Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

|

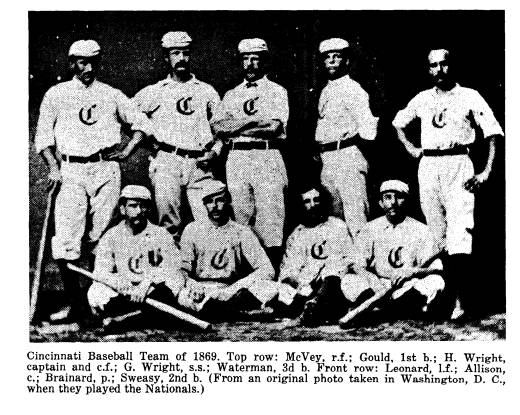

?? The ?? Reds of 1869 by DAVID QUENTIN VOIGT We are a band of baseball players From Cincinnati City; We come to toss the ball around And sing to you our ditty; And if you listen to the song We are about to sing, We'll tell you all about baseball And make the welkin ring. The ladies want to know Who are those gallant men in Stockings red, they'd like to know. When the victorious 1869 Red Stockings were on tour, they introduced themselves by singing the team's official song, set to the tune of "Bonnie Blue Flag." Each verse lauded a different player. NOTES ON PAGE 68 |

|

14 OHIO HISTORY |

|

|

|

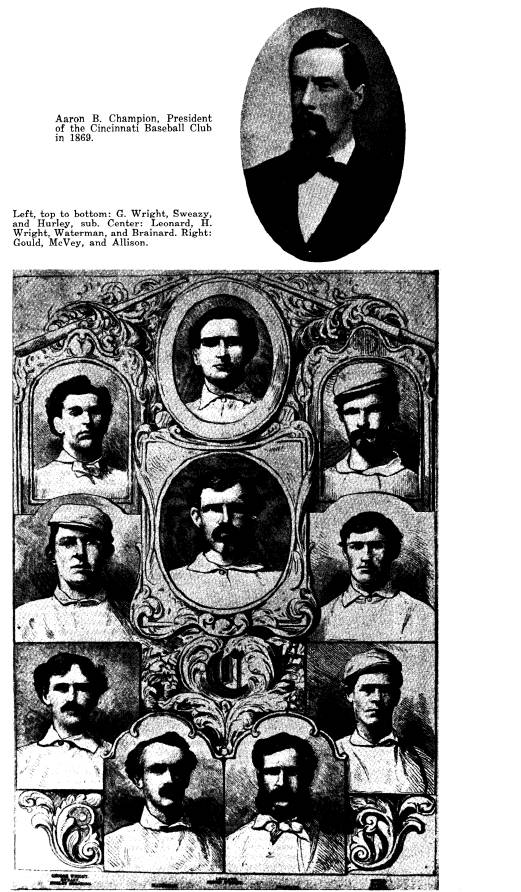

If the image of major league baseball today is somewhat eclipsed by the growing popularity of rival sports, at least America's "national game" has earned the respect due to old age. For this year the clock ticks off the one- hundredth year since the first professional team supposedly took the field. As the story goes (and given half a chance any old time aficionado can re- late it), it was the Cincinnati Red Stockings of 1869 who fielded the first professional team and who, by ruthless determination won eighty-one straight victories, demonstrated the efficiency of the new mercenary method of player recruitment.1 From that point on it was but a step to the birth of the major leagues and to a long period of their stability which is only now being rudely shattered by franchise changes and plans to restructure the major leagues into four divisions. Like most baseball myths the truth is strained in the telling and often there is a manufactured quality about them. For example, baseball's birth is wrapped up in a myth packaged by an official commission which met at the turn of this century to inquire into the game's origins. In most uncriti- cal fashion the commission took the dubious word of one of its aged mem- bers who claimed that his boyhood chum and lifelong hero, the late Civil War General Abner Doubleday, had "invented" the game one afternoon in 1839. A similar type myth of "immaculate conception" is used to ex- plain the sudden appearance of professional baseball in Cincinnati in 1869.2 To begin, there is the claim that the 1869 Cincinnati Reds were the first professional players, an interpretation that hinges on the meaning of the word "professional." When applied to players, it usually refers to one's ability to earn a living playing the game. Using this yardstick, the 1869 Reds were far from first. In the early 1860's Al Reach, star infielder for the Philadelphia Athletics, was paid a straight salary for his talents, and most prominent teams of his day had at least two salaried stars on hand to back up their amateurs.3 Moreover, Harry Wright, the "father of profes- sional baseball" and later player-manager of the 1869 Cincinnati Reds, wrote in his diary of 1866 that the Athletics were also paying $20 a week to three others. And in 1868 with nonchalant acceptance, sportswriter Henry Chadwick listed the names of ten professionals on the Brooklyn Eckfords.4 Furthermore, in that era the straight salary route was not the only ave- nue to baseball professionalism. In addition, the National Association labeled players "professionals" if they worked for "place or emolument."5 |

