prosperity of the region by education and liberal internal improvements of a national character. Finally, he would provide the South with honest local government. The last point |

HAYES and RACE 163

was crucial in its implications. One way

the President intended to achieve

this goal was through the use of the

federal patronage, judiciously and re-

sponsibly handled. A much more

significant implication of the final point

was that which called for "the

moderating" of the office-holding proclivities

of the Negro, as succinctly stated by

Cox. The leadership of the Republi-

can party in the South was to be put

into the hands of the "better class of

native Southern whites" who were

thought to be purer of soul than the

black and white Republicans of 1867.

This new native white leadership

would be recruited to the party by the

skillful use of the federal patron-

age. Never was it suggested that the

Negro not vote or that he leave the

party. The new requirement was that he,

because of his slavery-bred de-

ficiencies, should hand over the reins

of political initiative to the superior

race. The North and her politicians did

not sufficiently consider the possi-

bility that race prejudice was as much

responsible for the wrath of the

southern whites against the Negro as

were the real and imagined deficien-

cies of the recently emancipated slaves.

It remains now to take a brief look at

the Hayes policy in operation. The

President received many letters

expressing an opinion on his Southern

policy. More of them were in favor of

the policy than were against it. One

dominant theme ran through them and concerned

the subject of the divi-

sion of the Negro and white vote by the

creation of a new Republican

party composed partially of old line

Whigs of the South who would pro-

vide the nucleus of its leadership. Very

few, if any, of the letters spoke of

abandoning the Negro; rather, they

inquired how to protect him. Some

correspondents saw great danger in the

policy. They feared that Hayes

had been unduly optimistic in trusting

the southern whites with the pro-

tection of Negro citizenship and in his

hope that these whites would join

the Republican party.76

On the third of April 1877, Hayes

directed that federal troops be re-

moved from the State House of Columbia,

South Carolina. Seventeen days

later the same order was given for Louisiana.77

As the saga of active fed-

eral participation in southern

reconstruction came to an end, Hayes said:

The result of my plans is to get from

those States, by their governors,

legislatures, press and people pledges

that the Thirteenth, Fourteenth,

and Fifteenth Amendments shall be

faithfully observed; that the col-

ored people shall have rights to labor,

education, and the privileges of

citizenship. I am confident this is a

good work. Time will tell.78

Hayes now thought that he could turn his

attention to civil service re-

form.79 To one who had shown

a little uneasiness about what looked to

some like a surrender of the North to

the rebels, Hayes said: "I know

how sore a trial this business is to

staunch antislavery veterans like you.

I expect many to condemn [me]."80

Hayes could only hope that things

would turn out all right. A few months

after pulling the troops out of

South Carolina and Louisiana, labor

troubles elsewhere forced the Presi-

dent to use troops to put down disorder.81

164 OHIO HISTORY

A key maneuver in Hayes's attempt to

implement his Southern policy

was the appointment of Frederick

Douglass as Marshal of the District of

Columbia--a move which seems to have

reconciled both white and black

to the Hayes administration.82 Hayes

himself chose to look upon the ap-

pointment of Douglass as symbolic of an

intention to upgrade the Negro

in the eyes of the nation.83 Douglass

caused quite a stir after a bare month

in office when he made a speech in

Baltimore on the state of race relations

in the District of Columbia. He said

that Washington represented "a most

disgraceful and scandalous contradiction

to the march of civilization as

compared with many other parts of the

country." On May 18, 1877, the

New York Times said that Douglass

had spoken the truth and that such

truth had been spoken about the nation's

capital many times before, "but

never by a man whose skin was

dark-colored, and who had been appointed

to office in the District.84 There was an

immediate hue and cry for Doug-

lass' removal from office, but Hayes did

not bow to these demands.

In early September 1877, the President

took a nineteen day trip into the

middle South, presumably to obtain a

personal view of the results of his

racial policy. He visited Ohio,

Tennessee. Kentucky, Georgia, and Virginia.

In spite of much in his mailbag that

should have dampened his optimism,

he pronounced his policy a success and

was jubilant upon his return from

the tour. He had been heartily received,

if not in the deep South, and he

noted triumphantly in his Diary: "The

country is again one and united!

I am very happy to be able to feel that

the course taken has turned out

so well."85 Throughout the

tour his theme was that of reunion between

northern and southern whites, universal

adherence to the war amendments,

and racial harmony. To a northern

audience he called his Southern policy

"an experiment" which the

failure of the last six years demanded.86 But

when he was in former enemy territory

(Georgia), he swore that his policy

was not dictated "merely by

force of special circumstances," but that he

believed it right and just.87 He

tried to convince the people of the North

and the Negroes of the South that he had

not abandoned the freedmen

and that their rights could be protected

without federal interference. Turn-

ing to the Negroes in his Georgia

audience he said:

And now my colored friends, who have

thought, or who have been

told that I was turning my back upon the

men whom I fought for, now

listen. After thinking it over, I

believe your rights and interests would

be safer if this great mass of

intelligent white men were left alone by

the General Government.

