Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

|

|

|

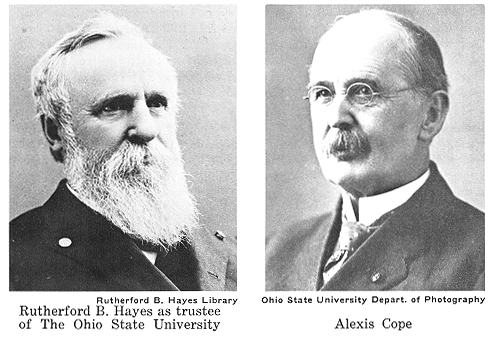

Rutherford B. Hayes and The Ohio State University by WALTER S. HAYES, JR. It was bitterly cold the day former President Hayes arrived in Cleveland in January 1893. He had come from Columbus and was in search of some- one to head the new manual training department for The Ohio State Uni- versity. Both as a member and as the president of the board of trustees he had been actively concerned with the establishment of a good manual training department for the institution. Snow fell and was blown by a wind that must have made the day seem even colder than the four to twelve degrees reported in the newspaper.1 Hayes did not let the weather keep him from his duties, but took a street- car and then proceeded by foot to University School where he had hoped to find the administrator the board was seeking. After staying overnight with his son Webb, he went to the train station Saturday afternoon, the fourteenth, for the return home to Fremont when he was suddenly stricken with a heart attack. Some stimulants were given to him in the waiting room, and against Webb's wishes he continued to Spiegel Grove where he died the following Tuesday.2 His long interest in the University had started when he became governor in 1868 and was still active at the time of his death. During the years he served as city solicitor, congressman, governor and president, Rutherford B. Hayes became familiar with many social prob- NOTES ON PAGE 206 |

|

HAYES and OSU 169 lems of the state and nation. After his presidential term he worked through private organizations to improve conditions in the United States in the fields of prison reform and education, especially Negro education and man- ual training.3 In the opinion of Governor Joseph B. Foraker this work made him an excellent choice for appointment to the board of trustees of The Ohio State University. Hayes had also been governor of Ohio, in 1870, at the time the original institution was founded under the name of the Ohio Agricultural and Mechanical College. At that time, he had appointed the first board of trustees, whose duty it was to locate the college, decide on the course of instruction, and choose the faculty. He is usually given little credit for his significant role in the founding of the University. The Morrill Act of July 2, 1862, provided the means for the various states to establish agricultural and mechanical colleges using the proceeds from the sale of public land. Each state was to receive 30,000 acres of land for each United States Senator and Representative, making Ohio's share 630,000 acres. Soon after passage of the act, interest was shown by the Ohio State Board of Agriculture, Governor David Tod, and others in taking advantage of the opportunity to start a college. Many times in the next seven and one half years, legislation supported by each new governor was formulated creating an agricultural and mechanical college. Each time efforts failed at some point. Western land did not sell well until the price was lowered in 1866. Also a number of cities and existing colleges wanted to share or totally acquire the funds and determine the location of the proposed college. By the end of the 1860's, however, most Ohioans agreed that the money should be used to establish one institution at a central location.4 |

170 OHIO HISTORY

In his first term, 1868-69, Governor R.

B. Hayes was as unsuccessful

as the previous governors in securing

legislation to establish the college.

The act of Congress of July 2, 1862,

specified that the states were required

to provide not less than one college

within five years in order to qualify

under the provisions of the bill. The

deadline had been extended five years

by Congress on July 23, 1866, but even

this time would expire soon.5

In his annual message of January 3,

1870, Hayes urged the Ohio General

Assembly to act quickly. He said that

Ohio had accepted the land grant

which had created the funds to establish

an agricultural and mechanical

college and warned that it must become a

reality on or before July 2, 1872.

He stated:

Much time and attention has been given

to the subject of the loca-

tion of the College. No doubt it will be

of great benefit to the county

in which it shall be established, but

the main object of desire with the

people of the State can be substantially

accomplished at any one of

the places which have been prominently

named as the site of the Col-

lege.6

This time the General Assembly responded

quickly. On January 12,

Representative Reuben P. Cannon of

Portage County introduced a bill

to establish and maintain an

agricultural and mechanical college in Ohio.7

The Morrill Act had specified:

The leading object shall be, without

excluding other scientific and

classical studies, and including

military tactics, to teach such branches

of learning as are related to

agriculture and the mechanic arts.

Hayes thought that the act should be

interpreted as broadly as it could and

that the best teaching facility possible

should result from it.8 The legis-

lature passed the Cannon bill on March

22, 1870, without limiting the

course of instruction. It left that

problem, along with those relating to the

location of the university and selection

of the faculty, to the trustees. The

act said that the governor should

appoint nineteen trustees, one from each

congressional district.