|

CINCINNATI REDS 15 Thus, quite a few players of the 1860's qualified under a system which of- fered lusty lads "honorary" jobs that called for good pay for almost no work. In the case of the New York Mutuals such jobs were to be found in the Coroner's office; and, in Washington, the Treasury Department was reputed to be "the real birthplace of professional baseball." Elsewhere, in similar fashion, local civic leaders did their part so that their home teams could compete in an age of bitter inter-city rivalry.6 Still another road to professionalism was the time honored custom of passing the hat at important games and dividing receipts among stars. A common practice in Washington, Philadelphia, and Brooklyn, stars often got as much as $200 for a day's work. And a popular variation of the theme was the benefit game held to honor stars; in 1863 Wright pocketed $29.65 in this manner, some of the money coming from the sale of souvenir tickets with "a picture of a Professional on each."7 Not surprisingly, such payoffs evoked criticism from amateur elements who charged that gamblers were contributing to the professionalization process by bribing players to throw games. By 1869 the ugly word "hippo- droming" was widely used to describe games suspected of having been rigged in advance by gamblers. In 1870 the New York Mutuals became the center of controversy when it was revealed that one of their stockholders, William Marcy ("Boss") Tweed, had contributed $7500 to the team. As |

CINCINNATI REDS

17

one outraged amateur protested at the

meeting of the National Association,

Tweed "probably got his money back

again."8

With "professional" baseball

an entrenched reality by 1868, skilled play-

ers found themselves in an enviable

bargaining position with clubowners

because they could threaten to go

elsewhere. In blasting such "revolvers"

for jumping "without so much as a

by your leave," Chadwick demanded

restrictions, pleading: "Since

professional baseball is a business," it must

be pursued "honestly and openly and

above board."9

Partly in response to such demands, and

mostly in the interest of team

stability and profits, Harry Wright as

player-manager of the Reds elected

to sign all his 1869 Reds to full season

contracts and to challenge even

the best eastern teams. But this was not

a sudden decision, and the bearded

Wright who had spent most of his life

playing, managing and studying

field sports, first as a cricketer and

then as a baseball player, knew what

he was doing. The sons of a noted

cricket professional, Wright and his

brother George, were already ranked among

the best ballplayers in Ameri-

ca. Moreover, Wright knew where the best

men were and was confident

of his ability to obtain them.10

The most unusual aspect of Wright's

dream of team professionalism was

that this would be the first time a

western club dared such a thing. In the

recent past other clubs had taken the

grand tour, but they had been estab-

lished eastern teams, like the

Washington Nationals or Brooklyn Eckfords.

That a lowly western team might gain

prestige from such a venture helped

to sell Wright's plan to local backers.

Certainly the city of Cincinnati was

growing and some leading citizens were

anxious for a national identity that

would transcend the somewhat snide

epithet of "Porkopolis."

Among the leading boosters of Wright's

plan was a twenty-six year old

lawyer, Aaron B. Champion, who was the

organizer and newly installed

president of the Red Stockings. Anxious

to promote the commercial growth

of Cincinnati, Champion viewed baseball

as a vehicle for advertising the

city and its products. In pursuit of

this plan in 1868 he talked his directors

into spending $11,000 to beautify the

ball field and to equip the players.

By standards of the day this was big

money, but late in the year Champion

brashly promoted another $15,000 through

the sale of new stock for the

express purpose of buying the best

ballplayers in America. To insure top

quality flesh for his money, Champion

sought to lure the nine New York

Clipper medal winners of 1868 to Cincinnati. In its modern

application,

such a plan would mean a novice baseball

promoter was trying to buy up

the members of the major league all-star

team. To be charitable, such an

idea, even in 1868, was unsophisticated.

