Ohio History Journal

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

Rise and Decline of Private

Academies in Albany, Ohio

by Ivan M. Tribe

The nineteenth century witnessed the

establishment of numerous private

educational institutions, commonly known

as academies. These academies

were especially widespread in states

north of the Ohio River and could

be found both in the cities and in rural

villages.1 One Ohio town which

boasted a succession of these schools

was Albany, incorporated in 1842, a

small farm village in southwestern Athens

County.2 A study of the acade-

mies in Albany has a three-fold

significance. First, it illustrates the prob-

lems of operating and financing early

secondary educational institutions.

Second, it gives an idea of the role the

Albany schools played in the anti-

slavery movement of the 1850's as well

as in the education of Freedmen

and other Negroes during and immediately

following the Civil War years.

And third, it demonstrates the influence

that Oberlin College exerted on

educational reform efforts in the

mid-nineteenth century.

Since public supported secondary schools

in mid-nineteenth century Ohio

were not common, private academies

played an important role in the formal

education of the state's youth. Many of

these schools were operated by

individuals and stock companies or were

under the auspices of a church.

Receiving no state or local tax support,

the academies depended largely

upon student tuition for operating funds

and, because of limited enroll-

ment, were often in a precarious

financial condition. With some exceptions,

many had only a brief existence. Between

1840 and 1880, academies were

established in eight communities in

Athens County.3 In addition to these

private institutions, there was also

public supported Ohio University in

Athens which operated a preparatory

academy for students.4 Public high

schools were established in the county

under the provisions of the 1847

"Akron Law," but the first

class was not graduated in Athens until 1859.5

In 1847 the first of a succession of

private academies in Albany was

founded. It was opened shortly after the

arrival of the Ichabod Lewis family

in the village. This family, of

Connecticut origin, had moved to Albany

from Oberlin, Ohio, where they had lived

for several years. The elder

Lewis and two of his sons were furniture

makers, but William S., a third

son who had attended Oberlin College

intermittently between 1835 and

1843, and a spinster sister, Lamira,

were school teachers.6 The first classes

were started by Lamira, who taught some

of the local children in one

room of her father's house. Encouraged

by the success of his sister's attempt

to educate the young people of Albany,

William purchased a lot and

built a one-story frame building to

house the Lewis Academy. He and his

wife, Eliza, taught older students,

while Lamira continued to teach the

primary children. Students were admitted

without consideration of race

NOTES ON PAGE 225

ALBANY ACADEMIES

189

or sex, and it is probable these liberal

ideas resulted from the Oberlin

College influence on the Lewis family.7

The Academy prospered during the next

two years, and it became

necessary to add a second story to the

building. The growth and success

of this first academy caused other

members of the community to take

an interest in education. As a result,

in 1850 several persons in Albany

organized a joint stock company which

purchased a controlling interest

in the Lewis Academy. Shares in the

company were sold for twenty-five

dollars each. At the first meeting of

stockholders on September 25, 1850,

an executive board was chosen and John

T. Winn, a prominent local

farmer, was elected chairman. The Lewis

Academy then became the Albany

Manual Labor Academy, and the Lewis

building was selected to house

the reorganized school until additional

funds could be secured for a larger

structure.8

Among the first plans adopted by the new

executive board were proposals

to raise funds and to introduce a manual

labor program as a financial

aid to both the students and the school.

Also a traveling agent, Dr. Julius

A. Bingham, a well known resident of the

county and a veteran of the

War of 1812, was appointed to solicit

funds for the school. The use of

such agents by nineteenth century

educational institutions was common

practice, and, in most cases, the agent

was permitted to retain a percentage

of the funds collected as payment for

his services. Shortly afterward, Bing-

ham was joined by the Reverend Jonathan Cable, a

Presbyterian clergy-

man, who simultaneously served as

principal of the school.9 Cable was

an 1827 graduate of Ohio University and

had received his Master of Arts

degree in 1830.10 Both men were

successful in their solicitation of funds,

and as a result some three hundred acres

were purchased for use and

support of the school.11

The manual labor feature was designed to

permit students of modest

means to finance their own education.

Those pupils who needed assistance

could borrow money from the institution

and then repay the loan by

working two hours each day.12 The

manual labor concept, though not

common at the time, was not a new idea.

It had been developed during

the late 1820's in some eastern schools,

and such Ohio institutions as Ohio

University and Marietta College also had

similar departments. These

programs, however, nearly all failed to

achieve their purpose and were

abandoned after the Panic of 1837.13 The

attempt to revive the movement

by the Albany Manual Labor Academy in

the 1850's was only slightly

successful. The trustees had hoped to

build several workshops and other

facilities for skilled workers, but they

lacked the necessary funds, so farm-

ing became the chief activity of the

manual labor department. A few stu-

dents escaped the agricultural chores by

operating a sawmill and by making

brick. In spite of the difficulties, the

students were on one occasion able

to earn as much as $7000 in one year.