Hayes was interested in getting a board

of high quality and did not let

a man's views on politics or the ultimate

goals of the agricultural college

interfere with his appointments. Years

later, Thomas C. Mendenhall,

professor of chemistry at The Ohio State

University and editor of Alexis

Cope's History of The Ohio State

University, wrote, in the introduction

to the volume:

It was universally conceded at the time

that in the selection of the

members of the first Board of Trustees,

the men who were to deter-

mine the character and shape the policy

of the new institution, the

Governor (Rutherford B. Hayes) had shown

great wisdom, good judg-

ment and fairness to both sides of the

controversy (which had already

begun) as to whether it should be

"narrow" or broad and liberal in

its organization and sceme of

instruction .... Political affiliation had

been given little attention in making

the appointments and some of

HAYES and OSU 171

the strongest men on the board were

opponents of the Governor in

politics.9

The board as finally approved was a

group of men of great talent and

experience in the areas of agriculture,

education and public affairs. Eleven

of the nineteen had had some direct

connection with agriculture. Six had

had important connections with education

in the fields of teaching or ad-

ministration. Thirteen had been members

of the United States Congress,

the Ohio General Assembly, or both.10

With the appointment of the board

completed, attention was directed

to the business of locating the college,

deciding upon the course of in-

struction, and choosing the faculty. Hayes

called the first meeting for May

11, 1870. The work of the first board

was monumental. Tile members were

almost completely free in determining

the future of the new agricultural

college. At the first meeting, the board

elected as officers: Valentine B.

Horton, president; Richard C. Anderson,

secretary; and Joseph Sullivant,

treasurer. It then set about the main

business.

Joseph Sullivant, trustee from Columbus,

wrote a letter to the citizens

of Franklin County urging that they

raise money to attract the college for

their county. He told them that at least

$100,000 in land, buildings, and

cash would be needed.11 Propositions

were received from Franklin, Cham-

paign, Clark, and Montgomery counties.

Finally, on October 13, 1870, the

Neil farm located north of Columbus on

the Worthington Road was se-

lected as the site of the college. One

of the attractive features of the site

was a natural spring which could be used

as a source of water.12

After the site was chosen, the next step

was to decide upon the course

of instruction and determine whether the

scope of the institution should

be broad or narrow. Ralph Leete of

Ironton, in a letter to Hayes, said the

act of the General Assembly establishing

the agricultural college had not

attempted to bind down the trustees very

closely and that "in one sense

almost every branch of science has some

'relation to agriculture and the

mechanic arts,' for there is a unity in

all science."13 The quotation Leete

used was the only part of the original

Morrill Act of 1862 that defined

what the course of instruction of the

agricultural colleges should be. Hayes

answered that it was the intention of

the law to establish a new type of

educational institution for the laboring

classes. He wanted a broad, liberal

course of study available to the

students. The plan presented by Joseph

Sullivant, which was eventually adopted

by a vote of eight to seven, made

the new college liberal in the way which

Hayes had suggested.14

The Governor received letters from men

who hoped to become members

of the faculty asking that he use his

influence with the board in their

favor.15 He did have some

influence with the trustees since he had been

officially invited on September 6, 1870,

to meet with the board and partici-

pate in its discussions.16 One

appointment that he was actively concerned

with was that of president of the new

college. When Edward Orton was

being considered for the post, he was

afraid that the people of Ohio might

not want him to lead their state

agricultural college because of his radical

172 OHIO HISTORY

views. Orton's study of science at

Harvard had led him to doubt the literal

meaning of parts of the Bible; and,

while a professor of natural science at

Albany, New York, he must have expressed

these doubts to his Sunday

School class. To avoid a scandal, he

then resigned his teaching position and

came eventually to Antioch at Yellow

Springs, Ohio.17 Hayes and Al-

phonso Taft dispelled his fears and

persuaded him to become the first

president of the college.18

During the remaining months of his first

two terms and the one to fol-

low as Governor of Ohio, Hayes had

little to do with the Ohio Agricultural

and Mechanical College, or at least if

he did, such activity is not revealed

in his personal papers, official

letters, or records of the board. During the

next decade Hayes was fully occupied

with problems of a national and in-

ternational nature, but after stepping

down from the presidency he again

took up his work for the cause of

education and The Ohio State University,

as the college began to be called in

1878.

Governor Foraker appointed the former

President as a trustee in 1887.

Hayes was highly praised by those

interested in the University-citizens,

faculty, and students alike.19 He

received letters expressing pleasure at his

appointment and gratification in his

acceptance from several people, in-

cluding the first president of the

University, Edward Orton; trustee Lucius

B. Wing; secretary of the board of

trustees, Alexis Cope; and president

William Henry Scott.20

The letters exchanged between Hayes and

Scott and between Hayes and

Cope provide a great deal of information

about the activities of Hayes in

connection with the University. W. H.

Scott and Alexis Cope continued

to serve Ohio State in their respective

offices as long as Hayes was a trustee

and became his main contact. During the

period, Cope seemed to be the

man who held the University together. As

secretary of the board, he kept

the members informed by letter

concerning the school's problems and

activities when the board was not in

session. Because he was not directly in-

volved in student, faculty, or

administration affairs, he was in a position to

be more objective in his advice to the

trustees about current problems.