In those days players were un-

fettered by reserve clauses that tie

today's men to single clubs, and thus

were free to go anywhere. But, in fact,

most stars had strong personal at-

tachments to their clubs, and the

prospect of relocating in a town like

Cincinnati was not overly enticing.11

Nevertheless, then as now, stars liked

to get more money and the Cin-

cinnati offer provided a nice wedge for

prying more money from their own

clubs. Thus, it was not long before an

unscrupulous pair pulled this trick;

18 OHIO HISTORY

they first accepted the Cincinnati

offer, and then rejected it after more

money was forthcoming from their parent

clubs. Naturally this treachery

upset Champion who had publicized their

acceptances and was obliged to

eat crow. After much blustering and

fruitless legal maneuvering, Champion

made his wisest decision. He entrusted

the scouting to Manager Wright.

Certainly few men of the time knew more about

the baseball talent

market than Wright, who had the

reputation of being "unapproachable

in his good generalship and

management."12 Then, as later, Wright was

guided by his belief that fans would pay

to see well trained and well be-

haved players perform. Already he had

tested the principle to his satisfac-

tion, for in a single season he had

transformed the newly established Red

Stocking club into the pride of

Cincinnati. In a few weeks after receiving

his new assignment, Wright completed the

job of recruiting his 1869 dream

team. As Wright saw it, only a few

changes were necessary since the 1868

team already had six men good enough for

the task. Besides himself, he

retained catcher Douglas Allison, first

baseman Charles Gould, dubbed

"the bushel basket" for his

sure hands, third baseman Fred Waterman, out-

fielder Calvin McVey, and the bearded

pitching ace, Asa Brainard. In

rounding out the team Wright snared

outfielder Andy Leonard, second

baseman Charles Sweasy, and utility man

Dick Hurley from the ranks of a

hometown rival, the Buckeyes. Then for

insurance Wright raided the Mor-

risania (N.Y.) Unions, picking up his

brother George a Clipper medalist,

for shortstop, and Dave Birdsall for

outfield duty. Thus, in efficient fashion

Wright marshalled the elite team that he

proposed to lead on a nationwide

tour, and accepted challenges from any

host team that promised the Reds

as much as a third of the daily gate

receipts.13

Normally the club existed on receipts,

and the biggest capital expense

was salaries. Contracts ran from March

to November, and some records

show George Wright drawing top pay at

$1400. Next came Harry at $1200;

Brainard $1100; Waterman $1000; Sweasy,

Gould, Allison, Leonard and

McVey, $800 apiece; and Hurley $600. And

even if George Wright's later

claim is correct, that Harry, instead,

received $2000 and he $1800, the fact

remains that the first all-salaried team

was a modest investment.14

Nevertheless investors thought the sum

was awesome and their fears

forced Wright to think in terms of big

gate receipts toward which he di-

rected his spartan training regimen. A

tireless drillmaster and clever

teacher of tactics, he welded the

players into an efficient machine and won

high praise from Chadwick who said that

only when other managers fol-

low his lead, "may they expect a

similar degree of success."15

Along with his emphasis on training,

Wright demonstrated a flair for

shrewd showmanship in his choice of team

uniforms. In sending instruc-

tions to the club tailor, Mrs. Bertha

Bertram, bright red stockings were

ordered to complement the white flannel

shirts and pants and the spiked

Oxford shoes. A happy choice, it gave

the team a colorful appearance that

delighted local fans. Like the club's

proud record of victories, its colorful

hose became its totem; and long after

Wright disbanded this team, other

Cincinnati teams adopted the red

stockings as a trademark. Indeed, Cin-

20 OHIO HISTORY

cinnati's current major league entry

carries on the tradition, although the

nickname is now the Redlegs.16 Meanwhile

in their own day the first Red

Stockings stirred national comment for

garishness, and in 1871 Chadwick

credited the team for setting a new

style trend for their "comfortably cool,

tasteful" dress, "the color of

the stockings giving the hue to the entire

suit."17

Like Wright, the publicity-seeking

Champion found his niche as a club

mythmaker. It was he who arranged for a

full-time reporter from the Cin-

cinnati Commercial to keep fans

well supplied with fodder on the team's

movements. Already in 1869 baseball was

a two-dimensional spectacle, one

being the world of the playing field and

the other of newspaper columns

on the game. In 1869 the job of

publicizing the Reds as the first pro team

fell to Harry M. Millar, and he always

licked the hand that fed him. His

flood of copy, punctuated with

admiration for Wright and high praise for

the stars, built the legend of the Reds

as a spartan superteam, a credit to

the ethic of hard work.