The department undoubtedly

enabled many students who could never

have otherwise received more

than the education provided by a

one-room school to finance their educa-

tion.14

|

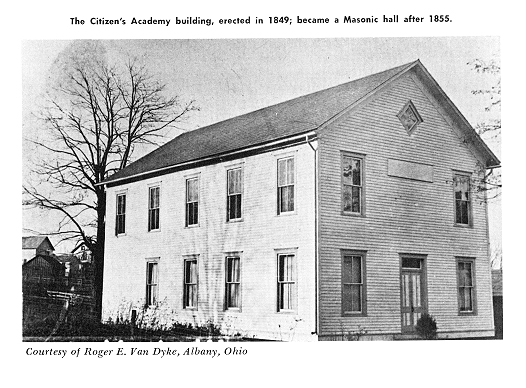

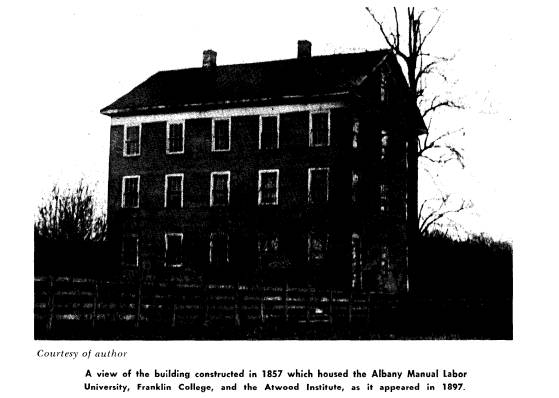

190 OHIO HISTORY Other persons besides the trustees of the Albany Manual Labor Academy developed interest in local education. In contrast to the integrated approach used by Lewis and his followers, some Albany townspeople felt segrega- tion was necessary.15 Sixteen persons formed a rival school, called the Citizens Academy, which was reserved for whites only. On March 17, 1849, this group purchased from Elizabeth Perkins16 a lot on Wilkes Street and subsequently erected a two-story frame building where classes were con- ducted for a time.17 Beginning in July 1853, most of the shares in this school were purchased by two local businessmen, Peter Morse and Augustus B. Dickey, who in turn sold the property on June 26, 1855, to the Heb- bardsville Masonic Lodge No. 156, then in the process of relocating in Albany.18 It is interesting to note that John Brown,19 a local merchant, who was a member of the board of trustees of the Albany Manual Labor Academy and a known sympathizer with the abolitionist movement and conductor on the "underground railroad," was also the major shareholder in the Citizens Academy, owning four of the twenty-eight shares.20 During the early 1850's the Albany Manual Labor Academy apparently increased its enrollment and also prospered, although very little informa- tion is available for this phase of the school's development. On April 9, 1852, the Ohio legislature passed a law which enabled educational institu- tions to receive from the state corporate charters whose purpose was to limit financial responsibility and help insure permanence.21 The Academy took advantage of the law and obtained a charter in 1853. It was then known as |

ALBANY ACADEMIES

191

the Albany Manual Labor University. In

March 1855, the personal and

real property of this corporation was

valued at $7850.22 Two years later a

new frame three-story building, 40 by

100 feet, replaced the old Lewis

Academy building.23 The new

site chosen was on Mill Street at the north-

western edge of the village.

The school apparently reached its peak

enrollment in the late 1850's.

By the fall of 1857, it was reported to

have had 284 students and seven fac-

ulty members. In the following school

year enrollment reached 302.24 As

far as is known this was the largest

number of students ever enrolled at the

school; no figures are available for

1859 and 1860.

There were three departments in the

university--primary, preparatory,

and collegiate. The primary department,

which functioned as an elementary

school had the fewest students,

twenty-eight in 1858-1859. Of these, twenty-

two had local addresses, while three

were from Cincinnati, two from Jack-

son, and one from Wilkesville, a small

community fourteen miles from Al-

bany.25 Several of the

elementary pupils were blacks, and their ages varied

considerably, while most of the white

children in attendance were of usual

elementary school age.26

The preparatory department was by far

the largest and numbered 194

students in 1859. About two-thirds of

these were males. Eleven students

came from outside the state; sixty-seven

came from the Albany area, forty

from more distant parts of Athens

County, fifty-seven from adjacent coun-

ties, and fifteen from more remote parts

of Ohio. As in the primary depart-

ment, several of the students were

Negroes, but the proportion of black

to white was much smaller. Subjects

taught in this division included orthog-

raphy, grammar, geography, history,

bookkeeping, Latin and Greek, as

well as the "3-R's."27

The collegiate department contained

eighty students in 1859, and the sex

ratio and geographic distribution was

quite similar to that of the prepara-

tory department, though the number of

students from adjacent southeastern

counties was somewhat higher. This

department offered two four-year ma-

jors of collegiate study in classics and

science. The courses in both fields,

however, were strikingly similar varying

only slightly in the junior and

senior years.28 It is

probable that most of the students were freshmen and

sophomores, for apparently no one ever

obtained a degree from Albany

Manual Labor University.