The University of 1887 had made much

progress since the days when

Governor Hayes had originally worked on

its establishment. In 1878, in

one of several acts reorganizing the

Board of Trustees, the Ohio Agricul-

tural and Mechanical College was renamed

The Ohio State University.21

The new name corresponded with the ideal

Hayes held for the institution

and probably pleased him very much. The

student body had grown from

254 to 344 in the ten-year period,22

and revisions of the curriculum had

resulted in the creation of new

departments and the abolition of others.

The early years of the University were

marked by sporadic conflicts be-

tween the agricultural interests of the

state and the desires of those, es-

pecially the trustees, who favored a

university controlled by others than

agrarians. This position usually

included a wish that Ohio State might

become much broader than merely a

college for farmers and mechanics.

Hayes joined the board at a time when

the conflict was especially vigorous.

HAYES and OSU 173

In dispute was the control of money

granted to the states by the federal

government under the Hatch Act of March

2, 1887. This act gave $15,000

annually to those states which had

established agricultural colleges under

the Morrill Act of 1862. The money was

to be used to establish agricultural

experiment stations in connection with

the colleges.

The problem in Ohio revolved around the

fact that, on April 17, 1882,23

the General Assembly had created an

agricultural experiment station as-

sociated with the University, but one

administered by a board of control

independent of the University's board of

trustees. The Hatch Act money

was thereupon claimed by each of the two

boards. It was the duty of the

Ohio General Assembly to decide who

should have jurisdiction over the

funds and to pass the necessary enabling

legislation so Ohio could receive

her share of the money.24

The board meeting of November 22, 1887,

was called to discuss the mat-

ter of cooperation between the boards of

the Agricultural Experiment

Station and the University. One obstacle

in the path of cooperation was

the governor's appointment of Joseph H.

Brigham to the board of con-

trol of the experiment station. Brigham

had been the one in the Ohio sen-

ate who had originally urged the

establishment of a separate board for

the Agricultural Experiment Station when

it was established in 1882 and

therefore was not at all popular with

some members of the University

board.25 At the November

meeting Hayes offered resolutions, which were

adopted, to the effect that friendly and

cordial relations between the two

boards were necessary and that a joint

meeting of committees of both

boards should take place, so that their

common goal of promotion of the

agricultural interests of the state

could be more nearly achieved.26 Hayes

thought that the full cooperation of the

University board would help gain

support for the University from friends

of the experiment station.27

The joint meeting of committees of the

two boards was held on Decem-

ber 8, 1887; this was followed by a

meeting of both boards in joint ses-

sion.28 Both sides expected

quite a fight, but Hayes, in the role of peace-

maker, took control of the meeting. In a

quiet, forceful way, he said that

the object of both boards was to serve

the public; that both had similar, if

not identical, aims; and that both

boards wanted the annuity from the

Hatch Act put to the best possible use

for the agricultural interests of the

state. He further stated that the Ohio

State University board of trustees

would be glad to see the Experiment

Station enlarge its activities and

that he was sure something could be worked

out. He then asked the mem-

bers of the board of control what the

trustees could do for them. His

forcefulness and tone stunned most of

the men present but seemed to be

very effective in laying the groundwork

for an agreement. The conferees

then drew up an agreement which reserved

certain land and equipment

for the experiment station and gave the

remainder to the University. Hayes

was satisfied that all points of

difference between the University and the

experiment station were settled and that

the farmers of Ohio would now

give their support to the University.29

174 OHIO HISTORY

This conference settled differences

until 1891. When the board of con-

trol met that year, the members were

still dissatisfied because of the lim-

ited amount of land allotted to them.

They voted to request the General

Assembly to permit the removal of the

Agricultural Experiment Station

to Wayne County. Also they expected the

University to buy the buildings

they had used on the campus for $12,000.

The trustees could not see why

they should buy the buildings since they

were already located on the cam-

pus and the trustees lacked the money or

possibly even the power to buy

them. Hayes was again called to

arbitrate this dispute. Agreement was

made to appoint committees representing

each side to settle property is-

sues and to leave the problem of

disposition of the buildings to the legis-

lature.30

Hayes's first two years on the board

were ones of giving advice on and

mediating problems of concern to the

trustees. This period of activity came

to an abrupt end because of his state of

shock following the death of Mrs.

Hayes in June 1889. Mrs. Hayes had been

stricken while he was on his way

home from a board meeting.31 For some

months he curtailed his activity,

and attended none of the board meetings

until early in 1890.

The business of the board of trustees

included many small day-to-day

problems and dealings in addition to

questions of major importance. Hayes

spent much time on seemingly minor

difficulties which could be resolved

in a short time. Most of his

correspondence on board matters dealt with

such items as requests for appointment

to the faculty, faculty and student

problems, disputes with the townspeople,

and gifts to the University. Most

of it is uninteresting and routine, but

a few examples will show his atten-

tion to details, a side of his

personality not so well known as his handling

of major problems and issues. These

minor incidents, of course, happened

throughout Hayes's entire board career,

and the chronology in most cases

is not important.