It was Millar who accurately forecast

the long winning streak when he

described the team as "so well

regulated that it should avail itself of its

capabilities of defeating every club

with which it contests." Millar's fore-

cast came on the eve of the club's

departure for the East, where its reputa-

tion would be tested by the best teams in

the land. Until then the Reds

had fattened on weaker rivals and local

"picked nines" in fashioning a

string of seven straight wins. Moving

east the team added ten more vic-

tories before invading metropolitan New

York for its moment of truth.

It was mid-June when Wright's team came

to town and Champion's pro-

motional campaign was in high gear,

stressing the novelty of the audacious

western Cinderella team daring to

confront eastern titans in their home

yards. The test came on June 14 when,

before a partisan crowd of 8000 at

Brooklyn's Union Grounds, the Reds

downed the powerful Mutuals, 4-2.

It was the victory Champion had counted

on, and when his announcement

hit Cincinnati, joy reigned and streets

filled with cheering fans. "Go on

with your noble work," rang a

congratulatory telegram. "Our expectations

have been met."18

Unruffled by the lavish praise, Wright's

team continued to defeat eastern

powers and to attract ever larger

crowds. In Washington the players met

President Grant, "who treated them

cordially and complimented them on

their play." Later at the game a

writer commented that the Reds "drew

the most aristocratic assemblage . . .

that ever put in an appearance at a

baseball match."19

As the team rode the crest of its

victory wave, more sophisticated journals

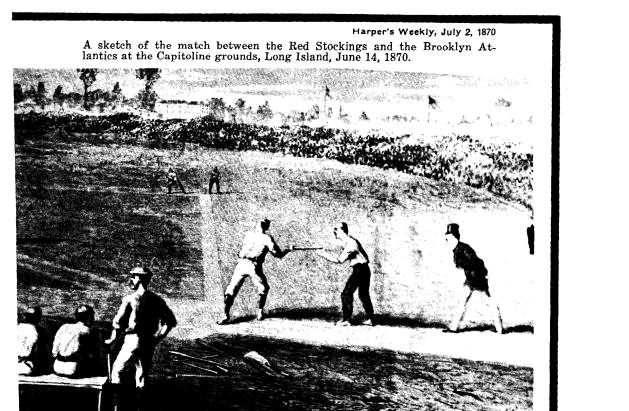

took note. Harper's Weekly published

half a page of drawings of the

"picked nine" and included a

team picture showing grim, young faces

fortified by beards and sideburns. But

such praise was merely a warm-up

for the homecoming reception that

awaited in Cincinnati. Returning home

late in June, the Reds found a joyous

welcome and were drowned in local

pride that today would certainly be cited

for its unsophisticated hero-wor-

ship. At last the Commercial tried

to dampen its excesses, complaining that

CINCINNATI REDS

21

some rabid fans hardly understood the

game, citing one aged enthusiast

who admitted that he knew little

"about baseball, or town ball, now-a-days,

but it does me good to see those

fellows. They've done something to add

to the glory of our city." And a

companion put a finger on the cause of

such joy--"Glory, they've

advertised the city--advertised us, sir, and helped

our business, sir."

The glow lingered for weeks, but the big

moment had come the first day

when Champion accepted the gift of a

twenty-seven foot bat from a local

lumber company on which were painted the

names of all the heroes. All

day long Champion and the team had gone

from one fete to another, with

the climax coming at a gala ball that

lasted until early morning. There,

as he relaxed under the "Welcome

Red Stockings" streamer, the giddy

Champion allowed that at the moment

being president of the Reds was

the highest office in the country.20

After this celebration came a long

homestand with the Reds maintaining

their winning pace, although once they

were tied by the "Haymakers" of

Troy, New York. The official account of

this blotch on the team's spotless

escutcheon is a hurried blur, with Troy

being blamed for unsportsmanlike

conduct. As the tale goes, it was the

fifth inning with the score tied at 17-

all when the Troy captain quarreled with

the umpire. In a moment the

fray grew hot and the captain, joined by

the Troy president, cursed the

umpire and ordered the Haymakers off the

field. The effect was to turn

the crowd into a riotous mood, and a

brawl was averted when the umpire

forfeited the game to the Reds. At the

time the Commercial blamed it on

the New York gamblers, including

Congressman John Morrissey, the king-

pin of the lot. As the Commercial explained,

Morrissey stood to lose $17,000

if the Reds won, so it was he who

ordered the phoney sit-down. But others

thought differently, and later the

judiciary committee of the National As-

sociation ruled the contest a tie,

disallowing the forfeit.21

Otherwise, the Reds continued their

winning ways and staged a trium-

phant march through the West, enabling

them to close the 1869 season

with fifty-seven victories, a tie and no

defeats. In reading the official ac-

count, one is left with the firm opinion

that the feat was entirely due to

clean living, hard work, and shrewd

capitalism.