Many former students of the university

became teachers in public schools.

Two students listed in the collegiate

department, Lyman C. Chase and

Thomas J. Ferguson, became principals of

other academies in Albany. Other

students pursued courses in business and

law.29 Probably the best known

student was James Monroe Trotter, a

Mississippi Negro, who had attended

Gilmore High School in Cincinnati. He

was one of the few blacks to become

a commissioned officer in the Union Army

during the Civil War.30 Trotter,

later appointed assistant superintendent

of the registered letter department

in Boston, was one of the Republican

Mugwumps in 1884 and subsequently

held the Federal office of Recorder of

Deeds during President Grover Cleve-

192 OHIO HISTORY

land's first administration. Afterwards,

he wrote a history of Negro music

and musicians and practiced law until

his death in 1912.31

The school year was divided into four

terms of ten weeks each. The cost

to students in the primary department

was $2.50 per term, the preparatory

department charge was $3.00, and that of

the collegiate department, $4.00.

In addition, there was a "contingent

expenses" fee of twenty-five cents.

Room and board could be obtained either

at the school dormitory or in

private homes for $1.90 per week.

Separately, board cost $1.40, while a room

would cost fifty cents.32

Only five faculty members were listed in

the catalog for 1858-1859, al-

though it seems probable that there were

two or three others. The Reverend

Cable held the office of principal, and

his wife Sarah was a teacher. Other

faculty members included Nathan

McLaughlin, Daniel B. Cable, possibly

a brother of the principal, and S. E.

Root. New faculty members for the

fall of 1859 were to include the

Reverend M. M. Travis in languages and

W. S. Travis in natural science.33 The

former was a native Ohioan who

held the master's degree and like Cable

was a Presbyterian clergyman. In

1860 he was twenty-nine years old; his

wife, Mattie, was evidently a part-

time teacher.34

The university was governed by a

constitution of thirteen articles which

outlined the objectives, principles, and

form of organization of the school.

According to article one, the primary

objective of the institution was:

To furnish the advantage of a thorough

education at the least pos-

sible expense; to break down, so far as

our influence shall extend, the

oppressive distinctions on account of

caste and color, and counteract

both by example and precept, a spirit of

aristocracy, that is spreading

itself throughout the land, and which it

is feared, the influence of many

of our institutions of learning has a

great tendency to encourage.35

This section illustrates the liberal

views held by the framers of the consti-

tution, who also stated that a

"pure morality and evangelical religion shall

be taught, guarding against . . .

sectarian influence." In regard to the man-

ual labor phase of the school, the

constitution stated:

Labor shall be combined with study

invariably, in such manner as

the Trustees may direct, so that no less

than two hours of manual labor,

each day, shall be required of every

teacher and student, unless pre-

vented by sickness or other bodily

infirmity.36

Ownership of the chartered institution

was, as before, vested in sharehold-

ers. Shares, at a price of twenty-five

dollars each, were to be the primary

source of operating capital.

Slaveholders were denied the right of purchasing

stock. The shareholders were to hold

annual meetings on the last Thursday

in September for election of trustees

and other officers.37

In 1859, the school was controlled by a

board of trustees composed of

twenty persons, six of whom made up the

executive committee.38 Many of

the trustees included local residents,

such as John Brown, John T. Winn,

and John Q. Mitchell, all of whom were

prominent in community affairs.

The board of trustees also included at

least one Negro, Philip Clay, a local

ALBANY ACADEMIES

193

shoemaker who was born a slave in

Virginia. Lamira Hudson, the former

Lamira Lewis, was probably the lone

woman on the board.39 Others who

served were local farmers and skilled

workers who could not have had more

than a common school education. The

membership reflected the liberal

views contained in article one of the

school's constitution and presented a

democratic example both in substance and

in spirit.

Governor Salmon P. Chase was also a

member of the board of trustees

and served as one of its four vice

presidents.40 How much actual interest

Chase took in the school and to what

extent he participated in its activities

cannot be determined; however, he did

lend the prestige of his name and

gave some financial support to the

institution.41 It is interesting to see how

Jonathan Cable, the school's

superintendent, attempted to tie his school to

the antislavery movement and to the

newly formed Republican party in

order to obtain support from Chase.