As might be expected in a university

town, disagreements arose between

the college community and the citizenry

of Columbus. One such dispute

involved a city thoroughfare across the

campus. In 1890 Neil Avenue ended

at Eleventh Avenue and then started

again on the north side of the campus.

Pressure had been applied over a period

of several years to have Neil Ave-

nue extended through the University

property.32 It was reported to Hayes

that citizens were quite upset over the

matter and threatened to have the

board reorganized, the University moved

out in the country, and funds

withheld from the institution by the

General Assembly if Neil Avenue

were not extended.33 The Board

resisted for a time, but eventually Neil

Avenue was extended.34

In 1891, the city was putting a trunk

sewer through the campus. As had

been predicted by the University people,

the sewer drained the "lakes &

spring" until both became dry. The

city placed Professor Frederick W.

Sperr, a mining engineer from the

faculty, in charge of the sewer con-

struction after he said that he thought

he could fix the damage and restore

the spring. Hayes was very much

concerned about the loss of the spring

and wrote Cope:

HAYES and OSU 175

We must not lose the springs! Too bad!

Spend all effort, time &

money to recover them that can be spent

judiciously.35

Hayes's strong position caused other

board members who had been doubt-

ful about spending money to restore the

springs to come to agree with

him. Hayes met with the city civil

engineer, Josiah Kinnear and members

of the city board of improvement. He

"had a good talk with them about

their damage-doing sewer." The city

was slow to fix the sewer, but by De-

cember 1892, Hayes was satisfied that

the springs were safe.36 It was a

rather minor problem, but much

present-day tradition would not exist

without Mirror Lake.

In 1890 Governor James E. Campbell

thought it would be a good idea to

increase the size of the board of

trustees. Hayes did not mind the idea of

enlarging it, but he thought the action

was being taken as a political move

to give the Democrats control of the

body. He did not want politics to

interfere with its functions and thought

the precedent might make gover-

nors change the number of board members

each time there was a change

of politics in the State House. Hayes

offered to resign so that, together with

the expiration of another Republican

board member's term, Campbell

could appoint two Democrats in their

places and could get a party major-

ity without increasing the number on the

board. The Governor would

thereby avoid setting a bad precedent.

The former President felt the long-

term good of the University was more

important than his board member-

ship and had acted on that basis.37

As it turned out, Campbell had not

intended to use a larger board to

political advantage, but since he did not

want to lose Hayes, lie kept the board

size unchanged.

An important part of Rutherford B.

Hayes's later career as a member of

the board of trustees of The Ohio State

University consisted of securing

legislation that would provide needed

funds for the University and seeing

that it would receive these funds

undiminished once the proper legisla-

tion had been passed. From its

beginnings to 1890 the University had not

been able to rely on a guaranteed income

from outside its own endowment.

The Ohio General Assembly had, from time

to time, set aside a specific

amount for the use of the institution,

but this had not become a regular

practice. Therefore the board could not

expect to get a specified amount

or even, at times, any money at all from

the state. Those responsible for

the continuation of the University

wanted a regular fixed annual income

that would allow the board to plan

future development.

United States Senator Justin Morrill

introduced a bill on April 30, 1890,

which would establish an educational

fund from proceeds of public lands

and railroad land grants to aid the

colleges that had been established under

the original Morrill Act of July 2,

1862.38 It would provide $15,000 a year

to each state to aid these colleges, and

the amount would be increased even-

tually to $25,000 a year, continuing as

long as funds were sufficient.39 This

bill was eventually expected to add an

equivalent of over $400,000 to the

permanent endowment of Ohio State.40

President Scott noted that a man-

ual training department could be

maintained under its provisions. Hayes

176 OHIO HISTORY

had a great interest in industrial

education and wanted to see a manual

training department established at Ohio

State. Scott told him that the bill

had also been introduced in the House,

where it had been referred to the

committee on education and thence to a

subcommittee of which J. D. Tay-

lor of Ohio was chairman. Hayes was

asked to write as strong a letter as

he thought proper to Taylor in order that

the bill might have a better

chance of passing before the close of

the session.41 Hayes wrote to Repre-

sentative Taylor:

