Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

Science and Democracy:

A History of the Cincinnati

Observatory, 1842-1872

by Stephen Goldfarb

The Spy Glass out on the hill

Is

now entirely finished.

The distance twixt us and the moon

Is sensibly diminished.

When Mitchel looks, it comes near

He sees the hills and trees

Which most conclusively doth prove

That 'tis not made of cheese.

--Cincinnati Enquirer, 18451

The Cincinnati Observatory, housing an

eleven-and-one-half-inch refractor

telescope, was opened for viewing in the

spring of 1845. The circumstances

by which the observatory came to be

built constitute an exemplary story

of science and democracy in the middle

decades of the nineteenth century,

as are also the efforts, and ultimate

failure, to make it become an important

research institution. Justification for

the observatory from its inception in

1842 was found in a curious blend of

localism, nationalism, and a belief

in democracy and the progress of man.

The monies for the telescope and

construction of the observatory were

raised by public subscription, making

this the

first astronomical institution of its size to

be built without either

royal or governmental patronage. As a

symbol of civic pride, the observatory

was viewed as an outstanding achievement

by a city freshly cut from the

wilderness. John P. Foote, who served

both as secretary and president of

the Cincinnati Astronomical Society,

expressed this sentiment later in 1855

when he wrote: "We [the citizens of

Cincinnati] gave an example to the

old and wealthy which they ought to have

given to us, who were young

and poor. . . . Cambridge and Washington

have now larger telescopes than

that of Cincinnati, which at the time it

was mounted, was the largest in

America. . . ."2

The observatory also was built as a

symbol of the intellectual ambition

of the young country. In 1842 when the

project was conceived, this nation-

NOTES ON PAGE 222

THE CINCINNATI OBSERVATORY 173

alistic spirit was well expressed by its

foremost proponent, Ormsby Mac-

Knight Mitchel, when he told an audience

that he was "determined to

show the autocrat of all the Russias

that an obscure individual in this

wilderness city in a republican country

can raise here more money by volun-

tary gift in behalf of science than his

majesty can raise in the same way

throughout his whole dominions."3 Along

with this nationalistic feeling

came a very self-conscious belief in the

newly won democracy. Mitchel often

boasted that he was "the

first democratically elected astronomer" in that the

constitution of the society required the

post of director of the observatory,

like all the offices in the society, to

be elective. One of the major purposes of

establishing the observatory was the

increase of general knowledge and the

resultant uplifting of the educational

level. For Mitchel, from the knowledge

of astronomy came proof of the existence

of God. Throughout all his

lectures and popular writings there was

constant reference to the beauties

of the heavens reflecting the glory of

God.4 As astronomical discoveries

were made, man was freed from older superstitions,

thus advancing the

progress of mankind.

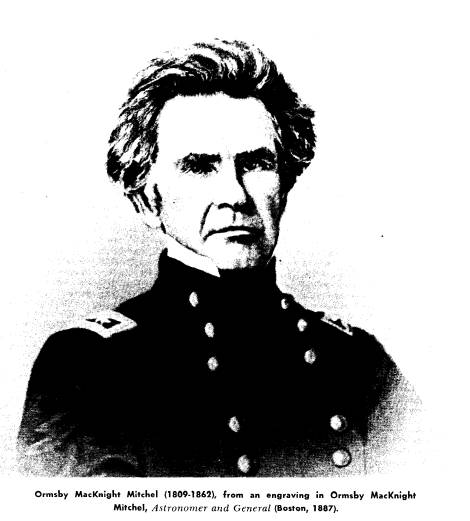

The main force behind the establishment

of the Cincinnati Observatory

was its first director, O. M. Mitchel.

Though born in Kentucky, Mitchel

was reared in the Ohio towns of Lebanon

and Xenia and received a college

education at West Point. After

graduating in 1829, he became an assistant

professor of mathematics there but

resigned his commission in 1831 after

a brief tour of duty in Florida and

moved to the then largest city in the

West, Cincinnati. Mitchel practiced law

for a few years before teaching

in Cincinnati College, an institution

which had been founded in 1819 and

reestablished in 1835. He was made

Professor of Mathematics, Natural

Philosophy and Astronomy and was able to

supplement his income during

the summer months as chief engineer of

the Little Miami Railroad.5

Because his teaching aroused some

interest in Cincinnati, Mitchel was

invited to give a lecture in the winter

of 1841-42 to the Society for the

Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. The

subject he selected was "The Stability

of the Solar System," and his

lecture was well received by both the audience

and the press. As a result of his

success, Mitchel consented to give a series

of lectures for the society.6

The reception of these lectures must

have been very gratifying to Mitchel

for, "On the first evening,"

he later wrote, "my audience was respectable,

on the second evening my house was

filled, and on the third it was over-

flowing."7 Mitchel gave his last

lecture of the series near the end of April

1842, at which time he suggested

that the citizens of Cincinnati purchase

a telescope. "I have resolved to

raise seven thousand five hundred dollars,"

he explained, "and my plan is . . .