Cable, who journeyed East in 1858 to

raise funds for the institution, wrote

to Chase for aid, explaining that the

hopes of the Republican party in southeastern

Ohio rested with the success

of the Albany Manual University:

You are aware of the importance of this

University in propagating

the right principles on the subject of

human rights as well as literature

generally. The friends of humanity

cannot well afford to have this Inst.

[sic] go down or have it crippled in its energies.

The institution is about $6,000 in debt

which must be paid soon or

our land will be sold which will be a

great calamity. I have started out

to collect the funds to clear the Inst.

of debt and raise $50,000 to endow

it.

The favor that I ask of you is to give

me an introduction to some of

the members of Congress setting forth

the importance of this Inst. in

reference to the Anti-Slavery Movement

and the Republican Party.

When this school was established there

were but three anti-slavery

men in town. Buchanan got but three

votes in town--and we have from

800 to 1200 majority in the county--and

the influence of this school is

felt through the adjoining counties. We

sent out from 40 to 50 teachers

imbued with the Anti-Slavery sentiment.

The Republican Party could not suffer a

greater calamity in South-

ern Ohio than to have this school go

down. It can and must be sus-

tained, and its influence extended.

Please to address me at Washington City

care of Mr. Horton, our

member of Congress, and recommend me to

such members as you see

profitable and you will very much oblige

your old friends and aid in

this noble cause . . . .42

Evidently, Cable's efforts to raise

funds to pay the school's debts were in-

adequate for he stated in a later letter

to Chase that "[the] mortgage ran

out about the commencement of the

war--the Board was unable to meet the

demand and the land and buildings were

sold."43 Cable's story is collab-

orated by records in the Athens County

courthouse. Between April 5, 1861,

and November 11, 1862, the real property

of the Albany Manual Labor

University was sold at four sheriff's

sales.44 With the close of the 1861-62

school year the university passed into

history.

|

194 OHIO HISTORY Private education in Albany, however, did not end at this time although its course was altered when two new schools were established to replace the university. The first was located in the same building which had housed the parent institution. Under the control of two church denominations this structure housed an educational institution for another thirty-six years and was first known as Franklin College, and, after 1866, as Atwood Institute. The second, housed in a different location, continued some of the prin- ciples of its predecessor in regard to Negro education and became the best known of Albany's private schools, the Enterprise Academy. |

|

In the fall of 1862, the building which had housed the Manual Labor University became the property of the Christian Church-then commonly known as Campbellites, after their founder, Alexander Campbell. The school was renamed Franklin College, and the Reverend Thomas D. Garvin was appointed principal. The other members of the faculty were James and Hugh Garvin, brothers of the principal, James Dodd, and two women whose names are unknown.45 During the brief period in which Franklin College operated, it appears to have been a fairly successful venture, especially considering that most schools had financial and staffing difficulties during the Civil War period. Enrollment is said to have approached two hundred, and a number of |

ALBANY ACADEMIES

195

changes were introduced. The manual

labor department was discontinued,

and Negroes were denied admission.46

The practice of coeducation, how-

ever, was continued. Since it was war

time, the number of girls attending

the school was probably greater in

proportion to those who had attended

the manual labor school.47

At Franklin College (referred to as

Albany Institute in the Athens Mes-

senger) the school year was divided into two sessions of twenty

weeks each.

Like the manual labor school, it had

three departments, primary, prepara-

tory and collegiate. Tuition was to be

paid in advance and was slightly

higher than at Albany Manual Labor

University. The fees in the various

departments were five, eight, and ten

dollars respectively. Extra fees were

charged for music and art. Those who

wished to take music had a choice of

piano, melodeon, or guitar for sixteen

dollars. Instruments could be rented

from the institution for four dollars.

Lessons in pencil drawing were avail-

able for four dollars and in oil

painting for sixteen. Room and board in

private homes cost two dollars per week.

Those who lived in the school

dormitory could board themselves for

seventy-five cents to one dollar per

week. Room rent in the dormitory, which

was situated on the upper floors

of the school building, was on

"moderate terms."48

Although Franklin College seems to have

been a fairly successful venture

during its years in Albany, the

Christian Church decided to transfer it to

Wilmington, Ohio, in the summer of 1865.