I am an intense believer in industrial

education. The bill in aid of

the land grant Colleges will help in

that direction. Please give it your

attention and if you can

conscientiously, your support.42

The Senate passed the bill, and it was

then sent to the House. Once

again Hayes was asked to use his

influence and write to Representative

William McKinley, a member of the rules

committee which would deter-

mine the date the bill would be

considered. Scott asked Hayes also to write

his congressman and all others in the

House whom he knew personally.43

The bill passed the House on August 19

with the addition of an amend-

ment limiting the application of the

funds to instruction in English and

specific technical subjects. The Senate

concurred in the House amendment

the next day, and the approval by

President Harrison on August 30 made

the bill law.44

The trustees were then faced with the

important problem of allocating

their new wealth. The act itself limited

the choice somewhat by confining

application of the funds to instruction

in "agriculture, the mechanic arts,

the English language and the various

branches of mathematical, physical,

natural and economic science, with

special reference to their applications

in the industries of life, and to the

facilities for such instructon." Another

provision excluded any use of the money

for the erection or repair of

buildings.45 Scott thought

that it was too late in the year for the board to

add to the faculty so the money from the

first two installments should be

used for books and apparatus. Many

proposals were made suggesting the

creation of new chairs or the

acquisition of equipment for specific depart-

ments. Cope seemed to rely heavily on

Hayes for advice and influence as

he told him that the board would

postpone consideration of how the money

would be spent until he arrived, Hayes

having told the board he might be

late.46

An unexpected problem was brought before

the board of trustees just

at the time the acquisition of funds

seemed settled. The money bill pro-

vided that, in states where Negroes were

excluded from the agricultural

and mechanical college and there was a

separate college for colored stu-

dents established to teach them

agriculture and the mechanic arts, the

funds could be divided between the

college for white students and the col-

lege for colored students. This clause

had been intended to give Negroes

equal rights to financial support and

had been introduced by Senator

James L. Pugh of Alabama for the benefit

of the Tuskegee Institute of

that state.47 This provision

was seized upon by friends of Wilberforce Uni-

HAYES and OSU 177

versity as an opportunity to acquire

some of the money intended for The

Ohio State University.

Since Negroes had never been prohibited

and there were, in fact, a num-

ber of these students attending Ohio

State University at that time, the

"separate but equal" provision

of the bill did not apply. Hayes wrote to

President S. T. Mitchell of Wilberforce

telling him that he did not think

Wilberforce had a just claim to the funds,

but that he would support an

effort to equip and maintain an

industrial department at Wilberforce no

matter what the outcome of the decision

on the division of the funds. He

thought that Wilberforce could receive

more money from the state direct-

ly than in sharing the Morrill Act

funds.48

The next year, a bill to accept the

Morrill Act and turn all the proceeds

over to The Ohio State University was

passed by the General Assembly

on May 4, 1891.49 Thus, through the efforts of Hayes and other friends of

the institution, funds from the Morrill

Act were secured for the University

undivided.

Also in an effort to gain more financial

support for the University dur-

ing this period, a committee of the Ohio

State alumni association was

formed. It worked toward advertising the

programs of the school and cre-

ating public sentiment in favor of a

proposition to make a permanent pro-

vision for it by placing one-twentieth

of a mill on the grand duplicate of

the state for its support.

A bill to this effect was introduced in

the Ohio House of Representatives

on January 16, 1891, by Speaker Nial R.

Hysell. The prospects for its pass-

age at first seemed good. Soon, however,

opposition grew. Those who op-

posed it wanted to divide the proposed

funds between Ohio State, Ohio

University, and Miami University. The

fight over division of the state

money soon became linked with the

efforts to divide the new Morrill Act

funds between Ohio State and

Wilberforce. Opponents of Ohio State drew

together and a battle ensued. Hayes was

asked by President Scott to use

his influence with members of the state

legislature to cancel the effect of

those who wanted to divide these funds.

In the end, their attempt also

failed, and tax support was given the

University in the Hysell Bill, which

became law on March 20, 1891.50

The next year Senator J. Wilbur Nichols

made another attempt, by

introducing a bill, to have the funds

from the Hysell act divided. Secre-

tary Cope thought that Hayes again would

be the best man to present the

University's side of the case. This time

support for Ohio State also came

from the agricultural leaders of

Ohio--Joseph H. Brigham, Seth Ellis, Wil-

liam I. Chamberlain, and L. H. Bonham.

It was arranged with Senator

Clingman, chairman of the senate committee on

universities and colleges,

to give the friends of the University a

hearing on the Nichols bill in the

senate chamber on Wednesday evening,

February 17, 1892. Cope said that

he and Scott would have all the facts

and figures ready for Hayes to offer

to the legislature.51 In his

presentation Trustee Hayes argued that the

Hysell act was for agricultural and industrial

education including manual

training and that other colleges which

might share the money were not

178 OHIO HISTORY

agricultural and mechanical colleges. He

further stated that The Ohio

State University needed the source of

funds after losing the revenue from

the agricultural experiment station.

Increased enrollment also necessitated

greater financial support. Finally, Ohio

State was the only institution com-

pletely owned and controlled by the

State of Ohio and so the legislature

had a greater responsibility to it than

to other colleges. Hayes felt that

these arguments had been well received

and that he had made a good im-

pression for the cause of the

University.52

Cope reported to Hayes that since the

hearing, prospects for the defeat

of the Nichols bill had improved

greatly. "Your noble speech before the

Senate Committee has had a good effect

and the speech of Senator Nichols

was so mad and unreasonable that it

hurts rather than helps his cause."

Cope wrote later: "The Nichols bill

is dead." Senator Clingman said that

there would not be more than two votes

for it in the senate. In fact, the

bill was never reported out of

committee.53 This was another instance in

which Hayes's legal training and political

influence were vital assets in the

life and future growth of Tile Ohio

State University.