This last phrase brought cheers from the

crowd, but whether by white

or black was not disclosed.88 Six

months after the commencement of his

policy Hayes was convinced that the

Negro was safer in the South without

the protection of the federal bayonets,

which he had withdrawn.89 He chose

to believe that "the white people

of the South have no desire to invade

the rights of the colored people."90

In his first annual message he defended

his removal of the troops from South

Carolina and Louisiana as a "much

HAYES and RACE 165

needed measure for the restoration of

local self-government and the pro-

motion of national harmony."91

The President's heart must surely have

leaped for joy when he received

a letter from Wade Hampton of South

Carolina, reassuring him of his in-

tentions to protect the Negro in his

rights and to coexist with Republi-

cans. But even here Hampton reported

that he was having trouble with

dissident members of his own party:

"My position here has been a very

difficult one, for besides the

opposition to me from political opponents, I

have had to meet & control that of

the extreme men of my own party."

If that were not enough to awaken Hayes

from his optimistic stupor, a

newspaper clipping which Hampton sent

him should have been sufficient.

The article called Hayes's attention to

the "Straight-Out Democrat" who

wanted nothing to do with Negroes or

Republicans, or southern whites

who fraternized with either.92

As soon as the midyear elections of 1878

drew near, the racial volcanoes

erupted again. According to a Negro

congressman from South Carolina,

the whites were again resorting to

violence and intimidation to prevent

Negro political participation. The

President could do nothing but lament

in his Diary that color was still

the hallmark of political division in South

Carolina: black Republicans and white

Democrats. He lamented, too, that

intelligence, property, and courage were

on the side of the whites while

the poor Negro was ignorant:93 "The

South is substantially solid against

us. Their vote is light ... A host of

people of both colors took no part . . .

the blacks, poor, ignorant, and timid

can't stand alone against the whites."

The "better elements of the South,"

in whom Hayes had placed so much

faith, were not organized. Only a party

division of the whites would im-

prove the situation but Hayes had no

definite plan to effect the change

and seemed reconciled to let nature take

its course.94 He had further cause

for dejection when he received a

thirty-signature petition from some Ne-

groes in Mississippi who wanted

financial assistance to emigrate to Kansas

to escape oppression.95 The

President could do nothing but report the un-

fortunate situation in the South to his Diary.96

Is it possible to render a final

judgment on the President's Southern

policy? The subject is a very

controversial one. Although he was aware

of its shortcomings, even after he left

the White House, Hayes never

doubted the underlying wisdom of his

Southern policy and that by it he

had allayed sectional and racial

bitterness in the face of strenuous opposi-

tion from both political parties.97

Contemporaries were more doubtful of

its success. A leading Radical

Republican, W. E. Chandler, felt that Hayes

had abandoned the white southern

Republican politician and the Negro

to the mercy of the

"redeemers."98 Frederick Douglass was grateful to the

man who had given him the highest office

held by a Negro in the federal

government up to that time, but later

accused Hayes of making a virtue

out of necessity.99 Others

reflecting on the past, pronounced the Hayes

policy a failure.100

166 OHIO HISTORY

Historians also have had their views on

the Hayes policy. John W. Bur-

gess said that Hayes's biggest struggle

with himself concerned the question

of whether he was deserting the black

man with his Southern policy.101

Charles Beard contended that

"President Hayes could not strike out boldly

had he desired to do so," because

he had to deal with a Democratic House

for four years and a Democratic Senate

for two years.102 On the other hand

there is no evidence to suggest that

Hayes showed any inclination to en-

force the laws already passed with

anything other than oral vigor.

Rayford Logan has judged President Hayes

rather harshly, accusing him

of abandoning the Negro, of complacency

in the face of the failure of the

South to live up to its part of the

alleged "bargain" in the compromise of

1877, and of aiding and abetting the

liquidation of the Negro from poli-

tics by suggesting qualified suffrage

based on education.103 Yet, all but

three of the southern states had fallen

to the "redeemers" before Hayes

took office. While the net result of the

Hayes policy was disfranchisement

of the Negro, it was fully ten years

after Hayes left office that the "redeem-

ers" felt sufficiently strong

enough to consummate their victory. The fail-

ure of Hayes to enforce the laws in

regard to civil rights should not be

construed as complacency or apathy on

his part. He certainly was concerned

about national impotence in this area.

However helpless to correct the

situation he may have felt, he by no

means viewed Negro disfranchisement

with indifference and approval. Logan

interpreted the President's sincere

concern for honest and efficient

government in the South as an indication

of his "approval of the curtailment

of the rights of Negroes by the resur-

gent South." Hayes did not suggest

education as a means of keeping the

Negro out of politics but as a vehicle

by which the Negro could ultimately

attain full citizenship.

Like most Presidents of this post-war

period, Hayes was either afraid or

unwilling to enforce the laws in regard

to the civil rights of Negroes. His

desire for white reconciliation and his

virtuous penchant for reform made

him unduly optimistic about the

likelihood of the southern whites protect-

ing Negro rights. What Professor Rubin

found to be true of the former

President Hayes during his tenure with

the Slater Fund [1881-1887] might

well apply to his presidency with

special reference to the Southern policy:

He was unduly optimistic in the face of

the repeated onslaughts of south-

ern white supremacy which sought

relentlessly during this period to push

the Negro into political oblivion.104

What final observations can be made

about Hayes? He saw Negroes as

members of a "weaker" though

not necessarily inferior race. He was defi-

nitely conscious of race difference. But

still he looked to the eventual inte-

gration of Negroes into American life.