This was done, but after a few

years the school's facilities were sold

to the Quakers, and the institution

has since become Wilmington College. The

school building at Albany was

sold in 1866 to the Free Will Baptist

Church.49

When the Baptist Quarterly Meeting

assumed control of the school,

additional changes were made. Both the

primary and collegiate depart-

ments were discontinued; only the

preparatory department remained. Stu-

dents could prepare themselves for

college or for teaching in the public

schools.50 The school's

financial security was based in large part upon the

philanthropy of local patrons and Nehemiah

Atwood, a wealthy Baptist

layman of Gallia County. The trustees

later renamed the school Atwood

Institute.51

The first principal of the Atwood

Institute was Lyman C. Chase, a

graduate of Hillsdale College in

Michigan and a one time student at the

Albany Manual Labor University. He

remained for three years.52 In 1867,

his second year as principal, enrollment

reached 275. Beginning in 1869

Morton W. Spencer, teacher at the school

and minister of the Albany

Baptist Church, became principal.53

Enrollments declined under Spencer

and his successors from 147 to a low of

125 in 1872. The next year the

school enjoyed a brief revival when the

enrollment climbed to 235. Between

late 1871 and 1875, Joseph M. Wood,

later a noted attorney and Athens

County Common Pleas Judge, served as

principal. After he resigned, his

younger brother James Perry Wood, a

teacher at the school, served for two

years as principal. There are no

enrollment figures for 1876 and 1877, but

enrollments were presumably declining.

In 1880 Lyman Chase returned

196 OHIO HISTORY

for another two years as principal

during which time the enrollment fell

to fifty-three.54 Clarence O.

Clark of Rio Grande was the last principal,

and during his five year tenure

enrollments varied from ten to eighty.55

Finally, in 1888 when the enrollment

declined to twelve, the Atwood

Institute closed its doors for the last

time, ending a twenty-two year

existence.56

A description of the school during one

of the middle years of its

existence shows that it was divided into

two divisions: common, for teach-

er preparation; and higher, for college

preparation. Tuition for an eleven

week term was five dollars in the common

branch and six dollars in the

higher branch. The upper two floors of

the academy building served as

a dormitory and had facilities for

seventy students. Students were charged

rent of one dollar per week to stay in

rooms furnished with beds, tables,

chairs, and stoves. This arrangement

permitted those who wished to prepare

their own food. Those who could afford

the luxury of room and board

in private homes paid three dollars per

week.57 During at least one summer,

1878, a six-week "Normal

Institute" was held for vacationing teachers under

the direction of M. F. Parrish and T. G.

Lewis. "Careful instruction will

be given in the best methods of

teaching," said the advertisement in the

Albany Echo. A special summer

course in penmanship was also available

for six dollars.58

By 1888, when the Atwood Institute

closed its doors, the public high

school was becoming more common. Only

one private academy in Athens

County, the Amesville Academy, outlived

Atwood. Possibly, the Baptist

Church also lost interest in maintaining

the school, for certainly Rio Grande

College, which had been founded through

money from the Atwood estate,

offered better opportunities for a

school located where there would be less

competition from Ohio University.

It will be remembered that both the

Lewis Academy and the Albany

Manual Labor University permitted

Negroes to enroll, and by the late

1850's several Negroes were in

attendance. Census records show that the

Negro population of Lee Township (where

Albany is located) increased

from four in 1850, to 174 in 1860.59 But

when the Albany Manual Labor

University came under the control of the

denominational churches in

1862, first the Christian and then the

Free Will Baptist, Negroes were

no longer admitted.