In 1891 authorities were surprised to

learn that Ohio State had been left

a substantial estate by the will of the

late Henry F. Page on his death, Oc-

tober 27. Since Page, a lawyer who had

lived in Circleville, had not had

any known connections or special

interest in the institution during his

lifetime, report of his bequest was, at

first, doubted. Before this time the

University had occasionally received

gifts and loans of books, apparatus,

and specimens for the various

laboratories and museums, but had never

received any large gifts like the Page

estate. The will was contested, but

the University was represented again by

the former President, since Hayes

had been well acquainted with the Page

family. The terms of the final

settlement awarded the entire estate to

The Ohio State University. By 1912

the gross amount received under the will

amounted to almost $217,000.

The board of trustees honored Page by

naming the new law building Page

Hall in 1902.54

During all the years Hayes served as a

member of the board, one prob-

lem continuously hung over the heads of

the members, sometimes openly

and at other times in the backs of their

minds. This was the decision as to

who should replace Scott as president of

the University. William Henry

Scott had become president in 1883 but,

even as Hayes joined the board in

June 1887, Scott tendered his

resignation. The board convinced him that

he should stay until someone else could

be found. This scene was repeated

several times in the following years,

but Scott continued as president until

several years after Hayes's death.

Considerable talk favoring Hayes as the

new president was started by

an enterprising reporter who wrote

falsely that the board of trustees was

considering Hayes for the position.55

Scott told Hayes that he expected to

resign and that he thought the former

President should be his successor.

"You would bring to the office a

rare combination of qualities which would

give strength to the institution both in

its internal administration and in

its relations to the State and the

general public." Hayes also received a let-

HAYES and OSU 179

ter from his old friend T. C. Jones, of

Delaware, whom head once ap-

pointed to the board of trustees. Jones

said he had heard talk of Hayes as

president, but knew he would not

consider that position. He was glad,

nevertheless, that Hayes was on the

board. A week later, The Lantern, the

student newspaper, noted that the

reports that Hayes had been asked to be

president were false."56 These

rumors must have reached his own family, for

he wrote in a letter to his daughter

Fanny:

Papa a College President! A most

respectable and useful station to

a man fit for it. But your papa, in the

words of your mother, "is no

fool." So rest as you were and

denounce the report with vigor.57

This seemed to end the matter and no

further mention of Hayes as a can-

didate for president of Ohio State was

noted.

On one occasion when the board members

were discussing the many

qualities which a president of the

University should possess, Hayes, having

sat in silence, commented:

We are looking for a man of fine

appearance, of commanding pres-

ence, one who will impress the public;

he must be a fine speaker at

public assemblies; he must be a great

scholar and a great teacher; he

must be a preacher, also, as some think;

he must be a man of winning

manners; he must have tact so that he

can get along with and govern

the faculty; he must be popular with the

students; he must also be a

man of business training, a man of

affairs; and he must be a great ad-

ministrator. Gentlemen, there is no such

man.58

Among some of the notable men considered

for the presidency were

Woodrow Wilson, then a professor at

Princeton, Willian Howard Taft,

who was Solicitor General of the United

States at that time,59 and Dr.

Washington Gladden, a very popular

Congregational minister in Colum-

bus and known throughout the country for

preaching the practical applica-

tion of the principles of religion to

current social problems. Gladden had

been approached on the matter at an

earlier time and had not been inter-

ested in taking the position. Later,

however, he had shown interest in the

University and Cope felt that he might

consider the presidency. President

Scott, Cope, and others concerned would

have been pleased to have Glad-

den become the new president,60 even

though they did not know how he

felt about the position, personally.

In the early part of 1892. Hayes and

Cope called on Gladden to inquire

about his possible acceptance of the

presidency of The Ohio State Uni-

versity. The minister expressed his

willingness to accept the offer if the

salary could be raised to $5,000. The

salary at that time was limited to

$3,000 by state law and could be raised

only by an act of the legislature.

It was agreed to leave the matter open

so that the board could act freely.61

Hayes had many meetings with Gladden,

the board, and the state legis-

lature, but the legislature refused to

raise the salary limitation because

many of the members did not approve of

the liberal Dr. Gladden as presi-

dent. Since the hoard did not want to

lose the support of the legislature

on University matters, it abandoned hope

of making Gladden Scott's suc-

180 OHIO HISTORY

cessor.62 Two years later, in

1895, James Hulme Canfield became the fourth

president of the University. At last

Scott's efforts to be relieved of the

presidency were a success.

The one educational subject former

President Rutherford B. Hayes

stressed most was manual training. His

thoughts on the subject are obvious

from his writings and many speeches.

Whenever he had a chance, he spoke

in its behalf. Showing the strength of

his conviction, Hayes wrote:

I would aid no institution which does

not provide Industrial Educa-

tion. Like other men with hobbies I am

radical. My plan is essential.

It is the corner stone. With it an

institution must succeed. Without it,

it must fail.63

Hayes wanted all students to have some

manual training so that, in ad-

dition to their general personal

improvement, all would be able to make

a living with their hands, by skilled

labor if necessary. One of his own

sons attended manual training school. In

the education of the Negro,

Hayes hoped training of the hands would

help raise his standard of living.