But if the achievement was Olympian, the

men who did it were patently

human. To read Harry Wright's diary

account is to share the mixed joys

and understand his problems in managing

this team of "supermen." Often

the team drew well, like the time 15,000

saw them play in Philadelphia,

or the 23,217 total for six games in New

York which returned $4,474 in

receipts. On the other hand there were

days when the club might better

have stayed home. In Mansfield, Ohio,

the club collected a mere $50, and

in Cleveland, $81. And when the team

arrived for a game in Syracuse,

New York, Wright was horrified to find a

live pigeon shoot taking place

at the ball field, where the outfield

grass was a foot high and the fence in

shambles. Upon inquiring, Wright learned

that nobody remembered sched-

uling the game, so the Reds and their

manager settled for the therapeutical

consolation of a salt bath at a local

spa for a cost of thirty-five cents.

|

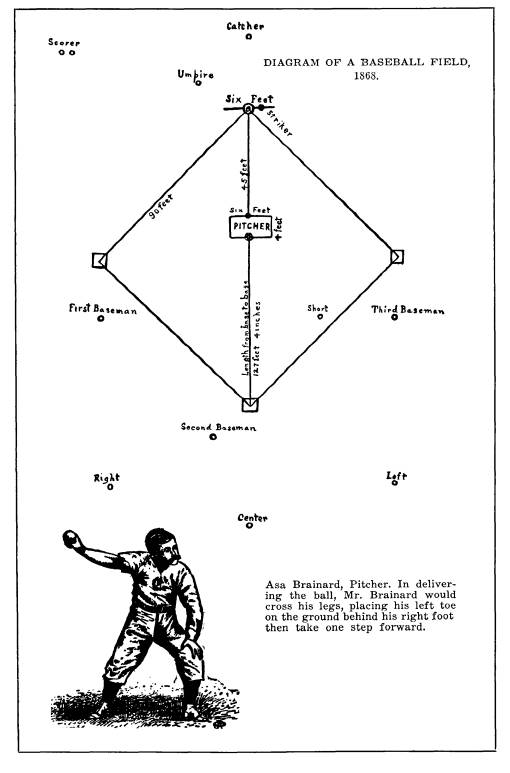

22 OHIO HISTORY Hard after this disappointment came another in Rochester. Arriving there Wright found the park in good shape with an eager crowd on hand. But when the game was barely underway, a freak cloudburst soaked the field. Wright was equal to the challenge; determined to save the receipts, he and his men "got some brooms, swept the water off, and put sawdust in the muddy places and commenced playing again." Wright's diary also dispells the Sunday school decorum of the team. Al- though well-trained and disciplined, his boyish players were unruly. Often they straggled, missed trains, and ducked practices. The worst offender was pitcher Brainard, but even brother George cut practices. Brainard's odd personality led him into a variety of troubles. This was tough on Wright, for the pitcher was a key man and the style of the time called for one pitcher to work nearly every game. This demand was less rigorous than it sounds since the pitching distance at the time was only forty-five feet and pitchers threw underhanded. But it was Wright's lot to be saddled with a good pitcher whose hypochondria always included some vague ailment. Brainard needed cajoling constantly, and when the best arguments failed, Wright pitched himself, using a baffling "dewdrop" to hold down the enemy while his mates slugged harder than usual. If Brainard's miseries were not enough, he was also a night owl. Once when the exhausted team detrained in Buffalo at 4 A.M., everybody will- ingly took to bed except the pitcher and his pal, Fred Waterman, who chose to roam the streets looking for action. Yet withal Wright knew that Brainard was one of the best hurlers in the country, a man who battled like a demon in tough contests but sometimes loafed when the going was easy. Because of his negligence, Wright often threatened him with fines. On top of all this, Brainard was also a character; in George Wright's words, he got "odd notions." Once during a game a wild rabbit scampered across |