Shortly afterward, in 1863, several of

the colored citizens of the Albany

area conceived the idea of starting

their own school to educate members

of their race exclusively.60 The

first trustees of the school, known as the

Albany Enterprise Academy, were Thomas

J. Ferguson, Cornelius Berry,

Philip Clay, David Norman, Woodrow

Wiley, and Jackson Wiley, all local

Negroes.61 Money was obtained

in a manner similar to that of the Albany

Manual Labor University a decade

earlier. Shares of stock in the school

were sold at twenty-five dollars each,

and many persons donated one

hundred dollars and more. Thomas and

Isaac Carleton of Syracuse, Meigs

County, were the largest donors, giving

three thousand dollars.62 Other

|

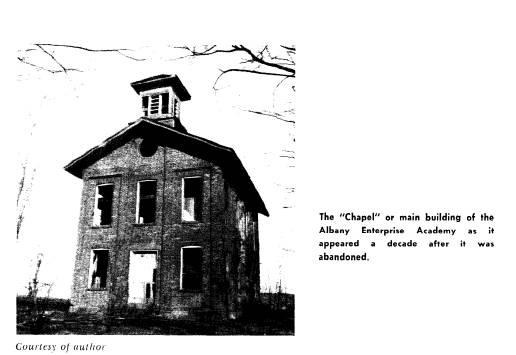

persons of note who made contributions were General Oliver O. Howard of the Freedmen's Bureau, Morrison R. Waite who later became Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court, and two area members of Congress, Rufus Dawes of Marietta and Eliakim H. Moore of Athens.63 Another source of funds was the Freedmen's Bureau, which loaned the trustees $2000.64 What remained of the endowment fund of the Albany Manual Labor University was turned over to the new school by Jonathan Cable after permission of the remaining shareholders was secured. Cable also made at least one trip East to solicit funds from philanthropists there, and Jackson Wiley, a local black, served as field agent for several years gathering additional funds.65 On November 20, 1863, a site of about twenty acres was purchased on the north edge of town.66 By the following June, a two-story brick build- ing, thirty by forty-eight feet, was nearing completion. Classes were already being conducted and forty-nine students were enrolled. Two ministers from Amesville and Marietta who visited the school at this time were quite pleased with the progress that had been made by the colored people, as was the president of Marietta College. All three of these gentlemen felt the school project should be encouraged and supported.67 By the fall of 1864, the academy building or "Chapel," as it came to be |

|

called, was completed. Classes were held on the first floor, and the upper story was used as an assembly hall for religious services and other meetings. In 1870, a second building was erected for use as a girls dormitory. This frame building, sixty by thirty-two feet, was built at a cost of $5000 and contained two stories above ground which housed the girls, and a semi- basement which contained a kitchen, dining room, wash room, and storage space.68 The Enterprise Academy was governed by a board of trustees selected by the stockholders at the annual August meeting. These stockholders came from Gallipolis, Cincinnati, and Pittsburgh, as well as the Albany area. Selection of the trustees and other officers, all of whom were evidently required to be Negroes, and transaction of other business preceded a big picnic dinner held on the grounds to promote "fellowship."69 Many persons served on the faculty of the Enterprise Academy during the period of more than twenty years it was in operation. In most instances, however, little is known except the last names of these individuals. The first known teacher was Miss Gee, and the first principal was the Reverend Bingby. The Reverend Brooks was another early teacher. Two professors from Oberlin who taught music and voice, the most popular subjects at the institution, were Mr. Imes and Mr. Waring. Another who served was Mr. Jones. During the early 1870's, the Reverend J. R. Bowles served as principal and his son was a teacher. The best known members of the faculty were William Sanders Scarborough and Thomas Jefferson Fergu- son.70 Scarborough was a native of Georgia, and his parents had been freed before his birth. After the close of the Civil War, he attended a school for Negroes in Atlanta before enrolling in Oberlin College in 1871. During his years as a student at Oberlin, he sometimes taught school in various |

ALBANY ACADEMIES

199

places around the state, and one winter

was spent teaching at Enterprise

Academy (probably 1872-1873). In later

years he became one of America's

most noted educators and served as

president of Wilberforce University.71

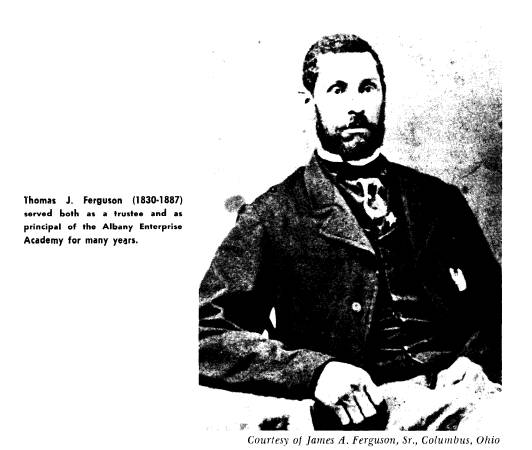

Unlike Scarborough whose period of

association with the Enterprise

Academy was brief, Thomas J. Ferguson

was a resident of Albany for many

years and was more closely connected

with the Negro school than any

other person. He, too, was of mixed

blood and free born.72 Ferguson was

born September 15, 1830, in Essex

County, Virginia,73 but nothing more

is known of his life until the late

1850's when he was a student in the

collegiate department at the Albany

Manual Labor University, giving Cin-

cinnati as his home address.74 He

became a land owner in the village

of Albany on March 10, 1859.75

One of the original members of the

board of trustees at the academy,

Ferguson taught there intermittently

for several years, particularly during

the latter years. At various times, he

also taught in the colored public

schools in Albany and Middleport, Ohio,

and in Parkersburg, West Virginia.76

During his teaching career in the

latter city in 1866, he was described by

the eminent Negro historian,

Carter G. Woodson, as being

A versatile character among the Negroes

at that time, participating

extensively in politics during the

reconstruction period, and contending

for the enlargement of freedom and

opportunity for their race.77

Well known as a public speaker, he also

authored a pamphlet which

encouraged Negro education.78 On

April 1, 1872, Ferguson was elected

to a two year term as councilman, and

thus became the only Negro ever

to hold public office in Albany.79 Although

there were many colored

residents in the village during the

latter half of the nineteenth century,

none was held in higher esteem than

Thomas J. Ferguson by either Negroes

or whites. He died March 30, 1887.80

During the early years of its existence,

the Albany Enterprise Academy

sometimes had over one hundred students.