He felt the establishment of an

industrial department at Ohio State would

also gain support for the University among

the farm element that was

suspicious of any tendencies to teach

impractical theory. Between 1888

and 1891 Hayes therefore proposed and

the board of trustees passed sev-

eral resolutions supporting the

establishment of a manual training de-

partment.64 He spoke on

industrial education before the Ohio House of

Representatives in 188865 and together

with other board members met

with the appropriations committee of the

two houses in 1889.66 Each time

he was hopeful of favorable action, but

it was not until 1891 that the state

legislature was receptive to the board's

proposal.

As has been mentioned, in March 1891,

the legislature passed the Hy-

sell Bill, which gave Ohio State an

annual levy of one-twentieth of a mill.

The money was not immediately available,

but an act of the General As-

sembly of May 4, 1891, authorized the

board to issue certificates of indebt-

edness to finance the construction of

several new buildings, and the money

repaid from the expected proceeds of the

Hysell act.67 Hayes was pleased

at the liberality of the General

Assembly. The following day, May 5, a

board meeting was held to consider the

matter, at which time he offered

the following resolution:

Resolved, That the interests of the university require the

erection of

three buildings, one for the manual

training department, to cost with

equipment, not to exceed $45,000; one

for a geological museum with

accomodations for the library, to cost

not to exceed, with furniture

and fixtures, $75,000; one for an

armory, assembly room and gymnas-

ium, to cost not to exceed $40,000,

complete; said buildings to be be-

gun in the order in which they are named

herein and as soon as prac-

ticable.68

This important resolution was passed

without dissent.

A committee was appointed to visit

manual training departments in

|

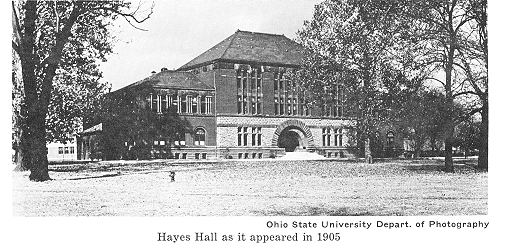

HAYES and OSU 181 other universities and the manual training schools in Toledo, Chicago, and St. Louis. It was also instructed to collect information to help in the plan- ning for equipment and buildings at Ohio State.69 A Columbus architect, F. L. Packard, prepared some preliminary plans and sketches for the pro- posed manual training building. He appeared before the board at the June 22 meeting and explained his plans to the members. The final selec- tion of an architect and completion of the plans for the building were re- ferred to Hayes, who was also given the responsibility of selecting the equip- ment and faculty for the department.70 On July 22, 1891, Hayes made his oral progress report to the board of trustees. He said he had visited the new manual training building at Cleve- land and had engaged Packard as architect, who then showed his plans, which were accepted, to the board. Hayes's motion to locate the manual training building 200 to 600 feet southeast of the chemical laboratory was approved. The announcement calling for sealed bids on work to be done on the building was sent out September 12, setting a deadline of noon on October 14, 1891. The bids were opened at a board meeting on that day |

|

and the contract for the structure was awarded to the low bidders, Nichols and Carr of Columbus.71 The board honored Hayes by unanimously adopt- ing the following resolution at the November 17 meeting: Resolved, that the manual training building now being constructed shall be named and known as "Hayes Hall," in recognition of the un- tiring labors of President Hayes toward its establishment, and his devo- tion to the cause of industrial education.72 The former President was especially pleased that the unanimous resolu- tion came from a board made up of four Democrats and two Republicans and was proposed by Dr. Schueller, a Democrat.73 As construction proceeded, Hayes had little to do in connection with the building itself. Secretary Cope made occasional reports on its progress, notifying him as each step was completed. Cope seemed a little disappointed |

182 OHIO HISTORY

at the outside appearance of the

building, but felt it was well built and

substantial. On his own visits to tile

campus, Hayes expressed pleasure with

the new structure.74

After the problems of construction had

been solved, the selection of a

capable man to head the department

became the primary concern. Scott,

Cope, and Hayes seemed to have agreed

originally that a man should be

chosen as soon as possible so that he

could help make decisions on the archi-

tectural design of the building. This

plan did not work out because a satis-

factory candidate could not be found in

time. The board members inter-

viewed many prospective administrators

and sometimes asked for advice on

the building at the same time, as was

done in the case of George S. Rider

of the University School in Cleveland.75

Another candidate, Henry C.

Adams, principal of the high school in

Toledo, was chosen to head the

manual training department at a salary

of $2,250, but he surprised them

and rejected the offer.76 Hayes utilized

his own contacts to find out about

the qualifications of different

candidates. He had relied on letters from his

sons Birchard and Scott to help him form

an opinion about Adams.77

Birchard lived in Toledo and knew

Adams's reputation, and Scott had been

a student at the high school under

Adams. The search continued without

success for some time, and Hayes died

before the board elected Arthur L.