. [to] Divide the entire sum into three

hundred shares of stock, each share

being valued at twenty-five dollars."

He further explained that the ownership

of a share made one a member

of the Cincinnati Astronomical Society,

which entitled him to "the privilege

of examining these beautiful and magnificent

objects through one of the

finest glasses in the world."8

During the next few weeks, Mitchel, when

|

not busy with his duties at Cincinnati College, visited individuals of "all classes" soliciting money for the telescope. About twelve hundred persons had to be approached in order to sell the three hundred shares, for most of the stockholders subscribed to but a single share.9 The Cincinnati Astronomical Society was organized to support the activi- ties of the proposed observatory in late May 1842, and by early June the full amount had been subscribed. The society wanted Mitchel to travel to Europe to procure the proper telescope and to become acquainted with European astronomers and observatories. An additional $1000 was raised for his personal expenses, and $7500 was subscribed for purchase of a telescope.10 Mitchel's journey lasted well over three months, during which time he visited the optical shops of both London and Paris, but he finally had to go to Munich to obtain an "object-glass" that would meet the demands of the society. At Merz and Mahler Mitchel made a conditional purchase of an |

THE CINCINNATI OBSERVATORY 175

eleven-and-one-half-inch retractor much

like, but slightly smaller than, the

one in use at the Imperial Russian

Observatory at Pulkowa, the largest

refractor then extant.11

While in Europe, Mitchel met some

important scientists of the day in-

cluding Francois Arago in Paris, Richard

Sheepshankes, Sir James South,

and the Astronomer Royal G. B. Airy in

England. Mitchel worked as an as-

sistant to Airy at Greenwich for two

weeks to learn the techniques of

observational astronomy--until then he

had had no experience with the

practical side of the use of a large

telescope. Mitchel's mathematical ability

must have served him well, but it seems

extraordinary that he felt confident

enough to contract for a telescope which

he did not know how to operate

properly.12

Mitchel returned to Cincinnati in the

early part of October, and on

the 14th "an unusually large

audience" heard him report on his European

journey. After another brief flurry of

solicitation, money from new

memberships and some large donations

increased the funds available to

the society to $14,000. With this sum available, the society decided

to

finalize the purchase of the telescope

from Merz and Mahler at a

cost in excess of $9000.13

The instrument took over a year to be constructed

and shipped to Cincinnati, during which

time an observatory had to be

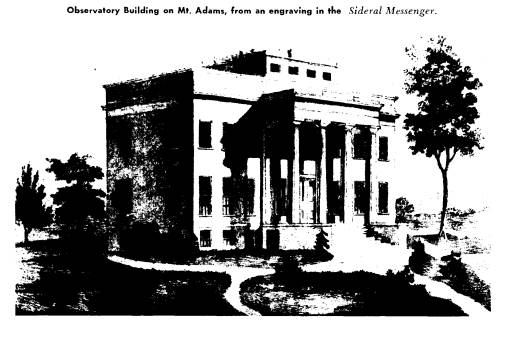

built and furnished. The problem of a

site was quickly solved by Nicholas

Longworth's generous donation of four

acres of land on a hill in eastern

Cincinnati.14

In 1844 prestige of the society rose

still higher when John Quincy Adams

was persuaded to speak at the

observatory's cornerstone-laying ceremony

on November 9. In honor of the speaker,

who gave a two-hour oration,

the name of the hill on which the

observatory would stand was changed

to Mount Adams.15

The construction of the observatory,

delayed by cold weather, was a

very trying experience for Mitchel.

Constant lack of money dogged the

project from the beginning; when not

actually lecturing, Mitchel was

either supervising the work or raising

funds for the workmen's pay. Many

of the materials and much of the work

done on the building were donated

in exchange for shares in the society,

and this accounted for much of the

increase in membership from the original

three hundred to the eight

hundred about which Mitchel often

boasted. In spite of the large amount

of free labor and materials, Mitchel

incurred considerable personal debt

in order to complete the observatory.16

The telescope arrived in Cincinnati in

January 1845, and by the time

of the society's annual meeting in April

it was mounted and in good work-

ing order. The annual address to the

society was given by Mitchel's former

law partner, E. D. Mansfield, who

praised the study of astronomy for its

practical uses as well as its value in

the education of the general public.