He preferred to leave social equality, a

necessary condition for legal race

mixing, to time and natural

inclinations. Hayes said that it was better left

alone until both races learned to live

by the Golden Rule. Nevertheless, in

a rare reference or two, he intimated a

disinclination toward forced inte-

gration and also gave the impression

that biologically he preferred to leave

HAYES and RACE 167

racially asunder what God and nature

obviously had not put together. Yet

there were times when he demonstrated in

his thoughts and actions that

democracy could transcend the color

line.

While Hayes was by no means immune to

political motivation, little

opportunism can be detected in his basic

outlook on race. On the other

hand, it is difficult to reconcile the

obvious change in his attitude toward

the South from the time he was a Radical

(on Negro rights) gubernatorial

candidate in Ohio in 1867 to the time

when his name was prominently

mentioned for the presidential

nomination. It may be that his changed at-

titude toward the South represented a

sincere disenchantment with Recon-

struction.

The idea that Hayes abandoned the Negro

for southern support cannot

be proved. His big error, if one wishes

to call it that, was that he trusted

the South to keep its promise to protect

Negro rights, in the absence of

federal interference. That there was an

explicit agreement to this effect

seems improbable, because Hayes had

already determined to make this

approach long before anyone could

possibly have known that the election

of 1876 would be disputed. He had become

disenchanted with Reconstruc-

tion as early as 1875. More than this, a

reading of the Hayes correspondence

disposes one to believe that at least

some of those southern Whigs were in

earnest when they made the proffer of

protection for the Negro. What

really happened, it appears, was that

the better class of whites, the so-called

"natural leaders" of the

South, made a promise which was not really with-

in their power to keep. As things turned

out, if seems that the promise was

made without the consultation or

approval of the "red-necked" and un-

washed constituency or its leaders.

Ironically it was the rise of southern

Democracy, its roots dug deep into the

bedrock of Negrophobia, that con-

stituted the high tide of white

supremacy which in the 1890's inundated

Whig, Bourbon, and Negro alike.

As President, the problem of race was

ever before Hayes. He had not

been long in the White House before

matters of race threatened to domin-

ate his thinking. His determination to

bring about a reunion between

northern and southern whites seemed to

immobilize his obligation to en-

force the laws in the face of an

ever-recalcitrant South. Hayes was more dis-

posed to use sweet persuasion than brute

force. It may be that the Presi-

dent was impressed by the advice of

those who told him that in any con-

test between the Negro and the

Anglo-Saxon, the black man was destined

to be defeated. The seeming futility of

the struggle for basic change of

attitude in the South may have deterred

him from trying to enforce the

law in a stubbornly unwilling section.

Had not President Grant already

tried as much, and failed?

THE AUTHOR: George Sinkler is As-

sociate Professor of History at Morgan

State College.

|

Race: Principles and Policy of Rutherford B. Hayes by GEORGE SINKLER When Rutherofrd B. Hayes came to the presidency, the race problem was waiting in all its urgency. The subject was by no means new to him. As an Ohio Congressman, at the very beginning of his political career, he endorsed the Radical program of reconstruction. In unemotional terms this meant having a penchant for Negro rights and the preservation of the political power of the Republican party, though not necessarily in that order.1 A college classmate and lifelong friend. Guy M. Bryan of Texas, became a little uneasy about the Radical proclivities of Hayes. When the Recon- struction acts were passed, the two men began a correspondence that con- tinued long after Hayes left Washington. Bryan was to be the conscience of the white South continually working on Hayes. From 1867 on he sang but one monotonous, though effective song: The South wanted peace and reunion above everything. Only unscrupulous persons who stirred up trou- ble between the superior whites and the inferior blacks prevented the heal- ing of the wounds of war. The Negro would be better off if left to his former master. Bryan skillfully applied the argument of "kith and kin": Hayes let me appeal to you as one with whom I have so often broken bread, whose associations so long were identified with my own, whose blood and skin are from the same tree, . . . I beg of you to aid us in resisting the reckless manner with which the question of race is dealt with by the agitators at the South.2 I here say that Southern and Northern people are of the same blood and people, and that they and the Negro are not from the same stock. . . . The South is worth cultivating by the American statesman.3 Bryan was attempting to reach this northern heart by strumming the tune of ethnological kinship on the banjo of race. But Hayes does not seem to have been immediately affected by his pleas, at least not as far as official politics were concerned. He bravely flew in the face of anti-Negro sentiment in Ohio with a radical speech on August 5, 1867. He even ran for governor of that state on an extremely unpopular platform of Negro suffrage. He saw great merit in the Radical reconstruction plans of 1867. He declared that the war was fought for equal rights for all colors as well as for union. He agreed that troops were necessary in the South to protect both white NOTES ON PAGE 203 |

(614) 297-2300