Enrollment, however, seems to

have declined in the late 1870's and

continued to be low for the remainder

of the time the school was in operation.

After 1870, the dormitory provided

housing for girls, and boys lived with

private families. Although many

of the students came from the Albany

area, some came from more distant

parts of the state and even from other

states, particularly West Virginia.81

Several students of the Enterprise

Academy gained some degree of

fame. Olivia Davidson became the second

wife of Booker T. Washington

and was associated with her husband in

his work at Tuskegee Institute

until her death in 1889; her brother,

Andrew Jackson Davidson, practiced

law in Athens for many years. Edwin C.

Berry later owned and operated

the Berry Hotel in Athens, which was

then known as one of the best

small town hotels in the nation.82 Milton

M. Holland was a Texas-born

shoemaker's apprentice in 1860,83 but

after the Civil War broke out, he

gained recognition as an able recruiter

of Negro troops in southeastern

Ohio.84 Holland culminated

his war career as one of the first group of

twelve Negroes in the Union Army to be

awarded the Medal of Honor.85

200 OHIO HISTORY

Years later, as a resident of

Washington, D. C., he became a "black-capital-

ist," founding the Alpha Insurance

Company.86 An older brother, William

H. Holland, also served in the Union

Army and later served in the Texas

state senate during the reconstruction

period.87 Other students of the Enter-

prise Academy also gained moderate

degrees of fame and success, primarily

as ministers and teachers, in colored

communities in Ohio and elsewhere.88

Although the Albany Enterprise Academy

advertised: "A complete

ACADEMIC COURSE of study is

taught,"89 there is evidence that academic

standards at the school were not

especially high. Certainly most of the

student body consisted of elementary

students.90 The daughter of Thomas

J. Ferguson records that great emphasis

was placed on the teaching of

"voice culture and music."91

Since many of the students, especially those

from the South, lacked previous

educational experience, it would seem

logical that much of the material taught

was on a primary level.

Tuition costs at the Enterprise Academy

in 1885 were three dollars for

a twelve week term. Furnished rooms were

available for one dollar per

month, but semi-furnished rooms were

free to those who had paid their

full tuition.92 A sizable number of the

students probably did not pay in

full for it was stated that

Many of our people are poor, and nothing

can be collected from

them in the form of tuition; yet not one

has ever been denied admission

or instruction.93

Student fees in the 1880's were

supplemented by the proceeds from a

small fruit farm on the school property,

which in the fall of 1885 was "doing

well and paying something to the

Institution."94 The trustees hoped to

enlarge the orchard and, as the trustees

at the Albany Manual Labor Uni-

versity had previously planned, to set

up a brickyard and cooper shop.95

These hopes were apparently growing

weak, however, for that same

fall it was also reported that "Our

buildings are much in need of repair,"96

and on September 24, the "Ladies

Dormitory" and its furnishings were

completely destroyed by fire. The

insurance on the building had lapsed

and money could not be raised to replace

it.97 Thereafter conditions

declined rapidly, and with the

resignation in 1886 of the ailing principal

Thomas J. Ferguson the school was forced

to close.98

With the passing of the Enterprise

Academy in 1886, followed by the

closing of the Atwood Institute two

years later, residents of the Albany

community found themselves, for the

first time in forty years, with no

private academies. The schools had

experienced alternating periods of

prosperity and financial crisis during

these four decades. The periods of

prosperity were all too brief, and there

were never enough reserve funds

to sustain the schools through periods

of hardship. Franklin College and

Atwood Institute seem to have enjoyed

the greatest prosperity, and even

that was barely enough to keep them

above the subsistence level. This

greater amount of financial security

seems to have been in part due to

their affiliation with denominational

churches, which not only provided

some financial aid to the schools but

also encouraged additional private

ALBANY ACADEMIES

201

donations by members. The Albany Manual

Labor University and the

Albany Enterprise Academy by the very

nature of their purpose were

destined to financial hardship. Although

only a few public high schools

could be found in southeastern Ohio

before the late 1890's, by the late

1880's the days of the private academy

were about over in most areas.99

From the time that William Lewis and his

sister opened the first private

school in Albany, the influence of

Oberlin College had been quite evident.