The report of the board of control

overflowed with the satisfaction of

having finished an important

undertaking, while Mitchel's report as director

was filled with a detailed explanation

of the problems of mounting the

176 OHIO HISTORY

telescope and a brief description of the

first observations made with the

large refractor.17

During most of its life the society had

financial problems which, more

than any other single matter, were the

continual concern of the board

of control. The society was plagued with

periodic crises during which the

officers and members in a burst of

activity would attempt to raise needed

funds. The first of the financial crises

occurred in 1845 when Mitchel

informed the society that he had

assumed over $3000 of the cost of erecting

the observatory building; in addition,

the society itself was in debt about

four hundred dollars. The need to

liquidate this debt was the major con-

cern during the winter of 1845-46. It

was decided to ask each member

for an additional five dollars, and

notices to this effect were sent out.

By April 28, 1846, the committee on

subscriptions was able to report "that

more than $4000 has been

subscribed" which was sufficient to pay all the

debts.18

The next financial crisis occurred in

the following year when Mitchel

announced to the board of control that

"the additional instruments required

for the observatory were still wanting

and that the building was still

unfurnished." A committee which

reported on the needs estimated that an

additional $3200 was necessary. The

figure was broken down in this

way: transit circle, $2000; clock, $300;

room for transit circle, $400; and

$500 to finish the observatory

building.19 The fund-raising efforts of the

society on this occasion were not so

successful as before, though the situa-

tion was much improved by the loan to

the society of a transit circle by

Alexander Bache of the Coast Survey.20

The observatory building was

finally finished, and the addition for

the transit circle was built, but

Mitchel had to wait until the summer of

1849 before the financial resources

for a proper chronometer could be found.

The society's financial problems,

however, were never really solved. By

spring 1850, some further debts had

accumulated, and the need for a

regular salary for Mitchel's assistant

was also reported. After rejecting a

motion to disband the society, members again

were able to raise additional

funds by selling stock and soliciting

large grants from wealthy individuals.21

By June 20, $2000 had been raised for

the liquidation of debts, and $1000

a year for the next three years had been

subscribed to pay for operating

expenses; the largest single item was

$600 for the assistant's salary.22

As originally conceived, the purpose of

the observatory was two-fold:

first, the amusement and education of

the citizens of Cincinnati, and second,

scientific research.23 When the telescope was

first erected, the equatorial

room was open to members of the society

from 3 P. M. to 10 P. M.

every

day of the week except Sundays and

Mondays.24 No doubt because he

was unable to carry out his own

scientific observations, Mitchel was able

to prevail upon the society to change

the original visiting days. Beginning

on November 1, 1846, the telescope was

available for viewing by the mem-

bers on Thursdays, Fridays, and Saturdays

only.25

In March 1852, Mitchel asked that the

observatory be closed to the

|

THE CINCINNATI OBSERVATORY 177 public and that the instruments be used exclusively for "scientific purposes," for which he felt a transit, instead of an equatorial, mount would better serve his needs. This he realized "would require the consent of the stock- holders" who would have to "relinquish a considerable portion of their rights in favour of the advancement of science."26 The question of exclusive use of the observatory for science languished for two years, but in the early months of 1854 the society yielded to Mitchel's wishes. With the observatory closed to the public, Mitchel was finally free to carry out his observations without having to be bothered by visitors.27 Except for a single meeting in 1855, the minute book of the society records no meetings between the election meeting held in June 1854 and a series of meetings held in 1859. The problem before the society during these 1859 meetings was the removal of the observatory from Mount Adams where, as Mitchel explained, "the smoke issuing from the chimneys of the surrounding factories had the last two or three years become so great as to preclude for more than half the time any observations." At the same meeting Mitchel announced that he had accepted an offer to become the director of the Dudley Observatory in Albany, New York.28 Two offers of suitable sites and financial aid were received by the society, but because the members could not come to any agreement with Long- worth over disposal of the Mount Adams land, the observatory remained at its almost useless location. In 1860 Mitchel went to Albany, though he still retained the directorship of the Cincinnati Observatory, leaving his assistant Henry Twitchell in charge. When the Civil War broke out, Mitchel was quickly made an officer in the Union Army, no doubt because of his West Point training. After successful campaigns in Tennessee and |