Williston director of the manual

training department in 1893.78

Hayes was honored by the board in

November 1892, when he was elected

president of that body. He was

completely surprised by the board's choice.

He had moved and cast his vote for

reelection of Godfrey, not knowing that

the other members had planned ahead of

the meeting to elect him rather

than Godfrey. Godfrey received one vote

and Hayes the rest.79

The last few days before his fatal

illness Hayes spent working on Uni-

versity affairs. He rose early on the

morning of January 9, 1893, to take the

train for Columbus. Thinking ahead to

the board of trustees meeting, he

wrote in his Diary just before

leaving Fremont, "Let me be pure & wise

and kind in all things."80 The meetings

of the following two days were to

be the first and, as it turned out, the

last meetings over which he presided.

They were rather routine except for the

discussion of law courses for the

next year for which $1,500 was

allocated, as proposed by Hayes.81 His last

Diary entry reports a call he and Cope made on Governor

William McKin-

ley on the twelfth. The board's

secretary recalled later that after they had

seen the Governor, Hayes expressed the

hope that McKinley would someday

be President. They then went to the

station and Hayes boarded the train

for Cleveland. In that city he hoped to

find a man who would head the

manual training department, but he

became ill and was taken back to his

home in Fremont, where he died on

January 17, 1893, at the age of sev-

enty. His last mission had been one in

the service of Ohio State University

concerning his favorite project, manual

training.

The faculty and board of trustees each

held special meetings to commem-

orate his death. Memorials and tributes

were read and plans made to send

representatives to the funeral service.

Classes were dismissed the day of the

HAYES and OSU 183

funeral. The Lantern published a

special memorial issue. The University

community felt a real loss. Hayes had

been a faithful trustee, working hard

to better The Ohio State University.82

After leaving the Presidency, he could

have retired to his Spiegel Grove

home, but his interest in education and

reform caused him to continue

working for such causes until his death.

"He quietly and unselfishly gave

his last twelve years of life to the services

of his fellow men--the prisoners,

the Negroes, the Indians, the poor and

down-trodden."83

Cope appreciated the services Hayes

performed for the University also.

The year before his death, just after he

had helped defeat the Nichols bill

which would have divided the Hysell

fund, he presided at a banquet at the

University. Cope wrote to him

afterwards:

You did the University inestimable

service in coming down to pre-

side at the banquet. My heart smites me

sometimes when I think how

much we have drawn upon your time and

strength to tide us over the

difficulties which beset us.

I trust the reward will come in this

world in the overflowing love

and respect of those you have so nobly

aided. If it does not, I know

it will in the great hereafter.84

The interest Rutherford Hayes held in

the University began before its

beginning. He considered himself to be

"a founder--perhaps the founder"

of The Ohio State University85 and

was widely recognized as the man who

put it on a solid base. The historian,

Edwin Earle Sparks, said, in a com-

mencement address in June 1907, "I

regard this campus and the walls of

this institution, largely the creation

of Governor Hayes."86 A part of the

faculty resolution on his death stated:

Deeply interested in the State

University from its formation he exer-

cised a controlling influence in

moulding its character by his judicious

appointments of its organizing boards of

trustees. Becoming himself a

trustee of the University after

returning from the Presidency of the

United States, he has, during the last

six years, rendered invaluable

service to the institution; bringing to

its counsels a knowledge of men

and affairs acquired during a long

period of distinguished public life,

and adding to this a faith in the future

of the University and a devo-

tion to its welfare and expansion which

can never be forgotten.87

Hayes wanted Ohio State to develop as a

school where a practical, as well

as a liberal education, would be

available to all. To a great extent, this

goal seems to have been realized and

though there have been many changes

since his time, much of the basic

foundation established by Hayes remains

even today.

THE AUTHOR: Walter S. Hayes, Jr.,

a financial analyst for the General

Electric

Company in East Cleveland, is a great-

grandson of Rutherford B. Hayes.

|

|

|

Rutherford B. Hayes and The Ohio State University by WALTER S. HAYES, JR. It was bitterly cold the day former President Hayes arrived in Cleveland in January 1893. He had come from Columbus and was in search of some- one to head the new manual training department for The Ohio State Uni- versity. Both as a member and as the president of the board of trustees he had been actively concerned with the establishment of a good manual training department for the institution. Snow fell and was blown by a wind that must have made the day seem even colder than the four to twelve degrees reported in the newspaper.1 Hayes did not let the weather keep him from his duties, but took a street- car and then proceeded by foot to University School where he had hoped to find the administrator the board was seeking. After staying overnight with his son Webb, he went to the train station Saturday afternoon, the fourteenth, for the return home to Fremont when he was suddenly stricken with a heart attack. Some stimulants were given to him in the waiting room, and against Webb's wishes he continued to Spiegel Grove where he died the following Tuesday.2 His long interest in the University had started when he became governor in 1868 and was still active at the time of his death. During the years he served as city solicitor, congressman, governor and president, Rutherford B. Hayes became familiar with many social prob- NOTES ON PAGE 206 |

(614) 297-2300