The college, a pioneer institution in

both the state and nation, spread the

idea that women and Negroes should have

equal opportunities for educa-

tion. This belief was carried on by the

Lewis Academy and its successor

school, the Albany Manual Labor

University, and became widely accepted

by much of the local citizenry. Even in

the church-related schools, women

and men continued to attend the same

classes although Negroes were barred.

In addition to the Lewises, at least

three faculty members of Albany's

academies were former Oberlin students.

To be sure, Albany was but one

of many communities in the Midwest that

was influenced by the beliefs

practiced and spread by Oberlin College,

for it has been said that the

"trail of many a reformer led

straight back to Oberlin."100

When the Lewis Academy opened, there

seemed to have been little

or no pronounced interest in either

abolition or Negro education in the

Albany community, and although Negroes

were permitted to enter the

school from the very first, there were

but few Negroes in the community.

However, by 1853, abolition sentiment in

Albany was strong enough that

an abolitionist newspaper, The Free

Presbyterian, located there, and by

1856 it was claimed that antislavery

sentiment was so strong that all but

three votes went to the antislavery

candidate in the presidential election.101

As abolition sentiment grew in Albany,

so too did the influx of Negroes,

who by 1860 totaled nearly a third of

the population of the village.102

Many students who had attended the

Albany Manual Labor University

before beginning their teaching careers

in the public schools were, as

Jonathan Cable claimed, antislavery in

sentiment and influenced others

in surrounding communities.

In addition to influencing whites to

favor antislavery, the school also

gave many Negroes needed opportunities

to receive an education. Dur-

ing and after the Civil War the Albany

Enterprise Academy carried on

this work, teaching a greatly increased

number of Freedmen. Although

the schools closed because of financial

failure, they were able to make their

presence felt. During their brief

existence they managed to attract the

attention and sympathy of such state and

national figures as Salmon P.

Chase, Joshua Giddings, John McLean,

Morrison R. Waite and Oliver

Otis Howard. They also, especially

Enterprise Academy, produced a list

of secondary Negro notables in the

decades following emancipation. In all

probability, there were but few

struggling small town academies in Ohio

that could make all of these claims.

THE AUTHOR: Ivan M. Tribe is a

public school teacher living in

Albany.

Rise and Decline of Private

Academies in Albany, Ohio

by Ivan M. Tribe

The nineteenth century witnessed the

establishment of numerous private

educational institutions, commonly known

as academies. These academies

were especially widespread in states

north of the Ohio River and could

be found both in the cities and in rural

villages.1 One Ohio town which

boasted a succession of these schools

was Albany, incorporated in 1842, a

small farm village in southwestern Athens

County.2 A study of the acade-

mies in Albany has a three-fold

significance. First, it illustrates the prob-

lems of operating and financing early

secondary educational institutions.

Second, it gives an idea of the role the

Albany schools played in the anti-

slavery movement of the 1850's as well

as in the education of Freedmen

and other Negroes during and immediately

following the Civil War years.

And third, it demonstrates the influence

that Oberlin College exerted on

educational reform efforts in the

mid-nineteenth century.

Since public supported secondary schools

in mid-nineteenth century Ohio

were not common, private academies

played an important role in the formal

education of the state's youth. Many of

these schools were operated by

individuals and stock companies or were

under the auspices of a church.

Receiving no state or local tax support,

the academies depended largely

upon student tuition for operating funds

and, because of limited enroll-

ment, were often in a precarious

financial condition. With some exceptions,

many had only a brief existence. Between

1840 and 1880, academies were

established in eight communities in

Athens County.3 In addition to these

private institutions, there was also

public supported Ohio University in

Athens which operated a preparatory

academy for students.4 Public high

schools were established in the county

under the provisions of the 1847

"Akron Law," but the first

class was not graduated in Athens until 1859.5

In 1847 the first of a succession of

private academies in Albany was

founded. It was opened shortly after the

arrival of the Ichabod Lewis family

in the village. This family, of

Connecticut origin, had moved to Albany

from Oberlin, Ohio, where they had lived

for several years. The elder

Lewis and two of his sons were furniture

makers, but William S., a third

son who had attended Oberlin College

intermittently between 1835 and

1843, and a spinster sister, Lamira,

were school teachers.6 The first classes

were started by Lamira, who taught some

of the local children in one

room of her father's house. Encouraged

by the success of his sister's attempt

to educate the young people of Albany,

William purchased a lot and

built a one-story frame building to

house the Lewis Academy. He and his

wife, Eliza, taught older students,

while Lamira continued to teach the

primary children. Students were admitted

without consideration of race

NOTES ON PAGE 225

(614) 297-2300