|

CINCINNATI REDS 23 the diamond passing in front of the pitcher, who forgot batter and runners and threw the ball at the bunny. The impulsive act cost the Reds two runs while the rabbit escaped unscathed.22 Nor did Wright's troubles end with personality problems. A constant vigilance was necessary to keep the uproarious team off bottled spirits. Al- though Wright was a temperance man, he was wise enough to know that he lived in an age when the ability to hold hard liquor was a measure of masculinity. That Wright fought a losing battle against John Barleycorn was apparent, for in 1870 the Commercial announced that the personal contracts of the Red Stockings terminated November 15, and "No player will be accepted next year who will not contract to abstain from intoxi- cating beverages at all times, unless prescribed by a physician in good standing."23 With enough internal problems to vex a missionary, Wright also faced the external problem of growing envy among opposing teams. As victories mounted, the Reds became the target of mounting jealousy. Partisan news- men whipped up emotion, and after the Reds' march through New York, Gotham papers sneered at the team's brand of professionalism. One editor argued that any player who works for pay ought to be "disgraced," or fired if he holds a commercial job since all are easily bribed. It was argued that all players were at "the beck and call of the sporting men, who bring them into the ring, game-cock fashion, and pit them against each other for money."24 Meanwhile other detractors disparaged the "eclectic" character of the Reds. This implied that a respectable team ought to use only home grown players, a ridiculous charge that not only failed to consider the mobility of most Americans, but also the "eclectic" character of Wright's rivals. Yet Wright was powerless to fend off the attacks, and he consoled himself with |

24 OHIO HISTORY

the hope that it would take at least a

year for rivals to catch up with his

team in organization and training.

But Wright was wrong. After winning the

first twenty-seven games in

the 1870 campaign, his team faced

another moment of truth on June 14.

In Brooklyn, a likely place for the rise

and fall of baseball dynasties, the

avenging team was the Brooklyn

Atlantics. Playing at the Capitoline

Grounds, the Reds suffered their first

defeat since late 1868 (after winning

81, 84, 87, or 92 straight, depending on

how one counts informal games),

by a score of 8-7. With the game tied

5-5 in regulation time, Wright might

have settled for a draw, but with

Champion's approval he chose to gamble

on an extra inning victory. At the end

of the tenth, the score was still tied.

The Reds took the lead in the top of the

eleventh, but Brooklyn pushed

winning runs across in their half, aided

by errors by second baseman Sweasy.

Lacking none of the sportsmanlike spirit

of future Brooklyn crowds, this

one went for the Reds with a vengeance.

One over-eager fan jumped on

the back of outfielder McVey as he

attempted to field a ball, thus assisting

one of the Brooklyn runners in scoring

in the eleventh. And after the

victory a mob of fans made the team run

a gauntlet of jeers and catcalls

before the Reds made it to their

carriage. With the team riding in an open

carriage, the ordeal lasted all the way

to the hotel where Champion in the

safety of his room broke down and wept.

Later he wired the Commercial:

"Atlantics 8, Cincinnatis 7. The

finest game ever played. Our boys did

nobly, but fortune was against us.

Eleven innings played. Though defeated,

not disgraced."25

The wide publicity given this defeat

testified to the rising tide of public

enthusiasm for big-time baseball. For

this the Reds can take only part

credit for the boom was afoot before

1868 and continued after the Reds

slipped from the top. Indeed, it is

remarkable how quickly fans abroad and

at home lost interest in the Reds after

they lost. This was a lesson later

owners would learn well, but it seemed

harshly brutal to Champion. Be-

cause of falling attendance and another

loss at the hands of Chicago, he

faced a stockholder revolt that cost him

his presidency. With a new regime

committed to austerity, even though the

books balanced, Cincinnati was

no place for big-time baseball and the

Wrights knew it. Hard after Cham-

pion's defeat, the Wrights announced

their decision to move to Boston

where more money awaited both, and where

Wright would build the

Boston Red Stockings into the perennial

champions of the first major

league.

With the Wrights' departure, Cincinnati

baseball reverted to modest

amateur proportions,26 although

the city later regained major-league status

and ever after traded on its reputation

as the birthplace of professional

baseball. And certainly the Reds were

the catalyst which speeded the process

of baseball's commercial growth.

THE AUTHOR: David Quentin Voigt

is a professor in the Sociology

Department,

Albright College, Reading,

Pennsylvania.

|

?? The ?? Reds of 1869 by DAVID QUENTIN VOIGT We are a band of baseball players From Cincinnati City; We come to toss the ball around And sing to you our ditty; And if you listen to the song We are about to sing, We'll tell you all about baseball And make the welkin ring. The ladies want to know Who are those gallant men in Stockings red, they'd like to know. When the victorious 1869 Red Stockings were on tour, they introduced themselves by singing the team's official song, set to the tune of "Bonnie Blue Flag." Each verse lauded a different player. NOTES ON PAGE 68 |

(614) 297-2300