178 OHIO HISTORY

Alabama, he died of yellow fever in the

fall of 1862 at Beaufort, South

Carolina.29

After Mitchel's death, the observatory

entered a period of even greater

inactivity. Twitchell, a former sailor,

soon resigned, transferring responsi-

bility to a Mr. Davis who was permitted

to use the telescope and to live

in the observatory on the condition that

he maintain the building.30

In 1867 a revival of interest in the

observatory took place. Alphonso Taft,

later to become Secretary of War in the

Grant administration, was then the

prominent new president of the

Cincinnati Astronomical Society. Money

was raised, and a plan was worked out

whereby an operating budget was

provided for three years. After support

was assured, Cleveland Abbe, who

had just spent two years with Otto

Wilhelm von Struve in Russia, was

elected to the directorship. Abbe

assumed his post in June 1868, but instead

of pursuing astronomical interests, he

began to work on weather predic-

tions with the aid of meteorological

data collected by telegraphed reports.31

The problem of the site was still not

solved. It was evident that the

telescope was useless on Mount Adams,

for the early smoke problem had

become even worse. In 1872 the

observatory became part of the University

of Cincinnati, and through a generous

gift of financier John Kilgour the

observatory was moved to its present

location on Mount Lookout. The

society as a private body then ceased to

exist.32

In the story of the Cincinnati

Observatory some of the problems of

American science in the middle decades

of the nineteenth century appear in

microcosm. The rhetoric of democratic

enthusiasm which assumed that

correct motivations could be substituted

for special training justified the

large expense of the telescope and

observatory for the essentially esoteric

activity of astronomical research. In

the long run, though, the rationaliza-

tions of popular amusement, social

usefulness, and Christain edification

were not enough to sustain the

observatory.

There is indeed something touching and

absurd about the whole observa-

tory scheme. On one hand, there is the

magnificence of the telescope, and,

on the other, the failure of Mitchel to

use this superb instrument for any

important scientific work. Over four

years passed between the time the

society received the telescope and that

when the observatory was equipped

with supporting instruments. One wonders

whether the membership of the

society or even Mitchel envisioned the

full ramifications of their decision

to build the observatory. Mitchel's own

development from the enthusiastic

amateur of 1842, affirming the

importance of the study of astronomy for

the benefit of mankind, to the

professional of 1852, who wanted exclusive

use of the telescope for scientific

purposes, parallels the currents of emergent

professionalization then prevalent in

America. The history of the Cincinnati

Astronomical Society clearly exhibits

the problem of reconciling the aims

of science with the popular goals of

democracy.

THE AUTHOR: Stephen Goldfarb is a

doctoral candidate in the history of

science

and technology program, Case Western

Reserve University.

Science and Democracy:

A History of the Cincinnati

Observatory, 1842-1872

by Stephen Goldfarb

The Spy Glass out on the hill

Is

now entirely finished.

The distance twixt us and the moon

Is sensibly diminished.

When Mitchel looks, it comes near

He sees the hills and trees

Which most conclusively doth prove

That 'tis not made of cheese.

--Cincinnati Enquirer, 18451

The Cincinnati Observatory, housing an

eleven-and-one-half-inch refractor

telescope, was opened for viewing in the

spring of 1845. The circumstances

by which the observatory came to be

built constitute an exemplary story

of science and democracy in the middle

decades of the nineteenth century,

as are also the efforts, and ultimate

failure, to make it become an important

research institution. Justification for

the observatory from its inception in

1842 was found in a curious blend of

localism, nationalism, and a belief

in democracy and the progress of man.

The monies for the telescope and

construction of the observatory were

raised by public subscription, making

this the

first astronomical institution of its size to

be built without either

royal or governmental patronage. As a

symbol of civic pride, the observatory

was viewed as an outstanding achievement

by a city freshly cut from the

wilderness. John P. Foote, who served

both as secretary and president of

the Cincinnati Astronomical Society,

expressed this sentiment later in 1855

when he wrote: "We [the citizens of

Cincinnati] gave an example to the

old and wealthy which they ought to have

given to us, who were young

and poor. . . . Cambridge and Washington

have now larger telescopes than

that of Cincinnati, which at the time it

was mounted, was the largest in

America. . . ."2

The observatory also was built as a

symbol of the intellectual ambition

of the young country. In 1842 when the

project was conceived, this nation-

NOTES ON PAGE 222

(614) 297-2300